Russell, Bertrand - A.Free.Man's.Worship

A Freeman’s Worship

Blind

to good and evil, reckless of destruction, omnipotent matter rolls on its relentless way; 这个全能的物质世界毫不容情地滚滚前行,

无视善恶,任意摧毁

for

到,当他们的心中闪烁着圣火时,我们曾同情他们,安慰他们,并曾用豪言 壮语鼓舞他们。

Brief

and powerless is Man‘s life; on him and all his race the slow, sure doom falls pitiless and dark.人的生命是短暂而脆弱的,不可避免的死亡虽

A Freeman’s Worship

一个自由人的信仰

By Bertrand Russell

伯特兰· 罗素

The

life of Man, viewed outwardly, is but a small thing in comparison with the forces of Nature. 从外表看来,人的生命与自然的力量相比是微不足道的。 The slave is doomed to worship Time and Fate and Death, because they are greater than anything he finds in himself, and because all his thoughts are of things which they devour. 奴隶注定要崇拜时间、命运和死亡。因为他内心没有

的壮丽,就比它们更伟大。

And

such thought makes us free men; 这些思想

伯特兰罗素名人名言

伯特兰罗素名人名言1.在美国,所有人都认为没有什么人比他的社会地位高,因为人人生而平等。

但是,他可不承认没有人比他社会地位低。

2.不要害怕怀有怪念头,因为现在人们接受的所有的观念都曾经是怪念头。

3.民主,就是挑选那个受批评的人的过程。

4.喝醉是暂时性的自杀。

5.我明确的说,由教会所组织的基督教是道德进步的最大敌人,过去如此,现在依然如此。

6.从阿米巴变形虫到人类的这一过程对哲学家来说,很明显是个进步。

但是变形虫怎么想我们就不知道了。

7.我永远不会为信仰而死,因为我的信仰可能是错的。

8.据说人是一种理性动物。

穷我自己一生,我都在寻找这观点的证据。

9.人是轻信的动物,必须得相信点什么。

如果这种信仰没有什么好的依据,糟糕的依据也能对付。

10.很多人可以勇敢的死去,但是却没有勇气说他为之而死的原因没有意义,甚至连这样想一想的勇气也没有。

11.很多人陷入爱情是为了寻找一个遁世的避难所。

在这个避难所里,当他们不值得爱慕的时候,依然有人爱慕他们,当他们不值得赞扬的时候,依然有人赞扬他们。

12.有很多人,让他们思考一下还不如让他们去死。

事实上,很多人还没思考过就已经死了。

13.人生而无知,但还不愚蠢。

教育才把他们变蠢。

14.传统的人看到背离传统的行为就大发雷霆,主要是因为他们把这种背离当作对他们的批评。

15.幻觉不是你的错,在幻觉中做决定,这就是你的不对了。

16.生活中完全没有冒险,这可能是没什么意思的。

但是生活中如果不管什么种类的探险都有,那肯定是短暂的。

17.我曾相信,所有值得知道之事,我在剑桥都知道了。

在我旅行的过程之中,这一想法逐渐消失了。

这与我本意相反,但是却对我非常有益。

18.亚里士多德说女人比男人的牙齿要少。

尽管他结了两次婚,但是他都没想过要检查一下他老婆的牙。

19.对幸福的轻蔑通常是对其他人幸福的轻蔑,在精巧的伪装之下是对人类的仇恨。

伯特兰·罗素简介:伯特兰·罗素(bertrand russell,1872-1970)是二十世纪英国哲学家、数学家、逻辑学家、历史学家,无神论或者不可知论者,也是上世纪西方最著名、影响最大的学者和和平主义社会活动家之一,罗素也被认为是与弗雷格、维特根斯坦和怀特海一同创建了分析哲学。

伯特兰罗素的名言

伯特兰罗素的名言伯特兰·罗素(Bertrand Russell)是20世纪最有影响力的哲学家、数学家、逻辑学家和社会评论家之一。

他的名言涵盖了多个领域,包括哲学、政治、道德和个人生活。

以下是一些伯特兰·罗素的名言:1. "The good life is a process, not a state of being. It is a direction, not a destination."(美好的生活是一个过程,而不是一种存在状态。

它是一个方向,而不是一个目的地。

)2. "The trouble with the world is that the stupid are cocksure and the intelligent are full of doubt."(世界的问题在于愚蠢的人自信满满,而聪明的人充满怀疑。

)3. "The whole problem with the world is that we don't know what we want, and we are living in a dream."(整个世界的问题在于我们不知道自己想要什么,我们生活在一个梦想中。

)4. "The only thing that will make a man happy is to do what he adores doing, and be paid for it."(唯一能让一个人快乐的事情就是做他热爱的事情,并因此得到报酬。

)5. "The best way to overcome a wrong is with the right, not with a wrong."(克服错误的最好方法是用正确的方法,而不是用错误的方法。

)6. "The happiness that is genuinely satisfying is accompanied by the fullest exercise of our faculties in the service of some end outside the self."(真正令人满意的幸福伴随着我们能力的最大发挥,服务于自我之外的某个目标。

罗素《我为什么而活着》教案

我为什么而活着?[英]伯特仑·罗素三种单纯然而极其强烈的激情支配着我的一生。

那就是对于爱情的渴望,对于知识的追求,以及对于人类苦难痛彻肺腑的怜悯。

这些激情犹如狂风,把我伸展到绝望边缘的深深的苦海上东抛西掷,使我的生活没有定向。

我追求爱情,首先因为它叫我消魂。

爱情使人消魂的魅力使我常常乐意为了几小时这样的快乐而牺牲生活中的其他一切。

我追求爱情,又因为它减轻孤独感--那种一个颤抖的灵魂望着世界边缘之外冰冷而无生命的无底深渊时所感到的可怕的孤独。

我追求爱情,还因为爱的结合使我在一种神秘的缩影中提前看到了圣者和诗人曾经想像过的天堂。

这就是我所追求的,尽管人的生活似乎还不配享有它,但它毕竟是我终于找到的东西。

我以同样的热情追求知识,我想理解人类的心灵,我想了解星辰为何灿烂,我还试图弄懂毕达哥拉斯学说的力量,是这种力量使我在无常之上高踞主宰地位。

我在这方面略有成就,但不多。

爱情和知识只要存在,总是向上导往天堂。

但是,怜悯又总是把我带回人间。

痛苦的呼喊在我心中反响回荡,孩子们受饥荒煎熬,无辜者被压迫者折磨,孤弱无助的老人在自己的儿子眼中变成可恶的累赘,以及世上触目皆是的孤独、贫困和痈苦--这些都是对人类应该过的生活的嘲弄。

我渴望能减少罪恶,可我做不到,于是我感到痛苦。

这就是我的一生。

我觉得这一生是值得活的,如果真有可能再给我一次机会,我将欣然再重活—次。

What I have lived for?Bertrand RussellThree passions, simple but overwhelmingly strong, have governed my life: the longing for love, the search for knowledge, and unbearable pit y for the suffering of mankind. These passions, like great winds, have blown me hither and thither, in a wayward course, over a great ocean o f anguish, reaching to the very verge of despair.I have sought love, first, because it brings ecstasy - ecstasy so great that I would often have sacrificed all the rest of life for a few hours of thi s joy. I have sought it, next, because it relieves loneliness--that terrible loneliness in which one shivering consciousness looks over the rim of the world into the cold unfathomable lifeless abyss. I have sought it finally, because in the union of love I have seen, in a mystic miniature, th e prefiguring vision of the heaven that saints and poets have imagined. This is what I sought, and though it might seem too good for human li fe, this is what--at last--I have found.With equal passion I have sought knowledge. I have wished to understand the hearts of men. I have wished to know why the stars shine. And I have tried to apprehend the Pythagorean power by which number holds sway above the flux. A little of this, but not much, I have achieved. Love and knowledge, so far as they were possible, led upward toward the heavens. But always pity brought me back to earth. Echoes of cries of pain reverberate in my heart. Children in famine, victims tortured by oppressors, helpless old people a burden to their sons, and the whole world of loneliness, poverty, and pain make a mockery of what human life should be. I long to alleviate this evil, but I cannot, and I too suffer. This has been my life. I have found it worth living, and would gladly live it again if the chance were offered me.教学目标:1、知识与能力理解文章的主旨以及作者的感情。

Bertrand Russell波特兰.罗素英文简介

Bertrand RussellBertrand Arthur William Russell (born in.1872 and died in.1970) was a British philosopher, logician, essayist and social critic best known for his work in mathematical logic and analytic philosophy. His most influential contributions include his defense of logicism (the view that mathematics is in some important sense reducible to logic), his refining of the predicate calculus introduced by Frege (which still forms the basis of most contemporary logic), his defense of neutral monisme (the view that the world consists of just one type of substance that is neither exclusively mental nor exclusively physical), and his theories of definite descriptions and logical automisme Along with GE moore, Russell is generally recognized as one of the founders of modern analytic philosophy. Along with Kurt Godel, he is regularly credited with being one of the most important logicians of the twentieth century.Over the course of his long career, Russell made significant contributions, not just to logic and philosophy, but to a broad range of subjects including education, history, political theory and religious studies. In addition, many of his writings on a variety of topics in both the sciences and the humanities have influenced generations of general readers.After a life marked by controversy—including dismissals from both Trinity College, Cambridge, and City College, New York—Russell was awarded the Order of Merit in 1949 and the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1950. Noted for his many spirited anti-war and anti-nuclear protests, Russell remained a prominent public figure until his death at the age of 97.。

罗素(Bertrand Russell)- 我为什么不是基督教徒 英文原版

Why I Am Not A Christianby Bertrand RussellIntroductory note: Russell delivered this lecture on March 6, 1927 to the National Secular Society, South London Branch, at Battersea Town Hall. Published in pamphlet form in that same year, the essay subsequently achieved new fame with Paul Edwards' edition of Russell's book, Why I Am Not a Christian and Other Essays ... (1957).As your Chairman has told you, the subject about which I am going to speak to you tonight is "Why I Am Not a Christian." Perhaps it would be as well, first of all, to try to make out what one means by the word Christian. It is used these days in a very loose sense by a great many people. Some people mean no more by it than a person who attempts to live a good life. In that sense I suppose there would be Christians in all sects and creeds; but I do not think that that is the proper sense of the word, if only because it would imply that all the people who are not Christians -- all the Buddhists, Confucians, Mohammedans, and so on -- are not trying to live a good life. I do not mean by a Christian any person who tries to live decently according to his lights. I think that you must have a certain amount of definite belief before you have a right to call yourself a Christian. The word does not have quite such a full-blooded meaning now as it had in the times of St. Augustine and St. Thomas Aquinas. In those days, if a man said that he was a Christian it was known what he meant. You accepted a whole collection of creeds which were set out with great precision, and every single syllable of those creeds you believed with the whole strength of your convictions.What Is a Christian?Nowadays it is not quite that. We have to be a little more vague in our meaning of Christianity. I think, however, that there are two different items which are quite essential to anybody calling himself a Christian. The first is one of a dogmatic nature -- namely, that you must believe in God and immortality. If you do not believe in those two things, I do not think that you can properly call yourself a Christian. Then, further than that, as the name implies, you must have some kind of belief about Christ. The Mohammedans, for instance, also believe in God and in immortality, and yet they would not call themselves Christians. I think you must have at the very lowest the belief that Christ was, if not divine, at least the best and wisest of men. If you are not going to believe that much about Christ, I do not think you have any right to call yourself a Christian. Of course, there is another sense, which you find in Whitaker's Almanack and in geography books, where the population of the world is said to be divided into Christians, Mohammedans, Buddhists, fetish worshipers, and so on; and in that sense we are all Christians. The geography books count us all in, but that is a purely geographical sense, which I suppose we canignore.Therefore I take it that when I tell you why I am not a Christian I have to tell you two different things: first, why I do not believe in God and in immortality; and, secondly, why I do not think that Christ was the best and wisest of men, although I grant him a very high degree of moral goodness.But for the successful efforts of unbelievers in the past, I could not take so elastic a definition of Christianity as that. As I said before, in olden days it had a much more full-blooded sense. For instance, it included he belief in hell. Belief in eternal hell-fire was an essential item of Christian belief until pretty recent times. In this country, as you know, it ceased to be an essential item because of a decision of the Privy Council, and from that decision the Archbishop of Canterbury and the Archbishop of York dissented; but in this country our religion is settled by Act of Parliament, and therefore the Privy Council was able to override their Graces and hell was no longer necessary to a Christian. Consequently I shall not insist that a Christian must believe in hell.The Existence of GodTo come to this question of the existence of God: it is a large and serious question, and if I were to attempt to deal with it in any adequate manner I should have to keep you here until Kingdom Come, so that you will have to excuse me if I deal with it in a somewhat summary fashion. You know, of course, that the Catholic Church has laid it down as a dogma that the existence of God can be proved by the unaided reason. That is a somewhat curious dogma, but it is one of their dogmas. They had to introduce it because at one time the freethinkers adopted the habit of saying that there were such and such arguments which mere reason might urge against the existence of God, but of course they knew as a matter of faith that God did exist. The arguments and the reasons were set out at great length, and the Catholic Church felt that they must stop it. Therefore they laid it down that the existence of God can be proved by the unaided reason and they had to set up what they considered were arguments to prove it. There are, of course, a number of them, but I shall take only a few.The First-cause ArgumentPerhaps the simplest and easiest to understand is the argument of the First Cause. (It is maintained that everything we see in this world has a cause, and as you go back in the chain of causes further and further you must come to a First Cause, and to that First Cause you give the name of God.) That argument, I suppose, does not carry very much weight nowadays, because,in the first place, cause is not quite what it used to be. The philosophers and the men of science have got going on cause, and it has not anything like the vitality it used to have; but, apart from that, you can see that the argument that there must be a First Cause is one that cannot have any validity. I may say that when I was a young man and was debating these questions very seriously in my mind, I for a long time accepted the argument of the First Cause, until one day, at the age of eighteen, I read John Stuart Mill's Autobiography, and I there found this sentence: "My father taught me that the question 'Who made me?' cannot be answered, since it immediately suggests the further question `Who made god?'" That very simple sentence showed me, as I still think, the fallacy in the argument of the First Cause. If everything must have a cause, then God must have a cause. If there can be anything without a cause, it may just as well be the world as God, so that there cannot be any validity in that argument. It is exactly of the same nature as the Hindu's view, that the world rested upon an elephant and the elephant rested upon a tortoise; and when they said, "How about the tortoise?" the Indian said, "Suppose we change the subject." The argumentis really no better than that. There is no reason why the world could not have come into being without a cause; nor, on the other hand, is there any reason why it should not have always existed. There is no reason to suppose that the world had a beginning at all. The idea that things must have a beginning is really due to the poverty of our imagination. Therefore, perhaps, I need not waste any more time upon the argument about the First Cause.The Natural-law ArgumentThen there is a very common argument from natural law. That was a favorite argument all through the eighteenth century, especially under the influence of Sir Isaac Newton and his cosmogony. People observed the planets going around the sun according to the law of gravitation, and they thought that God had given a behest to these planets to move in that particular fashion, and that was why they did so. That was, of course, a convenient and simple explanation that saved them the trouble of looking any further for explanations of the law of gravitation. Nowadays we explain the law of gravitation in a somewhat complicated fashion that Einstein has introduced. I do not propose to give you a lecture on the law of gravitation, as interpreted by Einstein, because that again would take some time; at any rate, you no longer have the sort of natural law that you had in the Newtonian system, where, for some reason that nobody could understand, nature behaved in a uniform fashion. We now find that a great many things we thought were natural laws are really human conventions. You know that even in the remotest depths of stellar space there are still three feet to a yard. That is, no doubt, a very remarkable fact, but you would hardly call it a law of nature. And a great many things that have been regarded as laws of nature are of that kind. On the other hand, where you can get down to any knowledge of what atoms actually do, you will find they are much less subject to law than people thought, and that the laws at which you arrive are statistical averages of just the sort that would emerge from chance. There is, as we all know, a law that if you throw dice you will get double sixes only about once in thirty-six times, and we do not regard that as evidence that the fall of the dice is regulated by design; on the contrary, if the double sixes came every time we should think that there was design. The laws of nature are of that sort as regards a great many of them. They are statistical averages such as would emerge from the laws of chance; and that makes this whole business of natural law much less impressive than it formerly was. Quite apart from that, which represents the momentary state of science that may change tomorrow, the whole idea that natural laws imply a lawgiver is due to a confusion between natural and human laws. Human laws are behests commanding you to behave a certain way, in which you may choose to behave, or you may choose not to behave; but natural laws are a description of how things do in fact behave, and being a mere description of what they in fact do, you cannot argue that there must be somebody who told them to do that, because even supposing that there were, you are then faced with the question "Why did God issue just those natural laws and no others?" If you say that he did it simply from his own good pleasure, and without any reason, you then find that there is something which is not subject to law, and so your train of natural law is interrupted. If you say, as more orthodox theologians do, that in all the laws which God issues he had a reason for giving those laws rather than others -- the reason, of course, being to create the best universe, although you would never think it to look at it -- if there were a reason for the laws which God gave, then God himself was subject to law, and therefore you do not get any advantage by introducing God as an intermediary. You really have a law outside and anterior to the divine edicts, and God doesnot serve your purpose, because he is not the ultimate lawgiver. In short, this whole argument about natural law no longer has anything like the strength that it used to have. I am traveling on in time in my review of the arguments. The arguments that are used for the existence of God change their character as time goes on. They were at first hard intellectual arguments embodying certain quite definite fallacies. As we come to modern times they become less respectable intellectually and more and more affected by a kind of moralizing vagueness.The Argument from DesignThe next step in the process brings us to the argument from design. You all know the argument from design: everything in the world is made just so that we can manage to live in the world, and if the world was ever so little different, we could not manage to live in it. That is the argument from design. It sometimes takes a rather curious form; for instance, it is argued that rabbits have white tails in order to be easy to shoot. I do not know how rabbits would view that application. It is an easy argument to parody. You all know Voltaire's remark, that obviously the nose was designed to be such as to fit spectacles. That sort of parody has turned out to be not nearly so wide of the mark as it might have seemed in the eighteenth century, because since the time of Darwin we understand much better why living creatures are adapted to their environment. It is not that their environment was made to be suitable to them but that they grew to be suitable to it, and that is the basis of adaptation. There is no evidence of design about it.When you come to look into this argument from design, it is a most astonishing thing that people can believe that this world, with all the things that are in it, with all its defects, should be the best that omnipotence and omniscience have been able to produce in millions of years. I really cannot believe it. Do you think that, if you were granted omnipotence and omniscience and millions of years in which to perfect your world, you could produce nothing better than the Ku Klux Klan or the Fascists? Moreover, if you accept the ordinary laws of science, you have to suppose that human life and life in general on this planet will die out in due course: it is a stage in the decay of the solar system; at a certain stage of decay you get the sort of conditions of temperature and so forth which are suitable to protoplasm, and there is life for a short time in the life of the whole solar system. You see in the moon the sort of thing to which the earth is tending -- something dead, cold, and lifeless.I am told that that sort of view is depressing, and people will sometimes tell you that if they believed that, they would not be able to go on living. Do not believe it; it is all nonsense. Nobody really worries about much about what is going to happen millions of years hence. Even if they think they are worrying much about that, they are really deceiving themselves. They are worried about something much more mundane, or it may merely be a bad digestion; but nobody is really seriously rendered unhappy by the thought of something that is going to happen to this world millions and millions of years hence. Therefore, although it is of course a gloomy view to suppose that life will die out -- at least I suppose we may say so, although sometimes when I contemplate the things that people do with their lives I think it is almost a consolation -- it is not such as to render life miserable. It merely makes you turn your attention to other things.The Moral Arguments for DeityNow we reach one stage further in what I shall call the intellectual descent that the Theists have made in their argumentations, and we come to what are called the moral arguments for the existence of God. You all know, of course, that there used to be in the old days three intellectual arguments for the existence of God, all of which were disposed of by Immanuel Kant in the Critique of Pure Reason; but no sooner had he disposed of those arguments than he invented a new one, a moral argument, and that quite convinced him. He was like many people: in intellectual matters he was skeptical, but in moral matters he believed implicitly in the maxims that he had imbibed at his mother's knee. That illustrates what the psychoanalysts so much emphasize -- the immensely stronger hold upon us that our very early associations have than those of later times.Kant, as I say, invented a new moral argument for the existence of God, and that in varying forms was extremely popular during the nineteenth century. It has all sorts of forms. One form is to say there would be no right or wrong unless God existed. I am not for the moment concerned with whether there is a difference between right and wrong, or whether there is not: that is another question. The point I am concerned with is that, if you are quite sure there is a difference between right and wrong, then you are in this situation: Is that difference due to God's fiat or is it not? If it is due to God's fiat, then for God himself there is no difference between right and wrong, and it is no longer a significant statement to say that God is good. If you are going to say, as theologians do, that God is good, you must then say that right and wrong have some meaning which is independent of God's fiat, because God's fiats are good and not bad independently of the mere fact that he made them. If you are going to say that, you will then have to say that it is not only through God that right and wrong came into being, but that they are in their essence logically anterior to God. You could, of course, if you liked, say that there was a superior deity who gave orders to the God that made this world, or could take up the line that some of the gnostics took up -- a line which I often thought was a very plausible one -- that as a matter of fact this world that we know was made by the devil at a moment when God was not looking. There is a good deal to be said for that, and I am not concerned to refute it.The Argument for the Remedying of InjusticeThen there is another very curious form of moral argument, which is this: they say that the existence of God is required in order to bring justice into the world. In the part of this universe that we know there is great injustice, and often the good suffer, and often the wicked prosper, and one hardly knows which of those is the more annoying; but if you are going to have justice in the universe as a whole you have to suppose a future life to redress the balance of life here on earth. So they say that there must be a God, and there must be Heaven and Hell in order that in the long run there may be justice. That is a very curious argument. If you looked at the matter from a scientific point of view, you would say, "After all, I only know this world. I do not know about the rest of the universe, but so far as one can argue at all on probabilities one would say that probably this world is a fair sample, and if there is injustice here the odds are that there is injustice elsewhere also." Supposing you got a crate of oranges that you opened, and you found all the top layer of oranges bad, you would not argue, "The underneath ones must be good, so asto redress the balance." You would say, "Probably the whole lot is a bad consignment"; and that is really what a scientific person would argue about the universe. He would say, "Here we find in this world a great deal of injustice, and so far as that goes that is a reason for supposing that justice does not rule in the world; and therefore so far as it goes it affords a moral argument against deity and not in favor of one." Of course I know that the sort of intellectual arguments that I have been talking to you about are not what really moves people. What really moves people to believe in God is not any intellectual argument at all. Most people believe in God because they have been taught from early infancy to do it, and that is the main reason.Then I think that the next most powerful reason is the wish for safety, a sort of feeling that there is a big brother who will look after you. That plays a very profound part in influencing people's desire for a belief in God.The Character of ChristI now want to say a few words upon a topic which I often think is not quite sufficiently dealt with by Rationalists, and that is the question whether Christ was the best and the wisest of men. It is generally taken for granted that we should all agree that that was so. I do not myself. I think that there are a good many points upon which I agree with Christ a great deal more than the professing Christians do. I do not know that I could go with Him all the way, but I could go with Him much further than most professing Christians can. You will remember that He said, "Resist not evil: but whosoever shall smite thee on thy right cheek, turn to him the other also." That is not a new precept or a new principle. It was used by Lao-tse and Buddha some 500 or 600 years before Christ, but it is not a principle which as a matter of fact Christians accept. I have no doubt that the present prime minister [Stanley Baldwin], for instance, is a most sincere Christian, but I should not advise any of you to go and smite him on one cheek. I think you might find that he thought this text was intended in a figurative sense.Then there is another point which I consider excellent. You will remember that Christ said, "Judge not lest ye be judged." That principle I do not think you would find was popular in the law courts of Christian countries. I have known in my time quite a number of judges who were very earnest Christians, and none of them felt that they were acting contrary to Christian principles in what they did. Then Christ says, "Give to him that asketh of thee, and from him that would borrow of thee turn not thou away." That is a very good principle. Your Chairman has reminded you that we are not here to talk politics, but I cannot help observing that the last general election was fought on the question of how desirable it was to turn away from him that would borrow of thee, so that one must assume that the Liberals and Conservatives of this country are composed of people who do not agree with the teaching of Christ, because they certainly did very emphatically turn away on that occasion.Then there is one other maxim of Christ which I think has a great deal in it, but I do not find that it is very popular among some of our Christian friends. He says, "If thou wilt be perfect, go and sell that which thou hast, and give to the poor." That is a very excellent maxim, but, as I say, it is not much practised. All these, I think, are good maxims, although they are a little difficult to live up to. I do not profess to live up to them myself; but then, after all, it is not quite the same thingas for a Christian.Defects in Christ's TeachingHaving granted the excellence of these maxims, I come to certain points in which I do not believe that one can grant either the superlative wisdom or the superlative goodness of Christ as depicted in the Gospels; and here I may say that one is not concerned with the historical question. Historically it is quite doubtful whether Christ ever existed at all, and if He did we do not know anything about him, so that I am not concerned with the historical question, which is a very difficult one. I am concerned with Christ as He appears in the Gospels, taking the Gospel narrative as it stands, and there one does find some things that do not seem to be very wise. For one thing, he certainly thought that His second coming would occur in clouds of glory before the death of all the people who were living at that time. There are a great many texts that prove that. He says, for instance, "Ye shall not have gone over the cities of Israel till the Son of Man be come." Then he says, "There are some standing here which shall not taste death till the Son of Man comes into His kingdom"; and there are a lot of places where it is quite clear that He believed that His second coming would happen during the lifetime of many then living. That was the belief of His earlier followers, and it was the basis of a good deal of His moral teaching. When He said, "Take no thought for the morrow," and things of that sort, it was very largely because He thought that the second coming was going to be very soon, and that all ordinary mundane affairs did not count. I have, as a matter of fact, known some Christians who did believe that the second coming was imminent. I knew a parson who frightened his congregation terribly by telling them that the second coming was very imminent indeed, but they were much consoled when they found that he was planting trees in his garden. The early Christians did really believe it, and they did abstain from such things as planting trees in their gardens, because they did accept from Christ the belief that the second coming was imminent. In that respect, clearly He was not so wise as some other people have been, and He was certainly not superlatively wise.The Moral ProblemThen you come to moral questions. There is one very serious defect to my mind in Christ's moral character, and that is that He believed in hell. I do not myself feel that any person who is really profoundly humane can believe in everlasting punishment. Christ certainly as depicted in the Gospels did believe in everlasting punishment, and one does find repeatedly a vindictive fury against those people who would not listen to His preaching -- an attitude which is not uncommon with preachers, but which does somewhat detract from superlative excellence. You do not, for instance find that attitude in Socrates. You find him quite bland and urbane toward the people who would not listen to him; and it is, to my mind, far more worthy of a sage to take that line than to take the line of indignation. You probably all remember the sorts of things that Socrates was saying when he was dying, and the sort of things that he generally did say to people who did not agree with him.You will find that in the Gospels Christ said, "Ye serpents, ye generation of vipers, how can ye escape the damnation of Hell." That was said to people who did not like His preaching. It is not really to my mind quite the best tone, and there are a great many of these things about Hell. There is, of course, the familiar text about the sin against the Holy Ghost: "Whosoever speaketh against the Holy Ghost it shall not be forgiven him neither in this World nor in the world to come." That text has caused an unspeakable amount of misery in the world, for all sorts of people have imagined that they have committed the sin against the Holy Ghost, and thought that it would not be forgiven them either in this world or in the world to come. I really do not think that a person with a proper degree of kindliness in his nature would have put fears and terrors of that sort into the world.Then Christ says, "The Son of Man shall send forth his His angels, and they shall gather out of His kingdom all things that offend, and them which do iniquity, and shall cast them into a furnace of fire; there shall be wailing and gnashing of teeth"; and He goes on about the wailing and gnashing of teeth. It comes in one verse after another, and it is quite manifest to the reader that there is a certain pleasure in contemplating wailing and gnashing of teeth, or else it would not occur so often. Then you all, of course, remember about the sheep and the goats; how at the second coming He is going to divide the sheep from the goats, and He is going to say to the goats, "Depart from me, ye cursed, into everlasting fire." He continues, "And these shall go away into everlasting fire." Then He says again, "If thy hand offend thee, cut it off; it is better for thee to enter into life maimed, than having two hands to go into Hell, into the fire that never shall be quenched; where the worm dieth not and the fire is not quenched." He repeats that again and again also. I must say that I think all this doctrine, that hell-fire is a punishment for sin, is a doctrine of cruelty. It is a doctrine that put cruelty into the world and gave the world generations of cruel torture; and the Christ of the Gospels, if you could take Him asHis chroniclers represent Him, would certainly have to be considered partly responsible for that.There are other things of less importance. There is the instance of the Gadarene swine, where it certainly was not very kind to the pigs to put the devils into them and make them rush down the hill into the sea. You must remember that He was omnipotent, and He could have made the devils simply go away; but He chose to send them into the pigs. Then there is the curious story of the fig tree, which always rather puzzled me. You remember what happened about the fig tree. "He was hungry; and seeing a fig tree afar off having leaves, He came if haply He might find anything thereon; and when He came to it He found nothing but leaves, for the time of figs was not yet. And Jesus answered and said unto it: 'No man eat fruit of thee hereafter for ever' . . . and Peter . . . saith unto Him: 'Master, behold the fig tree which thou cursedst is withered away.'" This is a very curious story, because it was not the right time of year for figs, and you really could not blame the tree. I cannot myself feel that either in the matter of wisdom or in the matter of virtue Christ stands quite as high as some other people known to history. I think I should put Buddha and Socrates above Him in those respects.The Emotional FactorAs I said before, I do not think that the real reason why people accept religion has anything to do with argumentation. They accept religion on emotional grounds. One is often told that it is a very。

Russell, Bertrand - What is the Soul

What Is the Soul?Bertrand Russell1928One of the most painful circumstances of recent advances in science is that each one makes us know less than we thought we did. When I was young we all knew, or thought we knew, that a man consists of a soul and a body; that the body is in time and space, but the soul is in time only. Whether the soul survives death was a matter as to which opinions might differ, but that there is a soul was thought to be indubitable. As for the body, the plain man of course considered its existence self-evident, and so did the man of science, but the philosopher was apt to analyse it away after one fashion or another, reducing it usually to ideas in the mind of the man who had the body and anybody else who happened to notice him. The philosopher, however, was not taken seriously, and science remained comfortably materialistic, even in the h ands of quite orthodox scientists.Nowadays these fine old simplicities are lost: physicists assure us that there is no such thing as matter, and psychologists assure us that there is no such thing as mind. This is an unprecedented occurrence. Who ever heard of a cobbler saying that there was no such thing as boots, or a tailor maintaining that all men are really naked? Yet that would have been no odder than what physicists and certain psychologists have been doing. To begin with the latter, some of them attempt to reduce everything that seems to be mental activity to an activity of the body. There are, however, various difficulties in the way of reducing mental activity to physical activity. I do not think we can yet say with any assurance whether these difficulties are or are not insuperable. What we can say, on the basis of physics itself, is that what we have hitherto called our body is really an elaborate scientific construction not corresponding to any physical reality. The modern would-be materialist thus finds himself in a curious position, for, while he may with a certaindegree of success reduce the activities of the mind to those of the body, he cannot explain away the fact that the body itself is merely a convenient concept invented by the mind. We find ourselves thus going round and round in a circle: mind is an emanation of body, and body is an invention of mind. Evidently this cannot be quite right, and we have to look for something that is neither mind nor body, out which both can spring.Let us begin with the body. The plain man thinks that material objects must certainly exist, since they are evident to the senses. Whatever else may be doubted, it is certain that anything you can bump into must be real; this is the plain man's metaphysic. This is all very well, but the physicist comes along and shows that you never bump into anything: even when you run your hand along a stone wall, you do not really touch it. When you think you touch a thing, there are certain electrons and protons, forming part of your body, which are attracted and repelled by certain electrons and protons in the thing you think you are touching, but there is no actual contact. The electrons and protons in your body, becoming agitated by nearness to the other electrons and protons are disturbed, and transmit a disturbance along your nerves to the brain; the effect in the brain is what is necessary to your sensation of contact, and by suitable experiments this sensation can be made quite deceptive. The electrons and protons themselves, however, are only crude first approximations, a way of collecting into a bundle either trains of waves or the statistical probabilities of various different kinds of events. Thus matter has become altogether too ghostly to be used as an adequate stick with which to beat the mind. Matter in motion, which used to seem so unquestionable, turns out to be a concept quite inadequate for the needs of physics.Nevertheless modern science gives no indication whatever of the existence of the soul or mind as an entity; indeed the reasons for disbelieving in it are very much of the same kind as the reasons for disbelieving in matter. Mind and matter were something like the lion and the unicorn fighting for the crown; the end of the battle is not the victory of one or the other, but the discovery that both are only heraldic inventions. The world consists of events, not of things that endure for a long time and have changing properties. Events can be collected into groups by their causal relations. If the causal relations are of one sort, the resulting group of events may be called a physical object, and if the causal relations are of another sort, the resulting group may be called a mind. Any event that occurs inside a man's head will belong to groups of both kinds; considered as belonging to a group of one kind, it is a constituent of his brain, and considered as belonging to a group of the other kind, it is a constituent of his mind.Thus both mind and matter are merely convenient ways of organizing events. There can be no reason for supposing that either a piece of mind or a piece of matter is immortal. The sun is supposed to be losing matter at the rate of millions of tons a minute. The most essential characteristic of mind is memory, and there is no reason whatever to suppose that the memory associated with a given person survives that person's death. Indeed there is every reason to think the opposite, for memory is clearly connected with a certain kind of brain structure, and since this structure decays at death, there is every reason to suppose that memory also must cease. Although metaphysical materialism cannot be considered true, yet emotionally the world is pretty much the same as I would be if thematerialists were in the right. I think the opponents of materialism have always been actuated by two main desires: the first to prove that the mind is immortal, and the second to prove that the ultimate power in the universe is mental rather than physical. In both these respects, I think the materialists were in the right. Our desires, it is true, have considerable power on the earth's surface; the greater part of the land on this planet has a quite different aspect from that which it would have if men had not utilized it to extract food and wealth. But our power is very strictly limited. We cannot at present do anything whatever to the sun or moon or even to the interior of the earth, and there is not the faintest reason to suppose that what happens in regions to which our power does not extend has any mental cau ses. That is to say, to put the matter in a nutshell, there is no reason to think that except on the earth's surface anything happens because somebody wishes it to happen. And since our power on the earth's surface is entirely dependent upon the sun, we could hardly realize any of our wishes if the sun grew could. It is of course rash to dogmatize as to what science may achieve in the future. We may learn to prolong human existence longer than now seems possible, but if there is any truth in modern physics, more particularly in the second law of thermodynamics, we cannot hope that the human race will continue for ever. Some people may find this conclusion gloomy, but if we are honest with ourselves, we shall have to admit that what is going to happen many millions of years hence has no very great emotional interest for us here and now. And science, while it diminishes our cosmic pretensions, enormously increases our terrestrial comfort. That is why, in spite of the horror of the theologians, science has on the whole been tolerated.。

英语美文欣赏how+to+grow+old(new)

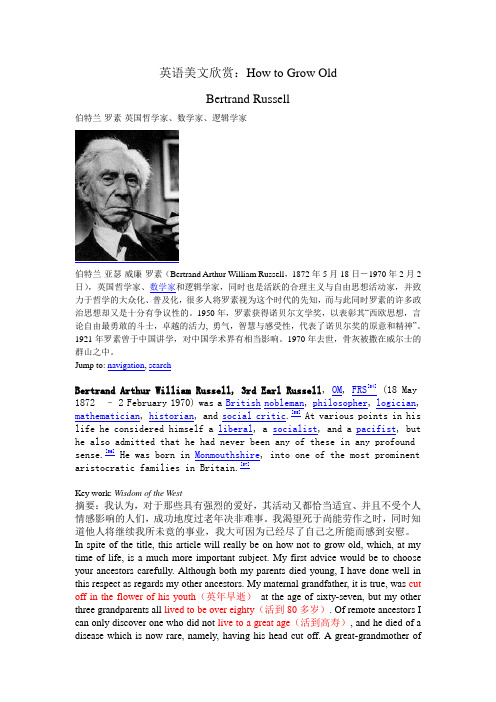

英语美文欣赏:How to Grow OldBertrand Russell伯特兰·罗素-英国哲学家、数学家、逻辑学家伯特兰·亚瑟·威廉·罗素(Bertrand Arthur William Russell,1872年5月18日-1970年2月2日),英国哲学家、数学家和逻辑学家,同时也是活跃的合理主义与自由思想活动家,并致力于哲学的大众化、普及化,很多人将罗素视为这个时代的先知,而与此同时罗素的许多政治思想却又是十分有争议性的。

1950年,罗素获得诺贝尔文学奖,以表彰其“西欧思想,言论自由最勇敢的斗士,卓越的活力, 勇气,智慧与感受性,代表了诺贝尔奖的原意和精神”。

1921年罗素曾于中国讲学,对中国学术界有相当影响。

1970年去世,骨灰被撒在威尔士的群山之中。

Jump to: navigation, searchBertrand Arthur William Russell, 3rd Earl Russell, OM, FRS[54] (18 May 1872 –2 February 1970) was a British nobleman, philosopher, logician, mathematician, historian, and social critic.[55] At various points in his life he considered himself a liberal, a socialist, and a pacifist, but he also admitted that he had never been any of these in any profound sense.[56] He was born in Monmouthshire, into one of the most prominent aristocratic families in Britain.[57]Key work: Wisdom of the West摘要:我认为,对于那些具有强烈的爱好,其活动又都恰当适宜、并且不受个人情感影响的人们,成功地度过老年决非难事。

Quotations of Bertrand Russell 罗素的名言名句

罗素的名言名句Bertrand Russell QUOTES / QUOTATIONSA hallucination is a fact, not an error; what is erroneous is a judgment based upon it.Quotation of Bertrand RussellA happy life must be to a great extent a quiet life, for it is only in an atmosphere of quiet that true joy dare live.Quotation of Bertrand RussellA life without adventure is likely to be unsatisfying, but a life in which adventure is allowed to take whatever form it will is sure to be short.Quotation of Bertrand RussellA process which led from the amoeba to man appeared to the philosophers to be obviously a progress though whether the amoeba would agree with this opinion is not known.Quotation of Bertrand RussellA sense of duty is useful in work but offensive in personal relations. People wish to be liked, not to be endured with patient resignation.Quotation of Bertrand RussellAdmiration of the proletariat, like that of dams, power stations, and aeroplanes, is part of the ideology of the machine age.Quotation of Bertrand RussellAgainst my will, in the course of my travels, the belief that everything worth knowing was known at Cambridge gradually wore off. In this respect my travels were very useful to me.Quotation of Bertrand RussellAll movements go too far.Quotation of Bertrand RussellAlmost everything that distinguishes the modern world from earlier centuries is attributable to science, which achieved its most spectacular triumphs in the seventeenth century.Quotation of Bertrand RussellAnything you're good at contributes to happiness.Quotation of Bertrand RussellAristotle could have avoided the mistake of thinking that women have fewer teeth than men, by the simple device of asking Mrs. Aristotle to keep her mouth open while he counted.Quotation of Bertrand RussellAristotle maintained that women have fewer teeth than men; although he was twice married, it never occurred to him to verify this statement by examining his wives' mouths.Quotation of Bertrand RussellAwareness of universals is called conceiving, and a universal of which we are aware is called a concept.Quotation of Bertrand RussellBoredom is a vital problem for the moralist, since at least half the sins of mankind are caused by the fear of it.Quotation of Bertrand RussellBoredom is... a vital problem for the moralist, since half the sins of mankind are caused by the fear of it.Quotation of Bertrand RussellBoth in thought and in feeling, even though time be real, to realise the unimportance of time is the gate of wisdom.Quotation of Bertrand RussellCollective fear stimulates herd instinct, and tends to produce ferocity toward those who are not regarded as members of the herd.Quotation of Bertrand RussellContempt for happiness is usually contempt for other people's happiness, and is an elegant disguise for hatred of the human race.Quotation of Bertrand RussellConventional people are roused to fury by departure from convention, largely because they regard such departure as a criticism of themselves.Quotation of Bertrand RussellDemocracy is the process by which people choose the man who'll get the blame.Quotation of Bertrand RussellDo not fear to be eccentric in opinion, for every opinion now accepted was once eccentric. Quotation of Bertrand RussellDrunkenness is temporary suicide.Quotation of Bertrand RussellEthics is in origin the art of recommending to others the sacrifices required for cooperation with oneself.Quotation of Bertrand RussellExtreme hopes are born from extreme misery.Quotation of Bertrand RussellFear is the main source of superstition, and one of the main sources of cruelty. To conquer fear is the beginning of wisdom.Quotation of Bertrand RussellFreedom comes only to those who no longer ask of life that it shall yield them any of those personal goods that are subject to the mutations of time.Quotation of Bertrand RussellFreedom in general may be defined as the absence of obstacles to the realization of desires. Quotation of Bertrand RussellFreedom of opinion can only exist when the government thinks itself secure.Quotation of Bertrand RussellI believe in using words, not fists. I believe in my outrage knowing people are living in boxes on the street. I believe in honesty. I believe in a good time. I believe in good food. I believe in sex. Quotation of Bertrand RussellI do not pretend to start with precise questions. I do not think you can start with anything precise. You have to achieve such precision as you can, as you go along.Quotation of Bertrand RussellI like mathematics because it is not human and has nothing particular to do with this planet or with the whole accidental universe - because, like Spinoza's God, it won't love us in return. Quotation of Bertrand RussellI remain convinced that obstinate addiction to ordinary language in our private thoughts is one of the main obstacles to progress in philosophy.Quotation of Bertrand RussellI say quite deliberately that the Christian religion, as organized in its Churches, has been and still is the principal enemy of moral progress in the world.Quotation of Bertrand RussellI think we ought always to entertain our opinions with some measure of doubt. I shouldn't wish people dogmatically to believe any philosophy, not even mine.Quotation of Bertrand RussellI would never die for my beliefs because I might be wrong.Quotation of Bertrand RussellI've made an odd discovery. Every time I talk to a savant I feel quite sure that happiness is no longer a possibility. Yet when I talk with my gardener, I'm convinced of the opposite.Quotation of Bertrand RussellIf all our happiness is bound up entirely in our personal circumstances it is difficult not to demand of life more than it has to give.Quotation of Bertrand RussellIf there were in the world today any large number of people who desired their own happiness more than they desired the unhappiness of others, we could have a paradise in a few years.Quotation of Bertrand RussellIn all affairs it's a healthy thing now and then to hang a question mark on the things you have long taken for granted.Quotation of Bertrand RussellIn America everybody is of the opinion that he has no social superiors, since all men are equal, but he does not admit that he has no social inferiors, for, from the time of Jefferson onward, the doctrine that all men are equal applies only upwards, not downwards.Quotation of Bertrand RussellIn America everybody is of the opinion that he has no social superiors, since all men are equal, but he does not admit that he has no social inferiors.Quotation of Bertrand RussellIn the revolt against idealism, the ambiguities of the word experience have been perceived, with the result that realists have more and more avoided the word.Quotation of Bertrand RussellIndignation is a submission of our thoughts, but not of our desires.Quotation of Bertrand RussellIt has been said that man is a rational animal. All my life I have been searching for evidence which could support this.Quotation of Bertrand RussellIt is possible that mankind is on the threshold of a golden age; but, if so, it will be necessary first to slay the dragon that guards the door, and this dragon is religion.Quotation of Bertrand RussellIt is preoccupation with possessions, more than anything else, that prevents us from living freely and nobly.Quotation of Bertrand RussellIt seems to be the fate of idealists to obtain what they have struggled for in a form which destroys their ideals.Quotation of Bertrand RussellItaly, and the spring and first love all together should suffice to make the gloomiest person happy. Quotation of Bertrand RussellLiberty is the right to do what I like; license, the right to do what you like.Quotation of Bertrand RussellLife is nothing but a competition to be the criminal rather than the victim.Quotation of Bertrand RussellLove is something far more than desire for sexual intercourse; it is the principal means of escape from the loneliness which afflicts most men and women throughout the greater part of their lives. Quotation of Bertrand RussellMachines are worshipped because they are beautiful and valued because they confer power; they are hated because they are hideous and loathed because they impose slavery.Quotation of Bertrand RussellMan is a credulous animal, and must believe something; in the absence of good grounds for belief, he will be satisfied with bad ones.Quotation of Bertrand RussellMan needs, for his happiness, not only the enjoyment of this or that, but hope and enterprise and change.Quotation of Bertrand RussellMany a man will have the courage to die gallantly, but will not have the courage to say, or even to think, that the cause for which he is asked to die is an unworthy one.Quotation of Bertrand RussellMany people would sooner die than think; in fact, they do so.Quotation of Bertrand RussellMarriage is for women the commonest mode of livelihood, and the total amount of undesired sex endured by women is probably greater in marriage than in prostitution.Quotation of Bertrand RussellMathematics may be defined as the subject in which we never know what we are talking about, nor whether what we are saying is true.Quotation of Bertrand RussellMathematics takes us into the region of absolute necessity, to which not only the actual word, but every possible word, must conform.Quotation of Bertrand RussellMen are born ignorant, not stupid. They are made stupid by education.Quotation of Bertrand RussellMen who are unhappy, like men who sleep badly, are always proud of the fact.Quotation of Bertrand RussellMost people would sooner die than think; in fact, they do so.Quotation of Bertrand RussellMuch that passes as idealism is disguised hatred or disguised love of power.Quotation of Bertrand RussellNeither a man nor a crowd nor a nation can be trusted to act humanely or to think sanely under the influence of a great fear.Quotation of Bertrand RussellNext to enjoying ourselves, the next greatest pleasure consists in preventing others from enjoying themselves, or, more generally, in the acquisition of power.Quotation of Bertrand RussellNo one gossips about other people's secret virtues.Quotation of Bertrand RussellNo; we have been as usual asking the wrong question. It does not matter a hoot what the mockingbird on the chimney is singing. The real and proper question is: Why is it beautiful? Quotation of Bertrand RussellNone but a coward dares to boast that he has never known fear.Quotation of Bertrand RussellObscenity is whatever happens to shock some elderly and ignorant magistrate.Quotation of Bertrand RussellOf all forms of caution, caution in love is perhaps the most fatal to true happiness.Quotation of Bertrand RussellOne of the symptoms of an approaching nervous breakdown is the belief that one's work is terribly important.Quotation of Bertrand RussellOne should respect public opinion insofar as is necessary to avoid starvation and keep out of prison, but anything that goes beyond this is voluntary submission to an unnecessary tyranny. Quotation of Bertrand RussellOrder, unity, and continuity are human inventions, just as truly as catalogues and encyclopedias. Quotation of Bertrand RussellPatriotism is the willingness to kill and be killed for trivial reasons.Quotation of Bertrand RussellPatriots always talk of dying for their country and never of killing for their country.Quotation of Bertrand RussellReason is a harmonising, controlling force rather than a creative one.Quotation of Bertrand RussellReligion is something left over from the infancy of our intelligence, it will fade away as we adopt reason and science as our guidelines.Quotation of Bertrand RussellReligions that teach brotherly love have been used as an excuse for persecution, and our profoundest scientific insight is made into a means of mass destruction.Quotation of Bertrand RussellReligions, which condemn the pleasures of sense, drive men to seek the pleasures of power. Throughout history power has been the vice of the ascetic.Quotation of Bertrand RussellRight discipline consists, not in external compulsion, but in the habits of mind which lead spontaneously to desirable rather than undesirable activities.Quotation of Bertrand RussellScience is what you know, philosophy is what you don't know.Quotation of Bertrand RussellSin is geographical.Quotation of Bertrand RussellSo far as I can remember, there is not one word in the Gospels in praise of intelligence. Quotation of Bertrand RussellThe coward wretch whose hand and heart Can bear to torture aught below, Is ever first to quail and start From the slightest pain or equal foe.Quotation of Bertrand RussellThe degree of one's emotions varies inversely with one's knowledge of the facts.Quotation of Bertrand RussellThe demand for certainty is one which is natural to man, but is nevertheless an intellectual vice. Quotation of Bertrand RussellThe fact that an opinion has been widely held is no evidence whatever that it is not utterly absurd. Quotation of Bertrand RussellThe fundamental concept in social science is Power, in the same sense in which Energy is the fundamental concept in physics.Quotation of Bertrand RussellThe fundamental defect of fathers, in our competitive society, is that they want their children to be a credit to them.Quotation of Bertrand RussellThe good life is one inspired by love and guided by knowledge.Quotation of Bertrand RussellThe infliction of cruelty with a good conscience is a delight to moralists. That is why they invented Hell.Quotation of Bertrand RussellThe most savage controversies are about matters as to which there is no good evidence either way. Quotation of Bertrand RussellThe most savage controversies are those about matters as to which there is no good evidence either way. Persecution is used in theology, not in arithmetic.Quotation of Bertrand RussellThe observer, when he seems to himself to be observing a stone, is really, if physics is to be believed, observing the effects of the stone upon himself.Quotation of Bertrand RussellThe only thing that will redeem mankind is cooperation.Quotation of Bertrand RussellThe place of the father in the modern suburban family is a very small one, particularly if he plays golf.Quotation of Bertrand RussellThe point of philosophy is to start with something so simple as not to seem worth stating, and to end with something so paradoxical that no one will believe it.Quotation of Bertrand RussellThe secret of happiness is this: let your interests be as wide as possible, and let your reactions to the things and persons that interest you be as far as possible friendly rather than hostile. Quotation of Bertrand RussellThe secret to happiness is to face the fact that the world is horrible.Quotation of Bertrand RussellThe slave is doomed to worship time and fate and death, because they are greater than anything he finds in himself, and because all his thoughts are of things which they devour.Quotation of Bertrand RussellThe theoretical understanding of the world, which is the aim of philosophy, is not a matter of great practical importance to animals, or to savages, or even to most civilised men.Quotation of Bertrand RussellThe time you enjoy wasting is not wasted time.Quotation of Bertrand RussellThe trouble with the world is that the stupid are cocksure and the intelligent are full of doubt. Quotation of Bertrand RussellThe true spirit of delight, the exaltation, the sense of being more than Man, which is the touchstone of the highest excellence, is to be found in mathematics as surely as poetry. Quotation of Bertrand RussellThe universe may have a purpose, but nothing we know suggests that, if so, this purpose has any similarity to ours.Quotation of Bertrand RussellThe whole problem with the world is that fools and fanatics are always so certain of themselves, and wiser people so full of doubts.Quotation of Bertrand RussellThe world is full of magical things patiently waiting for our wits to grow sharper.Quotation of Bertrand RussellThere is much pleasure to be gained from useless knowledge.Quotation of Bertrand RussellThere is no need to worry about mere size. We do not necessarily respect a fat man more than athin man. Sir Isaac Newton was very much smaller than a hippopotamus, but we do not on that account value him less.Quotation of Bertrand RussellThere is something feeble and a little contemptible about a man who cannot face the perils of life without the help of comfortable myths.Quotation of Bertrand RussellThose who forget good and evil and seek only to know the facts are more likely to achieve good than those who view the world through the distorting medium of their own desires.Quotation of Bertrand RussellThought is subversive and revolutionary, destructive and terrible, Thought is merciless to privilege, established institutions, and comfortable habit. Thought is great and swift and free.Quotation of Bertrand RussellThree passions, simple but overwhelmingly strong, have governed my life: the longing for love, the search for knowledge, and unbearable pity for the suffering of mankind.Quotation of Bertrand RussellTo acquire immunity to eloquence is of the utmost importance to the citizens of a democracy. Quotation of Bertrand RussellTo be without some of the things you want is an indispensable part of happiness.Quotation of Bertrand RussellTo conquer fear is the beginning of wisdom.Quotation of Bertrand RussellTo fear love is to fear life, and those who fear life are already three parts dead.Quotation of Bertrand RussellTo teach how to live without certainty and yet without being paralysed by hesitation is perhaps the chief thing that philosophy, in our age, can do for those who study it.Quotation of Bertrand RussellTo understand a name you must be acquainted with the particular of which it is a name. Quotation of Bertrand RussellWar does not determine who is right - only who is left.Quotation of Bertrand RussellWe are faced with the paradoxical fact that education has become one of the chief obstacles to intelligence and freedom of thought.Quotation of Bertrand RussellWhat is wanted is not the will to believe, but the will to find out, which is the exact opposite. Quotation of Bertrand RussellWhat is wanted is not the will to believe, but the wish to find out, which is its exact opposite. Quotation of Bertrand RussellWhen the intensity of emotional conviction subsides, a man who is in the habit of reasoning will search for logical grounds in favour of the belief which he finds in himself.Quotation of Bertrand RussellWhy is propaganda so much more successful when it stirs up hatred than when it tries to stir up friendly feeling?Quotation of Bertrand RussellWork is of two kinds: first, altering the position of matter at or near the earth's surface relative to other matter; second, telling other people to do so.Quotation of Bertrand Russell。

《The Happy Man》 Bertrand Russell(《幸福的人》伯特兰·罗素)

The happy man正文及翻译:【1】Happiness, as is evident, depends partly upon external /ɪkˈstɜːrnl/ circumstances and partly upon oneself.幸福,正如前已揭示的那样,部分依靠外界环境,部分依靠个人自身。

We have been concerned in this volume with the part which depends upon oneself, and we have been led to the view that so far as this part is concerned the recipe for happiness is a very simple one.在本书内,我们考察了依靠个人自身的那部分,并且得出这样的结论,在与个人自身相关的范围内,幸福的诀窍是十分简单的。

It is thought by many, among whom I think we must include Mr Krutch, whom we considered in an earlier chapter, that happiness is impossible without a creed of a more or less religious kind.许多人——我想前已提及的克罗齐先生也应包括在内——认为,如果没有一种多少带有宗教色彩的信仰,那么幸福是不可能的。

lt is thought by many who are themselves unhappy that their sorrows have complicated and highly intellectualized /ˌɪntəˈlektʃuəla ɪzd/ sources.许多自己并不幸福的人认为,他们的忧伤有着复杂而高度理智化的原因。

高级英语直接听读181:AuthorityandtheIndividual(罗素演讲,敬请转发!)

高级英语直接听读181:AuthorityandtheIndividual(罗素演讲,敬请转发!)本篇选自BBC Reith Lectures,是1948年讲座开篇邀请到的英国哲学家、数学家伯特兰·罗素(Bertrand Russell)就“权威与个体”所做的演讲的第一讲。

全篇长近半小时,为方便朋友利用零星时间收听,我把这篇分成上下两部分,这样文章也不会显得太长。

每周放出上下两篇,这样就是完整的一场讲座,一周能够把这场讲座听好、听透,高级英语学习就有了基本保障。

我在文章中略去五个单词,请放心,都不是很难的词,但与行文紧密相关,请朋友们听一听这五个词各是什么,并回复给本微信订阅号获得积分,每写对一个得一分。

这个积分可以用于未来图书兑换,相关规则我们会尽快出台。

由于微信文章里的录音播放只能停止不能暂停,请准备好纸笔。

如需对应的、播放时可暂停的单独MP3文件,请关注“武太白金星人”微信订阅号(长按本文末二维码图片选择“识别图中的二维码”后即可轻松关注)后把本文转发到您的朋友圈,然后回复“讲座”(引号不要的),即可获得相应的分享链接。

------------------------------------------------REITH LECTURES 1948: Authority and the IndividualBertrand RussellLecture 1: Social Cohesion and Human NatureTRANSMISSION: 24 December 1948 -Home Service------------------------The fundamental problem I propose to consider in these lectures is this: how can we combine that degree of individual initiative which is necessary for progress with the degree of social cohesion that is necessary for survival? I shall begin with theimpulses in human nature that make social co-operation possible.I shall examine first the forms that these impulses took in very primitive communities, and then the adaptations that were brought about by the gradually changing social organisations of advancing civilisation. I shall next consider the extent and intensity of social cohesion in various times and places, leading up to the communities of the present day and the possibilities of further development in the not very distant future. After this discussion of social cohesion I shall take up the other side of the life of man in communities, namely individual initiative, showing the part that it has played in various phases of human evolution, the part that it plays at the present day, and the future possibilities of too much or too little initiative in individuals and groups. I shall then go on to one of the basic problems of our times, namely the conflict which modern technique has introduced between organisation and human nature, or, to 1()the matter in another way, the divorce of the economic motive from the impulses of creation and possession. Having stated this problem, I shall examine what can be done towards its solution, and finally I shall consider as a matter of ethics the whole relation of individual thought and effort and imagination to the authority of the community.In all social animals, including man, co-operation and the unity of a group have some foundation in instinct. This is most complete in ants and bees, which apparently are never tempted to anti-social actions and never deviate from devotion to the nest or the hive. Up to a point we may admire this unswerving devotion to public duty, but it has its drawbacks; ants and bees do not produce great works of art, or make scientific discoveries, or found religions teaching that all ants are sisters. Their sociallife, in fact, is mechanical, precise and static. We are willing that human life shall have an element of turbulence if thereby we can 2() such evolutionary stagnation.Early man was a weak and rare species whose survival at first was precarious. At some period his ancestors came down from the trees and lost the advantage of prehensile toes, but gained the advantage of arms and hands. By these changes they acquired the advantage of no longer having to live in forests, but on the other hand the open spaces into which they spread provided a less abundant nourishment than they had enjoyed in the tropical jungles of Africa. Sir Arthur Keith estimates that primitive man required two square miles of territory per individual to supply him with food, and some other authorities place the amount of territory required even higher. Judging by the anthropoid apes, and by the most primitive communities that have survived into modem times, early man must have lived in small groups not very much larger than families-groups which, at a guess, we may put at, say, between fifty and a hundred individuals. Within each group there seems to have been a considerable amount of co¬operation, but towards all other groups of the same species there was hostility whenever contact occurred. So long as man remained rare, contact with other groups could be occasional, and, at most times, not very important. Each group had its own territory, and conflict would only occur at the frontiers. In those early times marriage appears to have been confined to the group, so that there must have been a very great deal of inbreeding, and varieties, however originating, would tend to be perpetuated. If a group increased in numbers to the point where its existing territory was insufficient, it would be likely to come into conflict with someneighbouring group, and in such conflict any biological advantage which one inbreeding group had acquired over the other might be expected to give it the victory, and therefore to perpetuate its beneficial variation. All this has been very convincingly set forth by Sir Arthur Keith. It is obvious that our early and barely human ancestors cannot have been acting on a thought-out and 3() policy, but must have been prompted by an instinctive mechanism-the dual mechanism of friendship within the tribe and hostility to all others. As the primitive tribe was so small each individual would know intimately each other individual, so that friendly feeling would be co-extensive with acquaintanceship.The Family-Most Compelling of Human GroupsThe strongest and most instinctively compelling of social groups was, and still is, the family. The family is necessitated among human beings by the great length of infancy, and by the fact that the mother of young infants is seriously handicapped in the work of food gathering. It was this circumstance that with human beings, as with most species of birds, made the father an essential member of the family group. This must have led to a division of labour in which the men hunted while the women stayed at home. The transition from the family to the small tribe was presumably biologically connected with the fact that hunting could be more efficient if it was co-operative, and from a very early time the cohesion of the tribe must have been increased and developed by conflicts with other tribes.The remains that have been discovered of early men and half-men are now sufficiently numerous to give a fairly clear picture of the stages in evolution from the most advancedanthropoid apes to the most primitive human beings. The earliest indubitably human remains that have been discovered so far are estimated to belong to a period about one million years ago, but for several million years before that time there seem to have been anthropoids that lived on the ground and not in trees. The most distinctive feature by which the evolutionary status of these early ancestors is fixed is the size of the brain, which increased fairly rapidly until it reached about its present capacity, but has now been virtually stationary for hundreds of thousands of years. During these hundreds of thousands of years man has improved in knowledge, in acquired skill, and in social organisation, but not, so far as can be judged, in congenital intellectual capacity. That purely biological advance, so far as it can be estimated from bones, was completed a long time ago. It is to be supposed accordingly that our congenital mental equipment, as opposed to what we learn, is not so very different from that of paleolithic man. We have still, it would seem, the instincts which led men, before their behaviour had become deliberate, to live in small tribes with a sharp antithesis of internal friendship and external hostility. The changes that have come since those early times have had to 4()for their driving force partly upon this primitive basis of instinct, and partly upon a sometimes barely conscious sense of collective self-interest. One of the things that cause stress and strain in human social life is that it is possible, up to a point, to become aware of rational grounds for a behaviour not prompted by natural instinct. But when such behaviour strains natural instinct too severely nature takes her revenge by producing either listlessness or destructiveness, either of which may cause a structure imposed by reason to break down.Social cohesion, which started with loyalty to a group reinforced by the fear of enemies, grew by processes partly natural and partly deliberate until it reached the vast conglomerations that we now know as nations. T o these processes various forces contributed. At a very early stage loyalty to a group must have been reinforced by loyalty to a leader. In a large tribe the chief or king may be known to everybody even when private individuals are often strangers to each other. In this way, personal as opposed to tribal loyalty makes possible an increase in the size of the group without doing violence to instinct. At a certain stage a further development took place. Wars, which originally were wars of extermination, gradually became-at least in part-wars of conquest; the vanquished, instead of being put to death, were made slaves and compelled to labour for their conquerors. When this happened there came to be two sorts of people within a community, namely the original members who alone were free, and were the repositories of the tribal spirit, and the subjects who obeyed from fear, not from instinctive loyalty. Nineveh and Babylon ruled over vast territories, not because their subjects had any instinctive sense of social cohesion with the dominant city, but solely because of the terror inspired by its prowess in war. From those early days down to modern times war has been the chief 5() in enlarging the size of communities, and fear has increasingly replaced tribal solidarity as a source of social cohesion. This change was not confined to large communities; it occurred, for example, in Sparta, where the free citizens were a small minority, while the Helots were unmercifully suppressed. Sparta was praised throughout antiquity for its admirable social cohesion, but it was a cohesion which never attempted to embrace the whole population, exceptin so far as terror compelled outward loyalty.At a certain stage in the development of civilisation, a new kind of loyalty began to be developed: a loyalty based not on territorial affinity or similarity of race, but on identity of creed. So far as the west is concerned this seems to have originated with the Orphic communities, which admitted slaves on equal terms. Apart from them religion in antiquity was so closely associated with government, that groups of co-religionists were broadly identical with the groups that had grown up on the old biological basis. But identity’ of creed has gradually become a stronger and stronger force. Its military strength was first displayed by Islam in the conquests of the seventh and eighth centuries. It supplied the moving force in the crusades and in the wars of religion. In the sixteenth century theological loyalties very often outweighed those of nationality: English Catholics sided with Spain, French Huguenots with England. In our own day two widespread creeds embrace the loyalty of a very large part of mankind. One of these, the creed of communism, has the advantage of intense fanaticism and embodiment in a sacred book. The other, less definite, is nevertheless potent -it may be called ‘the American way of life’. America, formed by immigration from many different countries, has no biological unity, but it has a unity quite as strong as that of European nations. As Abraham Lincoln said, it is ‘dedicated to a proposition’. Immigrants into America, or at any rate their children, for the most part find the American way of life preferable to that of the Old World, and believe firmly that it would be for the good of mankind if this way of life became universal. Both in America and in Russia unity of creed and national unity have coalesced, and have thereby acquired a newstrength, but these rival creeds have an attraction which transcends their national boundaries.------------------------。

伯特兰 阿瑟 威廉 罗素

英国哲学家、数学家、逻辑学家、历史学家、文学家、 分析哲学的主要创始人

01 人物经历

03 获奖记录 05 人物评价

目录

02 主要贡献 04 个人生活

伯特兰·阿瑟·威廉·罗素(Bertrand Arthur William Russell,1872年5月18日—1970年2月2日),英 国哲学家、数学家、逻辑学家、历史学家、文学家,分析哲学的主要创始人,世界和平运动的倡导者和组织者, 主要作品有《西方哲学史》《哲学问题》《心的分析》《物的分析》等。

婚恋

罗素一生先后七次陷入情,并先后同其中的四位结婚。

人物评价

罗素的哲学具体地体现了诺贝尔先生创立这个奖(诺贝尔文学奖)的初衷,他们对人生的看法是十分近似的, 两个人不但都接受怀疑论,而且都怀有乌托邦理想,并且由于对当前世局的共同忧虑而共同强调人类行为的理性 化。(瑞典文学院评)

罗素在历史上的地位应该说是由于他的哲学著作,特别是他在青年时期和中年时期的早期所完成的著作而赢 得的。(英国哲学家艾耶尔评)

《西方哲学史》绝大多数分析哲学家缺乏历史感,忽视历史问题和历史研究,而罗素却对历史和历史理论终 生嗜之不倦。他写过几十篇历史论文和散布历史专著,这三部是:《自由和组织》《1902-1914年协约国政策》 和《西方哲学史》。其中,《西方哲学史》是一部脍炙人口的哲学史著作,其全名是《西方哲学史及其与从古代 到现代的政治社会情况的》,它在很大程度上力图从历史的角度来观察哲学思想和发展,其引人入胜的原因在于 作者的历史眼光不亚于作者的哲学见解。该书出版后很快成为西方读书界的畅销书,确立了罗素作为一位历史学 家在读者心目中的形象和地位,有许许多多的年轻人,正是被这本书的独特魅力所吸引而走上了哲学道路。

The Legend of the Russell

Politics and Sociology and psychology

• • • • • • • • •

German Social Democracy

A Free Man’s Worship(***) Anti Suffragist Anxieties

War,the off spring of Fear

Justice in War-time Principle of Socialre construction

Political Ideals

Anarchism and Syndicalism Why Men Fight:A Method of A bolishing the International Duel

The Prospect of Industrial Civilization On education,Especially in Early Childhood

Education and the Good life

The Scientific Outlook Education and the Social Order(***)

teaching. Elected member of the Royal Society in 1908. 1950 won

the Nobel Prize in Literature and was awarded the British fine. Russell in philosophy, logic and mathematics, pedagogy, sociology, political science and literature and many other fields have contributed to, although in any field is not a top scholar, but the sum of their knowledge is no one than, its life knowledge more than wisdom, diligence than talent.

Bertrand Russell

Plainness & Simplicity follows the plain style (trend in the 17 & 18) avoid pomp & extravagant words → make his points straightaway especially reflected in his philosophical works e.g. A History of Western Philosophy

• Although he was best known for his contributions to logic and philosophy, Bertrand Russell’s range of interests was impressively wide. He was engaged in what seemed to be the entire extent of human endeavor: mathematics, philosophy, science, and logic, political activism, social justice, education, and sexual morality. • His influence has been so pervasive that in some ways it has become difficult for us to appreciate its full impact.

A comparison

Russell's work & Kahlil Gibran’s on work

Russell's language is more plain, logical and accurate. His viewpoint is more practical and his arguments are full of reasons. Gibran's language is more romantic, lyrical and poetic. It’s not tell much about the practicality of work in daily life.

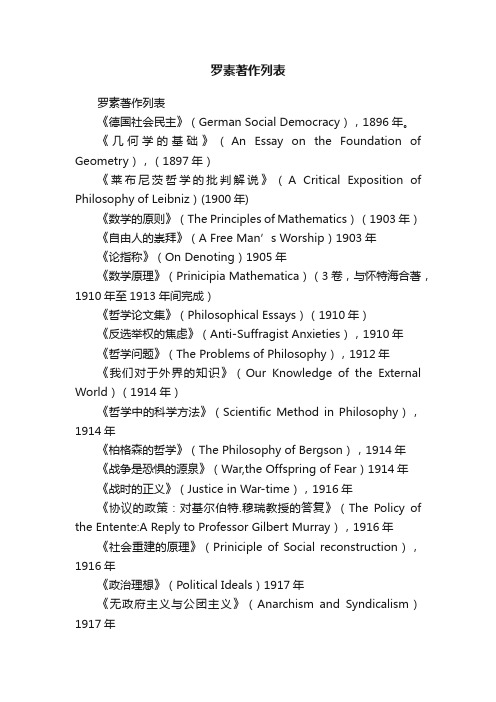

罗素著作列表

罗素著作列表罗素著作列表《德国社会民主》(German Social Democracy),1896年。