Extent and chronology of Quaternary glaciation

西方古物学的英文

西方古物学的英文The Allure of Western AntiquitiesThe study of ancient artifacts and relics from the Western world has long captivated the minds of scholars, historians, and the general public alike. This field, often referred to as Western antiquities, encompasses the examination and preservation of the material remnants of civilizations that once thrived in Europe, the Mediterranean, and the Near East. From the grandeur of ancient Greek temples to the intricate mosaics of the Roman Empire, the wealth of information and cultural insights contained within these artifacts is truly remarkable.One of the primary driving forces behind the fascination with Western antiquities is the desire to uncover and understand the rich tapestry of human history. These ancient objects serve as tangible links to the past, allowing us to glimpse into the lives, beliefs, and achievements of our ancestors. By studying the craftsmanship, symbolism, and context of these artifacts, scholars can shed light on the social, political, and religious structures that shaped the development of Western civilization.The field of Western antiquities is vast and diverse, encompassing a wide range of disciplines, from archaeology and art history to anthropology and linguistics. Archaeologists, for instance, meticulously excavate and analyze the remains of ancient settlements, uncovering invaluable insights into the daily lives and material culture of past societies. Art historians, on the other hand, delve into the symbolism and stylistic evolution of ancient artworks, tracing the artistic traditions that have influenced and shaped Western art over the centuries.The significance of Western antiquities extends far beyond the academic realm, as these artifacts also hold immense cultural and historical value for the modern world. The preservation and display of these ancient treasures in museums and cultural institutions around the globe serve to educate and inspire people of all backgrounds, fostering a deeper appreciation for the shared heritage of humanity.Moreover, the study of Western antiquities has profound implications for our understanding of the present. By examining the past, scholars can uncover the roots of contemporary social, political, and cultural phenomena, shedding light on the complex and often interconnected nature of human civilization. This knowledge can inform and guide our approach to addressing contemporary challenges, as we strive to learn from the successes and failures ofour ancestors.However, the field of Western antiquities is not without its challenges and controversies. One of the most pressing issues is the ongoing debate surrounding the repatriation of cultural artifacts, as many countries and indigenous communities seek to reclaim objects that were acquired through colonial-era looting or unethical practices. This complex issue raises questions about the rightful ownership and stewardship of these ancient treasures, and it has sparked important discussions about the ethical and legal frameworks governing the preservation and display of cultural heritage.Another challenge facing the field of Western antiquities is the need for continued preservation and conservation efforts. The fragile nature of many ancient artifacts, coupled with the threats posed by environmental degradation, conflict, and natural disasters, underscores the importance of developing and implementing effective preservation strategies. Scholars and institutions around the world are constantly working to develop new technologies and techniques to ensure the long-term survival of these irreplaceable cultural assets.Despite these challenges, the study of Western antiquities remains a vibrant and dynamic field, captivating the minds of researchers, students, and the general public alike. As we continue to uncoverand explore the material remnants of our shared past, we gain a deeper understanding of the human experience, the evolution of civilizations, and the enduring legacy of Western culture. Through the preservation and dissemination of this knowledge, we can foster a greater appreciation for the richness and diversity of our global heritage, and inspire future generations to continue the pursuit of understanding our collective past.。

哲学科学全书纲要的英文名

哲学科学全书纲要的英文名## Outlines of the Encyclopedia of Philosophical Sciences.The Outlines of the Encyclopedia of Philosophical Sciences (Grundlinien der Encyklopädie der philosophischen Wissenschaften) is a work by Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, first published in 1817. It is a systematic exposition of Hegel's philosophical system, and it is considered one of the most important works in the history of philosophy.The Outlines is divided into three parts:1. Logic.2. Philosophy of Nature.3. Philosophy of Spirit.Logic is the first part of the Outlines, and it dealswith the most basic concepts of philosophy, such as being, nothingness, and becoming. Hegel argues that these concepts are not static, but rather they are in a constant state of flux and change. He also argues that the laws of logic are not arbitrary, but rather they are based on the nature of reality itself.Philosophy of Nature is the second part of the Outlines, and it deals with the natural world. Hegel argues that nature is not a separate realm from spirit, but rather itis a manifestation of spirit. He also argues that the lawsof nature are not fixed and immutable, but rather they are constantly evolving.Philosophy of Spirit is the third and final part of the Outlines, and it deals with the human spirit. Hegel argues that the human spirit is the highest form of reality, and that it is the goal of all history. He also argues that the human spirit is not a static entity, but rather it is in a constant state of development.The Outlines is a complex and challenging work, but itis also a rewarding one. It is a work that has had a profound influence on the history of philosophy, and it continues to be studied and debated today.## Hegel's Philosophical System.Hegel's philosophical system is based on the idea that reality is a constantly evolving process of becoming. He argues that all things are in a state of flux and change, and that there is no such thing as a static or unchanging reality.Hegel also argues that the laws of logic are not arbitrary, but rather they are based on the nature of reality itself. He believes that the laws of logic are the laws of thought, and that they are therefore the laws of reality.Hegel's philosophical system is often referred to as idealism, because it emphasizes the importance of the mind and spirit. Hegel argues that the mind is the source of all reality, and that the world is a product of the mind.Hegel's idealism is not solipsism, however. He does not believe that the world is simply a product of our own imagination. Rather, he believes that the world is a real and independent entity, but that it is also a product of the mind.Hegel's philosophical system is a complex and challenging one, but it is also a powerful and persuasive one. It is a system that has had a profound influence on the history of philosophy, and it continues to be studied and debated today.## The Outlines in the History of Philosophy.The Outlines was first published in 1817, and it was immediately recognized as a major work of philosophy. It was quickly translated into several languages, and it was soon being studied and debated by philosophers all over the world.The Outlines had a profound influence on thedevelopment of philosophy in the 19th century. It was one of the main sources of inspiration for the idealist movement, and it also helped to shape the development of Marxism.In the 20th century, the Outlines continued to be studied and debated by philosophers. It was a major source of inspiration for the existentialist movement, and it also helped to shape the development of analytic philosophy.The Outlines is still a major work of philosophy today. It is a work that is studied and debated by philosophersall over the world. It is a work that has had a profound influence on the history of philosophy, and it continues to be a source of inspiration for philosophers today.。

当代学术棱镜译丛60本书目

�

[当代学术棱镜译丛]怎样做理论[德]伊瑟尔.pdf

[当代学术棱镜译丛]甜蜜的暴力-悲剧的观念[英]特瑞·伊格尔顿(英文原版).pdf

[当代学术棱镜译丛]白领-美国的中产阶级[美]C·莱特·米尔斯(代替).pdf

[当代学术棱镜译丛]解读大众文化[美]菲斯克.pdf

[当代学术棱镜译丛]胡塞尔《几何学的起源》引论[法]雅克·德里达.pdf

[当代学术棱镜译丛]孤独的人群-美国人性格变动之研究[美]大卫·理斯曼(代替).pdf

[当代学术棱镜译丛]图绘意识形态[斯洛文尼亚]斯拉沃热·齐泽克.pdf

[当代学术棱镜译丛]世界风险社会[德]乌尔里希·贝克(代替).pdf

[当代学术棱镜译丛]解读大众文化[英]菲斯克.pdf

[当代学术棱镜译丛]消费社会[法]让·波德里亚.pdf

[当代学术棱镜译丛]全球化与文化[英]约翰·汤姆林森.pdf【暂缺】

[当代学术棱镜译丛]美学指南[美]彼特·基维.pdf【暂缺】

[当代学术棱镜译丛]文化[英]弗雷德·英格利斯.pdf【暂缺】

[当代学术棱镜译丛]日常生活的革命[法]R·瓦格纳姆.pdf【暂缺】

[当代学术棱镜译丛]晚期马克思主义-阿多诺,或辩证法的韧性[德]西奥多·阿多诺.pdf【暂缺】

[当代学术棱镜译丛]信息批判[英]斯各特·拉什.pdf【暂缺】

[当代学术棱镜译丛]作为实践的文化[英]齐格蒙特·鲍曼.pdf【暂缺】

[当代学术棱镜译丛]后现代转向[美]斯蒂芬·贝斯特 道格拉斯·科尔.pdf【暂缺】

[当代学术棱镜译丛]科学信仰与社会[英]迈克尔·波兰尼.pdf【暂缺】

隐喻研究可以追溯至两千多年前亚里士多德的

隐喻研究可以追溯至两千多年前亚里士多德的《修辞术·亚历山大修辞学·论诗》,随着时代的发展隐喻研究经历了由修辞学研究到认知学研究,人们逐渐认识到隐喻不仅属于语言,而且属于思想、活动和行为,是人类感知、认识客观世界的重要手段。

美国语言学家莱考夫和约翰逊在1980年共同出版了《我们赖以生存的隐喻》,书中将隐喻纳入人的行为活动、思维方式、概念范畴、语言符号等领域进行重新考察和研究,同时提出了概念隐喻的命题,这是隐喻研究史上-个重要的里程碑。

这一命题在不同文化认知系统的研究中也得到了广泛的重视,不仅可以为语言学研究提供新的视角,同时也体现了语言学研究的价值。

普希金(АлександрСергееичПушкин)被誉为“俄罗斯诗歌的太阳”、“俄罗斯文学之父”,他一生短暂却作品丰富,直至生命的最后一息仍旧在认真写作。

他的作品体裁多样,一生创作了800多部诗歌作品,其中爱情和友谊是其最主要的诗歌主题。

我国的普希金研究有着一百多年的历史,从普希金的个人生平到作品,从他的生活到创作都有许多研究成果,普希金研究领域一直在不断拓展,这对于我国俄罗斯文学研究有着深刻的意义。

本文拟将概念隐喻理论运用到普希金关于爱情的诗歌分析研究中。

研究意图并不在于对普希金作品做出前所未有的独到阐释,而是想通过这种研究方法证明概念隐喻理论在俄语及俄罗斯文学研究中的适用性,为概念隐喻理论的普遍适用性提供一点支撑,借以从认知的角度解读俄语文本提供一些依据。

本文通过分析800多首诗歌,以期解决以下问题:总结出普希金诗歌中关于爱情的概念隐喻(如将爱情喻做人、火焰、战争、音乐、液体等),阐释这些概念隐喻形成的原因,同时对爱情概念隐喻表达式进行分析。

(一)国外研究现状从国外研究现状来看,欧美国家是认知语言学的发源地,概念隐喻又是认知语言学主要研究对象之一,所以目前,西方也是研究概念隐喻最为活跃的地方。

美国的芝加哥大学又被称为隐喻研究的集中营。

Archaeologys Search for a Legendary Emperor

Archaeologys Search for a LegendaryEmperorArchaeology has always been a fascinating field of study, as it seeks to uncover the mysteries of our past. One of the most intriguing quests that archaeologists have embarked upon is the search for a legendary emperor. This emperor is said to have ruled over a vast empire, but little is known about him. The search for this emperor has captured the imagination of people for centuries, and has led to numerous expeditions and excavations. In this essay, I will explore the various perspectives on this quest, and the challenges faced by archaeologists in their search for this elusive ruler. From a historical perspective, the search for this legendary emperor is important because it could shed light on an era that has been shrouded in mystery. The emperor is said to have ruled over a vast empire, but there are few records of his reign. His name is not even known for certain,and he is referred to by different names in different cultures. If archaeologists could find evidence of his existence, it could help us understand the political, social, and economic conditions of his time. It could also reveal the extent ofhis empire, and the cultural and religious practices of his people. From acultural perspective, the search for this legendary emperor is important becauseit is a part of our collective history. The stories of his reign have been passed down through generations, and have become a part of our folklore. The emperor is often portrayed as a wise and just ruler, who brought peace and prosperity to his people. His legacy has inspired many works of literature and art, and has become a symbol of power and authority. The search for this emperor is not just about uncovering the truth of our past, but also about preserving our cultural heritage. From a scientific perspective, the search for this legendary emperor is important because it challenges our understanding of history. The lack of records about his reign has led some scholars to doubt his existence. However, the stories about him are too widespread and consistent to be dismissed as mere legend. Ifarchaeologists could find evidence of his existence, it could help us understand how historical facts become distorted over time, and how myths and legends are created. It could also help us develop new techniques for studying the past, andimprove our understanding of human civilization. Despite the importance of this quest, archaeologists face many challenges in their search for the legendary emperor. One of the biggest challenges is the lack of concrete evidence. The stories about the emperor are often vague and contradictory, and there are no written records of his reign. Archaeologists have to rely on oral traditions, legends, and artifacts to piece together the story of his empire. This makes it difficult to separate fact from fiction, and to verify the authenticity of the artifacts. Another challenge is the sheer size of the empire. The emperor is said to have ruled over a vast territory, spanning multiple countries and regions. This makes it difficult to know where to begin the search. Archaeologists have to rely on clues from the stories and legends to narrow down the search area. They also have to deal with political and cultural barriers, as different countries have different laws and regulations regarding archaeological excavations. A third challenge is the danger involved in the search. Some of the areas where the emperor is said to have ruled are remote and inhospitable, with harsh weather conditions and rugged terrain. Archaeologists have to be physically fit and mentally prepared to endure the hardships of the expedition. They also have to deal with the risk of encountering hostile locals, armed conflicts, and natural disasters. Despite these challenges, archaeologists continue to search for the legendary emperor. They use a variety of techniques, including remote sensing, ground-penetrating radar, and satellite imagery. They also collaborate with local communities and governments to gain access to the search areas. Some of the recent discoveries, such as the tomb of the First Emperor of China, have given hope to archaeologists that the legendary emperor may one day be found. In conclusion, the search for the legendary emperor is a fascinating and important quest that has captured the imagination of people for centuries. From a historical, cultural, and scientific perspective, it has the potential to reveal important insights into our past and our understanding of human civilization. However, archaeologists face many challenges in their search, including the lack of concrete evidence, the vastness of the empire, and the danger involved in the expedition. Despite these challenges, they continue to search for the emperor, driven by their passion for uncovering the mysteries of our past.。

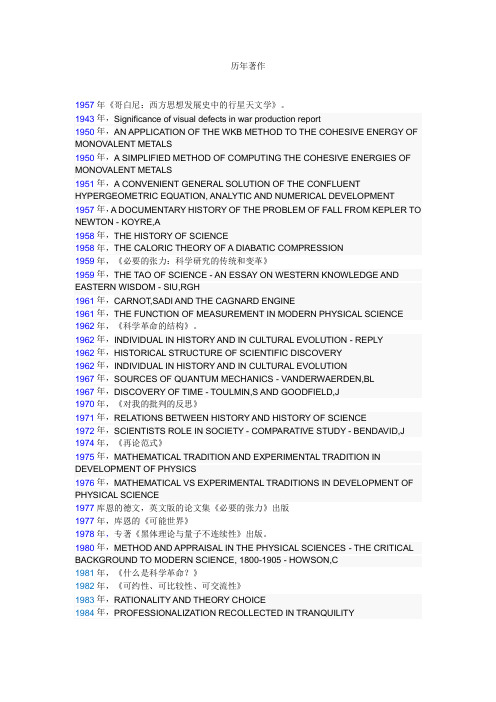

托马斯库恩历年著作

历年著作1957年《哥白尼:西方思想发展史中的行星天文学》。

1943年,Significance of visual defects in war production report1950年,AN APPLICATION OF THE WKB METHOD TO THE COHESIVE ENERGY OF MONOVALENT METALS1950年,A SIMPLIFIED METHOD OF COMPUTING THE COHESIVE ENERGIES OF MONOVALENT METALS1951年,A CONVENIENT GENERAL SOLUTION OF THE CONFLUENT HYPERGEOMETRIC EQUATION, ANALYTIC AND NUMERICAL DEVELOPMENT1957年,A DOCUMENTARY HISTORY OF THE PROBLEM OF FALL FROM KEPLER TO NEWTON - KOYRE,A1958年,THE HISTORY OF SCIENCE1958年,THE CALORIC THEORY OF A DIABATIC COMPRESSION1959年,《必要的张力:科学研究的传统和变革》1959年,THE TAO OF SCIENCE - AN ESSAY ON WESTERN KNOWLEDGE AND EASTERN WISDOM - SIU,RGH1961年,CARNOT,SADI AND THE CAGNARD ENGINE1961年,THE FUNCTION OF MEASUREMENT IN MODERN PHYSICAL SCIENCE 1962年,《科学革命的结构》。

1962年,INDIVIDUAL IN HISTORY AND IN CULTURAL EVOLUTION - REPLY1962年,HISTORICAL STRUCTURE OF SCIENTIFIC DISCOVERY1962年,INDIVIDUAL IN HISTORY AND IN CULTURAL EVOLUTION1967年,SOURCES OF QUANTUM MECHANICS - VANDERWAERDEN,BL1967年,DISCOVERY OF TIME - TOULMIN,S AND GOODFIELD,J1970年,《对我的批判的反思》1971年,RELATIONS BETWEEN HISTORY AND HISTORY OF SCIENCE1972年,SCIENTISTS ROLE IN SOCIETY - COMPARATIVE STUDY - BENDAVID,J 1974年,《再论范式》1975年,MATHEMATICAL TRADITION AND EXPERIMENTAL TRADITION IN DEVELOPMENT OF PHYSICS1976年,MATHEMATICAL VS EXPERIMENTAL TRADITIONS IN DEVELOPMENT OF PHYSICAL SCIENCE1977库恩的德文,英文版的论文集《必要的张力》出版1977年,库恩的《可能世界》1978年,专著《黑体理论与量子不连续性》出版。

22270838

( ]桑 巴特 .奢侈 与资本 主义 ( .王燕平等译 .上海人 民出版社 , 00 3. 9 M] 20 .22

[0 1 ]伊 ・ 拉卡托斯.科学研究纲领方法论 [ .兰征译 .上海译文 出版社 ,18 .3 M] 96 . [1 1 ]约翰 ・ 科廷汉.理性主义 [ .江恰译.沈 阳:辽宁教育 出版社 ,19 .5 M] 98 . [2 [4 [6 1 ] 1 ] 1 ]M ・ 克莱因.数学 :确定性 的丧失 [ .李宏魁译.长沙 :湖南科学技术 出版社 ,19 .2 ,3 0 M] 9 7 2 ,5 [7 1 ]托马斯 ・ 库恩 .科学革命 的结构 [ .金吾伦等译.北京大学 出版社 ,20 .11 M] 04 0 . [8 [0 1 ] 2 ]怀特海.科学与近代世界 ( .何钦译.商务印书馆 ,1 5 .2 , 0 M] 99 1 2 . [ 9 马尔 库塞 .单 向度 的人 [ .张峰等译 .重庆 出版社 ,2 0 .14 1] M] 01 2 . 【1 2 ]张奠基 .二十世纪数学史话 【 .北京 :知识 出版社 ,18 .17 M] 94 2 . [ 2 M ・ 莱因.古 今数学思想史 ( 1 ) [ .张理京等译.上海科学技术出版社 ,17 .2 1 2] 克 第 册 M] 99 5 . [3 2 ]文德尔班.哲学史教程 ( 下册) [ .罗达仁译.商务 印书馆 ,19 .33—34 M] 93 5 5. [4 2 ]霍克海默 ,阿道尔诺.启蒙辩证 法 [ .洪 佩郁等译 .重庆 出版社 ,19 .5 M] 90 .

(4 ・ c・ 31 S F・ 密尔松.普通法的历史基础 ( .李显冬等译 .中国大百科全书出版社 ,19.7 . M] 99 2

[5 3 ]罗杰 ・ 科特威尔.法律社会学导论 [ .潘大松等译 .北京 :华夏 出版社 ,18 .17 M] 99 7.

介绍别人的作文英语

介绍别人的作文英语In the realm of English composition, introducing someoneelse's work can be a delicate task that requires a blend of respect, accuracy, and clarity. Here is a structured approach to introduce someone else's essay in English:Author: [Author's Name]Introduction:The first step in introducing an essay is to provide a brief overview of the author's background. Mention the author's qualifications, field of expertise, and any notable achievements that lend credibility to their work.Purpose:Explain the purpose of the essay. Is it to persuade, inform, or entertain? Understanding the author's intent can help the reader approach the material with the right mindset.Main Themes:Highlight the central themes or arguments presented in the essay. Summarize these points concisely, ensuring not to giveaway the entire content but to pique the reader's interest.Structure:Give a brief outline of the essay's structure. How is the information organized? Is it chronological, thematic, or argumentative? This helps the reader anticipate the flow of ideas.Style and Tone:Describe the author's writing style and tone. Is it formal or conversational? Persuasive or analytical? This can provide insight into the author's approach and the intended audience.Significance:Discuss why the essay is significant. What contribution does it make to its field or to the broader discourse? This can help the reader understand the essay's relevance and importance.Conclusion:End the introduction by summarizing the key points and encouraging the reader to delve into the essay. You might also mention any particular aspects of the essay that you found particularly insightful or thought-provoking.Citation:Finally, ensure that you properly cite the essay, providing the full reference details so that interested readers can locate and read the original work themselves.When introducing someone else's essay, it's important to be respectful of their work and to present it in a way that does justice to their ideas and efforts. This approach ensuresthat the reader is well-prepared to engage with the essay and appreciates the author's contributions.。

海德格尔 科学与沉思 英文书名

海德格尔科学与沉思英文书名The Science and Meditation of Heidegger.In the vast landscape of philosophy, Martin Heidegger's thought stands as a unique and profound monument, shaping our understanding of the relationship between science, knowledge, and the fundamental questions of existence. His work, though dense and often challenging, offers profound insights into the nature of scientific inquiry and the philosophical meditations that underlie it.The intersection of science and philosophy has always been a fertile ground for intellectual exploration. Science, as a systematic pursuit of knowledge through observation, experimentation, and theory-building, aims to uncover the regularities and patterns that govern our world. Philosophy, on the other hand, seeks to understand the fundamental nature of reality, knowledge, values, and existence. Heidegger's approach to this intersection is bothdistinctive and profound.At the heart of Heidegger's philosophy lies the concept of "being." He argues that the fundamental question of philosophy is not "what is there?" but rather "how does something come to be?" This question of being, Heidegger maintains, is prior to and more fundamental than any scientific inquiry into the specific entities or phenomena that populate our world. Science, in Heidegger's view, operates within a framework of pre-existing categories and assumptions that shape the way we perceive and understand the world.Heidegger's critique of science is not a rejection of its.。

《作为意志和表象的世界》外文文献资料+中文翻译

外文文献17In the first book we considered the idea merely as such, that is, only according to its general form. It is true that as far as the abstract idea, the concept, is concerned, we obtained a knowledge of it in respect of its content also, because it has content and meaning only in relation to the idea of perception, with out which it would be worthless and empty. Accordingly, directing our attention exclusively to the idea of perception, we shall now endeavour to arrive at a knowledge of its content, its more exact definition, and the forms which it presents to us. And it will specially interest us to find an explanation of its peculiar significance, that significance which is otherwise merely felt, but on account of which it is that these pictures do not pass by us entirely strange and meaningless, as they must other wise do, but speak to us directly, are understood, and obtain an interest which concerns our whole nature.We direct our attention to mathematics, natural science, and philosophy, for each of these holds out the hope that it will afford us a part of the explanation we desire. Now, taking philosophy first, we find that it is like a monster with many heads, each of which speaks a different language. They are not, indeed, all at variance on the point we are here considering, the significance of the idea of perception. For, with the exception of the Sceptics and the Idealists, the others, for the most part, speak very much in the same way of an object which constitutes the basis of the idea, and which is indeed different in its whole being and nature from the idea, but yet isin all points as like it as one egg is to another. But this does not help us, for we are quite unable to distinguish such an object from the idea; we find that they are one and the same; for every object always and for ever presupposes a subject, and therefore remains idea, so that we recognised objectivity as belonging to the most universal form of the idea, which is the division into subject and object. Further, the principle of sufficient reason, which is referred to in support of this doctrine, is for us merely the form of the idea, the orderly combination of one idea with another, but not the combination of the whole finite or infinite series of ideas with something which is not idea at all, and which cannot therefore be presented in perception. Of the Sceptics and Idealists we spoke above, in examining the controversy about thereality of the outer world.If we turn to mathematics to look for the fuller knowledge we desire of the idea of perception, which we have, as yet, only understood generally, merely in its form, we find that mathematics only treats of these ideas so far as they fill time and space, that is, so far as they are quantities. It will tell us with the greatest accuracy thehow-many and the how-much; but as this is always merely relative, that is to say, merely a comparison of one idea with others, and a comparison only in the one respect of quantity, this also is not the information we are principally in search of.Lastly, if we turn to the wide province of natural science, which is divided into many fields, we may, in the first place, make a general division of it into two parts. It is either the description of forms, which I call Morphology, or the explanation of changes, which I call Etiology. The first treats of the permanent forms, the second of the changing matter, according to the laws of its transition from one form to another. The first is the whole extent of what is generally called natural history. It teaches us, especially in the sciences of botany and zoology, the various permanent, organised, and therefore definitely determined forms in the constant change of individuals; and these forms constitute a great part of the content of the idea of perception. In natural history they are classified, separated, united, arranged according to natural and artificial systems, and brought under concepts which make a general view and knowledge of the whole of them possible. Further, an infinitely fine analogy both in the whole and in the parts of these forms, and running through them all (unité de plan), is established, and thus they may be com pared to innumerable variations on a theme which is not given. The passage of matter into these forms, that is to say, the origin of individuals, is not a special part of natural science, for every individual springs from its like by generation, which is everywhere equally mysterious, and has as yet evaded definite knowledge. The little that is known on the subject finds its place in physiology, which belongs to that part of natural science I have called etiology. Mineralogy also, especially where it becomes geology, inclines towards etiology, though it principally belongs to morphology. Etiology proper comprehends all those branches of natural science in which the chief concern is the knowledge of cause and effect. The sciences teach how, according to an invariable rule, onecondition of matter is necessarily followed by a certain other condition; how one change necessarily conditions and brings about a certain other change; this sort of teaching is called explanation. The principal sciences in this department are mechanics, physics, chemistry, and physiology.If, however, we surrender ourselves to its teaching, we soon become convinced that etiology cannot afford us the information we chiefly desire, any more than morphology. The latter presents to us innumerable and in finitely varied forms, which are yet related by an unmistakable family likeness. These are for us ideas, and when only treated in this way, they remain always strange to us, and stand before us like hieroglyphics which we do not understand. Etiology, on the other hand, teaches us that, according to the law of cause and effect, this particular condition of matter brings about that other particular condition, and thus it has explained it and performed its part. However, it really does nothing more than indicate the orderly arrangement according to which the states of matter appear in space and time, and teach in all cases what phenomenon must necessarily appear at a particular time in a particular place. It thus determines the position of phenomena in time and space, according to a law whose special content is derived from experience, but whose universal form and necessity is yet known to us independently of experience. But it affords us absolutely no information about the inner nature of any one of these phenomena: this is called a force of nature, and it lies outside the province of causal explanation, which calls the constant uniformity with which manifestations of such a force appear whenever their known conditions are present, a law of nature. But this law of nature, these conditions, and this appearance in a particular place at a particular time, are all that it knows or ever can know. The force itself which manifests itself, the inner nature of the phenomena which appear in accordance with these laws, remains always a secret to it, something entirely strange and unknown in the case of the simplest as well as of the most complex phenomena. For although as yet etiology has most completely achieved its aim in mechanics, and least completely in physiology, still the force on account of which a stone falls to the ground or one body repels another is, in its inner nature, not less strange and mysterious than that which produces the movements and the growth of an animal. The science ofmechanics presupposes matter, weight, impenetrability, the possibility of communicating motion by impact, inertia and so forth as ultimate facts, calls them forces of nature, and their necessary and orderly appearance under certain conditions a law of nature. Only after this does its explanation begin, and it consists in indicating truly and with mathematical exactness, how, where and when each force manifests itself, and in referring every phenomenon which presents itself to the operation of one of these forces. Physics, chemistry, and physiology proceed in the same way in their province, only they presuppose more and accomplish less. Consequently the most complete etiological explanation of the whole of nature can never be more than an enumeration of forces which cannot be explained, and a reliable statement of the rule according to which phenomena appear in time and space, succeed, and make way for each other. But the inner nature of the forces which thus appear remains unexplained by such an explanation, which must confine itself to phenomena and their arrangement, because the law which it follows does not extend further. In this respect it may be compared to a section of a piece of marble which shows many veins beside each other, but does not allow us to trace the course of the veins from the interior of the marble to its surface. Or, if I may use an absurd but more striking comparison, the philosophical investigator must always have the same feeling towards the complete etiology of the whole of nature, as a man who, without knowing how, has been brought into a company quite unknown to him, each member of which in turn presents another to him as his friend and cousin, and therefore as quite well known, and yet the man himself, while at each introduction he expresses himself gratified, has always the question on his lips: "But how the deuce do I stand to the whole company?"Thus we see that, with regard to those phenomena which we know only as our ideas, etiology can never give us the desired information that shall carry us beyond this point. For, after all its explanations, they still remain quite strange to us, as mere ideas whose significance we do not understand. The causal connection merely gives us the rule and the relative order of their appearance in space and time, but affords us no further knowledge of that which so appears. Moreover, the law of causality itself has only validity for ideas, for objects of a definite class, and it has meaningonly in so far as it presupposes them. Thus, like these objects themselves, it always exists only in relation to a subject, that is, conditionally; and so it is known just as well if we start from the subject, i.e., a priori, as if we start from the object, i.e., a posteriori. Kant indeed has taught us this.But what now impels us to inquiry is just that we are not satisfied with knowing that we have ideas, that they are such and such, and that they are connected according to certain laws, the general expression of which is the principle of sufficient reason. We wish to know the significance of these ideas; we ask whether this world is merely idea; in which case it would pass by us like an empty dream or a baseless vision, not worth our notice; or whether it is also something else, something more than idea, and if so, what. Thus much is certain, that this something we seekfor must be completely and in its whole nature different from the idea; that the forms and laws of the idea must therefore be completely foreign to it; further, that we cannot arrive at it from the idea under the guidance of the laws which merely combine objects, ideas, among themselves, and which are the forms of the principle of sufficient reason.Thus we see already that we can never arrive at the real nature of things from without. However much we investigate, we can never reach anything but images and names. We are like a man who goes round a castle seeking in vain for an entrance, and sometimes sketching the façades. And yet this is the method that has been followed by all philosophers before me.18In fact, the meaning for which we seek of that world which is present to us only as our idea, or the transition from the world as mere idea of the knowing subject to whatever it may be besides this, would never be found if the investigator himself were nothing more than the pure knowing subject (a winged cherub without a body). But he is himself rooted in that world; he finds himself in it as an individual, that is to say, his knowledge, which is the necessary supporter of the whole world as idea, is yet always given through the medium of a body, whose affections are, as we have shown, the starting-point for the understanding in the perception of that world. His body is, for the pure knowing subject, an idea like every other idea, an object amongobjects. Its movements and actions are so far known to him in precisely the same way as the changes of all other perceived objects, and would be just as strange and incomprehensible to him if their meaning were not explained for him in an entirely different way. Otherwise he would see his actions follow upon given motives with the constancy of a law of nature, just as the changes of other objects follow upon causes, stimuli, or motives. But he would not understand the influence of the motives any more than the connection between every other effect which he sees and its cause. He would then call the inner nature of these manifestations and actions of his body which he did not understand a force, a quality, or a character, as he pleased, but he would have no further insight into it. But all this is not the case; indeed, the answer to the riddle is given to the subject of knowledge who appears as an individual, and the answer is will. This and this alone gives him the key to his own existence, reveals to him the significance, shows him the inner mechanism of his being, of his action, of his movements. The body is given in two entirely different ways to the subject of knowledge, who becomes an individual only through his identity with it. It is given as an idea in intelligent perception, as an object among objects and subject to the laws of objects. And it is also given in quite a different way as that which is immediately known to every one, and is signified by the word will. Every true act of his will is also at once and without exception a movement of his body. The act of will and the movement of the body are not two different things objectively known, which the bond of causality unites; they do not stand in the relation of cause and effect; they are one and the same, but they are given in entirely different ways, — immediately, and again in perception for the understanding. The action of the body is nothing but the act of the will objectified, i.e., passed into perception. It will appear later that this is true of every movement of the body, not merely those which follow upon motives, but also involuntary movements which follow upon mere stimuli, and, indeed, that the whole body is nothing but objectified will, i.e., will become idea. All this will be proved and made quite clear in the course of this work. In one respect, therefore, I shall call the body the objectivity of will; as in the previous book, and in the essay on the principle of sufficient reason, in accordance with the one-sided point of view intentionallyadopted there (that of the idea), I called it the immediate object. Thus in a certain sense we may also say that will is the knowledge a priori of the body, and the body is the knowledge a posteriori of the will. Resolutions of the will which relate to the future are merely deliberations of the reason about what we shall will at a particular time, not real acts of will. Only the carrying out of the resolve stamps it as will, for till then it is never more than an intention that may be changed, and that exists only in the reason in abstracto. It is only in reflection that to will and to act are different; in reality they are one. Every true, genuine, immediate act of will is also, at once and immediately, a visible act of the body. And, corresponding to this, every impression upon the body is also, on the other hand, at once and immediately an impression upon the will. As such it is called pain when it is opposed to the will; gratification or pleasure when it is in accordance with it. The degrees of both are widely different. It is quite wrong, however, to call pain and pleasure ideas, for they are by no means ideas, but immediate affections of the will in its manifestation, the body; compulsory, instantaneous willing or not-willing of the impression which the body sustains. There are only a few impressions of the body, which do not touch the will, and it is through these alone that the body is an immediate object of knowledge, for, as perceived by the understanding, it is already an indirect object like all others. These impressions are, therefore, to be treated directly as mere ideas, and excepted from what has been said. The impressions we refer to are the affections of the purely objective senses of sight, hearing, and touch, though only so far as these organs are affected in the way which is specially peculiar to their specific nature. This affection of them is so excessively weak an excitement of the heightened and specifically modified sensibility of these parts that it does not affect the will, but only furnishes the understanding with the data out of which the perception arises, undisturbed by any excitement of the will. But every stronger or different kind of affection of these organs of sense is painful, that is to say, against the will, and thus they also belong to its objectivity. Weakness of the nerves shows itself in this, that the impressions which have only such a degree of strength as would usually be sufficient to make them data for the understanding reach the higher degree at which they influence the will, that is to say, give pain or pleasure, though more often pain, which is, however,to some extent deadened and inarticulate, so that not only particular tones and strong light are painful to us, but there ensues a generally unhealthy and hypochondriacal disposition which is not distinctly understood. The identity of the bodv and the will shows itself further, among other ways, in the circumstance that every vehement and excessive movement of the will, i.e., every emotion, agitates the body and its inner constitution directly, and disturbs the course of its vital functions. This is shown in detail in “Will in Nature” p. 27 of the second edition and p.28 of the third.外文文献翻译17在第一篇里我们只是把表象作为表象,从而也只是在普遍的形式上加以考察。

《文学地理学学术史》一书的英文

《文学地理学学术史》一书的英文Title: Academic History of Literary Geography.Introduction.The academic history of literary geography is an intriguing and complex narrative that charts the evolution of how literature and geographical concepts have intersected over time. This interdisciplinary field explores the spatial dimensions of literary works, analyzing how writers represent place, space, and environment in their narratives. The study of literary geography offers insights into the cultural, historical, and social contexts that shape literary representations of the world.Early Developments.The earliest origins of literary geography can be traced to ancient Greek and Roman scholars who wereinterested in the geographical settings of literary works. These scholars often annotated classical texts with geographical information, providing readers with a spatial framework for understanding the narratives. However, it was during the Renaissance period that the field began to emerge more systematically. Humanists of this era were interested in the connections between literature, history, and geography, and they began to compile bibliographies and maps that integrated these different disciplines.Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries.The eighteenth and nineteenth centuries saw a significant growth in the field of literary geography. The Enlightenment period brought about a renewed interest in the natural world and the sciences, and this led to a greater focus on the geographical settings of literary works. Writers such as Samuel Taylor Coleridge and William Wordsworth were particularly interested in exploring the natural landscapes of England in their poetry. In addition, the development of the romantic movement further emphasized the importance of place and space in literaryrepresentations.During this period, the field of literary geographyalso began to take shape in academic institutions. Universities such as Oxford and Cambridge establishedchairs in literary geography, and scholars began to publish specialized journals and monographs dedicated to the studyof literary representations of place.Twentieth Century and Beyond.The twentieth century marked a period of significant transformation for the field of literary geography. The advent of new technologies and theories, such as GIS (Geographic Information Systems) and cultural geography, provided scholars with new tools and perspectives for analyzing literary representations of space. This led to a proliferation of new research and publications in the field, as well as an increased interest in the connections between literature and environmentalism.In recent years, literary geography has continued toevolve and expand. Scholars have begun to explore the global dimensions of literary representations, analyzing works from diverse cultural and geographical backgrounds. In addition, the field has also been influenced by the rise of digital humanities, which has allowed scholars to engage with literary texts in new and innovative ways.Conclusion.The academic history of literary geography is a rich and diverse tapestry that spans centuries and encompasses a wide range of theoretical and methodological approaches. As the field continues to evolve, it offers new insights into the connections between literature, culture, and the natural world. By examining the spatial dimensions of literary works, we can gain a deeper understanding of the ways that place, space, and environment shape our literary experiences.(Note: This is a condensed overview of the academic history of literary geography, and there are many moredetailed aspects and individual contributions that could be discussed in a full-length article.)。

《2024年翻译规范理论视角下海外汉学史学著作《乾隆帝》译本研究》范文

《翻译规范理论视角下海外汉学史学著作《乾隆帝》译本研究》篇一翻译规范理论视角下《乾隆帝》译本研究一、引言在全球化与文化交流的今天,海外汉学史学著作的翻译与研究显得尤为重要。

其中,关于中国历史人物的译本,如《乾隆帝》,不仅是对外传播中华文化的重要载体,也是跨文化交流的桥梁。

本文以翻译规范理论为视角,对《乾隆帝》的译本进行深入研究,旨在探讨其翻译策略与技巧,以及其如何在外语文化背景下实现文化价值的传播。

二、翻译规范理论概述翻译规范理论是指在进行翻译活动时所遵循的一套规范和原则。

这些规范涉及到语言层面的转换、文化层面的传播以及译本接受度的考量。

在跨文化交际中,翻译不仅仅是语言的转换,更是文化的传递与交流。

因此,翻译规范理论强调译者在翻译过程中应遵循的原语文化与译语文化的平衡,以及在跨文化交流中实现有效沟通的策略。

三、《乾隆帝》译本分析1. 语言层面:在《乾隆帝》的译本中,译者采用了何种翻译策略和技巧进行语言的转换?是否充分考虑了汉语与外语的语言特点与表达习惯?这些策略和技巧如何影响了译本的流畅性与可读性?2. 文化层面:《乾隆帝》作为一部历史著作,其内容涉及大量的中国历史文化背景。

译者在翻译过程中如何处理文化元素的传达?如何在外语文化中重现原作的文化内涵?这些问题的解决方式不仅体现了译者的翻译规范,也直接影响着译本的文化传播效果。

四、《乾隆帝》译本的翻译策略与技巧1. 直译与意译:《乾隆帝》的译本中,译者如何在直译与意译之间寻找平衡?对于一些具有特定文化背景的词汇或表达,是否进行了详细的注解或背景介绍?这些做法如何帮助读者更好地理解原文的文化内涵?2. 文化元素的传达:对于中国特有的文化元素,如中国历史人物、典故、习俗等,译者采取了何种策略进行翻译?这些策略如何确保了文化信息的准确传达?五、《乾隆帝》译本的影响与启示1. 文化传播:《乾隆帝》的译本在外语文化中如何传播了中国传统文化?对于推动中国文化“走出去”战略有何重要意义?2. 翻译启示:通过对《乾隆帝》译本的研究,我们可以得到哪些关于翻译的启示?如何在跨文化交际中更好地实现语言的转换与文化的传播?六、结论《乾隆帝》的译本研究,不仅是对一部具体著作的探讨,更是对翻译规范理论在实践中的应用研究。

chronological age阅读理解

chronological age阅读理解Essentially, everyone has two ages: a chronological(按时间计算的)age, how old the calendar says you are, and a biological age, basically the age at which your body functions as it compares to average fitness or health levels."Chronological age isn't how old we really are. It's merely a number," said Professor David Sinclair at Harvard University. "It is biological age that determines our health and ultimately our lifespan. We all age biologically at different rates according to our genes, what we eat, how much we exercise, and what environment we live in. Biological age is the number of candles we really should be blowing out. In the future, with advances in our ability to control biological age, we may have even fewer candles on our birthday cake than the previous one."To calculate biological age, Professor Levine at ale University identified nine biomarker(生物标志)that seemed to be the most influential on lifespan by a simple blood test. The numbers of those markers, such as blood sugar and immune(免疫的)measures, can be put into the computer, and the algorithm(算式;算法)does the rest.Perhaps what's most important here is that these measures can be changed. Doctors can take this information and helppatients make changes to lifestyle, and hopefully take steps to improve their biological conditions. "I think the most exciting thing about this research is that these things aren't set in stone," Levine said. "People can be given the information earlier and take steps to improve their health before it's too late."Levine even entered her own numbers into the algorithm. She was surprised by the results. "I always considered myself a very healthy person. I'm physically active; I eat what I consider a fairly healthy diet. But I did not find my results to be as good as I had hoped they would be. It was a wake-up call," she said.Levine is working with a group to provide access to the algorithm online so that anyone can calculate their biological age, identify potential risks and take steps to improve their own health in the long run. "No one wants to live an extremely long life with a lot of chronic(慢性的)diseases," Levine said. "By delaying the development of mental and physical functioning problems, people can still be engaged in society in their senior years. That is the ideal we should be pursuing."(1)Biological age depends on _______.A .whether we can adapt ourselves to the environmentB .how well our body works compared with our peers'C .when we start to take outdoor exerciseD .what the calendar says about our age(2)By saying "we may have even fewer candles on our birthday cake than the previous one" in Para. 2, the author means _______.A .we don't have to celebrate our birthday every yearB .we are chronologically older than last yearC .we might be less happy than the previous yearD .we may be biologically younger than the year before(3)What does the author want to tell us by Levine's example in Para. 5?A .It is necessary to change our diet regularly.B .The test results may give us wrong information.C .Waking up early in the morning is good for our fitness.D .The algorithm can reveal our potential health problems.(4)The eventual goal of Levine's research is to ______.A .free people from chronic diseasesB .work out a solution to genetic problemsC .keep people socially active even in old ageD .provide people with access to scientific theory。

时空顺序法英语作文128字

时空顺序法英语作文128字英文回答:Chronological order is a writing style that presents events in the order in which they happened, from beginning to end. It is a commonly used and straightforward approach to storytelling, especially when recounting past events or experiences.Chronological order can be employed in various forms of writing, including essays, articles, memoirs, andhistorical accounts. It helps create a logical and coherent narrative, making it easier for readers to follow the progression of events. Additionally, this writing style allows the author to provide context and background information necessary for understanding the events being described.中文回答:时空顺序法是一种写作结构,它按照事件发生的时间顺序逐一展开情节。

它是一种常用的、直接的叙事手法,尤其适用于讲述过去的事件或经历。

时空顺序法可用于各种形式的写作中,包括散文、文章、回忆录和历史记录。

它有助于形成一个合乎逻辑、连贯的叙述,便于读者了解事件的进展。

此外,这种写作风格允许作者提供背景信息和语境,为理解所描述的事件做好铺垫。

2009高考英语阅读理解精读(2)methodofscientificinquiry

2009高考英语阅读理解精读(2):MethodofScientificInquiryWhytheinductiveandmathematicalsciences,aftertheirfirstrapiddevelo pmentattheculminationofGreekcivilization,advancedsoslowlyfortwothousa ndyears—andwhyinthefollowingtwohundredyearsaknowledgeofnaturalandmat hematicalsciencehasaccumulated,whichsovastlyexceedsallthatwasprevious lyknownthatthesesciencesmaybejustlyregardedastheproductsofourowntimes —arequestionswhichhaveinterestedthemodernphilosophernotlessthantheob jectswithwhichthesesciencesaremoreimmediatelyconversant.Wasittheemplo ymentofanewmethodofresearch,orintheexerciseofgreatervirtueintheuseoft heoldmethods,thatthissingularmodernphenomenonhaditsorigin?Wasthelongp eriodoneofarresteddevelopment,andisthemoderneraoneofnormalgrowth?Orsh ouldweascribethecharacteristicsofbothperiodstoso-calledhistoricalacci dents—totheinfluenceofconjunctionsincircumstancesofwhichnoexplanatio nispossible,saveintheomnipotenceandwisdomofaguidingProvidence?Theexplanationwhichhasbecomecommonplace,thattheancientsemployedde ductionchieflyintheirscientificinquiries,whilethemodernsemployinducti on,provestobetoonarrow,andfailsuponcloseexaminationtopointwithsuffici entdistinctnessthecontrastthatisevidentbetweenancientandmodernscienti ficdoctrinesandinquiries.Forallknowledgeisfoundedonobservation,andpro ceedsfromthisbyanalysis,bysynthesisandanalysis,byinductionanddeductio n,andifpossiblebyverification,orbynewappealstoobservationundertheguid anceofdeduction—bystepswhichareindeedcorrelativepartsofonemethod;and theancientsciencesaffordexamplesofeveryoneofthesemethods,orpartsofone method,whichhavebeengeneralizedfromtheexamplesofscience.Afailuretoemployortoemployadequatelyanyoneofthesepartialmethods,a nimperfectionintheartsandresourcesofobservationandexperiment,careless nessinobservation,neglectofrelevantfacts,byappealtoexperimentandobser vation—thesearethefaultswhichcauseallfailurestoascertaintruth,whethe ramongtheancientsorthemoderns;butthisstatementdoesnotexplainwhythemod ernispossessedofagreatervirtue,andbywhatmeansheattainedhissuperiority .Muchlessdoesitexplainthesuddengrowthofscienceinrecenttimes.Theattempttodiscovertheexplanationofthisphenomenonintheantithesis of“facts”and“theories”or“facts”and“ideas”—intheneglectamongt heancientsoftheformer,andtheirtooexclusiveattentiontothelatter—prove salsotobetoonarrow,aswellasopentothechargeofvagueness.Forinthefirstpl ace,theantithesisisnotcomplete.Factsandtheoriesarenotcoordinatespecies.Theories,iftrue,arefacts—aparticularclassoffactsindeed,generallyco mplex,andifalogicalconnectionsubsistsbetweentheirconstituents,haveall thepositiveattributesoftheories.Nevertheless,thisdistinction,howeverinadequateitmaybetoexplainthe sourceoftruemethodinscience,iswellfounded,andconnotesanimportantchara cterintruemethod.Afactisapropositionofsimple.Atheory,ontheotherhand,i ftruehasallthecharacteristicsofafact,exceptthatitsverificationispossi bleonlybyindirect,remote,anddifficultmeans.Toconverttheoriesintofacts istoaddsimpleverification,andthetheorythusacquiresthefullcharacterist icsofafact.1.Thetitlethatbestexpressestheideasofthispassageis[A].Philosophyofmathematics.[B].TheRecentGrowthinScience.[C].TheVerificationofFacts.[C].MethodsofScientificInquiry.2.Accordingtotheauthor,onepossiblereasonforthegrowthofscienceduringthedaysoftheancientGreeksandinmoderntimesis[A].thesimilaritybetweenthetwoperiods.[B].thatitwasanactofGod.[C].thatbothtriedtodeveloptheinductivemethod.[D].duetothedeclineofthedeductivemethod.3.Thedifferencebetween“fact”and“theory”[A].isthatthelatterneedsconfirmation.[B].restsonthesimplicityoftheformer.[C].isthedifferencebetweenthemodernscientistsandtheancientGreeks.[D].helpsustounderstandthedeductivemethod.4.Accordingtotheauthor,mathematicsis[A].aninductivescience.[B].inneedofsimpleverification.[C].adeductivescience.[D].basedonfactandtheory.5.Thestatement“Theoriesarefacts”maybecalled.[A].ametaphor.[B].aparadox.[C].anappraisaloftheinductiveanddeductivemethods.[D].apun.Vocabulary1.inductive归纳法inductionn.归纳法2.deductive演绎法deductionn。

GRE试题(五)

GRE试题(五)阅读部分阅读理解Passage 1Mythology, the source of ancient Greek religion and civilization, has fascinated audiences for thousands of years, but has also been dismissed as mere legend. Scholars over the past few centuries have sought to uncover the truth behind these myths, investigating their origins, meanings, and functions within Greek society. More recently, modern psychology has incorporated the study of mythology into its approach to understanding human behavior, through the concept of archetypes.Archetypes are universal patterns of behavior which manifest in all cultures, and in all individuals. These archetypal patterns tend to be associated with certain personality traits, symbolized by narratives and images that recur across cultures and time periods. The study of these patterns has shed light on the fundamental motivations, conflicts, and struggles that human beings face throughout their lives.Carl Jung, the famous psychologist who pioneered the study of archetypes, believed that myths were expressions of the collective unconscious, a shared reservoir of knowledge, instincts, and experiences that all human beings possess. He argued that the archetypes were the symbolic manifestation of these collective instincts, and that they represented fundamental aspects of the human psyche. By examining the myths that have emerged throughout history, Jung claimed that it is possible to develop a deeper understanding of the human mind, and the universal truths that underlie human behavior.The power of mythology lies in its ability to convey complex psychological insights in a lasting and meaningful way. Myths and fairy tales are often designed to capture the fundamental experiences that human beings face throughout their lives, such as childhood development, gender identity, and the search for meaning and purpose. By providing a rich and nuanced symbolic language for these experiences, mythology enables individuals to explore complex psychological issues in a way that is both accessible and engaging.Q1. According to the passage, what is mythology? A. A system of beliefs originating from ancient Greece B. A collection of legends and fables that are not based on fact. C. The study of archetypes and their role in human behavior. D. An expression of the collective unconscious, through which the psyche can be understood.Q2. What is an archetype? A. A ritual or custom that is specific to a particular culture. B. A universal pattern of human behavior and experience. C. A symbol orimage that has a specific meaning in a particular culture. D. A shared knowledge or experience that is unique to a particular group of people.Q3. What did Carl Jung believe about mythology? A. That myths reveal the fundamental truths about human behavior B. That myths should be dismissed as legends and fables. C. That myths were specific to individual cultures and time periods. D. That myths were the result of a collective conscious rather than an individual one.Passage 2One of the great puzzles of modern science is the question of what makes life possible. Scientists have spent centuries probing the mysteries of the universe, uncovering the fundamental laws that govern the behavior of matter and energy. Yet, despite this remarkable progress, the origins of life itself remain shrouded in mystery.One approach to understanding the origins of life has been to study the building blocks of life, the molecules and compounds that make up the complex structures found in living organisms. These molecules, such as RNA and DNA, are known to carry genetic information from one generation of cells to the next, and are responsible for the complex processes of growth, reproduction, and adaptation that define life.Despite the critical role played by these molecules, scientists have struggled to understand how they could have formed in the first place. The conditions on early Earth, where life is believed to have originated, were harsh and inhospitable, with frequent volcanic eruptions, meteor impacts, and extreme temperature fluctuations. Yet somehow, from this chaotic environment, emerged the complex and resilient structures that define life as we know it.Many theories have been proposed to explain the origins of life, from the eurythermal hypothesis which suggests that life emerged in hot springs or other thermal vents, to the theory of panspermia, which suggests that life was brought to Earth by extraterrestrial beings. While none of these theories has been proven conclusively, they all point to the fact that life is a mysterious and wondrous phenomenon, whose origins may remain forever beyond our understanding.Q1. What is the question that scientists are trying to answer about life? A. Why living things are able to grow and reproduce B. What makes up the complex structures found in living organisms. C. How life itself originated. D. How the laws of physics govern the behavior of matter and energy.Q2. What are RNA and DNA? A. The complex structures found in living organisms. B. The building blocks of life. C. Responsible for the complex processes of growth, reproduction, and adaptation. D. Molecules that carry genetic information from one generation of cells to the next.Q3. What is the theory of panspermia? A. Life emerged in hot springs or other thermal vents. B. Life evolved from simpler forms of matter through natural selection. C. Life was brought to Earth by extraterrestrial beings. D. Life is a result of the fundamental laws that govern the universe.词汇填空There are a number of different factors that can influence 1 cognitive development, including genetics, environment, and life experiences. Scientists have found that 2 environmental factors, such as exposure to toxins or poor nutrition, can have a significant impact on cognitive functioning in both children and adults.One of the key environmental 3 that has been shown to affect cognitive development is early childhood 4. Studies have found that children who grow up in supportive and stimulating environments, where they have access to a rich diversity of experiences and opportunities, tend to have stronger cognitive skills than those who grow up in more deprived environments. This is because the early years are a crucial 5 of brain development, when the foundations for cognitive, emotional, and social functioning are laid.In addition to early childhood experiences, other environmental factors that can affect cognitive development include 6 stress, exposure to toxins such as lead or mercury, and poor nutrition. All of these factors can have a 7 effect on the brain, impairing the development of neural connections and leading to a range of cognitive deficits.Fortunately, many of these environmental 8 can be addressed through targeted interventions, such as early childhood education programs, nutritional interventions, and exposure-reducing measures. By taking steps to create more supportive and nurturing environments, we can help to ensure that all individuals have the opportunity to develop their cognitive potential to the fullest.1. A. early B. academic C. moral D. social2. A. genetic B. environmental C. cultural D. age-related3. A. situations B. factors C. problems D. contexts4. A. education B. influence C. exposure D. experiences5. A. period B. span C. duration D. phase6. A. emotional B. academic C. physical D. social7. A. positive B. negative C. neutral D. supportive8. A. factors B. interventions C. consequences D. experiences句子填空1.Mary was surprised by the news that she fell off her chair.2.It is said that the new restaurant downtown has the best sushi intown.3.Henry has been studying law for several years and hopes to become alawyer.4.My cousin and I both enjoy playing soccer, but he likes to watchbaseball as well.5.Despite her busy schedule, Sarah always finds time to go to the gym.填空匹配A. MarsupialsB. The Great PyramidsC. Classical MusicD. Geothermal EnergyE. Airplanes1.A are a group of mammals that carry their young in pouches.2.B are a series of ancient structures located in Egypt that were built astombs for pharaohs.3.C is a genre of music characterized by its orchestral compositions andformal structure.4.D refers to the use of thermal energy from beneath the Earth’s surfaceto generate electricity.5.E are vehicles that are able to fly using aerodynamic principles andpropulsion systems.。

Archaeologys Quest for the Legendary General

Archaeologys Quest for the LegendaryGeneralArchaeology's Quest for the Legendary General Archaeology has always been a field of great fascination, as it allows us to uncover the mysteries of the past and gain a deeper understanding of our history. One of the most intriguing quests in the world of archaeology is the search for the legendary general, a figure shrouded in myth and mystery. This quest has captured the imagination of historians, archaeologists, and enthusiasts alike, as they seek to unravel the truth behind the tales of this enigmatic figure. The legend of the general has been passed down through generations, with stories of their unparalleled military prowess and strategic genius. It is said that the general led their army to countless victories, conquering vast territories and leaving a lasting impact on the course of history. However, the details of their life and the location oftheir final resting place have remained elusive, fueling the quest for their legacy. For archaeologists, the quest for the legendary general presents a unique and thrilling challenge. The prospect of uncovering artifacts and evidence that could shed light on this mysterious figure is a tantalizing opportunity. The search for the general's tomb, battle sites, and other significant locations associated with their life has driven many archaeologists to embark on ambitious expeditions, braving treacherous terrain and enduring painstaking research in the hopes of making a groundbreaking discovery. Beyond the academic and professional motivations, the quest for the legendary general also holds a deep emotional resonance for those involved. The pursuit of this legendary figure represents a journey into the unknown, a quest for truth and understanding that transcends the boundaries of time. It is a testament to the human spirit's insatiable curiosity and the enduring quest for knowledge and enlightenment. In the realm ofhistorical and cultural significance, the discovery of the legendary general's legacy would undoubtedly have far-reaching implications. Unraveling the truth behind the myths and legends surrounding this figure could provide invaluable insights into the history of warfare, leadership, and the dynamics of power in ancient civilizations. It has the potential to reshape our understanding of thepast and offer a new perspective on the events that have shaped the world we live in today. The quest for the legendary general is not without its challenges and obstacles. The passage of time has obscured many of the clues and traces that could lead to their discovery, and the vastness of the historical record presents a daunting task for those seeking to piece together the puzzle of this enigmatic figure. However, it is precisely these challenges that make the quest all the more compelling and rewarding for those who are drawn to it. In conclusion, the quest for the legendary general represents a captivating and multifaceted endeavor that encompasses the realms of history, archaeology, and human curiosity. It is a testament to the enduring allure of the past and the unyielding drive to uncover its secrets. While the quest may be fraught with challenges, the potential rewards of unraveling the mysteries surrounding this legendary figure are boundless, offering the promise of a profound and transformative understanding of our shared human history.。

雅思阅读判断题解析

雅思阅读判断题解析阅读冲刺丨雅思阅读判断题解析Q2: In cosmic history,radiation dominated universe before matter did so.问题:为什么是选 YES,好象在文章里找不到。

解答:原文第 4 和第 5 自然段描述了过程先后的时间顺序。

Q4:In cosmologists' debates, the big bang and inflation theories defeated their alternatives such as the steady state theory.问题:原文 Cosmologists have settled the disputes that once animated their field, such as the old debates between the big bang theory and the steady state theory and between inflation and its alternatives. Noting in science is absolutely certain, but researchers now feel that their time is best spent on deeper questions, beginning with the cause of the cosmic acceleration. 我看到关于the big bang and inflation theories and the steady state theory 的只有这一段,可是没有表明他们 Q4 啊,为什么 Q4 选TURE,而不是 NOT GIVEN 呢?解答:文章说科学家已经解决了这些争论(have settled the disputes)——要么是同意了老观点,要么是同意了新观点。

chronology词根

chronology词根Chronology词根Chronology词根源于希腊语中的χρόνος,意为时间或时期。

它是许多英文单词的基础,这些单词描述了我们对时间和事件的理解。

在本文中,我们将探讨一些基于chronology词根的单词,并了解它们在日常生活中的应用。

一、chronologyChronology是希腊语χρόνος的一个派生词,表示按照时间先后顺序排列事件的学问。

Chronology在历史学和天文学等领域有着广泛的应用。

在历史学中,chronology用于描述事件、人物和文化在历史时间中的位置。

在天文学中,chronology则用于描述天体的运动和位置。

二、chronologicalChronological是由chronology词根派生的形容词,意为按照时间顺序排列的。

例如,一本以历史时间顺序写作的书可以被称为chronological book。

同样,在事件、人物和文化的历史研究中,也可以使用chronological来描述研究的时间框架。

三、chronometerChronometer是一个由chronology词根派生的名词,指一种精密的时计器。

Chronometer通常用于测量船舶的经度和航行时间,因此被称为航海钟。

而在现代领域中,Chronometer还被用作精确测量时间的设备,在物理学、天文学和工业制造中都有着广泛的应用。

四、synchronizeSynchronize也是由chronology词根派生的一个动词,意为使两个或多个事件同时发生或达到相同的状态。

例如,在音乐表演中,乐手们需要synchronize他们的演奏,才能创造出和谐美妙的音乐。

而在科学实验中,对于多个测量设备的时间要求非常苛刻,需要保持它们的同步。

五、anachronismAnachronism是一个由chronology词根派生的名词,表示某种事物与其所处的时间不相符的情况。

例如,使用过时的技术或设备在现代领域被认为是anachronism。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

, 臼 u n

易 ZP , 扎n f i c kn

.

口n

d 砌P

be

iz e

o

e

万 砌P

be

,

以c i P g ,

s

ite

s

,

d

c a

—

o n

ly

v e r

y v a g u e l im it s o f g l a c i a t iO n c a n b e dr a w n

x c e

n s

S in

Ou th

g

la

c

in tio

n s

l o 7 8 .0 1 3 M

d

W

n

.

) hQv

i2

n n

id e

c

n tt

e d 扛

A

.

m e

(C o

,

2004)

ly

a n

ia t io

n o

the

N

e

t l、 7 c o r r le

,

ta

te

ith M l S i 6

.

d 6

in

lu d in g th e

p

d

口n

d 砌已

^, 移n

口,

一

r e s 0

1u t i O n

s

c a

e a r s a g o f g la c ia l th a n k s to in

n

y

(T r i p a n i

se

e t a

1

s

.

,

o

q

u e n c e s

ha

a n

n o v a

tio n s

b e in g d r e fl n e

e o

o

f G

gr aphy

u

iv

b u 唱 G e r n l a n y E m 以 i Z? Do e r s ity o f c a m b rid g e :

z 扣 已馏 g ,

已向 抛坶 e

d @ 扫 5 “ 血

m

6

“憎

.

dg

,

w n

in g s tr e

t

c

a m

br id g e c B 2 3 E N

重庆维普

2i l

b y J 说r g e

n

E h te

r s

i

a n

d P h i lip G ib b a 心

E

1 G

x

e o

te

n

t

a n

,

d

c

h

,

r o n o

84

一

lo g y

m n

, ,

0

f

.

ห้องสมุดไป่ตู้

Qu

—

a

te

r n a r

.

y g la

.

c

ia tio

g la nd

ln

n

r e c e n s

t

IN

OUA

ie

w e re s

p

Fo

ie

c t

the

e x

te n t

P

o

f

P k ts to

c

c e n e

44 de

m

il li o de

以c in f iD n 譬, 0

Z 向 口s 易 P 已甩 d i 譬i “z , V

ts n : v

m

.

, 挖口 p

is p he 1c

e

da te

S

ba

c

k

h e p n ! s e n t Ic e A g e In t h e P 口l n e o R e n e

.

l d a tin g

一

t e c h n iq u e s

a n

d thr

o u

in p a rt ic u l a r f b r th e l a te g h Ou t th e H Olo c e n e

r

2 0 0 8 ) G r e a te a c h ie V e d

.

r

pre

o Ve r

c

is io ric

n

in th e

th e la s t tw o

a

m e n

ts

in

a n

n u m e

gy

。 f e Ve n

}n

n

d T he

.

On s e

t o

to

lf

n

t

in b o th h e

e

c P e n

Th

The

the

v a

e

0 n s e

t

0

B P

A ta

r

kn

n n

d

Ⅱn c

n

e r r a

a

e

t F

He s

n

Ro

.

t

v

he ic

i ( 把n

s

f g la

c

ia tio

n

口d v 口n c P

. d 忽, f血 P

以n j, z f忍 e n e

y

fo

他

r

E

n r

~ P te i s

c

m Os t a

c a s e s

th e tr a c e s o f th o s e e a r lv

a n

g

la

ia t io

n s

a re

r e s

t r ic t e d t O i n

div idu

.

l

—

芎, 九日 i n s p 如 f in g , n n d ic e s he e t s is c e n e

E

n

n

2 c E

a m

—

m

l o 西s c h e s L a n d e s a m t B m s t r a s s e d g e Qu a te m a r y D e p a n m e n t b矗 n i t :p l g I @ c n m a c H k

,

. .

,

D 205 39 Ha

’

br

k a Io

w a

a re a

the

USA ia tio

n s o

.

In

A la s k d m

,

a

d in

,

.

M idd le

d L

a

te

P le is tOc

e n e

G

r e e n

d

ln

n

d

.

NOr th A ic

P

o n

m e r

已P 办

ic

fs

n n

d

s o

m

、

娩

m

m OSt

S D 聪f 庇 A

2 6 kn

.

, " e

—c

In

以 s

iz

S

P 以易 , P

s

7n P d 向,

已 P旷已, ,易

加阳

d fro m

to c

g ta

ia t io

以c i以f iD n Z 口 f 已r 譬, n ( 2 6 _ () 7 8 M

. .

E

o n s e t o

) hn

m o s

be

P a la

s

e o g e n e

m o u n

f th e p I. e s e n t Ic e A g e in b Ot h h e m i s p h e r e I n t h e M i Oc e n e g l a c ia t io n b e c a m e

p

o W n

.

.

A

n u m

f M iddle P le is to

e n

t iO n s

in ric

a s

lu d e

the

m n a

G

to

re a t e t Of

a

P a ta 1

.

g o n

ia

n a n

G 1a c i a t i O n d the

e a r

in

g la

s o u c

th e m

.

s

d a te

e s ta

s

ba c k

In E

to

,

b lis h e d in

.

po n e

m n n

、 7p8 r ts o

f the

,

W 0 r

凇 曲 Mt 汛

J r

t

c n Se s 坶

—

riO u

t a in

a r e a s

,

for

e x a m

p le in A la s k a a n d Ic e l a n d