Chapter Twelve Discourse Translation2

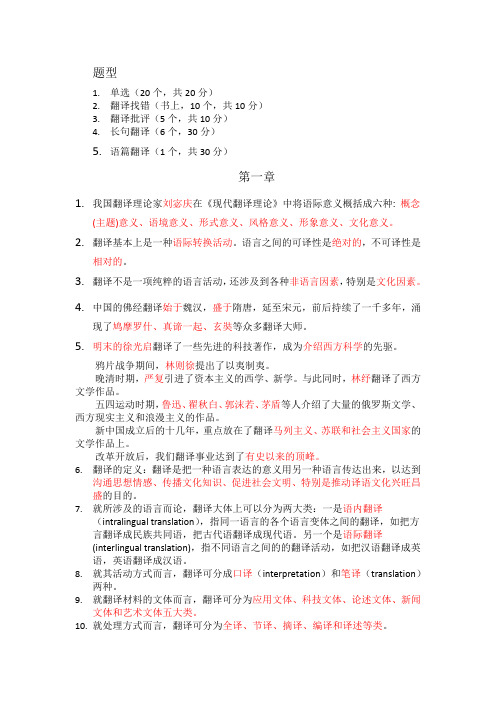

《翻译研究入门理论与应用》总结笔记

Chapter1Translation can refer to the general subject field,the product or the process.The process of translation between two different written languages involves the translator changing an original written text in the original verbal language into a written text in a different verbal language.Three categories of translation by the Russian-American structuralist Roman Jakobson1intralingual translation语内翻译:Rewording,an interpretation of verbal signs by means of other signs of the same language;2interlingual translation语际翻译:Translation proper*,an interpretation of verbal signs by means of some other language;3intersemiotic translation语符翻译transmutation,an interpretation of verbal signs by means of signs of non-verbal sign systems.History of the discipline1,From late eighteenth century to the1960s:part of language learning methodology Translation workshop,comparative literature,contrastive analysis2,James S Holmes“the name and nature of translation studies”(founding statement for the field)3,1970:Reiss:text typeReiss and Vermeer:text purpose(the skopos theory)Halliday:discourse analysis and systemic functional grammar4,1980The manipulation school:descriptive approach,polysystem5,1990Sherry Simon:Gender researchElse Vieira:Brazilian cannibalist schoolTejaswini Niranjana:Postcolonial translation theoryLawrence Venuti:cultural-studies-oriented analysisHolmes’s map of translation studiesThe objectives of the pure areas of research:1,descriptive translation theory:the description of the phenomena of translation2,translation theory:the establishment of general principles to explain and predict such phenomenaPure:theoretical and descriptiveDTS:descriptive translation studies1,product-oriented DTS:existing translations,text(diachronic or synchronic)2,function-oriented DTS:the function of translations in the recipient sociocultural situation (socio-translation studies or cultural-studies-oriented translation)3,process-oriented DTS:the psychology of translation(later think-aloud protocols)Relation between Theoretical and descriptiveThe results of DTS research can be fed into the theoretical branch to evolve either a general theory of translation or,more likely,partial theories of translation.Partial theories1,Medium-restricted theories:translation by machine and humans2,Area-restricted theories:3,Rank-restricted theories:the level of word,sentence or text4,Text-type restricted theories:discourse types or genres5,Time-restricted theories:6,Problem-restricted theories:Applied branch of Holmes’s framework:translator training,translation aids and translation criticism.Translation policy:the translation scholar advising on the place of translation in societyChapter2translation theory before the twentieth centuryLiteral vs.free debateCicero(first century BCE):I did not hold it necessary to render word for word,but I preserved the general style and force of the language.Horace:producing an aesthetically pleasing and creative text in the TL.St Jerome:I render not word for word,but sense for sense.Martin Luther:1,non-literal or non-accepted translation came to be seen and used as a weapon against the Church.2,his infusion of the Bible with the language of ordinary people and his consideration of translation in terms focusing on the TL and the TT reader were crucial.“Louis Kelly:Fidelity: to both the words and the perceived senseSpirit:1, creative energy or inspiration of a text or language, proper to literature; 2, the Holy Spirit.Truth: content17 century:Early attempts at systematic translation theoryCowley: imitationCounter the inevitable loss of beauty in translation by using our wit or invention to create new beauty;he has ‘taken, left out and added what I please’John Dryden reduces all translation to three categories: the triadic model(约翰 德莱顿的三分法:“直译”、意译”与“仿译”) 1, metaphrase: word for word translation2, paraphrase : sense for sense translation3, imitation : forsake both words and senseEtienne Dolet: a French humanist, burned at the stake for his addition to his translation of one of Plato’s dialogues.Five principles:① The translator must perfectly understand the sense and material of the original author,although he should feel free to clarify obscurities.②The translator should have a perfect knowledge of both SL and TL , so as not to lessen the majesty of the language.③The translator should avoid word-for-word renderings.④The translator should avoid Latinate and unusual forma .⑤The translator should assemble and liaise words eloquently to avoid clumsiness.Alexander Fraser TytlerTL-reader-oriented definition of a good translation: That, in which the merit of the original work is so completely transfused into another language, as to be as distinctly apprehended, and as strongly felt, by a native of the country to which that language belongs, as it is by those who speak the language of the original work.Three general rules:I. That the Translation should give a complete transcript of the ideas of the original work.II. That the style and manner of writing should be of t he same character with that of the original.III. That the Translation should have all the ease of original composition.—— A. F. Tytler: Essay on the Principles of TranslationTytler ranks his three laws in order of comparative importance:Ease of composition would be sacrificed if necessary for manner,and a departure would be made from manner in the interests of sense.Friedrich Schleiermacher:the founder of modern Protestant theology and of modern hermeneuticsHermeneutics:a Romantic approach to interpretation based not on absolute truth but on the individual’s inner feeling and understanding.2types of translators:1,Dolmetscher:who translates commercial texts;2,Ubersetzer:who works on scholarly and artistic texts.2translation methods:1,translator leaves the reader in peace,as much as possible,and moves the author towards him. Alienating method2,translator leaves the writer alone,as much as possible,and moves the reader towards the writer. Naturalizing methodThe status of the ST and the form of the TLFrancis Newman:emphasize the foreignness of the workMatthew Arnold:a transparent translation method(led to the devaluation of translation and marginalization of translation)Chapter3Equivalence and equivalent effectRoman Jakobson:the nature of linguistic meaningSaussure:the signifier(能指)the spoken and written signalThe signified(所指)the concept signifiedThe signifier and signified form the linguistic sign,but that sign is arbitrary or unmotivated.1,There is ordinarily no full equivalence between code-units.Interlingual translation involves substituting messages in one language not for separate code-units but for entire messages in some other language.2,for the message to be equivalent in ST and TT,the code-unit will be different since they belong to two different sign systems which partition reality differently.3,the problem of meaning and equivalence thus focuses on differences in the structure and terminology of languages rather than on any inability of one language to render a message that has been written in another verbal language.4,cross-linguistic differences center around obligatory grammatical and lexical forms.They occur at the level of gender,aspect and semantic fields.Eugene Nida1,an orthographic word has a fixed meaning and towards a functional definition of meaning in which a word acquires meaning through its context and can produce varying responses accordingto culture.2,meaning is broke down into a,linguistic meaning,b,referential meaning(the denotative ‘dictionary’meaning指称,字面)and c,emotive meaning(connotative隐含).3,techniques to determine the meaning of different linguistic itemsA,analyze the structure of wordsB,differentiate similar words in relaxed lexical fields3techniques to determine the meaning of different linguistic items1,Hierarchical structuring,differentiates series of words according to their level,2,Techniques of componential analysis(成分分析法)identify and discriminate specific features of a range of related words.3,Semantic structure analysis:Discriminate the sense of a complex semantic termChomsky:Generative-transformational model:analyze sentences into a series of related levels governed by rules.3features1,phrase-structure rules短语结构规则generate an underlying or deep structure which is2,transformed by transformational rules转换规则relating one underlying structure to another, to produce3,a final surface structure,which itself is subject to形态音位规则phonological and morphemic rules.The most basic of such structures are kernel sentences,which are simple,active,declarative sentences that require the minimum of transformation.Three-stage system of translationAnalysis:the surface structure of the ST is analyzed into the basic elements of the deep structure Transfer:these are transferred in the translation processRestructuring:these are transferred in the translation process and then restructured semantically and stylistically into the surface structure of the TT.Back-transformation回归转换(Kernels are to be obtained from the ST structure by a reductive process)Four types of functional class:events,objects,abstracts and relationals.Kernels are the level at which the message is transferred into the receptor language before being transformed into the surface structure in three stages:literal transfer,minimal transfer最小单位转换and literary transfer.Formal equivalence:focuses attention on the message itself,in both form and content,the message in the receptor language should match as closely as possible the different elements in the source language.Gloss translations释译Dynamic equivalence is based on what Nida calls the principle of equivalent effect,where the relationship between receptor and message should be substantially the same as that which existed between the original receptors and the message.Four basic requirements of a translation1,making sense2,conveying the spirit and manner of the original3,having a natural and easy form of expression4,producing a similar response.NewmarkCommunicative translation attempts to produce on its reader an effect as close as possible to that obtained on the readers of the original.Semantic translation attempts to render,as closely as the semantic and syntactic structures of the second language allow,the exact contextual meaning of the original.Literal translation is held to be the best approach in both communicative translation and semantic translation.One of the difficulties encountered by translation studies in systematically following up advances in theory may indeed be partly attributable to the overabundance of terminology.Werner KollerCorrespondence:contrastive linguistics,compares two language systems and describes contrastively differences and similarities.Saussure’s langue(competence in foreign language) Equivalence:equivalent items in specific ST-TT pairs and contexts.Saussure’s parole (competence in translation)Five types of equivalenceDenotative equivalenceConnotative equivalenceText-normative equivalencePragmatic equivalence(communicative equivalence)Formal equivalence(expressive equivalence,the form and aesthetics of the text)A checklist for translationally relevant text analysis:Language functionContent characteristicsLanguage-stylistic characteristicsFormal-aesthetic characteristicsPragmatic characteristicsTertium comparationi in the comparison of an ST and a TTChapter5functional theories of translationKatharina Reiss:Text TypeBuilds on the concept of equivalence but views the text,rather than the word or sentence as the level at which communication is achieved and at which equivalence must be sought.Four-way categorization of the functions of language(Karl Buhler,three)1,plain communication of facts,transmit information and content,informative text2,creative composition,expressive text3,inducing behavioral responses,operative text4,audiomedial text,supplement the other three functions with visual images,music,etc.Different translation methods for different texts1,transmit the full referentical or conceptual content of the ST in plain prose without redundancy and with the use of explicitation when required.2,transmit the aesthetic and artistic form of the ST,using the identifying method,with the translator adopting the standpoint of the ST author.3,produce the desired response in the TT receiver,employing the adaptive method,creating an equivalent effect among TT readers.4,supplementing written words with visual images and music.Intralinguistic and extralinguistic instruction criteria1,intralinguistic criteria:semantic,lexical,grammatical and stylistic features2,extralinguistic criteria:situation,subject field,time,place,receiver,sender and affective implications(humor,irony,emotion,etc.)Holz-Manttari:Translational actionTakes up concepts from communication theory and action theoryTranslation action views translation as purpose-driven,outcome oriented human interaction and focuses on the process of translation as message-transmitter compounds involving intercultural transfer.Interlingual translation is described as translational action from a source text and as a communicative process involving a series of roles and players.The initiatorThe commissionerThe ST producerThe TT producerThe TT userThe TT receiverContent,structured by what are called tectonics,is divided into a)factual information and b) overall communicative strategy.Form,structured by texture,is divided into a)terminology and b)cohesive elements.Value:place of translation,at least the professional non-literary translation within its sociocultural context,including the interplay between the translator and the initiating institution.Vermeer:Skopos theorySkopos theory focuses above all on the purpose of the translation,which determines the translation methods and strategies that are to be employed in order to produce a functionally adequate result(TT,translatum).Basic rules of the theory:1,a translatum is determined by its skopos;2,a TT is an offer of information in a target culture and TL concerning an offer of information in a source culture and SL.3,a TT does not initiate an offer of information in a clearly reversible way4a TT must be internally coherent5a TT must be coherent with the ST6the five rules above stand in hierarchical order,with the skopos rule predominating.The coherence rule,internally coherent,the TT must be interpretable as coherent with the TT receiver’s situation.The fidelity rule,coherent with the ST,there must be coherence between the translatum and the ST.1,the ST information received by the translator;2,the interpretation the translator makes of this information;3,the information that is encoded for the TT receivers.Intratextual coherence intertextual coherenceAdequacy comes to override equivalence as the measure of the translational action. Adequacy:the relations between ST and TT as a consequence of observing a skopos during the translation process.In other words,if the TT fulfills the skopos outlined by the commission,it is functionally and communicatively adequate.Criticisms:1,valid for non-literary texts2,Reiss’s text type approach and Vermeer’s skopos theory are considering different functional phenomena3,insufficient attention to the linguistic nature of the ST nor to the reproduction of microlevel features in the TT.Christiane Nord:translation-oriented text analysisExamine text organization at or above sentence level.2basic types of translation product:1,documentary translation:serves as a document of a source culture communication between the author and the ST recipient.2,instrumental translation:the TT receiver read the TT as though it were an ST written in their own language.Aim:provide a model of ST analysis which is applicable to all text types and translation situations.Three aspects of functionalist approaches that are particularly useful in translator training1,the importance of the translation commission(translation brief)2,the role of ST analysis3,the functional hierarchy of translation problems.1,compare ST and TT profiles defined in the commission to see where the two texts may diverge Translation brief should include:The intended text functions;The addressees(sender and recipient)The time and place of text receptionThe medium(speech and writing)The motive(why the ST was written and why it is being translated)2,intratextual factors for the ST analysisSubject matterContent:including connotation and cohesionPresuppositions:real-world factors of the communicative situation presumed to be known to the participants;Composition:microstructure and macrostructure;Non-verbal elements:illustrations,italics,etc.;Lexic:including dialect,register and specific terminology;Sentence structure;Suprasegemtal features:stress,rhythm and stylistic punctuationIt does not matter which text-linguistic model is used3,the intended function of the translation should be decided(documentary or instrumental) Those functional elements that will need to be adapted to the TT addressee’s situation have to be determinedThe translation type decides the translation style(source-culture or target culture oriented)The problems of the text can then be tackled at a lower linguistic levelChapter6discourse and register analysis approachesText analysis:concentrate on describing the way in which texts are organized(sentence structure,cohesion,etc.)Discourse analysis looks at the way language communicates meaning and social and power relations.Halliday’s model of discourse analysis,based on systemic functional grammarStudy of language as communication,seeing meaning in the writer’s linguistic choices and systematically relating these choices to a wider sociocultural framework.Relation of genre and register to languageGenre:the conventional text type that is associated with a specific communicative function Variables of Register:1,field:what is being written about,e.g.a delivery2,tenor:who is communicating and to whom,e.g.a sales representative to a customer3,mode:the form of communication,e.g.written.Each is associated with a strand of meaning:Metafunctions:概念功能(ideational function)、人际功能(interpersonal function)和语篇功能(textual function)Realized by the lexicogrammar:the choices of wording and syntactic structureField--ideational meaning—transitivity patternsTenor—interpersonal meaning—patterns of modalityMode—textual meaning—thematic and information structures and cohesion及物性系统(transitivity)情态系统(modality)、主位结构(theme structure)和信息结构(information structure)。

张春柏英汉对比与翻译

4) 幽幽岁月,苍海桑田. 5) 门铃一响,来了客人,从不谢客,礼当 接待. 5) Suddenly the bell rang, announcing the arrival of a visitor. As I had never rejected any guest, I thought I should this one as well.

五四运动的杰出的历史意义在于它带着为辛亥革命还不曾有的姿态这就是彻底地不妥协地反帝国主义和彻底地不妥协地反封建主义

汉英对比与翻译教学

华东师范大学 张春柏

I. 为什么要对比 (why): to help improve the teaching/learning of translation, composition, and grammar

II. 比什么 比什么(What): From words to sentences and discourse, as well as ways of thinking.

My purpose here: to call our attention to the importance of form in the teaching/learning of translation 1) word form: morphology (as well as sounds, esp. in poetry) 2) sentence form: structure 3) cohesion: how sentences are connected to each other to form a coherent piece of discourse

3) 五四运动是反帝国主义的运动,又是反封

建的运动。五四运动的杰出的历史意义,在 于它带着为辛亥革命还不曾有的姿态,这就 是彻底地不妥协地反帝国主义和彻底地不妥 协地反封建主义。五四运动所以具有这种性 质,是……五四运动是在当时世界革命号召 之下,是在俄国革命号召之下,是在列宁号 召之下发生的。五四运动是当时无产阶级世 界革命的一部分。……

功能对等理论指导下的生态类科技文本英汉翻译实践报告

大连理工大学专业学位硕士论文摘要随着全球经济飞速发展,城市化的速度也在逐渐提升,空气污染、气候变化等问题也成为了当今环境治理方面的两大重要挑战。

中国作为世界上最大的发展中国家,经济发展速度前所未有,而在建设社会主义现代化强国的过程中,生态环境建成为了社会主义现代化建设的重要内涵。

在此背景下,译者决定翻译《蓝绿解决方案》。

本书主要介绍了来自帝国理工学院的科研团队所研发的创新性城市环境治理解决方案,为城市治理提供新的思路。

该方案在许多国家和地区已经开展了试点工作,而在国内的应用仍是空白。

本次翻译实践的主要目的就是通过对本书的翻译,为我国相关领域人员提供更有价值的借鉴与参考,并为生态类科技英文文本的翻译提供一定的参考和启示。

译者通过对于原文本和同类科技文本进行分析,结合科技文本的文体特点和语法特点,在功能对等理论的指导下,分析了科技文本的翻译过程中存在的问题,通过对翻译技巧的探讨,撰写了本篇翻译实践报告。

本报告包括任务描述、翻译过程、案例分析和结论部分。

其中,案例分析部分为此报告的核心。

译者以奈达的功能对等理论作为指导,从词汇,句法,语篇三个层面探讨翻译过程中遇到的问题,并提出相应的解决办法。

在词汇层面,译者提出了增词、减词,以及对于术语和一般词汇进行的直译或通过语境进行翻译。

在句法层面,译者利用词性的转换和语态的转换,根据中英文表达习惯等差异,对于译文的形式进行适当的改变。

为了实现语篇的连贯和对等,译者采用了调序以及增词的方法。

最后,报告将总结在本次翻译实践中总结的翻译方法以及整个工作的总结以及局限性。

关键词:功能对等理论;科技文本翻译;英汉翻译A Report on E-C Translation of Ecological EST under the Guidance of Functional Equivalence TheoryA Report on E-C Translation of Ecological EST under the Guidance ofFunctional Equivalence TheoryAbstractWith the rapid development of the global economy, the speed of urbanization is gradually increasing, and problems such as air pollution and climate change have become two major challenges in environmental governance. As the largest developing country in the world, China has experienced an unprecedented economic increasing. The construction of the ecological environment has been a core of socialist modernization. Considering the background, the translator decides to translate Blue Green Solutions. This book mainly introduces innovative urban environmental governance solutions developed by the scientific research team of Imperial College to provide new ideas for urban governance. The program has already carried out pilot work in many countries and regions, but its application in China is still blank. The main purpose of this translation practice is to provide a more valuable reference for the relevant fields in China through the translation of this book and to provide reference and inspiration for the translation of ecological EST texts.The translator analyzes the source text and the parallel text combining with the stylistic and grammatical characteristics of the EST text, under the guidance of functional equivalence theory, solves the problems encountered in the translation process and finally writes this translation practice report.This report includes task introduction, translation process, case study and conclusion. The case study is the core of this report. The translator uses Nida’s functional equivalence theory as a guide to explore the problems encountered in the translation process from the three levels of lexical level, syntactic level, and discourse level, and proposes corresponding solutions. At the lexical level, the translator uses addition and omission, as well as literal translation of terms and contextual translation of common words. At syntactic level, the translator uses conversion to make appropriate changes to the form of the translation based on differences in Chinese and English expression habits. In order to achieve coherence and equivalence at discourse level, the translator adopts the method of rearrangement and addition. Finally, the report will have a conclusion of the translation methods in the translation practice and the summary and limitations of the entire work.Key Words:Functional Equivalence; EST Translation; E-C Translation目录摘要 (I)Abstract (II)Chapter 1 Introduction (1)1.1 Background of the Translation Project (1)1.2 Significance of the Translation Project (2)Chapter 2 Theoretical Basis (3)2.1 EST and EST Translation (3)2.1 Overview on Nida’s Translation Theory (3)2.2 Nida’s Functional equivalence (4)2.3 The Application of Functional Equivalence (6)Chapter 3 Translation Process (7)3.1 Pre-Translation Preparation (7)3.2 Analysis of the Source Text (8)3.2.1 Lexical features (8)3.2.2 Syntactic Features (9)Chapter 4 Case Study (11)4.1 Translation at Lexical Level (11)4.1.1 Literal Translation (11)4.1.2 Contextual Translation (13)4.1.3 Amplification and Omission (14)4.2 Translation at Syntactic Level (15)4.2.1 Nominalizations to Verbs (15)4.2.1 Passive V oice to Active V oice (16)4.3 Translation at Discourse Level (17)Chapter 5 Conclusion (21)5.1 Findings in the Translation Process (21)5.2 Summary and Limitations (22)References (23)Appendix I Term Bank and Abbreviation (25)Appendix II Source Text and Target Text (29)Acknowledgments (88)大连理工大学学位论文版权使用授权书 (89)Chapter 1 Introduction1.1 Background of the Translation ProjectUrbanization is characteristic of the modern world. At present, economic and social development is in an important strategic transition period, and urbanization has been given an important historical mission. However, the impact of urbanization on the ecological environment cannot be ignored. How to improve the quality and benefits of urbanization development in accordance with the concept of green development is a challenge faced by China and all countries in the world. As an applied discipline, the translation should make its due contribution to people’s further understanding of the world. It is the mission of our translation students to translate valuable foreign books or materials into Chinese and introduce them to Chinese people to expand international cooperation and promote the better development of our economy.My translation project is a technological report entitled Blue Green Solutions, edited by Čedo Maksimovic and some other contributors. This technological report was fun ded by Climate-KIC, which is a Knowledge and Innovation Community supported by the European Institute of Innovation and Technology. Čedo Maksimovic, the major contributor to this guidebook, is from Imperial College London. His research fields include applied fluid mechanics in urban water systems: storm drainage, urban flooding water supply and interactions of urban water systems and infrastructure with the environment. In addition to lecturing on the MSc and UG courses, Prof. Maksimovic serves as a project coordinator of EPSRC, EU and UNESCO projects in the UK, and other projects in Europe and in other continents dealing with the above topics. This translation project comes from the BGS translation cooperation project that my supervisor discussed with the author at Imperial College.Blue Green Solutions is a guidebook that presents an innovative framework to systematically unlock the multiple benefits of city natural infrastructure [1]. Chapter 1 gives an introduction of Nature Based Solutions (NBS) and Blue Green Solutions (BGS) to prove that the NBS is a mono-function way, which has become increasingly unsuitable for cities nowadays. The Blue Green Dream (BGD) project created a framework for synergizing urban water and plant systems to provide effective, multifunctional Blue Green Solutions (BGS) to support urban adaptation to climatic change. Chapter 2 describes the development process of BGS, the limitations of traditional NBS in urban transitions and the innovative urban transition of BGS. It is pointed out that the BGS is not based on a single discipline to provide solutions for urban transition but is based on the coordination and communication of multiple discipline teams. Chapter 3 describes the design process when planning urban transition with BGS, and reduces the cost to the minimum by coordinating the participation degree of each stakeholder to realizeA Report on E-C Translation of Ecological EST under the Guidance of Functional Equivalence Theorythe maximization of the benefits of urban transition. Chapter 4 describes how to quantify the economic and ecological benefits of the blue-green solution. Chapter 5 is a case study of six pilot units.1.2 Significance of the Translation ProjectThis translation project is significant in the following two senses:Academic significance. BGS elaborated on the relationship between urban design and climate change from the perspective of urbanization. Each contributor is an expert in environmental engineering, civil engineering, energy and economics, and explains the whole process of BGS from pre-design to construction to benefit evaluation. After an in-depth study of climate change, they created new solutions that were different from traditional NBSs. Secondly, the study of climate change involves many factors, including science, energy, politics and economy. Therefore, it is not a simple matter to make it clear. This guidebook makes a detailed case study of the communities, campuses and other places that adopt the BGS to realize construction or renovation, then proves the correctness and innovation of the theory with practice. So this guidebook provides a good platform for the target language readers and related researchers.Realistic significance. The special feature of the BGS is that its target group can be a professional group, as well as developers, factory managers, governments, investors and other stakeholders. This paper presents the theoretical knowledge that BGS takes and the benefits that BGS brings. Translating this guidebook into Chinese is valuable for relevant experts and stakeholders to use for reference in designing urban construction or renovation. In addition, translating this paper into Chinese will provide a window for the public to understand the close relationship between urban development and climate change. As the biggest developing country in the world, China will contribute significantly to global environmental protection and economic development by running her own affairs well. Therefore, translating this book into Chinese can provide more reference programs for China in the construction of ecological civilization.大连理工大学专业学位硕士论文Chapter 2 Theoretical Basis2.0 EST and EST TranslationIn the first chapter, the content of the source text is about the new research in the area of environmental engineering, which is typical English for Science and Technology (EST). Many related studies on the translation of EST texts have shown that the style of EST is characterized by standard language, objective statement, strong logic, a large amount of information and a high degree of specialization. Compared with literary translation, scientific translation requires a translation that is accurate and expressive in content, well-structured and well-defined [2,3]. Therefore, when translating EST texts, the translator must analyze the characteristics and language features of the source text.In the translation process, the translator believes that the ultimate purpose of EST translation is using simple, accurate language to express the same concepts and information as the original to promote scientific and technological knowledge. Therefore, in addition to considering the basic concepts of the translation such as “literal translation” and “parallel translation,” it should also pay attention to the equivalence in the function of the target text and the source text to make sure that the reader or audience may have the same response of the source language receptor [4]. Therefore, from the perspective of the requirements of EST translation and the reader’s response, EST translation coincides with Nida's functional equivalence theory.2.1 Overview on Nida’s Translation TheoryNida’s basic translation ideas can be summarized in the following three points. ①Translation is a communicative activity between languages. ②The goal of translation is to transfer the meanings. ③In order to transfer meanings, the form of the source texts can be adjusted [4]. Nida regards translation as a cross-language, cross-cultural communicative activity, which is in line with the purpose of the EST translation, that is, to convey the latest research in related disciplines, and to provide new research methods for the domestic academic circles. For the second point, Nida’s explanation is: To make the source text reader and target text readers communicate with each other, the meaning of the source texts must be clearly transferred. This is also the most basic requirement for translation of the source text. Since the habit of Chinese and English expressions are not the same, in order to achieve translation, the forms of language expressions must be changed. EST has its own textual characteristics, and we must correctly grasp these characteristics in translation, and reproduce the information of the source language with the closest and natural equivalents[5]. This is the core point of functional equivalence theory.A Report on E-C Translation of Ecological EST under the Guidance of Functional Equivalence TheoryIn addition to functional equivalence theory, Nida believes that the translation process can be divided into following four stages, namely analysis, transfer, restructuring and test [5]. ①Analysis is mainly to determine the meaning of the original text. The meaning here refers to the meaning of words, phrases, grammar, syntax and discourse structure. That is, the translators must grasp both the meaning of the content and the characteristics of the form. ②Transfer is to transfer the information analyzed from the source language to the target language. ③Restructuring is to reorganize the words, syntax and discourse features to achieve maximum comprehension of the target receptor. ④Test. To expose the deficiency of translation based on testing the reader’s response. Transfer, restructuring and test is a process that needs to be repeated in the translation process in order to do the best translation. Therefore, in the translation process, the characteristics of the original text should be analyzed first. After having a complete grasp of the content and linguistic characteristics of the original text, it should be translated sentence by sentence.2.2 Nida’s Functional equivalenceThe core of Nida’s “f unctional equivalence” theory is to make the translated text arouse the same effect on target readers as close as possible as the source text on its readers [6]. Dynamic equivalence (or functional equivalence) is an approach to translation in which the original language is translated “thought for thought” rather than “word for word” as in form equivalence. For Nida, in translation, the meaning is first, and form is second, namely the priority of functional equivalence over formal equivalence. The “function” of a language refers to the verbal role that a language can play in its use. Different languages must be different in grammar or expression habits, but they can have the same or similar functions to each other. So that the key to translation is the target text can produce the corresponding effect of the source text in the cultural background of the source language in the cultural background of the target language. Nida emphasizes that the key to translation is “equivalence,” “in formation,” “meaning,” and “style” [7].As mentioned earlier, “translation is a communicative activity,” the purpose of translation is to seek the “equivalence” of the source language and target language. The information conveyed by translation is not only superficial textual information but also deep cultural and social information. Nida expounds dynamic equivalence from four aspects: lexical equivalence, syntactic equivalence, textual equivalence and stylistic equivalence [8].(1) Lexical equivalence: The meaning of a word is decided by its use in the language. Find the corresponding meaning in the target language.(2) Syntactic equivalence: Translators must not only know whether the target language has such a structure, but also understand how often this structure is used.大连理工大学专业学位硕士论文(3) Discourse equivalence: In the discourse analysis, we can not only analyze the language itself but also how the language conveys the meaning and function in a specific context.(4) Stylistic equivalence: Translation works of different styles have their own unique language characteristics. Only when mastering both the source and target language characteristics and being proficient in using both languages, can translators create a translation work that truly reflects the source language style.Under the framework of functional equivalence theory, EST translation should follow the following principles [9]:(1) Faithfulness to the original author: in translation, we should pay special attention to the unity of the target text and the original text, and follow the principle of “faithfulness to the original author.” On the basis of this principle, the translator should give full play to the role of the original text, requiring the translator not only to understand the thinking mode of the source text but also to fully understand the communicative function of the source text to the source text.(2) Serving the target language receptors: take full account of the r eader’s understanding of the translation and use the most “natural” form of language translation. This “naturalness,” on the condition that the target language recipient’s understanding needs are satisfied, includes two meanings: the translation should be authentic, and the translation should be read in a natural way, so as to avoid translationese.(3) Fully considering the function of information: in the EST translation, the translator should fully consider the cultural background of the target language, and based on this background, fully consider the information function. If the target readers have strong professional knowledge of related fields, maximally retain the original style and words of science and technology in the text, English professional term will not affect their reading and understanding, the target language reader can completely rely on their professional skills to understand English paragraph means of science and technology. If the target language reader has the weak professional knowledge, the translator should strive to achieve the equivalence from words to sentences as far as possible so as not to affect the target language readers to further understand the meaning and improve their reading experiences.In translation practices, Nida believes that the most important equivalence is the semantic equivalence. For EST translation, the author believes that the translator must first grasp the style of EST, that is, the stylistic characteristics of EST must be clarified in the pre-translation preparation. Secondly, translators should adhere to the principle of lexical equivalence and semantic equivalence in translation, so that the content of the source texts has the same effect as the source texts.A Report on E-C Translation of Ecological EST under the Guidance of Functional Equivalence Theory2.3 The Application of Functional EquivalenceAs mentioned above, the core of functional equivalence is that the receptors’ response to the target text is the same as the original response to the source text. Given this, Nida defines translation as “reproducing the source messages in the target language from meanings to stylistic features with the closest natural equivalents[10]”. Guided by functional equivalence theory, the translator of this report tries to seek equivalence as far as possible from perspectives of lexicon, syntax and discourse.First of all, by applying the “functional equivalence theory,” the translator first takes the reader’s response to the text as the most important factor in translation practice from the perspective of the discourse. “Lexical equivalence” emphasizes the equivalence of meaning and part-of-speech in EST translation as well as the equivalence of communication functions by adding and deleting words; “syntactic equivalence” requires translators to get rid of constraints of forms and express the meaning of the source texts clearly and completely. The functional equivalence theory also takes into account the logical relationships between words and between sentences to flexibly change the part of speech. For scientific and technological styles, it is particularly necessary to pay attention to the structures such as passive voice, attributives, adverbials, etc. Based on the first two types of equivalence, translators are required to proceed from the whole passage, reasonably arrange sentence groups, and pay attention to the logical relationship between sentences. “Stylistic equivalence” is the top priority of all equivalence strategies. The writing style of a scientific article should not be similar to literary styles, such as a novel.Secondly, the four steps of translation emphasized in Nida’s theory also play a guiding role in translation practice. The analysis section allows the translator to determine the style and the linguistic features of the source texts before translating. The text analysis before translation facilitates the translator to achieve stylistic equivalence in translation, which is of great significance to the realization of functional equivalence in the EST translation. Transfer and restructuring require translators to flexibly apply various translation strategies in lexical and syntactic translation according to the four translation principles of equivalence and functional equivalence mentioned above, to achieve functional equivalence in translation. In the process of proofreading, the quality of the translated text should be determined according to the standards proposed by the functional equivalence theory, in addition to determining whether the translation achieves four equivalence.The functional equivalence theory points out a way for translators to EST translation, which has great guiding significance for translators’ translation practice.大连理工大学专业学位硕士论文Chapter 3 Translation Process3.1 Pre-Translation PreparationTranslation preparation is necessary for the translation project. For EST translation, according to the functional equivalence theory, the translation should achieve stylistic equivalence with the original text, which requires the translator to have a holistic grasp of the stylistic features of the original text. In this translation practice, the source text has many terms, and consistency of the terms is one of the important criteria to measure the quality of translation and is also one of the important tasks of proofreading. So, it is necessary to have preparation before translation. With careful preparation, the translation work will be effectively completed, and high-quality translation will be delivered in a timely manner. Therefore, after receiving this translation project, the author of this report first makes the following translation preparations.For the terminological consistency, the translator chooses to use computer-aided translation software (hereinafter referred to as CAT). The advantage of CAT is that the same content will not be translated twice, which saves the workload of terminological consistency. In this translation project, the translator uses SDL Trados Studio 2019. Its advantages are shown in the following aspects: translation memory (TM), matching, and termbase (MultiTerm). The memory function and matching function of Trados complement each other. The memory function refers to the automatic storage of the translation and the sorting, establishment and continuous updating of the memory base in the process of translation by Trados, and the matching function refers to the analysis of the source text and the target text with the help of Trados to accurately identify the corresponding sentences and paragraphs, and automatically pop up the matching sentence paragraph when similar sentence paragraphs appear in the following paragraphs. With the help of the memory and matching function of Trados, the source text can be better understood according to the existing translation, qualified translation can be produced, and the consistency of the same type of text can be maintained. MultiTerm can standardize all the professional terms. The translator only needs to establish one or more standard term lists containing the source language and the target language. By opening the corresponding term list in Trados, the system will automatically identify which terms have been defined in the text and give the standard translation, which effectively keeps the terminological consistency and accuracy [11].Because there are a large number of technical terms in “Blue Green Solutions,” the author of this report prepares some dictionaries. In addition to dictionaries, the author prepares relevant translation books, such as A Course in English-Chinese Translation, which is written by Zhang Peiji, Functional Translation Theory and ESP Translation Study written by Wang Miao. In addition, The translator has a preparation of parallel texts. In the EST translation, understandingis the premise. Only when the meaning is understood correctly can a concise and correct translation be produced. English of science and technology covers a wide range of disciplines, and it is difficult for translators to be familiar with or master all the professional terms in various fields. In the process of EST translation, the elaboration and determination of terms require time and effort, and mistranslations often occur due to a lack of professional knowledge and contextual knowledge. By introducing parallel text, the translator can get a general understanding of the common terms and expressions in this field, and turn the terms in the text into his own vocabulary reserve, so as to effectively and accurately solve the problem of term translation[12], so as to ensure accurate and appropriate semantic equivalence during the translation. In addition, Nida’s theory of stylistic equivalence requires that the target text should fulfill the same function of the source text, so as to satisfy the way of expression of the target text. By using parallel text, in addition to the accurate expression of vocabulary, it also contributes to the overall smoothness of the target text and the functional equivalence of the original text. In addition, parallel text can also effectively help translators expand their knowledge, improve their ability to identify various professional terms, and find subtle differences among different meanings with a rigorous attitude, so as to select appropriate translation strategies and convey the original meaning to readers accurately and smoothly. Therefore, the translator prepares relevant parallel texts.3.2 Analysis of the Source TextDifferent from the literary text, the EST text has its own characteristics and features. In order to describe the objective world accurately, the style of science and technology texts should be concise in the form, coherent in the semantic expression, and objective in the use of language.3.2.1 Lexical featuresThe lexical features of the source text include three main points:Terminology. The purpose of science and technology text is to deliver technical information or science facts. To achieve this point, the terminology is widely used in science and technology text to ensure the accuracy of the content. Blue Green Solutions is a technical report which gives a new method in urbanization and city reconstruction, in which numerous terminologies are used to demonstrate the theories proposed in the report. As the following table 1 shows, some terms are demonstrated. The rest of the terms and abbreviations refer to Appendix I.Tab. 3.1 Technical WordsST TTPhotovoltaics 光伏Topography 地形、地貌Adiabatic Cooling 隔热冷却Evapotranspiration 蒸散Semi-technical word. The semi-technical words in the science and technology texts are basically derived from common English vocabulary, which referenced in a professional, scientific and technological field. Most of this type of word polysemy, which has both non-technical and technical meanings [13].Example 1. This means that interventions such as tree pits and green roofs are better equipped to manage, for example, extreme rainfall events.Example 2. A key advantage is that being vegetation based, their construction and operation has a low carbon and materials footprint.In example 1., “green roofs” is not literally referred to as a roof with green color. It is a concept of “planting on rooftops, balconies, walls, the top of underground garages, overpasses, and other special spaces of buildings and structures that are not connected to the ground, nature, and soil [14].”In example 2., “footprints” refers to “The area of a biologically productive area that is needed to maintain the survival of a person, region, or country, or that can accommodate waste emitted by humans [15].”Abbreviation. Abbreviations are easy to write, identify and remember. In science and technology English, there are a large number of vocabulary abbreviations and abbreviations.Example 3. The Blue Green Dream (BGD) project built upon and expanded the SUDS and WSUD Historical development of Blue Green Solutions (BG-S) via SUDS and WSUD concept to produce a systematic, quantitative framework for utilizing the full range of ecosystem services that NBS provide, yielding Blue Green Solutions.3.2.2 Syntactic FeaturesThe syntactic features in the source text include the following two main points:Passive voice. According to statistics, one-third of the verbs in science and technology texts are used in passive forms. The science and technology texts focus on narrative and reasoning. The reader pays attention to the author’s point of view or the content of the invention, not the author himself. To emphasize and highlight the author’s point of view and inventions, more passive voices are used in EST texts than general English texts [16].Example 4. All interactions are therefore systematically mapped, modelled and quantified to enable the design team to make a decision using quantified performance indicators.。

英语翻译理论

3. pragmatism: pragmatic ways of considering and dealing with things; pragmatic: dealing with matters in the way that seems best under the actual conditions, rather than following a general principle; concerned with practical results. 实用主义:现代资产阶级哲学的一个派别,创始于美国。它 的主要内容是否认世界的物质性和真理的客观性,把客观存 在和主观经验等同起来,认为有用的就是真理,思维只是应 付环境解决疑难的工具。 Therefore, pragmatism (褒义词)≠实用主义(贬义词)

tablechinesestylisticsynonyms书面语词母亲诞辰清晨逝世散步恐吓口语词妈妈生日早上溜达吓唬古语词旧词木匠厨子大夫现代词新词危险木工厨师医生普通用语现在办法安排私下公文用语给予措施部署擅自光亮半夜寂寞文艺作品用语飞翔心灵寂静晶莹子夜寂寥tableenglishstylisticsynonymstranslationsinformalneutralformalliterarybrokeflatbrokehardup穷衣袋空空穷光蛋一个子儿也没有poor贫穷povertystrickenpennilesswantunderprivilegedimpecuniousindigent文不名穷困贫困poopeddogtiredwornoutplayedoutall没劲累死了tired疲劳exhaustedwearyfatiguedspent疲乏疲惫疲惫不堪younglittlepunkkidyoungguylad流氓年青人男孩子小鬼小伙子boyyoungpersonteenager孩年轻人youthstripling年轻人年轻男人tableenglishwordschinesestylisticsynonymswordsexplanatorydescriptiveidiomaticlively生动的栩栩如生irrelevant无关的风马牛不相及identical相同的千篇一律thickdiscretion小心谨慎稳扎稳打eloquence以雄辩的口才娓娓动听greatcontribution巨大贡献丰功伟绩invulnerability无法攻破固若金汤meagerfood简单的食物粗茶淡饭frightened害怕胆战心惊readfollowingpassageformalwordsimportantlawprinciplefirstdiscoveredscientistwhodiedover2000yearsago

Discourse_analysis(2)

Discourse analysis (DA), or discourse studies, is a general term for a number of approaches to analyzing written, spoken, signed language use or any significant semiotic event.The objects of discourse analysis—discourse, writing, talk, conversation, communicative event, etc.—are variously defined in terms of coherent sequences of sentences, propositions, speech acts or turns-at-talk. Contrary to much of traditional linguistics, discourse analysts not only study language use 'beyond the sentence boundary', but also prefer to analyze 'naturally occurring' language use, and not invented examples. This is known as corpus linguistics; text linguistics is related. The essential difference between discourse analysis and text linguistics is that it aims at revealing socio-psychological characteristics of a person/persons rather than text structure[1].Discourse analysis has been taken up in a variety of social science disciplines, including linguistics, sociology, anthropology, social work, cognitive psychology, social psychology, international relations, human geography, communication studies and translation studies, each of which is subject to its own assumptions, dimensions of analysis, and methodologies. Sociologist Harold Garfinkel was another influence on the discipline: see below.HistorySome scholars consider the Austrian emigre Leo Spitzer's Stilstudien [Style Studies] of 1928 the earliest example of discourse analysis (DA); Michel Foucault himself translated it into French. But the term first came into general use following the publication of a series of papers by Zellig Harris beginning in 1952 and reporting on work from which he developed transformational grammar in the late 1930s. Formal equivalence relations among the sentences of a coherent discourse are made explicit by using sentence transformations to put the text in a canonical form. Words and sentences with equivalent information then appear in the same column of an array. This work progressed over the next four decades (see references) into a science of sublanguage analysis (Kittredge & Lehrberger 1982), culminating in a demonstration of the informational structures in texts of a sublanguage of science, that of immunology, (Harris et al. 1989) and a fully articulated theory of linguistic informational content (Harris 1991). During this time, however, most linguists decided a succession of elaborate theories of sentence-level syntax and semantics.Although Harris had mentioned the analysis of whole discourses, he had not worked out a comprehensive model, as of January, 1952. A linguist working for the American Bible Society, James A. Lauriault/Loriot, needed to find answers to some fundamental errors in translating Quechua, in the Cuzco area of Peru. He took Harris's idea, recorded all of the legends and, after going over the meaning and placement of each word with a native speaker of Quechua, was able to form logical, mathematical rules that transcended the simple sentence structure. He then applied the process to another language of Eastern Peru, Shipibo. He taught the theory in Norman, Oklahoma, in the summers of 1956 and 1957 and entered the University of Pennsylvania in the inte rim year. He tried to publish a paper Shipibo Paragraph Structure, but it was delayed until 1970 (Loriot & Hollenbach 1970). In the meantime, Dr. Kenneth Lee Pike, a professor at University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, taught the theory, and one of his students, Robert E. Longacre, was able to disseminate it in a dissertation.Harris's methodology was developed into a system for the computer-aided analysis of natural language by a team led by Naomi Sager at NYU, which has been applied to a number of sublanguage domains, most notably to medical informatics. The software for the Medical Language Processor is publicly available on SourceForge.In the late 1960s and 1970s, and without reference to this prior work, a variety of other approaches to a new cross-discipline of DA began to develop in most of the humanities and social sciences concurrently with, and related to, other disciplines, such as semiotics, psycholinguistics, sociolinguistics, and pragmatics. Many of these approaches, especially those influenced by thesocial sciences, favor a more dynamic study of oral talk-in-interaction.Mention must also be made of the term "Conversational analysis", which was influenced by the Sociologist Harold Garfinkel who is the founder of Ethnomethodology.In Europe, Michel Foucault became one of the key theorists of the subject, especially of discourse, and wrote The Archaeology of Knowledge on the subject.[edit] T opics of interestTopics of discourse analysis include:∙The various levels or dimensions of discourse, such as sounds (intonation, etc.), gestures, syntax, the lexicon, style, rhetoric, meanings, speech acts, moves, strategies, turns and other aspects of interaction∙Genres of discourse (various types of discourse in politics, the media, education, science, business, etc.)∙The relations between discourse and the emergence of syntactic structure∙The relations between text (discourse) and context∙The relations between discourse and power∙The relations between discourse and interaction∙The relations between discourse and cognition and memory[edit] PerspectivesThe following are some of the specific theoretical perspectives and analytical approaches used in linguistic discourse analysis:∙Emergent grammar∙Text grammar (or 'discourse grammar')∙Cohesion and relevance theory∙Functional grammar∙Rhetoric∙Stylistics (linguistics)∙Interactional sociolinguistics∙Ethnography of communication∙Pragmatics, particularly speech act theory∙Conversation analysis∙V ariation analysis∙Applied linguistics∙Cognitive psychology, often under the label discourse processing, studying the production and comprehension of discourse.∙Discursive psychology∙Response based therapy (counselling)∙Critical discourse analysis∙Sublanguage analysisAlthough these approaches emphasize different aspects of language use, they all view language as social interaction, and are concerned with the social contexts in which discourse is embedded. Often a distinction is made between 'local' structures of discourse (such as relations among sentences, propositions, and turns) and 'global' structures, such as overall topics and the schematic organization of discourses and conversations. For instance, many types of discourse begin with some kind of global 'summary', in titles, headlines, leads, abstracts, and so on.A problem for the discourse analyst is to decide when a particular feature is relevant to thespecification is required. Are there general principles which will determine the relevance or nature of the specification.[2][edit] Prominent discourse analystsMarc Angenot, Robert de Beaugrande, Jan Blommaert, Adriana Bolivar, Carmen Rosa Caldas-Coulthard, Robyn Carston, Wallace Chafe, Paul Chilton, Guy Cook, Malcolm Coulthard, James Deese, Paul Drew, Alessandro Duranti, Brenton D. Faber, Norman Fairclough, Michel Foucault, Roger Fowler, James Paul Gee, Talmy Givón, Charles Goodwin, Art Graesser, Michael Halliday, Zellig Harris, John Heritage, Janet Holmes, Paul Hopper, Gail Jefferson, Barbara Johnstone, Walter Kintsch, Richard Kittredge, Adam Jaworski, William Labov, George Lakoff, Stephen H. Levinson, James A. Lauriault/Loriot, Robert E. Longacre, Jim Martin, David Nunan, Elinor Ochs, Jonathan Potter, Edward Robinson, Nikolas Rose, Harvey Sacks, Svenka Savic Naomi Sager, Emanuel Schegloff, Deborah Schiffrin, Michael Schober, Stef Slembrouck, Michael Stubbs, John Swales, Deborah Tannen, Sandra Thompson, Teun A. van Dijk, Theo van Leeuwen, Jef V erschueren, Henry Widdowson, Carla Willig, Deirdre Wilson, Ruth Wodak, Margaret Wetherell, Ernesto Laclau, Chantal Mouffe, Judith M. De Guzman, Cynthia Hardy, Louise J. Phillips[edit] Further reading1.^Y atsko V.A. Integrational discourse analysis conception2.^ Gillian Brown "discourse Analysis"∙Blommaert, J. (2005). Discourse. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.∙Brown, G., and George Yule (1983). Discourse Analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.∙Carter, R. (1997). Investigating English Discourse. London: Routledge.∙Gee, J. P. (2005). An Introduction to Discourse Analysis: Theory and Method. London: Routledge.∙Deese, James. Thought into Speech: The Psychology og a Language.Century Psychology Series. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 1984.∙Harris, Zellig S. (1952a). "Culture and Style in Extended Discourse". Selected Papers from the 29th International Congress of Americanists (New Y ork, 1949), vol.III: Indian Tribes of Aboriginal America ed. by Sol Tax & Melville J[oyce] Herskovits, 210-215. New Y ork:Cooper Square Publishers. (Repr., New Y ork: Cooper Press, 1967. Paper repr. in 1970a,pp. 373–389.) [Proposes a method for analyzing extended discourse, with example analyses from Hidatsa, a Siouan language spoken in North Dakota.]∙Harris, Zellig S. (1952b.) "Discourse Analysis". Language 28:1.1-30. (Repr. in The Structure of Language: Readings in the philosophy of language ed. by Jerry A[lan] Fodor & JerroldJ[acob] Katz, pp. 355–383. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1964, and also in Harris 1970a, pp. 313–348 as well as in 1981, pp. 107–142.) French translation "Analyse dudiscours". Langages (1969) 13.8-45. German translation by Peter Eisenberg, "Textanalyse".Beschreibungsmethoden des amerikanischen Strakturalismus ed. by Elisabeth Bense, Peter Eisenberg & Hartmut Haberland, 261-298. München: Max Hueber. [Presents a method for the analysis of connected speech or writing.]∙Harris, Zellig S. 1952c. "Discourse Analysis: A sample text". Language 28:4.474-494. (Repr.in 1970a, pp. 349–379.)∙Harris, Zellig S. (1954.) "Distributional Structure". Word 10:2/3.146-162. (Also in Linguistics Today: Published on the occasion of the Columbia University Bicentennial ed.by Andre Martinet & Uriel Weinreich, 26-42. New Y ork: Linguistic Circle of New Y ork,1954. Repr. in The Structure of Language: Readings in the philosophy of language ed. byJerry A[lan] Fodor & Jerrold J[acob] Katz, 33-49. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall,1964, and also in Harris 1970.775-794, and 1981.3-22.) French translation "La structure distributionnelle,". A nalyse distributionnelle et structurale ed. by Jean Dubois & Françoise Dubois-Charlier (=Langages, No.20), 14-34. Paris: Didier / Larousse.∙Harris, Zellig S. (1963.) Discourse Analysis Reprints. (= Papers on Formal Linguistics, 2.) The Hague: Mouton, 73 pp. [Combines Transformations and Discourse Analysis Papers 3a, 3b, and 3c. 1957, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania. ]∙Harris, Zellig S. (1968.) Mathematical Structures of Language. (=Interscience Tracts in Pure and Applied Mathematics, 21.) New Y ork: Interscience Publishers John Wiley & Sons).French translation Structures mathématiques du langage. Transl. by Catherine Fuchs.(=Monographies de Linguistique mathématique, 3.) Paris: Dunod, 248 pp.∙Harris, Zellig S. (1970.) Papers in Structural and Transformational Linguistics. Dordrecht/ Holland: D. Reidel., x, 850 pp. [Collection of 37 papers originally published 1940-1969.]∙Harris, Zellig S. (1981.) Papers on Syntax. Ed. by Henry Hiż. (=Synthese Language Library,14.) Dordrecht/Holland: D. Reidel, vii, 479 pp.]∙Harris, Zellig S. (1982.) "Discourse and Sublanguage". Sublanguage: Studies of language in restricted semantic domains ed. by Richard Kittredge & John Lehrberger, 231-236. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.∙Harris, Zellig S. (1985.) "On Grammars of Science". Linguistics and Philosophy: Essays in honor of Rulon S. Wells ed. by Adam Makkai & Alan K. Melby (=Current Issues inLinguistic Theory, 42), 139-148. Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins.∙Harris, Zellig S. (1988a) Language and Information. (=Bampton Lectures in America, 28.) New Y ork: Columbia University Press, ix, 120 pp.∙Harris, Zellig S. 1988b. (Together with Paul Mattick, Jr.) "Scientific Sublanguages and the Prospects for a Global Language of Science". Annals of the American Association ofPhilosophy and Social Sciences No.495.73-83.∙Harris, Zellig S. (1989.) (Together with Michael Gottfried, Thomas Ryckman, Paul Mattick, Jr., Anne Daladier, Tzvee N. Harris & Suzanna Harris.) The Form of Information in Science: Analysis of an immunology sublanguage. Preface by Hilary Putnam. (=Boston Studies in the Philosophy of, Science, 104.) Dordrecht/Holland & Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers, xvii, 590 pp.∙Harris, Zellig S. (1991.) A Theory of Language and Information: A mathematical approach.Oxford & New Y ork: Clarendon Press, xii, 428 pp.; illustr.∙Jaworski, A. and Coupland, N. (eds). (1999). The Discourse Reader. London: Routledge.∙Johnstone, B. (2002). Discourse analysis. Oxford: Blackwell.∙Kittredge, Richard & John Lehrberger. (1982.) Sublanguage: Studies of language in restricted semantic domains. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.∙Loriot, James and Barbara E. Hollenbach. 1970. "Shipibo paragraph structure." Foundations of Language 6: 43-66. The seminal work reported as having been admitted by Longacre and Pike. See link below from Longacre's student Daniel L. Everett.∙Longacre, R.E. (1996). The grammar of discourse. New Y ork: Plenum Press.∙Miscoiu, S., Craciun O., Colopelnic, N. (2008). Radicalism, Populism, Interventionism.Three Approaches Based on Discourse Theory. Cluj-Napoca: Efes.∙Renkema, J. (2004). Introduction to discourse studies. Amsterdam: Benjamins.∙Sager, Naomi & Ngô Thanh Nhàn. (2002.) "The computability of strings, transformations, and sublanguage". The Legacy of Zellig Harris: Language and information into the 21st Century, V ol. 2: Computability of language and computer applications, ed. by Bruce Nevin, John Benjamins, pp. 79–120.∙Schiffrin, D., Deborah Tannen, & Hamilton, H. E. (eds.). (2001). Handbook of Discourse Analysis. Oxford: Blackwell.∙Stubbs, M. (1983). Discourse Analysis: The sociolinguistic analysis of natural language.Oxford: Blackwell∙Teun A. van Dijk, (ed). (1997). Discourse Studies. 2 vols. London: Sage.Potter, J, Wetherall, M. (1987). Discourse and Social Psychology: Beyond attitudes and behaviour. London: SAGE.[edit]。

语篇层翻译transIation on discourse level

语篇层翻译translation on discourse level是以语篇为翻译单位,最大限度地寻求(相同语境下)原语语篇与译语语篇在意义和功能上的对等。

语篇是最大的语言单位,是在交际功能上相对完整的、独立的一个语言片段。

正如一个词在句子中才能确定其准确意义一样.一个句子(单个句子组成的语篇除外)只有出现在语篇中才能显示其确定、完整的含义,充分发挥其交际功能。

例如,对于However,this is not true.这个不可能单独出现的句子,如果脱离语篇背景,孤立地对它进行分析是很难准确地反映其能指和所指的意义的。

也就是说,在实际运用中,语言的基本单位不是通常所说的短语或句子,而应是语篇。

可见,在翻译中采用语篇翻译方法有利于更好地抓住原文的中心思想和总的基调,使译文中心突出、层次分明、内容衔接联贯。

特别是诗歌、广告词等文体材料的翻译,以语篇为翻译单位,从语篇上对韵律、对仗等修辞方式以及传达神韵、风格上作通盘考虑。

为了求得或保持译文篇章的衔接与连贯,有人把译者翻译时的篇章意识理解为“语篇层翻译”,例如:为了逃避那一双双熟悉的眼睛,释放后,经人介绍,他来到湖南南县一家木器厂做临时工。

In order to avoid those familiar eyes, he didn't return to his hometown after release,but found an odd job in a furniture factory in Nanxian County,Hunan Province through introduction.从上下文可知,湖南南县并非他的家乡,因此可“逃避那一双双熟悉的眼睛”。

下文又提到他“回乡”。

为使译文语义连贯,畅晓明白,宜加上he didn't return to his hometown,以使读者不感唐突。

这里,汉语原文的语义连贯转向译语的形式衔接。

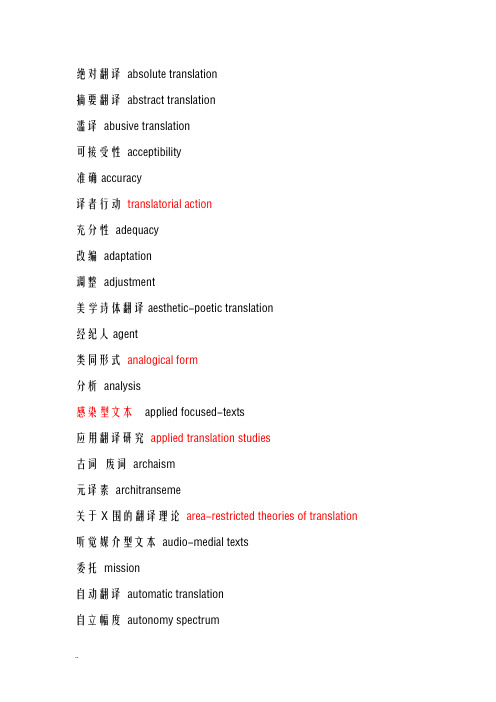

翻译硕士名词解释词条

绝对翻译absolute translation摘要翻译abstract translation滥译abusive translation可接受性acceptibility准确accuracy译者行动translatorial action充分性adequacy改编adaptation调整adjustment美学诗体翻译aesthetic-poetic translation经纪人agent类同形式analogical form分析analysis感染型文本applied focused-texts应用翻译研究applied translation studies古词废词archaism元译素architranseme关于X围的翻译理论area-restricted theories of translation 听觉媒介型文本audio-medial texts委托mission自动翻译automatic translation自立幅度autonomy spectrum自译autotranslation逆转换back-transformation关于X围的翻译理论back-translation 双边传译bilateral interpreting双语语料库bilingual corporal双文本bi-text空位blank spaces无韵体翻译blank verse translation借用borrowing仿造calque机助翻译MATX畴转换category shift词类转换class shift贴近翻译close translation连贯coherence委托mission传意负荷munication load传意翻译municative translation社群传译munity interpreting对换mutation可比语料库parable corpora补偿pensation能力petence成分分析ponential analysis机器辅助翻译MAT一致性concordance会议传译conference interpreting接续传译consecutive interpreting建构性翻译常规constitutive translational conventions 派生内容的形式content-derivative form重内容文本content-focused texts语境一致contextual consistency受控语言controlled language常规conventions语料库corpora可修正性correctability对应correspondence法庭传译court interpreting隐型翻译covert translation跨时翻译理论cross-temporal theories of translation 文化途径cultural approach文化借用cultural borrowing文化替换cultural substitution文化翻译cultural translation文化移植cultural transplantation文化置换cultural transposition区分度degree of differentiation翻译定义definitions of translation描写翻译研究descriptive translation studies图表翻译diagrammatic translation对话传译dialogue interpreting说教忠信didactic fidelity直接翻译direct translation翻译方向direction of translation消解歧义disambiguation关于话语类型的翻译理论discourse type-restricted theories of translation文献型翻译documentary translation归化翻译domesticating translation配音dubbing动态性dynamics动态对等dynamic equivalence动态忠信dynamic fidelity用功模式effort models借用borrowing种族学翻译enthnographic translation翻译的种族语言学模式enthnolinguistic model of translation 非目标接受者excluded receiver诠释性翻译exegetic translation诠释忠信exegetical fidelity异国情调exoticism期望规X expectancy norms明示explicitation表情型文本expressive texts外部转移external transfer外来形式extraneous form忠实faithfulness假朋友false friends假翻译fictitious translation贴近coherence异化翻译foreignizing translation派生形式的形式form-derivative forms重形式文本content-focused texts形式对应formal correspondence形式对等formal equivalence前向转换forward transformation自由译free translation全文翻译total translation功能取向翻译研究function-oriented translation studies 功能对等function equivalence空隙gaps宽泛化generalization宽泛化翻译generalizing translation要旨翻译gist translation释词翻译gloss translation成功success目的语goal languages语法分析grammatical analysis语法置换grammatical transposition字形翻译graphological translation诠释步骤hermeneutic motion对应层级hierarchy of correspondences历史忠信historical fidelity同音翻译homophonic translation音素翻译phonemic translation横向翻译horizontal translation超额信息hyperinformation同一性identity地道翻译idomatic translation地道性idomaticity不确定性indeterminacy间接翻译indirect translation翻译即产业过程translation as industrial process 信息负荷information load信息提供information offer信息型文本informative texts初始规Xinitial norms工具型翻译instrumental translation整合翻译integral translation跨文化合作intercultural cooperation中间语言interlanguage隔行翻译interlineal translation逐行翻译interlinear translation语际语言interlingua语际翻译interlingual translation中介翻译intermediate translation内部转移internal transfer解释interpretation传译interpreting翻译释意理论interpretive theory of translation 符际翻译intersemiotic translation互时翻译intertemporal translation语内翻译intralingual translation系统内转换intra-system shift不变量invariant不变性invariance逆向翻译inverse translation隐形invisibility核心kernel关键词翻译keyword translation贴近coherence可核实性verifiability可修正性correctability空缺voids层次转换level shift词汇翻译lexical translation联络传译liaison interpreting普遍语言lingua universalis语言学途径linguistic approach语言对等linguistic equivalence语言翻译linguistic translation语言创造性翻译linguistically creative translation 字面翻译literal translation直译法literalism借译load translation原素logeme逻各斯logos低地国家学派low countries groups 忠诚loyalty机助翻译MAT机器翻译machine translation操纵manipulation操纵学派manipulation school图谱mapping矩阵规X matricial norms中继翻译mediated translation中介语言mediating language词译metaphrase元诗metapoem元文本metatext韵律翻译metrical translation模仿形式mimetic form最小最大原则minimax principle小众化minoritizing translation调整modification调适modulation语义消歧semantic disambiguation多语语料库multilingual corpora多媒介型文本multi-medial texts多阶段翻译multiple-stage texts变异mutation自然性naturalness必要区分度necessary degree of differentiation 负面转换negative shift无遗留原则no leftover principle规X norms必要对等语obligatory equivalents曲径翻译oblique translation观察型接受者observational receiver信息提供information offer操作模式operational models操作规X operational norms运作型文本operative texts可换对等语optional equivalents有机形式organic form重合翻译overlapping translation显型翻译overt translationX式对等paradigmatic equivalence平行语料库parallel corpora释词paraphrase局部翻译理论partial theories of translation部分重合翻译partially-overlapping translation参与型接受者particularizing receiver具体化翻译particularizing translation赞助patronage运用performance音素翻译phonemic translation音位翻译phonological translation中枢语言pivot language译诗为文poetry into prose争辩式翻译polemical translation多元系统理论polysystem theory译后编辑post-editing译前编辑pre-editing语用途径pragmatic approach精确度degree of precision预先规X preliminary norms规定翻译研究prescriptive theories of translation首级翻译primary translation关于问题的翻译理论problem-restrained theories of translation成品取向翻译研究product-oriented studies of translation 过程取向翻译研究process-oriented studies of translation 专业规X professional norms散文翻译prose translation前瞻式翻译prospective translation抗议protest原型文本prototext伪翻译psedotranslation公共服务传译public service interpreting纯语言pure language原始翻译radical translation级阶受限翻译rank-bound translation关于级阶的翻译理论rank-restricted theories of translation 读者取向机器翻译reader-oriented machine translation独有特征realia接受语receptor language重构式翻译translation with reconstructions冗余redundancy折射refraction规约性翻译常规regulative translational conventions转接传译relay interpreting知识库要素repertoreme变换措词rephrasing阻抗resistancy受限翻译restricted translation重组restructuring转译retranslation后瞻式翻译retrospective translation换词rewording换声revoicing重写rewrtiting韵体翻译rhymed translation翻译科学science of translation目的论scopos theory二级翻译second-hand translation二手翻译secondary translation选译selective translation自译self translation语义消歧semantic disambiguation语义翻译semantic translation语义空缺semantic voids意义理论theory of sense意对意翻译sense-for-sense translation 序列翻译serial translation服务翻译service translation转换shifts视译sight translation手语传译signed language translation同声传译simultaneous interpreting源语source language源文本source text源文本取向翻译研究source text-oriented translation studies 具体化specification结构转换structure shift文体对等stylistic equivalence子语言sublanguage配字幕substituting成功success超额翻译overtranslation组合对等syntagmatic equivalence系统system有声思维记录think-aloud protocols目标语target language目标文本target texts目标文本取向翻译研究target text-oriented translation studies 术语库term banks术语terminology文本类型学text typology文本素texteme关于文本类型的翻译理论text type-restricted theories of translation 文本对等textual equivalence文本规X textual norms理论翻译研究theoretical translation studies意义理论theory of sense增量翻译thick translation有声思维记录think aloud protocols第三语码third code第三语言third language关于时域的翻译理论temporal-restricted theories of translation完全翻译total translation巴别塔tower of babel注音transcription译素transeme转移transfer转移取向翻译研究transfer-oriented translation studies迁移transference转换transformation可译性translatability笔译translation翻译与博弈理论translation and the theory of games 翻译即抉择translation as decision-making翻译即产业过程translation as industrial process翻译对等translation equivalence翻译研究translation studies翻译理论translation theory翻译单位translation unit翻译普遍特征translation universals重构式翻译translation with reconstructions翻译对等translation equivalence翻译体translationese翻译学translatology译者行动translatorial action音译transliteration符际转化transmutation置换transposition不受限翻译unbounded translation欠额翻译undertranslation翻译单位translation unit单位转换unit shift不可译性untranslatability词语一致verbal consistency可核实性correctability改本改译version纵向翻译vertical translation空缺voids耳语传译whispered interpreting词对词翻译word- for-word translation作者取向翻译机器reader-oriented machine translation。

Chapter One An Introduction to PragmaticsPPT教学课件

2020/12/09

5

Chapter One Introduction to pragmatics

1.1 The origin and development of pragmatics

1.2 Definitions of pragmatics 1.3 Focus of pragmatics 1.4 Criticisms of pragmatics

He ignores the use of language and the communicative function of language.

2020/12/09

11

In 1950, he discovered Syntax. Like the structuralists, he focused his study on language form, still regarded meaning as too messy for serious contemplation.

2020/12/09

7

The term “pragmatics” is attributed to the philosopher Charles Morris (1938) who was concerned to outline the general shape of a science of signs or semiotics as Morris

one part of semiotics, studying the origin of signs, the usage and the function of signs in behaviour.

The development of pragmatics owes much to the heated dispute over Chomsky’s view of language.

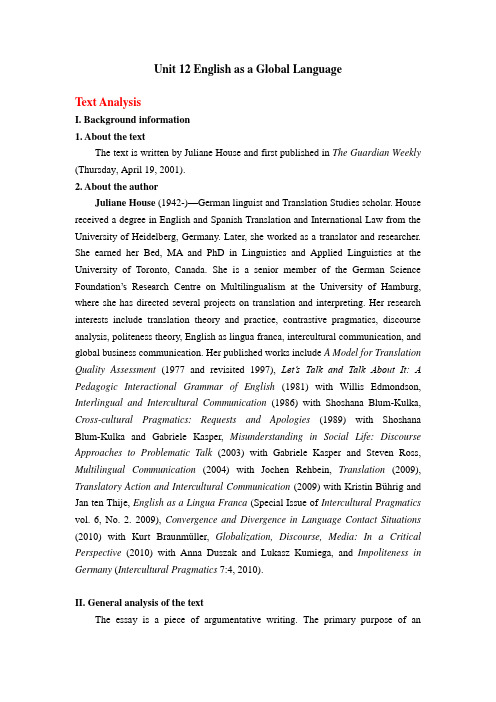

翻译研究之2:跨文化交际—翻译理论与对比篇章语言学(Basil Hatim)

COMMUNICATION ACROSS CULTURES Translation Theory and Contrastive Text Linguistics跨文化交际----翻译理论与对比篇章语言学Basil Hatim出版前言这是一部将对比语言学、篇章语言学和翻译理论结合起来研究跨文化交际的学术专著。

作者巴兹尔•哈蒂姆是英国爱丁堡赫利奥特----沃特(Heriot-Watt)大学阿拉伯语研究中心主任,篇章语言学界的权威人士、著名理论家,一直走在该研究领域的前列。

本书是他长达10年的科研成果。

针对目前翻译理论、对比语言学、话语分析三个学科自成一体的学术局面,作者试图将三者融会贯通,明确提出在跨语言、跨文化的交际过程中,如果将母语语言、修辞的习惯表达应用与篇章转化,比如翻译实践当中,并在另一语言体系寻求对应表现法,其结果将是大有裨益的。

本专著共分17章。

全书说理透彻,脉络清晰。

首先,作者简单介绍了对比语言理论应用于翻译过程的可行性,即句法与语义性质等语言结构的重要意义,指出文本类型是进行上下文分析研究的中心课题,篇章才是有效信息交流的根本单位;进而,作者从功能语言学的角度,对修辞、文本风格、语域等因素进行了深入讨论。

由于阿拉伯语具有悠久独特的修辞风格,作者通过现在篇章语言学以及传统的阿拉伯语修辞学在语言研究分析中的有利地位,对篇章类型提出了自己的见解。

除此以外,作者还就文本类型、礼貌表达、交际文化、文学作品中的意识形态的分析与翻译、非小说类的散文文学中反语用法的翻译以及口译研究等问题从对比篇章语言学的角度进行了系统化的分析探讨。

本书贯穿书中的指导思想,就是将语篇分析的理论模型应用于笔译、口译及语言教学实践之中,并通过这些目标在实际中的结合来证明翻译的介绍可以加大对比语言学和语篇分析研究的广度和深度。

总之,本书论述系统全面,资料翔实,从理论到实践环环相扣,是一部侧重语言实际运用的学术著作,对于从事语言学、文学理论、话语分析、翻译以及文化等学科研究的人员提供了建设性的知道,是一本不可多得的好书。

西方翻译理论简介2

Friedrich Schleiermacher's "On Different Methods of Translating" ---"the major document of romantic translation theory, and one of the major documents of Western translation theory in general". Schleiermacher distinguished between the "interpreter (Dolmetscher) who works in the world of commerce", and the "translator proper (Ubersetzer) who works in the fields of scholarship and art".

高级英语2翻译及paraphrase(2)

TranslationUnit 11. However intricate the ways in which animals communicate with each other, they do not indulge in anything that deserves the name of conversation.不管动物之间的交流方式多么复杂,它们不能参与到称得上是交谈的任何活动中。

2. Argument may often be a part of it, but the purpose of the argument is not to convince. There is no winning in conversation.争论会经常出现于交谈中,但争论的目的不是为了说服。

交谈中没有胜负之说。

3. Perhaps it is because of my upbringing in English pubs that I think bar conversation has a charm of its own.或许我从小就混迹于英国酒吧缘故,我认为酒吧里的闲聊别有韵味。

4. I do not remember what made one of our companions say it ---she clearly had not come into the bar to say it, it was not something that was pressing on her mind---but her remark fell quite naturally into the talk.我不记得是什么使得我的一个同伴说起它来的---她显然不是来酒吧说这个的,这不是她事先想好的话题----但她的话相当自然地插入到了交谈中。

5. There is always resistance in the lower classes to any attempt by an upper class to lay down rules for “English as it should be spoken.”下层社会总会抵制上层社会企图给“标准英语”制定得规则。

语篇与译者

八音魔琴PPT教程系列

-10-

The emergence of linguistics as a new discipline in the twentieth century brought a spirit of optimism to the pursuit of language study ,a feeling that the groundwork was at last being laid for a systematic and scientific approach to the description of language. Perhaps provide solutions to the kinds of language problems one obvious application of linguistics: develop a device for carrying out automatic translation

Discourse and the Translator(written in collaboration with Ian Mason) Communication across Cultures :Translation theory and Contrastive text

《跨文化交际-翻译理论与对比篇章语言学》 Ian Mason is a Professor of Interpreting and Translating at Heriot-Watt University. Among his publications is the Discourse and the Translator,written in collaboration with Basil Hatim Another Book:Dialogue Interpreting

篇章翻译

Definition of Text

From the aspect of structure: text is a unit of language above the unit ranging from morpheme, word, phrase, clause, sentence to paragraph. E.g., “Exit”, “Help!”, etc. A text may be anything from a simple greeting to a whole play, from a momentary cry for help to an all-day discussion on a committee.

翻译类型

当时,比较有名的有 Otto Kade(1964),他研究的 是实用性文本的翻译,Rudolf W. Jumpelt(1961) 研究的是科技翻译,Eugene A. Nida(1964)研究 的是《圣经》翻译,Rolf Kloepfer(1967)研究的是 文学——散文和诗歌的翻译,Ralph Wuthenow( 1969)研究的是古代文献的翻译。莱斯经过对他们的 作品和翻译理论进行认真研究后发现,他们的共同缺点 是:把自己在某一方面研究所得出的结论推广到其它的 文本翻译当中去了,把它说成是唯一的、通用的翻译标 准。这是以偏代全,很不科学的。

Passage Translation

翻译单位

翻译单位的概念最早是Vinay & Darbelnet(1958)提 出的,他们认为翻译单位与思维单位、词汇单位同义,是 在翻译过程中关系紧密、不可分割开进行翻译的最小言 语片段。

影响较大的是巴尔胡达罗夫对翻译单位作出的定义。 1985年,蔡毅等编译出版了巴尔胡达罗夫的《语言与 翻译》。

现代大学英语第二版精读1课文翻译Lesson twelve