【极客出品】制 品 使 用 状 况 调 查 书

academic3

Journal of International Economic Law11(2),263–311doi:10.1093/jiel/jgn010.Advance Access publication26February2008EAST ASIAN FREE TRADE AGREEMENTS IN SERVICES:KEY ARCHITECTURAL ELEMENTS Carsten Fink*and Martı´n Molinuevo**ABSTRACTSince the mid-1990s East Asian countries have negotiated25free trade agreements(FTAs)with a services component.There are important archi-tectural differences in these agreements,which ultimately affect their value in promoting transparency,fostering the credibility of trade policies,and advancing market opening in services.This article reviews key architectural choices,focusing on the approach towards scheduling commitments,the treatment of investment and the movement of natural persons,rules of origin,provisions for the settlement of trade dispute,and selected deeper integration issues.In doing so,it assesses the advantages and drawbacks of different architectural approaches and discusses a number of lessons learned. INTRODUCTIONBilateral and regional free trade agreements(FTAs)are proliferating at an unprecedented pace.Most of the recently negotiated agreements are comprehensive in their coverage and extend their market opening ambition to international commerce in services.This trend is powered by underlying economic forces,such as technological progress which has expanded the scope for trading services internationally and increased private sector partici-pation in the provision of infrastructure services considered public mono-polies not too long ago.Have services FTAs actually served those economic forces?In particular, have they led to liberalization undertakings that go beyond those to which countries are committed under the WTO’s General Agreement on Trade in Services(GATS)?Have they established stronger disciplines than the *Senior Economist at the World Bank Institute.E-mail:cfink_de@yahoo.de**Martı´n Molinuevo is a Research Fellow at the World Trade Institute and a Consultant to the World Bank.E-mail:martin.molinuevo@.This article is an output of a research project undertaken by the World Bank’s Poverty Reduction and Economic Management Department for East Asia.The authors are grateful to Rolf Adlung,Nasser Al Zubi,Daniel Crosby,Panos Delimatsis,Felipe Hees,Christoph Ko¨nig,Juan Marchetti,Se´bastien Miroudot,Christian Pauletto,Sebastia´n Sa´ez,Constantinos Stephanou,Carlos Gimeno Verdejo,and Mahani Zainal-Abidin for helpful comments and suggestions.The views expressed in this article are the authors’own and do not necessarily represent those of their respective institutions. Journal of International Economic Law V ol.11No.2ßOxford University Press2008,all rights reserved264Journal of International Economic Law(JIEL)11(2)GATS?Few studies exist to answer these questions.1This article seeks to answer the latter question by offering a review of key architectural elements of East Asian FTAs in services.2In another paper,we assess the liberaliza-tion content of these agreements and their compliance with WTO rules on regional integration.3The East Asia region offers an instructive case study of services FTAs. Figure1shows all25agreements that had been signed as of January2007. Twenty-four of those agreements were negotiated in this decade.Only the ASEAN-Framework Agreement on Trade in Services(AFAS)dates back to the mid-1990s.East Asian FTAs offer a wide variety in architectural approaches,with some being closely modeled on the GATS and others following the structure of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA).In fact,the agreements concluded by East Asian countries offer an insightful window into global negotiating trends.The Singapore–US FTA, for instance,serves as a proxy for the FTA model promoted by the US in different regions of the world.Other NAFTA-inspired agreements in East Asia mirror the approaches adopted by many countries in the Western Hemisphere—including Canada,Chile,and Mexico.The region’s GATS-inspired agreements,in turn,show many commonalities with EU FTAs and the Mercosur services accord.Uniquely,a number of East Asian 1For a review some of the key architectural innovations of services FTAs,see OECD,‘The Relationship between Regional Trade Agreements and the Multilateral Trading System: Services’,Working Party of the Trade Committee,OECD document TD/TC/WP(2002)27/ FINAL,2002;and Sauve´Pierre,‘Adding Value at the Periphery:Elements of GATSþRegional Agreements in Services’,Paper prepared for the seminar Eyes Wide Shut?Beyond Market Access in North-South Regional Trade Arrangements,International Development Research Center,Ottawa2005.Stephenson Sherry,‘Examining APEC’s Progress towards Reaching the Bogor Goals for Services Liberalization’,Draft paper prepared for Pacific Economic Cooperation Council,2005.Available online at /content/apec/ documents_reports/committee_trade_investment/2006.html,visited September2006)and Roy et al.,Services Liberalization in the New Generation of Preferential Trade Agreements(PTAs):How Much Further than the GATS?,WTO Staff Working Paper No.ERSD-2006-07(Geneva:World Trade Organization,2006)evaluate the liberalization content of selected bilateral and regional agreements.On the negotiating experiences of countries in Latin America and the Caribbean, see Stephenson Sherry(ed.)Services Trade in the W estern Hemisphere:Liberalization,Integration, and Reform.(Washington,DC:Organization of American States and Brookings Institution Press,2000);Sa´ez Sebastia´n,Trade in Services Negotiations:A Review of the Experience of the United States and the European Union in Latin America.SERIE Comercio Internacional,no.76, (Santiago,Chile:United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean,2005);Marconini Mario,Services in Regional Agreements between Latin American and Developed Countries.SERIE Comercio Internacional,no.71(Santiago,Chile:United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean,2006),and Pereira Goncalves et al.,Financial Services and Trade Agreements in Latin America and the Caribbean: an Overview,Policy Research Working Paper No.4181(Washington,DC:The World Bank,2007).2For the purposes of this article,we adopt the World Bank’s classification of East Asia,which encompasses countries in both Eastern Asia and Southeast Asia,as classified by the United Nations.3Fink Carsten and Molinuevo Martı´n,East Asian FTAs in Services:Liberalization Content and WTO rules,Mimeo,2007.East Asian Free Trade Agreements in Services265Figure1.East Asian FTAs with a services component.FTAs—notably the Trans-Pacific EPA and the Australia–Singapore FTA—have combined elements of different models,setting new standards which, in future,may be adopted by countries outside the region.Ultimately,trade agreements seek to promote international commerce. They can do so in three ways:by reducing barriers to foreign participation, by making trade policies more transparent,and by enhancing the credibility of the trade regime—the latter being defined as reducing the risk of policy becoming more restrictive.Architectural choices can make an important difference in this respect.In comparing the different approaches found in East Asia,we specifically seek to evaluate to what extent agreements promote trade along these three dimensions.266Journal of International Economic Law(JIEL)11(2)Due to space constraints,we cannot review all architectural elements of services FTAs,but rather focus on selected key elements that have not been discussed extensively in the previous literature and for which there is significant variation in East Asian agreements.In particular,our review starts with the scheduling approach adopted by FTAs(Section I)—one of the key distinguishing characteristics of trade agreements in services.We then consider the treatment of investment in services(Section II),the treatment of labor mobility(Section III),the rules of origin adopted(Section IV),and provisions for the settlement of trade disputes(Section V).In Section VI, we discuss to what extent East Asian FTAs have gone beyond the GATS on a number of deeper integration issues—notably recognition of professional qualifications,domestic regulation,and trade rules on government procure-ment,subsidies and emergency safeguards.In the conclusion(Section VII), we briefly discuss several lessons learned.I.SCHEDULING APPROACHNo services FTA has established immediate free trade in all service sectors.4 The East Asian FTAs make no exception in this regard.For a variety of reasons,governments wish to exempt certain activities from the coverage of trade disciplines or maintain certain trade-restrictive measures.A critical question in the design of an FTA is how these exemptions and limitations are inscribed into an agreement.As a first step,most FTAs allow for sectoral carve-outs that exempt one or more activities from the scope of the agreement.Activities falling under such an exemption are not subject to any of the disciplines established in the agreement.The most frequently encountered carve-out pertains to air transport.Twenty FTAs exempt core air transport services related to the exercise of air traffic rights.5This exemption is also found in the GATS and is explained by the fact that the provision of these services has historically been negotiated through separate bilateral treaties.Four FTAs also carve out cabotage in maritime transport—a sector in which foreign participation is often deemed sensitive.More significantly,four FTAs fully exempt financial services from the scope of the agreement—an issue to which we will return later.64Throughout the article and unless other terms are employed,we use the term‘FTA’loosely to also include other types of trade agreements that seek the liberalization of trade in services—such as bilateral trade agreements(BTAs)or economic partnership agreements(EPAs). Similarly,we refer to‘countries’in a broad sense,so as to encompass any geographical entity with international personality and capable of conducting an independent foreign economic policy.5However,this exception usually does not apply to aircraft repair and maintenance services,the selling and marketing of air transport services,and computer reservation system services.6In addition to the sectoral carve-outs found in the services chapters of FTAs,investment chapters may also exclude certain activities from the scope of investment disciplines.For example,under the Japan–Mexico EPA,Mexico scheduled a list of activities reserved to theEast Asian Free Trade Agreements in Services267 Five FTAs do not provide for any carve-out of service activities,making all service sectors subject to the agreements’underlying provisions.7However, it does not automatically follow that all sectors are subject to liberalization undertakings.The liberalization content of FTAs is detailed in country-specific market-opening schedules.A variety of approaches exist in drawing up these schedules.Fundamentally,these approaches differ along two dimensions:(i)the listing of service activities subject to liberalization com-mitments and(ii)the listing of levels of openness.Lists can either be drawn up on a positive basis—identifying what is covered or allowed—or on a negative basis—identifying what is not covered or not allowed,though mixed approaches are also possible.T able1indicates the scheduling approaches adopted by the East Asian FTAs.In what follows,we first describe key features of these scheduling approaches.We then compare and assess these approaches,focusing on the three dimensions outlined above:incentives for liberalization,transparency, and credibility.A.Agreements with a positive list of sectorsFifteen East Asian FTAs have adopted a positive list of sectors in which trade commitments are undertaken(T able1).In other words,only the sectors that parties have expressly identified are subject to market opening undertakings. Countries are free to maintain or impose trade-restrictive measures in non-scheduled sectors,although those measures may still be subject to an agree-ment’s general disciplines(such as on transparency).Once a sector is scheduled,the next question is how to set the level of openness in that sector.Interestingly,this question is not relevant for one of the East Asian FTAs—the Lao PDR–US Bilateral Trade Agreement(BTA). Under this agreement,Laos is committed to unrestricted market access and national treatment in listed sectors.8However,the Lao PDR–US BTA should be considered a special case and,indeed,is unparalleled in its ambition.All other trade agreements in services allow parties not to immediately commit to free trade in sectors subject to liberalization undertakings.For the remaining14East Asian FTAs with a positive list of state—including telegraph services,postal services,and electricity distribution—and for which foreign entry may be refused.7Namely,the Lao PDR–US BTA,the Mainland–Hong Kong CEPA,the Mainland–Macao CEPA,the New Zealand–Singapore FTA,and the Vietnam–US BTA.8In principle,the agreement specifies that‘each party’is not allowed to maintain any restriction on market access in the listed sectors and on national treatment.However,the agreement also provides that the obligations of the US are subject to the market access and national treatment limitations scheduled by the US under the GATS(see Articles32and33of the Lao PDR–US BTA).In addition,market access and national treatment do not apply to the United States with respect to the financial services sector(see Article35of the agreement).sectors,we observe two approaches for specifying levels of openness:pure positive lists and GATS-style hybrid lists.1.Pure positive list agreementsUnder a pure positive list,parties to an agreement specify for each listed service sector the level (and type)of foreign participation that is allowed.Only two East Asian FTAs follow this approach:the Mainland–Hong Kong and the Mainland–Macao Closer Economic Partnership Agreements (CEPAs).Interestingly,these two agreements do not establish binding disciplines,such as the ones created by the GATS market access and national treatment provisions.They also do not define any modes of supply,as is done for all other trade agreements in services (see subsequently).In fact,the legal disciplines established by the agreements’services chapters are arguably the weakest among all the East Asian FTAs.Y et,China’s marketT able 1.Scheduling approachesAgreement(s)Listing of sectors Listing of level ofopennessLao PDR–US BTA Positive Not applicable,asno trade-restrictivemeasures arescheduledMainland–Hong Kong CEPA,Mainland–Macao CEPA Positive PositiveAFAS,ASEAN–China TISAgreement,Australia–Thailand FTA,India–Singapore ECA,Japan–Malaysia EPA,Japan–PhilippinesEPA,Japan–Singapore EPA,EFTA–Korea FTA,EFTA–SingaporeFTA,Jordan–Singapore FTA,New Zealand–Singapore FTA,Vietnam–US BTAPositive Hybrid Australia–Singapore FTA,Chile–Korea FTA,Guatemala–T aiwan (China)FTA,Japan–MexicoEPA,Panama–T aiwan (China)FTA,Trans-Pacific EPANegative Negative Nicaragua–T aiwan (China)FTA,Singapore–Panama FTA,Singapore–US FTANegative,except for cross border trade in financial services for which a positive list is adopted Negative Korea–Singapore FTA Negative,except for finan-cial services for which apositive list is adopted Negative,except for financial services for which a hybrid listis adopted268Journal of International Economic Law (JIEL)11(2)East Asian Free Trade Agreements in Services269 opening undertakings under the two CEPAs grant service providers from Hong Kong and Macao substantial trade preferences.92.GATS-style hybrid list agreementsUnder a GATS-style hybrid list,parties may define the level of openness in listed sectors either on a positive or negative list basis.In particular, agreements following this approach typically adopt the market access and national treatment provisions of the GATS.Schedules of commitments then specify the market access‘terms,limitations and conditions’and national treatment‘conditions and qualifications’.10In other words,countries are free to describe either how trade is restricted or what type of services transac-tions are allowed in a listed sector.As a rule of thumb,an entry in a GATS schedule that takes the form‘None,except...’signifies a negative list of trade-restrictive measures,whereas an entry that takes the form‘Unbound, except...’signifies a positive list of market-opening concessions.11One clarifying remark is in order.The GATS approach to the scheduling of commitments has frequently been referred to in the literature as a positive list approach.This terminology focuses solely on the selection of sectors subject to trade commitments.For the purposes of this article,we refer to GATS-style agreements as hybrid list agreements,because the fixing of the level of openness under this approach involves elements of both negative and positive listing.12We use the term positive list agreements to describe all agreements that adopt a positive list of sectors subject to trade commitments, encompassing the special case of the Lao PDR–US BTA,the pure positive list agreements,and the hybrid list agreements.Several features associated with the GATS-style hybrid list approach are worth pointing out.First,commitments in each listed sector are made with respect to four different modes of supply:cross-border trade(mode1), consumption abroad(mode2),commercial presence(mode3),and movement of natural persons(MNP)(mode4).13In actual GATS schedules,most entries 9See Fink Carsten,‘A Macroeconomic Perspective on China’s Liberalization of Trade in Services’,in Henry Gao and Donald Lewis(eds),China’s Participation in the WTO(London: Cameron May,2005).10See GATS Articles XVI.1and XVII.1.11A negative list of trade-restrictive measures also prevails,when a scheduling member does not explicitly indicate‘None,except...’,but inscribes one or more limitations applying to a listed sector.For further details on the scheduling of GATS commitments,see WTO document S/CSC/W/19.12Other studies have also characterized GATS-style agreements as hybrid list agreements.See Hoekman Bernard and Sauve´Pierre,Liberalizing Trade in Services,Discussion Paper No.243 (Washington,DC:The World Bank,1994);OECD,above n1;and UNCTAD,‘National Treatment’,UNCTAD Series on Issues in International Investment Agreements(New Y ork and Geneva:United Nations,1999).13For a more comprehensive discussion of modes of supply,see Adlung Rudolf and Mattoo Aaditya,‘The GATS’,in Aaditya Mattoo et al.(eds),A Handbook of International Trade in Services(Washington,DC:The World Bank and Oxford University Press,2008).270Journal of International Economic Law(JIEL)11(2)for modes1,2,and3set the level of openness on a negative list basis,whereas the great majority of entries for mode4are made on a positive list basis. Eleven,of the12East Asian hybrid list FTAs follow the structure of the GATS by distinguishing between four modes of supply and between market access and national treatment measures.The only exception is the Australia–Thailand FTA,whose schedule does not differentiate between modes of supply nor between market access and national treatment measures.T o which mode and to which measures a particular commitment applies is determined by the nature of the scheduled pared to the GATS,this scheduling approach appears to reduce difficulties in scheduling measures that may be inconsistent with both market access and national treatment obligations.14 Second,several GATS-style hybrid list agreements adopt a most-favored nation(MFN)obligation which is subject to the scheduling of reservations. However,MFN reservations are always inscribed on a negative list basis in relation to both service activities and trade restrictive measures.Interestingly, some hybrid list agreements have not incorporated binding MFN disciplines in their text.15MFN obligations in an FTA context have a different meaning than the multilateral MFN principle under the GATS.They mainly take two forms.On the one hand,regional trade agreements involving more than two countries may wish to establish an MFN obligation to ensure non-discriminatory treatment between service providers from countries within the region.In East Asia,this is the case for the ASEAN Framework Agreement on Services,which calls for preferential treatment to be accorded on an MFN basis.16On the other hand,some FTAs require non-discrimination between parties and non-parties.In other words,a non-party MFN clause guarantees FTA parties the best current and future treatment that the other party grants to services suppliers from any country.14The relationship between the GATS market access and national treatment disciplines has been subject to conflicting legal interpretations.See Mattoo Aaditya,‘National Treatment in the GATS:Corner-Stone or Pandora’s Box?’31(1)Journal of World Trade(1997),at 107–35;Pauwelyn Joost,‘Rien ne Va Plus?Distinguishing Domestic Regulation From Market Access in GATT and GATS’,4(2)World Trade Review(2005),at131–70;Delimatsis Panagiotis,‘Don’t Gamble with GATS—The Interaction Between Articles VI,XVI,XVII and XVIII in the Light of the US-Gambling Case’,40Journal of World Trade(2006),at 1059–80;and Molinuevo Martı´n,‘GATS Article XX—Schedules of Specific Commitments’, in R.Wolfrum et al.(eds),Max Planck GATS Commentary(Biggleswade,UK:Brill Publishers,forthcoming in October2008).15Namely,the ASEAN–China TIS,the Australia–Thailand FTA,the India–Singapore ECA,the Japan–Singapore EPA,the Jordan–Singapore FTA,and the New Zealand–Singapore FTA. 16However,a2003amendment to the AFAS allows for departure from MFN if two or more members agree to liberalize trade in services faster than the remaining ASEAN members.It is worth pointing out that an intra-regional MFN obligation may not be necessary for regional agreements involving WTO members,as FTA parties would already be bound by the MFN obligation under the GATS.It would only be needed if FTA parties wanted to eliminate at the regional level the application of MFN exemptions scheduled under the GATS or desired to make MFN subject to a regional dispute settlement mechanism.East Asian Free Trade Agreements in Services271 Third,GATS-style schedules allow for horizontal commitments.Measures scheduled in these horizontal commitments apply to all listed service sectors, unless the wording of a sectoral commitment unambiguously indicates other-wise.In assessing the level of openness of specific service sectors,it is therefore critical to take these horizontal commitments into account.Sometimes they can be far-reaching—for example,a joint venture requirement with foreign equity participation limited to49%,or an entry that limits the movement of individual service providers to specific types of intra-corporate transferees.In such cases, they effectively fix a low level of openness across all sectors.Fourth,GATS-style hybrid list agreements typically do not require signa-tories to make bindings at the level of actual openness.In fact,existing GATS commitments are often characterized as being less liberal than status quo policies—not least because substantial unilateral liberalization has taken place in many countries since the conclusion of the Uruguay Round of Trade Negotiations in1994.17A gap between bound and actual policies—a so-called binding overhang—may introduce uncertainty,because governments at any point can restrict foreign participation in their domestic service market,as long as they stay within their trade commitments.Most East Asian hybrid list FTAs similarly do not impose any requirement to bind at the actual level of openness. However,Japan’s Economic Partnership Agreements(EPAs)with Malaysia and the Philippines have introduced an innovation that serves to reduce the uncertainty associated with a binding overhang.18These agree-ments offer the possibility to identify in schedules those service sectors in which a party agrees to bind status quo policies.In addition,the identified service sectors are subject to upward ratcheting:once a party unilaterally eliminates a trade-restrictive measure,policy will automatically be bound at the more liberal level.19B.Negative list agreementsT en East Asian FTAs have adopted a negative list approach in scheduling their market opening commitments.Negative listing generally applies to both sectors and measures.In other words,trade is unrestricted across all covered service activities,unless scheduled limitations indicate otherwise.17For example,see Hoekman Bernard,‘Assessing the General Agreement on Trade in Services’,in Will Martin and L.Alan Winters(eds),The Uruguay Round and the Developing Countries(Cambridge:Cambridge University Press,1996).18For example,Article99.3of the Japan–Malaysia EPA provides that‘[w]ith respect to sectors or sub-sectors where the specific commitments are undertaken[...]and which are indicated with‘‘SS’’,any terms,limitations,conditions and qualifications[...]other than those based on measures pursuant to immigration laws and regulations,shall be limited to those based on non-conforming measures,which are in effect on the date of entry into force of this Agreement’.19Even though upward ratcheting enhances the credibility of unilateral trade reforms,it arguably implies a loss of transparency in committed policies,because parties are not required to notify these reforms or periodically update their schedules.272Journal of International Economic Law(JIEL)11(2)Again,it is useful to review several key features of negative list agreements. First,these agreements typically establish separate disciplines for cross-border trade and investment in services.Cross-border trade in services in the negative list model covers the GATS equivalent of modes1,2,and4, although commitments do not formally distinguish between these three modes of supply.The GATS equivalent of mode3is covered by a horizontal investment chapter that applies to both goods and services,though the typical investment disciplines go beyond those established by the GATS.20 Second,trade in financial services receives separate treatment in several of the negative list FTAs.Four agreements revert to a positive list for trade in financial services,either by adopting a positive list for cross border trade in financial services(modes1,2,and4)or by entirely following GATS-style hybrid lists(T able1).Furthermore,four of the remaining six negative list FTAs21carve out trade in financial services entirely from the scope of the agreement,leaving only the Australia–Singapore FTA and the Panama–T aiwan(China)FTA for which the negative list applies,in principle,to financial services.Third,negative list agreements establish additional classes of measures for the scheduling of specific commitments.T able2lists the obligations identi-fied by the10negative list FTAs in the three areas subject to trade commit-ments:cross-border trade in services,investment,and trade in financial services.A number of patterns are worth pointing out:All10negative list FTAs feature obligations on national treatment, subject to sectoral reservations.22Only six negative list FTAs feature a market access discipline mirroring GATS Article XVI.23Three of the remaining four agreements follow20Two negative list agreements in East Asia depart from this basic model.The Trans-Pacific EPA does not establish separate investment disciplines,but services supplied through commercial presence are covered under the agreement’s services disciplines—reverting to the structure of the GATS.Similarly,the Australia–Singapore FTA covers commercial presence in the services chapter,but in this case separate investment disciplines still apply.21Namely,the Guatemala–T aiwan(China)FTA,the Korea–Chile FTA,the Trans-Pacific EPA, and the Japan–Mexico EPA.The latter agreement features a chapter on financial services.However,provisions in that chapter merely ratify existing multilateral and plurilateral commitments,and carve out financial services from the services,investment and dispute settlement chapters of the agreement.22The language of the national treatment provision mostly follows the NAFTA standard of providing for national treatment for services and services suppliers‘in like circumstances’.The only exception is the Australia–Thailand FTA,which incorporates the‘like services and service suppliers’language found in GATS Article XVII.For a discussion of the‘likeness’standard under the GATS,see Cossy Mireille,Determining‘Likeness’under the GATS: Squaring the Circle?WTO Staff Working Paper ERSD-2006-8(Geneva:World Trade Organization,2006).23The catalog of measures covered by these agreements is the same as the one adopted by the GATS,with the exception that all six agreements except the Australia–Singapore FTA do not cover restrictions on foreign equity participation under market access.In the case of the Korea–Singapore FTA,market access does not apply to investment in services and the。

印刷物仕様书(一般印刷)

印刷物仕様書(一般印刷)

品名葛生伝承館封筒数量2000 単位枚規格

(仕上寸法)

長3

紙質ハーフトーンクリーム

ページ数()ページ(表紙込・表紙別)【表紙(片面刷・両面刷)、本文(片面刷・両面刷)】刷色表面:(2 )色刷(郵便番号欄のみ赤) 裏面:()色刷り・印刷なし

製本無線とじ針金(中とじ・平とじ)化粧断ち(天・横)のりその他()

原稿①データ支給:ワード・エクセル・パワーポイント・その他(画像データJpeg)】

②支給媒体:CD-R・FD・出力紙・その他()

③手書き:前回どおり前回を修正したもの(手書き・出力紙)

見本有・無

特

記

事

項

企画・デザイン等の依頼有・無

写真

発注課から提供()枚受注者に依頼()枚

支給:データ()枚プリント()枚

イラスト

発注課から提供(1)枚受注者に依頼()枚

支給:データ(1)枚その他()枚

その他:

校正文字校正( 1 )回色校正()回納入期限平成28年7月29日(金)

納入場所葛生伝承館

発注課葛生伝承館担当者落合電話葛生化石館内86-3332

備考・見本品を原稿とする。

ただしイラスト部分1か所については、支給するデータで作成をお願いします。

・イラストデータの支給媒体は、落札後、相談により変更できます。

・入稿日:平成28年6月24日。

易仓 安卓PDA使用培训.pdf说明书

安卓PDA使用培训坚持极客文化,用科技驱动跨境电商不断发展主讲人:***P P T仅用于易仓客户内部培训使用,禁止外传目 录Contents安卓PDA功能安卓PDA介绍12PPT 仅用于易仓客户内部培训使用,禁止外传01安卓PDA介绍P P T仅用于易仓客户内部培训使用,禁止外传安卓PDA介绍安卓PDA的优势1、借助PDA手持终端规范业务流程,使货位管理更加精细化,提高库存准确度和拣货效率、降低库存损失;2、人工录入收发货信息容易出现错漏,利用PDA手持终端可实时采集条码数据,大大提高库存的准确度;3、相较于传统老WINCE设备反应速度更快,操作更加顺畅。

P P T仅用于易仓客户内部培训使用,禁止外传02安卓PDA使用讲解P P T仅用于易仓客户内部培训使用,禁止外传安卓PDA使用讲解一、基础设置 1、角色权限设置2、PDA授权二、功能介绍 1、登录2、收货3、上架4、下架5、打包复合6、查询库存7、库存调整8、货架调整9、 仓库盘点10、 查询订单P PT 仅用于易仓客户内部培训使用,禁止外传1、PDA登录账号权限设置通过ERP仓配管理系统-》系统设置-》角色管理进行PDA权限设置。

勾选该账户需要访问的功能,点击保存,即可控制对应的功能能否使用。

P P T仅用于易仓客户内部培训使用,禁止外传2、PDA授权PDA在购买之后对应的PDA已经安装好PDA程序,对应授权也已经正常授权过注意事项:1、公司代码须填写客户代码,邀请码需要由易仓进行配置,邀请码唯一且不能重复使用。

注册成功后,后续使用这台PDA就不需要再次注册授权。

2、PDA程序要升级时,可以找易仓服务部同事获取安装包,升级操作不用卸载老的程序,直接覆盖安装即可。

假如删除之后重新安装则老的授权将失效不能使用。

需要重新获取新授权才能使用。

P P T仅用于易仓客户内部培训使用,禁止外传1、PDA登录P P T仅用于易仓客户内部培训使用,禁止外传2、收货通过PDA收货,有以下几种模式:按单收货,按箱收货,按箱+SKU收货,按小车收货,适用于海外仓收货。

数据抽取

product.product_id sales_product_id, sales_customer_id, sales_time_id,

sales_channel_id, sales_quantity_sold, sales_dollar_amount

FROM temp_sales_step1, product

方法三:

Transforming Data Using MERGE

下面我先以一个例子说明:

MERGE INTO products t USING products_delta s

ON (t.prod_id=s.prod_id)

WHEN MATCHED THEN UPDATE SET

WHERE NOT EXISTS (SELECT 1 FROM product p WHERE p.product_name=s.product_name);

这个CTAS statement语句就可以把查询出的新的SALE记录。

咱们也可以做左链接:

CREATE TABLE temp_sales_step2 NOLOGGING PARALLEL AS

FROM temp_sales_step1, product

WHERE temp_sales_step1.upc_code = product.upc_code (+);

把所有在维表中没有找到product_name的记录的sales_product_id设置为空。

数据源非关系数据库

ETL处理的数据源除了关系数据库外,还可能是文件,例如txt文件、excel文件、xml文件等。对文件数据的抽取一般是进行全量抽取,一次抽取前可保存文件的时间戳或计算文件的MD5校验码,下次抽取时进行比对,如果相同则可忽略本次抽取。

药品质量查询函

药品批发企业GSP文件体系实例参考贵州省药品监督管理局培训中心编委名单主编:副主编:王编委:前言国家药品监督管理局为加快GSP认证步伐,对未来三年监督实施GSP认证工作进行了部署,为落实上述任务,协助药品经营企业建立一套符合GSP要求的、与国际接轨的、系统科学的质量保证体系,提高企业综合实力和整体竞争水平,确保2004年底前药品批发企业都通过GSP认证,由贵州省药品监督管理局培训中心组织省内长期从事GSP管理工作的专家及有实践经验的人员共同编纂《药品批发企业GSP文件体系实例参考》。

本实例参考共分《质量管理手册》、《质量管理职责》、《程序文件》、《作业指导书》、《质量管理记录表》、《中药材、中药饮片管理》、《特殊管理药品的管理》七个部分。

《质量管理手册》系统介绍公司的质量管理体系范围,规定质量管理体系的运行过程,描述各过程的程序和相互作用,确定过程的文件形成引用文件化程序;《质量管理职责》系统介绍了各组织、各岗位的质量管理职责;《程序文件》系统介绍了对各质量管理体系过程的程序、职责、权限、实施要求;《作业指导书》,对具体的业务或作业的操作方法、标准进行了明确的规定,《质量管理记录表》为特别形式的文件,以确定实际性操作要求,提供作业结果的客观论据,明确指示记录等项作业活动的过程和结果。

此外,在文件体系中,我们将中药材、中药饮片及特殊管理的药品部份单列,以使企业根据各自经营范围的需要进行增减编纂。

培训中心推出这本实例参考与GSP有关法规紧密结合、集系统性、全面性、实用性、可操作性于一体,植根于企业,来自于基层。

该文件系统在药品经营企业试运行过程中证明是行之有效的。

由于实施GSP还处于一个探索与总结阶段,本实例参考仍然存在一些疏漏与偏颇。

希望各企业在参考的基础上去腐存菁,量体裁衣,建立既符合GSP认证要求,又结合本企业文化,具有更强操作性的完美体系。

在编纂实例参考过程中,得到徐丽蓉、熊慧林、林开中副主任药师的指导,在此表示感谢。

新版质量手册检验检测机构资质认定评审准则新版

质量手册【最新资料,WORD文档,可编辑修改】文件控制编号:NW/QMA-01(第一版)依据《检验检测机构资质认定评审准则》编写文件控制状态:受控? 非受控□发放编号:编制:审核:批准:发布日期:2015年11月20日实施日期:2016年1月1日某某市场监督检验所发布授权Array书和不干预说明………………… (03) (04)1、概述 (05)2、 (06)3、 (08) (10) (10) (12) (14) (16)体系 (19)管理体系………………………………………………………………………第19页质量方针和目标 (21)公正性声明 (23)文件控制 (24)合同评审 (26)检测分包 (27)服务与供应品采购 (28)服务客户 (29)投诉 (30)不符合工作 (31)纠正措施 (32)预防措施 (33)改进 (34) (35)内部审核 (36)管理评审 (37)检测方法 (38)测定不确定度 (41)采样 (42) (43)质量Array控制…………………………… (44)结果报告 (46)5、附录 (49) (49) (50) (52) (54) (55) (59) (62)5. (63)5. (64)5 (66)5 (67)5 (68)5 (69)6、修订页 (70)我作为某某市场监督检验所的法人代表,现任命吕鹏为某某市场监督检验所的总经理。

为规范本公司的管理,确保检测结果的准确,确保让客户满意,现授权其按国家法律、法规要求,检验检测机构资质认定评审准则的要求建立本公司的管理体系,以规范本公司的管理和运作。

同时,依据相关法律规定,委托其行使我公司赋予的法律职权,履行相应的法律义务。

代理我行使我对本公司的各项管理,确保按照检验检测机构资质认定评审准则的要求开展管理各项检测活动。

我声明不会干预本公司的检测结果,亦不准本公司其他部门及领导以行政、经济等方式干预检测结果。

我承诺按照《中华人民共和国民法通则》的要求承担相应的法律责任。

产品说明书范文(共5篇)

篇一:产品使用说明书(范例)xxx化工有限公司xxxx使用说明书图片已关闭显示,点此查看产品名称:产品编号:用途:参阅产品安全资料施工方法:参阅产品安全资料公司名称:厂址:邮编:电话号码:传真号码:图片已关闭显示,点此查看图片已关闭显示,点此查看图片已关闭显示,点此查看图片已关闭显示,点此查看图片已关闭显示,点此查看图片已关闭显示,点此查看其余成份属于非危害性物质。

易燃。

对眼睛和皮肤有刺激。

皮肤接触可能引起过敏。

补充资料参阅第11部分。

一般情况:出现疑问或症状时,应该寻求医疗。

决不能给不省人事的人吃东西。

吸入:将病人移至空气新鲜处,使其保持安静并保暖。

如果呼吸不正常或停止,应进行人工呼吸。

如果失去知觉,应使其保持安全姿势并立即寻求医疗。

不可喂食任何东西。

眼部接触:拨开眼睑用大量清洁淡水冲洗至少10分钟,并寻求医疗。

皮肤接触:脱去被沾污的衣物,用肥皂水或认可的皮肤清洁剂彻底清洗皮肤。

切勿使用溶剂或稀释剂。

咽入:如果不慎咽入,应立即寻求医疗。

不要紧张。

切勿试图呕吐。

推荐的灭火材料为:抗酒精泡沫、二氧化碳、粉末、水雾。

切勿使用水喷射。

注意:火焰会产生浓密的黑烟。

分解产品可能有害健康。

应避免暴露于其中,并适时使用呼吸装置。

处于火中的封闭容器,应喷水进行冷却。

不得将灭火过程中产生的水和污染物排入下水道或河流。

远离火源,不要使用无保护装置的电器设备。

万一在狭窄空间内大量溢出,应立即撤离。

检查溶剂蒸汽量低于最低爆炸极限时,再进入该区域。

保持通风,避免吸入蒸汽。

按照第8部分所述做好个人防护措施。

用非易燃物如沙子、泥土、蛭石等处理溢料。

放置在户外的密闭容器内,并按照相关废弃法规加以处理(参考第13部分)。

清洁时最好使用洗涤剂。

切勿使用溶剂。

严禁将溢料倒入排水沟或河道。

如果排水沟、下水道、河流或湖泊被污染,应立即通知当地自来水公司。

万一江河或湖泊被污染,还应该通知环保局。

用过的容器可能有剩余的产品,包括易燃易爆气体。

产品关键词解析

行业词搜索 综合推荐 高曝光词 高转换词 低成本词

关键词库

数据数管据家管家

知行情>RFQ商机 知行情>热门搜索词 知行情>行业视角 知己>我的词 知己>我的产品>词来源 知买家>访客详情

搜索搜页索页面面

下拉框>推荐相关词 下拉框>产品标签词 同行产品详情>底部相关搜索词 发布产品>相关推荐词

其其他他渠渠道

开通外贸直通车之后可以在关键词工具中搜索关键词,行业词搜索,高 曝光词,高转换词,低成本词,同时还有系统推荐关键词,需要筛选, 可以查到推广评分。

第二章 查找关键词的方法

2.14 谷歌 Adwords

需要借助翻墙软件(时空隧道)

一般流程:注册谷歌账号

搜索adwords

击付费在线广告

注册adwords(跳

第二章 查找关键词的方法

2.10 知己>我的词

我的词每周每月更新, 可以查询到曝光情况。

第二章 查找关键词的方法

2.11 知己>我的产品>词来源

第二章 查找关键词的方法

2.12 知买家>访客详情

访客详情关键词比较精准,词量较少,筛选可以对症下药。

第二章 查找关键词的方法

2.13 P4P关键词工具

同行设置的产品关键词 询盘中客户使用的关键词 其他搜索引擎>谷歌,亚马逊

第二章 查找关键词的方法

2.1 下拉框>推荐相关词

第二章 查找关键词的方法

2.2 下拉框>产品标签词

第二章 查找关键词的方法

2.3 同行产品详情>底部相关搜索词

第二章 查找关键词的方法

2.4 同行设置的产品关键词

专业用语(部品用)

43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 8リッパー スプリング 反り ダイセット ダイハイト 抜き ピッチ 送り 絞り 変形 リミットスイッチ ブロック メッキ リブ ゲート ピンゲート ステンレス 焼きいれ スライドコア クリアランス 樹脂 収縮率 狙い寸法 電極 放電 面取り 離型 冷却 型締め力 ばり取り やすり 油砥石 磨き ピンゲージ シム ガス抜き 粗加工 仕上げ加工 肉厚 温調機 割れ 抜き取り検査

リーマでも穴を仕上げる サンドペーパーでこの面を仕上げて下さい このバイトの使い方を教えましょう ノギスでここを測ってください できるだけトライ回数を減らす この種類のカプラは国内では調達できない この製品の寸法はばらつきがある ガタが大きいのもバリの原因の一つ 圧力が足らないので、ひけがでた ここのシボをもう一回やり直してください 溶接しても、直れない このロットは全部ダコンで不良になった カス浮きで連続生産できない

ぱんち だい だいぷれーと すとりっぱ すぷりんぐ そり だいせっと だいはいと ぬき ぴっち おくり しぼり へんけい りみっとすいっち ぶろっく めっき りぶ げーと ぴんげーと すてんれす やきいれ すらいどこあ くりあらんす じゅし しゅうしゅくりつ ねらいすんぽう でんきょく ほうでん めんどり りけい れいきゃく かたじめりょく ばりとり やすり あぶらといし みがき ぴんげーじ しむ がすぬき あらかこう しあげかこう にくあつ おんちょうき われ ぬきとりけんさ

产品需求规格书

XX项目产品需求规格说明书模板目录1 文档介绍 (2)1.1 文档目的 (2)1.2 文档范围 (2)1.3 读者对象 (3)1.4 参考文档 (3)1.5 术语及缩写解释 (3)2 综合描述 (3)2.1 产品介绍 (3)2.2 产品面向的用户群体(可选) (4)2.3 产品应当遵循的标准或规范 (4)2.4 产品范围 (4)2.5 产品涉众(涉及角色) (4)2.6 设计和实现的限制 (5)2.7 假设和约束(依赖) (5)3 产品需求 (6)3.1 需求分类 (6)3.2 用例图 (7)3.3 功能需求 (8)3.3.1 需求描述 (8)3.3.2 特殊需求 (9)3.3.3 数据规范 (9)3.4 非功能需求(包括但不限制于以下几项) (9)3.4.1 时间特性要求 (9)3.4.2 精度要求 (10)3.4.3 业务量估算 (10)3.4.4 灵活性 (10)3.4.5 可用性 (10)3.4.6 安全性 (11)3.4.7 兼容性 (11)3.4.8 易用性 (12)3.4.9 可维护性 (12)3.5 运行环境 (13)3.5.1 设备及分布 (13)3.5.2 支撑软件 (13)3.6 接口 (13)3.6.1 硬件接口 (13)3.6.2 软件接口 (14)3.6.3 通讯接口 (14)3.6.4 用户接口 (14)4 验收标准 (15)4.1 功能验收标准 (16)4.2 非功能性验收标准 (16)附录A:需求建模及分析报告 (16)A. 1需求模型1 (16)A. 2需求模型N (16)附录B:需求确认 (16)【对本文档的说明:本文档中黑色斜字体为说明性文字,黑色正常字体为需求规格说明书实际写作时必需部分。

蓝色字体为举例说明文字。

】1文档介绍1.1 文档目的提示:软件需求规格说明主要描述系统的概貌、功能要求、性能分析、运行要求和将来可能提出的要求。

阐述一个软件系统必须提供的功能和性能以及它所要考虑的限制条件,它应该尽可能完整地描述系统预期的外部行为和用户可视化行为。

新产品鉴定程序及资料准备提纲

新产品鉴定程序及资料准备提纲一、鉴定程序1、准备鉴定资料。

2、确定鉴定委员会专家名单。

需是同一技术领域或相关行业的专家,要求人数7人以上,其中高级职称(高工、副教授、副研究员以上)的5人以上。

3、向市科委提交鉴定资料,并提出要求鉴定的申请(申请表向市科委工业专利科领取)。

4、上报杭州市科委或省科技厅鉴定资料,领取鉴定许可证,并确定鉴定时间和地点。

5、召开鉴定会6、鉴定证书整理报组织鉴定单位盖章,领取鉴定证书。

二、所需的鉴定资料目录1、鉴定大纲2、计划任务书3、查新报告(填补国内空白或国内领先的产品必须准备)4、试制总结报告5、产品标准及编制说明(是企业标准必备,并需到市技术监督局备案)6、标准化审查报告7、产品检测报告(需带有‘MC’或‘MA’标志的报告,并且是型式试验报告)8、用户意见报告(2~3份)9、投产条件报告10、经济效益分析报告11、环境检测报告或有关证明(有‘三废’排放的企业需准备)12、产品图样及零部件样一套备用(机械、电气类企业需准备)13、产品工艺技术文件一套备用三、鉴定资料撰写的一般提纲一)、鉴定大纲1、前言(或任务来源):对项目或产品的内容、列入计划情况、完成时间、完成的情况作简要说明。

2、鉴定的性质:省级新产品鉴定3、鉴定依据:计划的文号和名称产品标准代号和名称浙科成发(95)297《浙江省科学技术成果鉴定办法》4、鉴定目的及内容审查提供鉴定的技术文件和资料是否齐全、完整、统一;其正确性是否符合有关标准要求,可否指导生产;审查产品(或项目)的主要技术指标是否达到计划任务书和标准要求,对产品制造工艺的合理性、可行性、先进性及应用前景作出评价;对产品(项目)的技术水平作出评价。

5、鉴定的形式和程序鉴定以会议形式进行,邀请同行专家成立鉴定委员会,设主任委员一名,副主任委员一名(或二名),委员若干名,由鉴定委员会负责鉴定。

宣读技术文件;审查技术文件和资料,察看样品(样机),考察生产现场;讨论并形成鉴定意见。

制药企业验证

(Batch Production Record,批生产记录)草案,按照草案的 要求操作设备,观察、调试、取样并记录 运行参数;

④将验证数据和结果直接填人方案的空白记录部分,或作 为其附件,避免转抄。人工记录和计算机打印的数据作为原始 数据。数据资料必须注明日期、签名,并具有可溯性。

❖ 洁净室(区)内各种管道、灯具、风口以及其他公用设施,在 设计和安装时,应考虑使用中避免出现不易清洁的部位。与墙 壁或天棚的连接部均应密封。

❖ 洁净室(区)应根据生产要求提供足够的照明。主要工作室的 照度宜为300勒克斯,对照度有特殊要求的生产部位可设置局 部照明。厂房应有紧急照明设施。

❖ 洁净室(区)安装的水池、地漏不得对药品产生污染。100级 洁净 (区)不得设置地漏。

就生产设备而言,性能确认系指通过系统联动试车的方法, 考察工艺设备运行的可靠性、主要运行参数的稳定性和运行结 果重现性的一系列活动。故其实际意义即指模拟生产。

返回目录

• PQ

性能确认中应注意以下各点: ①流量、压力和温度等监测仪器必须按国家技术监督部门

规定的标准进行校 验,并有校验证书; ②制订详细的取样计划、试验方法和试验周期,并分发到

返回目录

四 验证的内容

• 清洗验证 • 检验方法验证 • 产品验证 • 原料药的生产验证 • 物料的验证 • 计算机验证

返回目录

五 怎么来做验证

• 验证工作基本程序

1、验证组织 • 根据不同的验证对象,分别组建由各有关部门人员

参加的验证小组。验证小组由企业验证总负责人, 即主管验证工作的企业领导人担任。 2、验证步骤 a.验证项目的立项

返回目录

MP-2501 说明书

前言本用戶手冊描述產品的操作和應用注意事項。

為了全面地瞭解和最佳化本產品的各種特性,我們建議您在使用本產品前仔細閱讀全部手冊內容,閱讀後請把本手冊妥善放置以備日後查閱。

版權聲明本產品的版權及所有印刷品的使用,包括書籍、雜誌和音樂僅限於用於個人、家庭,或類似的用途,未經我方同意或書面許可,嚴禁對本印刷內容進行複製或修改。

用途聲明本公司對產品在出現故障情況下導致的不能正常錄製或播放,及其錄製的內容不承擔賠償責任。

產品保護不當的強烈擠壓或摔落會導致本產品損壞,故請妥善地保護本產品。

本產品若需要維修,只允許經授權的維修人員對產品進行維修,自行拆卸或打開本產品將會導致您的保修失效。

☆未經許可嚴禁全部或部分轉印本手冊內容。

☆本公司保留在不提前通知的情況下對本手冊內容進行修改的權利。

☆建議您把重要資料分開保存,以避免儲存資料在不當操作或其他情況造成儲存資料損壞或丟失。

針對使用不當、外在人為因素、維修或其他原因造成的儲存資料丟失或更改,本公司不負擔賠償責任。

☆本公司不對以下可能存在的情況承擔責任:比如,錄影或圖像侵權問題、儲存資料丟失或更改問題、或由第三方直接或間接使用本產品可能導致的經濟損失或賠償要求問題。

☆所有的商標和註冊商標使用權均歸本公司所有。

☆本公司對從網路上或個人電腦上下載的資訊內容不承擔責任。

☆我們儘量使用本手冊內容完整且通俗易懂,若您發現有任何不當之處,請及時與我們聯繫。

目錄l前言 (1)1.產品特色介紹/配件清單 (3)2. 產品介面介紹 (4)3. 電池使用須知……………….………………………………………………………………………………………5-64. 資料儲存位置…………………………………………………………………………………………………….....6-75. 基本操作………………………………………………………………………………………………………..…..7-96. 電影播放……………….…………………………………………………………………………………………10-137. 電子相簿………………………………………………………………………………………………….………14-188. 幻燈片播放 (18)9. 音樂播放器………………………………………………….………………………………………………...…19-2210. 數位錄放影機………………………………………………………………………………….……………..…23-2511. 數位錄音機………………………………………………………………………………...……………………26-2812. 廣播收錄音機…………………………………………………………………………………………………...29-3113. 多媒體瀏覽器……………………………………………………………………………………………...……32-3314. 系統設定……………………………………………………………………………………………..………….33-3715 轉檔軟體使用說明………………………………………………………………………………...…………….37-3916. 疑難解答........…………………………………………………...………………..……………………….……40-4217.規格表 (43)產品介紹1. 影片播放機2. 電子相簿3. 音樂隨身聽4. 數位錄音機5. 多媒體瀏覽器6. SD/MMC卡讀卡機7. USB隨身碟8. FM收錄音機9. AV-IN錄放影機配件清單USB連接線AV連接線電源供應器歐規轉美規插頭保護套了解本產品電池使用須知電池安裝及拆卸步驟1:將本產品背面朝上,喇叭向自己,喇叭向外掀開,腳架向外張開,以雙手大拇指抵住電池蓋,向箭頭方向推開電池蓋,最後再收起腳架。

家具五金检验标准指导书

外观

1.颜色:与标准样本颜色要求一致。

2.样本检验:参照样本,要求被检物外观与样本一

致。

3.模板检验:将被检物与有效模板(如:装饰铝条、

异型饰条、转角件)试装,不允许变形、扭曲。

样本

模板

参照

样本

目视

试装

尺寸

1.量具检验:使用量具检量,符合技术文件要求视

为合格。

2.模板检验:将被检物与有效模板试装,符合设计

螺丝刀

卡尺

试装

目视

螺丝

1.检查螺丝的牙距是否让使用者方便省力。

2.检查螺丝的杆径是否符合要求。

3.如果是实木用的螺丝、螺母,检查是否有加硬处

理。

螺丝刀

卡尺

试装

目视

4.焊接件:焊接部位应牢固,应无脱焊、虚焊、焊

穿;焊缝均匀,应无毛刺、锐棱、飞溅、裂纹等

缺陷。

铅笔硬度测固含量来货按正常喷涂次数均匀的喷涂于时间表面称其重量待漆膜完全干干燥后重量100固含干燥前重量试件电子称取试件用喷枪进行均匀喷涂5分钟后对光观察

适用范围:五金件质量检验

文件版本:

编号:

页码:共5页第1页

制定日期:

检验程序:来料抽样→对照样本→检验→试装→填写记录

检验项目

检验标准

工具

检验

方法

要求视为合格。

3.凡需攻丝的配件,孔位的深度应大于或等于文件

要求,丝口大小符合文件要求。

4.允许尺寸偏差:长度:-0.5mm;直径:-0.2mm。

卷尺

卡尺

样本

模板

参照

样本

尺量

试装

重量

称重后对比样本重量,允许重量偏差:

1.0.1~1g:±0.01~0.1g。

工具书的分类

工具书的分类了解工具书的分类及各类工具书的特点,对于及时获取所需的参考资料是很有意义的。

根据内容、体例和作用,工具书大体上可分为如下几类:(一)、字典和辞典。

这是人们经常使用的最普通的工具书。

它专收字词,按一定方法编排,注明读音,解释字、词意义。

这类书也称字书、辞书。

它包括字典、语文辞典、百科辞典、综合性辞典及不同语种的对译辞典等。

如《新华字典》、《现代汉语字典》、《辞海》、《中国人名大辞典》、《英汉辞典》等。

(二)、类书和政书。

类书是我国古代特有的一种工具书,它是辑录各门类或某一门类的资料,按照一定方法(通常分类)编排,便于查考事物的工具书。

类书按内容可分为两类。

一类是综合性的,它兼收天、地、人、事、物诸内容,把已有的文献资料摘录分类编排。

大型类书如《太平御览》、《四库全书》、《古今图书集成》等,所收资料极为丰富。

另一类是专科性的,如《太平广记》,它专收小说,把古代小说按内容分类收录。

政书是分类辑录、编排典章制度的书,是各个朝代政治、经济、军事、文化制度的资料汇编。

它也分类编排。

按其性质来说,实际上也属于类书的范畴。

如《通典》、《文献通考》等“十通”及历代的“会要”等书。

(三)、百科全书。

它是以辞典形式编排的巨型参考工具书。

现代百科全书扼要概述人类过去的知识和历史,并着重反映当代科学文化的最新成就。

它编收各学科或某一学科的专门述语、重要名词等,分列条目,并较详细地、系统地叙述和说明。

条目释文长短不一,视具体情况而定。

每条署名作者,重要条目并附参考书目。

现代百科全书始创于1751年法国资产阶级革命思想家狄德罗,以后世界各国都相继编辑出版。

著名的如《美国百科全书》、《大不列颠百科全书》、《世界大百科事典》等。

百科全书按收录范围也可分为综合性的和专科性的。

综合性的如《中国大百科全书》,专科性的如《中国医学百科全书》、《中国农业百科全书》等。

(四)、目录。

目录是记录书刊名称、作者、出版处、出版年月等情况,并按一定次序编排而成的工具书。

参考2汉仪诉青蛙、双飞判决书

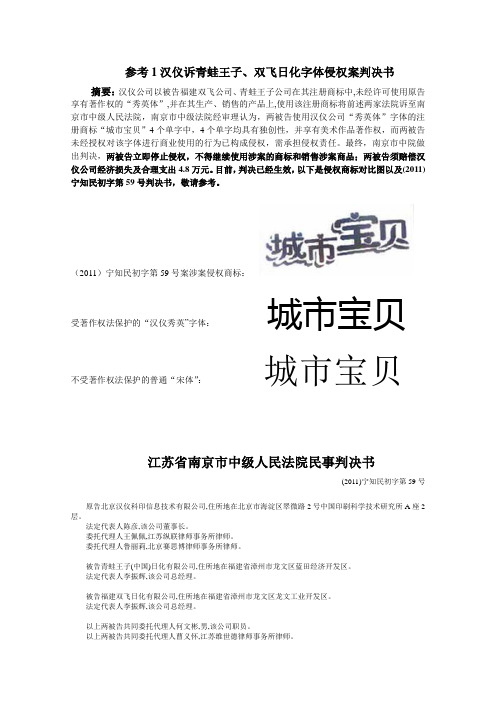

参考1汉仪诉青蛙王子、双飞日化字体侵权案判决书摘要:汉仪公司以被告福建双飞公司、青蛙王子公司在其注册商标中,未经许可使用原告享有著作权的“秀英体”,并在其生产、销售的产品上,使用该注册商标将前述两家法院诉至南京市中级人民法院,南京市中级法院经审理认为,两被告使用汉仪公司“秀英体”字体的注册商标“城市宝贝”4个单字中,4个单字均具有独创性,并享有美术作品著作权,而两被告未经授权对该字体进行商业使用的行为已构成侵权,需承担侵权责任。

最终,南京市中院做出判决,两被告立即停止侵权,不得继续使用涉案的商标和销售涉案商品;两被告须赔偿汉仪公司经济损失及合理支出4.8万元。

目前,判决已经生效,以下是侵权商标对比图以及(2011)宁知民初字第59号判决书,敬请参考。

(2011)宁知民初字第59号案涉案侵权商标:受著作权法保护的“汉仪秀英”字体:城市宝贝不受著作权法保护的普通“宋体”:城市宝贝江苏省南京市中级人民法院民事判决书(2011)宁知民初字第59号原告北京汉仪科印信息技术有限公司,住所地在北京市海淀区翠微路2号中国印刷科学技术研究所A座2层。

法定代表人陈彦,该公司董事长。

委托代理人王佩佩,江苏纵联律师事务所律师。

委托代理人鲁丽莉,北京赛思博律师事务所律师。

被告青蛙王子(中国)日化有限公司,住所地在福建省漳州市龙文区蓝田经济开发区。

法定代表人李振辉,该公司总经理。

被告福建双飞日化有限公司,住所地在福建省漳州市龙文区龙文工业开发区。

法定代表人李振辉,该公司总经理。

以上两被告共同委托代理人何文彬,男,该公司职员。

以上两被告共同委托代理人曹义怀,江苏维世德律师事务所律师。

被告苏果超市有限公司,住所地在江苏省南京市白下区解放路53号。

法定代表人马嘉樑,该公司董事长。

委托代理人陈耿、孟兰凯,江苏法德永衡律师事务所律师。

原告北京汉仪科印信息技术有限公司(以下简称汉仪公司)诉被告青蛙王子(中国)日化有限公司(以下简称青蛙王子公司)、福建双飞日化有限公司(以下简称福建双飞公司)、苏果超市有限公司(以下简称苏果超市)侵害著作权纠纷一案,本院受理后依法组成合议庭,于2011年4月1l日公开开庭进行了审理。

药品质量管理文件目录#

诚信药房药品质量管理文件目录一、管理职责1、药学科主任职责2、药房主任职责***3、药库主任职责**4、临床药学室主任职责*5、药库保管员职责**6、药库会计职责**7、采购人员职责**8、药库工人职责**9、配方人员职责***10、核对人员职责***11、药物咨询窗口人员职责***12、药房值班人员职责***13、临床药师职责*14、科文档管理人员职责15、科核算人员职责16、药学科质量负责人职责17、药学科质量管理员职责*** **二、质量管理制度1、药学科质量管理制度2、首营药品(材料)首营企业审核管理制度**3、药品(材料)购进与验收管理制度**4、药品(材料)储存、陈列与养护管理制度**5、一次性无菌医疗器械购进、验收管理制度**6、一次性无菌医疗器械储存、陈列与养护管理制度** ***7、特殊药品管理制度** ***8、中药饮片购进与验收管理制度**9、中药饮片储存、陈列与养护管理制度** ***10、处方调配管理制度***11、拆零药品管理制度** ***12、药品质量问题处理和报告制度** ***13、药品不良反应报告制度** ***14、质量信息管理制度** ***15、药品质量证明文件收集、管理制度**16、近效期药品管理制度** ***17、不合格品管理制度** ***18、环境与个人卫生管理制度** *** *19、药学科学习、培训管理制度** *** *20、药学服务质量管理制度** *** *21、仪器、设备管理制度** *** *22、质量管理制度执行情况检查考核制度23、药品会计、微机管理制度** *** *24、进口药品管理制度** ***三、程序性文件1、药品(材料)采购程序**2、药品(材料)验收程序**3、药品(材料)储存、养护程序** ***4、不合格(或有问题)药品(材料)处理程序** ***5、首营药品审批程序**6、临时用药(材料)采购和使用程序** ***7、处方调配程序***8、处方复核程序***9、汤剂制备程序***10、药房领药程序** ***11、药库发货程序** ***四、记录文件1、近效期药品月报表** ***2、药品(材料)验收记录**3、合同履行情况审核记录**4、不合格品处理记录** ***5、业务培训记录** *** *6、库房温湿度记录** ***7、药品(器材)养护记录** ***8、临床要货和缺货记录** ***9、服务投诉与处理记录** ***10、临床走访记录** ***11、药品质量问题处理记录** ***12、药品不良反应登记表** *** *13、病区药柜检查记录***14、特殊药品管理检查记录** ***15、药品破损记录** ***16、药事管理委员会会议记录17、药学科会议记录18、二级科室会议记录** ***19、处方检查记录***20、药品交班记录***21、中药饮片称重误差检查记录***22、质量管理制度执行情况检查与考核记录23、首营药品申请表**24、临床临时用药申请表** ***五、行政管理制度(上墙部分)1、药事管理委员会工作制度2、药学科工作制度3、药房工作制度***4、中药房工作制度***5、临床药学室工作制度*6、药库管理制度**7、中药库管理制度**8、急诊药房值班工作制度***9、处方制度***10、药品入库工作制度**11、药品保管工作制度**12、药品发放工作制度**13、药品统计工作制度**14、药品盈亏、报废处理制度** ***15、药库安全制度**六、规范1、盐城市第三人民医院药学服务规范(试行)** *** *2、十个不准** ***3、十个必须** ***备注:药库** 药房*** 临床药学室* 科办未标注请各科室通过学习,讨论如何执行,并将文件中存在不足之处以书面形式上报。