2009年版英国再生障碍性贫血诊断与治疗指南【模板】

再生障碍性贫血

年龄、性别和遗传因素可能会增加患病风险。

临床表现和诊断

疲劳和疼痛

患者可能感到持续的疲劳、乏力 以及体力活动受限。

皮肤瘀斑

皮肤容易淤血,表现为易产生瘀 斑。

出血

常见的出血症状包括牙龈出血、 鼻出血、月经过多以及易出现瘀 斑。

治疗方法

1

药物治疗

使用免疫抑制剂和促进造血的药物,以

造血干细胞移植

3 生活质量

提供适当的治疗和支持,可以显著改善患者的生活质量。

预防措施和注意事项

免疫接种

定期接种疫苗可以降低感染风险。

定期检查

定期进行骨髓检查以及其他相关的检查以及纠 正治疗。

避免暴露

减少与有毒物质和辐射的接触。

健康生活方式

保持健康的生活方式,包括均衡饮食、充足睡 眠和适量锻炼。

再生障碍性贫血

再生障碍性贫血是一种罕见但严重的血液疾病,其特征是骨髓无法产生足够 数量的血细胞。本演示将介绍该疾病的定义、原因以及治疗方法。

定义和原因

再生障碍性贫血

一种罕见的骨髓疾病,骨髓无法产生足够数量的红细胞、白细胞和血小板。

原因

多种因素可能导致该疾病,包括自身免疫性疾病、化疗药物、辐射暴露以及某些感染。

2

帮助骨髓重新恢复正常功能。

通过移植健康的造血干细胞来取代患者

异常的骨髓。

3

支持治疗

输注血液和血小板、控制感染、治疗并 发症等以提供支持。

再生障碍性贫血的预后

1 预后取决于

疾病严重可以通过治疗获得完全缓解,而另一些可能需要长期的治疗或造血干细胞移植。

再生障碍贫血报告模板

再生障碍贫血报告模板引言再生障碍性贫血(AA)是一种罕见但严重的造血系统疾病,其特征为造血干细胞数量减少和造血功能受损。

本报告旨在提供关于再生障碍性贫血的详细信息,包括病因、发病机制、临床表现、诊断和治疗等方面的内容。

通过深入了解这一疾病,可以为医生和患者提供更好的医疗决策和管理。

1. 病因再生障碍性贫血的病因尚不明确,但家族聚集性和暴露于某些环境和化学物质的因素似乎与其发病有关。

感染(如乙型肝炎病毒、Epstein-Barr病毒等)、药物暴露(如苯扎贝特、卡马西平等)和自身免疫反应等也可能导致该疾病的发生。

2. 发病机制在再生障碍性贫血中,骨髓中的造血干细胞和祖细胞受到损害,导致红细胞、白细胞和血小板生成减少或中断。

这种损害可以是由于免疫介导的T淋巴细胞攻击造血干细胞,也可以是由于骨髓中异常造血细胞的增加而导致的。

3. 临床表现再生障碍性贫血的临床表现因个体差异而有所不同,但常见的症状包括贫血、易出血和易感染。

患者可能会出现乏力、头晕、皮肤苍白以及瘀点、瘀斑、鼻出血、牙龈出血等出血倾向。

由于白细胞数量减少,患者容易感染,并可能出现发热、咽痛、咳嗽等症状。

此外,由于血小板减少,患者可能有易瘀斑、皮肤淤血、鼻出血、月经过多等表现。

4. 诊断再生障碍性贫血的诊断需要排除其他可能的病因,如先天性骨髓发育异常、骨髓浸润等。

诊断依据包括骨髓活检结果、血液学检查、染色体分析、免疫学检查和免疫组织化学等。

其中,骨髓活检是确诊此疾病的关键检查。

5. 治疗再生障碍性贫血的治疗策略根据患者的临床表现和病情的严重程度而定。

治疗的目标是恢复造血功能、改善贫血、控制出血和感染,以及提高患者的生活质量。

治疗方法包括药物治疗、免疫抑制疗法、造血干细胞移植和对症治疗等。

6. 预后再生障碍性贫血的预后取决于许多因素,包括患者年龄、病情的严重程度、治疗的及时性和有效性等。

对于一些轻度病例,约30%的患者在没有治疗的情况下可以自愈。

再生障碍性贫血诊断与治疗指南2010(英国)

Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of aplastic anaemiaBritish Committee for Standards in HaematologyAddress for Correspondence:BCSH SecretaryBritish Society for Haematology,100 White Lion StreetLondonN1 9PFe-mail: bcsh@Writing group:JCW Marsh 1, SE Ball 2, J Cavenagh 3, P Darbyshire 4, I Dokal 5, EC Gordon-Smith 2, AJ Keidan 6, A Laurie 7, A Martin 8, J Mercieca 9, SB Killick 10, R Stewart 11, JAL Yin 12 Disclaimer.While the advice and information in these guidelines is believed to be true and accurate at the time of going to press, neither the authors, the British Society for Haematology nor the publishers accept any legal responsibility for the contents of these guidelines.Date for guideline reviewMay 2010_______________________________________________________1 King’s College Hospital, London2 St George’s Hospital, London3 Barts and The London Hospital, London4 Birmingham Children’s Hospital, Birmingham5Barts and The London School of Medicine and Dentistry, London6Queen Elizabeth Hospital, King’s Lynn, Norfolk7 Ashford Hospital, Middlesex, London8 Patient representative9 St Helier Hospital, Carshalton10 Royal Bournemouth Hospital, Dorset11 Chesterfield Royal Hospital, Derbyshire12 Manchester Royal Infirmary, ManchesterIntroductionThe guideline group was selected to be representative of UK based medical experts, experienced district general hospital haematologists and a patient representative. MEDLINE and EMBASE were searched systematically for publications in English from 2004-2008 using key word aplastic anaemia. The writing group produced the draft guideline which was subsequently revised by consensus by members of the General Haematology Task Force of the British Committee for Standards in Haematology. The guideline was then reviewed by a sounding board of approximately xx UK haematologists, the BCSH (British Committee for Standards in Haematology) and the British Society for Haematology Committee and comments incorporated where appropriate. Criteria used to quote levels and grades of evidence are as outlined in appendix 3 of the Procedure for Guidelines Commissioned by the BCSH (/process1.asp#App3).The objective of this guideline isto provide healthcare professionals with clear guidance on the diagnosis and management of patients with acquired aplastic anaemia. The guidance may not be appropriate to patients with inherited aplastic anaemia and in all cases individual patient circumstances may dictate an alternative approach. Because aplastic anaemia is a rare disease, many of the statements and comments are based on review of the literature and expert or consensus opinion rather thanon clinical studies or trials.Guidelines updateA previous guideline on the diagnosis and management of aplastic anaemia was published in 2003 in the British Journal of Haematology. This guideline is an update of the 2003 guideline and is to replace the 2003 guideline.Summary of key recommendations•Aplastic anaemia (AA) is a rare but heterogeneous disorder. The majority (70-80%) of these cases are categorized as idiopathic because their primary aetiology is unknown. In a subset of cases, a drug or infection can be identified that precipitates the BM failure/aplastic anaemia, although it is not clear why only some individuals are susceptible. In approximately 15-20% of patients the disease is constitutional/inherited, where the disease is familial and/or presents with one or more other somatic abnormalities.•Careful history and clinical examination is important to help exclude rarer inherited forms.• A detailed drug and occupational exposure history should always be taken. Any putative drug should be discontinued and should not be given again to the patient. Any possible association of aplastic anaemia with drug exposure should be reported to the MHRA using the Yellow card Scheme•All patients presenting with aplastic anaemia should be carefully assessed to: (i) confirm the diagnosis and exclude other possible causes of pancytopeniawith hypocellular bone marrow(ii) classify the disease severity using standard blood and bone marrow criteria (iii) document the presence of associated PNH and cytogenetic clones. Small PNH clones, in the absence of haemolysis, occur in up to 50% of patients with aplastic anaemia and abnormal cytogenetic clones occur in up to 12% of patients with aplastic anaemia in the absence of MDS(iv) exclude a possible late onset inherited bone marrow failure disorder• A MDT approach to the assessment and management of newly presenting patients is recommended. A specialist centre with expertise in aplastic anaemia should be contacted soon after presentation to discuss a management plan for the patient.•Best supportive care(i) Prophylactic platelet transfusions should be given when the platelet count is <10 x 109/l (or < 20 x 109/l in the presence of fever).(ii) There is no evidence to support the practice of giving irradiated blood components except for patients who are undergoing BMT. We would recommend empirically that this practice is extended to patients receiving immunosuppressive therapy.(iii) Transfusion of irradiated granulocyte transfusions may be considered in patients with life-threatening neutropenic sepsis.(iv) The routine use of rHuEpo in aplastic anaemia is not recommended. A short course of G-CSF may be considered for severe systemic infection that is not responding to intravenous antibiotics and anti-fungal drugs, but should be discontinued after one week if there is no increase in the neutrophil count.and antifungal drugs should be given to patients with antibiotic(v) Prophylacticneutrophil count < 0.2 x 109/l. Intravenous amphotericin should be introduced into the febrile neutropenia regimen early if fevers persist despite broad spectrum antibiotics.(vi) Iron chelation therapy should be considered when the serum ferritin is > 1000μg/l.•Definitive treatment(1) Infection or uncontrolled bleeding should be treated first before givingimmunosuppressive therapy. This also applies to patients having BMT, although it may sometimes be necessary to proceed straight to BMT in the presence of severe infection as a BMT may offer the best chance of early neutrophil recovery.(2) Haemopoietic growth factors such as rHuEpo or G-CSF should not be used ontheir own in newly diagnosed patients in an attempt to ‘treat’ the aplastic anaemia.(3) Prednisolone should not be used to treat patients with aplastic anaemiabecause it is ineffective and encourages bacterial and fungal infection.(4) Allogeneic BMT from an HLA identical sibling donor is the initial treatment ofchoice for newly diagnosed patients if they have severe or very severe aplastic anaemia, are < 40 years old and have an HLA compatible sibling donor. There is no indication for using irradiation-based conditioning regimens for patients undergoing HLA identical sibling BMT for aplastic anaemia. The recommended source of stem cells for transplantation in aplastic anaemia is bone marrow. (5)Immunosuppressive therapy is recommended for (1) patients with non-severeaplastic anaemia who are transfusion dependent (2) patients with severe or very severe disease who are > 40 years old and (3) younger patients with severe or very severe disease who do not have an HLA identical sibling donor The standard immunosuppressive regimen is a combination of ATG and ciclosporin. ATG must only be given as an in-patient. Ciclosporin should be continued for at least 12 months after achieving maximal haematological response, followed by a very slow tapering, to reduce the risk of relapse. The routine use of long term G-CSF, or other haemopoietic growth factors, afterATG and ciclosporin, is not recommended outside the setting of prospective clinical trials.(6) MUD BMT may be considered when a patient has severe aplastic anaemia, has afully matched donor, is < 50 years old (or 50-60 years old with good performance status), and has failed at least one course of ATG and ciclosporin.The optimal conditioning regimen for MUD BMT is uncertain, but currently a fludarabine, non-irradiation-based regimen is favoured for younger patients.•There is a high risk (around 40%) of relapse of aplastic anaemia in pregnancy.Supportive care is the mainstay of treatment in pregnancy and the platelet count should be maintained > 20 x 109/l, if possible. It is safe to use ciclosporin in pregnancy.1. Definition and clinical presentationAplastic anaemia is defined as pancytopenia with a hypocellular bone marrow in the absence of an abnormal infiltrate and with no increase in reticulin. For a comprehensive update on the pathophysiology, the reader is directed to a recent review (Young et al, 2006). For these guidelines we will focus specifically on idiosyncratic acquired aplastic anaemia, and will not refer to the inevitable and predictable aplasia that occurs after chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy. The incidence of acquired aplastic anaemia in Europe and North America is around 2 per million population per year. The incidence is 2-3 times higher in East Asia. There is a biphasic age distribution with peaks from 10-25 years and > 60 years. There is no significant difference in incidence between males and females (Heimpel, 2000). Congenital aplastic anaemia is very rare, the commonest type being Fanconi anaemia which is inherited as an autosomal recessive disorder in most cases.Patients with aplastic anaemia most commonly present with symptoms of anaemia and skin or mucosal haemorrhage or visual disturbance due to retinal haemorrhage. Infection is a less common presentation. There is no lymphadenopathy or hepatosplenomegaly (in the absence of infection) and these findings strongly suggest another diagnosis (Gordon-Smith, 1991). In children and young adults, the findings of short stature, café au lait spots, and skeletal anomalies should alert the clinician to the possibility of a congenital form of aplastic anaemia,Fanconi anaemia, although Fanconi anaemia can sometimes present in the absence of overt clinical signs. Patients with Fanconi anaemia most commonly present between the ages of 3 and 14 years but can occasionally present later in their 30s (up to 32 in males and 48 years in females reported by Alter, [Young and Alter, 1994]). The findings of leukoplakia, nail dystrophy and pigmentation of the skin are characteristic of another inherited form of aplastic anaemia, dyskeratosis congenita, with a median age at presentation of 7 years (range 6 months to 26 years) (Dokal, 2000). Some affected patients may have none of these clinical features and the diagnosis is made later after failure to respond to immunosuppressive therapy (Vulliamy and Dokal, 2006). A preceding history of jaundice, usually 2-3 months before, may indicate a post-hepatitic aplastic anaemia (Gordon-Smith, 1991; Young and Alter, 1994).Many drugs and chemicals have been implicated in the aetiology of aplastic anaemia, but for only very few is there reasonable evidence for an association from case control studies, and even then it is usually impossible to prove causality (Young and Alter, 1994; Kauffmann et al, 1996; Baumelou et al, 1993; Issaragrissil et al, 1997; Heimpel, 1996), (see table 1).A careful drug history should be obtained detailing all drug exposures for a period beginning 6 months and ending one month prior to presentation (Kauffmann et al, 1996; Heimpel, 1996). If at presentation the patient is taking several drugs which may have been implicated in aplastic anaemia, even if the evidence is based on case report(s) alone, then all the putative drugs should be discontinued and the patient should not be re-challenged with the drugs at a later stage after recovery of the blood counts. The Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) should be informed using the Yellow Card Scheme on every occasion that a patient presents with aplastic anaemia where there is a possible drug association (website: ).Similarly, a careful occupational history of the patient may reveal exposure to chemicals or pesticides that have been associated with aplastic anaemia, as summarised in table 2.Recommendations(i) Aplastic anaemia is a rare disorder. Most cases are idiopathic, but carefulhistory and clinical examination is important to identify rarer inherited forms (ii) Although most cases of aplastic anaemia are idiopathic, a careful drug and occupational exposure history should be taken(iii) Any putative drug should be discontinued and should not be given again to the patient.Any possible association of aplastic anaemia with drug exposureshould be reported to the MHRA using the Yellow card Scheme.2. Investigations required for diagnosisThe following investigations are required to (1) confirm the diagnosis (2) exclude other possible causes of pancytopenia with a hypocellular bone marrow (3) exclude inherited aplastic anaemia (4) screen for an underlying cause of aplastic anaemia and (5) document or exclude a co-existing abnormal cytogenetic clone or a paroxysmal nocturnal haemoglobinuria (PNH) clone. See table 3 for a summary of investigations required for the diagnosis of aplastic anaemia.2.1 Full blood count, reticulocyte count, blood film and % HbFThe full blood count (FBC) typically shows pancytopenia although usually the lymphocyte count is preserved. In most cases the haemoglobin level, neutrophil and platelet counts are all uniformly depressed, but in the early stages isolated cytopenia, particularly thrombocytopenia, may occur. Anaemia is accompanied by reticulocytopenia, and macrocytosis is commonly noted. Careful examination of the blood film is essential to exclude the presence of dysplastic neutrophils and abnormal platelets, blasts and other abnormal cells such as hairy cells. The monocyte count may be depressed but the absence of monocytes should alert the clinician to a possible diagnosis of hairy cell leukaemia. In aplastic anaemia, anisopoikilocytosis is common and neutrophils may show toxic granulation. Platelets are reduced in number and mostly of small size. Fetal haemoglobin (HbF) should be measured pre-transfusion in children as this is an important prognostic factor in paediatric myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) which may feature in the differential diagnosis of pancytopenia in children. It may also be useful in screening for inherited bone marrow failure disorders in adults with apparent acquired disease.2.2 Bone marrow examinationBoth a bone marrow aspirate and trephine biopsy are required. Bone marrow aspiration and biopsy may be performed in patients with severe thrombocytopenia without platelet support, providing that adequate surface pressure is applied (BCSH, 2003).Fragments are usuallyreadily obtained from the aspirate. Difficulty obtaining fragments should raise the suspicion of a diagnosis other than aplastic anaemia. The fragments and trails are hypocellular with prominent fat spaces and variable amounts of residual haemopoietic cells. Erythropoiesis is reduced or absent, dyserythropoiesis is very common and often marked, so this alone should not be used to make a diagnosis of MDS. Megakaryocytes and granulocytic cells are reduced or absent; dysplastic megakaryocytes and granulocytic cells are not seen in aplastic anaemia. Lymphocytes, macrophages, plasma cells and mast cells appear prominent. In the early stages of the disease, one may also see prominent haemophagocytosis by macrophages, as well as background eosinophilic staining representing interstitial oedema. A trephine is crucial to assess overall cellularity, to assess the morphology of residual haemopoietic cells and to exclude an abnormal infiltrate. In most cases the trephine is hypocellular throughout but sometimes it is patchy, with hypocellular and cellular areas. Thus, a good quality trephine of at least 2cm is essential. A ‘hot spot’ in a patchy area may explain why sometimes the aspirate is normocellular. Care should be taken to avoid tangential biopsies as subcortical marrow is normally ‘hypocellular’. Focal hyperplasia of erythroid or granulocytic cells at a similar stage of maturation may be observed. Sometimes lymphoid aggregates occur, particularly in the acute phase of the disease or when the aplastic anaemia is associated with systemic autoimmune disease such as rheumatoid arthritis or systemic lupus erythematosus. The reticulin is not increased and no abnormal cells are seen. Increased blasts are not seen in aplastic anaemia, and their presence either indicates a hypocellular MDS or evolution to leukaemia [Marin, 2000; Tichelli et al, 1992].2.3Definition of disease severity based on the FBC and bone marrow findingsTo define aplastic anaemia there must be at least two of the following (1) haemoglobin < 10g/dl (2) platelet count < 50 x 109/l (3) neutrophil count < 1.5 x 109/l (International Agranulocytosis and Aplastic Anaemia Study Group, 1987). The severity of the disease is graded according to the blood count parameters and bone marrow findings as summarised in table 4 (Camitta et al, 1976; Bacigalupo et al, 1988). The assessment of disease severity is important in treatment decisions and has prognostic significance. Patients with bi-or tri-lineage cytopenias which are less severe than this are not classified as aplastic anaemia. However, they should have their blood counts monitored to determine whether they will develop aplastic anaemia with time.2.4 Liver function tests and viral studiesLiver function tests should be performed to detect antecedent hepatitis, but in post-hepatitic aplastic anaemia the serology is most often negative for all the known hepatitis viruses. The onset of aplastic anaemia occurs 2-3 months after an acute episode of hepatitis and is more common in young males (Brown et al, 1997). Blood should be sent for hepatitis A antibody, hepatitis B surface antigen, hepatitis C antibody and Epstein Barr virus (EBV). Cytomegalovirus (CMV) and other viral serology should be assessed if bone marrow transplantation (BMT) is being considered. Parvovirus causes red cell aplasia but not aplastic anaemia. HIV is not a recognised cause of aplastic anaemia, but it can cause isolated cytopenias. We would recommend that prior to a diagnosis of aplastic anaemia, appropriate investigations to exclude alternative aetiologies of cytopenias (B12, red cell folate and HIV) should be performed.2.5 Vitamin B12 and folate levelsVitamin B12 and folate levels should be measured to exclude megaloblastic anaemia which, when severe, can present with pancytopenia. If a deficiency of B12 or folate is documented, this should be corrected before a final diagnosis of aplastic anaemia is confirmed.2.6 Autoantibody screenThe occurrence of pancytopenia in systemic lupus erythematosus may (1) be autoimmune in nature occurring with a cellular bone marrow or (2) be associated with myelofibrosis or rarely (3) occur with a hypocellular bone marrow. Blood should be sent for anti-nuclear antibody and anti-DNA antibody in all patients presenting with aplastic anaemia.2.7 Tests to detect a paroxysmal nocturnal haemoglobinuria (PNH) clonePNH should be excluded by performing flow cytometry (Dacie and Lewis, 2001; Parker et al, 2005). The Ham test and sucrose lysis test have been abandoned by most centres as diagnostic tests for PNH. Analysis of glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchored proteins, such as CD55 and CD59 by flow cytometry, is a sensitive and quantitative test for PNH enabling the detection of small PNH clones which occur in up to 50% of patients with aplasticanaemia, the proportion depending on the sensitivity of the flow cytometric analysis used (Dunn et al, 1999; Socie et al, 2000, Sugimori et al 2005). Such small clones are most easily identified in the neutrophil and monocyte lineages in aplastic anaemia and will be detected by flow cytometry and not by the Ham test. If the patient has had a recent blood transfusion, the Ham test may be negative whereas a population of GPI-deficient red cells may still be detected by flow cytometry. However, the clinical significance of a small PNH clone in aplastic anaemia as detected by flow cytometry remains uncertain. Such clones can remain stable, diminish in size, disappear or increase. What is clinically important is the presence of a significant PNH clone with clinical or laboratory evidence of haemolysis. Urine should be examined for haemosiderin to exclude intravascular haemolysis which is a constant feature of haemolytic PNH. Evidence of haemolysis associated with PNH should be quantitated with the reticulocyte count, serum bilirubin, serum transaminases and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH).2.8Cytogenetic investigationsCytogenetic analysis of the bone marrow should be attempted although this may be difficult in a very hypocellular bone marrow and often insufficient metaphases are obtained. In this situation, one should consider FISH analysis for chromosomes 5 and 7 in particular. It was previously assumed that the presence of an abnormal cytogenetic clone indicated a diagnosis of MDS and not aplastic anaemia, but it is now evident that abnormal cytogenetic clones may be present in up to 12% of patients with otherwise typical aplastic anaemia at diagnosis (Appelbaum et al, 1989; Tichelli et al, 1996; Gupta et al, 2006). The presence of abnormal cytogenetics at presentation in children, especially monosomy 7, should alert to the likelihood of MDS. Abnormal cytogenetic clones may also arise during the course of the disease (Socie et al, 2000). The management of a patient with aplastic anaemia who has an abnormal cytogenetic clone is discussed in section 4.3.2.9Screen for inherited disordersPeripheral blood lymphocytes should be tested for chromosomal breakage to identify or exclude Fanconi anaemia. This should be performed in all patients who are BMT candidates. For all other patients, it is difficult to set an upper age limit for Fanconi anaemia screening because the age at diagnosis may sometimes occur in the fourth decade, and rarely in the fifth decade, of life (Alter 2007). Dyskeratosis congenita may be excluded by identifying a knownmutation but there are probably many mutations yet to be identified. Along with measuring telomere lengths, this is not currently available as a routine clinical service.2.10 Radiological investigations• A chest X-ray is useful at presentation to exclude infection and for comparison with subsequent films.•Routine X-rays of the radii are no longer indicated as all young patients should have peripheral blood chromosomes sent to exclude a diagnosis of Fanconi anaemia. •Abdominal ultrasound: the findings of an enlarged spleen and/or enlarged lymph nodes, raise the possibility of a malignant haematological disorder as the cause of the pancytopenia. In younger patients, abnormal or anatomically displaced kidneys are features of Fanconi anaemia.2.11Differential diagnosis of pancytopenia and a hypocellular bone marrowThe above investigations should exclude causes of a hypocellular bone marrow with pancytopenia other than aplastic anaemia. These include:•Hypocellular MDS/acute myeloid leukaemia (AML) can sometimes be difficult to distinguish from aplastic anaemia. The following features of MDS are not found in aplastic anaemia: dysplastic cells of the granulocytic and megakaryocytic lineages, blasts in the blood or marrow (World Health Organisation Classification of Tumours, 2001; Tuzuner et al, 1995).In trephine specimens, increases in reticulin associated with residual areas of haemopoiesis suggest hypocellular MDS rather than aplastic anaemia. The presence of abnormal localisation of immature precursors (ALIPs) is difficult to interpret in this context because small collections of immature granulocytic cells may be seen in the bone marrow in aplastic anaemia when regeneration occurs. As discussed previously, dyserythropoiesis is very common in aplastic anaemia.•Hypocellular acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL) occurs in 1-2% of cases of childhood ALL. Overt ALL usually develops within 3-9 months of the apparent bone marrow failure. In contrast to aplastic anaemia, the neutropenia is usually more pronounced than the thrombocytopenia and sometimes there is an increase in reticulin within the hypocellular bone marrow (Chessells, 2001). Immunophenotyping may help confirm the diagnosis.Treatment should not be deferred in severe aplastic anaemia in children just in case they turn out to have ALL. For all new paediatric cases of aplastic anaemia, a national central morphology review is planned under the aegis of the MRC Childhood Leukaemia Working Party Subgroup for rare haematological diseases.•Hairy cell leukaemia classically presents with pancytopenia but the accompanying monocytopenia is a constant feature of this disorder. It is usually difficult or impossible to aspirate on bone marrow fragments. In addition to the typical interstitial infiltrate of hairy cells with their characteristic ‘fried egg’ appearance in the bone marrow trephine, there is always increased reticulin. Immunophenotyping reveals CD20+, CD11c+, CD25+, FMC7+, CD103+ tumour cells which are typically CD5-, CD10- and CD23-. Although splenomegaly is a common finding in hairy cell leukaemia, it may be absent in 30-40% of cases (Catovsky, 2000).•Lymphomas, either Hodgkin’s disease or non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, and myelofibrosis may sometimes present with pancytopenia and a hypocellular bone marrow. The bone marrow biopsy should be examined very carefully for foci of lymphoma cells or fibrosis which may be seen in only a small part of the trephine. Since lymphocytes are often prominent in aplastic anaemia, immunophenotyping should be performed.Myelofibrosis is usually accompanied by splenomegaly and the absence of an enlarged spleen in the presence of marrow fibrosis should alert one to secondary malignancy. Marker studies and gene rearrangement studies will help confirm the diagnosis of lymphoma.•Mycobacterial infections can sometimes present with pancytopenia and a hypocellular bone marrow, this is seen more commonly with atypical mycobacteria. Other bone marrow abnormalities include granulomas, fibrosis, marrow necrosis, and haemophagocytosis.Demonstrable acid alcohol fast bacilli (AAFB) and granulomas are often absent in Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. AAFB are more frequently demonstrated in atypical mycobacterial infections where they are often phagocytosed by foamy macrophages. The bone marrow aspirate should be sent for AAFB culture if tuberculosis is suspected (Bain et al, 2001).•Anorexia nervosa or prolonged starvation may be associated with pancytopenia. The bone marrow may show hypocellularity and gelatinous transformation (serous degeneration/atrophy) with loss of fat cells as well as haemopoietic cells, and increased ground substance which stains a pale pink on haematoxylin/eosin stain (Bain et al, 2001).The pink ground substance may also be seen as on an MGG stained aspirate. Somedegree of fat change may also be seen in aplastic anaemia, especially early on in its evolution.• A recent comprehensive review on aplastic anaemia in children discusses in more detail conditions that may present with pancytopenia and a hypocellular bone marrow in children (Davies and Guinan, 2007).A multidisciplinary team (MDT) meeting approach is recommended to collate relevant results and treatment plan. Consideration should also be given to review of blood and bone marrow slides by a specialist centre, especially if there are unusual morphological features or where there is any doubt about the diagnosis.Recommendations(i) All new patients presenting with aplastic anaemia should be carefully assessedto:•confirm the diagnosis and exclude other possible causes of pancytopenia with hypocellular bone marrow•classify the disease severity using standard blood and bone marrow criteria•document the presence of associated PNH and cytogenetic clones•exclude a possible late onset inherited bone marrow failure disorder(ii) A MDT approach to the above assessment is recommended and also toformulate an appropriate management plan for the patient(iii) If there is doubt about the diagnosis and/or management plan, referral of the case for specialist advice and/or review of the blood and bone marrow morphology slides at a specialist centre, is encouraged.3.Supportive care3.1 Transfusional support。

再生障碍性贫血的诊治指南

再生障碍性贫血的诊治指南一跋制定指南的小组成员包括英国的基础医学专家、各地血液病学专家以及患者代表。

并系统收集了medline与EMBASE库在2004-2008之间刊发以aplastic anemia为关键词的所有文献。

草案由血液病学的标准委员会审定通过。

并经过全英国59名有丰富经验的血液病学专家、英国血液病学标准委员会、英国血液病社团的评审。

指南的目的是向专业人员提供获得性再障的诊断治疗中以详细确切的指导。

不适合于先天性再生障碍性贫血或有特殊的环境的个体。

由于再障是一种罕见疾病,难以全部进行大量临床试验,文中许多观点主要源于既往文献复习或专家的共识。

本期刊曾经登载过再障诊治指南(marsh等2003版);此新指南是03版旧指南的更新,并取代2003版指南。

建议归纳如下:1)再生障碍性贫血是一种罕见的异质性疾病。

绝大部分(70-80%)再障为特发性,原因不清。

一部分再障因感染或想、药物导致的骨髓衰竭,但仍不清楚有的个体对其易感。

近15-20%的再障为遗传性,此类患者有家族历史或有染色体畸形。

2)详尽得家族史以及临床检验对比排除某些罕见的遗传类型特别重要。

3)注意采集药物以及职业暴露史,可疑引起再障的药物应立即停药并且避免再次服用。

任何可疑导致再障的药物需要上报给MHRA(药品与健康监管机构),并填报黄色报卡。

4)所有有再障症状的患者需要进行以下评估:ⅰ明确诊断,并排除其他导致血细胞减少的骨髓低增生性疾病ⅱ以标准的血液以及骨髓指标评定再障的严重程度ⅲ确实是否存在与再障相关的PNH以及异常的细胞生成克隆。

50%的无溶血的AA患者中有微小的PNH克隆;在12%排除了MDS 的再障患者中有异常的细胞生成克隆(cytogenetic clone)治疗是联合应用抗胸腺细胞球蛋白(ATG)与环孢素。

ATG必须在住院观察下使用,环孢素需要在达到最大的血液效益后持续1年以上,缓慢减量避免复发;免疫抑制治疗开始后(因为临床试验ⅳ需排除迟发型的先天性骨髓衰竭疾病。

2009年英国再生障碍性贫血诊疗指南解读

2009年英国再生障碍性贫血诊疗指南解读张旗,李莉,闫金松(大连医科大学附属第二医院 血液科,大连 116027)通讯作者:闫金松 Email: yanjsdmu@英国再生障碍性贫血诊断治疗指南(2009)[1],主要由英国循证医学专家、地区性综合医院富有经验的血液学家及患者代表共同完成。

根据MEDLINE 及EMBASE 数据库的英文文献(2004年~2008年),首先撰写指南草稿,后经英国血液学标准委员会(British Committee for Standards Heamatology ,BCSH )血液病小组成员进行修订,之后再由59名BCSH 执业的血液学家修订和审阅。

该指南第一版发表于2003年[2],2009年为第二版,该指南不完全适合于先天性再生障碍性贫血(aplastic anemia ,AA ,简称再障)的诊治。

AA 是骨髓造血功能衰竭的疾病,其发病率偏低、治疗难度大、见效慢,目前我国尚无治疗该病的规范诊治指南。

为使广大的医务工作者更好的认识该病,规范该病的诊疗,提高治疗效果,故对2009年《英国再生障碍性贫血诊治指南》做一解读,以供参考。

指南的关键建议:(1)AA 是一种罕见的异质性疾病,病因基本未明。

70%~80%的病例为原发性,药物和感染可促进部分病例骨髓衰竭/AA 的发生,这可能与个体差异有关。

近15%~20%的病例为先天/遗传性,呈家族性,常伴发机体一个或多个异常。

(2)详细询问病史及临床检查对除外遗传性AA 很重要。

(3)详细了解药物和职业接触史,应停用或避免使用可能引起AA 的药物。

(4)所有AA 患者均需明确诊断,并排除其他导致骨髓增生低下的全血细胞减少性疾病;根据外周血和骨髓增生标准对疾病严重程度分级;记录合并的阵发性睡眠性血红蛋白尿(paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria ,PNH )和细胞遗传学克隆。

高达50%的无溶血AA 具有少量PNH 克隆,高达12%无骨髓增生异常综合征(myelodysplastic syndrome ,MDS )的AA 患者可出现细胞遗传学异常;排除迟发性遗传性骨髓衰竭性疾病。

再生障碍性贫血诊断及治疗ppt

(Aplastic anemia,AA)

定义

简称再障,是指由于获得性骨髓功能衰竭, 造成全血细胞减少的一种疾病。临床上以红细 胞、粒细胞和血小板减少所致的贫血、感染和 出血为特征。

病因和发病机制

(一)病因 1、原发性:病因不明 2、继发性:

a.生物因素:病毒感染:肝炎病毒、微小病毒B19 b.物理因素:X线、放射性核素 c.化学因素:药物(氯霉素、抗肿瘤药等),工业 用化学物品:苯,除草剂和杀虫剂,染发(氧化染发 剂和金属染发剂)

临床表现

贫血、出血、感染 再障的临床表现与受累细胞系的多少及其程度有关。 患者就诊时多呈中至重度贫血。粒细胞明显减少时,患 者易发生感染并出现不同程度的发热。除皮肤粘膜表浅 感染外,严重粒细胞减少者可发生深部感染如肺炎和败 血症。以细菌感染为常见,亦可见霉菌感染。患者有出 血倾向,主要因血小板减少所致。常见皮肤粘膜出血, 如出血点、鼻衄、齿龈出血、血尿及月经过多等。严重 者可发生颅内出血,是再障的主要死亡原因之一。再障 罕有淋巴结和肝脾肿大。

2、骨髓增生异常综合征(MDS)(病态造血) 3、自身抗体介导的全血细胞减少 4、低增生性白血病(白血病细胞) 5、急性造血功能停滞(回顾性,2-6周恢复) 6、恶性组织细胞病

治疗

(一)、祛除病因(对继发性) (二)、对症、支持疗法:再障的治疗在短期内不 易见效,在治疗本病的药物尚未取效之前,支持疗 法是再障治疗的基本保证

(二)发病机制:目前尚未阐明,可能的机制形象地归纳为 种子(造血干细胞损伤、缺陷)、土壤(造血微环境异常 ) 和虫子(免疫异常)学说。

近年来,很多研究表明,再障患者免疫功能特别是细胞 免疫出现异常,骨髓造血组织(造血干祖细胞)作为靶器官遭 受免疫损伤是再障发病的重要机制。然而,对于异常免疫攻击 的始动以及造血细减少,网织红细胞绝对值减少。 2、一般无肝、脾肿大 3、骨髓多部位增生减低或重度减低(如增生活跃, 需有巨核细胞明显减少),骨髓小粒非造血细胞增 多。 4、除外引起全血细胞减少的其他疾病,如PNH、 MDS、急性造血功能停滞、骨髓纤维化、免疫相关 性全血细胞减少。

再生障碍性贫血诊断与治疗-指南推荐

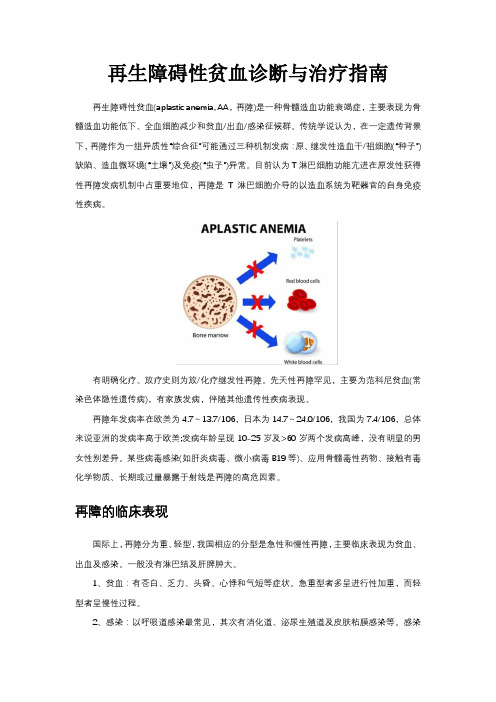

再生障碍性贫血诊断与治疗指南再生障碍性贫血(aplastic anemia, AA,再障)是一种骨髓造血功能衰竭症,主要表现为骨髓造血功能低下、全血细胞减少和贫血/出血/感染征候群。

传统学说认为,在一定遗传背景下,再障作为一组异质性“综合征”可能通过三种机制发病:原、继发性造血干/祖细胞(“种子”)缺陷、造血微环境(“土壤”)及免疫(“虫子”)异常。

目前认为T淋巴细胞功能亢进在原发性获得性再障发病机制中占重要地位,再障是T淋巴细胞介导的以造血系统为靶器官的自身免疫性疾病。

有明确化疗、放疗史则为放/化疗继发性再障。

先天性再障罕见,主要为范科尼贫血(常染色体隐性遗传病),有家族发病,伴随其他遗传性疾病表现。

再障年发病率在欧美为4.7~13.7/106,日本为14.7~24.0/106,我国为7.4/106,总体来说亚洲的发病率高于欧美;发病年龄呈现10-25岁及>60岁两个发病高峰,没有明显的男女性别差异。

某些病毒感染(如肝炎病毒、微小病毒B19等)、应用骨髓毒性药物、接触有毒化学物质、长期或过量暴露于射线是再障的高危因素。

再障的临床表现国际上,再障分为重、轻型,我国相应的分型是急性和慢性再障,主要临床表现为贫血、出血及感染。

一般没有淋巴结及肝脾肿大。

1、贫血:有苍白、乏力、头昏、心悸和气短等症状。

急重型者多呈进行性加重,而轻型者呈慢性过程。

2、感染:以呼吸道感染最常见,其次有消化道、泌尿生殖道及皮肤粘膜感染等。

感染菌种以革兰氏阴性杆菌、葡萄球菌和真菌为主,常合并败血症。

急重型者多有发热,体温在39oC以上,个别患者自发病到死亡均处于难以控制的高热之中。

轻型者高热比重型少见,感染相对易控制,很少持续1周以上。

3、出血:急重型者均有程度不同的皮肤粘膜及内脏出血。

皮肤表现为出血点或大片瘀斑,口腔粘膜有血泡,有鼻衄、龈血、眼结膜出血等。

深部脏器可见呕血、咯血、便血、尿血,女性有阴道出血,其次为眼底出血和颅内出血,后者常危及患者生命。

《2009年版英国再生障碍性贫血诊断与治疗指南》解读 .doc

《2009年版英国再生障碍性贫血诊断与治疗指南》解读同济大学附属同济医院儿科(上海200065)摘要:2009年版英国《再生障碍性贫血诊断与治疗指南》,内容全面、依据充分、观点鲜明、论述详尽、可操作性强,参考价值高,代表了当今国际上有关再障诊治原则与临床方法学等方面的主流观点。

本文重点归纳其中与临床诊治密切相关的内容,并结合临床实践进行适当分析与讨论。

关键词:再生障碍性贫血;指南;诊断标准;免疫抑制治疗;疗效标准[Abstract] The Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Aplastic Anaemia recommended by British Society for Haematology Committee in 2009, was on the basis of fully, opinionated, detailed, strong clinical maneuverability and represented the principle and clinical methodology of diagnosis and treatment of aplastic anemia in the mainstream view of world,has a very high reference value. In this paper, that selected and summarized of the contents closely related to the clinical diagnosis and treatment of aplastic anemia from the Guideline, and Combined with clinical practice for proper analysis and discussion.[Key words] Aplastic anemia;Guideline;Criteria for diagnosis;Immunosuppressive therapy;Criteria for treatment results英国血液学会于2009年出版《再生障碍性贫血诊断与治疗指南(Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of aplastic Anaemia),简称《09版指南》[1],代表了当今国际上有关再障诊治原则与方法学理论的主流观点,临床可操作性强,故具有很高的参考价值。

再生障碍性贫血诊断与治疗中国指南解读PPT课件

心理支持措施

心理咨询

为患者提供心理咨询服务,帮助患者缓解焦虑、抑郁等负面情绪 ,增强治疗信心。

心理干预

针对患者的具体情况,采取认知行为疗法、放松训练等心理干预 措施,改善患者的心理状态。

家属参与

鼓励家属积极参与患者的心理支持工作,提供情感支持和关爱, 共同帮助患者度过难关。

家庭与社会参与

家庭护理

未来发展趋势预测

精准医疗

随着基因测序和生物信息学等技术的发展,未来有望实现再生障碍性贫血的精准诊断和 治疗,提高治疗效果和患者生活质量。

免疫治疗

免疫治疗在再生障碍性贫血治疗中显示出一定疗效,未来可能会有更多针对免疫系统的 治疗方法出现。

多学科协作

再生障碍性贫血的诊疗涉及多个学科,未来需要加强多学科之间的协作和交流,为患者 提供更加全面和个性化的诊疗服务。

指导家属掌握基本的护理技能, 如测量体温、观察病情变化等, 以便在家庭环境中为患者提供必 要的照顾和支持。

社会支持

鼓励患者参加社会活动和互助组 织,与病友交流治疗经验和心得 ,减轻孤独感和无助感。

宣传教育

通过媒体、宣传册等途径向社会 公众普及再生障碍性贫血的相关 知识,提高公众对疾病的认知度 和关注度。

其他检查

根据病情需要,可进行染色体、基因等相关检查。

诊断依据与鉴别诊断

诊断依据

根据病史、体格检查和实验室检查结果综合分析,符合再生障碍性贫血的诊断标准即可确诊。

鉴别诊断

需要与阵发性睡眠性血红蛋白尿、骨髓增生异常综合征等疾病进行鉴别诊断。通过相关实验室检查和临床表现综 合分析,可进行鉴别。

04

治疗原则与方案

出血并发症的预防与处理

预防措施

避免患者接触尖锐物品,防止外伤;定期进 行凝血功能检查,及时发现并处理潜在的凝 血障碍;避免使用影响凝血功能的药物。

再生障碍性贫血诊断与治疗

预防措施

01

02

03

04

避免暴露于有害环境:如辐射 、化学物质等。

积极治疗其他疾病:如自身免 疫性疾病、感染等,以减少对

骨髓造血功能的抑制。

避免滥用药物:特别是可能对 骨髓造血功能有抑制作用的药

物。

遗传咨询和基因检测:对于有 相关病史的家庭,可进行遗传 咨询和基因检测,以了解患病

风险。

护理方法

01

体格检查

检查患者的生命体征,如体温、心率、呼吸等,以评估患者 的全身状况。

检查患者的皮肤、黏膜、淋巴结等部位,以评估患者的贫血 和出血情况。

实验室检查

进行血常规检查,了解患者的红细胞、白细胞、血小板等血液成分的数量和比例。 进行网织红细胞计数、血沉、C反应蛋白等检查,以评估患者的骨髓造血功能。

进行骨髓穿刺检查,了解骨髓的病理学变化。

止痛

对于骨骼疼痛或关节疼痛的患者, 需要使用非甾体类抗炎药或弱阿片 类药物治疗。

免疫抑制治疗

01

02

03

糖皮质激素

可用于急性或慢性再生障 碍性贫血,可抑制免疫反 应,促进造血功能恢复。

环孢素

是一种免疫抑制剂,可以 抑制T细胞活性,减轻免 疫反应。

其他免疫抑制剂

如抗淋巴细胞球蛋白、抗 胸腺细胞球蛋白等,可用 于难治性再生障碍性贫血 患者。

物理治疗

通过物理手段促进血液循环、淋巴回 流,改善组织代谢,如低频脉冲电刺 激、气压治疗等。

运动训练

在医生指导下,进行适当的运动训练 ,如散步、太极拳等,以增强体质和 提高免疫力。

心理辅导

对患者进行心理辅导,帮助其调整心 态,增强信心,促进康复。

预后影响因素和长期生存质量评估

疾病分型与预后

再生障碍性贫血诊断鉴别诊断与治疗护理课件

• 再生障碍性贫血概述 • 诊断 • 治疗 • 护理与康复

01

再生障碍性贫血概述

定义与分类

定义

再生障碍性贫血(AA)是一种由多 种原因引起的骨髓造血功能衰竭症, 导致外周血全血细胞减少,临床上以 贫血、感染和出血为主要表现。

分类

分为急性和慢性两种类型,急性型较 少见,慢性型多见,起病缓慢,病程 较长。

病因与发病机制

病因

包括药物、化学物质、辐射、病 毒感染等,部分患者病因不明。

发病机制

涉及免疫异常、造血干细胞缺陷、 骨髓微环境异常等因素,导致骨 髓造血功能衰竭。

临床表现

01

02

03

04

ห้องสมุดไป่ตู้

贫血

面色苍白、乏力、头晕等。

感染

易发生各种感染,以呼吸道感 染最常见。

出血

皮肤、黏膜及内脏出血,女性 可有月经过多。

治疗

支持治 疗

输血支持

对于贫血、出血严重的患者,定 期输注红细胞和血小板以维持生

命体征。

抗感染治疗

再生障碍性贫血患者免疫力低下, 容易感染,需及时使用抗生素治疗。

营养与饮食

提供高蛋白、高热量、富含维生素 的食物,保证患者的营养需求。

药物治疗

免疫抑制剂

使用环孢素、抗胸腺细胞 球蛋白等药物调节免疫系 统,促进造血功能恢复。

雄激素

如十一酸睾酮等,可刺激 造血功能,促进骨髓造血。

其他药物

如生长因子等,可促进造 血干细胞的增殖分化。

其他治 疗

造血干细胞移植

对于严重或难治性再生障碍性贫血患者,可以考虑进行造血干细胞移植。

细胞因子治疗

再生障碍性贫血诊断和治疗(需要注意问题)

免疫抑制治疗

延长环孢素(>6个月,1年甚或数年)可降低复发,减量应缓慢 环孢素耐药见于为26~62% 患者 PNH、MDS/AML 或实体瘤 11 年时发生率 10%、 8% 和 11% (长期随访) 预防血清病宜用最低剂量激素,以避免股骨头无菌坏死 方案中加入G-CSF(3 ~ 4个月)有助于提高中性粒细胞,但并

鉴别诊断

其他需要鉴别的疾病

▬ 巨幼细胞贫血 ▬ 多毛细胞白血病 ▬ 淋巴瘤伴骨髓纤维化 ▬ 结核分枝杆菌感染

临床治疗

诊断明确 根据病情,制定治疗方案

— 支持治疗 — 非重型再障的治疗 — 重型再障的治疗

临床治疗

支持治疗

♦ 血液制品(将Hb维持在可接受的水平)

— 血小板输注:预防性10×109/L,发热者20×109/L — 血小板同种异体免疫:输注无效 !(去白制品) — 欲行HSCT者,避免家庭成员输血 — 照射血制品:对HSCT候选者和ATG治疗者,有争议

FA = Fanconi anemia DKC = Dyskeratosis congenital SDS = Shwachmann-Diamond syndrome

鉴别诊断

与PNH鉴别

▬ 关系密切,相互转变 ▬ 再障转变为PNH后,贫血可能改善,Rc升高(溶血) ▬ 50%再障有小的PNH克隆 ▬ FCM检查血细胞CD55和CD59(优于Ham试验) ▬ 阴性细胞 5%?, 10%有诊断意义(Neut优于RBC)

鉴别诊断

与低增生性MDS的鉴别

▬ 本质不同,处理原则不同 ▬ 周血幼稚细胞,包括有核红 ▬ 骨髓幼稚细胞,病态造血,ALIP,特别注意小/微巨核 ▬ 病情进展,低增生性MDS有可能是向AL转化前的表现 ▬ 细胞遗传学分析,寻找克隆性证据 ▬ FCM分析,造血干/祖细胞比例

再生障碍性贫血健康宣教手册

再生障碍性贫血健康宣教手册再障的治疗大体可分为支持治疗和疾病针对性目标治疗两部分。

支持治疗的目的是预防和治疗血细胞减少相关的并发症;目标治疗从根本上改善受损的造血干细胞,治疗疾病本身,如异基因造血干细胞移植(allo-SCT)或者免疫抑制治疗(IST),使残存的正常或受损干细胞恢复造血。

再障罕有自愈者,一旦确诊,应明确疾病严重程度,在专业中心进行恰当的处理措施,对疾病治疗开展得越早越好。

新诊断的再障患者,若是重型再障,标准疗法是有HLA相合的同胞供体行同种异体骨髓移植,或联合抗人胸腺细胞免疫球蛋白(ATG)和环孢菌素(cyclosporin A, CsA)的免疫抑制治疗(immunosuppressive therapy, IST)。

近年来,重型再障行HLA相合无关供者移植取得长足进展,可以用于ATG和CsA治疗无效的年轻重型再障患者。

北京协和医院血液内科韩冰骨髓移植或IST前必须控制出血及感染,在感染或未控制出血情况下行骨髓移植或IST风险很大。

感染是再障常见的死因,由于再障患者中性粒细胞缺乏短期之内难以恢复,在有活动性感染,如肺部感染时,行骨髓移植或IST可以为患者提供的造血干/祖细胞,或纠正异常免疫,从而为再障患者赢得恢复造血可能的机会。

延迟移植会加重肺部感染。

1. 支持治疗预防感染应注意饮食及环境卫生,重型再障保护性隔离;避免出血,防止外伤及剧烈活动;杜绝接触危险因素,包括对骨髓有损伤作用和抑制血小板功能的药物;必要的心理护理。

再障患者可以发生细菌、病毒及真菌感染。

重型再障患者由于严重和长期的中性粒细胞减少,可以发生致命性的曲霉菌感染。

对于中性粒细胞<0.2×109/L者需预防性应用抗生素及抗真菌药物并且注意饮食避免细菌及真菌污染。

中性粒细胞(0.2-0.5)×109/L者预防用药利弊尚难确定,依患者既往感染情况而定。

重型再障患者应住院被单独隔离,有条件者可使用层流病房。

再生障碍性贫血诊断与治疗PPT

保持良好的生活习惯,如戒烟、 限酒、保持良好的饮食习惯

定期进行体检,及时发现并治 疗潜在的疾病

加强体育锻炼,提高免疫力

保持良好的生 活习惯,避免 过度劳累和熬

夜

保持良好的饮 食习惯,多吃 富含蛋白质和 维生素的食物

保持良好的心 理状态,避免 过度紧张和焦

虑

定期进行身体 检查,及时发 现并治疗疾病

避免接触有害物 质,如化学品、 辐射等

输血治疗:补充红细胞,改善贫血症状 免疫抑制剂:抑制免疫系统,减少对骨髓的破坏 骨髓移植:重建造血功能,改善病情 药物治疗:使用促红细胞生成素等药物,促进红细胞生成

免疫抑制剂: 如环孢素、他 克莫司等,用 于抑制免疫系 统,减少对骨

髓的破坏

促红细胞生成 素:如EPO、 Darbepoetin 等,用于促进 红细胞的生成

干细胞治疗:适用于病情较轻、药物治疗有效的患者,如造血干细胞移植 等

免疫抑制剂:如环孢素、他克莫司等 造血干细胞移植:适用于病情严重、年龄较轻的患者 基因治疗:通过基因编辑技术,修复造血干细胞中的基因缺陷 辅助治疗:如输血、抗生素、抗病毒等,以改善患者的生活质量和延长生存期

避免接触有毒化学物质和放射 性物质

影像学检查:X线、CT、 MRI等

病理学检查:骨髓活检、淋 巴结活检等

诊断标准:符合诊断标准方 可确诊

血常规检查:观察红细胞、白细胞、 血小板数量变化

骨髓检查:观察骨髓造血功能是否 正常

免疫学检查:检测免疫系统是否异 常

基因检测:检测基因突变情况

临床症状观察:观察患者是否有贫 血、出血、感染等症状

实验室检查:进行其他相关实验室 检查,如肝功能、肾功能等

骨髓检查:观察骨髓增生程度、细胞形态 和比例

再生障碍性贫血专业版PPT模板分享

患者应在医生的指导下进行定期复查 ,包括血常规、肝肾功能、骨髓检查 等,以评估治疗效果和病情变化。

06

再生障碍性贫血的案例分享

个人案例分享一:发现、诊断及治疗过程

1 2

发现

患者在出现持续的乏力、头晕、心悸等症状后, 去医院进行了血常规检查,结果显示贫血、血小 板减少、白细胞减少。

诊断

经过骨髓穿刺检查,医生确诊为再生障碍性贫血 。

再生障碍性贫血

汇报人: 2023-12-12

目 录

• 再生障碍性贫血概述 • 再生障碍性贫血的症状与诊断 • 再生障碍性贫血的治疗方法 • 再生障碍性贫血的预防与护理 • 再生障碍性贫血的康复与预后 • 再生障碍性贫血的案例分享

01

再生障碍性贫血概述

定义和分类

定义

再生障碍性贫血是一种骨髓造血功能 衰竭症,表现为造血干细胞和祖细胞 数量减少、骨髓造血功能衰竭,进而 导致全血细胞减少。

健康生活方式

鼓励患者保持健康的生活方式, 包括均衡饮食、适量运动、规律 作息等,以增强身体免疫力和抵

抗力。

社会支持

为患者提供社会支持,如亲友的 关心、社区组织的帮助等,让他

们感受到社会的温暖和关爱。

预后影响因素

病情严重程度

患者的病情严重程度是影响预后的主要因素之一。轻度再障患者康 复预后较好,而重度再障患者病情较重,康复预后相对较差。

如辛辣、油腻、生冷、过热等刺激性食物和饮料,以免刺激胃

肠道,影响病情恢复。

规律作息,保证充足睡眠

03

良好的作息习惯有助于身体的恢复,应保证每天有足够的睡眠

时间。

05

再生障碍性贫血的康复与预后

康复期的生活质量保障

心理疏导

再生障碍性贫血的诊断和治疗指南

再生障碍性贫血的诊断和治疗指南

英国血液学标准委员会;贺冠强;吴学琼;刘文励;孙汉英

【期刊名称】《国际输血及血液学杂志》

【年(卷),期】2009(032)004

【摘要】重要推荐小结:再生障碍性贫血是一种少见的异质性疾病,由于病因不明,大约70%-80%被认为是原发性疾病,少数病例是由药物或感染引起的骨髓衰竭/再生障碍性贫血。

大约有15%-20%的患者表现为遗传发病,其有家族性发病和/或伴随其他遗传性疾病史。

仔细询问病史及体格检查对于排除遗传因素至关重要。

【总页数】10页(P356-365)

【作者】英国血液学标准委员会;贺冠强;吴学琼;刘文励;孙汉英

【作者单位】(Missing);430030,武汉,华中科技大学同济医学院附属医院;430030,武汉,华中科技大学同济医学院附属医院;(Missing);(Missing)

【正文语种】中文

【相关文献】

1.2010欧洲心脏病协会年会心脏起搏和再同步治疗指南更新——2007欧洲心脏病协会年会心脏再同步化治疗指南疗指南和2008欧洲心脏病协会年会急性和慢性心力衰竭诊断和治疗指南的更新

2.2015年美国疾病控制中心性传播疾病的诊断和治疗指南(续)--淋病的诊断和治疗指南

3.2015年美国疾病控制中心性传播疾病诊断和治疗指南(续)--梅毒的诊断和治疗指南

4.2015年美国疾病控制中心性传

播疾病诊断和治疗指南(续)--生殖器疱疹的诊断和治疗指南5.2015年美国疾病控制中心性传播疾病诊断和治疗指南(续)--盆腔炎的诊断和治疗指南

因版权原因,仅展示原文概要,查看原文内容请购买。

再生障碍性贫血的诊断提示及治疗措施

再生障碍性贫血的诊断提示及治疗措施再生障碍性贫血(aplasticanemia)简称再障,系由多种原因所致的骨髓造血功能障碍、周围全血细胞减少,但不伴骨髓异常浸润和骨髓网硬蛋白增多的一种综合病症。

临床上以严重进行性贫血、广泛出血、反复感染、全血细胞减少为特征,骨髓检查对诊断有重要价值。

【诊断提示】(1)周围血象:全血细胞减少(至少符合下列两项:①HbVIOog/L;②血小板<100X10。

/L;③中性粒细胞V1.5×10o/L),网织红细胞绝对值减少,网织红细胞计数V0.05o(2)一般无肝脾大。

可有广泛出血,易感染。

(3)骨髓象:增生低下(至少一个部位增生减低或重度减低)。

典型病例粒系、红系和巨核细胞明显减少,淋巴细胞比例增高,非造血细胞或脂肪粒增多(有条件者应做骨髓活检)。

(4)骨髓活检:造血组织减少,脂肪组织增加,可伴有不同程度的脂肪液化和坏死,典型病例可见残存的孤立性幼红细胞岛(簇),成纤维细胞不增生。

(5)排除引起全血细胞减少的其他疾病,如巨幼细胞性贫血、系统性红斑狼疮、阵发性睡眠性血红蛋白尿、骨髓增生异常综合征、急性造血功能停滞、骨髓纤维化、急性白血病、恶性组织细胞病、脾功能亢进等。

(6)一般抗贫血治疗无效。

【诊断标准】1.急性再障的诊断标准(重型再障)(1)临床:发病急,贫血呈进行性加剧,常伴有严重感染、内脏出血。

(2)血象:血红蛋白下降速度快;网织红细胞VO.Ol,绝对值V15X1(Γ/L,白细胞明显减少,中性粒细胞绝对值<0.5×10o/L;血小板V2OX1()9/L o极重型再障中性粒细胞V0.2X109/Lo(3)骨髓象:骨髓多部位增生减低,三系造血细胞明显减少,有核细胞比例少于25%,非造血细胞增多,如增生活跃须有淋巴细胞增多。

骨髓小粒非造血细胞增多。

2.慢性再障的诊断标准(非重型再障)(1)临床:发病慢,以贫血为主,感染、出血较轻。

(2)血象:血红蛋白下降速度较慢,网织红细胞、白细胞、中性粒细胞及血小板值较急性型为高。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

《2009年版英国再生障碍性贫血诊断与治疗指南》解读谢晓恬同济大学附属同济医院儿科(上海200065)摘要:2009年版英国《再生障碍性贫血诊断与治疗指南》,内容全面、依据充分、观点鲜明、论述详尽、可操作性强,参考价值高,代表了当今国际上有关再障诊治原则与临床方法学等方面的主流观点。

本文重点归纳其中与临床诊治密切相关的内容,并结合临床实践进行适当分析与讨论。

关键词:再生障碍性贫血;指南;诊断标准;免疫抑制治疗;疗效标准[Abstract] The Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Aplastic Anaemia recommended by British Society for Haematology Committee in 2009, was on the basis of fully, opinionated, detailed, strong clinical maneuverability and represented the principle and clinical methodology of diagnosis and treatment of aplastic anemia in the mainstream view of world,has a very high reference value. In this paper, that selected and summarized of the contents closely related to the clinical diagnosis and treatment of aplastic anemia from the Guideline, and Combined with clinical practice for proper analysis and discussion.[Key words] Aplastic anemia;Guideline;Criteria for diagnosis;Immunosuppressive therapy;Criteria for treatment results英国血液学会于2009年出版《再生障碍性贫血诊断与治疗指南(Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of aplastic Anaemia),简称《09版指南》[1],代表了当今国际上有关再障诊治原则与方法学理论的主流观点,临床可操作性强,故具有很高的参考价值。

正如《09版指南》所述,再障发病率低,又存在高度异质性,起病也明显受到不同人群遗传背景、生活环境和方式等因素的多方面影响,故难以获得充分的大样本前瞻性研究资料,使诊疗标准的制定难度较大。

可见,以英国学者一贯的严谨作风,制定既符合现代研究理论,又能够达成临床普遍共识的“诊疗指南”实属难能可贵,非常值得认真阅读与参照实践。

现将本人学习《09版指南》后的初步认识,结合既往经验体会汇报如下。

1 指南要点归纳《09版指南》篇幅甚大,诊治原则与实施细节均面面俱到,以询证医学的方法提出对于临床规范诊治具有重要参考价值的关键内容,并适当澄清以往某些争议或认识误区。

为方便临床参照,我认为还是很有必要以足够的篇幅加以归纳罗列与介绍。

1.1 再障定义再障表现为全血细胞降低,骨髓造血细胞减少或缺乏,但无骨髓异常细胞浸润和纤维化,并能除外射线或化疗,以及其他可能导致全血细胞下降的疾病。

能除外先天性再障者,为获得性再障。

后者大多数为病因不明的原发性再障,《09版指南》主要针对于获得性再障。

由于亚洲地区再障发病率约为欧美国家的2~6倍,且再障病例中获得性再障所占百分率(约95%)明显高于欧美国家(约70~80%),儿童也为高发年龄段[1],因此《09版指南》对于我国儿童再障的规范诊治具有非常显著的指导意义。

1.2 诊断步骤完整的再障诊断,需要具备下列诸多临床条件,包括外周血象和骨髓检查显示符合再障特征,且能除外可导致外周血三系下降的其它疾病,以及明确疾病严重程度、区分类型(先天性、获得性)和可能病因等(参见图1)。

1.2.1 基本条件符合再障诊断的外周血象,至少具备下列3项中的2项:①血红蛋白(Hb)<100 g/L;②中性粒细胞绝对计数(ANC)<1.5×109/L;③血小板(Plt)<50×109/L。

但早期可仅显一系减少,且通常为血小板减少。

1.2.2 骨髓检查骨髓涂片显示红系、粒系和巨核细胞减少,淋巴细胞百分率增高,浆细胞和巨噬细胞等非造血细胞增多。

要求必须进行骨髓活检,以避免骨髓涂片穿刺于“局部增生灶”而漏诊,并有助于发现异常细胞浸润,以利鉴别诊断。

1.2.3 鉴别诊断在确诊再障之前,必须除外可能导致全血细胞下降和骨髓造血细胞减少的其它疾病,主要鉴别诊断包括:①骨髓异常增生综合征(MDS):髓系和巨核细胞出现成熟障碍或原始细胞增高等病态造血表现、骨髓活检见残余造血区域中网状蛋白增多、7号染色体异常及胎儿血红蛋白(HBF)增高等现象,均为除外再障,并诊断MDS的重要证据。

但红系病态造血及未成熟前体细胞异常定位(ALIP),并不足以鉴别再障与MDS。

②白血病:骨髓检查可发现细胞形态学异常,典型肿瘤细胞免疫表型,均为与再障的鉴别要点。

③免疫性血小板减少性紫癜(ITP):《09版指南》特别强调,由于再障早期常可见仅血小板一系下降,易被误诊为ITP。

但再障和ITP骨髓检查表现差异显著,提示在诊断ITP时,应该进行骨髓检查。

④夜间阵发性血红蛋白尿(PNH):在避免近期输血的条件下,采用流式细胞仪检测CD55和CD59以助诊断。

⑤营养性贫血:如检查发现存在维生素B12或叶酸严重缺乏,需要营养补充纠正后再行复查。

⑥自身免疫性疾病:抗核抗体和抗DNA抗体等表达阳性,罕见骨髓造血细胞明显减少。

1.2.4 程度分型目前仍沿用Camitta于1975年推荐的重型再障(SAA)诊断标准[2]和Bacigalupo于1988年提出的关于极重型再障(VSAA)标准[3],见表2。

表 2 再障严重程度诊断分型标准SAA 骨髓:有核细胞百分率 <25%;或25%~50%(但残存的造血细胞 <30%)血象:同时具备下列3项中的2项或2项以上:ANC < 0.5×109/LPlt < 20×109/LARC < 20×109/LVSAA 达到SAA标准,但ANC <0.2×109/LNSAA* 未达到SAA和VSAA诊断标准者* ARC:网织红细胞绝对计数(actual reticulocyte count)** NSAA:非重型再障(non-severe aplastic anemia)1.2.5 性质分类确诊再障之后,需要区分先天性再障和获得性再障。

常见先天性再障为范可尼贫血(Fanconi anaemia,FA)和先天性角化不良(Dyskeratosis Congenita,DC)等。

FA常见躯体或内脏畸形及智力发育障碍,必须行染色体丝裂霉素断裂实验以确诊或除外。

DC患者多见皮肤、黏膜与趾(指)甲异常,必要时可进行端粒长度和端粒酶等相关检测。

在除外先天性再障之后,其余病例均可归类于后天获得性再障。

1.2.6 病因诊断原则上能够找到导致再障的确切病因者为继发性再障。

但以往认为可能导致再障的药物(如氯霉素)和化学物质,在目前均尚未能有确切的依据,导致肝炎相关再障(HAAA)的多为非已知的血清型肝炎,EB病毒等感染性疾病与再障的关系也远未明确。

因此,绝大多数获得性再障为原因不明的原发性再障。

1.2.7 相关检测项目归纳为完成上述诊断与鉴别,分类与分型的目标,初诊病例常规检测项目包括:①全血常规+血细胞形态;②骨髓涂片+活检;③肝功能与相关病毒学检测(肝炎病毒、EBV等);④血清维生素B12与叶酸水平;⑤自身抗体(抗核抗体和抗DNA抗体);⑥流式细胞仪检测CD55和CD59;⑥细胞遗传学,如染色体核型与丝裂霉素染色体断裂实验;⑦胎儿血红蛋白;⑧必要的影像学检查,如胸部X线(但不能采用全身X检查以图发现FA的骨骼畸形);腹部B超,观察有无肝脾或深部淋巴结肿大,也能及时发现FA患儿常见的肾脏畸形(移位或缺失)。

图2 获得性再障诊断步骤1.3 治疗方法与选择原则-目前,获得性再障的有效治疗方法主要为异基因造血干细胞移植(allo-HSCT)和抗胸腺细胞球蛋白(ATG)联合环孢菌素A(CSA)的免疫抑制疗法(IST)。

《09版指南》非常肯定有关获得性再障的“免疫介导”致病机制理论,并根据以往临床研究和相关权威专家论述[4-5],将IST作为无法进行全相合同胞供者移植的再障患者的首选药物疗法,参见图2。

1.3.1 allo-HSCT:①HLA全相合同胞供体移植(MSD):被推荐作为≤40岁的SAA或VSAA,以及依赖成分输血儿童NSAA的首选疗法。

并提出应该采用骨髓移植(BMT)的方式。

②HLA全相合无关供体移植(MUD):因存在较高临床风险和GVHD发生率与程度[[4-7]],故《09版指南》仍明确建议,MUD移植要求供受体HLA的Ⅰ类和Ⅱ类抗原全相合,且应用于至少1个疗程IST无效的SAA或VSAA。

③脐带血移植(CBSCT):因目前国际相关资料与经验有限,故未作详细介绍。

1.3.2 IST:ATG联合CSA已被认为是标准的IST疗法,并被作为SAA和VSAA,以及依赖成分输血或疾病趋于进展的儿童NSAA,在不具有MSD移植条件时的首选药物疗法。

①ATG:推荐R-ATG为首选剂型,并详细提出ATG治疗相关过敏反应、严重出血、血清病和感染等常见不良反应防治细则,值得临床认真参照。

②CSA:口服剂量5mg/kg•d,维持CSA血谷浓度于成人150~250μg/L。

提出儿童维持高水平血浓度并未能提高疗效,但可增加不良反应发生率,故建议儿童CSA血谷浓度以100~150μg/L为宜。

同时强调CSA的长疗程与慢减量原则。

图1 儿童再障治疗方法选择原则示意图1.4 辅助与支持治疗1.4.1 成分输血指征:血小板输注指征为外周血Plt < 10×109/L(处于感染发热状态时,Plt < 20×109/L)。

酌情红细胞输注,以争取维持于外周血Hb>80 g/L。

对于近期接受BMT或IST治疗者,需对供血进行射线处理。

1.4.2 雄性激素地位:虽然肯定了雄性激素的疗效,但充分考虑到可能导致明显肝脏损害和男性化等不良反应,故仅推荐用于IST无效或无法接受IST的患者。