Fordham Law Review1 (2)

法学类外文核心期刊(中英文)

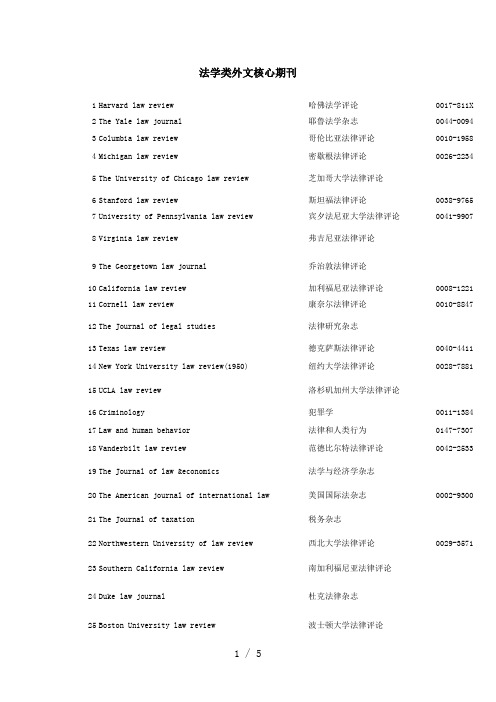

法学类外文核心期刊1 Harvard law review 哈佛法学评论0017-811X2 The Yale law journal 耶鲁法学杂志0044-00943 Columbia law review 哥伦比亚法律评论0010-19584 Michigan law review 密歇根法律评论0026-22345 The University of Chicago law review 芝加哥大学法律评论6 Stanford law review 斯坦福法律评论0038-97657 University of Pennsylvania law review 宾夕法尼亚大学法律评论0041-99078 Virginia law review 弗吉尼亚法律评论9 The Georgetown law journal 乔治敦法律评论10 California law review 加利福尼亚法律评论0008-122111 Cornell law review 康奈尔法律评论0010-884712 The Journal of legal studies 法律研究杂志13 Texas law review 德克萨斯法律评论0040-441114 New York University law review(1950) 纽约大学法律评论0028-788115 UCLA law review 洛杉矶加州大学法律评论16 Criminology 犯罪学0011-138417 Law and human behavior 法律和人类行为0147-730718 Vanderbilt law review 范德比尔特法律评论0042-253319 The Journal of law &economics 法学与经济学杂志20 The American journal of international law 美国国际法杂志0002-930021 The Journal of taxation 税务杂志22 Northwestern University of law review 西北大学法律评论0029-357123 Southern California law review 南加利福尼亚法律评论24 Duke law journal 杜克法律杂志25 Boston University law review 波士顿大学法律评论26 American Journal of Law & Medicine 美国法律与医学杂志 0098-8588 27 Minnesota law review明尼苏达法律评论 0026-553528Journal of criminal law and criminology(Baltimore,MD:1975) 刑法与犯罪学杂志29 Fordham law review福特哈姆法律评论 0015-704X30 The George Washington law review 乔治华盛顿法律评论31 Law & society review 法律与社会评论 0023-9216 32 Journal of medical ethics医学伦理学杂志0306-6800 33 The Journal of law, economics & organization 法学、经济学与组织学杂志 8756-6222 34 Harvard journal on legislation哈佛立法杂志 0017-808X35 Indiana law journal(Indianapolis, Ind :1926)印第安纳法律杂志36 The Journal of research in crime and delinquency 犯罪与少年犯罪研究杂志37 Harvard journal of law &public policy 哈佛法律和公共政策杂志 0193-487238 The British journal of criminology 英国犯罪学杂志 39 Medicine,science, and the law 医学、科学与法律40 The Business lawyer商务律师0007-6899 41 International journal of law and psychiatry 国际法律与精神病学杂志 0160-2527 42 Ecology law quarterly生态法季刊0046-112143 University of Illinois law review 伊利诺斯大学法律评论 44 The journal of clinical ethics 临床伦理学杂志 45 Iowa law review依阿华法律评论 46 Washington law review(Seattle, Wash :1967) 华盛顿法律评论47 Harvard civil rights-civil liberties law review 哈佛公民权利—公民自由法律评论 0017-8039 48 Criminal justice and behavior 刑事审判与犯罪行为49 Wisconsin law review 威斯康星法律评论 0043-650X50 Administrative law review行政管理法评论51 Judicature 司法0022-580052 Crime and delinquency 犯罪与少年犯罪53 Criminal law review(London,England) 刑法评论54 Law & social inquiry 法律与社会调查0897-654655 Psychology,public policy, and law 心理学、公共政策与法律56 The American criminal law review 美国刑法评论57 University of Pittsburgh law review 匹兹堡大学法律评论0041-991558 The Washington quarterly 华盛顿季刊0163-660X59 The Journal of forensic psychiatry 法庭精神病学杂志0958-518460 The Journal of law ,medicine & ethics 法律、医学与伦理学杂志61 Journal of legal education 法律教育杂志62 Behavioral sciences & the law 行为科学与法律0735-393663 The American journal of comparative law 美国比较法杂志0002-919X64 Family law quarterly 家庭法季刊65 Harvard international law journal 哈佛国际法杂志0017-806366 Food and drug law journal 食品与药物法杂志67 Common Market law review 共同市场法律评论68 International review of law and economics 国际法律与经济学评论69 Journal of criminal justice 刑事审判杂志70 Journal of maritime law and commerce 海事法与商业杂志0022-241071 Louisiana law review 路易斯安那法律评论0024-685972 The American bankruptcy law journal 美国破产法杂志0027-904873 Federal probation 联邦缓刑制74 The Columbia journal of transnational law 哥伦比亚跨国法律杂志0010-193175 Buffalo law review 布法罗法律评论 76 The Banking law society 银行法杂志77 Journal of law and society法律与社会杂志0263-323X78 Columbia journal of law and social problem 哥伦比亚大学法律与社会问题杂志 79 Denver University law review 丹佛大学法律评论 0883-940980 Law library journal 法学图书馆杂志81 Law and philosophy法律与哲学 0167-5249 82 Journal of legal medicine(Chicago,III) 法医杂志 0194-7648 83 Law and contemporary problems 法律与当代问题 0023-918684 Social & legal studies 社会与法律研究85 Issues in law & medicine法学和医学问题8756-816086 The Australian & New Zealand journal of criminology 澳大利亚和新西兰犯罪学杂志87 International journal of the sociology of law 国际法律社会学杂志 0194-659588 Ocean development and intenational law 海洋开发与国际法 89 The American journal of legal history 美国法律史杂志 90 Cornell international law journal 康奈尔国际法杂志91 American business law journal美国商法杂志 0002-776692 Stanford journal of international law 斯坦福国际法杂志93 Psychology, crime & law心理学、犯罪与法律 1068-316X94 The Tort & insurance law journal 民事侵权与保险法杂志95 Crime, law and social change犯罪、法律和社会变革 0925-499496 University of Louisville journal of family law路易斯维尔大学家庭法杂志97University of Pennsylvania journal of international economic law 宾夕法尼亚大学国际国际经济法杂志98 Copyright world 版权界99 Journal of international banking law 国际银行法杂志100 California lawyer 加利福尼亚律师101 Securities regulation law journal 证券管理法律杂志102 Houston law review 休斯敦法律评论103 Journal of the Copyright Society of the USA 美国版权学会杂志104 Kentucky law journal(Lexington,Ky.) 肯塔基法律杂志105 Annual review of banking law 银行法评论年刊106 Indiana law review 印第安那法律评论107 University of Kansas law review 堪萨斯大学法律评论0083-4025 108 North Carolina law review 北卡罗来纳法律评论109 South Carolina law review 南卡罗来纳法律评论110 Labor law journal 劳动法杂志0023-6586 111 New England law review 新英格兰法律评论112 American journal of family law 美国家庭法杂志0891-6330 113 The Australian law journal 澳大利亚法律杂志114 Southern illinois University law journal 南伊利诺斯大学法律杂志0145-3432 115 Chinese law and government 中国法律和政府0009-4609 116 Russian politics and law 俄罗斯政治与法律[文档可能无法思考全面,请浏览后下载,另外祝您生活愉快,工作顺利,万事如意!]。

霍姆斯读本

在一个人实际做决定时,还有很多需要考虑的次要因素,比如一副好嗓子、坚强的性格和良好的关系。但我并不认为一个辉煌的开始有多么重要;毕竟这一战役最终将取决于一个人与生俱来的能力。我们自身的能力是预先注定的,在人们共同生活的巨大动荡里,绝大多数人迟早会找到他们所属的位置。如果你选择了的话,那么这就是你的命运,但人命运的一部分以及那个必然结果所必须经历的手段就是奋斗。在某种意义上,一个人想要的就是他能得到的。

坏人会利用一切阶级偏见、卑劣的嫉妒或者低俗的怀疑来唤醒他的倾听者,以使他们倒向他那一边。高尚的人则会揭示出人们心中从未被怀疑过的渴望的力量,让崇高而宽宏的思想高高飞翔,并用翅膀载着他们越过前进道路上的沟沟壑壑。可无论好坏,一个善于说服的人都有办法辨别他所要应对的种种天性,并且通过某种直觉感到它们更容易朝哪些方向流动,以及它们将会在哪里改变方向。

这虽然是他最先感到需要的能力,却不是最重要的能力。法律人学习法律不像一个男孩学习拉丁语语法或者数学那样是为了背诵,而是为了使用,并且将其作用于他从真实生活中得到的那些规则上。他的工作是在法庭上审理案件,并且告诉人们如何防范和解决纠纷。他读书是为了以正确的方式咨询和审理他的案件。

于是我们马上可以看出,读书只不过是开始。一个人可能在读书方面很笨拙,但如果他能告诉另一个处于痛苦中的人应当怎样做,他就具备了更重要的一半能力。如果他能从冲动的证人或者委托人向他倾泻的戏剧化情境的汪洋大海中立刻抓住那些重要的事实,他就能找到许多能帮他从图书馆里得到他想要的东西的学生。

他灵魂的欲望就是他命运的先知。

第一部分 3.法律,我们的情人

法律,我们的情人

(OurMistress,TheLaw)

萨弗尔克(Suffolk)律师协会的晚餐演讲,1885年2月5日。

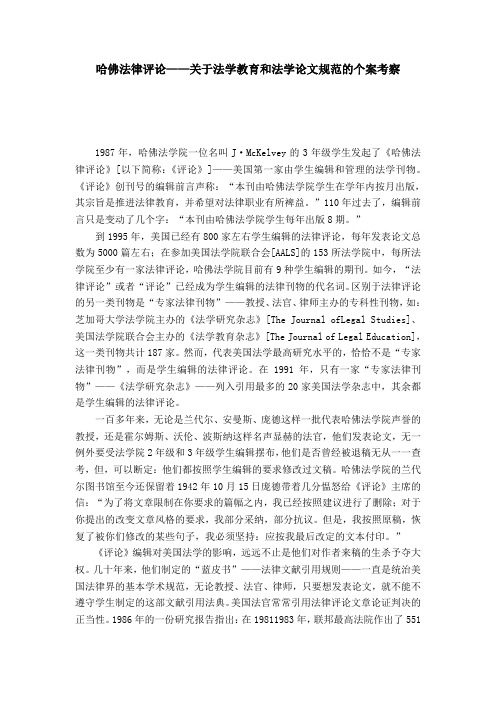

哈佛法律评论——关于法学教育和法学论文规范的个案考察

哈佛法律评论——关于法学教育和法学论文规范的个案考察1987年,哈佛法学院一位名叫J·McKelvey的3年级学生发起了《哈佛法律评论》[以下简称:《评论》]——美国第一家由学生编辑和管理的法学刊物。

《评论》创刊号的编辑前言声称:“本刊由哈佛法学院学生在学年内按月出版,其宗旨是推进法律教育,并希望对法律职业有所裨益。

”110年过去了,编辑前言只是变动了几个字:“本刊由哈佛法学院学生每年出版8期。

”到1995年,美国已经有800家左右学生编辑的法律评论,每年发表论文总数为5000篇左右;在参加美国法学院联合会[AALS]的153所法学院中,每所法学院至少有一家法律评论,哈佛法学院目前有9种学生编辑的期刊。

如今,“法律评论”或者“评论”已经成为学生编辑的法律刊物的代名词。

区别于法律评论的另一类刊物是“专家法律刊物”——教授、法官、律师主办的专科性刊物,如:芝加哥大学法学院主办的《法学研究杂志》[The Journal ofLegal Studies]、美国法学院联合会主办的《法学教育杂志》[The Journal of Legal Education],这一类刊物共计187家。

然而,代表美国法学最高研究水平的,恰恰不是“专家法律刊物”,而是学生编辑的法律评论。

在1991年,只有一家“专家法律刊物”——《法学研究杂志》——列入引用最多的20家美国法学杂志中,其余都是学生编辑的法律评论。

一百多年来,无论是兰代尔、安曼斯、庞德这样一批代表哈佛法学院声誉的教授,还是霍尔姆斯、沃伦、波斯纳这样名声显赫的法官,他们发表论文,无一例外要受法学院2年级和3年级学生编辑摆布,他们是否曾经被退稿无从一一查考,但,可以断定:他们都按照学生编辑的要求修改过文稿。

哈佛法学院的兰代尔图书馆至今还保留着1942年10月15日庞德带着几分愠怒给《评论》主席的信:“为了将文章限制在你要求的篇幅之内,我已经按照建议进行了删除;对于你提出的改变文章风格的要求,我部分采纳,部分抗议。

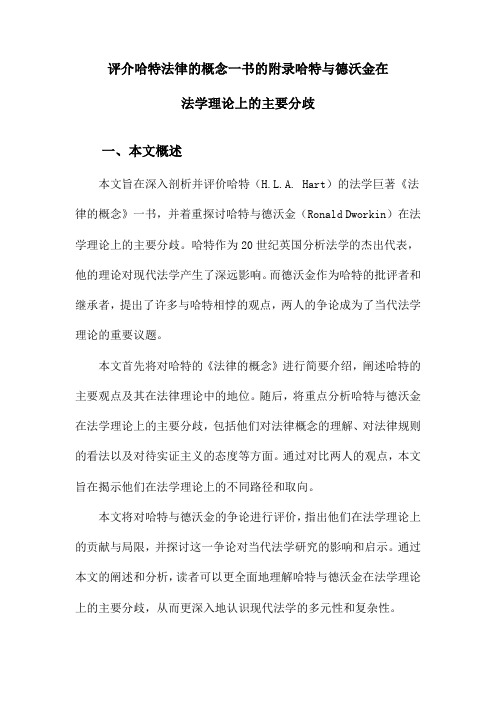

评介哈特法律的概念一书的附录哈特与德沃金在法学理论上的主要分歧

评介哈特法律的概念一书的附录哈特与德沃金在法学理论上的主要分歧一、本文概述本文旨在深入剖析并评价哈特(H.L.A. Hart)的法学巨著《法律的概念》一书,并着重探讨哈特与德沃金(Ronald Dworkin)在法学理论上的主要分歧。

哈特作为20世纪英国分析法学的杰出代表,他的理论对现代法学产生了深远影响。

而德沃金作为哈特的批评者和继承者,提出了许多与哈特相悖的观点,两人的争论成为了当代法学理论的重要议题。

本文首先将对哈特的《法律的概念》进行简要介绍,阐述哈特的主要观点及其在法律理论中的地位。

随后,将重点分析哈特与德沃金在法学理论上的主要分歧,包括他们对法律概念的理解、对法律规则的看法以及对待实证主义的态度等方面。

通过对比两人的观点,本文旨在揭示他们在法学理论上的不同路径和取向。

本文将对哈特与德沃金的争论进行评价,指出他们在法学理论上的贡献与局限,并探讨这一争论对当代法学研究的影响和启示。

通过本文的阐述和分析,读者可以更全面地理解哈特与德沃金在法学理论上的主要分歧,从而更深入地认识现代法学的多元性和复杂性。

二、哈特法律的概念概述哈特,作为20世纪最杰出的法律哲学家之一,他的法学理论对后世产生了深远的影响。

在《法律的概念》一书中,哈特对法律的定义、规则、原则等进行了深入探讨,提出了独特的法律理论。

哈特强调法律规则的开放性结构,认为法律并非只是由明确的规则构成,还包括了原则、政策和标准等更为灵活的元素。

这种理解打破了传统法学中法律被视为封闭、固定体系的观念,使得法律更加适应社会的变化和发展。

哈特还提出了“内在观点”和“外在观点”的区分,以解释人们对法律规则的接受和遵守。

内在观点认为人们应当从内部理解并接受法律规则,而外在观点则强调法律规则对社会成员的外部强制力。

这种区分有助于理解法律规则的双重性质,即既具有内在的道德合理性,又具有外在的强制力。

哈特的理论在法律哲学界引起了广泛的讨论和争议。

他的观点挑战了传统法学的权威,为法学研究提供了新的视角和方法。

FordhamLawReview1(2)

FordhamLawReview1(2)投资条约仲裁的合法性危机——通过不一致决定使国际公法私有化引言1995年以前,只有少量的仲裁涉及投资条约下的权利,然而在过去的5年时间里,案件的数量急剧上升。

目前,超过60起有名仲裁涉及投资条约,并且这些索赔主要涉及的金额从1亿2千万美元到成千上万亿美元。

这一增长在不同组的个人做出关于法律相同点上相互冲突的决定之前,使得有经济和政治后果的公共问题的决定被私下解决,并且没有任何一个机构有能力去解决这些相互冲突的决定。

在过去的12年里,国家之间已经签订了大约1500个新的双边投资条约,并且约有5个多边投资条约为了吸引外资而授予外国投资者广泛的投资权利,并创造了投资纠纷解决途径的灵活性。

这一广泛的相互关联的权利关系网的存在意味着当困难不可避免的出现时,已经有了一个解决投资纠纷机制的拼凑物。

一些国际公法权利已经第一次在投资条约中清楚地被表达出来了,例如“公平平等”待遇的权利以及主权国家遵守承诺的义务。

法庭运用了这些标准不一致,并且做出了有分歧的责任判决。

通过仲裁解决投资纠纷的程序正创造着关于那些权利以及国际公法的意义的不稳定性,而不是为外国投资者和国家创造可靠性。

当投资仲裁仍然在它的起始阶段而不是它第一次成长痛苦的中期时,帮助法学发展、认识到目前体制的困难,并且找出办法使令人担忧的合法性危机降到最低,这些都是合适的。

通过这种方式,投资仲裁就不会像臭名昭著的洗澡水一样被人们抛弃,并且国际仲裁将确定会沿着促进国际公平的道路发展。

这篇文章的第一部分描述了投资条约的历史性和合法性框架,与这一背景相对,这篇文章的第二部分考察了投资条约仲裁的产生。

第三部分中,这篇文章讨论了目前可能提出的不一致的决定的补救方法。

第四部分描述了主要的三组不一致的决定,这三组决定已经引起了关于投资条约权利含义的不确定性。

这篇文章的第五部分回顾了文献作品、考虑了合法性的指标并且提供了一项新的分析先前改良建议的框架。

(完整word版)哈佛大学公开课《公平与正义》第2集中英文字幕

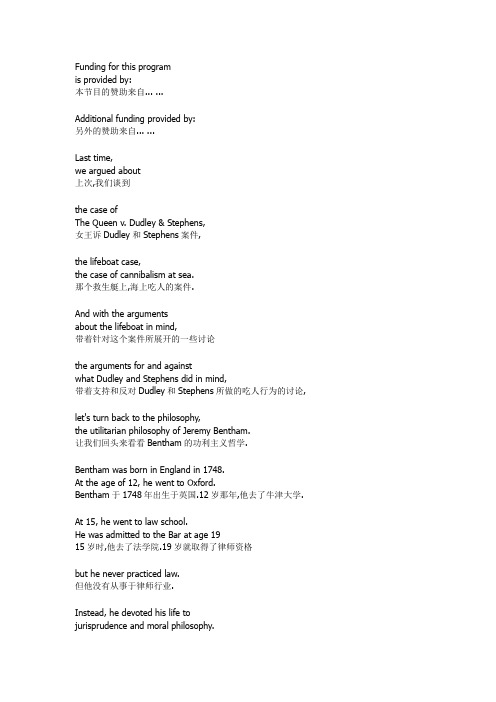

Funding for this programis provided by:本节目的赞助来自... ...Additional funding provided by:另外的赞助来自... ...Last time,we argued about上次,我们谈到the case ofThe Queen v. Dudley & Stephens,女王诉Dudley和Stephens案件,the lifeboat case,the case of cannibalism at sea.那个救生艇上,海上吃人的案件.And with the argumentsabout the lifeboat in mind,带着针对这个案件所展开的一些讨论the arguments for and againstwhat Dudley and Stephens did in mind,带着支持和反对Dudley和Stephens所做的吃人行为的讨论, let's turn back to the philosophy,the utilitarian philosophy of Jeremy Bentham.让我们回头来看看Bentham的功利主义哲学.Bentham was born in England in 1748.At the age of 12, he went to Oxford.Bentham于1748年出生于英国.12岁那年,他去了牛津大学. At 15, he went to law school.He was admitted to the Bar at age 1915岁时,他去了法学院.19岁就取得了律师资格but he never practiced law.但他没有从事于律师行业.Instead, he devoted his life tojurisprudence and moral philosophy.相反,他毕生致力于法理学和道德哲学.Last time, we began to considerBentham's version of utilitarianism.上一次,我们开始考虑Bentham版本的功利主义. The main idea is simply statedand it's this:简单来说其主要思想就是:The highest principle of morality,whether personal or political morality,道德的最高原则,无论个人或政治道德,is to maximize the general welfare,or the collective happiness,就是将公共福利,或集体的幸福最大化,or the overall balanceof pleasure over pain;或在快乐与痛苦的平衡中倾向快乐;in a phrase, maximize utility.简而言之就是,功利最大化.Bentham arrives at this principleby the following line of reasoning:Bentham是由如下推理来得出这个原则的:We're all governedby pain and pleasure,我们都被痛苦和快乐所控制,they are our sovereign masters,and so any moral system他们是我们的主宰,所以任何道德体系has to take account of them.都要考虑到这点.How best to take account?By maximizing.如何能最好地考虑这一点?通过最大化.And this leads to the principle of thegreatest good for the greatest number.从此引出的的原则就是将最大利益给最多数的人的.What exactly should we maximize?我们究竟该如何最大化?Bentham tells us happiness,or more precisely, utility -Bentham告诉我们幸福,或者更准确地说,实用- maximizing utility as a principlenot only for individuals最大化效用作为一个原则不仅适用于个人but also for communitiesand for legislators.而且还适用于社区及立法者."What, after all, is a community?"Bentham asks.“毕竟,什么是社区?”Bentham问道.It's the sum of the individualswho comprise it.它是构成这个社区的所有个体的总和.And that's why in decidingthe best policy,这就是为什么在决定最好的政策,in deciding what the law should be,in deciding what's just,在决定法律应该是什么样,在决定什么是公正时, citizens and legislatorsshould ask themselves the question公民和立法者应该问自己的问题if we add up all of the benefitsof this policy如果我们把这项政策所能得到的所有利益and subtract all of the costs,the right thing to do减去所有的成本,正确的做法is the one that maximizes the balanceof happiness over suffering.就是将幸福与痛苦之间的平衡最大化地倾向幸福. That's what it meansto maximize utility.这就是效用最大化.Now, today, I want to seewhether you agree or disagree with it,现在,我想看看你们是否同意它,and it often goes,this utilitarian logic,往往有云:功利主义的逻辑,under the name ofcost-benefit analysis,名为成本效益分析,which is used by companiesand by governments all the time.也是被公司以及各国政府所常常使用的 .And what it involvesis placing a value,它的内涵是用一个价值usually a dollar value,to stand for utility on the costs通常是由美元,来代表不同提案的效用and the benefitsof various proposals.这效用是基于成本和效益得出的Recently, in the Czech Republic,there was a proposal最近,在捷克共和国,有一个提案to increase the excise tax on smoking.Philip Morris, the tobacco company,对吸烟增加货物税.Philip Morris烟草公司,does huge businessin the Czech Republic.该公司在捷克共和国有着大笔生意.They commissioned a study,a cost-benefit analysis他们委托了一个研究,of smoking in the Czech Republic,and what their cost-benefit关于吸烟在捷克共和国的成本效益分析.analysis found was the governmentgains by having Czech citizens smoke.他们的分析发现,捷克政府将会因公民吸烟而收益.Now, how do they gain?现在,他们如何收益?It's true that there arenegative effects to the public finance确实,捷克政府的公共财政体系of the Czech governmentbecause there are increased health care会因为吸烟人群所引发的相关疾病而增加的医疗保健开支, costs for people who developsmoking-related diseases.从而受到负面影响.On the other hand,there were positive effects另一方面,这也有积极效应and those were added upon the other side of the ledger.并且这些积极效益累加到了账簿的另一面The positive effects included,for the most part,积极效益包括,在大多数情况下,various tax revenues that thegovernment derives from the sale政府通过卷烟产品而获得的各种税收收入,of cigarette products,but it also included但也包括health care savings to thegovernment when people die early,政府因为吸烟人群过早死亡而省下的医疗储蓄,例如pension savings -- you don't have topay pensions for as long -养老金储蓄-不必支付退休金了-and also, savings inhousing costs for the elderly.还有,老年人住房费用.And when all of the costsand benefits were added up,当把所有的成本和效益都分别加起来,the Philip Morris study foundthat there is a net public finance gainPhilip Morris公司的研究发现,捷克共和国会有一个in the Czech Republicof $147,000,000,$147,000,000的公共财政净增益,and given the savings in housing,in health care, and pension costs,并鉴于节省了住房费用,医疗保健费用,养老金费用, the government enjoys savingsof over $1,200 for each personwho dies prematurely due to smoking.每个因吸烟而过早死亡的人都为政府节省了$1,200.Cost-benefit analysis.成本效益分析.Now, those among youwho are defenders of utilitarianism现在,你们中间,那些功利主义的捍卫者may think that this is an unfair test.可能认为这是一种不公平的测试.Philip Morris was pilloriedin the pressPhilip Morris公司在新闻界遭到了嘲笑and they issued an apologyfor this heartless calculation.他们也因为这个无情的计算而发表了道歉.You may say that what's missing hereis something that the utilitarian你可能会说,功利主义在这里可以轻易弥补一个疏漏can easily incorporate,namely the value to the person它没有正确评估人的价值and to the families of those who diefrom lung cancer.以及那些因为肺癌而死亡的人的家属的损失.What about the value of life?如何评估生命价值?Some cost-benefit analyses incorporatea measure for the value of life.一些成本效益分析的确纳入了对生命价值的评估. One of the most famousof these involved the Ford Pinto case.其中最有名的要数Ford Pinto案件.Did any of you read about that?你们有没有阅读过这个案件?This was back in the 1970s.那是发生在20世纪70年代.Do you rememberwhat the Ford Pinto was,你还记得Ford Pinto是,a kind of car?Anybody?什么样的车么?谁能记得?It was a small car,subcompact car, very popular,那是一种小型车,超小型车,很受欢迎, but it had one problem,which is the fuel tank但它也有问题,车后座的油箱was at the back of the carand in rear collisions,少数情况下,碰撞会导致the fuel tank explodedand some people were killed油箱爆炸并且有些人会因此死去and some severely injured.还有人因此严重受伤.Victims of these injuriestook Ford to court to sue.这些受害者将福特告到法院.And in the court case,it turned out that Ford而在诉讼案件,人们发现福特原来had long since known about thevulnerable fuel tank早已知道油箱的脆弱and had done a cost-benefit analysisto determine whether it would be并且已做了成本效益分析,以确定是否worth it to put ina special shield that would值得来放入一个特殊的盾牌protect the fuel tankand prevent it from exploding.用来保护油箱并防止它爆炸.They did a cost-benefit analysis.他们做了成本效益分析.The cost per partto increase the safety of the Pinto,增加Ford Pinto安全的每部件费用,they calculated at $11.00 per part.他们算出,要每部件$ 11.00.And here's -- this was the cost-benefitanalysis that emerged in the trial.这里-这就是当时审判中出示的成本效益分析.Eleven dollars per partat 12.5 million cars and trucks每件11美元,乘以12.5万辆轿车和卡车came to a total cost of$137 million to improve the safety.得到一个总成本,需要13700万美元来改善安全性.But then they calculated the benefitsof spending all this money不过,他们随后计算了一下花这笔钱来改善安全性的收益率on a safer carand they counted 180 deaths(如果不花这笔钱来改善安全,)假设会导致180人死亡and they assigned a dollar value,$200,000 per death,他们对此用美元价值来代替,每个死去的人赔偿$ 200,000180 injuries, $67,000,and then the costs to repair,180人受伤的赔偿为每人$67,000,然后是维修受损车的费用,the replacement costfor 2,000 vehicles,2 000辆车,it would be destroyed withoutthe safety device $700 per vehicle.由于没有安装安全设施,每辆车将会需要$700来维修.So the benefits turned out to beonly $49.5 million结论是总效益只有$49.5 million(相对于修复安全隐患总成本需要$137 million)and so they didn'tinstall the device.因此他们没有安装那个安全设备.Needless to say,when this memo of the毫无疑问,福特汽车公司的这个成本效益分析备忘录Ford Motor Company's cost-benefitanalysis came out in the trial,在审判中出现时,it appalled the jurors,who awarded a huge settlement.震惊了陪审团,也因此裁定了福特公司巨大的赔偿金额.Is this a counterexample to theutilitarian idea of calculating?这是一个功利主义计算的反例么?Because Ford included a measureof the value of life.因为福特引入了对生命价值的评估.Now, who here wants to defendcost-benefit analysis好,这里有谁想针对这一明显反例from this apparent counterexample?来捍卫成本效益分析?Who has a defense?谁来辩护?Or do you think thiscompletely destroys the whole或者你认为这一反例已经完全摧毁了utilitarian calculus?Yes?功利主义计算? 你来Well, I think that once again,they've made the same mistake嗯,我想再次指出,他们犯了同样的错误the previous case did,that they assigned a dollar value和以前的情况一样,他们对人的生命赋予to human life,and once again,一个美元为单位的价值,同样的,they failed to take accountthings like suffering他们没有考虑到家属的痛苦和损失and emotional losses by the families.诸如此类的因素.I mean, families lost earningsbut they also lost a loved one我的意思是,家庭损失了收入来源,但他们也失去了爱人and that is more valuedthan $200,000.这些的价值远远超过$200,000的.Right and -- wait, wait, wait,that's good. What's your name?好的-等等,等等,等等,很好.你叫什么名字?Julie Roteau .Julie Roteau .So if $200,000, Julie,is too low a figure因此,Julie, 如果$200,000 是个太低的金额, because it doesn't include theloss of a loved one因为它不包括失去爱人and the loss of those years of life,what would be -以及那些在没有亲人的岁月里的损失,你认为what do you thinkwould be a more accurate number?更准确的金额是多少?I don't believe I could give a number.I think that this sort of analysis我不认为, 我可以对此给出一个金额. 我认为这类分析shouldn't be applied to issuesof human life.不适用于人类生命相关的问题.I think it can't be used monetarily.我认为不能用金钱来衡量.So they didn't just puttoo low a number, Julie says.因此,Julie认为,他们不只是金额定的太低.They were wrong to tryto put any number at all.他们压根就不应该用金额来衡量.All right, let's hear someone who -You have to adjust for inflation.好吧,让我们听听还有谁-You have to adjust for inflation. (这个金额)要根据通货膨胀进行调整.All right, fair enough.好吧,很公平.So what would the number be now? 那么现在这个金额将是?This was 35 years ago.这发生在35年前.Two million dollars.两百万美元.Two million dollars?You would put two million?200万美元? 你认为是200万?And what's your name?你的名字是?VoytekVoytekVoytek says we have toallow for inflation.Voytek说,我们必须允许通货膨胀.We should be more generous.我们应该更慷慨些.Then would you be satisfiedthat this is the right way of然后,你认为这就是考虑这个问题的thinking about the question?正确的方式么?I guess, unfortunately, it is for -我想,不幸的是,现在-there needs to be a numberput somewhere, like, I'm not sure我们需要有一个金额,我不确定what that number would be,but I do agree that合适的金额是多少,但我同意there could possiblybe a number put on the human life.对人类生命定一个金额是可行的.All right, so Voytek says,and here, he disagrees with Julie.好的,Voytek说,他不同意Julie.Julie says we can't put a numberon human life朱莉认为,我们不能在成本效益分析中for the purpose of acost-benefit analysis.对人的生命定一个金额.Voytek says we have to becausewe have to make decisions somehow.Voytek认为,我们必须这样做因为我们无论如何需要作出某种决定. What do other peoplethink about this?其他人觉得呢?Is there anyone preparedto defend cost-benefit analysis这里有人打算为能足够准确的成本效益分析辩护么?here as accurate as desirable?Yes? Go ahead.好?请继续.I think that if Fordand other car companies我认为, 如果福特和其他汽车公司didn't use cost-benefit analysis,they'd eventually go out of business没有使用成本效益分析,他们会最终歇业because they wouldn't be able to beprofitable and millions of people因为他们将无法盈利,(从而导致)数百万的人wouldn't be able to use their carsto get to jobs,将无法使用这些汽车去上班,to put food on the table,to feed their children.(没钱)购买餐桌上的食物,(没钱)来喂养孩子.So I think that if cost-benefitanalysis isn't employed,因此,我认为, 如果不利用成本效益分析,the greater good is sacrificed,in this case.在这种情况下,(我们将会)牺牲更大的利益.All right, let me add.What's your name?好吧,让我来补充. 你叫什么名字?Raul.Raul.Raul, there was recently a study doneabout cell phone use by a driverRaul,最近有一项研究表明,关于开车时驾驶者使用手机when people are driving a car,and there was a debate有一场辩论, 关于这种行为whether that should be banned.是否应被禁止.Yeah.是啊。

law review规则

law review规则

Law Review是一类在美国法学院里由学生自主运行的学术期刊,按不同的法律领域,法学院里会有多个不同类型的Journal,例如在Cornell Law School,会有International Law Journal、Journal of Law and Public Policy等。

通常在Law Review发表的文章会表达某个法律领域的学者在特定法律问题上的观点,并由其提供相关法律建议。

在美国法学院里,Law Review的文章会被美国各层级法院作为Persuasive Authority 引用(没有法律效力但可为法官判案提供参考),从而对美国法律发展产生深远的影响。

正因为Law Review的文章在美国法律界具有重要的分量,法学教授Erwin N. Griswold曾在Harvard Law Review中写道:“正是因为其(Law Review)独特的优势和严格的评选标准,才得以让期刊发展壮大。

”。

Law Review的规则可能会因法学院和期刊的不同而有所差异,如果你想了解更详细的内容,可以补充相关信息后再次向我提问。

(2021年整理)英国法学家哈特法律思想研究

英国法学家哈特法律思想研究编辑整理:尊敬的读者朋友们:这里是精品文档编辑中心,本文档内容是由我和我的同事精心编辑整理后发布的,发布之前我们对文中内容进行仔细校对,但是难免会有疏漏的地方,但是任然希望(英国法学家哈特法律思想研究)的内容能够给您的工作和学习带来便利。

同时也真诚的希望收到您的建议和反馈,这将是我们进步的源泉,前进的动力。

本文可编辑可修改,如果觉得对您有帮助请收藏以便随时查阅,最后祝您生活愉快业绩进步,以下为英国法学家哈特法律思想研究的全部内容。

英国法学家哈特法律思想研究摘要:在批判奥斯丁的基础上,哈特使英美传统分析法学获得了新生。

伴随着大范围的学术争论,哈特强有力地推动了20世纪后半期英美法理学界的发展,从而被公认为是刚刚过去的20世纪西方法学理论界最有影响的几个人物之一。

本文置哈特于当代西方法学理论多元流变的背景之下,对其法律思想的核心-—法律规则理论、法律和道德关系的学说进行梳理,以期通过对哈特法律思想的解读,发掘其中有助于中国法学理论发展的因素。

关键词:哈特分析实证主义法学法律的规则理论20世纪50-60年代,西方法律理论界接续19世纪以来长期深层次的多元裂变,各种话语和叙事再次处于为新高度上的全面对垒而激烈的酝酿之中。

在哈特面前,古老的自然法学在经历萨维尼、边沁—奥斯丁等人多方夹击之下的百年消沉之后,历经半个多世纪的缓慢复苏,已然阵容齐整、有大面积反扑之势;迟来的社会法学虽不足百年光景,却是新说奇论迭出,锐气弥足;分析法学派自1861年奥斯丁出版《法理学的范围》,虽在英美正统百年,但今非昔比,亟待维新自强。

对于哈特而言,一方面,不论是自然法学对“内心道德”的追求,还是社会法学对“社会事实”的推崇,根本上都背离了法学研究真正的问题领域,最终导致对法律本身的取消;另方面,奥斯丁虽然正确指出了法学研究的基本立场,有助于对法律在当代社会统治地位的捍卫,但由于奥斯丁对于法律及其内在制度结构的认识存在重大错误,完全停留在奥斯丁的状态,根本无力完成对当下理论挑战的有力回应。

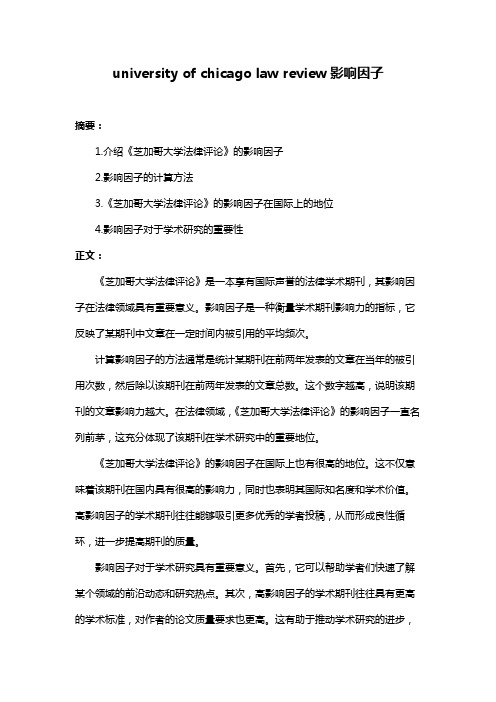

university of chicago law review影响因子

university of chicago law review影响因子

摘要:

1.介绍《芝加哥大学法律评论》的影响因子

2.影响因子的计算方法

3.《芝加哥大学法律评论》的影响因子在国际上的地位

4.影响因子对于学术研究的重要性

正文:

《芝加哥大学法律评论》是一本享有国际声誉的法律学术期刊,其影响因子在法律领域具有重要意义。

影响因子是一种衡量学术期刊影响力的指标,它反映了某期刊中文章在一定时间内被引用的平均频次。

计算影响因子的方法通常是统计某期刊在前两年发表的文章在当年的被引用次数,然后除以该期刊在前两年发表的文章总数。

这个数字越高,说明该期刊的文章影响力越大。

在法律领域,《芝加哥大学法律评论》的影响因子一直名列前茅,这充分体现了该期刊在学术研究中的重要地位。

《芝加哥大学法律评论》的影响因子在国际上也有很高的地位。

这不仅意味着该期刊在国内具有很高的影响力,同时也表明其国际知名度和学术价值。

高影响因子的学术期刊往往能够吸引更多优秀的学者投稿,从而形成良性循环,进一步提高期刊的质量。

影响因子对于学术研究具有重要意义。

首先,它可以帮助学者们快速了解某个领域的前沿动态和研究热点。

其次,高影响因子的学术期刊往往具有更高的学术标准,对作者的论文质量要求也更高。

这有助于推动学术研究的进步,

提高整体研究水平。

总之,《芝加哥大学法律评论》的影响因子在法律领域具有重要意义。

它不仅反映了该期刊在学术研究中的地位,同时也体现了学术研究的发展和趋势。

美国各大学法律评论

Alaska Law Review

杜克大学主办 全文

阿尔巴尼法律评论

Albany Law Review

阿尔巴尼大学主办

美国大学法律评论

American University Law Review

美国大学主办 全文

美国法律年鉴

Annual Survey of American Law

Syracuse Law Review

雪城大学主办

天坡法律评论

Temple Law Review

天坡大学主办

田纳西法律评论

Tennessee Law Review

田纳西大学主办

德克萨斯法律评论

Texas Law Review

德州大学主办

德州科技法律评论

霍夫斯特大学主办 全文

休斯敦法律评论

Houston Law Review

休斯敦大学主办

印地安那法律期刊

Indiana Law Journal

印地安那大学主办 全文

印地安那法律评论

Indiana Law Review

印地安那大学印地安那波利斯分校主办

爱荷华法律评论

凯斯西瑞热福大学主办

芝加哥肯特法律评论

Chicago-Kent Law Review

伊利诺斯理工学院&芝加哥肯特法学院主办 摘要

克里夫兰州法律评论

Cleveland State Law Review

克里夫兰州立大学&克里夫兰玛逊法学院主办

医学法律评论

洛约纳玛丽蒙特大学主办 全文

洛约纳法律期刊

Loyola Law Journal

斯坦福大学法律评论

斯坦福大学法律评论竞购和拍卖理论J.罗素丹顿版权所有(c)2008利兰斯坦福初级学院董事会J.罗素丹顿引言在最近的一股私人股本收购上市公司的风潮中,销售公司的董事会越来越倾向于竞购条款,该条款是露华浓公司董事局为实现股东利益最大化而采用的一种方法。

竞购条款运作起来是作为一项在与原始买家达成了协议之后与第三方征求到商业信息的时候的一项签署的市场检查。

正如同一个出版的执业律师,竞购条款没有给销售公司只留下了好处,没有给公开拍卖留下任何风险,因为他们允许销售公司锁定一个价格底线,同时保留进一步与其他买家谈判一个更高价格的行为的能力。

然而,也有人猜测竞购是“董事会为了保护他们自身绕开股东的怒气的一个虚伪的做法”。

销售董事会决定在任何情况下检测合并条款,买方如果不想得到他想要的,他们可以不签署协议条款。

这就给销售公司董事局带来压力了,董事局在这个情况下如何实现利益的最大化,这个没有单一的答案。

董事会必须要做的是尽最大可能维护他们股东的利益,而不是强硬的推动买家去签署他们不想签署的协议。

特拉华州法院已经认识到,销售公司迫切需要更好的条件和买方给的交易又毫无选择的余地,二者之间假装对话,买方放弃交易是对这个对话的真正威胁。

买家不同意签订协议,导致法院认识到了目标董事局可以对买家实行禁售规定,只要这些规定是在合理的范围之内即可。

直至2007年6月,没有任何法院在处理案子的时候可以按照竞售条款的处理方式,这条方案是为了露华浓公司员工的职责而采用的。

但是,有两个特拉华州衡平法院案件2007年6月决定驳回原告的露华浓的求偿申诉,竞购条款就没有实现股东价值的最大化。

在第一种情况下,在公司顶尖的诉讼中,原告质疑的私人对高层的股权的购买,此时管理层已经获得持续就业保证了收购公司的股权。

合并协议包含一个竞购规定,种植费用,和搭配一个有利于买方的权利。

除此之外,没有任何形式的预签市场调查。

尽管如此,副院长斯特林写到,“我不相信合并合同的实质性条款,这种合同将不合理的东西最大化了。

Harvard Law Review中英对照

Mechanisms of SecrecyHarvard Law Review, Vol. 121, April 2008, No. 6政府保密机制札记《哈佛法律评论》,第一二一卷,二00八年四月,第六号Tr. ChunfengqiushuiTo what extent should the government keep secrets from the people? Government often needs to operate in secret in order to shape and execute socially desirable policies, and excessive transparency requirements can have an ossifying effect that prevents government from responding in innovative ways to changed circumstances.[1] But transparency helps ensure that governmental actors do not misuse their power; a government that is free to operate in secret is free to do both good and bad things without fear of reproach from the voters. Secrecy is in some areas, such as national security, essential to a nation’s ongoing vitality, yet it seems to be strongly in tension with accountability[2]— a necessary element of democracy. There is no easy resolution to this conflict. On one hand are claims such as Cardinal Richelieu’s that “[s]ecrecy is the first essential in affairs of state”;[3] on the other are those like Jeremy Bentham’s assertion that secrecy, being “an instrument of conspiracy[,] . . . ought not, therefore, be the system of a regular government,”[4] or, more recently, the Sixth Circuit’s declaration that “[d]emocracies die behind closed doors.”[5]政府应对人民保密到什么程度?政府经常需要秘密操作以形成社会上期盼的政策并实施这些政策,过分的透明需求将产生僵化效应,使得政府无法以创新的方式应对变化了的环境。

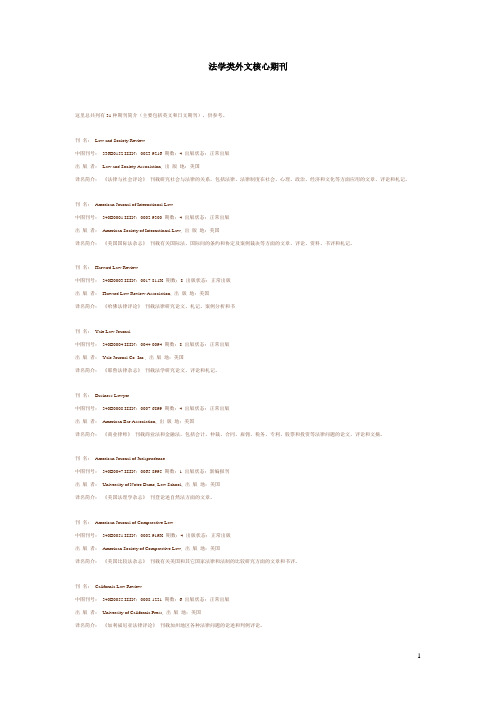

法学类外文核心期刊(中英文)

法学类外文核心期刊这里总共列有31种期刊简介(主要包括英文和日文期刊),供参考。

刊名:Law and Society Review中图刊号:336B0152 ISSN:0023-9216 期数:4 出版状态:正常出版出版者:Law and Society Association, 出版地:美国译名简介:《法律与社会评论》刊载研究社会与法律的关系,包括法律、法律制度在社会、心理、政治、经济和文化等方面应用的文章、评论和札记。

刊名:American Journal of International Law.中图刊号:340B0001 ISSN:0002-9300 期数:4 出版状态:正常出版出版者:American Society of International Law, 出版地:美国译名简介:《美国国际法杂志》刊载有关国际法、国际间的条约和协定及案例裁决等方面的文章、评论、资料、书评和札记。

刊名:Harvard Law Review.中图刊号:340B0003 ISSN:0017-811X 期数:8 出版状态:正常出版出版者:Harvard Law Review Association, 出版地:美国译名简介:《哈佛法律评论》刊载法律研究论文、札记、案例分析和书刊名:Yale Law Journal.中图刊号:340B0004 ISSN:0044-0094 期数:8 出版状态:正常出版出版者:Yale Journal Co. Inc., 出版地:美国译名简介:《耶鲁法律杂志》刊载法学研究论文、评论和札记。

刊名:Business Lawyer.中图刊号:340B0008 ISSN:0007-6899 期数:4 出版状态:正常出版出版者:American Bar Association, 出版地:美国译名简介:《商业律师》刊载商业法和金融法,包括会计、仲裁、合同、雇佣、税务、专利、股票和投资等法律问题的论文、评论和文摘。

美国各大学法律评论

奥克隆法律评论

Akron Law Review

奥克隆大学主办 全文

阿拉巴马法律评论

Alabama Law Review

阿拉巴马大学主办 全文

阿拉斯加法律评论

Alaska Law Review

杜克大学主办 全文

阿尔巴尼法律评论

Albany Law Review

佐治亚大学主办 全文

佐治亚州立大学法律评论

Georgia State University Law Review

佐治亚州立大学主办

贡扎加法律评论

Gonzaga Law Review

贡扎加学院主办

哈姆莱因法律评论

Hamline Law Review

哈姆莱因大学法学院主办 摘要

Capital University Law Review

首都大学主办

卡多佐法律评论

Cardozo Law Review

卡多佐法学院主办 摘要

凯斯西瑞热福法律评论

Case Western Reserve Law Review

凯斯西瑞热福大学主办

芝加哥肯特法律评论

东北大学主办

北伊利诺斯大学法律评论

Northern Illinois University Law Review

北伊利诺斯大学主办

北肯德基法律评论

Northern Kentucky Law Review

北肯德基大学西蒙P切斯法学院主办

Occasional Papers

佩斯法律评论

Pace Law Review

佩斯大学主办

帕伯丁法律评论

霍姆斯法律的道路

霍姆斯: 法律的道路霍姆斯(O.W. Holmes, 1841~1933。

美国现代实用主义法学的创始人。

1866 年毕业于哈佛大学法学院,在波斯顿从事一段时间的律师工作之后,于1 870年入哈佛大学法院担任讲师、教授,1882年1 2月担任马萨诸塞州最高法官,1899年起任院长。

1902年~1932年,担任美国联邦最高法院法官。

霍姆斯的学说,主要体现在他于1881年出版的著作《普通法》(The Common Law, 已有中文版)、《法律之路》(The Path of the Law )、他逝世后出版的判决意见集《霍姆斯法官的司法见解》(The Judicial Opinions of Mr. Justice Holme Shriver ed 1940)以及生前发表的一系列论文之中.我们研究法律,研究的不是什么秘密,而是一项众所周知的职业。

我们研究的是,为了和法官打交道,或者,为了告诉人们怎样免于诉讼,我们要做哪些准备。

为什么它是一项职业?为什么律师辩护和咨询要收取报酬?原因在于在我们这样的社会中,公共力量掌握在特定案件的法官手里,在必要时还可以调动整个国家的力量来保证他们的判决和裁定得到执行。

人们需要知道,在哪种场合,在多大程度上,他们会与这种比他们自身强大得多的力量发生冲突。

于是,辨别何时危险会真正降临就成为一桩买卖。

所以,我们研究的目的就是为了预测,预测公共力量何时假手于法院。

我们研究的材料是我国和英国的大量的报告、专著和制定法,它们可以回溯到六百年前,现在仍以每年数以百计的速度递增。

过去案件中各种零乱的预言被收罗在这些文献里,而未来的判决将会依据它们做出。

它们就是法律的宣示,这一称谓是恰当的。

至关重要的是,法律思考新探索的全部意义基本就在于使这些预言更简洁明了,并把它们概括成一个自洽的体系。

以律师对某一案件的描述为例,这个过程是这样的:抽象规律具有法律意义的事实。

律师不提他的委托人在签订合同时头戴白帽,而多嘴小姐却可能罗里罗嗦地谈她的镀金酒杯、海煤火和行李,其原因在于律师知道不管他的委托人头戴什么,公共力量的行使都是一样的。

探秘美国福特汉姆大学金融硕士

探秘美国福特汉姆大学金融硕士美国Fordham University(福特汉姆大学)是一所中等规模的私立大学,知名度在纽约仅次于哥伦比亚大学和纽约大学。

2014年USNews美国大学金融专业排名该校排名第15名,Fordham是爱国者联盟盟校之一。

除福特汉姆之外,该联盟由包括麻省理工学院(MIT)、理海大学(Lehigh University)、乔治敦大学(Georgetown University)、美国西点军校(West Point)、和美国海军学院(USNA)在内的其他12个精英学府组成。

Fordham金融专业旨在培养和锻造既有金融经济理论知识和能力,又精通外语的国际型、复合型人才,以实施金融专业与外语专业“合二为一”的教学模式,走开放式发展的办学道路,为各类金融和非金融机构培养出实用型、复合型的金融专门人才。

下面申友教育就这个学校的数量金融专业详细的为大家做一下介绍。

美国Fordham数量金融学硕士专业描述:所在院校:美国Fordham;学制:1学年专业领域:商科与管理学;学费:36900美元/学年课程层次:硕士学位课程(授课类);申请费:70美元入学日期:每年1,8月该课程的学生可以是投资银行、商业银行的雇员,也可以是资金管理员、基金和其它公司的员工。

该课程为学生提供扎实的数量分析技术并开发金融知识。

美国Fordham数量金融学硕士就业方向:通过本专业的学习,凭借其专业知识可以在投资银行与证券交易公司,商业银行、国际金融市场或政府中央银行等金融部门工作,也可以继续自己的博士学位。

美国Fordham数量金融学硕士入学要求:学术要求:1.相关专业本科毕业,GPA3.0以上;2.GRE成绩。

语言要求:1.托福网考90分,机考230分,笔试575分以上;2.或雅思7.0分以上。

3.学校提供双录取。

美国Fordham数量金融学硕士申请材料:1.3封推荐信;2.个人简历;3.个人陈述;4.作文;5.官方成绩单(英文版)。

美国谢尔曼反托拉斯法(中英文)

美国谢尔曼反托拉斯法(中英⽂)Section 1. Trusts, etc., in restraint of trade illegal; penalty第⼀条现在贸易的托拉斯⾏为违法,将予以处罚。

Every contract, combination in the form of trust or otherwise, or conspiracy, in restraint of trade or commerce among the several States, or with foreign nations, is declared to be illegal. Every person who shall make any contract or engage in any combination or conspiracy hereby declared to be illegal shall be deemed guilty of a felony, and, on conviction thereof, shall be punished by fine not exceeding $10,000,000 if a corporation, or, if any other person, $350,000, or by imprisonment not exceeding three years, or by both said punishments, in the discretion of the court.任何限制州际间或与外国之间的贸易或商业的契约,以托拉斯形式或其它形式的联合,或共谋,都是⾮法的。

任何⼈签订上述契约或从事上述联合或共谋,将构成重罪。

如果参与⼈是公司,将处以不超过1000万美元的罚款。

如果参与⼈是个⼈,将处以不超过35万美元的罚款,或三年以下监禁。

Harvard Law Review

C ONSTITUTIONAL L AW—L EGISLATIVE P RIVILEGE— D.C.C IRCUIT H OLDS THAT FBI S EARCH OF C ONGRESSIONAL O FFICE V IOLATED S PEECH OR D EBATE C LAUSE. — United States v. Rayburn House Office Building, 497F.3d 654 (D.C. Cir. 2007), reh’g en banc denied, No. 06-3015, 2007 U.S. App. LEXIS 26295 (D.C. Cir. Nov. 9, 2007).The exact contours of legislative privilege have never been clear in American constitutional law. The privilege’s textual root, the Speech or Debate Clause,1 follows the language of the English Bill of Rights,2 which sought both to protect legislative independence and to ensure parliamentary supremacy.3 Yet, in the United States, the Speech or Debate Clause — and with it legislative privilege — must be inter-preted in light of the separation of powers structure of our Constitu-tion.4 Recently, in United States v. Rayburn House Of f ice Building,5 the D.C. Circuit considered the scope of legislative privilege and its ef-fect on an FBI search of a congressional office.6 In affirming the dis-trict court’s denial of Representative William Jefferson’s motion for the return of all documents obtained in the search of his office,7 the –––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––1U.S. C ONST. art. I, § 6, cl. 1.2Compare id. (“[F]or any Speech or Debate in either House, [Members of Congress] shall not be questioned in any other Place.”), with An Act Declaring the Rights and Liberties of the Sub-ject, and Settling the Succession of the Crown (Bill of Rights),1689,1 W. & M., c. 2, § 97(Eng.) (“That the Freedom of Speech, and Debates or Proceedings in Parliament ought not to be im-peached or questioned in any Court or Place out of Parliament.”).3See Alexander J. Cella, The Doctrine of Legislative Privilege of Freedom of Speech and De-bate: Its Past, Present, and Future as a Bar to Criminal Prosecutions in the Courts, 2 S UFFOLK U.L.R EV. 1, 3–13 (1968); see also United States v. Brewster, 408 U.S. 501, 508 (1972) (“We should bear in mind that the English system differs from ours in that their Parliament is the supreme authority, not a coordinate branch. Our speech or debate privilege was designed to preserve legis-lative independence, not supremacy.”).4See Brewster, 408 U.S. at 508 (“Although the Speech or Debate Clause’s historic roots are in English history, it must be interpreted in light of the American experience, and in the context of the American constitutional scheme of government rather than the English parliamentary sys-tem.”); Cella, supra note 3, at 15 (explaining how England and America’s differences led to changes in the concept of legislative privilege in early America); Note, Evidentiary Implications of the Speech or Debate Clause, 88 Y ALE L.J. 1280, 1284–88 (1979) (discussing the background of the Speech or Debate Clause in America).5 497F.3d 654 (D.C. Cir. 2007), reh’g en banc denied, No. 06-3015, 2007 U.S. App. LEXIS 26295 (D.C. Cir. Nov. 9, 2007).6See id. at 655.7The court affirmed the denial of Representative Jefferson’s motion for the return of all documents, but ordered the return of all privileged documents — as to be determined by the dis-trict court. See id. at 665; see also id. at 667 (Henderson, J., concurring in the judgment). There-fore, the court’s decision had the practical effect of reversing the district court’s holding that the search did not violate the Speech or Debate Clause. Compare In re Search of the Rayburn House Office Bldg., 432 F. Supp. 2d 100, 116 (D.D.C. 2006) (“[T]he search did not violate the Speech or Debate Clause.”), with Rayburn, 497F.3d at 663 (“[W]e hold that a search that allows agents of the Executive to review privileged materials without the Member’s consent violates the Clause.”). 9142008]RECENT CASES915 court held that the search violated the Speech or Debate Clause.8 Al-though the court correctly held that compelled disclosure of legislative material within the sphere of “legitimate legislative activity”9 violated the Congressman’s legislative privilege, it went too far in holding that the nondisclosure privilege is absolute in the criminal context. Just as the Supreme Court has qualified the executive privilege in order to preserve separation of powers values, the D.C. Circuit would have bet-ter protected those values by similarly limiting the legislative nondis-closure privilege.During its investigation into allegations that Congressman William Jefferson was involved in a fraud and bribery scheme, the Department of Justice (DOJ) applied for a warrant to search Congressman Jeffer-son’s office.10 In its warrant request, the DOJ sought nonlegislative evidence and asserted that it “had exhausted all other reasonable methods to obtain these records in a timely fashion.”11 In addition, the DOJ described “special procedures” through which it would screen seized documents to avoid disclosing privileged documents to prosecu-tors or members of the executive branch other than the three members of the screening team.12 After finding probable cause for the search, the district court issued the warrant.13 T wo days later, FBI agents en-tered Congressman Jefferson’s office and spent approximately eighteen hours reviewing and seizing paper and electronic documents, some of which were legislative materials.14 Following the search, the Office of the Deputy Attorney General froze review of the seized documents.15 Congressman Jefferson then filed a motion under Federal Rule of Criminal Procedure 41, requesting the return of all seized materials.16 His motion alleged that the search violated the Speech or Debate Clause and sought to have the FBI and DOJ enjoined from reviewing the materials.17 The district court denied the motion, holding that “execution of the warrant ‘did not impermissibly interfere with Con-–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––8See Rayburn, 497F.3d at 656.9Id. at 667 (quoting Tenney v. Brandhove, 341 U.S. 367, 376(1951)) (internal quotation marks omitted).10Id. at 656 (describing the origins of the DOJ’s investigation of the Congressman and its sus-picion that he had “accepted financial backing and or concealed payments of cash or equity inter-ests in business ventures located in the United States, Nigeria, and Ghana in exchange for his un-dertaking official acts as a Congressman while promoting the business interests of himself and [those providing the backing and payments]”).11Id.12Id. at 656–57.13Id. at 657.14See id.15Id. (citing Brief of Appellee at 10, Rayburn, 497F.3d 654 (No. 06-3105)).16Id.17Id.916HARVARD LAW REVIEW [V ol. 121:914 gressman Jefferson’s legislative activities’”18 because the warrant’s limited scope prevented “undue Executive intrusion.”19The D.C. Circuit affirmed the district court’s denial of the motion but held that the search violated the Speech or Debate Clause.20 Writ-ing for the majority, Judge Rogers21 rested her decision on an extension of the D.C. Circuit’s legislative privilege doctrine as most recently ar-ticulated in Brown & Williamson Tobacco Corp. v. Williams,22 which addressed nondisclosure of legislative materials in the context of a civil subpoena.23 The court first explained the historical roots of legislative privilege.24 It then recounted Supreme Court precedent on the clause, which “has made clear . . . that ‘[t]he Speech or Debate Clause was de-signed to assure a co-equal branch of the government wide freedom of speech, debate, and deliberation without intimidation or threats from the Executive Branch.’”25 Accordingly, the Supreme Court has limited the clause’s protection to “conduct that is an integral part of ‘the due functioning of the legislative process,’” but has not addressed whether the clause provides a nondisclosure privilege.26 However, the court noted that its own precedent, established in Brown & Williamson, has interpreted the clause as providing a nondisclosure privilege in civil cases.27Judge Rogers concluded that Brown & Williamson’s holding con-trolled the case. She construed that case as “mak[ing] clear that a key purpose of the privilege is to prevent intrusions in the legislative proc-ess and that the legislative process is disrupted by the disclosure of leg-islative material.”28 Next, she stated that Brown & Williamson’s “bar on compelled disclosure is absolute.”29 Thus, because Congressman Jefferson was not given a chance to assert his privilege over docu-ments before the FBI reviewed and seized them, the court held that the search violated the Speech or Debate Clause.30–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––18Id. (quoting In re Search of the Rayburn House Office Bldg., 432 F. Supp. 2d 100, 113 (D.D.C. 2006)).19Id.20See id. at 663, 665.21Judge Rogers was joined by Chief Judge Ginsburg.2262F.3d 408 (D.C. Cir. 1995).23See Rayburn, 497F.3d at 660.24Id. at 659.25Id. (alteration in original) (quoting Gravel v. United States, 408 U.S. 606, 616 (1972)).26Id. (quoting United States v. Brewster, 408 U.S. 501, 513 (1972)).27Id. at 660.28Id.29Id. (citation omitted) (arguing that “[a]lthough Brown & Williamson involved civil litigation and the documents being sought were legislative in nature, the court’s discussion of the Speech or Debate Clause was more profound and repeatedly referred to the functioning of the Clause in criminal proceedings”).30Id. at 662–63.2008]RECENT CASES917 Turning to the question of the proper remedy for the constitutional violation, the court set forth the following principle: “The Speech or Debate Clause protects against the compelled disclosure of privileged documents to agents of the Executive, but not the disclosure of non-privileged materials.”31 In accord with this principle, the court re-jected the Congressman’s request for the return of all seized docu-ments and ordered the return of only the privileged documents.32 Judge Henderson concurred in the judgment. She accused the ma-jority of over-reading Brown & Williamson, which she would have limited to situations involving civil subpoena requests for legislative documents.33 Unlike subpoenas, she argued, search warrants do not require an affirmative act by the targeted party and therefore do not amount to “question[ing]” under the Speech or Debate Clause.34 Judge Henderson thus argued that Brown & Williamson’s nondisclosure rule did not extend to criminal investigations because “it is well settled that a Member is subject to criminal prosecution and process”35 and be-cause a shield against all disclosure of materials to the executive branch would “jeopardize law enforcement tools ‘that have never been considered problematic.’”36 In short, Judge Henderson agreed with the majority’s denial of Congressman Jefferson’s motion for the return of all documents, but disagreed with the majority’s more doctrinally significant holding37 that the FBI’s review and seizure of legislative documents violated the Speech or Debate Clause.Over two hundred years after James Madison presciently called for a clearer articulation of the Speech or Debate Clause’s scope,38 courts –––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––31Id. at 664.32Id. at 666. The court seemed to suggest, however, that the return of all seized documents might be an appropriate remedy when the lack of original documents poses a disruption to the legislative function of a Congressman’s office. See id. at 665.33See id. at 669 (Henderson, J., concurring in the judgment).34Id. (quoting id. at 660 (majority opinion)).35Id. at 670.36Id. at 671 (quoting Brief of Appellee at 10, Rayburn, 497 F.3d 654 (No. 06-3105)).37Judge Henderson characterized the majority’s holdings beyond denial of the motion as dicta. See id. at 667. But it is unlikely that future courts will treat the majority’s Speech or De-bate Clause reasoning as dicta since that reasoning forms the basis for the majority’s ultimate holding affirming the district court’s denial of the motion.38See Cella, supra note 3, at 15 (citing J ANE B UTZNER,C ONSTITUTIONAL C HAFF47 (1941)). This desire to define clearly the scope of the privilege stands somewhat in contrast to Blackstone’s description of the breadth of English parliamentary privileges: “The dignity and in-dependence of the two houses are therefore in great measure preserved by keeping their privileges indefinite.” 1W ILLIAM B LACKSTONE,C OMMENTARIES *159. In fact, during a speech on the floor of the Sixth U.S. Senate, Charles Pinckney explained the Founders’ intentional break from the undefined English privilege as follows:[The Founders] well knew how oppressively the power of undefined privileges had beenexercised in Great Britain, and were determined no such authority should ever be exer-cised here. They knew that in free countries very few privileges were necessary to theundisturbed exercise of legislative duties . . . ; they never meant that the body who ought918HARVARD LAW REVIEW [V ol. 121:914 still struggle to determine the exact contours of its protections.39 In Rayburn, the D.C. Circuit engaged this struggle as it addressed the question of whether the Speech or Debate Clause prohibits compelled disclosure of legislative materials. The court correctly concluded that the clause confers a legislative privilege against the compelled disclo-sure of legislative materials to executive branch officials, but it incor-rectly enshrined this privilege as absolute. Instead, the court should have better respected the separation of powers rationale underlying the Speech or Debate Clause by qualifying the nondisclosure privilege as the Supreme Court qualified the executive privilege in United States v. Nixon.40Although the D.C. Circuit claimed to be following precedent and adhering to the separation of powers rationale undergirding the Speech or Debate Clause,41 neither precedent nor the separation of powers calls for an absolute nondisclosure privilege. First, relevant precedent does not require the court’s absolute privilege. In Brown & William-son, the chief case on which the Rayburn court relied, the D.C. Circuit suggested that the absolute nondisclosure privilege it recognized in the civil context should yield to sovereign interests in some situations.42 The Rayburn court acknowledged this suggestion43 but summarily dis-missed the possibility that legislative privilege should yield to sover-eign interests in this case.44 In bypassing this internal limitation on Brown & Williamson’s holding, the court expanded the scope of the legislative privilege beyond the dictates of precedent, and it did so without explicit reasoning.Second, separation of powers principles do not demand the abso-lute privilege the court conferred. Those principles function to protect each branch from undue intrusions by the other branches, but do not preclude all intrusions.45 In fact, some separation of powers balancing –––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––to be the purest, and the least in want of shelter from the operation of laws equally af-fecting all their fellow citizens, should be able to avoid them . . . .10 A NNALS OF C ONG. 72 (1851).39See Laura Krugman Ray, Discipline Through Delegation: Solving the Problem of Congres-sional Housecleaning, 55 U.P ITT.L.R EV. 389, 404 (1994) (“The problem that the Supreme Court has repeatedly failed to solve is the definition of those [Speech or Debate Clause] boundaries with precision and consistency.”).40418 U.S. 683 (1974).41See Rayburn, 497F.3d at 660–61.42Brown & Williamson Tobacco Corp. v. Williams, 62F.3d 408, 419–20 (D.C. Cir. 1995) (“Gravel’s sensitivities to the existence of criminal proceedings against persons other than Mem-bers of Congress at least suggest that the testimonial privilege might be less stringently applied when inconsistent with a sovereign interest . . . .”).43See Rayburn, 497F.3d at 660 n.4.44See id. at 660, 663.45See Mistretta v. United States, 488 U.S. 361, 380 (1989) (“[W]hile our Constitution mandates that ‘each of the three general departments of government [must remain] entirely free from the control or coercive influence, direct or indirect, of either of the others,’ the Framers did not re-2008]RECENT CASES919 is always required in conflicts involving two branches of the federal government.46 Importantly, the Supreme Court — and ironically the Rayburn court itself — has acknowledged that such balancing con-cerns should not be ignored when applying the Speech or Debate Clause, especially in criminal cases.47The Rayburn court, however, ignored those very balancing con-cerns in narrowly focusing on legislative independence as an end in it-self,48 rather than as a means toward the end of preserving the separa-tion of powers structure established in the Constitution. Although the court eventually considered separation of powers concerns when ad-dressing remedies,49 it had already disrupted the balance of power be-tween the branches by ignoring those concerns when delineating the nondisclosure privilege.50 By failing to balance each branch’s respec-tive constitutional interests, the Rayburn court effectively ignored the difference between the American and English legislative privileges.51 In fact, in its attempt to preserve legislative independence, the court inadvertently damaged legislative integrity and the separation of pow-ers — the only legitimate reasons for preserving that independence. As the Supreme Court recognized in United States v. Brewster, inde-pendence and integrity are inharmonious with corruption and immu-nity: “[B]ribes . . . gravely undermine legislative integrity and defeat –––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––quire — and indeed rejected — the notion that the three Branches must be entirely separate and distinct.” (quoting Humphrey’s Executor v. United States, 295 U.S. 602, 629(1935))); T HE F EDERALIST N O. 47, at 297–300 (James Madison) (Clinton Rossiter ed., 1961).46See, e.g., Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer, 343 U.S. 579, 634–55 (1952) (Jackson, J., concurring). For this reason, courts should avoid overemphasizing one separation of powers pro-tection while ignoring other protections provided to preserve the constitutional structure. By fo-cusing solely on the independence rationale underlying the Speech or Debate privilege and ignor-ing the other branches’ interests, the Rayburn majority strengthened legislative privilege beyond its structurally legitimate bounds. On the other hand, the concurrence’s overly narrow conception of the Speech or Debate Clause and heavy emphasis on the Executive’s law enforcement power similarly disrupted the inter-branch balance sought through the separation of powers.47See United States v. Brewster, 408 U.S. 501, 508 (1972) (“Our task, therefore, is to apply the Clause in such a way as to insure the independence of the legislature without altering the historic balance of the three co-equal branches of Government.”); Rayburn, 497F.3d at 664–65 (quoting Brewster for this proposition, but doing so only after determining the scope and strength of the nondisclosure privilege).48See Rayburn, 497F.3d at 660–61.49See id. at 664–65.50See In re Search of the Rayburn House Office Bldg., 432 F. Supp. 2d 100, 117 (D.D.C. 2006) (“[T]he principle of the separation of powers is threatened by the position that the legislative branch enjoys the unilateral and unreviewable power to invoke an absolute privilege, thus mak-ing it immune from the ordinary criminal process of a validly issued search warrant.”).51In recognition of the functional difference between the English and American legislative privileges, the Founders affirmatively limited the English concept by providing only for legislative privilege from arrest and the Speech or Debate privilege, while eighteenth-century Parliament enjoyed a wider range of privileges, including protection from service of process, entrance upon members’ lands, arrest of members’ menial servants, and seizure of members’ property. Compare U.S.C ONST. art. I, § 6, cl. 1, with 1 B LACKSTONE, supra note 38, at *159–60.920HARVARD LAW REVIEW [V ol. 121:914 the right of the public to honest representation. Depriving the Execu-tive of the power to investigate and prosecute and the Judiciary of the power to punish bribery of Members of Congress is unlikely to en-hance legislative independence.”52To better respect the Speech or Debate Clause’s underlying separa-tion of powers rationale, the Rayburn court should have considered the interbranch conflict at play when delineating the legislative nondisclo-sure privilege, and accordingly should have set forth a nondisclosure privilege similar to the one established in United States v. Nixon. Nixon is an appropriate parallel to Rayburn because both involved an official’s assertion of privilege over confidential materials in response to a criminal prosecution.53 In Nixon, the Supreme Court addressed a conflict between the need for effective law enforcement and the need to preserve the President’s ability to receive candid, confidential ad-vice.54 Similarly, the Rayburn court addressed a conflict between the executive branch’s law enforcement duties and Representatives’ need for advice.55 Yet, the two courts addressed the conflict at different stages of their respective analyses: the Nixon Court addressed the con-flict when crafting the executive privilege,56 while the Rayburn court addressed the conflict when considering possible remedies after craft-ing the legislative privilege.57Initially, the qualified executive privilege in Nixon might seem in-apposite because executive privilege is inferred from structural and functional understandings of the Constitution while legislative privi-lege derives from an explicit constitutional provision. However, as the Rayburn court’s analysis makes clear, a legislative nondisclosure privi-lege is based more on the clause’s underlying rationale of protecting the separation of powers by protecting legislative independence, and less on the specific language of the Speech or Debate Clause.58 There-fore, because the nondisclosure privilege essentially derives from in-ferred rationales underlying constitutional text, the Nixon privilege, which also derives from underlying constitutional rationales, is differ-ent only in that it lacks a discrete constitutional origin.–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––52Brewster, 408 U.S. at 524–25.53Although the issue in Nixon derived from a conflict between two executive branch officials, a Special Prosecutor and the President, the Court characterized the conflict as an inter-branch conflict between the judicial branch, which issued the subpoena for President Nixon’s tapes, and the President, who sought to prevent their release. See United States v. Nixon, 418 U.S. 683, 707 (1974).54Id. at 705–09.55See Rayburn, 497F.3d at 664–65.56See Nixon, 418 U.S. at 707.57See Rayburn, 497F.3d at 663–65.58See id. at 659–60.2008]RECENT CASES921 In Nixon, the Supreme Court carefully balanced the President’s in-terest in confidentiality and independence with the courts’ interest in the administration of justice. The Court achieved this balance by re-quiring there to be a “demonstrated, specific need for evidence”59 to overcome the executive privilege. This formulation effectively re-spected each branch’s interest by recognizing a presumption of privi-lege60 but ensuring that the privilege could not insulate political actors from criminal law enforcement.The conflict in Rayburn presented many of the same structural in-terests at stake in Nixon. Like President Nixon, Representative Jeffer-son had interests in preserving his confidential deliberations and in be-ing free from undue harassment by the other branches. Moreover, in both cases the executive branch had an interest in enforcing the na-tion’s bribery laws and the judicial branch had an interest in ensuring the administration of criminal justice. Just as in Nixon — and just as the D.C. Circuit recognized in Brown & Williamson — these interests all deserved respect when the Rayburn court crafted the nondisclosure privilege within the criminal context. A properly qualified nondisclo-sure privilege would appropriately balance these interests: Congress would have a presumption of privilege, as required by the Speech or Debate Clause; the Executive would not be stifled in its criminal in-vestigations, as required by the Take Care Clause; and the courts would be able to issue effective search warrants and to administer jus-tice effectively, as required by Article III.In Rayburn, the D.C. Circuit addressed an important question im-plicating the entire constitutional structure. The court failed to recog-nize, however, that its conception of the legislative nondisclosure privi-lege should value not only the legislature’s interest in independence, but also the executive’s interest in law enforcement and the judiciary’s interest in the administration of justice. In other words, the court failed to recognize that constitutional privileges do not exist in a vac-uum. By focusing narrowly on legislative independence, the Rayburn court not only ignored the other two branches of government, but it also ignored the Supreme Court’s guidance in Nixon and consequently crafted a nondisclosure privilege more fit for a supreme rather than coequal legislature.–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––59Nixon, 418 U.S. at 713. D.C. Circuit precedent recognizes a nearly identical standard for Congress to overcome an assertion of executive privilege: the privileged material must be “demon-strably critical to the responsible fulfillment of the Committee’s functions.” See Senate Select Comm. on Presidential Campaign Activities v. Nixon, 498F.2d 725, 731 (D.C. Cir. 1974) (en banc). Thus, the qualified privilege standard has proven apt within the contexts of both criminal prosecutions and conflicts between the two political branches.60Nixon, 418 U.S. at 713 (“Upon receiving a claim of privilege from the Chief Executive, it became the further duty of the District Court to treat the subpoenaed material as presumptively privileged . . . .”).。

对平权法案这篇外语论文的解读

H.进入壁垒扩张对 进入壁垒扩张对DBE目标的影响 进入壁垒扩张对 目标的影响 • 市场进入壁垒限制了承包商在在 一些市场的竞争力量, 一些市场的竞争力量,这可能导 致向上倾斜的DBE供给曲线。 供给曲线。 致向上倾斜的 供给曲线 • DBE出价与即将到来的中标机会 出价与即将到来的中标机会 互相影响

加州的承包和扶持行动 • 公路工程项目的联邦援助 • 联邦援助在2000年之前与之后 规模不同 • 在联邦基金分配时最先完成项 目的企业更容易获得

招标合同

• 价格最低的投标合同更易中标 • 由于投标优惠的存在使得合格小企 业可赢得一些州政府基金

扶持行动与209提案 提案 扶持行动与

• 1982年,美国联邦公路局要求实 施扶持少数民族行动方案 • 符合成为DBE公司满足的条件:

低投标价格

D.DBE参与目标和竞争环境 参与目标和竞争环境

• 相对于联邦资助合同而言,209议案对州资 助合同的项目投标人数没有影响。(209议 案只用在联邦资助合同上) • 209议案的实施会提高投标者的平均质量 • 投标人数量与参与目标关系不大。

E.参与目标和做 买决策 参与目标和做VS买决策 参与目标和做

• 结论 结论:

• 这个模型表明扶持行动可能影响合同中标的 几种方式: 几种方式: • 1、pd > pm则C1 > C0,所有的竞标者会看 、 则 , 到他们自身的成本增加了, 到他们自身的成本增加了,不管他们会外包 出去的范围; 出去的范围; • 2、生产和购买决策的失真,δ >K − κ, C2 、生产和购买决策的失真, 将严格大于C1和 , 将严格大于 和C0,即pm = pd.

结论: 结论:

• 取消平权法案后,州政府DBE合同中标概率下降了 3.1% • 加上政府影响因素Gi估计结果表明DBE目标需求每 上升10%,就会增加3.1%的中标概率。 • 考虑公司内部影响后,Post-209*state-funded的系 数变为-0.041,比不加公司影响的结果稍大。这个 结果表明偏好影响中标这种机制很可能来自于DBE 和非DBE公司平均生产率、固定成本以及做还是买 等因素的不同。 • 不见得平权法案会导致低生产率的公司中标。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

投资条约仲裁的合法性危机——通过不一致决定使国际公法私有化引言1995年以前,只有少量的仲裁涉及投资条约下的权利,然而在过去的5年时间里,案件的数量急剧上升。

目前,超过60起有名仲裁涉及投资条约,并且这些索赔主要涉及的金额从1亿2千万美元到成千上万亿美元。

这一增长在不同组的个人做出关于法律相同点上相互冲突的决定之前,使得有经济和政治后果的公共问题的决定被私下解决,并且没有任何一个机构有能力去解决这些相互冲突的决定。

在过去的12年里,国家之间已经签订了大约1500个新的双边投资条约,并且约有5个多边投资条约为了吸引外资而授予外国投资者广泛的投资权利,并创造了投资纠纷解决途径的灵活性。

这一广泛的相互关联的权利关系网的存在意味着当困难不可避免的出现时,已经有了一个解决投资纠纷机制的拼凑物。

一些国际公法权利已经第一次在投资条约中清楚地被表达出来了,例如“公平平等”待遇的权利以及主权国家遵守承诺的义务。

法庭运用了这些标准不一致,并且做出了有分歧的责任判决。

通过仲裁解决投资纠纷的程序正创造着关于那些权利以及国际公法的意义的不稳定性,而不是为外国投资者和国家创造可靠性。

当投资仲裁仍然在它的起始阶段而不是它第一次成长痛苦的中期时,帮助法学发展、认识到目前体制的困难,并且找出办法使令人担忧的合法性危机降到最低,这些都是合适的。

通过这种方式,投资仲裁就不会像臭名昭著的洗澡水一样被人们抛弃,并且国际仲裁将确定会沿着促进国际公平的道路发展。

这篇文章的第一部分描述了投资条约的历史性和合法性框架,与这一背景相对,这篇文章的第二部分考察了投资条约仲裁的产生。

第三部分中,这篇文章讨论了目前可能提出的不一致的决定的补救方法。

第四部分描述了主要的三组不一致的决定,这三组决定已经引起了关于投资条约权利含义的不确定性。

这篇文章的第五部分回顾了文献作品、考虑了合法性的指标并且提供了一项新的分析先前改良建议的框架。

第六部分列举理由证明目前促进投资条约仲裁合法化的努力还是不够的,并且建议预防与改正措施的实现。

这篇文章建议增加关于投资条约权利的学术评论与分析,并加强仲裁过程的透明度,以此来避免产生中的不一致性的产生。

这篇文章也提出了弥补不一致决定的正确性改革,并提出建立一个独立的、永久的上诉机构,这一上诉机构拥有重新审查各种不同的投资条约下做出的裁决的权力。

而不是条约对条约的办法,这种办法在可能在不同情况下由文献和美国政府的义务作出说明。

通过这种方式,合法性、透明度、决定性以及一致性都能够在整个投资条约纠纷关系网中被重新引进,并且关于市民、投资者以及国家之类的也能被提出。

一、投资条约的演进与影响外国投资是经济发展与全球繁荣的重要工具。

它允许发展中国家发展当地工业,并获得外国投资者的资金来提高国家基础设施的建设。

同时,投资者也能获得资金回报以及在未来市场上的立足点。

随着骚乱的经济环境下全球经济的持续膨胀,投资者在如何计划他们的投资与解决与那些投资有关的纠纷方面变得更加老练。

投资条约在很多方面都扮演着越来越显著的角色,如最初决定在发展中国家投资的决定、投资的结构以及投资遇到困难时如何扩大商业利益的方法。

这一部分描述了投资条约的历史性演进,并讨论了为什么投资条约的发展成功了。

(一)投资条约的演进为了避免与炮舰政策有关的历史性难题,国家已经颁布了条约来促进外国投资,并在投资环境的稳定性方面注入了信心。

这一运动开始于友好通商航海条约,但由于这些条约的承诺受到限制,他们没有解决纠纷的会议场所,所以这一运动很快就超越了这一条约。

通过多边投资条约的努力很快便有了结果,这些条约将授予投资者和国家一系列的权利和义务来培养外国直接投资,由于在0多边基础上包罗万象的改革的公布困难,这些主动权在很大程度上并不成功。

后来,许多国家转向双边条约去寻求国际投资者的权利,并且鼓励促进投资社会风气的稳定。

国家很快意识到投资条约能称为强化财产保护类型的主要工具,这将使创造财富的跨境资金流动更加便利,为主权国家和外国投资者带来净利润。

双边投资条约的存在与协商在国际公共政策的形成方面产生了重要影响,而且这些条约现已是国际关系的试金石。

如今,许多的投资条约在发达国家之间达成协议,发展中国家同样也在自身之间签订了投资协议,然而,许多投资条约最初只是在主要出口国和主要进口国之间签订。

由于投资继续在发达国家与发展中国家之间流动,投资协议已不能单纯从工业化国家的视角点出发来看了。

双边投资条约的数量近些年急剧增加,单在20世纪90年代,投资条约每天便以1%的比例达成。

一些多边投资条约也被通过。

同时,随着双边投资条约的数量增加了五倍,外国直接投资也经历着五倍的增长。

由于双边条约的成功,毫不奇怪,甚至更广阔区域的投资协定,如美洲自由贸易协定,也正在考虑之中。

(二)什么使得投资条约如此特殊?投资条约的激增部分是由于条约自身的权利。

投资条约有两项基础的创新,这两项创新都显示对先前的国际协定的一种违反。

第一,它们赋予投资者一系列特殊的独立存在的权利,这些权利帮助实现一项投资的稳定投资风气。

第二,它们向投资者提供违反那些独立的全力的直接救济办法。

其中第一点将会在这一部分中提出,这一方法所产生的直接权利的影响将在第二部分中进一步讨论。

投资条约的条款都大致相似,国家选择提供的权利中有一定的趋势,然而从特别条约的协商中产生的独立存在的特定权利义务也有一些变化。

通常来说,国家都统一在他们自己的领域内保护投资者的投资不受另一国的影响,为了实现这一承诺,他们详细的记述了管理主权国家一项投资待遇的特定的独立标准。

确切的说,条约暗示将会授予投资者什么样的权利、覆盖的投资类型以及这种范围开始以及结束的时间。

授予投资者独立存在的权利有不同的排列,一个典型的投资条约通常提供给投资者多达7项不同的独立的权利的联合体。

一是投资者有权在投资被征用的时间中获得对等的补偿金;二是国家禁止制定货币指导政策,以便促进资金的自由流通;三是国家不能因为国籍采取歧视政策,这主要意味着投资者不能受到比本国国民或他国国民更差的待遇;四是国家应承认公平且平等的对待投资;五是国家对一项投资应承诺提供全面的保护和安全;六是国家应保证投资者受到的待遇不低于国际惯例要求的最低标准;最后是国家有时应同意去尊重他们根据一项投资所做出的承诺。

这些权利中的一些是对国家在国际惯例下负有义务的一种确认,其他的都是新出的。

大多数条约详细记述了投资者和投资有权受到的独立保护措施。

授权保护的建立是一项重要的门槛文体,因为它允许投资者获得保护并且信赖投资条约的影响力。

必须满足的标准十分广泛,为了寻求一项投资条约的利益,必须有具有资格的个人和实体(属人要求),符合条件的事项(属物的要求)以及一项符合时限的纠纷(时间上的要求)。

这三个长期要求的影响在于与多国有关的投资可能允许投资者同时从多于一项投资条约中受益,这完全依赖于这项投资是如何构造的以及相关投资条约的规则。

例如,一个美国人通过荷兰的公司在捷克共和国进行投资,那么他可以享受美国与捷克共和国之间的双边投资条约下的权利,也可享受荷兰与捷克共和国之间双边投资条约下的权利。

这种可能性对投资者进行结构性投资是一种刺激,这种投资在非多边条约中可以给他们提供至少从一项投资条约的权利中受益的合法预期。

当同一组事实允许在不同条约下的仲裁时,这便加强了不一致裁决产生的可能性。

二、投资条约仲裁的影响随着投资条约的激增,投资者有了更多他们能用来起诉主权国家的条约。

这一部分考虑了投资仲裁的演进,给予投资者起诉主权国家一项直接的原因所带来的利益,投资仲裁的目前状态以及针对主权国家发起投资条约仲裁的实际程序。

(一)投资仲裁的演进自从至少1794年以来,仲裁已被作为一种培养外国投资以及提供解决国际纠纷中立场所的工具在使用。

即使国际仲裁由公平且内行的决定制定者发展成为一项独立规则的过程中有一些坎坷,但是仲裁现也已是解决复杂国际纠纷杰出的、且相对于其他选择更加可取的方法,其他方法如使用武力或者其他非常规方法(如闭门外交谈判)。

投资纠纷仲裁曾经并不向现在这样被广泛的使用。

这主要是因为私人投资者没有地位,而且缺乏针对主权国家违反国际法而损害其投资的直接的起诉理由。

相反,投资者被迫游说他们的母国在国际法庭根据他们的利益支持这一主张,这便导致投资纠纷的偶然发生以及更少的成功起诉案例。

在主权国家支持它的投资者的案件以及国际法庭确已发现违反了国际法的适当案例中存有两大缺陷。

首先,一个受损失的投资者将不能因为主权国家的非法行为而获得补偿。

第二,对于国际法庭,唯一可能的强制性工具是安理会决议的通过,但这在投资者寻求经济补偿时并不能获取利益。

由于这些限制,对于那些愤愤不平的投资者来说,存有的选择余地是在国内法院之前提起诉讼。

这一选择对于那些寄希望于他们能建立诉讼的多种根据的投资者来说并没有太大的吸引力,因为他们发现自己只是在一个主权国家起诉同一主权国。

在提出这些关心的努力中,投资条约对于投资为基础的纠纷解决有两项基础的转变。

一是条约给了投资者针对主权国家损害的一个直接的起诉理由,这意味着投资者在决定发起纠纷解决时不再任由国际政策和政府官僚体制的摆布了,并且能够避免他们之间通过更大的外国关系磋商所掩盖的诉讼。

第二,即使没有纠纷解决办法的单独条款,投资条约也给了投资者一个中立的选择来解决他们之间的不满。

总之,这些转变已经创造了一个诉讼的独立理由,这使得投资者像一个私人律师首领,并且将国际公法权利的执行置于独立的个人和法人手中。

这些转变是一项主要的创新。

他们创造了一种培养投资者信心的办法,使得他们相信在与东道国解决纠纷时,减少与投资者有关的风险以及可以证实增加对海外投资的刺激时将会受到公平待遇。

(二)投资仲裁的增加考虑到从1960年开始投资者就可以利用投资争端解决中心和有关投资的条约解决,但是令人有点吃惊的是仅在最近几年在投资条约下的争端提起的数量才有所增加。

可能随着近几年来外国投资的增多,更多投资条约的签定,解决争端的中立性的要求,仲裁也跟着发展起来了。

对于那些可以提出投资仲裁的机构提交解决投资争端国际中心的案件已经由1980年大约每年一件增加到2001年每个月一至二件。

《大西洋协议》的实践表明世界上的投资索赔案件的指数不断在突破。

特别在最近几年内,大量的投资条约仲裁案件急剧的上升。

解决投资争端国际中心的律师已经证实的有大量的投资条约仲裁案件的提交证明了这种趋势还在继续。

(三)什么是投资条约下的仲裁投资条约提供一个特别的争端解决机制,这种机制让投资者能够因为对方违反条约而寻求补偿,投资者可以直接提起仲裁而不是通过烦琐的程序或者国家法院来解决争端。

投资者不会轻易的请求政府提出仲裁,因为他们也意识到,如果让政府出面将会出现另外一种困境。