夹具设计英文文献

机械毕业设计英文外文翻译71车床夹具设计分析

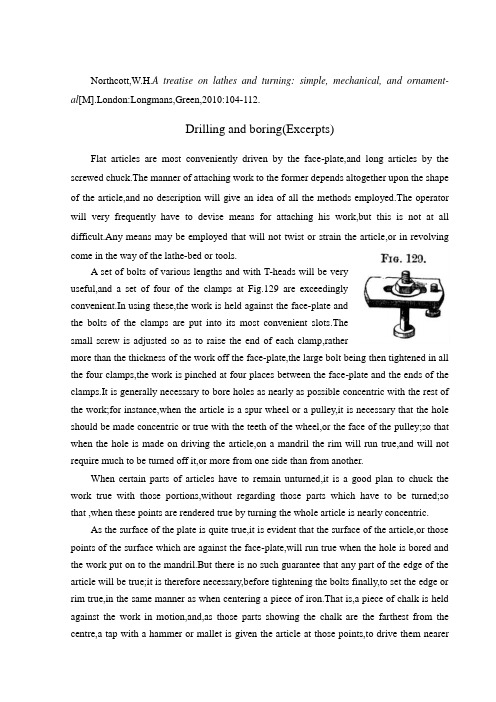

附录ALathe fixture design and analysisMa Feiyue(School of Mechanical Engineering, Hefei, Anhui Hefei 230022,China)Abstract: From the start the main types of lathe fixture, fixture on the flower disc and angle iron clamp lathe was introduced, and on the basis of analysis of a lathe fixture design points.Keywords: lathe fixture; design; pointsLathe for machining parts on the rotating surface, such as the outer cylinder, inner cylinder and so on. Parts in the processing, the fixture can be installed in the lathe with rotary machine with main primary uranium movement. However, in order to expand the use of lathe, the work piece can also be installed in the lathe of the pallet, tool mounted on the spindle.THE MAIN TYPES OF LATHE FIXTUREInstalled on the lathe spindle on the lathe fixtureInstalled in the fixture on the lathe spindle in addition to three-jaw chuck, four jaw chuck, faceplate, front and rear dial with heart-shaped thimble and a combination of general-purpose lathe fixture folder outside (as these fixtures have been standardized and machine tool accessories, can be purchased when needed do not have to re-design), usually need to design special lathe fixture. Common special lathe folder with the following types.Fixture took disc latheThis process is to find the generic is installed on the faceplate is difficult to ensure the accuracy of the workpiece, so the need to design special lathe fixture. The lathe fixture design process, first select the cylindrical workpieceand the end cylinder B, the semi-circular surface finishing (finishing second circularsurface when the car has been good with circular surface) ispositioned datum, limit of six degrees of freedom, in line with the principle of base overlap.The work piece fixture to ensure the accuracy of measures:The workpiece fixture to ensure the accuracy of measures:(1) tool by the workpiece machining position relative to the guarantee. (2) symmetry of size 0.02. Rely on sets of holes5.56h Φ22.5Φ0.023023+Φ0.023023+Φ180.02±and positioning theworkpiece with the precision of andlocate the position of dimensional accuracy and process specification requirements to ensure that the same parts of the four circular surface must be processed on the same pins.(3) all fixtures and clip bushing hole axis vertical concrete face A tolerance of .because the A side is the fixture with the lathe when the transition assembly base plate installed.(4) specific folder on the-hole plate with the transition to the benchmarks pin design requires processing each batch of parts to be sold in the transitional disk with a coat made of a tight match, and the local processing of the face plate to reduce the transition fixture on the set of small errors.The angle iron fixtureIf the processing technology for the and, drilling, boring, reaming process scheme. Boring is required in the face A face of finishing B ( range) and the A, B sides and the holeaxis face runout does not exceed . In addition, the processing of -hole, you should also ensure that its axis with the axis of thedegree of tolerance for the uranium ; size 5.56h Φ0.0100.00220.5++Φ0.005mm 207H Φ20Φ0.0102.5+Φ0.0110.00510++Φ12Φ10Φ0.02mm 2.5Φ0.0110.00510++Φ0.01mm Φ10Φand the location of ; and and of the axis of the axis of displacement tolerance not more than .Based on the above analysis on the part of process size, choose the -hole on the workpiece surface and M, N two planes to locate the benchmark.Installed on the lathe pallet fixtureLimited equipment in the factory, similar to the shape of the parts box, its small size, designed for easy installation without turning the main pumping in the fixture, you can drag the panel removal tool holder, fixture and workpiece mounted on the pallet. Processing, mounted on the lathe tool on the main primary uranium movement, feed the work piece for movement, so you can expand the scope of application of lathe.LATHE FIXTURE DESIGN POINTSThe design features of the positioning deviceLathe fixture positioning device in the design, in addition to considering the limited degrees of freedom, the most important thing is to make the surface of the workpiece axis coincides with the 15.50.1±80.1mm ± 2.5Φ10Φ17.5Φ0.02mm 17.5Φaxis of spindle rotation. This is described in the previous two sets of lathe fixture when special emphasis. In addition, the positioning device components in the specific folder location on the workpiece surface accuracy and dimensional accuracy of the location has a direct relationship, so the total figure on the fixture, be sure to mark the location positioning device dimensions and tolerances, and acceptance as a fixture conditions.Jig weight design requirementsProcessing in the lathe, the workpiece rotation together with the fixture will be a great centrifugal force and the centrifugal force increases sharply with increasing speed. This precision machining, processing, and the vibration would affect the surface quality of parts. Therefore, the lathe fixture between devices should pay attention to the layout of equipment necessary to balance the design weights.Dlamping device design requirementsLathe fixture in the course of their work should be the role of centrifugal force and cutting force, the size of its force and direction of the workpiece position relative to the base is changing. Therefore, a sufficient clamping device clamping force and a good self-locking.To ensure safe and reliable clamping. However, the clamping force can not be too large, and require a reasonable layout of the force, and will not undermine the accuracy of the location positioning device.Llathe fixture connection with the machine tool spindle design Lathe fixture connected with the spindle directly affects the accuracy of the rotary fixture accuracy, resulting in errors in the workpiece. Therefore, the required fixture rotation axis lathe spindle axis with high concentricity.Lathe fixture connected with the spindle structure, depending on the spindle when turning the front of the structure model is confirmed, by machine instructions or the manual check on. Lathe spindle nose are generally outside the car with cone and cone, or a journal and other structures with the flange end connections to the fixture base. Note, however, check the manual should be used with caution, because many manufacturers of machine tools, machine tools of similar size may differ. The most reliable method for determining, or to field measurements in order to avoid errors or losses. Determine the fixture and the spindle connecting structure, generally based on fixture size of the size of the radial: radialdimension less than , or small lathe fixture. Pairs of fixture requirements of the overall structureLathe fixture generally work in the state of the cantilever in order to ensure process stability, compact fixture structure should be simple, lightweight and safe, overhang length to as small as possible, the center of gravity close to the front spindle bearing. Fixture overhang length L and the ratio of outer diameter D profile can refer to the following values used:Less than the diameter D in fixture, ;Diameter D between the fixture in ,; Fixture diameter D is greater than , .To ensure security, installed in the specific folder on the components of the folder is not allowed out beyond the specific diameter, should also consider cutting the wound and coolant splash and other issues affecting safe operation.References140mm (23)D d <-150mm 1.25L D ≤150300mm :0.9L D ≤300mm 0.6L D ≤[1] Chen Guofu. Lathe fixture [J]. Mechanical workers. Cold, 2000 (12)[2] Dong Yuming. Yang Hongyu. Fixture design in the common problems [J]. Mechanical workers. Cold, 2005 (1)[3] Liu Juncheng The machine clamps the clamping force in the design process calculations [J]. tool technology, 2007 (6)附录B车床夹具设计分析(合肥学院机械工程系,安徽合肥230022)摘要:从车床夹具的主要类型着手,对花盘式车床夹具和角铁式夹具进行了介绍,并在此基础上分析了车床夹具设计要点。

夹具设计英文文献

A review and analysis of current computer-aided fixture design approachesIain Boyle, Yiming Rong, David C. BrownKeywords:Computer-aided fixture designFixture designFixture planningFixture verificationSetup planningUnit designABSTRACTA key characteristic of the modern market place is the consumer demand for variety. To respond effectively to this demand, manufacturers need to ensure that their manufacturing practices are sufficiently flexible to allow them to achieve rapid product development. Fixturing, which involves using fixtures to secure work pieces during machining so that they can be transformed into parts that meet required design specifications, is a significant contributing factor towards achieving manufacturing flexibility. To enable flexible fixturing, considerable levels of research effort have been devoted to supporting the process of fixture design through the development of computer-aided fixture design (CAFD) tools and approaches. This paper contains a review of these research efforts. Over seventy-five CAFD tools and approaches are reviewed in terms of the fixture design phases they support and the underlying technology upon which they are based. The primary conclusion of the review is that while significant advances have been made in supporting fixture design, there are primarily two research issues that require further effort. The first of these is that current CAFD research is segmented in nature and there remains a need to provide more cohesive fixture design support. Secondly, a greater focus is required on supporting the detailed design of a fixture’s physical structure.2010 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. Contents1. Introduction (2)2. Fixture design (2)3. Current CAFD approaches (4)3.1 Setup planning (4)3.1.1 Approaches to setup planning (4)3.2 Fixture planning (4)3.2.1 Approaches to defining the fixturing requirement (6)3.2.2 Approaches to non-optimized layout planning (6)3.2.3 Approaches to layout planning optimization (6)3.3 Unit design (7)3.3.1 Approaches to conceptual unit design (7)3.3.2 Approaches to detailed unit design (7)3.4 Verification (8)3.4.1 Approaches to constraining requirements verification (8)3.4.2 Approaches to tolerance requirements verification (8)3.4.3 Approaches to collision detection requirements verification (8)3.4.4 Approaches to usability and affordability requirements verification (9)3.5 Representation of fixturing information (9)4. An analysis of CAFD research (9)4.1 The segmented nature of CAFD research (9)4.2 Effectively supporting unit design (10)4.3 Comprehensively formulating th e fixturing requirement (10)4.4 Validating CAFD research outputs (10)5. Conclusion (10)References (10)1. IntroductionA key concern for manufacturing companies is developing the ability to design and produce a variety of high quality products within short timeframes. Quick release of a new product into the market place, ahead of any competitors, is a crucial factor in being able to secure a higher percentage of the market place and increased profit margin. As a result of the consumer desire for variety, batch production of products is now more the norm than mass production, which has resulted in the need for manufacturers to develop flexible manufacturing practices to achieve a rapid turnaround in product development.A number of factors contribute to an organization’s ability to achieve flexible manufacturing, one of which is the use of fixtures during production in which work pieces go through a number of machining operations to produce individual parts which are subsequently assembled into products. Fixtures are used to rapidly, accurately, and securely position work pieces during machining such that all machined parts fall within the design specifications for that part. This accuracy facilitates the interchangeability of parts that is prevalent in much of modern manufacturing where many different products feature common parts.The costs associated with fixturing can account for 10–20% of the total cost of a manufacturing system [1]. These costs relate not only to fixture manufacture, assembly, and operation, but also to their design. Hence there are significant benefits to be reaped by reducing the design costs associated with fixturing and two approaches have been adopted in pursuit of this aim. One has concentrated on developing flexible fixturing systems, such as the use of phase-changing materials to hold work pieces in place [2] and the development of commercial modular fixture systems. However, the significant limitation of the flexible fixturing mantra is that it does not address the difficulty of designing fixtures. To combat this problem, a second research approach has been to develop computer-aided fixture design (CAFD) systems that support and simplify the fixture design process and it is this research that is reviewed within this paper.Section 2 describes the principal phases of and the wide variety of requirements driving the fixture design process. Subsequently in Section 3 an overview of research efforts that havefocused upon the development of techniques and tools for supporting these individual phases of the design process is provided. Section 4 critiques these efforts to identify current gaps in CAFD research, and finally the paper concludes by offering some potential directions for future CAFD research. Before proceeding, it is worth noting that there have been previous reviews of fixturing research, most recently Bi and Zhang [1] and Pehlivan and Summers [3]. Bi and Zhang, while providing some details on CAFD research, tend to focus upon the development of flexible fixturing systems, and Pehlivan and Summers focus upon information integration within fixture design. The value of this paper is that it provides an in-depth review and critique of current CAFD techniques and tools and how they provide support across the entire fixture design process.2. Fixture designThis section outlines the main features of fixtures and more pertinently of the fixture design process against which research efforts will be reviewed and critiqued in Sections 3 and 4, respectively. Physically a fixture consists of devices that support and clamp a work piece [4,5]. Fig.1 represents a typical example of a fixture in which the work piece rests on locators that accurately locate it. Clamps hold the work piece against the locators during machining thus securing the work piece’s location. The locating units themselves consist of the locator supporting unit and the locator that contacts the work piece. The clamping units consist of a clamp supporting unit and a clamp that contacts the work piece and exerts a clamping force to restrain it.Typically the design process by which such fixtures are created has four phases: setup planning, fixture planning, unit design, and verification, as illustrated in Fig. 2 , which is adapted from Kang et al. [6]. During setup planning work piece and machining information is analyzed to determine the number of setups required to perform all necessary machining operations and the appropriate locating datums for each setup. A setup represents the combination of processes that can be performed on a work piece without having to alter the position or orientation of the work piece manually. To generate a fixture for each setup the fixture planning, unit design, and verification phases are executed.During fixture planning, the fixturing requirements for a setup are generated and the layout plan, which represents the first step towards a solution to these requirements is generated. This layout plan details the work piece surfaces with which the fixture’s locating and clamping units will establish contact, together with the surface positions of the locating and clamping points. The number and position of locating points must be such that a work piece’s six degrees of freedom (Fig. 3 ) are adequately constrained during machining [7] and there are a variety of conceptual locating point layouts that can facilitate this, such as the 3-2-1 locating principle [4]. In the third phase, suitable unit designs (i.e., the locating and clamping units) are generated and the fixture is subsequently tested during the verification phase to ensure that it satisfies the fixturing requirements driving the design process. It is worth noting that verification of setups and fixture plans can take place as they are generated and prior to unit design.Fixturing requirements, which although not shown in Kang et al.[6] are typically generated during the fixture planning phase, can be grouped into six classes ( Table 1 ). The ‘‘physical’’requirements class is the most basic and relates to ensuring the fixture can physically support the work piece. The ‘‘tolerance’’requirements relate to ensuring that the locating tolerances aresufficient to locate the work piece accurately and similarly the‘‘constraining’’ requirements focus on maintaining this accuracy as the work piece and fixture are subjected to machining forces. The ‘‘affordability’’ requirements relate to ensuring the fixture represents value, for example in terms of material, operating, and assembly/disassembly costs.The ‘‘collision detection’’ requirements focus upon ensuring that the fixture does not collide with the machining path, the work piece, or indeed itself. The ‘‘usability’’ requirements relate to fixture ergonomics and include for example needs related to ensuring that a fixture features error-proofing to prevent incorrect insertion of a work piece, and chip shedding, where the fixture assists in the removal of machined chips from the work piece.As with many design situations, the conflicting nature of these requirements is problematic. For example a heavy fixture can be advantageous in terms of stability but can adversely affect cost (due to increased material costs) and usability (because the increased weight may hinder manual handling). Such conflicts add to the complexity of fixture design and contribute to the need for the CAFD research reviewed in Section 3.Table 1Fixturing requirements.Generic requirement Abstract sub-requirement examplesPhysical ●The fixture must be physically capable of accommodatingthe work piece geometry and weight.●The fixture must allow access to the work piece features tobe machined.Toleranc e ●The fixture locating tolerances should be sufficient to satisfypart design tolerances.Constraining●The fixture shall ensure work piece stability (i.e., ensure thatwork piece force and moment equilibrium are maintained).●The fixture shall ensure that the fixture/work piece stiffness issufficient to prevent deformation from occurring that could resultin design tolerances not being achieved.Affordabilit y ●The fixture cost shall not exceed desired levels.●The fixture assembly/disassembly times shall not exceeddesired levels.●The fixture operation time shall not exceed desired levels. CollisionPrevention●The fixture shall not cause tool path–fixture collisions to occur.●The fixture shall cause work piece–fixture collisions to occur(other than at the designated locating and clamping positions).●The fixture shall not cause fixture–fixture collisions to occur(other than at the designated fixture component connectionpoints).Usabilit y ●The fixture weight shall not exceed desired levels.●The fixture shall not cause surface damage at the workpiece/fixture interface.●The fixture shall provide tool guidance to designated workpiece features.●The fixture shall ensure error-proofing (i.e., the fixture shouldprevent incorrect insertion of the work piece into the fixture).●The fixture shall facilitate chip shedding (i.e., the fixture shouldprovide a means for allowing machined chips to flow awayfrom the work piece and fixture).3. Current CAFD approachesThis section describes current CAFD research efforts, focusing on the manner in which they support the four phases of fixture design. Table 2 provides a summary of research efforts based upon the design phases they support, the fixture requirements they seek to address (boldtext highlights that the requirement is addressed to a significant degree of depth, whilst normal text that the degree of depth is lesser in nature), and the underlying technology upon which they are primarily based. Sections 3.1–3.4 describes different approaches for supporting setup planning, fixture planning, unit design, and verification, respectively. In addition, Section 3.5 discusses CAFD research efforts with regard to representing fixturing information.3.1. Setup planningSetup planning involves the identification of machining setups, where an individual setup defines the features that can be machined on a work piece without having to alter the position or orientation of the work piece manually. Thereafter, the remaining phases of the design process focus on developing individual fixtures for each setup that secure the work piece. From a fixturing viewpoint, the key outputs from the setup planning stage are the identification of each required setup and the locating datums (i.e., the primary surfaces that will be used to locate the work piece in the fixture).The key task within setup planning is the grouping or clustering of features that can be machined within a single setup. Machining features can be defined as the volume swept by a cutting tool, and typical examples include holes, slots, surfaces, and pockets [8]. Clustering of these features into individual setups is dependent upon a number of factors (including the tolerance dependencies between features, the capability of the machine tools that will be used to create the features, the direction of the cutting tool approach, and the feature machining precedence order), and a number of techniques have been developed to support setup planning. Graph theory and heuristic reasoning are the most common techniques used to support setup planning, although matrix based techniques and neural networks have also been employed.3.1.1. Approaches to setup planningThe use of graph theory to determine and represent setups has been a particularly popular approach [9–11]. Graphs consist of two sets of elements: vertices, which represent work piece features, and edges, which represent the relationships that exist between features and drive setup identification. Their nature can vary, for example in Sarma and Wright [9] consideration of feature machining precedence relationships is prominent, whereas Huang and Zhang [10] focus upon thetolerance relationships that exist between features. Given that these edges can be weighted in accordance with the tolerance magnitudes, this graph approach can also facilitate the identification of setups that can minimize tolerance stack up errors between setups through the grouping of tight tolerances. However, this can prove problematic given the difficulty of comparing the magnitude of different tolerance types to each other thus Huang [12] includes the use of tolerance factors [13] as a means of facilitating such comparisons, which are refined and extended by Huang and Liu [14] to cater for a greater variety of tolerance types and the case of multiple tolerance requirements being associated with the same set of features.While some methods use undirected graphs to assist setup identification [11] , Yao et al. [15] , Zhang and Lin [16] , and Zhang et al. [17] use directed graphs that facilitate the determination and explicit representation of which features should be used as locating datums ( Fig. 4 ) in addition to setup identification and sequencing. Also, Yao et al. refine the identified setups through consideration of available machine tool capability in a two stage setup planning process.Experiential knowledge, in the form of heuristic reasoning, has also been used to assist setup planning. Its popularity stems from the fact that fixture design effectiveness has been considered to be dependent upon the experience of the fixture designer [18] .To support setup planning, such knowledge has typically been held in the form of empirically derived heuristic rules, although object oriented approaches have on occasion been adopted [19] . For example Gologlu [20] uses heuristic rules together with geometric reasoning to support feature clustering, feature machining precedence, and locating datum selection. Within such heuristic approaches, the focus tends to fall upon rules concerning the physical nature of features and machining processes used to create them [21, 22]. Although some techniques do include feature tolerance considerations [23], their depth of analysis can be less than that found within the graph based techniques [24]. Similarly, kinematic approaches [25] have been used to facilitate a deeper analysis of the impact of tool approach directions upon feature clustering than is typically achieved using rule-based approaches. However, it is worth noting that graph based approaches are often augmented with experiential rule-bases to increase their overall effectiveness [16] .Matrix based approaches have also been used to support setup planning, in which a matrix defining feature clusters is generated and subsequently refined. Ong et al. [26] determine a feature precedence matrix outlining the order in which features can be machined, which is then optimized against a number of cost indicators (such as machine tool cost, change over time, etc.) in a hybrid genetic algorithm-simulated annealing approach through consideration of dynamically changing machine tool capabilities. Hebbal and Mehta [27] generate an initial feature grouping matrix based upon the machine tool approach direction for each feature which is subsequently refined through the application of algorithms that consider locating faces and feature tolerances.Alternatively, the use of neural networks to support setup planning has also been investigated. Neural networks are interconnected networks of simple elements, where the interconnections are ‘‘learned’’ from a set of example data. Once educated, these networks can generate solutions for new problems fed into the network. Ming and Mak [28] use a neural network approach in which feature precedence, tool approach direction, and tolerance relationships are fed into a Kohonen self-organizing neural network to group operations for individual features into setups.3.2. Fixture planningFixture planning involves the comprehensive definition of a fixturing requirement in terms ofthe physical, tolerance, constraining, affordability, collision prevention, and usability requirements listed in Table 1 , and the creation of a fixture layout plan. The layout plan represents the first part of the fixture solution to these requirements, and specifies the position of the locating and clamping points on the work piece. Many layout planning approaches feature verification, particularly with regard to the constraining requirements. Typically this verification forms part of a feedback loop that seeks to optimize the layout plan with respect to these requirements. Techniques used to support fixture planning are now discussed with respect to fixture requirement definition, layout planning, and layout optimization.Fig. 4. A work piece (a) and its directed graphs showing the locating datums (b) (adapted from Zhang et al. [17] ).3.2.1. Approaches to defining the fixturing requirementComprehensive fixture requirement definition has received limited attention, primarily focusing upon the definition of individual requirements within the physical, tolerance, and constraining requirements. For example, Zhang et al. [17] under-take tolerance requirement definition through an analysis of work piece feature tolerances to determine the allowed tolerance at each locating point and the decomposition of that tolerance into its sources. The allowed locating point accuracy is composed of a number of factors, such as the locating unit tolerance, the machine tool tolerance, the work piece deformation at the locating point, and so on. These decomposed tolerance requirements can subsequently drive fixture design: e.g., the tolerance of the locating unit developed in the unit design phase cannot exceed the specified locating unit tolerance. In a similar individualistic vein, definition of the clamping force requirements that clamping units must achieve has also received attention [29,30].In a more holistic approach, Boyle et al. [31] facilitate a comprehensive requirement specification through the use of skeleton requirement sets that provide an initial decomposition of the requirements listed in Table 1, and which are subsequently refined through a series of analyses and interaction with the fixture designer. Hunter et al. [32,33] also focus on functional requirement driven fixture design, but restrict their focus primarily to the physical and constraining requirements.3.2.2. Approaches to non-optimized layout planningLayout planning is concerned with the identification of the locating principle, which defines the number and general arrangement of locating and clamping points, the work piece surfaces they contact, and the surface coordinate positions where contact occurs. For non-optimized layoutplanning, approaches based upon the re-use of experiential knowledge have been used. In addition to rule-based approaches [20,34,35] that are similar in nature to those discussed in Section 3.1, case-based reasoning has also been used. CBR is a general problem solving technique that uses specific knowledge of previous problems to solve new ones. In applying this approach to layout planning, a layout plan for a work piece is obtained by retrieving the plan used for a similar work piece from a case library containing knowledge of previous work pieces and their layout plans [18,36,37]. Work piece similarity is typically characterized through indexing work pieces according to their part family classification, tolerances, features, and so on. Lin and Huang [38] adopt a similar work piece classification approach, but retrieve layout plans using a neural network. Further work has sought to verify layout plans and repair them if necessary. For example Roy and Liao [39] perform a work piece deformation analysis and if deformation is too great employ heuristic rules to relocate and retest locating and clamping positions.3.2.3. Approaches to layout planning optimizationLayout plan optimization is common within CAFD and occurs with respect to work piece stability and deformation, which are both constraining requirements. Stability based optimization typically focuses upon ensuring a layout plan satisfies the kinematic form closure constraint (in which a set of contacts completely constrain infinitesimal part motion) and augmenting this with optimization against some form of stability based requirement, such as minimizing forces at the locating and/or clamping points [40–42] . Wu and Chan [43] focused on optimizing stability (measuring stability is discussed in Section 3.4) using a Genetic Algorithm (GA), which is a technique frequently employed in deformation based optimization.GAs, which are an example of evolutionary algorithms, are often used to solve optimization problems and draw their inspiration from biological evolution. Applying GAs in support of fixture planning, potential layout plan solutions are encoded as binary strings, tested, evaluated, and subjected to ‘‘biological’’ modification through reproduction, mutation, and crossover to generate improved solutions until an optimal state is reached. Typically deformation testing is employed using a finite element analysis in which a work piece is discretized to create a series of nodes that represent potential locating and clamping contact points, as performed for example by Kashyap and DeVries [44] . Sets of contact points are encoded and tested, and the GA used to develop new contact point sets until an optimum is reached that minimizes work piece deformation caused by machining and clamping forces [45,46]. Rather than use nodes, some CAFD approaches use geometric data (such as spatial coordinates) in the GA, which can offer improved accuracy as they account for the physical distance that exists between nodes [47,48].Pseudo gradient techniques [49] have also been employed to achieve optimization [50,51]. Vallapuzha et al. [52] compared the effectiveness of GA and pseudo gradient optimization, concluding that GAs provided higher quality optimizations given their ability to search for global solutions, whereas pseudo gradient techniques tended to converge on local optimums.Rather than concentrating on fixture designs for individual parts, Kong and Ceglarek [53] define a method that identifies the fixture workspace for a family of parts based on the individual configuration of the fixture locating layout for each part. The method uses Procrustes analysis to identify a preliminary workspace layout that is subjected to pairwise optimization of fixture configurations for a given part family to determine the best superposition of locating points for a family of parts that can be assembled on a single reconfigurable assembly fixture. This buildsupon earlier work by Lee et al. [54] through attempting to simplify the computational demands of the optimization algorithm.3.3. Unit designUnit design involves both the conceptual and detailed definition of the locating and clamping units of a fixture, together with the base plate to which they are attached (Fig. 5). These units consist of a locator or clamp that contacts the work piece and is itself attached to a structural support, which in turn connects with the base plate. These structural supports serve multiple functions, for example providing the locating and clamping units with sufficient rigidity such that the fixture can withstand applied machining and clamping forces and thus result in the part feature design tolerances being obtained, and allowing the clamp or locator to contact the work piece at the appropriate position. Unit design has in general received less attention than both fixture planning and verification, but a number of techniques have been applied to support both conceptual and detailed unit design.3.3.1. Approaches to conceptual unit designConceptual unit design has focused upon the definition of the types and numbers of elements that an individual unit should comprise, as well as their general layout. There are a wide variety of locators, clamps, and structural support elements, each of which can be more suited to some fixturing problems than others. As with both setup planning and fixture layout planning, rule-based approaches have been adopted to support conceptual unit design, in which heuristic rules are used to select preferred elements from which the units should be constructed in response to considerations such as work piece contact features (surface type, surface texture, etc.) and machining operations within the setup [35,55–58]. In addition to using heuristic rules as a means of generating conceptual designs, Kumar et al.[59] use an inductive reasoning technique to create decision trees from which such fixturing rules can be obtained through examination of each decision tree path.Neural network approaches have also been used to support conceptual unit design. Kumar et al. [60] use a combined GA/neural network approach in which a neural network is trained with a selection of previous design problems and their solutions. A GA generates possible solutionswhich are evaluated using the neural network, which subsequently guides the GA. Lin and Huang[38] also use a neural network in a simplified case-based reasoning (CBR) approach in which fixturing problems are coded in terms of their geometrical structure and a neural network used to find similar work pieces and their unit designs. In contrast, Wang and Rong[37] and Boyle et al.[31] use a conventional CBR approach to retrieve units in which the fixturing functional requirements form the basis of retrieval, which are then subject to refinement and/or modification during detailed unit design.3.3.2. Approaches to detailed unit designMany, but not all systems that perform conceptual design also perform detailed design, where the dominant techniques are rule, geometry, and behavior based. Detailed design involves the definition of the units in terms of their dimensions, material types, and so on. Geometry, in particular the acting height of locating and clamping units, plays a key role in the design of individual units in which the objective is to select and assemble defined unit elements to provide a unit of suitable acting height [61,62]. An et al. [63] developed a geometry based system in which the dimensions of individual elements were generated in relation to the primary dimension of that element (typically its required height) through parametric dimension relationships. This was augmented with a relationship knowledge base of how different elements could be configured to form a single unit. Similarly, Peng et al. [64] use geometric constraint reasoning to assist in the assembly of user selected elements to form individual units in a more interactive approach.Alternatively, rule-based approaches have also been used to define detailed units, in which work piece and fixture layout information (i.e., the locating and clamping positions) is reasoned over using design rules to select and assemble appropriately sized elements [32,55,56] . In contrast, Mervyn et al. [65] adopt an evolutionary algorithm approach to the development of units, in which layout planning and unit design take place concurrently until a satisfactory solution is reached.Typically, rule and geometry based approaches do not explicitly consider the required strength of units during their design. However for a fixture to achieve its function, it must be able to withstand the machining and clamping forces imposed upon it such that part design tolerances can be met. To address this, a number of behaviorally driven approaches to unit design have been developed that focus upon ensuring units have sufficient strength. Cecil [66] performed some preliminary work on dimensioning strap clamps to prevent failure by stress fracture, but does not consider tolerances or the supporting structural unit. Hurtado and Melkote [67] developed a model for the synthesis of fixturing configurations in simple pin-array type flexible machining fixtures, in which the minimum number of pins, their position, and dimensions are determined that can achieve stability and stiffness goals for a work piece through consideration of the fixture/work piece stiffness matrix, and extended this for modular fixtures [68] . Boyle et al. [31] also consider the required stiffness of more complex unit designs within their case-based reasoning method. Having retrieved a conceptual design that offers the correct type of function, this design’s physical structure is then adapted using dynamically selected adaptation strategies until it offers the correct level of stiffness.3.4. VerificationVerification focuses upon ensuring that developed fixture designs (in terms of their setup plans, layout plans, and physical units) satisfy the fixturing requirements. It should be noted from。

汽车焊接夹具设计外文文献翻译

汽车焊接夹具设计外文文献翻译(含:英文原文及中文译文)文献出处:Semjon Kim.Design of Automotive Welding Fixtures [J]. Computer-Aided Design, 2013, 3(12):21-32.英文原文Design of Automotive Welding FixturesSemjon Kim1 AbstractAccording to the design theory of car body welding fixture, the welding fixture and welding bus of each station are planned and designed. Then the fixture is modeled and assembled. The number and model of the fixture are determined and the accessibility is judged. Designed to meet the requirements of the welding fixture.Keywords: welded parts; foundation; clamping; position1 IntroductionAssembly and welding fixtures are closely related to the production of high-quality automotive equipment in automotive body assembly and welding lines. Welded fixtures are an important part of the welding process. Assembly and welding fixtures are not only the way to complete the assembly of parts in this process, but also as a test and calibration procedure on the production line to complete the task of testing welding accessories and welding quality. Therefore, the design and manufacture ofwelding fixtures directly affect the production capacity and product quality of the automobile in the welding process. Automotive welding fixtures are an important means of ensuring their manufacturing quality and shortening their manufacturing cycle. Therefore, it is indispensable to correctly understand the key points of welding fixture design, improve and increase the design means and design level of welding fixtures, and improve the adjustment and verification level of fixtures. It is also an auto manufacturing company in the fierce competition. The problem that must be solved to survive.The style of the car is different from that of the car. Therefore, the shape of the welding jig is very different. However, the design, manufacture, and adjustment are common and can be used for reference.2. Structural design of welding fixtureThe structure design of the welding fixture ensures that the clip has good operational convenience and reliable positioning of the fixture. Manufacturers of welding fixtures can also easily integrate adjustments to ensure that the surfaces of the various parts of the structure should allow enough room for adjustments to ensure three-dimensional adjustment. Of course, under the premise of ensuring the accuracy of the welding jig, the structure of the welding jig should be as simple as possible. The fixture design is usually the position of all components on the fixture is determined directly based on the design basis, and ultimately ensure thatthe qualified welding fixture structure is manufactured. According to the working height, the height of the fixture bottom plate can be preliminarily determined, that is, the height of the fixture fixing position. The welding fixture design must first consider the clamping method. There are two types, manual and pneumatic. Manual clamping is generally suitable for small parts, external parts, and small batches of workpieces. For large body parts, planning in the production line, automation High-demand welding fixtures should be pneumatically clamped. Automobile production is generally pneumatically clamped, and manual mass clamping can be used as auxiliary clamping. This can reduce costs accordingly. Some manual clamping products already have standard models and quantities, which can be purchased in the market when needed. For some devices, pneumatic clamping is specified, but if pneumatic clamping is used, the workpiece may be damaged. Therefore, it is possible to manually press the place first to provide a pneumatic clamping force to clamp the workpiece. This is manual-pneumatic. . The fixture clamping system is mounted on a large platform, all of which are fixed in this welding position to ensure that the welding conditions should meet the design dimensions of the workpiece coordinate system positioning fixture, which involves the benchmark.3. Benchmarks of assembly and welding fixtures and their chosen support surfaces3.1 Determination of design basisIn order to ensure that the three-dimensional coordinates of the automatic weldment system are consistent, all welding fixtures must have a common reference in the system. The benchmark is the fixture mounting platform. This is the X, Y coordinate, each specific component is fixed at the corresponding position on the platform, and has a corresponding height. Therefore, the Z coordinate should be coordinated, and a three-dimensional XYZ coordinate system is established. In order to facilitate the installation and measurement of the fixture, the mounting platform must have coordinates for reference. There are usually three types. The structure is as follows:3.1.1 Reference hole methodThere are four reference holes in the design of the installation platform, in which the two directions of the center coordinates of each hole and the coordinates of the four holes constitute two mutually perpendicular lines. This is the collection on the XY plane coordinate system. The establishment of this benchmark is relatively simple and easy to process, but the measurements and benchmarks used at the same time are accurate. Any shape is composed of spatial points. All geometric measurements can be attributed to measurements of spatial points. Accurate spatial coordinate acquisition is therefore the basis for assessing any geometric shape. Reference A coordinated direction formed by oneside near two datums.3.1.2 v-type detection methodIn this method, the mounting platform is divided into two 90-degree ranges. The lines of the two axes make up a plane-mounted platform. The plane is perpendicular to the platform. The surface forms of these two axis grooves XY plane coordinate system.3.1.3 Reference block methodReference Using the side block perpendicular to the 3D XYZ coordinate system, the base of a gage and 3 to 4 blocks can be mounted directly on the platform, or a bearing fixing fixture platform can be added, but the height of the reference plane must be used to control the height , must ensure the same direction. When manufacturing, it is more difficult to adjust the previous two methods of the block, but this kind of measurement is extremely convenient, especially using the CMM measurement. This method requires a relatively low surface mount platform for the reference block, so a larger sized mounting platform should use this method.Each fixture must have a fixed coordinate system. In this coordinate system, its supporting base coordinate dimensions should support the workpiece and the coordinates correspond to the same size. So the choice of bearing surface in the whole welding fixture system 3.2When the bearing surface is selected, the angle between the tangentplane and the mounting platform on the fixed surface of the welding test piece shall not be greater than 15 degrees. The inspection surface should be the same as the welded pipe fittings as much as possible for the convenience of flat surface treatment and adjustment. The surface structure of the bearing should be designed so that the module can be easily handled, and this number can be used for the numerical control of the bearing surface of the product. Of course, designing the vehicle body coordinate point is not necessarily suitable for the bearing surface, especially the NC fixture. This requires the support of the fixture to block the access point S, based on which the digital surface is established. This surface should be consistent with the supported surface. So at this time, it is easier and easier to manufacture the base point S, CNC machining, precision machining and assembly and debugging.3.2 Basic requirements for welding fixtureIn the process of automobile assembly and production, there are certain requirements for the fixture. First, according to the design of the automobile and the requirements of the welding process, the shape, size and precision of the fixture have reached the design requirements and technical requirements. This is a link that can not be ignored, and the first consideration in the design of welding fixture is considered. When assembling, the parts or parts of the assembly should be consistent with the position of the design drawings of the car and tighten with the fixture.At the same time, the position should be adjusted to ensure that the position of the assembly parts is clamped accurately so as to avoid the deformation or movement of the parts during the welding. Therefore, this puts forward higher requirements for welding jig. In order to ensure the smooth process of automobile welding and improve the production efficiency and economic benefit, the workers operate conveniently, reduce the strength of the welder's work, ensure the precision of the automobile assembly and improve the quality of the automobile production. Therefore, when the fixture design is designed, the design structure should be relatively simple, it has good operability, it is relatively easy to make and maintain, and the replacement of fixture parts is more convenient when the fixture parts are damaged, and the cost is relatively economical and reasonable. But the welding fixture must meet the construction technology requirements. When the fixture is welded, the structure of the fixture should be open so that the welding equipment is easy to close to the working position, which reduces the labor intensity of the workers and improves the production efficiency.4. Position the workpieceThe general position of the workpiece surface features is determined relative to the hole or the apparent positioning reference surface. It is commonly used as a locating pin assembly. It is divided into two parts: clamping positioning and fixed positioning. Taking into account thewelding position and all welding equipment, it is not possible to influence the removal of the final weld, but also to allow the welding clamp or torch to reach the welding position. For truly influential positioning pins and the like, consider using movable positioning pins. In order to facilitate the entry and exit of parts, telescopic positioning pins are available. The specific structure can be found in the manual. The installation of welding fixtures should be convenient for construction, and there should be enough space for assembly and welding. It must not affect the welding operation and the welder's observation, and it does not hinder the loading and unloading of the weldment. All positioning elements and clamping mechanisms should be kept at a proper distance from the solder joints or be placed under or on the surface of the weldment. The actuator of the clamping mechanism should be able to flex or index. According to the formation principle, the workpiece is clamped and positioned. Then open the fixture to remove the workpiece. Make sure the fixture does not interfere with opening and closing. In order to reduce the auxiliary time for loading and unloading workpieces, the clamping device should use high-efficiency and quick devices and multi-point linkage mechanisms. For thin-plate stampings, the point of application of the clamping force should act on the bearing surface. Only parts that are very rigid can be allowed to act in the plane formed by several bearing points so that the clamping force does not bend the workpiece or deviate from thepositioning reference. In addition, it must be designed so that it does not pinch the hand when the clamping mechanism is clamped to open.5. Work station mobilization of welding partsMost automotive solder fittings are soldered to complete in several processes. Therefore, it needs a transmission device. Usually the workpiece should avoid the interference of the welding fixture before transmission. The first step is to lift the workpiece. This requires the use of an elevator, a crane, a rack and pinion, etc. The racks and gears at this time Structure, their structural processing, connection is not as simple as the completion of the structure of the transmission between the usual connection structure of the station, there are several forms, such as gears, rack drive mechanism, transmission mechanism, rocker mechanism, due to the reciprocating motion, shake The transfer of the arm mechanism to the commissioning is better than the other one, so the common rocker arm transfer mechanism is generally used.6 ConclusionIn recent years, how to correctly and reasonably set the auxiliary positioning support for automotive welding fixtures is an extremely complicated system problem. Although we have accumulated some experience in this area, there is still much to be learned in this field. Learn and research to provide new theoretical support for continuous development and innovation in the field of welding fixture design. Withthe development of the Chinese automotive industry, more and more welding fixtures are needed. Although the principle of the fixture is very simple, the real design and manufacture of a high-quality welding fixture system is an extremely complicated project.中文译文汽车焊接夹具的设计Semjon Kim1摘要依据车体焊装线夹具设计理论, 对各工位焊接夹具及其焊装总线进行规划、设计, 之后进行夹具建模、装配, 插入焊钳确定其数量、型号及判断其可达性,最终设计出符合要求的焊接夹具。

夹具设计外文翻译

Application and developmentOf case based reasoning in fixture designFixtures are devices that serve as the purpose of holding the workpiece securely and accurately, and maintaining a consistent relationship with respect to the tools while machining. Because the fixture structure depends on the feature of the product and the status of the process planning in the enterprise, its design is the bottleneck during manufacturing, which restrains to improve the efficiency and leadtime. And fixture design is a complicated process, based on experience that needs comprehensive qualitative knowledge about a number of design issues including workpiece configuration, manufacturing processes involved, and machining environment. This is also a very time consuming work when using traditional CAD tools (such as Unigraphics, CATIA or Pro/E), which are good at performing detailed design tasks, but provide few benefits for taking advantage of the previous design experience and resources, which are precisely the key factors in improving the efficiency. The methodology of case based reasoning (CBR) adapts the solution of a previously solved case to build a solution for a new problem with the following four steps: retrieve, reuse, revise, and retain [1]. This is a more useful method than the use of an expert system to simulate human thought because proposing a similar case and applying a few modifications seems to be self explanatory and more intuitive to humans .So various case based design support tools have been developed for numerous areas[2-4], such as in injection molding and design, architectural design, die casting die design, process planning, and also in fixture design. Sun used six digitals to compose the index code that included workpiece shape, machine portion, bushing, the 1st locating device, the 2nd locating device and clamping device[5]. But the system cannot be used for other fixture types except for drill fixtures, and cannot solve the problem of storage of the same index code that needs to be retained, which is very important in CBR[6].1. Construction of a Case Index and Case Library1.1 Case indexThe case index should be composed of all features of the workpiece, which are distinguished from different fixtures. Using all of them would make the operation in convenient. Because the forms of the parts are diverse, and the technology requirements of manufacture in the enterprise also develop continuously, lots of features used as the case index will make the search rate slow, and the main feature unimportant, for the reason that the relative weight which is allotted to every feature must diminish. And on the other hand, it is hard to include all the features in the case index.1.2 Hierarchical form of CaseThe structure similarity of the fixture is represented as the whole fixture similarity, components similarity and component similarity. So the whole fixture case library, components case library, component case library of fixture are formedcorrespondingly. Usually design information of the whole fixture is composed of workpiece information and workpiece procedure information, which represent the fixture satisfying the specifically designing function demand. The whole fixture case is made up of function components, which are described by the function components’ names and numbers. The components case represents the members. (function component and other structure components,main driven parameter, the number, and their constrain relations.) The component case (the lowest layer of the fixture) is the structure of function component and other components. In the modern fixture design there are lots of parametric standard parts and common non standard parts. So the component case library should record the specification parameter and the way in which it keeps them.2. Strategy of Case RetrievalIn the case based design of fixtures ,the most important thing is the retrieval of the similarity, which can help to obtain the most similar case, and to cut down the time of adaptation. According to the requirement of fixture design, the strategy of case retrieval combines the way of the nearest neighbor and knowledge guided. That is, first search on depth, then on breadth; the knowledge guided strategy means to search on the knowledge rule from root to the object, which is firstly searched by the fixture type, then by the shape of the workpiece, thirdly by the locating method. For example, if the case index code includes the milling fixture of fixture type, the search is just for all milling fixtures, then for box of workpiece shape, the third for 1plane+ 2pine of locating method. If there is no match of it, then the search stops on depth, and returns to the upper layer, and retrieves all the relative cases on breadth.2.1 Case adaptationThe modification of the analogical case in the fixture design includes the following three cases:1) The substitution of components and the component;2) Adjusting the dimension of components and the component while the form remains;3) The redesign of the model.If the components and component of the fixture are common objects, they can be edited, substituted and deleted with tools, which have been designed.2.2 Case storageBefore saving a new fixture case in the case library, the designer must consider whether the saving is valuable. If the case does not increase the knowledge of the system, it is not necessary to store it in the case library. If it is valuable, then the designer must analyze it before saving it to see whether the case is stored as a prototype case or as reference case. A prototype case is a representation that can describe the main features of a case family. A case family consists of those cases whose index codes have the same first 13 digits and different last three digits in the case library. The last three digits of a prototype case are always “000”. A reference case belongs to the same family as the prototype case and is distinguished by the different last three digits.From the concept that has been explained, the following strategies are adopted:1) If a new case matches any existing case family, it has the same first 13 digits as an existing prototype case, so the case is not saved because it is represented well by the prototype case. Or is just saved as a reference case (the last 3 digits are not “000”, and not the same with others) in the case library.2) If a new case matches any existing case family and is thought to be better at representing this case family than the previous prototype case, then the prototype case is substituted by this new case, and the previous prototype case is saved as a reference case.3) If a new case does not match any existing case family, a new case family will be generated automatically and the case is stored as the prototype case in the case library.3. ConclusionCBR, as a problem solving methodology, is a more efficient method than an expert system to simulate human thought, and has been developed in many domains where knowledge is difficult to acquire. The advantages of the CBR are as follows: it resembles human thought more closely; the building of a case library which has self learning ability by saving new cases is easier and faster than the building of a rule library; and it supports a better transfer and explanation of new knowledge that is more different than the rule library. A proposed fixture design framework on the CBR has been implemented by using Visual C ++, UG/Open API in U n graphics with Oracle as database support, which also has been integrated with the 32D parametric common component library, common components library and typical fixture library. The prototype system, developed here, is used for the aviation project, and aids the fixture designers to improve the design efficiency and reuse previous design resources.基于事例推理的夹具设计研究与应用夹具是以确定工件安全定位准确为目的的装置,并在加工过程中保持工件与刀具或机床的位置一致不变。

专业夹具设计全英文介绍

high precision, high efficiency, and high reliability are required to meet the high standards of automotive manufacturing.

01

Introduction to Fixture Design

Fixture

A device or system used to hold an object or a group of objects in a fixed position or orientation

Function

To provide stability, support, and positioning accuracy for manufacturing processes, such as machining, assembly, inspection, and testing

Ease of Assembly

Improve the ease of assembly and disassembly for fast production and lower maintenance costs

03

Professional fixture design application

Durability

The fixture must be durable and able to stand the rigors of the manufacturing environment

manufacturing process

Identify the specific needs and requirements of the manufacturing process, including the type of workpiece, the manufacturing operations required, and the tolerance required for the final product

机械加工工艺夹具类外文文献翻译、中英文翻译、外文翻译