文献翻译模板_理学院_本部

外文文献翻译模板

外文文献翻译模板广东工业大学华立学院本科毕业设计(论文)外文参考文献译文及原文系部管理学部专业人力资源管理年级 2008级班级名称 08人力资源管理1班学号 150********学生姓名王凯琪指导教师2012年 5 月目录1 外文文献译文 (1)2 外文文献原文 (9)德国企业中老化的劳动力和人力资源管理的挑战本文的主要目的就是提供一个强加于德国公司的人力资源管理政策上的人口变化主要挑战的概况。

尽管更多方面的业务受到人口改变的影响,例如消费的改变或储蓄和投资,还有资金的花费,我们把注意力集中劳动力老龄化促使人事政策的变化上。

涉及广泛的人力资源管理政策,以有关进行创新和技术变化的招募问题为开端。

1 老化的劳动力及人力资源管理由于人口的变化,公司劳动力的平均年龄在未来将会更年长。

因此,劳动力高于50的年龄结构占主导地位的集团不再是一个例外,并将成为一个制度。

在此背景下,年长的工人的实际份额,以及最优份额,部分是由企业特征的差异加上外在因素决定的。

2 一般的挑战尽管增加公众对未来人口转型带来的各种挑战的意识,公司对于由一个老化劳动力引起的问题的意识仍然是相当低的。

事实上,只有25%的公司预计人口统计的变化在长远发展看来将会导致严重的问题。

然而,现在越来越多关于老化劳动力呈现的挑战和潜在的解决方案的文献。

布施提出了一种分析老员工一般能力的研究文集,并给出有关于年长工人的人力资源政策的实例。

目前,华希特和萨里提出一篇关于研究公司对于提前退休的态度和延长工作生涯的态度的论文。

在这些研究中,老员工的能力通常被认为是不同的,并不逊色,同时指出一个最优的劳动力取决于不同的公司的特殊要求。

一般来说,然而由于越来越缺少合格的员工,人口统计的变化将使得在各种人事政策方面上的压力逐渐增加。

特别是,没有内部人力资源部门的中小型企业,因此缺乏足够的特殊的基础设施,则面临着严峻的挑战。

与他们正常的大约两到五年的计划水平相反,他们将越来越多地要处理长期的个人问题和计划。

英文文献翻译

Effects of Aromatic Carboxylic Dianhydrides on Thermomechanical Properties of Polybenzoxazine-Dianhydride CopolymersChanchira Jubsilp,1Boonthariga Ramsiri,2Sarawut Rimdusit21Department of Chemical Engineering,Faculty of Engineering,Srinakharinwirot University, Nakhonnayok26120,Thailand2Polymer Engineering Laboratory,Department of Chemical Engineering,Faculty of Engineering, Chulalongkorn University,Bangkok10330,ThailandEnhanced thermomechanical properties of bisphenol-A based polybenzoxazine(PBA-a)copolymers obtained by reacting bisphenol-A-aniline-type benzoxazine(BA-a)resin with three different aromatic carboxylic dianhy-drides,i.e.,pyromellitic dianhydride(PMDA),3,30,4,40 biphenyltetracarboxylic dianhydride(s-BPDA),or 3,30,4,40benzophenonetetracarboxylic dianhydride (BTDA)were reported.Glass transition temperature(T g), of the copolymers was found to be in the order of PBA-a:PMDA>PBA-a:s-BPDA>PBA-a:-BTDA.The difference in the T g of the copolymers is related to the rigidity of the dianhydride components.Furthermore,the T g of PBA-a:BTDA,PBA-a:s-BPDA,and PBA-a:BTDAfilms was observed to be significantly higher than that of the neat PBA-a owing to the enhanced crosslink density by the dianhydride addition.This greater crosslink density results from additional ester linkage formation between the hydroxyl group of PBA-a and the anhydride group of dianhydrides formed by thermal curing.Moreover,the copolymers exhibit enhanced thermal stability with ther-mal degradation temperature(T d)ranging from4108C to 4268C under nitrogen atmosphere.The char yield at 8008C of the copolymers was found to be remarkably greater than that of the neat PBA-a with a value up to 60%vs.that of about38%of the PBA-a.Toughness of the copolymerfilms was greatly improved compared to that of the neat PBA-a.POLYM.ENG.SCI.,52:1640–1648, 2012.ª2012Society of Plastics Engineers INTRODUCTIONRecently,there has been an increasing high tempera-ture requirement from the aerospace industry and other industrial applications such as composite matrices,pro-tecting coatings,and microelectronic materials using a thermosetting polymer.An improvement of polymeric material properties particularly by modification of the existing polymers through forming alloy,blend,or com-posite to achieve high thermal stability,high char yield, and high glass transition temperature becomes increas-ingly important[1–3].Polymer blends between polyben-zoxazines(PBZs)and other polymers have been subjected to many current investigations,which intend to utilize some outstanding properties of PBZs.Nowadays,there are various companies in the world which have produced benzoxazine resin for trading including multiplicity requirements of individual applications, e.g.,Shikoku Chemicals Corporation,Huntsman Corporation,and Hen-kel Co.,Ltd.PBZs are particularly applied to enhance the processability,mechanical,and thermal properties of the resulting polymer blends.They can be synthesized via a simple and cost-competitive solvent-less method[4].More-over,the molecular designflexibility of the resins,compa-rable to that of epoxy or polyimide(PI),provides wide range of properties that can be tailor-made.Importantly,the polymers have been reported to possess many intriguing properties to overcome several shortcomings of conven-tional novolac-and resole-type phenolic resins such as low viscosity,near-zero volumetric shrinkage upon curing,the glass transition temperature(T g)much higher than cure temperature,fast mechanical property build-up as a func-tion of degree of polymerization,high char-yield,low coef-ficient of thermal expansion,(CTE),low moisture absorp-tion,and excellent electrical properties[4,5].As mentioned above,the ability of benzoxazine resins to form alloys or blends with other polymers or resins[5–10]provides the resins with even broader range of applications.In recentCorrespondence to:Sarawut Rimdusit;e-mail:sarawut.r@chula.ac.thContract grant sponsor:New Researcher’s Grant of Thailand ResearchFund-Commission on Higher Education(TRF-CHE);Contract grantnumber:MRG5380077;Contact grant sponsor:Matching Fund of Srina-kharinwirot University(2010-2012);Contract grant sponsor:the HigherEducation Research Promotion and National Research University Projectof Thailand,Office of the Higher Education Commission;Contract grantnumber:AM1076A;Contract grant sponsor:100th Anniversary of Chu-lalongkorn University Academic Funding,CU;Contract grant sponsor:the Asashi Glass Foundation and Thai Polycarbonate Co.,Ltd.(TPCC).DOI10.1002/pen.23107Published online in Wiley Online Library().V C2012Society of Plastics EngineersPOLYMER ENGINEERING AND SCIENCE—-2012years,the investigation of PBA-a hybrid systems have been reported such as PBA-a/PU[6–8],PBA-a/phenolic novolac [10,11],PBA-a/epoxy resin[6,11,12],PBA-a/PI[13],and PBA-a/dianhydride[14,15].Interestingly,organic acid dianhydrides which contain aromatic structure and have high functionality have been found to impart improved heat resistance,as well as increased chemical and solvent resistance to the poly-meric materials such as epoxy resin[16,17]and PBA-a [18,19].The success of pyromellitic dianhydride (PMDA)and3,30,4,40benzophenonetetracarboxylic dia-nhydride(BTDA)as epoxy hardening agents is attributed to their tetrafunctionality,which leads to higher density of crosslinks,thus higher heat distortion temperature(HDT) and increased chemical and solvent resistance[17].Fur-thermore,muti-component polymeric materials of PBZ and aromatic carboxylic dianhydride-based PI have been investigated.Takeichi et al.[18]studied the thermal prop-erty of the polymer alloys between bisphenol-A-aniline-type polybenzoxazine(PBA-a)and PI based on bisphe-nol-A di(phthalic anhydride)ether(BPADA)and oxydia-niline(ODA).The authors reported that the T g of the PBA-a were improved significantly by blending with PI due to higher thermal stability of PI(T g of PI¼2228C) than that of the PBA-a,i.e.,1528C.Silicon-containing polyimide(SPI)has also been reported to provide significant enhancement on the decomposition temperature of PBA-a[13].The decompo-sition temperatures(T d s)of the blends increase from about3608C to4308C with the SPI content in range of0–75wt%.Interestingly,the char yields of the blends were substantially higher than that of the neat PBA-a and SPI. The highest char yield value at8008C of about45%was found at75wt%of the SPI content.This synergy in the char formation was also observed in the systems of PBA blended with other types of PIs[18].Recently,a novel PBA-a modified with dianhydride was successfully pre-pared by reacting bisphenol-A-aniline-based bifunctional benzoxazine resin(BA-a)with BTDA[14,15].The PBA-a:BTDA copolymer samples showed only one T g with the value as high as2638C at BA-a:BTDA¼1.5:1mole ra-tio.The value is remarkably higher than that of the unmodified PBA-a,i.e.,1788C.In addition,the resulting PBA-a:BTDA copolymer displays relatively high thermal stability with T d up to3648C and substantial enhancement in char yield of up to61%vs.that of38%of the PBA-a.In this study,we prepared a series of the high perform-ance copolymers of PBA-a and aromatic carboxylic dia-nhydrides,i.e.,PMDA,3,30,4,40biphenyltetracarboxylic dianhydride(s-BPDA),and BTDA.The effect of these ar-omatic carboxylic dianhydrides on thermomechanical properties of the obtained PBA-a:aromatic carboxylic dia-nhydride copolymers is investigated.As aforementioned, blending of the PBA-a with the PI or an aromatic carbox-ylic dianhydride is an excellent method to modify the properties of the PBA suitable for such applications as microelectronics or prepreg fabrication.EXPERIMENTALMaterialsMaterials used in this study are bisphenol-A-aniline-based bifunctional benzoxazine resin(BA-a),dianhy-drides,and1-methyl-2-pyrrolidone(NMP)as solvent.TheBA-a based on bisphenol-A,paraformaldehyde,and ani-line was synthesized according to the patented solvent-less technology[4].Bisphenol-A(polycarbonate grade)was provided by Thai Polycarbonate Co.,Ltd.(TPCC).Paraformaldehyde(AR grade)and aniline(AR grade)were purchased from Merck Co.and Panreac QuimicaSA,respectively.Aromatic carboxylic dianhydrides usedin this work were PMDA purchased from Acros organics,3,30,4,40-biphenyltetracarboxylic dianhydride(s-BPDA)obtained from Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency,JAXA,(Prof.R.Yokota),and BTDA supplied by SigmaAldrich Co.NMP solvent was purchased from FlukaChemical Co.All chemicals were used as-received. Preparation of Benzoxazine-DianhydrideCopolymer FilmsBA-a resin was blended with various types of dianhy-drides(DA)at BA-a:DA¼1.5:1mole ratio which is anoptimal composition with good thermomechanical proper-ties as reported in our previous work[14,15].The mix-tures,i.e.,BA-a:PMDA¼15:1mole ratio,BA-a:s-BPDA ¼1.5:1mole ratio,and BA-a:BTDA¼1.5:1mole ratio, were dissolved in NMP and stirred at808C until a clear ho-mogeneous mixture was obtained.The solution was cast onTeflon sheet and dried at room temperature for24h.Addi-tional drying was carried out at808C for24h in a vacuumoven followed by thermal curing at1508C for1h,1708Cfor1h,at1908C,2108C,2308C for2h each,and2408C for1h to guarantee complete curing of the mixtures. Characterizations of the SamplesFourier transform infrared spectra of fully cured sam-ples were acquired at room temperature using a SpectrumGX FTIR spectometer from Perkin Elmer with an attenu-ated total reflection(ATR)accessory.In the case of aBA-a resin and a pure aromatic carboxylic dianhydride,asmall amount of aromatic carboxylic dianhydride powderwas cast as thinfilm on a potassium bromide(KBr)win-dow.All spectra were taken with64scans at a resolutionof4cm21and in a spectral range of4000–400cm21.The glass transition temperature(T g)of all sampleswere examined using a differential scanning calorimeter(DSC)model2910from TA Instruments.The thermo-gram was obtained at a heating rate of108C/min from308C to3008C under nitrogen purging with a constantflowrate of50ml/min.A sample with a mass in a rangeof8–10mg was sealed in an aluminum pan with lid.TheDOI10.1002/pen POLYMER ENGINEERING AND SCIENCE—-20121641T g,DSC was obtained from the temperature at half extrap-olated tangents of the step transition midpoint.The dynamic mechanical analyzer(DMA)modelDMA242from NETZSCH was used to investigate theviscoelastic properties of all samples.The dimension ofthe samples was7.0mm310mm30.1mm.The testwas performed in a tension mode at a frequency of1Hzwith strain amplitude of0.1%and at a heating rate of2 8C/min from308C to4008C under constant nitrogenflow of80ml/min.The storage modulus(E0),loss modulus(E00),and loss tangent or damping curve(tan d)were thenobtained.The T g,DMA was taken as the maximum point onthe loss modulus curve in a DMA thermogram.Degradation temperature(T d)and char yield of allsamples were acquired using a Diamond TG/DTA fromPerkin Elmer.The testing temperature program wasramped at a heating rate of208C/min from308C to10008C under nitrogen purging with a constantflow of50ml/min.The sample mass used was measured to beapproximately8–15mg.The T d s and char yields of thesamples were reported at their10%weight loss and at8008C,respectively.RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONNetwork Formation by Thermal Cure ofPBA-a:Dianhydride CopolymersBA-a containing BTDA-type aromatic carboxylic dia-nhydride at BA-a:BTDA¼1.5:1mole ratio was selected to examine the curing reaction by DSC as displayed in Fig.1.From the DSC thermograms as line(a)in Fig.1, after vacuum drying at808C,BA-a:BTDA mixture showed endothermic peak at2008C which corresponded to boiling point of NMP solvent(b.p.¼2028C).This endothermic peak decreased with an increase of heat treatment temperature,and completely disappeared after heat treatment at1508C as line(b)in Fig.1.This implied that the NMP solvent was completely removed from the BA-a:BTDA mixture at this heat-treatment stage.Further-more,the BA-a:BTDA mixture possessed an exothermic peak at2458C as line(e)in Fig.1.The area under the exothermic peak was observed to decrease as the cure temperature increased,and completely disappeared after curing at2408C.This suggested that the fully cured stage of BA-a:BTDA¼1.5:1mole ratio was achieved at up to 2408C heat treatment.Additionally,we obtained similar fully cured samples of BA-a:PMDA¼1.5:1mole ratio as line(f)in Fig.1and BA-a:s-BPDA¼1.5:1mole ratio as line(g)in Fig.1after the same heat treatment up to 2408C.After thermal curing at elevated temperature up to 2408C,the obtained thickness of the transparent PBA-a:PMDA,PBA-a:s-BPDA,and PBA-a:BTDAfilms was about100l m as shown in Fig.2b–d.It is well known that PBA-afilm is very brittle and we could not bend the film more than as being shown in Fig.2a.Interestingly, all of PBA-a:PMDA,BA-a:s-BPDA,and BA-a:BTDA co-polymerfilms exhibited greatly improved toughness com-pared to the neat PBA-a as can be seen in Fig.2b–d.The flexibility enhancement of all copolymer samples due to additional ester linkages,structurallyflexible functional group,formed in the PBA-a network as a result quoted in previous publications[15,19].Furthermore,the tensile properties, e.g.,tensile modulus,tensile strength,and elongation at break,are displayed in Table1.From the ta-ble,we can see that the tensile modulus of all copolymer films were slightly higher than that of the neat PBA-a. Interestingly,tensile strength and elongation at break of the neat PBA-a were found to increase with an addition of PMDA or s-BPDA or BTDA dianhydrides.Especially, the tensile strength of PBA-a:aromatic carboxylic dianhy-dride copolymerfilms were observed to be about three times greater than that of the neat PBA-a.This behavior was attributed to ester linkage formation in copolymer structures.In addition,the great toughness showed a similar trend for all copolymer samples with that of the commercial PIfilms such as Kaptonfilm[20]and UPILEX-sfilm.Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy Investigation Chemical structures of BA-a,PBA-a,dianhydride modifiers,and their network formation reactionsbetween FIG.1.DSC thermograms of the benzoxazine blending with BTDA at 1.5:1mole ratio at various curing conditions:(a)608C,808C/24h,(b) 608C,808C/24hþ1508C/1h,(c)608C,808C/24hþ1508C,1708C/ 1h,(d)608C,808C/24hþ1508C,1708C/1hþ1908C,2108C/2h, (e)608C,808C/24hþ1508C,1708C/1hþ1908C,2108C,2308C/2h þ2408C/1h,(f)608C,808C/24hþ1508C,1708C/1hþ1908C,210 8C,2308C/2hþ2408C/1h(BA-a:s-BPDA¼1.5:1mole ratio),(g) 608C,808C/24hþ1508C,1708C/1hþ1908C,2108C,2308C/2hþ2408C/1h(BA-a:PMDA¼1.5:1mole ratio).1642POLYMER ENGINEERING AND SCIENCE—-2012DOI10.1002/penthe PBA-a and dianhydride modifiers were studied by FTIR spectroscopic technique.The FTIR spectra of BA-a resin and the PBA-a are previously reported in detail [18,21,22].Characteristic absorption bands of the BA-a resin were found at 1232cm 21assigned to C ÀÀO ÀÀC stretch-ing mode of oxazine ring whereas the band around 1497cm 21and 947cm 21were attributed to the tri-substituted benzene ring.Following the curing phenomenon,an infi-nite three dimensional network was formed from benzoxa-zine ring opening by the breakage of C ÀÀO bond and then the benzoxazine molecule transformed from a ring struc-ture to a network structure.During this process,the back-bone of benzoxazine ring,the tri-substituted benzene ring around 1497cm 21,became tetra-substituted benzene ring centered at 1488cm 21and 878cm 21which led to the formation of a phenolic hydroxyl group-based polyben-zoxazine (PBA-a)structure.In addition,an indication of ring opening reaction of the BA-a resin upon thermal treatment could also be observed from the appearance of a broad peak about 3300cm 21which was assigned to the hydrogen bonding of the phenolic hydroxyl group forma-tion.The chemical transformation of BA-a:PMDA,BA-a:s-BPDA,and BA-a:BTDA at 1.5:1mole ratio upon thermal curing was investigated and the resulting spectra are shown in Fig.3a–c.The important characteristic infra-red absorptions of the neat PBA-a structure were clearly observed as aforementioned.On the other hand,the aro-matic carboxylic dianhydride,i.e.,PMDA,s-BPDA,and BTDA,may be identified by a distinctive carbonyl band region.From the Fig.3a–c,the spectra of all aromatic carboxylic dianhydrides provided the strong carbonyl characteristic absorption peaks with component in the1860cm 21and 1780cm 21region.Moreover,all dianhy-drides also showed a strong C ÀÀO stretching band inrange of 1300–1100cm 21[15,23].After fully cured stage,the new absorption bands of PBA-a:PMDA,PBA-a:s-BPDA,and PBA-a:BTDA copolymers at 1.5:1mole ratio was observed.The phenomenon was ascribed to the appearance of carbonyl stretching bands of ester linkage [24].From the PBA-a:aromatic carboxylic dianhydride spectra in Fig.3a–c,we can see that the carbonyl stretch-ing bands of aromatic carboxylic dianhydride at 1860cm 21and 1780cm 21completely disappeared.It was sug-gested that the reaction between the phenolic hydroxyl group of the PBA-a and the anhydride group of the aro-matic carboxylic dianhydrides could occur to form ester linkage as evidenced by the observed peak in the spec-trum at 1730cm 21.In general,IR spectra for esters exhibit an intense band in the range 1750–1730cm 21of its C ¼¼O stretching band.This peak varies slightly depending on the functional groups attached to the car-bonyl with exemplification of a benzene ring or double bond in conjugation with the carbonyl which will bring the wavenumber down to 30cm 21.Furthermore,thecar-FIG. 2.Photographs of aromatic carboxylic dianhydride-modified PBA-a films:(a)PBA-a,(b)PBA-a:PMDA,(c)PBA-a:s-BPDA,(d)PBA-a:BTDA.TABLE 1.Tensile properties of PBA-a and aromatic carboxylic dianhydride-modified PBA-a copolymers.Samples (mole ratio)Modulus (GPa)Strength (MPa)Elongation (%)PBA-a2.1025 1.9PBA-a:PMDA (1.5:1) 2.6078 5.4PBA-a:s-BPDA (1.5:1) 2.6895 6.6PBA-a:BTDA (1.5:1)2.50886.0DOI 10.1002/penPOLYMER ENGINEERING AND SCIENCE—-20121643boxylic acid occurred after thermal curing of the PBA-a:aromatic carboxylic dianhydride mixture can also befollowed by monitoring a band at1650–1670cm21[25]and1613cm21[19]due to C¼¼O stretching.In addition,carboxylic acid shows characteristic CÀÀO stretching,in-plane and out-of-plane,and OÀÀH bending bands at1320–1210cm21,1440–1395cm21,and960–900cm21,respectively[23,26].As a consequence,we proposed areaction model of these PBA-a:aromatic carboxylic dia-nhydride copolymers as shown in Scheme1.The reactionmechanism was similar to the esterification of di-(2-ethyl-hexyl)phthalate and hydroxyl group of allyl alcohol[27]as well as the reaction between BTDA dianhydride andhydroxyl group of2-hydroxyethyl acrylate[28].More-over,the ester linkage formation in anhydride-cured ep-oxy resin systems has also been reported[29,30].FT-Raman analysis revealed that curing propagation of theepoxy-anhydride system mainly occurs by polyesterifica-tion between hydroxyl group of the ring-opened epoxideand anhydride groups.The decrease of epoxide ring at1260cm21and anhydride ring at1860cm21resulted in arelative increase of a new band observed at1734cm21due to ester group formation on curing[31].Dynamic Mechanical Properties of PBA-a:DiandydrideCopolymersViscoelastic properties of PBA-a:PMDA,PBA-a:s-BPDA,and PBA-a:BTDA copolymerfilms at a mole ratioof 1.5:1were evaluated and storage modulus(E0),lossmodulus(E00),and tan d are illustrated in Figs.4–6.Gen-erally,the storage modulus demonstrates the deformationFIG.3.FTIR spectra of PBA:PMDA(a),PBA-a:s-BPDA(b),PBA-a:BTDA(c).SCHEME1.Model reaction of dianhydride-modified polybenzoxazinecopolymers.1644POLYMER ENGINEERING AND SCIENCE—-2012DOI10.1002/penresistances of the material when external force is applied sinusoidally.The E 0at room temperature (258C)of the PBA-a:aromatic carboxylic dianhydride copolymer sys-tems shown in Fig.4exhibited values of 3.02GPa for PBA-a:PMDA, 3.42GPa for PBA-a:s-BPDA,and 2.94GPa for PBA-a:BTDA,which are higher than that of the neat PBA-a,i.e.,2.57GPa.We can see that the storage modulus of all PBA-a:aromatic carboxylic dianhydride copolymers is approximately equal to that of typical PI films with a reported value in the range of 2.3–3.0GPa such as in s-BPDA/ODA,ODPA/ODA,PMDA/ODA PIs [32,33],and fluorinated PI [34].Figure 5displays T g which shows the dimension stabil-ity,from the maximum point of a loss modulus curve,of the PBA-a:aromatic carboxylic dianhydride copolymers,i.e.,PBA-a:PMDA,PBA-a:s-BPDA,and PBA-a:BTDA at a fixed mole ratio of 1.5:1.From the figure,PBA-a and its copolymers showed only single T g which suggested that all the PBAa:aromatic carboxylic dianhydride copoly-mer films were a homogeneous network and no phase separation occurred.The ultimate T g value of the neat PBA-a was determined to be about 1788C and that of the copolymers,i.e.PBA-a:PMDA,PBA-a:s-BPDA,and PBAa:BTDA was found to be 3008C,2708C,and 2638C,respectively.That is the T g value of PBA-a was signifi-cantly enhanced by an incorporation of all aromatic car-boxylic dianhydrides.In addition,we can clearly see that the T g of the copolymers is in the order of PBA-a:PMDA [PBA-a:s-BPDA [PBA-a:BTDA which is a similar trend as that found in aromatic carboxylic dianhydride-based PI films derived from those dianhydrides,i.e.,PMDA,s-BPDA,BTDA mixed with DADE [35],and with ODA [36].This observed behavior is attributed to the nature of the stiffness/bulkiness of the dianhydride moieties and the bridging group in the dianhydrides whichstrongly affects T g of the copolymers.From our result,it is found that T g values of aromatic carboxylic dianhydride modified with PBA-a were decreased according to the increase of structural flexibility of selected dianhydrides.As expected,the PBA-a:PMDA film showed the highest T g due to the rigid pyromellitimide unit while the PBA-a:s-BPDA and the PBA-a:BTDA exhibited the lower T g than that of the PBAa:PMDA due to the presence of a more flexibility bridging group,i.e.,biphenyl and benzo-phenone units in a dianhydride structure [37,38].More-over,an enhanced crosslink density via ester linkage between phenolic hydroxyl group of PBA-a and anhydride group of dianhydride as depicted in FTIR spectra results in further T g improvement of the copolymers.In a tight network structure,in which rubbery plateau modulus is greater than 107Pa such as in our case,the non-Gaussian character of the polymer network becomes increasingly more pronounced and the equation from theory of rubbery elasticity is no longer applicable.The approximate rela-tion expressed in the equation below proposed by Nielsen and Landel [39]is thus preferred and is reported to better describe the elastic properties of dense network,e.g.,in epoxy systems [40,41].As a consequence,a crosslink density of these copolymer networks,q x ,can be estimated from a value of the equilibrium storage shear modulus inthe rubbery region (G e 0)which equals to E 0e 3as follow:log E0e 3¼7:0þ293r x ðÞ(1)where E 0e (dyne/cm 2)is an equilibrium tensile storage modulus in rubbery plateau,q x (mol/cm 3)is crosslink density which is the mole number of network chains per unit volume of thepolymers.FIG.4.Storage modulus of aromatic carboxylic dianhydride-modified PBA-a films:(l )PBA-a,(n )PBA-a:PMDA,(^)PBA-a:s-BPDA,(~)PBA-a:BTDA.FIG. 5.Loss modulus of aromatic carboxylic dianhydride-modified PBA-a films:(l )PBA-a,(n )PBA-a:PMDA,(^)PBA-a:s-BPDA,(~)PBA-a:BTDA.DOI 10.1002/penPOLYMER ENGINEERING AND SCIENCE—-20121645Crosslink density values of the PBA-a and its copoly-mers,i.e.,PBA-a:PMDA,PBA-a:s-BPDA,and PBA-a:BTDA at an equal mole ratio of 1.5:1,calculated from Eq.1are 3981mol/cm 3,8656mol/cm 3,7664mol/cm 3,and 7630mol/m 3,respectively.It is evident that the crosslink density of the neat PBA-a was greatly enhanced by an addition of PMDA,s-BPDA,or BTDA,correspond-ing to an enhancement in their T g values discussed previ-ously.An effect of crosslink density which is one key parameter on T g of aromatic carboxylic diandydride-modified PBA-a network can be accounted for using Fox–Loshaek equation [42].T g ¼T g ð1ÞÀkM nþk x r x (2)where T g ð1Þis glass transition temperature of infinite molecular weight linear polymer,k and k x are numerical constants,M n is number average molecular weight which equals infinity in a crosslinking system (therefore,thisterm,kM n,can be neglected),(x is the crosslink density.From the equation,the higher the crosslink density,the greater the T g of the copolymers,which was in excellent agreement with our DMA results.Loss tangent (tan d )of the PBA-a and their copoly-mers of various aromatic carboxylic dianhydride types is illustrated in Fig. 6.A peak height of tan d of PBA-a:PMDA,PBA-a:s-BPDA,and PBA-a:BTDA at an equal mole ratio of 1.5:1tended to decrease while the peak position of their copolymers clearly shifted to higher tem-perature.The results suggested that an increase in the crosslink density caused a restriction of the chain’s seg-mental mobility in aromatic carboxylic dianhydride-modi-fied PBA copolymers thus a more elastic nature of the copolymer films compared to the PBA-a.In addition,thewidth-at-half-height of tan d curves was found to be broader in their PBA-a copolymers,which indicated a more heterogeneous network in the resulting copolymers due to a hybrid polymer network formation.Moreover,the obtained transparent copolymer films and the single tan d peak observed in each copolymer suggested no mac-roscopic phase separation in these copolymer films.Thermal Stability of PBA-a:Dianhydride Copolymers Thermal stability of the PBA-a and their copolymers including PBA-a:PMDA,PBA-a:s-BPDA,and PBA-a:BTDA was investigated by thermogravimetric analysis (TGA).Figure 7compares TGA thermograms of the PBA-a and its copolymers in nitrogen atmosphere.From the figure,we can see that the degradation temperature (T d )reported at 10%weight loss of the neat PBA-a was 3618C while the T d of the copolymers increased in the order of PBAa:PMDA (4268C)[PBA-a:s-BPDA (4228C)[PBA-a:BTDA (4108C).In other words,the order of thermal stability (T d )with respect to aromatic skeleton of acid dianhydride component is phenylene unit [biphenyl unit [benzophenone unit [40].Furthermore,the T d value of the neat PBA-a film was observed to sig-nificantly increase with an incorporation of aromatic carboxylic dianhydrides.This is due to the formation of poly(aromatic ester)in the copolymers,i.e.,reported T d of polyester $320–4008C [43,44],which clearly had higher T d than the neat PBA-a.As previously reported in FTIR spectra,the formation of additional crosslinking sites via ester linkage between the anhydride group in the aromatic carboxylic dianhydride and hydroxyl group of the neat PBA-a thus clearly contributed this T d enhancement.In summary,the higher crosslink density and the presence of an aromatic structure of these aromatic carboxylicdianhy-FIG. 6.Loss tangent of aromatic carboxylic dianhydride-modified PBA-a films:(l )PBA-a,(n )PBA-a:PMDA,(^)PBA-a:s-BPDA,(~)PBA-a:BTDA.FIG.7.Thermal degradation of aromatic carboxylic dianhydride-modi-fied PBA-a films:(l )PBA-a,(n )PBA-a:PMDA,(^)PBA-a:s-BPDA,(~)PBA-a:BTDA.1646POLYMER ENGINEERING AND SCIENCE—-2012DOI 10.1002/pen。

文献翻译格式参考

Quantifying the Trade Effects of Technical Barriers to Trade: Evidence from China 1. IntroductionTechnical barriers to trade(TBT)are now widespread and have increasing impacts on international trade. The spread of TBT may have some special reasons.First, it’s legitimate. The WTO members are authorized by WTO TBT/SPS Agreement to take such measures in order to protect human health, as well as animal and plant health, provided that the enforced measures are not disguised protectionism. Second, as Baldwin (1970) emphasized, ―The lowering of tariffs has, in effect, been like draining a swamp. The lower water level has revealed all the snags and stumps of non-tariff barriers that still have to be cleared away‖. Wallner (1998) considered this phenomenon as a ―law of constant protection‖, referring to perfect substitutability between tariff and none-tariff barriers in maintaining a degree of desired domestic protection.Third, with the trade liberalization process, the remaining barriers, like TBT have a more important but not a less important impact due to the ―globalization magnification effect‖, seemingly minor differences in technical norms can have an outsized effect on production and trade (Baldwin 2000). Fourth, the increasing income of importing country and consumer preference may result in a higher demand for product quality, safety and environment protection.Since the proliferation of TBT and its increasing trade-restrictive impacts, OECD (2001) drew attention to TBT and suggested more empirical research on it, becausethe quantitative analysis is an important step in the regulatory reform process and can help inform governments to define more efficient regulations. However, due to the theoretical complexity and data s carcity, TBT have been considered as ―one of the most difficult NTBs imaginable to quantify‖ (Deardorff and Stern 1997)So far, there is not a preferred quantification strategy and claims abound on both sides about―whether such restrictions tend to reduce trade by virtue of raising compliance costsor expand trade by increasing consumer confidence in the safety and quality of imported goods‖ (Maskus and Wilson 2001).Maskus and Wilson (2001), Maskus, Otsuki, and Wilson (2001), Beghin and Bureau (2001), Ferrantino (2006) and Korinek, Melatos and Rau (2008) etc provide comprehensive overviews of key economic issues relating to TBT modeling and measurement. Based on these literatures, quantification techniques can be broadly grouped into two categories. Ex-post approaches such as gravity-based econometric models tend to estimate the observed trade impact of standards. On the other hand, ex ante methods such as simulations involving the calculation of tariff equivalents are usually employed to predict the unobserved welfare impact. No approach is or can bedefinitive. Each methodology offers its own pluses and minuses, depending on a number of factors, including the nature of the technical measure, the availability of data, and the goal of measurement. (Popper et al 2004)Concerning the trade effect1, different from any other trade measures, TBT have both trade promotion and trade restriction effects. Although a unified methodology does not exist, the gravity model is most often used for the evaluation. The gravity model employs a number of different approaches to measure the TBT. The policy indices obtained by survey can be used as proxy for the severity of TBT, and direct measures based on inventory approach are incorporated too. Beghin and Bureau(2001)summarized three sources of information that can be used to assess the importance of domestic regulations as trade barriers: (i) data on regulations, such as the number of regulations, which can be used to construct various statistical indicators,or proxy variables, such as the number of pages of national regulations; (ii) data on frequency of detentions, including the number of restrictions; frequency ratios and the import coverage ratio (iii) data on complaints from the industry against discriminatory regulatory practices and notifications to international bodies about such practices. Besides the above mentioned approach, some studies try to use explicit standards requirements such as maximum residue levels too.There are a considerable number of study combined the variable for the stringency of TBT with gravity model to estimate the direction of the trade impact.Swann, Temple, and Shurmer (1996) used counts of voluntary national and international standards recognized by the UK and Germany as indicators of standard over the period1985–1991, their findings suggest that share standards positively impact exports, but had a little impact on imports; unilateral standards positively influence imports but negatively influence exports. Moenius (2004, 2006) examines the trade effect of country specific standards and bilaterally shared standards over the period 1985-1995. Both papers used the counts of binding standards in a given industry as a measure of stringency of standards.Moenius (2004) focus on 12 OECD countries and found that at aggregate level, bilaterally shared standards and country-specific standards implemented by the importing or exporting country are both trade-promoting on average. At the industry level, the only variation is that importer-specific standards have the expected negative trade effect in nonmanufacturing sectors such as agriculture. In manufacturing industries, importer-specific standards are trade promoting too. Moenius (2006) confirm the result of Moenius (2004) in that bilateral standard in EU has very strong trade promoting effect as to the trade between EU and non-EU members, but harmonization decrease the internal trade of EU. Moenius (2006) distinguish 8 EU members and 6 non-EU developed countries. So he also found that importer specific standard in EU promote trade between EU members, but depress trade between EU members and non-EU members; Exporter specific standard inside EU has little trade promoting effect ,but export specific standard of non-EU members expand their tradewith EU.The paper using frequency or coverage ratio within a gravity model framework include Fontagné, Mimouni and Pasteels (2005) and Disdier, Fontagné, and Mimouni (2007). Both of them use the frequency ratio based on notification directly extracted from the TRAINS database. Fontagné, Mimouni and Pasteels (2005) collect data on 61 product groups, including agri-food products in 2001. Their paper generalized the findings of Moenius (2004): NTMs, including standards, have a negative impact on agri-food trade but an insignificant or even positive impact on the majority of manufactured products. Moreover, they distinguish trade effects among ―suspicious products‖, ―sensitive products‖ as well as ―remaining products‖ according to the number of notifications and distinguish different country group. Based on data covering 61 exporting countries and 114 importing countries, they find that over the entire product range, LDCs, DCs and OECD countries seem to be equally affected. However, OECD agrifood exporters tend to benefit from NTMs, at the expense of exporters from DCs and LDCs. The authors account for tariff and other NTM in the model , so they also find that tariffs matter more than NTMs, particularly foragri-food products on which comparatively high tariffs are levied.Disdier, Fontagné, and Mimouni (2008) estimate the trade effect of standards and other NTMs on 690 agri-food products (HS 6-digit level). Their data covers bilateral trade between importing OECD countries and 114 exporting countries (OECD and others) in 2004. As well as a frequency index, they use a dummy variable that records whether the importing country has notified at least one NTM and ad-valorem tariff equivalent measures of NTMs as two alternative approaches to measure NTMs. They find that these measures have on the whole a negative impact on OECD imports and affect trade more than other trade policy measures such as tariffs. The tariff equivalent shows the smallest effect. When they consider different groups of exporting countries, they show that OECD exporters are not significantly affected by SPS and TBTs in their exports to other OECD countries while developing and least developed countries’ exports are negatively and significantly affected. For the subsample of EU imports, NTMs no longer influence OECD exports positively, but exports from LDCs and DCs seem to be more negatively influenced by tariffs and SPS & TBTs than that of OECD. Finally, their sectoral analysis suggests an equal distribution of negative and positive impacts of NTBs on agricultural trade.Many studies are supportive of using maximum residue levels to directly measure the severity of food safety standards within a gravity model. These studies include Otsuki, Wilson and Sewadeh (2001a, b), Wilson and Otsuki (2004b,c) Wilson,Otsuki and Majumdsar (2003), Lacovone (2003) and Metha and Nambiar(2005). These studies tend to focus on specific cases of standards for particular products and countries. Otsuki, Wilson and Sewadeh (2001a,b) and Wilson and Otsuki (2004b) examine the trade effect of aflatoxin standards in groundnuts and other agriculturalproducts (vegetables,fruits and cereals). The first two papers covered African export data to EU members and the third paper covered 31 exporting countries (21 developing countries) and 15 importing countries(4 developing countries). All three studies show that imports are greater when the importing country imposes less stringent aflatoxin standards on foreign products. Lacovone (2003) also used MRL of aflatoxin and found that there were substantial export losses to Latin-America from the tightening of the aflatoxin standards set by Europe. Similarly, Wilson, Otsuki and Majumdsar (2003) analyze the effect of standards for tetracycline residues on beef trade and find that regardless of the exporter standards, the standards of tetracycline imposed by the importing countries have the same negative trade impact. Wilson and Otsuki (2004c) analyze MRL relating to chlorpyrifos and Metha and Nambiar(2005)analyze the impact of MRL on India’s export of four processing agri-products to 7 developed countries and yield the similar result.Since our paper focus on the trade effect of technical barrier, we will use the most suitable ex post quantification methods. Moreover, while frequency and coverage ratio can give some guidance as to the potential trade impact of a technical measure, econometric model is used to estimate its magnitude.Our paper make contributions to the current literature in the following ways: First, in contrast to the existing empirical studies which exclusively focus on developed countries TBT, this paper focuses on a developing country, China. Second, this paper has a self-constructed trade measure database based on disaggregated data covered all HS2 products, including agricultural and processing food products (HS01-24) and manufacturing products (HS25-97) so that it can identify the sectors/products with predominant negative impacts on trade. Third, tariff data, import licenses and quotas are included as additional explanatory variables, allowing the distinction between the impact of traditional trade barriers and TBT on trade. Fourth, our data covers 43 exporting countries (including 25 developing countries), it helps to distinguish the trade effect of different country groups. Fifth, in contrast to most literature relied on cross-section data1, our paper covers 9 years time series data on TBT, so we can both capture variation across products and variation within products over time, in particular the changing effects before and after China’s entry into the WTO.The rest of the paper is organized as follows. In section 2, we construct a TBT database from 1998 to 2006 and use inventory approach (frequency index and coverage ratio) to quantify the stringency of technical measures in China. In section 3, we present our regression model, discuss all the variables and describe the data. In section 4, we discuss our findings. We make some concluding remarks in section 5. 2. Quantification of TBT2.1 Measurement of NTM: Inventory approachThe inventory approach allows estimates of the extent of trade covered by NTMs or their frequency of application in specific sectors or against individual countries orgroups of countries. Bora etc (2002) reviews various approaches to quantify NTMs and give a detailed instruction on how to construct frequency index and coverage ratio as follows. The percentage of trade subject to NTMs for an exporting country j at a desired level of product aggregation is given by the trade coverage ratio:2.2 China’s NTM database: data description and methodologyFollowed the method described above, we will construct a Chinese NTMs database from 1998 to 2006 by using inventory approach. The data covered 96 HS2 digit level agricultural and manufacturing industries. First, we calculate a series of frequency index at 4-digit-level of the Harmonized System and then aggregate them into import coverage ratio at HS2. In this database, data are collected by tariff item on the application of a range of tariff and NTMs (TBT, license and import quota) against Chinese imports. The main source of the information on the trade control measures in the database is from Chinese government publications. ―Administrative Measures Regarding Impor t & Export Trade of the People's Republic of China‖ published bythe Ministry of Commerce and Custom General Administration of China provide detailed information at HS 8-digit-level on tariff and non-tariff measures.The code list of supporting documents subject to customs control provide detailed name of licenses or instruments of ratification, which helps to identify whether a tariff line product subject to a specific non-tariff barrier. Concerning the technical measures, it includes those government administrative measures for environmental protection, safety, national security and consumer interests. The code subject to TBT control remains almost the same during the 1998-2001. Specificly, the code subject to TBT in 1998 is IRFM, denoting for Import commodity inspection (I), Quarantine control release for animal, plant and thereof product (R), Import food inspection certificate (F) and Medicine inspection certificate (M). The code concerning TBT in 1999-2001 is AMPR, denoting for Import inspection and quarantine (A), Import commodity inspection (M), Import animal, plant and thereof product inspection (P) and Import food hygiene supervision inspection (R). Since 2002, the government revised the code list into details. Although there is some tiny difference between years, the new code list remains quite stable during 2002-2006 (See the code list in Annex1). The code subject to TBT is ACFIPQSWX during 2002-2005 and AFIPQSWX in 2006, each code stands for Certificate of inspection for goods inward (A), Certificate of inspection for goods inward: Civil commodity import inspection (C), Import licencing certificate for endangered species (F), Import or export permit for psychotropic drugs (I), Import permit for waste and scraps (P), Report of inspection of soundness on import medicines (Q), Import or export registration certificate for pesticides (S), Import or export permit for narcolic drugs (W), Environment control release noticefor poisonous chemicals (X).Note that our data on trade control measures do not have a bilateral dimension. TBT measures, import license and import quotas are enforced unilaterally by Chinese government and applicable to all exporting countries. When we calculate coverageratio and frequency ratio, Vi is the total value of imports in product i from the whole world and Mi indicates whether there are imports from the whole world of good i. Hence, in a specific year, NTM variables vary among different sectors but remain the same among different countries. Although we miss the bilateral dimension associated with such measures, still the exporters are differently affected by TBT measures depending on the structure of their exports in terms of products and markets.To be precise, the frequency ratio of TBT (FR-TBT) measures the proportion of product items covered by TBT measures within a product category, which varies between 0% (no coverage) and 100% (all products covered). We first count the number of HS items (defined at the 8 digit level of the HS) covered by the TBT measures and divide it by the maximum number of product items belonging to the product category (defined here at the 4-digit level of the HS). So we get the results of frequency ratio of TBT at HS4 digit level. For example, regarding HS2402 (Cigars, cheroots, cigarillos and cigarettes, of tobacco or of tobacco substitutes), there are 3 product items with codes 24021000 (Cigars, cheroots and cigarillos, containing tobacco), 24022000 (Cigarettes containing tobacco), 24029000(other). Only one of them (HS24022000) is covered by TBT measures, so the corresponding TBT frequency index equals 33.33% (1 / 3). Then we do the same at HS2 digit level.The import coverage ratio(IC-TBT) measures the proportion of affected import of the total import within a product category. Take HS17 (Sugars and sugar confectionery) as an example, there are 4 product items with code HS1701, 1702, 1703 and 1704 respectively. Only three of them (except HS1703) are covered by TBT measures (it means the frequency index for HS1703 equals 0, while the other three are between 0 and 100%), the import value of the TBT affected products sum up to 111.216 million US$, the import valued of HS17 is 182.244 million US$, so the corresponding TBT import coverage ratio equals 66.46% (111.216/182.244).2.3 TBT rocked sectors in ChinaBy calculating frequency index and import coverage ratio of TBT, we can examine which products are the most affected. According to the definition by UNCTAD (1997), those with a frequency ratio and coverage ratio both above 50% are TBT rocked product. In our sample, 34 products(HS01-24; HS30,31,33; HS 41;HS 44-47; HS51 and HS72)are TBT-rocked during the period from 1998-2002. In 2003, two product items (HS 42-43) become TBT-rocked. In 2004, two more products (HS 50 and HS80) added into the category. During 2005-2006, HS78 are included asTBT-rocked products but HS50 is excluded. See Annex2 for the detailed product information of TBT rocked products.There are a significant number of products, particularly agricultural products and processing food widely affected by technical measures (HS01-24). However, enforcement of TBT is not limited to those products, but is spreading to manufacturing products also. The TBT rocked manufacturing products includePharmaceutical products(HS30, Essential oils, perfumes, cosmetics, toiletries (HS33), Raw hides and skins, leather, furskins and articles thereof (HS41-43), Wood and articles of wood(HS44-46), Base metals and articles thereof, like iron and steel, aluminium and tin.( HS72, 76 and 80) etc. They are either labor intensive products or final goods concerning consumer safety, like medicaments in particular. Although TBT rocked sectors cover about 1/3 of total number of products at HS2 digit level, the proportion of affected trade is limited: about 10-16% of total import. However technical barriers are the most frequent type of NTM, the import subject to TBT account for above 90% of Chinese total import except for the rare case in 2001 (77.29%). (see Table 1).3. Model, methodology and data3.1 Model specificationWe use gravity model to examine how TBT imposed by China influence the country’s bilateral trade. To capture the size effect, population of both countries is used as proxy for exporting country’s supply capacities and importing country’s demand capacity. Per capita income of the two countries is included because higher income countries trade more in general. Transport costs are measured using the bilateral distance countries’ cultural proximity. We therefore control for this p roximity by introducing a common language dummy variable. Based on the typical gravity model, we introduce our key variables—tariff and non-tariff trade barriers. Our basic regression model takes the following forms:4. Empirical results4.1 The whole sample resultsTable 2-1 shows the summary statistics of our key variables. Table 2-2 reports the Pearson coefficients of the trade control measure variables. For the frequency index, import license and tariff appear to be negatively correlated. For the coverage ratio, besides import license, TBT seems to be slightly negative correlated with the tariff. Except for the above rare cases, the import control policies are positively correlated to each other. In general, different kinds of import control measures in China seem to be complementary to each other. Among them, import license and import quota have the highest positive coefficient, this accords with the fact that these two measures are sometimes combined together. Normally a country will distribute quota by issuing import license.We use OLS to estimate the gravity model. Regressions are run on pooled data for 9 years (see Table 3 and 4) and on data for each year separately (see Table 5 and 6). Table 3 and 5 report the result using frequency index, while Table 4 and 6 report the result using coverage ratio, both at HS 2-digit-level. For the whole sample regression results in Table 3 and 4, column 1 shows the result of the basic gravity model, column 2 introduces tariff and non-tariff barriers, column 3 tries to identify the difference between developing and developed countries and column 4 adds WTO as an additional control variable. Year-country-product fixed effect is used for all thespecifications.The results for standard gravity explanatory variables are consistent with prior expectations except for Contig as a rare case. The effect of GDPPC, POP and dist is positive and highly significant for all regressions. It implies that a 1 percent increase in the population of exporting country yields a 1.39-1.47 percent increase in the bilateral trade, and a 1 percent increase in the per capita GDP of exporting country yields a 0.91-1.40 percent increase in the bilateral trade. A 1 percent increase in geographic distance between the two trade partners will result a 1.42-1.45 percent decrease in bilateral trade. The effect of POPchina and GDPPCchina is positive and significant in two regressions. If Chinese population or per capita GDP increase 1 percent, Chinese import will increase 10.8-14.1 percent or 2.0-2.8 percent respectively. The coefficient for Comlang is positively significant in all specifications, which implies that if the exporting country share a same language with China, Chinese import will be stimulated by 2.6-3.3 percent. If the exporting market belongs to China, it will increase Chinese import by 0.3 percent. The coefficient for Contig is significantly negative, which implies that if the exporting country and China are contiguous, Chinese import will decrease 0.76-0.99 percent. This result is not consistent to the prior expectation. But the intuition is easily understood because the most important importing markets such as the US, Japan, EU members are not contiguous with China mainland.We then discuss the key explanatory variable, Tariff have a significant negative effect on Chinese import. A 1 percent increase in the MFN tariff will decrease import value by 0.64-0.66 percent. The results of the frequency index of NTM are all significant. A 1 unit increase in FRTBT will decrease import value by 1.1%, a 1 unit increase in FRQ will decrease import value by 1.7%, a 1 unit increase in FRL will increase import value by 4.1%. The results of the coverage ration of NTM are different in some extent with that of frequency index. A 1 unit increase in ICTBT will increase import value by 0.2%, a 1 unit increase in ICL will increase the import value by 2.7%, and the coefficient for ICQ is negative but not statistically significant.Table 5 and 6 give us a clear picture about how the effect of trade control measures change yearly. Tariff remains negatively significant for all 9 years.Moreover, the elasticity for Tariff dramatically increased since 2003. The trade depressing effect of Tariff nearly doubled after China’s entry into the WTO. FRTBT is negatively significant in all year specifications, and the coefficient remains stable through the sample period. FRL is positively significant while FRQ is negatively significant except for three years. In 1998, 1999 and 2001, FRL is insignificant while FRQ is positively significant due to the multicollinearity1. The result of ICTBT is changeable during the sample period. The coefficient of ICTBT is positively significant during 1998-2002, negatively significant in 2003 and insignificant during the remaining years. ICL remains positively significant during all 9 years, plus the elasticity for ICL slightly increased since 2002. ICQ is significant during 1998-2002,but the sign of the coefficient is changeable, and ICQ becomes insignificant since 2003. So ICQ doesn’t affect bi lateral trade value in a systematic way. From the yearly result, we observe that some of the trade control measure change trade patterns in a different way. Does the trade effect change significantly before and after China entry into the WTO? Whether there is any systematic difference in the trade effect between developing and developed countries? To solve these two problems, we add two interactions. Column 5 introduces the interaction between Developing and each of frequency indices of trade measures. Column 6 adds the interaction between WTO and each of coverage ratios of trade measure. As we can see, tariff (Tariff) and import quota (FRQ and ICQ) seem to have no difference between difference country groups. The change of FRTBT will affect Chinese import from developing countries less than that from developed countries. The change of ICTBT will affect Chinese import from developing countries more than that from developed countries. The change in FRL or ICL will have less impact on Chinese import from developing countries than from developed countries. On average, tariff, license have an increasing effect but quota has a decreasing effect after China’s entry into the WTO. The effect of TBT does not change significantly.5. ConclusionThe results of current literature suggest that TBT in importing country has restrictive trade effect and exports of poor countries are affected more. The paper explores whether technical measures imposed by China have restrictive effects for the imports from main exporters all over the world. Our research confirms some of the results reported elsewhere in the literature while differences remain in some aspects.First, in general trade control measures do have import restrictive effect in China. Second, tariff plays an important r ole even after China entry into the WTO. So far it’s still the most efficient policy tool. Third, TBT is the most frequently used NTM in China and cover almost all the imports. TBT do have some trade depressing effect but the effect is relatively small compared to the effect of tariff. Fourth, in contrast to the general belief that TBT works as a substitute to tariff and traditional NTM in developed countries(Thonsbury1998, Abbott 1997 etc), there is no obvious substitution effect between tariff and TBT in China, moreover, the TBT is complementary to tariff in some extent.定量商业作用技术贸易壁垒:证据从中国1. 介绍技术贸易壁垒TBT现在普遍并且增加了对国际贸易的冲击。

(完整word版)光学外文文献及翻译

学号2013211033 昆明理工大学专业英语专业光学姓名辜苏导师李重光教授分数导师签字日期2015年5月6日研究生部专业英语考核In digital holography, the recording CCD is placed on the ξ-ηplane in order to register the hologramx ',y 'when the object lies inthe x-y plane. Forthe reconstruction ofthe information ofthe object wave,phase-shifting digital holography includes two steps:(1) getting objectwave on hologram plane, and (2) reconstructing original object wave.2.1 Getting information of object wave on hologram plateDoing phase shifting N-1 times and capturing N holograms. Supposing the interferogram after k- 1 times phase-shifting is]),(cos[),(),(),,(k k b a I δηξφηξηξδηξ-⋅+= (1) Phase detection can apply two kinds of algorithms:synchronous phase detection algorithms [9]and the least squares iterative algorithm [10]. The four-step algorithm in synchronous phase detection algorithm is in common use. The calculation equation is)2/3,,(),,()]2/,,()0,,([2/1),(πηξπηξπηξηξηξiI I iI I E --+=2.2 Reconstructing original object wave by reverse-transform algorithmObject wave from the original object spreads front.The processing has exact and clear description and expression in physics and mathematics. By phase-shifting technique, we have obtained information of the object wave spreading to a certain distance from the original object. Therefore, in order to get the information of the object wave at its initial spreading position, what we need to do is a reverse work.Fig.1 Geometric coordinate of digital holographyexact registering distance.The focusing functions normally applied can be divided into four types: gray and gradient function, frequency-domain function, informatics function and statistics function. Gray evaluation function is easy to calculate and also robust. It can satisfy the demand of common focusing precision. We apply the intensity sum of reconstruction image as the evaluation function:min ),(11==∑∑==M k Nl l k SThe calculation is described in Fig.2. The position occurring the turning point correspondes to the best registration distanced, also equals to the reconstructing distance d '.It should be indicated that if we only need to reconstruct the phase map of the object wave, the registration distance substituted into the calculation equation is permitted having a departure from its true value.4 Spatial resolution of digital holography4.1 Affecting factors of the spatial resolution of digital holographyIt should be considered in three respects: (1) sizes of the object and the registering material, and the direction of the reference beam, (2) resolution of the registering material, and (3) diffraction limitation.For pointx2on the object shown in Fig.3, the limits of spatial frequency are λξθλθθ⎥⎦⎤⎢⎣⎡⎪⎪⎭⎫ ⎝⎛-'-=-=-0211maxmax tan sin sin sin sin z x f R R Fig.2 Determining reconstructing distanceλξθλθθ⎥⎦⎤⎢⎣⎡⎪⎪⎭⎫⎝⎛-'-=-=-211minmintansinsinsinsin zxfRRFrequency range isλξξ⎥⎦⎤⎢⎣⎡⎪⎪⎭⎫⎝⎛-'-⎥⎦⎤⎢⎣⎡⎪⎪⎭⎫⎝⎛-=∆--211211tansintansinzxzxfso the range is unrelated to the reference beam.Considering the resolution of registering material in order to satisfy the sampling theory, phase difference between adjacent points on the recording plate should be less than π, namely resolution of the registration material.cfff=∆η21)(minmaxπ4.2 Expanding the spatial resolution of reconstruction imageExpanding the spatial resolution can be realized at least in three ways: (1) Reducing the registration distance z0 can improve the reconstruction resolution, but it goes with reduction of the reconstruction area at the same ratio.Therefore, this method has its limitation. (2) Increasing the resolution and the imaging size of CCD with expensive price. (3) Applying image-synthesizing technique[11]CCD captures a few of images between which there is small displacement (usually a fraction of the pixel size) vertical to the CCD plane, shown in Fig.4(Schematic of vertical moving is the same).This method has two disadvantages. First, it is unsuitable for dynamic testing and can only be applied in the static image reconstruction. Second, because the pixel size is small (usually 5μm to 10μm) and the displacement should a fraction of this size (for example 2μm), it needs a moving table with high resolution and precision. Also it needs high stability in whole testing.In general, improvement of the spatial resolution of digital reconstruction is Fig.3 Relationship between object and CCDstill a big problem for the application of digital holography.5 Testing resultsFig.5 is the photo of the testing system. The paper does testing on two coins. The pixel size of the CCD is 4.65μm and there are 1 392×1 040 pixels. The firstis one Yuan coin of RMB (525 mm) used for image reconstruction by phase-shifting digital holography. The second is one Jiao coin of RMB (520 mm) for the testing of deformation measurement also by phase-shifting digital holography.5.1 Result of image reconstructionThe dimension of the one Yuancoin is 25 mm. The registrationdistance measured by ruler isabout 385mm. We capture ourphase-shifting holograms andreconstruct the image byphase-shifting digital holography.Fig.6 is the reconstructed image.Fig.7 is the curve of the auto-focusFig.4 Image capturing by moving CCD along horizontal directionFig.5 Photo of the testing systemfunction, from which we determine the real registration distance 370 mm. We can also change the controlling precision, for example 5mm, 0.1 mm,etc., to get more course or precision reconstruction position.5.2 Deformation measurementIn digital holography, the method of measuring deformation measurement differs from the traditional holography. It gets object wave before and after deformation and then subtract their phases to obtain the deformation. The study tested effect of heating deformation on the coin of one Jiao. The results are shown in Fig.8, Where (a) is the interferential signal of the object waves before and after deformation, and (b) is the wrapped phase difference.5.3 Improving the spatial resolutionFor the tested coin, we applied four sub-low-resolution holograms to reconstruct the high-resolution by the image-synthesizing technique. Fig.9 (a) is the reconstructed image by one low-resolution hologram, and (b) is the high-resolution image reconstructed from four low-resolution holograms.Fig.6 Reconstructed image Fig.7 Auto-focus functionFig.8 Heating deformation resultsFig.9 Comparing between the low and high resolution reconstructed image6 SummaryDigital holography can obtain phase and amplitude of the object wave at the same time. Compared to other techniques is a big advantage. Phase-shifting digital holography can realize image reconstruction and deformation with less noise. But it is unsuitable for dynamic testing. Applying the intensity sum of the reconstruction image as the auto-focusing function to evaluate the registering distance is easy, and computation is fast. Its precision is also sufficient. The image-synthesizing technique can improve spatial resolution of digital holography, but its static characteristic reduces its practicability. The limited dimension and too big pixel size are still the main obstacles for widely application of digital holography.外文文献译文:标题:图像重建中的相移数字全息摘要:相移数字全息术被用来研究研究艺术品的内部缺陷。

文献翻译模板-本部

英文翻译分院宋体四号字专业宋体四号字届别宋体四号字学号宋体四号字姓名宋体四号字指导教师宋体四号字200X年X月X日<文献翻译一:原文>××××××1××××××××××××××××××××××××××××××××××××××××××××××××××××××××××备注:英文文献翻译原文必须注明出处11.著作:作者姓名.书名[M].xx:出版社,xxxx,xx.2.论文:作者姓名.论文题目[D].杂志名称,xxxx():xx.以英文大写字母方式标识各种参考文献,专著[M]、论文集[C]、报纸文章[N]、期刊文章[J]、学位论文[D]、报告[R]。

宁波大学科学技术学院本科毕业设计(论文)系列表格<文献翻译一:译文>宁波大学本科毕业设计(论文)系列表格<文献翻译二:原文>××××××2××××××××××××××××××××××××××××××××××××××××××××××××××××××××××备注:英文文献翻译原文必须注明出处21.著作:作者姓名.书名[M].xx:出版社,xxxx,xx.2.论文:作者姓名.论文题目[D].杂志名称,xxxx():xx.以英文大写字母方式标识各种参考文献,专著[M]、论文集[C]、报纸文章[N]、期刊文章[J]、学位论文[D]、报告[R]。

大学本科毕业设计文献翻译模板

模型预测油田水中溶解的碳酸钙含量:压力和温度的影响XXX 译摘要:油田中水垢沉积会对储层造成伤害、堵塞地层孔道、表面以及注入设备。

碳酸钙是水中最常见的结垢化合物之一,储层产生的盐水会使压力和温度降低,储层压力降低会使CaCO3的溶解度降低,进而提高体系中碳酸钙的饱和速率,而温度下降会产生相反的结果。

因此温度和压力一起作用的结果可能增加或减小CaCO3溶解度,用体系温度的变化来指定其压力的变化。

因此,在石油生产系统中精确的预测方法的应用备受关注。

目前的研究重点是运用基于最小二乘支持向量机(LSSVM)预测模型来估计油田水中溶解碳酸钙浓度的大小。

用超优化参数(r和C2)的遗传算法(GA)嵌入到LSSVM模型,这种方法可简单准确的预测油田卤水中溶解碳酸钙浓度的最小量。

1.引言随着油田卤水压力和温度变化,气体可能会从储层到地表的运动,导致某些固体沉淀。

为了保持注水井压力平衡并将油运移到生产井,有时需要将卤水注入到储层中,因此,过量的盐垢可以沉积在储层或井眼内。

对于大部分油田结垢多会发生在此过程中。

碳酸钙沉积通常是一个自发的过程,沉积形成的主要原因是二氧化碳从水相逸出,导致油气层的压力下降,该过程会除去了水中的碳酸,直到方解石溶解完全。

在恒定二氧化碳分压下,方解石的溶解性随温度的降低而降低[1-4]。

根据公式(1),碳酸钙沉积垢来自碳酸钙沉淀:Ca2+ + CO32-→ CaCO3↓下面的公式为碳酸的电离式[5–7]:CO2 + H2O → H2CO3H2CO3→ H+ + HCO3-HCO3-→ H+ + CO32-若要形成碳酸氢根离子和氢离子,碳酸要电离,因为碳酸的第一电离常数远大于它的第二电离常数,从碳酸第一电离离子化的氢离子与水中自由的碳酸根离子结合。

此外,碳酸钙沉淀的方程式可以说明[8–10]:Ca(HCO3)2→CaCO3↓+ CO2↑+ H2O碳酸钙的溶解度很大程度上取决于二氧化碳在水中的含量(即二氧化碳气体逸出时所需最小的分压)[10–12]。

外文资料翻译(模板)

毕业设计(论文)外文资料翻译学院:专业:姓名:学号:外文出处:附件: 1.外文资料翻译译文;2.外文原文。

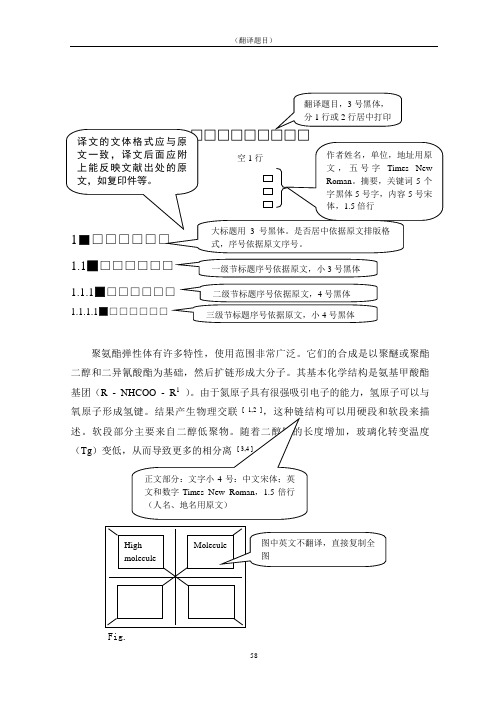

附件1:外文资料翻译译文(空一行)(小4号字,1.25倍行距,居中)××××××(3号黑体,加粗,1.25倍行距,居中)J.R.Cho,S.J. Moon(Times New Roman字体,小4号字,1.25倍行距,居中,作者不译,不要作者工作单位)(空一行)(小4号字,1.25倍行距,居中)摘要(黑体,5号字,1.25倍行距)××××。

(摘要内容为宋体,5号字,1.25倍行距)关键字(黑体,5号字,1.25倍行距)××××××××(各关键词为宋体,5号字,1.25倍行距,段后0.5行,各词间用分号或一个汉字空格隔开)1 前言(各级标题均用黑体,加粗,小4号字,1.25倍行距,顶格)××××××××××××。

(正文均用宋体,小4号字,1.25倍行距)参考文献(见原文)(顶格,黑体,小4号字,1.25倍行距)(参考文献略去,不翻译,与正文间空一行)注意:1文中图表中(包括表头和图题),除符号外均要译成中文,一般为5号字,单倍行间距;表头和图题要处在表格的正上方和正下方,单位要用字母符号表示;要采用三线制表格。

2字母和数字应采用Times New Roman字体。

3物理量和希腊字母要采用斜体。

4最后一页要有“附件2:外文原文(复印件)”字样,且单独占一页。

5页边距按本模板。

附件2:外文原文(复印件)(注意:必须单独占一页)。

文献翻译模板

2016届本科毕业设计(论文)文献翻译题目宋体三号字,加粗学院宋体四号字专业宋体四号字班级宋体四号字学号宋体四号字姓名宋体四号字指导教师宋体四号字开题日期宋体四号字文献一:(宋体五号)英文题目(居中,Times New Roman字体,三号加粗)正文(英文不少于10000印刷符号,Times New Roman字体,五号,首行缩进2.5字符,单倍行距,两边对齐)翻译一:(宋体五号,另起一页)中文题目(居中,黑体,三号加粗)正文(中文不少于2000字,宋体,五号,单倍行距,首行缩进2字符)文献二:(宋体五号,另起一页)英文题目(居中,Times New Roman字体,三号加粗)正文(英文不少于10000印刷符号,Times New Roman字体,五号,首行缩进2.5字符,单倍行距,两边对齐)翻译二:(宋体五号,另起一页)中文题目(居中,黑体,三号加粗)正文(中文不少于2000字,宋体,五号,单倍行距,首行缩进2字符)(请参照下面模板)文献一:Research on Spillover Effect of Foreign Direct Investment1. IntroductionIn recent decades, economists have begun to identify technical progress, or more generally, knowledge creation, as the major determinant of economic growth. Until the 1970s, the analysis of economic growth was typically based on neoclassical models that explain growth with the accumulation of labor, capital, and other production factors with diminishing returns to scale. In these models, the economy converges to steady state equilibrium where the level of per capita income is determined by savings and investment, depreciation, and population growth, but where there is no permanent income growth. Any observed income growth per capita occurs because the economy is still converging towards its steady state, or because it is in transition from one steady state to another.The policies needed to achieve growth and development in the framework of these models is therefore straightforward: increases in savings and investments and reductions in the population growth rate, shift the economy to a higher steady state income level. From the view of developing countries, however, these policies are difficult to implement. Low income and development levels are not only consequences, but also causes of low savings and high population growth rates. The importance of technical progress was also recognized in the neoclassical growth models, but the determinants of the level of technology were not discussed in detail; instead, technology was seen as an exogenous factor. Yet, it was clear that convergence in income percapita levels could not occur unless technologies converged as well.From the 1980s and onwards, growth research has therefore increasingly focused on understanding and ontogenetic technical progress. Modern growth theory is largely built on models with constant or increasing returns to reproducible factors as a result of the accumulation of knowledge. Knowledge is, to some extent, a public good, and R&D, education, training, and other investments in knowledge creation may generate externalities that prevent diminishing returns to scale for labor and physical capital. Taking this into account, the economy may experience positive long-run growth instead of the neoclassical steady state where per capita incomes remain unchanged. Depending on the economic starting point, technical progress and growth can be based on creation of entirely new knowledge, or adaptation and transfer of existing foreign technology.Along with international trade, the most important vehicle for international technology transfer is foreign direct investment (FDI). It is well known that multinational corporations (MNCs) undertake a major part of the world’s private R&D efforts and production, own and control most of the world’s advanced technology. When a MNC sets up a forei gn affiliate, the affiliate receives some amount of the proprietary technology that constitutes the parent’s firm specific advantage and allows it to compete successfully with local firms that have superior knowledge of local markets, consumer preferences, and business practices. This leads to a geographical diffusion of technology, but not necessarily to any formal transfer of technology beyond the boundaries of the MNCs; the establishment of a foreign affiliate is, almost per definition, a decision to internalize the use of core technology.However, MNC technology may still leak to the surrounding economy through external effects or spillovers that raise the level of human capital in the host country and createproductivity increases in local firms. In many cases, the effects operate through forward and backward linkages, as MNCs provide training and technical assistance to their local suppliers, subcontractors, and customers. The labor market is another important channel for spillovers, as almost all MNCs train operatives and managers who may subsequently take employment in local firms or establish entirely new companies.It is therefore not surprising that attitudes towards inward FDI have changed considerably over the last couple of decades, as most countries have liberalized their policies to attract all kinds of foreign investment. Numerous governments have even introduced various forms of investment incentives to encourage foreign MNCs to invest in their jurisdiction. However, productivity and technology spillovers are not automatic consequences of FDI. Instead, FDI and human capital interact in a complex manner, where FDI inflows create a potential for spillovers of knowledge to the local labor force, at the same time as the host country’s level of human capital determines how much FDI it can attract and whether local firms are able to absorb the potential spillover benefits.2. Foreign Direct Investment and SpilloversThe earliest discussions of spillovers in the literature on foreign direct investment date back to the 1960s. The first author who systematically introduced spillovers (or external effects) among the possible consequences of FDI was MacDougall (1960), who analyzed the general welfare effects of foreign investment. The common aim of the studies was to identify the various costs and benefits of FDI.Productivity externalities were discussed together with several other indirect effects that influence the welfare assessment, such as those arising from the impact of FDI on government revenue, tax policies, terms of trade, and the balance of payments. The fact that spillovers included in the discussion was generally motivated by empirical evidence from case studies rather than by comprehensive theoretical arguments.Yet, the early analyses made clear that multinationals may improve locatives efficiency by entering into industries with high entry barriers and reducing monopolistic distortions, and induce higher technical efficiency if the increased competitive pressure or some demonstration effect spurs local firms to more efficient use of existing resources. They also proposed that the presence may lead to increases in the rate of technology transfer and diffusion. More specifically, case studies showed that foreign MNCs may:(1) Contribute to efficiency by breaking supply bottlenecks (but that the effect may become less important as the technology of the host country advances);(2) Introduce new know-how by demonstrating new technologies and training workers who later take employment in local firms;(3) Either break down monopolies and stimulate competition and efficiency or create a more monopolistic industry structure, depending on the strength and responses of the local firms;(4) Transfer techniques for inventory and quality control and standardization to their local suppliers and distribution channels;Although this diverse list gives some clues about the broad range of various spillover effects, it says little about how common or how important they are in general. Similar complaints can be made about the evidence on spillovers gauged from the numerous case studies discussing various aspects of FDI in different countries and industries. These studies often contain valuable circumstantial evidence of spillovers, but often fail to show how significant the spillover effectsare and whether the results can be generalized.For instance, many analyses of the linkages between MNCs and their local suppliers and subcontractors have documented learning and technology transfers that may make up a basis for productivity spillovers or market access spillovers. However, these studies seldom reveal whether the MNCs are able to extract all the benefits that the new technologies or information generate among their supplier firms. Hence, there is no clear proof of spillovers, but it is reasonable to assume that spillovers are positively related to the extent of linkages.Similarly, there are many works on the relation between MNCs entry and presence and market structure in host countries, and this is closely related to the possible effects of FDI on competition in the local markets. There are also case studies of demonstration effects, technology diffusion, and labor training in foreign MNCs. However, although these studies provide much detailed information about the various channels for spillovers, they say little about the overall significance of such spillovers.The statistical studies of spillovers, by contrast, may reveal the overall impact of foreign presence on the productivity of local firms, but they are generally not able to say much about how the effects come about. These studies typically estimate production functions for locally owned firms, and include the foreign share of the industry as one of the explanatory variables. They then test whether foreign presence has a significant positive impact on local productivity once other firm and industry characteristics have been accounted.Research conclude that domestic firms exhibited higher productivity in sectors with a larger foreign share, but argue that it may be wrong to conclude that spillovers have taken place if MNC affiliates systematically locate in the more productive sectors. In addition, they are also able to perform some more detailed tests of regional differences in spillovers. Examining the geographical dispersion of foreign investment, they suggest that the positive impact of FDI accrue mainly to the domestic firms located close to the MNC affiliates. However, effects seem to vary between industries.The results on the presence of spillovers seem to be mixed; recent studies suggest that there should be a systematic pattern where various host industry and host country characteristics influence the incidence of spillovers. For instance, the foreign affiliate’s levels of tech nology or technology imports seem to influence the amount of spillovers to local firms. The technology imports of MNC affiliates, in turn, have been shown to vary systematically with host country characteristics. These imports seem larger in countries and industries where the educational level of the local labor force is higher, where local competition is tougher, and where the host country imposes fewer formal requirements on the affiliates’ operations.Some recent studies have also addressed the apparent contradictions between the earlier statistical spillover studies, with the hypothesis that the host country’s level of technical development or human capital may matter as a starting point.In fact, in some cases, large foreign presence may even be a sign of a weak local industry, where local firms have not been able to absorb any productivity spillovers at all and have therefore been forced to yield market shares to the foreign MNCs.3. FDI Spillover and Human Capital DevelopmentThe transfer of technology from MNC parents to its affiliates and other host country firms is not only mbodied in machinery, equipment, patent rights, and expatriate managers and technicians,but is also realized rough the training of local employees. This training affects most levels of employees, from simple manufacturing operatives through supervisors to technically advanced professionals and top-level managers. While most recipients of training are employed in the MNCs own affiliates, the beneficiaries also include employees among the MNCs suppliers, subcontractors, and customers.Types of training ranged from on-the-job training to seminars and more formal schooling to overseas education, perhaps at the parent company, depending on the skills needed. The various skills gained through the elation with the foreign MNCs may spill over directly when the MNCs do not charge the full value of the training provided to local firms or over time, as the employees move to other firms or set up their own businesses.While the role of MNCs in primary and secondary education is marginal, there is increasingly clear evidence hat FDI may have a noticeable impact on tertiary education in their host countries. The most important effect is perhaps on the demand side. MNCs provide attractive employment opportunities to highly skilled graduates in natural sciences, engineering, and business sciences, which may be an incentive for gifted students to complete tertiary training, and MNCs demand skilled labor, which may encourage governments to invest in higher education.Many studies undertaken in developing countries have emphasized the spillovers of management skills. There is evidence of training and capacity development in technical areas, although the number of detailed studies appears smaller.While training activities in manufacturing often aim to facilitate the introduction of new technologies that are embodied in machinery and equipments, the training in service sectors is more directly focused on strengthening skills and know-how embodied in employees. This means that training and human capital development are often more important in service industries. Furthermore, many services are not tradable across international borders, which mean that service MNCs to a great extent are forced to reproduce home country technologies in their foreign affiliates. As a consequence, service companies are often forced to invest more in training, and the gap between affiliate and parent company wages tends, therefore, to be smaller than that in manufacturing.4. ConclusionThis paper has noted that the interaction of FDI and spillovers is complex and highly non-linear, and that several different outcomes are possible. FDI inflows create a potential for spillovers of knowledge to the local labor force, at the same time as the host country’s level of human capital determines how much FDI it can attract and whether local firms are able to absorb the potential spillover benefits. Hence, it is possible that host economies with relatively high levels of human capital may be able to attract large amounts of technology intensive foreign MNCs that contribute significantly to the further development of labor skills. At the same time, economies with weaker initial conditions are likely to experience smaller inflows of FDI, and those foreign firms that enter are likely to use simpler technologies that contribute only marginally to local learning and skill development.翻译一:外商直接投资溢出效应研究1.引言在最近几十年中,经济学家们已开始确定技术进步,或更普遍认为知识创造,作为经济增长原动力的一个重要决定因素,直到20世纪70年代,分析经济增长运用典型的新古典主义模型来解释经济增长的积累,劳动力、资本等生产要素与收益递减的规模。

4文献翻译模板

(2-7)

(如果有的话)

表6-1■2000—2010年世界聚氨酯产量

CASE

3484940

4792195

5877100