Foundations of Cognitive Grammar.

认知语言学主要内容

一、认知语言学的起源二、主要内容19 世纪末20 世纪初,当心理学从哲学中分离出来成为一门独立的实验学科之时,语言的认知研究便已开始。

1987年是认知语言学正式的诞生年,虽然此前已有一些零星的文章预示着一种新的语言学理论即将诞生。

但是一般认为,这一年出版的Lakoff“Women, Fire ,and Dangerous Things”和Langacker“Foundations of Cognitive Grammar”标志着认知语言学作为一种独立语言学理论的诞生。

认知语言学研究的主要代表人物是Langacker,Lakoff,Jackendoff, Taylor 和Talmy等人。

认知语言学包括认知音系学、认知语义学、认知语用学等分支,研究内容广,覆盖面大,概括起来主要有以下几点:一、范畴化与典型理论语言学在方法论和本质上都与范畴化(categorization)紧密相关。

范畴化能力是人类最重要的认知能力之一,是“判断一个特定的事物是或不是某一具体范畴的事例”(Jackendoff , 1983∶77) 。

Labov和Rosch对范畴的研究,打破了范畴的“经典理论”或称“亚里士多德理论”一统天下的局面。

“经典理论”认为:范畴是由必要和充分特征联合定义的;特征是二分的;范畴有明确的边界;范畴内的所有成员地位相等。

这一理论却受到了认知科学的有力挑战。

Rosch 还提出了“典型理论”(prototype theory) ,认为大多数自然范畴不可能制定出必要和充分的标准,可以公认为必要的标准往往不是充分的;一个范畴的成员之间的地位并不相同,典型成员具有特殊的地位,被视为该范畴的正式成员,非典型成员则根据其与典型成员的相似程度被赋予不同程度的非正式成员地位。

例如,在“鸟”范畴内“知更,鸟”常被视为典型成员,而“企鹅”、“驼鸟”等则为非典型成员。

当然,一个范畴的典型成员会因不同的人、文化、地理位置而有所不同,但一个范畴中总有典型的。

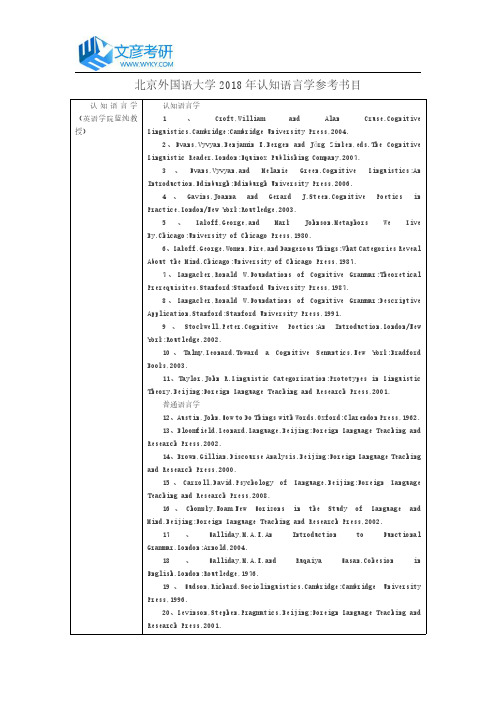

北京外国语大学2018年认知语言学参考书目

北京外国语大学2018年认知语言学参考书目认知语言学(英语学院蓝纯教授)认知语言学1、Croft,William and Alan Cruse.Cognitive Linguistics.Cambridge:Cambridge University Press,2004.2、Evans,Vyvyan,Benjamin K.Bergen and Jörg Zinken,eds.The Cognitive Linguistic Reader.London:Equinox Publishing Company,2007.3、Evans,Vyvyan,and Melanie Green.Cognitive Linguistics:An Introduction.Edinburgh:Edinburgh University Press,2006.4、Gavins,Joanna and Gerard J.Steen.Cognitive Poetics in Practice.London/New York:Routledge,2003.5、Lakoff,George,and Mark Johnson.Metaphors We Live By.Chicago:University of Chicago Press,1980.6、Lakoff,George.Women,Fire,and Dangerous Things:What Categories Reveal About the Mind.Chicago:University of Chicago Press,1987.7、Langacker,Ronald W.Foundations of Cognitive Grammar:Theoretical Prerequisites.Stanford:Stanford University Press,1987.8、Langacker,Ronald W.Foundations of Cognitive Grammar:Descriptive Application.Stanford:Stanford University Press,1991.9、Stockwell,Peter.Cognitive Poetics:An Introduction.London/New York:Routledge,2002.10、Talmy,Leonard.Toward a Cognitive Semantics.New York:Bradford Books,2003.11、Taylor,John R.Linguistic Categorization:Prototypes in Linguistic Theory.Beijing:Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press,2001.普通语言学12、Austin,John.How to Do Things with Words.Oxford:Clarendon Press,1962.13、Bloomfield,nguage.Beijing:Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press,2002.14、Brown,Gillian.Discourse Analysis.Beijing:Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press,2000.15、Carroll,David.Psychology of Language.Beijing:Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press,2008.16、Chomsky,Noam.New Horizons in the Study of Language and Mind.Beijing:Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press,2002.17、Halliday,M.A.K.An Introduction to Functional Grammar.London:Arnold,2004.18、Halliday,M.A.K.and Ruqaiya Hasan.Cohesion in English.London:Routledge,1976.19、Hudson,Richard.Sociolinguistics.Cambridge:Cambridge University Press,1996.20、Levinson,Stephen.Pragmatics.Beijing:Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press,2001.21、Lyons,John.Linguistic Semantics:AnIntroduction.Cambridge:Cambridge University Press,1995.22、Ouhuala,Jamal.Introducing Transformational Grammar:From Principlesand Parameters to Minimalism.Beijing:Foreign Language Teaching and ResearchPress,2001.23、Robins,Rodman.A Short History of Linguistics.London:Routledge,2015.24、Sapir,nguage:An Introduction to the Study of Speech.NewYork:Harcourt,Brace and Company,1921.25、Saussure,Ferdinand de.Course in General Linguistics.Eds.CharlesBally and Albert Sechehaye.Trans.Roy Salle,Illinois:OpenCourt,1983.26、Searle,John.Expression and Meaning:Studies in the Theory of SpeechActs.Cambridge:Cambridge University Press,1979.27、Sperber,Dan and Deirdre Wilson.Relevance:Communication andCognition.New York:Blackwell Publishers Ltd.,1995.28、Ungerer,F.and H.J.Schmid.An Introduction to CognitiveLinguistics.Beijing:Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press,2008.文章来源:文彦考研。

英语语言文学专业(学科代码:050201)

英语语言文学英语语言理论与应用方向必读书目:(1) Brown, G. & Y ule, G. 1983. Discourse Analysis. CUP.(话语分析,外研社¥27.90)代订购(2) Chomsky, N. 1957. Syntactic Structures. Mouton, The Hague.,胶印本¥5.00(3) Ellis, R. 1994. The Study of Second Language Acquisition. Oxford: Oxford University Press(第二语言习得研究,上外,¥49.00),胶印本¥35.00/套,2册.(4) Haiman, John. 1985. Natural Syntax. CUP ,胶印本10.00(5) Halliday, M.A.K. An Introduction to Functional Grammar[M]. London: Edward Arnold Ltd.,1994. Reprinted by (外语教学与研究出版社,2000,¥41.91),胶印本¥30.00(6) Hurford James R & Heasley Brendan. 1983. Semantics: A Course book. Cambridge: CUP.复印本¥16.00(7) Lakoff, G. & M. Johnson. 1999. Philosophy in the Flesh --- The Embodied Mind胶印本¥15.0(8) Levinson. S. 1983. Pragmatics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press(语用学,外研社¥38.90),代订购. (9) Jennifer,Hornsby &…,2006,Reading Philosophy of Language,Blackwell Publishing.胶印本¥20.00(10)Radford A. 1988/2000. Transformational Grammar: A First Course, Foreign LanguageTeaching and Research Press/Cambridge University Press.(转换生成语法,外研社,¥56.90)胶印本¥30.00参考书目:(1)Bal, M., 1985. Narratology. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.(2)Bell, J. (1999/2004) Doing Your Research Project: A Guide for First-time researchers in Education and Social Science. Open University Press/外教社.(3)Carter, R. & Simpson, P. (eds.), 1989. Language, Discourse and Literature : An Introductory Reader in Discourse Stylistics. London: Unwin Uyman.(4)Chomsky, N. 1965. Aspects of the Theory of Syntax. MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass.(5)Chomsky, N. 1975. The Logical Structure of Linguistic Theory. Plenum, New Y ork.(6)Chomsky, N. 1981. Lectures on Government and Binding. Foris, Dordrecht.(7)Chomsky, N. 1986. Knowledge of Language: Its Nature, Origin and Use, Praeger, New Y ork. (8)Cobley, P., 2001. Narrative. London and New Y ork: Routledge.(9)Cook, G. 1989. Discourse. OUP. ★(10)Cook, V. 1993. Linguistics and Second Language Acquisition.London: The Macmillan Press Ltd.(11)Coulmas, F. (ed.). The Handbook of Sociolinguistics. Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press, 2001.(12)Fauconnier, Gile & Mark Turner. 2002. The Way We Think --- Conceptual Blending and the Mind’s Hidden Complexities.New Y ork: Basic Books..(13)Fillmore, Charles. 1982. Frames Semantics. In Linguistic Society of Korea (ed.).Linguistics in the Morning Calm.Seoul: Hanshin. 111—138.(14)Garman, M. Psycholinguistics. Beijing University Press(4th.), 2002.(15)Halliday, M. A. K. & R. Hasan. Cohesion in English[M]. London: Longman, 1976.Reprinted by 外语教学与研究出版社(2001).(16)Halliday, M. A. K. and Christian M. I. M. Matthiessen. Construing Experience ThroughMeaning: A Language-based Approach to Cognition. London/New Y ork: Continuum,1999.(17)Halliday, M.A.K. Language as Social Semiotic: the Social Interpretation of Language and Meaning. London: Edward Arnold, 1978. Reprinted by 外语教学与研究出版社(2001). (18)Herman,David (ed.), 2003. Narrative Theory and the Cognitive Sciences. Stanford University: Publications of the Center for the Study of Language and Information. (19)Jackendoff, R. S. 1983. Semantics and Cognition.Cambridge, MA.:MIT Press. (20)Jorgensen, M. & Philips, L. 2002. Discourse Analysis as Theory and Method.Sage Publications.(21)Kennedy, G. 1998. An Introduction to Corpus Linguistics. London: Longman.(22)Langacker, R, W. 1987,1991. Foundations of Cognitive Grammar vol. I: Theoretical Prerequisites;vol. II: Descriptive Application.Stanford,California:Stanford University Press.(23)Larsen-Freeman, D & Long, M. 1991. An Introduction to Second Language Acquisition Research. (Chinese Edition) Beijing: Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press. (24)Leech, G. & Short, M., 1982. Style in Fiction: A Linguistic Introduction to English Fictional Prose. Longman Group.(25)Nunan, D. (1992/2002) Research Methods in Language Learning .CUP/外教社.(26)Ooi, Bincent B. Y. 1998. Computer Corpus Lexicography. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.(27)Ortony, Andrew(ed.). 1979. Metaphor and Thought, CPU.(28)Prince, Gerald, 1982. Narratology: The Form and Functioning of Narrative. Berlin• NewYork • Amsterdam: Mouton Publishers.(29)Radford A. 1997/2000. Syntax:A Minimalist Introduction. Foreign Language Teaching and Rimmon-Kenan, S., 1983, 2002. Narrative Fiction. Routledge.(30)Searle, J. 1969/2001. Speech Acts: An Essay in the Philosophy of Language[M]. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 北京:外语教学与研究出版社(31)Sperber, D. & D. Wilson. 1986/2001. Relevance: Communication and Cognition[M].Oxford: Basil Blackwell; 北京: 外语教学与研究出版社& Blackwell Publishers Ltd. (32)Stubbs, Michael. 2001. Words and Phrases: Corpus Studies of Lexical Semantics. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers.(33)Svensén, Bo. 1993. Practical Lexicography: Principles and Methods of Dictionary-Making.John Sykes and Kerstin Schofield. Oxford: Oxford Universitiy Press.(34)Sweetser, Eve E. 1990.From Etymology to Pragmatics --- Metaphorical and Cultural Aspects of Semantic Structure. CUP.(35)Taylor, John. 2002. Cognitive Grammar.OUP.(36)Taylor,John. 1989. Linguistic Categorization --- Prototypes in Linguistic Theory. OUP.(1995年第二版,2003年第三版)(37)Traugott, E. C. & B. Heine. 1991. Approaches to Grammaticalization.Amsterdam:John Benjamins.(38)V erschueren. J. 2000. Understanding Pragmatics[M]. Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press and Edward Arnold (Publishers) Ltd.(39)申丹,1998.《叙述学与小说文体学研究》.北京大学出版社.,¥20.00(40)严辰松. (2000) 定量型社会科学研究方法. 西安交大出版社.翻译理论与实践方向必读书目:1、Bassnett, Susan and Andre Lefevere, ed. 1990. Translation, History and Culture. London:Cassell.上外,¥12.00(祝朝伟)/ 胶印本7.00 2、Gentzler, Edwin. 2001.Contemporary Translation Theories.Second Revised Edition.Multilingual Matters.上外,¥14.00(廖七一)/ 代订购3、Harish Trivedi, ed. 1996. Post-colonial Translation: Theory and Practice. London and NewYork: Routledge.(费小平)/ 胶印本¥10.00 4、Hermans, Theo. 1999.Translation in Systems: Descriptive and Systemic ApproachExplained. St. Jerome Publishing.,上外,¥12.00(廖七一)/ 胶印本,¥6.00 5、Hickey, Leo, ed. 1998. The Pragmatics of Translation. Multilingual Matters Ltd.(侯国金)上外,¥14.50 / 胶印本,¥10.00 6、Jones, Roderick. 1998. Conference Interpreting Explained. Manchester: St. JeromePublishing.(李芳琴)/ 胶印本,¥10.00 7、Lefevere, Andre. Translation, Rewriting and the Manipulation of Literary Fame. Shanghai:Shanghai Foreign Language Education Press, 2004.¥11.00(祝朝伟)/ 胶印本,¥8.00 8、Simon,Sherry.1996. Gender in Translation. London and New York: Routledge.(费小平)/复印本,¥6.009、陈福康,《中国译学理论史稿》,上海外语教育出版社,2002,¥23.00(杨全红)/代订购10、谢天振:《译介学》,上海:上海外语教育出版社,1999年¥18.00(杨全红)/代订购推荐书目:Alvarez, Roman and M. Carmen-Africa Vidal, ed. 1996. Translation, Power, Subversion.Multilingual Matters Ltd.Baker, Mona, ed. 1998. Routledge Encyclopedia of Translation Studies. London and New York: Routledge.Bassnett-Mcguire Susan. 1980. Translation Studies. London and New York: Routledge. Bassnett, Susan and Andre Lefevere. 1998.Constructing Cultur e: Essays on Literary Translation. Multilingual Matters Ltd.Bassnett, Susan and Harish Trivedi, eds. 1999. Post-colonial Translation Theory and Practice.London and New York: Routledge.Bell, Roger. 1991. Translation and Translating: Theory and Practice. London and New York: Longman.Catford, J.C. 1965. A Linguistic Theory of Translation.London: Oxford University Press.胶印本,¥5.00Chesterman, Andrew. 1997. Memes of Translation: The Spr ead of Ideas in Translation Theory.Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company.Davis, Kathleen. 2001. Deconstruction and Translation. Manchester and Northampton: St.Jerome Publishing.Flotow, Luise von. 1997.Translation and Gender: Translating in the Era of Feminism. St.Jerome Publishing.Gutt, Ernst-August. 1991. Translation and Relevance, Cognition and Context. Oxford, Basil Blackwell Ltd.Hatim, Basil. 2001. Teaching and Researching Translation. Pearson Education Limited. Hermans, Theo. 1985. The Manipulation of Literature. Croom Helm Ltd.Munday, Jeremy. 2001. Introducing Translation Studies: Theories and Applications. London and New York: Routledge.Newmark, Peter. 1981. Appr oaches to Translation. Oxford: Pergamon Press.Nida, E.A. 1964. Toward a Science of Translating. Leiden: E.J. Brill.Nida, E.A. 2001. Language and Culture: Contexts in Translation.Shanghai Foreign Language Education Press.Reiss, Katharina. 2000. Translation Criticism—the Potentials and Limitations: Catergories and Criteria for Translation Quality Assessment. Trans. Erroll F. Rhodes. St. Jerome Publishing.Robinson, Douglas. 1997/2002. Western Translation Theory: From Herodotus to Nietzsche. St.Jerome.Savory, Theodore H. 1957. The Art of Translation. London: Cape.Schaffner, Christian and Helen Kell-Holmes. 1995. Cultural Functions of Translation.Multilingual Matters, Ltd.Shuttleworth, Mark and Moira Cowie. 1997. Dictionary of Translation Studies.St. Jerome PublishingSnell-Hornby, Mary et al. 1994. Translation Studies: An Inter discipline.Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company.Steiner, G. 1975. After Babel: Aspects of Language and Translation.London: Oxford University Press.Toury, Gideon. 1995.Descriptive Translation Studies and Beyond. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company.Tymoczko, Maria. 1999. Translation in a Postcolonial Context. St. Jerome Publishing.V enuti, Lawrence. 1995. The Translator's Invisibility: A History of Translation. London and New York: Routledge.Williams, Jenny and Andrew Chesterman. 2002. The Map. St. Jerome Publishing.Ztaleva, Palma ed. 1993. Translation as Social Action. London: Routledge.郭延礼:《中国近代翻译文学概论》,武汉:湖北教育出版社,1998年。

语文学科前沿(2)

六、转换生成语法乔姆斯基(Noam Chomsky, 1928--),美国语言学家,转换生成语法的创始人。

乔姆斯基把语言研究和数学,现代数理逻辑结合起来,提出了新的语言理论,即转换生成语法,形成了一个语言学的新派别。

1957年乔姆斯基出版《句法结构》,开创生成语法理论,标志着语言学研究史上一次极为重要的范式上的转移,这一转移推动了众多相关学科的发展及新研究领域的开拓。

乔姆斯基的研究大致可分为四个阶段:1965,《句法理论要略》(标准理论);1972,《生成语法中的语义研究》(扩充式标准理论);1981,《管辖与约束讲稿》(管约论GB Theory);1992,《语言学理论的最简方案》(最简方案)。

乔姆斯基的语言研究方法不再以归纳法为主,而改为以演绎-推导法为主。

他认为语言是人的生物属性,人的语法知识是天赋的,人类语言存在着普遍语法,人脑中有专司语言的机制--语言官能。

乔姆斯基以内省、演绎、形式化的方法探寻人类语言的普遍运作机制和特点。

乔姆斯基把语言分为三个部分,即句法部分,语义部分和语音部分。

句法部分构成一个句子的深层结构,并进一步转换成它的表层结构。

语义部分对这个句子的深层结构进行语义结构说明。

而语音部分对表层结构做出语音说明。

乔姆斯基在一系列逐步严格限制的基础上,设计了四套文法(文法不等于语法):0型文法:不加上述任何限制1型文法:上下文有关文法2型文法:上下文无关文法3型文法:有限状态文法四类文法之间的关系是层层包含的,如每一个有限状态文法都是上下文无关文法,每一个上下文无关文法都是上下文有关文法,O型文法范围最大。

反之则不然。

大致为:0型文法>上下文有关文法>上下文无关文法>有限状态文法。

有限状态文法源自马尔可夫过程,不仅生成能力差,而且不能说明语言层次。

上下文无关文法,类似树形结构图。

从根(标号S)到叶,叶表示最后的实际单位,根是要分析的结构。

上下文有关文法与0形文法生成能力逐级递增,但因为上下文无关文法可以采取乔姆斯基范式实现层次分析,故在自然语言研究中为人们乐于采用。

认知语言学

学科发展历程

认知语言学在20世纪70年代中期开始在美国孕育(朗 奴·兰盖克提出空间语法),80年代中期以后开始成熟, 其学派地位得以确立,其确立标志为1989年春由勒内·德 尔文(ReneDirven) 组织的在德国杜伊斯堡(Duisbury) 召 开的第一届国际认知语言学大会。此次大会宣布于1990年 发行《认知语言学》杂志, 成立国际认知语言学( ICLA) , 出版认知语言学研究的系列专著,90年代中期以后开始进 入稳步个特例。一个范 畴或类别往往有个“原型”,是用以确定类别的参照标准, 需要归类的目标与标准进行比较,符合标准所有特征的目 标例示(instantiate)这一标准,不完全符合的目标是 对标准的扩展(extension)。

经典范畴理论的如下特征 1 范畴划分由一组充分必 要条件决定 2 特征是二元 3 范畴具有清晰边界 4 范畴 成员之间地位平等。

eg2.钟书能 阮薇. 认知与忠实——汉英上下位词翻译的认知 视角『j』.韶关学院学报

3.上下位:

以基本层次范畴为中心 范畴可以向上发展为上位范畴向 下发展为下位范畴上位范畴依赖于基本层次范畴 且物体 的完形形象和大部分属性都来自基本层次范畴 因此又被 称为寄生范畴(parasiticcategory) 下位范畴也是寄生范 畴它是在基本层次范畴的基础上更进一步细致的切分。

二、认知语言学的主要概念

原型 范畴化、基本范畴、上下位 命题模式、意象模式、隐喻模式、转喻模式 意象图示

1.原型(prototype):

是物体范畴最好、最 典型的成员, 所有其他成 员也均具有不同程度的典 型性。

eg1. 在英语的世界图景中, 鸟的原型为画眉鸟;而对于 母语为俄语的人而言则是 麻雀; 麻雀在中国人的认 知意义中也具有典型意义。

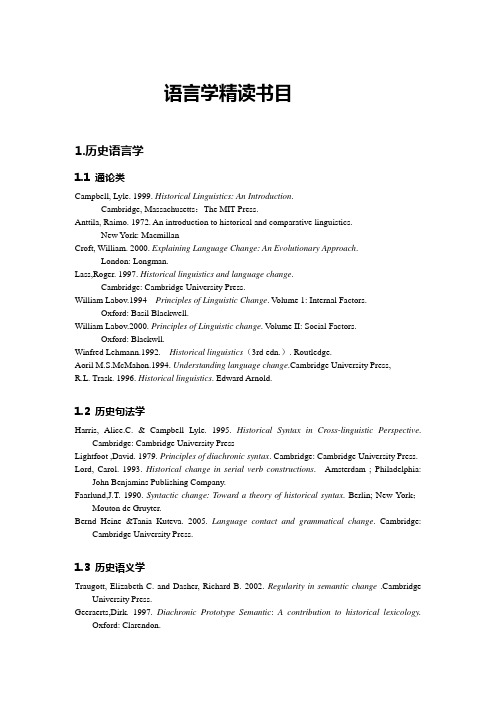

语言学精读书目(英文)

语言学精读书目1.历史语言学1.1 通论类Campbell, Lyle. 1999. Historical Linguistics: An Introduction.Cambridge, Massachusetts:The MIT Press.Anttila, Raimo. 1972. An introduction to historical and comparative linguistics.New York: MacmillanCroft, William. 2000. Explaining Language Change: An Evolutionary Approach.London: Longman.Lass,Roger. 1997. Historical linguistics and language change.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.William Labov.1994 Principles of Linguistic Change. V olume 1: Internal Factors.Oxford: Basil Blackwell.William Labov.2000. Principles of Linguistic change. V olume II: Social Factors.Oxford: Blackwll.Winfred Lehmann.1992. Historical linguistics(3rd edn.). Routledge.Aoril M.S.McMahon.1994. Understanding language change.Cambridge University Press,R.L. Trask. 1996. Historical linguistics. Edward Arnold.1.2 历史句法学Harris, Alice.C. & Campbell Lyle. 1995. Historical Syntax in Cross-linguistic Perspective.Cambridge: Cambridge University PressLightfoot ,David. 1979. Principles of diachronic syntax. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Lord, Carol. 1993. Historical change in serial verb constructions. Amsterdam ; Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company.Faarlund,J.T. 1990. Syntactic change: Toward a theory of historical syntax. Berlin; New York;Mouton de Gruyter.Bernd Heine &Tania Kuteva. 2005. Language contact and grammatical change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.1.3 历史语义学Traugott, Elizabeth C. and Dasher, Richard B. 2002. Regularity in semantic change .Cambridge University Press.Geeraerts,Dirk. 1997. Diachronic Prototype Semantic:A contribution to historical lexicology.Oxford: Clarendon.Sweetser, Eve E.1990. From etymology to pragmatics: Metaphorical and cultural aspects of semantic structure. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 19901.4 历史语用学Arnovick,Lesliek. 1999. Diachronic Pragmatics. John Benjamins Publishing Company. Brinton, Laurel J. 1996. Pragmatic markers in English: Grammaticalization and discourse function. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.2.语法化研究Givo n, Talmy. 1979. On Understanding Grammar. New York: Academic Press.Heine, Bernd & Kuteva ,Tania. 2002 .World lexicon of grammaticalization.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Heine , Bernd, Ulrike Claudi & Friederike Hu nnemeyer. 1991. Grammaticalization : Aconceptual Framework. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.Bybee, Joan. , Revere Perkins, and William Pagliuca. 1994. The evolution of grammar: Tense, aspect and modality in the languages of the world. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Hopper, Paul J .&Traugott, Elizabeth C. 2003. Grammaticalization, 2nd edition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Lehmann, Christian. 1995[1982]. Thoughts on Grammaticalization. Munich: Lincom Europa.Xiu-Zhi Zoe WU.2004. Grammaticalization and Language Change in Chinese : A formal view London and New York: RoutledgeCurzonElly van Gelderen. 2004.Grammaticalization as Economy. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing CompanyBernd Heine and Tania Kuteva. 2005 Language Contact and Grammatical Change. Cambridge University Press.Ian Roberts and Anna Roussou.2003. SyntacticChange: A minimalist approach to grammaticaliza- tion. Canbridge:Cambridge University Press.Regine Eckardt. 2006. Meaning change in grammaticalization: an enquiry into semantic reanalysis New York : Oxford University Press.3.认知语言学Taylor, John R. 2005. Cognitive grammar.Oxford: Oxford University Press.Croft,William and D. A. Cruse.2004. Cognitive linguistics. (Cambridge Textbooks in Linguistics.) Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Langacker,Ronald W. 1987/1991. Foundations of cognitive grammar,vol.1-2, Stanford: Stanford University Press.Lakoff, George.1987. Women, fire, and dangerous things: What categories reveal about the mind. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.Talmy, L. 2000, Toward a Cognitive Semantics. V ol.1& 2. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.4.语言类型学Croft, William. 2003. Typology and Universals, 2nd edition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Song, Jae Jung. 2001. Linguistic Typology: Morphology and syntax. Longman.Whaley, Linndsay J. 1997. Introduction to Typology: the unity and diversity of language. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.L.J.Whaley. 1997. Introduction to typology: The unity and diversity of language. Sage. Bernard Comrie. 1989. Languge universals and linguistic typology(2nd edition), University of Chicago Press.J.A.Hawkins. 1983. Word order universals. Academic Press.5.语用学、句法学与语义学5.1 句法学:Payne,Thomas E. 1997. Describing Morphosyntax. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Thomas E. Payne.2006. Exploring language Structure: A student’s guide. Cambridge University Press.Timothy Shopen. 1985. Language typology and syntactic Description. Cambridge University Press.Givo n, Talmy. 1984/1991. Syntax: A functional-typological introduction, V ol.I.II, Amsterdam: Benjamins,1984.5.2 语义学:Lyons, John. 1977. Semantics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Saeed,John. 1997. Sementics. Blackwell Publishers.5.3 语用学:Levinson,Stephen C. 1983. Pragmatics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Green,Georgia M. 1989. Pragmatics and natural language understanding .Hillsdale,NJ:Erlbaum Associates.5.4 其他:Schiffrin, Deborah. 1987. Discourse markers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Karin Aijmer. 2002. English Discourse Particles: Evidence from a corpus. Amsterdam/ Philadelphia : John Benjamins Publishing Company.Verhagen, Arie. 2005. Constructions of intersubjectivity: Discourse, syntax,and cognition. Oxford:Oxford University Press.Dahl, Osten. 1985.Tense and aspect systems. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.Kemmer,Suzanne. 1993. The middle voice: A typological and diachronic study.Amsterdam: Benjamins.Bybee, Joan. 1985. Morphology: A study of the relation between meaning and form. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.Newmeyer, Fredrick J. Language form and language function. Cambridge;MA: MIT Press,1998 Croft,William. Syntactic categories and grammatical relations.Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1991Haiman, John. Natural syntax: Iconicity and erosion. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985.Comrie, Bernard. 1976. Aspect: An introduction to the study of verbal aspect and related problems. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Comrie ,Bernard. 1985.Tense. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Palmer,F.R.2001. Mood and Modality. Second Edition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Smith,Carlotta S.1991. The Parameter of Aspect. Dordrecht: Kluwer.Goldberg, A. E. 1995,Constructions: A Construction Grammar Approach to Argument Structure.Chicago: Chicago University Press.6.接触语言学:Thomason, Sarah G. 2001. Language contact: An introduction. Edinburgh University Press. Thomason, Sarah G. & Kaufman,Terrence.1988. Language contact, creolization, and genetic linguistics. Berkeley: University of California Press.Dixon, R.M.W. 1997. The rise and fall of languages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Holm, J. 2004. Languages in contact. The partial restructuring of vernaculars. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Myers-Scotton, C. 2003. Contact linguistics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.Winford,Donald. 2003. An introduction to contact linguistics. Oxford: Blackwell.Aikhenvald, Alexandra Y. 2002. Language contact in Amazonia. New York: Oxford University Press.Enfield, N. J. 2003. Linguistic epidemiology: semantics and grammar of language contact in mainland Southeast Asia. London: Routledge Curzon.。

名词化现象论文:英语名词化现象的认知诠释

名词化现象论文:英语名词化现象的认知诠释【摘要】名词化是从其它词类或底层小句派生名词或名词短语的过程。

本文在前人对其形式、种类及功能研究的基础上,从认知的角度出发,运用范畴观、认知域、诠释学、凸显观四个相关理论对名词化现象进行了解释,阐释了英文中大量存在名词化的原因,同时也给读者理解复杂的名词化结构提供了帮助。

【关键词】名词化现象范畴观认知域诠释学凸显观1 引言对名词化的研究最早可以追溯到古希腊时期的柏拉图和亚里士多德,虽然他们没有明确提出名词化概念,但他们将词类分为了两大部分:名词性成分和动词性成分,并对它们之间的转换进行了讨论(刘国辉,2000:5)。

结构主义语言学家叶斯柏森(jespersen,1937)在《分析句法》中将名词化称为“主谓实体词”,并把主谓实体词分为“动词性”,如“arrival”,和“谓词性”,如“cleverness”,这就相当于我们通常所说的动词的名词化和形容词的名词化。

系统功能语法学家韩里德(halliday,1994)认为名词化是一种语法隐喻工具,“是用名词来体现本来要用动词或形容词体现的‘过程’或‘特征’”。

国内对名词化的研究主要集中于对其形式(徐玉臣,2009)、种类(刘露营,2009)和功能(张书慧,2009)的描述。

自20世纪90年代初认知语言学成型并引起国内语言学界广泛关注后,从认知角度对名词化现象进行研究的学者越来越多,如:张权从认知的角度系统地解释了英语动词在名词化过程中其动作的时体意义和主客体意义的转化,以及动名词与动词派生名词这两种形式之间的认知差别(张权,2001)。

谢金荣运用认知的相关概念(如:认知是信息加工;认知是思维;认知是知觉、记忆、判断、推理等一组相关活动)将名词化看成是多个命题的组合或范畴的集合,从而对之进行认知解释。

她还从认知的角度对名词化词组的构成方式进行了解释,认为名词化词组是按经验结构排序(谢金荣,2006)。

认知语言学的核心思想是语言与现实之间存在认知。

英语硕士论文参考文献[Word文档]

![英语硕士论文参考文献[Word文档]](https://img.taocdn.com/s3/m/64ceb421ef06eff9aef8941ea76e58fafab0454f.png)

英语硕士论文参考文献本文档格式为WORD,感谢你的阅读。

最新最全的学术论文期刊文献年终总结年终报告工作总结个人总结述职报告实习报告单位总结演讲稿英语硕士论文参考文献可以反映论文作者的科学态度和论文具有真实、广泛的科学依据,下面是英语参考文献文献。

参考文献一:[1]Baker,C.,C.FillmoreJ.Lowe.1998.TheBerkeleyFrameNetProject[A].InC.Boitet P.Whitelock(eds.).Proceedingsofthe36thAnnualMeetingoft heAssociationforComputationalLinguisticsand17thInterna tionalConferenceonComputationalLinguistics[C].SanFranc isco:MorganKaufmann.86-90.[2]Berlin,Brent,PaulKay.BasicColorTerm.TheirUniversity andEvolution[M].Berkeley,LosAngeles:UniversityofCalifo rniaPress,1969:169-83.[3]Boas,H.C.FrameSemanticsasaframeworkfordescribingpol ysemyandsyntacticstructuresofEnglishandGermanmotionver bsinContrastiveComputationalLexicography[A].InRaysonPa ul,AndrewWilson,TonyMcenery,AndrewHardie,andShereenKho ja(eds.)ProceedingsoftheCorpusLinguistics2001Conferenc e[C]:LancasterUniversityCenterforComputerCor pusResearchonLanguage,2001.[4]Breal,M.EssaideSemantique,SciencedesSignifications( 5th.ed)[M].Paris,1921.[5]Brown,C.Payne,M.E.Fiveessentialstepsofprocessinvocabularylearn ing[A].PaperpresentedattheTESOLConvention,Baltimore,Md ,1994.[6]Cienki,A.2007.Frames,IdealizedCognitiveModels,andDo mains[C]//D.GeeraertsH.Cuyckens.TheOxfordHandbookofCognitiveLinguistics.Oxf ord:OUP:171-187.[7]Coulson,S.2006.SemanticLeaps:Frame-shiftingandConceptualBlendinginMeaningConstruction[M]. Cambridge:CambridgeUniversityPress.[8]Dirven,R.M.Vespoor.2004.CognitiveExplorationofLanguageandLingui stics[M].Amsterdam/Philadelphia:JohnBenjamins.[9]Dixon,R.M.W.1991.ANewApproachtoEnglishGrammar,onSem anticPrinciples[M].Oxford:OxfordUniversityPress.110.[10]DowtyDR.ThematicRolesandSemantics[C].BerkeleyLingu isticsSociety,1986,12:340-354.[11]DowtyDR.OntheSemanticContentoftheNotionThematicRol e[M].//BPartee,GCherchia,RTurner.Properties,TypesandMe anings.Vol.2.Dordrecht:Kluwer,1989:19-130.[12]DowtyDR.Thematicproto-rolesandargumentselection[J].Language,1991,67:574-619.[13]Evans,V.M.Green.2006.CognitiveLinguistics:AnIntroduction[M].Ed inburgh:EdinburghUniversityPress.[14]Fillmore,C.1970.Thegrammarofhittingandbreaking[A]. InR.JacobsP.Rosenbauin(eds.).ReadingsinEnglishTransformationalGr ammar[C].Waltham,Mass.:GinnCo..120-33.[15]Fillmore,C.1976a.Framesemanticsandthenatureoflangu age[J].AnnalsoftheNewYorkAcademyofSciences:Conferenceo ntheOriginandDevelopmentofLanguageandSpeech280:20-32.[16]Fillmore,C.1976b.Theneedforaframesemanticsinlingui stics[J].StatisticalMethodsinLinguistics12:5-29.[17]Fillmore,C.1977.TheCaseforCaseReopend[A].InP.ColeJ.Sadock(eds.).SyntaxandSemantics(Vol.8):GrammaticalRe lations[C].NewYork:AcademicPress.59-81.[18]Fillmore,C.1982.FramesSemantics[A].InTheLinguistic SocietyofKorea(ed.).LinguisticsintheMorningCalm[C].Seo ul:Hanshin.111-37.[19]Fillmore,C.1985.Framesandsemanticsofunderstanding[ J].QuadernidiSemantica6(2):222-54.[20]Fillmore,C.1986.“U”-semantics,secondround[J].QuadernidiSemantica7(1):49-58.[21]Fillmore,C.JB.S.T.Atkins.1992.TowardaFrameBasedLexicon:TheSemantic sofRISKandItsNeighbors[C]//A.LehrerandE.F.Kittay.Frame s,FieldsandContrast:NewEssaysinSemanticsandLexicalOrga nization.Hillsdale,NJ:LawrenceErlbaum:75-102.[22]Fillmore,C.,C.JohnsonM.Petruck.2003.BackgroundtoFrameNet[J].InternationalJo urnalofLexicography16(3):235-250.[23]Fillmore,C.J.2006.FrameSemantics[A].InA.Anderson,G .Hirstler(eds.).EncyclopediaLanguageandLinguistics.Vol.4(2ndEdition)[Z].Amsterdam:Elsevier:613-620.[24]Fromkin.AnIntroductiontoLanguage[M].Orlando:Harcou rtBraceCollegePublishers.[25]Goffman,E.1974.FrameAnalysis[M].Boston:Northeaster nUniversityPress.[26]JackendoffR.Semanticstructure[M].Cambridge,MA:MITP ress,1990:43.[27]Katz,J.J.Fordor,J.A.1963.TheStructureofaSemanticTheory[M].InLan guage,39:170-210[28]Lakoff,George.MetaphorsWeLiveBy[M].Chicago:TheUniv ersityofChicago,1980[29]Lakoff.G.Johnson.M.PhilosophyintheFlesh:TheEmbodiedMindandItsCh allengetoWesternThought[M].NewYork:BasicBooks,1993.[30]Levi-Strauss,C.StructuralAnthropology[M].(translatedbyJacob sonandBrookeGrundfestScheoepf).Harmondsworth:Penguin,1 972[31]Lowe,J.B.,C.F.BakerC.J.Fillmore.1997.Aframe-basedsemanticapproachtosemanticannotation[EB/OL].http: //.[32]Martin,Willy.1997.Aframe-basedapproachtopolysemy[A].InHubertCuyckensandBrittaAa wada(eds.).PolysemyinCognitiveLinguistics:SelectedPape rsfromthe5thInternationalCognitiveLinguisticsConferenc e[C].Amsterdam:JohnBenjaminsPublishingCompany,57-81.[33]Minsky,M.1975.AFrameworkforrepresentingknowledge[A ].InP.Winston(ed.).ThePsychologyofComputerVision[C].Ne wYork:McGraw-Hill.211-77.[34]PaulJ.Hopper,ElizabethClassTraugott.Grammaticaliza tion[M].Cambridge:CambridgeUniversityPress,1993.[35]Rosch,Eleanor.Ontheinternationalstructureofpercept ualandsemanticcategories[C]//TimothyE,Moore.Cognitived evelopmentandtheacquisitionoflanguage.NewYork:Academic Press1973:111-44.[36]Saeed,J.I.1997.Semantics[M].Oxford:Blackwell.[37]Sweetser.E.FromEtymologytoPragmatics:Metaphoricala ndCulturalAspectsofSemanticStructure[M].Cambridge:Camb ridgeUniversityPress,1990.[38]Talmy.L.2000.TowardaCognitiveSemantics(Vol.1).Conc eptStructureSystems[M].Cambridge,MA:MITPress.[39]Taylor,J.LinguisticCategorization:PrototypesinLing uisticTheory[M].Beijing:ForeignLanguageTeachingandRese archPressOxfordUniversityPress,1995.[40]Trier,Jost.DerdeutscheWortschatzimSinnbezirkdesVer standes[M].Heidelberg:Winter,1931.参考文献二:[1]Allan,K.LinguisticMeaning[M].2volumes,London:Routle dgeKeganPaul,1986:385[2]Allerton,D.J.StretchedVerbConstructionsinEnglish[M] .LondonandNewYork:Routledge,2002:113[3]Aronoff,M.K.Fudeman.WhatisMorphology?(Secondedition)[M].Wiley-Blackwell,2011:139[4]Baker,A.E.K.Hengeveld.Linguistics[M].Wiley-Blackwell,2012:221[5]Bloomfield,nguage[M].London:GeorgeAllen UnwinLtd.,1935[6]Bouchard,D.TheSemanticofSyntax:ANominalistApproacht oGrammar[M].Chicago:TheUniversityofChicagoPress,1995:3 13[7]Carstairs-McCarthy,A.AnIntroductiontoEnglishMorphology:WordsandT heirStructure[M].Edinburgh:EdinburghUniversityPress,20 02:49[8]Chomsky,N.StudiesonSemanticsinGenerativeGrammar[M]. TheHague:Mouton,1972[9]Croft,W.D.A.Cruse.CognitiveLinguistics[M].Cambridge:CambridgeU niversityPress,2004:137[10]Dowty,D.R.Onthesemanticcontentofthenotion‘themati crole’.InB.Partee,G.Chierchia,andR.Turner(eds)Propert ies,TypesandMeanings[M],volume2.Dordrecht:Kluwer,1989: 69[11]Evans,V.AGlossaryofCognitiveLinguistics[M].Edinbur gh:EdinburghUniversityPressLtd,2007:6[12]Fillmore,C.J.TheCaseforCase.InE.BachandR.Harms(eds )UniversalsinLinguisticTheory[M].NewYork:Holt,Rinehart Winston,1968[13]Geeraerts,D.TheoriesofLexicalSemantics[M].Oxford:O xfordUniversityPress,2010[14]Givon,T.Syntax:aFunctional-TypologicalIntroduction,Vol.2[M].Amsterdam:JohnBenjami ns,1990:66[15]Goldberg,A.E.Constructions:AConstructionGrammarApp roachtoArgumentStructure[M].Chicago:UniversityofChicag oPress,1995[16]Halliday,M.A.K.IntroductiontoFunctionalGrammar[M]. London:Arnold,1994[17]Huang,C.T.J.BetweenSyntaxandSemantics[M].NewYork:R outledge,2010:347[18]Jackendoff,R.SemanticInterpretationinGenerativeGra mmar[M].Cambridge,MA:MITPress,1972:29-46[19]Jackendoff,R.SemanticStructures[M].Cambridge,MA:MI TPress,1990:43[20]Jesperson,O.ThePhilosophyofGrammar[M].NewYork:W.W. NortonCompany,1924[21]Koptjevskaja-Tamm,M.Nominalizations[M].Routledge,1993[22]Langacker,R.W.FoundationsofCognitiveGrammar,Vol.II ,DescriptiveApplication[M].Stanford:StanfordUniversity Press,1991[23]Langacker,R.W.InvestigationsinCognitiveLinguistics [M].Berlin:MoutondeGruyter,2009[24]Leech,G.N.Semantics[M].Harmondsworth:Penguin,1983[25]Marantz,A.OntheNatureofGrammaticalRelations[M].Cam bridge,Massachusetts:TheMITPress,1984:13[26]McMahon,A.R.McMahon.EvolutionaryLinguistics[M].Cambridge:Cambrid geUniversityPress,2013:135[27]Miller,D.G.EnglishLexicogenesis[M].Oxford:OxfordUn iversityPress,2014:7[28]Nida,E.A.C.R.Taber.TheTheoryandPracticeofTranslation[M].Leiden: E.J.Brill,1969[29]Payne,T.E.UnderstandingEnglishGrammar:ALinguisticI ntroduction[M].Cambridge:CambridgeUniversityPress,2011[30]Rathert,M.A.Alexadou.TheSemanticsofNominalizationsacrossLanguage sandFrameworks[M].DeGruyterMouton,2010[31]Riemer,N.IntroducingSemantics[M].Cambridge:Cambrid geUniversityPress,2010:87[32]Roark,B.putationalApproachestoMorphologyandSyntax[ M].Oxford:OxfordUniversityPress,2007:116[33]Saeed,J.I.Semantics[M].Beijing:ForeignLanguageTeac hingandResearchPress,2000:140-143[34]Trauth,G.P.K.Kazzazi.RoutleageDictionaryofLanguageandLinguistics[ M].Beijing:ForeignLanguageTeachingandResearchPress,200 0:327[35]安丰存.题元角色理论与领有名词提升移位[J].解放军外国语学院学报,2007(3):11-17[36]蔡基刚.英语写作与抽象名词表达[M].上海:复旦大学出版社,2003:3-21[37]常玲玲.对特殊句式论元结构的思考:投射或构式?[J].外语研究,2013(1):20-27[38]陈安定.英汉比较与翻译[M].北京:中国对外翻译出版公司,1998[39]成军.论元结构构式与动词的整合[J].外语学刊,2010(1):36-40[40]丛迎旭,王红阳.基于语义变化的概念语法隐喻模式与类型[J].现代外语,2013(1):33-39阅读相关文档:公共管理专业毕业论文参考文献土木工程专业论文参考文献经济学博士学位论文提纲管理学毕业论文提纲模板教育经济学毕业论文提纲模板动力工程硕士毕业论文开题报告会计专业毕业论文开题报告范例旅游管理开题报告范文本科生毕业论文开题报告模板法律硕士论文开题报告税务毕业论文开题报告医院财务内部控制与信息化管理研究企业财务管理信息化探讨企业财务信息化管理建设探析企业财务内控管理制度探讨港口企业财务风险管理及策略财务全面预算管理在企业中的运用自然资源资产离任审计体系的构建自然资源资产离任审计探讨自然资源资产离任审计评价体系研究财政预算改最新最全【办公文献】【心理学】【毕业论文】【学术论文】【总结报告】【演讲致辞】【领导讲话】【心得体会】【党建材料】【常用范文】【分析报告】【应用文档】免费阅读下载*本文若侵犯了您的权益,请留言。

LangacKer的事件认知模型与语言编码中的工具格

LangacKer的事件认知模型与语言编码中的工具格邵琛欣【摘要】Based on cognitive grammar,this paper maKes use of LangacKer’s Event Model to ex-plain the argument features,syntactic distribution and marKers shown by the instrumen-tal case in linguistic encoding. As an important component of action chain,the argu-ment features of the instrumental case should be distinguished from location and time, focusing on quasi-internal arguments;the variation of highlighted scenes enables the instrumental case to serve assubject,object,adverbial and complement;preposition and affix are two forms of the instrumental case,either with a different event integration process.%本文从认知语法角度,运用LangacKer的事件模型,对工具格在语言编码中表现出的论元属性、句法分布和标记形式等问题做出新的解释。

作为行为链中重要的组成部分,工具格的论元属性应区别于处所和时间,倾向于准内部论元;场景侧重的不同使工具格可以充当主语、宾语、状语、补语等多种句法成分;介词和词缀是工具格的两种形式,二者有着不同的事件整合过程。

【期刊名称】《贵州民族大学学报(哲学社会科学版)》【年(卷),期】2016(000)002【总页数】11页(P125-135)【关键词】认知语法;事件模型;语言编码;工具格【作者】邵琛欣【作者单位】陕西师范大学文学院陕西西安710119【正文语种】中文【中图分类】H1作者邵琛欣,女,汉族,天津人,陕西师范大学文学院讲师,博士(陕西西安710119)。

复旦外国语言文学论丛格式要求

胡壮麟.《语篇的衔接和连贯》.上海:上海外语教育出版社,1994.

(5)中文论文集中的论文

李明.英汉双语词典之我见.《双语词典新论:中国辞书学会双语词典专业委员会第七届年会论文集》.罗益民、文旭编.成都:四川人民出版社,2007.29-33.

(6)中文期刊中的论文

魏向清、杨蔚.对我国双语词典编纂与出版策略的反思.《辞书研究》,2008(3):1-8.

《复旦外国语言文学论丛》格式要求

电子文本需具备下列部分:中文标题、中英文摘要、中英文关键词、正文、参考文献、附录(如有)、作者信息(包括作者姓名、出生年份、研究方向、单位、通讯地址、联系电话、E-mail地址等)。

一、全文

1.字号:中文(除脚注外)一律用宋体5号简体,注意是“钱钟书”,而非“钱锺书”;英文字体一律用Times New Roman小4号;脚注由WORD文档自然生成;

第一级:“一、”“二、”“三、”

第二级:“1.”“2.”“3.”

第三级:“(1)”“(2)”“(3)”

第四级:“①”“②”“③”

2.图表编号一律采用阿拉伯数字,如“表1”“图1”。

3.正文中的外文人名、书名均需有相应的中文译名,第一次出现时,正文显示中文译名,相应的外文译名置于括号内,如是人名,一般只用其姓,而在括号内用外文显示其姓和名,如“马克思(Karl Marx)”,此后如无特别需要,一律不再出现外文。

五、参考文献

1.用“参考文献”的措辞,且不加任何标点符号;

2.凡是文中所引用的文献必须在内,此外可适当增加一些最重要的参考文献,但不宜过多;

2.英文文献在前,中文文献在后,统一按作者姓氏字母顺序排序,同一作者的不同作品,按作品名第一个单词的首字母排序,若英文作品第一个单词为“a”或“the”,则按第二个单词排序;

国外认知语言学研究现状综述

国外认知语言学研究现状综述[作者:王德春张辉来源:《外语研究》2001年3期点击数:更新时间:2005-10-11 文章录入:xhzhang]【字体:】1.引言二十世纪七十年代末和八十年代,许多语言学家认识到生成语法研究范围的局限性,开始从认知的角度来研究语言现象。

八十年代末,认知语言学初步形成,其标志是第一届国际认知语言学大会(Duisburg, Germany 1989)的召开和1990 年《认知语言学》杂志(Cognitive Linguistics)的出版。

认知语言学大会每二年召开一次,至今,已举办了七届。

在整个八十年代和九十年代初,出版了一批摘引率较高的认知语言学著作。

例如Lakoff 和Johnson(1980), Talmy(1983), Fillmore(1985), Fauconnier(1985), Lakoff(1987), Langacker(1987,1991),Talmy(1988),Rudzka-Ostyn (1988), Lakoff 和Turner (1989),Sweetser(1990) 和认知语言学研究系列(CLR)第一辑Langacker(1989)。

这些著作确立了认知语言学的基本研究框架。

该框架有以下五个研究主题:(1)语言研究必须同人的概念形成过程的研究联系起来。

(2)词义的确立必须参照百科全书般的概念内容和人对这一内容的解释(construal)。

(3)概念形成根植于普遍的躯体经验( bodily experience),特别是空间经验,这一经验制约了人对心理世界的隐喻性建构。

(4)语言的方面面都包含着范畴化,并以广义的原型理论为基础。

(5)认知语言学并不把语言现象区分为音位、形态、词汇、句法和语用等不同的层次,而是寻求对语言现象统一的解释。

目前,认知语言学研究呈现出多样化并涉及到语言现象的各个方面,在本文中我们试选出几个有重要理论价值的研究,简述其来龙去脉和主要的研究成果,并指出认知语言学的一些发展趋势。

心理扫描下集体名词作主语的主谓一致分析

心理扫描下集体名词作主语的主谓一致分析云南师范大学邓亚萍摘要:认知入场理论可以运用心理扫描的方式解决英语集体名词的主谓一致问题,即集体名词的单复数概念的选择㊂心理扫描包括整体扫描和顺序扫描,这是基于人类认知体验方式所形成的,所以更有助于英语学习者更好地理解集体名词作主语时的主谓一致问题㊂关键词:认知入场理论;心理扫描;集体名词;主谓一致中图分类号:H319.35 文献标识码:B 文章编号:1672-4186(2019)3-0124-011 引言集体名词因有被于人们认知世界的方式,人类认知世界事物的顺序都是从简单到复杂,具体到抽象㊂面对集体名词做主语时,谓语的单复数应该做何种处理㊂认知语法的核心思想为意义是决定句法表征的根本所在,即集体名词的意义决定了谓语单复数形式的根本所在,为了解决集体名词做主语,主谓一致问题解决的根本就是探寻其句法表征意义如何产生的过程㊂认知入场理论中的心理扫描更容易解决此问题㊂2 集体名词作主语的心理扫描构建2.1 认知语法认知语法的核心思想即就是基于使用和基于象征的语言意义的阐释,表征了语法是由语音极和语义极的整体概念化得出的㊂认知语法是认知语言学的核心理论,且解释语言现象的实质是基于人类认知识解的一种方式,所以基于认知语法的视角去阐释语言现象是从根本上解决语言现象的视角㊂本文所考查的集体名词做主语时主谓一致问题,由于集体名词是人们通过认知识解形成的意向图示,在实际的语言使用中依据意义的传达加以细致化阐述㊂本文试图运用认知语法中的心理扫描方式去探寻句法表征的意义的产生㊂2.2 整体扫描整体扫描是人类认知世界的第一步,即对所观事物抑或事件首先进行整体的把控㊂例:那本书㊂此言语事物 那本书 被提及时,听者或读者首先启动自己的认知整体性对那本书进行整体样貌的把握(书的形状㊁厚薄㊁大小)㊂2.3 顺序扫描基于上文提及的整体的心理扫描,言者问及 这是一本什么书 ?在此言语事件的驱动下,通着启动自我的顺序心理扫描对 那本书 进行更细致的阐述:什么题材㊁字体大小㊁适用人群等㊂2.4 集体名词作主语的心理扫描基于人类观察是事物抑或事件最普遍的心理扫描过程:整体扫描和顺序扫描,试图对集体名词的语义进行阐释㊂例: family 这一名词被提及时,如若概念化者启动其整体心理扫描,该词被识解为整体概念,做主语时,谓语动词使用单数形式;如若概念化启动其顺序扫描,对 family 中的成员进行一一辨识,该词就被识解为复数概念,做主语时,谓语动词采用复数形式㊂3 集体名词作主语的主谓一致分析基于前文对集体名词不同的观察方式表明:采用整体扫描时,谓语动词用单数;采用顺序扫描时,谓语动词用复数㊂3.1 谓语动词用单数例1:Thisclassconsistsof45pupils.在此言语事件中,言者谈及的是班级里的学生数45名,因此概念化者启动的是顺序扫描的观察方式对这一班级的人数进行考量,因为学生组成的班级是一个整体,概念化者启动整体扫描进行阐释,表征的是一个整体的概念,所以当class作主语时谓语动词用单数㊂例2:Ourclothingprotectsusfromthecold.在此言语事件中,概念化者启动整体扫描的观察方式,将 ourclothing 视为一整体概念,并没有采取顺序扫描的观察视角对衣服进行细致识解,所以在此情况下,谓语动词用单数㊂3.2 谓语动词用复数例1:ThisclassarestudyingEnglishnow.在此言语事件中,概念化者启动顺序扫描的观察方式,表征的是这个班级的学生在学英语,而非班级在学英语,所以在此言语事件中做主语,谓语动词采用的是复数形式㊂例2:Thepolicearelookingforhim.在此言语事件中,概念化者启动顺序扫描的观察视角对警察的数量进行识解,所以做主语时,谓语动词应采用复数形式以期与主语相匹配而构成合乎语法的句法表征㊂4 结语本文运用认知语法中观察事物抑或事件采用的心理扫描方式,解决集体名词做主语时,谓语动词单复数形式的背后认知机制㊂得知:概念化者启动整体扫描的观察方式时谓语动词用单数形式,概念化者启动顺序扫描的方式观察事物抑或事件时,谓语动词用复数的形式㊂参考文献:[1]Langacker,R.W.FoundationsofCognitiveGrammar,Vol.2:DescriptiveApplications[M].Standford:StandfordUni⁃versityPress,1991.[2]Langacker,R.W.CognitiveGrammar:ABasicIntro⁃duction[M].NewYork:OxfordUniversityPress,2008.[3]Taylor,J.R.CognitiveGrammar[M].Oxford:OxfordUniversityPress,2002.[4]邢晓宇.认知入景视角下现代汉语名词的修饰语研究:功能与语序漂移[D].重庆:西南大学,2014.421。

意象图式理论在英语词汇教学中的应用

/104意象图式理论在英语词汇教学中的应用罗天琪 华北理工大学外国语学院摘要:意象图式是认知语言学的重要理论之一。

本文以意象图式理论为基础,阐述了意象图式理论在英语词汇教学中介词和一词多义现象的应用,从根源上解释词义,加深对英语词汇义项之间的联系,对词汇意义的拓展和词汇教学有着重要意义。

关键词:意象图式;词汇教学;应用1. 意象图式理论1987年,Johnson在《心中之身》中首次提出“意象图式”(Image Schema)的概念。

他们认为意象图式是我们视觉,动觉中反复出现的动态结构,用来帮助理解认知体验,在分析隐喻,建构范畴,理解概念等方面起着重要作用。

同时,提出了理想化认知概念这一观点,理想认知模式包括命题模式、意象图式模式、隐喻模式和转喻模式四种认知模式。

其中,诸如“整体—部分”,“中心—边缘”,“容器—内容”和“上—下”等抽象的理想化的建立于日常空间体验基础上认知模式即是“意象图式”。

因此,意象图式就是人们通过身体体验和认知对外部事物在人类头脑中空间化的结构图式。

1988年,Talmy提出了力量——动态图式。

Langacker(2004)指出,意象图式具有原型性的结构特征和高度的抽象性,是人们对个例反复体验和感知,不断概括抽象出来的结构。

同时,意象图式可以建构心智空间和认知模型(CM),从而揭示语义概念。

2. 意象图式在介词教学中的应用英语介词的教学和习得一直是一个重点和难点。

传统教学认为介词具有规约性,将介词的每个义项和搭配列出,忽视介词与搭配词之间的联系。

认知语言学认为,意象图式能够很好的解释介词的意义与搭配。

Tayor(2003)把参照物称作界标(landmark,LM),被定位的实体叫做射体(trajector,TR)。

界标和射体的关系显示了介词的不同意义。

例如,介词over的中心意象图式由射体、界标和路径构成。

例:(1)Mike jumped over the fence.(2)The kites are flying over the house.(3)The bridge is over the river.(4)Peter lived over the mountain.在例(1)中,反映了射体Mike和界标the fence之间的动态关系。

LectureLangackerCognitiveGrammar解读

[[TREE]/[tree]]]

back

2. Preliminary Conditions for the Construction of LK

先天生理条件

基本认知能力

CL, CxG Chomsky LAD

使用频率

Type Token

持“普遍语法假说”的TG学派

语言知识是人类先天具有的知识,是UG的一部分,以此为 蓝图,人类就具有了习得语言的能力,无需通过归纳获得。 习得语法就如同定制“软件包”(Jackendoff 2002):所 有的东西都在里面,学习者只需选择合适的参数,语言的 使用则通过形式化的演算来操作。语言研究仅需处理核心 语法,异质的语言现象则统统发配到词库“大监狱”中。 (刘玉梅 2010 现代外语)

另外:

Taylor: Cognitive Grammar in 2002

总目标

认知语法对语言结构作出全面、统一的解释,具有:

直觉上的自然性being intuitively natural 心理上的现实性psychologically plausible 经验上的可行性empirically viable

会发音。(2008:8)

大量经验证据表明,语言使用者的语法知识并非UG,而是 基于使用而抽象概括出的构式,这才是语言知识在人类心

智中的基本表征形式,是必须通过后天习得的。

语言知识的概括可以从语用、信息结构、认知过程等诸多

方面得到合理的解释,绝非仅仅形式化的符号运算。

这一转变不但可以处理“核心”语法现象,更能有效地解 释被TG抛至词库“大监狱”中的“边缘”语法现象,从而 达到对所有语言现象作出统一解释的目的。

例

如

接着!厨子丢了个小木片,“这是你的粮票,领饭前先秀一下,否 则就没饭吃”。(《龙枪传奇》)

美国语言学简史

派

别

按照不同学术观点分为:

(1)人类语言学派——鲍阿斯、萨丕尔、赫叶尔、哈斯、斯瓦迪希 (2)耶鲁派:这一派以耶鲁大学为中心。主耍成员有布龙菲尔德、霍凯 特、海里斯、布洛克等人。他们主耍继承布龙菲尔德的学说,主张机械主 义,反对心理主义。 (3)密歇根派:这一派成员多数出自密歇根大学。主要成员有派克、奈 达、弗里斯等人。他们主要继承了萨丕尔的学说,利用心理学、社会学和 人类学的知识解释语言现象。 (4)麻省派:这一派的成员主要集中在麻省理工学院。主要成员有乔姆 斯基、哈勒、波斯塔、罗斯等人。他们最初继承和发展了海里斯的学说, 以后提出了一整套转换一生成语法的理论。 (5)加州派(以加州大学为中心):——费尔摩、麦考莱、莱科夫

20世纪上半叶结构主义在美国是主流派 ,到了下半叶 ,生成 语法替代了它的位置。随着认知科学 (cognitive science) 逐步 引起人们的注意,美国基于认知的语言研究也开始兴起。实际 上 , 乔姆斯基的语言理论也是基于认知主义的 , 不过他还没有 形成现代意义上的认知语言学。目前最引人注目的认知语言 学的代表人是兰格克(Ronald W. Langacker)。他在1976年就提 出了“空间语法”(space grammar),以后在1987和1991年先后 出版了他的名著《认知语法基础》(Foundations of Cognitive Grammar) 。 此 外 , 戴 浩 一 和 谢 信 一 的 “ 组 成 认 知 语 法 ”(Compositional Cognitive Grammar)也正在成长。兰格克注 重概念,戴谢二人注重语言信息传递的功能。认知语法有三条 基本假设:

(1)语言不是一个自足的认知系统,语言描写必须参照 人的一般认知规律; (2)句法不是一个自足的形式系统,它和词汇都是约定 俗成的象征系统(symbolic system),句法分析不能脱离 语义; (3)语义不等于真值条件,语义要参照知识系统。语义 也就是“概念化”(conceptualization)。 兰格克认为语言是认知实体。他不同意乔姆斯基把 语言知识看成是能生成的内在语法,所谓语言能力也 就是掌握语言习俗。他十分重视语言符号的象征功 能 , 主 要 运 用 “ 隐 喻 ” (metaphor) 和 “ 意 象 ”(imagery)来解释概念化的过程。

名词化的语篇建构功能

名词化的语篇建构功能作者:谭万俊来源:《现代交际》2014年第12期[摘要]名词化作为语法隐喻的典型实现形式,按照其产生的“一致式”的语言精密度而言可分为两类:类转移(class-shift)和级转移(rank-shift)。

名词化的语篇建构功能根植于语言的建构性,在不同类型的语篇中其语篇建构功能的表现模式也不同。

[关键词]名词化语篇建构功能表现模式[中图分类号]H03 ;[文献标识码]A ;[文章编号]1009-5349(2014)12-0043-01名词化作为一种词类转换现象,普遍存在于语言之中,这种语言现象引起了各个学派的关注和研究,如传统语法学派、生成语言学、功能语言学、认知语言学等。

这些学派往往主要研究名词化的形式构成和界定,名词化的生成过程,名词化的概念功能和语篇衔接功能,名词化的认知概念实质和特点。

然而,对于名词化的语篇建构功能很少论及,本文欲从系统功能语言学的角度来探讨名词化的语篇建构功能。

一、名词化(一)名词化的界定名词化是一种非常复杂的语言现象,对于名词化的界定当然也是多角度的。

Quirk等(1985:1289)在传统语法的框架内从词性转换的角度界定了名词化:“在形态上与小句结构的谓语系统对应的名词短语”,并且还指出名词化不仅用于具有具体意义的名词,还可用于具有抽象意义的名词。

这一界定通过一组句子中相对应成分的类比关系,在形式上揭示了名词化的特征,对其语义特征的变化研究不足。

认知语言学家Langacker(1987:183)认为:“名词就是能指派事物语义极的象征结构,它凸显的是一组相关联的实体,而非实体间的关系”。

这一界定从语义概念的识解上真正揭示了名词短语或者名词化的实质,名词化是一个过程,一种识解世界的方式。

系统功能语言学认为名词化就其产生的“一致式”的语言精密度(delicay)来说,可分为:类转移(class-shift)和级转移(rank-shift)。

类转移的名词化就是把某个过程或特征看做事物,只是词性发生变化即词类的转移;级转移的名词化表现为一个小句或者小句复合体打包成一个名词或名词词组,在这个名词化的过程中小句的级阶发生变化,呈现为级阶的下降。

Langacker认知语法与Goldberg构式语法

Langacker认知语法与Goldberg构式语法认知语言学中的语法研究有两种主要的理论模型,一种是以Langacker为代表的认知语法,另一种是Goldberg等人的构式语法。

认知语法强调用语法以外的因素来解释语法现象。

构式语法是一门研究说话者知识本质的认知语言学理论。

构式语法的起因是对一些边缘语言现象的研究,因而构式概念成了构式语法的核心,并由此引申到对全部语言现象的讨论。

标签:认知语法构式语法构式对比研究一、认知语法认知语法通常指以Langacker为代表的一派认知语言学家所从事的研究,强调用语法以外的因素来解释语法现象。

认知语法从名称上看似是对语言的认知研究范式的统称,其实是对Langakcer语言研究方法的专指。

Langacker所提倡的“认知语法”主要从人类的“认知和识解”角度研究语言结构,研究人类语言系统的心智表征,克服了传统语法过分强调客观标准、忽视主观认识的倾向,充分考虑到人的认知因素在语言结构中的反映,着重用人类的基本认知方式来识解语言的规则,开创了语法研究的全新思路。

(王寅,2007:316)Langacker的《认知语法基础》(Foundations of Cognitive Grammar)确立了认知语法的基本理论和框架。

Langacker所创建的认知语法,主要运用“象征单位”和“识解”等来分析语言的各个层面,包括词素、词、短语、分句和句子,即音系层(语言形式)象征语义层(概念内容),词汇、形态和句法构成一个象征单位的连续体。

“认知语法注重描写形式(音位、书写,但不包括语法形式)与意义(语义、语用、语篇信息功能等)相配对结合的象征单位,语法被视为是一个约定俗成的、有结构层次的象征单位的大仓库”(王寅,2007:337)。

认知语法最突出的有两点:一是句法部分不是独立的,而是与词汇、语素连为一体的符号系统的一部分;二是语义结构因语言而异,语义结构中有一层层约定俗成的映像,语义结构是约定俗成的概念结构,语法是语义结构约定俗成的符号表征。

能愿动词“要”的主要语法化机制

《助动词“要”的汉代起源说》中详细介绍“要”的虚化过程。在他看来,“要”主要经历两大过程。(1)由名词向动词的演变。(2)由动词向助动词的演变。在此我觉得还应补充第三大过程:(3)助动词内部的语义虚化。因为前两步可概括为实词转化为语法虚词,而虚化并非就此完成,它在确立能愿助词的语法功能后还得进一步虚化,从而扩展其情态意义。第三步看似并不明显,耐人思索。

必要式形成于两汉魏晋南北朝时期,而意志式主要形成于唐代,将然态出现时间靠后,大约是宋代。这段演化史充分证明了情态动词的语义发展过程:它们最初只是名词,随后出现相应的动词意,实义动词逐步虚化为情态动词,情态动词进一步衍生各种现成的情态意义。

3.“要”的主要语法化机制

不同的语言学家为说明各自的理论往往会对术语的界定不同。Eve Sweester就以上三种可能相用两大情态意义概括:根情态(root modality)和知识情态(epistemic modality)。根情态实质上包括了社会自然世界中的情态意义,是义务相与原动相的总称。她选择这套术语更为了充分说明情态动词的隐喻化理论。

关键词: 能愿动词 “要”语法化 深层机制

“语法化”通常指语言中意义实在的词转化为意义虚化,表示语法功能的成分这样一种语言演变的过程或现象。中国传统语言学称之为“实词虚化”,例如汉语里的“把”“被”“从”等词原来都是实义动词,现已虚化为为介词,即西方的功能词(function words)。

1.2实义动词演变为助动词

我们知道,由于时间的一维性,决定了同一时间位置上的两个动词,只能选取一个具有指示“时间信息”有关的句法特征的动词来计量,这便是主要动词,其它的则处于次要地位,帮助主要动词表达情态意义,而发展成为助动词。

cognitive grammar

Reference Resolution within the Framework of Cognitive GrammarSusanne Salmon-AltLaboratoire Loria, FranceLaurent RomaryLaboratoire Loria, FranceFollowing the principles of Cognitive Grammar, we concentrate on amodel for reference resolution that attempts to overcome thedifficulties of previous approaches, based on the fundamentalassumption that all reference (independent on the type of the referringexpression) is accomplished via access to and restructuring of domainsof reference rather than by direct linkage to the entities themselves.The model accounts for entities not explicitly mentioned butunderstood in a discourse, and enables exploitation of discursive andperceptual context to limit the set of potential referents for a givenreferring expression. As the most important feature, we note that ourmodel can with a single mechanism handle what are typically treatedas diverse phenomena. Our approach, then, provides a freshperspective on the relations between Cognitive Grammar and theproblem of reference.Keywords: reference, cognitive grammar, context model, noun phrasesemantics1. IntroductionThe work presented in this paper can be situated within a wider attempt to define man-machine dialogue systems that respects the fundamental communication means of their users. In particular, even when the underlying task to be achieved through such dialogue systems is limited (e.g. instructional dialogues or information querying), we make the assumption that the intrinsic richness of language may be observed and thus has to be taken into account in those systems. As a consequence, possible models for such phenomena should be both computationally valid, since they have to be implemented and integrated within real systems, but also, and foremost, linguistically sound, as they should provide a coverage asCognitive Science Quarterly (2000) 1, ..-..good as possible of the variety of cases that real observation may confront us with. In this paper, we will attempt to show how this objective can be realised in the domain of reference resolution, which is a crucial factor of success for a dialogue system with regards its user’s acceptance as a good intermediate to achieve their task. More specifically, we try to see to what extent formalising a cognitive model, namely Langacker’s Cognitive Grammar (1987, 1991) , is a way to maintain both linguistical soundness and coverage, but also computational validity.It’s a fact that the complexity of reference resolution is due, in part, to the variety of referring expressions, including pronominal reference, definite description, demonstratives, etc. The problem is made even more complex by the apparent variety of mechanisms required to deal with just one of these types of referring expression. For example, the referent of a definite description may be linked to a prior entity within the discourse, “bridged” to a prior entity from which it can be inferred, or accommodated in the discourse domain (Bos et al. 1995; Vieira and Poesio 2000).Moreover, much work on reference centres on pronominal reference (Kamp and Reyle 1993; Lappin and Laess 1994; Grosz et al. 1995; Mitkov 1998). As a result, the treatment of other types of referring expressions is typically seen as an extension of or variation on the basic co-referential mechanism involved in pronominal reference. Such an approach, however, does not predict essential differences between the use of pronouns, definite descriptions and demonstratives in contexts where human users would have clear preferences.Yet, our aim is to design a model of reference resolution to be implemented in human machine dialogue systems. Since it has been shown by psycholinguistic studies (Vivier et al. 1997) that it is very difficult and unnatural to impose restrictions on the spontaneous use of referring expressions, we need a unified model of reference, e.g. a model which handles with a single mechanism different types of referring expressions: definite descriptions, demonstratives and pronouns.One of the backbones of a model for reference resolution is the context model. It is intended to save relevant contextual information for the attribution of referents to referring expressions. Several context models for reference interpretation have already been proposed. Among the best known, Grosz and Sidner (1986) explore the relation between intentional discourse structure and limits of the referential space, modelled as a stack of focus spaces. Centering Theory (Grosz et al. 1995) proposes mechanisms for pronominal reference resolution between adjacent discourse units, based on a partially ordered list of entities introduced within them. Discourse Representation Theory (Kamp and Reyle 1993) constructs a global context,Cognitive Science Quarterly (2000) 1, ..-..comprising all potential referents introduced in the discourse, for which accessibility constraints are defined based on syntactic criteria.A first problem of these approaches is that linking is considered as the basic operation for referent attribution. As a result, additional mechanisms have to be introduced for other types of relations, such as bridging or accommodation (Lascarides and Asher 1993; Bos et al. 1995). However, the systematic preference for linking seems to be questionable not only from a linguistic point of view (Corblin 1987), but also from an empirical one: as shown by Poesio and Vieira (1998), it does not correctly reflect the use of definite descriptions in corpora. Following the authors, about 50% of definite descriptions in a newspaper corpus are used to introduce a new entity in the discourse, and 18% are used as bridging. This means that about 70% of definite descriptions are not actually “linked” to a prior discourse entity. Additionally, we observed through the referential annotation of task-oriented dialogue corpora that it often seems counter-intuitive to link a definite description to a discursive antecedent even mentioned far ahead, when the referent is directly accessible in the visual environment (Salmon-Alt, 2001c). Finally, the linking principle is not entirely suitable for the referential treatment of one-anaphora (the red one), other-expressions (the other triangle) and ordinals (the first triangle). These expressions seem to suppose, rather than a directly accessible entity to which they can be linked, a locally activated context set from which the referent can be extracted.A second problem concerns the internal structure of the context model. The basic entities of the context models that we have introduced are previously mentioned discourse referents. This seems to be insufficient, because reference resolution relies not only on discursive information, but equally on conceptual knowledge and visual information (Cremers 1996). Furthermore, whereas DRT provides access to all previously mentioned entities, CT considers the previous discourse unit only. However, within the list of identified potential referents, CT provides a precise account of relative salience, whereas DRT specifies only syntactic constraints to narrow the list. Some recent models attempt to apply more precise selection criteria to global discourse (Asher 1993; Hahn and Strube 1997). But they rely on some prior discourse analysis, a strategy that presupposes the ability to automatically recognise discourse structure, and implicitly assumes that discourse analysis precedes reference resolution.A third problem with these approaches is the context updating operation. We believe that context updating intended to reflect at least some cognitive mechanisms should consist of more than just introducing and linking entities. More precisely, we consider that referring is not only identifying a referent, but also, imposing a particular point of view on the referent and the manner it has been isolated within a set of potential referents. The idea thatCognitive Science Quarterly (2000) 1, ..-..“a word or an utterance, since it not only specifies the perceived referent but also the set of excluded alternatives, contains more information that the simple perception of the event itself” has already been defended by Olson (1970:265). We assume that this feature should be used to enhance the predictive power of a model of reference calculus. See for instance example (1):(1) The green block supports the big pyramid but not the red one. (Winograd 1972)Without taking into account the fact of having identified the first block based on its colour, it is indeed impossible to resolve correctly the reference for the elliptic expression the red one in example (1). In particular, a heuristic strategy consisting in choosing the nominal head of the most recent noun phrase as an “antecedent” would fail here.To summarise, the following propositions are prerequisites for any model that attempts to overcome these three problematic points:– It should take into account all the linguistic variety of referring expressions.– It should consider that the basic mechanism common to all types of reference is not linking. Rather, it is an extraction from locally activated sets of referents, which are created based on discursive, perceptual and conceptual information.– It should propose a mechanism of context restructuring which overcomes the standard operations of introducing and linking referents by keeping information about activated context sets and differentiation criteria actually used.The next section shows how these properties are related to the theoretical foundations of Cognitive Grammar. Section 3 presents the basic principles underlying a cognitive, rather than linguistic model of reference. Section 4 applies the principles to an example.2. Basics of Cognitive Grammar2.1 Some theoretical foundationsCognitive Grammar (Langacker 1986, 1991) situates linguistic competence within a more general framework of cognitive faculties by assuming that language is neither self-contained, nor describable without reference to cognitive processing. A speaker’s linguistic knowledge is characterised as a structured inventory of conventional units: phonological units combine with semantic units to form symbolic units, which may be of any size, from a morpheme to a sequence of sentences (van Hoek 1995).Cognitive Science Quarterly (2000) 1, ..-..A first fundamental assumption of Cognitive Grammar is that syntax is not an independent component of linguistic analysis. Basic grammatical categories as well as complex syntactic rules are represented by maximally schematic symbolic units - acquired and adjusted through exposure to actually occurring structures - which are used in constructing and evaluating new expressions. As a second basic assumption, sense is not represented by logical forms. The first reason for this is that semantic structures are characterised relative to knowledge systems that are essentially open-ended. Secondly, the meaning of a given expression cannot be reduced to an objective characterisation of the situation described: equally important for semantics is how the speaker chooses to construe the situation. Therefore, Cognitive Grammar assumes a conceptual rather than truth-conditional semantics, considering that meaning consists of a process of conceptualisation, i.e. activation and restructuring of conceptions in a hearers mind.More precisely, the conceptualisation of an expression is said to impose a particular image on its domain. A domain is defined as a cognitive structure that is presupposed by the semantic pole of an expression. The particular image imposed by the expression emerges through the profiling of a substructure of the domain, namely that substructure which the expression designates. The profiled subpart of a domain is hypothesised to be more prominent or more highly activated than the domain. However, the semantic value of an expression neither resides in the profile, nor in the domain, but rather in a relationship between the two.As an example, the semantics of the expression roof presupposes the conception of H OUSE and profiles a specific subpart of it (Figure 1a). The expressions parent profiles a more abstract conception, being characterised with respect to the conception of a K INSHIP N ETWORK(Figure 1b) It is important to note first that any cognitive structure can function as a domain - a concept, a conceptual complex, a perceptual experience, an elaborated knowledge system etc. Secondly, most expressions require more than one domain for their full description. The expression knife for example, is characterised, among others, by its shape specification (Figure 1c), its canonical rule in the process of cutting (Figure 1d), its inclusion in a typical place setting with other pieces of cutlery (Figure 1e).Cognitive Science Quarterly (2000) 1, ..-..Figure 1 – Profiling domains (Langacker 1991)2.2 Suitability for our purposeGiven our purpose – developing a model of reference resolution suitable for dialogue systems – the biggest problem with Cognitive Grammar is the lack of formalisation. It has, however, several nice properties with regard to the requirements we defined for a cognitive model of interpreting referring expressions (see the end of section 1). We focus here on these properties, before presenting in the next section (3) a model that integrates them into a framework sufficiently formal to have been implemented into a real dialogue system.The basic assumption about the meaning of linguistic expressions - profiling a substructure within a domain - leads to an explanation of the difficulties induced by considering linking as the basic referential operation. As we suggested before, the fundamental mechanism for interpreting referring expressions seems not to be a linking operation, but rather an extraction from a presupposed domain.If one accepts this point of view, bridging as well as one-anaphora integrate the picture without problems. Indeed, the referent of the roof in example (2) is extracted from the conceptual domain introduced by the house. In (3), the referent of the red one is extracted from a domain of coloured blocks, the same domain from which the referent of the green block has been extracted before. Additionally, linking is not excluded definitely, since it can be seen as a particular instantiation of an extraction operation. For example, the block in (4) is not considered as directly linked to the block mentioned before, but as extracted from a set introduced by the block and the pyramid.(2) The house is nice, but the roof has to be renovated.(3) The green block supports the big pyramid but not the red one. Moreover, this manner of considering reference basically as an extraction and not as a linking operation leads to an explanation of the differences between (4) and (5): whereas (4) sounds fine, the repetition of the block in (5) seems to be sub-optimal, compared to the use of the pronoun it like in (6). The explanation for this observation is the lack, in (5), of a suitable domain from which the referent could be extracted. In this case, the use of a pronoun is preferred. Whereas this phenomenon has been repeatedly noted in linguistic work (Corblin 1987; Gaiffe et al. 1997), current implementations doCognitive Science Quarterly (2000) 1, ..-..not account for these observations. Furthermore, an explanation based exclusively on “cognitive statuses” of the referents (Ariel 1990; Gundel et al. 1993) is insufficient: it is not evident where the difference between the cognitive statuses of the block introduced in the first utterances of (4) and (5) is. Consequently, the difference between the uses of a definite description in (4) and (5) cannot be predicted correctly.(4) The block supports the pyramid. The block is big.(5) The block supports nothing. The block is big.(6) The block supports nothing. It is big.Besides the assumption that linguistic meaning is profiling a sub-structure within a given domain, a second interesting aspect of Cognitive Grammar is the fact that these cognitive domains are not essentially linguistic constructs. Rather, they are based on different knowledge systems, including encyclopaedic and visual information. This property is particularly helpful for dealing not only with bridging references like in the previous example (2), but also with reference to perceptual entities such as in (7), where the referent of the red block has not been mentioned before, but is accessible within the visual environment (Cremers 1996). Considering that cognitive domains are built from different knowledge systems allows then to integrate different uses of descriptions (anaphoric, associative, situational – see the classification of Hawkins (1978) into a unified model of reference.(7) Take the red block !Third, a fundamental claim of cognitive semantics is that the interpretation of an expression is not only the description of a given situation. An equally important fact is construal, e.g. the way that facets of the conceived situation are portrayed. This claim corresponds closely to the one made by Olson (1970:265): “An appropriated utterance indicates which cues or features are critical, while a picture does not. Therefore, there is more information in an utterance than in the perception of an event out of context.” Applied to the interpretation of referring expressions, this means that the task is not completely done with the identification of the referent. Rather, it encompasses the identification of a local reference domain and updating the structure of this domain, by profiling the entity designated by the expression. As a result, not only the referent is identified and profiled as the most prominent element of its domain, but also the entire domain is activated, and therefore more accessible for the identification of further referents.Cognitive Science Quarterly (2000) 1, ..-..3. From Cognitive Grammar to a model of referenceresolution3.1 OverviewFollowing the principles of Cognitive Grammar, we concentrate on a model for reference resolution that attempts to overcome the difficulties discussed in the introduction. The model is based on the fundamental assumption that all reference (independent on the type of the referring expression) is accomplished via access to and restructuring of domains of reference rather than by direct linkage to the entities themselves.As shown in the previous section (2.2), Cognitive Grammar underlines the need of local context structures. Indeed, an expression is said to be interpreted within a limited domain, presupposed by its semantics, rather than within a global context model containing the list of all previous discourse referents. Therefore, the context representation has to furnish such domains. The next section (3.2) presents a context model built up on domains of reference, which are identifying representations for (possibly partitioned) subsets of contextual entities. We will show in particular that these domains are not primarily linguistic constructs, since they are introduced and updated via discourse, perception or conceptual knowledge.elaboration unification restructuring Figure 2 – Overview of the model for processing a referring expression“D N”Cognitive Science Quarterly (2000) 1, ..-..Based on a context modelled by domains of reference, we describe in section 3.3 the interpretation process for referring expressions. We adopt here the hypotheses of Cognitive Grammar about the representation of meaning in terms of abstract symbolic schemas: more precisely, we assume that the semantics of a given expression can be represented by a schema which corresponds to an underspecified domain of reference. The underspecified domain itself is calculated by elaborating abstract schemas for nouns and determiners – presupposed in Cognitive Grammar – depending on the semantics of the constituents of the expression being interpreted. The interpretation process properly speaking consists of a unification of the underspecified domain with a suitable domain of reference from the context model and the profiling of a sub-structure – the referent – of this domain (Figure 2).3.2 The context model3.2.1 Basic unitsThe basic units of our context model are reference domains. Following Sanford and Garrod (1982), Johnson-Laird (1987), Langacker (1991) and Reboul et al. (1997), we consider that reference domains are mental representations for entities to which it is possible to refer, including individual objects, collections of objects, events or states. The main difference between a mental representation of an entity and a representation of the entity itself is that a mental representation is not supposed to characterise entirely the entity. This reflects the fact that an expression introducing a new referent does not exhaust the potential features of this referent. Rather, it presents the entity from one or several particular points of view for which we assume in the following that it is the most likely to be activated for referential access to the entity.Basically, a reference domain is created each time a new entity is introduced in the discourse, but it may also be created for newly perceived entities. The representation of a reference domain consists of attribute-value pairs, minimally including a unique identifier and a type. Type information is derived from a set of generic domains, organised as a type hierarchy, which include general encyclopaedic knowledge or knowledge specific to the application and is assumed to exist prior to discourse processing. Other information provided via the discourse (e.g., specific properties of the object) and via perception (e.g., shape, colour, etc. for objects viewed on a screen) may be added as necessary.The most important feature of a reference domain are zero, one or more partitions. A partition gives information about possible decompositions of the domain. It could be based on previous discourse information, perceptual information or conceptual knowledge inherited from the generic domains.Cognitive Science Quarterly (2000) 1, ..-..The elements of a partition are pointers to other representations, which represent explicitly identified sub-components of the domain. They must be distinguishable from all the other sub-components by the value of a differentiation criterion, which represents a particular point of view on the domain and therefore predicts a particular referential access to its elements. For example, a domain of two marbles (@M, Figure 3) may contain partitions on the basis of colour (a red one and a blue one), position (the one on the right and the one on the left), etc.Figure 3 – Reference domain for one blue marble (@m1) and for agroup of two marbles (@M)Within a partition, at most one element may be profiled, according to perceptual or discursive prominence. Profiling is the result of specific operations on the domains, i.e. grouping and extraction. Grouping is briefly discussed below, and extraction, as a part of referential interpretation, is presented in the next section.3.2.2 The grouping operationThe grouping operation is intended to structure the entities of the context model by grouping existing domains into more complex ones. The main goal of this operation is to create new domains and to make them available for the interpretation of referring expressions in the continuation of the discourse. The grouping operation can be triggered by discursive and perceptual factors.Cognitive Science Quarterly (2000) 1, ..-..Grouping on discursive factors is defined parallel to the assembly (or elaboration) of complex expressions: in Cognitive Grammar, complex symbols are created by integrating elements at both the semantic and phonological poles. Let us focus on the semantic composition of an example – the line on the left of the circle. Figure 4a shows the abstract schema or prototypical meaning of the preposition on the left of. It profiles a relationship between two things arranged in a horizontally oriented space. In Cognitive Grammar, relational predications involve an additional prominence asymmetry: the most prominent entity is termed the trajector (tr), and a less prominent one the landmark (lm).In our example, the abstract schema for on the left of is successively elaborated by the representations for the circle and the line, leading to a composite conception, with the line as the landmark, and therefore the most prominent element (Figure 4b).Parallel to Cognitive Grammar, the grouping operation of our model maintains the main characteristics of this assembly: it takes two or more domains as the arguments and returns a complex domain with a partition for the grouped elements. Figure 5a diagrams the grouping operation for the same example. Triggered by a discursive factor – here the preposition – the representations for the line (@L) and the circle(@C) are grouped into a complex domain, partitioned by two properties of the elements: their type and their position. The prominent element of the partition – the representation for the line – is the focused element of the domain (indicated by grey background).Additionally to discursive triggers (preposition, co-ordination, enumeration, arguments of the same predicate), grouping may be triggered by perceptual factors. We consider for instance that perceptual criteria such as similarity or proximity lead to the grouping of contextual entities. Algorithms for grouping visual entities following the principles of the Gestalt-Theory (Wertheimer 1923) can for example be found in Thorisson (1994). Depending on the type of the grouping trigger, at most one element of a complex domain may be prominent. The treated example – grouping triggered by the preposition on the left of – gives indeed raise to a domain containing a focused entity (Figure 5a). However, grouping does not automatically lead to a focused domain: if the operation is triggered by co-ordination, the resulting domain does not contain any prominent entity (Figure 5b).To sum up, the context model contains domains of reference, which represent referents or sets of referents. A domain is characterised at least by type information and partitions, providing access to other domains. Partitions are either inherited from generic representations (for example the partition of an entity H OUSE into a R OOF, W INDOWS etc.), or the result of aCognitive Science Quarterly (2000) 1, ..-..grouping operation, triggered by discourse or perceptual information. The three fundamental structural characteristics of domains – important to keep in mind for the interpretation process – are the following:– domain without any partition (@m1, Figure 3) ;– domain with a partition, but without any prominent item (Figure 5b);– domain with a partition containing a prominent item (Figure 5a).tr lmFigure 4 – Assembly of complex expressions in Cognitive Grammar:“the line on the left of the circle”Figure 5 – Grouping operation, triggered by a preposition (a) and by aco-ordination (b)Cognitive Science Quarterly (2000) 1, ..-..3.3 Interpretation of referring expressionsThe context model presented in the previous section provides domains with one of the three fundamental structures mentioned before. Given this context representation, we consider that the role of a referring expression is to select one (or more, in case of ambiguity) of these domains and to restructure it by profiling the referent. The selection operation is constrained by the requirement of compatibility between the selected contextual domain and the underspecified domain construed for the expression being interpreted. In the following sections, we successively present:– the principles for calculating the underspecified domain depending on the semantics of a given expression (section 3.3.1);– the selection and unification procedure (section 3.3.2);– the restructuring operation, leading to the identification of the referent and to an updated and activated domain of reference (section 3.3.3).The three steps can be considered as going – from left to right – through the diagram of Figure 2.3.3.1 Calculus of the underspecified domain of referenceThe underspecified domain associated with a referring expression being interpreted is calculated on the basis of its semantics and depends on two criteria:– the abstract semantic schema for determiners, elaborated by the semantics of the current determiner;– the abstract semantic schema for nouns (Figure 6), elaborated by the semantics of the components of the current expression.The semantics of the determiner associated to the noun then combines with the schema for the noun in order to elaborate a composite representation.。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

Book review

Toward a Cognitive Semantics

Leonard Talmy,The MIT Press,Cambridge,MA,2000

Leonard Talmy is a leading light of cognitive linguistics,known especially for his work in cognitive semantics,an approach to linguistics that aims to describe the linguistic representation of conceptual structure.The two-volume set ‘‘Toward a Cognitive Semantics’’is a collection of 16of Talmy’s papers spanning roughly 30years of his thinking and writing.The papers have been updated,expanded,revised,and arranged by concept into chapters.This review of the volumes is tailored to a non-specialist linguist or cognitive scientist interested in a general orientation to the contents and presentation.

In the introduction common to the two books,Talmy situates cognitive linguistics within the discipline of linguistics and identifies his primary methodology as introspection.The ‘‘overlapping systems model’’of cognitive organization is outlined,in which cognitive systems,such as language,vision,kinesthetics,and reasoning can and do interact.Talmy proposes ‘‘the general finding that each system has certain structural properties that are uniquely its own,certain structural properties that it shares with only one or a few other systems,and certain structural properties that it shares with most or all the other systems.These last properties would constitute the most fundamental properties of conceptual structuring in human cognition.’’The reader is guided to specific chapters in which the linguistic system is compared to other cognitive systems of visual perception,kinesthetic perception,attention,understanding/reasoning,pattern integration,cognitive culture,and affect.

Each volume of the set is about 500pages long,with eight chapters organized into three or four major sections.The first volume,‘‘Concept structuring systems’’expounds Talmy’s vision of the fundamental systems of conceptual structuring in language.Part 1presents a theoretical orientation,Part 2addresses configurational structure,Part 3discusses the distribution of attention,and Part 4describes force dynamics.The second volume,‘‘Typology and process in concept structuring,’’turns from conceptual systems themselves to the processes that structure concepts and the typologies that emerge from these.Part 1looks at the processes on a long-term scale,longer than an individual’s lifetime,that deal with the representation of event structure.Part 2considers the short-term scale of cognitive processing with a look at online processing,and Part 3addresses medium-term processes in the acquisition of culture and the processing of narrative.

In volume 1,Chapter 1,‘‘The relation of grammar to cognition,’’is a greatly revised and expanded version of a 1988paper,itself an expansion of papers from 1977and 1978.This paper details the ‘‘semantics of grammar’’in language,toward the larger goal of determining the character of conceptual structure in general.Talmy proposes that the fundamental design feature

/locate/pragma

Journal of Pragmatics 38(2006)1126–1134

0378-2166/$–see front matter #2005Elsevier B.V .All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.pragma.2005.08.007。