2010年南京大学英语专业(基础英语)真题试卷.doc

2010高考江苏英语(含解析)

25. —I haven’t got the reference book yet, but I’ll have a test on the subject next month.

—Don’t worry. You______ have it by Friday.

A. could

B. shall C. must D. may _ w

选 D. by no means 表示绝不 It depends. 表示看情况而定.

28. The retired man donated most of his savings to the school damaged by the earthquake in

Yushu ,________the students to return to their classrooms. A. enabling w_ w w. k# s5_ u.c o *m

work still harder.

A. next to B. far from C. out of D. due to

选 B. far from 表示 not at all . next to 表示仅次于 due to 表示因为,由于

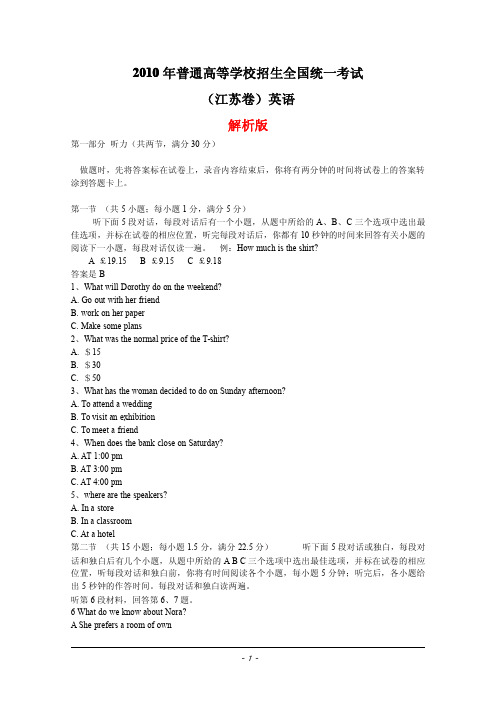

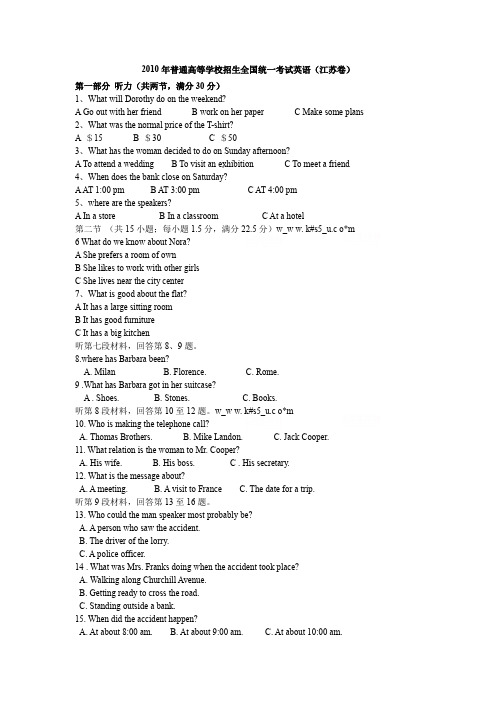

2010 年普通高等学校招生全国统一考试 (江苏卷)英语 解析版

第一部分 听力(共两节,满分 30 分)

做题时,先将答案标在试卷上,录音内容结束后,你将有两分钟的时间将试卷上的答案转 涂到答题卡上。

第一节 (共 5 小题;每小题 1 分,满分 5 分) 听下面 5 段对话,每段对话后有一个小题,从题中所给的 A、B、C 三个选项中选出最

C She lives near the city center

7、What is good about the flat?

2010年高考英语试卷及答案【江苏卷】

英语作文常用谚语、俗语1、A liar is not believed when he speaks the truth. 说谎者即使讲真话也没人相信。

2、A little knowledge is a dangerous thing. 一知半解,自欺欺人。

3、All rivers run into sea. 海纳百川。

4、All roads lead to Rome. 条条大路通罗马。

5、All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy. 只会用功不玩耍,聪明孩子也变傻。

6、A bad beginning makes a bad ending. 不善始者不善终。

7、Actions speak louder than words. 事实胜于雄辩。

8、A faithful friend is hard to find. 知音难觅。

9、A friend in need is a friend indeed. 患难见真情。

10、A friend is easier lost than found. 得朋友难,失朋友易。

11、A good beginning is half done. 良好的开端是成功的一半。

12、A good beginning makes a good ending. 善始者善终。

13、A good book is a good friend. 好书如挚友。

14、A good medicine tastes bitter. 良药苦口。

15、A mother's love never changes. 母爱永恒。

16、An apple a day keeps the doctor away. 一天一苹果,不用请医生。

17、A single flower does not make a spring. 一花独放不是春,百花齐放春满园。

18、A year's plan starts with spring. 一年之计在于春。

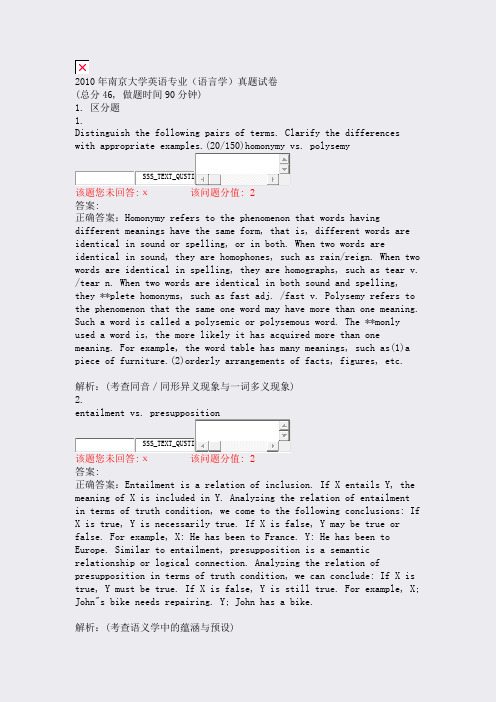

[考研类试卷]2010年南京大学英语专业(基础英语)真题试卷.doc

![[考研类试卷]2010年南京大学英语专业(基础英语)真题试卷.doc](https://img.taocdn.com/s3/m/2cdba3177c1cfad6185fa711.png)

[ 考研类试卷 ]2010 年南京大学英语专业(基础英语)真题试卷一、名词解释0 For the definition given in each item in questions 11 to 15, find a matching word in the specified paragraph. The number given after each definition indicates the paragraph in which the word appears.(1x5)1pretension to knowledge not possessed(2)2adjustment(3)3appearing periodically(4)4display of narrow-minded learning(7)5bodies invisible to the naked eye(13)二、阅读理解6THE STUDY OF MANIrving S. Lee1The study of man—even, the scientific study—is ancient and respectable. It goes back to Aristotle, to Hippocrates, and beyond them to obscure beginnings. Today, it is one of the chief studies of the learned. Like our other activities, it may be divided into two parts, the successful part and the unsuccessful part. Speaking very generally and with due regard to numerous and important exceptions, it may be said that the successful part of the scientific study of man is related to medicine, the unsuccessful part to philosophy and to the social sciences. These relations are not only historical, they are also to be seen in methods, attitudes, and traditions.2The successes of medicine and the medical sciences have not been lightly won; from a multitude of failures, they are the survivals and the fortunate productions of tile best or the most-favored men among an endless succession of skillful physicians though pedantry, incompetency, and charlatanry have often hindered and, in evil times, even arrested the accumulations of medical science for long periods, since Hippocrates, at least, the tradition of skillful practice has never been quite lost the tradition that combines theory and practice. This tradition is, especially in three elements,indispensable.3Hippocrates teaches, first, hard, persistent, intelligent, responsible, unremitting labor in the sickroom, not in the library;the all-roundadaptation of the doctor to his task, anadaptation that is far from being merely intellectual. This is adaptation chiefly through the establishment of conditioned reflexes. Something like it seems to be a necessary part of the mastery of any material or of effective work in any medium.4Hippocrates teaches, secondly, accurate observation of things and events; selection, guided by judgment born of familiarity, of the salient and the recurrent phenomena; and their classification and methodical exploitation.5Hippocrates teaches, thirdly, the judicious construction of a theor—y not a philosophical theory, nor a grand effort of the imagination, nor a quas—i religious dogma, but a modest pedestrian affair, or perhaps I had better say, a useful walking stick to help on the way.6All this may be summed up thus: The physician must have, first, intimate habitual intuitive familiarity with things; secondly, a systematic knowledge of things; and thirdly, an effective way of thinking about things.7Experience shows that this is the way to success. It has long been followed in studying sickness, but hardly at all in studying the other experiences of daily life. Let us, therefore, consider more carefully what Hippocrates did and what he did not do. He was in reaction chiefly against three things: firstly, against the ancient, traditional myths and superstitions which still prevailed among the physicians of his day; secondly, against the recent intrusion of philosophy into medical doctrine; thirdly, against the extravagant system of diagnoses of the Cnidian School, a body of contemporary physicians who seem to have suffered from a familiar form of professional pedantry. Here, Hippocrates was opposing the pretentious systematization of knowledge that lacked solid, objective foundation—the concealment of ignorance, probably more or less unconsciously, with a show of knowledge. Note well that such concealment is rarely altogether dishonest and may be practised in thorough good faith.8The social sciences today suffer from defects that are not unlike the defects of medicine to which Hippocrates was opposed. Firstly, social and political myths are everywhere current, and if they involve forms of superstition that are less apparent to us than the medical superstitions of long ago, that may well be because we recognize the latter class of superstitions for what they are while still accepting or half accepting the former class. Secondly, there is at least as much philosophy mingled with our current social science as there was at any time in the medical doctrines ofthe Greeks. Thirdly, a great part of the social science of today consists of elaborate speculation on an insufficient foundation of fact.9Hippocrates endeavored to avoid myths and traditional rules, the grand search for philosophical truth, the authority of philosophical beliefs, the concealment of ignorance with a show of systematic knowledge. He was concerned, first of all not to conceal his own ignorance from himself.10Experience shows that there are two kinds of human behavior which it is ordinarily convenient and often essential to distinguish.11One is the thinking, talking, and writing, by those who are so familiar with relevant concrete experiences that they cannot ordinarily forget the facts, about two kinds of subjects. These are;firstly, concrete observation—s observations and experiences which are representable by means of sharply defined or otherwise unambiguous words; and secondly, more general considerations, dearly and logically related to such concrete observations and experiences.12The other kind of behavior is thinking, talking, and writing about vague or general ideas or "concepts" which do not clearly relate to concrete observations and experiences and which are not designated by sharply defined words.13In the social sciences, special methods and special skills are few. It is hard to think of anything that corresponds to a mathematician's skill in performing mathematical operations or to a bacteriologist's skill in cultivating microorganisms or to a clinician's skill in making physical examinations.14Classificatory, descriptive knowledge, which is so conspicuous in the medical sciences and in natural history and which has proved so essential to the development of such sciences, is relatively lacking in the social sciences. Moreover, there is no common accord among social scientists concerning the classes and subclasses of the things they study, and there is even much disagreement about nomenclature.15The theories of the social sciences seem to be in a curious state. One body of theory, that of economies is highly developed, has been cast in mathematical form, and has reached a stage that is thought to be in some respects definitive. This theory, like those of the natural sciences, is the result of the concerted efforts of a great number of investigators and has evolved in a manner altogether similar to the evolution of certain theories in the natural sciences. But it is hardly applicable to concrete reality.16The reasons why economic theory is so difficult to apply to concrete events are that it is an abstraction from an immensely complex reality and that reasoning from theory to practice is here, nearly always vitiated by "thefallacy of misplaced concreteness. " Such application suggests the analogy of applying Galileo's law of falling bodies to the motion of a falling leaf in a stiff breeze. Experience teaches that under such circumstances it is altogether unsafe to take more than a single step in deductive reasoning without verifying the conclusions by observation or experiment. Nevertheless, many economists, some cautiously and others less cautiously are in the habit of expressing opinions deduced from theoretical considerations concerning economic practice. There is here a striking contrast with medicine, where it is almost unknown for a theorist inexperienced in practice to prescribe the treatment of a patient.17In other fields of social science, theories are generally not held in common by all investigators, but, as in philosophical systems, tend to be sectarian beliefs. This is true even in psychology where the conflicts of physiological psychologists, behaviorists. Gestaltists, and others sometimes almost suggest theological controversy.18On the whole, it seems fair to say that the social sciences in general are not cultivated by persons possessing intuitive familiarity; highly developed, systematic, descriptive knowledge; and the kind of theories that are to be found in the natural sciences.19There is not a little system-building in the social sciences but, with the striking exception of economic theory, it is of the philosophical type rather than of the scientific type, being chiefly concerned in its structural elements with words rather than with things, or in old fashioned parlance, with noumena, rather than with phenomena.20A further difference between most system-building in the social sciences and systems of thought and classification of the natural sciences is to be seen in their evolution. In the natural sciences, both theories and descriptive systems grow by adaptation to the increasing knowledge and experience of the scientists. In the social sciences, systems often issue fully formed from the mind of one man. Then they may be much discussed if they attract attention, but progressive adaptive modification as a result of the concerted efforts of great numbers of men is rare. Such systems are in no proper sense working hypotheses; they are "rationalizations" , or, at best mixtures of working hypotheses and "rationalizations".21Thinking in the social sciences suffers, I believe, chiefly from two defects:One is the fallacy of misplaced concreteness; the other, the intrusion of sentimen—tsof Bacon's Idols—into the thinking, which may be fairly regarded as an occupational hazard of the social scientists.22Sentiments have no place in clear thinking, but the manifestations of sentiments are among the most important things with which the social sciences are concerned. For example, the word "justice" is out of place in pleadingbefore the Supreme Curt of the United States, but the sentiments associated with that word and often expressed by it are probably quite as important as the laws of our country, not to mention the procedure of the Supreme Court. Indeed such sentiments seem to be in many ways and at many times the most important of all social forces.23The acquired characters of men may be divided into two classes. One kind involves much use of reason, logic, the intellect; for example, the ordinary studies of school and university. The other kind involves little intellectual activity and arises chiefly from conditioning from rituals and from routines; for example, skills, attitudes, and acquired sentiments. In modified form, men share such acquired characters with dogs and other animals. When not misinterpreted, they have been almost completely neglected by intellectuals and are frequently overlooked by social scientists. Their study seems to present an opportunity for the application of physiology.24The conclusions of this comparative study are as follows: Firstly, a combination of intimate, habitual, intuitive familiarity with things; systematic knowledge of things; and an effective way of thinking about things is common among medical scientists, rare among social scientists. Secondly, systems in the medical sciences and systems in the social sciences are commonly different. The former resemble systems in the other natural sciences, the latter resemble philosophical systems. Thirdly, many of the terms employed currently in the social sciences are of a kind that is excluded, except by inadvertence, from the medical sciences. Fourthly, sentiments to not ordinarily intrude in the thinking of medical scientists; they do ordinarily intrude in the thinking of social scientists. Fifthly, the medical sciences have made some progress in the objective study of the manifestations of sentiments; the social sciences, where these things are particularly important, have neglected them. This is probably due to the influence of the intellectual tradition " Sixthly" in the medical sciences, special methods and special skills are many; in the social sciences, few. Finally, in the medical sciences, testing of thought by observation and experiment is continuous. Thus, theories and generalizations of all kinds are constantly being corrected, modified, and adapted to the phenomena; and fallacies of misplaced concreteness, eliminated. In the social sciences, there is little of this adaptation and correction through continuous observation and experiment.25These are very general conclusions to which, as I have already said, there are numerous and important exceptions. Perhaps the most important exceptions may be observed in the work of many historians, of purely descriptive writers, and of those theoretical economists who scrupulously abstain from the application of theory to practice.6Hippocrates was chiefly concerned with .( A)not concealing his own ignorance from himself( B)combining philosophy with medical doctrine( C)the system of diagnosis of the Cnidian school( D)pretentious systematization of knowledge( E)incorporating tradition with systematic knowledge7Most social science systems are, at best, .( A)mixtures of working hypotheses and rationalizations( B)results of concerted efforts of men at adaptive modification( C)adaptations of experience and increasing knowledge to experiments( D)highly developed systems of knowledge( E)studies of the structural elements of things8One branch of the social sciences considered in some respects definitive is .( A)history( B)philosophy( C)sociology( D)politics( E)economics9The social sciences today suffer from defects similar to the defects of medicine in Hippocrates' day, as evidenced by all but one of thesestatements. Which one?( A)Forms of superstition are less apparent today because we half accent them.( B)The concealment of ignorance is as thoroughly dishonest today as it was before.( C)Elaborate speculation is based on poor foundation of fact.( D)Much philosophy is mingled with current social science.( E)Social and political myths are everywhere current.10The tradition of skillful medical practice since Hippocrates' time combines theory and practice. Which description inaccurately represents this tradition?( A)Hard, persistent, intelligent, unremitting labor in the sickroom.( B)Evidence of accurate observation, selection, classification, and methodical exploitation of phenomena.( C)Judicious construction of a modest workable theory.( D)Hard, responsible, intelligent, unremitting labor in the library.( E)All-round adaptation of the doctor to his task as a type of master workman.11The author firmly believes the scientific study of men .( A)comparative religion( B)natural philosophy( C)social science( D)medical science( E)theoretical economics12Which of the following is NOT a conclusion of the author based on his comparative study?( A)Effective thinking is rare among social scientists.( B)In the medical sciences, testing of thought by observation and experiment is continuous.( C)Sentiments ordinarily intrude in the thinking of medical scientists.( D)Social sciences have neglected the objective study of the manifestations of sentiments.( E)Terms employed in the social sciences are of a kind excluded from the medical sciences.13By "the fallacy of misplaced concreteness" , the author means .( A)apprenticeship in a hospital is the only effective preparation for practice( B)the expressing of opinions deduced from theoretical considerations rather than experiment and observation( C)the prescribing of treatment for a patient by an experienced intern( D)treatment of illness by specialists in each field( E)theoretical deductions verified by observation and experimentation14According to the writer, the social sciences suffer from both the fallacy of misplace concreteness and .( A)excessive experimentation( B)judicious theory construction( C)intrusion of sentiments( D)too much observation and checking( E)ancient myths15One may infer that the author's views are .( A)universally accepted by medical students( B)accepted by social scientists( C)not acceptable to Gestaltists( D)parallel to those of economists( E)disputed by many professions15For the given word in each item in questions 16 to 20, decide which semantic variation best conveys the meaning of the author. The number given after each word indicates the paragraph in which the word appears.(1x5)16prevailed(7)( A)existed widely( B)produced the desired effect( C)gained the advantage17 pretentious(7)( A)assumptive of dignity( B)making exaggerated show; ostentatious( C)claiming importance or title18 conspicuous(14)( A)readily attracting attention; striking( B)plainly visible; manifest( C)undesirably noticeable19 fallacy(16)( A)false idea( B)deceitfulness( C)erroneous reasoning 20 sectarian(17)( A)pertaining to a particular school of thought( B)member of a sect( C)bigoted三、句子改错21All high schools attach great importance youngster's performance in the College Entrance Examinations.22He could not say "hippopotamus" and "pomegranate" , and we had to help him to pronounce.23"How to open the door?" , he asked as he turned the key, but the door did not open.24This was a farm where you could find all kinds of birds: chickens, quails, turkeys, ducks and geese and so on.25The boy biked to school but realized that he has forgotten his homework.26It was bad news that all boys in the class were caught skipping the PEclass. Another news, however, was encouraging:all of them passed the math exam.27The teacher got impatient that after explaining the past tense many times and giving many examples, the pupils still wrote "I play football yesterday".28All the sophomores said that they wanted to be a good student.29The teacher found it dissatisfied that students failed to hand in their homework on time.30 A wrong information he gave me is that our shuttle bus leaves at 3. As a result, I missed it.四、汉译英31Translate the following passage into English.(25)建城近2500年来,南京一直是中国多元文化交融共进的中心城市之一。

2010年本科入学考试英语试题

金 陵 协 和 神 学 院 2010年本科入学考试·英语试题(总分100分,答题时间180分钟)注意: 本试卷共11页,请将1-80题的选择答案填到第11页的答题表中。

第一部分:词汇与语法(共40题,每题1分,共40分)1. John wrote his name and phone number on a _________ of paper. A) lump B) sheet C) tube D) slice2. He often writes to his parents. He writes ____________. A) frequently B) occasionally C) sometimes D) now and then3. My teacher says I am a good student, and I hope that is ______. A) fair B) exact C) correct D) equal4. He gave a large ______ of money to the church. A) some B) number C) amount D) piece5. Sue forgot to bring her textbook, so she asked if she could ___ her classmate’s book.A) lend B) lends C) borrows D) borrow6. He always goes ____________ after school. A) to home B) to house C) home D) to the house7. You must give up watching TV now. You must _____ right away. A) end B) stop C) surrender D) begin8. “Yes, _____________,” the girl said. “I would be happy to help you.”A) off course B) course C) because D) of course9. He needed some spare parts for a machine at work, so he ______ them.A) asked B) begged C) thanked D) requested10. Mr. Jones has a house in California and _______ in New York. A) another B) other C) else D) different11. How _______ is Nanjing ________ Shanghai? A) long…away B) away …till省份 姓名 准考证号码答题不超过此装订线C) distance…to D) far…from12. Jeff has been in China for a year, so his parents haven’t seen him _______ lastApril.A) from B) for C) since D) by13. The boy just ____ the Bible for the first time, so there were many things he didn’tunderstand.A) read B) reads C) red D) reading14. Did you climb ________mountain all the way to the top?A) the hole B) the all C) the whole D) all of15. _________ money does he have in the bank?A) How many B) How muchC) How D) How few16. My friend, ___________ brother works in the church, just got married.A) whose B) whose his C) his D) of whom17. What kind of car did your father _______ ten years ago?A) drive B) drives C) drove D) driven18. My friend has ___________ beautiful house!A) so B) such a C) such D) a such19. “Don’t do that!” he shouted ________ a loud voice.A) in B) with C) on D) over20. I can’t find my bike. It isn’t _________ where I put it.A) their B) theirs C) they’re D) there21. The patient was told to take the medicine ________ .A) one day twice B) two times one dayC) twice a day D) one day two times22. He ________ the football club of the university.A) is belonged to B) is belongedC) belongs D) belongs to23. In this school, there are about 200 students _______ music, dancing or dramatics.A) study B) are studyingC) to study D) studying24. ________ in 1508, the bridge is about 500 years old.A) Being built B) Built C) Having built D) Building25. If I were you, I ________ worry so much.A) couldn't B) mustn't C) wouldn't D) needn't26. It is not clear ________ they will continue the work or not.A) that B) whether C) if D) that if27. Some of the students were reading magazines and _______ were just turning overthe pages.A) the other B) others C) some students D) some other28. "Go down this road ______ you find a space free," the camper said.A) when B) before C) until D) as soon as29. Last year summer I went to France. This year I'm going to Italy _______ .A) in spite B) rather C) instead D) despite30. This is the strangest thing ________ heard about.A) I have ever B) I have neverC) ever I have D) never I have31. You will never be able to enter that university ______ you get very high scores inthe examinations next month.A) if B) as C) although D) unless32. _________ we have no money, we can't buy it.A) For B) Since C) While D) That33. Then an old man ________ gray hair entered the room.A) of B) in C) with D) for34. It's not surprising that as a successful businessman, my friend Martin is not ______he was when he graduated five years ago.A) that B) what C) how D) why35. He considered ________ to see Paul in person.A) going B) be going C) to go D) to be going36. ______ Tuesday evening at eight, Major Joyce will give a lecture in Bailey Hall on"My Experience in China."A) In B) At C) Of D) On37. They are determined to make their voice ________ .A) hear B) to hear C) heard D) hearing38. ______ do you prefer, a government without newspapers or newspapers without agovernment?A) What B) How C) Which D) Why39. The girl was shocked at the horrible scene, as if ______ into a nightmare.A) had walked B) walked C) walking D) to walk40. I don't understand why you ______ the same mistakes!A) are keeping making B) are kept to makeC) keep to make D) keep making第二部分完形填空(共20题,每题1分,共20分)阅读下面的短文,掌握其大意,然后从41-60各题所组成的四个选项中,选出一个最佳答案。

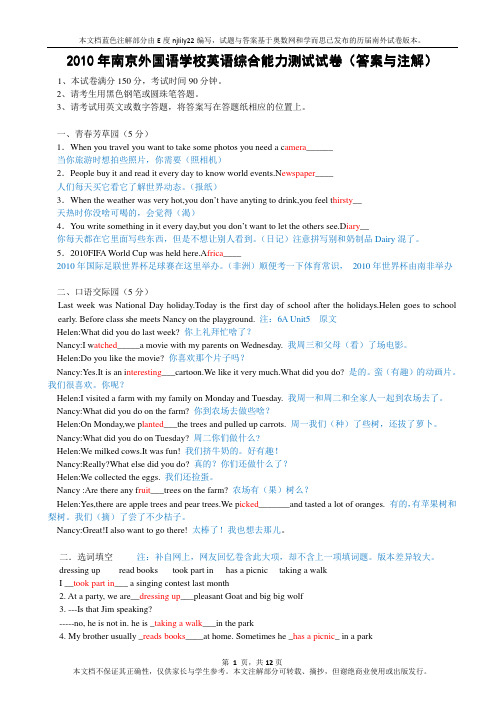

2010年南京外国语英语综合能力测试卷_答案注解

2010年南京外国语学校英语综合能力测试试卷)与注解注解)年南京外国语学校英语综合能力测试试卷((答案答案与1、本试卷满分150分,考试时间90分钟。

2、请考生用黑色钢笔或圆珠笔答题。

3、请考试用英文或数字答题,将答案写在答题纸相应的位置上。

一、青春芳草园(5分)1.When you travel you want to take some photos you need a c amera______当你旅游时想拍些照片,你需要(照相机)2.People buy it and read it every day to know world events.N ewspaper____人们每天买它看它了解世界动态。

(报纸)3.When the weather was very hot,you don’t have anyting to drink,you feel t hirsty__天热时你没啥可喝的,会觉得(渴)4.You write something in it every day,but you don’t want to let the others see.D iary__你每天都在它里面写些东西,但是不想让别人看到。

(日记)注意拼写别和奶制品Dairy混了。

5.2010FIFA World Cup was held here.A frica____2010年国际足联世界杯足球赛在这里举办。

(非洲)顺便考一下体育常识,2010年世界杯由南非举办二、口语交际园(5分)Last week was National Day holiday.Today is the first day of school after the holidays.Helen goes to school early. Before class she meets Nancy on the playground. 注:6A Unit5 原文Helen:What did you do last week? 你上礼拜忙啥了?Nancy:I w atched_____a movie with my parents on Wednesday. 我周三和父母(看)了场电影。

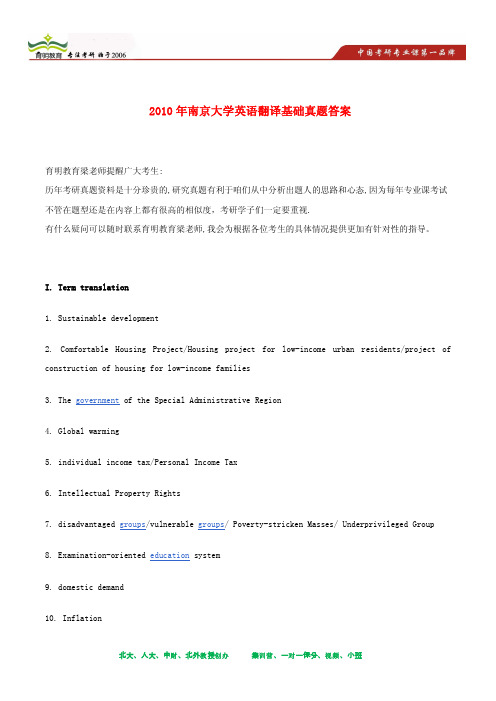

2010年南京大学英语翻译基础考研真题及其答案解析

财教创办北大、人大、中、北外授 训营对视频集、一一保分、、小班

2010年南京大学英语翻译基础真题答案

育明教育梁老师提醒广大考生:

历年考研真题资料是十分珍贵的,研究真题有利于咱们从中分析出题人的思路和心态,因为每年专业课考试不管在题型还是在内容上都有很高的相似度,考研学子们一定要重视.

有什么疑问可以随时联系育明教育梁老师,我会为根据各位考生的具体情况提供更加有针对性的指导。

I. Term translation

1. Sustainable development

2. Comfortable Housing Project/Housing project for low-income urban residents/project of construction of housing for low-income families

3. The government of the Special Administrative Region

4. Global warming

5. individual income tax/Personal Income Tax

6. Intellectual Property Rights

7. disadvantaged groups /vulnerable groups / Poverty-stricken Masses/ Underprivileged Group

8. Examination-oriented education system

9. domestic demand

10. Inflation。

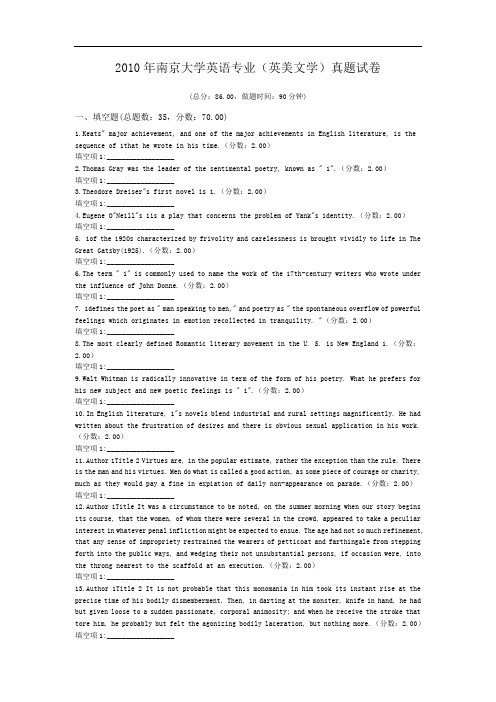

2010年南京大学英语专业(英美文学)真题试卷.doc

2010年南京大学英语专业(英美文学)真题试卷(总分:86.00,做题时间:90分钟)一、填空题(总题数:35,分数:70.00)1.Keats" major achievement, and one of the major achievements in English literature, is the sequence of 1that he wrote in his time.(分数:2.00)填空项1:__________________2.Thomas Gray was the leader of the sentimental poetry, known as " 1".(分数:2.00)填空项1:__________________3.Theodore Dreiser"s first novel is 1.(分数:2.00)填空项1:__________________4.Eugene O"Neill"s 1is a play that concerns the problem of Yank"s identity.(分数:2.00)填空项1:__________________5. 1of the 1920s characterized by frivolity and carelessness is brought vividly to life in The Great Gatsby(1925).(分数:2.00)填空项1:__________________6.The term " 1" is commonly used to name the work of the 17th-century writers who wrote under the influence of John Donne.(分数:2.00)填空项1:__________________7. 1defines the poet as " man speaking to men," and poetry as " the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings which originates in emotion recollected in tranquility. "(分数:2.00)填空项1:__________________8.The most clearly defined Romantic literary movement in the U. S. is New England 1.(分数:2.00)填空项1:__________________9.Walt Whitman is radically innovative in term of the form of his poetry. What he prefers for his new subject and new poetic feelings is " 1".(分数:2.00)填空项1:__________________10.In English literature, 1"s novels blend industrial and rural settings magnificently. He had written about the frustration of desires and there is obvious sexual application in his work.(分数:2.00)填空项1:__________________11.Author 1Title 2 Virtues are, in the popular estimate, rather the exception than the rule. There is the man and his virtues. Men do what is called a good action, as some piece of courage or charity, much as they would pay a fine in expiation of daily non-appearance on parade.(分数:2.00)填空项1:__________________12.Author 1Title It was a circumstance to be noted, on the summer morning when our story begins its course, that the women, of whom there were several in the crowd, appeared to take a peculiar interest in whatever penal infliction might be expected to ensue. The age had not so much refinement, that any sense of impropriety restrained the wearers of petticoat and farthingale from stepping forth into the public ways, and wedging their not unsubstantial persons, if occasion were, into the throng nearest to the scaffold at an execution.(分数:2.00)填空项1:__________________13.Author 1Title 2 It is not probable that this monomania in him took its instant rise at the precise time of his bodily dismemberment. Then, in darting at the monster, knife in hand, he had but given loose to a sudden passionate, corporal animosity; and when he receive the stroke that tore him, he probably but felt the agonizing bodily laceration, but nothing more.(分数:2.00)填空项1:__________________14.Author 1Title 2 What the hammer? What the chain? In what furnace was thy brain?What the anvil? What dread grasp Dare its deadly terrors clasp?(分数:2.00)填空项1:__________________15.Author 1Title 2 And on that cheek, and o"er that brow, So soft, so calm, yet eloquent,The smiles that win, the tints that glow, But tell of days in goodness spent, A mind at peace with all below, A heart whose love is innocent!(分数:2.00)填空项1:__________________16.Author 1Title 2 If only she hadn"t been that robust woman but a woman, in her middle years, with an incurable complaint of the heart. Then of course it wouldn"t have been terrible or even difficult to have made that decision that night, it wouldn"t even have been the source for ever afterwards of confusion, mystery and remorse.(分数:2.00)填空项1:__________________17.Author 1Title 2 My little horse must think it queer To stop without a farmhouse near, Between the woods and frozen lake The darkest evening of the year.(分数:2.00)填空项1:__________________18.Author 1Title 2 In the day time the street was dusty, but at night the dew settled the dust and the old man liked to sit late because he was deaf and now at night it was quiet and he felt the difference. The two waiters inside the cafe knew that the old man was a little drunk, and while he was a good client they knew that if he became too drunk he would leave without paying, so they kept watch on him.(分数:2.00)填空项1:__________________19.Author 1Title 2 But oh! that deep romantic chasm which slanted Down the green hill athwarta cedarn cover! A savage place! as holy and enchanted As e"er beneath a waning moon was haunted By woman wailing for her demon-lover!(分数:2.00)填空项1:__________________20.Author 1Title 2 Mr. Bennet was so odd a mixture of quick parts, sarcastic humour, reserve, and caprice, that the experience of three and twenty years had been insufficient to make his wife understand his character. Her mind was less difficult to develop. She was a woman of mean understanding, little information, and uncertain temper.(分数:2.00)填空项1:__________________21.Author 1Title 2 " Every one asks me what I " think" of everything" said Spencer Brydon; " andI make answer as I can—begging or dodging the question, putting them off with any nonsense. It wouldn"t matter to any of them really, " he went on, " for, even were it possible to meet in that stand-and-deliver way so silly a demand on so big a subject, my " thoughts" would still be almost altogether about something that concerns only myself. "(分数:2.00)填空项1:__________________22.Author 1Title 2 My Captain does not answer, his lips are pale and still, My father does not feel my arm, he has no pulse nor will, The ship is anchor"d safe and sound, its voyage closed and done, From fearful trip the victor ship comes in with object won;(分数:2.00)填空项1:__________________23.Author 1Title 2 In fairness to Charles it must be said that he sent to find Sam before he left the White Lion. But the servant was not in the taproom or the stables. Charles guessed indeed where he was. He could not send there; and thus he left Lyme without seeing him again. He got into his four-wheeler in the yard, and promptly drew down the blinds.(分数:2.00)填空项1:__________________24.Author 1Title 2 I found Simon Wheeler dozing comfortably by the bar-room stove of the old, dilapidated tavern in the ancient mining camp of Angel"s, and I noticed that he was fat and bald-headed, and had an expression of winning gentleness and simplicity upon his tranquil countenance. He roused up and gave me good-day.(分数:2.00)填空项1:__________________25.Author 1Title 2 Yossarian let his eyes fall closed and hoped they would think he was unconscious. "He"s fainted," he heard a doctor say. "Can"t we treat him now before it"s too late? He really might die. " "All right, take him. I hope the bastard does die. "(分数:2.00)填空项1:__________________26.Author 1Title 2 I can give you that historical bird"s eye view. But I cannot explain the mystery of Leonard Side"s inheritance. Most of us know the parents or grandparents we come from. But we go back and back, forever; we go back all of us to the very beginning; in our blood and bone and brain we carry the memories of thousands of beings.(分数:2.00)填空项1:__________________27.Author 1Title 2 The store in which the Justice of the Peace"s court was sitting smelled of cheese. The boy, crouched on his nail keg at the back of the crowded room, knew he smelled cheese, and more: from where he sat could see the ranked shelves close-packed with the solid, squat, dynamic shapes of tin cans whose labels his stomach read, not from the lettering which meant nothing to his mind...(分数:2.00)填空项1:__________________28.Author 1Title 2 My mother danced all night and Roberta"s was sick. That"s why we were taken to St. Bonny"s. People want to put their arms around you when you tell them you were in a shelter, but it really wasn"t bad. No big long room with one hundred beds like Bellevue.(分数:2.00)填空项1:__________________29.Author 1Title 2 He had rolled a handkerchief round his head, and his face was set and lowering in his sleep. But he was asleep, and quietly too, though he had a pistol lying on the pillow. Assured of this, I softly removed the key to the outside of this door, and turned it on him before I again sat down by the fire. Gradually I slipped from the chair and lay on the floor . When I awoke, without having parted in my sleep with the perception of my wretchedness, the clocks of the Eastward churches were striking five, the candles were wasted out, the fire was dead, and the wind and rain intensified the thick black darkness.(分数:2.00)填空项1:__________________30.Author 1Title 2 He felt that his luck was better than usual today. When he had reported for work that morning he had expected to be shut up in the relief office at a clerk"s job, for he had been hired downtown as a clerk, and he was glad to have, instead, the freedom of the streets and welcomed, at least at first, the vigor of the cold and even the blowing of the hard wind. But on the other hand he was not getting on with the distribution of the checks.(分数:2.00)填空项1:__________________31.Author 1Title 2 Three men were at work on the roof, where the leads got so hot they had the idea of throwing water on to cool them. But the water steamed, then sizzled; and they make jokes about getting an egg from some woman in the flats under the flats under them, to poach it for their dinner.(分数:2.00)填空项1:__________________32.Author 1Title 2 The three women sat in the little room, imagined not remembered. Veronica detected in her mother"s cream-coloured dress just a touch of awkwardness, her grandmother"s ineptness at a trade for which she was not wholly suited, a shoulder out of true, a cuff awry, as so many buttons and cuffs and waistbands had been during the making-do in the time of austerity.(分数:2.00)填空项1:__________________33.Author 1Title 2 Unmarried men are best friends, best masters, best servants, but not always best subjects, for they are light to run away,and almost all fugitives are of that condition.(分数:2.00)填空项1:__________________34.Author 1Title 2 So long as men can breathe or eyes can see, So long lives this, and this gives life to thee.(分数:2.00)填空项1:__________________35.Author 1Title 2 Spite, spite, is the word of your undoing! And when you"re down and out, remember what did it. When you"re rotting somewhere beside the railroad tracks, remember, and don"t you dare blame it on me!(分数:2.00)填空项1:__________________二、问答题(总题数:6,分数:12.00)36.Briefly state the main ideas of Benjamin Franklin"s The Autobiography and give your comments on them.(分数:2.00)__________________________________________________________________________________________ 37.What are the qualities that Granny Weatherall has? In what way do such qualities help her live successfully?(分数:2.00)__________________________________________________________________________________________ 38.What does "the green light" symbolize in The Great Gatsby? Does it exist in reality? Explain your answer.(分数:2.00)__________________________________________________________________________________________ 39.What does T. S. Eliot"s idea of "an objective of correlative" mean to you?(分数:2.00)__________________________________________________________________________________________ 40.What does Virginia Woolf use to present the life of the titled character in her Mrs. Dalloway?(分数:2.00)__________________________________________________________________________________________ 41.What do you find admirable in Robinson Crusoe? Discuss briefly some of his traits.(分数:2.00)__________________________________________________________________________________________三、评论题(总题数:1,分数:2.00)pare Grief with Tears, Idle Tears, commenting particularly on the treatment of their themes.(30 points)1. GriefBy Elizabeth Barrett BrowningI tell you hopeless grief is passionless;That only men incredulous of despair,Half-taught in anguish, through the midnight airBeat upward to God"s throne in loud accessOf shrieking and reproach. Full desertnessIn souls, as countries, lieth silent-bareUnder the blanching, vertical eye-glareOf the absolute heavens. Deep-hearted man, expressGrief for thy dead in silence like to death:Most like a monumental statue setIn everlasting watch and moveless woeTill itself crumble to the dust beneath.Touch it; the marble eyelids are not wet—If it could weep, it could arise and go.2. Tears, Idle TearsBy Alfred, Lord TennysonTears, idle tears. I know not what they mean,Tears from the depth of some divine despairRise in the heart and gather to the eyes.In looking on the happy Autumn-fields.And thinking of the days that are no more.Fresh as the first beam glittering on a sail.That brings our friends up from the underworld,Sad as the last which reddens over oneThat sinks with all we love below the verge;So sad, so fresh, the days that are no more.Ah, sad and strange as in dark summer dawnsThe earliest pipe of half-awakened birdsTo dying ears, when unto dying eyesThe casement slowly grows a glimmering square;So sad, so strange, the days that are no more.Dear as remembered kisses after death, And sweet as those by hopeless fancy feignedOn lips that are for others; deep as love, Deep as first love, and wild with all regret; O Death in Life, the days that are no more!(分数:2.00)__________________________________________________________________________________________ 作文43.Write a critical essay on the following topic.(30 points)Modernism is a reaction against realism. Discuss the features of modernism and illustrate your point with examples.(分数:2.00)__________________________________________________________________________________________。

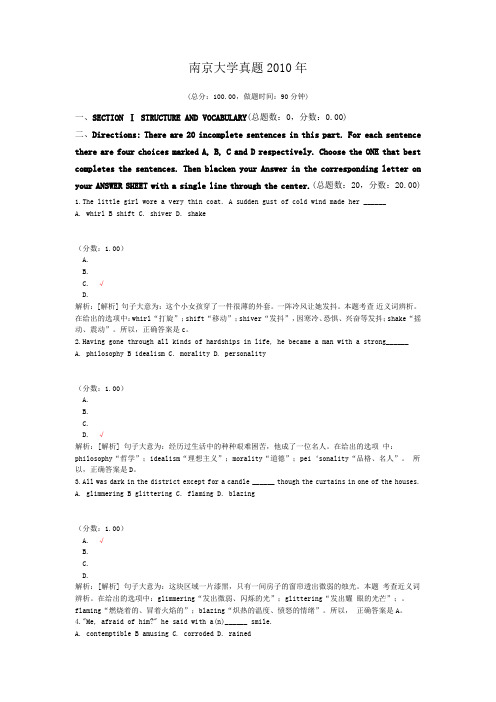

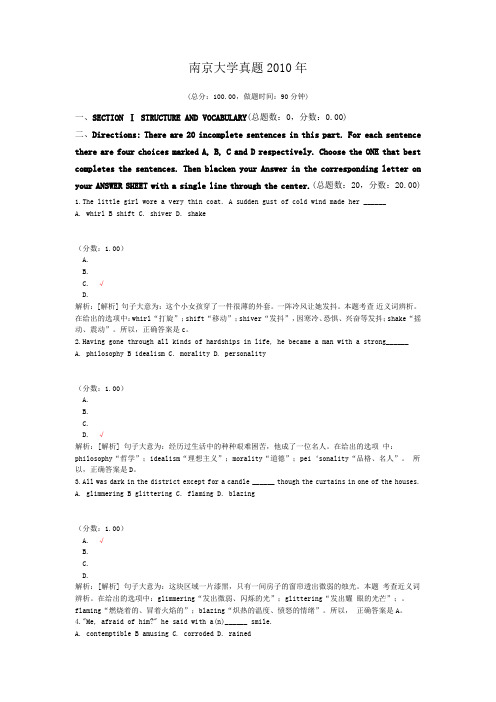

南京大学真题2010年

南京大学真题2010年(总分:100.00,做题时间:90分钟)一、SECTION Ⅰ STRUCTURE AND VOCABULARY(总题数:0,分数:0.00)二、Directions: There are 20 incomplete sentences in this part. For each sentence there are four choices marked A, B, C and D respectively. Choose the ONE that best completes the sentences. Then blacken your Answer in the corresponding letter on your ANSWER SHEET with a single line through the center.(总题数:20,分数:20.00)1.The little girl wore a very thin coat. A sudden gust of cold wind made her ______A. whirl B shift C. shiver D. shake(分数:1.00)A.B.C. √D.解析:[解析] 句子大意为:这个小女孩穿了一件很薄的外套。

一阵冷风让她发抖。

本题考查近义词辨析。

在给出的选项中:whirl“打旋”;shift“移动”;shiver“发抖”,因寒冷、恐惧、兴奋等发抖;shake“摇动、震动”。

所以,正确答案是c。

2.Having gone through all kinds of hardships in life, he became a man with a strong______A. philosophy B idealism C. morality D. personality(分数:1.00)A.B.C.D. √解析:[解析] 句子大意为:经历过生活中的种种艰难困苦,他成了一位名人。

2010年普通高等学校招生全国统一考试英语江苏卷,附答案

2010年普通高等学校招生全国统一考试英语(江苏卷)第一部分听力(共两节,满分30分)1、What will Dorothy do on the weekend?A Go out with her friendB work on her paperC Make some plans2、What was the normal price of the T-shirt?A $15B $30C $503、What has the woman decided to do on Sunday afternoon?A To attend a weddingB To visit an exhibitionC To meet a friend4、When does the bank close on Saturday?A AT 1:00 pmB AT 3:00 pmC AT 4:00 pm5、where are the speakers?A In a storeB In a classroomC At a hotel第二节(共15小题;每小题1.5分,满分22.5分)w_w w. k#s5_u.c o*m6 What do we know about Nora?A She prefers a room of ownB She likes to work with other girlsC She lives near the city center7、What is good about the flat?A It has a large sitting roomB It has good furnitureC It has a big kitchen听第七段材料,回答第8、9题。

8.where has Barbara been?A. MilanB. Florence.C. Rome.9 .What has Barbara got in her suitcase?A . Shoes. B. Stones. C. Books.听第8段材料,回答第10至12题。

2010江苏专转本英语真题

2010年江苏专转本英语真题2010年江苏省普通高校“专转本”统一考试大学英语本试卷分第I卷(客观题)和第II卷(主观题)两部分。

满分150分。

考试时间120分钟。

卷中未注明作答对象的试题为英语类和非英语类学生共同作答的试题,注明作答对象的试题按规定作答。

第Ⅰ卷Part ⅠReading Comprehension (共40分)Directions: There are 4 passages in this part. Each passage is followed by some questions or unfinished statements. For each of them there are 4 choices marked A, B, C and D. You should decide on the best choice and mark the corresponding letter on the Answer Sheet with a single line through the center.Passage OneQuestions 1 to 5 are based on the following passage.Sometimes you’ll hear people say that you can’t love others until you love yourself. Sometimes you’ll hear people say that you can’t expect someone else to love you until you love yourself. Either way, you’ve got to love yourself first and this can be tricky. Sure we all know that we’re the people of our parents’ eyes, and that our Grandmas think we are great talents and our uncle Roberts think that we will go to the Olympics, but sometimes it’s a lot harder to think such nic e thoughts about ourselves. If you find that believing in yourself is a challenge, it is time you built a positive self-image and learn to love yourself.Self-image is your own mind’s picture of yourself. This image includes the way you look, the way you act, the way you talk and the way you think. Interestingly, our self-images are often quite different from the images others hold about us. Unfortunately, most of these images are more negative than they should be, thus changing the way you think about yourself is the key to changing your self-image and your whole world.The best way to defeat a passive self-image is to step back and decide to stress your successes. That is, make a list if you need to, but write down all of the great things you do everyday. Don’t allow doubts to occur in it.It very well might be that you are experiencing a negative self-image because you can’t move past one flaw or weakness that you see about yourself. Well, roll up your sleeves and make a change of it as your primary task. If you think you are silly because you aren’t good at math. Find a tutor. If you think you are weak because you can’t run a mile, get to the track and practice. If you think you are dull because you don’t wear the latest trends, buy a few new clothes.The best way to get rid of a negative self-image is to realize that your image is far from objective and to actively convince yourself of your positive qualities. Changing the way you think and working on those you need to improve will go a long way towards promoting a positive self-image. When you can pat your self on the back, you’ll know you’re well on your way.1. You need to build a positive self-image when you _______.A.dare to challenge yourself B. feel it hard to change yourselfC. are unconfident about yourselfD. have a high opinion of yourself2. According to the passage, our self-images________.A. have positive effectsB. are probably untrueC. are often changeableD. have different functions3. How should you change your self-image according to the passage?A. Keep a different image of others.B. Make your life successfulC. Understand your own worldD. Change the way you think4. What is the passage mainly about?A. How to prepare for your successB. How to face challenges in your lifeC. How to build a positive self-imageD. How to develop your good qualities5. Who are the intended readers of the passage?A. parentsB. AdolescentsC. educatorsD. people in generalPassage 2Questions 6 to 10 are based on the following passage.Do you want to live with a strong sense of peacefulness, happiness, goodness, and self-respect? The coll ection of happiness actions broadly categorized as “honor” helps you create this life of good feelings.Here’s an example to show how honorable actions create happiness.Say a store clerk fails to charge us for an item. If we keep silent and profit fro m the clerk’s mistake, we would drive home with a sense of sneaky excitement. Later we might tell our family or friends about our good fortune. On the other hand, if we tell the clerk about the uncharged item, the clerk would be grateful and thank us for our honesty. We would leave the store with a quite sense of honor that we might never share with another soul.Then, what is it to do with our sense of happiness?In the first case, where we don’t tell the clerk, a couple of things would happen. Deep down inside we would know ourselves as a type of thief. In the process, we would lose some peace of mind and self-respect. We would also demonstrate that we cannot be trusted, since we advertise our dishonor by telling our family and friends. We damage our own reputations by telling others. In contrast, bringing the error to the clerk’s attention causes different things to happen. Immediately, the clerk knows us to be honorable. Upon leaving the store, we feel honorable and our internal rewards of goodness and a sense of nobility.There is a beautiful positive cycle that is created by living a life of honorable actions. Honorable thoughts lead to honorable actions. Honorable actions lead us to a happier experience. And it is easy to think and act honorably again when we are happy. While the positive cycle can be difficult to start, once it’s started, it’s easy to continue. Keeping on doing good deeds brings us peace of mind which is important for our happiness.6. According to the passage, the positive action in the example contributes to our ___________.A. self-respectB. financial rewardsC. advertising abilityD. friendly relationship7. The author thinks that keeping silent about the uncharged item is equal to _____.A. lyingB. stealingC. cheatingD. advertising8. The phrase “bringing the error to the clerk’s attention” means_______.A. telling the truth to the clerkB. offering advice to the clerkC. asking the clerk to be more attentiveD. reminding the clerk of the charged item9. How will we feel if we let the clerk know the mistake?A. We’ll be very excitedB. We’ll feel unfortunateC. We’ll have a sense of humorD. We’ll feel sorry for the clerk10. Which of the following can be the best title of this passage?A. How to live truthfullyB. Importance of peacefulnessC. Ways of gaining self-respectD. Happiness through honorablePassage 3Questions 11 to 15 are based on the following passage.Sesame Street has been called “the longest street in the world”. That is because the television program by that name can now be seen in so many parts of the world. That program became one of America’s exports soon after it went on the air in New York in 1969.In the United States more than 6 million children watch the program regularly. The viewers include more than half of the nation’s pre-school children. Although some educators object to certain elements in the program, parents praise it highly. Many teachers also consider it a great help, though some teachers find that problems arise when first graders who have learned from “Sesame Street” are in the same class with children who have not watched the program.The program uses songs, stories, jokes and pictures to give children a basic understanding of numbers, letters and human relationships. Tests have shown that children have benefited from watching “Sesame Street”. Those who watch five times a week learn more than the occasional viewers. In the United States the program is shown at different times during the week in order to increase the number of children who can watch it regularly.Why has “Sesame Street” been so much more successful than other children’s shows? Many reasons have been suggested. People mention the educational theories of its creators, the support by the government and private businesses, and the skillful use of a variety of TV tricks. Perhaps an equally important reason is that mothers watch “Sesame Street” along with their children. This is partly because famous adult stars often appear on “Sesame Street”. But the best reason for the success of the program may be that it makes every child watching it feel able to learn. The child finds himself learning, and he wants to learn more.11. Why has Sesame Street been called “the longest street in the world”?A. the program has been shown ever since 1969.B. the program became one of America’s major exports soon after it appeared on TVC. the program is now being watched in most parts of the world.D. the program is made in the longest street in New York.12. Some educators are critical of the program because________.A. they don’t think it fit for children in every respectB. it takes the children too much time to watch itC. it causes problems between children who watched it and those who have notD. some parents attach too much importance to it13. So many children in the United States watch the program because______.A. it uses songs, stories and jokes to give them basic knowledgeB. it is arranged for most children to watch it regularlyC. tests have shown that it is beneficial to themD. both A and B14. Mothers often watch the program along with their children because______A. they enjoy the program as much as their childrenB. they find their children have benefited from watching the programC. they are attracted by some famous adult stars on the showD. they can learn some educational theories from the program15. What is the most important reason for the success of the program according to the author?A. the creators have good educational theories in making the programB. the young viewers find they can learn something from it.C. famous adult stars often appear in the programD. It gets support from the government and private businessPassage 4Questions 16 to 20 are based on the following passage.You will have no difficulty in making contact with the agent. As you enter his office, you will be greeted immediately and politely asked what you are looking for. The Estate Agent’s negotiator-as he is called-will probably check that you really know your financial position. No harm in that, but you can always tell him that you have confirmed the position with the XYZ Building Society. He will accept that.He will show you the details of a whole range of properties; many of them are not really what you are looking for at all. That does not matter. Far better turn then down than risk missing the right one.The printed details he will give you are called “particulars”. Over the years, a whole language has grown up, solely for use in Agent’s pa rticulars. It is flowery, ornate and, providing you read it carefully and discount the adjectives, it can be very accurate and helpful.Since the passing of the Trades Description Act, any trader trying to sell something has had to be very careful as to what they say about it. Estate Agents have, by now, become very competent at going as far as they dare. For instance, it is quite acceptable to say “delightfully” situated. That is an expression of his opinion. You many not agree, but he might like the idea of living next to the gasworks. If, on the other hand, he says that the house has five bedrooms when, in fact, it has only two, that is a misstatement of fact and is an offence. This has made Estate Agents and others for that matter rather more careful.Basically, all that you need to know about a house is : how many bedrooms it has; an indication of their size; whether the house has a garage; whether there is a garden and whether it is at the back or the front of the house; whether its semi-detached of terraced.16. The Estate Agent’s negotiator will ________.A. want all details of your financial circumstancesB. want to satisfy himself that you understand the financial implications of buying a house.C. check your financial position with the XYZ Building SocietyD. accept any statement you make about your financial position17. The author believes ________.A. it is better to be given information about too many properties than too fewB. you should only look at details of properties of the kind you have decided to buy.C. the agent will only show you the details of properties you have in mind.D. it doesn’t matter if you miss a few properties you may be interested in.18. The adjectives in Agent’s particulars are ______.A. accurateB. helpfulC. both accurateD. safe to ignore19. The Trades Description Act applies to ___________.A. house agents onlyB. most estate agentsC. any traderD. buyer of houses20. The phrase “going as far as they dare” pro bably means______.A. covering as wide an area as possibleB. selling houses as far from the estate agent’s housesC. telling lies about properties if nobody is likely to find out about it.D. trying every possible means to make the description of houses sound attractivePart ⅡV ocabulary and StructureDirections: In this part there are forty incomplete sentences. Each sentence is followed by four choices. Choose the one that best completes the sentence and then mark your answer on the Answer Sheet.21. Scientists will have to _____ new methods of increasing the world’s food supply in order to solve the problem of famine in some places.A. come up forB. come down withC. com down toD. come up with22.I’d like to rent a house, modern, comfortable and ______in a quiet a nd safe neighborhood.A. all in allB. above allC. after allD. over all23. In order to expose corruption, they have decided to set up a special team to ____the company’s accounts.A. search forB. work outC. look intoD. sum up24. Some people would like to do shopping on Sundays since they expect to pick up a lot of wonderful _____ in the markets.A. batteriesB. basketsC. barrelsD. bargains25. The residents living in these apartments have free ____ to the swimming pool, the gym and other facilities.A. excessB. excursionC. accessD. recreation26.Reporters and photographers alike took great _____at the rude way the actors behaved during the interview.A. annoyanceB. offenceC. resentmentD. irritation27. Nothing healthful should be omitted from the meal of a child because of a ___ dislike.A. provedB. supposedC. consideredD. related28. I’d like to ____ this old car f or a new model but I am afraid I cannot afford it.A. exchangeB. convertedC. replaceD. substitute29. She said she liked dancing but was not in the ______for it just then when it was so noisy in the hall.A. mannerB. intentionC. moodD. desire30. He was _____ admittance to the concert hall for not being properly dressed.A. rejectedB. deniedC. withheldD. deprived31. Most people tend to ______ a pounding heart and sweating palms with the experience of emotion.A. classifyB. identifyC. satisfyD. modify32. The company _____ many fine promises to the engineer in order to get him to work for them.A. held upB. held onC. held outD. held onto33. _____the tragic news about their president, they have cancelled the 4th of July celebration.A. In the course ofB. In spite ofC. In the event ofD. In the light of34. The worker’ demands are _______, they are asking for only a smal l increase in their wages.A. particularB. moderateC. intermediateD. numerous35. Our explanation seemed only to have _____ his confusion. He was totally at a loss as to what to say.A. brought upB. added toC. worked outD. directed at36. With a standard bulb, only 5% of the electricity is ______ to light-the rest is wasted away as heat.A. compressedB. conformedC. convertedD. confined37. Modern technology has placed ______ every kind of music, from virtually every period in history and every corner of the globe.A. at our requestB. at our disposalC. in our presenceD. in our sight38. Much has been written on the virtues of natural childbirth, but little research has been done to ___ these virtues.A. confirmB. consultC. confessD. convey39. Plastic bags are useful for holding many kinds of food ______their cleanness, toughness and low cost.A. by virtue ofB. at sight ofC. by means ofD. by way of40. I am trying to think of his mind, but my mind goes completely _____i must be slipping.A. bareB. blankC. hollowD. vacant41. _____ in the regulations that you should not tell other people the password of your email account.A. what is requiredB. what requiresC. It is requiredD. It requires42. It is generally believed that gardening is ______it is a science.A. an art much asB. much an art asC. as an art much asD. as much an art as43. The indoor swimming pool seems to be great more luxurious than ______.A. is necessaryB. being necessaryC. to be necessaryD. it is necessary44. He ______ English for 8 years by the time he graduates from the university next year.A. will learnB. will be learningC. will have learntD. will have been learnt.45. It was not until the sub prime loan crisis ______ great damage to the American financial system that Americans ______the severity of the situation.A. caused; realizedB. had caused; realizedC. caused; had realizedD. was causing; had realized46. The police think your brother John stole the diamond in the museum yesterday evening.Oh? But he stayed with me at home the whole evening; he ___ the museum.A. must have been toB. needn’t have been toC. should have been toD. couldn’t have been to47. _______ the meeting himself gave his supporters a great deal of encouragement.A. The president will attendB. The president to attendC. The president attendedD. The president’s attending48. Everything _____into consideration, the candidates ought to have another chance.A. is takenB. takenC. to be takenD. taking49. _______from heart trouble for years, Professor White has to take some medicine with him wherever he goes.A. SufferedB. SufferingC. Having sufferedD. Being suffered50. The concert will be broadcasted live to a worldwide television audience_____thousand millionA. estimatingB. estimatedC. estimatesD. having estimated51. About half of the students expected there ______more reviewing classes before the final exams.A. isB. beingC. to beD. have been52. _____ made the school proud was _______more than 90% of the students had been admitted to key universities.A. What; becauseB. What; thatC. That; whatD. That; because53. Information has been released ______ more middle school graduates will be admitted into universities this year.A. whileB. thatC. whenD. as54. He is the only one of the students who ______ a winner of scholarship for three years.A. isB. areC. have beenD. has been55. What’s that newly-built building?______ the students have out-of-class activities, such as drawing and singing.A. It is the building thatB. That’s whereC. It is in whichD. The building that56.With a large amount of work_____ the chief manager couldn’t spare time for a holiday.A. remained to be doneB. remaining to doC. remained to doD. remaining to be done57. Why! I have nothing to confess, ______you want me to say?A. What is it thatB. what it is thatC. How is it thatD. How is it that58. David has made great progress recently.__________, and __________________.A. So he has, so you haveB. So he has; so have youC. So has he; so you haveD. So has he; so you have59. It is universally known that microscopes make small things appear larger than _____.A. really areB. are reallyC. are they reallyD. they really are60. Tom, _______, but your TV is going too loud.Oh, I’m sorry. I will turn it down right now.A. I’d like to talk with youB. I’m really tired of thisC. I hate to say thisD. I need your helpPart ⅢClozeDirections: There are 20 blanks in the following passages. For each bank there are 4 choices marked A, B, C and D. You chose the ONE that best fits into the passage, the corresponding letter on the Answer Sheet with a single line through the center.The eyes are the most important (61) of human body that is used to (61) information. Eye contact is crucial for establishing rapport (63) others. The way we look at other people can (64) them know we are paying attention to (65) they are saying. We can also look at a person and gave the (66) we are not hearing a word. Probably all of us have been (67) of looking directly at someone and (68) hearing a word while he or she was talking (69) we were thinking aboutsomething totally (70) to what was being said.Eye contact allows you to (71) up visual clues about the other person; (72), the other person can pick up clues about you. Studies of the use of eye contact (73) communication indicate that we seek eye contact with others (74) we want to communicate with them. When we like them, when we are (75) toward them (as when two angry people (76) at each other). And when we want feedback from them. (77), we avoid eye contact when we want to (78) communication, when we dislike them, when we are (79) to deceiving them, and when we are (80) in what they have to say.61 A. unit B. part C. link D. section62 A. transfer B. translate C. transmit D. transport63 A. against B. with C. for D. to64 A. forbid B. allow C. permit D. let65 A. how B. which C. what D. that66 A. impression B. expression C. suggestion D. attention67 A. ignorant B. careless C. guilty D. innocent68 A. nor B. so C. not D. neither69 A. or B. unless C. why D. because70 A. related B. relevant C. unrelated D. indifferent71 A. tear B. pick C. size D. take72 A. likewise B. moreover C. otherwise D. therefore73 A. in B. about C. with D. of74 A. why B. where C. when D. what75 A. friendly B. hostile C. respectful D. mistrustful76 A. glance B. glare C. gaze D. stare77 A. Exactly B. Generally C. Conversely D. Interestingly78 A. hold B. establish C. avoid D. direct79 A. wanting B. tending C. forcing D. trying80 A. informed B. unconcerned C. uninterested D. unheard第Ⅱ卷(共50分)Part ⅣTranslationSection ADirections: Translate the following sentences into Chinese you may refer to the corresponding passages in Part ONE.81. The best way to get rid of a negative self-image is to realize that your image is far from objective and to actively convince yourself of your positive qualities.82. There is a beautiful positive cycle that is created by living a life of honorable actions Honorable thoughts lead to honorable actions. Honorable actions lead us to a happier existence.83. While the positive cycle can be difficult to start, once it’s started, it’s easy to continu e. Keeping on doing good deeds brings us peace of mind, which is important for your happiness.84. That is because television program by that name can not be seen in so many parts of the world.That program became one of American’s export soon after it went on the air in New York in 1969.85. For instance, it is quite acceptable to say “delightfully” situated. That is an expression of his opinion. You may not agree, but he might like the idea of living next to the gasworks.Section BDirections: translate the following sentences into English.86. 一个公司应该跟上市场的发展变化,这很重要。

2010年江苏省高考英语试卷