2010年湖南师范大学MTI翻译基础真题及出处

2010全国硕士研究生统考日语真题之翻译

2010全国硕士研究生统考日语真题之翻译2010年全国硕士研究生入学统一考试日语试题之翻译B.次の文章の下線のついた部分を中国語に訳しなさい。

(3点×5=15点)41、商品名、つまり商品を指示するだけのブランドには、価値は生じない。

消費者にとって、交換の対象は商品そのものであって、商品の名前は「問題の商品を、他の商品と区別する」とか、あるいは「その供給者はどこかを示すために識別する」だけの信号にすぎない。

その意味で、ブランドのこの効果を「識別効果」と呼んでおこう。

記号だから、それは別に符号でも数字でもかまわない。

42、しかし、一度、商品名そのものが独特の意味をもったメッセージを発することになれば、つまり、商品名がブランドとなれば、事態は一転する。

商品を実際に手にしたり目にしたりすることがない消費者でも、商品名を聞けばその商品のことがわかるというのだから、商品名が商品から独立し、自立した存在となっている。

43、商品名が知れわたること、あるいは商品名を通じてその商品の中身についての理解が消費者のあいだに浸透することは、商品名の価値にほかならない。

それは、商品名の「知名・理解効果」と呼んでいいだろう。

それだけで、広告宣伝のためのコストを節約できる。

44、「LV」や「シャネル(香奈儿)」のマークが入ったTシャツがそれなりの値段で売れる理由は、そうしたブランドが独自の意味世界という価値をもっているからである。

そうしたマークがつくことによって高くなった価格分は、その意味世界への入場料でもある。

45、言い換えると、ブランドが、その商品に特有の意味を付着させることによって、消費者の欲望を満足させ、独自の「意味世界」を創造するということである。

そうなれば、市場における他のブランド商品群との競争において優位性をつくったということになる。

以上是中公考研为大家准备整理的“2010全国硕士研究生统考日语真题之翻译”的相关内容。

2010年湖南大学英语翻译基础真题答案

2010年湖南大学英语翻译基础真题答案I.Term Translation1.Chinese to English1) three represents theory (The Party should always represent the development needs ofChina's advanced social productive forces, always represent the onward direction ofChina 's advanced culture, and always represent the fundamental interests the vastmajority of the people.2) Keep Up With the Times3) The ability of independent innovation4) Ruling the country by virtue5) scientific outlook (thinking) on development6) <名> mortgage slave, mortgage burden;a slave to one\'s mortgage抵押借款的奴隶7) issues concerning agriculture, countryside and farmers;Issues of agriculture, farmer andrural area8) pyramid selling9) service-oriented government10) Economical Housing. - Housing sold at low prices to low-income earners to get themaffordable shelters.;economical and practical property11) people oriented;people foremost12) subprime crisis13) construction of a clean and honest administration14) spiritual civilization -- intellectual and moral qualities; a civilization which is culturally andideologically advanced; a civilization with a high cultural and ideological level; cultural and ideological progress; advanced culture and ethics:Promote the daily progress of our culture level;促进精神文明raise the level of our cultural life; build a civilization with a high cultural and ideological level建设精神文明15) The rise of central China2. English to Chinese16) 外交关系正常化17) 劳资纠纷18) 不可再生资源19) 贫富差距20) 网络恐怖主义21) 泡沫经济22) 温室气体23) 智囊团24) 知识产权25) 石油换食品计划26) n. <医>炭疽(病);炭疽脓疱27) 太平洋带状地区rim: (圆形器皿的)边,缘,框;轮缘。

湖南师范大学外国语学院《880英美文学和中文作文》历年考研真题汇编

目 录2010年湖南师范大学外国语学院880英美文学和中文作文考研真题(回忆版)2009年湖南师范大学外国语学院880英美文学和中文作文考研真题2010年湖南师范大学外国语学院880英美文学和中文作文考研真题(回忆版)wm年翻南师密大学$种莫英艾季和中丈作文砌试原(回吹)待歌赏析格Chris-tina Hossciii的The Fir^l Pay戒剧廿选髭Tenasscc WiEliatn^的A Sireel Car Named Desire评论BlancheSummary也Suki的The Open Window,Jn|fl| i£f f_£个何期中攵什文是引用厂梁实秋的段才的作家.没有犬才的批评京.皖批神报雄止你以T比评•这个「•嘶写作变.2009年湖南师范大学外国语学院880英美文学和中文作文考研真题2009年全国硕瓦茹为莓£自命题科目试题册业务课代码:™业务课名祢:英美文学和中文作文考身购:J 笋必婀在答趣纸上。

财麻纸上不伽财改液:题"'领使典' 黑色嬲水或遍一酣备H }其他宅朝不结机I F 而篇|:二:看%;::3严帽询血电血尊%岫瞄& ■丽 r K Old E 壁liuhrciirs Io:投曲E 喀哄一7曲一腿网w —戒r 凡,尸倒"如尸如,初知 0 n 一一・第,页,共〃近/厂](k The term'lhe Yahoos"alludes to lhe novel,,A,Robinson Crusoe B.Mo"FktwigC.The Bartie时the BoohD.Gidlhw i Tra^H.J1L Representing the highest achicveirient in English pociry,the period has been •f1considered the second gre@l period in IZuglish literatUTC,second only to the Elizabelhanperiod.A.RojnamicB.NcoclassicC.Realisdc D,Smimental,「12_____is considered the falher of the hisEoris-al novel.urence SterneB.Walter Scat!C Daniel Ocfoe D.Henry『Fielding/:I3.____$cen as the English precursor of the psychological novel..A.Emily BronteB.George EliotC.Charlotte BronteD.Anne Brome*j】4is a series of novels about the frontier life of American sclIlers during,the Ji Westward movement.A.m Sketch BookB.7r h e Wessex SagaC.Life on the MississippiD.The Lenthe s tocking Tiilex厂15,The idea that"the Universe is composed of Naiurc and I hc SouF1is pul fbmard by^-^the author.A.0.Franklin B,Walt Whitman C,R.W.Emerson□.H.Thoreau[6,fi*Evcrjone possesses some evi I secrcf'is ihc subject mailer of_-•3A*u Young GQtHJman Brown1*&'"Rip van Winkle1C.WaldenD.Moby Dick17.Of the three great writers,is considered tlie champion of liicrars realism in ■^America,A.W.D r HowellsB.H.James C,Mark Twain D,$・L.Clemens/】SL____was considered America^unofficial Poet Laureate in the1940s,'A,C.Sandburg B.R.Frost C.E.E.Cummings D,W Stevens 619,As Thomas Hardy set his works against Wessex,____set his novels against the Yoknapata^vplia County,a fictional place in lhe Deep South of America.A.H+MelvitkB. E.HemingwayC.W.Faulkner l> F.S,八Fitzgerald/J20.____is the literary spokesman of the Jazz.Age.‘' A.F.S.Fitzgerald B.E.I lemingway C;Hart Crane LX G Steini l.Teli the names oFthe authors of the following literary^works.(10points)],Mrs.W tarreni-Profession 2.The Jungle回心3.The Forsyte Saga4,The Passage to India第之页.共/顶5.Flnwgum7.The American Scholar 9;The(Hass Menagerie 6.Lord Jim8.The R.d Budge of C ourage ID.The Airy Apeplete,with a proper word or phrase,each of(he following statements concerning English or American literature.<10points)1.In16U,King.fames Bible,or,came out to have a great infhienw On the English literary language and liieraiure.2."And enterprise of gre.u pith and moment,X With this regard,their currents I urn awry\ And lose the name of action:'These lines,I he hsi3lines of a solibquy,show thespeaker's,3._. a pioneer of the18th cenlury English novth is the founder of lhe epistolary novel.4.According to W.Woi'dsworth,poctrv'comes from F not from-----”5.哄your chimney I sweep,&in spot I sleep."This is a line from the collection of poems entitled M-6.“It is a[ruth universally acknowledged that a single man,吊possession of a&ood tontiEie,niust be in watii of a wife."The figure of speech叔usei!htre at the ver? beginning af a well-known novel,7.«]t is my spirit that addressed your spirit;just as if both had passed through the grave, and we stood al God's feet,equal-—as we are!”The speaker is-------■g r“Ail mean c^olism vanish如1become a______-1am nothing,t see all.The currents of the Universal Reing circulate through me;I am pan or particle of God"9.b'|cclcbraie myself,and sing myself And What1assume you shall assumeA For every atom belonging tome as good beiongi to you"This is lite first stanza ofW.Whitmaft'spoem.10.T.S.F.liofs famotis dMirine on poets and poetry is known as the-----theory.TV,Read the folU>wiiig£XMrpl「Em The Merchant of Venice by William Sliak4?spcare and write a short but coherent essay on Shyloek.(25points)SHYLOCK:He hath disgraced me,and hindered me half a miliion,laughed at my losses, moc ked at my gains,scorned my nation,thwarted my bargains,cooled my friends,heated inine enemies;and whai's his reason?I am a Jew;Hath not a Jew eyes?Hath not a Jew第3页.英〃更h.i讪,呻低dimtnsrons,心皿lions,pasions?Fed with theTi扁福「福而出(he same w.咿呜subject io the same rntanj,warmed and妙血d by M sama wiEcr丽summm as u Chri而a n ii-if>ou prick既血总响bkwf?IE“而赤“、,也洌n。

[考研类试卷]2012年湖南师范大学英语翻译基础真题试卷.doc

![[考研类试卷]2012年湖南师范大学英语翻译基础真题试卷.doc](https://img.taocdn.com/s3/m/eb93a54516fc700abb68fcf4.png)

[考研类试卷]2012年湖南师范大学英语翻译基础真题试卷英译汉1 Queensland2 Quebec3 Santa Claus4 Sir Walter Scott5 Stamp Tax6 Standard & Poor's7 Suez Canal8 Sydney9 Vancouver10 West Indies11 phonetics12 translation after sense13 Eurasia Land Bridge14 monetary integration15 Europe's sovereign-debt crisis汉译英16 载人航天17 行政问责18 公务接待费19 法人代表20 蜗居21 富二代22 工业“三废”23 潜规则24 发动机排量25 公民健康档案26 全球化27 增值税28 住房信贷政策29 颐和园30 法律硕士英译汉31 World food prices are pushing higher—the United Nations overall food index showsa 28. 3% annual increase, with cereals up 44. 1%—sparking concerns that a new food crisis may be emerging, just three years after the last one. Does this mean the world is running out of food?The quick answer is that the world does seem to be running low on cheap food. This supply shortage stems from the failure of governments and donors over nearly three decades to fund the basic agricultural research, investments in rural infrastructure, and training for smallholder farmers necessary to push out the productivity frontier.Until recently, world food crises have been relatively rare events—occurring about three times a century. The food crisis of 2007 ~2008, although scary at the time, was relatively mild by comparison. Prices for wheat, rice and maize—the staple foods that provide well over half the world population's energy intake directly and a good deal more indirectly via livestock products—rose 96. 7% between 2006 and 2008, not approaching the spikes in the mid-1970s when corrected for inflation. Yet here we are just a few years later, talking about food prices again.汉译英32 微笑,永远是微笑者个人的专利,它既不能租,又不能买;既不能借,又不能偷。

2010考研英语二 翻译题、参考答案和来源分析

2010考研英语二翻译题、参考答案和来源分析"Sustainability" has become a popular word these days, but to Ted Ning,the concept will always have personal meaning. Having endured a painful period of unsustainability in his own life made it clear to him that sustainability-oriented values must be expressed through every day action and choice.当今,―可持续性‖已经成为了一个流行的词语。

但是,对特德宁来说,他对这个词有着自身的体会。

在忍受了一段痛苦的、难以为续的生活之后,他清楚地认识到,以可持续发展为导向的生活价值必须通过日常的活动和做出的选择表现出来。

Ning recalls spending a confusing year in the late 1990s selling insurance. He'd been through the dot-com boom and burst and, desperate for a job, signed on with a Boulder agency.宁回忆了在上个世纪90年代末期的某一年,他卖保险,那是一种浑浑噩噩的生活。

在经历了网络经济的兴盛和衰败之后,他非常渴望得到一份工作,于是和一家博德的代理公司签了合约。

It didn't go well. "It was a really bad move because that's not my passion," says Ning, whose dilemma about the job translated, predictably, into a lack of sales. "I was miserable. I had so much anxiety that I would wake up in the middle of the night and stare at the ceiling. I had no money and needed the job. Everyone said,‖ Just wait, you'll turn the corner, give it some time.''事情进展不顺,―那的确是很糟糕的一种选择,因为那并非是我的激情所在,‖宁如是说。

湖南大学2010年翻译硕士考研真题及答案

湖南大学2010年翻译硕士考研真题及答案第一篇:湖南大学2010年翻译硕士考研真题及答案凯程考研辅导班,中国最权威的考研辅导机构湖南大学2010年翻译硕士考研真题及答案历年真题是最权威的,最直接了解各专业考研的复习资料,考生要重视和挖掘其潜在价值,尤其是现在正是冲刺复习阶段,模拟题和真题大家都要多练多总结,下面分享湖南大学2010年翻译硕士考研真题及答案,方便考生使用。

湖南大学2010年翻译硕士考研真题及答案I.Phrase Translation1)三个代表: Three Represents2)与时俱进: advance with the times;keep pace with the times3)自主创新能力:capacity for independent innovation;independent innovation capability4)以德治国:Rule the country by virtue;run the country by virtue5)科学发展观:Scientific Outlook on Development6)房奴:house slave;mortgage slave7)“三农”问题:issues concerning agriculture,countryside and farmers;issues of agriculture,farmer and rural area8)传销:pyramid selling;pyramid sales9)服务型政府:service-oriented government;Service Government10)经济适用房:affordable housing;economically affordable housing11)以人为本: people oriented;Put People First12)次贷危机: subprime mortgage crisis;subprime crisis13)廉政建设: construction of a clean and honest administration;clean government building14)精神文明: cultural and ideological progress15)中部崛起: rise of central china16)normalization of diplomatic relations: 外交关系正常化17)labor dispute: 劳动争议;劳资纠纷18)irrenewable energy:不可再生能源19)wealth gap: 贫富差距;贫富悬殊20)cyberterrorism: 网络恐怖主义21)bubble economy:泡沫经济22)greenhouse gases:温室气体;温室效应气体23)think tank:智囊团;智库24)intellectual property rights: 知识产权25)oil-for-food program: 石油换粮食计划;石油换食品计划26)anthrax: 炭疽,炭疽热27)Pacific Rim: 太平洋周边地区;环太平洋(地区);太平洋沿岸(地区)28)soft landing: 软着陆29)the carrot and the stick: 胡萝卜加大棒;威逼加利诱;软硬兼施30)multilateral negotiation: 多边谈判;多方协商II.Passage translation凯程考研辅导班,中国最权威的考研辅导机构Section A English to ChineseLawrence lived his relatively short life during a period of social and political upheaval.His experience as a student and a teacher would not have been possible had the Education Act of 1870 not established compulsory elementary schools for children of back grounds like his.The industrialism he hated, particularly the large-scale coal mining in areas like Notting hamshire, with the accompanying blight of surrounding countryside, was reaching a peak during his childhood and early manhood.World War I was a shock, followed by disillusionment , to many educated Europeans, who had believed that materialprogress, equated with the advance of civilization, had banished war wrence had never shared the near universal faith in material progress.His horror of the war, for reasons more personal, proved socially and politically prophetic — he saw the war as the beginning of the conformism , the assault on authentic individualism that has in fact characterized the twentieth century.Because Lawrence spent years in Italy during the fascist period, and because his “dream of leadership” often emerged in authoritarian statements or the invention of authoritarian figures , one of the many strands of adverse criticism woven around him during his life was a charge that he had fascist leanings.The charge is absurd, as insight into the essential core of the man — his hatred of conformism, insistence on singular passional being — reveals.However, it is true that Lawrence, like many artists who believe in the magic of words, sometimes expressed his yearnings for power in an idiom colored by the socialist, communist, and fascist language of the 1920s and 1930s.参考译文:劳伦斯比较短促的一生,正处在社会和政治大动荡的时期。

2013年湖南师范大学外国语学院357英语翻译基础考研真题及详解【圣才出品】

2013年湖南师范大学外国语学院357英语翻译基础考研真题及详解PART I TRANSLATION OF WORDS AND PHRASES (60 MIN)SECTION A ENGLISH TO CHINESE (15 POINTS)Translate the following words and phrases into Chinese. Write your translations on the answer sheet.1. BEC【答案】商务英语证书2. GPS【答案】全球定位系统3. HIV【答案】人类免疫缺陷病毒4. Melbourne【答案】墨尔本5. Semantics【答案】语义学6. overdue loan【答案】逾期贷款7. avian influenza【答案】禽流感8. Ph. D candidate【答案】博士生9. cease-fire agreement【答案】停火协议10. proactive fiscal policy【答案】积极的财政政策11. fixed exchange rate system 【答案】固定汇率制度12. qualified commercial insurer 【答案】合格的商业保险公司13. consultation on an equal footing 【答案】平等协商14. household and commercial lighting【答案】家庭和商业照明15. United Nations Security Council【答案】联合国安理会SECTION B CHINESE TO ENGLISH (15 POINTS)Translate the following words and phrases into English. Write your translations on the answer sheet.1. 《大学》【答案】the Great Learning2. 免费通过【答案】free passage3. 流动人口【答案】floating population4. 种子选手【答案】seeded player5. 共同富裕【答案】common prosperity6. 生态农业【答案】ecological agriculture7. 行政审批【答案】administrative examination and approval8. 农业特产税【答案】tax on special agricultural products9. 在职研究生【答案】on-the-job postgraduate10. 自然保护区【答案】natural reserve11. 学龄前儿童【答案】pre-school children12. 大规模裁员【答案】mass layoffs13. 工资集体合同【答案】Collective Contract on Salary14. 科技体制改革【答案】reform of the scientific and technological system15. 公共供暖系统【答案】public heating systemPART II TRANSLATION OF TEXTS (120 MIN)SECTION A ENGLISH TO CHINESE (60 POINTS)Most of the luxuries, and many of the so-called comforts of life, are not only not indispensable, but positive hindrances to the elevation of mankind. With respect to luxuries and comforts, the wisest have ever lived a more simple and meagre life than the poor. The ancient philosophers, Chinese, Hindoo, Persian, and Greek, were a class than which none has been poorer in outward riches, none so rich in inward. We know not much about them. It is remarkable that we know so much of them as we do. The same is true of the more modern reformers and benefactors of their race. None can be an impartial or wise observer of human life but from the vantage ground of what we should call voluntary poverty. Of a life ofluxury the fruit is luxury, whether in agriculture, or commerce, or literature, or art. There are nowadays professors of philosophy, but not philosophers. Yet it is admirable to profess because it was once admirable to live. To be a philosopher is not merely to have subtle thoughts, nor even to found a school, but so to love wisdom as to live according to its dictates, a life of simplicity, independence, magnanimity, and trust. It is to solve some of the problems of life, not only theoretically, but practically. The success of great scholars and thinkers is commonly a courtier-like success, not kingly, not manly. They make shift to live merely by conformity, practically as their fathers did, and are in no sense the progenitors of a noble race of men.【参考译文】大部分的奢侈品,大部分的所谓生活的舒适,非但没有必要,而且对人类进步大有妨碍。

2013年湖南师范大学翻译硕士(MTI)汉语写作与百科知识真题试卷

2013年湖南师范大学翻译硕士(MTI)汉语写作与百科知识真题试卷(总分:54.00,做题时间:90分钟)一、名词解释(总题数:25,分数:50.00)1.信息技术(分数:2.00)__________________________________________________________________________________________ 正确答案:(正确答案:信息技术:英译为Information Technology(缩写IT),是主要用于管理和处理信息所采用的各种技术的总称。

它主要是应用计算机科学和通信技术来设计、开发、安装和实施信息系统及应用软件。

)解析:2.经济软着陆(分数:2.00)__________________________________________________________________________________________ 正确答案:(正确答案:经济软着陆:是指国民经济的运行经过一段过度扩张之后,平稳地回落到适度增长区间。

“软着陆”是相对于“硬着陆”,即“大起大落”方式而言的。

)解析:3.空中交通管制(分数:2.00)__________________________________________________________________________________________ 正确答案:(正确答案:空中交通管制:利用通信、导航技术和监控手段对飞机飞行活动进行监视和控制,保证飞行安全和有秩序飞行。

在飞行航线的空域划分不同的管理空域,包括航路、飞行情报管理区、进近管理区、塔台管理区、等待空域管理区等,并按管理区不同使用不同的雷达设备。

)解析:4.蓝色农业(分数:2.00)__________________________________________________________________________________________ 正确答案:(正确答案:蓝色农业:指在水体中开展的海洋水产农牧化活动,具体来说,所有在近岸浅海海域、潮间带以及潮上带室内外水池水槽内开展的虾、贝、藻、鱼类的养殖业都包括在内。

湖南师范大学翻译理论与英汉互译2006-2009真题

湖南师范大学英汉互译方向的研究生入学考试真题(自主命题)2000-2002专业课分三门考,每门总分100分2003专业课分方向2004专业课不分方向综合考试(含汉语、语言学、文学、翻译)2005专业课分方向2006-2007综合知识(语言学、文学、翻译各占40分、中文作文30分)2008-2009英汉互译和语言学或文学知识2010 中文点评题,英译中(2篇),中译英(2篇)20061英译中I continued the labors of the village school as actively and faithfully as I could. It was truly hard work at first. Some time elasped before, with all my efforts, I could comprehend my scholars and their nature. Wholly untaught,with faculties quite inactive, they seemed to me hopelessly dull; and, at first sight, all dull alike; but I aoon found I was mistaken. There was a difference amongst them as amongst the educated; and when I got to know them, and they me, this difference rapidly developed itself. Their amazement at me, my language, my rules, and ways, once subsided, I found some of these heavy-looking, gaping rustics wake up into sharp-witted girls enough. I discovered amongst them not a few examples of natural politeness, and innate self-respect, as well of excellent capacity, that won both my goodwill and my admiration. These soon took a pleasure in doing their work well, in keeping their persons neat, in learning their tasks regularly, in acquiring quiet and orderly manners. The rapidity of their progress, in some instances, was even surprising; and anhonest and happy pride I took in it; besides, I began personally to like some of the best girls, and they like me. I had amongst my scholars several farmers’ daughters—young women grown, almose. These could already read, write, and sew; and to them I taught the elements of grammar, geography, history, and the finer kinds of needlework. I found estimable characters amongst them—characters desirous of information and disposed for improvement—with whom I passed many a pleasant evening hour in their own homes. Their parents then (the farmer and his wife) loaded me with attentions. There was an enjoyment in accepting their simple kindness, and in repaying it by a consideration—a scrupulous regard to their feelings—to which they were not, perhaps, at all times accustomed, and which both charmed and benefited them; because, while it elevated them in their own eyes, it made them competitive to merit the deferential treatment they received.2中译英旅游是一项集观光、娱乐、健身为一体的愉快而美好的活动。

2010年湖南师范大学英语翻译基础考研真题

育明教育【温馨提示】现在很多小机构虚假宣传,育明教育咨询部建议考生一定要实地考察,并一定要查看其营业执照,或者登录工商局网站查看企业信息。

目前,众多小机构经常会非常不负责任的给考生推荐北大、清华、北外等名校,希望广大考生在选择院校和专业的时候,一定要慎重、最好是咨询有丰富经验的考研咨询师!I. Directions:Translate the following words, abbreviations or terminology into their target language respectively. There are altogether 30items in this part of the test, 15 in English and 15 in Chinese, with one pint for each. (30’)1.APEC2.ASEAN3.CFO4.CPI5.EMS6.FBI7.GPS8.IPO9.NATO10.International Monetary Fund11.most favored nations12.Intellectual Property Rights13.Certified Public Accountant14.European Free Trade Association15.International Atomic Energy Agency16.按揭贷款17.保健食品18.保税区19.不正之风20.春运21.第三产业22.法制国家23.国际惯例24.货到付款25.亏损企业26.减员增效27.联合兼并28.留职停薪29.特别提款权30.市场准入。

2010年湖南师范大学翻译硕士英语考研真题及其答案解析

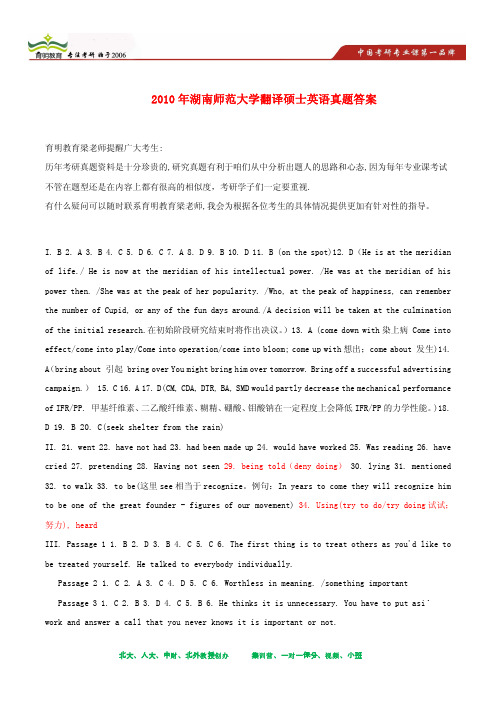

2010年湖南师范大学翻译硕士英语真题答案育明教育梁老师提醒广大考生:历年考研真题资料是十分珍贵的,研究真题有利于咱们从中分析出题人的思路和心态,因为每年专业课考试不管在题型还是在内容上都有很高的相似度,考研学子们一定要重视.有什么疑问可以随时联系育明教育梁老师,我会为根据各位考生的具体情况提供更加有针对性的指导。

I. B 2. A 3. B 4. C 5. D 6. C 7. A 8. D 9. B 10. D 11. B (on the spot)12. D(He is at the meridian of life./ He is now at the meridian of his intellectual power. /He was at the meridian of his power then. /She was at the peak of her popularity. /Who, at the peak of happiness, can remember the number of Cupid, or any of the fun days around./A decision will be taken at the culmination of the initial research.在初始阶段研究结束时将作出决议。

)13. A (come down with染上病 Come into effect/come into play/Come into operation/come into bloom; come up with想出;come about 发生)14. A(bring about 引起 bring over You might bring him over tomorrow. Bring off a successful advertising campaign.) 15. C 16. A 17. D(CM, CDA, DTR, BA, SMD would partly decrease the mechanical performance of IFR/PP. 甲基纤维素、二乙酸纤维素、糊精、硼酸、钼酸钠在一定程度上会降低IFR/PP的力学性能。

湖南师范大学翻译硕士英语学位MTI考试真题2012年

湖南师范大学翻译硕士英语学位MTI考试真题2012年(总分:150.00,做题时间:90分钟)一、PART Ⅰ TRANSLATION OF WORDS AND PHRASES(总题数:0,分数:0.00)二、SECTION A ENGLISH TO CHINESE(总题数:15,分数:15.00)1.Queensland(分数:1.00)__________________________________________________________________________________________ 正确答案:()解析:Queensland昆士兰州2.Quebec(分数:1.00)__________________________________________________________________________________________ 正确答案:()解析:Quebec魁北克3.Santa Claus(分数:1.00)__________________________________________________________________________________________ 正确答案:()解析:Santa Claus圣诞老人4.Sir Walter Scott(分数:1.00)__________________________________________________________________________________________ 正确答案:()解析:Sir Walter Scott沃尔特·司各特爵士5.Stamp Tax(分数:1.00)__________________________________________________________________________________________ 正确答案:()解析:Stamp Tax印花税6.Standard & Poor"s(分数:1.00)__________________________________________________________________________________________ 正确答案:()解析:Standard & Poor"s标准普尔7.Suez Canal(分数:1.00)__________________________________________________________________________________________ 正确答案:()解析:Suez Canal苏伊士运河(分数:1.00)__________________________________________________________________________________________ 正确答案:()解析:Sydney悉尼9.Vancouver(分数:1.00)__________________________________________________________________________________________ 正确答案:()解析:Vancouver温哥华10.West Indies(分数:1.00)__________________________________________________________________________________________ 正确答案:()解析:West Indies西印度群岛11.phonetics(分数:1.00)__________________________________________________________________________________________ 正确答案:()解析:phonetics语音学12.translation after sense(分数:1.00)__________________________________________________________________________________________ 正确答案:()解析:translation after sense翻译后的意义13.Eurasia Land Bridge(分数:1.00)__________________________________________________________________________________________ 正确答案:()解析:Eurasia Land Bridge欧亚大陆桥14.monetary integration(分数:1.00)__________________________________________________________________________________________ 正确答案:()解析:monetary integration货币一体化15.Europe"s sovereign-debt crisis(分数:1.00)__________________________________________________________________________________________ 正确答案:()解析:Europe"s sovereign-debt crisis欧洲主权债务危机三、SECTION B CHINESE TO ENGLISH(总题数:15,分数:15.00)(分数:1.00)__________________________________________________________________________________________ 正确答案:()解析:载人航天manned space flight17.行政问责(分数:1.00)__________________________________________________________________________________________ 正确答案:()解析:行政问责administrative accountability18.公务接待费(分数:1.00)__________________________________________________________________________________________ 正确答案:()解析:公务接待费expenditure for official acception19.法人代表(分数:1.00)__________________________________________________________________________________________ 正确答案:()解析:法人代表legal representative20.蜗居(分数:1.00)__________________________________________________________________________________________ 正确答案:()解析:蜗居Snail House21.富二代(分数:1.00)__________________________________________________________________________________________ 正确答案:()解析:富二代affluent second generation22.工业“三废”(分数:1.00)__________________________________________________________________________________________ 正确答案:()解析:工业“三废”three wastes in the industry23.潜规则(分数:1.00)__________________________________________________________________________________________ 正确答案:()解析:潜规则latent rule24.发动机排量(分数:1.00)__________________________________________________________________________________________ 正确答案:()解析:发动机排量engine discharge25.公民健康档案(分数:1.00)__________________________________________________________________________________________ 正确答案:()解析:公民健康档案Citizen"s Health Records26.全球化(分数:1.00)__________________________________________________________________________________________ 正确答案:()解析:全球化Globalization27.增值税(分数:1.00)__________________________________________________________________________________________ 正确答案:()解析:增值税value-added tax28.住房信贷政策(分数:1.00)__________________________________________________________________________________________ 正确答案:()解析:住房信贷政策credibility policy of housing29.颐和园(分数:1.00)__________________________________________________________________________________________ 正确答案:()解析:颐和园the Summer Place30.法律硕士(分数:1.00)__________________________________________________________________________________________ 正确答案:()解析:法律硕士Master of Law四、PART Ⅱ TRANSLATION OF TEXTS(总题数:0,分数:0.00)五、SECTION A ENGLISH TO CHINESE(总题数:1,分数:60.00)31.World food prices are pushing higher—the United Nations overall food index shows a 28.3% annual increase, with cereals up 44.1%—sparking concerns that a new food crisis may be emerging, just three years after the last one. Does this mean the world is running out of food?The quick answer is that the world does seem to be running low on cheap food. This supply shortage stems from the failure of governments and donors over nearly three decades to fund the basic agricultural research, investments in rural infrastructure, and training for smallholder farmersnecessary to push out the productivity frontier.Until recently, world food crises have been relatively rare events—occurring about three times a century. The food crisis of 2007~2008, although scary at the time, was relatively mild by comparison. Prices for wheat, rice and maize—the staple foods that provide well over half the world population"s energy intake directly and a good deal more indirectly via livestock products—rose 96.7% between 2006 and 2008, not approaching the spikes in the mid-1970s when corrected for inflation. Yet here we are just a few years later, talking about food prices again.(分数:60.00)__________________________________________________________________________________________正确答案:()解析:世界粮食价格正在逐步走高——美国综合粮食指数年均增长28.3%,谷物价格上涨了44.1%,这种情况引发了人们对新一轮粮食危机的担忧,毕竟最近一次粮食危机刚刚过去三年。

湖南师范大学(2010-2017)考研真题

2017年湖南师范大学333教育综合试题一、名词解释(每小题5分,共30分)1. 庶富教2. 道尔顿制3.元认知4. 五育并举5.理想国6. 顺向迁移二、简答题(每小题10分,共60分)1.教育学的研究对象和任务,以及为什么必须对教育问题进行研究。

2.按教育机构划分,教育分为哪几种?3.简述晏阳初的四大教育三大方式。

4.简述朱子读书法。

5. 简述夸美纽斯在教育史上的贡献。

6. 简述人文主义教育的基本特征。

三、论述题(每小题20分,共40分)1.论述学习动机与学习效果的关系。

2.教师职业性质及特点,结合实际论述。

四、论述题(共20分)材料:一个表演活动中,一个孩子演绿叶,爸爸无所谓,姥姥想让孩子演红花,孩子也不愿意表演绿叶。

问:1.出现这种现象的原因是。

2.老师应该如何处理。

3.你怎么和家长沟通这个问题。

2016年湖南师范大学333教育综合试题一、名词解释(每小题5分,共30分)1.自我效能感2.上位学习3.“从做中学”4.《教育漫话》5.“活教育”6.《大学》二、简答题(每小题10分,共40分)1.黄炎培职业教育主要思想及其对现代教育的启示。

2.墨家教育思想的特征及其借鉴意义。

3.谈谈你对苏格拉底“知识即美德”的理解。

4.裴斯泰洛齐“教育心理学化”的主要内容及其影响。

三、分析论述题(每小题20分,共80分)1.试分析错误观念及其对教学的启示。

2.教育学理论建设的原则,如何贯彻教育学理论建设的原则?3.学校教育在人的身心发展中的特殊性,如何发挥学校教育的特殊作用?4.材料:BBC纪录片《我们的孩子够坚强吗》(1)中国和英国的基础教育都应该注意什么?(2)这场教学比赛是一般的教学比赛么?评价教学比赛(3)中英教育应互相学习什么?2015年湖南师范大学333教育综合试题一、名词解释(每题5分,共30分)1.分斋教学2.生活教育3.美德即知识4.教育即经验的改造5.品德6.功能固着二、简答题(每题10分,共20分)1.在现代社会,和学校教育、家庭教育一样,社会教育得到了蓬勃的发展,社会教育的迅速发展,有哪些原因?2.简述文化对教育的作用。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

一、英译汉All through my boyhood and youth, I was known as an idler; and yet I was always busy on my own private end, which was to learn to write. I kept always two books in my pocket, one to read, one to write in. As I walked, m y mind was busy fitting what I saw with appropriate words; when I sat by the roadside, I would either read, or a pencil and a notebook would be in m y hand, to note down the features of the scene or write som e poor lines of verse. Thus I lived with words. And what I thus wrote was for no future use; it was written consciously for practice. It was not so much that I wished to be an author (though I wished that too) as that I had vowed that I would learn to write. That was a proficiency that tem pted m e; and I practiced to acquire it. Description was the principal field of m y exercise; for to any one with senses there is always som ething worth describing, and town and country are but one continuous subject. But I worked in ot her ways also; I often accom panied m y walks with dramatic dialogues, in which I played m any parts; and often exercised m yself in writing down conversations from memory.This was all excellent, no doubt. And yet this was not the m ost efficient part of m y training. Good as it was, it only taught m e the choice of the essential note and the right word. And regarded as training, it had one grave defect; for it set m e no standard of achievem ent. So there was perhaps more profit,as there was certainly more effort,in my secret labors at hom e.二、汉译英改编自下文。

原文出处大家品论写作之实践经验与学问真谛来源:上海外语教育出版社作者:罗伯特•路易斯•史蒂文森Early Efforts at WritingAll through m y boyhood and youth, I was known as an idler; and yet I was always busy on m y own private end, which was to learn to write. I kept always two books in my pocket, one to read, one to write in. As I walked, my mind was busy fitting what I saw with appropriate words; when I sat by the roadside, I would either read, or a pencil and a notebook would be in my hand, to note down the features of the scene or write som e poor lines of verse. Thus I lived with words. And what I thus wrote was for no future use; it was written consciously for practice. It was not so much that I wished to be an author (though I wished that too) as that I had vowed that I would learn to write. That was a proficiency that tem pted me; and I practiced to acquire it. Description was the principal field of m y exercise; for to any one with senses there is always som ething worth describing, and town and country are but one continuous subject. But I worked in other ways also; I often accom panied my walks with dramatic dialogues, in which I played many parts; and often exercised myself in writing down conversations from memory.This was all excellent, no doubt. And yet this was not the m ost efficient part of m y training. Good as it was, it only taught m e the choice of the essential note and the right word. And regarded as training, it had one grave defect; for it set m e no standard of achievem ent. So there was perhaps more profit,as there was certainly more effort,in m y secret labors at hom e. Whenever I read a book or a passage that particularly pleased m e,in which a thing was said or an effect rendered with propriety ,in which there was either some conspicuous force or some happy distinction in the style,I m ust sit down at once and set m yself to ape that quality.I was unsuccessful, and I knew it; and tried again,and was again unsuccessful and always unsuccessful; but at least in these vain bouts I got som e pract ice in rhythm,in harmony,in construction and the coordination of parts. I have thus played the sedulous ape to Hazlitt,to Lam b,to Wordsworth,to Defoe,to Hawthorne.That,like it or not,is the way to learn to write; whether I have profited or not,that is the way. It was so,if we could trace it out,that all men have learned. Perhaps I hear some one cry out: But this is not he way to be original! It is not; nor is there any way but to be born so. Nor yet, if you are born original, is there anything in this training that shall clip the wings of your originality. Burns is the very type of a m ost original force in letters, he was of all m en the m ost imitative. Shakespeare himself proceeds directly from a school. It is only from a school that we can expect to hav e good writers; it is alm ost invariably from a school that great writers issue. Nor is there anything here that should astonish the considerate. Before he can tell what cadences he truly prefers, the student should have tried all that are possible; before he can tell what cadences he truly prefers, the student should have tried all that are possible; before he can choose a fitting key of words, he should long have practiced the literary scales; and it is only after years of such exercises that he can sit down at last, legions of words swarming to his call, dozens of turns of phrasesimultaneously bidding for his choice, and he him self knowing what he wants to do and(within the narrow limit of a m an's ability)able to do it.早年在写作上的初期尝试从我的童年到青年时期,大家一直把我看做一个游手好闲的人,其实我一直在为个人的目标私下忙着,那就是练习写作。