WHO生长发育曲线图-男孩

早产儿生长曲线图

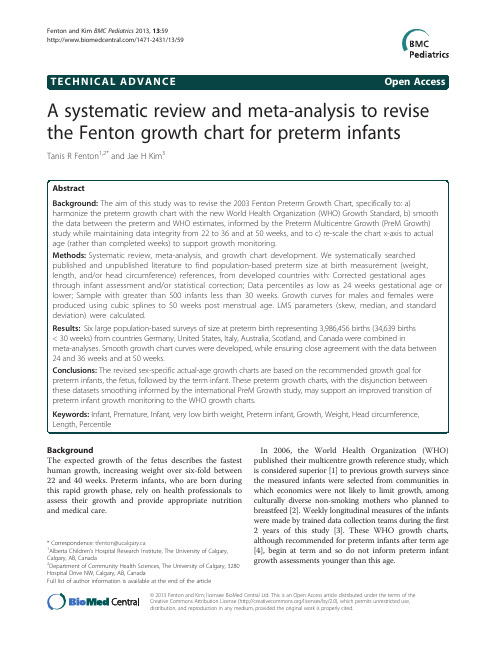

A systematic review and meta-analysis to revise the Fenton growth chart for preterm infantsTanis R Fenton 1,2*and Jae H Kim 3BackgroundThe expected growth of the fetus describes the fastest human growth,increasing weight over six-fold between 22and 40weeks.Preterm infants,who are born during this rapid growth phase,rely on health professionals to assess their growth and provide appropriate nutrition and medical care.In 2006,the World Health Organization (WHO)published their multicentre growth reference study,which is considered superior [1]to previous growth surveys since the measured infants were selected from communities in which economics were not likely to limit growth,among culturally diverse non-smoking mothers who planned to breastfeed [2].Weekly longitudinal measures of the infants were made by trained data collection teams during the first 2years of this study [3].These WHO growth charts,although recommended for preterm infants after term age [4],begin at term and so do not inform preterm infant growth assessments younger than this age.*Correspondence:tfenton@ucalgary.ca 1Alberta Children ’s Hospital Research Institute,The University of Calgary,Calgary,AB,Canada 2Department of Community Health Sciences,The University of Calgary,3280Hospital Drive NW,Calgary,AB,CanadaFull list of author information is available at the end of thearticle©2013Fenton and Kim;licensee BioMed Central Ltd.This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (/licenses/by/2.0),which permits unrestricted use,distribution,and reproduction in any medium,provided the original work is properly cited.Fenton and Kim BMC Pediatrics 2013,13:59/1471-2431/13/59Optimum growth of preterm infants is considered to be equivalent to intrauterine rates[5-7]since a superior growth standard has not been defined.Perhaps the best estimate of fetal growth may be obtained from large population-based studies,conducted in developed coun-tries[8],where constraints on fetal growth may be less frequent.A recent multicentre study by our group(the Preterm Multicentre Growth(PreM Growth)Study)revealed that although the pattern of preterm infant growth was gener-ally consistent with intrauterine growth,the biggest devi-ation in weight gain velocity between the preterm infants and the fetus and infant was just before term,between37 and40weeks(Fenton TR,Nasser R,Eliasziw M,Kim JH, Bilan D,Sauve R:Validating the weight gain of preterm in-fants between the reference growth curve of the fetus and the term infant,The Preterm Infant Multicentre Growth Study.Submitted BMC Ped2012).Rather than demon-strating the slowing growth velocity of the term infant during the weeks just before term,the preterm infants had superior,close to linear,growth at this age.This finding has been observed by others as well[9-11].Therefore, there is evidence to support a smooth transition on growth charts between late fetal and early infant ages. Several previous growth charts based on size at birth presented their data as completed age,which affects the interpretation and use of a growth chart[12].The use of completed weeks when plotting a growth chart requires all the measurements to be plotted on the whole week vertical axes.However,the use of completed weeks in a neonatal unit may not be intuitive,as nursery staff and parents think of infants as their exact age,and not age truncated to previous whole weeks.The advent of computers in health care,for clinical care and health recording,allow the use of the computer to plot growth charts,daily and with accuracy.It would make sense to support plotting daily measurements continuously by shifting the data collected as completed weeks to the midpoint of the next week to remove the truncation of the data collection as completed weeks.The objectives of this study were to revise the2003 Fenton Preterm Growth Chart,specifically to:a)use more recent data on size at birth based on an inclusion criteria, b)harmonize the preterm growth chart with the new WHO Growth Standard,c)to smooth the data between the preterm and WHO estimates while maintaining integrity with the data from22to36and at50weeks, d)to derive sex specific growth curves,and to e)re-scale the chart x-axis to actual age rather than completed weeks,to support growth monitoring.MethodsTo revise the growth chart,thorough literature searches were performed to find published and unpublished population-based preterm size at birth(weight,length, and/or head circumference)references.The inclusion criteria,defined a priori,designed to minimize bias by restriction[13],were to locate population-based studies of preterm fetal growth,from developed countries with: a)Corrected gestational ages through fetal ultrasoundand/or infant assessment and/or statisticalcorrection;b)Data percentiles at24weeks gestational age orlower;c)Sample of at least25,000babies,with more than500infants aged less than30weeks;d)Separate data on females and males;e)Data available numerically in published form orfrom authors,f)Data collected within the past25years(1987to2012)to account for any secular trends.A.Data selection and combinationMajor bibliographic databases were searched:MEDLINE (using PubMed)and CINHAL,by both authors back to year1987(given our25year limit),with no language restrictions,and foreign articles were translated.The following search terms as medical subject headings and textwords were used:(“Preterm infant”OR“Premature Birth”[Mesh])OR(“Infant,Premature/classification”[Mesh] OR“Infant,Premature/growth and development”[Mesh] OR“Infant,Premature/statistics and numerical data”[Mesh] OR“Infant,very low birth weight”[Mesh])AND (percentile OR*centile*OR weeks)AND(weight OR head circumference OR length).Grey literature sites including clinical trial websites and Google were searched in February 2012.Reference lists were reviewed for relevant studies.All of the found data was reported as completed weeks except for the German Perinatal Statistics,which were reported as actual daily weights[14].To combine the datasets,the German data was temporarily converted to completed weeks.A final step converted the meta-analyses to actual age.bine the data to produce weighted intrauterine growth curves for each sexThe located data(3rd,10th,50th,90th,and97th percentiles for weight,head circumference,and length)that met the inclusion criteria were extracted by copying and pasting into spreadsheets.The male and female percentile curves from each included data set for weight,head circumference and length were plotted together so they could be examined visually for heterogeneity(Figures1,2, and3).The data for each gender were combined by using the weekly data for the percentiles:3rd,10th,50th,90th, and97th,weighted by the sample sizes.The combined data was represented by relatively smooth curves.C.Develop growth monitoring curvesTo develop the growth monitoring curves that joined the intrauterine meta-analysis data with the WHO Growth Standard(WHOGS)smoothly,the following cubic spline procedure was used to meet two objectives:a)To maintain integrity with the meta-analysis curvesfrom22to36weeks.Integrity of the fit wasassumed to be agreement within3%at each week. b)To ensure fit of the data to the WHO values at50weeks,within0.5%.Procedure:1)Cubic splines were used to interpolate smoothvalues between selected points(22,25,28,32,34,36 and50weeks).Extra points were manually selected at40,43and46weeks in order to produceacceptable fit through the underlying data.ThePreM Growth study(Fenton TR,Nasser R,Eliasziw M,Kim JH,Bilan D,Sauve R:Validating the weight gain of preterm infants between the referencegrowth curve of the fetus and the term infant,The Preterm Infant Multicentre Growth Study.Submitted BMC Ped2012)conducted to inform the transition between the preterm and WHO data,was used to inform this step.The Prem Growth Studyfound that preterm infants growth in weightfollowed approximately a straight line between37and45weeks,as others have also noted[9-11].2)LMS values(measures of skew,the median,and thestandard deviation)[15]were computed from theinterpolated cubic splines at weekly intervals.Cole’sprocedures[15]and an iterative least squares method were used to derive the LMS parameters(L=Box-Cox power,M=median,S=coefficient of variation)fromFigure1Boys birthweight centiles(3rd,50th and97th)from the six included studies,along with the boy’s meta-analysis curves (bold).Figure2Girls head circumference centiles(3rd,50th and97th) centiles from the included studies,along with the girl’smeta-analysis curves(dotted),and after40weeks,the World Health Organization centiles (dashed).Figure3Girls length centiles(3rd,50th and97th)centiles from the included studies,along with the meta-analysis curves (dotted),and after40weeks,the World Health Organization centiles(dashed).Table2Number of infants each week from each studyGestational age Voight,2010Olsen,2010Bertino,2010Kramer,2001Roberts,1999Bonellie,2008 Females Males Females Males Females Males Females Males Females Males Females Males 22188321----80827174--23431560133153381061147995--245757044384512024148156115135120126 257138466037224038184202136180115118 268129687738813558191234188235179172 271073120396610305261188254231284174177 2812761536118712817963287330287361246239 2915161838125415057072299392325397245265 301853221216061992107114390467440571317313 312283295620442460126140461584548743136148 32**300736771651837959978771117193205 33**418650142112401055136812001471239256 34**593672912633492018255320862657374422 35**508269523664183391431434184092644653 36**46907011562665820396487320878810481265 37**43726692129114921730819965161051866020062499 38**57558786352439764751651947478095140446306387 39**597883245295545275068776236884672871869910706 40**55297235567256531107381127371375701415531264414230 *Not reported.the multicentre meta-analyses for weight,headcircumference and length.The LMS splines weresmoothed slightly while maintaining data integrity asnoted above.3)The final percentile curves were produced from thesmoothed LMS values.4)A grid similar to the2003growth chart was used,but the growth curves were re-scaled along thex-axis from completed weeks to allow clinicians toplot infant growth by actual age in weeks,and aslight modification(scaled to60centimeters insteadof65)was made to the y-axis.pared the revised charts with the2003version The revised growth charts were compared graphically with the original2003Fenton preterm growth chart.To makethe differences in chart values more apparent,the2003 chart data was also shifted to actual weeks for these com-parison figures.ResultsSix large population based surveys[14,16-20]of size at preterm birth from countries Germany,United States, Italy,Australia,Scotland,and Canada were located that met the inclusion criteria(Table1).The literature search identified2436papers,of which2373were discarded as being not relevant or duplicates based on the titles (Figure4).Reviewing reference lists identified another 12studies.Seventy-five studies were examined in detail, however27of these did not meet the date criteria.Among the48studies that met the date of birth criteria,some did not meet the other inclusion criteria for the following reasons:Did not meet the criterion for more than25,000 babies[21-35],no low gestational age infants less than25 weeks[31,36-41],insufficient number less than30weeks [34,42-45],no statistical correction for inaccurate gestational ages[46-48],numerical data not available [49-51],number of infants each week were not available [52],number of infants in the subgroups each week were not available[53],was not population based[54-56],no direct measurements[27],some of the data[57]was also in one of the larger included studies[17].Included in the meta-analyses were almost four million (3,986,456)infants at birth(34,639less than30weeks) from six studies for weight(Table2),and173,612infants for head circumference,and151,527for length[16,18]. The World Health Organization data measurements were made longitudinally on882infants.The individual datasets from the literature showed good agreement with each other,especially along the 50th and lower centiles(Figures1,2,and3)and the meta-analysis curves had a close fit with the individual datasets up to36weeks and at50weeks(Figures5,6,7). The final splined weight curves were within3%of the meta-analysis curves for24through36weeks for both gen-ders,except for a3.8%difference for girls at32weeks along the90th centile.None of the length measurements differed by more than1.8%percent between the meta-analysis and the splined curves;all weeks of the head circumference curves were within 1.5%.The meta-analyses for headFigure5Boys meta-analysis weight curves(dotted)with the final smoothed growth chart curves (dashed).Figure6Boys meta-analysis head circumference curves (dotted)with the final smoothed growth chart curves (dashed). Figure7Boys meta-analysis length curves(dotted)with the final smoothed growth chart curves(dashed).circumference and length for girls and boys were close enough to normal distributions that normal distributions were used to summarize the data.The measures at50 weeks were within0.5%of the WHOGS values.Girl and boy charts were prepared(Figure8and9),by shifting the age by0.5weeks to allow plotting by exact age instead of completed weeks.The LMS Parameters [15]were used to develop the exact z-score and percentile calculators for the new growth chart.In the two graphical comparisons between the revised growth charts,one for each sex,with the2003Fenton preterm growth chart revealed that the curves were quite similar(Figures10and11).Generally the new girls’curves were slightly lower(Figure10)and the new boys’slightly higher(Figure11)for all3parameters(weight,head cir-cumference,and length)than the2003curves.The most dramatic visual and numerical difference between the new charts and the2003chart was the higher shift of the boys’weight curves after40weeks compared to the2003chart, reaching a maximum difference at50weeks of650,580, and740grams at the3rd,50th,and97th percentiles,re-spectively.The second biggest visual difference was thegrowth chart for girls.lower pattern of the girls’length curves below37weeks; the difference in length reached a maximum numerical value of1.7centimeters at24weeks along the97th percentile.DiscussionWe used a strict set of inclusion criteria to include only the best data available to convert fetal and infant size data into fetal-infant growth charts for preterm infants.The re-vised sex-specific actual-age(versus completed weeks) growth charts(Figure9and10),are based on birth size in-formation of almost four million births with confirmed or corrected gestational ages,born in developed countries (See Features of the new growth chart).The revised charts are based on the recommended growth goal for preterm infants,the fetus and the term infant,with smoothing of the disjunction between these datasets,based on the find-ings of our international multicentre validation study (Fenton TR,Nasser R,Eliasziw M,Kim JH,Bilan D,Sauve R:Validating the weight gain of preterm infants between the reference growth curve of the fetus and the term in-fant,The Preterm Infant Multicentre Growth Study. Submitted BMC Ped2012).These charts are consist-ent with the meta-analysis data up to and includinggrowth chart for boys.36weeks,thus they can be used for the assessment of size for gestational age for preterm infants under37 weeks of gestational age.This growth chart is likely ap-plicable to preterm infants in both developed and de-veloping countries since the data was selected from developed countries to minimize the influence from cir-cumstances that may not have been ideal to support growth.Features of the new growth chartBased on the recommended growth goal for preterm infants:The fetus and the term infantGirl and boy specific chartsEquivalent to the WHO growth charts at50weeks gestational age(10weeks post term age).Large preterm birth sample size of4million infants; Recent population based surveys collected between 1991to2007Data from developed countries includingGermany,Italy,United States,Australia,Scotland, and CanadaCurves are consistent with the data to36weeks, thus can be used to assign size for gestational age up to and including36weeks.Chart is designed to enable plotting as infants are measured,not as completed weeks.The x axis wasadjusted for this chart so that infant size data can be plotted without age adjustment,i.e.Babies should be plotted as exact ages,that is a baby at253/7weeksshould be plotted along the x axis between25and26weeks.Exact z-score and percentile calculator available for download from http://ucalgary.ca/fenton.Data isavailable for research upon request.It may be more intuitive to plot on growth charts using exact ages rather than on the basis of completethe revised growth chart for girls(solid curves)and the2003Fenton growth chart for length,head circumference,and weight).Both the2003and the revised growthweeks.Several years ago,the WHO used completed age for growth chart development[12].This recommenda-tion was likely due to the way data had been collected in the past,that is all260/7through266/7week infants were included in the26week completed week category. However,with the use of computers to plot on growth charts comes the potential to more accurately plot mea-surements to the exact day of data collection.Thus the time scale of the horizontal axes of these new growth charts were re-scaled to actual age,for ease of use and un-derstanding.For example,a baby at253/7can be intui-tively plotted between25and26weeks.Exact z-score and centile calculators for the revised charts are available for download:http://ucalgary.ca/ fenton.Data is available for research upon request.The data revealed that between22weeks to50weeks post menstrual age,the fetus/infant multiplies its weight tenfold,for example,the girls’median weight increased from a median ing a fetal-infant growth chart allows clinicians to compare preterm infants’growth to an estimated reference of the fetus and the term infant.There was a remarkably close fit of the included preterm surveys for weight,head circumference and length from the6countries,especially at the50th percentile,even though the data came from different countries.The splining procedures we used have produced a chart that has integrity and good agreement with the original data.Smoothing of the LMS parameters is recommended since minor fluctuations are more likely due to sampling errors rather than physiological events [15].Experts recommend that growth charts be developed based on smoothed L,M and S,to constrain the adjacent curves so that they relate to each other smoothly[15].The World Health Organization set their L parameter to1for head circumference and length,while they maintained the exact L values for infants’weights[58].The data under study here revealed the same effect as the WHO data;wethe revised growth chart for boys(solid curves)and the2003Fenton growth chart for length,head circumference,and weight).Both the2003and the revised growthfound that both head circumference and length were close enough to normal distributions that normal distributions could summarize the data,while the exact L’s were needed to retain the nuances of the weight curves.The differences between the revised growth charts and the2003Fenton preterm growth chart may reflect improvements since the selected preterm growth references for the new versions are more likely globally representative of fetal and infant growth.Some of the differences between the current charts and the2003version are likely due to the separation into girl and boy charts,since the shifts of the girls’curves tend to be downward and the boys’curves upward.The weight shifts after40weeks were upward for both sexes,due to the higher values for the WHOGS compared to the CDC growth reference[59]at 10weeks post term.The ideal growth pattern of preterm infants remains undefined.These revised growth charts were developed based on the growth patterns of the fetus(as has been determined by size at birth in the large population stud-ies)and the term infant(based on the WHO Growth Standard)[2].Ultrasound studies and comparison of subgroups of prematurely born infants suggest that the fetal studies,such as those used in this development,may be biased by the premature birth since fetuses who remain in utero likely differ in important ways from babies who are born early[60,61].However,fetal size from these imperfect studies may be the best data available at this point in time for comparing the growth of preterm infants since the alternative,to compare to in utero infants requires extrapolation from ultrasound measurements.To use other premature infants as the growth reference for preterm infants may not be ideal since the ideal growth of preterm infants has not been defined,has been changing over time[62],and is influenced by the nutrition and medical care received after birth[63,64].Although the WHOGS is considered to be a growth standard,the infants in the population-based surveys of size at birth are more likely representative of the reference populations and were not selected to be healthy.Thus these growth charts are growth references and are not a growth standard.The INTERGROWTH study,currently underway,will rectify this problem,since their purpose is to develop prescriptive standards for fetal and preterm growth[65].ConclusionThe inclusion of data from a number of developed countries increases the generalizability of the growth chart.The revised preterm growth chart,harmonized with the World Health Organization Growth Standard at50weeks,may support an improved transition of preterm infant growth monitoring to the WHO peting interestsThe authors declare that they have no competing interests.Authors’contributionsThe author’s responsibilities were as follows:JHK suggested the study,TRF& JHK designed the study and conducted independent literature searches,TRF extracted the data,performed the statistical analysis,and wrote the manuscript.Both of the authors contributed to interpret the findings and writing the manuscript,and both authors read and approved the final manuscript.AcknowledgementsMany thanks to Patrick Fenton and Misha Eliasziw for statistical assistance, Roseann Nasser,Reg Sauve,Debbie O’Connor,and Sharon Unger for encouragement and advice,and Jayne Thirsk for editing advice.Author details1Alberta Children’s Hospital Research Institute,The University of Calgary, Calgary,AB,Canada.2Department of Community Health Sciences,The University of Calgary,3280Hospital Drive NW,Calgary,AB,Canada.3Division of Neonatology,UC San Diego Medical Center,200West Arbor Drive MPF 1140,San Diego,CA,USA.Received:12October2012Accepted:10April2013Published:20April2013References1.Secker D:Promoting optimal monitoring of child growth in Canada:using the new WHO growth charts.Can J Diet Pract Res2010,71:e1–e3. 2.De Onis M,Garza C,Victora CG,Onyango AW,Frongillo EA,Martines J:TheWHO Multicentre Growth Reference Study:planning,study design,and methodology.Food Nutr Bull2004,25:S15–S26.3.Borghi E,De Onis M,Garza C,den BJ V,Frongillo EA,Grummer-Strawn L,Van Buuren S,Pan H,Molinari L,Martorell R,Onyango AW,Martines JC:Construction of the World Health Organization child growth standards: selection of methods for attained growth curves.Stat Med2006,25:247–265.4.Dietitians of Canada,Canadian Pediatric Society,College of FamilyPhysicians of Canada,Community Health Nurses of Canada:PromotingOptimal Monitoring of Child Growth in Canada:Using the New WHOGrowth Charts.Can J Diet Pract Res2010,71:1–22.mittee on Nutrition American Academy Pediatrics:Nutritional Needs ofPreterm Infants,Pediatric Nutrition Handbook.6th edition.Elk Grove Village Il:American Academy Pediatrics;2009.6.Agostoni C,Buonocore G,Carnielli VP,De CM,Darmaun D,Decsi T,et al:Enteral nutrient supply for preterm infants.A comment of the ESPGHANCommittee on Nutrition.J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr2010,50:85–91.7.Nutrition Committee,Canadian Paediatric Society:Nutrient needs andfeeding of premature infants.CMAJ1995,152:1765–1785.8.United Nations Statistics Division:Composition of macro geographical(continental)regions,geographical sub-regions,and selected economic andother groupings./unsd/methods/m49/m49regin.htm#developed.9.Niklasson A,Engstrom E,Hard AL,Wikland KA,Hellstrom A:Growth in verypreterm children:a longitudinal study.Pediatr Res2003,54:899–905. 10.Bertino E,Coscia A,Mombro M,Boni L,Rossetti G,Fabris C,Spada E,MilaniS:Postnatal weight increase and growth velocity of very low birthweight infants.Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed2006,91:F349–F356.11.Krauel VX,Figueras AJ,Natal PA,Iglesias PI,Moro SM,Fernandez PC,Martin-Ancel A:Reduced postnatal growth in very low birth weight newborns with GE<or=32weeks in Spain.An Pediatr(Barc)2008,68:206–212. 12.World Health Organization:Physical status:the use and interpretation ofanthropometry.Report of a WHO Expert Committee.World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser1995,854:1–452.13.Hennekens CH,Buring JE:Analysis of epidemiologic studies:Evaluatingthe role of confounding.In Epidemiology in Medicine.Edited by Mayrent SL, Little B.Boston;1987:287–323.14.Voigt M,Zels K,Guthmann F,Hesse V,Gorlich Y,Straube S:Somaticclassification of neonates based on birth weight,length,and headcircumference:quantification of the effects of maternal BMI andsmoking.J Perinat Med2011,39:291–297.15.Cole TJ,Green PJ:Smoothing reference centile curves:the LMS methodand penalized likelihood.Stat Med1992,11:1305–1319.16.Olsen IE,Groveman SA,Lawson ML,Clark RH,Zemel BS:New intrauterinegrowth curves based on United States data.Pediatrics2010,125:e214–e224.17.Roberts CL,Lancaster PA:Australian national birthweight percentiles bygestational age.Med J Aust1999,170:114–118.18.Bertino E,Spada E,Occhi L,Coscia A,Giuliani F,Gagliardi L,Gilli G,Bona G,Fabris C,De CM,Milani S:Neonatal anthropometric charts:the Italianneonatal study compared with other European studies.J PediatrGastroenterol Nutr2010,51:353–361.19.Bonellie S,Chalmers J,Gray R,Greer I,Jarvis S,Williams C:Centile charts forbirthweight for gestational age for Scottish singleton births.BMCPregnancy Childbirth2008,8:5.20.Kramer MS,Platt RW,Wen SW,Joseph KS,Allen A,Abrahamowicz M,Blondel B,Breart G:A new and improved population-based Canadianreference for birth weight for gestational age.Pediatrics2001,108:E35. 21.Karna P,Brooks K,Muttineni J,Karmaus W:Anthropometric measurementsfor neonates,23to29weeks gestation,in the1990s.Paediatr PerinatEpidemiol2005,19:215–226.22.Kwan AL,Verloove-Vanhorick SP,Verwey RA,Brand R:Ruys JH:[Birthweight percentiles of premature infants needs to be updated].Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd1994,138:519–522.23.Riddle WR,DonLevy SC,Lafleur BJ,Rosenbloom ST,Shenai JP:Equationsdescribing percentiles for birth weight,head circumference,and length of preterm infants.J Perinatol2006,26:556–561.24.Figueras F,Figueras J,Meler E,Eixarch E,Coll O,Gratacos E,Gardosi J,Carbonell X:Customised birthweight standards accurately predictperinatal morbidity.Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed2007,92:F277–F280. 25.Fok TF,So HK,Wong E,Ng PC,Chang A,Lau J,Chow CB,Lee WH:Updatedgestational age specific birth weight,crown-heel length,and headcircumference of Chinese newborns.Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed2003, 88:F229–F236.26.Cole TJ,Williams AF,Wright CM:Revised birth centiles for weight,lengthand head circumference in the UK-WHO growth charts.Ann Hum Biol2011,38:7–11.27.Salomon LJ,Bernard JP,Ville Y:Estimation of fetal weight:reference rangeat20–36weeks’gestation and comparison with actual birth-weightreference range.Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol2007,29:550–555.28.Cole TJ,Freeman JV,Preece MA:British1990growth reference centiles forweight,height,body mass index and head circumference fitted bymaximum penalized likelihood.Stat Med1998,17:407–429.29.Gibbons K,Chang A,Flenady V,Mahomed K,Gardener G,Gray PH:Validation and refinement of an Australian customised birthweightmodel using routinely collected data.Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol2010,50:506–511.30.Ogawa Y,Iwamura T,Kuriya N,Nishida H,Takeuchi H,Takada M:Birth sizestandards by gestational age for Japanese neonates.Acta Neonat Jpn1998,34:624–632.31.Storms MR,Van Howe RS:Birthweight by gestational age and sex at arural referral center.J Perinatol2004,24:236–240.32.Romano-Zelekha O,Freedman L,Olmer L,Green MS,Shohat T:Should fetalweight growth curves be population specific?Prenat Diagn2005,25:709–714.33.Ooki S,Yokoyama Y:Reference birth weight,length,chest circumference,and head circumference by gestational age in Japanese twins.J Epidemiol2003,13:333–341.34.Vergara G,Carpentieri M,Colavita C:Birthweight centiles in preterminfants.A new approach.Minerva Pediatr2002,54:221–225.35.Bernstein IM,Mohs G,Rucquoi M,Badger GJ:Case for hybrid“fetal growthcurves”:a population-based estimation of normal fetal size acrossgestational age.J Matern Fetal Med1996,5:124–127.36.Ramos F,Perez G,Jane M,Prats R:Construction of the birth weight bygestational age population reference curves of Catalonia(Spain):Methods and development.Gac Sanit2009,23:76–81.37.Visser GH,Eilers PH,Elferink-Stinkens PM,Merkus HM,Wit JM:New Dutchreference curves for birthweight by gestational age.Early Hum Dev2009, 85:737–744.38.Roberts C,Mueller L,Hadler J:Birth-weight percentiles by gestational age,Connecticut1988–1993.Conn Med1996,60:131–140.39.Zhang X,Platt RW,Cnattingius S,Joseph KS,Kramer MS:The use ofcustomised versus population-based birthweight standards in predicting perinatal mortality.BJOG2007,114:474–477.40.Gielen M,Lindsey PJ,Derom C,Loos RJ,Souren NY,Paulussen AD,ZeegersMP,Derom R,Vlietinck R,Nijhuis JG:Twin-specific intrauterine‘growth’charts based on cross-sectional birthweight data.Twin Res Hum Genet2008,11:224–235.41.Monroy-Torres R,Ramirez-Hernandez SF,Guzman-Barcenas J,Naves-SanchezJ:[Comparison between five growth curves used in a public hospital].Rev Invest Clin2010,62:121–127.42.Blair EM,Liu Y,de Klerk NH,Lawrence DM:Optimal fetal growth for theCaucasian singleton and assessment of appropriateness of fetal growth:an analysis of a total population perinatal database.BMC Pediatr2005,5:13. 43.Carrascosa A,Yeste D,Copil A,Almar J,Salcedo S,Gussinye M:[Anthropometric growth patterns of preterm and full-term newborns(24–42weeks’gestational age)at the Hospital Materno-Infantil Valld’Hebron(Barcelona)(1997–2002].An Pediatr(Barc)2004,60:406–416. 44.Rousseau T,Ferdynus C,Quantin C,Gouyon JB,Sagot P:[Liveborn birth-weight of single and uncomplicated pregnancies between28and42weeks of gestation from Burgundy perinatal network].J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod(Paris)2008,37:589–596.45.Polo A,Pezzotti P,Spinelli A,Di LD:Comparison of two methods forconstructing birth weight charts in an Italian region.Years2000–2003.Epidemiol Prev2007,31:261–269.46.Oken E,Kleinman KP,Rich-Edwards J,Gillman MW:A nearly continuousmeasure of birth weight for gestational age using a United Statesnational reference.BMC Pediatr2003,3:6.47.Montoya-Restrepo NE,Correa-Morales JC:[Birth-weight curves].Rev SaludPublica(Bogota)2007,9:1–10.48.Dollberg S,Haklai Z,Mimouni FB,Gorfein I,Gordon ES:Birth weightstandards in the live-born population in Israel.Isr Med Assoc J2005,7:311–314.49.Kierans WJ,Kendall PRW,Foster LT,Liston RM,Tuk T:New birth weight andgestational age charts for the British Columbia population.BC Medical J 2006,48:28–32.50.Uehara R,Miura F,Itabashi K,Fujimura M,Nakamura Y:Distribution of birthweight for gestational age in Japanese infants delivered by cesareansection.J Epidemiol2011,21:217–222.51.Lipsky S,Easterling TR,Holt VL,Critchlow CW:Detecting small forgestational age infants:the development of a population-basedreference for Washington state.Am J Perinatol2005,22:405–412.52.Niklasson A,Albertsson-Wikland K:Continuous growth reference from24th week of gestation to24months by gender.BMC Pediatr2008,8:8.53.Alexander GR,Kogan MD,Himes JH:1994–1996U.S.singleton birthweight percentiles for gestational age by race,Hispanic origin,andgender.Matern Child Health J1999,3:225–231.54.Davidson S,Sokolover N,Erlich A,Litwin A,Linder N,Sirota L:New andimproved Israeli reference of birth weight,birth length,and headcircumference by gestational age:a hospital-based study.Isr Med Assoc J 2008,10:130–134.55.Kato N,A:[Reference birthweight for multiple births in Japan].NihonKoshu Eisei Zasshi2002,49:361–370.56.Braun L,Flynn D,Ko CW,Yoder B,Greenwald JR,Curley BB,Williams R,Thompson MW:Gestational age-specific growth parameters for infants born at US military hospitals.Ambul Pediatr2004,4:461–467.57.Thomas P,Peabody J,Turnier V,Clark RH:A new look at intrauterinegrowth and the impact of race,altitude,and gender.Pediatrics2000,106:E21.58.World Health Organization:The WHO Child Growth Standards.http://www.who.int/childgrowth/standards/en/.59.Kuczmarski RJ,Ogden CL,Guo SS,Grummer-Strawn LM,Flegal KM,Mei Z,Wei R,Curtin LR,Roche AF,Johnson CL:2000CDC Growth Charts for the United States:methods and development.Vital Health Stat2002,11:1–190.60.Hutcheon JA,Platt RW:The missing data problem in birth weightpercentiles and thresholds for“small-for-gestational-age”.Am J Epidemiol 2008,167:786–792.61.Sauer PJ:Can extrauterine growth approximate intrauterine growth?Should it?Am J Clin Nutr2007,85:608S–613S.62.Christensen RD,Henry E,Kiehn TI,Street JL:Pattern of daily weightsamong low birth weight neonates in the neonatal intensive care unit:data from a multihospital health-care system.J Perinatol2006,26:37–43.63.Valentine CJ,Fernandez S,Rogers LK,Gulati P,Hayes J,Lore P,Puthoff T,Dumm M,Jones A,Collins K,Curtiss J,Hutson K,Clark K,Welty SE:Early。

最新使用世界卫生组织(WHO)的生长曲线图

使用世界卫生组织(WHO)的生长曲线图成长不仅是营养的结果,还是遗传因素的结果。

种族会影响孩子的成长模式,因此有些国家有他们自己的生长曲线图。

不过,世界卫生组织(WHO)的生长曲线图用得最普遍,并被认为是全世界的标准。

了解更多关于:»怎样进行测量»怎样将测量应用到生长曲线图中怎样进行测量0-24 月龄的孩子进行的典型测量包括:•头围•身长•体重测量应定期进行,以观察可靠的趋势。

建议的测量时间间隔包括:•婴儿(0-12 月龄):每2 个月•幼儿:分别在15, 18, 24 和30 月龄• 3 岁以上:每年点击这里获取详细的测量时间表。

头围头围是在孩子头部最大部分进行的测量。

这种测量通常为0-3 岁的孩子进行。

测量时应当使用不可拉伸的卷尺。

卷尺通常是可弯曲的金属量尺。

测量时,卷尺尽可能紧贴着头部最宽围度缠绕。

通常,此部位在前额眉毛上方1-2 指宽到后脑勺最突出的部分。

测量三次,取精确到0.1 厘米的最大测量值。

在孩子生命的早期,头围是一种很重要的测量,因为它间接地反映大脑尺寸和发育。

几乎所有的大脑发育都在两岁以前,因此绘制的头部生长曲线可以作为幼儿大脑健康的通用指标。

了解关于头围-年龄生长曲线图。

身长身长是为不足24 月龄的婴儿进行的线性测量。

24 到36 月龄的孩子,如果无法独立站立,也可以进行身长测量(代替身高)。

身长是在孩子卧位(平躺)时测量的。

测量身长最准确的方法是使用校准的身长量板。

身长量板应当有一块与板表面垂直的固定头部挡板和一块可移动的足板。

测量时,将孩子平放在板上,头靠着固定挡板。

确定孩子没有穿鞋或戴帽子。

有个助手也许可以帮助保持孩子不动并在板中间。

让孩子的腿伸直,调整活动足板,使孩子的脚底靠着足板。

精确到0.1 厘米记录身长。

身长是孩子营养状况的一个重要决定因素。

如果孩子长期营养不良,可能会表现出身长增长缓慢。

了解关于身长-年龄生长曲线图。

体重体重是在整个生命期都需要进行的测量,以帮助确定当前的营养状况和趋势。

青春期生长发育

3期 10~13 乳房和乳晕继续 阴毛分布覆盖 生长速度达高峰,

增大,乳房、乳 会阴部

阴道粘膜增厚角

晕在同一平面上

化,出现腋毛

4期 13~15 乳晕第二次凸出 阴毛增多变粗 月经初潮(在3 于乳房丘状平面 弯曲,分布广, 期或4期时)生 成倒三角形 长

5期

>15 成熟期乳房,乳 阴毛成人型, 骨骺闭合生长停

女 9~11岁 11~13岁 6~8cm 9~10cm 25cm

男 11~13岁 13~15岁 7~9cm 10~12cm 28cm

正是由于男女青少年身 高、体重等指标生长突增年 龄和幅度的性别差异,男女 青少年身高、体重的生长曲 线出现两次交叉的现象。

研究青春突增期开始的时间有种方法为逐人计 算高峰年龄法,即以身高年增长速度最高的3 个相邻年龄组为快速生长期(突增期),其中间年 龄即为生长发育高峰年龄。

青春期发育

本文档后面有精心整理的常用PPT编辑图标,以提高工作效率

学习目标

1.掌握青春期发育相关概念。 2.熟悉青春期男女的性征分期; 正常青春发育生理、正常青春发育 期体格体态的变化及生殖器官、第 二性征的发育特点。 3.了解青春发育的机制及神经、 内分泌调控特点。

生长发育的一般规律

复习

❖ 一、生长发育具有阶段性和连续性 ❖ 二、生长发育的速度具有不均衡性 ❖ 三、各系统生长模式的时间顺序性

任弘等采用此方法研究发现生长高峰年龄的 个体差异很大,身高生长高峰年龄(PHA)并非集 中在某一年龄,而是分散在几个年龄上。男生出 现PHA人数最多的是在13岁(34.65%)、女生 在12岁(33.5%)。体重出现生长高峰最多的年 龄组为男生14岁、女生13岁,比1985、1995 年的调查结果晚1~2岁。

7岁以下儿童生长标准生长曲线

7岁以下儿童生长标准生长曲线儿童的生长发育是每个家庭都关注的重要问题,特别是对于7岁以下的儿童,其生长发育状况更是家长和医生密切关注的重点。

为了评估孩子的生长情况是否正常,专家们根据大量的调查和研究数据,制定了一套生长曲线标准,以此来参考孩子的体重和身高是否与同龄儿童相符合。

本文将详细介绍7岁以下儿童的生长标准生长曲线。

1. 生长曲线的意义生长曲线是根据大型人群的数据样本得出的曲线图,反映了同龄儿童的平均生长情况。

通过将孩子的身高、体重、头围等测量数据与生长曲线进行比对,可以帮助家长和医生判断孩子的生长状况是否正常。

如果孩子的生长曲线偏离正常范围,可能意味着存在潜在的健康问题,需要进一步关注和处理。

2. 世界卫生组织生长标准世界卫生组织(WHO)制定了一套被广泛采用的儿童生长标准,被用于评估0-5岁儿童的生长情况。

该标准以多国健康儿童的数据为基础,分别制定了体重、身高和头围三个方面的生长曲线。

家长可以将自己孩子的测量数据与该标准进行比对,了解孩子的生长情况是否符合预期。

3. 中国儿童生长标准除了世界卫生组织标准外,中国也有自己的儿童生长标准。

中国儿童生长标准是基于国内大规模调查数据进行统计分析,制定了相应的生长曲线。

与世界卫生组织标准相比,中国儿童生长标准更贴近本国儿童的生长情况,并根据不同地区、性别的特点进行了区分。

家长在评估孩子生长情况时,可以参考中国儿童生长标准,更准确地了解孩子的生长状态。

4. 生长曲线的检测和应用家长和医生可以将孩子的身高、体重等测量数据绘制成生长曲线图,将其放在生长曲线标准图上进行比对。

根据曲线的走势,可以评估孩子的生长速度和状态,了解孩子的生长潜力和需求。

同时,生长曲线还可以帮助家长和医生制定合理的膳食和运动计划,以促进健康生长发育。

5. 孩子生长曲线的变化需要注意的是,孩子的生长曲线并非一成不变的。

在一定的阶段内,孩子的生长速度会发生变化,而生长曲线也会随之调整。

小孩身高体重标准

小孩身高体重标准

根据世界卫生组织(WHO)提供的数据,以下是关于小孩身

高体重标准的一些基本知识。

儿童的身高和体重是衡量他们生长和发育情况的重要指标。

身高和体重的正常范围可以通过生长曲线图来确定,这是根据大量儿童的数据绘制的图表。

以下是儿童身高和体重的一些标准:

1. 出生时:新生儿的平均身高为50cm至52cm,平均体重为

2.8kg至

3.4kg。

这些数值可以作为新生儿身高和体重的正常范围,但确切数值可能因个体差异而有所不同。

2. 1岁时:一岁的婴儿平均身高为70cm至75cm,平均体重为8.5kg至12kg。

这是儿童生长最快的时期之一。

3. 3岁时:三岁的孩子平均身高为90cm至100cm,平均体重

为12kg至18kg。

从一岁到三岁之间,孩子的身高和体重增长

较为稳定。

4. 学龄期:到了学龄期,每个孩子的身高和体重发展速度可能有所不同。

通常情况下,男孩子的身高和体重会超过女孩子。

请注意,这些数值只是一般的参考范围。

正常的生长和发育速度因个体差异、遗传因素和环境因素等各种因素而有所不同。

如果家长担心孩子的身高或体重发育有异常情况,应咨询儿科医生进行评估和建议。

要保持孩子的健康成长,除了注意正常的身高和体重发展外,还应有良好的营养饮食和适当的运动。

定期体检也是监测孩子生长发育的重要方法。

总的来说,孩子的身高和体重是他们生长和发育情况的重要指标。

通过养成良好的饮食和运动习惯,以及定期进行体检,我们可以帮助孩子健康成长,并监测他们是否符合正常的身高和体重标准。

使用世界卫生组织(WHO)的生长曲线图

使用世界卫生组织(WHO)得生长曲线图成长不仅就是营养得结果,还就是遗传因素得结果。

种族会影响孩子得成长模式,因此有些国家有她们自己得生长曲线图。

不过,世界卫生组织(WHO)得生长曲线图用得最普遍,并被认为就是全世界得标准。

了解更多关于:»怎样进行测量»怎样将测量应用到生长曲线图中怎样进行测量0-24 月龄得孩子进行得典型测量包括:•头围•身长•体重测量应定期进行,以观察可靠得趋势。

建议得测量时间间隔包括:•婴儿(0-12 月龄):每2 个月•幼儿:分别在15, 18, 24 与30 月龄• 3 岁以上:每年点击这里获取详细得测量时间表。

头围头围就是在孩子头部最大部分进行得测量。

这种测量通常为0-3 岁得孩子进行。

测量时应当使用不可拉伸得卷尺。

卷尺通常就是可弯曲得金属量尺。

测量时,卷尺尽可能紧贴着头部最宽围度缠绕。

通常,此部位在前额眉毛上方1-2 指宽到后脑勺最突出得部分。

测量三次,取精确到0.1 厘米得最大测量值。

在孩子生命得早期,头围就是一种很重要得测量,因为它间接地反映大脑尺寸与发育。

几乎所有得大脑发育都在两岁以前,因此绘制得头部生长曲线可以作为幼儿大脑健康得通用指标。

了解关于头围-年龄生长曲线图。

身长身长就是为不足24 月龄得婴儿进行得线性测量。

24 到36 月龄得孩子,如果无法独立站立,也可以进行身长测量(代替身高)。

身长就是在孩子卧位(平躺)时测量得。

测量身长最准确得方法就是使用校准得身长量板。

身长量板应当有一块与板表面垂直得固定头部挡板与一块可移动得足板。

测量时,将孩子平放在板上,头靠着固定挡板。

确定孩子没有穿鞋或戴帽子。

有个助手也许可以帮助保持孩子不动并在板中间。

让孩子得腿伸直,调整活动足板,使孩子得脚底靠着足板。

精确到0.1 厘米记录身长。

身长就是孩子营养状况得一个重要决定因素。

如果孩子长期营养不良,可能会表现出身长增长缓慢。

了解关于身长-年龄生长曲线图。

体重体重就是在整个生命期都需要进行得测量,以帮助确定当前得营养状况与趋势。

第二章儿童少年身体发育-PPT

❖ WHO关于5~17岁儿童少年体力活动建议 为增进心肺、肌肉与骨骼健康,减少慢性非传

染性疾病风险,建议:

①5~17岁儿童少年应每天累积至少60min中等 到高强度得体力活动。

②大于60min得体力活动可以提供更多得健康效 应。

③大多数日常体力活动应该就是有氧运动。

④每周至少应进行3次高强度体力活动,包括强 壮肌肉与骨骼得活动等。

质下中枢(纹状体、杏仁核等)功能活跃 ,两者发育得不平衡易 导致青少年发生冒险行为 (risk-tቤተ መጻሕፍቲ ባይዱking behavior)与健康危害行为(health risk behavior)

随年龄增长而扩大。青春期LBM得变化主要就是 含水量逐年减少,女孩得总体水量仍高于男孩;1018岁男生总体水占FFM得75%,女生为77%。

体成分发育得年龄特征

❖ 其她体成分年龄性别特征

10-18岁时男女细胞外水占总体水(TBW)出现差异,男孩 TBW占FFM得比例小于女孩。 男女体钙含量得改变与生长突增关系密切,男孩总体钙得均 值13-14岁增加达35%;女孩11-12岁增加最多约40%。

体型就是个体当前得形态表型,就是可以观察 到得外在得形态结构,它不考虑身材大小,就是对身 体形状与相对组成成分得描述,体型可以发生变化。

将三维空间得体型点投影到二维平面上,就得到 平面体型图(somatochart)。

❖ 体能 体能就是指人体具备得能胜任日常工作与学习而

不感到疲劳,同时有余力能充分享受休闲娱乐生活, 又可应付突发紧急状况得能力。

三、身体比例变化

▪ 第一类反映身体各横截面指标得相互关系,如:身高胸 围指数(胸围/身高)、肩盆宽指数(肩宽/盆宽)、BMI等 。

▪ 第二类反映个体下肢长度与线形高度(如身高)间得比 例关系。坐高/身高指数 、下肢长指数Ⅰ 、下肢长指 数Ⅱ。

青春期生长发育PPT课件

长突增。生长突增即生长速度在童年期比较平稳的基础上,突 不完全性性早熟(incomplete precocious puberty),也称部分性早熟。

二是通过对其它内分泌腺自主神经的支配进行调节。 肾上腺(分泌肾上腺素)

乳芽期、乳晕和乳头增大隆起,有乳核可触及 进入青春期后,随着身体的发育、性意识也开始萌动,常表现为从初期的与异性疏远,到逐渐愿意与异性接近,或对异性产生朦胧的

瘦高体型。 依恋,这些都是正常的心理变化。

青春期心理发展的主要矛盾体现在哪些方面 ?

有学者对120名健康的儿童进行生长发育追踪观 察9年发现,不同成熟类型女孩身高突增起始年龄、 停止年龄与高峰年龄存在一致性,即突增开始年龄早 突增结束年龄也早,反之亦晚。

器胡官须不 增发多育,睾。丸最大直径>4.

肾外上生腺 殖(器分包泌括肾阴上阜腺、素大)小阴唇、阴蒂、前庭和会阴。

因男此性按 的年性龄腺的是生睾长丸速,度女不性能的确性切腺反是映卵青巢春,期它生们长分突别增是的男特女征生。殖系统的最重要器官,主要功能是产生精子或卵子和分泌性激素。

肾一上、腺影(响分生泌长肾发上育腺的素激)素

育肾障上碍 腺。(分泌肾上腺素)

真2.性自性我早意熟识(迅tr猛ue增pr长ec与oc社io会us成p熟ub相er对ty)迟缓的矛盾

从甲胎状儿 腺期功开能始低,下中症枢(hy神po经th对yr性oid发is育m就) 一直保持着抑制作用,使下丘脑对GnRH的分泌处于“青春静止期” (juvenile pause),内外生殖

研究青春突增期开始的时间有种方法为“逐人计 算高峰年龄法”,即以身高年增长速度最高的3个相 邻年龄组为快速生长期(突增期),其中间年龄即为生 长发育高峰年龄。

体格生长评价

头围

胸围

7

二、青春期体格生长

第二生长高峰(PHV): 女孩8~9cm/year (9~11岁后) 男孩9~10cm/year(11~13岁后) 性别差异:男孩PHV晚于女孩2年 个体差异 第二高峰期身高增加值约为最终身高的 15%

二、体格生长的评价

(一)常用的统计学方法

生长曲线图举例:(男童身高)

190 180 170 160 150 140 130 120 110 100 90 80 70 60 50

P 97

Boys:height

+2SD

P 50

P3

-2SD

2

4

6

Age ( year )

8

10

12

14

16

18

生 长 曲 线 图

(二)结果判断

界值点的选择(cut-off point)

坐高: >3岁坐位测量

顶臀长的测量

坐高的测量

坐高与身高(顶臀长/身长)比值

1.00 0.90 0.80 0.70 0.60 0.50 3m 12m 2y 6y

青春期后

男孩

女孩

坐高与身高(顶臀长/身长)比值的 意义:判断矮小类型 匀称性矮小 (家族性、垂体性侏儒)

矮小

非匀称性矮小 (甲低、软骨发育不全)

(三)评价内容

发育水平 生长速度 匀称度

依据儿童体格生长规律来判断其生长状况

发育水平 (Development Level)

将某一年龄时点所获得的某一项体格生 长测量值(横断面调查)与参考人群值 比较,得到该儿童在同质人群中(同年 龄、同性别)所处的位置 。但不能预示 其生长趋势

世卫组织最新标准 - (0-5岁)体重生长曲线图 ~ 身高生长曲线图 ~ BMI生

世卫组织最新标准 - (0-5岁)体重生长曲线图 ~ 身高生长曲线图 ~ BMI生长曲线图世界卫生组织的最新标准是完全根据母乳宝宝的生长情况制定的。

而我国的标准是综合国内不同地区和不同喂养分方式的数据统计出来的。

但这样的数据并不能说明它更正确,而恰恰会由于混合或人工喂养宝宝的因素使数据偏高。

这些新指标是基于8440名母乳喂养的孩子的生长发育状况做出的。

与吃母乳的婴幼儿比起来,吃配方奶的孩子体重比吃母乳的孩子要增长得快些。

而“世卫组织”旧的有关婴幼儿的成长发育指标却是根据吃配方奶的孩子的发育情况制定的,这就意味着这一套标准存在着重大缺陷。

从1997年到2003年间,世界卫生组织对包括巴西等6个国家的孩子进行了跟踪调查。

这些孩子来自巴西、加纳、印度、挪威、阿曼和美国等6个不同的国家,身体都很健康,且他们的母亲都不吸烟,对孩子的照顾也非常周到。

而之前的指标只是取单独一个国家的儿童为样本(也就是美国儿科学会公布的美国婴幼儿生长发育曲线)。

男宝BMI生长曲线图女宝BMI生长曲线图新的婴幼儿生长发育指标中还包含了身体质量指数(BMI=体重(公斤)÷身高(米)的平方,单位为公斤/平方米),这是WHO首次在婴幼儿生长发育指标中引入此项指标。

BMI为评估体重与身高比例提供了工具,对于监控孩子的肥胖症非常有效。

它是评估儿童健康的一个重大革新。

男宝宝体重生长曲线图专家认为,新指标的发表不会给中国孩子生长发育情况带来大影响。

我国每10年都要在北部、中部、南部各选三地,对0-18岁儿童和青少年的身高、体重等情况进行调查统计,并综合了各种喂养方式,得出我国儿童的身高、体重等指标的参照值。

用生长曲线检测孩子的身高、体重的发育,比起简单用一个数字断定孩子是高是胖要更科学。

使用方法如下:1、做顺时记录。

每个月为孩子测量一次身高、体重,把测量结果描绘在生长曲线图上(不要在孩子生病期间测量),连成一条曲线。

如果孩子的生长曲线一直在正常值范围内(3号线到-3号线之间)匀速顺时增长就是正常的。

男孩各年龄段身高体重标准表

男孩各年龄段身高体重标准表了解男孩在不同年龄段的身高和体重标准是非常重要的,这有助于你关注男孩的生长发育,及时发现任何可能存在的健康问题。

以下是一份男孩各年龄段身高体重标准表,包括身高体重比例标准、身高标准、体重标准和身高体重曲线图。

一、身高体重比例标准身高体重比例标准是评估男孩生长发育状况的重要指标之一。

一般来说,男孩的身高与体重的比例呈直线上升趋势,但也有一定的波动。

以下是男孩身高与体重的比例标准:1-2岁:身高比例约为1.5倍,体重比例约为2倍。

3-5岁:身高比例约为1.3倍,体重比例约为1.7倍。

6-9岁:身高比例约为1.2倍,体重比例约为1.5倍。

10-12岁:身高比例约为1.1倍,体重比例约为1.3倍。

二、身高标准男孩的身高在各个年龄段都有一定的标准。

以下是男孩各年龄段的身高标准(单位:厘米):1岁:75-80厘米2岁:85-90厘米3岁:95-100厘米4岁:105-110厘米5岁:115-120厘米6岁:125-130厘米7岁:135-140厘米8岁:145-150厘米9岁:155-160厘米10岁:165-170厘米三、体重标准男孩的体重也随年龄增长而增加。

以下是男孩各年龄段的体重标准(单位:千克):1岁:9-10千克2岁:12-13千克3岁:15-16千克4岁:18-20千克5岁:22-24千克6岁:26-28千克7岁:30-32千克8岁:34-36千克9岁:38-40千克10岁:42-44千克四、身高体重曲线图为了更直观地了解男孩的生长发育情况,可以绘制身高和体重的曲线图。

将男孩在不同年龄段的身高和体重数据记录在图表上,并将这些点连接起来,就可以得到身高和体重的曲线图。

通过观察曲线图,可以判断男孩的生长发育是否正常。

如果曲线偏离了正常范围,可能意味着存在健康问题,需要咨询医生或专业人士的建议。

who身高体重标准

who身高体重标准WHO身高体重标准。

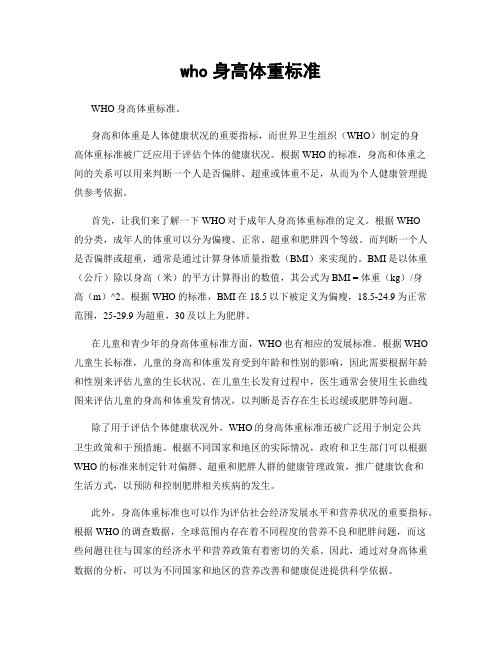

身高和体重是人体健康状况的重要指标,而世界卫生组织(WHO)制定的身高体重标准被广泛应用于评估个体的健康状况。

根据WHO的标准,身高和体重之间的关系可以用来判断一个人是否偏胖、超重或体重不足,从而为个人健康管理提供参考依据。

首先,让我们来了解一下WHO对于成年人身高体重标准的定义。

根据WHO的分类,成年人的体重可以分为偏瘦、正常、超重和肥胖四个等级。

而判断一个人是否偏胖或超重,通常是通过计算身体质量指数(BMI)来实现的。

BMI是以体重(公斤)除以身高(米)的平方计算得出的数值,其公式为BMI = 体重(kg)/身高(m)^2。

根据WHO的标准,BMI在18.5以下被定义为偏瘦,18.5-24.9为正常范围,25-29.9为超重,30及以上为肥胖。

在儿童和青少年的身高体重标准方面,WHO也有相应的发展标准。

根据WHO 儿童生长标准,儿童的身高和体重发育受到年龄和性别的影响,因此需要根据年龄和性别来评估儿童的生长状况。

在儿童生长发育过程中,医生通常会使用生长曲线图来评估儿童的身高和体重发育情况,以判断是否存在生长迟缓或肥胖等问题。

除了用于评估个体健康状况外,WHO的身高体重标准还被广泛用于制定公共卫生政策和干预措施。

根据不同国家和地区的实际情况,政府和卫生部门可以根据WHO的标准来制定针对偏胖、超重和肥胖人群的健康管理政策,推广健康饮食和生活方式,以预防和控制肥胖相关疾病的发生。

此外,身高体重标准也可以作为评估社会经济发展水平和营养状况的重要指标。

根据WHO的调查数据,全球范围内存在着不同程度的营养不良和肥胖问题,而这些问题往往与国家的经济水平和营养政策有着密切的关系。

因此,通过对身高体重数据的分析,可以为不同国家和地区的营养改善和健康促进提供科学依据。

总的来说,WHO的身高体重标准对于评估个体健康状况、制定公共卫生政策以及评估社会经济发展水平都具有重要意义。

中国0-18岁儿童、青少年身高、体重的标准化生长曲线表

中国0-18岁儿童、青少年身高、体重的标准化生长曲线表1. 引言1.1 概述本篇文章旨在介绍中国0-18岁儿童、青少年身高和体重的标准化生长曲线表。

随着社会发展和家庭条件的改善,人们对孩子健康成长的重视程度也逐渐增加。

而正确评估孩子的身高和体重发育情况对于及早发现营养不良、疾病风险以及提供合理的干预措施至关重要。

因此,建立一个基于中国实际情况的标准化生长曲线表对于医生、家长以及教育工作者都具有重要意义。

1.2 文章结构本文主要分为以下几个部分:- 引言:对文章进行简单概述,介绍研究的目的和意义。

- 身高与体重的重要性:阐述身高和体重在评估健康指标、发育情况以及疾病风险方面的重要性。

- 儿童、青少年身高、体重的标准化生长曲线表概述:解释并介绍儿童、青少年身高、体重标准化生长曲线表背后相关定义、知识以及数据来源和采集方法。

- 0-18岁儿童身高、体重标准化生长曲线表解读与分析结果:对女孩和男孩身高、体重曲线表进行详细解读,并对不同年龄段的比较进行分析。

- 结论:总结研究的意义和应用价值,并展望未来可以在该领域进行的进一步研究。

1.3 目的本文的目的是介绍中国0-18岁儿童、青少年身高和体重的标准化生长曲线表,旨在提供科学准确的工具,帮助医生、家长和教育工作者有效评估儿童的健康状况,以便及时发现问题并采取相应措施。

通过这样的标准化生长曲线表,我们可以更好地了解中国儿童发育情况,为他们提供适当的营养支持和关怀。

此外,该曲线表还可以用于科学研究,在人类体格发育方面做出更多贡献。

以上就是文章"1. 引言"部分内容的详细介绍。

2. 身高与体重的重要性2.1 健康指标身高和体重是儿童、青少年健康状况的重要指标之一。

合适的身高和体重可以反映出孩子们的生长发育是否正常,以及他们的整体健康状态。

对于0-18岁的儿童和青少年来说,身高增长是一个与年龄相关的生理过程,可以说明他们是否处于正常范围内。

2.2 发育评估通过对儿童、青少年的身高和体重进行监测和评估,可以及时发现生长迟缓、肥胖等问题,并采取相应的干预措施。

儿童少年卫生学第8版 第七章 生长发育调查与评价

第一节 生长发育调查

(三)生长发育调查应用

4. 制定参考标准

(2)生长发育标准:①可看成正常值的一部分;所选样本应尽量接近“理想人群”。②全国性评价标准和地区性评价标准各有优势,应根据目的选择、配合使用。③尽量使用先进的统计方法(如LMS法),使选 定的界值点(cut-offs)尽量精确。④能称之为“标准”的正常值,其界值点都应有临床症状为依据。

第一节 生长发育调查

(一)生长发育调查设计

2. 监测设计 指对某地区、某群体某些生长发育指标的连续收集、整理、分析过程。是生长发育调查的另一重要类型。 (1)明确监测目的。 (2)确定监测人群:可在学校、社区、医院等不同基础上对学龄儿童少年进行人群监测(population-based surveillance)。 (3)稳定监测方法:监测体系固定,指标简便、易行。 (4)保证质量控制:保障结果的可比性。 (5)结果反馈与应用:根据监测结果及时制定和调整干预措施。

第一节 生长发育调查

(五)生长发育调查的伦理学

1. 伦理审批 向当地(或高校)伦理委员会提交申请报告。 2. 知情同意 以口头或书面(尤其人群干预试验)形式,取得对象(14岁以下儿童征询家长意见)的参与承诺。 3. 儿童少年的禁忌 凡对实验对象可能造成伤害的试剂或药品(如放射性核素)不得用于儿童少年。 4. 正确对待对照组。

第一节 生长发育调查

(三)生长发育调查应用

1. 描述水平 描述生长发育水平和现状。还有助于: (1)筛查和诊断生长发育障碍。 (2)评价营养和生活环境等因素对生长发育的影响。 (3)提供保健干预措施。 2. 反映动态 对生长发育全过程进行连续追踪观察可揭示儿童生长发育的规律性和特点,分析生长长期趋势。 3. 评价队列效应 对不同年龄段群体生长发育进行研究可反映出相应阶段的社会变化与时代特征。

2013fenton曲线

2013fenton曲线

Fenton曲线是2013年由国外专家根据胎儿在子宫内生长规律制定的早产儿生长曲线图,也是中国医院常用的监测早产儿生长发育状

况的标准曲线。

Fenton曲线反映了从胎龄22~50周(即矫正胎龄足月后10周)的胎儿及新生儿体重、身长、头围等体格指标的变化,可用于早产儿

生长发育状况的监测与评估。

Fenton曲线分为男孩和女孩两种曲线,分别用于评价男宝宝和女宝宝的发育情况。

每张曲线图包含身长、头围和体重曲线三大板块,

分别用于评价身长、头围、体重发育情况。

曲线图内含5条曲线,分

别代表第3、第10、第50、第90、第97百分位。

Fenton曲线可根据宝宝胎龄、体重、身长、头围等数据计算其当下生长状况处于同龄儿的什么水平,从而帮助医生和家长制定喂养方案。