Restorative Justice and three individual theories of crime

公正照人心的英语作文

Justice is a fundamental principle that underpins the social fabric of any civilized society.It is the cornerstone of fairness and equality,ensuring that every individual is treated with respect and dignity.In this essay,we will delve into the concept of justice,its importance,and how it shapes our lives.The Essence of JusticeJustice is often viewed as the impartial administration of the law,without favoritism or prejudice.It is about ensuring that every person receives what they are rightfully entitled to,whether it be punishment for wrongdoing or reward for good deeds.The essence of justice lies in its ability to maintain social order and promote harmony.Importance of Justice1.Social Harmony:Justice plays a crucial role in maintaining social harmony.When people believe that the system is fair,they are more likely to accept the outcomes of legal and social processes,reducing conflict and promoting cooperation.2.Trust in Institutions:A just society fosters trust in its institutions.People are more willing to abide by laws and regulations when they see that these are enforced impartially.3.Economic Stability:Justice is also vital for economic stability.Fair trade practices, transparent regulations,and equitable distribution of resources contribute to a healthy economy where everyone has a fair chance to succeed.4.Moral Integrity:On a personal level,justice is linked to moral integrity.It encourages individuals to act ethically and responsibly,knowing that their actions will be judged fairly.Manifestations of Justice1.Legal Justice:This is the most obvious form of justice,where laws are applied equally to all individuals,regardless of their status or wealth.2.Social Justice:This involves the fair distribution of societal resources and opportunities,ensuring that everyone has access to education,healthcare,and other basic needs.3.Environmental Justice:This is a newer concept that focuses on the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race,color,national origin,or incomewith respect to the development,implementation,and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations,and policies.4.Restorative Justice:This approach to justice focuses on the rehabilitation of offenders through reconciliation with victims and the community at large.Challenges to JusticeDespite its importance,justice faces numerous challenges:1.Corruption:This undermines the fairness of legal systems,leading to unequal treatment of individuals.2.Discrimination:Prejudice based on race,gender,or other factors can lead to injustice, where certain groups are systematically disadvantaged.ck of Access:In some cases,people may not have the means or knowledge to access justice,particularly in legal matters.4.Power Imbalances:Those with more power or resources can sometimes influence outcomes in their favor,distorting the concept of justice.ConclusionJustice is a complex and multifaceted concept that is essential for the functioning of society.It requires constant vigilance and effort to ensure that it is upheld.By promoting justice,we can create a world where everyone has the opportunity to thrive and contribute to the common good.It is our collective responsibility to work towards a more just society,where the light of justice shines brightly for all.。

《德意志联邦共和国少年法院法》英文

《德意志联邦共和国少年法院法》英文The Youth Court Act of the Federal Republic of Germany1. Youth -青少年2. Court -法院3. Act -法令4. Federal -联邦5. Republic -共和国6. Germany -德国1. The Youth Court Act of the Federal Republic of Germany aims to protect the rights and interests of young people.这部德意志联邦共和国少年法院法旨在保护青少年的权益。

2. The court will only handle cases involving young individuals under the age of 18.法院只会处理涉及18岁以下的年轻人的案件。

3. The Act provides guidelines for the treatment and rehabilitation of young offenders.该法令为青少年犯罪者的治疗和康复提供了指导方针。

4. The court ensures that young people have access tolegal representation during the proceedings.法院确保年轻人在诉讼过程中可以获得法律代理人的援助。

5. The Act emphasizes the importance of educational measures rather than punitive measures for young offenders.该法令强调对青少年犯罪者采取教育措施而非惩罚措施的重要性。

6. The court evaluates the individual circumstances of each young offender before making a decision.法院在做出决策前评估了每个青少年犯罪者的个人情况。

正义维护公平的英语作文

Justice is a fundamental concept in society,embodying the principles of fairness, impartiality,and equity.It ensures that every individual is treated equally under the law and that their rights are protected.The pursuit of justice is essential for maintaining social order and fostering a sense of trust among citizens.In an essay on justice and fairness,one might begin by discussing the importance of justice in a democratic society.Democracy thrives on the belief that every citizen has an equal voice and that their rights are safeguarded.Justice is the cornerstone of this belief, ensuring that the law is applied fairly to all individuals,regardless of their social status, wealth,or influence.The essay could then delve into the various aspects of justice,such as distributive justice, which focuses on the fair distribution of resources and opportunities among members of society.This aspect of justice is crucial in reducing inequality and ensuring that everyone has a fair chance to succeed.Procedural justice is another important aspect that the essay could explore.It refers to the fairness of the processes and procedures used in decisionmaking and dispute resolution.A fair process is one that is transparent,consistent,and unbiased,allowing every individual to have their grievances heard and addressed.The essay might also discuss the challenges to achieving justice and fairness in todays world.Factors such as corruption,discrimination,and social biases can hinder the pursuit of justice.It is essential to address these issues through strong legal frameworks, education,and public awareness campaigns to promote a culture of fairness and equality.Moreover,the essay could highlight the role of institutions in upholding justice.Courts, law enforcement agencies,and regulatory bodies play a critical role in ensuring that justice is served.They must operate with integrity and impartiality to maintain public trust and uphold the rule of law.In conclusion,the essay would emphasize the importance of justice and fairness in building a just society.It would call for collective efforts from individuals,institutions, and governments to promote and protect these values.By doing so,we can create a society where everyone is treated with dignity and respect,and their rights are protected, regardless of their background or circumstances.。

和谐社会英语作文

A harmonious society is a concept that has been widely discussed and pursued in modern times.It refers to a society where all aspects are in balance and people live in peace and happiness.Here are some key elements that contribute to building a harmonious society:1.Social Justice:A fair and just legal system is fundamental to a harmonious society.It ensures that everyone is treated equally under the law and that their rights are protected.2.Economic Stability:A stable economy is crucial for the wellbeing of the citizens.It provides job opportunities,reduces poverty,and ensures a decent standard of living for all.cational Opportunities:Access to quality education is a cornerstone of a harmonious society.It empowers individuals,reduces inequality,and fosters a culture of lifelong learning.4.Healthcare Access:Universal healthcare ensures that everyone has access to medical services regardless of their economic status,contributing to a healthier and more productive society.5.Environmental Sustainability:A harmonious society is mindful of its environmental impact.Sustainable practices in energy use,waste management,and conservation are essential for the longterm health of the planet and its inhabitants.6.Cultural Diversity:Embracing cultural diversity and promoting tolerance and understanding among different ethnic and cultural groups can lead to a more inclusive and harmonious society.munity Engagement:Active participation in community activities helps to build social bonds and a sense of belonging,which are vital for social cohesion.8.Political Transparency:Transparent governance and political systems that are accountable to the people foster trust and confidence in the institutions that govern a society.9.Safety and Security:Ensuring public safety and security is a prerequisite for a harmonious society.This includes measures to prevent crime and provide for the safety of all citizens.10.Innovation and Technology:Encouraging innovation and the use of technology candrive economic growth and improve the quality of life for citizens.In conclusion,a harmonious society is one where all members feel valued,safe,and have the opportunity to contribute to and benefit from the collective wellbeing.It is a society that is built on the principles of fairness,equality,and mutual respect.。

公平守正义的英语作文

Justice is a fundamental concept in society,representing the moral and legal principles that ensure fairness and equity.It is the cornerstone of a wellfunctioning and harmonious community.The pursuit of justice is an ongoing process that requires the collective effort of individuals,institutions,and governments.The Importance of JusticeJustice is essential for maintaining social order and ensuring that all individuals are treated equally under the law.It promotes trust in institutions and fosters a sense of security among citizens.Without justice,society would be plagued by chaos and inequality,leading to a breakdown of social cohesion.The Role of Law in Upholding JusticeLaws are established to provide a framework for justice.They are designed to protect the rights of individuals,to punish wrongdoing,and to provide a mechanism for resolving disputes.The enforcement of laws is crucial in ensuring that justice is served.However, the effectiveness of laws depends on their fairness and the impartiality of their application.The Challenge of Achieving JusticeAchieving justice is not always straightforward.There are numerous challenges, including corruption,bias,and the unequal distribution of resources.These factors can undermine the pursuit of justice,leading to a system that favors certain individuals or groups over others.The Role of Individuals in Seeking JusticeIndividuals play a vital role in the quest for justice.By being aware of their rights and the laws that protect them,citizens can hold institutions accountable.They can also engage in advocacy and activism to promote fair policies and practices.The Importance of Education in Promoting JusticeEducation is a powerful tool in the fight for justice.It equips individuals with the knowledge and skills necessary to understand and navigate the complexities of the legal system.Moreover,it fosters critical thinking,enabling people to question and challenge unjust practices.The Role of Technology in Enhancing JusticeIn the modern world,technology plays an increasingly significant role in the pursuit of justice.It can provide greater transparency in legal processes,facilitate access to legal resources,and enable the monitoring of judicial decisions to ensure fairness.The Global Perspective on JusticeJustice is not confined to national boundaries.International law and human rights conventions have been established to promote justice on a global scale.These instruments aim to protect the rights of individuals and to hold states accountable for their actions.ConclusionThe pursuit of justice is an ongoing endeavor that requires vigilance,commitment,and the active participation of all members of society.It is a multifaceted challenge that involves legal,social,and political dimensions.By working together,we can strive to create a world where justice is not just an ideal but a reality for all.。

宪法与法治(英文版)

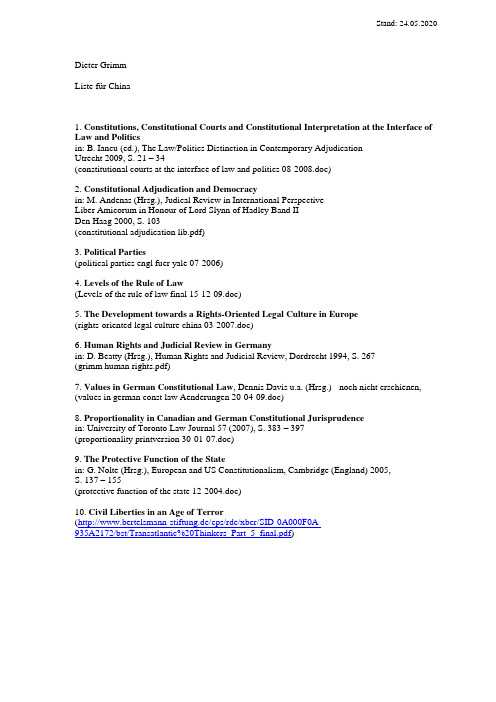

Dieter GrimmListe für China1. Constitutions, Constitutional Courts and Constitutional Interpretation at the Interface of Law and Politicsin: B. Iancu (ed.), The Law/Politics Distinction in Contemporary AdjudicationUtrecht 2009, S. 21 – 34(constitutional courts at the interface of law and politics 08-2008.doc)2. Constitutional Adjudication and Democracyin: M. Andenas (Hrsg.), Judical Review in International PerspectiveLiber Amicorum in Honour of Lord Slynn of Hadley Band IIDen Haag 2000, S. 103(constitutional adjudication lib.pdf)3. Political Parties(political parties engl fuer yale 07-2006)4. Levels of the Rule of Law(Levels of the rule of law final 15-12-09.doc)5. The Development towards a Rights-Oriented Legal Culture in Europe(rights-oriented legal culture china 03-2007.doc)6. Human Rights and Judicial Review in Germanyin: D. Beatty (Hrsg.), Human Rights and Judicial Review, Dordrecht 1994, S. 267(grimm human rights.pdf)7. Values in German Constitutional Law, Dennis Davis u.a. (Hrsg.) - noch nicht erschienen, (values in german const law Aenderungen 20-04-09.doc)8. Proportionality in Canadian and German Constitutional Jurisprudencein: University of Toronto Law Journal 57 (2007), S. 383 – 397(proportionality printversion 30-01-07.doc)9. The Protective Function of the Statein: G. Nolte (Hrsg.), European and US Constitutionalism, Cambridge (England) 2005,S. 137 – 155(protective function of the state 12-2004.doc)10. Civil Liberties in an Age of Terror(http://www.bertelsmann-stiftung.de/cps/rde/xbcr/SID-0A000F0A-935A2172/bst/Transatlantic%20Thinkers_Part_5_final.pdf)Dieter GrimmConstitutions, Constitutional Courts and Constitutional Interpretation at the Interface of Lawand PoliticsI.1. Before the end of World War II constitutional courts or courts with constitutional jurisdiction werea rarity. Although constitutions had been in place long before, a worldwide demand for constitutionaladjudication arose only after the experiences with the many totalitarian systems of the 20th century. The post-totalitarian constitutional assemblies regarded judicial review as the logical consequence ofconstitutionalism. In a remarkable judgment the Israeli Supreme Court said in 1995: "Judicial reviewis the soul of the constitution itself. Strip the constitution of judicial review and you have removed its very life… It is therefore no wonder that judicial re view is now developing. The majority of enlightened democratic states have judicial review… The Twentieth Century is the century of judicial review." (United Mizrahi Bank Ltd. v. Migdal Village, Civil Appeal No. 6821/93, decided 1995). Based on this universal trend the Israeli Court claimed the power of judicial review although it had not been explicitly endowed with it in the constitution.Yet, just as the transition from absolute rule to constitutionalism had modified the relationship between law and politics, this relationship was now modified by the establishment of constitutional courts. As long as law was regarded as being of divine origin politics were submitted to law. Political power derived its authority from the task to maintain and enforce divine law, but did not include the right to make law. When the Reformation undermined the divine basis of the legal order and led to the religious civil wars of the 16th and 17th century the inversion of the traditional relationship between law and politics was regarded as a precondition for the restoration of social peace. The political ruler acquired the power to make law regardless of the contested religious truth. Law became a product of politics. It derived its binding force no longer from God‘s will but from the ruler‘s will. It was henceforth positive law. Eternal or natural law, in spite of its name, was not law, but philosophy.Constitutionalism as it emerged in the last quarter of the 18th century was an attempt to re-establish the supremacy of the law, albeit under the condition that there was no return to divine or eternal law. The solution of the problem consisted in the reflexivity of positive law. Making and enforcing the law was itself subjected to legal regulation. To make this possible a hierarchy had to be established within the legal system. The law that regulated legislation and law-enforcement had to be superior to the law that emanates from the political process. Yet, since there was no return to divine law the higher law was itself the product of a political decision. But in order to fulfil its function of submitting politics to law it needed a source different from ordinary politics. In accordance with the theory that, in the absence of a divine basis of rulership the only possible legitimization of political power is the consent of the governed, this source was found in the people. The people replaced the ruler as sovereign, just as before the ruler had replaced God. But the role of the popular sovereign was limited to enacting the constitution while the exercise of political power was entrusted to representatives of the people who could act only on the basis and within the framework of the constitution.Hence, one can say that the very essence of constitutionalism is the submission of politics to law. This function distinguishes constitutional law from ordinary law in various respects. There is, first, a difference in object. The object of constitutional law is politics. Constitutional law regulates the formation and exercise of political power. The power holders are the addressees of constitutional law. Secondly, constitutional and ordinary law have different sources. Since constitutional law brings forth legitimate political power it cannot emanate from that same power. It is made by or attributed to the people. Consequently, the making of constitutional law differs, thirdly, from the making of ordinarylaw. It is usually a special body that formulates constitutional law and its adoption is subject to a special procedure in which either the people takes the decision or, if a representative body is called upon to decide, a supermajority is required.Fourthly, constitutional law differs from ordinary law in rank. It is higher law. In case of conflict between constitutional law and ordinary law or acts of ordinary law application constitutional law trumps. What has been regulated in the constitution is no longer open to political decision. Insofar, the majority rule does not apply. This does not mean a total juridification of politics. Such a total juridification would be the end of politics and turn it into mere administration. Constitutional law determines who is entitled to take political decisions and which procedural and substantive rules he has to observe in order to give these decisions binding force. But the constitution neither predetermines the input into the constitutionally regulated procedures nor their outcome. It regulates the decision-making process but leaves the decisions themselves to the political process. It is a framework, not a substitute for politics.Finally, constitutional law is characterized by a certain weakness compared to ordinary law. Ordinary law is made by government and applies to the people. If they do not obey government is entitled to use force. Constitutional law, on the contrary, is made by or at least attributed to the people as its ultimate source and applies to government. If the government does not comply with the requirements of constitutional law there is no superior power to enforce it. This weakness may differ in degree, depending on the function of the constitution. Regarding the constitutive function the structure of public power will usually conform to the constitutional arrangement. Regarding its function to regulate the exercise of political power this cannot be taken for granted. The historical and actual evidence is abundant.2. It was this weakness that gave rise to constitutional adjudication, in the United States soon after the invention of constitutionalism, in Europe and other parts of the world only after the collapse of the fascist and racist, socialist and military dictatorships beginning in the 1950s and culminating in the 1990s. Although many of these systems had constitutions their impact was minimal, and invoking constitutional rights could be dangerous to citizens. In the light of this experience constitutional courts were generally regarded as a necessary completion of constitutionalism. If the very essence of constitutionalism is the submission of politics to law, the very essence of constitutional adjudication is to enforce constitutional law vis-à-vis government. This implies judicial review of political acts including legislation. However, constitutional courts or courts with constitutional jurisdiction cannot fully compensate for the weakness of constitutional law. Since the power to use physical force remains in the hands of the political branches of government, courts are helpless when politicians refuse to comply with the constitution or disregard court orders.But apart from this situation, which is exceptional in a well-functioning liberal democracy with a deeply-rooted sense for the rule of law, it makes a difference whether a political system adopts constitutional adjudication or not. Even a government that is generally willing to comply with the constitution will be biased regarding the question what exactly the constitution forbids or requires in a certain situation. Politicians tend to interpret the constitution in the light of their political interests and intentions. In a system without constitutional adjudication usually the interpretation of the majority prevails. In the long run this will undermine the achievement of constitutionalism. By contrast, in a system with constitutional adjudication an institution exists that does not pursue political intentions, is not subject to election and specializes on constitutional interpretation in a professional manner. It is thus less biased and can uphold constitutional requirements vis-à-vis the elected majority. Even more important is the preventive effect of constitutional adjudication. The mere existence of a constitutional court causes the political majority to raise the question of the constitutionality of a political measure quite early in the political process and in a more neutral way. It observes its own political plans through the eyes of the constitutional court.Kelsen, whom the Israeli Supreme Court quotes approvingly in the Mizrahi opinion, may have exaggerated when he said that a constitution without constitutional adjudication is just like not having a constitution at all. There is a number of long-established democracies where the constitution mattersalthough no constitutional review exists. Here constitutional values have become part of the legal and political culture so that there is less need for institutionalized safeguards. But for the majority of states, in particular for those who turned toward constitutional democracy only recently, it is true that the constitution would not matter very much in day-to-day politics if it did not enjoy the support of a special agent that enforces the legal constraints to which the constitution submits politics. The small impact of fundamental rights before the establishment of judicial review proves this.However, the existence of a constitutional court alone is not sufficient to guarantee that politicians respect the constitution. Just as constitutionalism is an endangered achievement constitutional adjudication is in danger as well. Politicians, even if they originally agreed to establish judicial review, soon find out that its exercise by constitutional courts is often burdensome for them. Constitutions put politics under constraints and constitutional courts exist in order to enforce these constraints. Not everything that politicians find necessary – be it for themselves or their party, be it for what they deem good for the common interest – can be effectuated if the court sees it not in line with the constitution. Politicians therefore have a general interest in a constitutional court that, to put it mildly, is at least not adverse to their objectives and plans. But there is also a specific interest in the outcome of constitutional litigation on which the implementation of a certain policy depends.Yet, any political interference with the judicial process would undermine the whole system of constitutional democracy. This is why judges must be protected against political influence or pressure. The dividing line between the various organs of the state drawn by the principle of separation of powers is particularly strong where the judiciary is concerned. Independence of the judiciary is indispensable for the functioning of a constitutional system and is therefore itself in need of constitutional protection. If it is true that constitutional courts are helpless when political actors refuse to obey their orders, it is even more true that constitutional courts are useless when they cannot take their decisions independently from politics. The best protection of judicial independence is, of course, a deeply-rooted conviction on the side of politicians that any interference with court procedures is unacceptable, supported by a strong backing for the constitution within society. But this cannot be taken for granted. Rather, special safeguards are necessary. Judicial independence must be guaranteed, not only against any attempt to directly influence the outcome of litigation, but also against more subtle ways of putting pressure on the judiciary. This is why constitutions usually guarantee the irremovability of judges and often a sufficient salary, to mention only a few devices.A special problem in this context is the recruitment of judges of constitutional courts or courts with constitutional jurisdiction. Since these courts have a share in public power the judges need democratic legitimation. If they are not elected directly by the people, a circumstance which presents problems of its own regarding judicial independence, some involvement of the elected branches of government in the recruitment process seems inevitable. Yet, every involvement creates the temptation to elect or appoint deferential judges. Recruitment of judges is the open flank of judicial independence. A constitutional court that simply reflects political interests will hardly be able to keep the necessary distance from politics. Hence, safeguards against a politicization of the court are of vital importance.Most countries with constitutional adjudication have some special provisions for the election or appointment of constitutional judges. If they are elected by parliament often a supermajority, like the one required for amending the constitution, is prescribed. This means that majority and minority must agree on one candidate, which makes extreme partisan appointments unlikely. Other countries prefer a mixed system of election and appointment by dividing the right to select constitutional judges among different bodies of government. In others, non-political actors are involved in the process, for instance representatives of the legal profession. It may be difficult to determine which system is the best. But it is not difficult to see that some barriers against the threat of a politically docile constitutional court must be erected if constitutionalism is to live up to its aspirations.3. Judicial independence is the constitutional safeguard against the threat arising from politicians to the judges' proper exercise of their function. It is directed against attempts to induce judges not to apply the law but to bend to political expectations. This is an external threat. But it would be naïve toassume that this is the only threat the functioning of the constitutional system is exposed to. There is an internal threat as well that comes from the judges themselves. It comes in two forms. One is the inclination to voluntarily follow, for what reasons ever, political expectations or even party lines. The other is the temptation to adjudicate according to one‘s own political preferences or ideas of what is just and unjust instead of following constitutional standards. The constitutional guarantee of judicial independence protects judges against politics, but it does not protect the constitutional system and society against judges who, for other reasons than direct political pressure, are willing to disobey or distort the law.Therefore, external independence must be accompanied by internal independence. The constitutional guarantee of judicial independence is not a personal privilege to decide at will, but a functional requirement. It shall enable judges to fulfil their function, namely to apply the law irrespectively of the interests and expectations of the parties to the litigation or powerful political or societal forces. It frees judges from extra-legal bonds, not to give them leeway in their decisions, but to enable them to decide according to the law. The reason for the independence from extra-legal bonds is to give full effect to the legal bonds to which judges are submitted. Submission to law is the necessary counterpart of judicial independence. Like for external independence, precautions can be taken for internal independence as well.However, since internal independence is largely a matter of professional ethics and individual character, the possibilities of the law are limited. Gross misbehaviour such as corruption can of course be outlawed and made a crime. Experience shows, however, that it is difficult to fight corruption within the judiciary when corruption is habitual among politicians and in society as well. This seems to be quite a problem in a number of new democracies. It is likewise justified to criminalize perversion of justice. But it is not easy to clearly distinguish perversion of justice from false or questionable interpretation of the law. This is why convictions because of perversion of justice are rare. Yet, criminalizing corruption and perversion of justice and removing judges from office who committed these crimes is not a violation of the independence of the judiciary.A more subtle misconduct is the willingness or pre-disposition to interpret the law in a way that is favourable to certain political views or to a party or a candidate for political office, either in general or in an individual case. This usually comes in the disguise of a legal argumentation that seeks to hide that, as a matter of fact, it is result-driven. This will not always occur intentionally. Self-deception of judges as to the motives of their judicial behaviour is not impossible. The problem is that this type of misconduct does not only appear in a number of new democracies. It can be observed in solid constitutional states as well. The decision of the US Supreme Court in Bush v. Gore in the year 2000 may serve as an example. There will hardly be a legal sanction in these cases. But there may be harsh public criticism or even a loss of trust in the judiciary to which no court can remain indifferent.II.1. Law owes its existence to a political decision. Political motives are legitimate in the process of law-making. But in a constitutional democracy the role of politics ends when it comes to applying the law. Application of the law is a matter for the legal system in which political motives are illegitimate. For this reason the division between law and politics is of crucial importance. But what if law application and in particular constitutional adjudication is in itself a political operation so that all attempts to separate law from politics on the institutional level are thwarted on the level of law application? This is a serious question, and it is a question that should not be confused with the abuse of judicial power which lies in the intentional non-application or misapplication of the law.Of course, constitutional adjudication is inevitably political in the sense that the object and the effect of constitutional court decisions are political. This follows from the very function of constitutional law, which is to regulate the formation and exercise of political power, and the function of constitutional courts, which consists in enforcing this law vis-à-vis politics. Constitutional courts are a branch of government. Excluding political issues from judicial scrutiny would be the end ofconstitutional review. Hence, the question can only be whether operations that judges undertake in order to find the law and to apply it to political issues are of a political or a legal character.This question arises because all analyses of the process of law application to concrete issues show that the text of the law is unable to completely determine judicial decisions. One of the reasons is that the law in general and constitutional law in particular is neither void of gaps and contradictions nor always clear and unambiguous, and it can hardly be different, given the fact that a legal system is a product of different times, reacting to various challenges, inspired by different interests or concepts of justice and depending on the use of ordinary language. Filling the gaps, harmonizing the contradicting provisions, rendering them precise enough for the decision of an issue is the task of the law applicants, in the last resort of the courts, which, in turn, draw profit from the efforts of legal science.But even if provisions are formulated as clearly and as coherently as possible they can raise questions when it comes to solving a concrete case. This incapacity to guarantee a full determination of legal decisions, even in the case of seemingly clear provisions, is inherent in the law because a law is by definition a general rule applicable to an indefinite number of cases arising in the future. This is why it must be formulated in more or less abstract terms. Consequently, there will always remain a gap between the general and abstract norm on the one hand and the concrete and individual case on the other. The judge has to find out what the general norm means with regard to the case at hand. This is achieved by interpretation, which always precedes the application of the norm. The general norm must be concretized to a more specific rule before the individual case can be decided.Like the task of filling gaps, harmonizing contradicting provisions, clarifying vague norms, the concretization contains a creative element. Norm application therefore is always to a certain extent norm-construction. The fact as such is undisputable. The degree can vary. It depends on a number of variables. The most important one is the precision of a norm. A narrowly tailored norm leaves less room for the constructive element whereas a broad or even vague norm requires a lot of concretization before it is ready for application to a case. Usually a constitution will contain more vague norms than, say, the code of civil procedure. This is certainly true for the guiding principles and for fundamental rights, less so for organizational and procedural norms. Another variable is the age of a norm. The older a norm the larger the number of problems that were not or could not have been foreseen by the legislature and thus raise questions of meaning and applicability.The mere fact that the law does not fully determine the judgment in individual cases is not sufficient to turn law application from a legal into a political operation. It remains a legal operation if what the judge adds to the text of the law in the process of interpretation has its basis in the text and can be derived from it in a reasonable argumentative manner. If not it becomes a political one. The task therefore is to distinguish between legal and non-legal arguments, be they political, economic or religious. This decision can only be taken within the legal system. No other system is competent to determine what counts as a legal argument. Within the legal system the distinction between a legal and a non-legal argument is the concern of methodology. By doing so methodology attempts to eliminate subjective influences from the interpretation of the law as far as possible. This is why the distinction between legal and non-legal operations in the course of law application becomes largely a question of legal method.Yet, different from the text of the law that is the product of a political decision and thus not at the disposition of judges, methodology is itself a product of legal considerations. It emerges in the process of interpreting and applying the law or is developed in scholarly discourse, but it is nowhere decreed authoritatively. This means at the same time that various methodologies can coexist and so can different variations of a certain methodological creed. Method is a matter of choice within the legal system. All historical attempts by legislators to prohibit interpretation or to prescribe a certain method have been in vain. They were themselves subject to interpretation. But the lack of one authoritative method does not mean that methodology can justify any solution and thus loses its disciplining effect on judges. Just as certain legal systems have their time in history methodologies have their time, too. There is usually a core of accepted arguments or operations and a number of arguments or operationsthat are regarded as unacceptable. The degree to which a method can succeed in eliminating all subjective elements from interpretation is controversial. There were and are methods that claim this capacity.2. A historically influential method that promised to eliminate subjective influences was legal positivism, not in its capacity as a theory of the validity of law opposed to all natural law theories, but in its capacity as theory of legal interpretation. For a positivist in this sense the legal norm consists of its text and nothing else, and the only instrument to discover the meaning of the text is philology and logic, i.e. not the legislative history, not the motives or the intent of the legislature, not the values behind the norm, not the social reality that brought forth the problems the norm was meant to solve and in which it is to take effect, not the consequences the interpretation may entail. There can be but one correct understanding of a norm and this remains correct as long as the norm is in force, no matter how the context changes.The problem with positivism was on the one hand that it could not fulfil its promise to eliminate all subjective influences on interpretation. Rather these influences were infused into the interpretation in a clandestine way, mostly in connection with the definition of the notions used by the legislature. On the other hand, positivism prohibited an adaptation of the law to social change by way of interpretation. Since the social reality in which the norm was to take effect was regarded as irrelevant for the interpretation a positivist could not even perceive of social change. Of course, a positivist would not have denied that, because of social change, a legal norm may miss its purpose and produce dysfunctional results. But this was regarded as a matter for the law-maker, not for the law-applicant. It was this deficit that largely contributed to the decline of positivism after the far-reaching social change in the wake of the Industrial Revolution and World War I.There is yet another influential theory of interpretation that claims to preclude all subjective influences, namely originalism. Different from positivism, originalists believe that only a historical method is the right way to ascertain the meaning of a legal norm. The law-applicant must give a norm, in particular a norm of the constitution, no meaning other than the one that the framers had had in mind. Sometimes originalism appears in a crude way that excludes the application of a norm to any phenomenon the framers could not have known. If the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution protects the freedom of the press, this would not allow the law-applicant to extend the protection to radio and TV by way of interpretation. Sometimes originalism appears in a more enlightened form. The law-applicant is then permitted to ask whether the framers clearly would have included a new phenomenon had they known it at the time when the law was enacted. In this case it would be methodologically permissible to include radio and TV into the protection of the First Amendment by way of interpretation. But like a positivist an originalist is not prepared to acknowledge that there can be more than one sound interpretation of a norm and that the interpretation can legitimately change when the circumstances change in which it is applied.The problem with originalism is first a practical one. In most cases it is difficult or even impossible to know what the original understanding or the original intent was. It is the more difficult if many persons are involved in the process of constitution-making many of whom may not have expressed their understanding or intent. For this reason ascertaining the original intent or understanding is often a highly selective process, in which some utterances of actors are singled out and taken for the whole. The second problem is the same that positivism encountered. There is extremely limited or even no room at all for the adaptation of legal norms to social change. If social change affects the constitution adversely the only remedy is to amend the text, which can be extremely complicated in a country like the United States. The constitution tends to petrify, in opposition to the theory of a living constitution.Although one would have difficulties in finding positivists or originalists in Germany, these methodologies are by no means of historical interest only. Positivism, or more precisely a crude literal understanding, plays a considerable role in a number of post-communist countries and in parts of Latin America. Originalism has a stronghold in the United States in reaction to the activist Warren Court of the 1950s and '60s. In Germany, the idea that a legal method exists that can exclude any subjective。

美国司法经典名言英语普辛森

美国司法经典名言英语普辛森Justice is the cornerstone of a society that values fairness and equality. It is the bedrock upon which the rule of law is built, ensuring that every citizen stands on equal footing before the law.The American judicial system, with its rich history, has produced many timeless quotes that encapsulate the essence of justice. One such quote, attributed to the renowned jurist Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., is "The life of the law has not been logic; it has been experience." This highlights the importance of practical wisdom in the application of legal principles.Another classic quote that resonates with the American spirit is "Justice delayed is justice denied." It underscores the urgency of timely judicial processes, emphasizing that the wheels of justice should not turn too slowly, lest they fail to serve their purpose.The pursuit of justice is not without its challenges, as eloquently expressed in the words, "The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice." This quote, often attributed to Martin Luther King Jr., reminds us that while progress may be slow, the ultimate goal of justice is worth striving for.In the quest for justice, it is also important toremember that "The price of freedom is eternal vigilance." This phrase, often attributed to Thomas Jefferson, serves as a reminder that the liberties we enjoy are not guaranteed but must be actively defended.The American legal system is also known for its emphasis on the presumption of innocence, as captured in the phrase, "Innocent until proven guilty." This principle is a fundamental safeguard against the abuse of power and ensures that every accused person receives a fair trial.The idea that justice is not just about legal procedures but also about moral principles is reflected in the saying, "The best way to not feel hopeless is to get up and do something. Don't wait for good things to happen to you. If you go out and make some good things happen, you will fill the world with hope." This quote, while not directly from a legal figure, is a call to action that aligns with the proactive spirit of American justice.Finally, the American judicial system is often praisedfor its commitment to justice for all, as expressed in the words, "We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal." This foundational principle of the American Declaration of Independence is a reminder that the pursuit of justice is an ongoing journey towards equality and fairness for all.。

正义与良知材料英语作文题目

正义与良知材料英语作文题目Justice and Conscience: An Indivisible Union.In the tapestry of human existence, justice and conscience weave an intricate and inseparable fabric. Justice, embodies the principles of fairness, impartiality, and the equitable distribution of rights andresponsibilities within society. Conscience, on the other hand, serves as an internal compass, guiding our actions and decisions based on moral principles and ethical values.The symbiotic relationship between justice and conscience is undeniable. Justice provides a framework for regulating social interactions, ensuring that individuals are treated with respect and accorded their due rights. It upholds the rule of law, preventing arbitrariness and discrimination, and fosters a sense of trust and security within communities. Conscience, in turn, serves as a check on our own actions, reminding us of our moral obligations and prompting us to act in accordance with principles offairness and compassion.In the absence of justice, the dictates of conscience can be easily dismissed or ignored. When laws are unjust or unequally enforced, the marginalized and voiceless are left vulnerable to oppression and exploitation. Without the internal guidance of conscience, individuals may be more inclined to rationalize their actions, even when they conflict with fundamental moral principles. The result is a society that is fragmented, distrustful, and morally bankrupt.Conversely, when conscience is left unchecked by the principles of justice, it can lead to a narrow, self-righteous perspective. Individuals may become convincedthat their own moral beliefs are absolute and superior to all others, resulting in intolerance, zealotry, and even violence. A just society, therefore, requires a balance between the objective principles of justice and the subjective dictates of conscience, ensuring that neither can overpower the other.Throughout history, there have been countless examples of individuals who have acted upon the dictates of both justice and conscience, often in the face of adversity. Martin Luther King Jr. fought tirelessly for civil rights, grounding his actions in the principles of justice and the moral imperative to fight against injustice. Mahatma Gandhi advocated for nonviolent civil disobedience, using his conscience to challenge unjust laws and inspire a movement for independence. Nelson Mandela endured decades of imprisonment for his beliefs, his unwavering commitment to justice and reconciliation serving as a beacon of hope for his people.These individuals knew that true justice cannot be achieved without the guiding voice of conscience. They understood that the law alone is not always sufficient to protect the rights of the oppressed or ensure moral behavior. By acting in accordance with both justice and conscience, they inspired countless others to stand up for what is right and to strive for a more just and equitable world.In conclusion, justice and conscience are indispensable partners in the pursuit of a harmonious and ethical society. Justice provides the external framework for fair and impartial treatment, while conscience serves as an internal guide, prompting us to act with integrity and compassion. When these two forces are aligned, society flourishes, and individuals lead lives of purpose and fulfillment. It is through the indivisible union of justice and consciencethat we can build a world where all people are treated with dignity, respect, and the opportunity to live free fromfear and oppression.。

法律精神英文作文

法律精神英文作文The spirit of law is to ensure justice and fairness for all members of society. It is about upholding the rights and responsibilities of individuals, as well as maintaining order and stability within the community. Without thespirit of law, there would be chaos and anarchy, with no way to resolve disputes or protect the vulnerable.Laws are designed to reflect the values and beliefs of a society, and they evolve over time to adapt to changing social norms and attitudes. The spirit of law is therefore dynamic and responsive, able to address new challenges and injustices as they arise. It is not a rigid set of rules, but a living framework that can be shaped and reinterpreted to meet the needs of the people.The spirit of law also serves as a guide for ethical behavior, encouraging individuals to act in ways that are just and morally upright. It sets a standard for how people should treat one another, and provides a basis for holdingindividuals and institutions accountable for their actions. In this way, the spirit of law helps to foster a culture of respect and integrity within society.At its core, the spirit of law is about promoting the common good and protecting the rights of all individuals, regardless of their background or status. It is areflection of our shared humanity and the belief that every person deserves to be treated with dignity and fairness. Without the spirit of law, there would be no foundation for building a just and inclusive society.In conclusion, the spirit of law is essential for creating a harmonious and equitable society. It provides a framework for resolving conflicts, upholding ethical standards, and promoting the well-being of all members of the community. By embracing the spirit of law, we can work towards a more just and compassionate world for future generations.。

公正点亮心灯的英语作文

Justice is the cornerstone of a civilized society,and it is the light that illuminates the hearts of people.In this essay,we will explore the significance of justice in our lives and how it serves as a guiding light for our moral compass.First and foremost,justice is essential for maintaining social order.Without a sense of fairness,society would descend into chaos,as individuals would feel that their rights and interests are not protected.This could lead to conflicts and disputes,which would disrupt the harmony of the community.By ensuring that everyone is treated equally and that their rights are respected,justice helps to create a stable and peaceful environment.Moreover,justice fosters trust and cooperation among individuals.When people believe that they are being treated fairly,they are more likely to work together and support one another.This sense of unity and collaboration is crucial for the progress and development of society.For example,in a workplace,employees who feel that they are being treated justly are more likely to be motivated and committed to their jobs,leading to increased productivity and innovation.In addition,justice is a fundamental aspect of personal growth and development.When individuals experience justice,they are more likely to develop a strong sense of selfworth and dignity.This,in turn,helps them to become more empathetic and compassionate towards others.By promoting fairness and equality,justice encourages individuals to treat others with respect and kindness,which is essential for building strong relationships and communities.Furthermore,justice serves as a moral compass,guiding individuals towards making ethical decisions.When people are aware of the importance of justice,they are more likely to consider the consequences of their actions and strive to do what is right.This sense of moral responsibility is crucial for preventing unethical behavior and promoting a culture of integrity and honesty.Lastly,justice is a source of inspiration and motivation.When individuals witness acts of justice,it can inspire them to stand up for what they believe in and fight for their rights. This courage and determination can lead to positive change and progress in society,as people work together to create a more just and equitable world.In conclusion,justice is a vital force that lights up the hearts of people,guiding them towards a more harmonious and ethical society.By promoting fairness,trust,personal growth,and moral responsibility,justice serves as a beacon of hope and inspiration for all. Let us strive to uphold justice in our lives and work together to create a world where everyone is treated with dignity and respect.。

司法理念英语作文

司法理念英语作文英文回答:The concept of justice encompasses a vast array of philosophical and legal principles that underpin the administration of law and the pursuit of fairness within society. However, the fundamental principles of justice can be distilled into two overarching categories:1. Procedural Justice: This principle focuses on the fairness and impartiality of the legal process itself. It requires that individuals are treated equally and fairly by the law, regardless of their background or circumstances. Procedural justice ensures that laws are applied consistently, hearings are conducted impartially, and punishments are imposed justly.2. Substantive Justice: This principle addresses the fairness of the outcomes or laws themselves. It aims to ensure that laws and policies promote equity and protectthe vulnerable members of society. Substantive justice focuses on the distribution of resources, access to opportunities, and the fundamental rights and freedoms guaranteed to all individuals.中文回答:司法理念。

Restorative_Justice_in_China

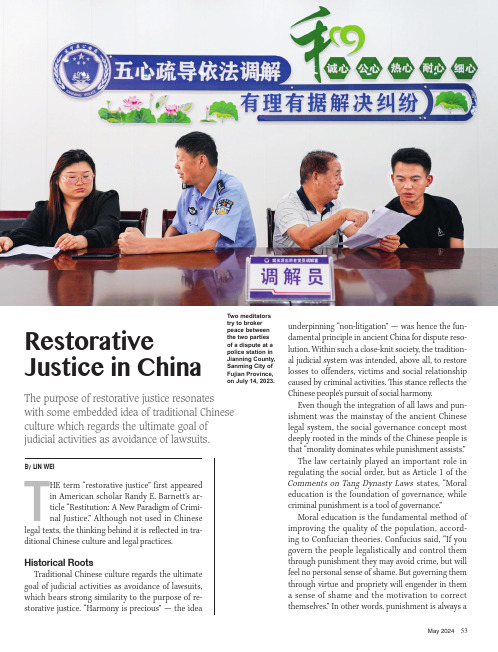

53May 2024THE term “restorative justice” first appeared in American scholar Randy E. Barnett’s ar-ticle “Restitution: A New Paradigm of Crimi-nal Justice.” Although not used in Chinese legal texts, the thinking behind it is reflected in tra-ditional Chinese culture and legal practices.Historical RootsTraditional Chinese culture regards the ultimate goal of judicial activities as avoidance of lawsuits, which bears strong similarity to the purpose of re-storative justice. “Harmony is precious” — the ideaBy LIN WEIRestorative Justice in ChinaThe purpose of restorative justice resonates with some embedded idea of traditional Chinese culture which regards the ultimate goal of judicial activities as avoidance of lawsuits.underpinning “non-litigation” — was hence the fun-damental principle in ancient China for dispute reso-lution. Within such a close-knit society, the tradition-al judicial system was intended, above all, to restore losses to offenders, victims and social relationship caused by criminal activities. This stance reflects the Chinese people’s pursuit of social harmony.Even though the integration of all laws and pun-ishment was the mainstay of the ancient Chinese legal system, the social governance concept most deeply rooted in the minds of the Chinese people is that “morality dominates while punishment assists.”The law certainly played an important role in regulating the social order, but as Article 1 of the Comments on Tang Dynasty Laws states, “Moral education is the foundation of governance, while criminal punishment is a tool of governance.”Moral education is the fundamental method of improving the quality of the population, accord-ing to Confucian theories. Confucius said, “If you govern the people legalistically and control them through punishment they may avoid crime, but will feel no personal sense of shame. But governing them through virtue and propriety will engender in them a sense of shame and the motivation to correct themselves.”In other words, punishment is always aTwo meditators try to broker peace between the two parties of a dispute at a police station in Jianning County, Sanming City of Fujian Province, on July 14, 2023.measure of last resort, and must not be relied upon to prevent crime.In their handling of disputes, ancient China’s officials carried the dual responsibilities of adju-dicating cases in ways calculated to educate and reform the public, in regard to both rationality and moral sensibility. Consequently, social governance was exercised not just through adjudication. It also emphasized the need to adopt informal procedures to resolve conflicts, and to educate and influence through a large number of non-judicial procedures prior to judicial ones, in efforts to avoid further de-terioration of civil behavior. Restorative justice also places special emphasis on early intervention in this regard, to root out any latent eruption of crime. The two concepts are hence highly compatible. Having emphasized throughout its long history the need for maintaining and restoring social rela-tions, mediation played an irreplaceable role in China’s traditional model of governance. Unlike the general criminal justice model, the mediation pro-cess attaches great importance to the subjectivity and initiative of the victim, and to providing them with comfort and compensation.In so doing it promotes justice and protects the victim’s interests by reducing the risk of their becoming perpetrators, heals rifts in interpersonal relations, and eventually restores social order. At the same time, the subjects and applications of media-tion have rendered it a diverse and flexible medium. Ancient mediators ranged from local gentry to intel-lectuals and community elders. Discussions held in various localities enabled them to bridge the social relations that illegal behaviors had damaged, and at the same time considerably reduce both judicial and social costs.Introduction to ChinaDespite the appearance in traditional Chinese governance and judicial models of the ideas and practices of restorative justice, it did not enter China’s mainland as a Western judicial concept until the early 21st century. Efforts have since been made to integrate restorative justice with Chinese judicial practices in a trial basis.For example, in 2002, the Beijing Municipal People's Procuratorate introduced reconciliationinto criminal proceedings. In 2006, the ShanghaiMinhang District Procuratorate applied the conceptand methods of restorative justice in its handlingof a juvenile delinquency case. With prosecutor’smediation, the suspect and the victim negotiatedand communicated with each other and reached asettlement without resorting to court ruling. As aresult, China’s public prosecutors and judicial au-thorities encourage reconciliation between offend-ers and victims in both private and public cases. In2012, the criminal reconciliation system was legal-ized in the Criminal Procedure Law.Restorative justice becomes a judicial practice inmodern China against a social background similarwith that in the West. Since the country’s reformand opening-up in 1978, China's economy hasmade remarkable progress. However, this dramaticchange has disrupted the social structure, leading toseismic changes in social relations and intensifiedsocial conflicts. New types of illegal and criminalacts have proliferated, and the structure of crimeitself is undergoing significant changes. The steepincrease in numbers of incarcerated persons posesa heavy financial burden on the state and puts enor-mous pressure on social correction resources. It isalso often difficult for ex-offenders to reintegratethemselves into society. Cases where victims havenot been adequately compensated make repairingruptured relations between the concerned partiesproblematic, so potentially escalating conflict andgiving rise to new crimes.It is under this circumstance that the conceptof restorative justice has entered Chinese scholars’field of vision and been introduced into China. Inother words, its integration with traditional Chinesejudicial theories has revitalized judicial practices inChina.The introduction and implementation of theconcept of restorative justice is conducive to re-pairing social relationships that criminal behaviorhas damaged, to reducing excessive reliance oncriminal punishment and imprisonment, therebyultimately re-establishing a more stable social order,and achieving social harmony. It is congruous withChina’s traditional culture which is centered onConfucianism and judicial traditions that prioritizemediation.similarRestorativejustice be-comes ajudicial prac-tice in modernChina againsta social back-ground similarwith that in theWest.54CHINA TODAY55May 2024Recent DevelopmentsIt is generally recognized that China’s legal norms on restorative justice are mainly reflected in the two systems of criminal reconciliation and victims’ forgiveness.The Criminal Procedure Law, amended in 2012, includes provisions on criminal reconciliation in Articles 277, 278, and 279. The 2018 revision of the law includes procedures for reconciliation between concerned parties in cases of public prosecution. The provisions stipulate the basic conditions, scope of participants, procedures, and substantive conse-quences of criminal reconciliation.According to them, a reconciliation agreement can be applied to public prosecution when the criminal suspect or defendant sincerely regrets their crime and has obtained the victim’s forgiveness through compensation and apologies, and when the victim agrees to accept the settlement.Typical cases include those in which offenders infringe on others’ personal or property rights and could face a fixed-term imprisonment of up to three years, or offenders committed a crime out of neg-ligence other than the crime of dereliction of duty and could face up to seven years in prison. If the criminal suspect or defendant has committed inten-tional crimes over the past five years, the reconcilia-tion procedures shall not apply.Criminal reconciliation is also applicable to crimes committed by minors. For example, in cases where a minor inflicts minor injuries, commits a first-time crime or a crime of negligence, attempts a crime, or is deceived or instigated into committing a crime, they may be exempted from prosecution if they show genuine remorse; and both parties voluntarily reach an agreement on civil reparation, or an effective guar-antee is provided upon the victim’s agreement. Under such circumstances, the people's procuratorate may decide not to prosecute but instead admonish or or-der a statement of repentance, apology, and compen-sation for losses. Competent department could also mete out administrative penalties.The Supreme People's Court made further clari-fications on the sentencing standards for perpe-trators in several documents. It is stated that the nature of the crime, the amount of compensation, apologies, and sincere repentance should be takeninto consideration. If the crime is relatively minor, “the base penalty may be reduced by more than 50 percent, or the penalty may be exempted in accor-dance with the law.”At the same time, the system of victim forgive-ness, which is complementary to the criminal rec-onciliation, is taking shape in China. The victim’s forgiveness is an important factor that judges take into account when deliberating on sentences. If a suspect compensates the victim for financial losses and obtains forgiveness, their sentence may be reduced by less than 40 percent. And even if the suspect obtains an understanding without offering compensation, their sentence may still be reduced by less than 20 percent.Certain problems are still to be resolved in China’s application of restorative justice. They include how to ensure the reconciliation is voluntary, and how to give play to the role of mediators. Whether the scope of its application can be further expanded — for example, in cases of felonies or even capital punish-ment — and how to carry out scientific evaluation of its application all require further study. We need to keep an open mind, learn from the experience of other countries, and integrate it with our own. In tapping into the advantages of this system, we will advance the modernization of China’s governance capacity and build a more harmonious society. CLIN WEI is a professor of the Law School, Southwest Univer-sity of Political Science and Law.A mediation ses-sion involving a judge of the People’s Court of Shizhong Dis-trict, a mediator, and both parties of a dispute in Zaozhuang City, Shandong Prov-ince, is held on No-vember 17, 2023.。

担当守护正义与和平的英语作文

Justice and peace are two fundamental values that form the bedrock of any civilized society.They are the twin pillars upon which the edifice of human rights and social order is constructed.To uphold these values,individuals and institutions must take on the role of guardians,ensuring that justice is served and peace is maintained.Firstly,justice is the principle of fairness and equality in the treatment of all individuals. It demands that every person receives what they are rightfully entitled to,without bias or favoritism.To be a guardian of justice,one must be vigilant against any form of discrimination,whether it be based on race,gender,religion,or social status.This requires a commitment to the rule of law,which provides a framework for resolving disputes and punishing wrongdoing.Moreover,justice also encompasses the idea of restorative justice,where the focus is on healing and reconciliation rather than merely punishment.This approach recognizes that victims of injustice need to be made whole,and that offenders should be given the opportunity to make amends for their actions.Secondly,peace is the absence of conflict and the presence of harmony.It is a state of tranquility where people can live without fear of violence or aggression.Guardians of peace work to prevent disputes from escalating into violence and to promote dialogue and understanding between different parties.This involves fostering a culture of tolerance and respect for diversity,where everyones opinions and beliefs are valued.In addition to preventing conflict,peacekeepers also play a crucial role in postconflict situations.They help to rebuild societies by addressing the root causes of the conflict, such as poverty,inequality,and lack of access to education and healthcare.They also support the establishment of democratic institutions and the rule of law,which are essential for longterm peace and stability.Being a guardian of justice and peace is not an easy task.It requires courage,integrity, and a deep sense of responsibility.It also demands a commitment to continuous learning and adaptation,as new challenges and threats to these values constantly emerge. However,the rewards of this endeavor are immense,as it contributes to the creation of a more just and peaceful world for all.In conclusion,the guardianship of justice and peace is a noble and essential duty that everyone should strive to fulfill.By standing up for what is right and working to resolve conflicts in a peaceful manner,we can build a society that is characterized by fairness, equality,and harmony.This is the legacy that we owe to future generations,and the responsibility that we bear as members of the global community.。

公正奠定基石的英语作文

Justice is the cornerstone of a fair and harmonious society.It serves as the foundation upon which trust,respect,and equality are built.In this essay,we will explore the importance of justice and how it shapes the world we live in.Firstly,justice is essential for maintaining social order.When people believe that the legal system is fair and just,they are more likely to abide by the law and respect the rights of others.This reduces the likelihood of crime and conflict,creating a safer and more stable environment for everyone.Secondly,justice promotes equality.By ensuring that everyone is treated fairly and has equal opportunities,justice helps to eliminate discrimination and prejudice.This allows individuals to reach their full potential,regardless of their background or circumstances.Thirdly,justice fosters trust in institutions.When people see that justice is being served, they are more likely to have faith in the government,the legal system,and other societal structures.This trust is crucial for the smooth functioning of society and the effective implementation of policies and laws.Moreover,justice encourages moral development.When individuals witness just actions and decisions,they are more likely to emulate these behaviors in their own lives.This helps to create a more ethical and compassionate society,where people are more inclined to help others and act with integrity.However,achieving justice is not always straightforward.It requires a fair and unbiased legal system,as well as a society that values fairness and equality.Additionally,it is important to address the root causes of injustice,such as poverty,inequality,and discrimination,in order to create lasting change.In conclusion,justice is a fundamental principle that underpins a just and equitable society.By promoting social order,equality,trust,and moral development,justice plays a vital role in shaping the world we live in.It is our collective responsibility to strive for justice and work towards a fairer and more harmonious future for all.。

正义的英语作文

Justice is a fundamental concept in society,deeply rooted in various cultures and legal systems around the world.It is the idea that fairness and impartiality should be upheld in all dealings,ensuring that everyone is treated equally under the law.The Importance of JusticeJustice is crucial for maintaining social order and harmony.Without it,there would be chaos and a lack of trust in institutions that are meant to protect the rights and freedoms of individuals.It is the cornerstone of a democratic society,where the rule of law prevails over the whims of the powerful.Different Forms of JusticeThere are various forms of justice,including distributive justice,which concerns the fair distribution of resources and opportunities procedural justice,which focuses on the fairness of processes and procedures and restorative justice,which seeks to repair the harm caused by crime rather than simply punishing the offender.The Role of Law in JusticeLaws are the tools through which justice is implemented.They are designed to be universal,applying to all citizens equally.However,the effectiveness of laws in delivering justice depends on their clarity,fairness,and the impartiality of their enforcement.Challenges to JusticeDespite the best intentions,justice can be challenged by various factors such as corruption,bias,and the unequal distribution of power and resources.These challenges can lead to injustices,where certain individuals or groups are unfairly disadvantaged.The Pursuit of JusticeThe pursuit of justice is an ongoing process.It requires vigilance from citizens,a commitment to transparency and accountability from those in power,and a legal system that is capable of adapting to the changing needs of society.Examples of Justice in ActionExamples of justice in action can be seen in the efforts to combat discrimination,theimplementation of social welfare programs,and the establishment of international courts to prosecute war crimes and crimes against humanity.ConclusionIn conclusion,justice is an essential element of a wellfunctioning society.It is not just about punishing the guilty but also about protecting the innocent and ensuring that everyone has an equal opportunity to thrive.The quest for justice is a collective responsibility that requires the active participation of all members of society.。

社会契约论 英文版

社会契约论英文版

摘要:

一、引言

二、《社会契约论》的概述

三、英文版的名称

四、卢梭的著作难以理解的原因

五、结论

正文:

一、引言

《社会契约论》是法国思想家让- 雅克·卢梭于1762 年撰写的一部重要著作。

该书主张人类在国家成立之前处于自然状态,而国家是人类为了满足共同需求和保护自身利益而通过签订契约形成的。

在今天的知识界,该书被认为是现代政治哲学和社会科学领域的经典之作。

二、《社会契约论》的概述

《社会契约论》主要探讨了人类在自然状态下如何通过签订契约来建立国家,以及在这种状态下,个体与整体之间的权利和义务关系。

卢梭认为,人类在自然状态下是自由和平等的,但在现实生活中,人们往往为了保护自己的利益而侵犯他人的权益。

因此,人们需要通过签订契约来约束自己的行为,以实现社会秩序和公平正义。

三、英文版的名称

《社会契约论》的英文版名称为"The Social Contract"。

四、卢梭的著作难以理解的原因

尽管《社会契约论》在知识界具有很高的地位,但许多人认为该书难以理解。

这主要是因为卢梭的行文风格独特,思想深邃,容易让人产生误解。

此外,该书的许多观点在当时是非常激进的,可能会让人产生心理上的抗拒。

五、结论

总的来说,《社会契约论》是一部具有重要历史地位和现实意义的著作。

The Importance of Restorative Justice in Schools

The Importance of Restorative Justice in SchoolsIntroductionRestorative justice is an alternative approach to discipline that focuses on repairing harm caused by misconduct rather than simply punishing the wrongdoer. It involves bringing together those who have been harmed and those who have caused the harm, encouraging dialogue, understanding, and accountability. In recent years, restorative justice practices have gained recognition and popularity in educational settings due to their effectiveness in promoting empathy, reducing conflict, and fostering a positive school climate. This article will explore the importance of restorative justice in schools and its benefits for students, teachers, and the overall school community.Promoting Empathy and UnderstandingUnlike traditional punitive disciplinary methods that often lead to resentment and animosity between students, restorative justice practices aim to foster empathy and understanding. By bringing together conflicting parties in a supportive environment, restorative justice allows them to share their experiences, perspectives, and feelings. This process promotes active listening skills and encouragesparticipants to develop a deeper appreciation for each other's emotions and needs. Through this empathetic understanding, conflicts can be resolved more effectively and relationships can be restored. Developing Problem-Solving SkillsOne of the key advantages of incorporating restorative justice into schools is its emphasis on developing problem-solving skills among students. Traditional discipline methods tend to provide quick solutions without considering long-term consequences or teaching students how to handle similar situations differently in the future. However, with restorative justice practices, an emphasis is placed on engaging students in open dialogues where they are encouraged to take responsibility for their actions and work collaboratively towards finding mutually beneficial solutions. These problem-solving skills not only benefit individuals involved but also contribute to a more peaceful school environment.Cultivating a Positive School ClimateRestorative justice approaches have demonstrated their ability to significantly impact overall school climate by creating a sense of community based on respect, cooperation, and accountability. By implementing these practices consistently throughout the school community, students feel safer and more connected to their peers andteachers. This positive climate improves student engagement, reduces absenteeism, and enhances overall academic success. It also fosters a stronger sense of belonging and encourages students to actively participate in creating a supportive learning environment. Addressing the Root Causes of BehaviorsAnother critical aspect of restorative justice is its focus on addressing the underlying causes of behaviors rather than solely dealing with the immediate consequences. Traditional disciplinary methods tend to overlook the reasons behind certain actions and rely solely on punishment. In contrast, restorative justice practices allow for deeper exploration of factors such as trauma, mental health issues, or personal circumstances that might contribute to unruly behavior. By addressing these root causes and providing appropriate support systems, schools can assist students in overcoming challenges and facilitating meaningful behavior change.Creating Long-Term AccountabilityRestorative justice practices not only aim to repair relationships between individuals but also create long-term accountability within the school community. Through open dialogues, participants establish agreements on how individual actions impact others and collectively decide on measures to prevent similar conflicts from arising in thefuture. These agreements may include ongoing mentoring, counseling services, or participation in school-based programs that promote positive social interactions. By encouraging personal growth and reflection, restorative justice practices help students develop a stronger sense of responsibility for their actions while fostering a culture of empathy, forgiveness, and understanding.ConclusionIn conclusion, restorative justice has proven to be a crucial tool in promoting healthier disciplinary approaches within schools. By prioritizing empathy, understanding, problem-solving skills development, cultivating positive school climates by addressing underlying causes of behaviors effectively fostering long-term accountability within the school community. The implementation of restorative justice can lead to a significant reduction in conflicts among students while positively impacting academic achievements and overall well-being. With its numerous benefits for students' social-emotional development and school climate improvement rests decided that schools should consider integrating restorative justice practices into their disciplinary systems.。

英语作文惩罚犯罪