正常人不确定奖赏抉择加工激活脑区的分析

人类决策制定的心理和神经机制

人类决策制定的心理和神经机制人类决策制定的心理和神经机制是指人类在面对各种决策情境时,通过一系列心理和神经过程来解决问题和做出选择的方式和机制。

这些机制包括认知加工、情绪影响以及奖赏与惩罚等因素。

本文将从认知心理学和神经科学两个角度探讨人类决策制定的心理和神经机制。

认知心理学角度:1.信息收集与加工:人类在做决策之前,首先要收集与加工相关信息。

这涉及对外部环境的观察、感知和理解,以及对内部知识和经验的回忆和引用。

人们可以通过注意力、记忆和思维等认知过程对信息进行筛选和处理,以帮助他们做出最佳决策。

2.反思与思维模式:决策制定往往需要人们对问题进行深入分析和细致思考。

人们使用各种思维模式,如归纳推理、演绎推理、比较和对比等,以评估不同选项之间的优劣。

反思和思维模式对于人们决策的效果和结果起着关键作用。

3.决策风险与不确定性:决策制定往往伴随着风险与不确定性,人们必须在有限的信息和资源下做出选择。

研究表明,人们在决策风险和不确定性情境下往往受到认知偏差的影响,如避免损失、过度乐观、暴露效应等,这会影响他们的决策行为。

神经科学角度:1.大脑结构与决策制定:大脑的不同区域在决策制定过程中发挥不同的作用。

前额叶皮层是决策制定的核心区域,包括背外侧前额叶皮层(DLPFC)和前扣带皮层(ACC)。

DLPFC负责信息加工和规划行为,而ACC参与情感和奖赏与惩罚的处理。

2.奖赏与惩罚机制:大脑中的奖赏与惩罚机制对决策制定起着重要作用。

奖赏机制涉及到脑内多巴胺系统的活动,通过给予奖励来增强决策行为。

惩罚机制涉及到边缘系统的活动,通过给予惩罚来抑制决策行为。

奖赏与惩罚的平衡对于人类决策制定的结果至关重要。

3.情绪与决策制定:情绪对决策制定有着重要影响。

正面情绪可以提高决策效果,而负面情绪则可能导致决策偏差。

大脑中的扣带皮层在情绪与决策制定之间起着连接和调节作用。

人们的情绪状态会影响他们的决策行为,从而影响决策制定的结果。

大脑决策过程的神经科学研究

大脑决策过程的神经科学研究随着神经科学的发展,人们对于大脑决策过程的理解也不断加深。

大脑决策的过程十分复杂,它涉及到了大脑各个区域的协同作用。

本文将从神经元的活动开始,探讨大脑决策过程的神经科学研究。

神经元的活动神经元是构成大脑的基本单位,它们通过神经元之间的突触连接起来,形成神经网络。

神经元的电活动是大脑决策的基础。

在神经元内部,离子通道会受到不同的刺激,打开或关闭,使得离子进出神经元内部,改变膜电位。

当神经元内部膜电位变化到一定程度时,会产生动作电位,动作电位的传导使得神经元能够通过突触,与其他神经元建立联系。

神经元之间的连接形成的神经网络,是大脑决策的能够实现的基础。

神经元的兴奋和抑制相互作用,是大脑决策过程产生的基本机制。

认知神经科学为了深入理解人类决策过程及其神经基础,许多研究者开始将认知神经科学技术应用于大脑决策过程的研究。

认知神经科学的核心是实验心理学。

认知神经科学通过采用一些脑影像技术,如磁共振、脑电图,以及脑干反应等,将实验心理学和神经科学相结合,研究大脑决策的神经基础。

在一些实验中,研究者会让被试者参与决策任务,同时在大脑决策过程发生时,通过脑影像技术观察不同区域的活动情况。

通过这些实验,研究者发现,在大脑决策过程中,大脑的前额叶区域起着重要的作用。

前额叶区域前额叶区域是大脑的一部分,包含皮层前额叶、岛叶、扣带回、前扣带回、眶额皮层等区域。

前额叶区域是人类高级认知功能的重要区域,极其重要的功能之一是控制行为和认知的抉择和决策。

在大脑决策的过程中,前额叶区域处于核心地位,它主要参与计算概率、分类和评估行为/结果的利弊。

研究者通过脑影像技术发现,在做出决策时,前额叶区域脑电活动会出现特殊的信号,这些信号反映出了大脑在决策过程中的变化。

除此之外,前额叶区域还能够调节其他区域的活动。

一些研究表明,前额叶区域能够通过调节杏仁核的活动,来影响情绪体验和认知评估。

结论大脑决策过程的神经科学研究是一个相对比较复杂的领域,需要涉及到神经元的活动、认知神经科学以及前额叶区域等。

大脑奖赏机制

大脑奖赏机制什么是大脑奖赏机制大脑奖赏机制是指大脑在感受到愉悦或满足时所产生的一系列化学反应和神经活动。

这一机制对于个体的学习、动机和行为调节起着至关重要的作用。

奖赏机制的核心是多巴胺系统,它与奖赏相关的神经递质多巴胺在大脑中的释放和传递起着重要的调节作用。

多巴胺的作用多巴胺是一种神经递质,它在大脑中起着重要的调节作用。

多巴胺系统包括多巴胺神经元和多巴胺受体两部分。

多巴胺神经元主要分布在大脑中的奖赏回路中,如边缘系统、纹状体和前额叶皮质等区域。

多巴胺受体则分为D1和D2两类。

多巴胺的释放和传递对于奖赏的感受和记忆非常重要。

当我们体验到愉悦或满足时,多巴胺神经元会被激活,释放多巴胺到神经元之间的间隙,然后多巴胺通过结合多巴胺受体来传递信号。

这一过程会引起愉悦感和满足感,并加强相关的学习和记忆。

大脑奖赏机制的影响因素大脑奖赏机制的活动受到多种因素的影响。

以下是一些主要的影响因素:1. 遗传因素遗传因素对大脑奖赏机制的活动有一定的影响。

研究发现,不同个体之间在奖赏感受和反应上存在差异,这与其基因的多样性有关。

例如,一些人可能对奖赏刺激的反应更为强烈,而另一些人则相对较弱。

2. 社会环境社会环境对大脑奖赏机制的活动有重要影响。

人们在社会交往中获得的赞扬、认可和奖励会激活多巴胺系统,增强奖赏感受和记忆。

相反,社会排斥和惩罚会抑制多巴胺系统的活动,减弱奖赏感受。

3. 学习和记忆学习和记忆对大脑奖赏机制的活动起着重要的调节作用。

当我们获得奖励时,多巴胺的释放和传递会强化相关的学习和记忆,使我们更加倾向于重复和追求这种奖励。

这种学习和记忆的加强机制有助于个体适应环境并提高生存竞争力。

大脑奖赏机制与行为大脑奖赏机制对个体的行为调节起着重要作用。

以下是一些与大脑奖赏机制相关的行为:1. 导致成瘾的行为大脑奖赏机制与成瘾行为密切相关。

当个体反复接受某种奖赏刺激时,多巴胺系统会逐渐适应这种刺激,导致对奖赏的需求增加。

这种过度的奖赏依赖会导致成瘾的形成,使个体难以自控。

正常人情景记忆编码和提取加工的fMRI研究[1]

![正常人情景记忆编码和提取加工的fMRI研究[1]](https://img.taocdn.com/s3/m/8ac3dd53ad02de80d4d84089.png)

圈I。

2图l编码任务横断位脑激活吲图2提取任务横断f赶脑激f_,r,It-I(说明:图中的左即为实际的左侧大脑半球,图中的右即为实际的右侧大脑半球;彩色区域表示活动脑Ⅸ,色彩越红表示激活程埏越大)圈3,4图3编码任务三继脑激活图图4提取任务三维脑激活图(说明:图中自上而下。

第一排两幽为后面观和前而观。

第-.-tlls两图为右侧面观和左侧面观,第三排两19为下面观和上面观)

编码时左侧前额叶占优势,提取时右侧前额叶占优势有一致的地方,不一致的是提取时左侧额中回(BAl0)和左侧额下回(BA47)可见激活。

由于本实验采取了组块设计和事件相关结合的实验设计,采用的指导语基本一致,因此可能存在对任务的预测。

而且,本实验使用视觉记忆材料即汉字进行研究,由于汉字多为象形文字,具有独特的字形(由一定的笔画和偏旁部首组成),其空问结构规则远较英语等西方文字(多为线性结构)复杂。

因此,本实验提取加工过程中左侧额中回(BAl0)和左侧额下回(BA47)激活也能得到一定的解释。

海马一直是人们从事记忆研究的焦点问题。

本实验在情景记忆编码加工时右侧海马旁回可见激活。

内侧预叶系统中的海马旁回魁从新皮层向海马传人的重要通路,它可早期存储经海马编码的信息,并将它当作一种“标准”与后来收到的信息进行比较【8J,因此在记忆编码中起重要作用。

一般来说,海马的活动反映了对既往事件内容的回忆过程,而海马旁回的活动反映对熟悉和不熟悉刺激的分辨过程[9,10J。

本实验在编码和提取加工时海马结构均未见激活。

早期强调情景记忆时海马结构并不总是被激活的原因为技术限制(空问分辨率不够)或海马活

923。

人类决策行为的神经机制

人类决策行为的神经机制随着多年来科技的发展,我们越来越能够理解人类思维和决策背后的神经机制。

这些神经机制控制着我们进行决策和行动,对我们的生活产生着深远的影响。

在本文中,我们将探讨人类决策行动的神经机制,以了解我们如何做出决策和执行那些决策的过程。

我们知道,人类决策行为的神经机制主要在前额叶皮质和杏仁核中。

前额叶皮质是大脑皮质的一部分,负责执行许多高级认知功能,如决策制定、计划、语言和运动控制。

杏仁核位于大脑边缘,是情绪加工和记忆储存的关键结构,也与更高阶的感知加工和注意力控制有关。

在我们做出决策的时候,前额叶皮质和杏仁核开始发挥作用。

前额叶皮质接收来自环境的信息,同时将这些信息和记忆联系起来。

杏仁核则在信息处理的同时产生情感反应。

当前额叶皮质和杏仁核之间的交互作用协调地进行时,我们就能做出明智的决策。

这就是为什么当我们感到焦虑、愤怒或其他强烈的情绪时,很难做出理智的决策。

在这种情况下,我们的杏仁核可能会过于活跃,而干扰前额叶皮质对决策的控制。

价值编码也是人类决策过程中的关键因素之一。

价值编码是指大脑将不同的决策选项赋予价值的过程。

许多神经科学家认为,价值编码涉及到多个大脑区域的协调作用。

其中包括杏仁核、纹状体、海马体等。

这些区域在信息加工和价值编码方面扮演重要的角色。

在价值编码的过程中,我们所作的决策取决于大脑制定的“收益最大化”策略。

也就是说,大脑会对不同选项的价值进行比较,并选择那个能给予我们最大收益的选项。

研究发现,某些神经递质也对决策行为产生影响。

最常见的就是多巴胺。

多巴胺是大脑中的一种重要神经递质,被认为对奖赏和动机行为起着关键作用。

此外,一些神经调节剂也被证实对我们的决策行为产生影响。

例如,抑制剂会降低决策的速度和准确性,而刺激剂则会加速决策的速度,提高准确性和决策的信心。

最后,我们需要注意的是,人类决策行为的神经机制是复杂而动态的。

它受到许多因素的影响,包括情感状态、价值编码、神经递质等等。

人类大脑决策过程的神经机制解析

人类大脑决策过程的神经机制解析在我们日常生活中,每个人都需要做出许多决策。

无论是简单的选择午餐还是复杂的职业决策,决策过程都是人类思维活动的重要组成部分。

然而,人类大脑决策的神经机制仍然是一个引人注目且复杂的研究领域。

本文将从神经科学的角度,对人类大脑决策过程的神经机制进行解析。

人类大脑决策过程涉及到各种神经系统的协同工作,其中包括感觉、认知、决策、行动等几个关键环节。

首先,感觉系统接收和处理来自外界的信息,将它们转化为电信号并发送到大脑。

不同感觉通道的信息被传递到相应的脑区,如视觉信息被传递到视觉皮层,听觉信息被传递到听觉皮层等。

这些感觉信息不仅仅包含原始的感觉输入,还包括我们对外界的认知和理解。

当感觉信息到达大脑之后,认知系统开始对其进行处理。

认知系统涉及到注意、记忆、思考、推理等高级认知过程。

在决策过程中,注意力起着重要的作用,它可以帮助我们将有限的认知资源集中在最关键的信息上。

记忆也对决策产生重要影响,我们可以通过回顾过去的经验来指导当前的决策。

此外,思考和推理也可以帮助我们解决复杂的问题,提供不同方案的优劣评估。

在认知系统的基础上,决策系统起到了决策选择的关键作用。

决策系统涉及到大脑中的前额叶皮层、扣带皮质和杏仁核等脑区。

前额叶皮层是与决策密切相关的脑区之一,它被认为是整合信息、评估风险和奖励的重要组织。

扣带皮质在评估不同选择之间的价值方面发挥作用,而杏仁核主要参与情绪的处理和决策中风险判断的过程。

最后,行动系统负责将决策转化为具体的行动。

行动系统涉及到运动皮层和基底神经核等脑区。

运动皮层负责运动的规划和执行,而基底神经核则参与到运动的调节和控制。

通过行动系统的协同作用,我们能够将决策结果转化为具体的行动,实现我们的目标。

综上所述,人类大脑决策过程的神经机制涉及到多个神经系统的协同工作。

感觉系统收集外界信息,认知系统对信息进行处理,决策系统评估不同选择之间的价值,最后行动系统将决策结果转化为具体的行动。

人类行为与决策的认知神经科学研究

人类行为与决策的认知神经科学研究人类是具有高度智慧的生命体,而关于人类行为和决策的研究,则是认知神经科学中最为复杂和挑战性的一部分。

在过去的几十年间,神经科学家们不断探索和研究人类行为和决策的机制,致力于了解人类行为和决策背后的神经科学原理。

本文将介绍有关人类行为与决策的认知神经科学研究的一些进展。

一、行为与神经科学我们的行为是由我们的大脑控制的。

因此,人类行为的神经科学研究探索的是人脑的结构和功能,以及人脑与行为之间的关系。

这种研究将深入探索人类行为的各个方面,并有望使我们更清楚地理解我们自己的内在机制。

在神经科学的研究中,一个著名的方法是传统的神经影像学。

这种方法通常是使用功能性磁共振成像(fMRI)来探测在执行各种任务时,人脑的活动情况。

例如,异常反应,如海马体增生和受损,可以阻止人类记忆的形成。

还有,正常的情感反应可以通过辖限较低的大脑区域来完成,而对于高复杂度的转换则需要更加广泛和互连的大脑区域。

二、决策与神经科学决策研究领域涉及人类如何做出各种选择和决策。

这涵盖了许多领域,并包括经济学、社会学、心理学和神经科学等。

在神经科学的层面上,人们在研究决策的神经过程依靠传统的神经影像学方法,通过磁共振成像(MRI)和脑电图(EEG)技术来获取数据。

研究工作表明,在进行决策时,大脑会激活其神经回路,如制衡系统,共同参与决策的制定。

同时,当我们做出决策时,不同时间内不同大脑区域的活动也会发生变化,这种变化对于如何做出明智的选择是至关重要的。

三、人类行为与决策的脑区人类行为和决策的神经基础,已经得到了相当的研究。

以下是一些神经科学领域已知的有关人类行为和决策的脑区:1. 奖励网络区奖励网络区是大脑通过自然反应和刺激反应来产生积极情绪的区域。

在奖励区所控制的神经过程中,大脑产生的多多少少都带有一定的情绪价值,比如愉悦、兴奋、满足和欣赏等。

奖励区的持续活动可以是神经休息状态,而突发性的活动则会产生杏仁核,而杏仁核一般会与恐惧、愤怒和自我保护感情联系在一起。

大脑中的奖赏系统海马体的奖赏学习功能

大脑中的奖赏系统海马体的奖赏学习功能大脑中的奖赏系统和海马体的奖赏学习功能奖赏系统是大脑中一组负责感知和调控奖赏行为的神经回路,其主要包括多巴胺神经元和相关的脑区,其中海马体在奖赏学习过程中扮演着重要的角色。

本文将探讨大脑中奖赏系统的基本原理以及海马体在奖赏学习中的功能。

一、奖赏系统的基本原理奖赏系统是通过奖赏的感知和反馈机制来调节动物行为的一种方式。

这一系统的核心部分是边缘系统和中脑多巴胺神经元。

当动物进行某种行为并得到奖赏时,多巴胺神经元会释放多巴胺,将奖赏信息传递给大脑的其他区域,从而产生愉悦感和动机驱动力。

奖赏系统在动物学习和行为决策中起到至关重要的作用。

通过奖赏的正性反馈,动物能够形成对某些行为的喜爱,并进一步加强这些行为。

同时,奖赏系统也参与到对奖赏价值的评估,帮助动物进行合理的行为选择。

二、海马体的奖赏学习功能在奖赏学习中,海马体扮演着一个关键的角色。

尽管海马体通常被认为是与记忆相关的大脑结构,但近年来的研究发现,它在奖赏学习中有着重要的功能。

1. 学习和记忆相关海马体作为一个重要的学习和记忆中心,参与着奖赏信息的存储和检索。

研究表明,当动物接受到奖赏刺激时,海马体的神经活动会发生变化,形成与奖赏相关的记忆痕迹。

这些奖赏记忆对于动物的行为选择和决策至关重要。

2. 背侧海马体的特殊功能海马体被分为头侧海马体和背侧海马体两部分,而背侧海马体在奖赏学习中的功能更为显著。

研究发现,背侧海马体神经元对奖赏信息的编码和记忆具有重要作用。

当动物接受到奖赏刺激时,背侧海马体的神经元会发出更多的兴奋活动,并对奖赏刺激进行编码和存储。

3. 奖赏行为与空间记忆的关联海马体不仅参与奖赏学习,还与空间记忆密切相关。

研究发现,海马体在奖赏行为的过程中,会对环境进行感知和记忆,帮助动物建立起奖赏行为和空间位置之间的联系。

这种空间记忆与奖赏行为的关联对于动物在特定环境中获取奖赏具有重要的意义。

三、奖赏系统和海马体的丧失与疾病关联奖赏系统和海马体的损伤或功能障碍与一些精神和神经疾病的发生相关。

去抑制进食者奖赏加工优势的认知与神经机制

抑制控制网络功能降低

1 2 3

抑制控制能力不足

去抑制进食者的抑制控制网络功能降低,使其难 以抑制对食物的诱惑和冲动性进食行为。

前扣带回皮层活性减弱

前扣带回皮层是抑制控制网络的关键区域,去抑 制进食者中该区域的活性减弱,影响了抑制控制 功能的正常发挥。

冲动性行为增加

抑制控制网络功能降低导致去抑制进食者更容易 表现出冲动性行为,包括过量进食和高热量食物 选择。

对生理健康的影响

肥胖

01

去抑制进食者往往摄入过多热量,容易导致肥胖,增加患心血

管疾病、糖尿病等疾病的风险。

代谢紊乱

02

过度进食可能导致代谢紊乱,如胰岛素抵抗、高血脂等,进而

影响整体健康。

消化系统负担

03

大量摄入食物可能加重消化系统的负担,导致胃肠功能紊乱、

胃炎等问题。

干预策略与前景

01

心理治疗

通过认知行为疗法、心理教育等 方式,帮助去抑制进食者建立健

研究目的与意义

研究目的

本研究旨在深入探讨去抑制进食者在奖赏加工过程中的认知与神经机制,以揭示 其过度进食行为的原因。

研究意义

通过揭示去抑制进食者的奖赏加工优势及其背后的认知与神经机制,有助于为肥 胖、饮食失调等相关疾病的预防和治疗提供新的思路和方法。

02

去抑制进食者的奖赏加工认知机制

奖赏感知敏感度增强

03

去抑制进食者奖赏加工的神经机制

大脑奖赏网络过度激活

奖赏系统敏感化

去抑制进食者的大脑奖赏网络对食物刺激表现出过度激活,导致 对食物的渴求和进食行为的增加。

多巴胺能神经元活动增强

奖赏网络中的多巴胺能神经元在去抑制进食者中表现出更高的活动 水平,进一步加剧了奖赏加工的优势。

人类行为决策相关脑区功能定位分析

人类行为决策相关脑区功能定位分析在人类的日常生活中,我们经常需要做出各种决策,包括简单的选择,如选择穿什么衣服,吃什么食物,以及更复杂的决策,如购买房屋、规划未来等。

人们的行为决策是一个复杂的过程,其中涉及多个脑区的协同作用。

本文将就人类行为决策相关脑区的功能进行分析,并探讨其定位在大脑中的作用。

1. 前额叶皮质(PFC):前额叶皮质是人类行为决策的核心脑区之一,也是高级认知功能的中心之一。

PFC分为背外侧前额叶皮质(dlPFC)和背内侧前额叶皮质(vlPFC)。

在决策过程中,dlPFC负责评估不同选择之间的潜在利益和风险,以及规划和执行适当的行动。

vlPFC则参与情感和奖赏的处理,调节决策过程中的情绪反应和动机。

2. 背侧前扣带回(DLPFC):DLPFC是前额叶皮质的一个重要区域,与注意力、工作记忆和灵活的推理能力有关。

DLPFC在决策中发挥着重要作用,特别是在需要进行复杂的思考和分析时。

该区域参与规划和执行决策,并对解决问题的不同策略进行归纳和选择。

3. 迷走神经(VN):迷走神经是自主神经系统的一部分,参与调节心率、消化功能和情绪反应。

研究表明,迷走神经与决策制定和调节情绪有关。

迷走神经的活动水平可以影响个体的情绪状态,从而影响决策过程中的风险偏好和行为选择。

4. 杏仁核(AMY):杏仁核是大脑中一个与情绪特别是害怕和厌恶有关的关键脑区。

在决策过程中,AMY参与评估潜在风险,对信息进行情感加工。

该区域在行为决策中可以发挥积极或消极的作用,根据情境的不同,可能增加或抑制个体对危险或奖赏的反应。

5. 背侧视丘(SC):背侧视丘是视觉系统的一部分,主要负责从外部环境中获取视觉信息。

在行为决策中,SC参与感知和处理外部环境的信息,并将这些信息传递给其他脑区进行综合分析。

该区域与空间定位和规避危险等决策过程密切相关。

6. 带状回(SGC):带状回也是前额叶皮质的一部分,参与多种认知和情绪过程。

在决策中,SGC起到整合和加工信息的作用,帮助个体对不同情境下的决策做出合理选择。

大脑中的意识探索大脑的奖赏中心

大脑中的意识探索大脑的奖赏中心大脑中的意识:探索大脑的奖赏中心意识是一个神秘而复杂的概念,对于科学家和哲学家们来说,它一直是个困扰且具有挑战性的问题。

虽然我们无法对意识进行精确定义,但我们可以通过研究大脑的奖赏中心来更好地理解意识的形成和表现。

一、引言意识是指人的主观体验和知觉。

虽然我们每个人都拥有意识,但我们对其产生的机制了解甚少。

直到近年来,神经科学的发展为研究意识提供了新的思路。

奖赏中心是大脑中一个关键的结构,它在意识的形成中扮演着重要的角色。

二、奖赏中心的基本概念奖赏中心位于大脑的边缘系统,主要由多巴胺神经元组成。

当我们获得满足和快乐时,奖赏中心会释放多巴胺,使我们感到愉悦。

这种刺激和反馈机制才是我们追求奖赏和意识的基础。

三、奖赏中心和意识的关系研究发现,奖赏中心与意识的产生密切相关。

当我们经历积极的体验时,奖赏中心活跃,多巴胺的释放使我们感到愉悦。

这种奖赏反馈会引起我们对经验的关注和意识的产生。

因此,我们可以说奖赏中心是意识产生的基础。

四、奖赏中心与意识障碍的关系奖赏中心的功能异常可能导致意识障碍。

例如,一些精神疾病患者的奖赏中心活跃度异常,导致他们缺乏对愉悦和快乐的感受,从而导致意识的丧失。

此外,药物滥用和成瘾也会导致奖赏中心功能紊乱,引发精神和意识上的问题。

五、意识与奖赏中心的相互作用意识和奖赏中心是相互作用的。

意识可以影响奖赏中心的活动,进而改变我们对不同刺激的反应。

同时,奖赏中心的活动也可以影响我们的意识状态,决定我们对外界体验的关注程度和情感体验的强度。

六、探索意识的未来研究随着技术的进步和研究方法的创新,我们对意识和奖赏中心的了解将不断深化。

未来的研究可以集中在以下几个方面:探索奖赏中心和意识的神经机制、研究意识与奖赏中心的遗传基础以及寻找影响意识和奖赏中心的有效治疗方法。

七、结论在大脑中,奖赏中心是探索意识的关键。

它参与意识的形成和表现,同时与意识障碍有着紧密的联系。

意识与奖赏中心相互作用,共同决定我们对世界的感知和体验。

人类大脑多巴胺系统对奖励行为的调控机制

人类大脑多巴胺系统对奖励行为的调控机制人类对奖励行为的追求和喜好可以追溯到远古时代,这种行为模式也是人类进化过程中的一种适应方式。

在人类大脑中,多巴胺系统扮演着关键的角色,调控着人类对奖励行为的感受和动机。

本文将深入探讨人类大脑多巴胺系统对奖励行为的调控机制。

多巴胺是一种神经递质,它主要负责调节和传递神经信号。

多巴胺系统由多个脑区组成,其中最为重要的是腹侧被盖核(ventral tegmental area,VTA)和伏隔核(nucleus accumbens,NAc)。

VTA是多巴胺神经元的主要来源,而NAc是多巴胺重新摄取和信号传递的重要区域。

奖励行为,比如食物摄入和性行为,会引起多巴胺神经元的活跃,导致大脑多巴胺水平的增加。

这种增加的多巴胺水平被认为是奖励行为的基础,使人们产生愉悦感和满足感。

例如,食物摄入后多巴胺水平的增加可以让人们感到满足和快乐。

由于多巴胺的作用,奖励行为对人类的行为与学习产生了重要影响。

多巴胺系统的调控机制可以通过奖励预测误差(reward prediction error,RPE)来解释。

RPE是指实际奖励与预期奖励之间的差异。

当实际奖励高于预期奖励时,多巴胺水平会升高;而当实际奖励低于预期奖励时,多巴胺水平会降低。

这种调节机制使得人类能够预测奖励,并对奖励行为产生动力和动机。

科学家们通过实验和研究发现,多巴胺系统对奖励行为的调控机制是非常复杂的。

在奖励行为中,多巴胺系统与其他神经递质系统和脑区之间存在广泛的相互作用。

例如,多巴胺系统与前额叶皮层、杏仁核、海马等脑区之间的连接与奖励行为密切相关。

前额叶皮层是人类大脑的决策中心,它与多巴胺系统之间的相互作用对奖励行为起着重要作用。

前额叶皮层通过调节多巴胺系统的活性来影响奖励行为。

正反馈回路中的多巴胺神经元会增加前额叶皮层的活跃度,从而加强对奖励行为的感受和动机。

相反,逆反馈回路中的多巴胺神经元则会减少前额叶皮层的活跃度,促使人们避免负面奖励行为。

奖赏预期对面孔情绪加工的影响一项事件相关电位研究

奖赏预期对面孔情绪加工的影响一项事件相关电位研究一、概述在现代认知科学领域中,情绪加工和奖赏预期被视为人类大脑信息处理的两个核心机制。

情绪加工涉及对外部刺激的情感反应和解读,而奖赏预期则关联于个体对潜在奖励的期待和动机。

越来越多的研究开始关注这两者之间的交互作用,特别是在面孔情绪加工这一复杂而精细的认知过程中。

面孔情绪加工是人类社交互动中的关键能力,它允许我们快速、准确地解读他人的情感状态,从而做出适当的反应。

而奖赏预期,作为一种强大的动机性信息,能够显著影响个体的注意分配和认知资源投入。

研究奖赏预期对面孔情绪加工的影响,不仅有助于我们深入理解人类情绪加工和动机机制的神经基础,还能为情绪障碍、社交障碍等心理疾病的诊断和治疗提供新的视角和思路。

本研究采用事件相关电位(ERPs)技术,通过精心设计的实验范式,系统地探讨了奖赏预期对面孔情绪加工的影响。

ERPs技术具有高时间分辨率的特点,能够实时记录大脑在加工不同情绪面孔时的电生理反应,从而揭示奖赏预期在面孔情绪加工过程中的神经机制。

在实验设计上,本研究采用了线索目标范式,通过操纵奖赏预期的有无,对比分析了被试在奖赏预期条件下和无奖赏预期条件下对正性、中性和负性面孔的情绪辨别任务表现。

结合行为数据和ERPs数据,全面评估了奖赏预期对面孔情绪加工的影响及其神经机制。

1. 奖赏预期与面孔情绪加工的重要性在人类的社交互动中,奖赏预期与面孔情绪加工都扮演着至关重要的角色。

奖赏预期是指个体对即将获得或可能获得的奖励的期待,它能够影响个体的认知、情感和行为反应。

而面孔情绪加工则是个体对他人面部表情进行识别、解读和反应的过程,它对于理解他人的情感状态、意图以及建立和维护社会关系具有重要意义。

奖赏预期与面孔情绪加工之间的紧密关联,使得它们在许多情境中相互交织、相互影响。

奖赏预期能够调节个体对面孔情绪的加工方式。

当个体预期将获得奖励时,他们可能会更加专注地注意他人的面孔表情,从而更准确地解读他人的情感状态。

奖励性行为在大脑中的神经机制

奖励性行为在大脑中的神经机制奖励性行为指的是能够激发个体积极情绪的行为,比如吃美食、获得奖励、与他人亲密接触等。

这些行为能够引发人们的快乐感和满足感,因此被认为是具有奖赏性的行为。

奖励性行为在大脑内部引发一系列神经反应和化学变化,使我们体验到愉悦和满足。

奖励性行为的神经机制主要涉及到两个重要的脑区——前额叶皮层(prefrontal cortex)和大脑内侧纹状体(ventral striatum)。

这两个脑区在奖励性行为中起到了至关重要的作用。

首先,前额叶皮层负责评估和规划奖励性行为的价值。

在奖励性行为发生前,前额叶皮层会对潜在的奖励价值进行评估,判断该行为是否值得追求。

在这个过程中,前额叶皮层会与其他脑区进行信息传递,以便做出更准确的决策。

一旦评估结果显示这个行为对个体有益,前额叶皮层就会释放一种神经递质叫多巴胺(dopamine),它是大脑中的一种重要化学信号物质,能够引起奖赏反应。

接下来多巴胺发挥作用的地方就是大脑内侧纹状体了。

大脑内侧纹状体位于大脑的基底节区域,与情感和动机有关的区域密切相关。

在面临奖励性行为时,多巴胺能够激活大脑内侧纹状体,引发愉悦感和满足感。

同时,大脑内侧纹状体还参与了奖励性行为的记忆和情感加工,增强了对奖赏性行为的记忆和回路强化。

除了前额叶皮层和大脑内侧纹状体,奖励性行为还涉及到其他脑区的互动。

下丘脑(hypothalamus)和杏仁核(amygdala)等区域在奖励性行为中发挥重要作用。

下丘脑参与奖励性行为的调节和控制,对奖励性行为的动机和取向起着重要作用。

杏仁核则负责加工和记忆与奖励相关的情感信息,对于奖励性行为的情感体验和记忆形成至关重要。

此外,神经递质多巴胺在奖励性行为中的作用也不能忽视。

除了前额叶皮层和大脑内侧纹状体,多巴胺还能通过其他通路间接影响奖励性行为。

例如,多巴胺通路与海马体(hippocampus)相连接,该通路参与了对奖励性行为的学习和记忆形成。

男性大脑的决策制定与风险承受能力的脑神经基础

男性大脑的决策制定与风险承受能力的脑神经基础近年来,随着神经科学和心理学的发展,人们对男性和女性大脑之间的差异越来越感兴趣。

尤其是在决策制定和风险承受能力方面,男性似乎表现出明显的优势。

本文将探讨男性大脑决策制定和风险承受能力的脑神经基础,并分析其可能的原因。

首先,研究显示男性在决策制定方面表现出更高的风险偏好。

这一现象可能与男性大脑中与认知加工相关的区域有关。

大脑皮层是决策制定的关键区域之一,其中前额叶皮层的功能尤为重要。

前额叶皮层在决策制定过程中与规划、判断和推理等认知能力密切相关。

研究发现,男性大脑的前额叶皮层相对于女性来说更大,这可能与男性在决策制定方面更倾向于冒险和追求高风险回报有关。

此外,男性大脑在情绪处理和脑内奖赏系统方面的差异也可能对其风险承受能力的表现产生影响。

神经递质多巴胺在脑内奖赏系统中起到重要作用,而男性大脑中多巴胺的释放量和受体密度都较高。

这意味着男性在面对激励和奖励时,会更强烈地感受到愉悦和满足,从而对冒险和高风险回报更为敏感。

这种对奖赏的感受可能使得男性更倾向于承受风险以追求更高的回报。

此外,性别激素对于男性大脑的决策制定和风险承受能力也起着重要作用。

男性体内睾丸激素睾酮的水平相对较高,而睾酮在男性大脑中的作用被认为与决策制定和风险行为密切相关。

研究发现,高水平的睾酮可能增加男性对奖赏的敏感性,进而影响其决策制定和风险承受行为。

然而,虽然男性在决策制定和风险承受能力方面表现出相对优势,但也存在一些限制。

例如,由于过度自信和过度乐观的倾向,男性可能更容易忽略风险和不利的因素。

此外,敏捷度和灵活性方面,女性在某些情况下可能更胜一筹。

因此,在实际决策和风险管理中,男女双方的优势都需要被充分考虑和整合。

综上所述,男性大脑的决策制定和风险承受能力与其脑神经基础密切相关。

男性大脑中与认知加工、情绪处理和脑内奖赏系统相关的区域,以及睾酮等性别激素的作用,可能在一定程度上解释了男性在决策制定和风险承受方面的优势。

神经科学与创造力:大脑如何激发创新

神经科学与创造力:大脑如何激发创新在探索创造力的奥秘时,我们不可避免地要深入到神经科学的领域。

创造力,这一人类心智的璀璨明珠,是艺术、科学、技术和文化进步的源泉。

然而,它是如何在大脑中被激发和孕育的呢?首先,我们需要理解大脑的基本构造。

大脑由两个半球组成,每个半球又分为四个叶:额叶、顶叶、颞叶和枕叶。

这些区域通过复杂的神经网络相互连接,共同协作,形成了我们的认知和情感基础。

在创造力的产生过程中,额叶扮演着至关重要的角色。

额叶的前部,尤其是前额叶皮层,与决策制定、规划和抽象思维紧密相关,这些都是创新思维的关键要素。

创造力的激发往往伴随着大脑的神经可塑性,即大脑结构和功能的改变以适应新的经验。

这种可塑性使得大脑能够形成新的神经连接,从而产生新的想法和解决问题的新方法。

研究表明,当人们进行创造性思考时,大脑的多个区域会同时活跃,包括前额叶、颞叶和顶叶。

这种跨区域的协同工作促进了信息的整合和新颖想法的产生。

此外,创造力与大脑的默认模式网络(DMN)也有密切关系。

DMN在大脑休息或进行内省时活跃,它涉及到自我相关的思考和记忆的检索。

当DMN与执行控制网络(ECN)相互作用时,可以促进思维的跳跃和创新思维的产生。

这种相互作用可能解释了为什么在放松状态下,如散步或淋浴时,人们更容易产生新的想法。

神经递质,如多巴胺和血清素,也在创造力的激发中扮演着重要角色。

多巴胺与奖赏、动机和学习相关,而血清素则与情绪调节和认知功能有关。

这些化学物质的平衡对于维持创造性思维的流畅性和灵活性至关重要。

最后,环境因素和个人经验也对创造力有着深远的影响。

一个支持性的环境,鼓励探索和冒险,可以促进大脑的神经可塑性。

而丰富的个人经验,如旅行、阅读和跨学科学习,可以为大脑提供更多的素材,从而激发更多的创新思维。

综上所述,创造力是大脑复杂网络相互作用的结果,涉及多个脑区、神经递质和环境因素。

通过理解这些相互作用,我们可以更好地培养和激发我们的创新能力,推动人类社会的进步。

奖赏、动机和行为脑科学的视角

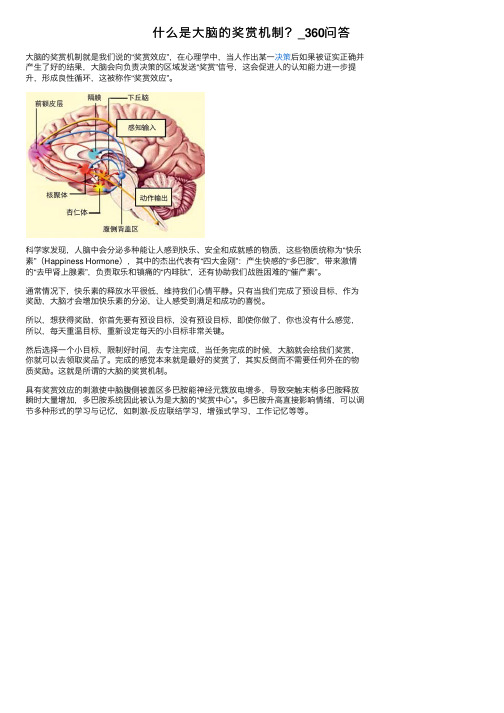

因此,奖赏(动机)系统中主要包含两条神经通路:中脑-边缘系统的多巴胺神经通路和中脑-皮质区域的多巴胺神经通路。

中脑-边缘系统的多巴胺神经通路主要包含与腹侧被盖区相连的伏隔核、隔膜、杏仁核和海马等大脑结构。

中脑-皮质区域的多巴胺神经通路主要包含内侧前额叶、前扣带回和边缘皮层等结构。

前者主要负责奖赏期望和学习,后者主要参与奖赏价值的编码和目标驱动行为。

其中,眶额皮质区域在奖赏加工过程中具有重要作用,其参与表征奖赏概率、奖赏风险以及奖赏结果信息。

教育过程中所使用的奖赏是多种形式的,包括金钱、食物,以及言语肯定等。

奖赏因其所呈现的条件或形式的不同会具有不同的意义,同时也会使个体产生不同的心理变化以及脑活动。

我们的研究发现眶额皮质后部主要表征初级奖赏的奖赏结果,眶额皮质前部主要表征次级奖赏的奖赏结果。

在奖赏预期方面,腹侧纹状体可以编码两种类型的奖赏,并且其表征的价值是奖赏的相对价值,而不是绝对价值。

那么奖赏(动机)系统是如何参与到个体的行为中去的呢?奖赏激励学生学习的机制是奖赏信息引起奖赏(动机)回路的活动,使个体产生愉悦的情绪体验,进而提高某种行为出现的可能性。

我们可以通过一个例子说明,一名学生最

奖赏(动机)系统的发展

尽管6岁儿童的大脑体积已经是成人大脑的90%,但大脑前额皮质

哐额皮质

伏隔核

海马

纹状体

黑质致密部(中脑)

腹侧被盖区

(中脑)

图2. 奖赏/动机系统关键脑区和神经通路

(修改自Schultz , 2015 Physiological Reviews)。

什么是大脑的奖赏机制?_360问答

什么是⼤脑的奖赏机制?_360问答

⼤脑的奖赏机制就是我们说的“奖赏效应”,在⼼理学中,当⼈作出某⼀决策后如果被证实正确并产⽣了好的结果,⼤脑会向负责决策的区域发送“奖赏”信号,这会促进⼈的认知能⼒进⼀步提升,形成良性循环,这被称作“奖赏效应”。

科学家发现,⼈脑中会分泌多种能让⼈感到快乐、安全和成就感的物质,这些物质统称为“快乐素”(Happiness Hormone),其中的杰出代表有“四⼤⾦刚”:产⽣快感的“多巴胺”,带来激情的“去甲肾上腺素”,负责取乐和镇痛的“内啡肽”,还有协助我们战胜困难的“催产素”。

通常情况下,快乐素的释放⽔平很低,维持我们⼼情平静。

只有当我们完成了预设⽬标,作为奖励,⼤脑才会增加快乐素的分泌,让⼈感受到满⾜和成功的喜悦。

所以,想获得奖励,你⾸先要有预设⽬标,没有预设⽬标,即使你做了,你也没有什么感觉,所以,每天重温⽬标,重新设定每天的⼩⽬标⾮常关键。

然后选择⼀个⼩⽬标,限制好时间,去专注完成,当任务完成的时候,⼤脑就会给我们奖赏,你就可以去领取奖品了。

完成的感觉本来就是最好的奖赏了,其实反倒⽽不需要任何外在的物质奖励。

这就是所谓的⼤脑的奖赏机制。

具有奖赏效应的刺激使中脑腹侧被盖区多巴胺能神经元簇放电增多,导致突触末梢多巴胺释放瞬时⼤量增加,多巴胺系统因此被认为是⼤脑的“奖赏中⼼”。

多巴胺升⾼直接影响情绪,可以调节多种形式的学习与记忆,如刺激-反应联结学习,增强式学习,⼯作记忆等等。

科学网_脑岛的功能-

科学网_脑岛的功能-

神经科学家们坦言,脑岛是性欲、恶心、骄傲、羞耻、内疚和补偿等社会情绪的源泉。

脑岛会引起道德感、共情以及对音乐的情绪反应。

脑岛的进化对人类与其他动物的差异产生了重要的作用。

研究脑岛的结构和进化为研究人和其他动物的巨大差异带来了启示。

脑岛会感知躯体状态,如饥饿和渴求,驱使人去拿取更多的三明治、香烟或者可卡因。

因此,脑岛的研究为治疗药物依赖、酒精症、焦虑和进食障碍提供了新的思路。

当人们想吸毒时、有痛感时、预期到痛感时、对别人产生共情时、听笑话时、看到别人露出恶心表情时,遭受社会性忽略被冷场时、听音乐时、决定不买某个东西时、看别人欺骗并决定惩罚别人时、评定巧克力偏好时,扫描他们的大脑会发现脑岛都会强烈激活。

脑岛本身接受躯体生理状态的信息,然后产生主观体验,比如进食以保持体内的平衡。

脑岛的信息再传导至其他决策相关的脑区,尤其是前扣带回和前额叶皮层。

脑岛接受来自内脏与皮肤感受器的信号。

这些感受器特异于某一种感觉,包括冷热感、痒、痛、味觉、饥饿、口渴、肌肉疼痛、内脏感觉以及空气感觉。

触觉和躯体对位置的感觉则在其他的脑区。

人类的脑岛在加工未发生的事件时十分重要。

当你决定是在寒冷的一天出去,你的躯体在你接触冷天气之前就做好了准备,比如血压升高以提高新陈代谢。

你的脑岛告诉你外面的冷天会是什么感觉。

脑岛的重要性使它成为多种治疗的理想目标,这包括药物和精细的生物反馈。

但抑制脑岛活性的方法必须要慎之又慎。

因为人们在失去吸烟、喝酒、嗑药的渴求后,可能同时失去了做爱、进食和工作的兴趣。

人类决策的神经生物学基础

人类决策的神经生物学基础人们做出决策的过程涉及到大量的神经元,异常复杂。

我们知道,人类的高级神经系统位于大脑中,其中负责做出选择的区域被称为前额叶皮层。

在这个区域,不同的神经元相互交流,协同工作,促使我们做出决策。

这个过程涉及到多个因素,比如个人感受、情境分析和竞争关系等。

如此多的参数相互作用带来的神经活动纷杂而错综复杂,预示着大脑决策过程的不可预测性和复杂性。

但是研究人员已经能够在这个范畴内找到一些可能的规律。

例如,前额叶皮层中的神经元被归类为特定的种类。

这些种类被称为神经元群,它们在特定的任务中群体激活。

这种群体激活使得一种被称为局部场电位(LFP)的电信号产生。

LFP信号反映了神经元群体在特定任务中的活动情况,提供了一个观察神经元群体整体表现的方式。

在人类决策的背景下,LFP的研究揭示了神经循环、激活和指向的深层结构,这些涉及到在人类决策时计算和整合信息在各种神经元和神经元组之间实现。

LFP可以研究,帮助我们“探究”大脑中的神经群体活动,从而更好地理解人类决策的神经生物学基础。

那么,LFP和人类决策的分析研究究竟意味着什么呢?一个明显的新颖发现是,在固定的决策任务中,不仅决策本身的神经机制可以改变,决策中观察到的神经元活动也可以随着学习的进行而改变。

例如,人们的决策、选择、计划和行动约束建立在先前的经验和学习之上。

有趣的是,LFP研究表明,信息的加工和选择在人类心理和神经科学中可能是由先天的个体差异、个体需求和特定因素控制的。

此外,在决策任务中,LFP也提供了一种突破点,可以帮助揭示语言、情感、视觉注意力和行动意向的神经机制。

例如,在决策的困难条件下,人们脑电波的反应通常会随着决策难度的增加而增加。

这可能代表了大脑在努力处理决策任务方面所花费的精力和时间。

综上所述,LFP研究开创了一个新的途径,用于理解人类决策的神经生物学基础。

LFP信号可以提供大量关于神经元群体行为的信息,使得我们可以对大脑中的决策和行为的神经机制进行更深入的研究。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

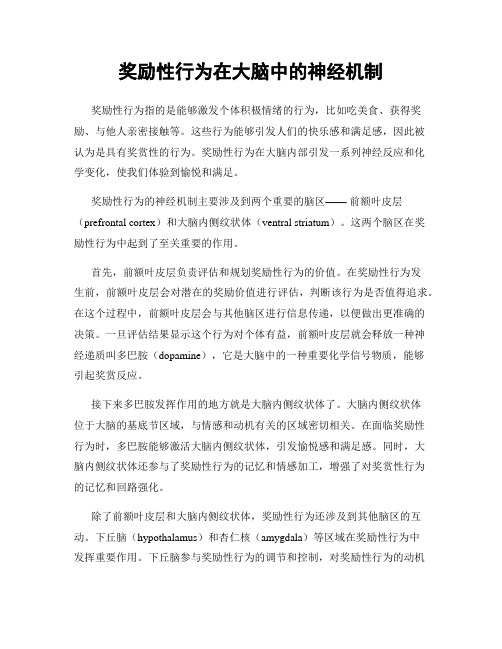

NEURAL REGENERATION RESEARCH Volume 8, Issue 35, December 2013doi:10.3969/j.issn.1673-5374.2013.35.009 [; ]Guo ZJ, Chen J, Liu SE, Li YH, Sun B, Gao ZB. Brain areas activated by uncertain reward-based decision-making in healthy volunteers. Neural Regen Res. 2013;8(35):3344-3352.3344 Corresponding author: Zongjun Guo, M.D., Chief physician, Professor, Special Health Care Department, Affiliated Hospital of Medical College, Qingdao University, Qingdao 266003, Shandong Province, China; the Institute of Brain Science & Human Resource Management of Qingdao University, Qingdao 266003, Shandong Province, China, guozjj@. Shien Liu, Master, Attending physician, the Institute of Brain Science & Human Resource Management of Qingdao University, Qingdao 266003, Shandong Province, China; Department ofMedical Imaging, Affiliated Hospital of Medical College, Qingdao University, Qingdao 266003, Shandong Province, China, shien_28@.Received: 2013-07-24 Accepted: 2013-10-20 (N20121113002)Acknowledgments: We are very grateful to Xu WJ from the Department of Medical Imaging, Affiliated Hospital of Medical College, Qingdao University, China, forassistance with the design of the methods.Brain areas activated by uncertain reward-based decision-making in healthy volunteers****Zongjun Guo 1, 2, Juan Chen 1, 2, Shien Liu 2, 3, Yuhuan Li 4, Bo Sun 4, Zhenbo Gao 41 Special Health Care Department, Affiliated Hospital of Medical College, Qingdao University, Qingdao 266003, Shandong Province, China2 The Institute of Brain Science & Human Resource Management of Qingdao University, Qingdao 266003, Shandong Province, China3 Department of Medical Imaging, Affiliated Hospital of Medical College, Qingdao University, Qingdao 266003, Shandong Province, China4 Qingdao Mental Health Center, Qingdao 266034, Shandong Province, ChinaResearch Highlights(1) Compared with decision-making in the …certain‟ condition, the ventrolateral prefrontal lobe, fro ntal pole of the prefrontal lobe, orbitofrontal cortex, precentral gyrus, inferior temporal gyrus, fusiform gyrus, supramarginal gyrus, inferior parietal lobule, and cerebellar posterior lobe exhibited greater activation in the …risk‟ condition. Compared w ith decision-making in the …certain‟ condition, the frontal pole of the prefrontal lobe was strongly activated in the …ambiguous‟ condition. Compared with the …risk‟ condition, the dorsolateral prefrontal lobe and cerebellar posterior lobe showed significa ntly greater activation in the …ambiguous‟ condition.(2) The activation of brain areas related to the processing information about loss increased with the degree of uncertainty.AbstractReward-based decision-making has been found to activate several brain areas, including the ven-trolateral prefrontal lobe, orbitofrontal cortex, anterior cingulate cortex, ventral striatum, and meso-limbic dopaminergic system. In this study, we observed brain areas activated under three degrees of uncertainty in a reward-based decision-making task (certain, risky, and ambiguous). The tasks were presented using a brain function audiovisual stimulation system. We conducted brain scans of 15 healthy volunteers using a 3.0T magnetic resonance scanner. We used SPM8 to analyze the location and intensity of activation during the reward-based decision-making task, with respect to the three conditions. We found that the orbitofrontal cortex was activated in the certain reward con-dition, while the prefrontal cortex, precentral gyrus, occipital visual cortex, inferior parietal lobe, ce-rebellar posterior lobe, middle temporal gyrus, inferior temporal gyrus, limbic lobe, and midbrain were acti vated during the …risk‟ condition. The prefrontal cortex, temporal pole, inferior temporal gyrus, occipital visual cortex, and cerebellar posterior lobe were activated during ambiguous deci-sion-making. The ventrolateral prefrontal lobe, frontal pole of the prefrontal lobe, orbitofrontal cortex, precentral gyrus, inferior temporal gyrus, fusiform gyrus, supramarginal gyrus, inferior parietal lo-bule, and cerebellar posterior lobe exhibited greater ac tivation in the …risk‟ than in the …certain‟ co n-dition (P < 0.05). The frontal pole and dorsolateral region of the prefrontal lobe, as well as the ce-rebellar posterior lobe, showed signifi cantly greater activation in the …ambiguous‟ condition co m-pared to the …risk‟ condition (P < 0.05). The prefrontal lobe, occipital lobe, parietal lobe, temporal lobe, limbic lobe, midbrain, and posterior lobe of the cerebellum were activated during deci-sion-making about uncertain rewards. Thus, we observed different levels and regions of activation for different types of reward processing during decision-making. Specifically, when the degree of reward uncertainty increased, the number of activated brain areas increased, including greater ac-tivation of brain areas associated with loss.Key Wordsneural regeneration; neuroimaging; decision-making; reward; uncertainty; cognitive processing; functional magnetic resonance imaging; brain; grants-supported paper; neuroregenerationINTRODUCTIONEach day, people are required to make deci-sions with varying degrees of risk. In cogni-tive neuroscience, decision-making is known as the cognitive process underlying the se-lection of a course of action among several alternative choices. The options are charac-terized by risk and ambiguity regarding dif-ferent types of rewards and losses[1].Although decision-making research origi-nated in the early 1900s, since the 1940s, scholars in this field have mainly taken a cognitive psychology approach[2]. Recently, the mechanisms underlying decision-making have been explored using techniques in neuropsychology and cognitive neuroscience, with a focus on functional brain activities related to evaluation of risk, leading to a de-cision[3-5]. Previous studies have identified several brain regions involved in deci-sion-making, including the orbital and frontal cortex, prefrontal lobe, anterior cingulate cortex, amygdale, hippocampus, limbic sys-tem, parietal lobe, cerebellum, and mid-brain[6-7]. These regions can be divided into two functions in terms of decision-making: “loss utility calculation” and “reward utility calculation”. Under different dec ision-making conditions, people analyze, judge, and dis-tinguish advantages and disadvantages of a choice, while brain areas related to “loss” and “reward” are activated. Ultimately, a choice indicating tendency or avoidance is made. Primary studies have shown that the ventro-lateral prefrontal lobe, orbitofrontal lobe, an-terior cingulate, ventral striatum, and meso-limbic dopaminergic system are involved in reward-based decision-making. When an expected gain is received or a practical out-come results in a gain, reward-related brain areas are activated, resulting in a tendency behavior[8-11]. However, several questions about decision-making remain. For instance, the role of degrees of uncertainty and dif-ferent levels of reward/loss in deci-sion-making is unclear, as is the neurophy-siological underpinnings of decision-making behavior.In this study, we used fMRI to study func-tional alterations of brain activation specific to different decision-making tasks[11-12]. Spe-cifically, we investigated whether activation in brain areas involved in reward-based de-cision-making would vary with degrees of uncertainty. and assessed the intensity of activation in brain regions related to gain/ reward and loss.RESULTSQuantitative analysis of participantsA total of 15 healthy participants were in-cluded in the final analysis.Baseline dataAll 15 participants were right handed, with normal cognitive function. Detailed baseline data are listed in Table 1.Brain areas activated by different reward- based decision-making conditions and activation intensityOur experimental methods were controlled using E-Prime 2.0 software. Using an audi-ovisual stimulation system, we presented a decision-making task with three conditions: certainty, risk, and ambiguity. We used fMRI to observe the activated brain areas and activation intensity under the different task conditions. The results showed that the orbitofrontal cortex was activated during decision-making trials in the …certain‟ cond i-tion, with an average activation intensity of 2.432 8 ± 0.194 9 (P< 0.05). In the …risk‟ and …a mbigu ity‟ trials, we observed activation in the prefrontal lobe (dorsolateral and ventro-lateral prefrontal lobe, frontal poleFunding: This study wassupported by the Scienceand TechnologyDevelopment Project ofShandong Province, China,No. 2011YD18045; theNatural Science Foundationof Shandong Province,China, No. ZR2012HM049;the Health Care FoundationProgram of ShandongProvince, China, No.2007BZ19; the FoundationProgram of TechnologyBureau of Qingdao, China;No. Kzd-03; 09-1-1-33-nsh.Author contributions: GuoZJ participated in the studydesign, provided guidance,reviewed the manuscript, andobtained funding. Chen Jwas in charge of datacollection and analysis, andwrote the manuscript. Liu SEparticipated in the collectionof imaging data. Li YH, SunB, and Gao ZB wereresponsible for samplecollection and data analysis.All authors approved the finalversion of the paper.Conflicts of interest: Nonedeclared.Ethical approval: This studywas approved by the EthicsCommittee at the AffiliatedHospital of the MedicalCollege of QingdaoUniversity, China.Author statements: Themanuscript is original, hasnot been previouslysubmitted, is not underconsideration by anotherpublication, has not beenpreviously published in anylanguage or any form,including electronic, andcontains no disclosure ofconfidential information orauthorship/patentapplication/funding sourcedisputations.3345of prefrontal lobe, and orbitofrontal cortex), precentral gyrus, limbic lobe, inferior parietal lobe, middle temporal gyrus, temporal pole, occipital lobe and visual cortex, cerebellar posterior lobe, and midbrain (Tables 2, 3, Figure 1A–C).Difference of activated brain areas in reward-based decision-making under uncertaintyCompared with the reward-based decision-making in the …certain‟ condition, the orbitofrontal cortex (BA11), ve n-trolateral prefrontal lobe (BA47), frontal pole of prefrontal lobe (BA10), precentral gyrus (BA6), inferior temporal gyrus and fusiform gyrus (BA20), inferior parietal lobule (BA40), supramarginal gyrus (BA40) and cerebellar posterior lobe showed significantly greater activation in the …risk‟ condition (P< 0.05). Compared with the re-ward-based decision-making in the …certain‟ condition, the frontal pole of the prefrontal lobe (BA10) showed significantly g reater activation in the …ambiguity‟ condition (P < 0.05). Compared with decision-making in the …risk‟ condition, the dorsolateral prefrontal lobe and the cere-bellar posterior lobe showed significantly greater activa-tion in the …ambiguity‟ condition (P < 0.05; Table 4, Figure 2A–C).33463347DISCUSSIONDecision-making encompasses certainty and uncertainty. Uncertain decisions can be sorted according to levels of risk and ambiguity, depending on the level of knowledge about the probability a particular result [2, 13]. Risk deci-sion-making refers to the possible states and corres-ponding outcomes of a choice. People can predict the probability of each state and the weight of its corres-ponding outcome. Under ambiguous decision-making conditions, it can be difficult to estimate the future prob-ability of the appearance of certain states.The cognitive processes underlying decision-making center around three main factors: perception and calcu-lation of external information, evaluation of gains or losses, and plan implementation. Thus, decision-making requires the coordination of multiple brain areas. Pre-vious studies have demonstrated that many brain re-gions are involved in decision-making, including the or-bitofrontal cortex, medial prefrontal cortex, anterior cin-gulate cortex, amygdale, and corpus striatum (including nucleus accumbens)[14-16]. Different elements of deci-sion-making, such as the evaluation and calculation of expected utility, have been associated with activation of specific brain regions [14-16]. Our experimental results in-dicated that the orbitofrontal cortex was activated during reward-based decision-making under …certain‟ conditions. In the certain condition, precise and reliable information was available to the participant, and so we expected to see activation in reward-related brain areas [14-16].Figure 1 Activated brain areas of healthy participants in the …certain‟ (A), …risk‟ (B) and …ambiguous‟ (C) conditions by functional MRI.Statistical results reached a probability threshold of P < 0.05. The threshold of the activated range was 10 pixels. Red: Activated areas.AB CRolls and colleagues[17] suggested that activation of the orbitofrontal cortex is positively correlated with gain number and expected value. During risky deci-sion-making, the uncertainty of the utility and expected outcomes is increased. Our results indicated that the dorsolateral and ventrolateral prefrontal lobe, frontal pole of prefrontal lobe, orbitofrontal cortex, precentral gyrus, limbic lobe, inferior parietal lobe, middle temporal gyrus, temporal pole, occipital lobe and visual cortex, cerebellar posterior lobe, and midbrain were activated during risky decision-making. Thus, it appears that these areas play a role in the calculation of utility, and thus perhaps these areas comprise a neural feedback loop in the brain re-garding risk-reward decision-making. In previous re-search, the orbitofrontal cortex has been associated with gain[18]. The occipital lobe is known to be activated when calculating visual arabic numbers, and is involved in primary information encoding, digital computing, and logical reasoning[19]. The parietal cortex has been found to encode the probability of a possible occurrence of a visual stimulus-coupled reward in economic deci-sion-making[19]. Activity in midbrain dopaminergic neu-rons, as well as the orbitofrontal cortex, insular cortex, and cingulate cortex, has been associated with probabil-ity and quantity of reward, such that activity increases with gain[17]. Tom et al[20] verified that during a gambling task, when the probability of either a loss or a gain was 50%, an increase in the frequency of gains was asso-ciated with enhanced midbrain dopaminergic activity, and vice versa. Another study found that losses were associated with activity in the inferior parietal lobule and cerebellum[18]. We found activation in the cerebellarFigure 2 Difference of activated brain areas in reward-based decision-making under uncertainty by functional MRI.(A) Activation in the …risk‟ condition was greater than that in the …certain‟ condition. (B) Activation was greater in the …ambiguous‟than the …certain‟ condition in healthy participants. (C) Activat ion was greater in the …ambiguous‟ than the …risk‟ condition in healthy participants. Red: Activated brain areas. Statistical results reached a probability threshold of P < 0.05. The threshold of the activated range was 10 pixels.A B C3348posterior lobe and inferior parietal lobule, which ap-peared to be related to the uncertainty of a rewarding opportunity when making a risky decision. The sense of uncertainty may have resulted in a negative perception about the outcome. The above-mentioned processing may have activated the cerebellar posterior lobe and inferior parietal lobule, as these regions are known to process negative events and calculate outcomes[21].Our experimental results demonstrated that deci-sion-making under ambiguous conditions mainly acti-vated the frontal pole of the prefrontal lobe, the orbito-frontal cortex, dorsolateral and ventrolateral prefrontal lobe, temporal pole of the temporal lobe, inferior tem-poral gyrus, primary visual cortex of the occipital lobe, the visual cortex, and the cerebellar posterior lobe. A previous study reported that the orbitofrontal cortex, amygdale, and prefrontal cortex were related to deci-sion-making under ambiguous condition[3]. Ambiguity in decision-making, that is, the uncertainty of an unknown probability, has been positively correlated with activation of the amygdale and orbitofrontal cortex, and negatively correlated with the activity in the striatal system[22]. This increased activity in the amygdale and orbitofrontal area may be related to fear and negative emotions associated with ambiguity. Likewise, the benefit-driving function of the striatal system decreases with ambiguity, along with positive perceptions and emotions[22]. Simultaneous ac-tivation of the amygdala, orbitofrontal area, and striatal system has been associated with escape behavior[23]. Therefore, ambiguity in decision-making increases avoidance behavior[23-24]. Under conditions of ambiguity, individuals may exhibit avoidance behavior, regardless of the probability of gains or losses[23-24]. Temporal lobe activation has been associated with the processing of large rewards through feedback learning and strategy transformation[25]. A previous study demonstrated that the degrees of ambiguity in an option affected deci-sion-making behavior, and, when faced with several dif-ferent ambiguous choices, people commonly exhibited anxiety, doubt, and aversive behavior[26]. The higher the degree of ambiguity, the more complicated the process of decision-making, and the greater the number of activated brain areas[27]. This was consistent with our results. Acti-vation of the cerebellum was associated with losses[20]. In sum, decision-making under ambiguous conditions ap-peared to elicit activation of the cerebellar posterior lobe, which was likely associated with an increase in negative perceptions induced by ambiguity[24, 27].The ventrolateral prefrontal lobe, frontal pole of the pre-frontal lobe, cerebellar posterior lobe, inferior temporal gyrus, fusiform gyrus, inferior parietal lobule, precentral gyrus, and supramarginal gyrus were more strongly ac-tivated during decision-making in risky compared with certain conditions. The dorsolateral prefrontal lobe and cerebellar posterior lobe exhibited significantly greater activation in the …ambiguous‟ compared with the …risky‟ condition. A previous study demonstrated that the frontal lobe is involved in information encoding, and is asso-ciated with reward/punishment processing, emotion, and motivation[27]. The prefrontal cortex has been found to play a role in the judgment component of decision- making[28]. The lateral prefrontal lobe is important for calculating future utility during decision-making[29]. It is possible that we observed greater activation of the infe-rior parietal lobule and cerebellar posterior lobe in the …ambiguous‟ condition, becaus e ambiguity can induce fear and behavioral avoidance[21]. Our results indicate that the different degrees of uncertainty in our task acti-vated several brain areas that play distinct roles in processing the return probability of decisions. Much of this processing appears to emerge from reward-related neural structures[20]. However, the precise mechanisms underlying reward-based decision-making require further investigation. The probability of a reward, degree of am-biguity, and size of a reward contribute to the degree of uncertainty in reward-related decision-making. Thus, we believe that our task simulated a real decision-making process. The present study utilized a GE 3.0T magnetic resonance scanner and brain function audiovisual sti-mulation system (SA-9800 system), which are advanced methods and instruments in China.SUBJECTS AND METHODSDesignA block design, random sampling study.Time and settingExperiments were conducted at the Department of Med-ical Imaging, Affiliated Hospital of Medical College, Qingdao University, China, from October 2011 to August 2012.SubjectsA total of 15 healthy individuals who underwent a medical examination at the Affiliated Hospital of the Medical Col-lege, Qingdao University, China, between October 2011 and August 2012 were randomly recruited for this study. There were 7 males and 8 females. The participants were right handed, 20–55 years of age (average 29.3 ±8.7 years), and had an average of 14.4 ±2.0 years of3349education. Cognitive ability was normal, and all partici-pants received a score of at least 30 on the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE)[30]. There was no history of heart, brain, liver, or kidney disease. The participants were emotionally stable, and did not suffer from depres-sion or anxiety, as measured by the Self-rating Anxiety Scale and Self-rating Depression Scale[31]. All partici-pants reported no family history of mental illness. All par-ticipants provided written informed consent. Before the experiment, we obtained demographic and contact in-formation for each participant.MethodsExperimental tasksStudy design: in accordance with previously published methods[32-33], stimuli were presented on a computer screen as participants lay in the fMRI machine. A box on the screen contained 10 poker cards, which included both diamonds and clubs. The cards randomly appeared on either the left or right side of the screen. The quantity of each kind of poker card in the box was indicated in the certain and risk conditions, but not indicated in the am-biguous condition. In each trial, the participant was asked to draw a poker card from the box according to the pre-dilection. If the participants selected the card on the left side, they pressed a button marked “1”. If the pa rticipants selected the card on the right side, they pressed a button marked “4”. After selection, the co mputer automatically displayed whether the participant had obtained the poker card that they had expected. If the participant obtained the poker card that he/she expected, they were given a reward of “+10”. If not, the participant was not given a reward or punishment, only a score of 0 for that trial. Scores were automatically recorded by the computer. Following this task, the participants were given the amount of money that they had won in RMB.There were three decision-making situations. (1) The box contained 10 clubs and 0 diamonds (reward-based decision-making in …certain‟ condition). (2) The box contained six diamonds and four clubs (reward-based decision-making in the …risk‟ condition). (3) Th e box contained four clubs and three diamonds, and the re-maining three poker cards were uncertain, either three diamonds, three clubs, two diamonds and one club, or one club and two diamonds (reward-based deci-sion-making in the …a m biguous‟ condition). A co ntrol task was designed to assess activation caused by vis-ual recognition of the clubs and diamonds: the box contained two kinds of poker cards (diamonds and clubs), which randomly appeared on both sides of the screen. The participant always was asked to draw a diamonds card from the box, but no points were scored, and no reward or punishment in this condition. All the subjects were informed the above-mentioned require-ment, scoring and reward conditions.Experimental designEach task contained a stimulation, feedback, and break component. The results of each trial were shown during the feedback component, and the screen displayed a fixation cross (“+”) during the break. Each task consisted of stimulation for 2 000 ms, feedback for 1 000 ms, and break for 1 000 ms. Each task was conducted five times, followed by a resting period of 12 000 ms. The control task contained the stimulation component for 2 000 ms and the break component 2 000 ms, and had no feed-back component. The experiment was conducted in three BLOCK cycles with two condition tasks followed by one control task in each cycle.Experimental procedureExperimental procedures were controlled using E-Prime 2.0 software (PST, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA). The data were loaded into a brain function audiovisual sti-mulation system (SA-9800 system; Shenzhen Sinorad Medical Electronics Inc., Shenzhen, Guangdong Prov-ince, China) and presented to the participants. Simulta-neously, we obtained data from the functional MRI. After receiving an explanation of the experimental procedure, the participants completed a practice session, and then completed the experiment. During the experiment, the participant was placed in a horizontal position on the bed of a GE 3.0T magnetic resonance scanner (GE Health-care, Bethesda, MD, USA), where they were able to see the screen, and give their response via a handheld con-troller. The brain function audiovisual stimulation system automatically recorded the participant responses, including reaction time, choice, and score after each selection.The GE 3.0T magnetic resonance scanner applied echo planar imaging and BOLD imaging. Scanning parame-ters were as follows: repetition time/echo time 2 000 ms/ 30 ms, flip angle 75°, field of view 230 × 230 mm, slice thickness 4 mm, yielding 33 slices in total with 205 sets of images. Total scanner time was 410 seconds. We used Excel and SPSS database for data analysis.Analysis of functional MRI dataA total of 602 trials were included in our analysis. We obtained 33 slices (no interval, whole brain) every 2 seconds. Using the Matlab platform (The MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA), the functional images were prepro-3350cessed and individually analyzed using SPM8 (Ham-mersmith hospital, Hammersmith, UK). Preprocessing of image space was conducted using time correction, head motion correction, spatial normalization, and Gaussian smoothing. The original data were screened, and data that did not exceed motor correction normalization (three-dimensional panning did not exceed 0.5 mm, and three-dimensional rotation did not exceed 0.5°) were statistically analyzed[11].Individual analysisLinear regression analysis of the matrix and real func-tional MRI data from each condition were performed using SPM8. Activated brain areas were obtained for each participant: activated area in the condition task (re-gion of interest-condition), and activated area in the con-trol task (region of interest-control). We used a t-test to compare the region of interest-task condition and the region of interest-control. The activated brain areas in each task were obtained for each participant during de-cision-making. The value range was identified using a t-test, with a significance threshold of P< 0.001. The threshold of the activated range was five pixels. That is, significantly activated areas comprised regions where five or more pixels were continuously activated.Group analysisUsing REST software (Beijing Normal University, Beijing, China), we analyzed the data for all participants for each task. The statistical significance threshold was P < 0.05. The threshold of the activated range was 10 pixels. The mean activated map was obtained, and overlaid on the Talairaeh template to localize the activated areas in the three task conditions.Intergroup analysisIndividual decision-making data in the …certain‟, …risk‟ and …ambiguous‟ conditions were grouped and compared using a two-sample t-test (P < 0.05). The relevant acti-vated brain areas were reported using the “report” command in the xjView program (Beijing Normal Univer-sity, China).Statistical analysisSPM8 software was utilized to analyze the functional images based on the MATLAB platform. REST software was employed to analyze and gain activated maps under the different decision-making conditions. The differences between the certain, risk, and ambiguous task conditions were compared using a two-sample t-test. Statistical results reached a probability threshold of P < 0.05. The threshold of the activated range was 10 pixels[33]. REFERENCES[1] Zhang K, Qi W, Guo AK. Towards decision-making theo-ries: the interface of neuroscience and economics.Science. 2008;60(3):5-9.[2] Kahneman D, Tversky A. Prospect theory: An analysis ofdecision under risk. In: Kahneman D, ed. Choices, Values, and Frames. New York: Cambridge University Press.2000.[3] Huettel SA, Stowe CJ, Gordon EM, et al. Neural signa-tures of economic preferences for risk and ambiguity.Neuron. 2006;49(5):765-775.[4] Wang L, Shen XY, Lin ZP. The research development ofrisk and ambugity decision making under the science of decision making. Dongnan Daxue Xuebao: Yixue Ban.2010;29(4):473-476.[5] Lubman DI, Yücel M, Pantelis C. Addiction, a condition ofcompulsive behaviour? Neuroimaging and neuropsycho-logical evidence of inhibitory dysregulation. Addiction.2004;99(12):1491-1502.[6] Paulus MP, Rogalsky C, Simmons A, et al. Increasedactivation in the right insula during risk-taking decision making is related to harm avoidance and neuroticism.Neuroimage. 2003;19(4):1439-1448.[7] Sanfey AG, Loewenstein G, McClure SM, et al. Neuroe-conomics: cross-currents in research on decision- making.Trends Cogn Sci. 2006;10(3):108-116.[8] Knutson B, Adams CM, Fong GW, et al. Anticipation ofincreasing monetary reward selectively recruits nucleus accumbens. J Neurosci. 2001;21(16):RC159.[9] Erk S, Spitzer M, Wunderlich AP, et al. Cultural objectsmodulate reward circuitry. Neuroreport. 2002;13(18): 2499-2503.[10] Shin R, Ikemoto S. Administration of the GABAA receptorantagonist picrotoxin into rat supramammillary nucleus induces c-Fos in reward-related brain structures. Supra-mammillary picrotoxin and c-Fos expression. BMC Neu-rosci. 2010;11:101.[11] Forbes EE, Christopher May J, Siegle GJ, et al. Re-ward-related decision-making in pediatric major depres-sive disorder: an fMRI study. J Child Psychol Psychiatry.2006;47(10):1031-1040.[12] Domenech P,Dreher JC. Decision threshold modulation inthe human brain. J Neurosci. 2010;30(43):14305-14317. [13] Trepel C, Fox CR, Poldrack RA. Prospect theory on thebrain? Toward a cognitive neuroscience of decision under risk. Brain Res Cogn Brain Res. 2005;23(1):34-50. [14] Christakou A, Brammer M, Giampietro V, et al. Right ven-tromedial and dorsolateral prefrontal cortices mediate adaptive decisions under ambiguity by integrating choice utility and outcome evaluation. J Neurosci. 2009;29(35): 11020-11028.[15] Shimizu K, Udagawa D. How can group experience in-fluence the cue priority? A re-examination of the ambigui-ty-ambivalence hypothesis. Front Psychol. 2011;2:265.3351。