MIT计量经济学lecture7

计量经济学课件全

11

数据

• 观测数据:主要是指统计数据和各种调查 数据。是所考察的经济对象的客观反映和 信息载体,是计量经济工作处理的主要现 实素材。

6

一、什么是计量经济学

• 计量经济学是利用经济理论、数学、统计推断 等工具对经济现象进行分析的一门社会科学。

• 计量经济学运用数理统计知识分析经济数据, 对构建于数理经济学基础之上的数学模型提供 经验支持,并得出数量结果。

• 计量经济学是以经济理论为前提,利用数学、 数理统计方法与计算技术,根据实际观测资料 来研究带有随机影响的经济数量关系和规律的 一门学科。

• 萨缪尔森:“经济计量学的定义为:在 理论与观测协调发展的基础上,运用相 应的推理方法,对实际经济现象进行数 量分析。”

5

一、什么是计量经济学

• 兰格:“经济计量学是经济理论和经济 统计学的结合,并运用数学和统计方法 对经济学理论所确定的一般规律给予具 体的和数量上的表示。”

• 克莱茵:“经济计量学是数学方法、统 计技术和经济分析的综合。就其字义来 讲,经济计量学不仅是指对经济现象加 以测量,而且包含根据一定的经济理论 进行计算的意思。”

GNP 10201.4 11954.5 14922.3 16917.8 18598.4 21662.5 26651.9 34560.5 46670 57494.9 66850.5 73142.7 76967.2

80579.36 88189.6

17

截面数据(cross-section data)

计量经济学专业知识讲座

14-34

类似地,可进行第三次、第四次迭代。 有关迭代旳次数,可根据详细旳问题来定。

一般是事先给出一种精度,当相邻两次1,2, ,L旳估计值之差不大于这一精度时,迭代

终止。 实践中,有时只要迭代两次,就可得到

较满意旳成果。两次迭代过程也被称为科克 伦—奥科特两步法。

Y1* 1 2 Y1

X

* 1

1 2 X1

该变换称为Prais-Winsten变换。

对于样本容量足够大,则不必进行这种变换。

14-24

使用广义差分方程应阐明旳几点:

双变量模型可推广到多变量模型; 差分变换可推广到高阶过程:从AR(1)到AR(2)、

AR(3)等。 使用上述措施必须懂得旳值,下面我们阐明

14-29

旳其他估计措施

Cochrane-Orcutt (科克伦-奥克特)迭代法; Cochrane-Orcutt 两步法 Durbin 两步法 Hildreth-Lu (希尔德雷斯-陆)搜索法 最大似然法

14-30

附:补充旳估计措施

科克伦-奥科特(Cochrane-Orcutt) 迭代法 杜宾(durbin)两步法

14-27

从Durbin-Watson d统计量中估计

因为: d2(1-’) ’ 1-d/2

根据上式,我们能够得到旳近似估计值。

14-28

从OLS残差et中估计

因为: ut=ut-1+vt

用样本误差e替代u,得: et=’et-1+vt

式中, ’ 是旳估计量。

尽管对小样本而言,是真实旳有偏估计,但伴 随样本容量旳增长,这个偏差会逐渐消失

进行OLS估计,得各Yj(j=i-1, i-2, …,i-l)前旳系数

《计量经济学导论》ch7

This is an example of program evaluation Treatment group (= grant receivers) vs. control group (= no grant)

Is the effect of treatment on the outcome of interest causal?

Multiple Regression Analysis: Qualitative Information

Comparing means of subpopulations described by dummies

Not holding other factors constant, women earn 2.51$ per hour less than men, i.e. the difference between the mean wage of men and that of women is 2.51$.

ences in education, experience and tenure between men and women

© 2012 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be scanned, copied or duplicated, or posted to a publicly accessible website, in whole or in part.

Holding other things fixed, married women earn 19.8% less than single men (= the base category)

© 2012 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be scanned, copied or duplicated, or posted to a publicly accessible website, in whole or in part.

计量经济学全套课件(完整)

2024/1/27

7

计量经济学研究目的与意义

2024/1/27

01

研究意义

02 推动经济学研究的定量化、精确化和科学 化。

03

为政府、企业和个人提供经济分析和决策 支持。

04

促进经济学的理论创新和实践应用。

8

2023

PART 02

经典线性回归模型

REPORTING

2024/1/27

9

一元线性回归模型

REPORTING 3

计量经济学定义与特点

01

计量经济学定义:计量经济学是运用数学、统计学和经济 学等方法,对经济现象进行定量分析和预测的一门学科。

02

计量经济学特点

03

以经济理论为基础,运用数学和统计学方法进行实证分析 。

2024/1/27

04

强调数据的收集、整理和分析,注重数据的可靠性和有效 性。

计量经济学模型估计

详细阐述如何在EViews软件中估计和检验各种计量经济学模型,如线 性回归模型、时间序列模型等。

26

Stata软件操作指南

Stata软件安装与启动

提供Stata软件的安装教程和启动指 南。

数据管理

介绍如何在Stata中进行数据的导入 、导出、合并和整理等操作。

2024/1/27

图形与可视化

等,以及针对模型问题的修正方法,如加权最小二乘法、广义最小二乘

法等。

12

2023

PART 03

广义线性模型与非线性模 型

REPORTING

2024/1/27

13

广义线性模型概述

2024/1/27

01

广义线性模型(GLM)是一种灵活的统计模型,用 于描述因变量与一组自变量之间的关系。

计量经济学全部课件

通过本课程的教学,要求学生掌握计量经 济学的基本理论和主要模型设定方法,熟悉计 量经济分析工作的基本内容和工作程序,能用 计量经济学软件包进行实际操作。本课程教学 采用课堂讲授与计算机实验相结合,适当运用 计算机多媒体课件和投影仪。教学目的不是要 求学生成为计量经济方法研究的专家,而是使 学生掌握计量经济学技术,并在经济分析、经 济管理和决策中正确使用这些技术,成为适应 现代化经济管理要求的人才。

35

库兹涅茨假设

但是,库兹涅茨对凯恩斯这种边际消费 倾向下降的观点持否定态度。他研究的 结论,消费与国民收入之间存在稳定的 上升比例。因此,上式只是根据凯恩斯 消费理论设定的消费模型。

16

二、计量经济学与经济统计 学、数理统计学

经济统计学主要涉及收集、加工、整理和计算 经济数据,并以列表或图示的形式提供经济数 据,而计量经济学则是研究经济关系本身。计 量经济研究中要使用经济统计学提供的经济数 据。数理统计学论述度量的方法,它是在实验 室控制试验的基础上发展起来的,不适用经济 关系,经过修正,使统计方法适用于经济生活 问题后,计量经济学就应用这些方法,称为计 量经济方法。

Y = b0 + b1 X

这里Y是消费支出,X是收入,b0和b1是常数或 参数,斜率系数b1表示MPC。 方程说明消费对收入的线性相关,这是数学模 型的一个例子。简单说,模型是一组数学方 程。假使模型只有一个方程,就称为单方程模 型;如果不止一个方程,就称为多方程模型或 联立方程模型。

29

可是消费函数的数学模型如上式所给出的,对 计量经济学家来说并无多大兴趣,因为它假设 消费与收入之间存在着严格的或确定的关系。 但是一船经济变量间的关系是不确定的。因 此,如果我们取得比如5000个中国家庭的消费 支出与可支配的收入(扣除税收后)的样本资 料,并把这些资料描绘在图纸上,以垂直轴作 为消费支出,水平轴作为可支配的收入,我们 决不会期望所有5000个观察值都恰好落在方程 的直线上。这是因为除收入外,还有其它变量 也影响消费支出。例如,家庭大小、家庭成员 年龄、家庭宗教信仰等等有可能对消费施加某 些影响。

计量经济学课件(全)

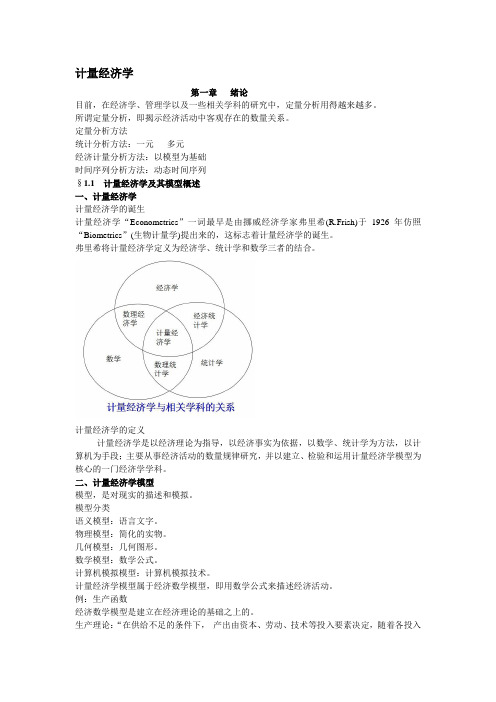

计量经济学第一章绪论目前,在经济学、管理学以及一些相关学科的研究中,定量分析用得越来越多。

所谓定量分析,即揭示经济活动中客观存在的数量关系。

定量分析方法统计分析方法:一元多元经济计量分析方法:以模型为基础时间序列分析方法:动态时间序列§1.1 计量经济学及其模型概述一、计量经济学计量经济学的诞生计量经济学“Econometrics”一词最早是由挪威经济学家弗里希(R.Frish)于1926年仿照“Biometrics”(生物计量学)提出来的,这标志着计量经济学的诞生。

弗里希将计量经济学定义为经济学、统计学和数学三者的结合。

计量经济学的定义计量经济学是以经济理论为指导,以经济事实为依据,以数学、统计学为方法,以计算机为手段;主要从事经济活动的数量规律研究,并以建立、检验和运用计量经济学模型为核心的一门经济学学科。

二、计量经济学模型模型,是对现实的描述和模拟。

模型分类语义模型:语言文字。

物理模型:简化的实物。

几何模型:几何图形。

数学模型:数学公式。

计算机模拟模型:计算机模拟技术。

计量经济学模型属于经济数学模型,即用数学公式来描述经济活动。

例:生产函数经济数学模型是建立在经济理论的基础之上的。

生产理论:“在供给不足的条件下,产出由资本、劳动、技术等投入要素决定,随着各投入要素的增加,产出也随之增加,但要素的边际产出递减。

” 建立初始模型初始模型的特点模型描述了经济变量之间的理论关系;通过模型可以分析经济活动中各因素之间的相互影响,从而为控制经济活动提供理论指导;认为这种关系是准确实现的;模型并没有揭示各因素之间的定量关系,因为参数未知。

模型的改进以1964-1984年我国工业生产活动的数据作为样本,估计得到:改进模型的特点1.用随机性的数学方程描述现实的经济活动与经济关系。

2.揭示了经济活动中各因素之间的定量关系。

3.可用于对研究对象进行深入的研究,如结构分析、生产预测等。

初始模型——数理经济学模型数理经济学模型:由确定性的数学方程所构 成,用以揭示经济活动中各因素间的理论关系。

计量经济学内容串讲PPT教学课件

系数不可以估计;不完全多重共线性时, Rank(X)=k,满秩,系数可以估计,但是 会导致模型估计结果出现问题。

2020/12/12

19

3注意:解释变量之间不存在线性关系, 并不意味着不存在非线性关系,当解 释变量之间存在非线性关系时,并不 违反无多重共线性的假定。

4 多重共线性常出现在时间序列数据 中,产生的原因:1. 经济变量之间具 有共同的变化趋势,2模型中包含滞后 变量(惯性作用) 3 截面数据在一定 情形下建立的模型4 抽样导致的偶然 样本

计量经济学内容串讲

2020/12/12

1

第一章 导论

2020/12/12

2

内容要点:

1 计量经济学的定义:计量经济学是以 经济理论和经济数据的事实为依据, 运用数学和统计学的方法,通过建立 数学模型来研究经济数量关系和规律 的一门经济学科。

2020/12/12

3

2 计量经济学研究步骤: 选择变量和数学关系式 —— 模型设定 确定变量间的数量关系 —— 估计参数

联立方程组模型

2020/12/12

43

1. 联立方程模型是用若干个相互关联的单一方程,同 时表示一个经济系统中经济变量相互联立依存性的 模型

2. 联立方程模型中的内生变量和外生变量。联立方程 模型中外生变量数值的变化能够影响内生变量的变 化,而内生变量却不能反过来影响外生变量

3. 联立方程模型中的联立方程偏倚 4. 联立方程模型的结构型模型和简化型模型

散点图), DW检验法(DW检验只能用于

检验随机误差项具有一阶自回归形式的自相

关问题。这种检验方法是建立经济计量模型

中最常用的方法,一般的计算机软件都可以

计算出DW 值,注意DW检验的缺点和局限

《计量经济学导论》课件

简单回归分析

通过单独的自变量和因变量建立线性回归方 程,了解不同变量之间的关系。

多元回归分析

通过多个自变量与因变量建立线性回归模型, 研究个体变量和经济体系之间关系的多元方 法。

假设检验

通过可靠的统计分析方法,掌握有强科学性 的实证检验体系,实现对数据有效性和可信 程度的评估。

三、回归模型的常见问题

计量经济学的应用领域

计量经济学应用广泛,涉及金融、政策、市场 等领域。它可以预测未来趋势、修复经济体系 中的异常、通过政策和决策可视化经济走向。

计量经济学的重要性

计量经济学是了解经济运行的内在规律和复杂 性的重要方式。它为预测未来趋势、指导政策

二、基础知识概述

数据类型

数字型、分类型、时间序列型等。掌握不同 数据类型的基本方法,可以更准确地描述数 字在数据分析和应用中的实际含义。

《计量经济学导论》PPT 课件

这堂课将带领您进入计量经济学的精彩世界,发掘数据背后的价值,实现对 数据的科学管理,提升对经济体系的理解和应用。快来开启您的计量之旅吧!

一、导言

什么是计量经济学?

计量经济学是一门探索kw【经济变量之间内在 关系】/kw的学问,可通过数据方法,深入研究 数字背后的规律,了解数字的真实含义。

1

多重共线性

独立变量之间具有高度相关性,导致

异方差性

2

难以准确度量变量对因变量的影响。

存在变量误差的果的可靠性和

准确性。

3

自相关性

存在观测值之间的相关性,导致参数

的不一致性和标准误的高估。

非常见事件与离群值

4

可能存在离群值和异常数据,影响分 析结果的稳健性和可靠性。

2 练习题解析和讨论

计量经济学讲稿(7-8章)

第7章 双变量模型:假设检验7.1 古典线性回归模型基本假定:A7.1 解释变量(X )与扰动项不相关 如果X 是确定性变量,该假定自然成立。

A7.2 扰动项的期望或均值为零。

即E(u i )=0 (7-1) A7.3 同方差假定,即Var(u i )为常数 (7-2) A7.4 无自相关假定,即随机扰动项之间是互不相关的。

即COV(u i ,u j )=0 当i ≠j 时 (7-3)7.2 普通最小二乘估计量的方差和标准差7.2.1 widget 一例中的方差和标准差及需求函数小结 Widget 的需求函数如下:())1203.0(7464.0ˆ=-=se 2.1576X 49.6670Y i i具体计算可用软件演示。

7.3 普通最小二乘估计量的性质OLS 估计量是最优线性无偏估计量。

b 1和b 2满足: (1)线性:即b 1和b 2是随机变量Y 的线性函数。

(2)无偏性,即()()()σσ22211ˆ===E B b E B b E 2 (3)最小方差性,即b 1的方差小与其他任何一个B 1的无偏估计量的方差 b 2的方差小与其他任何一个B 2的无偏估计量的方差蒙特卡洛试验,假定已知如下信息:i i i i i u 2.0X 1.5u X B B Y ++=++=21u i 服从N(0,4)分布。

假定X 有10个观察值:1,2,3,4,5,7,7,8,9,10。

试验及试验结果见 表7-2 蒙特卡洛试验 (书104页)7.4 OLS 估计量的抽样分布或概率分布为了求得OLS 估计量b 1和b 2的抽样分布,我们需要在增加一条假定,即:A7.5 在总体回归函数 i i i u X B B Y ++=21中,误差项u i 服从均值为零,方差为σ2的正态分布,即2(0,)iu N σ (7-17) 正态变量b 1和b 2的均值和方差为:;)var(;)var(),(~);,(~2222222122222112121∑∑∑==⋅==i b iib b b x b xn X b B N b B N b σσσσσσ (7-19)图 7-4 估计量分布的几何图形见书P107。

计量经济学第七讲vv

第七讲 虚拟变量一、含有一个虚拟变量的模型我们建立如下模型来研究学生成绩与复习时间及其学生性别的关系:010i i i i y x D ββαε=+++ (1) 其中,y 表示成绩,x 表示复习时间,而D 的取值是 10D ⎧⎪⎪⎨⎪⎪⎩=男生女生在这里,D 就是所谓的虚拟变量(也被称之为哑变量),它被用来反映定性因素。

模型(1)意味着:女生(D i =0)的成绩模型是:01i i i y x ββε=++男生(D i =1)的成绩模型是:001()i i i y x βαβε=+++显然,在复习时间及其其他影响成绩的因素(被包含在误差项中)一样的情况下,男生的成绩与女生成绩的差异是0α。

对模型(1)进行回归,如果原假设00α=被拒绝,则表明在控制了复习时间这个变量之后,学生性别对成绩有着显著影响。

模型(1)隐含了这么一个假定:尽管性别因素可能影响成绩,但学生复习效率(用1β衡量)与性别因素是无关的。

如果我们不认可这个假定,而是认为性别因素影响成绩的渠道可能就是性别因素对复习效率产生产生了影响,于是我们建立如下模型:011()i i i i i y x x D ββαε=+++ (2) 模型(2)意味着:女生(D i =0)的成绩模型是:01i i i y x ββε=++男生(D i =1)的成绩模型是:011()i i i y a x ββε=+++显然,在其他影响成绩的因素(被包含在误差项中)一样的情况下,男生复习效率与女生复习效率的差异是1α。

对模型(2)进行回归,如果原假设10α=被拒绝,则表明学生性别对复习效率有着显著影响。

当然我们还可以设定如下模型以反映更一般的情况:0011()i i i i i i a y D x x D ββαε+=+++ (3)笔记:一个问题是,我们到底应该选用哪一种含虚拟变量的模型?答案是经济理论与计量分析相结合。

不幸的是,有时经济学理论并未给模型的选择提供确切的指导,此时我们不得不首先考虑模型(3),因为它的包容性最大【注意到选择模型(3)也是有代价的,因为模型(3)待估计的参数最多,从而其自由度的耗费也是最大的】。

计量经济学讲稿

计量经济学讲稿第一章计量经济学概述1.1 什么是计量经济学一、计量经济学的产生计量经济学作为一门独立的学科产生于二十世纪30年代,是由挪威经济学家、第一届诺贝尔经济学奖得主R. Frisch 1926年仿照生物计量学一词提出来的。

半个多世纪以来,这门科学主要在资本主义中得到了发展,而且在理论和应用两个方面都取得了长足的进步。

今天的计量经济学已成为西方国家经济学的一个重要分支,其实用价值也正在越来越广泛的范围内表现出来。

著名经济学家诺贝尔经济学奖获得者萨谬尔森增经说:“第二次世界大战后的经济是经济计量的时代。

”我们不妨看看从1969年设立诺贝尔经济学奖起至1989年20年中共有27位获奖者,其中有15位是计量经济学家。

他们中有10位曾担任过世界计量经济学会会长,有4位是因为在计量经济学研究与应用方面有突出贡献而获奖。

这从一个侧面反映了计量经济学在经济科学中的地位。

1930年12月29日,一些国家的经济学家在美国成立了国际计量经济学会,学会的宗旨是“为了促进经济理论在与统计学和数学的结合中发展的国际学会”。

1933年该学会创办了会刊——《计量经济学》杂志。

R. Frisch在发刊词中有一段话:“用数学方法探讨经济学可以从好几个方面着手,但任何一方面都不能与计量经济学混为一谈。

计量经济学与经济统计学决非一码事;它也不同于我们所说的一般经济理论,尽管经济理论大部分都具有一定的数量特征;计量经济学也不应视为数学应用于经济学的同义词。

经验表明,统计学、经济理论和数学这三者对于真正了解现代经济生活中的数量关系来说,都是必要的。

三者结合起来,就有力量,这种结合便构成了计量经济学”。

计量经济学主要是以模型来研究经济现象,这种模型实际上是一组方程,模型所使用的数据有时间序列数据和截面数据1等。

这些数据不是从实验中得到的结果,而是经济学家被动的观测到的经济变量数据资料,而且经济变量大都是不独立的,因此,使得在经济分析中应用统计方法受到一定的限制。

计量经济学课件完整版

计量经济学课件完整版计量经济学课件完整版一、课程简介计量经济学是经济学领域的一门重要学科,它利用数学、统计学和经济学等学科的知识和方法,对经济现象进行量化和分析。

本课程将系统地介绍计量经济学的基本概念、方法和应用,旨在帮助学生掌握计量经济学的理论和实践技能,为进一步学习和研究经济学打下坚实的基础。

二、课程内容本课程共分为八个单元,包括:1、回归分析基础2、模型选择与优化3、时间序列分析4、面板数据分析5、多元回归分析6、离散选择模型7、因子分析8、协整分析每个单元都包括理论讲解、案例分析、软件操作和习题等内容,让学生全面了解和掌握计量经济学的方法和技术。

三、课程安排本课程共36学时,安排如下:1、理论讲解(20学时)2、软件操作与实践(10学时)3、习题课与答疑(6学时)四、教学目的通过本课程的学习,学生将能够:1、掌握计量经济学的基本概念和方法;2、熟练运用常用的计量经济学软件进行数据分析;3、了解计量经济学在经济学领域的应用;4、提高解决实际问题的能力,为未来的学习和工作打下基础。

五、教学方法本课程采用多种教学方法,包括:1、课堂讲解:教师通过讲解和演示,帮助学生掌握计量经济学的基本理论和方法;2、案例分析:通过分析实际案例,让学生了解计量经济学在实践中的应用;3、小组讨论:学生分组进行讨论和交流,加深对课程内容的理解;4、实践操作:通过上机实践,让学生掌握计量经济学软件的操作技巧。

六、考核方式本课程的考核方式包括:1、平时作业:完成课程对应的练习题和思考题,占总成绩的30%;2、期中考试:进行期中考试,考核学生对课程内容的掌握情况,占总成绩的30%;3、期末考试:进行期末考试,全面考核学生对课程内容的理解和应用能力,占总成绩的40%。

七、参考资料本课程推荐以下参考书籍:1、《计量经济学基础》(作者:高铁梅);2、《计量经济学》(作者:斯托克);3、《应用计量经济学》(作者:詹姆斯·H·斯托克等)。

悉尼大学计量经济学原理课件lec7ECMT5001sem12010

In This Lecture:⏹ Differences between simple and multiple regression ⏹ Examples of multiple regression functions⏹ Population regression model⏹ Sample regression model⏹ Assumptions of the model⏹ Estimation⏹ Finite sample properties of OLS⏹ Large sample properties of OLSMultiple Regression Analysis y = β0 + β1x1 + β2x2 + . . . βk x k + u3Examples⏹ Household Energy Usage(Electricity consumption)i = β1 + β2*(Electricity Price)i + β3*(Gas Price)i + u i⏹ Stock Prices (Stock Price)i = β1 + β2*(dividend)i + β3*(Return on Equity)i + u i⏹ Building approvals(Building approvals) = β1 + β2*(GDP)i + β3*(interest rate)i + u i⏹ Marketing Promotions(Sales)i = β1 + β2*(Price)i + β3*(Advertising)i + β4*( Promo 1)i + β5* (Promo 2)i + u i⏹ Examination Results(Average Mark)i = β1 + β2*(hours study per week)i + β3*(IQ)i + β4*(previous year average)i + u i ExamplesPopulation Regression Model⏹ The Population Regression Model is expressed asy = β0 + β1x + u (Simple)y = β0 + β1x1 + … + βK x K + u (Multiple) wherey is the dependent variable,x 1,…,xKare the K explanatory variables,u is the random component⏹ The corresponding population regression function isE(y|x) = β0 + β1x1 + … + βK x K6Population Parameters⏹ β0, …, βK are Regression Coefficients ⏹ β0 – the Intercept coefficient ⏹ β1 , …, βK – the Slope coefficients ⏹ The Intercept , β0, gives E(y |x ) when x 1 = x 2 = … = x K = 0 ⏹ The Slope , βk , gives the rate of change in E(y |x ) per unit change in x k (Δy /Δx k )for k = 1, …, K , for all other Δx j = 0Population Parameters⏹ Note that the slope coefficient, βk , for a particular variable x k , gives the effect of x k on y, holding all other x ’s fixed.⏹ It is the partial effect of variable x k⏹ Also, we have the variance parameter: σ2 = Var(u |x ) which is the variance of the random errors u10 Parallels with Simple Regression ⏹ β0 is still the intercept⏹ β1 to βk all called slope parameters⏹ u is still the error term (or disturbance)⏹ Still need to make a zero conditional mean assumption, so now assume that E(u|x 1,x 2, …,x k ) = 0⏹ Still minimizing the sum of squared residuals, so have k +1 first order conditionsSimple vs Multiple Regression⏹ In Simple Linear Regression we attempt to explain therelationship between our dependent variable y and a single explanatory variable x⏹ Multiple Linear regression models the relationshipbetween the dependent variable y, and multipleexplanatory variables x1, …, xKComputation⏹ Multiple regression is not usually done “by hand”⏹ Generally it’s done in a computer package⏹ The skills we’re attempting to achieve here are those ofinterpretation and exactitude⏹ The purpose is for you to be able to interpret regressionscalculated by others or yourself in the workplace⏹ The trick is to be able to critically analyse someoneelse’s work and know when it’s been done well!OLS Estimation⏹ OLS estimates have certain optimal properties⏹ Want to find a straight line that minimises the sum ofsquared vertical distances of points from the line.⏹ Method – minimises the sum of the squared errors.⏹ Consequence – points with extreme Y-values will have amore important effect on the position of the line.13“Partialling Out” continued ⏹ The previous equation implies that regressing y on x 1 and x 2 gives same effect of x 1 as regressing y on residuals from a regression of x 1 on x 2 ⏹ This means only the part of x i1 that is uncorrelated with x i2 are being related to y i so we’re estimating the effect of x 1 on y after x 2 has been “partialled out” or “removed.”MLR1. The value of Yi for given values of xi1, …, xiKisYi= β0 + β1x i1 + … +βK x iK + u i (Linearity)MLR2. We have a random sample of size n, {(xi1,…, xiK, yi):i = 1, 2, …,n}following the population model(random sampling)MLR3. In the sample (and population), none of the independent variables is constant, and there are no exact linear relationships among the independentvariables (No perfect collinearity)MLR4. The expected value of the random error u is zero forany values of x1,…,xKE(u | x1,…,xK) = 0 (zero conditional mean)MLR.5 The variance of the random error u isconstant: Var(u| x1,…,xK) = σ2(homoscedasticity)Note that MLR.5 also assumes that the covariancebetween any pair of errors ui and ujis cov(ui,uj| x1,…,xK)= 0 for i≠jAssumptions⏹ Assumption MLR.3 is new. It assumes there is no perfectcollinearity.⏹ If perfect collinearity exists then we can write one xvariable as a perfect linear function of the other xvariables. If this is the case, estimating the regression coefficients of these two variables is problematic.⏹ It also implies that there must be some variation in eachindividual x variable.Goodness-of-fit▪ How do we think about how well our sample regression line fits our sample data?▪ Can compute the fraction of the total sum of squares (SST) that is explained by the model, call this the R-squared of regression▪ R2 = SSE/SST = 1 – SSR/SSTMore about R-squared⏹ R2 can never decrease when another independentvariable is added to a regression, and usually willincrease⏹ Because R2will usually increase with the number ofindependent variables, it is not a good way to compare modelsExample 1: Real Estate Values Consider the linear regression modely = β1 + β2x2 + β3x3 + β4x4 + uwherey = Sale Price (dollars)= Appraised land value (dollars)x2x= Appraised improvements (dollars)3= Area (square feet)x4Example 1: Real Estate Values⏹ A property appraiser wants to model the relationshipbetween the sale price of a residential property in a mid-sized city and the following three independent variables: ❑ Appraised land value of property,❑ Appraised value of improvements (i.e. home value), and❑ Area of living space (i.e. home size).Example 1: Real Estate Values⏹ To fit the model the appraiser selected a random sampleof n = 20 properties from the thousands of properties that were sold that year.⏹ Use the method of least squares to estimate theunknown parameters β1, β2, β3, and β4, as well as theerror variance σ2⏹ Calculate and interpret the Coefficient of Determination,R2Real Estate Appraisal Data for 20 PropertiesSale Price Land Value ImprovementsValueAreaProperty # Y X2X3X41 68,900 5,960 44,967 1,8732 48,500 9,000 27,860 9283 55,500 9,500 31,439 1,1264 62,000 10,000 39,592 1,2655 116,500 18,000 72,827 2,2146 45,000 8,500 27,317 9127 38,000 8,000 29,856 8998 83,000 23,000 47,752 1,8039 59,000 8,100 39,117 1,20410 47,500 9,000 29,349 1,72511 40,500 7,300 40,166 1,08012 40,000 8,000 31,679 1,52913 97,000 20,000 58,510 2,45514 45,500 8,000 23,454 1,15115 40,900 8,000 20,897 1,17316 80,000 10,500 56,248 1,96017 56,000 4,000 20,859 1,34418 37,000 4,500 22,610 98819 50,000 3,400 35,948 1,07620 22,400 1,500 5,779 962 Source: Alachua County (Florida) Property Appraisers Office.Open Data in Gretl⏹ With Gretl click onFile → Open data → import…⏹ Select folder where the data is, and select whichspreadsheet the data is contained in.⏹ If the data is irregular or undated (cross-sectional), thendo not give the data a time-series of panel interpretation.⏹ Save session inSession files → save session asGretl – Estimating Regression Click onModel Ordinary Least SquaresExample 1: Real Estate Values The estimated regression equation that minimises the RSS isŶ = 1470.28 + 0.8145X2 + 0.8204X3+ 13.53X4The standard error of the regression is: s = 7919.483 r2 = 0.8974Example 1: Real Estate Values Interpretation:β1-hat– If the appraised property value is zero, theappraised improvements is zero, and the area of the home is zero, the expected sales price of $1470.28β2-hat– A one dollar increase in appraised land value leads on average to an increase in sales price of 81.4 centsholding all other variables constantExample 1: Real Estate Values β3-hat– A one dollar increase in appraisedimprovements leads on average to an increase in sales price of 82.0 cents holding all other variables constantβ4-hat– A one square foot increase in area of the homeleads on average to an increase in sales price of $13.53 holding all other variables constantExample 1: Real Estate Values⏹ The Coefficient of Determination isr2 = 0.8974⏹ The regression model explains 89.74% of the totalvariation in sales priceExample 1: Real Estate Values⏹ From the Gretl main menu, Select variable uhat1 → click onVariable → Normality test.Test for normality of uhat1:Doornik-Hansen test = 3.48063, with p-value 0.175465Shapiro-Wilk W = 0.931699, with p-value 0.16648Lilliefors test = 0.157615, with p-value ~= 0.21Jarque-Bera test = 0.392165, with p-value 0.821945⏹ Do not reject normalityDescriptive Stats with Gretl⏹ To obtain a set of descriptive statistics for the variablesin your data set: Select all variables → View → Summary statistics⏹ Summary statistics, using the observations 1 - 20Mean Median Minimum MaximumY 56660. 49250. 22400. 1.1650e+05X2 9213.0 8050.0 1500.0 23000.X3 35311. 31559. 5779.0 72827.X4 1383.3 1188.5 899.00 2455.0Std. Dev. C.V. Skewness Ex. kurtosisY 22691. 0.40049 1.1150 0.79782X2 5383.4 0.58433 1.2477 1.0687X3 15377. 0.43546 0.60369 0.36877X4 465.74 0.33668 0.89647 -0.36325Correlations with Eviews⏹ We may want to examine the individual correlationsbetween variables⏹ For example, we may want to check for the existence ofmulticollinearity between the X variables⏹ Or we may want to know which X variable is most/leastcorrelated with YCorrelations with Eviews⏹ View → Correlation matrix → Select which variables Correlation Coefficients, using the observations 1 - 205% critical value (two-tailed) = 0.4438 for n = 20Y X2 X3 X41.0000 0.7898 0.9157 0.8490 Y1.0000 0.7289 0.6889 X21.0000 0.7881 X31.0000 X4Properties of OLS⏹ We analyse the properties of the OLS estimator in thefinite sample context (when the number of observations, n<30). The main properties are:o Unbiasednesso Minimum variance⏹ We also look at the large sample properties of the OLSestimator (when the number of observations, n>30):o ConsistencyFinite sample properties of OLS Without loss of generality, we can discuss the properties of the OLS estimator using the simple regressionframework:y = β0 + β1x + uWhy do we use OLS estimators?Because they are B.L.U.E.B est, L inear, U nbiased E stimatorsOLS estimators are BLUEEfficient: lowest variance of all linear unbiased estimatorsUnbiased:E(bi)=Bi Linear functionsof the Y variable。

Lecture 7 Static Panels 高级计量经济学及Stata应用课件

2020/7/25

陈强 计量及Stata应用 (c) 2014

13

时间固定效应

• 个体固定效应模型解决了不随时间而变(time invariant)但随个体而异的遗漏变量问题。类似地, 引入时间固定效应,则可解决不随个体而变 (individual invariant)但随时间而变(time varying) 的遗漏变量问题。假设模型为

201493陈强计量及stata应用c201425显示面板数据统计特性的stata命令显示面板数据统计特性的stata命令面板数据的结构是否为平衡面板xtdes显示面板数据的结构是否为平衡面板xtsum显示组内组间与整体的统计指标xttabvarname显示组内组间与整体的分布频xttabvarname显示组内组间与整体的分布频率tab指的是tabulatextlinevarname对每个个体分别显示该变量的时间序列图

5 13265.93

11.

AZ 1985

12.

AZ 1986

13.

AZ 1987

14.

AZ 1988

1.86 1.78 1.72 1.68

6.5 13726.7

6.9 14107.33

6.2

14241

6.3 14408.08

2020/7/25

陈强 计量及Stata应用 (c) 2014

3

面板数据的分类

2020/7/25

陈强 计量及Stata应用 (c) 2014

11

LSDV 法

• 如果在原方程中引入(n-1)个虚拟变量(如果没有截 距项,则引入n个虚拟变量)来代表不同的个体, 则可以得到与上述离差模型同样的结果。因此, FE也被称为“最小二乘虚拟变量模型”(Least Square Dummy Variable Model,简记LSDV)。

计量经济学 卡特版课后第七章答案

CHAPTER 7Exercise Solutions141Chapter 7, Exercise Solutions, Principles of Econometrics, 3e 142EXERCISE 7.1(a) When a GPA is increased by one unit, and other variables are held constant, averagestarting salary will increase by the amount $1643 ( 4.66t =, and the coefficient is significant at α = 0.001). Students who take econometrics will have a starting salary which is $5033 higher, on average, than the starting salary of those who did not take econometrics (11.03t =, and the coefficient is significant at α = 0.001). The intercept suggests the starting salary for someone with a zero GPA and who did not take econometrics is $24,200. However, this figure is likely to be unreliable since there would be no one with a zero GPA . The R 2 = 0.74 implies 74% of the variation of starting salary is explained by GPA and METRICS(b) A suitably modified equation is 1234SAL GPA METRICS FEMALE e =β+β+β+β+ Then, the parameter 4β is an intercept dummy variable that captures the effect of genderon starting salary, all else held constant.()()1231423if = 0if = 1GPA METRICSFEMALE E SAL GPA METRICS FEMALE β+β+β⎧⎪=⎨β+β+β+β⎪⎩(c) To see if the value of econometrics is the same for men and women, we change the modelto 12345SAL GPA METRICS FEMALE METRICS FEMALE e =β+β+β+β+β×+ Then, the parameter 4β is an intercept dummy variable that captures the effect of genderon starting salary, all else held constant. The parameter 5β is a slope dummy variable that captures any change in the slope for females, relative to males.()()()12314235if = 0if = 1GPA METRICSFEMALE E SAL GPA METRICS FEMALE β+β+β⎧⎪=⎨β+β+β+β+β⎪⎩Chapter 7, Exercise Solutions, Principles of Econometrics, 3e 143EXERCISE 7.2(a) Considering each of the coefficients in turn, we have the following interpretations.Intercept : At the beginning of the time period over which observations were taken, on a day which is not Friday, Saturday or a holiday, and a day which has neither a full moon nor a half moon, the estimated average number of emergency room cases was 93.69.T : We estimate that the average number of emergency room cases has been increasing by 0.0338 per day, other factors held constant. This time trend has a t -value of 3.058 and a p -value = 0.0025 < 0.01.HOLIDAY : The average number of emergency room cases is estimated to go up by 13.86on holidays. The “holiday effect” is significant at the 0.05 level of significance. FRI and SAT : The average number of emergency room cases is estimated to go up by 6.9and 10.6 on Fridays and Saturdays, respectively. These estimated coefficients are both significant at the 0.01 level. FULLMOON : The average number of emergency room cases is estimated to go up by2.45 on days when there is a full moon. However, a null hypothesis stating that a full moon has no influence on the number of emergency room cases would not be rejected at any reasonable level of significance. NEWMOON : The average number of emergency room cases is estimated to go up by 6.4on days when there is a new moon. However, a null hypothesis stating that a new moon has no influence on the number of emergency room cases would not be rejected at the usual 10% level, or smaller. Therefore, hospitals should expect more calls on holidays, Fridays and Saturdays, and also should expect a steady increase over time.(b)There are very little changes in the remaining coefficients, or their standard errors, when FULLMOON and NEWMOON are omitted. The equation goodness-of-fit statistic decreases slightly, as expected when variables are omitted. Based on these casual observations the consequences of omitting FULLMOON and NEWMOON are negligible. (c) The null and alternative hypotheses are067:0H β=β= 167: or is nonzero.H ββThe test statistic is()2(2297)R U U SSE SSE F SSE −=−whereR SSE = 27424.19 is the sum of squared errors from the estimated equation with FULLMOON and NEWMOON omitted and U SSE = 27108.82 is the sum of squared errors from the estimated equation with these variables included. The calculated value of the F statistic is 1.29. The .05 critical value is (0.95,2,222) 3.307F =, and corresponding p -value is0.277. Thus, we do not reject the null hypothesis that new and full moons have no impact on the number of emergency room cases.Chapter 7, Exercise Solutions, Principles of Econometrics, 3e 144EXERCISE 7.3(a) The estimated coefficient of the price of alcohol suggests that, if the price of pure alcohol goes up by $1 per liter, the average number of days (out of 31) that alcohol is consumed will fall by 0.045.(b) The price elasticity at the means is given by24.780.0450.3203.49q pp q∂=−×=−∂(c) To compute this elasticity, we need q for married black males in the 21-30 age range. It is given by4.0990.04524.780.00005712425 1.6370.8070.0350.5803.97713q =−×+×+−+−=Thus, the price elasticity is24.780.0450.2803.97713q p p q ∂=−×=−∂ (d)The coefficient of income suggests that a $1 increase in income will increase the averagenumber of days on which alcohol is consumed by 0.000057. If income was measured in terms of thousand-dollar units, which would be a sensible thing to do, the estimated coefficient would change to 0.057.(e) The effect of GENDER suggests that, on average, males consume alcohol on 1.637 moredays than women. On average, married people consume alcohol on 0.807 less days than single people. Those in the 12-20 age range consume alcohol on 1.531 less days than those who are over 30. Those in the 21-30 age range consume alcohol on 0.035 more days than those who are over 30. This last estimate is not significantly different from zero, however. Thus, two age ranges instead of three (12-20 and an omitted category of more than 20), are likely to be adequate. Black and Hispanic individuals consume alcohol on 0.580 and 0.564 less days, respectively, than individuals from other races. Keeping in mind that the critical t -value is 1.960, all coefficients are significantly different from zero, except that for the dummy variable for the 21-30 age range.Chapter 7, Exercise Solutions, Principles of Econometrics, 3e 145EXERCISE 7.4(a) The estimated coefficient for SQFT suggests that an additional square foot of floor spacewill increase the price of the house by $72.79. The positive sign is as expected, and the estimated coefficient is significantly different from zero. The estimated coefficient for AGE implies the house price is $179 less for each year the house is older. The negative sign implies older houses cost less, other things being equal. The coefficient is significantly different from zero.(b) The estimated coefficients for the dummy variables are all negative and they becomeincreasingly negative as we move from D92 to D96. Thus, house prices have been steadily declining in Stockton over the period 1991-96, holding constant both the size and age of the house.(c) Including a dummy variable for 1991 would have introduced exact collinearity unless theintercept was omitted. Exact collinearity would cause least squares estimation to fail. The collinearity arises between the dummy variables and the constant term because the sum of the dummy variables equals 1; the value of the constant term.Chapter 7, Exercise Solutions, Principles of Econometrics, 3e 146EXERCISE 7.5(a)The estimated marginal response of yield to nitrogen is()()8.0112 1.9440.5677.444 3.888when 16.877 3.888when 26.310 3.888when 3E YIELD NITRO PHOS NITRO NITRO PHOS NITRO PHOS NITROPHOS ∂=−××−×∂=−==−==−=The effect of additional nitrogen on yield depends on both the level of nitrogen and the level of phosphorus. For a given level of phosphorus, marginal yield is positive for small values of NITRO but becomes negative if too much nitrogen is applied. The level of NITRO that achieves maximum yield for a given level of PHOS is obtained by setting the first derivative equal to zero. For example, when PHOS = 1 the maximum yield occurs when NITRO = 7.444/3.888 = 1.915. The larger the amount of phosphorus used, the smaller the amount of nitrogen required to attain the maximum yield. (b)The estimated marginal response of yield to phosphorous is()()4.80020.7780.5674.233 1.556when 13.666 1.556when 23.099 1.556when 3E YIELD PHOS NITRO PHOS PHOS NITRO PHOS NITRO PHOSNITRO ∂=−××−×∂=−==−==−= Comments similar to those made for part (a) are also relevant here.(c)(i) We want to test 0246:20H β+β+β= against the alternative 1246:20.H β+β+β≠The value of the test statistic is ()24624627.367se 2b b b t b b b ++===++At a 5% significance level, the critical t -value is c t ± where (0.975,21) 2.080c t t ==. Since t > 2.080 we reject the null hypothesis and conclude that the marginal product ofyield to nitrogen is not zero when NITRO = 1 and PHOS = 1.(ii) We want to test 0246:40H β+β+β= against the alternative 1246:40H β+β+β≠.The value of the test statistic is()2462464 1.660se 4b b b t b b b ++===−++Since |t| < 2.080 (0.975,21)t =, we do not reject the null hypothesis. A zero marginal yieldwith respect to nitrogen is compatible with the data when NITRO = 1 and PHOS = 2.Chapter 7, Exercise Solutions, Principles of Econometrics, 3e 147Exercise 7.5(c) (continued)(c)(iii) We want to test 0246:60H β+β+β= against the alternative 1246:60H β+β+β≠.The value of the test statistic is()24624668.742se 6b b b t b b b ++===−++Since |t| > 2.080 (0.975,21)t =, we reject the null hypothesis and conclude that themarginal product of yield to nitrogen is not zero when NITRO = 3 and PHOS = 1.(d) The maximizing levels NITRO ∗ and PHOS ∗ are those values for NITRO and PHOS suchthat the first-order partial derivatives are equal to zero.()()35620E YIELD PHOS NITRO PHOS ∗∗∂=β+β+β=∂()()24620E YIELD NITRO PHOS NITRO ∗∗∂=β+β+β=∂The solutions and their estimates are 253622645228.011(0.778) 4.800(0.567)1.7014(0.567)4( 1.944)(0.778)NITRO ∗ββ−ββ××−−×−===β−ββ−−×−−34262264522 4.800( 1.944)8.011(0.567)2.4654(0.567)4( 1.944)(0.778)PHOS ∗ββ−ββ××−−×−===β−ββ−−×−−The yield maximizing levels of fertilizer are not necessarily the optimal levels. Theoptimal levels are those where the marginal cost of the inputs is equal to the marginal value product of those inputs. Thus, the optimal levels are those for which()()PHOS PEANUTS E YIELD PRICE PHOS PRICE ∂=∂ and ()()NITROPEANUTSE YIELD PRICE NITRO PRICE ∂=∂Chapter 7, Exercise Solutions, Principles of Econometrics, 3e 148EXERCISE 7.6(a) The model to estimate is()()112323ln +PRICE UTOWN SQFT SQFT UTOWN AGE POOL FPLACE e=β+δ+β+γ×β+δ+δ+The estimated equation, with standard errors in parentheses, isn ()()()()()()ln 4.46380.33340.035960.003428(se)0.02640.03590.001040.001414PRICE UTOWN SQFT SQFT UTOWN =++−×()()()20.0009040.018990.0065560.86190.0002180.005100.004140AGE POOL FPLACER −++=(b) In the log-linear functional form 12ln(),y x e =β+β+ we have21dy dx y=β or 2dydx y =β Thus, a 1 unit change in x leads to a percentage change in y equal to 2100×β.In this case2311PRICE UTOWNSQFT PRICE PRICE AGE PRICE∂=β+γ∂∂=β∂Using this result for the coefficients of SQFT and AGE , we find that an additional 100 square feet of floor space increases price by 3.6% for a house not in University town; a house which is a year older leads to a reduction in price of 0.0904%. Both estimated coefficients are significantly different from zero. (c) Using the results in Section 7.5.1a,()2ln()ln()100100%poolnopool PRICEPRICE PRICE −×=δ×≈Δan approximation of the percentage change in price due to the presence of a pool is 1.90%. Using the results in Section7.5.1b,()21001100pool nopool nopool PRICE PRICE e PRICE δ⎛⎞−×=−×⎜⎟⎜⎟⎝⎠the exact percentage change in price due to the presence of a pool is 1.92%.Chapter 7, Exercise Solutions, Principles of Econometrics, 3e 149Exercise 7.6 (continued)(d) From Section 7.5.1a,()3ln()ln()100100%fireplacenofireplace PRICEPRICE PRICE −×=δ×≈Δan approximation of the percentage change in price due to the presence of a fireplace is 0.66%.From Section 7.5.1b,()31001100fireplace nofireplace nofireplace PRICE PRICE e PRICE δ⎛⎞−×=−×⎜⎟⎜⎟⎝⎠the exact percentage change in price due to the presence of a fireplace is also 0.66%. (e)In this case the difference in log-prices is given by()n ()n ()2525ln ln 0.33340.003428250.33340.003428250.2477utown noutown SQFT SQFT PRICE PRICE UTOWN UTOWN ==−=−××=−×= and the percentage change in price attributable to being near the university, for a 2500square-feet home, is()0.2477110028.11%e−×=Chapter 7, Exercise Solutions, Principles of Econometrics, 3e 150EXERCISE 7.7(a) The estimated equation isn ()()()()()()()2ln 8.9848 3.7463 1.1495 1.2880.4237 (se)0.64640.57650.44860.60530.1052 1.4313 0.84280.1562SAL1APR1APR2APR3DISP DISPAD R =−++++=(b) The estimates of2β, 3β and 4β are all significant and have the expected signs. The sign of 2β is negative, while the signs of the other two coefficients are positive. These signs imply that Brands 2 and 3 are substitutes for Brand 1. If the price of Brand 1 rises, then sales of Brand 1 will fall, but a price rise for Brand 2 or 3 will increase sales of Brand 1. Furthermore, with the log-linear function, the coefficients are interpreted as proportionalchanges in quantity from a 1-unit change in price. For example, a one-unit increase in the price of Brand 1 will lead to a 375% decline in sales; a one-unit increase in the price of Brand 2 will lead to a 115% increase in sales. These percentages are large because prices are measured in dollar units. If we wish toconsider a 1 cent change in price – a change more realistic than a 1-dollar change – then the percentages 375 and 115 become 3.75% and 1.15%, respectively. (c) There are three situations that are of interest. (i) No display and no advertisement{}11234exp SAL1APR1APR2APR3Q =β+β+β+β=(ii) A display but no advertisement{}{}2123455exp exp SAL1APR1APR2APR3Q =β+β+β+β+β=β(iii) A display and an advertisement{}{}3123466exp exp SAL1APR1APR2APR3Q =β+β+β+β+β=βThe estimated percentage increase in sales from a display but no advertisement isn n n 210.423751exp{}100100(1)10052.8%Q b Q SAL1SAL1e Q SAL1−−×=×=−×=Chapter 7, Exercise Solutions, Principles of Econometrics, 3e 151Exercise 7.7(c) (continued)(c) The estimated percentage increase in sales from a display and an advertisement isn n n 311.431361exp{}100100(1)100318%Q b Q SAL1SAL1e Q SAL1−−×=×=−×=The signs and relative magnitudes of 5b and 6b lead to results consistent with economiclogic. A display increases sales; a display and an advertisement increase sales by an even larger amount.(d) The results of these tests appear in the table below.Part 0H Test Value Degrees of Freedom 5% Critical ValueDecision(i) β5 = 0 t = 4.03 46 2.01 Reject H 0 (ii) β6 = 0 t = 9.17 46 2.01 Reject H 0 (iii) β5 = β6 = 0 F = 42.0 (2,46) 3.20 Reject H 0 (iv)β6 ≤ β5t = 6.8646 1.68 Reject H 0(e) The test results suggest that both a store display and a newspaper advertisement will increase sales, and that both forms of advertising will increase sales by more than a store display by itself.Chapter 7, Exercise Solutions, Principles of Econometrics, 3e 152EXERCISE 7.8(a) The estimated equation, with standard errors in parentheses, isn 215.45970.2698 2.35820.4391(se) (0.2537)(0.0868)(0.2629)PRICEAGE NET R =+−=All estimated coefficients are significantly different from zero. The intercept suggests thatthe average price of CDs that have a 1999 copyright and are not sold on the internet is $15.46. For every year the copyright date is earlier than 1999, the price increases by 27 cents. For CDs sold through the internet, the price is $2.36 cheaper. The positive coefficient of AGE supports Mixon and Ressler’s hypothesis. (b) The estimated equation, with standard errors in parentheses, isn 215.52880.7885 2.35690.4380(se) (0.2424)(0.2567) (0.2632)PRICEOLD NET R =+−=Again, all estimated coefficients are significantly different from zero. They suggest thatthe average price of new releases, not sold on the internet, is $15.53. If the CD is not a new release, the price is 79 cents higher. If it is purchased over the internet, the price is $2.36 less. The positive coefficient of OLD supports Mixon and Ressler’s hypothesis.Chapter 7, Exercise Solutions, Principles of Econometrics, 3e 153EXERCISE 7.9The estimated coefficients and their standard errors (in parenthesis) for the various parts ofthis question are given in the following table.Variable (a) (b) (c) (f) (g) Constant (β1) 128.98* 342.88* 161.47 109.72 98.48(34.59) (72.34) (120.7) (135.6) (179.1)2()AGE β −7.5756* −2.9774 −2.0383 −1.7200 (2.317) (3.352) (3.542) (4.842) 3()INC β 1.4577* 2.3822* 9.0739* 18.325 22.104(0.5974) (0.6036) (3.670) (11.49) (40.26)4()AGE INC ×β −0.1602 −0.6115 −0.9087 (0.0867) (0.5381) (3.079)25()AGE INC ×β 0.0055 0.0131 (0.0064) (0.0784)36()AGE INC ×β −0.000065 (0.000663) SSE 819286 635637 580609 568869 568708 N K − 38 37 36 35 34* indicates a t -value greater than 2.(a) See table.(b) The signs of the estimated coefficients suggest that pizza consumption responds positivelyto income and negatively to age, as we would expect. All estimated coefficients are greater than twice their standard errors, indicating they are significantly different from zero using one or two-tailed tests. We note that scaling the income variable (dividing by 1000) has increased the coefficient 1000 times. (c) To comment on the signs we need to consider the marginal effects()()24E PIZZA INC AGE ∂=β+β∂()34E PIZZA AGE INC∂=β+β∂We expect β3 > 0 and β4 < 0 implying that the response of pizza consumption to incomewill be positive, but that it will decline with age. The estimates agree with these expectations. Negative signs for b 2 and b 4 imply that, as someone ages, his or her pizza consumption will decline, and the decline will be greater the higher the level of income.Chapter 7, Exercise Solutions, Principles of Econometrics, 3e 154Exercise 7.9(c) (continued)(c) The t value for the age-income interaction variable is t = −0.1602/0.0867 = −1.847.Critical values for a 5% significance level and one and two-tailed tests are, respectively, (0.05,36) 1.688t =− and (0.025,36) 2.028t =−. Thus, if we use the prior information β4 < 0, thenwe find the interaction coefficient is significant. However, if a two-tailed test is employed, the estimated coefficient is not significant. The coefficients of INC and (INC × AGE ) have increased 1000 times due to the effects of scaling.(d) The hypotheses areH 0: β2 = β4 = 0andH 1: β2 ≠ 0 and/or β4 ≠ 0The value of the F statistic under the assumption that H 0 is true is()()()81928658060927.4058060936R U U SSE SSE J F SSE T -K −−===The 5% critical value for (2, 36) degrees of freedom is F c = 3.26 and the p -value of the testis 0.002. Thus, we reject H 0 and conclude that age does affect pizza expenditure. (e) The marginal propensity to spend on pizza is given by()34E PIZZA AGE INC∂=β+β∂Point estimates, standard errors and 95% interval estimates for this quantity, for different ages, are given in the following table.Point Standard Confidence Interval AgeEstimate Error Lower Upper20 5.870 1.977 1.861 9.878 30 4.268 1.176 1.882 6.653 40 2.665 0.605 1.439 3.892 50 1.063 0.923 −0.8092.935The interval estimates were calculated using (0.975,36) 2.0281c t t ==. As an example of how the standard errors were calculated, consider age 30. We have()n ()n ()n ()n ()23434344var 30var 30var 230cov ,13.4669000.0075228600.31421 1.38392se 30 1.1763b b b b b b b b +=++×=+×−×=+==The corresponding interval estimate is4.268 ± 2.028 × 1.176 = (1.882, 6.653)Chapter 7, Exercise Solutions, Principles of Econometrics, 3e 155Exercise 7.9(e) (continued)(e)The point estimates for the marginal propensity to spend on pizza decline as age increases, as we would expect. However, the confidence intervals are relatively wide indicating that our information on the marginal propensities is not very reliable. Indeed, all the confidence intervals do overlap. (f) This model is given by212345+PIZZA INC AGE AGE INC AGE INC e =ββ+β+β×+β×+The marginal effect of income is now given by()2245+E PIZZA AGE AGE INC∂=β+ββ∂If this marginal effect is to increase with age, up to a point, and then decline, then β5 < 0. The sign of the estimated coefficient b 5 = 0.0055 did not agree with this anticipation. However, with a t value of t = 0.0055/0.0064 = 0.86, it is not significantly different from zero.(g)Two ways to check for collinearity are (i) to examine the simple correlations between each pair of variables in the regression, and (ii) to examine the R 2 values from auxiliary regressions where each explanatory variable is regressed on all other explanatory variables in the equation. In the tables below there are 3 simple correlations greater than 0.94 in part (f) and 5 in part (g). The number of auxiliary regressions with R 2s greater than 0.99 is 3 for part (f) and 4 for part (g). Thus, collinearity is potentially a problem. Examining the estimates and their standard errors confirms this fact. In both cases there are no t -values which are greater than 2 and hence no coefficients are significantly different from zero. None of the coefficients are reliably estimated. In general, including squared and cubed variables can lead to collinearity if there is inadequate variation in a variable.Simple CorrelationsAGE AGE INC ×2AGE INC × 3AGE INC ×INC 0.4685 0.9812 0.9436 0.8975 AGE0.5862 0.6504 0.6887 AGE INC × 0.9893 0.9636 2AGE INC ×0.9921R 2 Values from Auxiliary RegressionsLHS variableR 2 in part (f) R 2 in part (g)INC0.99796 0.99983 AGE0.68400 0.82598 AGE INC × 0.99956 0.99999 2AGE INC × 0.99859 0.999993AGE INC × 0.99994Chapter 7, Exercise Solutions, Principles of Econometrics, 3e 156EXERCISE 7.10(a) The estimated equation with gender (FEMALE ) included, and with standard errors written in parentheses, isn ()()()()461.86408.18280.0024190.2581 (se)51.3441 1.55010.000427.7681PIZZA AGE INCOME FEMALE =−+−The t -value for gender is 190.258127.7681 6.8517t =−=− indicating that it is a relevantexplanatory variable. Including it in the model has led to substantial changes in the coefficients of the remaining variables.(b) When level of educational attainment is included the estimated model, with the standarderrors in parentheses, becomesn ()()()()317.38988.30140.002990.7944 (se)83.3909 2.32630.000757.8402PIZZAAGE INCOME HS =−++()()1.680273.204762.662192.0859COLLEGE GRAD−−None of the dummy variable coefficients are significant, casting doubt on the relevance of education as an explanatory variable. Also, including the education dummies has had little impact on the remaining coefficient estimates. To confirm the lack of evidence supporting the inclusion of education, we need to use an F test to jointly test whether the coefficients of HS, COLLEGE and GRAD are all zero. The value of this statistic is()()()63563753944632.020*********R U U SSE SSE J F SSE N K −−===−The 5% critical value for (3, 34) degrees of freedom is F c = 3.05; the p -value is 0.13. Wecannot conclude that level of educational attainment influences pizza consumption. (c) To test this hypothesis we estimate a model where the dummy variable gender (FEMALE ) interacts with every other variable in the equation. The estimated equation, with standard errors in parentheses, isn ()()()()451.36059.36320.0036208.3393 (se)63.9450 1.91550.000796.5078PIZZA AGE INCOME FEMALE =−+−()()2.83370.00183.08710.0008AGE×FEMALE INCOME×FEMALE−Chapter 7, Exercise Solutions, Principles of Econometrics, 3e 157Exercise 7.10(c) (continued)(c)To test the hypothesis that the regression equations for males and females are identical, we test jointly whether the coefficients of FEMALE , AGE ×FEMALE , INCOME ×FEMALE are all zero. Note that individual t tests on each of these coefficients do not suggest gender is relevant. However, when we take all variables together, the F value for jointly testing their coefficients is()()()635636.7244466.5318.1344244466.534R U U SSE SSE J F SSE N K −−===−This value is greater than F c = 2.866 which is the 5% critical value for (3, 36) degrees offreedom. The p -value is 0.0000. Thus, we reject the null hypothesis that males and females have identical pizza expenditure equations. This result implies different equations should be used to model pizza expenditure for males, and that for females. It does not say how the equations differ. For example, all their coefficients could be different, or simply modelling different intercepts might be adequate.Chapter 7, Exercise Solutions, Principles of Econometrics, 3e 158EXERCISE 7.11(a) The estimated result, with standard errors in parentheses, isn ()()()()161.4654 2.97740.009070.00016(se)120.6634 3.35210.003670.0000867PIZZA AGE INCOME INCOME×AGE =−+−This is identical to the result reported in 7.4.(b) From the sample we obtain average age = 33.475 and average income = 42,925. Thus, the required marginal effect of income isn ()0.009070.0001633.4750.00371E PIZZA INCOME∂=−×=∂Using computer software, we find the standard error of this estimate to be 0.000927, and the t value for testing whether the marginal effect is significantly different from zero is t =0.003710.000927 4.00=. The corresponding p -value is 0.0003 leading us to conclude that the marginal income effect is statistically significant at a 1% level of significance.(c) A 95% interval estimate for the marginal income effect is given by0.00371 ± 2.0281 × 0.000927 = (0.00183, 0.00559)(d) The marginal effect of age for an individual of average income is given byn ()()E PIZZA AGE ∂∂= −2.9774 − 0.00016INCOME = −2.9774 − 0.00016 × 42,925 = −9.854 Using computer software, we find the standard error of this estimate to be 2.5616, and thet value for testing whether the marginal effect is significantly different from zero is 9.8542.5616 3.85t =−=−The p -value of the test is 0.0005, implying that the marginal age effect is significantlydifferent from zero at a 1% level of significance. (e) A 95% interval estimate for the marginal age effect is given by −9.854 ± 2.0281 × 2.5616 = (−15.05, −4.66)Chapter 7, Exercise Solutions, Principles of Econometrics, 3e 159Exercise 7.11 (continued)(f)Important pieces of information for Gutbusters are the responses of pizza consumption to age and income. It is helpful to know the demand for pizzas in young and old communities and in high and low income areas. A good starting point in an investigation of this kind is to evaluate the responses at average age and average income. Such an evaluation will indicate whether there are noticeable responses, and, if so, give some idea of their magnitudes. The two responses are estimated asn ()E PIZZA INCOME ∂∂ = 0.0037n ()()E PIZZA AGE ∂∂ = −9.85Both these estimates are significantly different from zero at a 1% level of significance. They suggest that increasing income will increase pizza consumption, but, as a community ages, its demand for pizza declines. Interval estimates give an indication of the reliability of the estimated responses. In this context, we estimate that the income response lies between 0.0018 and 0.0056, while the age response lies between −15.05 and −4.66.。

【金融基本无害】传统计量经济学研究的局限:MIT的计量教学大纲

【金融基本无害】传统计量经济学研究的局限:MIT的计量教学大纲作者:余颖丰以下内容来自于《基本无害的量化金融学》第九章现代计量经济学主要包括两块:一块是微观计量、一块是宏观计量。

宏观计量和金融学有点远,我们不做讨论[1]。

微观计量和金融学还是有非常多的契合点。

当我们谈到量化金融的时候,我们一再强调量化金融分为两大派系:一派是P-type,一派是Q-type,这两大派系的区别和联系,我们已在前文中阐述,故不在此处再多做讨论。

简而言之,P-type可以认为是十分靠近金融计量学。

一般认为金融计量学较靠近微观计量。

但是,读者需要知道微观计量目前一般也分为两块,一块是基于面板的微观计量,一块是基于时间序列的微观计量。

这有什么区别呢?举以下两个例子。

有不少科研人员从事个人微观金融研究,这类科研人员很容易获得大量个人或者家庭的金融资产信息,这些针对个体和家庭的数据信息的数量都非常庞大,动辄十万,甚至更多,但是这些数据可能是按年份收集,可能数据仅有3-5年,因此这类型的数据的特点是个体数量远大于其时间维度,此外一般这些科研实验还假设个体与个体之间没有相互影响[2]。

第二个例子是股票数据,以中国为例,沪深个股(包含创业板)共三千多家,这些个股几乎每天都有交易,除非特殊原因,而每日的股票信息,如果按秒计算,每天交易4小时,每个股一天就能至少产生3600×4个价格信息,如果股票上市十年,按每年250个交易日计算,则十年间,一个个股就可以至少产生14400×250×10个交易数据,此外金融股价数据都有很强的自相关性,具备时间序列的基本特性,个股和个股之间,个股和大盘指数之间都有很强的相关性。

由此可见,这类型数据的特点和第一个例子的数据特点差别非常大。

因此,当代微观计量也分为两个派系,一个是偏面板(即第一个例子所阐述的那种数据类型)的微观计量,一个是偏时间维度(即第二个例子所阐述的那种数据类型)的微观计量。

计量经济学辅导讲稿.doc

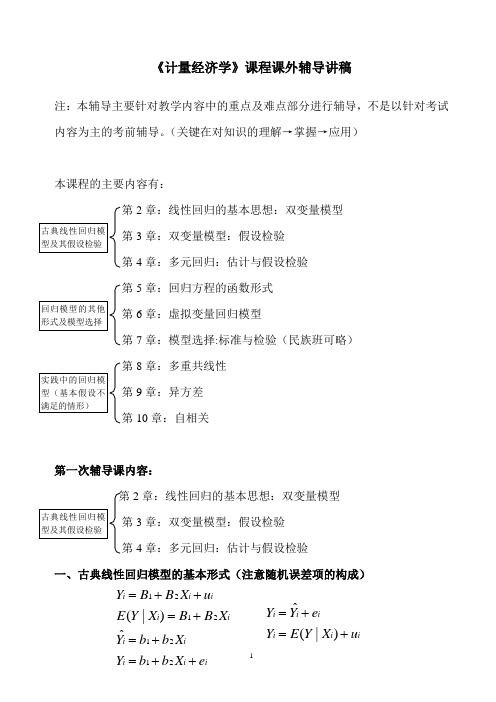

《计量经济学》课程课外辅导讲稿注:本辅导主要针对教学内容中的重点及难点部分进行辅导,不是以针对考试内容为主的考前辅导。

(关键在对知识的理解→掌握→应用)本课程的主要内容有:第2章:线性回归的基本思想:双变量模型第3章:双变量模型:假设检验 第4章:多元回归:估计与假设检验 第5章:回归方程的函数形式第6章:虚拟变量回归模型第7章:模型选择:标准与检验(民族班可略) 第8章:多重共线性第9章:异方差 第10章:自相关第一次辅导课内容:第2章:线性回归的基本思想:双变量模型第3章:双变量模型:假设检验 第4章:多元回归:估计与假设检验一、古典线性回归模型的基本形式(注意随机误差项的构成)i i i i ii i X b b YX B B X Y E u X B B Y +=+=++=212121ˆ)|(ii i i i i u X Y E Y e YY +=+=)|(ˆ二、古典线性回归模型的基本假定假定1 回归模型是参数线性的,并且是正确设定的。

假定 2 解释变量与随机扰动项u 不相关(解释变量是确定性变量时自然成立);假定3 零均值假定: E(u)=0 假定4 同方差假定: Var(u i )=常数 假定5 无自相关假定:Cov(u,u)=0 i ≠j假定6 假定随机项误差u 服从均值为零,(同)方差为常数的正态分布:),0(~2σN u i 假定7 解释变量之间不存在线性相关关系;注意:线性回归模型中线性的含义:一般的线性指的是解释变量线性和参数线性。

我们这里的线性强调的是参数线性。

三、古典线性回归模型的参数估计 1.参数估计的方法:普通最小二乘法(OLS)2.最小二乘原理:就是选择合适参数使得全部观察值的残差平方和(RSS)最小,数学形式为:()}min{ })ˆ(min{}min{2212∑∑∑--=-=i i i i 2iX b b Y Y Y e利用极值原理可得到正规方程组,求解可得:3.OLS 估计量的性质:高斯-马尔柯夫定理:若满足古典线性回归模型的基本假定,则在所有线性无偏估计量中,OLS 估计量具有最小方差性,即:OLS 估计量是最优线性无偏估计量(BLUE )。