Inflation Dynamics and Monetary Policy_yellen20150924

Part1MonetaryPolicy,Inflation,andtheBusinessCycle

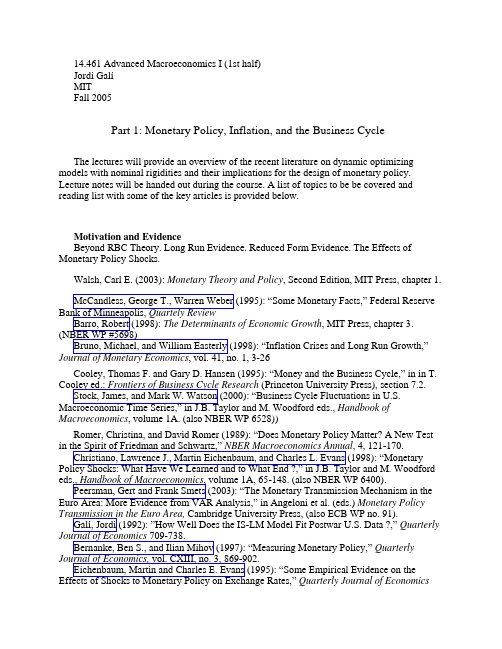

14.461Advanced Macroeconomics I(1st half)Jordi GalíMITFall2005Part1:Monetary Policy,Inflation,and the Business Cycle The lectures will provide an overview of the recent literature on dynamic optimizing models with nominal rigidities and their implications for the design of monetary policy. Lecture notes will be handed out during the course.A list of topics to be be covered and reading list with some of the key articles is provided below.Motivation and EvidenceBeyond RBC Theory.Long Run Evidence.Reduced Form Evidence.The Effects of Monetary Policy Shocks.Walsh,Carl E.(2003):Monetary Theory and Policy,Second Edition,MIT Press,chapter1.McCandless,George T.,Warren Weber(1995):“Some Monetary Facts,”Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis,Quartely ReviewBarro,Robert(1998):The Determinants of Economic Growth,MIT Press,chapter3. (NBER WP#5698)Bruno,Michael,and William Easterly(1998):“Inflation Crises and Long Run Growth,”Journal of Monetary Economics,vol.41,no.1,3-26Cooley,Thomas F.and Gary D.Hansen(1995):“Money and the Business Cycle,”in in T. Cooley ed.:Frontiers of Business Cycle Research(Princeton University Press),section7.2.Stock,James,and Mark W.Watson(2000):“Business Cycle Fluctuations in U.S. Macroeconomic Time Series,”in J.B.Taylor and M.Woodford eds.,Handbook of Macroeconomics,volume1A.(also NBER WP6528))Romer,Christina,and David Romer(1989):“Does Monetary Policy Matter?A New Test in the Spirit of Friedman and Schwartz,”NBER Macroeconomics Annual,4,121-170.Christiano,Lawrence J.,Martin Eichenbaum,and Charles L.Evans(1998):“Monetary Policy Shocks:What Have We Learned and to What End?,”in J.B.Taylor and M.Woodford eds.,Handbook of Macroeconomics,volume1A,65-148.(also NBER WP6400).Peersman,Gert and Frank Smets(2003):“The Monetary Transmission Mechanism in the Euro Area:More Evidence from VAR Analysis,”in Angeloni et al.(eds.)Monetary Policy Transmission in the Euro Area,Cambridge University Press,(also ECB WP no.91).Galí,Jordi(1992):”How Well Does the IS-LM Model Fit Postwar U.S.Data?,”Quarterly Journal of Economics709-738.Bernanke,Ben S.,and Ilian Mihov(1997):“Measuring Monetary Policy,”Quarterly Journal of Economics,vol.CXIII,no.3,869-902.Eichenbaum,Martin and Charles E.Evans(1995):“Some Empirical Evidence on the Effects of Shocks to Monetary Policy on Exchange Rates,”Quarterly Journal of Economics110,no.4,975-1010.Bils,Mark and Peter J.Klenow(2004):“Some Evidence on the Importance of Sticky Prices,”Journal of Political Economy,vol112(5),947-985.Dhyne,Emmanuel et al.(2005):“Price Setting in the Euro Area:Some Stylised Facts from Individual Consumer Price Data,”mimeo.Alvarez,Luis et al.(2005):“Sticky Prices in the Euro Area:Evidence from Micro-Data,”mimeo.A Simple Framework for Monetary Policy AnalysisHouseholds.Firms.Marginal costs and markups.Elements of equilibrium.Money demand. Capital accumulation.Walsh,Carl E.(2003):Monetary Theory and Policy,Second Edition,MIT Press,chapter2 (also related:chapter3)Woodford,Michael(2003):Interest and Prices:Foundations of a Theory of Monetary Policy,Princeton University Press,chapter1.Flexible PricesThe classical monetary model.Optimal price setting.Neutrality.Monetary policy rules and price level determination.Sources of non-neutrality.Optimal monetary policy. Hyperinflations.Walsh,Carl E.(2003):Monetary Theory and Policy,Second Edition,MIT Press,chapter2.Woodford,Michael(2003):Interest and Prices:Foundations of a Theory of Monetary Policy,Princeton University Press,chapter2.Cooley,Thomas F.and Gary D.Hansen(1995):“Money and the Business Cycle,”in in T. Cooley ed.:Frontiers of Business Cycle Research(Princeton University Press).Cooley,Thomas F.and Gary D.Hansen(1989):“Inflation Tax in a Real Business Cycle Model,”American Economic Review79,733-748.King,Robert G.,and Mark Watson(1996):“Money,Prices,Interest Rates,and the Business Cycle,”Review of Economics and Statistics,vol78,no1,35-53.Chari,V.V.,and Patrick J.Kehoe(1999):“Optimal Fiscal and Monetary Policy,”in in J.B. Taylor and M.Woodford eds.,Handbook of Macroeconomics,volume1C,1671-1745.Correia,Isabel,and Pedro Teles(1999):“The Optimal Inflation Tax,”Review of Economic Dynamics,vol.2,no.2325-346.A Baseline Sticky Price ModelThe Calvo model.The new Keynesian Phillips curve.The output gap and the natural rate of interest.The effects of monetary policy shocks.Evidence on inflation dynamics.Alternative time-dependent models:convex price adjustment costs,the Taylor model,the truncated Calvo model.State-dependent models.Walsh,Carl E.(2003):Monetary Theory and Policy,Second Edition,MIT Press,chapter5.Woodford,Michael(2003):Interest and Prices:Foundations of a Theory of MonetaryPolicy,Princeton University Press,chapter4.Calvo,Guillermo(1983):“Staggered Prices in a Utility Maximizing Framework,”Journal of Monetary Economics,12,383-398.Yun,Tack(1996):“Nominal Price Rigidity,Money Supply Endogeneity,and Business Cycles,”Journal of Monetary Economics37,345-370.King,Robert G.,and Alexander L.Wolman(1996):“Inflation Targeting in a St.Louis Model of the21st Century,”Federal Reserve Bank of St.Louis Review,vol.78,no.3.(NBER WP#5507).Fuhrer,Jeffrey C.and George R.Moore(1995):“Inflation Persistence”,Quarterly Journal of Economics,Vol.110,February,pp127-159.Galí,Jordi and Mark Gertler(1998):“Inflation Dynamics:A Structural Econometric Analysis,”Journal of Monetary Economics,vol44,no.2,195-222.Sbordone,Argia(2002):“Prices and Unit Labor Costs:A New Test of Price Stickiness,”Journal of Monetary Economics,vol.49,no.2,265-292.Galí,Jordi,Mark Gertler,David López-Salido(2001):“European Inflation Dynamics,”European Economic Review vol.45,no.7,1237-1270.Galí,Jordi,Mark Gertler,David López-Salido(2005):“Robustness of the Estimates of the Hybrid New Keynesian Phillips Curve,”Journal of Monetary Economics,forthcoming.Eichenbaum,Martin and Jonas D.M.Fisher(2004):“Evaluating the Calvo Model of Sticky Prices,”NBER WP10617.Mankiw,N.Gregory and Ricardo Reis(2002):“Sticky Information vs.Sticky Prices:A Proposal to Replace the New Keynesian Phillips Curve,”Quartely Journal of Economics,vol. CXVII,issue4,1295-1328.Rotemberg,Julio(1996):“Prices,Output,and Hours:An Empirical Analysis Based on a Sticky Price Model,”Journal of Monetary Economics37,505-533.Chari,V.V.,Patrick J.Kehoe,Ellen R.McGrattan(2000):“Sticky Price Models of the Business Cycle:Can the Contract Multiplier Solve the Persistence Problem?,”Econometrica, vol.68,no.5,1151-1180.Wolman,Alexander(1999):“Sticky Prices,Marginal Cost,and the Behavior of Inflation,”Economic Quarterly,vol85,no.4,29-48.Dotsey,Michael,Robert G.King,and Alexander L.Wolman(1999):“State Dependent Pricing and the General Equilibrium Dynamics of Money and Output,”Quarterly Journal of Economics,vol.CXIV,issue2,655-690.Dotsey,Michael,and Robert G.King(2005):“Implications of State Dependent Pricing for Dynamic Macroeconomic Models,”Journal of Monetary Economics,52,213-242.Golosov,Mikhail,Robert E.Lucas(2005):“Menu Costs and Phillips Curves”mimeo.Gertler,Mark and John Leahy(2005):“A Phillips Curve with an Ss Foundation,”mimeo.Monetary Policy Design in the Baseline ModelA benchmark case.Optimal monetary policy and its implementation.The Taylor Principle. Simple Monetary Policy Rules.Second order approximation to welfare losses.Evidence on Monetary Policy rules.The effects of technology shocks:theory and evidence.Galí,Jordi(2003):“New Perspectives on Monetary Policy,Inflation,and the BusinessCycle,”in Advances in Economics and Econometrics,volume III,edited by M.Dewatripont, L.Hansen,and S.Turnovsky,Cambridge University Press(also available as NBER WP#8767).Woodford,Michael(2003):Interest and Prices:Foundations of a Theory of Monetary Policy,Princeton University Press,chapter6.Yun,Tack(2005):“Optimal Monetary Policy with Relative Price Distortions”American Economic Review,vol.95,no.1,89-109Blanchard,Olivier and Charles Kahn(1980),“The Solution of Linear Difference Models under Rational Expectations”,Econometrica,48,1305-1311Bullard,James,and Kaushik Mitra(2002):“Learning About Monetary Policy Rules,”Journal of Monetary Economics,vol.49,no.6,1105-1130.Woodford,Michael(2001):“The Taylor Rule and Optimal Monetary Policy,”American Economic Review91(2):232-237(2001).Rotemberg,Julio and Michael Woodford(1999):“Interest Rate Rules in an Estimated Sticky Price Model,”in J.B.Taylor ed.,Monetary Policy Rules,University of Chicago Press.Benhabib,Jess,Stephanie Schmitt-Grohe,and Martin Uribe(2001):“The Perils of Taylor Rules,”Journal of Economic Theory96,40-69.Levin,Andrew,Volker Wieland,and John C.Williams(2003):“The Performance of Forecast-Based Monetary Policy Rules under Model Uncertainty,”American Economic Review,vol.93,no.3,622-645.Clarida,Richard,Jordi Galí,and Mark Gertler(2000):“Monetary Policy Rules and Macroeconomic Stability:Evidence and Some Theory,”Quarterly Journal of Economics,vol. 115,issue1,147-180.Taylor,John B.(1998):“An Historical Analysis of Monetary Policy Rules,”in J.B.Taylor ed.,Monetary Policy Rules,University of Chicago Press.Orphanides,Athanasios(2003):“The Quest for Prosperity Without Inflation,”Journal of Monetary Economics50,633-663Galí,Jordi(1999):“Technology,Employment,and the Business Cycle:Do Technology Shocks Explain Aggregate Fluctuations?,”American Economic Review,vol.89,no.1,249-271.Basu,Susanto,John Fernald,and Miles Kimball(2004):“Are Technology Improvements Contractionary?,”American Economic Review,forthcoming(also NBER WP#10592).Francis,Neville,and Valerie Ramey(2005):“Is the Technology-Driven Real Business Cycle Hypothesis Dead?Shocks and Aggregate FLuctuations Revisited,”Journal of Monetary Economics,forthcoming.Galí,Jordi and Pau Rabanal(2004):“Technology Shocks and Aggregate Fluctuations: How Well Does the RBC Model Fit Postwar U.S.Data?,”NBER Macroeconomics Annual 2004,225-288.(also as NBER WP#10636).Christiano,Lawrence,Martin Eichenbaum,and Robert Vigfusson(2003):“What happens after a Technology Shock?,”NBER WP#9819.Galí,Jordi,J.David López-Salido,and Javier Vallés(2003):“Technology Shocks and Monetary Policy:Assessing the Fed’s Performance,”Journal of Monetary Economics,vol.50, no.4.,723-743.Extensions of the Baseline Model and their Implications for Monetary PolicyCost-push shocks.Nominal wage rigidities.Monetary frictions.Inflation inertia.Real wage rigidities.Steady state distortions.Estimated medium-scale models.Giannoni,Marc P.,and Michael Woodford(2003):“Optimal Inflation Targeting Rules,”in B.Bernanke and M.Woodford,eds.The Inflation Targeting Debate,Chicago,Chicago University Press.(also NBER WP#9939).Woodford,Michael(2003):Interest and Prices:Foundations of a Theory of Monetary Policy,Princeton University Press,chapters6-8.Clarida,Richard,Jordi Galí,and Mark Gertler(1999):“The Science of Monetary Policy:A New Keynesian Perspective,”Journal of Economic Literature,vol.37,no.4,1661-1707.Erceg,Christopher J.,Dale W.Henderson,and Andrew T.Levin(2000):“Optimal Monetary Policy with Staggered Wage and Price Contracts,”Journal of Monetary Economics vol.46,no.2,281-314.Huang,Kevin X.D.,and Zheng Liu.(2002):“Staggered Price-setting,staggeredwage-setting and business cycle persistence,”Journal of Monetary Economics,vo.49,405-433.Woodford,Michael(2003):“Optimal Interest Rate Smoothing,”Review of Economic Studies,vol.70,no.4,861-886.Steinsson,Jón(2003):“Optimal Monetary Policy in an Economy with Inflation Persistence,”Journal of Monetary Economics,vol.50,no.7.Blanchard,Olivier J.and Jordi Galí(2005):“Real Wage Rigidities and the Nw Keynesian Model”mimeo.Benigno,Pierpaolo,and Michael Woodford(2005):“Inflation Stabilization and Welfare: the Case of a Distorted Steady State”Journal of the European Economic Association, forthcoming.Khan,Aubhik,Robert G.King and Alexander L.Wolman(2003):“Optimal Monetary Policy,”Review of Economic Studies,825-860.Christiano,Lawrence J.,Martin Eichenbaum,and Charles L.Evans(2001):“Nominal Rigidities and the Dynamic Effects of a Shock to Monetary Policy,”Journal of Political EconomySmets,Frank,and Raf Wouters(2003):“An Estimated Dynamic Stochastic General Equilibrium Model of the Euro Area,”Journal of the European Economic Association,vol1, no.5,1123-1175.Monetary Policy in the Open EconomyEmpirical issues.Two country models.Small Open Economy.Monetary Unions.Local Currency Pricing.Benigno,Gianluca,and Benigno,Pierpaolo(2003):“Price Stability in Open Economies,”Review of Economic Studies,vol.70,no.4,743-764.Galí,Jordi,and Tommaso Monacelli(2005):“Monetary Policy and Exchange Rate Volatility in a Small Open Economy,”Review of Economic Studies,vol.72,issue3,2005,707-734.Clarida,Richard,Jordi Galí,and Mark Gertler(2002):“A Simple Framework for International Monetary Policy Analysis,”Journal of Monetary Economics,vol.49,no.5, 879-904.Benigno,Pierpaolo(2004):“Optimal Monetary Policy in a Currency Area,”Journal of International Economics,vol.63,issue2,293-320.Monetary and Fiscal Policy InteractionsFiscal policy rules and equilibrium determination.Distortionary taxes and optimal policy. Non-Ricardian economies and the effects ernment spending.Optimal monetary and fiscal policy in currency unions.Leeper,Eric(1991):“Equilibria under Active and Passive Monetary Policies,”Journal of Monetary Economic s27,129-147.Sims,Christopher A.(1994):“A Simple Model for the Determination of the Price Level and the Interaction of Monetary and Fiscal Policy,”Economic Theory,vol.4,381-399.Woodford,Michael(1996):“Control of the Public Debt:A Requirement for Price Stability,”NBER WP#5684.Davig,Troy and Eric Leeper(2005):“Fluctuating Macro Policies and the Fiscal Theory,”mimeo.Schmitt-Grohé,Stephanie,and Martin Uribe(2004):“Optimal Fiscal and Monetary Policy under Sticky Prices,”Journal of Economic Theory114,198-230Schmitt-Grohé,Stephanie,and Martin Uribe(2003):“Optimal Simple and Implementable Monetary and Fiscal Rules,”NBER WP#10253.Blanchard,Olivier and Roberto Perotti(2002),“An Empirical Characterization of the Dynamic Effects of Changes in Government Spending and Taxes on Output,”Quarterly Journal of Economics,vol CXVII,issue4,1329-1368.Fatás,Antonio and Ilian Mihov(2001),“The Effects of Fiscal Policy on Consumption and Employment:Theory and Evidence,”INSEAD,mimeo.Galí,Jordi,J.David López-Salido and Javier Vallés(2005):“Understanding the Effects of Government Spending on Consumption,”mimeo.Galí,Jordi,and Tommaso Monacelli(2005):“Optimal Monetary and Fiscal Policy in a Currency Union:A New Keynesian Perspective,”miemo.。

曼昆-十大经济学原理,中英文对照

十大经济学原理。

曼昆在《经济学原理》一书中提出了十大经济学原理,他们分别是:十大经济学原理一:人们面临权衡取舍。

人们为了获得一件东西,必须放弃另一件东西。

决策需要对目标进行比较。

People Face Trade offs. To get one thing, you have to give up something else. Making decisions requires trading off one goal against another.例子:这样的例子很多,典型的是在“大炮与黄油”之间的选择,军事上所占的资源越多,可供民用消费和投资的资源就会越少。

同样,政府用于生产公共品的资源越多,剩下的用于生产私人品的资源就越少;我们用来消费的食品越多,则用来消费的衣服就越少;学生用于学习的时间越多,那么用于休息的时间就越少。

十大经济学原理二:某种东西的成本是为了得到它所放弃的东西。

决策者必须要考虑其行为的显性成本和隐性成本。

The Cost of Something is what You Give Up to Get It. Decision-makers have to consider both the obvious and implicit costs of their actions.例子:某公司决定在一个公园附近开采金矿的成本。

开采者称由于公园的门票收入几乎不受影响,因此金矿开采的成本很低。

但可以发现伴随着金矿开采带来的噪声、水和空气的污染、环境的恶化等,是否真的不会影响公园的风景价值?尽管货币价值成本可能会很小,但是考虑到环境和自然生态价值会丧失,因此机会成本事实上可能很大。

十大经济学原理三:理性人考虑边际量。

理性的决策者当且仅当行动的边际收益超过边际成本时才采取行动。

Rational People Think at Margin. A rational decision-maker takes action if and only ifthe marginal benefit of the action exceeds the marginal cost.例子:“边际量”是指某个经济变量在一定的影响因素下发生的变动量。

宏观调控英语术语

宏观调控英语术语

宏观调控英语术语是指应用于宏观经济领域的一些专业术语,主要用于描述国家或政府在宏观经济领域进行的调控活动。

以下是一些常见的宏观调控英语术语:

1. Fiscal Policy:财政政策

2. Monetary Policy:货币政策

3. Interest Rate:利率

4. Inflation:通货膨胀

5. Deflation:通货紧缩

6. Recession:经济衰退

7. Stabilization Policy:稳定政策

8. Aggregate Demand:总需求

9. Aggregate Supply:总供给

10. Gross Domestic Product (GDP):国内生产总值

11. Unemployment Rate:失业率

12. Exchange Rate:汇率

13. Balance of Payments:国际收支

14. Structural Adjustment:结构调整

15. Public Debt:公共债务

16. Money Supply:货币供应量

这些术语在宏观经济领域中被广泛使用,有助于描述和分析国家或政府在经济调控方面所采取的政策和措施。

了解这些术语可以帮助

我们更好地理解经济现象和政策。

通货膨胀动态和通胀预期外文文献翻译2019-2020

通货膨胀动态和通胀预期外文翻译2019-2020英文Global inflation dynamics and inflation expectationsMartin Feldkirchera, Pierre SiklosAbstractIn this paper we investigate dynamics of inflation and short-run inflation expectations. We estimate a global vector autoregressive (GV AR) model using Bayesian techniques. We then explore the effects of three source of inflationary pressure that could drive up inflation expectations: domestic aggregate demand and supply shocks as well as a global increase in oil price inflation. Our results indicate that inflation expectations tend to increase as inflation accelerates. However, the effects of the demand and supply shocks are short-lived for most countries. When global oil price inflation accelerates, however, effects on inflation and expectations are often more pronounced and long-lasting. Hence, an assessment of the link between observed inflation and inflation expectations requires disentangling the underlying sources of inflationary pressure. We also examine whether the relationship between actual inflation and inflation expectations changed following the global financial crisis. The transmission between inflation and inflation expectations is found to be largely unaffected in response to domestic demand and supply shocks, while effects of an oil price shock on inflationexpectations are smaller post-crisis.Keywords: Inflation, Inflation expectations, GV AR modelling, Anchoring of inflation expectationsIntroductionInflation expectations are a pivotal variable in providing insights about likely future economic conditions. While the decades long debate about the degree to which monetary policy is forward looking has not abated (e.g., Friedman, 1968; Woodford, 2003a) there is little doubt that policy makers devote considerable attention to the economic outlook. Hence, the dynamics of the relationship between inflation and inflation expectations continues to pre-occupy the monetary authorities and central bankers. Even before the full impact of the global financial crisis (GFC) of 2008–9 was felt in the US, and in many other parts of the globe, central bankers such as Bernanke (2007) highlighted the importance of inflation expectations since “… the state of inflation expectations greatly influences actual inflation …“. More recently, Yellen (2016) also underscores the crucial role played by expectations while bemoaning the fact that the profession must confront gaps in our knowledge about the relationship between observed inflation and the short-run inflation expectations that lies at the heart of many theoretical macroeconomic models. It is not difficult to come across speeches by central bankers who, on a regular basis, touch upon the subject of the formation andimplications of inflation expectations.A main, but not sole, driver of inflation expectations is past inflation. At the risk of some over-simplification, inflation can be thought of as being driven by two sets of determinants, namely local or domestic factors versus international or global forces. The local determinants would include technical progress and changes in productivity, demographic factors, institutional considerations such as the adoption of inflation targeting and central bank independence and, since 2008, the adoption and maintenance of unconventional monetary policies in systemically important economies. More generally, however, economists tend to make the distinction between aggregate demand and supply sources of changes in inflation pressure. In what follows, we retain this distinction to allow for greater comparability with the extant literature as well as because it provides us with a vehicle to present new insights into the underlying drivers of inflation and ultimately about the likelihood that inflation expectations can be anchored.Globalization in both the trading of good and services and in finance is often also touted as a critical driver of the international component that influences domestic inflation rates. As a result, the extant literature has diverged wherein some argue that models of inflation are too nation centric (e.g., Borio & Filardo, 2007; Ahmad & Civelli, 2016; Auer, Borio, & Filardo, 2017, Kabukçuoğlu & Martínez-García, 2018) while othersplace greater emphasis on the various local factors mentioned above.The current literature generally focuses on a homogeneous set of countries (e.g., advanced or emerging market economies; see the following section). We depart from this norm to consider 42 economies that span a wide range in terms of their size, success at controlling inflation, monetary strategies in place, and the extent to which they were directly implicated or not in the GFC. To fully exploit the potential for cross-border spillovers in inflation we use the Global V ARs (GV AR) methodology (Pesaran & Chudik, 2016). This methodology is well suited to address the domestic impact of changing inflation on expectations dynamics controlling for international spillovers through cross-border inter-linkages.Often, global factors are constructed using some indicator of trade openness to aggregate country-specific series. Nevertheless, there is disagreement about whether this is the appropriate vehicle to estimate global versus local influences on domestic inflation (e.g., Kabukçuoğlu & Martínez-García, 2018; Ahmad & Civelli, 2016). Instead, we propose a novel set of weights in estimating the GV AR obtained from the forecast error variance decompositions estimated via the methodology of Diebold and Yilmaz (DY, 2009) developed to measure the degree of connectedness. Since the debate about local versus global determinants of inflation expectations partly centers around the extent to which countriesare linked to each other the DY technique is a natural one to use in the present circumstances. Indeed, the foregoing combination of methodologies permits us to highlight two neglected aspects of the debate about what drives inflation and inflation expectations. First, that the relative importance of local versus global factors is likely a function of the policy horizon. Second, the globalization of observed inflation is also reflected in a globalization of expected inflation. While the GV AR methodology provides a very rich set of potential shocks that may be analyzed, we focus on two sets of shocks. They are: the impact of domestic aggregate demand and supply shocks on inflation and inflation expectations and the impact of a global oil price supply shock on these same two variables.Briefly, we find that inflation expectations respond positively to either domestic aggregate demand or supply shocks, but the effects are generally temporary. This finding holds equally true for the post-crisis period. By contrast, if inflation accelerates due to a pick-up in global oil price inflation, inflation expectations respond significantly positive and effects are long lasting. The impact on inflation is even larger than on inflation expectations. Hence, oil price shocks drive a wedge between inflation and inflation expectations even among professional forecasters. Nevertheless, actual inflation and inflation expectations tend to co-move closely and the pass-through has diminished in the aftermath of the crisis.Therefore, in an era where energy prices are volatile and are subject to large swings, this has implications for when and how aggressively monetary authorities ought to respond to oil price shocks. An additional important implication is that identifying the aggregate supply from aggregate demand components of shocks is critical to understanding the dynamics of both observed and expected inflation.Literature reviewInflation expectations lie at the core of all macroeconomic models (e.g., Woodford, 2003a). Moreover, to the extent that policy is able to influence these expectations, understanding the connection with observed inflation remains an essential ingredient to evaluating the impact of monetary policy.Especially following the GFC, the debate surrounding the mechanism that best describes how expectations adjust in response to shocks, as well as what are the fundamental drivers of inflation expectations, has been rekindled. The same is true of the companion literature that explores the dynamics and determinants of observed inflation. An era of ultra-low interest rates, combined with low inflation, has also contributed to reviving the study and debate about links between inflation and inflation expectations.Rational expectations serve as a convenient benchmark, in part because theoretical models are readily solvable and closed form solutionsare typically feasible. However, when confronted with the empirical evidence, considerable differences of opinion emerge about how best to describe the evolution of expectations. For example, an early assessment by the Bank of Japan of its Quantitative and Qualitative Easing program (QQE; Bank of Japan, 2016) finds that the Japanese are prone to adjusting inflation expectations more gradually than in other advanced economies (e.g., the US or the euro area). This is largely due to the backward-looking nature of these expectations. This also resonates somewhat with recent evidence from the US (e.g., Trehan, 2015) and other economies both large and systemically important as well as ones that are small and open (e.g., Bhatnagar et al., 2017).Of course, there may be several explanations for the sluggish adjustment of inflation expectations. Japan, after two decades or more of very low inflation to low deflation, sets this country apart from the remaining advanced economies which, over the same period, experienced only passing bouts of deflation (early 2000s and in the aftermath of the 2007-8 global financial crisis). Since that time, below ‘normal’ inflation rates have spread across much of the advanced world. Unsurprisingly, this has attracted the attention and the concern of policy makers. This represents a relatively new element in the story of the dynamics of inflation.6It is also notable that, prior to the recent drop in inflation, the main concern was the role of commodity prices, notably oil prices, ingenerating higher inflation and the extent to which these shocks were seen to have permanent effects or not.Even if domestic economic slack retains its power to influence inflation, the globalization of trade and finance has introduced a new element into the inflation story, namely the potential role of global slack. Rogoff (2003, 2006) early on drew attention to the link between the phenomenon of globalization and inflation. Alternatively, at almost the high point of the globalization era, studies began to appear that provided empirical support either in favor of a significant global component in inflation, in some of its critical components (e.g., Ciccarelli & Mojon, 2010; Parker, 2017), or via the global influence of China's rapid economic growth (e.g., Pang & Siklos, 2016, and references therein).Economists, central bankers and policy makers have waxed and waned in their views about the significance of global slack as a source of inflationary pressure. Nevertheless, it is a consideration that needs to be taken seriously and the question remains understudied (e.g., see Borio & Filardo, 2007, Ihrig, Kamin, Lindner, & Marquez, 2010 and Yellen, 2016). More broadly, the notion that a global component is an important driver of domestic inflation rates continues to find empirical support despite of the proliferation of new econometric techniques used to address the question (e.g., Carriero, Corsello, & Marcellino, 2018).Recalling the words of central bankers cited in the introduction thereremains much to be learned about the dynamic relationship between observed and expected inflation. The two are inextricably linked, for example, in theory because the anchoring of expectations is thought to be the core requirement of a successful monetary policy strategy that prevents prices (and wages) from drifting away either from a stated objective, as in inflation targeting economies, or an implicit one where the central bank is committed to some form of price stability.There is, of course, also an ever-expanding literature that examines how well expectations are anchored. This literature focuses mostly on long-run inflation expectations (e.g., see Buono & Formai, 2018; Chan, Clark, & Koop, 2017; Mehrotra & Yetman, 2018; Lyziak & Paloviita, 2016; Strohsal & Winkelmann, 2015, and references therein). A few authors have focused on episodes when inflation is below target (e.g., Ehrmann, 2015), or during mild deflations (Banerjee & Mehrotra, 2018), while IMF (2016), Blanchard (2016), and Blanchard, Cerutti, and Summers (2015), are more general investigations of the issues.While central bankers and a considerable portion of existing empirical research worries about how changes to inflation expectations influence observed inflation the more recent literature on the anchoring of expectations shifts the emphasis on how inflation shocks can de-anchor these same expectations. Unfortunately, there is as yet no formal definition of ‘anchoring’. Indeed, there is still nothing approaching aconsensus on the determinants of inflation expectations from various sources (e.g., households, firms, professionals). Factors range from the past history of inflation, knowledge of monetary policy, media portrayals of the inflation process, shopping experience, and the impact of commodity prices, to name some of the most prominent determinants (e.g., see Coibion, Gorodnichenko, Kumar, & Pedemonte, 2018b). Not listed is a role for global factors which is a focus of the present study. Since, as we shall see below, there is a close connection between inflation and expected inflation, and an increasingly well-established link between global and local inflation, there exists an additional unexplored avenue that ties inflation performance on a global scale to local inflation expectations. We contribute to this literature in the sense that we also quantify the effects of inflationary shocks on short-run inflation expectations, which has a bearing on the ability of central banks to anchor inflation in the medium-term.Ad hoc methods exist to convert fixed event into fixed horizon forecasts (e.g., see Buono & Formai, 2018; Siklos, 2013). Winkelried (2017) adapts the Kozicki and Tinsley (2012) shifting endpoint model to exploit the information content of fixed event forecasts. Of course, we do not know whether or how much new information is absorbed into subsequent forecasts in an environment where the horizon shrinks whether it is because information is sticky or there is sufficient rationalinattention that mitigates the effective differences between fixed horizon and fixed event forecasts. Although constructed fixed horizon forecasts are imperfect (e.g., Yetman, 2018) they have the advantage that several papers in the extant literature employ this proxy.Until the recent period of sluggish inflation, the focus of much research fell on accounts that sought to evaluate the success, or lack thereof, of inflation targeting (IT) regimes. The fact that this kind of monetary policy strategy was designed in an era where the challenge was to reduce inflation is not lost on those who ask whether IT regimes are up to the task of maintaining inflation close to the target (e.g., see Ehrmann, 2015 and references therein).Fuhrer (2017) considers the extent to which expectations of inflation are informative about the dynamics of observed inflation based on empirical work that covers a period of 25 years for the US and Japan. Fuhrer's study is also interested in the extent to which long-term inflation objectives can be modelled via a sequence of short-term forecasts. The answer seems to be in the affirmative but significant departures from the long-term are present in the data. In contrast, our study is not able to determine the strength of any such links due to data limitations, as we shall see. Nevertheless, as suggested above, the degree to which inflation is anchored need not be solely evaluated according to long-term expectations. Short-term deviations can also serve as warning signals.To our knowledge then, a dynamic model that attempts to evaluate the link between inflation and inflation expectations in economies beyond ones that are advanced, and the role of global factors as well as cross-country interactions, is still missing. The following sections begin to fill the gap.Empirical resultsWe begin by investigating the responses of inflation expectations and actual inflation to a domestic AD shock. We see that for most economies the response of inflation expectations is either flat and hovers around zero or is hump shaped, petering out in the longer term. This finding implies a high degree of anchoring of short-term inflation expectations, which might directly translate into anchoring of long-run inflation expectations. Countries for which inflation expectations converge more slowly comprise advanced and euro area economies (Italy, Ireland, Norway, Portugal and Slovenia), CESEE economies (Bulgaria, Croatia, Russia), Asian economies (China, India and Indonesia) as well as South Africa. In Italy, Norway, South Africa and Slovenia the cooling off phase of inflation expectations takes particularly long. Inflation expectations decrease in India, Indonesia and Chile.Do inflation expectations and actual inflation always move in the same direction? We see that actual inflation responses are not hump shaped – rather in most countries actual inflation gradually declines anddies out after 8–16 months. However, in countries that show a longer adjustment phase, actual inflation responses also take longer to cool off. In countries with negative inflation expectation responses actual inflation tends to be negative over the impulse response horizon such as in the cases of India and Chile. In Indonesia, by contrast, actual inflation is positive up until 20 months revealing a negative relationship between inflation expectations and inflation, which, however, is not statistically significant since credible intervals of both responses overlap. A significantly larger long-run effect of inflation compared to inflation expectations can be found in Peru, though.Next, we investigate the impact of domestic AS shocks on inflation expectations. Here, we also find that inflation expectations tend to adjust rather quickly for almost all countries. Shapes of actual inflation responses tend to differ from those for inflation expectations indicating that there is no direct one-to-one relationship between the two series. Exceptions to this result are obtained in countries that either show a positive and significant response of inflation expectations in the long-run (Bulgaria and Croatia) or a negative response (India, Brazil and Chile). In these countries, inflation expectations tend to follow closely actual inflation responses implying that there is no divergence between responses of inflation expectations and actual inflation. Only in two countries are differences in long-run responses of inflation expectationsand inflation statistically significant. More specifically, in Chile, responses of inflation expectations are significantly more pronounced than responses of actual inflation, whereas the opposite is the case in Peru.Finally, we look at the effects of a supply side driven acceleration of oil price inflation. Here, we see that most of the effects are positive and long-lasting. Also, the effects are sometimes rather sizable even in the long-run. The bottom panel shows differences in inflation expectations and inflation responses along with 68% credible intervals. The figure indicates that even after 25 months, effects on actual inflation are sizable and for some countries significantly larger than those on inflation expectations. Regressing the posterior median of these differences on the sum of exports and imports in % of GDP, averaged over the sample period, shows that countries with a higher degree of trade openness show larger differences in responses. The implication is that for more open economies the effect of oil price changes on domestic inflation is larger, thereby driving a wedge between expectations and actual inflation. That the effect of global shocks on domestic inflation is larger for more open economies is consistent with the findings provided in Ahmad and Civelli (2016). Having said that, responses of inflation expectations in absolute terms also tend to be sizeable. Indeed, in 23 of 42 countries, long run-effects on inflation expectations are above 0.4. This implies thatnearly half of the acceleration in oil prices directly translates into upward movements of inflation expectations. In contrast to the domestic demand and supply shocks, there are no significantly negative responses for the countries covered in this study. Finally, comparing the shapes of impulse responses, we find a strong relationship between actual inflation and inflation expectation responses.Summing up, inflation expectations increase in the short-run if inflationary pressure stems from either domestic supply or demand shocks. However, no permanent effects are found. This result changes when a global acceleration of oil price inflation is considered. Here, we find positive long-run effects on inflation expectations for a range of countries. Also, there is a close link between actual inflation and inflation expectations indicating that there is a direct pass-through, to a different extent, from oil prices to domestic inflation to inflation expectations.ConclusionsIn this paper we investigate the dynamics of global inflation and short-run inflation expectations. We first demonstrate the existence of substantial interdependence between global and domestic inflation and inflation expectations. This implies that inflation expectations are not only driven by changes in domestic macroeconomic conditions but also by inflation expectations of other countries. The same holds true for observed inflation.We then proceed to investigate the drivers of inflation expectations controlling for global linkages in the data. We rely on a global vector autoregressive (GV AR) model estimated using Bayesian shrinkage priors. Our model nests a broad range of specifications for inflation and inflation expectations including variables that measure global slack. We then identify three shocks that can lead to inflationary pressure, namely a domestic aggregate demand shock, a domestic aggregate supply shock and a global acceleration of oil price inflation. The shocks are identified using sign restrictions and the oil supply shock makes use of the cross-sectional dimension of the data (Cashin et al., 2014, Mohaddes and Pesaran, 2016).Our main findings are as follows: First, we find that inflation expectations respond positively to domestic shocks that drive up actual inflation. This is true for aggregate demand shocks that drive up both actual inflation and output as well as for aggregate supply shocks which are characterized by an acceleration of inflation but a contraction in output. Peak effects of inflation expectations tend to be positive, but overall effects are rather short-lived. The most direct pass-through from actual inflation to inflation expectations, however, is observed when inflation increases due to a global acceleration of (supply-driven) oil price inflation. Here, both actual inflation and inflation expectations respond positively and effects are sizeable. This implies that for a policy makerinterested in the anchoring of long-run inflation expectations, oil price shocks should be closely watched since the high pass-through to short-run inflation expectations can limit the room for long-run inflation expectation anchoring. This is not the case for domestic demand and supply shocks that only show short-lived effects on short-run inflation expectations.Second, we examine whether the pass-through of inflation to short-run inflation expectations has changed during the aftermath of the global financial crisis – a period that was characterized by low inflation in advanced economies and the introduction of unconventional monetary policies by several major central banks to stimulate inflation. We find that the transmission between inflation and inflation expectations was largely unaffected in response to domestic demand and supply shocks. For the oil supply shock, our findings indicate a smaller impact on inflation expectations post-crisis. This implies a greater likelihood of a successful anchoring of long-run inflation expectations in the aftermath of the crisis compared to the full sample period. Lastly, we examine more generally the drivers of inflation expectations. Here we find that domestic inflation expectations, oil prices and variables from large emerging economies such as India and Turkey are important drivers of inflation expectations. For some CESEE economies, Russian macroeconomic conditions also shape inflation expectations.Some (e.g., Coibion, Gorodnichenko, Kumar, et al., 2018b) have drawn attention to differences between household and the professional forecasts used in the present study as critical to determining whether expectations are anchored. Clearly, this is a potential area where additional work is necessary. However, unlike household expectations, whose availability is episodic and where the manner in which surveys are structured and information about inflation expectations are solicited, our data set consists of comparable data and is on a global scale. Moreover, paralleling some of the results based on household surveys, professional forecasts are potentially just as sensitive to energy prices movements. Policy makers will have to bear this in mind when associating a tightening or loosening of monetary policy to changes in oil prices.中文全球通货膨胀动态和通胀预期马丁费德基拉摘要在本文中,我们研究了通胀和短期通胀预期的动态。

fomc货币政策会议声明全文(中英文对照)

fomc货币政策会议声明全文(中英文对照)美联储货币政策会议声明全文(中英文对照)中文版:美联储联邦公开市场委员会于XXX年XX月XX日召开货币政策会议。

会议讨论了当前经济状况和未来货币政策调整的问题。

根据对经济数据的评估和展望,委员会决定采取以下措施:1. 将联邦基金利率目标范围维持在XX%至XX%不变。

这一利率水平有助于支持经济增长和就业市场的稳定。

2. 将继续购买国债和抵押贷款支持证券,以维持适当的货币流动性。

购买规模和节奏将根据市场情况进行调整。

3. 继续监控经济增长、通胀和就业市场的变化,并根据数据来调整货币政策。

委员会将密切关注通胀预期和金融市场的波动。

4. 将通过透明的沟通方式向公众传达货币政策决策的思路和依据。

委员会鼓励公众对货币政策进行积极的参与和理解。

委员会认为,当前美国经济正在逐步复苏,但仍面临不确定性和风险。

委员会将继续采取适当的措施来支持和促进经济增长,同时保持通胀和金融市场稳定。

英文版:The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) of the Federal Reserve met on XX Month XX, XXXX to discuss the current economic conditions and future adjustments to monetary policy. Based on the assessment of economic data and outlook, the Committee decided to take the following measures:1. Maintain the target range for the federal funds rate at XX% to XX%. This level of interest rates is expected to support economic growth and stabilize the job market.2. Continue to purchase Treasury securities and mortgage-backed securities to maintain appropriate monetary liquidity. The scale and pace of purchases will be adjusted based on market conditions.3. Monitor changes in economic growth, inflation, and the job market, and adjust monetary policy accordingly. The Committee will closely watch inflation expectations and financial market volatility.4. Communicate the rationale and basis for monetary policy decisions in a transparent manner to the public. The Committee encourages active public participation and understanding of monetary policy.The Committee believes that the current U.S. economy is gradually recovering but still faces uncertainty and risks. The Committee will continue to take appropriate measures to support and promote economic growth while maintaining inflation and financial market stability.。

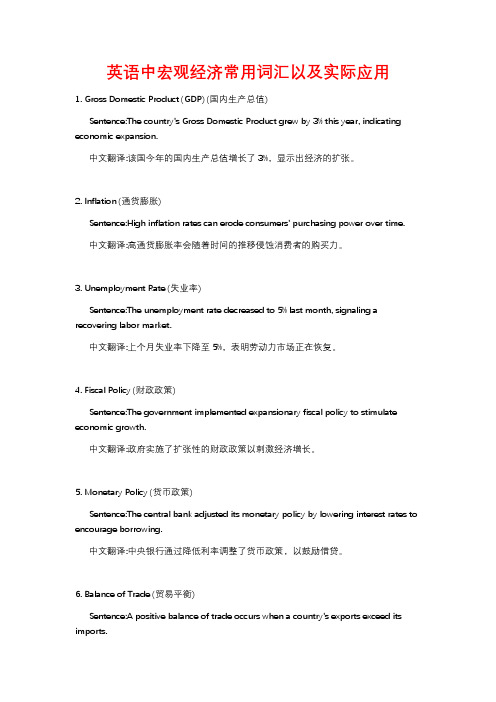

英语中宏观经济常用词汇以及实际应用

英语中宏观经济常用词汇以及实际应用1. Gross Domestic Product (GDP) (国内生产总值)Sentence:The country's Gross Domestic Product grew by 3% this year, indicating economic expansion.中文翻译:该国今年的国内生产总值增长了3%,显示出经济的扩张。

2. Inflation (通货膨胀)Sentence:High inflation rates can erode consumers' purchasing power over time.中文翻译:高通货膨胀率会随着时间的推移侵蚀消费者的购买力。

3. Unemployment Rate (失业率)Sentence:The unemployment rate decreased to 5% last month, signaling a recovering labor market.中文翻译:上个月失业率下降至5%,表明劳动力市场正在恢复。

4. Fiscal Policy (财政政策)Sentence:The government implemented expansionary fiscal policy to stimulate economic growth.中文翻译:政府实施了扩张性的财政政策以刺激经济增长。

5. Monetary Policy (货币政策)Sentence:The central bank adjusted its monetary policy by lowering interest rates to encourage borrowing.中文翻译:中央银行通过降低利率调整了货币政策,以鼓励借贷。

6. Balance of Trade (贸易平衡)Sentence:A positive balance of trade occurs when a country's exports exceed its imports.中文翻译:当一个国家的出口超过进口时,就会出现贸易平衡顺差。

宏观背景概述英语作文

宏观背景概述英语作文Title: Overview of Macroeconomic Background。

In understanding the macroeconomic landscape, it is imperative to analyze various key factors shaping the global economy. This essay provides a comprehensive overview of the current macroeconomic background, focusing on major economic indicators, trends, and challenges.Global Economic Performance:The global economy has experienced significant fluctuations in recent years, influenced by various factors such as geopolitical tensions, technological advancements, and the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic. Despite initial setbacks caused by the pandemic, many economies have shown resilience, albeit at varying paces of recovery.Growth and Output:Growth rates have been uneven across different regions. While some economies have demonstrated robust growth, others continue to grapple with sluggish recovery. China, for instance, has sustained its position as a key driver of global growth, albeit at a moderated pace compared to previous years. In contrast, advanced economies like the United States and European Union have witnessed moderate growth, hindered by supply chain disruptions andinflationary pressures.Inflation Dynamics:Inflation has emerged as a prominent concern in many economies. Supply chain disruptions, rising commodity prices, and increased demand have contributed toinflationary pressures globally. Central banks have responded by adopting various monetary policies to curb inflation while ensuring economic stability.Employment and Labor Markets:The labor market landscape has been shaped by evolvingwork patterns, including remote work and digitalization. While some sectors have witnessed job creation, others have faced challenges, leading to disparities in employment rates. Addressing skill mismatches and promoting workforce adaptability remain crucial for sustainable employment growth.Monetary Policy:Central banks worldwide have adopted accommodative monetary policies to support economic recovery. Interest rates have remained low, with some central banks implementing quantitative easing measures to stimulate lending and investment. However, concerns about inflation overshooting targets have prompted discussions about tightening monetary policy in the near future.Fiscal Policy:Governments have implemented expansive fiscal policies to mitigate the socio-economic impact of the pandemic. Stimulus packages, infrastructure investments, and socialwelfare programs have been pivotal in supporting households and businesses. However, concerns about mounting public debt and fiscal sustainability linger, necessitating prudent fiscal management strategies.Global Trade and Supply Chains:Global trade dynamics have been reshaped by supply chain disruptions, trade tensions, and shifts in consumer behavior. Protectionist measures and geopolitical tensions have hindered international trade flows, prompting callsfor greater multilateral cooperation and trade diversification strategies.Environmental and Social Considerations:The pursuit of sustainable development has gained prominence on the global agenda. Environmental challenges such as climate change and resource depletion underscore the need for green transitions and sustainable practices. Moreover, addressing social inequalities and promoting inclusive growth remain imperative for fostering long-termeconomic resilience.Conclusion:In conclusion, the macroeconomic landscape is characterized by a complex interplay of factors influencing global economic performance. While recovery efforts continue amidst lingering uncertainties, fostering resilience, sustainability, and inclusive growth remains paramount for navigating future challenges and fostering prosperity on a global scale.。

monetary policy restrictive -回复

monetary policy restrictive -回复该主题是“紧缩性货币政策(monetary policy restrictive)”,下面是一篇1500-2000字的文章来解答这个主题。

第一步:介绍货币政策和紧缩性货币政策货币政策是由中央银行制定和执行的一种政策,目的是通过控制货币供应量和利率来影响经济活动和通货膨胀水平。

紧缩性货币政策是其中一种,意味着中央银行采取措施来收紧经济,以控制通货膨胀和遏制过度经济增长。

第二步:紧缩性货币政策的工具紧缩性货币政策主要通过以下工具实施:1. 提高利率:中央银行可以提高政策利率,例如基准利率,从而提高借贷成本,减少个人和企业的借款和投资活动。

2. 减少货币供应量:中央银行可以通过减少银行存款准备金比率和出售国债等方式来减少货币供应量。

3. 调整外汇政策:中央银行可以调整汇率政策,以减少进口和增加出口,以抑制内需。

第三步:紧缩性货币政策的目标紧缩性货币政策的主要目标是控制通货膨胀水平。

当经济过热时,通货膨胀可能会加剧,导致物价上涨和失去购买力。

紧缩性货币政策通过提高利率和收紧货币供应量来抑制消费和投资需求,从而减缓通货膨胀压力。

第四步:紧缩性货币政策的优点1. 控制通货膨胀:紧缩性货币政策可以有效抑制通货膨胀,保持物价稳定,从而维持经济的可持续增长。

2. 遏制过度经济增长:当经济过热时,通货膨胀可能会增加,紧缩性货币政策可以通过收紧货币供应量和提高利率来抑制过度经济增长,防止经济泡沫的产生。

3. 促进投资稳定:通过提高利率,紧缩性货币政策可以减少虚假投资和资产泡沫,从而促进投资的稳定性和可持续性。

第五步:紧缩性货币政策的缺点1. 增加借款成本:紧缩性货币政策会导致借款成本上升,从而减少个人和企业的借贷活动,可能导致经济放缓和失业率上升。

2. 减少消费需求:通过提高利率和收紧货币供应量,紧缩性货币政策将减少人们的消费需求,对经济增长产生负面影响。

金融术语英语

金融英语术语inflation 通货膨胀deflation 通货紧缩tighter credit 紧缩信贷monetary policy 货币政策foreign exchange 外汇spot transaction 即期交易forward transaction 远期交易option forward transaction 择期交易swap transaction 调期交易quote 报价settlment and delivery 交割Treasury bond 财政部公债current-account 经常项目pickup in rice 物价上涨Federal Reserve 美联储buying rate 买入价selling rate 卖出价spread 差幅contract 合同at par 平价premium 升水discount 贴水direct quoation method 直接报价法indirect quoation method 间接报价法dividend 股息domestic currency 本币floating rate 浮动利率parent company 母公司credit swap 互惠贷款venture capital 风险资本book value 帐面价值physical capital 实际资本IPOinitial public offering 新股首发;首次公开发行job machine 就业市场welfare capitalism 福利资本主义collective market cap 市场资本总值glolbal corporation 跨国公司transnational status 跨国优势transfer price 转让价格consolidation 兼并leverage 杠杆financial turmoil/meltdown 金融危机file for bankruptcy 申请破产bailout 救助take over 收购buy out 购买某人的产权或全部货物go under 破产take a nosedive 股市大跌tumble 下跌falter 摇摇欲坠on the hook 被套住shore up confidence 提振市场信心stave off 挡开, 避开,liquidate assets 资产清算at fire sale prices 超低价sell-off 证券的跌价reserve 储备note 票据discount贴现circulate流通central bank 中央银行the Federal Reserve System联邦储备系统credit union 信用合作社paper currency 纸币credit creation 信用创造branch banking 银行分行制unit banking 单一银行制out of circulation 退出流通capital stock股本at par以票面价值计electronic banking电子银行banking holding company 公司银行the gold standard金本位the Federal Reserve Board 联邦储备委员会the stock market crash 股市风暴reserve ratio 准备金比率division of labor 劳动分工commodity money 商品货币legal tender 法定货币fiat money 法定通货a medium of exchange交换媒介legal sanction法律制裁face value面值liquid assets流动资产illiquidl assets非流动资产the liquidity scale 流动性指标real estate 不动产checking accounts,demand deposit,checkable deposit 活期存款time deposit 定期存款negotiable order of withdrawal accounts 大额可转让提款单money market mutual funds 货币市场互助基金repurchase agreements 回购协议certificate of deposits存单bond 债券stock股票travelers'checks 旅行支票small-denomination time deposits小额定期存款large-denomination time deposits大额定期存款bank overnight repurchase agreements 银行隔夜回购协议bank long-term repurchase agreements 银行长期回购协议thrift institutions 存款机构financial institution 金融机构commercial banks商业银行a means of payment 支付手段a store of value储藏手段a standard of value价值标准deficit 亏损roll展期wholesale批发default不履约auction拍卖collateralize担保markup价格的涨幅dealer交易员broker经纪人pension funds 养老基金face amount面值commerical paper商业票据banker's acceptance银行承兑汇票Fed fund 联邦基金eurodollar欧洲美元treasury bills 国库券floating-rate 浮动比率fixed-rate 固定比率default risk 拖欠风险credit rating信誉级别tax collection税收money market货币市场capital market资本市场original maturity 原始到期期限surplus funds过剩基金syndication辛迪加underwrite包销,认购hedge对冲买卖、套期保值innovation到期交易spread利差principal本金swap掉期交易eurobond market 欧洲债券市场euronote欧洲票据Federal Reserve Bank FRB联邦储备银行unsecured credit无担保贷款fixed term time deposit定期支付存款lead bank牵头银行neogotiable time deposit议付定期存款inter-bank money market银行同业货币市场medium term loan 中期贷款syndicated credit银团贷款merchant bank商业银行portfolio management 有价债券管理lease financing租赁融资note issurance facility票据发行安排bearer note不记名票价underwriting facility包销安排floating-rate note 浮动利率票据bond holder债券持持有者London Interbank Offered RateLIBOR伦敦同业优惠利率back-up credit line备用信贷额promissory note..p/n本票revolving cerdit 循环信用证,即revolving letter of creditnon interest-bearing reserves无息储备金interest rate controls 利率管制interest rate ceiling 利率上限interest rate floor 利率下限破产 insolvency有偿还债务能力的 solvent合同 contract汇率 exchange rate私营部门 private sector财政管理机构 fiscal authorities宽松的财政政策 slack fiscal policy税法 tax bill财政 public finance财政部 the Ministry of Finance平衡预算 balanced budget继承税 inheritance tax货币主义者 monetariest增值税 VAT value added tax收入 revenue总需求aggregate demand货币化 monetization赤字 deficit经济不景气 recessiona period when the economy of a country is notsuccessful, business conditions are bad, industrialproduction and trade are at a low level and thereis a lot of unemployment经济好转 turnabout复苏 recovery成本推进型 cost push货币供应 money supply生产率 productivity劳动力 labor force实际工资 real wages成本推进式通货膨胀 cost-push inflation需求拉动式通货膨胀demand-pull inflation双位数通货膨胀 double- digit inflation极度通货膨胀 hyperinflation长期通货膨胀 chronic inflation治理通货膨胀 to fight inflation最终目标 ultimate goal坏的影响 adverse effect担保 ensure贴现 discount萧条的 sluggish认购 subscribe to支票帐户 checking account 货币控制工具 instruments of monetry control借据 IOUsI owe you本票promissory notes货币总监 controller of the currency拖收系统 collection system支票清算或结算 check clearing资金划拨 transfer of funds可以相信的证明 credentials改革 fashion被缠住 entangled货币联盟 Monetary Union再购协议 repo精明的讨价还价交易 horse-trading欧元 euro公共债务membership criteria汇率机制 REM储备货币 reserve currency劳动密集型labor-intensive股票交易所 bourse竞争领先 frontrun牛市 bull market非凡的牛市 a raging bull规模经济 scale economcies买方出价与卖方要价之间的差价 bid-ask spreads期货股票 futures经济商行 brokerage firm回报率rate of return股票 equities违约 default现金外流 cash drains经济人佣金 brokerage fee存款单 CDcertificate of deposit营业额 turnover资本市场 capital market布雷顿森林体系 The Bretton Woods System经常帐户current account套利者 arbitrager远期汇率 forward exchange rate即期汇率 spot rate实际利率 real interest rates货币政策工具 tools of monetary policy银行倒闭 bank failures跨国公司 MNC Multi-National Corporation 商业银行 commercial bank商业票据 comercial paper利润 profit本票,期票promissory notes监督 to monitor佣金经济人 commission brokers套期保值hedge有价证券平衡理论 portfolio balance theory外汇储备 foreign exchange reserves固定汇率 fixed exchange rate浮动汇率floating/flexible exchange rate货币选择权期货 currency option套利arbitrage合约价 exercise price远期升水 forward premium多头买升 buying long空头卖跌 selling short按市价订购股票 market order股票经纪人stockbroker国际货币基金 the IMF七国集团 the G-7监督 surveillance同业拆借市场 interbank market可兑换性 convertibility软通货 soft currency 限制 restriction交易 transaction充分需求 adequate demand短期外债short term external debt汇率机制 exchange rate regime直接标价 direct quotes资本流动性 mobility of capital赤字 deficit本国货币 domestic currency外汇交易市场 foreign exchange market国际储备 international reserve利率 interest rate资产 assets国际收支 balance of payments贸易差额 balance of trade繁荣 boom债券 bond资本 captial资本支出 captial expenditures商品 commodities商品交易所 commodity exchange期货合同commodity futures contract普通股票 common stock联合大企业 conglomerate 货币贬值 currency devaluation通货紧缩 deflation折旧 depreciation贴现率 discount rate归个人支配的收入 disposable personal income从业人员employed person汇率 exchange rate财政年度fiscal year自由企业 free enterprise国民生产总值 gross antional product库存 inventory劳动力人数 labor force债务 liabilities市场经济 market economy合并 merger货币收入 money income跨国公司 Multinational Corproation个人收入 personal income优先股票 preferred stock价格收益比率 price-earning ratio优惠贷款利率 prime rate利润 profit回报 return on investment使货币升值revaluation薪水 salary季节性调整 seasonal adjustment关税 tariff失业人员 unemployed person效用 utility价值 value工资 wages工资价格螺旋上升 wage-price spiral收益 yield补偿贸易 compensatory trade, compensated deal储蓄银行 saving banks欧洲联盟 the European Union单一的实体 a single entity抵押贷款 mortgage lending业主产权 owner's equity普通股common stock无形资产 intangible assets收益表 income statement营业开支 operating expenses行政开支 administrative expenses现金收支一览表statement of cash flow贸易中的存货 inventory收益 proceeds投资银行investment bank机构投资者 institutional investor垄断兼并委员会 MMC招标发行 issue by tender定向发行 introduction代销 offer for sale直销placing公开发行 public issue信贷额度 credit line国际债券international bonds欧洲货币Eurocurrency利差 interest margin以所借的钱作抵押所获之贷款 leveraged loan权利股发行 rights issues净收入比例结合 net income gearing证券行业词汇share, equity, stock 股票、股权;bond, debenture, debts 债券;negotiable share 可流通股份;convertible bond 可转换债券;treasury/government bond 国库券/政府债券;corporate bond 企业债券;closed-end securities investment fund 封闭式证券投资基金;open-end securities investment fund 开放式证券投资基金;fund manager 基金经理/管理公司;fund custodian bank 基金托管银行;market capitalization 市值;p/e ratio 市盈率;price/earningmark-to-market 逐日盯市;payment versus delivery 银券交付;clearing and settlement 清算/结算;commodity/financial derivatives 商品/金融衍生产品;put / call option 看跌/看涨期权;margins, collateral 保证金;rights issue/offering 配股;bonus share 红股;dividend 红利/股息;ADR 美国存托凭证/存股证;American Depository ReceiptGDR 全球存托凭证/存股证;Global Depository Receiptretail/private investor 个人投资者/散户;institutional investor 机构投资者;broker/dealer 券商;proprietary trading 自营;insider trading/dealing 内幕交易;market manipulation 市场操纵;prospectus 招股说明书;IPO 新股/初始公开发行;Initial Public Offeringmerger and acquisition 收购兼并;会计与银行业务用语汇总汇款用语汇款||寄钱 to remit||to send money寄票供取款||支票支付 to send a cheque for payment寄款人 a remitter收款人 a remittee汇票汇单用语国外汇票 foreign Bill国内汇票 inland Bill跟单汇票 documentary bill空头汇票 accommodation bill原始汇票 original bill改写||换新票据 renewed bill即期汇票 sight bill||bill on demand... days after date||... days' after date ... 日后付款... months after date||... months' after date ... 月后付款见票后... 日付款... days' after sight||... days' sight见票后... 月付款... months' after sight||... months' sight 同组票据 set of bills单张汇票 sola of exchange||sole of exchange远期汇票 usance bill||bill at usance长期汇票 long bill短期汇票 short bill逾期汇票 overdue bill宽限日期 days of grace电汇 telegraphic transfer邮汇 postal order||postal note Am.||post office order||money order 本票 promissory note P/N押汇负责书||押汇保证书 letter of hypothecation副保||抵押品||付属担保物 collateral security担保书 trust receipt||letter of indemnity承兑||认付 acceptance单张承兑 general acceptance有条件承兑 qualified acceptance附条件认付 conditional acceptance部分认付 partial acceptance拒付||退票 dishonour拒绝承兑而退票 dishonour by non-acceptance由于存款不足而退票 dihonour by non-payment提交 presentation背书 endorsement||indorsement无记名背书 general endorsement||blank endorsement记名式背书 special endorsement||full endorsement附条件背书 conditional endorsement限制性背书 restrictive endorsement无追索权背书 endorsement without recourse期满||到期 maturity托收 collection新汇票||再兑换汇票 re-exchange||re-draft外汇交易 exchange dealing||exchange deals汇兑合约 exchange contract汇兑合约预约 forward exchange contract外汇行情 exchange quotation交易行情表 course of exchange||exchange table汇价||兑换率 exchange rate||rate of exchange官方汇率 official rate挂牌汇率||名义汇率 nominal rate现汇汇率 spot rate电汇汇率||电汇率|| . rate||telegraphic transfer rate兑现率||兑现汇率demand rate长期汇率 long rate私人汇票折扣率 rate on a private bill远期汇票兑换率 forward rate套价||套汇汇率||裁定外汇行情 cross rate付款汇率 pence rate当日汇率||成交价 currency rate套汇||套价||公断交易率arbitrage汇票交割||汇票议付 negotiation of draft交易人||议付人negotiator票据交割||让与支票票据议付 to negotiatie a bill折扣交割||票据折扣 to discount a bill票据背书 to endorse a bill应付我差额51,000美元 a balance due to us of $51,000||a balance in our favour of $ 51,000收到汇款 to receive remittance填写收据 to make out a receipt付款用语付款方法 mode of payment现金付款 payment by cash||cash payment||payment by ready cash以支票支付 payment by cheque以汇票支付 payment by bill 以物品支付 payment in kind付清||支付全部货款 payment in full||full payment支付部分货款||分批付款 payment in part||part payment||partial payment记帐付款||会计帐目内付款 payment on account定期付款 payment on term年分期付款 annual payment月分期付款 monthly payment||monthly instalment延滞付款 payment in arrear预付货||先付 payment inadvance||prepayment延付货款 deferred payment立即付款 promptpayment||immediate payment暂付款 suspense payment延期付款 delay in payment||extension of payment支付票据 payment bill名誉支付||干与付款payment for honour||payment by intervention结帐||清算||支付 settlement 分期付款 instalment滞付||拖欠||尾数款未付 arrears特许拖延付款日 days of grace保证付款 del credere付款 to pay||to make payment||to make effect payment结帐 to settle||to make settlement||to make effectsettlement||to square||to balance支出||付款 to defray||to disburse结清 to clear off||to pya off请求付款 to ask for payment||to request payment恳求付帐 to solicit payment拖延付款 to defer payment||to delay payment付款被拖延 to be in arrears with payment还债 to discharge迅速付款 to pay promptly付款相当迅速 to pay moderately well||to pay fairly well||to keep the engagements regularly付款相当慢 to pay slowly||to take extended credit付款不好 to pay badly||to be generally in arrear with payments付款颇为恶劣 to pay very badly||to never pay unless forced拒绝付款 to refuse payment||to refuse to pay||to dishonour a bill相信能收到款项 We shall look to you for the payment||We shall depend upon you for thepayment ||We expect payment from you惠请付款 kindly pay the amount||please forward payment||please forward a cheque.我将不得不采取必要步骤运用法律手段收回该项货款 I shall be obliged to take thenecessary steps to legally recover the amount. ||I shall be compelled to take steps to enforcepayment.惠请宽限 let the matter stand over till then.||allow me a short extension of time. ||Kindlypostpone the time for payment a little longer.索取利息 to charge interest附上利息 to draw interest||to bear interest||to allow interest生息 to yield interest生息3% to yield 3%存款 to deposit in a bank||to put in a bank||to place on deposit||to make deposit在银行存款 to have money in a bank||to have a bank account||to have money on deposit向银行提款 to withdraw one's deposit from a bank换取现金 to convert into money||to turn into cash||to realize 折扣用语从价格打10%的折扣 to make a discount of 10% off the price||to make 10%discount off the price打折扣购买 to buy at a discount打折扣出售 to sell at a discount打折扣-让价 to reduce||to make a reduction减价 to deduct||to make a deduction回扣 to rebate现金折扣 cash discount 货到付现款 cash on arrival即时付款 prompt cash净价||最低价格付现 net cash现金付款 ready cash即期付款 spot cash||cash down||cash on the nail 凭单据付现款 cash against documents凭提单付现款 cash against bills of lading承兑交单 documents against acceptance D/A付款交单 documents against payment D/P折扣例文除非另有说明, 30日后全额付现, 如有错误, 请立即通知;Net cash 30 days unless specified otherwise. Advise promptly if incorrect.付款条件: 30日后全额付现, 10日后付现打2%折扣, 过期后付款时, 加上利率为6%的利息;Terms, net cash 30 days, or, less 2% 10 days. Interest charged at the rate of 6% after maturity.付款条件: 月底后10日后付现2%折扣, 现在付现3%折扣, 否则, 全额付现;财会名词1会计与会计理论会计 accounting 决策人 Decision Maker 投资人 Investor 股东Shareholder 债权人 Creditor 财务会计 Financial Accounting 管理会计Management Accounting 成本会计 Cost Accounting 私业会计 Private Accounting 公众会计 Public Accounting注册会计师 CPA Certified Public Accountant国际会计准则委员会 IASC 美国注册会计师协会 AICPA 财务会计准则委员会FASB 管理会计协会 IMA美国会计学会 AAA 税务稽核署 IRS 独资企业 Proprietorship合伙人企业 Partnership 公司 Corporation会计目标 Accounting Objectives 会计假设 Accounting Assumptions会计要素 Accounting Elements 会计原则 Accounting Principles会计实务过程 Accounting Procedures 财务报表 Financial Statements财务分析 Financial Analysis会计主体假设 Separate-entity Assumption货币计量假设 Unit-of-measure Assumption持续经营假设 ContinuityGoing-concern Assumption会计分期假设 Time-period Assumption 资产 Asset 负债 Liability业主权益 Owner's Equity 收入 Revenue 费用 Expense 收益 Income 亏损Loss历史成本原则 Cost Principle收入实现原则 Revenue Principle配比原则 Matching Principle全面披露原则 Full-disclosure Reporting principle客观性原则 Objective Principle 一致性原则 Consistent Principle 可比性原则 Comparability Principle重大性原则 Materiality Principle稳健性原则 Conservatism Principle权责发生制 Accrual Basis 现金收付制 Cash Basis财务报告 Financial Report 流动资产 Current assets流动负债 Current Liabilities 长期负债 Long-term Liabilities投入资本 Contributed Capital留存收益 Retained Earning2会计循环会计循环 Accounting Procedure/Cycle会计信息系统 Accounting information System帐户 Ledger 会计科目 Account 会计分录 Journal entry原始凭证 Source Document 日记帐 Journal总分类帐 General Ledger 明细分类帐 Subsidiary Ledger试算平衡 Trial Balance 现金收款日记帐 Cash receipt journal现金付款日记帐 Cash disbursements journal销售日记帐 Sales Journal 购货日记帐 Purchase Journal 普通日记帐General Journal 工作底稿 Worksheet调整分录 Adjusting entries 结帐 Closing entries3现金与应收帐款现金 Cash 银行存款 Cash in bank 库存现金 Cash in hand流动资产 Current assets 偿债基金 Sinking fund定额备用金 Imprest petty cash 支票 Checkcheque银行对帐单 Bank statement银行存款调节表 Bank reconciliation statement在途存款 Outstanding deposit 在途支票 Outstanding check应付凭单 Vouchers payable 应收帐款 Account receivable应收票据 Note receivable 起运点交货价 shipping point目的地交货价 destination point 商业折扣 Trade discount现金折扣 Cash discount 销售退回及折让 Sales return and allowance 坏帐费用 Bad debt expense 备抵法 Allowance method 备抵坏帐 Bad debt allowance损益表法 Income statement approach 资产负债表法 Balance sheet approach帐龄分析法 Aging analysis method 直接冲销法 Direct write-off method带息票据 Interest bearing note 不带息票据 Non-interest bearing note出票人 Maker 受款人 Payee 本金 Principal 利息率 Interest rate到期日 Maturity date 本票 Promissory note 贴现 Discount背书 Endorse 拒付费 Protest fee4存货存货 Inventory 商品存货 Merchandise inventory 产成品存货 Finished goods inventory在产品存货 Work in process inventory原材料存货 Raw materials inventory起运地离岸价格 shipping point目的地抵岸价格 destination寄销 Consignment 寄销人 Consignor 承销人 Consignee定期盘存 Periodic inventory 永续盘存 Perpetual inventory购货 Purchase 购货折让和折扣 Purchase allowance and discounts存货盈余或短缺 Inventory overages and shortages分批认定法 Specific identification 加权平均法 Weighted average先进先出法 First-in, first-out or FIFO后进先出法 Lost-in, first-out or LIFO 移动平均法 Moving average成本或市价孰低法 Lower of cost or market or LCM市价 Market value 重置成本 Replacement cost可变现净值 Net realizable value上限 Upper limit 下限 Lower limit 毛利法 Gross margin method零售价格法 Retail method 成本率 Cost ratio5长期投资长期投资 Long-term investment 长期股票投资 Investment on stocks长期债券投资 Investment on bonds 成本法 Cost method权益法 Equity method合并法 Consolidation method 股利宣布日 Declaration date股权登记日 Date of record 除息日 Ex-dividend date 付息日 Payment date 债券面值 Face value, Par value债券折价 Discount on bonds 债券溢价 Premium on bonds票面利率 Contract interest rate, stated rate市场利率 Market interest ratio, Effective rate普通股 Common Stock 优先股 Preferred Stock现金股利 Cash dividends股票股利 Stock dividends 清算股利 Liquidating dividends到期日 Maturity date到期值 Maturity value直线摊销法 Straight-Line method of amortization实际利息摊销法 Effective-interest method of amortization6固定资产固定资产 Plant assets or Fixed assets 原值 Original value预计使用年限 Expected useful life预计残值 Estimated residual value 折旧费用 Depreciation expense累计折旧 Accumulated depreciation 帐面价值 Carrying value应提折旧成本 Depreciation cost 净值 Net value在建工程 Construction-in-process 磨损 Wear and tear 过时 Obsolescence 直线法 Straight-line method SL工作量法 Units-of-production method UOP加速折旧法 Accelerated depreciation method双倍余额递减法 Double-declining balance method DDB年数总和法 Sum-of-the-years-digits method SYD以旧换新 Trade in 经营租赁 Operating lease 融资租赁 Capital lease 廉价购买权 Bargain purchase option BPO 资产负债表外筹资 Off-balance-sheet financing最低租赁付款额 Minimum lease payments7无形资产无形资产 Intangible assets 专利权 Patents 商标权 Trademarks, Trade names 着作权 Copyrights 特许权或专营权 Franchises 商誉 Goodwill 开办费 Organization cost租赁权 Leasehold 摊销 Amortization8流动负债负债 Liability 流动负债 Current liability 应付帐款 Account payable应付票据 Notes payable 贴现票据 Discount notes长期负债一年内到期部分 Current maturities of long-term liabilities 应付股利 Dividends payable 预收收益 Prepayments by customers存入保证金 Refundable deposits 应付费用 Accrual expense增值税 Value added tax 营业税 Business tax应付所得税 Income tax payable 应付奖金 Bonuses payable产品质量担保负债 Estimated liabilities under product warranties赠品和兑换券 Premiums, coupons and trading stamps或有事项 Contingency 或有负债 Contingent 或有损失 Loss contingencies 或有利得 Gain contingencies 永久性差异 Permanent difference时间性差异 Timing difference 应付税款法 Taxes payable method纳税影响会计法 Tax effect accounting method递延所得税负债法 Deferred income tax liability method9长期负债长期负债 Long-term Liabilities 应付公司债券 Bonds payable有担保品的公司债券 Secured Bonds抵押公司债券 Mortgage Bonds 保证公司债券 Guaranteed Bonds信用公司债券 Debenture Bonds 一次还本公司债券 Term Bonds分期还本公司债券 Serial Bonds 可转换公司债券 Convertible Bonds可赎回公司债券 Callable Bonds 可要求公司债券 Redeemable Bonds记名公司债券 Registered Bonds 无记名公司债券 Coupon Bonds普通公司债券 Ordinary Bonds 收益公司债券 Income Bonds名义利率,票面利率 Nominal rate 实际利率 Actual rate有效利率 Effective rate 溢价 Premium 折价 Discount面值 Par value 直线法 Straight-line method实际利率法 Effective interest method到期直接偿付 Repayment at maturity 提前偿付 Repayment at advance偿债基金 Sinking fund 长期应付票据 Long-term notes payable抵押借款 Mortgage loan10业主权益权益 Equity 业主权益 Owner's equity股东权益 Stockholder's equity 投入资本 Contributed capital 缴入资本Paid-in capital 股本 Capital stock资本公积 Capital surplus 留存收益 Retained earnings核定股本 Authorized capital stock 实收资本 Issued capital stock 发行在外股本 Outstanding capital stock 库藏股 Treasury stock 普通股 Common stock 优先股 Preferred stock累积优先股 Cumulative preferred stock非累积优先股 Noncumulative preferred stock完全参加优先股 Fully participating preferred stock部分参加优先股 Partially participating preferred stock非部分参加优先股 Nonpartially participating preferred stock现金发行 Issuance for cash 非现金发行 Issuance for noncash consideration股票的合并发行 Lump-sum sales of stock 发行成本 Issuance cost成本法 Cost method 面值法 Par value method捐赠资本 Donated capital 盈余分配 Distribution of earnings 股利Dividend 股利政策 Dividend policy宣布日 Date of declaration 股权登记日 Date of record除息日 Ex-dividend date股利支付日 Date of payment 现金股利 Cash dividend股票股利 Stock dividend 拨款 appropriation11财务报表财务报表 Financial Statement 资产负债表 Balance Sheet收益表 Income Statement 帐户式 Account Form报告式 Report Form 编制报表 Prepare工作底稿 Worksheet 多步式 Multi-step 单步式 Single-step12财务状况变动表财务状况变动表中的现金基础 Basis现金流量表财务状况变动表中的营运资金基础 Capital Basis资金来源与运用表营运资金Working Capital 全部资源概念 All-resources concept直接交换业务 Direct exchanges 正常营业活动 Normal operating activities财务活动 Financing activities 投资活动 Investing activities13财务报表分析财务报表分析Analysis of financial statements比较财务报表 Comparative financial statements趋势百分比 Trend percentage 比率 Ratios普通股每股收益Earnings per share of common stock股利收益率 Dividend yield ratio 价益比 Price-earnings ratio普通股每股帐面价值 Book value per share of common stock资本报酬率 Return on investment 总资产报酬率 Return on total asset债券收益率 Yield rate on bonds已获利息倍数 Number of times interest earned债券比率 Debt ratio 优先股收益率 Yield rate on preferred stock营运资本 Working Capital 周转 Turnover 存货周转率 Inventory turnover应收帐款周转率 Accounts receivable turnover流动比率 Current ratio 速动比率 Quick ratio 酸性试验比率 Acid test ratio14合并财务报表合并财务报表 Consolidated financial statements 吸收合并 Merger 创立合并 Consolidation 控股公司 Parent company 附属公司 Subsidiary company少数股权 Minority interest权益联营合并 Pooling of interest 购买合并Combination by purchase权益法 Equity method 成本法 Cost method15物价变动中的会计计量物价变动之会计 Price-level changes accounting一般物价水平会计 General price-level accounting货币购买力会计Purchasing-power accounting统一币值会计 Constant dollar accounting历史成本 Historical cost 现行价值会计 Current value accounting现行成本Current cost 重置成本 Replacement cost物价指数 Price-level index国民生产总值物价指数 Gross national product implicit price deflatoror GNP deflator消费物价指数 Consumer price index or CPI批发物价指数 Wholesale price index货币性资产 Monetary assets货币性负债 Monetary liabilities 货币购买力损益 Purchasing-power gains or losses资产持有损益 Holding gains or losses未实现的资产持有损益 Unrealized holding gains or losses 现行价值与统一币值会计 Constant dollar and current cost accounting。

宏观经济学原理(第七版)曼昆 名词解释(带英文)

宏观经济学原理曼昆名词解释微观经济学(microeconomics),研究家庭和企业如何做出决策,以及它们如何在市场上相互影响。

宏观经济学(macroeconomics),研究整体经济现象,包括通货膨胀、失业和经济增长。

国内生产总值GDP(gross domestic product),在某一既定时期,一个国家内生产的所有最终物品与服务的市场价值。

消费(consumption),家庭除购买新住房之外,用于物品与服务的支出。

投资(investment),用于资本设备、存货和建筑物的支出,包括家庭用于购买新住房的支出。

政府购买(government purchase),地方、州和联邦政府用于物品与服务的支出。

净出口(net export),外国人对国内生产的物品的支出(出口),减国内居民对外国物品的支出(进口)。

名义GDP(nominal GDP),按现期价格评价的物品与服务的生产。

真实GDP(real GDP),按不变价格评价的物品与服务的生产。

(总之,名义GDP是用当年价格来评价经济中物品与服务生产的价值,真实GDP是用不变的基年价格来评价经济中物品与服务生产的价值。

)GDP平减指数(GDP, deflator),用名义GDP与真实GDP的比率乘以100计算的物价水平衡量指标。

消费物价指数CPI(consumer price index),普通消费者所购买的物品与服务的总费用的衡量指标。

通货膨胀率(inflation rate),从前一个时期以来,物价指数变动的百分比。

生产物价指数(producer price index),企业所购买的一篮子物品运服务的费用的衡量指标。

指数化(indexation),根据法律或合同按照通货膨胀的影响,对货币数量的自动调整。

名义利率(nominal interest rate),通常公布的、未根据通货膨胀的影响,校正的利率。

真实利率(real interest rate),根据通货膨胀的影响校正过的利率。

AP宏观经济学必考英文词汇汇总

AP宏观经济学必考英文词汇汇总

以下是一些AP宏观经济学中可能会涉及的必考英文词汇:

1. Aggregate demand(总需求)

2. Aggregate supply(总供给)

3. Inflation(通货膨胀)

4. Deflation(通货紧缩)

5.GDP(国内生产总值)

6. Unemployment rate(失业率)

7. Consumer price index (CPI)(消费者物价指数)

8. Monetary policy(货币政策)

9. Fiscal policy(财政政策)

10. Government spending(政府支出)

11. Taxation(税收)

12. Interest rate(利率)

13. Exchange rate(汇率)

14. Budget deficit(预算赤字)

15. Trade deficit(贸易逆差)

16. Balance of payments(国际收支)

17. National debt(国债)

18. Economic growth(经济增长)

19. Recession(经济衰退)

20. Expansion(经济扩张)

21. Macroeconomics(宏观经济学)

22. Microeconomics(微观经济学)

这些词汇在AP宏观经济学考试中经常出现,理解并掌握它们的含义对于正确理解和分析经济问题至关重要。

经济学专业术语(中英文对照)