食管癌6

食管癌的6大早期信号和8个高危人群

食管癌的6大早期信号和8个高危人群食管癌是常见的消化道恶性肿瘤之一,其早期症状不明显,很容易被忽视。

如果能够早期发现食管癌,可以明显提高治愈率和生存率。

下面我们介绍一下食管癌的6大早期信号和8个高危人群。

一、食管癌的6大早期信号:1.吞咽困难:食管癌位于食管上一段,当肿瘤发展到一定程度时,会引起食管狭窄,从而导致吞咽困难。

这种吞咽困难逐渐加重,最初可能只是感到食物卡住,需要多咀嚼、多喝水才能咽下,而后逐渐发展为食物完全无法通过。

2.胸骨后灼热感:食管癌患者常常有一种胸骨后灼热感,类似胃溃疡的疼痛感。

这种疼痛会随食物进入食管而加重,可以通过服用抗酸药物缓解。

3.体重下降:食管癌患者因为吞咽困难,食物摄入减少,导致体重下降。

这种体重下降常常是无法预料的,即使没有节食也会出现。

4.胸痛:食管癌患者在吞咽困难同时可能会出现胸痛的情况。

这种胸痛常常是持续性的,可以放射到背部。

5.咳嗽和喉咙痛:食管癌患者可能会出现咳嗽和喉咙痛的症状,这是因为食管癌肿瘤扩散到喉咙和气管引起的。

6.消化不良:食管癌患者可能会出现消化不良的症状,如腹胀、恶心和呕吐等。

二、食管癌的8个高危人群:1.长期吸烟:长期吸烟增加了患食管癌的风险,尤其是烟量大的人。

2.长期饮酒:长期饮酒会增加患上食管癌的风险,尤其是饮酒量大的人。

3.慢性食管炎:长期慢性食管炎可能会导致食管上皮细胞的恶性变,进而发展为食管癌。

4.食管裂孔疝:食管裂孔疝是指食管通过膈肌向上突出,这种情况容易导致食管酸逆流,刺激食管上皮,增加了食管癌的患病风险。

5.家族遗传:某些食管癌与家族遗传有关,家族中有患食管癌的人,其直系亲属患上食管癌的风险会显著增加。

6.不良饮食习惯:长期不良饮食习惯,如高盐、高脂肪、低纤维等,会增加食管癌的患病风险。

7.放射线和化学物质暴露:长期接触放射线和一些化学物质,如亚硝酸盐、亚硝酸胺等,会增加食管癌的发生几率。

8.年龄:食管癌多见于中老年人,随着年龄的增加,食管癌的发病率也会逐渐增加。

食道癌来临前 身体有6种不起眼表现

食道癌来临前身体有6种不起眼表现食道癌是一种恶性肿瘤,起源于食道的上皮细胞,常见于中老年人。

食道癌的早期症状并不明显,很多患者往往容易忽略。

然而,一些不起眼的身体表现可能是食道癌来临前的信号,如果能够及早发现并采取有效的治疗措施,就能够提高治愈率和生存率。

以下是6种不起眼的身体表现,可能是食道癌的前兆。

首先,食欲减退。

食道癌的早期症状之一就是食欲减退,患者可能感觉没有胃口,对食物的味道也没有以往那么感兴趣。

他们可能会经常感觉吃饭时饱腹感很快,尤其是吃一点点食物后就感觉非常饱,甚至是一点点东西也吃不下。

如果食欲减退持续时间较长,就需要引起重视。

其次,咽部不适。

食道癌的发生部位接近咽喉,因此,在癌症发展的早期阶段,患者可能会感觉咽部不适。

咽部不适可能表现为轻微的疼痛、灼烧感或者痒感,有时还会出现咽喉异物感。

如果这种不适感不断加重,就需要及时就医。

第三,吞咽困难。

食道癌发展到一定阶段后,会影响食道的正常蠕动,导致食物难以顺利通过食道进入胃部。

患者可能会感觉吞咽困难,这种困难可能表现为感觉卡在胸口、喉咙、食道中部等地方,需要多次大力咽喉才能够成功吞咽。

如果吞咽困难持续存在,建议尽快到医院进行检查。

第四,体重减轻。

许多患者在食道癌早期都没有明显的食欲减退,然而他们却不知不觉地减重了。

体重减轻可能是机体代谢发生问题的信号,可能是肿瘤消耗大量能量的结果。

如果体重减轻是无明显原因的,并且持续时间较长,建议及时就医。

第五,嗳气、反酸。

食道癌的发展会导致食道下部括约肌的功能受损,胃酸容易逆流进入食道,造成嗳气、反酸等症状。

虽然这种症状并不一定是食道癌,但如果这种症状持续时间较长或者频繁发作,应尽早到医院检查。

最后,胸腹痛。

食道癌发展到一定阶段后,肿瘤可能侵犯周围组织和器官,引起胸腹痛。

这种疼痛可能表现为胸骨后疼痛、腹部隐痛或刺痛等。

如果这种疼痛久治不愈,甚至还出现呼吸困难、吐血等情况,就需要立即就医。

总之,食道癌的早期症状并不明显,容易被忽略。

食管癌淋巴结分组

胸内淋巴结的分组:1~4组淋巴结为上纵隔淋巴结;5、6组淋巴结称为主动脉淋巴结;7、8、9组淋巴结为下纵隔淋巴结;10~14组淋巴结为N1淋巴结,所有的N1淋巴结均在纵隔胸膜返折远侧,位于脏层胸膜内。

第1组淋巴结群:在上纵隔胸腔内上1/3气管的周围,其双侧以锁骨下动脉的上缘作水平线以上,中间与左无名静脉上缘以上为界。

第2组淋巴结群:气管旁淋巴结,位于第一组淋巴结与第四组淋巴结之间的气管旁两侧。

第3组淋巴结群: 分为气管前和气管后淋巴结两组。

在气管后面的淋巴结又称为3p组,气管与上腔静脉与无名静脉之间的淋巴结为3a组。

第4组淋巴结群:位于气管与左右主气管分杈后周围的淋巴结,右侧通常在奇静脉下方,而左侧的常在纵隔内主动脉之下。

第5组淋巴结群:位于主动脉之下的主肺动脉韧带的周围。

第6组淋巴结群:位于升主动脉,主动脉弓的前面和两侧,迷走神经前面。

第7组淋巴结群:位于气管与左右主气管分杈下的淋巴结。

第8组淋巴结群:位于气管与左右主气管分杈下,食管周围的淋巴结。

第9组淋巴结群:紧贴下肺静脉之下缘,下肺韧带之内的淋巴结。

第10组淋巴结群:从双侧主支气管开口第一个软骨环开始至其刚开始分杈为上下肺叶支气管的最后一个软骨环外的淋巴结。

第11组淋巴结群:位于肺内各肺叶支气管之间的淋巴结,在右侧,上肺叶与中肺叶支气管之间为11s群;中肺叶与下肺叶支气管之间为11i群。

第12组淋巴结群:位于肺叶支气管周围的淋巴结。

第13组淋巴结群:位于肺段支气管周围的淋巴结。

第14组淋巴结群:位于亚段支气管起远端周围的淋巴结。

那么食管癌的淋巴结分组则是:肺淋巴结前10组,加上胃的淋巴结前9组(后者在数字前加1);第18版的克氏外科学的图如下:还有一种就是日本的分类方法:100 颈浅淋巴结 101 颈段食管旁淋巴结 102 颈深淋巴结 103 咽后淋巴结 104锁骨上淋巴结 105 上胸段食管旁淋巴结 106 胸主支气管旁淋巴结 107 气管分叉淋巴结 108 中胸段食管旁淋巴结 109 肺门淋巴结 110 下胸段食管旁淋巴结 111 膈肌淋巴结 112 后纵隔淋巴结。

食管癌(讲课课件)

手术切除

通过手术将食管癌变部分 切除,以达到根治的目的。

淋巴结清扫

在手术过程中,对可能转 移的淋巴结进行清扫,以 降低复发风险。

术后护理

手术后需进行严格的护理 和康复,包括饮食调整、 呼吸道管理、疼痛控制等。

放射治疗

放疗原理

放射治疗通过高能射线杀 死癌细胞,达到治疗目的。

放疗效果

放射治疗对早期食管癌效 果较好,但对晚期食管癌 效果有限。

食管癌具有一定的家族聚集性,部分患者存在遗 传易感性。

02 环境因素

长期吸烟、饮酒、不良饮食习惯等环境因素可增 加食管癌的发病风险。

03 慢性炎症

食管慢性炎症、反流性食管炎等慢性炎症疾病可 能增加食管癌的发病风险。

食管癌的症状与体征

01 早期症状

早期食管癌可能出现吞咽不适、异物感、胸骨后 疼痛等症状。

通过内镜检查可以发现早 期食管癌或癌前病变。

食管癌标志物检测

检测血液中食管癌标志可以观 察食管黏膜的形态和功能 变化,发现异常病变。

病理组织学检查

通过病理组织学检查可以 确诊食管癌或癌前病变。

患者管理与康复

心理支持

食管癌患者需要心理 支持,帮助其面对疾 病和治疗带来的心理

健康饮食

保持均衡饮食,增加蔬菜、水果、全 谷类食物的摄入,减少高热量、高脂

肪和高盐食物的摄入。

控制体重

保持健康的体重,避免肥胖,有助于 预防食管癌。

戒烟限酒

戒烟和限制酒精摄入有助于降低食管 癌的风险。

避免长期慢性炎症

积极治疗口腔和咽喉部的慢性炎症, 减少对食管黏膜的刺激和损伤。

早期筛查与诊断

定期进行内镜检查

早期食管癌通常无明显症 状,可能出现吞咽不适、 胸骨后疼痛或烧灼感等。

食管癌是怎样检查出来的

食管癌是怎样检查出来的食管癌是常见的恶性肿瘤,我国是食管癌的高发病区,准确诊断治疗能够有效实现患者的康复,食管癌是指由食管发生的恶性肿瘤,其发生往往有一个漫长的过程,也就是说不可能象感冒发热一样突然冒出来。

一般认为,食管的发生要经过上皮不典型增生、原位癌、浸润癌、转移癌等阶段。

不典型增生和原位癌可以完全治愈。

食管鳞状上皮不典型增生是食管癌的重要癌前病变,由不典型增生到癌变一般需要几年甚至十几年。

食管浸润癌又称进展期癌,约近半的患者可以治愈,但到了转移癌治愈的可能性较小,一般只能控制下病情,因此,食管癌重在早期诊断。

那么食管癌是怎样检查出来的?1、食管脱落细胞学检查对于食管癌疾病的检查,最为常见的检查方法就是食管脱落细胞学检查,因为这种方法不仅简便,受检者痛苦小,是食管癌早期诊断的首选方法。

2、X线钡餐造影X线钡餐造影也是检查此病常见方法,该方法大多能发现食管黏膜增粗、迂曲或虚线状中断;或食管边缘发毛;或小的充盈缺损;或小的龛影;或局限性管壁发僵;或有钡滞留等较早癌征象。

3、纤维内窥镜检查临床上对于食管癌的检查还可通过纤维内窥镜进行检查,这种检查在早期食管癌中,纤维内窥镜的检出率可达85%以上。

4、食管内镜超声检查检查食管癌必然要检查患者的食管,所以食管内镜超声检查也是检查此病的一种,可比较精确测定病变在食管壁内浸润的深度;可测量出壁外异常肿大淋巴结;可以较容易地区别病变在食管壁部位。

5、食管脱落细胞学检查是食管癌诊断常用的方法之一,脱落细胞学检查方法比较简便,患者痛苦小,误诊率低,有高血压、食管静脉曲张、严重心脏病以及肺部疾病的患者为该检查方法的禁忌证。

6、食管癌的CT扫描检查CT扫描可以清晰显示食管与邻近纵隔器官的关系,但难以发现早期食管癌。

CT不能鉴别正常体积的淋巴结有无转移,无法肯定肿大淋巴结是由于炎症或转移引起,更无法发现直径小于1cm的转移淋巴结,将CT与X线检查相结合,有助于食管癌的诊断和分期水平的提高。

食管癌分期学习笔记6-7-8

一、2002年第6版第6版分段:根据肿瘤中心位置确定(内镜或C T)距门齿15-18-24-32-40;环状软骨下缘-胸骨切迹-气管分叉-1/2-贲门2002年第6版T N M分期(并未考虑肿瘤类型、细胞分化程度)I期T1N0M0I I A期T2、3N0M0I I B期T1、2N1M0I I I期T3N1M0,T4N0、1M0I V A期T N M1aI V B期T N M1b第6版区域淋巴结定义1.食管淋巴引流:集中在粘膜下与肌层间的淋巴管网上行收集胸上段、颈段,进入食管旁、锁骨上、颈深淋巴结下行手机胸中、下段,进入贲门、胃左动脉旁淋巴结其余大部分进入气管、食管旁落淋巴结此外每部分都可向反方向引流2.颈段包括颈部淋巴结锁骨上淋巴结,胸段包括纵隔淋巴结和胃周淋巴结,不包括腹主动脉旁淋巴结胸上段胸中段胸下段颈部L N14.6%4.3%2.0%上纵隔L N29.3%5.0%2.2%中纵隔L N8.5%32.9%15.4%下纵隔L N9.8%2.5%38.1%腹腔L N7.3%14.9%27.5%3.早期一个日本研究,仅有区域性淋巴结转移到1211例患者5年16.8%,非区域的5年5.2%,因此非区域归为M1二、2010年第7版第7版分段:距门齿15-20-25-30-齿状线以肿瘤上缘所在的食管位置决定,以上切牙到肿瘤上缘的距离来表示具体位置:(1)颈段食管:上接下咽,向下至胸骨切迹平面的胸廓入口,前邻气管、两侧与颈血管鞘毗邻,后面是颈椎,内镜检查距门齿15厘米至<20厘米。

(2)胸上段食管:上自胸廓入口,下至奇静脉弓下缘水平,其前方由气管、主动脉弓及分支和大静脉包绕,后面为胸椎。

内镜检查距门齿20厘米至<25厘米。

(3)胸中段食管:上自奇静脉弓下缘,下至下肺静脉水平,前方是两个肺门之间结构,左邻胸降主动脉,右侧是胸膜,后方为胸椎。

内镜检查距门齿25厘米至<30厘米。

(4)胸下段食管及食管胃交界:上自下肺静脉水平,向下终于胃,由于这是食管的末节,故包括了食管胃交界(E s o p h a g o g a s t r i c J u n c t i o n,E G J)。

食管癌

扩散

食管癌侵及全层食管壁后,常直接 侵犯邻近器官组织。上段食管癌可 侵入喉、气管、喉返神经;中段食 管癌可侵入支气管、胸膜、肺组织、 主动脉、脊柱、胸导管和奇静脉; 下段食管和贲门癌可侵入隔肌、心 包、胃、胰腺尾部和肝脏左叶。

淋巴道转移

食管癌淋巴道转移较常见,且发生较 早。上段食管癌常转移到气管旁和颈 部淋巴结;中段食管癌最常转移到食 管旁、肺门和隆凸下淋巴结,但亦可 向上转移到颈部淋巴结,向下转移到 贲门旁、胃左动脉旁和主动脉前淋巴 结;下段食管癌则常转移到食管旁和 隔肌下方淋巴结,有时亦可向上转移 到隆凸下,气管旁、肺门和颈部淋巴 结。

(二)中、晚期症状 1.吞咽困难:进行性吞咽困难 1.吞咽困难:进行性吞咽困难 是食管癌的典型症状。初起时进食 固体食物有梗噎感,以后逐渐呈进 行性加重,甚至流质饮食亦不能咽 下。吞咽困难的严重程度除与病期 有关外,与肿瘤的类型亦有关系。 缩窄型出现梗阻症状早而严重,溃 疡型及腔内型出现梗阻症状较晚。

4.体重下降及恶病质:因长期吞 4.体重下降及恶病质:因长期吞 咽困难,引起营养障碍,体重 明显下降,消瘦明显。出现恶 液质是肿瘤晚期的表现。 5.邻近器官受累的症状:肿瘤侵 5.邻近器官受累的症状:肿瘤侵 及邻近器官可引起相应的症状。 声嘶、食管气管瘘、Horner综 声嘶、食管气管瘘、Horner综 合征。

放射治疗:应用60钴治疗机和 放射治疗:应用60钴治疗机和

加速器治疗食管癌,可缓解症 状,延长生存期,少数病人可 望得到根治。对于中晚期食管 癌病人可术前给予短期放射治 疗,剂量约为30Gy(3000rad), 疗,剂量约为30Gy(3000rad), 照射后2 照射后2-3周左右施行手术治疗。

未能彻底切除者应于手术时在 癌变区放置金属标志,术后3 癌变区放置金属标志,术后3-6 周进行放射治疗。食管癌病变 比较局限但因已呈现颈部淋巴 结转移或因全身情况不宜施行 外科手术者亦可作姑息性放射 治疗,以减轻临床症状延长生 命。

胃癌和食管癌的病理形态学比较

胃癌和食管癌的病理形态学比较概述胃癌和食管癌是常见的消化系统恶性肿瘤,在临床上具有很高的发病率和死亡率。

它们的病理形态学特征对于诊断和治疗具有重要意义。

本文将对胃癌和食管癌的病理形态学进行比较,旨在深入了解这两种恶性肿瘤的异同之处。

胃癌的病理形态学特征胃癌是胃黏膜上皮恶性肿瘤,可分为腺癌、鳞癌和其他类型。

腺癌是最常见的胃癌类型,占胃癌患者约95%。

以下是胃腺癌的病理形态学特征:1.组织结构变异:胃腺癌的病理组织学表现包括腺管结构紊乱、乳头状生长和实性细胞聚集等。

有些腺癌形成了鳞状细胞团,而其他则形成了腺管结构。

2.细胞多样性:胃腺癌细胞呈现不同的形态,包括多形性细胞、多核细胞和异型细胞。

细胞变异性的出现是胃癌诊断的重要依据之一。

3.浸润性生长:胃腺癌具有浸润性生长的特点。

癌细胞可以通过破坏胃壁的黏膜层和肌层,向深部浸润,最终侵入邻近组织和器官。

4.黏液分泌:胃腺癌细胞常表现出黏液分泌增多的特点,形成黏液腺癌。

黏液的积聚影响了胃腺癌的发展和扩散。

5.核分裂指数升高:胃腺癌细胞的核分裂指数常明显升高,显示癌细胞的活跃增殖状态。

食管癌的病理形态学特征食管癌是食管黏膜上皮恶性肿瘤,主要分为腺癌和鳞癌两类。

以下是食管癌的病理形态学特征:1.组织结构变异:食管癌的病理组织学表现多样。

鳞癌呈现为不规则鳞状上皮增生,形成饼状坏死。

而腺癌则形成腺管结构,并可伴有黏液产生。

2.细胞多样性:食管癌细胞呈现不同的形态,包括多形性细胞、多核细胞和异型细胞。

细胞间质破坏和核分裂活跃是食管癌的典型特征。

3.浸润性生长:食管癌具有浸润性生长的特点。

癌细胞可以侵犯食管黏膜层和肌层,进一步侵蚀邻近组织和器官。

4.淋巴结转移:食管癌常有淋巴结转移的倾向,这是食管癌预后较差的重要原因之一。

5.黏液分泌:部分食管癌细胞可以合成和分泌大量的黏液,形成黏液癌。

黏液的积聚不仅影响了食管癌的发展,还会导致食管腔狭窄或阻塞。

胃癌和食管癌的比较虽然胃癌和食管癌都是消化系统的恶性肿瘤,但它们在病理形态学上存在一些差异:1.发生部位不同:胃癌发生在胃黏膜上皮,而食管癌发生在食管黏膜上皮。

如何早发现食道癌?出现这4大症状,要及时到医院做筛查

如何早发现⾷道癌?出现这4⼤症状,要及时到医院做筛查⾷道癌是发⽣在⾷道的癌症,与不规律的饮⾷密切相关。

由于⼯作或学习,尤其是年轻⼈,⼈们可能没有意识到,当压⼒增⼤时,他们的饮⾷习惯变得极不规律,在⾷物选择上存在问题。

这样⼀来,对⾷道的危害就⼀步⼀步加深,导致⾷道癌。

导致⾷道癌发⽣的饮⾷习惯是什么?1.过多⾷⽤腌⾁腌⾁含有⼤量亚硝酸盐。

过量⾷⽤会对⾝体造成极⼤伤害,进⽽增加患⾷道癌的⼏率。

腌⾁如腌鸭和腌排⾻,因为有些⼈喜欢这种味道,他们会吃得太多。

2.长时间吃泡菜泡菜配⽶饭和⾯条很好吃,但在满⾜⼝味的同时,也会对⾝体造成伤害。

泡菜含有过多的亚硝酸盐。

⼈体摄⼊过量亚硝酸盐会导致⾷道癌。

因此,我们应该少吃泡菜。

3.经常吃太热的⾷物有些⼈喜欢吃辣的⾷物,有些⼈因为⼯作原因吃太多热的⾷物。

从长远来看,热的⾷物对⾷道来说是⽆法忍受的,因为它的温度会损害⾷道和消化道粘膜,导致炎症症状。

随着时间的推移,反复刺激可能会导致⾷管癌。

4.经常抽烟喝酒吸烟和饮酒会给⼈的⾝体带来极⼤的伤害,因为酒精具有刺激性。

长期⼤量饮酒会严重刺激肠胃,进⽽导致⾷道癌。

吸烟是⼀个⼤家常说的坏习惯,因为烟中含有更多有害物质,有时⾼温会伤害⾷道。

此外,有害化学物质将⼤⼤提⾼患⾷道癌的⼏率。

5.饮⾷过于⾟辣有些⼈喜欢吃⾟辣⾷物,长时间吃太多辣椒⾷物容易引起严重的胃肠不适。

最简单的表现是腹泻和腹痛,随着时间的推移可能会导致⾷管癌。

⾟辣饮⾷可以偶尔⾷⽤,也可以以清淡饮⾷为主。

6.长期⽤药这种药本⾝有⼀定的副作⽤,有些⼈由于⾝体原因不得不长期服药。

吞咽后,药物通常会进⼊⾷道,因此从长远来看可能会损害⾷道。

⾷管癌与不健康的饮⾷密切相关,我们必须注意⽇常⽣活中的饮⾷习惯问题。

我们不应该吃那些不健康的⾷物,养成良好的⽣活习惯。

我们应该尽可能远离烟草和酒精,以减少⾷道癌的发病率。

食道癌

12

食管癌的分期决定治疗手段 :

早期 :手术切除仍是治愈的首选治疗

局部进展期:手术、放疗、化疗联合 是公认的治疗手段

13

局部进展期食管癌

有手术可能 无手术可能 新辅助放化疗 化、放疗联合 手术

14

晚期食管癌:

全身化疗加局部放疗缓解症状,改善存 质量是标准的治疗手段。

15

食管癌常用化疗方案:

奥沙利铂+卡培他滨 紫杉醇+铂类。

16

奥沙利铂:

常用于转移性结直肠癌治疗,或辅助治疗原发性肿瘤完全切除后三 期(Dukes C)结肠癌。

奥沙利铂的剂量限制性毒性反应是神经系统毒性反应。主要表现在 外周感觉神经病变,表现为肢体末端感觉障碍或/和感觉异常。伴或 不伴有痛性痉挛,通常遇冷会激发。这些症状在接受治疗的病人中 的发生率为95%。在治疗间歇期,症状通常会减轻,但随着治疗周期 的增加,症状也会逐渐加重。 注意事项:不能与氯化钠混用。

9

组织学分型

鳞状细胞癌:最多见。

腺癌:较少见,又可分为单纯腺癌、腺鳞癌、粘 液表皮样癌和腺样囊性癌 未分化癌:较少见,但恶性程度高。

10

食道癌的X 线检查

食管钡餐检查 食管CT 检查

11

食管癌的治疗

1、放射治疗:是局部治疗,通过放射能对癌肿部 位进行照射。 2、化学治疗:是全身性治疗,单纯化疗的有效率 不高,因此化疗只能作为食管癌的辅助治疗手段。 3、外科治疗:切除癌肿并彻底清扫纵隔内淋巴结 是外科治疗的主要方法。食管切除后用胃、结肠 或空肠代替,重建食管,使病人能恢复经口进食。

21

【护理诊断】

疼痛: 上腹痛 与癌细胞侵入食管有关。 焦虑: 与健康状况改变,病情危重有关。 营养失调: 低于机体需要量 与食欲减退、能量消耗增 加有关。 活动无耐力:与疼痛 、体质弱有关

食管癌健康宣教内容

食管癌健康宣教内容1. 什么是食管癌食管癌是一种恶性肿瘤,起源于食管内上皮细胞的异常增生。

它主要发生在食管中下段,多数为鳞状细胞癌。

食管癌具有隐匿性、发展快速等特点,早期症状不明显,易被忽视。

2. 食管癌的危险因素•吸烟和酗酒:长期吸烟和大量饮酒会增加患食管癌的风险。

•饮食习惯:高盐、高脂、低纤维的饮食习惯与食管癌有关。

•营养不良:缺乏维生素A、维生素C和蛋白质等营养物质会增加患食管癌的危险。

•高温饮食:长期摄入过热的食物和液体可能损伤食管黏膜,增加患癌的可能性。

3. 食管癌的早期症状•吞咽困难:食物卡在胸骨后或喉咙处,吞咽时感觉有阻塞感。

•进食疼痛:进食时感到胸部或上腹部疼痛。

•消瘦乏力:体重明显下降,乏力感加重。

•反酸、胃灼热:出现胃酸倒流的症状,常伴有灼热感。

•呕血或黑便:出现呕血或黑便是食管癌晚期的常见表现。

4. 食管癌的预防和早期筛查•戒烟限酒:戒烟和限制饮酒可以有效降低患食管癌的风险。

•合理饮食:保持均衡营养,多摄入富含维生素和纤维的蔬菜水果,减少盐、油和高温食物的摄入。

•定期体检:定期到医院进行全面体检,包括内镜检查等来筛查早期食管癌。

5. 食管癌的治疗方法•手术切除:对于早期的食管癌,可以通过手术切除来治疗。

•化疗和放疗:对于晚期的食管癌,常常采用化疗和放疗来减轻症状、延长生存时间。

•靶向治疗:靶向药物针对特定的癌细胞分子靶点进行治疗,可以提高治疗效果。

6. 食管癌患者的护理与康复•营养支持:合理调整饮食结构,提供高蛋白、高维生素的饮食,保证患者营养需求。

•定期复查:定期到医院进行复查,以便及时发现和处理任何异常情况。

•心理支持:提供情感上的关怀和支持,帮助患者积极面对治疗过程中的困难和挑战。

7. 食管癌康复注意事项•戒烟限酒:避免吸烟和大量饮酒,以减少二次发生食管癌的风险。

•均衡饮食:保持健康的饮食习惯,摄入适量的蛋白质、维生素和纤维。

•定期运动:适度的运动有助于提高身体免疫力和促进康复。

食管癌

转移,无手术禁忌症者应首先考虑手术治疗。

➢ห้องสมุดไป่ตู้(二)手术禁忌症:

⑴已发现远处转移者。 ⑵全身情况不能经受手术者。

食管癌--治疗原则

➢(三)手术种类

1.根治性切除:食管癌比较局限,可以切除瘤体及 其所属引流淋巴结,以胃、结肠或空肠做食管重 建术。 2.姑息性切除术:食管癌已属晚期,与周围器官粘 着较深或已有广泛淋巴结转移,虽然瘤体可以切 除,但周围浸润及转移淋巴结往往不能彻底切除。 3.减状性手术:为了解决进食而施行的食管腔内置 管术,食管胃转流吻合术,食管结肠转流吻合术 或胃造瘘术等。

食管癌--健康指导

健康指导 ➢保持良好的心理状态 ➢进行适当活动 ➢进食由少到多,避免刺激性食物,避免进食过快、

过量、过热、过硬。

➢注意口腔卫生,做呼吸,有效咳嗽和排痰。 ➢定期复查,坚持继续治疗,如放、化疗。

LOGO

➢处理:可根据瘘口的大小,部位及病情而定,颈

部吻合口瘘可切开引流。胸内可采用闭式引流, 吻合口瘘修补术,有些病人需要再次行吻合术或 结肠移植术,重建消化道。在吻合口愈合之前, 病人应禁食,保持有效肠胃减压,加强抗感染治 疗及静脉营养支持,严密观察生命体征及胸部情 况。

食管癌--护理

(二)乳糜胸:食管、贲门癌术后并发乳糜胸是比 较严重的并发症,多因伤及胸导管所致,乳糜胸 多发生在术后2-10d,有些在术后24h可表现。

接观察病变部位、范围、形态并可采取活体组织 病理学检查。

➢超声内镜:可以精确测定癌肿在食管壁内的侵润

深度,对原发肿瘤的分析较准确。

食管癌

1 病因

2 病理

目

3 临床表现

录

4 检查

食管癌上中下段划分标准

食管癌上中下段划分标准

食管癌的上、中、下段划分标准如下:

1. 颈段食管:上至下咽,下至胸廓入口,及胸骨上切迹水平,在内镜下测量通常距离门齿约15\~20cm。

2. 胸段食管:又分为胸上段食管、胸中段食管和胸下段食管。

胸上段食管:从胸廓入口开始,下至奇静脉弓下缘水平,内镜下测量,距离门齿的距离约20\~25cm。

胸中段食管:从奇静脉弓下缘开始,下至下肺静脉下缘,内镜下测量,通常距门齿为25\~30cm。

胸下段食管:上至下肺静脉下缘,下至食管结合部,内镜下测量距门齿约30\~40cm。

3. 胃食管交界部:胸下段食管以下称为胃食管交界部,通常腹部食管也包括在内,内镜下测量距门齿大概40\~42cm。

食管癌划分上、中、下段时,与肿瘤大小、长度密切相关,通常以肿瘤长度的中点所在的位置决定食管癌所在的位段。

根据食管癌的位置,可以选择不同的手术方式,以取得更好的治疗效果。

以上信息仅供参考,如果您有任何疑虑或不适,建议及时就医并咨询专业医生。

食道癌的早期症状

食道癌的早期症状概述食管癌是常见的消化道肿瘤,全世界每年约有30万人死于食管癌。

其发病率和死亡率各国差异很大。

我国是世界上食管癌高发地区之一,每年平均病死约15万人。

男多于女,发病年龄多在40岁以上。

食管癌典型的症状为进行性咽下困难,先是难咽干的食物,继而是半流质食物,最后水和唾液也不能咽下。

症状典型症状1.早期症状常不明显,但在吞咽粗硬食物时可能有不同程度的不适感觉,包括咽下食物梗噎感,胸骨后烧灼样、针刺样或牵拉摩擦样疼痛。

食物通过缓慢,并有停滞感或异物感。

梗噎停滞感常通过吞咽水后缓解消失。

症状时轻时重,进展缓慢。

2.中晚期食管癌典型的症状为进行性咽下困难,先是难咽干的食物,继而是半流质食物,最后水和唾液也不能咽下。

常吐黏液样痰,为下咽的唾液和食管的分泌物。

患者逐渐消瘦、脱水、无力。

持续胸痛或背痛表示为晚期症状,癌已侵犯食管外组织。

当癌肿梗阻所引起的炎症水肿暂时消退,或部分癌肿脱落后,梗阻症状可暂时减轻,常误认为病情好转。

其他症状若癌肿侵犯喉返神经,可出现声音嘶哑;若压迫颈交感神经节,可产生Horner 综合征;若侵入气管、支气管,可形成食管、气管或支气管瘘,出现吞咽水或食物时剧烈呛咳,并发生呼吸系统感染。

最后出现恶病质状态。

若有肝、脑等脏器转移,可出现黄疸、腹腔积液、昏迷等状态。

诊断依据1.食管钡餐X线片可见食管狭窄,壁管不光滑,黏膜破坏。

2.CT主要了解肿瘤外侵(纵壁)程度,确定纵壁是否有转移病变。

3.纤维胃镜或者食管镜检查可见到食管内黏膜破坏、溃疡、有菜花状新生物。

4.细胞学检查。

5.组织学检查。

病因食管癌的人群分布与年龄、性别、职业、种族、地域、生活环境、饮食生活习惯、遗传易感性等有一定关系。

经已有调查资料显示食管癌可能是多种因素所致的疾病。

已提出的病因如下:1.化学病因亚硝胺。

这类化合物及其前体分布很广,可在体内、外形成,致癌性强。

在高发区的膳食、饮水、酸菜、甚至病人的唾液中,测亚硝酸盐含量均远较低发区为高。

食管癌 肿瘤位置 标准

食管癌肿瘤位置标准

食管癌的肿瘤位置标准如下:

按照UICC/AJCC和世界卫生组织(WHO)国际疾病-肿瘤编码的食管病变分段标准(UICC,2002):

1. 颈段食管:自食管入口或环状软骨下缘起至胸骨柄上缘平面,其下界距上门齿约18cm。

2. 胸上段食管:自胸骨柄上缘平面至气管分权平面,其下界距门齿约24cm。

3. 胸中段食管:自气管分权平面至食管胃交接部(贲门口)全长的上半,其下界距门齿约32cm。

4. 胸下段食管:自气管分权平面至食管胃交接部(贲门口)全长的下半,其下界距门齿约40cm。

5. 胸下段也包括食管腹段。

此外,食管癌的发病部位在食管壁上,长度为35到45厘米,无论食管哪

个部位出现癌细胞,都属于食管癌。

以上内容仅供参考,具体诊断和治疗建议请遵循医生的指导。

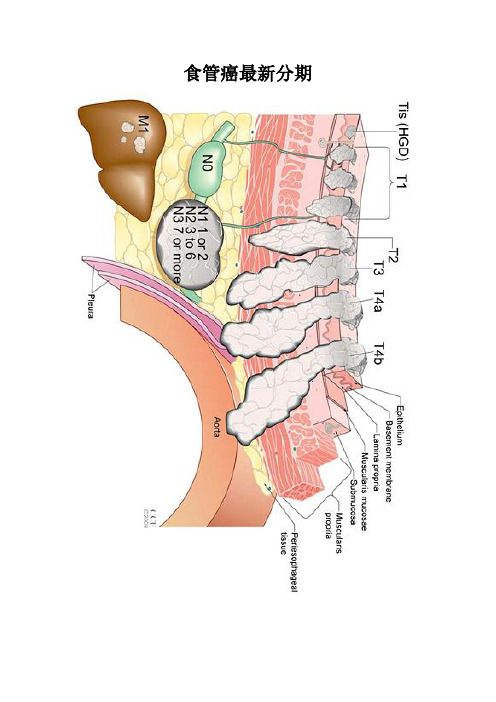

食管癌最新分期

食管癌最新分期

新版食管癌T、N、M、G定义

TX:原发肿瘤不能确定;

•T0:无原发肿瘤证据;

•Tis:重度不典型增生(HGD);

•T1:肿瘤侵犯粘膜固有层、粘膜肌层或粘膜下层;

–T1a:肿瘤侵犯粘膜固有层或粘膜肌层;

–T1b:肿瘤侵犯粘膜下层;

•T2:肿瘤侵犯食管肌层;

•T3:肿瘤侵犯食管纤维膜;

•T4:肿瘤侵犯食管邻近器官;

–T4a:肿瘤侵犯胸膜、心包、或膈肌(根治切除);

–T4b:肿瘤侵犯其他器官如主动脉、椎体、气官等(姑息切除)•NX:区域淋巴结转移不能确定;

•N0:无区域淋巴结转移证据;N1:1-2枚淋巴结转移;

•N2:3-6枚淋巴结转移;N3: 7枚淋巴结转移;

•M0:无远处转移;M1:有远处转移。

•GX:分化程度不能确定,按G1分组;

•G1:高分化癌;G2:中分化癌;G3:低分化癌;

•G4:未分化癌,按G3分组。

食道癌都有哪些症状

食道癌都有哪些症状食道癌都有哪些症状呢?下面就由专家来一一讲述:食道癌早期症状1.胸骨后和剑突下疼痛较多见。

咽下食物时有胸骨后或剑突下痛,其性质可呈烧灼样、针刺样或牵拉样,以咽下粗糙、灼热或有刺激性食物为著。

初时呈间歇性,当癌肿侵及附近组织或有穿透时,就可有剧烈而持续的疼痛。

疼痛部位常不完全与食管内病变部位一致。

疼痛多可被解痉剂暂时缓解。

2.食物滞留感染和异物感咽下食物或饮水时,有食物下行缓慢并滞留的感觉,以及胸骨后紧缩感或食物粘附于食管壁等感觉,食毕消失。

症状发生的部位多与食管内病变部位一致。

3.咽喉部干燥和紧缩感咽下干燥粗糙食物尤为明显,此症状的发生也常与病人的情绪波动有关。

4.咽下梗噎感最多见,可自选消失和复发,不影响进食。

常在病人情绪波动时发生,故易被误认为功能性症状。

5.其他症状少数病人可有胸骨后闷胀不适、前痛和喛气等症状。

食道癌中期症状1.胸骨后和剑突下疼痛较多见。

咽下食物时有胸骨后或剑突下痛,其性质可呈烧灼样、针刺样或牵拉样,以咽下粗糙、灼热或有刺激性食物为著。

初时呈间歇性,当癌肿侵及附近组织或有穿透时,就可有剧烈而持续的疼痛。

疼痛部位常不完全与食管内病变部位一致。

疼痛多可被解痉剂暂时缓解。

2.食物滞留感染和异物感咽下食物或饮水时,有食物下行缓慢并滞留的感觉,以及胸骨后紧缩感或食物粘附于食管壁等感觉,食毕消失。

症状发生的部位多与食管内病变部位一致。

3.咽喉部干燥和紧缩感咽下干燥粗糙食物尤为明显,此症状的发生也常与病人的情绪波动有关。

4.咽下梗噎感最多见,可自选消失和复发,不影响进食。

常在病人情绪波动时发生,故易被误认为功能性症状。

5.其他症状少数病人可有胸骨后闷胀不适、前痛和喛气等症状。

中期食道癌的典型症状:进行性吞咽困难.可有吞咽时胸骨后疼痛和吐黏液样痰。

食道癌的晚期症状1.食物反应常在咽下困难加重时出现,反流量不大,内含食物与粘液,也可含血液与脓液。

2.其他症状当癌肿压迫喉返神经可致声音嘶哑;侵犯膈神经可引起呃逆或膈神经麻痹;压迫气管或支气管可出现气急和干咳;侵蚀主动脉则可产生致命性出血。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

Lancet Oncol 2011; 12: 681–92Published Online June 17, 2011DOI:10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70142-5See Comment page 615National Health and Medical Research Council Clinical Trials Centre, University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW, Australia (K M Sjoquist FRACP, Prof R J Simes MD,Prof V Gebski MStat); Division of Cancer Services, University of Queensland, PrincessAlexandra Hospital, Brisbane, QLD, Australia(Prof B H Burmeister MD); Department of Surgery, University of Queensland, Brisbane, QLD, Australia (Prof B M Smithers FRACS, A Barbour FRACS); Upper Gastrointestinal and SoftTissue Unit, Princess Alexandra Hospital, Brisbane, QLD, Australia (B M Smithers, A Barbour); and PeterMacCallum Cancer Centre, and Department of Medicine, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, VIC, Australia (Prof J R Zalcberg FRACP)Correspondence to:Prof Val Gebski, National Healthand Medical Research Council Clinical Trials Centre, LockedBag 77, Camperdown 1450 NSW, Australiaval@.auSurvival after neoadjuvant chemotherapy orchemoradiotherapy for resectable oesophageal carcinoma: an updated meta-analysisKatrin M Sjoquist, Bryan H Burmeister, B Mark Smithers, John R Zalcberg, R John Simes, Andrew Barbour, Val Gebski, for the Australasian Gastro-Intestinal Trials GroupSummaryBackground In a previous meta-analysis, we identifi ed a survival benefi t from neoadjuvant chemotherapy or chemoradiotherapy before surgery in patients with resectable oesophageal carcinoma. We updated this meta-analysis with results from new or updated randomised trials presented in the past 3 years. We also compared the benefi ts of preoperative neoadjuvant chemotherapy compared with neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy.Methods To identify additional studies and published abstracts from major scientifi c meetings, we searched Medline, Embase, and Central (Cochrane clinical trials database) for studies published since January, 2006, and also manually searched for abstracts from major conferences from the same period. Only randomised studies analysed by intention to treat were included, and searches were restricted to those databases citing articles in English. We used published hazard ratios (HRs) if available or estimates from other survival data. We also investigated treatment eff ects by tumour histology and relations between risk (survival after surgery alone) and eff ect size.Findings We included all 17 trials from the previous meta-analysis and seven further studies . 12 were randomised comparisons of neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy versus surgery alone (n=1854), nine were randomised comparisons of neoadjuvant chemotherapy versus surgery alone (n=1981),and two compared neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy with neoadjuvant chemotherapy (n=194) in patients with resectable oesophageal carcinoma; one factorial trial included two comparisons and was included in analyses of both neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy (n=78) and neoadjuvant chemotherapy (n=81). The updated analysis contained 4188 patients whereas the previous publication included 2933 patients. This updated meta-analysis contains about 3500 events compared with about 2230 in the previous meta-analysis (estimated 57% increase). The HR for all-cause mortality for neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy was 0·78 (95% CI 0·70–0·88; p<0·0001); the HR for squamous-cell carcinoma only was 0·80 (0·68–0·93; p=0·004) and for adenocarcinoma only was 0·75 (0·59–0·95; p=0·02). The HR for all-cause mortality for neoadjuvant chemotherapy was 0·87 (0·79–0·96; p=0·005); the HR for squamous-cell carcinoma only was 0·92 (0·81–1·04; p=0·18) and for adenocarcinoma only was 0·83 (0·71–0·95; p=0·01). The HR for the overall indirect comparison of all-cause mortality for neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy versus neoadjuvant chemotherapy was 0·88 (0·76–1·01; p=0·07).Interpretation This updated meta-analysis provides strong evidence for a survival benefi t of neoadjuvantchemoradiotherapy or chemotherapy over surgery alone in patients with oesophageal carcinoma. A clear advantage of neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy over neoadjuvant chemotherapy has not been established. These results should help inform decisions about patient management and design of future trials.Funding Cancer Australia and the NSW Cancer Institute.IntroductionOverall survival of patients with resectable oesophagealcancer remains poor, with a 5-year survival of 15–34%,1 despite changes in management over the past 20 years. Most patients who undergo radical resection for oesophageal cancer will eventually relapse and die as a result of their disease.2 Because of diffi culties in administering chemotherapy or radiotherapy soon after a surgical procedure, high perioperative morbidity, and the disappointing results of trials of adjuvant chemotherapy,3 radiotherapy,4,5 or combination chemoradiotherapy,2 the focus of recent trials has been on neoadjuvant treatment. In our previous meta-analysis,6 we reported a signifi cant survival benefi t for neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy and,to a lesser extent, neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with squamous-cell carcinoma or adenocarcinoma of the oesophagus. At present, there is no evidence supporting the use of neoadjuvant radiotherapy alone.4Most trials of chemotherapy or combined chemo-radiotherapy have used a doublet of cytotoxics, usually a platinum compound, most often cisplatin, and fl uorouracil,1,7–22 with varying doses and sequencing. Some small trials of neoadjuvant chemotherapy have used triplet chemotherapy, which resulted in increased toxicity without signifi cant survival benefi ts.23,24 Recent treatment modifi cations have included the use of more modern cytotoxic drugs, changes in chemotherapy sequencing, or changes in the dose and fractionation of radiotherapy.2We aimed to assess whether the results of recently published or updated trials have changed the outcomes of our previous meta-analysis.6 We also sought to compare the benefi ts of neoadjuvant chemotherapy and neo-adjuvant chemoradiotherapy before surgery for resectable oesophageal carcinoma, and to assess whether any increase in survival benefi ts was off set by an increase in perioperative mortality.MethodsFor the fi rst section of the meta-analysis, we sought to assess the survival benefi ts of neoadjuvant treatment with either neoadjuvant chemotherapy or neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy of any regimen. All randomised controlled trials that compared survival after neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy or neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by surgery with surgery alone in the initial management of resectable oesophageal or oesophago g astric junction carcinoma (squamous-cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, or mixed tumours) were eligible for inclusion, provided they were analysed by intention-to-treat.We included all trials from our previous meta-analysis.6 We searched Medline, Embase, and Central (Cochrane clinical trials database) for studies published since January, 2006. We used the following search terms: “esophageal neoplasms”, “gastro-esophageal junction neoplasms”, “antineoplastic agents”, ”chemotherapy”, “radiotherapy”, “surgery”, and “esophagectomy or gastrectomy”. We also manually searched for abstracts from major conferences over the same period. Articles for which neither the abstract nor full text was available in English were excluded after review. We also included studies in an analysis of histological subtypes if subgroupdata could be identified separately, with the same criteria for inclusion as described in the previous meta-analysis.6The primary outcome of interest for the fi rst section of the meta-analysis was all-cause mortality. The secondary endpoint was the eff ect on all-cause mortality of treatment for each histological subtype (squamous-cell carcinoma or adenocarcinoma).For the second section of the meta-analysis, we sought to assess the survival benefi ts of neoadjuvant chemo-therapy compared with neoadjuvant chemoradio t herapy. All randomised trials of this comparison that included adult patients with squamous-cell carcinoma, adeno-carcinoma, or mixed tumours were eligible. We did not identify any previous systematic reviews or meta-analysesof suffi cient quality, and so we searched Medline, Embase, and Central with the same terms as for the fi rst section. All trials published between January, 1980 and November, 2010, were included if the abstract or fullarticle was available in English.For both sections of the meta-analysis, we wrote toauthors of studies that had previously only appeared asabstracts and were not in the databases to clarify whether updated data had been published, including the authors of four studies that were excluded from the previous meta-analysis.25–28 Trials that focused on primary gastric cancers were excluded if the results for oesophagogastric junction tumours were not available separately.Statistical analysesFor the fi rst section of the meta-analysis, we used the same statistical methods as previously reported.6 We used the hazard ratio (HR) for the comparison in each trial to assess the treatment eff ects. Where possible, the HR and associated variance were obtained directly from each trial publication or from individual patient data. HRs not reported were calculated by the methods of Parmar and colleagues.29 Statistical tests were two-sided. Pooled estimates with 95% CIs were calculated by the weighted variance technique and we used the χ² test to assess heterogeneity, with the level of signifi cance set at 5%. We assessed publication bias by the methods described by G leser and Olkin,30 and we used Fisher’s failsafe N 31 to identify the number of studies with a p value of 0·5 (ie, an HR of 1·0) that would need to be added to those in the meta-analysis to produce a non-signifi cant result.Figure 1: Flow diagram showing inclusion and exclusion of studies*Includes 17 studies that were included in this meta-analysis and fi ve studies that could not be included. †Includes abstracts that reported earlier results where full papers were subsequently published and multiple abstracts that reported the results of the same study. ‡See webappendix p 1 for reference.See Online for webappendixWe calculated the overall 2-year survival estimate in the control group from a mean of individual 2-year survival rates weighted by the sample size of the control group. The estimate of the 2-year survival rate in the intervention was obtained by applying the HR to the estimated control rate. We then used these data to calculate the absolute risk reduction and number needed to treat.Because the individual trials could be deemed independent of each other, we used indirect comparisonsto obtain estimates of the benefi t of neoadjuvant chemo-radiotherapy compared with neoadjuvant chemo t herapy. Potential biases might occur in such comparisons, thus the amount to which the results of the indirect comparisons corroborate those of the randomised studies is also of interest. We assessed this by comparing diff erences between the eff ects obtained from the direct and indirect comparisons. Consistency between eff ects for indirect and direct comparisons provides confi dence about the additional information in the indirect comparisons. These approaches were described by Song and colleagues,32as was the comparison of the amount of discrepancy between the indirect comparisons and those of the randomised trials; a p value of greater than 0·05 would suggest that the results for the indirect and direct comparisons are statistically consistent. Data were analysed with software provided by the Cochrane Library (Rev Man 4.3, and 5.0 downloaded April, 2010). Diff erences between outcomes in the control arms of the diff erent trials were measured against the logarithm of the HR to give an estimate of the relation between risk and benefi t of neoadjuvant chemotherapy or neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy. The number of events (deaths) used was estimated from the sample size and median follow-up time reported for each trial and an assumption that about 50% of events had occurred within 18 months.We also did prespecified subgroup analyses to examine the effects of neoadjuvant chemotherapy or neo a djuvant chemoradiotherapy according to tumour histology (squamous-cell carcinoma or adenocarcinoma) where this information was available.Differences between treatment arms for 30-day postoperative or in-hospital mortality were calculated from the absolute diff erence in the proportion of deaths, with 95% CIs.Role of the funding sourceThe sponsor of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, writing of this report, or the decision to publish the results. KS and VG had full access to all of the data in the study and had the final responsibility, with the agreement of all authors, for the decision to submit for publication.ResultsWe included 24 studies in total (fi gure 1),1,7–15,17–24,37,39–43 which consisted of all 17 trials from the previous meta-analysis8–10,12–14,16,17,19–24,38,39,40 and seven further studies.7,11,15,18,37,41,42 12 were randomised comparisons of neo a djuvant chemo r adio t herapy versus surgery alone (n=1854),10–14,17,22,39–43 nine were randomised comparisons of neoadjuvant chemotherapy versus surgery alone (n=1981),1,7,8,19–21,23,24,37 two compared neoadjuvant chemo-radiotherapy with neoadjuvant chemotherapy (n=194),15,18 and one study included two comparisons and was included in analyses of both neoadjuvant chemo-radiotherapy (n=78) and neoadjuvant chemo t herapy (n=81).9 This study was a 2 × 2 factorial study that simultaneously compared the effect of neoadjuvant chemo t herapy, neoadjuvant chemo r adio t herapy, and neoadjuvant radiotherapy on survival, and the control group was used for both the neoadjuvant chemotherapy and neoadjuvant chemo r adiotherapy comparisons. Accordingly, half the sample size for the control group was reported in each of the comparisons. The HR for the comparison of neoadjuvant chemotherapy with surgery alone in this study was used as calculated for the previous meta-analysis.6The updated analysis contained 4188patients whereas the previous publication included 2933 patients. TheFigure 2: All-cause mortality for chemoradiotherapy compared with surgery aloneEff ects of chemoradiotherapy compared with surgery alone on survival in patients with oesophageal cancer (A) and in subgroups of patients with oesophageal carcinoma (squamous-cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma or pooled histology type subgroups; B). SCC=squamous-cell carcinoma. *Includes all randomised patients.†Includes four patients whose histology was unknown or who had mixed tumours. ‡Includes three patients whose histology was unknown or who had mixed tumours.updated work includes information on 3994patients for neoadjuvant treatments compared with surgery alone and 194 patients for comparisons of neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy with neoadjuvant chemotherapy. This updated meta-analysis contains about 3500 events compared with 2230 in the previous meta-analysis (estimated 57% increase).22 randomised trials were suitable for inclusion in the quantitative analysis of the survival benefi ts of neo a djuvant treatment with either neoadjuvant chemo-therapy or neoadjuvant chemoradio t herapy,1,7,8–14,17,19–24,37,39–43 and two were suitable for inclusion in the quantitative analysis of neoadjuvant chemotherapy with neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy.15,18 17 of these were included in the previous publication (webappendix p 1),9,10,12–14,16,17,19–24,38–40 three of which have been updated,1,8,43 and fi ve new eligible studies were identifi ed.7,11,37,41,42 Four studies were excluded from the previous meta-analysis because ofFigure 3: All-cause mortality for chemotherapy compared with surgery aloneEff ects of chemotherapy compared with surgery alone on survival in patients with oesophageal cancer (A) and in subgroups of patients with oesophageal carcinoma (squamous-cell carcinoma or adenocarcinoma histology; B). *Includes ten patients whose histology was unknown or who had mixed tumours. †Includes 12 patients whose histology was unknown or who had mixed tumours.unclear or unavailable information. We wrote to all these authors again but were unable to obtain suffi cient information for three of the four studies to allow inclusion in this analysis. Reasons for exclusion were: unclear randomisation method,26 analysis not by intention to treat,44 and full text not in English and insuffi cient information available in English abstract.25 The remaining study was excluded from the previous quantitative analysis because it had only been published in abstract form28 at the time of the previous publication. The long-term results have recently been published and are now included.37 All patients had stages T0–3, N0–1 disease according to the 2002 AJCC staging.45 There were no major differences in the age of participants between studies or groups, although no formal statistical comparison was done. Three trials included only patients with early (stage I–II) disease, all of which compared neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy with surgery alone.10,11,46 Table 1 summarises details of all trials included in the meta-analysis.13 studies were included in the comparison of neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy with surgery alone in patients with resectable oesophageal carcinoma (n=1932): 12 were randomised comparisons of neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy followed by surgery with surgery alone10–14,16,17,22,39–42 and one study included this comparison within a 2 × 2 factorial study.9 Ten had been included in the previous meta-analysis;6 of these, one (Tepper16) had been published only in abstract form, and the data included in this version is the updated fi nal publication.43 Two additional trials (Mariette11 and van der Gaast42) were presented at the American Society of Clinical Oncology meeting in June, 2010, and one study was published since the previous meta-analysis.41 One further publication from China with an English abstract was identifi ed;33 however, it was not included because the information from the abstract was insuffi cient to calculate an HR and we were unable to obtain further details from the author. A test for potential publication bias suggested ten potentially unpublished s tudies f or n eoadjuvant c hemoradiotherapy, but 23 more studies with a HR of 1·0 would need to be added to these 13 to produce an overall non-signifi cant result, suggesting that the meta-analysis is robust to publication bias.Figure 2 shows pooled estimates for all-cause mortality for the trials that compared neoadjuvant chemoradiot-herapy followed by surgery with surgery alone. The pooled HR was 0·78 (95% CI 0·70–0·88; p<0·0001). This corresponds to an absolute survival benefi t at 2 years of 8·7% and a number needed to treat of 11. There was no evidence of signifi cant heterogeneity between the trials or between pooled results by tumour histology. The survival benefi ts for neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy were similar in the tumour type subgroups: squamous-cell carcinoma (HR 0·80, 95% CI 0·68–0·93; p=0·004) and adeno-carcinoma (0·75, 0·59–0·95; p=0·02).Ten studies were included in the comparison of neoadjuvant chemotherapy with surgery alone (n=2062): nine were randomised comparisons of neoadjuvant chemotherapy with surgery alone1,7,8,19–21,23,24,37 and one study included this comparison within a 2 × 2 factorial study.9 Eight studies were included in the previous meta-analysis, two of which had been updated since our previous publication.1,8 One study37 had only been published in abstract form28 at the time of the previous publication and was previously excluded from the quantitative analysis. One study included adeno-carcinomas of gastric, oesophagogastric junction, and oesophageal origin, but was eligible for the quantitative analysis because the fi nal publication reported outcomes by tumour location.7 Only the outcomes for theFigure 4: Indirect comparison of all-cause mortality for chemoradiotherapy and chemotherapy169 patients (85 neoadjuvant chemo t herapy and 84 surgery alone) with tumours arising in the oesophagogastric junction and oesophagus were used. The HRs for oesophageal and oesophagogastric junction tumours from this study were pooled to give an HR of 0·63 (95% CI 0·45–0·89; fi gure 3). We identifi ed two studies that included oesophagogastric junction tumours and primary gastric adenocarcinomas, the UK MAG IC trial34 and the European Organisation for Research and treatment of Cancer (EORTC) 40954 study.35 The numbers of patients with lower oesophageal and oesophagogastric cancers were small (n=73 and n=58, respectively in MAGIC34 and n=76 for oesophagogastric in EORTC35), and most patients received a gastrectomy. Also, these studies did not publish outcomes by tumour site and so were excluded from the quantitative meta-analysis. In the UK MAG IC trial,34 there was a signifi cant survival advantage for patients who received perioperative chemotherapy. However, the EORTC study,35 which examined preoperative treatment, was closed because of poor accrual and did not show a survival advantage for this strategy. Using the HR for the primary oesophageal cancer subgroups from the MAG IC study (HR 0·75, 95% CI 0·42–1·33; p=0·33), as provided by the investigators (personal communication) we did a sensitivity analysis. This analysis did not aff ect the overall estimate of benefit from neoadjuvant chemotherapy (HR 0·87, 95% CI 0·87–0·95; p=0·001).One additional study had final results published in abstract form as part of conference proceedings.36 The authors reported a disease-free survival advantage for the chemotherapy arm; however, information about censored observations was not reported. Attempts to obtain further information from the authors were unsuccessful and hence the study was not included in the main analysis. We did a sensitivity analysis with an HR calculated by estimating the relative risk from the overall survival rates reported at years 3 and 5 in each treatment arm, by a method described by Parmar.29 The inclusion of this study did not substantially change the pooled HR for neoadjuvant chemotherapy compared with surgery alone (HR 0·86, 95% CI 0·79–0·94; p=0·001). A test for potential publication bias suggested that there are zero potentially unpublished studies on neoadjuvant chemo-therapy compared with surgery alone, and 15 further studies with an HR of 1·0 would need to be added to these ten studies to produce an overall non-signifi cant result. Figure 3 shows the pooled estimate for all-cause mortality for trials that compared neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by surgery with surgery alone. The pooled HR was 0·87 (0·79–0·96; p=0·005).This corresponds to an absolute survival diff erence at 2 years of 5·1%, which is equivalent to a number needed to treat of 19. A subgroup analysis by histological type for those studies where histology data were available gave an HR for squamous-cell carcinoma of 0·92 (95% CI 0·81–1·04; p=0·18) and for adeno c arci n oma of 0·83 (0·71–0·95; p=0·01). There was no evi d ence of signi fi cant heterogeneity overall or between sub g roups by tumour histology.For the second component of the meta-analysis, assessing the survival benefits of neoadjuvant chemo-therapy compared with neoadjuvant chemo r adiotherapy, we identifi ed two studies, one published before18 and one published after15 the database search (n=194).TheG erman study18 included only patients with oesophagogastric junction adenocarcinoma and used 15 weeks of chemotherapy in each arm and 18% had a gastrectomy only. The subsequent Australian trial compared these modalities, but used two cycles of cisplatin and fl uorouracil and radiotherapy of 35 Gy in 15 fractions starting on day 22.15 The outcomes in the chemoradiotherapy arm were similar to those of the German study, but the preoperative chemotherapy group had higher median and 3-year survivals.15 Neither trial showed an advantage for neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy over neoadjuvant chemotherapy, although both trialsclosed prematurely and were consequently underpowered to detect a signifi cant survival advantage. We combined these two studies with the pooled results of thechemotherapy arms from the other analysed studies to compare the survival benefits of neoadjuvant chemo-radiotherapy and neoadjuvant chemotherapy (n=2220). Figure 4 shows the estimates for all-cause mortality for the two individual studies and the pooled indirect comparison. The HR from the randomised comparisons was 0·77 (95% CI 0·53–1·12; p=0·17), in favour of neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy. From the indirect comparison, the HR was 0·90 (0·77–1·04; p=0·15). Combining the indirect and direct comparisons yielded an overall HR of 0·88 (0·76–1·01; p=0·07). Compared with the direct comparison, the discrepancy of the indirect comparison (ie, ratio of the indirect and direct HRs) was 17% larger (HR 1·17, 0·78–1·75; p=0·45).We also examined whether the potential benefi t of the neoadjuvant treatment regimens was off set by a higher mortality rate by comparing the benefit (HR) with the absolute 30-day or in-hospital mortality diff erence (as a percentage) between the control and intervention arms (table 2 and fi gure 5). There was little association between risk of postoperative mortality (in-hospital or 30-day postoperative death) and the neoadjuvant interventions. We examined the relation between the benefi ts achieved by the addition of neoadjuvant treatment and the outcome in the surgery alone group by plotting the logarithm of the HR against the absolute 2-year survival in the control group for each trial. The webappendix p 2 shows this finding for chemotherapy and chemoradiotherapy. As the 2-year survival in the control group increased (a better prognosis for patients in the trial), there seemed to be a smaller benefi t from the intervention, but this was not statistically signifi cant (neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy p=0·84; neoadjuvant chemotherapy p=0·82). DiscussionSurvival benefi ts of neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy and neoadjuvant chemotherapy were shown in the previous meta-analysis by our group.6 This updated analysisincluded updated data on previously published studies and additional studies, with 43% more patients and about 57% more events compared with the previous meta-analysis. The additional information has strengthened the evidence of a survival advantage of neoadjuvant therapy compared with surgery alone. In the present meta-analysis, there is evidence in favour of both neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy and neoadjuvant chemotherapy before surgery. The evidence supporting the use of chemo-radiotherapy is not only stronger than previously reported but is also clear for both squamous-cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma histologies. Neoadjuvant chemo t herapy also seemed to be associated with improvements in each histological subtype compared with surgery alone, although the treatment effects were not as large as for chemoradiotherapy. Both treatment strategies causetoxicities that are well known and that potentially increasethe risk of surgical morbidity.There is evidence that neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapyincreases the rate of complete resection,15,47 particularlyfor patients with locally advanced disease, although thisincrease has not always translated into a survival benefi tin individual studies. The two most recent trials thatassessed neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy have beenreported as abstracts only.11,42 In the larger Dutch trial,42there was a survival benefit for patients who had neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy with paclitaxel andcarboplatin weekly for 5 weeks with 41·4 Gy radiotherapycompared with those who had surgery alone.In theFrench trial,11 in which patients received the typicalFigure 5: Effect of chemoradiotherapy or chemotherapy on 30-day or in-hospital absolute mortality Eff ect of chemoradiotherapy (A) and chemotherapy (B) compared with surgery alone in patients with oesophageal carcinoma.。