Stylistics

(最新整理)Stylistics(英语文体学)

II. What is style?

style as rhetoric — Gorgias(风格即 修辞);

style as form — Aristotle(风格即形 式);

style as eloquence — Cicero (风格即 雄辩术);

proper words in proper places —

2021/7/26

15

Langue(语言)(Longman Dictionary P382)

The French word for “language”. The

term was used by the linguist Saussure

to mean the system of a language, that is the arrangement of sounds and

interpretation of the text; or in order to

relate literary effects to linguistic

‘causes’ where these are felt to be

relevant…. Stylisticians want to avoid

situationally-distinctive uses of

language, with particular reference to

literary language, and tries to establish

principles capable of accounting for the

saying the right thing in the most effective way — Enkvist(以最有效 的方式讲恰当的事情) ;

文体翻译

7.文体学研究采用什么方法?

采用描写、比较、频率统计三个方法。 (1)描写:从语言、修辞、语义、语用角度 对各种文体进行分析。 (2)比较:不同文体或同一文体的不同文献 品种和体裁之间进行对比,找出它们之间 的对应关系、共同来源和发展趋向,了解 不同语篇结构的个性和共性。

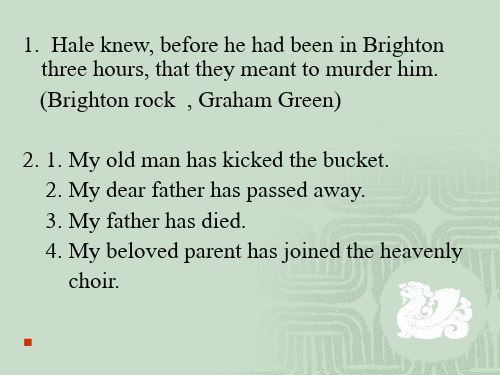

(3)适切:根据实用语篇的功能和目的,译文要进行调整, 适合译入国的规范。 伴随着改革开放的脚步,21幼儿园走过了13年的发展历程, 经过全体职工的努力,他们连续7年被评为区级教育工作 和全面工作管理优秀单位;1997-1999年市先进单位。 The 21st Kindergarten has been a success since it was set up 13 years ago. For 7 consecutive years, it has been given various honorary titles by Hedong Disitrct. From 1997 to 1999 it was commended by the municipal government for its hygienic conditions.(李欣译) 评:原文套话多,“优秀单位”、“先进单位”很难定义, 如果照直翻译,显得臃肿,英语读者不解。

(2)商业经济英语: A.学术英语:经济学、会计学、经贸 B.职业英语:秘书、会计、外销员 (3)社科英语: A.学术英语:新闻、法律、图书馆学 B.职业英语:法官、记者、图书管理员

9.文体的功能特征是什么? (1)信息性: The world's largest economy expanded at a 3.5pc annual pace in the third quarter of the year, marking the end of a recession that has cost 7.2 million American jobs and prompted the most radical Government response since the Depression of the 1930s. The figure topped the prediction of Wall Street analysts who had pencilled in growth of 3.2pc. 世界最大的经济体美国今年第三季度经济增长3.5%, 此为经济衰退结束的信号。本次危机使美国失去720万工 作岗位,美国政府采取了1930年来代以来最为激进的措施。 该数据比华尔街分析师的预测3.2%要高。

Stylistics中文文体学课件

3. I ‘m finding out that a lot of what I thought had been bonfired, Oxfam-ed, used for land-fill, has in fact been tidied away in sound archives, stills libraries, image banks, memorabilia mausoleums, tat troves, mug morgues.

Cf. A. The police are investigating the case of

murder. B. The police are looking into the case of

murder. (Lexically, Latin, French, Greek words are generally used in formal style; Words from old English are mostly used in informal style.)

F: He left early in order not to miss the train.

F: He left early in order that he would not miss the train.

6. 问句:

F: When are you going to do it?

IF: When

place all the same.

F: He endeavoured to prevent the marriage ; however, they married notwithstanding. 3. 非正式文体常用副词做状语;而正式文体常 用由介词和与该副词同根的词够成的介词短 语:

stylistics12

4). The systemic-functional 系统功能语言学 linguists headed by M. A. K. Halliday sees language as a ‘social semiotic 符号', as an instrument used to perform various functions in social interaction. This approach holds that in many crucial respects, what is more important is not so much that 'man talks' as that 'men talk'; that is, that language is essentially a social activity (Halliday, 1978).

Relevant Terms

People’s activities: physical acts such as cooking, eating, bicycling, running a machine, cleaning, and verbal acts of all types: conversation, telephone calls, job application letters;

2. She wants to put her tongue in your mouth. 这句话出现在一则只有一个笑不露齿的中年妇女 大半身照的广告上; 这是什么广告?这句话是什么 意思呢?

Stylistics

1. Stylistics-- Simply defined, it is a discipline that studies the ways in which language is used; it is a discipline that studies the styles of language in use.

Chapter 12 stylistics

Definition (2)

❖ Stylistics is the (linguistic) study of style, simply as an exercise in describing what use is made of language. Literary stylistics has, implicitly or explicitly, the goal of explaining the relation between language and artistic function.

❖ Aspects of style: the Text – style as Linguistic sameness (是语言统一的风格)

❖ Aspects of style: the Text – style as linguistic difference(是语言差异的风格)

1. Introduction:

❖ From the linguist’s angle, it is ‘why does the author here choose to express himself in this particular way?’

❖ From the critic’s viewpoint, it is ‘how is such-and-such an aesthetic effect achieved through language?’

To archaeologists

❖ A means of tracing relationships between schools of art; a manifestation of the culture To historians as a whole

stylistic

1.What is stylistics? Why is it necessary for us to learn stylistics?Stylistics means a discipline that studies the sum of stylistic features characteristic of the different varieties of language. It concerns itself with the situational features that influence variations in language use, the criterion for the classification of language variety, and the description of the linguistic features and functions of the main varieties of a language.Stylistics study: a. helps develop a consistent method of language analysis and solve problems of interpretation by bringing into focus the stylistically significant features.b. helps cultivate a sense of appropriateness and acquire a sense of style.c. sharpens understanding and appreciation of literary works.d. helps achieve adaptation in translation.2.How does Martin Joo describe the range of formality in his book?M’s range of formality: frozen, formal, consultative, casual, and intimate.3.What factors affect the degree of formality?a.S peech situation: setting purpose, audience, social relations and topic.b.L inguistic features: vocabulary; phonology syntax and semantics.4.What is a dialect? What is the relationship between regional and social dialects?Dialect:means language variations associated with different users of the language.5.What are the functions of a headline in a press advertisement?Headline is the theme and center of advertisement, often in the most conspicuous position to attract consumers’ attention. Therefore, headline is crucial to the success of advertisement. But what kind of headline is a good headline? Here are a few suggestions:(1)Hit on what readers like, and make them feel it will benefit them.(2) Try to introduce new things.(3) Use words that could arouse readers’ interest.(4) Avoid using vague words, avoid using privative words.6.What are the functions of a body copy in a press advertisement?Body CopyAfter consumers' attention has been attracted to the advertisement by headline, they will move to the body copy, which is the main part of advertising information, to find something useful. Whether an advertisement has met the consumers’ requirement, satisfied their desire, and stimulated them to take action are the factors to judge the quality of a good advertisement.7.What are the stylistic features of the press advertisement?Ⅰ. Lexical featuresa. One-syllable and simple verbs such as get and make are used.b. Emotive adjectives are adopted to arouse reader’s interest.c. Words are carefully chosen to make pun and alliteration.d. Weasel words, such as help and like, make the use of strongest language possible in advertisements.Ⅱ. Syntactical featuresa. Sentences in advertisements are short. On average, a sentence consists of11.8 words.b. Elliptical sentences are used to spare advertising cost and at the same time improve advertising effectiveness.c. Interrogative sentences and imperative sentences are common in advertisementsd. Present tense prevails in ads to suggest timelessness. And active voice is used to cater to audience’s habit in daily talk.Ⅲ. Discour se featuresA complete advertisement consists of five parts: Headline, Body Copy, Slogan, IllustrationAnd Trade Mark.Body copy is the key part, conveying product or service information.8.What are main components of a press advertisement?10. Summarize the basic requirements for the language of a effective advertisement?11. What are the stylistic features of public speech?Grammatical features:(1). Variation in sentence length, sentence are mostly of the SP(O)(C)(A) structure with occasional ASPOC(A) form.(2). Various sentence type: a. As public speeches are intended to inform ,to persuade, and to appeal, most sentences are statements; occasional questions are used to give the audience food for thought and to impress them.b. Commands can be many, often introduced by “let”.c. Vocatives of a general type are used.(3). More complex-looking group structures.Lexical features:(1). Often use accurate and clear words.(2). Adaptation of wording to particular audience.(3). Less use of phrasal verbs.Phonological features:(1). Appropriate volume and pitch variation.(2). Varying tempo and rightly timed pause.(3). Often seek to use the rhythm of language by their choice and arrangement of words.(4). Public speech is directed toward an audience sometimes very large so the speaker has to guard against sloppy articulation and articulate each word clearly and accurately. In such a variety, assimilations should not occur, but elision can sometimes occur.(5). Full use of non-verbal communication: gestures, eyes and etc.Semantic features:(1). Problem-cause-solution order (attention, need, satisfaction, visualization and action.). The use of pairs of transitional phrases stating both the idea that the speaker is leaving and the one he is coming up to.The use of internal previews and summaries.The uses of signposts like numbers, questions or simple phrase to help the audience keep track of where the speaker is in the speech.(2). Effective ways of delivery:a. parallelism makes the statement clear, consistent and compelling.b. antithesis contrasts ideas in a formal structure of parallelism.c. repetition helps creat a strong emotional effort.d. synonymous words are repeated to add force, clearness or balance a sentence.e. alliteration to catch the attention of audience and make ideas easier to remember.f. figurative use of language.12. What functions does a newspaper serve?Newspapers provide us with news, advertisement, editorials, cartoons, comics, fiction poems, book reviews, and art criticisms and so on. The central function of a news paper is to tell us news (functional tenor), written chiefly to be red (mode); and has different categories and different formats (straight tenor).13. What are the functions of a headline in a newspaper?Headlines play a vital part in drawing the reader’s attention to the news story.A good headline summarizes the story so that the hurried reader can get the gist of a story at a glance and evaluate the news immediately.14. What are the stylistic features of news reporting?Graphological features:Variation in the size and shapes of body types, especially the highlighting ofthe headlines, sometimes juxtaposed with pictures.Headlines often have a variety of sizes and shapes of even a different color.The news story is split into smaller nits-the use of subheadings, very short paragraphs for eye-catching and easier-to-read affect.Characteristic use of punctuation is obvious. Inverted commas are frequently used for direct or indirect quotation, or to spotlight terms for particular attention.Grammatical features:(1). Alternating use of long and short statement-type sentences.(2). Use of heavily modified nominal groups to wrap a large amount of information into the group.(3). Use of simple verbal groups.Lexical features: (use simple, accurate and vivid words)(1). Preference for journalistic words and set expressions.(2). Wide use of neologisms for eye-catching effect.a. words with extended meaning.b. nonce-words.c. coinages.d. words borrowed extensively from sports, military, commerce, science and the technology, gambling or even words from other languages.(3). Extensive use of abbreviation.(4). Avoidance of superlatives and tarnished word ornaments.(5). Avoidance of unobje ctive wording. Avoid the use of “I”, “me”, “my”, “our”in a news story except when quoting someone phrase in a news story should be factual, not tinged with the personal opinion of feelings of the reporter.Semantic features(1). Distinctive discourse pattern: inverted pyramid.(2). Simple way of transition: the unity of the news story is achieved through the obvious relatedness between sentences within a paragraph within a story, or with the use of common connectives.(3) skillful headline: headlines are noted for their wide use of ellipsis with frequent omission of articles, possessives, verb “be’, even content words, so as to shorten the length and to be more concise and comprehensive.a. wide use of present tense to convey a sense of freshness and immediacy of an event.b. future happenings are often expressed with a infinitive.c. composed of nominal groups.d. ing-forms are frequent as headlines.e. whole-sentence headlines even in the form of direct quote or command.f. seek novelty and humor rhetorically.g. alluding, punning, various figurative use of language.style: 1) a person’s distinctive language habits, or the set of individual characteristics of language use.2) a set of collective characteristics of language use; language habits share bya group of people at a given time, in a given place, amidst a given occasion, for a literary genre, etc.3) the effectiveness of a mode of expression4) a characteristic of “good” or “beautiful” literary writing.Diatypic varieties (register): language variations associated with the different use to which they are put. Registers may be distinguished according to field, mode and tenor of discourse.Dialectal varieties (dialects): means language variations associated with different users of the language.Individual dialect (idiolect): a person’s particular speech or writing style which result from such traits as his voice quality, pitch and stress patterns, favorite lexical items, and even grammatical structure.Temporal dialect: a variety which correlates with the various periods of the development of language: Old English, Middle English, Elizabethan English and Modern English.Regional dialect: a variety associated with various regions such as phonology, graphology, vocabulary and grammar.Social dialect:a variety associated with certain social group. 4 varieties of social dialect: socioeconomic status varieties, ethnic varieties, gender varieties and age varieties.Standard dialect: the variety of a language based on the speech and writingof educational native speakers of that language. Used in news media and described in dictionaries and grammars.Field of discourse:the linguistic reflection of the purposive role of the language user-the type of social activity the language user is engaged in doing in the situation in which the text has occurred.Mode of discourse:the linguistic reflection of the relationship that the language user has to the medium of communication.Tenor of discourse:the linguistic reflection of the personal relationships between speaker and hearer, and of what the user is trying to do with language for his addresses.Functional tenor:concerned with the intention of the user in using the language.Phonology: the study of the rules for the organization of sound system of a language.Graphology: the study of the writing system of language.Cohesion: implicit connectivity works best for sequence of events and reason.。

[英语学习]文体学1

![[英语学习]文体学1](https://img.taocdn.com/s3/m/c651884bddccda38376baf9b.png)

• •

• Implication: (Assumptions) • A.Linguistics should be most helpful in analyzing and interpreting literary texts. • B) literature is a type of communicative discourse.

• The Purposes for study of stylistics • To appreciate the English literature works • To master some general knowledge about variations of English • To improve English level • To construct a critical view towards matter • To build a new way of thinking

ቤተ መጻሕፍቲ ባይዱ

• 1 Definition of Stylistics • Stylistics=style+ linguistics • STYLE: Chapter Two • Linguistics: the study of language in which theories on languages have been fully investigated • Take some language theories as example • Cooperative principles • Politeness principles • Ambiguity of languages

• Implication: stylistic features do not occur randomly in it but form patterns. And stylisticians can account for literary texts not just intrasententially but also intersententially, not only in terms of linguistic facts and theory but also in terms of sociolinguistic facts and theory.

Stylistics

Stylistics is a branch of linguistics which applies the theory and method ology of mod ern linguistics to the study of style.It studies the use of language in specific contexts and attempts to account for the characteristics that mark the language use of individuals and social groups. It is usually concerned with the examination of written language, particularly literary texts. The stylistic analysis of a text involves the d escription of a writer’s/speaker’s verbal choices which can be abstracted as style.Concepts of style:1.”styl e” may refer to some or all of the language habits of one person. 2.The word may refer to some or all of the language habits shared by a group of peopl e at one time,or over a period of time. 3.the word may be used in an evaluative sense, referring to the effectiveness of a mod e of expression. 4.Partly overlapping with the three senses just mentioned, the word may refer solely to literary language.The needs for stylistics:1.styl e is an integral part of meaning. 2.Stylistics may help us to acquire a “sense of styl e”. 3.Stylistics prepares the way to the intrinsic study of literature.The concept of text: A text is any passage, spoken or written, of whatever length, that forms a unified whole. A text is realized by a sequence of language units, whether they are sentences or not.The concept of context: “Context” has been und erstood in various ways. It may be linguistic or extra-linguistic. Linguistic context is alternatively termed as CO-TEXT, which refers to the linguistic units preceding and/or following a particular linguistic unit in a text. Extra-linguistic context refers to the relevant features of the situation in which a text has meaning. The term CONTEXT may includ e not only the co-text, but also the extra-linguistic context of a text.An elliptical sentence is contextually conditioned. The ellipsis is recoverable from the preceding linguistic context. The ellipsis avoids repetition so as to focus on the new information.Incomplete sentences: sentences in which for some reason the speaker never reaches the end of what he intends to communicate.Reiteration refers to the use of an alternative expression as a replacement for an expression in the preceding context.Collocation may refer to: A. the conventional restriction of the ways in which words are used together. B. a tend ency of co-occurrence. Sets of words tend to turn up together.Medium refers to graphic signs or speech sounds by meas of which a message is conveyed from one person to another.Attitud e is related to the Role Relationships in various situations. Role Relationships range from temporary to permanent. Some role relationships are easier to id entify by the language than others.Fiel d of discourse refers to the type of social activity in which language plays a part. One aspect of the field is the subject matter. The subject matter can be practically anything, ranging from technical to non-technical: the theory of relativity, physiology and medicine.Another important aspect of the field—the purpose which the language serves in a social activity.The administration=the government/ apartment=flat/attorney=solicitor or barrister/automobile=car/bar=pub/biscuit=scone/can=tin/cookie or cracker=biscuit/elevator=lift/engineer=engine driver/faculty=staff/fall=autumn/first floor=ground floor/gas or gasoline=petrol/mail=post/movie=firm/one way ticket=single(ticket)/overpass=flyover/round-trip ticket=return(ticket)/sneakers=plimsolls/store=shop/truck=lorry or van/yiel d=give awayslang: baby=girl or woman/bad=good or excellent/hip=sophisticated or uptodate/high=a non-intoxicated feeling of exhilaration/square=a conventional person/swell or super or some=good or excellent or outstanding or notable or distinguished/a couple of=a few/kind of or sort of=somewhat or rather/a lot or lots of=a great d eal or many/sure=surely or absolutely/awfully or so or plenty or real=very or extremely or exceedingly or acutelyeuphemisms: senior citizen for ol d man or woman/newly single for divorced/memorial park for graveyard/funeral director for und ertaker/sanitation collector for garbage collector/industrial action for strike/to eliminate for to kill or to murd er/domestic helper for servant/hair stylist for barber/airhostess for waitress aboard a plane/knowl edge-based nonpossessor for idiot/the South, or the developing countries for countries that have littl e industrialization and low standard of living/Two freedom fighters took the oppressor’s life away for The general was murdered by two terrorists头韵:Alliteration/腹韵:Assonance/辅韵:Consonance/倒韵:Reverse Rhyme/头尾韵:Pararhyme/韵:Rhyme。

语言学讲义 考研 9 Stylistics

• In addition, stylistics is a distinctive term that may be used to determine the connections between the form and effects within a particular variety of language.

5

• Other features of stylistics include the use of dialogue, including regional accents and people‘s dialects, descriptive language, the use of grammar, such as the active voice or passive voice, the distribution of sentence lengths, the use of particular language registers语域, etc.

4

• Stylistics also attempts to establish principles capable of explaining the particular choices made by individuals and social groups in their use of language, such as socialisation, the production and reception of meaning, critical discourse analysis and literary criticism.

However, in Linguistic Criticism, Roger Fowler makes the point that, in non-theoretical usage, the word stylistics makes sense and is useful in referring to an enormous range of literary contexts, such as John Milton‘s ‗grand style‘, the ‗prose style‘ of Henry James, the ‗epic‘ and ‗ballad style‘ of classical Greek literature, etc. (Fowler, 1996: 185).12题三:Chiming 谐音

Chapter 9 Stylistics

• Style was first presumably involved in classical rhetoric (McArthur, 1992), the art of good speaking in the time of Aristotle. Style in classical rhetoric is mainly concerned with how the arguments in persuasion or public speaking can be dressed up into effective language.

• Widdowson (1975: 3): “the study of literary discourse from a linguistic orientation”.

• Baldick(1991) a branch of modern linguistics devoted to the detailed analysis of literary style, or of linguistic choices made by speakers and writers in non-literary contexts.

WHAT IS STYLISTICS

WHAT ISINTRODUCTIONSTYLISTICS?Some years ago, the well-known linguist Jean-Jacques Lecercle published a short butdamning critique of the aims, methods and rationale of contemporary stylistics. Hisattack on the discipline, and by implication the entire endeavour of the present book, wasuncompromising. According to Lecercle, nobody has ever really known what the term'stylistics' means, and in any case, hardly anyone seems to care (Lecercle 1993: 14).Stylistics is 'ailing'; it is 'on the wane'; and its heyday, alongside that of structuralism, hasfaded to but a distant memory. More alarming again, few university students are 'eager todeclare an intention to do research in stylistics'. By this account, the death knell ofstylistics had been sounded and it looked as though the end of the twentieth centurywould be accompanied by the inevitable passing of that faltering, moribund discipline.And no one, it seemed, would lament its demise.Modern stylisticsAs it happened, things didn't quite turn out in the way Lecercle envisaged. Stylistics inthe early twenty-first century is very much alive and well. It is taught and researched inuniversity departments of language, literature and linguistics the world over. The highacademic profile stylistics enjoys is mirrored in the number of its dedicated book-lengthpublications, research journals, international conferences and symposia, and scholarlyassociations. Far from moribund, modern stylistics is positively flourishing, witnessed ina proliferation of sub-disciplines where stylistic methods are enriched and enabled bytheories of discourse, culture and society. For example, feminist stylistics, cognitivestylistics and discourse stylistics,to name just three, are established branches ofcontemporary stylistics which have been sustained by insights from, respectively,feminist theory, cognitive psychology and discourse analysis. Stylistics has also becomea much valued method in language teaching and in language learning, and stylistics inthis 'pedagogical' guise, with its close attention to the broad resources of the system oflanguage, enjoys particular pride of place in the linguistic armoury of learners of secondlanguages. Moreover, stylistics often forms a core component of many creative writingcourses, an application not surprising given the discipline's emphasis on techniques ofcreativity and invention in language.So much then for the current 'health' of stylistics and the prominence it enjoys inmodern scholarship. It is now time to say a little more about what exactly stylistics is andwhat it is for. Stylistics is a method of textual interpretation in which primacy of place isassigned to language.The reason why language is so important to stylisticians is becausethe various forms, patterns and levels that constitute linguistic structure are an importantindex of the function of the text. The text's functional significance as discourse acts inturn as a gateway to its interpretation. While linguistic features do not of themselvesconstitute a text's 'meaning', an account of linguistic features nonetheless serves toground a stylistic interpretation and to help explain why, for the analyst, certain types ofmeaning are possible.The preferred object of study in stylistics is literature, whether thatbe institutionally sanctioned 'Literature' as high art or more popular 'noncanonical' formsof writing. The traditional connection between stylistics and literature brings with it twoimportant caveats, though.WHAT IS STYLISTICS? 3 The first is that creativity and innovation in language use should not be seen as the exclusive preserve of literary writing. Many forms of discourse (advertising, journalism, popular music - even casual conversation) often display a high degree of stylistic dexterity, such that it would be wrong to view dexterity in language use as exclusive to canonical literature. The second caveat is that the techniques of stylistic analysis are as much about deriving insights about linguistic structure and function as they are about understanding literary texts. Thus, the question 'What can stylistics tell us about literature?' is always paralleled by an equally important question 'What can stylistics tell us about language?'.In spite of its clearly defined remit, methods and object of study, there remain a number of myths about contemporary stylistics. Most of the time, confusion about the compass of stylistics is a result of confusion about the compass of language. For instance, there appears to be a belief in many literary critical circles that a stylistician is simply a dull old grammarian who spends rather too much time on such trivial pursuits as counting the nouns and verbs in literary texts. Once counted, those nouns and verbs form the basis of the stylistician's 'insight', although this stylistic insight ultimately proves no more far-reaching than an insight reached by simply intuiting from the text. This is an erroneous perception of the stylistic method and it is one which stems from a limited understanding of how language analysis works. True, nouns and verbs should not be overlooked, nor indeed should 'counting' when it takes the form of directed and focussed quantification. But the purview of modern language and linguistics is much broader than that and, in response, the methods of stylistics follow suit. It is the full gamut of the system of language that makes all aspects of a writer's craft relevant in stylistic analysis. Moreover, stylistics is interested in language as a function of texts in context, and it acknowledges that utterances (literary or otherwise) are produced in a time, a place, and in a cultural and cognitive context. These 'extra-linguistic' parameters are inextricably tied up with the way a text 'means'. The more complete and context-sensitive the description of language, then the fuller the stylistic analysis that accrues.The purpose of stylisticsWhy should we do stylistics? To do stylistics is to explore language, and, more specif-ically, to explore creativity in language use. Doing stylistics thereby enriches our ways of thinking about language and, as observed, exploring language offers a substantial purchase on our understanding of (literary) texts. With the full array of language models at our disposal, an inherently illuminating method of analytic inquiry presents itself. This method of inquiry has an important reflexive capacity insofar as it can shed light on the very language system it derives from; it tells us about the 'rules' of language because it often explores texts where those rules are bent, distended or stretched to breaking point. Interest in language is always at the fore in contemporary stylistic analysis which is why you should never undertake to do stylistics unless you are interested in language.Synthesising more formally some of the observations made above, it might be worth thinking of the practice of stylistics as conforming to the following three basic principles, cast mnemonically as three 'Rs'. The three Rs stipulate that:4INTRODUCTIONοstylistic analysis should be rigorousοstylistic analysis should be retrievableοstylistic analysis should be replicable.To argue that the stylistic method be rigorous means that it should be based on an explicit framework of analysis. Stylistic analysis is not the end-product of a disorganised sequence of ad hoc and impressionistic comments, but is instead underpinned by structured models of language and discourse that explain how we process and understand various patterns in language. To argue that stylistic method be retrievable means that the analysis is organised through explicit terms and criteria, the meanings of which are agreed upon by other students of stylistics. Although precise definitions for some aspects of language have proved difficult to pin down exactly, there is a consensus of agreement about what most terms in stylistics mean (see A2 below). That consensus enables other stylisticians to follow the pathway adopted in an analysis, to test the categories used and to see how the analysis reached its conclusion; to retrieve, in other words, the stylistic method.To say that a stylistic analysis seeks to be replicable does not mean that we should all try to copy each others' work. It simply means that the methods should be sufficiently transparent as to allow other stylisticians to verify them, either by testing them on the same text or by applying them beyond that text. The conclusions reached are principled if the pathway followed by the analysis is accessible and replicable. To this extent, it has become an important axiom of stylistics that it seeks to distance itself from work that proceeds solely from untested or un testable intuition.A seemingly innocuous piece of anecdotal evidence might help underscore this point.I once attended an academic conference where a well-known literary critic referred to the style of Irish writer George Moore as 'invertebrate'. Judging by the delegates' nods of approval around the conference hall, the critic's 'insight' had met with general endorsement. However, novel though this metaphorical interpretation of Moore's style may be, it offers the student of style no retrievable or shared point of reference in language, no metalanguage, with which to evaluate what the critic is trying to say. One can only speculate as to what aspect of Moore's style is at issue, because the stimulus for the observation is neither retrievable nor replicable. It is as if the act of criticism itself has become an exercise in style, vying with the stylistic creativity of the primary text discussed. Whatever its principal motivation, that critic's 'stylistic insight' is quite meaningless as a description of style.Unit A2, below, begins both to sketch some of the broad levels of linguistic organ-isation that inform stylistics and to arrange and sort the interlocking domains of language study that playa part in stylistic analysis. Along the thread, unit Bl explores further the history and development of stylistics, and examines some of the issues arising. What this opening unit has sought to demonstrate is that, over a decade after Lecercle's broadside, stylistics as an academic discipline continues to flourish. In that broadside, Lecercle also contends that the term stylistics has 'modestly retreated from the titles of books' (1993: 14). Lest they should feel afflicted by some temporary loss of their faculties, readers might just like to check the accuracy of this claim against the title on the cover of the present textbook!STYLISTICS AND LEVELS OF LANGUAGESTVLlSTICS AND LEVELS OF LANGUAGE5In view of the comments made in Al on the methodological significance of the three Rs, it is worth establishing here some of the more basic categories, levels and units of analysis in language that can help organise and shape a stylistic nguage in its broadest conceptualisation is not a disorganised mass of sounds and symbols, but is instead an intricate web of levels, layers and links. Thus, any utterance or piece of text is organised through several distinct levels of language.Levels of languageTo start us off, here is a list of the major levels of language and their related technical terms in language study, along with a brief description of what each level covers:level of languageThe sound of spoken language;the way words are pronounced.The patterns of written language;the shape of language on the page.The way words are constructed; words and their constituent structures.The way words combine with other words to form phrases and sentences.The words we use; the vocabularyof a language.The meaning of words and sentences. The way words and sentences are used in everyday situations; the meaning of language in context. Branch of language study phonology; phonetics graphologymorphologysyntax; grammarlexical analysis; lexicology semanticspragmatics; discourse analysisThese basic levels of language can be identified and teased out in the stylistic analysis of text, which in turn makes the analysis itself more organised and principled, more in keeping so to speak with the principle of the three Rs. However, what is absolutely central to our understanding of language (and style) is that these levels are inter-connected: they interpenetrate and depend upon one another, and they represent multiple and simultaneous linguistic operations in the planning and production of an utterance. Consider in this respect an unassuming (hypothetical) sentence like the following:(1) That puppy's knocking over those potplants!In spite of its seeming simplicity of structure, this thoroughly innocuous sentence requires for its production and delivery the assembly of a complex array of linguistic components. First, there is the palpable physical substance of the utterance which, when written, comprises graphetic substance or, when spoken, phonetic substance. This-6INTRODUCTION'raw' matter then becomes organised into linguistic structure proper, opening up the levelof graphology, which accommodates the systematic meanings encoded in the writtenmedium oflanguage, and phonology, which encompasses the meaning potential of thesounds of spoken language. In terms of graphology, this particular sentence is written inthe Roman alphabet, and in a 10 point emboldened 'palatino' font. However, as if to echoits counterpart in speech, the sentence-final exclamation mark suggests an emphatic styleof vocal delivery. In that spoken counterpart, systematic differences in sound sort out themeanings of the words used: thus, the word-initial Inl sound at the start of 'knocking' willserve to distinguish it from, say, words like 'rocking' or 'mocking'. To that extent, thephoneme Inl expresses a meaningful difference in sound. The word 'knocking' also raisesan issue in lexicology: notice for instance how contemporary English pronunciation nolonger accommodates the two word-initial graphemes <k> and <n>that appear in thespelling of this word. The <kn> sequence - originally spelt <en> - has become a singleInl pronunciation, along with equivalent occurrences in other Anglo-Saxon derived lexisin modern English like 'know' and 'knee'. The double consonant pronunciation ishowever still retained in the vocabulary of cognate languages like modern Dutch; as in'knie' (meaning 'knee') or 'knoop' (meaning 'knot').Apart from these fixed features of pronunciation, there is potential for significantvariation in much of the phonetic detail of the spoken version of example (1). Forinstance, many speakers of English will not sound in connected speech the 't's of both'That' and 'potplants', but will instead use 'glottal stops' in these positions. This is largelya consequence of the phonetic environment in which the 't' occurs: in both cases it isfollowed by a Ipl consonant and this has the effect of inducing a change, known as a'secondary articulation', in the way the 't' is sounded (Ball and Rahilly 1999: 130).Whereas this secondary articulation is not necessarily so conditioned, the social orregional origins of a speaker may affect other aspects of the spoken utterance. A majorregional difference in accent will be heard in the realisation of the historic <r> - a featureso named because it was once, as its retention in the modern spelling of a word like 'over'suggests, common to all accents of English. Whereas this /rl is still present in Irish and inmost American pronunciations, it has largely disappeared in Australian and in mostEnglish accents. Finally, the articulation of the 'ing' sequence at the end of the word'knocking' may also vary, with an 'in' sound indicating a perhaps lower status accent oran informal style of delivery.The sentence also contains words that are made up from smaller grammatical con-stituents known as morphemes. Certain of these morphemes, the 'root' morphemes, canstand as individual words in their own right, whereas others, such as prefixes andsuffixes, depend for their meaning on being conjoined or bound to other items. Thus,'potplants' has three constituents: two root morphemes ('pot' and 'plant') and a suffix (theplural morpheme's'), making the word a three morpheme cluster. Moving up frommorphology takes us into the domain of language organisation known as the grammar, ormore appropriately perhaps, given that both lexis and word-structure are normallyincluded in such a description, the lexico-grammar.Grammar is organised hierarchicallyaccording to the size of the units it contains, and most accounts of grammar wouldrecognise the sentence as the largest unit, with the clause, phrase,STYLISTICS AND LEVELS OF LANGUAGE 7 word and morpheme following as progressively smaller units (see further A3). Much could be said of the grammar of this sentence: it is a single 'clause' in the indicative declarative mood. It has a Subject ('That puppy'), a Predicator ("s knocking over') and a Complement ('those potplants'). Each of these clause constituents is realised by a phrase which itself has structure. For instance, the verb phrase which expresses the Predicator has a three part structure, containing a contracted auxiliary '[i]s', a main verb 'knocking' and a preposition 'over' which operates as a special kind of extension to the main verb. This extension makes the verb a phrasal verb, one test for which is being able to move the extension particle along the sentence to a position beyond the Complement ('That puppy's knocking those potplants over!').A semantic analysis is concerned with meaning and will be interested, amongst other things, in those elements of language which give the sentence a 'truth value'. A truth value specifies the conditions under which a particular sentence may be regarded as true or false. For instance, in this (admittedly hypothetical) sentence, the lexical item 'puppy' commits the speaker to the fact that a certain type of entity (namely, a young canine animal) is responsible for the action carried out. Other terms, such as the superordinate items 'dog' or even 'animal', would still be compatible in part with the truth conditions of the sentence. That is not to say that the use of a more generalised word like, say, 'animal' will have exactly the same repercussions for the utterance as discourse (see further below). In spite of its semantic compatibility, this less specific term would implicate in many contexts a rather negative evaluation by the speaker of the entity referred to. This type of implication is pragmatic rather than semantic because it is more about the meaning of language in context than about the meaning oflanguage per se. Returning to the semantic component of example (1), the demonstrative words 'That' and 'those' express physical orientation in language by pointing to where the speaker is situated relative to other entities specified in the sentence. This orientational function of language is known as deixis(see further A7). In this instance, the demonstratives suggest that the speaker is positioned some distance away from the referents 'puppy' and 'potplants'. The deictic relationship is therefore 'distal', whereas the parallel demonstratives 'This' and 'these' would imply a 'proximal' relationship to the referents.Above the core levels of language is situated discourse. This is a much more open-ended term used to encompass aspects of communication that lie beyond the organisation of sentences. Discourse is context-sensitive and its domain of reference includes pragmatic, ideological, social and cognitive elements in text processing. That means that an analysis of discourse explores meanings which are not retrievable solely through the linguistic analysis of the levels surveyed thus far. In fact, what a sentence 'means' in strictly semantic terms is not necessarily a guarantor of the kind of job it will do as an utterance in discourse. The raw semantic information transmitted by sentence (1), for instance, may only partially explain its discourse function in a specific context of use. To this effect, imagine that (1) is uttered by a speaker in the course of a two-party interaction in the living room of a dog-owning, potplantowning addressee. Without seeking to detail the rather complex inferencing strategies involved, the utterance in this context is unlikely to be interpreted as a disconnected remark about the unruly puppy's behaviour or as a remark which requires simply a-8INTRODUCTIONverbal acknowledgment. Rather, it will be understood as a call to action on the part of theaddressee. Indeed, it is perhaps the very obviousness in the context of what the puppy isdoing vis-it-vis the content of the utterance that would prompt the addressee to lookbeyond what the speaker 'literally' says. The speaker, who, remember, is positioneddeictically further away from the referents, may also feel that this discourse strategy isappropriate for a better-placed interlocutor to make the required timely intervention. Yetthe same discourse context can produce any of a number of other strategies. A lessforthright speaker might employ a more tentative gambit, through something like 'Sorry,but I think you might want to keep an eye on that puppy .. .'. Here, indirection serves apoliteness function, although indirection of itself is not always the best policy in urgentsituations where politeness considerations can be over-ridden (and see further thread 9).And no doubt even further configurations of participant roles might be drawn up toexplore what other discourse strategies can be pressed into service in this interactivecontext.SummaryThe previous sub-unit is no more than a thumbnail sketch, based on a single illustrativeexample, of the core levels of language organisation. The account of levels certainlyoffers a useful springboard for stylistic work, but observing these levels at work intextual examples is more the starting point than the end point of analysis. Later threads,such as 6 and 7, consider how patterns of vocabulary and grammar are sorted accordingto the various functions they serve, functions which sit at the interface betweenlexico-grammar and discourse. Other threads, such as 10 and 11, seek to take someaccount of the cognitive strategies that we draw upon to process texts; strategies thatreveal that the composition of a text's 'meaning' ultimately arises from the interplaybetween what's in the text, what's in the context and what's in the mind as well. Finally, itis fair to say that contemporary stylistics ultimately looks towards language as discourse:that is, towards a text's status as discourse, a writer's deployment of discourse strategiesand towards the way a text 'means' as a function of language in context. This is not for amoment to deny the importance of the core levels of language - the way a text isconstructed in language will, after all, have a crucial bearing on the way it functions asdiscourse.The interconnectedness of the levels and layers detailed above also means there is nonecessarily 'natural' starting point in a stylistic analysis, so we need to be circumspectabout those aspects of language upon which we choose to concentrate. Interactionbetween levels is important: one level may complement, parallel or even collide withanother level. To bring this unit to a close, let us consider a brief illustration of howstriking stylistic effects can be engendered by offsetting one level of language againstanother. The following fragment is the first three lines of an untitled poem by MargaretAtwood:You are the sunin reverse, allenergy flows intoyou ...(Atwood 1996: 47)GRAMMAR AND STYLE 9At first glance, this sequence bears the stylistic imprint of the lyric poem. This literary genre is characterised by short introspective texts where a single speaking voice expresses emotions or thoughts, and in its 'love poem' manifestation, the thoughts are often relayed through direct address in the second person to an assumed lover. Frequently, the lyric works through an essentially metaphorical construction whereby the assumed addressee is blended conceptually with an element of nature. Indeed, the lover, as suggested here, is often mapped onto the sun, which makes the sun the 'source domain' for the metaphor (see further thread 11). Shakespeare's sonnet 18, which opens with the sequence 'Shall I compare thee to a summer's day?', is a wellknown example of this type of lyrical form.Atwood however works through this generic convention to create a startling reorientation in interpretation. In doing so, she uses a very simple stylistic technique, a technique which essentially involves playing off the level of grammar against the level of graphology. Ending the first line where she does, she develops a linguistic trompe l'oeil whereby the seemingly complete grammatical structure 'You are the sun' disintegrates in the second line when we realise that the grammatical Complement (see A3) of the verb 'are' is not the phrase 'the sun' but the fuller, and rather more stark, phrase 'the sun in reverse'. As the remainder of this poem bears out, this is a bitter sentiment, a kind of 'anti-lyric', where the subject of the direct address does not embody the all-fulfilling radiance of the sun but is rather more like an energysapping sponge which drains, rather than enhances, the life-forces of nature. And while the initial, positive sense engendered in the first line is displaced by the grammatical 'revision' in the second, the ghost of it somehow remains. Indeed, this particular stylistic pattern works literally to establish, and then reverse, the harmonic coalescence of subject with nature.All of the levels of language detailed in this unit will feature in various places around this book. The remainder of this thread, across to a reading in D2 by Katie Wales, is concerned with the broad resources that different levels of language offer for the creation of stylistic texture. Unit B2 explores juxtapositions between levels similar in principle to that observed in Atwood and includes commentary on semantics, graphology and morphology. In terms of its vertical progression, this section feeds into further and more detailed introductions to certain core levels of language, beginning below with an introduction to the level of grammar.Stylistics, Paul Simpson, 2004。

谈论文学要知道哪些英语单词

谈论文学要知道哪些英语单词谈论文学要知道哪些英语单词文学是以语言文字为工具,形象化地反映客观现实、表现作家心灵世界的艺术,包括诗歌、散文、小说、剧本、寓言童话等,是文化的重要表现形式,以不同的形式即体裁,表现内心情感,再现一定时期和一定地域的社会生活。

文学就在我们生活里。

但你和外国人谈论文学时,一定要知道下面这些英语单词。

1).author n.作者,作家The author of this novel must be a detective这本小说的作者一定是一个侦探。

2).write v.书写,写作If you miss me, please write letters to me如果你念我,就请给我写信。

3).literature n.文学,文学作品As far as literature is concerned.I am very fond of classics就文学作品而言,我很喜欢古典作品。

4).work n.作品If my memory serves me right, the famous sonnet is Shakespeare's work如果我没记错的话,这首著名的十四行诗是莎士比亚的作品。

5).stylistics n.文体学,风格学Stylistics is a branch of linguistics文体学是语言学的一个分支。

6).poetry n.诗歌,诗集l often recite poetry as possible as I can in my spare time在我有空时,我经常尽可能的多背诗。

7).antithesis n. 对句,对偶The foreign friend is puzzled about the antithesis那个外国朋友看不懂对句。

8).verse n.诗,韵文From whom did you quote these verses?你从谁那里引用了这些诗句?9).ballad n.歌谣,民谣My mother likes ballads while I like pop music我妈妈喜欢民谣,但是我喜.欢流行音乐。

Stylistics

D. Onomatopoeia

cuckoo,meow,moo The actress was hissed off the stage.

Page 15

2. Graphological features

• • • • Punctuation, capitalization, italicizing, Format of printing • paragraphing, • Spacing • Graphic signs • Spelling (misspelling) (Sight poetry )

Page 6

• a grief ago • The phrase violates two rules of English: a) the indefinite article clashes syntactically with the uncountable noun grief, because it normally modifies a countable one; b) the postmodifying adverb ago clashes semantically with the head word grief, for it usually is able to modify a noun to do with time. But grief is a word which expresses emotion. The highly deviant nature of the phrase

Page 13

C. Repetition of sounds

(1) alliteration: repetition of initial sounds • He clasps the crag with crooked hands ---- Alfred Tennyson: The Eagle (2) assonance: the use of the same, or related, vowel sounds in successive words. • Try to light the fire. • fleet feet sweep by sleeping Greeks. • Hayden plays a lot. (3) consonance: the repetition of the last consonants of the stressed words at the end of the lines (slant rhyme or half rhyme) • After a hundred years, /Nobody knows the place --/Agony, that enacted there, /Motionless as peace. (4) rhyme:

Stylistics

现代文体观(2):ห้องสมุดไป่ตู้离观

Style as deviations from the norm 偏离的方式: 数量 性质 偏离的理据: 偏离(deviation)和陌生化 (defamiliarization)突出 (foregrounding)

Development

Diachronic study Synchronic study

• STYLE?

Different definitions of style

Style as form (Aristotle) Style as eloquence (Cicero) Style is the man. (Buffon) Style as personal idiosyncrasy (Murry)

Scholars’ views on stylistics (2)

• Crystal & Davy (1969): Investing English Style [M] : 宏观方面,风格指的是在某时间或某一时期内,由某一群人共 享的语言习惯(Crystal & Davy, 1990:1-10)。

1. 2. 3.

4. 5.

• STYLISTICS?

Scholars’ views on stylistics (1) • Widdowson: By stylistics, I mean the study of literary discourse from a linguistic orientation and I shall take the view that what distinguishes stylistics from literary criticism on the one hand and linguistics on the other is that it is essentially a means of linking the two (1975: 3). • Leech: the study of the use of language in literature(1969:1), stylistics is a meeting ground of linguistics and literary study(ibid,2).

stylistics文体学英文定义

stylistics文体学英文定义Stylistics is a branch of linguistics that focuses on the study of style in language. It is concerned with the analysis and interpretation of the linguistic features that contribute to the distinctive character of a text or a speaker's language use. Stylistics examines how language is used in different contexts and for different purposes, and how these choices can convey meaning and create particular effects.The study of stylistics involves the examination of various linguistic elements, such as vocabulary, grammar, syntax, and rhetoric, and how they are used to create a particular style or tone. Stylistics also considers the role of context, including the social, cultural, and historical factors that influence language use.One of the key aspects of stylistics is the concept of foregrounding, which refers to the use of linguistic features that draw attention to themselves and create a sense of prominence or emphasis. This can be achieved through the use of unusual or unexpected language, such as metaphors, alliteration, or unusual sentence structures.Stylistics also considers the relationship between form and content, and how the way language is used can shape the meaning andimpact of a text. For example, the use of formal or informal language, the choice of vocabulary, and the structure of sentences can all contribute to the overall tone and effect of a piece of writing.Another important aspect of stylistics is the analysis of literary texts, where the focus is on the distinctive linguistic features that contribute to the style and meaning of a work of literature. This can include the examination of narrative techniques, such as point of view and characterization, as well as the use of figurative language, symbolism, and other literary devices.Stylistics can also be applied to other forms of communication, such as speech, advertising, and political discourse. In these contexts, the analysis of style can reveal insights into the speaker's or writer's intentions, the target audience, and the broader cultural and social context in which the language is being used.One of the key challenges in the study of stylistics is the need to balance the objective analysis of linguistic features with the subjective interpretation of their meaning and effect. Stylistic analysis often requires a deep understanding of language, as well as a keen eye for detail and a willingness to engage with the nuances and complexities of language use.Despite these challenges, the study of stylistics remains an importantand influential field within linguistics. By examining the ways in which language is used to create meaning and effect, stylistics can provide valuable insights into the nature of language and communication, and can contribute to a deeper understanding of the human experience.。

语言学:语言与文学 名词解释

英语语言学:语言与文学language and literatureStylistics(文体学):概念:it is the study of the ways in which meaning is created through language in literature as well as other types of text.来源:it may date back to the focus on the style of oral expression,which was cultivated in rhetoric following the tradition of Aristotle’s Rhetoric. Yet the real flourishing of stylistics,was seen in Britain and the United States in the 1960s,and was largely spurred by works done in the field by Russian Formalism such as Roman Jackobson and victor Shklovsky.现在的研究方法和内容:Scholars use linguistic models,theories and frameworks as their analytical tools in order to describe and explain how and why a text works as it does,and how we come from the words on the page.Style (文体)概念:It is defined as variation of language usage.It is the way in which language is used in given context,by a given person,for a given purpose,and so on.Also,style is a motivated choice from the set of language or register conventions (语域惯例)or other social,political,cultural and contextual parameters.来源It has been recognized since the days of ancient rhetoric.注:register:It refers to a language variety which is used by a particular group of people who share the same occupation.Literary stylistics文学文体学:概念:It mainly deals with the close relationship between language and literature.It focuses on the study of linguistic features related to literary style.Foregrounding前景化,now a popular term on stylistics,was made use of on literary studies by the Russian formalists,Prague School scholars,and modern stylisticians.It explains the idea that as things become familiar to us,we stop noticing them.来源:It ,originally coming from visual arts and in contrast with backgrounding,is closely related to the Russian formalist concept of defamiliarization which was introduced into literary criticism by Shklovsky.。

英语文体学教案

第一章1.1 Definition of StylisticsStylistics has long been considered as a highly significant but very discussible branch of learning. It is concerned with various disciplines such as linguistics, semantics, pragmatics and literature. The word stylistics( ‘styl’ component relates stylistic to literary criticism, and the ‘istics’ component to linguistics). So stylistics is the bridge of linguistics and literature. Stylistics is the study of literary discourse from a linguistic orientation.” (文体学是从语言学的角度研究文学语篇)Stylistics is an interdisciplined branch of learning which studies various differences between formal and informal, between deviant and normal, between magnificent and plain, between professional and popular, between foreign and domestic, between this and that individual.1.2 The Development of StylisticsThe date when stylistics became a field of academic inquiry is difficult to determine. However stylistics is often considered as both an old and a young branch of learning. It is old, because it orig inated from the ancient “rhetoric”. The famous ancient Greek philosophers Socrates, Plato and Aristotle all contributed a lot to this branch of learning. It is young ,because the word “stylistics” first appeared only in 1882, and the first book on stylistics was written by a French scholar Charles Bally in 1902 and was published in 1909: Traite de Stylistique Francaise. This book is often considered as a landmark of modern stylistics. Consequently, a number of more coherent and systematic works of both a theoretical and a practical nature were published in the field.The subject of study in Bally’s time was oral discourse. Bally considered that apart from the denotative meaning expressed by the speaker4, there was usually an “overtone” which indicated differ ent “feelings”, and the task of stylistics was to find out the linguistic devices indicating these feelings.Later , the German scholar L.Spitzer(1887-1960), began to analyze literary works from a stylistic point of view, and therefore, Spitzer if often co nsider4ed as the “father of literary stylistics”.From the beginning of the 1930s to the end of the 1950s stylistics was developing slowly and was only confined to the European continent. From the end of the 1950s to the present time, modern stylistics has reached its prosperity.1.3 Definitions of StyleSo style is an integral part of meaning. It gives us additional information about the speaker’s/writer’s regional and social origin, education, his relationship with the his/her reader, his feelings, emotions or attitudes. Without a sense of style we cannot arrive at a better understanding of an utterance1).Written---spoken in terms of channel2)The Differences between Formal and Informal Language3)modern----archaic in terms of time4)normal----deviated in terms of degree of novelty5). common---professional in terms of technique(专业)Homework:1.What’s stylistics?2.What does stylistics study?3.Say something about the development of stylistics.4.Give examples to explain “Proper words in proper places makes the true definition of a style.”5.What does style study?6.Give example to illustrate the differences between spoken-- written,formal–informal, modern–archaic, norm—deviated, common---professional.第二章1. Definition of meanings of meaningAccording to Leech (1974 English linguists), meanings of meaning can be broken into seven kinds:1).Denotative meaningIt refers to literal meaning, refers to diction meaning.(super meaning) 词的概念意义。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

Page 9

1. Phonological features

• Mispronunciation and Sub-standard Pronunciation

The trumpet of a prophecy! O, Wind, If winter comes, can spring be far behind?

(“Ode to the West Wind”)

Page 13

C. Repetition of sounds

(1) alliteration: repetition of initial sounds • He clasps the crag with crooked hands

• There are two types of caesurae: masculine and feminine. A masculine caesura is a pause that follows a stressed syllable; a feminine caesura follows an unstressed syllable.

Page 14

D. Onomatopoeia

cuckoo,meow,moo The actress was hissed off the stage.

Page 15

2. Graphological features

• Punctuation, • capitalization, • italicizing, • Format of

printing • paragraphing, • Spacing • Graphic signs • Spelling

(misspelling) (Sight poetry )

Page 16

Graphology refers to the writing system of a language. It studies symbols which are distinctive such as Graphological deviation can occur in any sub-area of graphology, such as the shape of the text, the type of print, grammetrics, punctuation, indentation, etc.

Page 7

Linguistic levels for stylistic analysis

• Phonological features (phonological deviation)

• Graphological features (graphonological deviation)

• Lexical features (lexical deviation) • Syntactic features (syntactic deviation) • Semantic features (semantic deviation)

stressed words at the end of the lines (slant rhyme or half rhyme) • After a hundred years, /Nobody knows the place --/Agony, that enacted there, /Motionless as peace. (4) rhyme:

Page 2

What is stylistics?

• Stylistics is the "study of the use of language in literature"

• Stylistics is a "meeting-ground of linguistics and literary study"

similar sounds between two or more words) • Rhyme (repetition of identical end sounds) • Rhythm (flow of sounds and their rise and fall,

and their accents and pauses) • Pause (brief interruption of the articulatory

e.g. I’m jist a reg’lar mountaineer jedge. (“The Trial that Rocked the World”)

Page 12

B. Special Pronunciation

• For convenience of rhyming, the poet may give special pronunciation to certain words, e.g.

• Type of print

Page 17

•Spacing

perceived by a listener)

Page 10

• Caesura

• In meter, caesura is a term to denote an audible pause that breaks up a line of verse. In most cases, caesura is indicated by punctuation marks which cause a pause in speech: a comma, a semicolon, a full stop, a dash, etc. Punctuation, however, is not necessary for a caesura to occur.

Page 6

• a grief ago • The phrase violates two rules of English: a)

the indefinite article clashes syntactically with the uncountable noun grief, because it normally modifies a countable one; b) the postmodifying adverb ago clashes semantically with the head word grief, for it usually is able to modify a noun to do with time. But grief is a word which expresses emotion. The highly deviant nature of the phrase

Page 3

Procedure of stylistic analysis:

• The components and the procedure of stylistic analysis. A stylistic analysis involves description, interpretation and evaluation. When discussing components of literary criticism, Short has pointed out: "the three parts are logically ordered: Description ← Interpretation ← Evaluation"

• Stylistics is an area of study which straddles two disciplines: literary criticism and linguistics. It takes literary discourse (text) as its object of study and uses linguistics as a means to that end.

• To err is human; || to forgive, divine.

Page 11tandard

Pronunciation

• In order to vividly describe a character, the literary writer may choose to let his character mispronounce certain words or simply pronounce them in sub-standard ways.

---- Alfred Tennyson: The Eagle (2) assonance: the use of the same, or related, vowel

sounds in successive words. • Try to light the fire. • fleet feet sweep by sleeping Greeks. • Hayden plays a lot. (3) consonance: the repetition of the last consonants of the

Page 4

Three views on style:

• Style as Deviance • Style as Choice • Style as Foregrounding

Page 5

Style as deviance

• the distinctiveness of a literary text resides in its departure from the characteristics of what is communicatively normal.