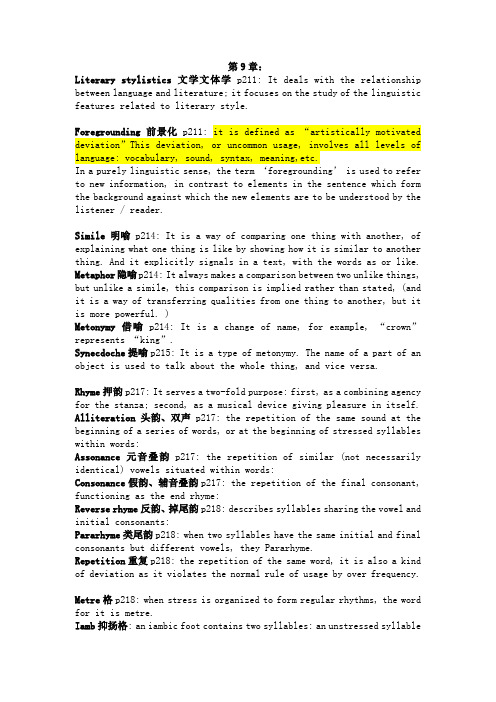

语言学讲义 考研 9 Stylistics

语言学C9-1

2002.12.1

Chapter 9 Stylistics

13Βιβλιοθήκη YAR CAUC9.2.3 The analysis of literary language

• Literary texts can be analyzed in various ways. • Some of the following procedures may be of help in analyzing the grammatical structure and meaning of the text. • 1) Foregrounding on the level of lexis (word) • 2) Foregrounding on the level of word order and syntax • 3) On the grammatical level, analyze the structure of sentences • 4) In all cases, be aware of the systems of the language, identify the more "deviant”,“marked" or literary structures.

•

2002.12.1 Chapter 9 Stylistics 9

YAR CAUC

1) Simile (明喻)

• A SIMILE is a way of comparing one thing with another.

2002.12.1

Chapter 9 Stylistics

10

YAR CAUC

2) Metaphor (隐喻)

• A METAPHOR also makes a comparison between two unlike elements; but unlike a simile, this comparison is implied rather than stated.

Stylistics中文文体学课件

3. I ‘m finding out that a lot of what I thought had been bonfired, Oxfam-ed, used for land-fill, has in fact been tidied away in sound archives, stills libraries, image banks, memorabilia mausoleums, tat troves, mug morgues.

Cf. A. The police are investigating the case of

murder. B. The police are looking into the case of

murder. (Lexically, Latin, French, Greek words are generally used in formal style; Words from old English are mostly used in informal style.)

F: He left early in order not to miss the train.

F: He left early in order that he would not miss the train.

6. 问句:

F: When are you going to do it?

IF: When

place all the same.

F: He endeavoured to prevent the marriage ; however, they married notwithstanding. 3. 非正式文体常用副词做状语;而正式文体常 用由介词和与该副词同根的词够成的介词短 语:

Rhetoric and Stylistics (9)

6) Stress 重音 Word stress & sentence stress --Word stress. In a word or expression, difference in stress may create difference in words or meaning. See p. 12. --Sentence stress. John bought that new car yesterday. (In a falling tone) (1) John stressed means not anybody else; bought it instead of stealing it.

2. Pun It is a figure depending on a similarity of sound and a disparity of meaning. It is play on words, the form and meaning of words, for a witty or humorous effect.

(4) Car stressed means not other vehicles; (5) Yesterday stressed may mean: …but it does not work properly today /…not the day before/…but he acts as if he had had it for a long time.

8)Tempo 语速 Speed of utterance. Speed of utterance conveys meanings. A slow tempo is related to special care and seriousness whereas a fast tempo suggests dismissal or cheerfulness. When a speaker is excited or impatient, he/she tends to speak at a quicker tempo. When hesitant, doubtful, or low-spirited, he/she tends to slow down. e.g.

stylistics

World-builders: t soon after they had left Ramandu’s country. l near the edge of the world c Edmund, Lucy, Drinian, Caspian and the crew o ship ,sun, birds, Aslan’s Table. Function- advancers they began to feel

Example of analysis by text world theory

A simple text: Very soon after they had left Ramandu’s country they began to feel that they had already sailed beyond the world. All was different. For one thing they all found that they were needing less sleep. One did not want to go to bed nor to eat much, nor even to talk except in low voices. Another thing was the light. There was too much of it. The sun when it came up each morning looked twice, if not three times, its usual size. And every morning (which gave Lucy the strangest feeling of all) the huge white birds, singing their song with human voices in a language no one knew, streamed overhead and vanished astern on their way to their breakfast at Aslan’s Table. A little later they came flying back and vanished into the east. (The Voyage of the Dawn Treader, C.S. Lewis)

英语语言学胡壮麟09Chapter 9_literature

Syntactical Level 1 Sentence Types According to different criteria, the English sentences can be classified into different types, and they each manifest distinctive stylistic features and are suitable for different ideas expressed.

Chapter 9 Language and Literature

9.1 three definitions of style

Style: Style as deviation, style is regarded as deviation or deviance, i.e. departure from what is normal. E.g. a grief ago, generally we use a noun indicating time in the expression “ a ago”, such as a month ago and the word to fill the slot is normally a countable noun. In this phrase, grief doesn’t meet the conventional requirement. It express an idea in a beautifully succinct way. Since grief means a feeling of great sadness and any feeling will last for some time, it is not difficult to figure out the message. That is , sth terribly sad has happened, and the speaker may have experienced grief repeatedly so that he can measure time in terms of it.

Stylistics 中文

些)等。

IF: A wolf, after all, is a wolf though it has artful disguises. F: A wolf, after all, is a wolf in spite of (despite) it has artful disguises.

3. IF: He tried to prevent the marriage but it took place all the same. F: He endeavoured to prevent the marriage ; however, they married notwithstanding. 3. 非正式文体常用副词做状语;而正式文体常 用由介词和与该副词同根的词够成的介词短 语: IF: He spoke confidently. F: He spoke in a confident manner. F: He spoke with confidence.

Syntactically, more verb phrases are used in

informal style while single verbs of equivalent meaning are used in formal style. IF : The criminals finally turned themselves in. F: The criminals finally surrendered. IF: I can’t put up with your bad manners. F: I cannot tolerate your bad manners. IF: He tried to make good use of his abilities in the new job. F: He endeavoured to utilize his abilities in the new position.

Stylistics 9

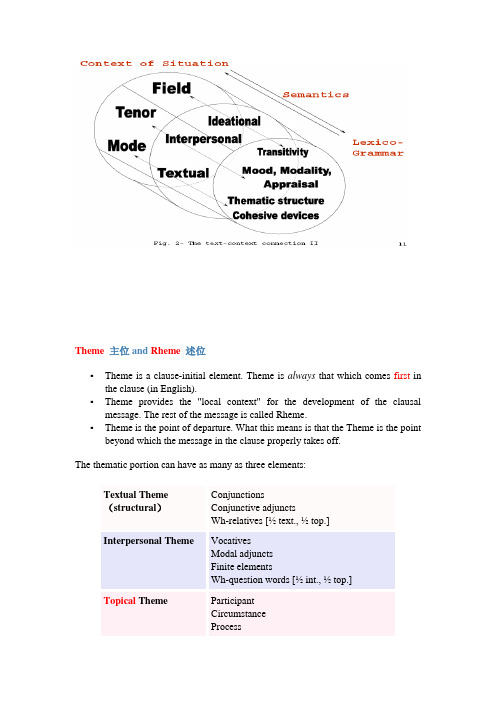

Theme 主位and Rheme述位▪Theme is a clause-initial element. Theme is always that which comes first in the clause (in English).▪Theme provides the "local context" for the development of the clausal message. The rest of the message is called Rheme.▪Theme is the point of departure. What this means is that the Theme is the point beyond which the message in the clause properly takes off.The thematic portion can have as many as three elements:Textual Theme (structural)ConjunctionsConjunctive adjunctsWh-relatives [½ text., ½ top.]Interpersonal Theme VocativesModal adjunctsFinite elementsWh-question words [½ int., ½ top.] Topical Theme ParticipantCircumstanceProcessWhere Theme stops and Rheme starts. Here is the golden rule:In the clause, you start at the beginning and keep on searching until you find the Topical Theme. Once you've done that, you have your Thematic portion.Everything else after the topical Theme is the Rheme. The Thematic portion, therefore, is everything from the start of the clause up to and including the Topical Theme (unmarked).However, you'll need to make an exception where marked Themes are concerned.It is possible for the thematic portion to contain more than one topical Theme, provided all the topical Themes in the thematic portion are marked. More on this later.Let's start at the beginning of the clause. If you encounter any of the following: ▪Continuatives (eg, umm, yeah, ...)▪Conjunctions (eg, and, or, but)▪Conjunctive adjuncts (eg, however, therefore, because, ...)▪Wh-relative (eg, that, which, who, ...)label them as Textual Themes.As indicated in the table above, make a slight exception for wh-relatives. They are both textual and topical Theme rolled into one. Going by the golden rule, if you have a clause initiated by a wh-relative (which is both a textual and topical Theme), everything else after the wh-relative would be Rheme. For example:The official, « whoTxt/Top Theme slept on a meeting, »Rhemelost his job.If you encounter the following:▪Vocatives (eg, Henry!, Sir!, ...)▪Modal adjuncts, including mood and comment adjuncts (eg, probably, usually, frankly, ...)▪Finite operators (eg, modal auxiliaries, 'be' auxiliary, ...)▪Wh-question word (eg, who, what, where, how, why)label them as Interpersonal Themes.Again, make an exception for wh-question words. These are both interpersonal and topical Themes squeezed into one. Example:WhyInt/Top Theme did the official sleep? RhemeFinally, label the first participant (usually NG), circumstance (usually PP or AdvG), or process (VG) as Topical Theme. Once you've done that, you have your thematic portion of the clause. Here's a simple example with all three types of Themes:Well, Txt Sir,IntwhyInt/Topdo you sleep on my meeting?RhemePlease note that topical Themes are obligatory for all clauses. The other Theme types (textual and interpersonal) are optional. This means that, sometimes, you may even need to recover ellipsed elements in analysis. For example, in:Superman bit Mr Bean, and was sorry about it.We have two clauses, the topical Theme of the first clause is "Superman". The second clause’s topical Theme is ellipsed “he”:andTxt (Top) was sorry about it RhemeUnmarked非标记的& marked 标记的ThemesBy markedness is meant that the occurrence of some phenomenon is less typical or frequent. Hence, when we say that a Theme is marked, we are saying that it is less typical or frequent for it to be realised that way. And the opposite for unmarked Themes. And, whenever we talk about marked or unmarked Themes, we are referring only to the topical Theme, not the textual or interpersonal Theme.Let's now see what the unmarked Themes are like for different clausal moods:Declaratives:The unmarked Theme is the subject, as in: "Snow White picked her nose everyday." All other realisations of topical Themes are marked, for example: "Her nose, she loves to pick" (here, the complement, rather than the subject, is the topical Theme).Interrogatives:For interrogatives, we need to separate polar from content interrogatives:▪▪Content:The unmarked Theme is the wh-question word, as in: "Why did Snow White pick her nose?" All other realisations are marked. Imperatives:Like interrogatives, we also need to make a distinction between two types of imperatives -- inclusive and exclusive imperatives.▪Inclusive:The unmarked Theme is us, which is actually thewayward form of the subject (= we): pick our noses!" All other realisations are marked.▪Exclusive: The unmarked Theme is the process: "Pick your nose!" All other realisations are marked.Topical Themes realised by circumstantial elements are marked.Not all marked Themes, however, are the same. They differ in terms of the extent of markedness. Compare: which one is more marked?Noses, she loves to pick.In the evenings, she loves to pick noses.Multiple marked ThemesRemember the golden rule above? Now, consider the sentence below:Yesterday, with the computer, late into midnight, I prepared my presentation.If we go strictly by the golden rule, then only Yesterday would be analysed as the topical Theme. The rest of the clause, from with the computer onwards, would be the Rheme. But this doesn't seem quite correct. Some linguists, such as Martin (1995), have proposed a more intuitively appealing approach, by regarding all marked Themes in such instances as topical Themes. If so, the thematic portion in this sentence wouldn’t simply be Yesterday, but Yesterday, with the computer, late into midnight. Such an approach makes sense in terms of the broader characterization of Theme as the point of departure, since the additional marked Themes function to lay the ground and prepare for the message within the clause to properly take off. This is the only exception to the golden rule.One last thingTopical Themes are obligatory only for finite clauses and imperatives. NF clauses can be without topical Themes due entirely to their structural compactness. Look out, though, for the subject in NF clauses. If it's there, you have a topical Theme, but not otherwise. So in the first clause of "//after hearing how loudly//he sang//", we have only a textual Theme (after), but no topical Theme. On the other hand, the NF clause "his singing having hurt their eardrums ..." has a topical Theme (his singing).Given+New and Theme+RhemeThe information structure and the thematic structure are closely related. Normally, a speaker will locate the Given information in Theme and the climax of New information in Rheme. If not, we have a marked information structure.Unmarked:A: I slept on the meeting yesterday.B: You will be fired.Marked:A: Sleeping on a meeting will cause a dismissal.B: Then I will be fired.In the textIn looking at the thematic progression of the text, it is usual to look at the topical Themes of the main clauses only. [Why? That's because subordinate clauses are always dependent on the main clause and add little to the main idea(s) of structure the text.]How do the Themes of clauses progressed through the text? There are various patterns of thematic progression (TP). The first two are more common:Theme Iteration:I am a student.I attend school everyday.I like study.I prefer physics especially.Theme Development:Yesterday I went to the bookshop.I bought a novel.It is about WWII.Rheme Iteration:John respects Margaret.I also admire her enormously.Everyone, in fact, wants to emulate her.Rheme Regression:John got a full mark in exam.But Rose accused him of cheating.No one, fortunately, takes Rose seriously.Theme Iteration:I am a student.I attend school everyday.I like study.I prefer physics especially.Theme Development:Yesterday I went to the bookshop.I bought a novel.It is about WWII.Rheme Iteration:John respects Margaret.I also admire her enormously.Everyone, in fact, wants to emulate her. Rheme Regression:John got a full mark in exam.But Rose accused him of cheating.No one, fortunately, takes Rose seriously.Group work: Do a T-P analysis on the following text and improve its cohesion by revising Theme-Rheme organization:Should Private Schools be Encouraged in China?First of all, let’s have a clear picture of the general condition of China’s education. Now, China still has very low level of education. Compared with a large population of students, schools are very insufficient in China. Students can be provided with more chances to receive education by private schools. Secondly, the country’s heav y burden can be relieved by private schools. Different from public schools, private schools are supported by individuals. Therefore the country does not take the responsibility of giving the financial support to these private schools. Furthermore the taxes paid by the private schools can benefit the country. Money gained from these private schools can be put in developing our country’s education.Should Private Schools be Encouraged in China (original)First of all, let’s have a clear picture of the general condition of China’s education. Now, China still has very low level of education. Compared with a large population of students, schools are very insufficient in China. Students can be provided with more chances to receive education by private schools. Secondly, the country’s heav y burden can be relieved by private schools. Different from public schools, private schools are supported by individuals. Therefore the country does not take the responsibility of giving the financial support to these private schools. Furthermore the taxes paid by the private schools can benefit the country. Money gained from these private schools can be put in developing our country’s educ ation.Should Private Schools be Encouraged in China (revised)①First of all, let’s have a clear picture of the general condition of China’s education.②Now, China’ education level is still very low. Compared with a large population of students,③schools are very insufficient in China.④Private schools can provide students with more chances to receive education.⑤Secondly, private schools can relieve the country’s heave burden. Different from public schools,⑥private schools are supported by individuals.⑦Therefore the country does not take the responsibility of giving the financial support to these private schools.⑧Furthermore the country can benefit from the taxes paid by the private schools.⑨Money gained from these private schools can be put in developing our country’s education.①Yesterday I worked with my workmates in the school library.②We were writing down the number of magazines when another workmate came.③She brought drinks for us.④Later, we began to transfer the old-fashioned magazines to the warehouse.⑤It was really a hard project.⑥We kept doing it from 3PM to 5:30PM.⑦After completing the work, we all felt tired and hot.①In recent years, China has become increasingly active in the process of regional economic integration. ②While promoting globalization China is putting more emphasis on regional, economic cooperation. ③Lately, China and the Association of South East Asian Nations are actively pushing forward the building of a free trade area. ④This free trade area is to be established in 2010. ⑤The trade valume between China and ASEAN had reached 200 billion US dollars by 2007.白狐(歌词,词作者:玉镯儿)我是一只修行千年的狐千年修行,千年孤独夜深人静时可有人听见我在哭灯火阑珊处可有人看见我在跳舞我是一只等待千年的狐千年等待,千年孤独滚滚红尘里谁又种下了爱的蛊茫茫人海中谁又喝下了爱的毒我爱你时,你正一贫如洗、寒窗苦读离开你时,你正金榜题名、洞房花烛能不能为你再跳一支舞?我是你千百年前放生的白狐你看衣袂飘飘,衣袂飘飘海誓山盟都化作虚无能不能为你再跳一支舞?只为你临别时的那一次回顾你看衣袂飘飘,衣袂飘飘天长地久都化作虚无。

语言学--unit9语言与文学Language and Literature

Dictionary definition

The world is like a stage.

The name of a

part of a

objective

to

synecdoche refer to the

whole thing.

simile Figurative language metapher

(4)

To demonstrate technical skill, and for intellectual pleasure

(5)

For emphasis or contrast

(6)

Onomatopoeia

9.3 The Language in Poety 9.3.6 How to Analyse Poetry

Ex.9-15

Trochee and palm to palm is holy palmer's kiss

Ex.9-16

Anapest Willows whiten, aspens quiver

Ex.9-17

Dactyl Without cause be he pleased, without cause be he cross

(1)

Information about the poem

(2)

The way the poem is structured

lingustics chapter 9.4 The Language

in Fiction

9.4.1 Fictional Prose and Point of View

(1) I-narrators (2)Third-person narrators (3)Schema-oriented language (4)Given vs New information (5)Deixis

语言学讲义 考研 9 Stylistics

• In addition, stylistics is a distinctive term that may be used to determine the connections between the form and effects within a particular variety of language.

5

• Other features of stylistics include the use of dialogue, including regional accents and people‘s dialects, descriptive language, the use of grammar, such as the active voice or passive voice, the distribution of sentence lengths, the use of particular language registers语域, etc.

4

• Stylistics also attempts to establish principles capable of explaining the particular choices made by individuals and social groups in their use of language, such as socialisation, the production and reception of meaning, critical discourse analysis and literary criticism.

However, in Linguistic Criticism, Roger Fowler makes the point that, in non-theoretical usage, the word stylistics makes sense and is useful in referring to an enormous range of literary contexts, such as John Milton‘s ‗grand style‘, the ‗prose style‘ of Henry James, the ‗epic‘ and ‗ballad style‘ of classical Greek literature, etc. (Fowler, 1996: 185).12题三:Chiming 谐音

语言学Chapter 9

•

9· 1 Foregrounding and grammatical form前 2· 景化和语法形式

Events belong to the string of plot are usually foregrounded while those used to provide related information are backgrounded. Deviation(偏离)and parallelism(平行) are usually used to show foregrounding events. The study of foregrounding is called patterning(模式/干扰背景模式).

Language & Literature 4

Chapter 9 Language & Literature • 9· Some general features of the literary 2 language

•

9· 1 Foregrounding and grammatical form前 2· 景化和语法形式

Language & Literature 2

Chapter 9 Language & Literature • 9· Theoretical background 1

• 研究表明: 自20世纪60年代,建立起来了现代文体学, 从此该学科就飞速发展起来。但20世纪60年代,文体 学是形式主义formalism的十年,70年代是功能主义 functionalism的十年,80年代是语篇文体学discourse stylistics的十年,那么在90年代,是社会历史sociohistorical和社会文化socio-cultural文体学。 • 2000年后,文体学的发展趋势有两个主要特征。首先, 向着社会历史和社会文化文体学的研究深入。其次, 正兴起一种多元发展plural-heads development的趋势, 不同文体学学派竞相发展,新的学派不时涌现出来。

语言学教程Chapter 9. Language and Literature

The term “foregrounding”

Definition Deviation of language involves all levels of language: vocabulary, sound, syntax, meaning, graphology,etc. Repetition is also a kind of deviation. Alliteration, parallism, and many figures of speech are the examples of foregrounding in literary language.

9.2 some general features of the literary language

Features of literary language are displayed in the following three aspects: 1. phonology 2. grammar 3. semantics Literay language differs from non-literary language in that the former is foregrounded in the above three aspects.

9.2.3 the analysis of literay language

Procedures we should follow when we analyze the grammatical structure and meaning of a literary text. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8.

Chapter 9-11-S语言学

Chapter Nine Language and LiteratureSection One Features of Literary LanguageThere is a very close relationship between language and literature. The part of linguistics that studies the language of literature is termed LITERARY STYLISTICS. It focuses on the study of linguistic features related to literary style.9.1 Theoretical backgroundOur pursuit of style, the most elusive and fascinating phenomenon, has been enhanced by the constant studies of generations of scholars. “Style”, the phenomenon, has been recognized since the days of ancient rhetoric; “stylistic”, the adjective, has been with us since 1860; “stylistics”, the field, is perhaps the creation of bibliographers. (Dolores Burton, 1990)Earlier stage: Helmut Hatzfeld was the first biographer of stylistics and his work in A Critical Bibliography of the New Stylistics (1953) was continued by Louis Milic”s andStylistics (1967), Richard Bailey and Dolores Burton’s English Stylistics (1968)and James Bennett’s A Bibliography of Stylistics and related Criticism (1986).Until Helmut Hatzfeld brought out his bibliography the word “stylistics” had notappeared in the title of any English book about style although “stylistique”hadappeared in French titles, beginning in 1905with Charles Bally’s Traite destylistique francaise. The distinction between the French “sylistique”(withimplications of a system of thought) and the English “stylistics”(with theconnotation of science) reflects the trends manifested in the grouping ofbibliographies from the more narrowly focused view of stylistics in the 1960s,when computer science and generative grammar led many to hope for more preciseways of describing their impressions of describing their impressions of style, toBennett’s bibliography which covers books published from 1967 to 1983. Establishment:1960s witnessed the firm establishment of modern stylistics and ever since then the discipline has been developing at an enormous speed. As Carter and Simpson(1989) observed, at “the risk of overgeneralization and oversimplification, wemight say that ifthe 1960s was a decade of formalism in stylistics,the 1970s a decade of functionalism andthe 1980s a decade of discourse stylistics, thenthe 1990s could well become the decade in which socio-historical and socio-cultural stylistic studies are a main preoccupation.”Present trends:the socio-historical and socio-culture studies are gaining momentum“plural-heads development”/ different schools of stylistics compete for development and new schools emerge every now and then (Shen 2000)9.2 Some general features of the literary languageWhat seems to distinguish literary from non-literary usage may be the extent to which the phonological, grammatical and semantic features of the language are salient, or foregrounded in some way. The phonological aspect will be outlined in the next section. In this section, we shall briefly discuss the grammatical and semantic aspects.9.2.1 Foregrounding and grammatical formIn literary texts, the grammatical system of the language is often made to “deviate from other, more everyday, forms of language, and as a result creates interesting new patterns in form and in meaning” (Mularovsky) by means of the use of non-conventional structures that seem to break the rules of grammar.Ex. 9—1 The 1960 dream of high rise living soon turned into a nightmare.In this sentence, there is nothing grammatically unusual or “deviant” in the way the words of the sentence are put together. However, in the following verse from a poem, the grammatical structure seems to be much more challenging, and makes more demands on our interpretative processing of these lines:Ex. 9—2 Four storeys have no windows left to smashBut in the fifth a chipped sill buttressesMother and daughter the last mistressesOf that black block condemned to stand, not crash.Ex. 9-3The red-haired woman, smiling, waving to the disappearing shore. She left the maharajah; she left innumerable other lights o’passing love in towns and cities andtheatres and railway stations all over the world. But Melchior she did not leave.9.2.2 Literal language and figurative languageLITERAL meaning: The first meaning for a word that a dictionary definition gives.E.g. tree: “a large plant”, an organism which has bark, branches and leaves.FIGURATIVE meaning: the metaphorical meaning rather than the ordinary one.E.g. a family tree, (ancestry)Different forms of tropes (figurative use of language):SIMILE is a way of comparing one thing with another, of explaining what one thing is like by showing how it is similar to another thing, and it explicitly signals itself in a text,with the words as or like.METAPHOR, like a simile, also makes a comparison between two unlike elements; but unlike a simile, this comparison is implied rather than stated. Compare the followingtwo examples.Ex. 9—6 The world is like a stage. (simile). Ex. 9—7 All the world’s astage,Metonymy: like metaphor(the transport of ideas), means a change of name.Synecdoche: refers to using the name of part of an object to talk about the whole thing, and vice versa.9.2.3 The analysis of literary languageVarious ways can be used to literary texts, depending on:the kind of text we are dealing withthe aim of analysis (cf. P288-289 for detailed procedures)Section Two The Language in Poetry9.3 The language in poetry9.3.1 Sound patterningMost people are familiar with the idea of RHYME in poetry, in deed for some, this is what defines poetry. END RHYME(i.e. rhyme at the end of lines, cVC) is very common in some poetic styles, and particularly in children’s poetry:9.3.2 Different forms of sound patterningRhyme me-be love-prove/mi:/-/bi:/ /l v/-/pruv/Alliteration: the initial consonants are identical (Cvc)me-my pleasures-prove/mi:/-/mai/ /’ple z/ / pruv/Assonance(准押韵) describes syllables with a common vowel (cVc)live-with-will come-love/liv/-/wi /-/wil/ /k m/-l v/Consonance(辅音韵): Syllables ending with the same consonants (cvC)will-all/wil/- :l/Reverse rhyme(反韵)describes syllables sharing the vowel and initial consonant, CVc, rather than the vowel and the final consonant as is the case in rhyme.with-will/wi /-wil/Pararhyme(侧押韵)two syllables have the same initial and final consonants, but different vowels (CvC)live-love/l v/-l v/Repetition CVC, for example “the sea, the sea”. This is called REPETITION.9.3.3 Stress and metrical patterningIn English words of two syllables, one is usually uttered slightly louder, higher, held for slightly longer, or otherwise uttered slightly more forcefully than the other syllable in the same word, when the word is said in normal circumstances. This syllable is called the STRESSED syllable. For example, in the word kitten, kit is the stressed syllable, while ten is the UNSTRESSED syllable. In addition to stress within an individual word, when we put words together in utterances we stress some more strongly than others. Where someone puts the stress depends partly on what they think is the most important information in their utterance, and partly on the inherent stresses in the words.Metrical pattern : (韵律模式)1.Iamb(抑扬格): the pattern of unstressed and stressed syllables2.Trochee (扬抑格): the stressed followed by an unstressed syllables3.Anapest : two unstressed syllables followed by a stressed one4.Dactyl: a stressed syllable followed by two unstressed ones.5.Spondee: two stressed ( lines of poetry rarely consist only of spondees)6.Pyrrhic: two unstressed syllable9.3.4 Conventional forms of metre and soundAt different times, different patterns of metre and sound have developed and become accepted as ways of structuring poems. These conventional structures often have names, and if you are analyzing poems, it is advisable to be familiar with the more frequent conventions that poets use. Some conventional forms of metre and sound are as follows. (see P294-295)CoupletsQuatrainsBlank verseOthers: sonnet, free verse, limericks.9.3.5 The poetic functions of sound and metre9.3.6 How to analyse poetry?The following checklist provided by Thornborrow and Wareing (1998) may help to cover the areas of discussion when analyzing poetry.(1)Information about the poemIf this information is available to you, somewhere in your analysis give the title of the poem, the name of the poet, the period in which the poem was written, the genre to which the poem belongs, e.g. lyric, dramatic, epic sonnet, or satire, etc. You might also mention the topic, e.g. whether it is a love poem, a war poem or a nature poem.(2)The way the poem is structuredThese are structural features that you should check for; there may well be others we have omitted. Don’t worry if you don’t find any examples of reverse rhyme, or a regular metrical pattern in your poem. What matters is that you looked, so if they had been there, you wouldn’t have missed them.Section Three Language in Fiction9.4. The language in fiction9.4.1 Fictional prose and point of viewAccording to Mick short (1996), we need at least three levels of discourse to account for the language of fictional process (i.e. a novel or short story), because there is a narrator-narratee level intervening between the character-character level and the author-reader level (see P298): ViewpointsI-narrators:3rd-person narratorsschema-oriented languagegiven vs new informationDeixis9.4.2 Speech and thought presentationSpeech presentation: (see P301-303)1)Direct speech (DS)2)Indirect Speech (IS)3)Narrator’s representation of speech acts (NRSA)4)Narrator’s representation of speech (NRS)The speech contribution of the character is arranged in a decreased orderThough presentation (see P301-304)1)Direct thought2)Free indirect thought3)Stream of consciousness writing9.4.3 Prose style (P306-307)1)authorical style:2)text style.Section Four Language in Drama9.5 The language in dramaA play exists in two ways—on the page, and on the stage. Our interest in this book, nevertheless, is in the language of the play on the page.9.5.1 How should we analyse drama?a)Drama as poetryb)Drama as fictionc)Drama as conversation9.5.2 Analysing dramatic language1)Turn quanjtity and length2)Exchange sequence3)Production errors4)The cooperative principle5)Status marked through language6)Register7)Speech and silence-female characters in plays9.5.3 How to analyse dramatic texts?1)Paraphrase the text—i.e. put it into your own words2)Write a commentary on the text3)Select a theoretical approach, perhaps from those discussed above.Chapter 11 Language and Foreign Language TeachingSection One Linguistic Views in Language1. The relation of linguistics to TEFL语言学和外语教学的关系Language is viewed as a system of forms in linguistics, but it is regarded as a set of skills in the field of language teaching. Linguistic research is concerned with the establishment of theories, which explains the phenomena of language, whereas language teaching aims at th e learner’s mastery of language.To bride the gap between the theories of linguistics and the practice of foreign language teaching, APPLIED LIGUISTICS serves as a mediating area that interprets the results of linguistic theories and makes them user-friendly to the language teacher and learner.Applied linguistics is conducive to foreign language teaching in two major aspects:1)Firstly, applied linguistics extends theoretical linguistics in the directionof language learning and teaching, so that the teacher is enabled to make better decisions on the goal and content of the teaching.2)Secondly, applied linguistics states the insights and implications thatlinguistic theories have on the language teaching methodology.2. Various linguistic views and their significance in language learning and teaching语言学观点及其在语言教学中的价值2.1 Traditional grammar传统语法A TRADITIONAL GRAMMAR is a pre-20th century language description, which is based on earlier grammars of Greek or Latin. As a product of the pre-linguistic era, it lays emphasis on correctness, literary excellence, the use of Latin models, and the priority of the written language.In language teaching textbooks based on traditional grammars take prominent writers of the previous centuries as language models. They favor the pasty “purest” language form rather than the present “degenerated” from; they prefer the written language to spoken language; they concentrate on detailed points instead of the construction of the whole text. Under traditional language teaching, students learn to know many taboos. For example, in English one cannot use “Split infinitives” or end sentences with prepositions,because these are not allowed in Latin grammar. The traditional approach to language teaching involves the presentation of numerous definitions, rules and explanations, and it adopts a teacher-centered grammar-translation method, i.e. the main teaching and learning activities are grammar and translation study. In the view of many modern linguists, such an approach is damaging to language learning. They argue that one should teach the language, not teach about the language. In communication, one should learn first to “speak” the language, not to “read” the language.2.2 Struicturalist linguistics结构主义语言学Structuralist linguistics describes linguistic features in terms of systems or structures. Dissatisfied with traditional grammars, structuralist grammar sets out to describe the current spoken language which people use in communication. For the first time, structuralist grammar provides description of phonological systems, which aids the systematic teaching of pronunciation. However, like traditional grammars, the focus of structuralist grammar is still on the grammatical structures of a language. Structuralist teaching materials are arranged on a basis of underlying grammatical patterns and structures, and ordered in a way supposed to be suitable for teaching. Structuralist linguists are influenced by the behaviouristic view that one learns a language by building up habits on the basis of stimulus-response chains. In teaching method this implies a pattern drill technique which aims at the learner’s automatism’s for language forms.2.3 Transformational-Generative linguistics转换生成语言学Proposed by Chomsky, Transformation-Generative grammar (or TG grammar) sees language as a system of innate rules. In Chomsky’s view, a native speaker possesses a kind of linguistic competence. The child is born with knowledge of some linguistic universals. While acquiring his mother tongue, he compares his innate language system with that of his native language and modifies his grammar. Therefore, language learning is not a matter of habit formation, but an activity of building and testing hypothesis. As for the construct of a sentence, TG grammar describes it as composed of a deep structure, a surface structure and some transformational rules. Although Chomsky does intend to make his model a representation of performance, that is, the way language is actually used in communication, some applied linguists find that TG grammar offers useful ideas for language teaching. In designing teaching materials, for example, sentence patterns withthe same deep structure can be closely related, such as the active and the passive. Transformational rules may assist the teacher in the teaching of complex sentence construction. In the teaching of literature, TG grammar provides a new instrument for stylistic analysis. For instance, a writer’s style can be identified according to certain kinds of transformation which frequently appear in his writing, say, nonimalization, verbalization, adjectivization, adverbialization, passivization, etc. (Ohmann, 1964). Nevertheless, despite the various attempts to apply TG grammar to language teaching, the influence of such a formal and abstract grammar remains limited in the field of language education as Chomsky himself openly claimed that language teaching and learning is not his concern.2.4 Functional linguistics功能语言学Taking a semantic-sociolinguistic approach, Halliday’s systemic functional linguistics sees language as an instrument used to perform various functions in social interaction. Halliday writes a number of works in which he examines the development of language functions in the child and the function language has in society.For Halliday, learning language is learning to mean. In other to be able to mean, one has to master a set of language functions, which have direct relation to sentence forms. In the child language, there are seven initial forms. In the adult language, however, these discrete functions are replaced by three META-FUNCTIONS: the ideational function, the interpersonal function, the ideational function, and the textual function.Since systemic-functional linguistics sees the formal system of language as a realization of functions of language in use, its scope is broader than that of formal linguistic theories. In the field of language teaching, it leads to the development of notion / function-based syllabuses, which have attracted increasing attention. In the section of “syllabus design,” we will come back to this kind of syllabus in detail.2.5 The theory of communicative competence交际能力理论The concept COMPETENCE originally comes from Chomsky. It refers to the grammatical knowledge of the ideal language user and has nothing to do with the actual use of language in concrete situations. This concept of linguistic competence has been criticized for being too narrow and resenting a “Garden of Eden View”. To expand the concept of competence, D.H. Hymes (1971) proposes COMMUNICATIVE COMPETENCE, which has fourcomponents: POSSIBILITY –the ability to produce grammatical sentences; FEASIBILITY—the ability to produce sentences which can be decoded by the human brain; APPROPRIATENESS—the ability to use correct forms of language in a specific socio-cultural context; PERFORMANCE—the fact that the utterance is completed.In Hymes’ view, the learner acquires knowledge of sentences not only as grammatical but also as appropriate. The aim of language learning is the ability to perform a repertoire of speech acts so as to take part in speech events. This is another way of saying that learning language is learning to perform certain functions. Like Halliday’s functional grammar, Hymes’ theory also leads to notion / function-based syllabuses, and a step further, communicative syllabuses.The theory of communicative competence stresses the context in which an utterance occurs. In its application, the teacher may teach how in different situations the same sentence can perform the function of statement, command, or request. On the other hand, while introducing different linguistic forms with the same semantic structure, for example the two forms of “you” in Chinese, he may draw special attention to different contexts in which they are used. The conceptual approach also leads to a concentration on discourse, in Hymes’ term linguistic routines—the sequential organization beyond sentences. Thus in the teaching of literature, the teacher can focus on features of different generes. In the teaching of conversation, he can introduce such strategies as opening, continuing, turn taking and closing. To present teaching contents of this kind, a learner-centered teaching methodology is necessary.Section Two Syllabus Design3. Syllabus Design教学大纲的设计3.1 What is syllabus?什么是教学大纲SYLLABUS is the planning of a course of instruction. It is a description of the course content, teaching procedures and learning experiences. The concept “syllabus” is often used interchangeably with “curriculum”, but CURRICULUM is also used in a broader sense, referring to all the learning goals, objectives, contents, processes, resources and means of evaluation planned for students both in and out of the school.3.2 Major factors in syllabus design大纲设计的主要因素1)Selecting participants选择参与者2)Process过程3)Evaluation评估3. Types of Syllabus教学大纲的类型Structural syllabus结构教学大纲Influenced by structuralist linguistics, the STRUCTURAL SYLLABUS is a grammar oriented syllabus based on a selection of language items and structures. The vocabulary and grammatical rules included in the teaching materials are carefully ordered according to factors such as frequency, complexity and usefulness. The linguistic units in a sentence may appear in slots:Situational syllabus情景教学大纲The SITUATONAL SYLLABUS does not have a strong linguistic basis, yet it can be assumed that the situationnalists accept the view that language is used for communication. The aim of the situational syllabus is specifying the situations in which the target language is used. The selection and organization of language items are based on situations. Grammatical forms and sentence partner are introduced and practiced, but they are knitted in dialogues entitled “At the Air-port”, “At the Supermarket”, “At the Bank”, and so on. In class an AURAL-ORAL TEACHING METHOD is adopted, i.e., new materials are heard and spoken before they are read and written by the learners. This method may still be teacher-centred, but compared with the grammar-translation method there is more particip ation on the learner’s part. The teacher can make use of picture, real objects, and the postures of the participants to involve students in dialogues and role-playing.Notional-functional syllabus意念-功能教学大纲First proposed by D. Wilkins and J.A. van Ek, the NOTIONAL-FUNCTIONAL SYLLABUS has received considerable attention since the 70s. Compared to the situational syllabus, the notional-functional syllabus has a much stronger theoretical basis—it is directly influenced by Halliday’s functional grammar and Hymes’ theory of communicative competence. The concept of NOTION refers to the meaning one wants to convey, while that of FUNCTION refers to what one can do with the language. For example, while sayi ng “Would you please tell me how to get to the library?” the speaker expresses the notion of inquiry and performs the function of asking the way. The notional-functional syllabus is initiallyconcerned with what the learner communicates through the language—not with what the grammatical structure is, or when or where he uses the language. It is proposed that one should analyze the needs of the learner to express meanings before deciding the lexico-grammatical options required. What the notional-functional syllabus wants the learner to acquire is, first, the knowledge of language structures, and second, the ability of using them in different situations to express ideas. The notional-functional approach to language teaching views all course components as a systematic whole, and classroom activities should be learner-centred.Communicative syllabus交际教学大纲A COMMUNICATIVE SYLLABUS aims at the learner’s communicative competence. Based on as notional-functional syllabus, it teaches the language needed to express and understand different kinds of functions, and emphasizes the process of communication.Summarizing the previous theories on communicative approach to syllabus design, Janice Yalden (1983) lists ten components of a communicative syllabus:1. as detailed a consideration as possible of the purposes for which the learners wish to acquire the target language;2. some idea of the setting in which t hey will want to use the target language (physical aspects need to be considered, as well as social setting);3. the socially defined role the learners will assume in the target language, as well as the roles of their interlocutors;4. The communicative events in which the learners will participate: everyday situations, vocational or professional situations, academic situations, and so on;5. the language functions involved in these events, or what the learner will need to be able to do with or through the language;6. the notions involved, or that the learner will need to be able to talk about;7. the skills involved in the “knitting together” of discourse: discourse and rhetorical skills;8. the variety or varieties of the target language that will be needed, and the levels in the spoken and written language which the learners will need to reach;9. the grammatical content that will be needed;10. the lexical content that will be needed.Fully Communicative Syllabus完全交际教学大纲The FULLY COMMUNICATIVE SYLLABUS stresses that linguistic competence is only a part of communicative competence. If we focus on communicative skills, most areas of linguistic competence will be developed naturally. Therefore, what we should teach is communication through language rather than language for communication. It is suggested that fully communicative teaching should do away with well planned syllabuses. What should be decided is the problem of communication to be solved, and the teacher should involve his students into activities in which they imitate his use of language consciously or unconsciously. If the teacher can well direct this process, language learning will take care of itself.Section Three Language Learning and Error Analysis4. Language learning语言学习The previous sections summarized various linguistic views and their significance in language teaching and learning. The discussions centred around how the practice of language teaching and learning has been influenced by different schools of linguistic studies, e.g. traditional grammars, structuralist linguistics, transformational generative lingui9stics, functional linguistics, etc. Although “learning” has frequently mentioned, most of the discussions are actually about how “teaching” has been influenced by linguistic theories. It is true that language teachers’ knowledge in linguistics (or their linguistic views) plays an important role when they make decisions about what to teach and how to teach. However, in whatever circumstances, in order for language teaching to be effective, no decision should be made if due attention is not paid to what and how the learners actually learn. In fact, in the past three or four decades, the research focus in language education has shifted from “how teachers teach” to “how learners learn”.4.1 Grammar and language learning语法和语言学习One of the major issues raised by second language acquisition researchers is the controversial question of whether and how to include grammar in second language instruction. The discrete-point grammar instruction conducted by more traditional language teachers has been widely criticized for focusing on forms and ignoring meanings. However, findings from immersion and naturalistic language acquisition studies suggest that when classroom second language learning is entirely experiential and meaning-focused, some linguistic features do not ultimately develop to target like levels (Doughtyand Williams, 1998:2). As a compromise between the “purely form focused” approaches and the “purely meaning focused” approaches, a recent movement of FOCUS ON FORM seems to take a more balanced view on the role of grammar in language learning.4.2 Input and language learning输入和语言学习It is self-evident that language learning can take place when the learner has enough access to input in the target language. This input may come in written or spoken form. In the case of spoken input, it may occur in the context of interaction (i.e. the learner’s attempts to converse with a native speaker, a teacher, or another learner) or in the context of non-reciprocal discourse (for example, listening to the radio or watching a film).4.3 Interlanguage in language learning语言学习中的中介语Besides input, output has also been reported to promote language acquisition (Swain, 1985; Skehan, 1998). Correct production requires learners to construct language for the their messages. When learners construct language for expression, they are not merely reproducing what they have learned. Rather they are processing and constructing things. For example, they process syntax read or heard and construct syntax that can be used to express what they wish to convey.The conception of language output as a way to promote language acquisition is to some extent in line with the so called CONSTRUCTIVISM. A constructivist view of language argues that language (or any knowledge) is socially constructed (Nunan, 1999:304) . Learners learn language by cooperating, negotiating and performing all kinds of tasks. In other words, they construct language in certain social and cultural contexts.5. Error Analysis错误分析5.1 Errors, mistakes, and error analysis语法错误,语用错误和错误分析When a linguistic item is used as the result of faulty or incomplete learning, the learner is considered to have committed an error. A distinction is sometimes made between an error and a mistake. ERROR is the grammatically incorrect form; MISTAKE appears when the language is correct grammatically but improper in a communicational context. While errors always go with language learners, mistakes may also occur to native speakers. There is another type of fault, namely LAPSE, which refers to slips of the tongue or pen made by either foreign language learners or native speakers. ERROR ANALYSIS, as the term suggest, is the study and analysis of。

现代英语语言学理论 CHAPTER 9

Cui Jianbin, Department of Foreign Studies, WTU

Chapter Nine

A Study on Modern English Linguistics: Language and Culture

现代英语语言学理论

Chapter Introduction Language in Poetry Further Reading

Discussion topics(10mins.)

1. What is literature? 2. What are possible literature forms? 3. What is the possible relationship between language

and literature? 4. What is the difference between literature language

and general language?

现代英语语言学理论

CLASS PRESENTATION

我们要美丽的生命不断繁殖, 能这样,美丽的玫瑰才不会消亡……

关关雎鸠,在河之州; 窈窕淑女,君子好逑。

现代英语语言学理论

CLASS PRESENTATION

Stoning

Cui Jianbin

April 10th—May 1st Friday 98

Advanced 50mins X2

现代英语语言学理论

现代英语语言学理论

现代英语语言学理论

Section One: : Features of Literary Language

Outline of Procedures

现代英语语言学理论

语言学Chapter 9

diameter: four syllables / two feet trimeter: tetrameter pentameter hexameter heptameter octameter

Stress Iamb: unstressed + stressed Trochee: stressed + unstressed Anapest: unstressed (2) + stressed Dactyl: stressed + unstressed (2) Spondee: stressed (2) Pyrrhic: unstressed (2)

Couplets Quatrains Blank verse

Exercise O! lest the world should task you to recite What merit lived in me, that you should love After my death,—dear love, forget me quite, For you in me can nothing worthy prove; Unless you would devise some virtuous lie, To do more for me than mine own desert, And hang more praise upon deceased I Than niggard truth would willingly impart: O! lest your true love may seem false in this, That you for love speak well of me untrue, My name be buried where my body is, And live no more to shame nor me nor you. For I am sham'd by that which I bring forth, And so should you, to love things nothing worth.

Chapter 9 Dramatic stylistics