2015ESC非ST段抬高心肌梗死治疗指南中文版

2015年急性ST段抬高型心肌梗死诊断和治疗指南

为AMI (第8版诊断学)

第十五页,共83页。

第十六页,共83页。

3.影像学检查 超声心动图等影像学检查有助于对急性胸痛

患者的鉴别诊断和危险分层(Ⅰ,C)。

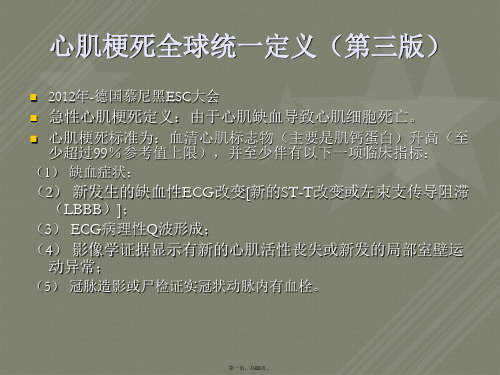

(3) ECG病理性Q波形成; (4) 影像学证据显示有新的心肌活性丧失或新发的局部室壁运

动异常;

(5) 冠脉造影或尸检证实冠状动脉内有血栓。

第一页,共83页。

解读新定义

新定义中的第5条是新增加的内容,其意义是强调一旦发生心肌 梗死后在救治的过程中,应积极行冠状动脉造影来验证心肌梗死 的原因,并尽早开始冠脉再通的治疗。

第十七页,共83页。

必须指出,症状和心电图能够明确诊断 STEMI的患者不需等待心肌损伤标志物和 (或)影像学检查结果,而应尽早给予再灌 注及其他相关治疗。

第十八页,共83页。

STEMI应与主动脉夹层、急性心包炎、急性肺动脉栓塞、气胸和消 化道疾病(如反流性食管炎)等引起的胸痛相鉴别。

向背部放射的严重撕裂样疼痛伴有呼吸困难或晕厥,但无典型的STEMI心电图 变化者,应警惕主动脉夹层。

溶栓治疗失败、伴有右心室梗死和血液动力学异常的 下壁STEMI患者病死率增高。合并机械性并发症的 STEMI患者死亡风险增大。冠状动脉造影可为STEMI风 险分层提供重要信息。

第二十页,共83页。

三、STEMI的急救流程

早期、快速和完全地开通梗死相关动脉是改善STEMI 患者预后的关键。

1.缩短自发病至FMC(首次接触医疗)的时间

非心脏手术所致的心梗;ICU内发生的心梗;心衰相关的心肌缺血或心梗。这些心 梗都冠以了导致心梗发生的原因的名字,提醒我们在很多情况下都可以发生心梗,

《2015年中国急性ST段抬高型心肌梗死诊断及治疗指南》--更新要点解读

《2015年中国急性ST段抬高型心肌梗死诊断及治疗指南》--更新要点解读袁晋青;宋莹【摘要】《2015年中国急性ST段抬高型心肌梗死诊断及治疗指南》的公布,规范、更新及优化了急性ST段抬高型心肌梗死的诊疗流程。

本文针对指南更新要点进行解读。

【期刊名称】《中国循环杂志》【年(卷),期】2016(031)004【总页数】3页(P318-320)【关键词】心肌梗死;指南;更新要点【作者】袁晋青;宋莹【作者单位】100037 北京市,中国医学科学院北京协和医学院国家心血管病中心阜外医院冠心病诊治中心;100037 北京市,中国医学科学院北京协和医学院国家心血管病中心阜外医院冠心病诊治中心【正文语种】中文【中图分类】R541自2013年之后,美国及欧洲相继对急性ST段抬高型心肌梗死(STEMI)治疗指南进行了修订[1-4],中华医学会心血管病学分会动脉粥样硬化和冠心病学组,在美国及欧洲指南的基础上,结合国内外多项诊疗研究进展,以及第三版“心肌梗死全球定义”,于2015年发布了中国急性ST段抬高型心肌梗死诊断和治疗指南(以下简称新指南)[5]。

本文将针对2015年指南的更新要点进行解读。

2015年新指南推荐使用第三版“心肌梗死全球定义”,将心肌梗死分为5型[1]。

较2010年更详细阐述了经皮冠状动脉介入治疗(PCI)相关心肌梗死和外科冠状动脉旁路移植术(CABG)相关心肌梗死的定义及诊断标准。

(1)1型为自发性心肌梗死:由于动脉粥样斑块破裂导致的单支或多支冠状动脉血栓形成而引发的心肌坏死。

多数有严重的冠状动脉病变,少数轻度狭窄甚至正常;(2)2型为继发于心肌氧供需失衡的心肌梗死:除冠状动脉病变外其他引起心肌氧供需失衡导致的心肌坏死。

如冠状动脉痉挛、贫血等;(3)3型指心脏性猝死:心脏性死亡伴随心肌缺血症状或新的缺血心电图改变或左束支传导阻滞,但无心肌损伤标志检测结果;(4)4a型指PCI相关心肌梗死:基线心脏肌钙蛋白(cTn)正常者在PCI术后升高超过正常上限5倍;或基线cTn增高者术后升高≥20%,然后稳定下降。

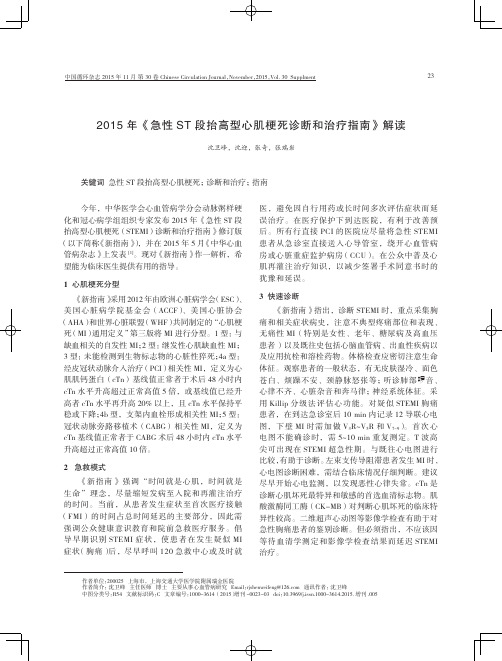

2015年《急性ST段抬高型心肌梗死诊断和治疗指南》解读

23中国循环杂志 2015年11月 第30卷 Chinese Circulation Journal,November,2015,Vol. 30 Supplment 2015年《急性ST 段抬高型心肌梗死诊断和治疗指南》解读沈卫峰,沈迎,张奇,张瑞岩作者单位:200025 上海市,上海交通大学医学院附属瑞金医院作者简介:沈卫峰 主任医师 博士 主要从事心血管病研究 Email:rjshenweifeng@ 通讯作者:沈卫峰中图分类号:R54 文献标识码:C 文章编号:1000-3614(2015)增刊-0023-03 doi:10.3969/j.issn.1000-3614.2015. 增刊.005关键词 急性ST 段抬高型心肌梗死;诊断和治疗;指南今年,中华医学会心血管病学分会动脉粥样硬化和冠心病学组组织专家发布2015年《急性ST 段抬高型心肌梗死(STEMI)诊断和治疗指南》修订版(以下简称《新指南》),并在2015年5月《中华心血管病杂志》上发表[1]。

现对《新指南》作一解析,希望能为临床医生提供有用的指导。

1 心肌梗死分型《新指南》采用2012年由欧洲心脏病学会(ESC)、美国心脏病学院基金会(ACCF)、美国心脏协会(AHA)和世界心脏联盟(WHF)共同制定的 “心肌梗死(MI)通用定义”第三版将MI 进行分型。

1型:与缺血相关的自发性MI;2型:继发性心肌缺血性MI;3型:未能检测到生物标志物的心脏性猝死;4a 型:经皮冠状动脉介入治疗(PCI)相关性MI,定义为心肌肌钙蛋白(cTn)基线值正常者于术后48小时内cTn 水平升高超过正常高值5倍,或基线值已经升高者cTn 水平再升高20%以上,且cTn 水平保持平稳或下降;4b 型,支架内血栓形成相关性MI;5型:冠状动脉旁路移植术(CABG)相关性MI,定义为cTn 基线值正常者于CABG 术后48小时内cTn 水平升高超过正常高值10倍。

欧洲心脏病学会(ESC)关于非ST段抬高急性冠脉综合征管理指南

欧洲心脏病学会(ESC)关于非ST段抬高急性冠脉综合征管理指南伦敦会展中心主会场,欧洲心脏病学会(ESC)正式发布了在非ST段抬高急性冠脉综合征(NSTE-ACS)管理指南。

新指南是指南发布4年后的首次更新,新指南推荐内容更为简洁和明确,多采用流程图,实用性更强,对指导NSTE-ACS患者的规范化诊治具有重要意义。

新指南在以下六个方面做了更新或者新增,1)冠脉造影和PCI经桡动脉入路获得最高级别推荐;2)高敏肌钙蛋白(hs-cTnT)1小时检测流程(algorithm)获得推荐;3)根据患者出血或缺血风险,给予更个体化的DAPT时间;4)不推荐P2Y12抑制剂预处理:反对NSTEMI患者使用普拉格雷进行预处理,支持或反对氯吡格雷或替格瑞洛进行预处理的证据均不充分;5)首次对NSTE-ACS患者根据临床表现进行心律监测时程(0、<24h、>24h)作出了推荐。

对监护病房患者管理进行了简化,有助于缩短住院时间、降低费用;6)新增对长期口服抗凝药患者使用抗血小板治疗的新章节。

根据MATRIX及相关荟萃分析结果,新指南首次对血管入路做出推荐。

对于有经验的中心,建议在冠脉造影和PCI时选择经桡动脉入路(I/A)。

同时,指南强调,血管入路的选择仍应考虑术者经验和中心习惯。

对于多支血管病变, 强调要根据具体病情及当地血管团队的流程来制定具体的血远重建策略。

这对于我国90%以上的医院外科搭桥水平较国外差距巨大的现状尤为有指导意义。

对于使用Hs-cTnT 1小时检测流程,我国存在的问题是检测方法众多,医院之间、城市之间标准值不同,无法直接对比,迫切需要标准化,更要注重结合临床情况判读。

基于大量新型支架证据,新指南建议应用新一代DES(I/A)。

此外,对于高出血风险计划接受短时程双联抗血小板治疗(30天)的患者,新一代DES可能优于BMS(IIb/B)。

2015年新指南的危险分层更为细化,分为极高危、高危、中危、低危4个级别,与2014年美国心脏协会(AHA)/美国心脏病学会(ACC)NSTE-ACS管理指南趋于一致。

2015急性ST段抬高型心肌梗死指南解读

第九页,编辑于星期四:十六点 三十七分。

• 病史采集(重点询问胸痛和相关症状为胸骨后或心前区剧烈的压 榨性疼痛(通常超过10-20min),可向左上臂、下颌、颈部、 背或肩部放射;常伴有恶心、呕吐、大汗或呼吸困难等,含 硝酸甘油不能完全缓解。应注意不典型疼痛部位的表现及无 痛性心肌梗死(特别是女性、老年、糖尿病及高血压患者),

既往史包括冠心病史(心绞痛、心肌梗死、CABG或PCI)、 高血压、糖尿病、外科手术或拔牙史,出血性疾病(消化 道溃疡、脑血管意外、大出血、不明原因贫血或黑便), 脑血管疾病(缺血性卒中、颅内出血或蛛网膜下腔出血) 以及抗血小板、抗凝、溶栓药物应用史

囊开始扩张的时间>90分钟

第二十二页,编辑于星期四:十六点 三十七分。

首选有创性治疗

● 医务人员接诊至球囊开始扩张的时间或从病人到医院至球囊开 始扩张的时间<90分钟

从病人到医院至球囊开始扩张的时间)<60 ● STEMI所致高危因素

心原性休克 Killp分类≥3#

● 纤溶禁忌证,包括出血和颅内出血危险增加

(2) 新发生的缺血性ECG改变[新的ST-T改变或左束支传导 阻滞(LBBB)];

(3) ECG病理性Q波形成;

(4) 影像学证据显示有新的心肌活性丧失或新发的局部室壁运动

异常;

(5) 冠脉造影或尸检证实冠状动脉内有血栓。

第二页,编辑于星期四:十六点 三十七分。

入院急诊治 疗

ESC急性ST段抬高心肌梗死治疗指南(全文)

ESC急性ST段抬高心肌梗死治疗指南(全文)本文就指南所推荐的一些新的及重要的观点总结如下。

1.更加强调及时再灌注治疗的重要性,对STEMI区域网络、院前急救系统和直接PCI医院提出了具体要求。

(1)强调需要建立STEMI区域性网络管理系统,治疗决策和方案不是由一个中心或一个部门协调,而是区域网络内不同单位之间的协作,并且通过高效的院前急救系统进行联系。

要求院前急救人员将STEMI患者分流到能够实施直接PCI的医院;一旦到达相应医院,应当立即将患者送至导管室,绕过急诊室;如果救护车人员未做出STEMI的诊断,并且救护车到达非直接PCI医院,则应等待诊断结果,如果证实为STEMI,应将患者继续转运至直接PCI医院;到非PCI医院就诊的患者在等待转运至直接或补救性PCI医院时,应当在配备相应监测和医务人员的区域等待;将患者从非PCI医院转运到PCI医院的时间延迟不超过120 min,理想目标是90 min。

(2)再次强调首次医疗接触(院前急救系统或首诊医院)的概念,评价治疗时间延迟的起始点由以往的“进门时间”前移为“首次医疗接触时间”。

因此,对院前急救系统提出更高的要求。

(3)急诊处理的具体要求:①与患者首次医疗接触后立即启动诊断和治疗预案;②在医疗接触10 min 内尽快完成12导联ECG;③对所有拟诊STEMI的患者启动ECG监测,减少早期心源性猝死;④对有进行性心肌缺血症状和体征的患者,即使ECG表现不典型,也应当积极处理;⑤院前处理STEMI患者必须建立在能够迅速和有效实施再灌注治疗区域网络基础上,尽可能使更多的患者接受直接PCI;⑥能够实施直接PCI的医院必须提供每天24小时/每周7天的服务,尽可能在接到通知后60 min 内开始实施直接PCI,要求比以前缩短;⑦所有医院和院前急救系统必须记录和监测时间延迟,努力达到并坚守下列质量标准:首次医疗接触至记录首份ECG时间≤10 min ;首次医疗接触至实施再灌注的时间:溶栓≤30 min ,直接PCI ≤90 min (如果症状发作在120 min 之内或直接到能够实施PCI的医院,则≤60 min )。

ESC2015 NSTEACS指南

ESC2015 指南: 非 ST 段抬高型急性冠脉综合征(中文版)2015-09-01 09:09来源:丁香园作者:Tylen Chen字体大小-|+关于可疑非 ST 段抬高型急性冠脉综合征(ACS)患者的诊断、风险分层、影像学检查和心律监测的若干建议1. 诊断和风险分层(1)建议结合患者的病史、症状、重要体征、其他体格检查发现、 ECG 和实验室检查结果等,对患者进行基本诊断以及行短期的缺血和出血风险分层。

(I,A)(2)建议患者就诊后 10 min 内迅速行 12 导联 ECG 检查,并立即让有经验的医生查看结果。

为了防止症状复发或者诊断不明确,有必要再次行 12 导联 ECG 检查。

(I,B)(3)如果标准导联 ECG 结果阴性,但仍然高度怀疑缺血性病灶的存在,建议增加 ECG 导联(V3R、V4R、V7-V9)。

(I,C)(4)建议检测心肌钙蛋白(敏感或者高敏法),且在 60 min 内获取结果。

(I,A)(5)如果有高敏肌钙蛋白的结果,建议行 0 h 和 3 h 的快速排查方案。

(I,B)(6)如果有高敏肌钙蛋白的结果以及确认可用 0 h/1 h 算法,建议行 0 h 和 1 h 的快速排查和确诊方案。

如果前两次肌钙蛋白检测结果阴性但临床表现仍然提示 ACS,建议在 3-6 h 之后再做一次检查。

(I,B)(7)建议使用现有的风险分数来诊断评估患者病情。

(I,B)(8)如果患者预行冠脉造影,可考虑使用 CRUSADE 分数量化出血风险。

(IIb,B)2. 影像学检查(1)如果患者无复发胸痛、ECG 结果正常、心肌钙蛋白检查结果正常(最好是高敏),但仍然怀疑存在 ACS,建议行无创性的负荷试验诱发缺血,结果不理想再进一步考虑有创性的检查。

(I,A)(2)建议行超声心动图以评估局部和全左心室功能,以及确诊和排查鉴别诊断。

(I,C)(3)如果心肌钙蛋白和 / 或 ECG 结果阴性,但仍怀疑低中度 CAD,可考虑行 MDCT 冠脉造影检查。

ESC欧洲心脏病学会《急性ST段抬高型心肌梗死(STEMI)管理指南》解读

ESC欧洲心脏病学会《急性ST段抬高型心肌梗死(STEMI)管理指南》解读欧洲心脏病学会年会发布了最新版本的《急性ST段抬高型心肌梗死(STEMI)管理指南》[1],这一指南梳理了急性STEMI救治的最新循证医学证据,对部分理念和概念进行了修订,对再灌注策略选择、药物治疗等诸多方面原指南做出了进一步更新。

现将该指南新概念、新观点和新治疗策略进行解读。

一、最新/修订概念1、非阻塞性冠脉疾病(MINOCA):2016年ESC冠脉学组所提出的新概念[3]。

是指确诊为心肌梗死,但冠状动脉造影检查血管狭窄程度<50%,甚至冠脉完全正常的一种心肌梗死。

指南针对此类疾病新增加一个章节。

该类疾病占STEMI患者的1-14%,治疗策略与阻塞性冠脉疾病不同。

最重要的方面是早期识别MINOCA,进而明确可能的原因(包括心肌炎、心尖球形综合征、冠脉痉挛和血栓形成倾向等疾病)。

因此,强调谨慎对待这部分患者的预后。

2、再灌注策略选择:指南剔除了“门球时间”这一模糊的术语,并将首次医疗接触(FMC)定义为医生、护理人员或护士首次对患者进行心电图检查及解读的时间点。

把确诊STEMI的时间点定义为“time 0”,并把这一时间点作为选择再灌注策略的计时开始。

如果预计从确诊STEMI到导丝通过病变的时间延误≤120min,建议选择直接PCI;如选择溶栓治疗,诊断STEMI至溶栓开始的时间延搁由2012年的30分钟缩短至10分钟。

3、开通梗死相关血管(IRA)时间窗:基于近年来临床研究的结果,指南适当拓宽了直接PCI的时间窗。

指南建议,发病在12小时以内、有缺血症状、伴持续性ST段抬高的所有患者应行再灌注治疗(I,A);发病超过12小时的患者,若存在症状进展提示缺血、血流动力学不稳定或致命性心律失常时,宜行直接PCI(I,C);症状发作后就诊延迟但发作时间在12~48小时的患者,可考虑常规直接PCI(IIa,B);症状发作>48的无症状患者,不建议常规行PCI开通闭塞IRA(III,A)。

2015急性ST段抬高型心肌梗死诊断和治疗指南

机械性并发症

乳头肌功能不全或断裂 常导致急性二尖瓣反流,表现为突然血液 动力学恶化,二尖 使杂音较轻);X线胸片示肺淤血或肺水肿; 超声心动图可诊断和定量二尖瓣反流。肺 动脉导管表现肺毛细血管嵌入压曲线巨大V 波。宜在血管扩张剂(例如静脉滴注硝酸 甘油)联合IABP辅助循环下尽早外科手术 治疗。

症状和心电图能够明确诊断STEMI的患者 不需等待心肌损伤标志物和(或)影像学 检查结果,而应尽早给予再灌注及其他相 关治疗

资质要求

开展急诊介入的心导管室每年PCI量≥100例 ,主要操作者具备介入治疗资质且每年独 立完成PCI≥50例 开展急诊直接PCI的医院应全天候应诊,并 争取STEMI患者首诊至直接PCI时间≤90 min。

抗栓治疗

STEMI的主要原因是冠状动脉内斑块破裂诱 发血栓性阻塞。因此,抗栓治疗(包括抗 血小板和抗凝)十分必要

抗血小板治疗

1.阿司匹林 通过抑制血小板环氧化酶使血栓素A2合成 减少,达到抗血小板聚集的作用。所有无 禁忌证的STEMI患者均应立即口服水溶性阿 司匹林或嚼服肠溶阿司匹林300 mg(Ⅰ, B),继以75~100 mg/d长期维持(Ⅰ, A)。

心源性休克

急诊血运重建治疗(包括直接PCI或急诊CABG)可改善 STEMI合并心原性休克患者的远期预后(Ⅰ,B),直接PCI 时可行多支血管介入干预[3,68]。STEMI合并机械性并发症时, CABG和相应心脏手术可降低死亡率。 不适宜血运重建治疗的患者可给予静脉溶栓治疗(Ⅰ,B), 但静脉溶栓治疗的血管开通率低,住院期病死率高。 血运重建治疗术前置入IABP有助于稳定血液动力学状态,但 对远期死亡率的作用尚有争论(Ⅱb,B)。 经皮左心室辅助装置可部分或完全替代心脏的泵血功能,有 效地减轻左心室负担,保证全身组织、器官的血液供应,但 其治疗的有效性、安全性以及是否可以普遍推广等相关研究 证据仍较少。

欧洲心脏病学会(ESC)关于非ST段抬高急性冠脉综合征管理指南

欧洲心脏病学会(ESC)关于非ST段抬高急性冠脉综合征管理指南伦敦会展中心主会场,欧洲心脏病学会(ESC)正式发布了在非ST段抬高急性冠脉综合征(NSTE-ACS)管理指南。

新指南是指南发布4年后的首次更新,新指南推荐内容更为简洁和明确,多采用流程图,实用性更强,对指导NSTE-ACS患者的规范化诊治具有重要意义。

新指南在以下六个方面做了更新或者新增,1)冠脉造影和PCI经桡动脉入路获得最高级别推荐;2)高敏肌钙蛋白(hs-cTnT)1小时检测流程(algorithm)获得推荐;3)根据患者出血或缺血风险,给予更个体化的DAPT时间;4)不推荐P2Y12抑制剂预处理:反对NSTEMI患者使用普拉格雷进行预处理,支持或反对氯吡格雷或替格瑞洛进行预处理的证据均不充分;5)首次对NSTE-ACS患者根据临床表现进行心律监测时程(0、<24h、>24h)作出了推荐。

对监护病房患者管理进行了简化,有助于缩短住院时间、降低费用;6)新增对长期口服抗凝药患者使用抗血小板治疗的新章节。

根据MATRIX及相关荟萃分析结果,新指南首次对血管入路做出推荐。

对于有经验的中心,建议在冠脉造影和PCI时选择经桡动脉入路(I/A)。

同时,指南强调,血管入路的选择仍应考虑术者经验和中心习惯。

对于多支血管病变, 强调要根据具体病情及当地血管团队的流程来制定具体的血远重建策略。

这对于我国90%以上的医院外科搭桥水平较国外差距巨大的现状尤为有指导意义。

对于使用Hs-cTnT 1小时检测流程,我国存在的问题是检测方法众多,医院之间、城市之间标准值不同,无法直接对比,迫切需要标准化,更要注重结合临床情况判读。

基于大量新型支架证据,新指南建议应用新一代DES(I/A)。

此外,对于高出血风险计划接受短时程双联抗血小板治疗(30天)的患者,新一代DES可能优于BMS(IIb/B)。

2015年新指南的危险分层更为细化,分为极高危、高危、中危、低危4个级别,与2014年美国心脏协会(AHA)/美国心脏病学会(ACC)NSTE-ACS管理指南趋于一致。

2015+ESC指南:非ST段抬高型急性冠脉综合征的管理

ESC GUIDELINES2015ESC guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevationTask Force for the Management of Acute Coronary Syndromes in Patients Presenting without Persistent ST-Segment Elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC)Authors/Task Force Members:Marco Roffi*(Chairperson)(Switzerland),Carlo Patrono *(Co-Chairperson)(Italy),Jean-Philippe Collet †(France),Christian Mueller †(Switzerland),Marco Valgimigli †(The Netherlands),Felicita Andreotti (Italy),Jeroen J.Bax (The Netherlands),Michael A.Borger (Germany),Carlos Brotons (Spain),Derek P.Chew (Australia),Baris Gencer (Switzerland),Gerd Hasenfuss (Germany),Keld Kjeldsen (Denmark),Patrizio Lancellotti (Belgium),Ulf Landmesser (Germany),Julinda Mehilli (Germany),Debabrata Mukherjee (USA),Robert F.Storey (UK),and Stephan Windecker (Switzerland)Document Reviewers:Helmut Baumgartner (CPG Review Coordinator)(Germany),Oliver Gaemperli (CPG Review Coordinator)(Switzerland),Stephan Achenbach (Germany),Stefan Agewall (Norway),Lina Badimon (Spain),Colin Baigent (UK),He´ctor Bueno (Spain),Raffaele Bugiardini (Italy),Scipione Carerj (Italy),Filip Casselman (Belgium),Thomas Cuisset (France),Çetin Erol (Turkey),Donna Fitzsimons (UK),Martin Halle(Germany),*Corresponding authors:Marco Roffi,Division of Cardiology,University Hospital,Rue Gabrielle Perret-Gentil 4,1211Geneva 14,Switzerland,Tel:+41223723743,Fax:+41223727229,E-mail:Marco.Roffi@hcuge.chCarlo Patrono,Istituto di Farmacologia,Universita`Cattolica del Sacro Cuore,Largo F.Vito 1,IT-00168Rome,Italy,Tel:+390630154253,Fax:+39063050159,E-mail:carlo.patrono@rm.unicatt.it&The European Society of Cardiology 2015.All rights reserved.For permissions please email:journals.permissions@.†Section Coordinators affiliations listed in the Appendix.ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines (CPG)and National Cardiac Societies document reviewers listed in the Appendix.ESC entities having participated in the development of this document:Associations:Acute Cardiovascular Care Association (ACCA),European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention &Rehabilitation (EACPR),European Association of Cardiovas-cular Imaging (EACVI),European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI),Heart Failure Association (HFA).Councils:Council on Cardiovascular Nursing and Allied Professions (CCNAP),Council for Cardiology Practice (CCP),Council on Cardiovascular Primary Care (CCPC).Working Groups:Working Group on Cardiovascular Pharmacotherapy,Working Group on Cardiovascular Surgery,Working Group on Coronary Pathophysiology and Microcir-culation,Working Group on Thrombosis.The content of these European Society of Cardiology (ESC)Guidelines has been published for personal and educational use only.No commercial use is authorized.No part of the ESC Guidelines may be translated or reproduced in any form without written permission from the ESC.Permission can be obtained upon submission of a written request to Oxford University Press,the publisher of the European Heart Journal and the party authorized to handle such permissions on behalf of the ESC.Disclaimer:The ESC Guidelines represent the views of the ESC and were produced after careful consideration of the scientific and medical knowledge and the evidence available at the time of their publication.The ESC is not responsible in the event of any contradiction,discrepancy and/or ambiguity between the ESC Guidelines and any other official recom-mendations or guidelines issued by the relevant public health authorities,in particular in relation to good use of healthcare or therapeutic strategies.Health professionals are encour-aged to take the ESC Guidelines fully into account when exercising their clinical judgment,as well as in the determination and the implementation of preventive,diagnostic or therapeutic medical strategies;however,the ESC Guidelines do not override,in any way whatsoever,the individual responsibility of health professionals to make appropriate and accurate decisions in consideration of each patient’s health condition and in consultation with that patient and,where appropriate and/or necessary,the patient’s caregiver.Nor do the ESC Guidelines exempt health professionals from taking into full and careful consideration the relevant official updated recommendations or guidelines issued by the competent public health authorities,in order to manage each patient’s case in light of the scientifically accepted data pursuant to their respective ethical and professional obligations.It is also the health professional’s responsibility to verify the applicable rules and regulations relating to drugs and medical devices at the time of prescription.European Heart Journaldoi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehv320European Heart Journal Advance Access published August 29, 2015by guest on August 29, 2015Downloaded fromChristian Hamm(Germany),David Hildick-Smith(UK),Kurt Huber(Austria),EfstathiosIliodromitis(Greece),Stefan James(Sweden),Basil S.Lewis(Israel),Gregory Y.H.Lip(UK),Massimo F.Piepoli(Italy),Dimitrios Richter (Greece),Thomas Rosemann(Switzerland),Udo Sechtem(Germany),Ph.Gabriel Steg(France),Christian Vrints (Belgium),and Jose Luis Zamorano(Spain)The disclosure forms of all experts involved in the development of these guidelines are available on the ESC website /guidelines------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------Keywords Acute cardiac care†Acute coronary syndromes†Angioplasty†Anticoagulation†Apixaban†Aspirin†Atherothrombosis†Beta-blockers†Bivalirudin†Bypass surgery†Cangrelor†Chest pain unit†Clopidogrel†Dabigatran†Diabetes†Early invasive strategy†Enoxaparin†European Society ofCardiology†Fondaparinux†Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors†Guidelines†Heparin†High-sensitivitytroponin†Myocardial ischaemia†Nitrates†Non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction†Platelet inhibition†Prasugrel†Recommendations†Revascularization†Rhythm monitoring†Rivaroxaban†Statin†Stent†Ticagrelor†Unstable angina†VorapaxarTable of ContentsAbbreviations and acronyms (4)1.Preamble (5)2.Introduction (7)2.1Definitions,pathophysiology and epidemiology (7)2.1.1Universal definition of myocardial infarction (7)2.1.1.1Type1MI (7)2.1.1.2Type2MI (7)2.1.2Unstable angina in the era of high-sensitivity cardiactroponin assays (7)2.1.3Pathophysiology and epidemiology(see Web addenda) (7)3.Diagnosis (7)3.1Clinical presentation (7)3.2Physical examination (8)3.3Diagnostic tools (8)3.3.1Electrocardiogram (8)3.3.2Biomarkers (9)3.3.3‘Rule-in’and‘rule-out’algorithms (10)3.3.4Non-invasive imaging (11)3.3.4.1Functional evaluation (11)3.3.4.2Anatomical evaluation (11)3.4Differential diagnosis (12)4.Risk assessment and outcomes (12)4.1Clinical presentation,electrocardiogram and biomarkers124.1.1Clinical presentation (12)4.1.2Electrocardiogram (12)4.1.3Biomarkers (13)4.2Ischaemic risk assessment (13)4.2.1Acute risk assessment (13)4.2.2Cardiac rhythm monitoring (13)4.2.3Long-term risk (14)4.3Bleeding risk assessment (14)4.4Recommendations for diagnosis,risk stratification,imagingand rhythm monitoring in patients with suspected non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes (14)5.Treatment (15)5.1Pharmacological treatment of ischaemia (15)5.1.1General supportive measures (15)5.1.2Nitrates (15)5.1.3Beta-blockers (15)5.1.4Other drug classes(see Web addenda) (16)5.1.5Recommendations for anti-ischaemic drugs inthe acute phase of non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes (16)5.2Platelet inhibition (16)5.2.1Aspirin (16)5.2.2P2Y12inhibitors (16)5.2.2.1Clopidogrel (16)5.2.2.2Prasugrel (16)5.2.2.3Ticagrelor (17)5.2.2.4Cangrelor (18)5.2.3Timing of P2Y12inhibitor administration (19)5.2.4Monitoring of P2Y12inhibitors(see Web addenda) (19)5.2.5Premature discontinuation of oral antiplatelet therapy (19)5.2.6Duration of dual antiplatelet therapy (19)5.2.7Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors (20)5.2.7.1Upstream versus procedural initiation(see Web addenda) (20)5.2.7.2Combination with P2Y12inhibitors(see Web addenda) (20)5.2.7.3Adjunctive anticoagulant therapy(see Web addenda) (20)5.2.8Vorapaxar(see Web addenda) (20)5.2.9Recommendations for platelet inhibition innon-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes (20)5.3Anticoagulation (21)5.3.1Anticoagulation during the acute phase (21)5.3.1.1Unfractionated heparin (21)5.3.1.2Low molecular weight heparin (22)5.3.1.3Fondaparinux (22)5.3.1.4Bivalirudin (22)5.3.2Anticoagulation following the acute phase (23)ESC GuidelinesPage2of59by guest on August 29, 2015Downloaded fromnon-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes (23)5.4Managing oral antiplatelet agents in patients requiringlong-term oral anticoagulants (24)5.4.1Patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (24)5.4.2Patients medically managed or requiring coronaryartery bypass surgery (26)5.4.3Recommendations for combining antiplatelet agentsand anticoagulants in non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome patients requiring chronic oral anticoagulation.26 5.5Management of acute bleeding events(see Web addenda) (27)5.5.1General supportive measures(see Web addenda)..27 5.5.2Bleeding events on antiplatelet agents(see Web addenda) (27)5.5.3Bleeding events on vitamin K antagonists(see Web addenda) (27)5.5.4Bleeding events on non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants(see Web addenda) (27)5.5.5Non-access-related bleeding events(see Web addenda) (27)5.5.6Bleeding events related to percutaneous coronary intervention(see Web addenda) (27)5.5.7Bleeding events related to coronary artery bypass surgery(see Web addenda) (27)5.5.8Transfusion therapy(see Web addenda) (27)5.5.9Recommendations for bleeding management andblood transfusion in non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes (27)5.6Invasive coronary angiography and revascularization (28)5.6.1Invasive coronary angiography (28)5.6.1.1Pattern of coronary artery disease (28)5.6.1.2Identification of the culprit lesion (28)5.6.1.3Fractionalflow reserve (29)5.6.2Routine invasive vs.selective invasive approach (29)5.6.3Timing of invasive strategy (29)5.6.3.1Immediate invasive strategy(,2h) (29)5.6.3.2Early invasive strategy(,24h) (29)5.6.3.3Invasive strategy(,72h) (30)5.6.3.4Selective invasive strategy (30)5.6.4Conservative treatment (30)5.6.4.1In patients with coronary artery disease (30)5.6.4.1.1Non-obstructive CAD (30)5.6.4.1.2CAD not amenable to revascularization (31)5.6.4.2In patients with normal coronary angiogram(see Web addenda) (31)5.6.5Percutaneous coronary intervention (31)5.6.5.1Technical aspects and challenges (31)5.6.5.2Vascular access (31)5.6.5.3Revascularization strategies and outcomes (32)5.6.6Coronary artery bypass surgery (32)5.6.6.1Timing of surgery and antithrombotic drugdiscontinuation(see Web addenda) (32)5.6.6.2Recommendations for perioperativemanagement of antiplatelet therapy in non-ST-elevationartery bypass surgery (32)5.6.6.3Technical aspects and outcomes(see Web addenda) (33)5.6.7Percutaneous coronary intervention vs.coronaryartery bypass surgery (33)5.6.8Management of patients with cardiogenic shock (33)5.6.9Recommendations for invasive coronary angiographyand revascularization in non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes (34)5.7Gender specificities(see Web addenda) (34)5.8Special populations and conditions(see Web addenda).345.8.1The elderly and frail patients(see Web addenda)..345.8.1.1Recommendations for the management ofelderly patients with non-ST-elevation acute coronarysyndromes (34)5.8.2Diabetes mellitus(see Web addenda) (35)5.8.2.1Recommendations for the management ofdiabetic patients with non-ST-elevation acute coronarysyndromes (35)5.8.3Chronic kidney disease(see Web addenda) (35)5.8.3.1Dose adjustment of antithrombotic agents(see Web addenda) (35)5.8.3.2Recommendations for the management ofpatients with chronic kidney disease and non-ST-elevation acute coronary systems (35)5.8.4Left ventricular dysfunction and heart failure(seeWeb addenda) (36)5.8.4.1Recommendations for the management ofpatients with acute heart failure in the setting of non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes (36)5.8.4.2Recommendations for the management ofpatients with heart failure following non-ST-elevationacute coronary syndromes (36)5.8.5Atrialfibrillation(see Web addenda) (37)5.8.5.1Recommendations for the management of atrialfibrillation in patients with non-ST-elevation acutecoronary syndromes (37)5.8.6Anaemia(see Web addenda) (37)5.8.7Thrombocytopenia(see Web addenda) (37)5.8.7.1Thrombocytopenia related to GPIIb/IIIainhibitors(Web addenda) (37)5.8.7.2Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia(Webaddenda) (37)5.8.7.3Recommendations for the management ofthrombocytopenia in non-ST-elevation acute coronarysyndromes (37)5.8.8Patients requiring chronic analgesic or anti-inflammatory treatment(see Web addenda) (37)5.8.9Non-cardiac surgery(see Web addenda) (37)5.9Long-term management (38)5.9.1Medical therapy for secondary prevention (38)5.9.1.1Lipid-lowering treatment (38)5.9.1.2Antithrombotic therapy (38)5.9.1.3ACE inhibition (38)5.9.1.4Beta-blockers (38)by guest on August 29, 2015Downloaded from5.9.1.7Glucose-lowering therapy in diabetic patients ..385.9.2Lifestyle changes and cardiac rehabilitation .......385.9.3Recommendations for long-term management after non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes .........386.Performance measures ..........................397.Summary of management strategy ...................398.Gaps in evidence ..............................419.To do and not do messages from the guidelines..........4110.Web addenda and companion documents.............4211.Acknowledgements.........................4212.Appendix ..................................4213.References ..............................43Abbreviations and acronymsACCAmerican College of CardiologyACCOASTComparison of Prasugrel at the Time of Percutaneous Coronary Intervention or as Pretreatment at the Time of Diagnosis in Patients with Non-ST Elevation Myocardial InfarctionACE angiotensin-converting enzyme ACS acute coronary syndromes ACT activated clotting timeACTION Acute Coronary Treatment and Intervention Outcomes NetworkACUITY Acute Catheterization and Urgent Interven-tion Triage strategYADAPT-DES Assessment of Dual AntiPlatelet Therapy with Drug-Eluting Stents ADP adenosine diphosphateAHAAmerican Heart AssociationAPPRAISE Apixaban for Prevention of Acute Ischaemic EventsaPTT activated partial thromboplastin time ARBangiotensin receptor blockerATLAS ACS 2-TIMI 51Anti-Xa Therapy to Lower Cardiovascular Events in Addition to Aspirin With or With-out Thienopyridine Therapy in Subjects with Acute Coronary Syndrome –Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction 51ATP adenosine triphosphateBARC Bleeding Academic Research Consortium BMS bare-metal stentCABG coronary artery bypass graft CADcoronary artery diseaseCHA 2DS 2-VAScCardiac failure,Hypertension,Age ≥75(2points),Diabetes,Stroke (2points)–Vascular disease,Age 65–74,Sex category CHAMPIONCangrelor versus Standard Therapy to Achieve Optimal Management of Platelet InhibitionCI confidence interval CKcreatine kinaseCOX cyclooxygenaseCMR cardiac magnetic resonanceCPG Committee for Practice GuidelinesCREDOClopidogrel for the Reduction of Events During ObservationCRUSADE Can Rapid risk stratification of Unstable an-gina patients Suppress ADverse outcomeswith Early implementation of the ACC/AHA guidelinesCT computed tomography CURE Clopidogrel in Unstable Angina to PreventRecurrent EventsCURRENT-OASIS 7Clopidogrel and Aspirin Optimal Dose Usage to Reduce Recurrent Events–Seventh Organ-ization to Assess Strategies in IschaemicSyndromesCV cardiovascular CYP cytochrome P450DAPT dual(oral)antiplatelet therapy DES drug-eluting stent EARLY-ACS Early Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa Inhibition inNon-ST-Segment Elevation Acute Coronary SyndromeECG electrocardiogram eGFR estimated glomerular filtration rate EMA European Medicines Agency ESC European Society of Cardiology FDA Food and Drug Administration FFR fractional flow reserve FREEDOM Future Revascularization Evaluation inPatients with Diabetes Mellitus:Optimal Management of Multivessel DiseaseGPIIb/IIIa glycoprotein IIb/IIIa GRACE 2.0Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events 2.0GUSTO Global Utilization of Streptokinase and TPAfor Occluded ArteriesGWTG Get With The Guidelines HAS-BLED hypertension,abnormal renal and liver func-tion (1point each),stroke,bleeding historyor predisposition,labile INR,elderly (.65years),drugs and alcohol (1point each)HIT heparin-induced thrombocytopenia HORIZONS Harmonizing Outcomes with Revasculariza-tiON and Stents in Acute Myocardial Infarction HR hazard ratio IABP-Shock II Intra-Aortic Balloon Pump in CardiogenicShock IIIMPROVE-IT IMProved Reduction of Outcomes:VytorinEfficacy International TrialINR international normalized ratio ISAR-CLOSURE Instrumental Sealing of ARterial puncturesite –CLOSURE device versus manual compressionISAR-REACT Intracoronary stenting and AntithromboticRegimen –Rapid Early Action for Coronary Treatmentby guest on August 29, 2015Downloaded from ISAR-TRIPLE Triple Therapy in Patients on Oral Anticoagula-tionAfter Drug Eluting Stent Implantationi.v.intravenousLDL low-density lipoproteinLMWH low molecular weight heparinLV left ventricularLVEF left ventricular ejection fractionMACE major adverse cardiovascular event MATRIX Minimizing Adverse Haemorrhagic Events byTRansradial Access Site and Systemic Imple-mentation of angioXMDCT multidetector computed tomography MERLIN Metabolic Efficiency With Ranolazine for LessIschaemia in Non-ST-Elevation Acute Coron-ary SyndromesMI myocardial infarctionMINAP Myocardial Infarction National Audit Project NOAC non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulant NSAID non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug NSTE-ACS non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes NSTEMI non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction NYHA New York Heart AssociationOAC oral anticoagulation/anticoagulantOASIS Organization to Assess Strategies for Ischae-mic SyndromesOR odds ratioPARADIGM-HF Prospective comparison of ARNI with ACEIto Determine Impact on Global Mortalityand morbidity in Heart FailurePCI percutaneous coronary intervention PEGASUS-TIMI54Prevention of Cardiovascular Events in Pa-tients with Prior Heart Attack Using Ticagre-lor Compared to Placebo on a Background ofAspirin-Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction54PLATO PLATelet inhibition and patient Outcomes POISE PeriOperative ISchemic EvaluationRCT randomized controlled trialRIVAL RadIal Vs femorAL access for coronaryinterventionRR relative riskRRR relative risk reductionSAFE-PCI Study of Access Site for Enhancement of PCIfor Womens.c.subcutaneousSTEMI ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction SWEDEHEART Swedish Web-system for Enhancement andDevelopment of Evidence-based care inHeart disease Evaluated According to Recom-mended TherapiesSYNERGY Superior Yield of the New Strategy of Enoxa-parin,Revascularization and Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa Inhibitors trialSYNTAX SYNergy between percutaneous coronaryintervention with TAXus and cardiac surgery TACTICS Treat angina with Aggrastat and determineCost of Therapy with an Invasive or Conser-vative Strategy TIA transient ischaemic attackTIMACS Timing of Intervention in Patients with AcuteCoronary SyndromesTIMI Thrombolysis In Myocardial InfarctionTRA2P-TIMI50Thrombin Receptor Antagonist in SecondaryPrevention of Atherothrombotic IschemicEvents–Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarc-tion50TRACER Thrombin Receptor Antagonist for ClinicalEvent Reduction in Acute CoronarySyndromeTRILOGY ACS Targeted Platelet Inhibition to Clarify the Op-timal Strategy to Medically Manage AcuteCoronary SyndromesTRITON-TIMI38TRial to Assess Improvement in TherapeuticOutcomes by Optimizing Platelet InhibitioNwith Prasugrel–Thrombolysis In MyocardialInfarction38TVR target vessel revascularizationUFH unfractionated heparinVKA vitamin K antagonistWOEST What is the Optimal antiplatElet and anti-coagulant therapy in patients with OAC andcoronary StenTingZEUS Zotarolimus-eluting Endeavor Sprint Stent inUncertain DES Candidates1.PreambleGuidelines summarize and evaluate all available evidence on a par-ticular issue at the time of the writing process,with the aim of assist-ing health professionals in selecting the best management strategies for an individual patient with a given condition,taking into account the impact on outcome,as well as the risk–benefit ratio of particu-lar diagnostic or therapeutic means.Guidelines and recommenda-tions should help health professionals to make decisions in their daily practice.However,thefinal decisions concerning an individual patient must be made by the responsible health professional(s)in consultation with the patient and caregiver as appropriate.A great number of Guidelines have been issued in recent years by the European Society of Cardiology(ESC)as well as by other soci-eties and organisations.Because of the impact on clinical practice, quality criteria for the development of guidelines have been estab-lished in order to make all decisions transparent to the user.The re-commendations for formulating and issuing ESC Guidelines can be found on the ESC website(/Guidelines-&-Education/Clinical-Practice-Guidelines/Guidelines-development/ Writing-ESC-Guidelines).ESC Guidelines represent the official pos-ition of the ESC on a given topic and are regularly updated. Members of this Task Force were selected by the ESC to re-present professionals involved with the medical care of patients with this pathology.Selected experts in thefield undertook a com-prehensive review of the published evidence for management (including diagnosis,treatment,prevention and rehabilitation)of a given condition according to ESC Committee for Practice Guide-lines(CPG)policy.A critical evaluation of diagnostic and therapeutic procedures was performed,including assessment of theESC Guidelines Page5of59by guest on August 29, 2015Downloaded fromrisk–benefit ratio.Estimates of expected health outcomes for larger populations were included,where data exist.The level of evidence and the strength of the recommendation of particular management options were weighed and graded according to predefined scales,as outlined in Tables1and2.The experts of the writing and reviewing panels provided declar-ation of interest forms for all relationships that might be perceived as real or potential sources of conflicts of interest.These forms were compiled into onefile and can be found on the ESC website(http:// /guidelines).Any changes in declarations of interest that arise during the writing period must be notified to the ESC and updated.The Task Force received its entirefinancial support from the ESC without any involvement from the healthcare industry.The ESC CPG supervises and coordinates the preparation of new Guidelines produced by task forces,expert groups or consensus pa-nels.The Committee is also responsible for the endorsement pro-cess of these Guidelines.The ESC Guidelines undergo extensive review by the CPG and external experts.After appropriate revi-sions the Guidelines are approved by all the experts involved in the Task Force.Thefinalized document is approved by the CPG for publication in the European Heart Journal.The Guidelines were developed after careful consideration of the scientific and medical knowledge and the evidence available at the time of their dating.The task of developing ESC Guidelines covers not only integration of the most recent research,but also the creation of educational tools and implementation programmes for the recom-mendations.To implement the guidelines,condensed pocket guidelines versions,summary slides,booklets with essential mes-sages,summary cards for non-specialists and an electronic version for digital applications(smartphones,etc.)are produced.These versions are abridged and thus,if needed,one should always refer to the full text version which is freely available on the ESC website.The National Societies of the ESC are encouraged to endorse, translate and implement all ESC Guidelines.Implementation pro-grammes are needed because it has been shown that the outcome of disease may be favourably influenced by the thorough applica-tion of clinical recommendations.Surveys and registries are needed to verify that real-life daily prac-tice is in keeping with what is recommended in the guidelines,thus completing the loop between clinical research,writing of guidelines, disseminating them and implementing them into clinical practice. Health professionals are encouraged to take the ESC Guidelines fully into account when exercising their clinical judgment,as well as in the determination and the implementation of preventive,diagnos-tic or therapeutic medical strategies.However,the ESC Guidelines do not override in any way whatsoever the individual responsibility of health professionals to make appropriate and accurate decisions in consideration of each patient’s health condition and in consult-ation with that patient and the patient’s caregiver where appropriate and/or necessary.It is also the health professional’s responsibility to verify the rules and regulations applicable to drugs and devices at the time of prescription.by guest on August 29, 2015Downloaded from 2.Introduction2.1Definitions,pathophysiology and epidemiologyThe leadingsymptom that initiates the diagnostic and therapeutic cascade in patients with suspected acute coronary syndromes (ACS)is chest pain.Based on the electrocardiogram (ECG),two groups of patients should be differentiated:(1)Patients with acute chest pain and persistent (.20min)ST-segment elevation.This condition is termed ST-elevation ACS and generally re-flects an acute total coronary occlusion.Most patients will ultim-ately develop an ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI).The mainstay of treatment in these patients is immediate reperfusion by primary angioplasty or fibrinolytic therapy.1(2)Patients with acute chest pain but no persistent ST-segmentelevation.ECG changes may include transient ST-segment elevation,persistent or transient ST-segment depression,T-wave inver-sion,flat T waves or pseudo-normalization of T waves or the ECG may be normal.The clinical spectrum of non-ST-elevation ACS (NSTE-ACS)may range from patients free of symptoms at presentation to individuals with ongoing ischaemia,electrical or haemodynamic instability or cardiac arrest.The pathological correlate at the myocardial level is cardiomyocyte necrosis [NSTE-myocardial infarction (NSTEMI)]or,less frequently,myocardial ischaemia without cell loss (unstable angina).A small proportion of patients may present with ongoing myocardial ischaemia,characterized by one or more of the follow-ing:recurrent or ongoing chest pain,marked ST depression on 12-lead ECG,heart failure and haemodynamic or electrical instabil-ity.Due to the amount of myocardium in jeopardy and the risk of malignant ventricular arrhythmias,immediate coronary angiography and,if appropriate,revascularization are indicated.2.1.1Universal definition of myocardial infarctionAcute myocardial infarction (MI)defines cardiomyocyte necrosis in a clinical setting consistent with acute myocardial ischaemia.2A combination of criteria is required to meet the diagnosis of acute MI,namely the detection of an increase and/or decrease of a cardiac biomarker,preferably high-sensitivity cardiac troponin,with at least one value above the 99th percentile of the upper reference limit and at least one of the following:(1)Symptoms of ischaemia.(2)New or presumed new significant ST-T wave changes or leftbundle branch block on 12-lead ECG.(3)Development of pathological Q waves on ECG.(4)Imaging evidence of new or presumed new loss of viable myo-cardium or regional wall motion abnormality.(5)Intracoronary thrombus detected on angiography or autopsy.2.1.1.1Type 1MIType 1MI is characterized by atherosclerotic plaque rupture,ulcer-ation,fissure,erosion or dissection with resulting intraluminal thrombus in one or more coronary arteries leading to decreasedmyocardial blood flow and/or distal embolization and subsequent myocardial necrosis.The patient may have underlying severe coron-ary artery disease (CAD)but,on occasion (i.e.5–20%of cases),there may be non-obstructive coronary atherosclerosis or no angio-graphic evidence of CAD,particularly in women.2–52.1.1.2Type 2MIType 2MI is myocardial necrosis in which a condition other than cor-onary plaque instability contributes to an imbalance between myo-cardial oxygen supply and demand.2Mechanisms include coronary artery spasm,coronary endothelial dysfunction,tachyarrhythmias,bradyarrhythmias,anaemia,respiratory failure,hypotension and se-vere hypertension.In addition,in critically ill patients and in patients undergoing major non-cardiac surgery,myocardial necrosis may be related to injurious effects of pharmacological agents and toxins.6The universal definition of MI also includes type 3MI (MI resulting in death when biomarkers are not available)and type 4and 5MI (related to percutaneous coronary intervention [PCI]and coronary artery bypass grafting [CABG],respectively).2.1.2Unstable angina in the era of high-sensitivity cardiac troponin assaysUnstable angina is defined as myocardial ischaemia at rest or minimal exertion in the absence of cardiomyocyte necrosis.Among unse-lected patients presenting with suspected NSTE-ACS to the emer-gency department,the introduction of high-sensitivity cardiac troponin measurements in place of standard troponin assays resulted in an increase in the detection of MI ( 4%absolute and 20%relative increase)and a reciprocal decrease in the diagnosis of unstable an-gina.7–10Compared with NSTEMI patients,individuals with unstable angina do not experience myocardial necrosis,have a substantially lower risk of death and appear to derive less benefit from intensified antiplatelet therapy as well as early invasive strategy.2–4,6–132.1.3Pathophysiology and epidemiology (see Web addenda)3.Diagnosis3.1Clinical presentationAnginal pain in NSTE-ACS patients may have the following presentations:†Prolonged (.20min)anginal pain at rest;†New onset (de novo)angina (class II or III of the Canadian Car-diovascular Society classification);21†Recent destabilization of previously stable angina with at least Canadian Cardiovascular Society Class III angina characteristics (crescendo angina);or †Post-MI angina.Prolonged and de novo/crescendo angina are observed in 80%and 20%of patients,respectively.Typical chest pain is character-ized by a retrosternal sensation of pressure or heaviness (‘angina’)radiating to the left arm (less frequently to both arms or to the right arm),neck or jaw,which may be intermittent (usually lasting several minutes)or persistent.Additional symptoms such as sweating,nau-sea,abdominal pain,dyspnoea and syncope may be present.AtypicalESC GuidelinesPage 7of 59by guest on August 29, 2015Downloaded from 。

2015年《中国急性ST段抬高型心肌梗死诊断治疗指南》要点解读

·专题研究·【编者按】 急性ST 段抬高心肌梗死(STEMI )是临床上常见的急症,如何有效降低急性STEMI 的各种并发症和死亡率,是医学界的研究热点。

早期再灌注治疗可以有效挽救生命,改善预后。

国内外不断更新急性心肌梗死的治疗指南以便更好地指导临床工作,如2012年8月欧洲心脏病学会(ESC )公布的《急性STEMI 处理指南》以及2012年12月美国心脏病学基金会(ACCF )和美国心脏协会(AHA )联合发表的《2013年美国ACCF /AHA 急性STEMI 治疗指南》中,有很多新的亮点,例如急性STEMI 的处理流程、再灌注治疗以及抗血栓、抗凝治疗等。

本期专题研究则对发表在中华心血管杂志上的2015年《中国急性ST 段抬高心肌梗死(STEMI )诊断治疗指南》进行了要点解读,指出完全再灌注治疗的急救转运流程在整个急性STEMI 诊疗过程中的重要性。

同时,本期专题研究还探讨了替罗非班在急性STEMI 行经皮冠状动脉介入(PCI )术中的安全性、有效性,指出高剂量替罗非班可降低患者主要不良心脏事件(MACE )发生率,为临床及全科用药提供参考。

更多精彩内容请关注本期专题研究。

2015年《中国急性ST 段抬高型心肌梗死(STEMI )诊断治疗指南》要点解读范书英作者单位:100029北京市,中日友好医院心内科【摘要】 本文从急性ST 段抬高型心肌梗死(STEMI )的急救转运流程、再灌注治疗和抗血栓治疗3个方面重点介绍了2015年中国急性STEMI 的诊疗更新要点,指出完全再灌注治疗的急救转运流程在整个急性STEMI 诊疗中非常重要,是缩短总体缺血时间,保证患者得到完全再灌注治疗的基础和保障。

【关键词】 心肌梗死;血管成形术,气囊,冠状动脉;ST 段;指南【中图分类号】R 542.11 【文献标识码】A doi :10.3969/j.issn.1007-9572.2015.27.003 范书英.2015年《中国急性ST 段抬高型心肌梗死(STEMI )诊断治疗指南》要点解读[J ].中国全科医学,2015,18(27):3268-3269,3275.[ ]Fan SY.2015Chinese guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of acute STEMI [J ].Chinese General Practice ,2015,18(27):3268-3269,3275.2015Chinese Guideline for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute STEMI FAN Shu -ying.China -Japan Friendship Hospital ,Beijing 100029,China【Abstract 】 The paper introduced the 2015updated Chinese guideline for STEMI treatment from the aspects of first -aidprocedure of acute STEMI ,reperfusion therapy and antiplatelet therapy.It pointed out that the first -aid procedure of complete reperfusion therapy is very important in the entire treatment of acute STEMI and it reduces total ischemia time and ensures STEMI patients get complete reperfusion treatment.【Key words 】 Myocardial infarction ;Angioplasty ,balloon ,coronary ;ST segment ;Guidebooks 2015年《中国急性ST 段抬高型心肌梗死(STEMI )诊断治疗指南》(简称《急性STEMI 新指南》)发表在中华心血管病杂志上。

非ST段抬高性急性冠脉综合症(NSTE-ACS )ESC指南(全文)

非ST段抬高性急性冠脉综合症(NSTE-ACS )ESC指南(全文)ESC组织在EuroPCR2007会上正式公布了对于非ST段抬高的ACS 的新治疗指南。

Jean-Pierre Bassand教授—ESC副主席说到:“这些指南内容体现了ESC主力近两年的辛勤劳作。

以前的指南从2002年起就存在大量的药理学方面的新资料,包括抗血小板药和抗凝药,及普通肝素和低分子肝素中新出现的fondaparinux(新型的选择性Ⅹa抑制剂)和比伐卢定。

在起草这些指南的过程中,介入方面的资料和治疗策略也得到了深入研究。

”指南中覆盖的临床事件不仅仅是以前所涉及的,还包括并发症的治疗。

在众多新出现的临床事件中,出血事件至关重要。

另外,糖尿病、高龄、贫血、慢性肾病、性别等问题都是新指南中的重要组成部分。

关于诊断和危险分层的推荐--对NSTE-ACS的诊断和短期危险分层应该综合考虑其病史、症状、ECG、生物标志物和危险积分(I-B)--对个人危险性的评估是一个动态过程,应随临床状况及时更新。

--患者就诊时,要在10分钟内为其做12导联心电图,并由有经验的内科医生查看心电图(I-C)。

对附加导联(V3R 及V4R, V7-V9)也应该有记录。

症状再发时及之后6小时、24小时和出院前都应有心电图记录(I-C)。

--应迅速检查肌钙蛋白(cTnT或cTnL),最好能在60分钟内得到检验结果(I-C)。

如果初次检验结果阴性,则应在6-12小时之后重复检验(I-A)。

--对初期和后期的危险评估应使用确立的危险积分评估法(如GRACE)(I-B)。

--推荐超声心动图常规用于鉴别诊断(I-C)。

--对于没有再发胸痛、心电图正常、肌钙蛋白阴性的患者,推荐应用非侵入性的负荷试验诱导心肌缺血的方法检查(I-A)。

--危险分层中用来评估远期死亡或心梗的预测因素应含有:临床指标(年龄、心率、血压、killip分级、糖尿病、心梗或冠心病史),心电图(ST 段压低),实验室检查(肌钙蛋白、GFR/CrCI、胱抑素C、脑钠肽\N末端、脑钠肽前体和C反应蛋白),影像学检查结果(射血分数低、左主干病变、3支病变),危险积分结果(I-B)。

2015年ST抬高心肌梗死诊断治疗指南

我国城市和农村的冠心病死亡率均 呈上升趋势

中国心血管病报告2013

急性心梗救治的里程碑

< 1960s 保守治疗 院内死亡率 30%

1960s CCU 院内死亡率 15% 1980s 溶栓治疗 院内死亡率 <10%

1990s PCI 院内死亡率 < 5%

上述4项中,心电图变化和心肌损伤标志物峰值前移最重要。

(一)溶栓治疗

冠状动脉造影判断标准:

心肌梗死溶栓(TIMI)2或3级血流表示血管再通,TIMI 3级为完

全性再通,溶栓失败则梗死相关血管持续闭塞(TIMI 0~1级)。

(一)溶栓治疗

7.溶栓后处理

•对于溶栓后患者,无论临床判断是否再通,均应早期(3-24

后尽早呼叫"120"急救中心、及时就医,避免因自行用药 或长时间多次评估症状而延误治疗。缩短发病至FMC的时 间、在医疗保护下到达医院可明显改善STEMI的预后(Ⅰ, A)。

早期、快速、完全地开通梗死相关动脉是改善STEMI患者预后 的关键。

2.缩短自FMC至开通梗死相关动脉的时间

建立区域协同救治网络和规范化胸痛中心是缩短FMC至开通梗死相关动脉时 间的有效手段(Ⅰ,B)。 有条件时应尽可能在FMC后10 min内完成首份心电图记录,并提前电话通知 或经远程无线系统将心电图传输到相关医院(Ⅰ,B)。 确诊后迅速分诊,优先将发病12 h内的STEMI患者送至可行直接PCI的医院( 特别是FMC后90 min内能实施直接PCI者)(Ⅰ,A),并尽可能绕过急诊室和 冠心病监护病房或普通心脏病房直接将患者送入心导管室行直接PCI。

溶栓禁忌证(绝对禁忌证)

• (1)既往脑出血史或不明原因的卒中;

《ESC2015:非 ST 段抬高型急性冠脉综合征指南》解读

《ESC2015:非 ST 段抬高型急性冠脉综合征指南》解读发表时间:2016-06-02T15:53:48.993Z 来源:《中国医学人文》(学术版)2016年2月第3期作者:陈炎陈亚蓓陶荣芳[导读] 当地时间2015年8月29日-9月2日欧洲心脏病学会年会在英国伦敦举行。

全球2.7万余名医生参加了会议。

会议推出了5部指南陈炎1 陈亚蓓1 陶荣芳21.安徽省明光市中医院心内科 239400;2.安徽省明光市人民医院心内科 239400【摘要】本文介绍了2015ESC《非 ST 段抬高型急性冠脉综合征指南》。

【关键词】急性冠状动脉综合征,血管造影,抗凝,β阻滞剂,早期介入策略,糖蛋白IIb/IIIa抑制剂,指南,非ST段抬高心肌梗死,血小板抑制,不稳定性心绞痛The interpretation of 《2015 ESC guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation》.CHEN Yan,CHEN Yabei,TAO Rongfang.Department of cardiology,Mingguang Hospital of TCM,Mingguang,Anhui,239400,ChinaCorresponding author:CHEN Yan.Email:mgyc2394@Abstract:This paper introduced 《2015 ESC guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation》.Key words:Acute coronary syndromes;Angioplasty;Anticoagulation;Beta-blockers;Early invasive strategy;Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors;Guidelines;Non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction;Platelet inhibition;Unstable angina当地时间2015年8月29日-9月2日欧洲心脏病学会年会在英国伦敦举行。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

ESC2015 指南: 非ST 段抬高型急性冠脉综合征关于可疑非 ST 段抬高型急性冠脉综合征(ACS)患者的诊断、风险分层、影像学检查和心律监测的若干建议1. 诊断和风险分层(1)建议结合患者的病史、症状、重要体征、其他体格检查发现、 ECG 和实验室检查结果等,对患者进行基本诊断以及行短期的缺血和出血风险分层。

(I,A)(2)建议患者就诊后 10 min 内迅速行 12 导联 ECG 检查,并立即让有经验的医生查看结果。

为了防止症状复发或者诊断不明确,有必要再次行 12 导联ECG 检查。

(I,B)(3)如果标准导联 ECG 结果阴性,但仍然高度怀疑缺血性病灶的存在,建议增加 ECG 导联(V3R、V4R、V7-V9)。

(I,C)(4)建议检测心肌钙蛋白(敏感或者高敏法),且在 60 min 内获取结果。

(I,A)(5)如果有高敏肌钙蛋白的结果,建议行 0 h 和 3 h 的快速排查方案。

(I,B)(6)如果有高敏肌钙蛋白的结果以及确认可用 0 h/1 h 算法,建议行 0 h 和1 h 的快速排查和确诊方案。

如果前两次肌钙蛋白检测结果阴性但临床表现仍然提示 ACS,建议在 3-6 h 之后再做一次检查。

(I,B)(7)建议使用现有的风险分数来诊断评估患者病情。

(I,B)(8)如果患者预行冠脉造影,可考虑使用 CRUSADE 分数量化出血风险。

(Iib,B)2. 影像学检查(1)如果患者无复发胸痛、ECG 结果正常、心肌钙蛋白检查结果正常(最好是高敏),但仍然怀疑存在 ACS,建议行无创性的负荷试验诱发缺血,结果不理想再进一步考虑有创性的检查。

(I,A)(2)建议行超声心动图以评估局部和全左心室功能,以及确诊和排查鉴别诊断。

(I,C)(3)如果心肌钙蛋白和/或 ECG 结果阴性,但仍怀疑低中度 CAD,可考虑行MDCT 冠脉造影检查。

(IIa,A)3. 监测方法(1)建议持续监测心律,直到排除或确诊 NSTEMI。

(I,C)(2)建议将 NSTEMI 患者收入监护病房。

(I,C)(3)对于临床表现为心脏性心律失常的低危 NSTEMI 患者,建议行 24 h 心律监测或者 PCI。

(IIa,C)(4)对于临床表现为心脏性心律失常的中高危 NSTEMI 患者,建议行至少 24 h 的心律监测。

(IIa,C)(5)如果患者缺乏持续缺血的体征或症状,或许部分患者应考虑行不稳定型心绞痛的心律监测(例如疑似冠脉痉挛或提示相关心律失常的症状)。

(IIb,C)关于非 ST 段抬高型 ACS 的抗缺血药物的若干建议1. 如果患者持续表现缺血症状且无β受体阻滞剂的禁忌症,建议早期开始β阻剂治疗。

(I,B)2. 除非患者的心功能进展为 Kilip III 或者更高,建议持续使用β受体阻滞剂。

(I,B)3. 对于反复发作心绞痛的患者,建议舌下含服或者静脉给药,以快速缓解症状;对于反复发作的心绞痛、难控性高血压或者有心衰的体征的患者,建议静脉给药。

(I,C)4. 对于疑似或确诊冠脉痉挛性心绞痛的患者,建议选用钙通道阻滞剂和硝酸酯类药物,避免使用β受体阻滞剂。

(IIa,B)关于非 ST 段抬高型 ACS 患者应用抗血小板药物的若干建议1. 口服抗血小板药物治疗(1)对于所有没有禁忌症的患者,建议使用口服阿司匹林,初始计量为150-300 mg 以及维持剂量为 75-100 mg/天,长期给药,与治疗策略无关。

(I,A)(2)如果没有如重度的出血风险之类的禁忌症,建议在阿司匹林的基础上添加 P2Y12 抑制剂,维持治疗 12 个月。

(I,A)对于所有中高缺血风险(如心肌钙蛋白升高)的患者,无论初始治疗如何,即使前期已使用了氯匹格雷进行预治疗,若无禁忌症,建议停用氯匹格雷,换用替卡格雷(180 mg 符合剂量,90 mg,bid)。

(I,B)对于接下来准备做 PCI 的患者,建议使用普拉格雷(60 mg 符合剂量,10 mg/天)。

(I,B)对于无法服用替卡格雷或普拉格雷或者同时需要口服抗凝药物的患者,建议使用氯匹格雷(300-600 mg 负荷剂量,75 mg,qd)。

(I,B)(3)对于疑似有高出血风险且行 DES 植入的患者,建议在植入手术后行 3-6 短期的 P2Y12 抑制剂治疗方案。

(IIb,A)(4)对于冠脉解剖影像学资料尚未完善的患者,不建议使用普拉格雷。

(III,B)2. 静脉内抗血小板治疗(1)若在 PCI 术间出现紧急情况或者血栓栓塞,建议使用 GPIIb/IIIa 抑制剂。

(Iia,C)(2)对于预行 PCI 治疗,且之前未使用 P2Y12 抑制剂的患者,建议使用坎格瑞洛。

(Iib,A)(3)对于冠脉解剖影像学资料尚未完善的患者,不建议使用 GPIIb/IIIa 抑制剂。

(III,A)3. 长期 P2Y12 抑制剂治疗在仔细衡量患者的出血和缺血风险之后,可考虑在阿司匹林的基础上添加P2Y12 抑制剂,持续 1 年。

(Iib,A)4. 一般治疗建议(1)对于有高胃肠出血风险的患者,建议在 DAPT 方案的基础上添加质子泵抑制剂。

(I,B)(2)除非患者有缺血事件的高危因素且临床实施困难,若服用 P2Y12 抑制剂的患者预行非紧急非心脏的大手术,建议延期手术,替卡格雷或氯匹格雷停药后至少 5 天,普拉格雷至少 7 天。

(Iia,C)(3)如果非心脏手术无法推迟或者合并出血,建议停用 P2Y12 抑制剂,PCI 手术中植入裸金属支架和新一代的药物涂层支架分别停用药物至少 1 个月和 3 个月。

(Iib,C)关于非 ST 段抬高型 ACS 患者抗凝药物的若干建议1. 诊断期间,考虑到缺血和出血风险,建议肠道外抗凝药物。

(I,B)2. 无论管理策略如何,建议使用璜达肝癸钠(2.5 mg,皮下注射,qd),可取得最理想的效果和安全性。

(I,B)3. PCI 手术期间,建议将普通肝素+ GPIIb/IIIa 抑制剂换成比伐卢定(0.75 mg/Kg,静脉注射;术后 4 h 内注射剂量为 1.75 mg/Kg/h)。

(I,A)4. 若患者预行 PCI 且未服用任何抗凝药物,建议使用普通肝素,70-100 IU/Kg,静脉注射(如果同时使用 GPIIb/IIIa 抑制剂,则将剂量调整为 50-70 IU/Kg)。

(I,B)5. 对于正在服用璜达肝癸钠且预行 PCI 的患者,建议单独使用普通肝素,静脉注射(如果同时使用 GPIIb/IIIa 抑制剂,则将剂量调整为 50-60 IU/Kg 或者70-80 IU/Kg)。

(I,B)6. 如果璜达肝癸钠的效果不佳,建议换成低分子肝素(1 mg/Kg,bid)或者普通肝素。

(I,B)7. 对于预行 PCI 手术且术前皮下注射过了低分子肝素的患者,可以考虑继续使用低分子肝素。

(Iia,B)8. 在普通肝素治疗后,且有活化凝血时间作为参考的情况下,可考虑 PCI 术间大剂量给予普通肝素。

(IIb,B)9. 除非有其他用药指征,否则 PCI 术后都应考虑停止抗凝药物。

(Iia,C)10. 不建议切换普通肝素和低分子肝素。

(III,B)11. 对于既往无卒中或 TIA,但处于高缺血风险和低出血风险的 NSTEMI 患者,在停止胃肠外抗凝药物时候可以考虑使用利伐沙班(2.5 mg,bid,持续用药 1 年)。

(Iib,B)关于非 ST 段抬高型 ACS 患者联合使用抗血小板药物和抗凝药物的若干建议图 1. NSTE-ACS 和非瓣膜病变房颤患者的抗栓治疗方案1. 对于有确切口服抗凝药物(OAC)使用指征的患者,建议在抗血小板治疗的基础上添加 OAC。

(I,C)2. 不管治疗方案中 OAC 如何使用,建议对中高危患者早期行冠脉造影检查(24h 之内)。

(Iia,C)3. 不建议在冠脉造影前在 OAC 的基础上添加使用「阿司匹林+ P2Y12 抑制剂」的双联抗血小板疗法(DAPT)。

(III,C)对于预行冠脉支架植入的患者,建议如下:1. 抗凝药物(1)不管上一次非口服抗凝药物(NOAC)的服用时间如何,或者使用维生素K 拮抗剂(VKA)治疗的患者的 INR<2.5,建议 PCI 术间添加胃肠外抗凝药物治疗。

(I,C)(2)围手术期间,应考虑连续使用 VKA 或者 NOAC 行抗凝治疗。

(I,C)2. 抗血小板治疗(1)对于 NSTE-ACS和房颤患者,在冠脉支架植入术后,可以考虑将三联疗法更换为包括 P2Y12 抑制剂的 DAPT。

(Iia,C)(2)如果出血风险较低,可以考虑在维持「OAC+阿司匹林(75-100 mg/天)或氯匹格雷(75 mg/天)」双联疗法 12 个月之后,行「OAC+阿司匹林(75-100 mg/天)+氯匹格雷(75 mg/天)」三联疗法,维持治疗 6 个月。

(Iia,C)(3)如果出血风险较高,不管植入支架的类型如何,可以考虑在维持「OAC+阿司匹林(75-100 mg/天)或氯匹格雷(75 mg/天)」双联疗法 12 个月之后,行「OAC+阿司匹林(75-100 mg/天)+氯匹格雷(75 mg/天)」三联疗法,维持治疗 1 个月。

(Iib,C)(4)对于部分特殊患者,可以考虑将三联疗法更换为「OAC+氯匹格雷(75 mg/天)」双联疗法。

(Iib,B)(5)不建议将替卡格雷或者普拉格雷列入三联疗法方案。

(III,C)3. 血管穿刺路径和支架类型(1)对于冠脉造影和 PCI 手术,桡动脉路径优于股动脉。

(I,A)(2)对于需要服用 OAC 的患者,新型药物洗脱支架(DES)优于裸金属支架(BMS)。

(Iia,B)4. 对于一般患者,可以考虑在 OAC 的基础上添加一种抗血小板药物,维持 1 年。

(Iia,C)关于非 ST 段抬高型 ACS 患者出血管理和输血的若干建议1. 对于因 VKA 相关出血事件而面临生命危险的患者,建议使用 IV 因子凝血酶原复合物快速逆转抗凝药物的作用,而不是选用新鲜冰冻血浆或者重组激活因子VII。

另外,若需要反复静脉注射维生素 K(10 mg),建议缓慢注射给药。

(Iia,C)2. 对于因 NOAC 相关持续出血事件而面临生命危险的患者,可以考虑使用凝血酶原复合物或者激活凝血酶原复合物。

(Iia,C)3. 对于贫血但无活动性出血证据的患者,如果出现血液动力学受损、血细胞比容<25% 或者血红蛋白水平低于 7 g/dL,可以考虑输血。

(Iib,C)关于非 ST 段抬高型 ACS 患者预行冠脉搭桥手术(CABG)围手术期的抗血小板治疗的若干建议1. 无论血管再通的策略如何,如果没有过分的出血风险等禁忌症,建议使用「阿司匹林+ P2Y12 抑制剂」的双联抗血小板疗法,维持治疗 12 个月。