robert frost

弗罗斯特(RobertFrost)诗品

弗罗斯特(Robert Frost)诗品Robert Frost(1874-1963),美国,作品以朴素、深邃著称。

主要诗集有《孩子的意愿》、《波士顿以北》、《新罕布什尔》.《西去的溪流》、《理智的假面具》、《慈悲的假面具》、《林间中地》等。

Neither Out Far Nor In Deep□不深也不远The people along the sandAll turn and look one way.They turn their back on theland.They look at the sea all day.As long as it takes to passA ship keeps raising itshull。

The wetter ground like glassReflects a standing gull人们走上沙滩转身朝着一个方向。

他们背对着陆地整日凝望海洋。

当一只船从远处过来船身便不断升高;潮湿的沙滩像明镜映出一只静立的鸟。

The land may vary more。

But wherever the truth may be--The water comes ashore,And the people look at the sea.They cannot look out far.They cannot look in deep.But when was that ever a barTo any watch they keep?也许陆地变化更多;但无论真相在哪边——海水涌上岸来,人们凝望着海洋。

他们望不太深。

他们望不太远。

但有什么能够遮挡他们凝望的目光?The Road Not Taken□ 未选择的路Two roads diverged in a yellow wood, And sorry I could not travel bothAnd be one traveler, long I stoodAnd looked down one as far as I could To where it bent in the undergrowth。

罗伯特弗罗斯特的历史故事

罗伯特弗罗斯特的历史故事罗伯特弗罗斯特(Robert Frost)是美国著名的诗人和散文家,他以写作具有深刻哲理和富有意境的作品而闻名于世。

他的历史故事不仅仅是关于他个人的生平经历,更是关于时间、光阴和人生的深刻思考。

本文将围绕罗伯特弗罗斯特的历史故事展开探讨,带领读者一起领略他的文学世界。

一、早年的艰辛罗伯特弗罗斯特于1874年生于美国加州,他的童年时光充满了艰辛和挑战。

在早年,他的父亲因事业失败而去世,家庭陷入了经济困境。

年幼的罗伯特不得不与家人一起辛勤劳作,帮助维持生计。

这段经历不仅磨砺了他的意志,也深深地影响了他后来的创作。

二、诗歌创作的初试尽管早年的生活并不轻松,但罗伯特对于诗歌的兴趣却从未减退。

年少的他就喜欢读诗,积极尝试着用自己的笔触创作。

早期的作品虽然并未获得广泛的认可,但却奠定了他后来成为伟大诗人的基础。

三、挫折与成功虽然罗伯特经历了许多挫折,但他并没有放弃自己的梦想。

在他40岁左右的时候,他的诗歌终于开始获得了大众的关注和赞赏。

他的作品《小路不选》被广泛传播,成为他最著名的作品之一。

从那时起,罗伯特弗罗斯特的诗歌创作迎来了巅峰时期。

四、诗歌中的哲学思考罗伯特弗罗斯特的诗歌作品经常描绘出人类生活中的困境和挣扎,引发读者们对人生和存在的思考。

他的作品透露着深邃的哲学意味,让人们不仅仅被其美丽的文字所吸引,更是被其寓意所震撼。

五、文学成就和影响罗伯特弗罗斯特被誉为20世纪美国最伟大的诗人之一,他的作品对于当代文学产生了深远的影响。

他充满哲理和意境的创作方式,使他的作品跨越时空,传承至今。

六、结语罗伯特弗罗斯特的历史故事是一个关于执着和坚持的故事,他在面对困难和挫折时从未放弃自己的梦想。

通过他的作品,我们也可以感受到人生的真谛和哲理。

罗伯特弗罗斯特的创作不仅表达了个人的情感和思考,更是反映了人类普遍的追求和探索。

以上是关于罗伯特弗罗斯特的历史故事的一些论述,通过深入了解他的作品和生平经历,我们可以更好地理解他的文学成就和影响。

美国诗人弗罗斯特的个人简介

美国诗人弗罗斯特的个人简介

弗罗斯特(Robert Frost)(1874~1963)美国诗人。

1874年3月26日生于美国西部的旧金山。

他11岁丧父,后随母亲迁居东北部的.新英格兰。

此后,他就与那块土地结下了不解之缘。

弗罗斯特16岁开始写诗,20岁时正式发表第一首诗歌。

他勤奋笔耕,一生中,共出了10多本诗集,其中主要的有《波士顿以北》(1914),《山间》(1916),《新罕布什尔》(1923),《西流的小溪》(1928),《见证树》(1942)以及《林间空地》(1962)等。

对人类的恩惠,另一方面也写了其破坏力以及给人类带来的不幸和。

弗罗斯特诗歌风格上的一个最大特点是朴素无华,含义隽永,寓深刻的思考和哲理于平淡无奇的内容和简洁朴实的诗句之中。

这既是弗罗斯特的艺术追求,也是他事业成功的秘密所在。

罗伯特弗罗斯特诗意人生的美国诗人

罗伯特弗罗斯特诗意人生的美国诗人罗伯特弗罗斯特(Robert Frost)是20世纪美国最著名的诗人之一,他的作品以其深邃的哲理、优美的语言和丰富的意象而著称。

他的诗歌主题涉及人类生活、自然景观以及人与自然的关系,流露出对生命、时间和命运的思考,传递出一种诗意的哲学理念。

本文以探索罗伯特弗罗斯特诗意人生的美国诗人为主题,旨在展示他的作品背后所蕴含的美学和人生哲学。

一、探索自然与人的关系自然是弗罗斯特诗歌的核心主题之一,他通过独特的视角描绘了大自然的美丽与雄伟。

他的诗歌中常以山峰、森林、溪流等自然景观为背景,展示了自然对人的影响和人对自然的感悟。

例如在《雪夜》中,他运用雪的意象描绘了大自然中的静谧与纯净,同时将其与个体命运相联系,表达出人在自然面前的渺小感。

通过这种自然与人的交织,弗罗斯特赋予了他的诗歌深刻的思想内涵。

二、人生旅程与选择弗罗斯特的作品经常探索人生的旅程和选项。

他的诗歌展示了生命中的岔路口和选择,以及这些选择对人们命运的影响。

在《两条路》中,他描述了一个人在两条小路径之间的选择,表达了选择对一个人一生的决定性影响。

通过这种描绘,弗罗斯特表达了对人们在人生道路上作出决策的思考和追问。

三、时间与回忆时间是弗罗斯特的另一个重要主题,他在诗中经常探索回忆和过去的力量。

他的作品描绘了时光对人事物带来的变化和衰败。

在《路过枯枝》中,他以一片枯死的枝叶描绘了时间的流逝和生命的脆弱。

通过这样的描写,弗罗斯特引起读者对时间流逝和生命短暂性的思考。

四、农民与劳动弗罗斯特的作品中经常描绘农民和农业生活,他赞美劳动的价值和农村生活的简朴。

通过描绘农民的生活和劳动场景,他传递了对劳动的赞美和对社会价值观的思考。

在他的诗歌中,农民被描绘为坚韧不拔、坚持不懈的人物,他们代表了简单与真实的价值观。

五、存在主义和孤独弗罗斯特的作品中有着存在主义的影子,他对人生的不可避免的孤独和存在的不确定性进行了深刻的思考。

例如在《雨夜的书屋》中,他描绘了一个人孤独的身影在墓地荒凉的房子里独自度过夜晚。

(4)弗罗斯特(Robert?Frost)诗选

(4)弗罗斯特(Robert Frost)诗选弗罗斯特(1874-1963),主要诗集有《孩子的意愿》、《波士顿以北》、《新罕布什尔》.《西去的溪流》、《理智的假面具》、《慈悲的假面具》、《林间中地》等。

《出生地》和那远处的山坡相比这儿似乎没有过任何的希望,父亲建造小屋,拢起了泉水,用围墙般的锁链围住所有东西。

周围的地面不只长荒草,还维持了我们各自的生命。

我们有十二个女孩和男孩。

高山似乎喜欢这热闹,用很短的时间就了解了我们——它的微笑总像含着什么,也许到今天它还是不知道我们的名字。

(当然没有一个女孩保持着原样。

)高山使我们从它的怀里离开,而现在它的山坳满是树木。

《一个老人的冬天夜晚》外面所有一切都穿过那空房间薄雾朦胧的窗格玻璃,穿过几乎呈星形分开的凝霜窥看他,是那在手上朝眼睛倾斜的灯光使他没有反看回去。

是年龄使他不能再记起把自己带到那摇摇欲坠房间的原因。

他与围绕自己的桶站在一起——不知所措。

他用沉重的脚步吓唬脚底的地下室,又用脚步将它吓了一跳;——又惊吓外面那有着它声音的夜晚,那声音熟悉得如同树枝破裂,但更像击打盒子。

他其实是仅仅照着他自己的灯,那个现在坐着的,与他所了解有关的轻微灯光,甚至连灯都谈不上。

他委托月亮,虽然是像他那样那么晚起来,那么残缺不全的月亮,但要它让他的雪花在屋顶上,让冰柱围绕墙,任何时候它的这种保管的职责都比太阳强,这时他睡着了。

那炉子里的圆木移动了一下,似乎打扰了他,他也动了一下,放松了他那沉重的呼吸,但他依然沉睡。

一个年老的人——一个人——不能看守一间房子,一个农场,一个农村,或者即使他能够,也是因为他在一个冬天夜晚所能做的。

《妻子》孤独(她的话)一个人不该关心那么多如同你和我在鸟儿来到房子周围似乎说再见之时所关心的;或者当它们回来唱着我们不懂的歌那样关心;真理就是我们为一件事感到过于高兴而这里为另一件事而悲伤——鸟儿的胸怀所填满的就是彼此与它们自己以及它们那建造或离开的鸟巢。

robert frost 写作手法

robert frost 写作手法[Robert Frost 写作手法]罗伯特·弗罗斯特(Robert Frost)被公认为20世纪最伟大的美国诗人之一。

他的作品以其简洁自然、生动形象和深邃哲理而闻名。

弗罗斯特是一位优秀的写实主义诗人,他的写作手法自成一派,独具魅力。

本文将一步一步地回答关于弗罗斯特写作手法的问题。

问题1:弗罗斯特的作品风格如何?弗罗斯特的作品风格以明快简洁、自然生动为主。

他善于使用通俗易懂的语言和生动形象的比喻,使读者能够轻松理解他的作品。

他常常描绘农村景色,通过细腻的描写和对自然的观察,使作品充满深情和哲理。

问题2:弗罗斯特如何运用意象和比喻?弗罗斯特以其独特的意象和比喻手法而闻名。

通过使用平凡生活中的对象和场景,他能够传达出深刻的哲理和情感。

例如,在他的诗歌《树木》中,他通过描写树木的成长和变化,寓意人生的起伏和变迁。

弗罗斯特还善于使用自然界的比喻来表达人类的情感和思想。

例如,在《停下来深思》中,他用“两条路”来比喻人生的选择和决策。

问题3:弗罗斯特的诗意言简如何体现?弗罗斯特的诗歌以其简洁而含义深刻的表达方式而闻名。

他善于用简单的句子和平实的语言来表达复杂的思想和情感。

这种简洁形式的使用使读者更易于理解和共鸣。

同时,他经常使用隐晦的形象和修辞手法,以引发读者的想象力和思考。

问题4:弗罗斯特如何平衡写实主义与象征主义?弗罗斯特的作品既具有写实主义的特点,又充满象征主义的意味。

他通过真实的物象和情节来表达人类的内心体验和社会现实。

同时,他也运用象征主义的手法来强调更深层次的主题和哲理。

这种平衡使他的作品不仅充满了现实感,同时也具有更深远的意义。

问题5:弗罗斯特的作品中常见的主题有哪些?弗罗斯特的作品涉及了多种主题,如人类生活和自然的关系、人生选择和决策、孤独和社交、时间和记忆等。

他常常通过探索这些主题来揭示人类的情感和思想。

例如,在《停下来深思》中,他通过两条路的象征来探讨人生中重要的选择。

罗伯斯特

作品风格罗伯特·弗罗斯特(RobertFrost,1874-1963)是最受人喜爱的美国诗人之一,留下了《林间空地》、《未曾选择的路》、《雪夜林边小驻》等许多脍炙人口的作品。

日前,美国弗吉尼亚大学的英语文学研究生罗伯特·斯蒂灵发现了一首从未发表过的弗罗斯特诗作,题为《家中的战争断想》(War Thought sat Home)。

在一封写于1947年的信件中,弗罗斯特向友人弗雷德里希·梅尔彻(FredericMelcher)提到了这首诗,后者是行业杂志《出版人周刊》的创办人。

弗罗斯特在信中说这首诗没有发表,而是手抄在一本《波士顿之北》(弗罗斯特出版的第二部诗作)上。

读到这封信之后,斯蒂灵就开始了搜寻工作,最终在学校图书馆里找到了这本书,弗罗斯特抄在书里的诗也因此面世。

这首诗作于1918年,是弗罗斯特为在法国战场上阵亡的英国诗人爱德华·托马斯(EdwardThomas,1878-1917)写的。

诗的内容是一名士兵的妻子看到几只蓝松鸦在自家窗外打斗,由此想到了法国战场上的士兵。

一战初期,弗罗斯特曾在英国居留,由此与托马斯成了朋友。

托马斯在前线阵亡的时候,身边还带着一本弗罗斯特的《山洼》(MountainInterval)。

作为一个现代诗人,在诗歌的形式上,弗罗斯特走出了一条与20世纪多数诗人迥然不同的道路。

他并没有标新立异,企图尝试诗歌形式的改革,而是继承传统,满足于用旧形式表达新内容。

他喜欢用浅显易懂的口语,语气平缓、冷静,采用人们熟悉的韵律。

他的诗一般都遵从了传统的韵律形式,比如押韵的双行体、三行体、四行体、十四行体都写的相当出色。

弗罗斯特很少写自由诗,他曾说过,诗歌如不讲韵律,就像打网球不设拦网一样。

他对抑扬格似乎情有独钟,他曾说:“对英语诗歌而言,抑扬格和稍加变化的抑扬格是唯一自然的韵律。

”的确,英诗四个主要音步——抑扬格、抑抑扬格、扬抑格、和扬抑抑格——中,抑扬格是迄今英诗中最常见的音步,从而也被称为最自然的韵律,即一个弱读音节后跟一个重读音节。

罗伯特弗罗斯特十首诗

罗伯特弗罗斯特十首诗

罗伯特·弗罗斯特(Robert

Frost)是美国著名的诗人,他的诗作以自然、人生哲理和农村生活为主题,深受广大读者喜爱。

以下是罗伯特·弗罗斯特的十首经典诗作:

1.《路》(The Road Not Taken)

2.《雪夜》(Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening)

3.《火与冰》(Fire and Ice)

4.《树木》(Tree at My Window)

5.《草木深处》(The Road Not Taken)

6.《在夏天失去的东西》(Something Lost in the Summer)

7.《牧人》(The Pasture)

8.《泥鳅》(The Fish)

9.《墙》(Mending Wall)

10.《锄地者》(The Tuft of Flowers)

这些诗作展现了弗罗斯特深刻的思想和细腻的表达方式,带给读者诗意盎然的体验。

每首诗作都有其独特的主题和意境,推荐您阅读并感受其中的美妙与深意。

罗伯特弗罗斯特美国现代诗歌的代表与创作

罗伯特弗罗斯特美国现代诗歌的代表与创作罗伯特·弗罗斯特(Robert Frost)是20世纪美国现代诗歌的代表性作家之一,他的作品充满着对大自然、生活与人类存在的思考与感悟。

本文将从弗罗斯特的代表作品、其对现代诗歌的影响以及他的创作风格等几个方面展开论述。

一、弗罗斯特的代表作品弗罗斯特的代表作品包括《松树》、《路未选择》、《停驻的雪》等,这些作品多以自然景观为背景,通过细腻的描写与抒情的笔调,表达了作家对人生、选择和面对困境的思考。

在《松树》中,弗罗斯特通过描绘一棵独立坚强的松树,表达了自然界力量与人类生命的共鸣,反映了自身与大自然的紧密联系。

《路未选择》以选择分岔路的场景为基础,通过描述主人公做出的选择,表达了对人生抉择与命运的思考。

《停驻的雪》则以一场下雪为背景,通过雪的静默无声与对生命的思考,拓展了人们对于时间与存在的认识。

这些作品以其丰富的意象、情感流露与寓意深远的主题,成为了弗罗斯特诗歌创作的代表,也对20世纪美国现代诗歌的发展与影响产生了深远的影响。

二、对现代诗歌的影响弗罗斯特的诗歌作品不仅在当时引起了广泛的共鸣与关注,也对现代诗歌的发展与演变产生了深远的影响。

首先,弗罗斯特的诗作具有深入人心的主题与情感表达。

他以朴素的语言和自然的意象,将复杂的人生哲理与普遍的人性关怀表现得淋漓尽致。

这种诗歌风格打破了传统意义上诗歌的艰涩与繁复,使诗歌更贴近普通读者的日常经验,使现代诗歌获得更多读者的认同与喜爱。

其次,弗罗斯特的作品在形式上也对现代诗歌产生了创新的影响。

他善于运用韵律、押韵与排比等修辞手法,使诗歌的音乐性更加突出,形成了独特而富有韵律感的写作风格。

他的作品以其平易近人的形式,积极推动了现代诗歌形式的多样化与开放性,为后来的诗人们提供了借鉴与启发。

三、弗罗斯特的创作风格弗罗斯特的创作风格以其写实与叙事的特点著称,他以简洁明了的语言描绘日常生活中的场景,通过对细节的关注与思考,探究生命的意义与存在的哲学。

ROBERT FROST

END

Байду номын сангаас

Works appreciation

The Road Not Taken

Oh, I kept the first for another day! Two roads diverged in a yellow wood, Yet knowing how way leads on to way, And sorry I could not travel both I doubted if I should ever And be one traveler, long I stood And looked down one as far as I could come back. I shall be telling this with a To where it bent in the undergrowth; sigh Then took the other, as just as fair, And having perhaps the better claim, Somewhere ages and ages hence, Because it was grassy and wanted Two roads diverged in a wear; wood,and I—I took the one Though as for that the passing there Had worn them really about the same, less traveled by, And that has made all the And both that morning equally lay difference In leaves no step had trodden black.

英汉对照-Robert Frost 部分诗选及简介

Robert Frost 部分诗选及简介耶鲁大学公开课现代诗歌讲师介绍:兰顿·哈默是耶鲁大学英语系主任,拥有耶鲁大学文学学士及哲学博士学位。

他是《哈特·克兰和艾伦·泰特:双面孔的现代派》的作者,《哦,我的祖国,我的友人:哈特·克兰书信选》和美国丛书《哈特·克兰诗歌全集与书信选》的编者。

作为古根海姆基金会的一员,兰顿·哈默近期的研究课题为诗人詹姆斯·梅利尔。

兰顿的新诗评论和文学批评文章常常发表在纽约时报书评和其他杂志上,并且他还是《美国学者》的诗歌编辑。

Langdon Hammer, chairman of the Department of English at Yale, earned his B.A. and Ph.D. from Yale. He is the author of Hart Crane and Allen Tate: Janus-Faced Modernism and editor of O My Land, My Friends: The Selected Letters of Hart Crane and the Library of America's, Hart Crane: Complete Poems and Selected Letters. A Guggenheim Fellow, he is currently at work on a biography of the poet James Merrill. His reviews of new poetry and literary criticism regularly appear in The New York Times Book Review and other magazines, and he is poetry editor of The American Scholar.Robert Frost(罗伯特·弗罗斯特1874~1963) PoetBorn: 26 March 1874Birthplace: San Francisco, CaliforniaDied: 29 January 1963Best Known As: American poet who wrote "The Road Not Taken"The poetry of Robert Frost combined pastoral imagery with solitary philosophical themes and was often associated with rural New England. Frost was one of the most popular poets in America during his lifetime and was frequently called the country's unofficial poet laureate. He was farming in Derry, New Hampshire when, at the age of 38, he sold the farm, uprooted his family and moved to England, where he devoted himself to his poetry. His first two books of verse, A Boy's Will (1913) and North of Boston (1914), were immediate successes. In 1915 he returned to the United States and continued to publish poems that were both popular and critical successes. His poems include "Mending Wall" ("good fences make good neighbors"), "Birches," "Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening" ("Whose woods these are I think I know"), and "The Road Not Taken." Frost was awarded the Pulitzer Prize four times: in 1924, 1931, 1937 and 1943. He also served as "Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress" from 1958-59; that position was renamed as "Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry" in 1986.Frost read his poem "The Gift Outright" at the 1961 inauguration of John F. Kennedy... Frost preferred traditional rhyme and meter in poetry; his famous dismissal of free verse was, "I'd just as soon play tennis with the net down."【FOUR GOOD LINKS】☆The Robert Frost Web Page/indexgood.htmlBiography, interviews and select poems★Robert Frost: America's Poet/frost/Timeline biography and several of his poems☆A Frost Bouquet/small/exhibits/frost/home.htmlTerrific exhibit from the University of Virginia★Frost in The Atlantic Monthly/doc/prem/199604u/frost-intro1996 profile that includes poems and readings弗罗斯特(Robert Frost)(1874~1963)美国诗人。

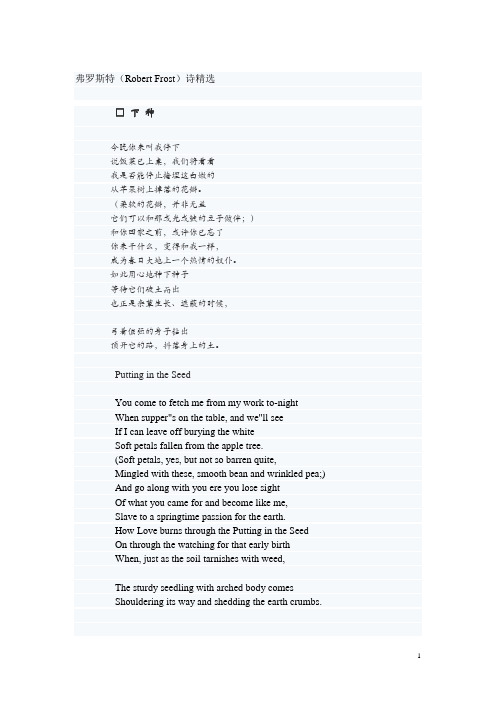

Robert Frost诗歌精选(双语)

弗罗斯特(Robert Frost)诗精选□下种今晚你来叫我停下说饭菜已上桌,我们将看看我是否能停止掩埋这白嫩的从苹果树上掉落的花瓣。

(柔软的花瓣,并非无益它们可以和那或光或皱的豆子做伴;)和你回家之前,或许你已忘了你来干什么,变得和我一样,成为春日大地上一个热情的奴仆。

如此用心地种下种子等待它们破土而出也正是杂草生长、遮蔽的时候,弓着倔强的身子钻出顶开它的路,抖落身上的土。

Putting in the SeedYou come to fetch me from my work to-nightWhen supper"s on the table, and we"ll seeIf I can leave off burying the whiteSoft petals fallen from the apple tree.(Soft petals, yes, but not so barren quite,Mingled with these, smooth bean and wrinkled pea;)And go along with you ere you lose sightOf what you came for and become like me,Slave to a springtime passion for the earth.How Love burns through the Putting in the SeedOn through the watching for that early birthWhen, just as the soil tarnishes with weed,The sturdy seedling with arched body comesShouldering its way and shedding the earth crumbs.□ 进来当我走到树林边,鸫鸟的音乐——听啊!如果这时外面还亮点,里面已是黑暗。

Robert Frost罗伯特·弗罗斯特 ppt课件

森林又暗又深真可羡, 但我还要守一些诺言, 还要赶多少路才安眠, 还要赶多少路才安眠。

Robert Frost罗伯特·弗罗斯特

这首诗的背景充满田园诗歌(pastoral poetry)的 风格。

内容在抒发作者心中矛盾的情绪,因此这首诗又 可以说是一首田园式的抒情诗(pastoral lyric poem)。

我的小马一定颇惊讶: 四望不见有什么农家, 偏是一年最暗的黄昏, 寒林和冰湖之间停下。

He gives his harness bells a shake To ask if there is some mistake. The only other sound’s the sweep Of easy wind and downy flake.

Published in 1916 in the collection Mountain Interval

每节R的o韵式b为eabratabF. rost罗伯特·弗罗斯特

1—3节为第一层,诗人描述了选择人迹罕至的路并不是草率决定的,而 是经历了复杂的心理历程。描述了“我”站在岔路口,为不能同时涉足 两条路而遗憾,写出“我”的犹豫和久久思索:一条路平坦通畅,极目 可望见它的尽头;而另一条路幽寂荒凉,充满着引人探索的诱惑,但 “无限美景在险峰”, “我”终于选择了那条人迹更少的路,就让另一 条路留待后日去走,这显然是作者做出抉择后的一种自我安慰,因为 “我知道路径延绵无尽头,/恐怕我难以再回返”,虽然如此,但依然 义无返顾。

从这首诗中象徵的意义上看来,这是一首有思想 的诗(a poem of idea),表现出作者对自然与人生 的看法。

全诗共分四节(stanzas),每节各四行(lines),每 一行 都是很规律的四步抑扬格 (iambic tetrameter)。押韵(rhyme)除最後一节外均为 /aaba/bbcb/ccdc/dddd/

罗伯特·弗罗斯特语录

罗伯特·弗罗斯特语录标题:罗伯特·弗罗斯特语录:探索人生的深度与意义引言:罗伯特·弗罗斯特(Robert Frost)是美国著名的诗人,他的作品以自然景观和人类生活为主题,深受世界各地读者的喜爱。

弗罗斯特的诗歌中蕴含着深度的思考和对人生的洞察,他的语录也成为了人们思考和探索人生意义的重要启示。

本文将以罗伯特·弗罗斯特的语录为线索,探讨人生的深度与意义。

一、选择之路:“两条路分叉在林间,我选择了人迹更少的那一条,这决定了一切。

”弗罗斯特在这句语录中,表达了人生中重要的选择之路。

每个人都会面临各种选择,而选择的道路将决定我们的人生轨迹。

弗罗斯特鼓励人们敢于选择不同寻常的道路,勇敢地追求自己的梦想和独特的人生道路。

二、自然与人生:“在自然中,我找到了生命的力量和智慧。

”弗罗斯特深受自然的启发,他的诗歌中经常描绘大自然的美丽和力量。

他认为自然是人们寻找生命意义和智慧的源泉。

在现代社会中,人们常常迷失在喧嚣和浮躁中,而忽略了与自然相连的重要性。

弗罗斯特的语录提醒我们,通过与自然亲近,我们可以重新发现生命的力量和智慧。

三、人际关系与孤独:“我喜欢和人们保持一定的距离,但我也害怕孤独。

”弗罗斯特在这句语录中表达了对人际关系和孤独的矛盾心理。

人际关系是人生中重要的一部分,但有时我们也需要独处,反思和探索自己的内心世界。

弗罗斯特的语录提醒我们,找到平衡,既要享受与他人的交流和互动,也要给自己留出空间和时间,独自思考和成长。

四、挫折与成长:“挫折是人生中必不可少的一部分,它们是我们成长和进步的机会。

”弗罗斯特的语录中透露出对挫折的理解和态度。

人生中难免会遇到挫折和困难,但正是这些挫折塑造了我们的性格和智慧。

弗罗斯特鼓励我们从挫折中学习和成长,将其视为人生中不可或缺的一部分。

结语:罗伯特·弗罗斯特的语录给予了我们对人生的深度思考和启示。

通过选择之路、自然与人生、人际关系与孤独以及挫折与成长等方面的探索,我们可以更好地理解人生的意义和价值。

罗伯特弗洛斯特自然与诗歌

罗伯特弗洛斯特自然与诗歌自然和诗歌是两个密不可分的概念,而罗伯特弗洛斯特作为一位伟大的美国诗人,将自然融入他的创作中,用诗歌表达了对自然的热爱和对人类与自然关系的思考。

本文将从弗洛斯特的生平背景、他对自然的感知以及其诗歌中的自然主题三个方面来探讨弗洛斯特自然与诗歌之间的联系。

首先,了解弗洛斯特的生平背景对于理解他对自然的热爱和思考是至关重要的。

罗伯特·弗洛斯特(Robert Frost,1874年3月26日-1963年1月29日)出生在美国,是20世纪最重要的美国诗人之一。

他的诗歌作品中常常展现出对乡村生活和自然的深情厚意。

他从小便在农村长大,与自然紧密相连。

这种与自然的亲密接触对他的诗歌创作产生了深远的影响。

弗洛斯特对自然的感知是他作品中最重要的主题之一。

他对自然的观察敏锐,从微小的自然元素中发现了深层次的意义。

例如,在他的一首著名诗作《疮痍》中,他描述了一棵树在寒冷的冬天中孤独地矗立,“这棵树/存活在冷曰,/几乎心脏被冻住,/疮痍树皮饱经风霜。

”这种描述揭示了人类与自然的共生关系,弗洛斯特通过描述树木的坚韧生命力来反映人类在严寒环境中的抵抗力量。

他用诗歌描绘了自然界中的细微之处,通过这种观察使得读者更深入地理解自然。

弗洛斯特的诗歌中充满了对自然的钦佩和热爱。

他的诗歌作品反映了他对大自然中各种景色的充满敬意。

例如,在《停靠之地》这首诗中,他写道:“树林乍见寒夜崭新亮光,/白色山头暴露在月光里。

”这里他将自然中的景色与光明和希望联系在一起,传达了对自然神秘和美丽的赞美之情。

弗洛斯特的诗歌往往展现了自然界中的宁静和和谐,这种和谐感传达到了读者心灵深处,使得读者能够融入到自然中。

此外,弗洛斯特的诗歌也反映了他对自然与人类关系的思考。

他关注人类在现代社会中与自然的冲突和错综复杂的关系。

例如,在他的著名诗作《大路东与法柜路途之中》中,他探讨了人类在现代化进程中与自然破坏之间的矛盾。

“两条路分岔开,我选择了人迹较少的路,/这调整了一切。

罗伯特·弗罗斯特语录(罗伯特·弗罗斯特)

罗伯特·弗罗斯特语录(罗伯特·弗罗斯特)标题:罗伯特·弗罗斯特:诗意人生的指南导语:罗伯特·弗罗斯特(Robert Frost)是美国著名的诗人和散文家,他的作品以深邃的哲理和对自然的热爱而著称。

本文将通过罗伯特·弗罗斯特的语录,探讨他对于人生和自然的独特见解,并探索如何将这些智慧应用于我们的日常生活中。

段落一:自然的启示罗伯特·弗罗斯特曾说过:“自然是人类最好的老师。

”他对自然的热爱和敬畏贯穿了他的作品。

他通过观察自然界中的变化和循环,发现了许多关于生活的启示。

我们可以从他的作品中学到,无论是在繁忙的城市还是在宁静的乡村,我们都可以从自然中汲取灵感和智慧。

段落二:人生的选择弗罗斯特的诗歌中经常涉及人生的选择和困境。

他说:“两条路分叉在树林中,而我选择了人迹罕至的一条。

”这句话表达了他对于决策和选择的思考。

他认为每个人都面临着选择,而选择所带来的结果将决定我们的人生道路。

他鼓励人们勇敢地面对选择,并相信自己的决策。

段落三:逆境中的坚持弗罗斯特的作品中充满了对逆境和挑战的探索。

他说:“道路并不总是平坦的,但是我们必须坚持走下去。

”这句话表达了他对于坚持和勇气的理解。

他认为人生中的挫折和困难是不可避免的,但只有坚持和勇敢面对,我们才能超越自己,实现自己的梦想。

段落四:人与自然的关系弗罗斯特的作品中强调了人与自然之间的紧密联系。

他说:“我们是自然的一部分,而不是它的主宰。

”他认为人类应该尊重自然,与之和谐相处。

他的作品中充满了对自然美的赞美和对人类与自然共生的思考。

他鼓励人们保护环境,珍惜自然资源。

结语:罗伯特·弗罗斯特的语录不仅仅是一些美丽的诗句,更是对于人生和自然的深刻思考。

通过他的作品,我们可以学习到如何与自然和谐相处,如何勇敢地面对人生的选择和挑战,以及如何坚持自己的信念。

让我们从弗罗斯特的智慧中汲取灵感,将诗意融入我们的生活,创造出美丽而有意义的人生旅程。

_Robert_Frost

•出生于美国旧金山 •被称作“新英格兰诗人” •诗歌受欢迎: 传统诗歌 形式和五音步抑扬格

Robert Frost (1874~1963) A Boy’s Will (1913)

《少年的意志》

North of Boston(1914)

《波士顿以北》

Mountain Interval(1916)

• 新绿谓为金, 彩翠最难擒。 初叶是朵花; 花期须臾尽。 转瞬新成旧, 伊甸陷悲愁, 晨曦沦为昼, 金华不久留。

“I took the one the less traveled by, And that has made all the difference.”

Thank

You !

• 1947 Steeple Bush 《绒毛绣线菊》 • 1962 In the Clearing 《林间空地》

•awarded 4 Pulitzer Prizes(普利 策奖 ): 《新罕不什尔》 • 《诗集》 《又一片牧场》 •《标记树》 •received honorary degrees from 44 colleges •poet Laureate •read poetry at a presidential inauguration.

《山间》

West-Running Brook(1928)

《西去的溪流》

Other works

• • • • • • 1923 1930 1936 1942 1945 1947 New Hampshine 《新罕布什尔》 Collected Poems 《诗集》 A Further Range 《又一片牧场》 A Witness Tree 《见证树》 A Masque of Reason《理智的假面具》 A Masque of Mercy《慈悲的假面具》

弗罗斯特——精选推荐

弗罗斯特弗罗斯特弗罗斯特弗罗斯特(弗罗斯特)罗伯特·弗罗斯特(Robert ·Frost )(1874—1963),美国农民诗⼈。

⽣于加利福尼亚州。

弗罗斯特常被称为“交替性的诗⼈”,意指他处在传统诗歌和现代派诗歌交替的⼀个时期。

他⼜被认为与艾略特同为美国现代诗歌的两⼤中⼼。

⽬录个⼈履历成就及荣誉个⼈作品作品欣赏收缩展开个⼈履历成就及荣誉弗罗斯特常被称为“交替性的诗⼈”,意指他处在传统诗歌和现代派诗歌交替的⼀个时期。

他⼜被认为与艾略特同为美国现代诗歌的两⼤中⼼。

个⼈作品弗罗斯特出版过⼗多部诗集其中包括他的成名作《波⼠顿以北》集,另外还有《孩⼦的意愿》、《⼭罅》、《新罕布什尔》、《西流的⼩溪》、《见证之树》、《理智的假⾯具》、《慈悲的假⾯具》、《在林间空地》、《未选择的路》等诗集。

他的诗歌独具风格,以⼝语作诗,⽣动朴实地描写了⽥园风光和农村⽇常⽣活。

他的诗充满了美国的乡⼟⽓息,流传⼴泛,深为⼈们喜爱。

作品欣赏⽕与冰(余光中译)有⼈说世界将毁灭于⽕,有⼈说毁灭于冰。

根据我对于欲望的体验,我同意毁灭于⽕的观点。

但如果它必须毁灭两次,则我想我对于恨有⾜够的认识。

可以说在破坏⼀⽅⾯,冰,也同样伟⼤,且能够胜任。

雪夜我想我依然能认得这⽚林⼦的主⼈,他的屋⼦在⼀个村庄⾥隐藏得那么深,他⼀定想不到我此刻在此驻⾜,看着他的这⽚林⼦披上雪⾐⼀⾝。

我们在这荒凉的地⽅停留,我的马⼉对此疑惑不休,在这林⼦和那湖⾯之间,这⼀年⾥最阴沉得暮霭渐渐浓稠。

它轻轻晃了晃脖⼦上的铃铛,问我到底出了什么情况,除此之外的所有声响,都来⾃风在⽿畔的轻柔和雪在湖⾯的漫扬。

这⽚林⼦如此迷⼈、幽暗⽽深远,⽽我也还有我必须履⾏的诺⾔,⼊睡前,还要⾛好远;还要⾛好远,在我⼊睡之前。

柴垛(徐淳刚译)阴天,我⾛在冰冻的沼泽中停下脚步,⼼想:打这⼉往回⾛吧;不,我要再⾛远点⼉,这样就看到了。

⼤雪把我困住,就⼀只脚不时还能挪动。

那些细⾼细⾼的树将视野全划成了直上直下的线条以致没有什么能标明我是在哪⼉说不准究竟我是在这⼉还是在别处:反正离家很远就是了。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

他的简介; Robert FrostRobert Frost was born in San Francisco on March 26, 1874. He moved to New England at the age of eleven and became interested in reading and writing poetry during his high school years in Lawrence, Massachusetts. He was enrolled at Dartmouth College in 1892, and later at Harvard, though he never earned a formal degree.Frost drifted through a string of occupations after leaving school, working as a teacher, cobbler, and editor of the Lawrence Sentinel. His first professional poem, "My Butterfly," was published on November 8, 1894, in the New York newspaper The Independent.In 1895, Frost married Elinor Miriam White, who became a major inspiration in his poetry until her death in 1938. The couple moved to England in 1912, after their New Hampshire farm failed, and it was abroad that Frost met and was influenced by such contemporary British poets as Edward Thomas, Rupert Brooke, and Robert Graves. While in England, Frost also established a friendship with the poet Ezra Pound, who helped to promote and publish his work.By the time Frost returned to the United States in 1915, he had published two full-length collections, A Boy's Will and North of Boston, and his reputation was established. By the nineteen-twenties, he was the most celebrated poet in America, and with each new book—including New Hampshire (1923), A Further Range (1936), Steeple Bush (1947), and In the Clearing (1962)—his fame and honors (including four Pulitzer Prizes) increased.Though his work is principally associated with the life and landscape of New England, and though he was a poet of traditional verse forms and metrics who remained steadfastly aloof from the poetic movements and fashions of his time, Frost is anything but a merely regional or minor poet. The author of searching and often dark meditations on universal themes, he is a quintessentially modern poet in his adherence to language as it is actually spoken, in the psychological complexity of his portraits, and in the degree to which his work is infused with layers of ambiguity and irony.In a 1970 review of The Poetry of Robert Frost, the poet Daniel Hoffman describes Frost's early work as "the Puritan ethic turned astonishingly lyrical and enabled to say out loud the sources of its own delight in the world," and comments on Frost's career as The American Bard: "He became a national celebrity, our nearly official Poet Laureate, and a great performer in the tradition of that earlier master of the literary vernacular, Mark Twain."About Frost, President John F. Kennedy said, "He has bequeathed his nation a body of imperishable verse from which Americans will forever gain joy and understanding."Robert Frost lived and taught for many years in Massachusetts and Vermont, and died in Boston on January 29, 1963.A Selected BibliographyPoetryA Boy's Will (1913)North of Boston (1914)Mountain Interval (1916)New Hampshire (1923)West-Running Brook (1928)The Lovely Shall Be Choosers (1929)The Lone Striker (1933)From Snow to Snow (1936)A Further Range (1936)A Witness Tree (1942)Come In, and Other Poems (1943)Masque of Reason (1945)Steeple Bush (1947)Hard Not to be King (1951)Robert FrostRobert Frost1874–1963Robert Frost holds a unique and almost isolated position in American letters. "Though his careerfully spans the modern period and though it is impossible to speak of him as anything other than a modern poet," writes James M. Cox, "it is difficult to place him in the main tradition of modern poetry." In a sense, Frost stands at the crossroads of nineteenth-century American poetry and modernism, for in his verse may be found the culmination of many nineteenth-century tendencies and traditions as well as parallels to the works of his twentieth-century contemporaries. Taking his symbols from the public domain, Frost developed, as many critics note, an original, modern idiom and a sense of directness and economy that reflect the imagism of Ezra Pound and Amy Lowell. On the other hand, as Leonard Unger and William Van O'Connor point out in Poems for Study, "Frost's poetry, unlike that of such contemporaries as Eliot, Stevens, and the later Yeats, shows no marked departure from the poetic practices of the nineteenth century." Although he avoids traditional verse forms and only uses rhyme erratically, Frost is not an innovator and his technique is never experimental.Frost's theory of poetic composition ties him to both centuries. Like the nineteenth-century Romantics, he maintained that a poem is "never a put-up job.... It begins as a lump in the throat, a sense of wrong, a homesickness, a loneliness. It is never a thought to begin with. It is at its best when it is a tantalizing vagueness." Yet, "working out his own version of the 'impersonal' view of art," as Hyatt H. Waggoner observed, Frost also upheld T. S. Eliot's idea that the man who suffers and the artist who creates are totally separate. In a 1932 letter to Sydney Cox, Frost explained his conception of poetry: "The objective idea is all I ever cared about. Most of my ideas occur in verse.... To be too subjective with what an artist has managed to make objective is to come on him presumptuously and render ungraceful what he in pain of his life had faith he had made graceful."To accomplish such objectivity and grace, Frost took up nineteenth-century tools and made them new. Lawrence Thompson has explained that, according to Frost, "the self-imposed restrictions of meter in form and of coherence in content" work to a poet's advantage; they liberate him from the experimentalist's burden—the perpetual search for new forms and alternative structures. Thus Frost, as he himself put it in "The Constant Symbol," wrote his verse regular; he never completely abandoned conventional metrical forms for free verse, as so many of his contemporaries were doing. At the same time, his adherence to meter, line length, and rhyme scheme was not an arbitrary choice. He maintained that "the freshness of a poem belongs absolutely to its not having been thought out and then set to verse as the verse in turn might be set to music." He believed, rather, that the poem's particular mood dictated or determined the poet's "first commitment to metre and length of line."Critics frequently point out that Frost complicated his problem and enriched his style by setting traditional meters against the natural rhythms of speech. Drawing his language primarily from the vernacular, he avoided artificial poetic diction by employing the accent of a soft-spoken New Englander. In The Function of Criticism, Yvor Winters faulted Frost for his "endeavor to make his style approximate as closely as possible the style of conversation." But what Frost achieved in his poetry was much more complex than a mere imitation of the New England farmer idiom. He wanted to restore to literature the "sentence sounds that underlie the words," the "vocal gesture" that enhances meaning. That is, he felt the poet's ear must be sensitive to the voice in order to capture with the written word the significance of sound in the spoken word. "The Death of theHired Man," for instance, consists almost entirely of dialogue between Mary and Warren, her farmer-husband, but critics have observed that in this poem Frost takes the prosaic patterns of their speech and makes them lyrical. To Ezra Pound "The Death of the Hired Man" represented Frost at his best—when he "dared to write ... in the natural speech of New England; in natural spoken speech, which is very different from the 'natural' speech of the newspapers, and of many professors."Frost's use of New England dialect is only one aspect of his often discussed regionalism. Within New England, his particular focus was on New Hampshire, which he called "one of the two best states in the Union," the other being Vermont. In an essay entitled "Robert Frost and New England: A Revaluation," W. G. O'Donnell noted how from the start, in A Boy's Will, "Frost had already decided to give his writing a local habitation and a New England name, to root his art in the soil that he had worked with his own hands." Reviewing North of Boston in the New Republic, Amy Lowell wrote, "Not only is his work New England in subject, it is so in technique.... Mr. Frost has reproduced both people and scenery with a vividness which is extraordinary." Many other critics have lauded Frost's ability to realistically evoke the New England landscape; they point out that one can visualize an orchard in "After Apple-Picking" or imagine spring in a farmyard in "Two Tramps in Mud Time." In this "ability to portray the local truth in nature," O'Donnell claims, Frost has no peer. The same ability prompted Pound to declare, "I know more of farm life than I did before I had read his poems. That means I know more of 'Life.'"Frost's regionalism, critics remark, is in his realism, not in politics; he creates no picture of regional unity or sense of community. In The Continuity of American Poetry, Roy Harvey Pearce describes Frost's protagonists as individuals who are constantly forced to confront their individualism as such and to reject the modern world in order to retain their identity. Frost's use of nature is not only similar but closely tied to this regionalism. He stays as clear of religion and mysticism as he does of politics. What he finds in nature is sensuous pleasure; he is also sensitive to the earth's fertility and to man's relationship to the soil. To critic M. L. Rosenthal, Frost's pastoral quality, his "lyrical and realistic repossession of the rural and 'natural,'" is the staple of his reputation.Yet, just as Frost is aware of the distances between one man and another, so he is also always aware of the distinction, the ultimate separateness, of nature and man. Marion Montgomery has explained, "His attitude toward nature is one of armed and amicable truce and mutual respect interspersed with crossings of the boundaries" between individual man and natural forces. Below the surface of Frost's poems are dreadful implications, what Rosenthal calls his "shocked sense of the helpless cruelty of things." This natural cruelty is at work in "Design" and in "Once by the Pacific." The ominous tone of these two poems prompted Rosenthal's further comment: "At his most powerful Frost is as staggered by 'the horror' as Eliot and approaches the hysterical edge of sensibility in a comparable way.... His is still the modern mind in search of its own meaning."The austere and tragic view of life that emerges in so many of Frost's poems is modulated by his metaphysical use of detail. As Frost portrays him, man might be alone in an ultimately indifferent universe, but he may nevertheless look to the natural world for metaphors of his own condition.Thus, in his search for meaning in the modern world, Frost focuses on those moments when the seen and the unseen, the tangible and the spiritual intersect. John T. Napier calls this Frost's ability "to find the ordinary a matrix for the extraordinary." In this respect, he is often compared with Emily Dickinson and Ralph Waldo Emerson, in whose poetry, too, a simple fact, object, person, or event will be transfigured and take on greater mystery or significance. The poem "Birches" is an example: it contains the image of slender trees bent to the ground- temporarily by a boy's swinging on them or permanently by an ice-storm. But as the poem unfolds, it becomes clear that the speaker is concerned not only with child's play and natural phenomena, but also with the point at which physical and spiritual reality merge.Such symbolic import of mundane facts informs many of Frost's poems, and in "Education by Poetry" he explained: "Poetry begins in trivial metaphors, pretty metaphors, 'grace' metaphors, and goes on to the profoundest thinking that we have. Poetry provides the one permissible way of saying one thing and meaning another.... Unless you are at home in the metaphor, unless you have had your proper poetical education in the metaphor, you are not safe anywhere."Frost's own poetical education began in San Francisco where he was born in 1874, but he found his place of safety in New England when his family moved to Lawrence, Massachusetts, in 1884 following his father's death. The move was actually a return, for Frost's ancestors were originally New Englanders. The region must have been particularly conducive to the writing of poetry because within the next five years Frost had made up his mind to be a poet. In fact, he graduated from Lawrence High School, in 1892, as class poet (he also shared the honor of co-valedictorian with his wife-to-be Elinor White); and two years later, the New York Independent accepted his poem entitled "My Butterfly," launching his status as a professional poet with a check for $15.00.To celebrate his first publication, Frost had a book of six poems privately printed; two copies of Twilight were made—one for himself and one for his fiancee. Over the next eight years, however, he succeeded in having only thirteen more poems published. During this time, Frost sporadically attended Dartmouth and Harvard and earned a living teaching school and, later, working a farm in Derry, New Hampshire. But in 1912, discouraged by American magazines' constant rejection of his work, he took his family to England, where he could "write and be poor without further scandal in the family." In England, Frost found the professional esteem denied him in his native country. Continuing to write about New England, he had two books published, A Boy's Will and North of Boston, which established his reputation so that his return to the United States in 1915 was as a celebrated literary figure. Holt put out an American edition of North of Boston, and periodicals that had once scorned his work now sought it.Since 1915 Frost's position in American letters has been firmly rooted; in the years before his death he came to be considered the unofficial poet laureate of the United States. On his seventy-fifth birthday, the U.S. Senate passed a resolution in his honor which said, "His poems have helped to guide American thought and humor and wisdom, setting forth to our minds a reliable representation of ourselves and of all men." In 1955, the State of Vermont named a mountain after him in Ripton, the town of his legal residence; and at the presidential inauguration of John F. Kennedy in 1961, Frost was given the unprecedented honor of being asked to read apoem. Frost wrote a poem called "Dedication" for the occasion, but could not read it given the day's harsh sunlight. He instead recited "The Gift Outright," which Kennedy had originally asked him to read, with a revised, more forward-looking, last line.Though Frost allied himself with no literary school or movement, the imagists helped at the start to promote his American reputation. Poetry: A Magazine of Verse published his work before others began to clamor for it. It also published a review by Ezra Pound of the British edition of A Boy's Will, which Pound said "has the tang of the New Hampshire woods, and it has just this utter sincerity. It is not post-Miltonic or post-Swinburnian or post Kiplonian. This man has the good sense to speak naturally and to paint the thing, the thing as he sees it." Amy Lowell reviewed North of Boston in the New Republic, and she, too, sang Frost's praises: "He writes in classic metres in a way to set the teeth of all the poets of the older schools on edge; and he writes in classic metres, and uses inversions and cliches whenever he pleases, those devices so abhorred by the newest generation. He goes his own way, regardless of anyone else's rules, and the result is a book of unusual power and sincerity." In these first two volumes, Frost introduced not only his affection for New England themes and his unique blend of traditional meters and colloquialism, but also his use of dramatic monologues and dialogues. "Mending Wall," the leading poem in North of Boston, describes the friendly argument between the speaker and his neighbor as they walk along their common wall replacing fallen stones; their differing attitudes toward "boundaries" offer symbolic significance typical of the poems in these early collections.Mountain Interval marked Frost's turn to another kind of poem, a brief meditation sparked by an object, person or event. Like the monologues and dialogues, these short pieces have a dramatic quality. "Birches," discussed above, is an example, as is "The Road Not Taken," in which a fork in a woodland path transcends the specific. The distinction of this volume, the Boston Transcript said, "is that Mr. Frost takes the lyricism of A Boy's Will and plays a deeper music and gives a more intricate variety of experience."Several new qualities emerged in Frost's work with the appearance of New Hampshire, particularly a new self-consciousness and willingness to speak of himself and his art. The volume, for which Frost won his first Pulitzer Prize, "pretends to be nothing but a long poem with notes and grace notes," as Louis Untermeyer described it. The title poem, approximately fourteen pages long, is a "rambling tribute" to Frost's favorite state and "is starred and dotted with scientific numerals in the manner of the most profound treatise." Thus, a footnote at the end of a line of poetry will refer the reader to another poem seemingly inserted to merely reinforce the text of "New Hampshire." Some of these poems are in the form of epigrams, which appear for the first time in Frost's work. "Fire and Ice," for example, one of the better known epigrams, speculates on the means by which the world will end. Frost's most famous and, according to J. McBride Dabbs, most perfect lyric, "Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening," is also included in this collection; conveying "the insistent whisper of death at the heart of life," the poem portrays a speaker who stops his sleigh in the midst of a snowy woods only to be called from the inviting gloom by the recollection of practical duties. Frost himself said of this poem that it is the kind he'd like to print on one page followed with "forty pages of footnotes."West-Running Brook, Frost's fifth book of poems, is divided into six sections, one of which is taken up entirely by the title poem. This poem refers to a brook which perversely flows west instead of east to the Atlantic like all other brooks. A comparison is set up between the brook and the poem's speaker who trusts himself to go by "contraries"; further rebellious elements exemplified by the brook give expression to an eccentric individualism, Frost's stoic theme of resistance and self-realization. Reviewing the collection in the New York Herald Tribune, Babette Deutsch wrote: "The courage that is bred by a dark sense of Fate, the tenderness that broods over mankind in all its blindness and absurdity, the vision that comes to rest as fully on kitchen smoke and lapsing snow as on mountains and stars—these are his, and in his seemingly casual poetry, he quietly makes them ours."A Further Range, which earned Frost another Pulitzer Prize and was a Book-of-the-Month Club selection, contains two groups of poems subtitled "Taken Doubly" and "Taken Singly." In the first, and more interesting, of these groups, the poems are somewhat didactic, though there are humorous and satiric pieces as well. Included here is "Two Tramps in Mud Time," which opens with the story of two itinerant lumbermen who offer to cut the speaker's wood for pay; the poem then develops into a sermon on the relationship between work and play, vocation and avocation, preaching the necessity to unite them. Of the entire volume, William Rose Benet wrote, "It is better worth reading than nine-tenths of the books that will come your way this year. In a time when all kinds of insanity are assailing the nations it is good to listen to this quiet humor, even about a hen, a hornet, or Square Matthew.... And if anybody should ask me why I still believe in my land, I have only to put this book in his hand and answer, 'Well-here is a man of my country.'"Most critics acknowledge that Frost's poetry in the forties and fifties grew more and more abstract, cryptic, and even sententious, so it is generally on the basis of his earlier work that he is judged. His political conservatism and religious faith, hitherto informed by skepticism and local color, became more and more the guiding principles of his work. He had been, as Randall Jarrell points out, "a very odd and very radical radical when young" yet became "sometimes callously and unimaginatively conservative" in his old age. He had become a public figure, and in the years before his death, much of his poetry was written from this stance.Reviewing A Witness Tree in Books, Wilbert Snow noted a few poems "which have a right to stand with the best things he has written": "Come In," "The Silken Tent," and "Carpe Diem" especially. Yet Snow went on: "Some of the poems here are little more than rhymed fancies; others lack the bullet-like unity of structure to be found in North of Boston." On the other hand, Stephen Vincent Benet felt that Frost had "never written any better poems than some of those in this book." Similarly, critics were let down by In the Clearing. One wrote, "Although this reviewer considers Robert Frost to be the foremost contemporary U.S. poet, he regretfully must state that most of the poems in this new volume are disappointing.... [They] often are closer to jingles than to the memorable poetry we associate with his name." Another maintained that "the bulk of the book consists of poems of 'philosophic talk.' Whether you like them or not depends mostly on whether you share the 'philosophy.'"Indeed, many readers do share Frost's philosophy, and still others who do not neverthelesscontinue to find delight and significance in his large body of poetry. In October, 1963, President John F. Kennedy delivered a speech at the dedication of the Robert Frost Library in Amherst, Massachusetts. "In honoring Robert Frost," the President said, "we therefore can pay honor to the deepest source of our national strength. That strength takes many forms and the most obvious forms are not always the most significant.... Our national strength matters; but the spirit which informs and controls our strength matters just as much. This was the special significance of Robert Frost." The poet would probably have been pleased by such recognition, for he had said once, in an interview with Harvey Breit: "One thing I care about, and wish young people could care about, is taking poetry as the first form of understanding. If poetry isn't understanding all, the whole world, then it isn't worth anything."Frost's poetry is revered to this day. When a previously unknown poem by Frost titled "War Thoughts at Home," was discovered and dated to 1918, it was subsequently published in the fall, 2006, edition of the Virginia Quartely Review.CareerPoet. Held various jobs between college studies, including bobbin boy in a Massachusetts mill, cobbler, editor of a country newspaper, schoolteacher, and farmer. Lived in England, 1912-15. Tufts College, Medford, MA, Phi Beta Kappa poet, 1915 and 1940; Amherst College, Amherst, MA, professor of English and poet-in-residence, 1916-20, 1923-25, and 1926-28; Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, Phi Beta Kappa poet, 1916 and 1941; Middlebury College, Middlebury, VT, co-founder of the Bread-Loaf School and Conference of English, 1920, annual lecturer, beginning 1920; University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, professor and poet-in-residence, 1921-23, fellow in letters, 1925-26; Columbia University, New York City, Phi Beta Kappa poet, 1932; Yale University, New Haven, CT, associate fellow, beginning 1933; Harvard University, Charles Eliot Norton Professor of Poetry, 1936, board overseer, 1938-39, Ralph Waldo Emerson Fellow, 1939-41, honorary fellow, 1942-43; associate of Adams House; fellow in American civilization, 1941-42; Dartmouth College, Hanover, NH, George Ticknor Fellow in Humanities, 1943-49, visiting lecturer.BibliographyPOETRYTwilight, [Lawrence, MA], 1894, reprinted, University of Virginia, 1966.A Boy's Will, D. Nutt, 1913, Holt, 1915.North of Boston, D. Nutt, 1914, Holt, 1915, reprinted, Dodd, 1977.Mountain Interval, Holt, 1916.New Hampshire, Holt, 1923, reprinted, New Dresden Press, 1955.Selected Poems, Holt, 1923.Several Short Poems, Holt, 1924.West-Running Brook, Holt, 1928.Selected Poems, Holt, 1928.The Lovely Shall Be Choosers, Random House, 1929.The Lone Striker, Knopf, 1933.Two Tramps in Mud-Time, Holt, 1934.The Gold Hesperidee, Bibliophile Press, 1935.Three Poems, Baker Library Press, 1935.A Further Range, Holt, 1936.From Snow to Snow, Holt, 1936.A Witness Tree, Holt, 1942.A Masque of Reason (verse drama), Holt, 1942.Steeple Bush, Holt, 1947.A Masque of Mercy (verse drama), Holt, 1947.Greece, Black Rose Press, 1948.Hard Not to Be King, House of Books, 1951.Aforesaid, Holt, 1954.The Gift Outright, Holt, 1961."Dedication" and "The Gift Outright" (poems read at the presidential inaugural, 1961; published with the inaugural address of J. F. Kennedy), Spiral Press, 1961.In the Clearing, Holt, 1962.Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening, Dutton, 1978.Early Poems, Crown, 1981.A Swinger of Birches: Poems of Robert Frost for Young People (with audiocassette), Stemmer House, 1982.Spring Pools, Lime Rock Press, 1983.Birches, illustrated by Ed Young, Holt, 1988.The Runaway (juvenile poetry), illustrated by Glenna Lang, Godine (Boston, MA), 1996.Also author of And All We Call American, 1958.POEMS ISSUED AS CHRISTMAS GREETINGSChristmas Trees, Spiral Press, 1929.Neither Out Far Nor In Deep, Holt, 1935.Everybody's Sanity, [Los Angeles], 1936.To a Young Wretch, Spiral Press, 1937.Triple Plate, Spiral Press, 1939.Our Hold on the Planet, Holt, 1940.An Unstamped Letter in Our Rural Letter Box, Spiral Press, 1944.On Making Certain Anything Has Happened, Spiral Press, 1945.One Step Backward Taken, Spiral Press, 1947.Closed for Good, Spiral Press, 1948.On a Tree Fallen Across the Road to Hear Us Talk, Spiral Press, 1949.Doom to Bloom, Holt, 1950.A Cabin in the Clearing, Spiral Press, 1951.Does No One but Me at All Ever Feel This Way in the Least, Spiral Press, 1952.One More Brevity, Holt, 1953.From a Milkweed Pod, Holt, 1954.Some Science Fiction, Spiral Press, 1955.Kitty Hawk, 1894, Holt, 1956.My Objection to Being Stepped On, Holt, 1957.Away, Spiral Press, 1958.A-Wishing Well, Spiral Press, 1959.。