新编跨文化交际英语教程复习资料(1)

新编跨文化交际期末复习资料

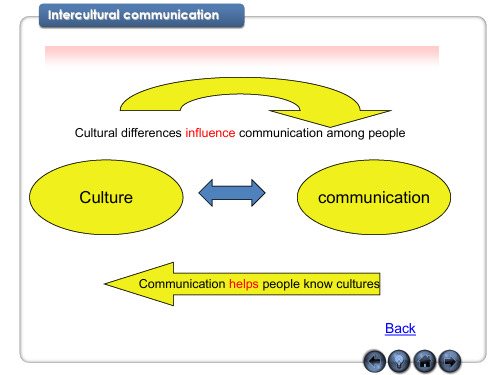

1.Iceberg:{Edward. 7. Hall.--<The silence of language>标志着“跨文化交流”学科的开始} Culture can be viewed as an iceberg. Nine-tenths of an iceberg is out of sight (below the water line). Likewise, nine-tenths of culture is outside of conscious awareness. The part of the cultural iceberg that above the water is easy to be noticed. The out-of-awareness part is sometimes called “deep culture”. This part of the cultural iceberg is hidden below the water and is thus below the level of consciousness. People learn this part of culture through imitating models. / Above the water: what to eat, how to dress, how to keep healthy;Below the water: belief, values, worldview and lifeview, moral emotion, attitude personalty2.Stereotype:定型主义 a stereotype is a fixed notion about persons in a certain category, with no distinctions made among individuals. In other words, it is an overgeneralized and oversimplified belief we use to categorize a group of people.3.Ethnocentrism: 民族中心主义Ethnocentrism is the technical name for the view of things in which one’s own group is the center of everything, and all others are scaled and rated with reference to it. It refers to our tendency to identify with our in-group and to evaluate out-groups and their members according to its standard.4.Culture:Culture can be defined as the coherent, learned, shared view of group of people about life’s concerns that ranks what is important, furnishes attitudes about what things are appropriate, and dictates behavior.5.Cultural values: Values inform a member of a culture about what is good and bad, right and wrong, true and false, positive and negative, and the like. Cultural values defines what is worth dying for, what is worth protecting, what frightens people, what are proper subjects for study and for ridicule, and what types of events lead individuals to group solidarity.6.Worldview: A worldview is a culture’s orientation toward such things as God, nature, life, death, the universe, and other philosophical issues that are concerned with the meaning of life and with “being”.7.Social Organizations: The manner in which a culture organizes itself is directly related to the institution within that culture. The families who raise you and the goverments with which you associate and hold allegiance to all help determine hoe you perceive the world and how you behave within that world.8.Globalization: refers to the establishment of a world economy, in which national borders are becoming less and less important as transnational corporations, existing everywhere and nowhere, do business in a global market.munication: Communication is any behavior that is perceived by others. So it can be verbal and nonverbal, informative or persuasive, frightening or amusing, clear or unclear, purposeful or accidental, communication is our link to the rest of the humanity. It pervades everything we do.10.Elements of communication process:交流过程的基本原理(1).context: The interrelated conditions of communication make up what is known as context.(2).The participants: in communication play the roles of sender and receiver, sometimes—as in face-to-face communication—of the messages simultaneously.(3). messages: are far more complex. They include the elements of meanings, symbols, encoding and decoding.(4). A channels: is both the route traveled by the messages and the means of transportation. We may use sound, sight, smell, taste, touch, or any combination of these to carry a message.(5). noise: is any stimulus, external or internal to the participants, that interferes with the sharing of meaning. External noise: sight, sound…Internal noise: thoughts, feeling…Semantic noise: unintended meaning aroused by certain verbal symbols can inhibit the accuracy of decoding.(6).Feedback: As receivers attempt to decode the meaning of messages, they are likely to give some kind of verbal or nonverbal response. This response, called feedback, tells the sender whether the massage has been heard, seen, or understood.11.Abraham Mslow (亚伯拉罕•马斯洛) –five basic needs五个需求1. physiological needs—food, water, air, rest, clothing, shelter, and all necessary to sustain life2. safety needs—physically safe, psychologically secure3. belongingness needs—accepted by other people and needs to belong to a group or groups.4. esteem needs—recognition, respect, reputation5. self-actualization needs-the highest need of a person12.Culture Dimensions 文化维度13.A High-context: 内向型communication or message is one in which most of the information is either in the context or internalized in the person, while very little is in the context or internalized in the person, while very little is in the coded, explicit, transmitted part of the message. Eg. Japanese, Chinese, Korean, African American, Native American. self-effacement隐匿自我A Low-context:外向型communication is just the opposite, the mass of the information is vested in the explicit code, and the context or situation plays a minimal role. Eg. German-Swiss, German, Scandinavian, American, French, English self-enhancement凸显自我Low-context interaction emphasizes direct talk, person-oriented focus, self-enhancement mode, and the importance of “talk”. High-context interaction, in comparison, stresses indirect talk, status-oriented focus, self-effacement mode, and the importance of nonverbal signals and even silence.Eg: In Scene 1 and spell out everything that is on their minds with no restraints. Their interactionexchange is direct,to the point, bluntly contentious, and full of face-threat verbal message. Scene 1 represents one possible low-context way of approaching interpersonal conflict.In Scene 2, has not directly expressed her concern over the piano noise with because she wants to preserve face and her relationship with . Rather, only uses indirect hints and nonverbal signals to get her point across. However, correctly “reads between the lines” of verbal message and apologizes appropriately and effectively before a real conflict can bubble to surface. Scene 2 represents one possible high-context way of approaching interpersonal conflict.Direct and Indirect Verbal Interaction Styles self-enhancement and self-effacement凸显自我,隐匿自我In the direct verbal style, statements clearly reveal the speaker’s intentions and are enunciated in a forthright tone of voice. In the indi rect verbal style, verbal statements tend to camouflage the speaker’s actual intentions and are carried out with more nuanced tone of voice.14.Colors: Black: death, evil, mourning, sexy; Blue-cold, sad, sky, masculine; Green-envy, greed, money; Pink: feminine, shy, softness, sweet; Red: anger, hot, love, sex; White: good, innocent, peaceful, pure; Yellow: caution, happy, sunshine, warm15.Functions of Nonverbal Communication: repeating, complementing, substituting, regulating contradicting16.Confucian teaching key principles: 1.Social order and stability are based on unequal relationships between people. 2. The family is the prototype for all social relationships. 3. Proper social behavior consist of not treating others as you would not like to be treated yourself. 4. People should be skilled , educated, hardworking, thrifty, modest, patient, and persevering.Four books and five classical: The Analects of Confucian <论语>, Mencius <孟子>,Great Learning <大学>,The Doctrines of Mean <中庸> / Classic of poetry <诗经>,Book of documents <尚书>, Book of kites <礼记>, Classic of changes <周易>, Spring and Autumn Annals <春秋>. 仁义礼智信:merciful, justified, polite, intelligent, honest17.The Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis: language becomes our shaper of ideas rather than simple our tool for reporting ideas, language influenced or even determined the ways in which people thought. The central idea of the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis is that language functions, not simply as a device for reporting experience, but also, and more significantly, as a way of defining experience for its speakerInfluence: The Sapir-Whorf hypothesis has alerted people to the fact language is keyed to the total culture, and that it reve als a people’s view of its total environment. Language directs the perceptions of its speakers to certain things; it gives them ways to analyze and to categorize experience. Such perceptions are unconscious and outside the control of the speaker. The ultimate value of the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis is that it offers hints to cultural differences and similarities among people.18.The way people speakHigh involvement高度卷入: 1. talk more 2. interrupt more 3. expect to be interrupted 4. talk more loudly at times 5. talk more quickly. Eg. Russian, Italian, Greek, Spanish, South American, Arab, AfricanHigh considerateness高度体谅: 1, speak one at a time 2. use polite listening sounds, 3. refrain from interrupting, 4. give plenty of positive and respectful responses to their conversation partners. Eg. Mainstream American19.文化维度Orientation—Kluckhohns and Strodtbeck Beliefs and Behaviors20.Chinese VS English-----Chinese: open, visual, old. English: close, changing, modern21.Stumbling Blocks in Intercultural Communication跨文化交际中的绊脚石(1) Assumption of similarities假定相似(2) Language differences (3) Nonverbal misinterpretations不用言语表达的误解(4) Preconception先入为主的概念的固定形式(5) Tendency to evaluate评价意图(6) High anxiety焦虑(7) Conclusion22. Essentials of Human Communication(1) Communication is a dynamic process. (2) Communication is symbolic. (3) Communication is systemic.(4) Communication involves making inferences. (5) Communication has a consequence23. How is language related to cultureCulture and language are intertwined and shape each other. In our own environment we aware of the implications of these choices. All languages have social questions and information questions. The point is that words in themselves do not carry the meaning. The meaning comes out of the context the cultural usage. In addition to the environment, language reflects cultural values.24.More words/expression→important role in cultureIn Chinese we have many kinship terms, some of which seem to have no equivalents in English. Compared with Chinese, English has fewer kinship terms. The difference is not just linguistic; it is infundamentally cultural.25.A culture’s conception of time can be examined from three different perspectives: 1. informal time;2. perceptions of past, present, and future;3. monochromic and polychromic.26.Monochronic(M-time) 单维时间and polychromic(P-time)多维时间Monochronic people:美国人Do one thing at a time. Concentrate on the job. Take time commitments seriously. Are committed to the job. Adhere to plans. Are concerned about not disturbing others; follow rules of privacy. Show great respect for private property; seldom borrow or lend. Emphasize promptness. Are accustomed to short-term relationships.Polychromic people: 中国人Do many things at once. Are easily distracted and subject to interruptions. Consider time commitments an objective to be achieved, if possible. Are committed to people and human relationships. Change plans often and easily. Are more concerned with people close to them(family, friend, close business associates) than with privacy. Borrow and lend things often and easily. Base promptness on the relationship. Have strong tendency to build lifetime relationships.27.Adapting to a New Cultureculture shock.: Any number of symptoms征兆can occur during cycles of culture shock. These symptoms can be (1)physiological (2)emotionally (3)communicationPredeparture stage:Stage one: everything is beautiful. Stage two: everything is awful. Stage three: everything is OK.Adaptation and reentry再进入Methods: 1. patience. 2. meet new people. 3. try new things. 4. give yourself periods of rest and thought. 5. work on your self-concept. 6. write. 7. observe body language. 8. learn the verbal language.。

跨文化交际复习资料(最新版)

1.monochronic time (M Time) :It schedules one event at a time. In thesecultures time is perceived as a linear structure just like a ribbon stretching fromthe past into the future.2.polychronic time (P Time) :schedules several activities at the same time. Inthese culture people emphasize the involvement of people more than schedules. They do not see appointments as ironclad commitments and oftenbreak them.3.intercultural communication :is a face-to-face communication betweenpeople from different cultural backgrounds4.host culture is the mainstream culture of anyone particular country.5.minority culture is the cultural groups that are smaller in numerical terms inrelation to the host culture.6.subculture is a smaller, possibly nonconformist, subgroup within the hostculture.7.multiculturalism is the official recognition of a country’s cultural and ethnicdiversity.8.cross-cultural communication is a face-to-face communication betweenreprentatives of business,government and professional groups from different cultures.9.high-context culture :a culture in which meaning is not necessarily containedin words. Information is provided through gestures, the use of space, and evensilence.10.low-context culture :a culture in which the majority of the information is vestedin the explicit code.11.perception: in its simplest sense,perception is ,as Marshall singer tells us,”theprocess by which an individual selects, evaluates,and organizes stimuli fromthe external world” In other words, perception is an internal process wherebywe convert the physical energies of the world into meaningful internal experiences.Non-verbal communicationIt refers to communication through a whole variety of different types f signal comeinto play, including the way we more, the gestures we employ, the posture weadopt, the facial expression we wear, the direction of our gaze, to the extent towhich we touch and the distance we stand from each other.. IndividualismIndividualism refers to the doctrine that the interests of the individual are or oughtto be paramount, and that all values, right, and duties originate in individuals. It emphasizes individual initiative, independence,individual expression, and even privacy.13. ParalanguageThe set of nonphonemic properties of speech, such as speaking tempo, vocal pitch, and intonational contours, that can be used to communicate attitudes orother shades of meaning.12.人际交际interpersonal communication: a small number of individuals who are interactingexclusively with one another and who therefore have the ability to adapt their messagesspecifically for those others and to obtain immediate interpretaions from them.指少数人之间的交往他们既能根据对方调整自己的信息,又能立即从对方那里获得解释。

跨文化交际复习资料

跨文化交际复习资料Unit 1&2Reviewing Papers for Intercultural CommunicationUnit 1&2I- Keywords(1)Sender/Source: A sendcr/source is the person who transmits a message.(信息发出者/信息源:信息发岀者/信息源指传递信息的人。

)(2)Message: A message is any signal that triggers the response of a receiver.(信息:信息扌呂弓I 起信息接受者反应的任何信号。

)(3)Encoding: It refers to the activity during which the sender must choose certain words or nonverbal methods to send an intentional message.(编码:编码指信息发岀者选择言语或用非言语的方式发出有目的的信息的行为。

)⑷ Channel/NIedium:It is the method used to deliver a message・(渠道/媒介:渠道/媒介指发送信息的方法。

)(5)Receiver: A receiver is any person who notices and gives some meaning to a message・(信息接受者:信息接受者指信息接收者是指注意到信息并且赋予信息某些含义的人。

)(6)Decoding: It is the activity during which the receiver attaches meaning to the words or symbols iie/she has received.(解码:解码指信息接受者赋予其收到的言语或符号信息意义的行为。

最新新编跨文化交际英语教程单元知识点梳理Unit1-3讲课稿

Unit 1 Communication Across Cultures1.The need for intercultural communication:New technology; Innovative communication system; Globalization of the economy; Changes in immigration patterns 2.Three major socio-cultural elements influence communication are: cultural values; worldview(religion); social organization(family and state).3.Nonverbal behavior: gestures, postures, facial expressions, eye contact and gaze, touch(Chinese people are reluctant to express their disproval openly for fear of making others lose face.)4. Six stumbling blocks in Intercultural communication(1)Assumption of similarities(2)Language differences(3)Nonverbal misinterpretations(4)Preconception and stereotypes先入之见刻板印象(5)Tendency to evaluate(6)High anxietyUnit 2 Culture and Communication1.Characteristics of Culture: Culture is learned; Culture is a setof shared interpretations; Culture involves Beliefs, Values, and Norms(规范,准则); Culture Affects Behaviors; Culture involves Large Groups of people2.Cultural identity文化身份refers to one’s sense of belongingto a particular culture or ethnic group. People consciously identify themselves with a group that has a shared system of symbols and meanings as well as norms for conduct.3.Characteristics of Cultural Identity:Cultural identity iscentral to a person’s sense of self. Cultural identity is dynamic (动态的). Cultural identity is also multifaceted(多方面的)components of one’s self-concept.4.I ntercultural communication defined: Interculturalcommunication refers to communication between people whose cultural perceptions and symbol systems are distinct enough to alter the communication event.5.Elements of communication: Context; Participants; Message;Channels; Noise; FeedbackUnit 3 Cultural Diversity1.Define worldview and religionWorldview: deals with a culture’s most fundamental beliefs about the place in the cosmos(宇宙), beliefs about God, andbeliefs about the nature of humanity and nature.Religion:refers to belief in and reverence for a supernatural power or powers regarded as creator and a governor of the universe.Three major religions :a. Christian Religions Groups (基督教的)b. Islam (伊斯兰教)c. Buddhism (佛教)2.Human nature: (1) is evil but perfectible(2) is a mixture of good and evil(3) good but corruptible(易腐化的)3.Relationship of Man to Nature: (1) subjugation to nature(2) harmony with nature(3) mastery with nature4.Social Relationship:Hierarchy; Group; Individual5.Cultual Dimensions: Hofstede identity 5 dimensionsindividualism vs collectivism; uncertainty avoidance; power distance; masculinity vs femininity; long-term vs short-term orientation6. High-Context and Low-context CulturesA high-context(HC)—high-context cultures(Native Americans, Latin Americans, Japanese, Korean and Chinese): information isoften provided through gesture, the use of the space, and even silence. Meaning is also conveyed through status(age, sex, education, family background, title, and affiliations) and through an individu al’s informal friends and associates.A low-context(LC)—low-context cultures(German, Swiss as well as American) For example, the Asian mode of communication is often indirect and implicit, whereas Western communication tends to be direct and explicit—that is, everything needs to be stated.For example, members of low-context cultures expect messages to be detailed, clear-cut, and definite.The high-context people are apt to become impatient and irritated when low-context people insist on giving them information they don’t need.。

跨文化交际实用教程unit1重点词汇及问题

跨文化交际实用教程unit1重点词汇及问题Unit 1第一单元需要掌握的术语:Global village:All the different parts of the world form one community linked together by electronic communications, especially the Internet.Melting pot:a socio-cultural assimilation of people of different backgrounds and nationalities.Cultural Diversity: refers to the mix of cultures and sub-cultures of a group or organization or region.Intercultural communication: communication between people whose cultural perceptions and symbol systems are distinct enough to alter the communication event. Culture: a learned set of shared interpretations about beliefs, values, and norms, which affect the behavior of a relatively large group of people.Encul turation: all the activities of learning one’s culture are called enculturation. Acculturation: the process which adopts the changes brought about by another culture and develops an increased similarity between the two cultures. Ethnocentrism: the belief that your own cultural background is superior.SourceThe source is the person with an idea he or she desires to communicate.EncodingEncoding is the process of putting an idea into a symbol.MessageThe term message identifies the encoded thought. Encoding is the process, the verb; the message is the resulting object.ChannelThe term channel is used technically to refer to the means by which the encoded message is transmitted. The channel or medium, then, may be print, electronic, or the light and sound waves of the face-to-face communication.NoiseThe term noise technically refers to anything that distorts the message the source encodes.ReceiverThe receiver is the person who attends to the message.DecodingDecoding is the opposite process of encoding and just as much an active process. The receiver is actively involved in the communication process by assigning meaning to the symbols received.Receiver responseReceiver response refers to anything the receiver does after having attended to and decoded the message.(信息接受者在收到并解码/理解信息之后所作出的反应)FeedbackFeedback refers to that portion of the receiver response of which the source has knowledge and to which the source attends and assigns meaning.(信息接受者所作出的反应中能让信息发送者收到并理解的那一部分)ContextGenerally, context can be defined as the environment in which the communication takes place and which helps define the communication.五、简答和案例分析1. What are the four trends that lead to the development of the global village?The four trends that lead to the development of global village are:1) Convenient transportation systems;2) Innovative communication systems;3) Economic globalization;4) Widespread migration(p.8-9)2. What are the three aspects where the cultural differences exist?The three aspects where the cultural differences exist are:1) the material and spiritual products people produce2) what they do 3) what they think3. What are the three ingredients of culture?The three ingredients of culture are:1) artifacts 2) behavior3) concepts (beliefs, values, world views…)4. How to understand cultural iceberg?Just as an iceberg which has a visible section above the waterline and a larger invisible section below the waterline, culture has some aspects that are observable and others that can only be suspected and imagined. Also like an iceberg, the part of culture that is visible is only a small part of a much bigger whole. It is said nine-tenth of culture is below the surface. (pg. 7)5. What are the characteristic of culture?1) Culture is shared,2) Culture is learned,3) Culture is dynamic,4) Culture is ethnocentric.6. What are the characteristic of communication?1) Communication is dynamic2) Communication is irreversible3) Communication is symbolic4) Communication is systematic5) Communication is transactional. (pg. 8)6) Communication is contextual. (pg. 8)7. How is Chinese addressing different from American addressing?1) In China, the use of given names is limited to husband and wife, very close friends, juniors by elders or superiors, while more English-speaking people address others by using the first name, even when people meet for the first time.2) Chinese often extend kinship terms to people not related by blood or marriage. These terms are used after the surname to show politeness and respect. (pg. 23), but The English equivalents of the above kinship terms are not so used.3) In Chinese, people use a person’s title, office, or profession in addressing people. In English, only a few occupations or titles are used .8. How is the Chinese writing style different from the American style?1) Some oriental writing…is marked by what may be called an approach by indirection. In this kind of writing, the development of the paragraph may be said to be ‘turning and turning in a widening gyre.’The circles or gyres turn around the subject and show it from a variety of tangential views, but the subject is never looked at directly. Things are developed in terms of what they are not, rather than in terms of what they are.”2) An English paragraph usually begins with a topic statement, and then, by a series of subdivisions of that topic statement, each supported by example and illustrations,proceeds, to develop that central idea and relate that idea to all other ideas in the whole essay, and to employ that idea in it proper relationship with the other ideas, to prove something, or perhaps to argue something.”9. What are the different features of M-time and P-time?回答时注意:Monochronic 和Polychronic 两项都要列举几条,八条不用都回答上,但是第一条一定要回答上。

(完整版)新编跨文化交际英语教程_参考答案Unit1

Unit 1Communication Across CulturesReading IIntercultural Communication:An IntroductionComprehension questions1. Is it still often the case that “everyone’s quick to blame the alien” in the contemporary world?This is still powerful in today’s social and political rhetoric. For instance, it is not uncommon in today‘s society to hear people say that most, if not all, of the social and economic problems are caused by minorities and immigrants.2. What’s the difference between today’s intercultural co ntact and that of any time in the past?Today‘s intercultural encounters are far more numerous and of greater importance than in any time in history.3. What have made intercultural contact a very common phenomenon in our life today?New technology, in the form of transportation and communication systems, has accelerated intercultural contact; innovative communication systems have encouraged and facilitated cultural interaction; globalization of the economy has brought people together; changes in immigration patterns have also contributed to intercultural encounter.4. How do you understand the sentence “culture is everything and everywhere”? Culture supplies us with the answers to questions about what the world looks like and how we live and communicate within that world. Culture teaches us how to behave in our life from the instant of birth. It is omnipresent.5. What are the major elements that directly influence our perception and communication?The three major socio-cultural elements that directly influence perception and communication are cultural values, worldview (religion), and social organizations (family and state).6. What does one’s family teach him or her while he or she grows up in it?The family teaches the child what the world looks like and his or her place in that world.7. Why is it impossible to separate our use of language from our culture?Because language is not only a form of preserving culture but also a means of sharing culture. Language is an organized, generally agreed-upon, learned symbol system that is used to represent the experiences within a cultural community.8. What are the nonverbal behaviors that people can attach meaning to?People can attach meaning to nonverbal behaviors such as gestures, postures, facial expressions, eye contact and gaze, touch, etc.9. How can a free, culturally diverse society exist?A free, culturally diverse society can exist only if diversity is permitted to flourish without prejudice and discrimination, both of which harm all members of the society. Reading IIThe Challenge of GlobalizationComprehension questions1. Why does the author say that our understanding of the world has changed?Many things, such as political changes and technological advances, have changed the world very rapidly. In the past most human beings were born, lived, and died within a limited geographical area, never encountering people of other cultural backgrounds. Such an existence, however, no longer prevails in the world. Thus, all people are faced with the challenge of understanding this changed and still fast changing world in which we live.2. What a “global village” is like?As our world shrinks and its inhabitants become interdependent, people from remote cultures increasingly come into contact on a daily basis. In a “global village”, members of once isolated groups of people have to communicate with members of other cultural groups. Those people may live thousands of miles away or right next door to each other.3. What is considered as the major driving force of the post-1945 globalization? Technology, particularly telecommunications and computers are considered to be the major driving force.4. What does the author mean by saying that “the ‘global’ may be more local than the ‘local’”?The increasing global mobility of people and the impact of new electronic media on human communications make the world seem smaller. We may communicate more with people of other countries than with our neighbors, and we may be more informed of the international events than of the local events. In this sense, “the ‘global’ may be more local than the ‘local’”.5. Why is it important for businesspeople to know diverse cultures in the world? Effective communication may be the most important competitive advantage that firms have to meet diverse customer needs on a global basis. Succeeding in the global market today requires the ability to communicate sensitively with people from other cultures, a sensitivity that is based on an understanding of cross-cultural differences.6. What are the serious problems that countries throughout the world are confronted with?Countries throughout the world are confronted with serious problems such as volatile international economy, shrinking resources, mounting environmental contamination, and epidemics that know no boundaries.7. What implications can we draw from the case of Michael Fay?This case shows that in a world of international interdependence, the ability tounderstand and communicate effectively with people from other cultures takes on extreme urgency. If we are unaware of the significant role culture plays in communication, we may place the blame for communication failure on people of other cultures.8. What attitudes are favored by the author towards globalization? Globalization, for better or for worse, has changed the world greatly. Whether we like it or not, globalization is all but unstoppable. It is already here to stay. It is both a fact and an opportunity. The challenges are not insurmountable. Solutions exist, and are waiting to be identified and implemented. From a globalistic point of view, there is hope and faith in humanity.Case StudyCase 1In this case, there seemed to be problems in communicating with people of different cultures in spite of the efforts made to achieve understanding.We should know that in Egypt as in many cultures, the human relationship is valued so highly that it is not expressed in an objective and impersonal way. While Americans certainly value human relationships, they are more likely to speak of them in less personal, more objective terms. In this case, Richard‘s mistake might be that he chose to praise the food itself rather than the total evening, for which the food was simply the setting or excuse. For his host and hostess it was as if he had attended an art exhibit and complimented the artist by saying, “What beautiful frames your pictures are in.”In Japan the situation may be more complicated. Japanese people value order and harmony among persons in a group, and that the organization itself-be it a family or a vast corporation-is more valued than the characteristics of any particular member. In contrast, Americans stress individuality as a value and are apt to assert individual differences when they seem justifiably in conflict with the goals or values of the group. In this case: Richard‘s mistake was in making great efforts to defend himself. Let the others assume that the errors were not intentional, but it is not right to defend yourself, even when your unstated intent is to assist the group by warning others of similar mistakes. A simple apology and acceptance of the blame would have been appropriate. But for poor Richard to have merely apologized would have seemed to him to be subservient, unmanly.When it comes to England, we expect fewer problems between Americans and Englishmen than between Americans and almost any other group. In this case we might look beyond the gesture of taking sugar or cream to the values expressed in this gesture: for Americans, ―”Help yourself”; for the Engl ish counterpart, ―”Be my guest”. American and English people equally enjoy entertaining and being entertained but they differ somewhat in the value of the distinction. Typically, the ideal guest at an American party is one who ―makes himself at home, even to the point of answering the door or fixing his own drink. For persons in many other societies, including at least this hypothetical English host, such guest behavior is presumptuous or rude.Case 2A common cultural misunderstanding in classes involves conflicts between what is said to be direct communication style and indirect communication style. InAmerican culture, people tend to say what is on their minds and to mean what they say. Therefore, students in class are expected to ask questions when they need clarification. Mexican culture shares this preference of style with American culture in some situations, and that‘s why the students from Mexico readily adopted the techniques of asking questions in class. However, Korean people generally prefer indirect communication style, and therefore they tend to not say what is on their minds and to rely more on implications and inference, so as to be polite and respectful and avoid losing face through any improper verbal behavior. As is mentioned in the case, to many Koreans, numerous questions would show a disrespect for the teacher, and would also reflect that the student has not studied hard enough.Case 3The conflict here is a difference in cultural values and beliefs. In the beginning, Mary didn’t realize that her Dominican sister saw her as a member of the family, literally. In the Dominican view, family possessions are shared by everyone of the family. Luz was acting as most Dominican sisters would do in borrowing without asking every time. Once Mary understood that there was a different way of looking at this, she would become more accepting. However, she might still experience the same frustration when this happened again. She had to find ways to cope with her own emotional cultural reaction as well as her practical problem (the batteries running out).Case 4It might be simply a question of different rhythms. Americans have one rhythm in their personal and family relations, in their friendliness and their charities. People from other cultures have different rhythms. The American rhythm is fast. It is characterized by a rapid acceptance of others.However, it is seldom that Americans engage themselves entirely in a friendship. Their friendships are warm, but casual, and specialized. For example, you have a neighbor who drops by in the morning for coffee. You see her frequently, but you never invite her for dinner --- not because you don‘t think she could handle a fork and a knife, but because you have seen her that morning.Therefore, you reserve your more formal invitation to dinner for someone who lives in a more distant part of the city and whom you would not see unless you extended an invitation for a special occasion. Now, if the first friend moves away and the second one moves nearby, you are likely to reverse this --- see the second friend in the mornings for informal coffee meetings, and the first one you will invite more formally to dinner.Americans are, in other words, guided very often by their own convenience. They tend to make friends eas ily, and they don‘t feel it necessary to go to a great amount of trouble to see friends often when it becomes inconvenient to do so, and usually no one is hurt. But in similar circumstances people from many other cultures would be hurt very deeply.。

《新编跨文化交际英语教程》复习资料U1

Unit 1 Communication across CulturesSome Ideas Related to Globalization and Intercultural Communication 1. What is globalization?Globalization refers to the increasing unification of the world’s economic order through reduction of such barriers to international trade as tariffs, export fees, and import quotas. The goal is to increase material wealth, goods, and services through an international division of labor by efficiencies catalyzed by international relations, specialization and competition. It describes the process by which regional economies, societies, and cultures have become integrated through communication, transportation, and trade. The term is most closely associated with the term economic globalization: the integration of national economies into the international economy through trade, foreign direct investment, capital flows, migration, the spread of technology, and military presence. However, globalization is usually recognized as being driven by a combination of economic, technological, sociocultural, political, and biological factors. The term can also refer to the transnational circulation of ideas, languages, or popular culture through acculturation. An aspect of the world which has gone through the process can be said to be globalized.2. The Challenge of Globalization1) Globalization poses four major challenges that will have to be addressed by governments, civil society, and other policy actors.2) The second is to deal with the fear that globalization leads to instability, which is particularly marked in the developing world. 3) The third challenge is to address the very real fear in the industrial world that increased global competition will lead inexorably to a race to the bottom in wages, labor rights, employment practices, and the environment.4) And finally, globalization and all of the complicated problems related to it must not be used as excuses to avoid searching for new ways to cooperate in the overall interest of countries and people. Several implications for civil society, for governments and for multinational institutions stem from the challenges of globalization.3. What Makes Intercultural Communication a Common Phenomenon?1) New technology, in the form of transportation and communication systems, has accelerated intercultural contact. Trips once taking days, weeks, or even months are now measured in hours. Supersonic transports now make it possible for tourists, business executives, or government officials to enjoy breakfast in San Francisco and dinner in Paris — all on the same day.2) Innovative communication systems have also encouraged and facilitatedcultural interaction. Communication satellites, sophisticated television transmission equipment, and digital switching networks now allow people throughout the world to share information and ideas instantaneously. Whether via the Internet, the World Wide Web, or a CNN news broadcast, electronic devices have increased cultural contact.3) Globalization of the economy has further brought people together. This expansion in globalization has resulted in multinational corporations participating in various international business arrangements such as joint ventures and licensing agreements. These and countless other economic ties mean that it would not be unusual for someone to work for an organization that does business in many countries.4) Changes in immigration patterns have also contributed to the development of expanded intercultural contact. Within the boundaries of the United States, people are now redefining and rethinking the meaning of the word American. Neither the word nor the reality can any longer be used to describe a somewhat homogeneous group of people sharing a European heritage.4. Six Blocks in Intercultural CommunicationAssumption of similaritiesOne answer to the question of why misunderstanding and/or rejection occurs is that many people naively assume there are sufficient similarities among peoples of the world to make communication easy. They expect that simply being human and having common requirements of food, shelter, security, and so on makes everyone alike. Unfortunately, they overlook the fact that the forms of adaptation to these common biological and social needs and the values, beliefs, and attitudes surrounding them are vastly different from culture to culture. The biological commonalties are not much help when it comes to communication, where we need to exchange ideas and information, find ways to live and work together, or just make the kind of impression we want to make.Language differencesThe second stumbling block —language difference —will surprise no one. Vocabulary, syntax, idioms, slang, dialects, and so on all cause difficulty, but the person struggling with a different language is at least aware of being in trouble.A greater language problem is the tenacity with which some people will cling to just one meaning of a word or phrase in the new language, regardless of connotation or context. The variations in possible meaning, especially when inflection and tone are varied, are so difficult to cope with that they are often waved aside. This complacency will stop a search for understanding. Even “yes” and “no” cause trouble. There are other language problems, including the different styles of using language such as direct, indirect; expansive, succinct; argumentative, conciliatory;instrumental, harmonizing; and so on. These different styles can lead to wrong interpretations of intent and evaluations of insincerity, aggressiveness, deviousness, or arrogance, among others.Nonverbal misinterpretationsLearning the language, which most visitors to foreign countries consider their only barrier to understanding, is actually only the beginning. To enter into a culture is to be able to hear its special “hum and buzz of implication.” This suggests the third stumbling block, nonverbal misinterpretations. People from different cultures inhabit different sensory realities. They see, hear, feel, and smell only that which has some meaning or importance for them. They abstract whatever fits into their personal world of recognition and then interpret it through the frame of reference of their own culture.The misinterpretation of observable nonverbal signs and symbols — such as gestures, postures, and other body movements —is a definite communication barrier. But it is possible to learn the meanings of these observable messages, usually in informal rather than formal ways. It is more difficult to understand the less obvious unspoken codes of the other cultures, such as the handling of time and spatial relationships and the subtle signs of respect of formality.Preconceptions and stereotypesThe fourth stumbling block is the presence of preconceptions and stereotypes. If the label “inscrutable” has preceded the Japanese guests, their behaviors (including the constant and seemingly inappropriate smile) will probably be seen as such. The stereotype that Arabs are “inflammable”may cause U.S. students to keep their distance or even alert authorities when an animated and noisy group from the Middle East gathers. A professor who expects everyone from Indonesia, Mexico, and many other countries to “bargain”may unfairly interpret a hesitation or request from an international student as a move to get preferential treatment. Stereotypes are over-generalized, secondhand beliefs that provide conceptual bases from which we make sense out of what goes on around us, whether or not they are accurate or fit the circumstances. In a foreign land their use increases our feelingof security. But stereotypes are stumbling blocks for communicators because they interfere with objective viewing of other people. They are not easy to overcome in ourselves or to correct in others, even with the presentation of evidence. Stereotypes persist because they are firmly established as myths or truisms by one’s own culture and because they sometimes rationalize prejudices. They are also sustained and fed by the tendency to perceive selectively only those pieces of new information that correspond to the images we hold.Tendency to evaluateThe fifth stumbling block to understanding between persons ofdiffering cultures is the tendency to evaluate, to approve or disapprove, the statements and actions of the other person or group. Rather than try to comprehend thoughts and feelings from the worldview of the other, we assume our own culture or way of life is the most natural. This bias prevents the open-mindedness needed to examine attitudes and behaviors from the other’s point of view.The miscommunication caused by immediate evaluation is heightened when feelings and emotions are deeply involved; yet this is just the time when listening with understanding is most needed.The admonition to resist the tendency to immediately evaluate does not mean that one should not develop one’s own sense of right and wrong. The goal is to look and listen empathetically rather than through the thick screen of value judgments that impede a fair and total understanding. Once comprehension is complete, it can be determined whether or not there is a clash in values or ideology. If so, some form of adjustment or conflict resolution can be put into place.High anxietyHigh anxiety or tension, also known as stress, is common in Cross-cultural experiences due to the number of uncertainties present. The two words, anxiety and tension, are linked because one cannot be mentally anxious without also being physically tense. Moderate tension and positive attitudes prepare one to meet challenges with energy. Too much anxiety or tension requires some form of relief, which too often comes in the form of defenses, such as the skewing of perceptions, withdrawal, or hostility. That’s why it is considered a serious stumbling block. Anxious feelings usually permeate both parties in an intercultural dialogue. The host national is uncomfortable when talking with a foreigner because he or she cannot maintain the normal flow of verbal and nonverbal interaction. There are language and perception barriers; silences are too long or too short; and some other norms may be violated. He or she is also threatened by the other’s unknown knowledge, experience and evaluation.Reading IIntercultural Communication:An Introduction Comprehension questions1. Is it still often the case that “everyone‟s quick to blame the alien”in the contemporary world?This is still powerful in today‘s social and political rhetoric. For instance, it is not uncommon in today‘s society to hear people say that most, if not all, of the social and economic problems are caused by minorities and immigrants.2. What‟s the difference between today‟s intercultural contact and that of any time in the past?Today‘s intercultural encounters are far more numerous and of greater importance than in any time in history.3. What have made intercultural contact a very common phenomenon in our life today?New technology, in the form of transportation and communication systems, has accelerated intercultural contact; innovative communication systems have encouraged and facilitated cultural interaction; globalization of the economy has brought people together; changes in immigration patterns have also contributed to intercultural encounter.4. How do you understand the sentence “culture is everything and everywhere”?Culture supplies us with the answers to questions about what the world looks like and how we live and communicate within that world. Culture teaches us how to behave in our life from the instant of birth. It is omnipresent.5. What are the major elements that directly influence our perception and communication?The three major socio-cultural elements that directly influence perception and communication are cultural values, worldview (religion), and social organizations (family and state).6. What does one‟s family teach him or her while he or she grows up in it?The family teaches the child what the world looks like and his or her place in that world.7. Why is it impossible to separate our use of language from our culture? Because language is not only a form of preserving culture but also a means of sharing culture. Language is an organized, generally agreed-upon, learned symbol system that is used to represent the experiences within a cultural community.8. What are the nonverbal behaviors that people can attach meaning to? People can attach meaning to nonverbal behaviors such as gestures, postures, facial expressions, eye contact and gaze, touch, etc.9. How can a free, culturally diverse society exist?A free, culturally diverse society can exist only if diversity is permitted to flourish without prejudice and discrimination, both of which harm all members of the society.Reading IIThe Challenge of GlobalizationComprehension questions1. Why does the author say that our understanding of the world has changed? Many things, such as political changes and technological advances, have changed the world very rapidly. In the past most human beings were born, lived, and died within a limited geographical area, never encountering people of other cultural backgrounds. Such an existence, however, no longer prevails in the world. Thus, all people are faced with the challenge of understanding this changed and still fast changing world in which we live.2. What a “global village” is like?As our world shrinks and its inhabitants become interdependent, people from remote cultures increasingly come into contact on a daily basis. In a global village, members of once isolated groups of people have to communicate with members of other cultural groups. Those people may live thousands of miles away or right next door to each other.3. What is considered as the major driving force of the post-1945 globalization?Technology, particularly telecommunications and computers are considered to be the major driving force.4. What does the author mean by saying that “the …global‟ may be more local than the …local‟”?The increasing global mobility of people and the impact of new electronic media on human communications make the world seem smaller. We may communicate more with people of other countries than with our neighbors, and we may be more informed of the international events than of the local events. In this sense, “the‘ global’may be more local than the ‘local’”5. Why is it important for businesspeople to know diverse cultures in the world?Effective communication may be the most important competitive advantage that firms have to meet diverse customer needs on a global basis. Succeeding in the global market today requires theability to communicate sensitively with people from other cultures, a sensitivity that is based on an understanding of cross-cultural differences.6. What are the serious problems that countries throughout the world are confronted with?Countries throughout the world are confronted with serious problemssuch as volatile international economy, shrinking resources, mounting environmental contamination, and epidemics that know no boundaries.7. What implications can we draw from the case of Michael Fay?This case shows that in a world of international interdependence, the ability to understand and communicate effectively with people from other cultures takes on extreme urgency. If we are unaware of the significant role culture plays in communication, we may place the blame for communication failure on people of other cultures.8. What attitudes are favored by the author towards globalization?Globalization, for better or for worse, has changed the world greatly. Whether we like it or not, globalization is all but unstoppable. It is already here to stay. It is both a fact and an opportunity. The challenges are not insurmountable. Solutions exist, and are waiting to be identified and implemented. From a globalistic point of view, there is hope and faith in humanity.Case StudyCase 1In this case, there seemed to be problems in communicating with people of different cultures in spite of the efforts made to achieve understanding. We should know that in Egypt as in many cultures, the human relationship is valued so highly that it is not expressed in an objective and impersonal way. While Americans certainly value human relationships, they are more likely to speak of them in less personal, more objective terms. In this case, Richard‘s mistake might be that he chose to praise the food itself rather than the total evening, for which the food was simply the setting or excuse. For his host and hostess it was as if he had attended an art exhibit and complimented the artist by saying, What beautiful frames your pictures are in.In Japan the situation may be more complicated. Japanese people value order and harmony among persons in a group, and that the organization itself-be it a family or a vast corporation-is more valued than the characteristics of any particular member. In contrast, Americans stress individuality as a value and are apt to assert individual differences when they seem justifiably in conflict with the goals or values of the group. In this case: Richard‘s mistake was in making great efforts to defend himself. Let the others assume that the errors were not intentional, but it is not right to defend yourself, even when your unstated intent is to assist the group by warning others of similar mistakes. A simple apology and acceptance of the blame would have been appropriate. But for poor Richard to have merely apologized would have seemed to him to be subservient, unmanly.When it comes to England, we expect fewer problems between Americans and Englishmen than between Americans and almost any other group. In this case we might look beyond the gesture of taking sugar or cream to the values expressed in this gesture: for Americans, ―Help yourself; for the English counterpart, ―Be my guest. American and English people equally enjoy entertaining and being entertained but they differ somewhat in the value of the distinction. Typically, the ideal guest at an American party is one who ―makes himself at home, even to the point of answering the door or fixing his own drink. For persons in many other societies, including at least this hypothetical English host, such guest behavior is presumptuous or rude.Case 2A common cultural misunderstanding in classes involves conflicts between what is said to be direct communication style and indirect communication style. In American culture, people tend to say what is on their minds and to mean what they say. Therefore, students in class are expected to ask questions when they need clarification. Mexican culture shares this preference of style with American culture in some situations, and that‘s why the students from Mexico readily adopted the techniques of asking questions in class. However, Korean people generally prefer indirect communication style, and therefore they tend to not say what is on their minds and to rely more on implications and inference, so as to be polite and respectful and avoid losing face through any improper verbal behavior. As is mentioned in the case, to many Koreans, numerous questions would show a disrespect for the teacher, and would also reflect that the student has not studied hard enough.Case 3The conflict here is a difference in cultural values and beliefs. In the beginning, Mary didn‘t realize that her Dominican sister saw her as a member of the family, literally. In the Dominican view, family possessions are shared by everyone of the family. Luz was acting as most Dominican sisters would do in borrowing without asking every time. Once Mary understood that there was a different way of looking at this, she would become more accepting. However, she might still experience the same frustration when this happened again. She had to find ways to cope with her own emotional cultural reaction as well as her practical problem (the batteries running out).Case 4It might be simply a question of different rhythms. Americans have one rhythm in their personal and family relations, in their friendliness and their charities. People from other cultures have different rhythms. TheAmerican rhythm is fast. It is characterized by a rapid acceptance of others. However, it is seldom that Americans engage themselves entirely in a friendship. Their friendships are warm, but casual, and specialized. For example, you have a neighbor who drops by in the morning for coffee. You see her frequently, but you never invite her for dinner --- not because youdon‘t think she could handle a fork and a knife, but because you have seen her that morning. Therefore, you reserve your more formal invitation to dinner for someone who lives in a more distant part of the city and whom you would not see unless you extended an invitation for a special occasion. Now, if the first friend moves away and the second one moves nearby, you are likely to reverse this --- see the second friend in the mornings for informal coffee meetings, and the first one you will invite more formally to dinner.Americans are, in other words, guided very often by their own convenience. They tend to make friends easily, and they don‘t feel it necessary to go to a great amount of trouble to see friends often when it becomes inconvenient to do so, and usually no one is hurt. But in similar circumstances people from many other cultures would be hurt very deeply.。

跨文化交际复习unit 1

Unit 1 An introduction to Intercultural Communication

celiadan22@

1. Warm-up Exercises

1) Proverbs and sayings 2) Questions 3) A Comparative study

c. How: How should the communicators deal with the differences so as to communicate with each other effectively or successfully?

影响跨文化交际的三个变项: 一是观察事物过程:其中包括信念、价值观念、态度、 世界观及社会组织。 二是语言过程:其中包括语言及思维模式。

?从人类活动范围看可专门研究不同文化中家庭成员的关系的关系师生关系雇主与雇员的关系顾客与店主师生关系雇主与雇员的关系顾客与店主的关系熟人朋友之间陌生人之间的交际方式等等

Intercultural Communications

2012-2013

Contents

Unit 1 An introduction to Intercultural Communication Unit 2 Culture and Communication Unit 3 Daily Verbal Communication Unit 4 Verbal Communication Unit 5 Language and Culture Unit 6 Nonverbal Communication Unit 7 Cultural Differences Unit 8 Intercultural Adaptation

新编跨文化交际英语教程知识点梳理

新编跨文化交际英语教程知识点梳理新编跨文化交际英语教程是一本专门针对跨文化交际的英语教材,旨在帮助学习者提高在不同文化背景下的英语交际能力。

本文将对这本教材的知识点进行梳理,并按照标题的要求进行详细阐述。

一、跨文化交际的概念与重要性跨文化交际是指在不同文化背景下进行有效沟通和交流的能力。

随着全球化的发展,跨文化交际能力对个人和组织来说变得越来越重要。

教材首先介绍了跨文化交际的概念和重要性,引导学习者认识到学习跨文化交际的必要性。

二、文化差异的认知与理解文化差异是跨文化交际的核心问题之一。

教材通过介绍不同国家和地区的文化背景,让学习者认识到不同文化之间的差异。

例如,西方国家强调个人主义,而亚洲国家则更注重集体主义;西方人通常直接表达意见,而东方人更倾向于含蓄表达。

通过了解这些文化差异,学习者可以更好地适应和理解不同文化的交际方式。

三、语言与文化的关系语言是文化的重要组成部分,也是跨文化交际的基础。

教材通过对语言与文化的关系进行介绍,让学习者认识到不同语言背后的文化内涵。

例如,英语中的一些习语和隐喻在其他语言中可能没有对应的表达,这就需要学习者在跨文化交际中注意语言的使用。

四、非语言交际与文化除了语言交际外,非语言交际也是跨文化交际中不可忽视的因素。

教材通过介绍非语言交际的方式和特点,让学习者了解不同文化中的非语言行为习惯和意义。

例如,西方人习惯于握手问候,而东方人则更多使用鞠躬。

通过了解这些非语言交际的差异,学习者可以更准确地理解和表达自己的意思。

五、跨文化交际中的礼仪与文化礼仪是不同文化交际中的重要组成部分。

教材通过介绍不同文化中的礼仪规范和习俗,让学习者了解在不同文化中应该如何表现和应对。

例如,在西方国家用餐时,吃完后将刀叉并排放在盘子上表示已经用完;而在中国,将筷子插在饭中是不礼貌的行为。

学习者通过学习这些礼仪规范,可以更好地适应不同文化的环境。

六、文化冲突与解决在跨文化交际中,文化冲突是难免的。

新编跨文化交际英语教程 复习总结

Unit 11.The definition of INTERCULTURAL COMMUNICATION1.1“Inter-" comes from the Latin word for "between",and dictionaries define communication as exchanging information.Inter-"来自拉丁语,意思是"在之间",字典把交流定义为交换信息。

Intercultural Communication refers to the exchange of information between people from different cultures.跨文化交际是指来自不同文化的人之间的信息交流。

As the very phrase suggests, Intercultural Communication emphasizes cross-cultural competence rather than language only.正如这句话所暗示的,跨文化交际强调的是跨文化能力,而不仅仅是语言。

1.2 what makes IC a common phenomenon: new technology, innovative communication system,globalization of the economy , changes in immigration patterns 新技术、创新的通讯系统、经济全球化、移民模式的变化2.The definition of globalizationGlobalization is the process by which regional economies, societies, and cultures have become integrated through communication, transportation,and trade between nations.全球化是区域经济、社会和文化通过国家之间的交流、运输和贸易而变得一体化的过程。

跨文化交际英语知识点归纳

跨文化交际英语知识点归纳1. 礼仪(Etiquette)礼仪是不同文化交往中最基本的要素之一。

在跨文化交际中,礼仪的重要性不言而喻。

例如,不同国家、不同文化的人在相互交往时,他们的相互礼仪的表达方式都是有所不同的。

2. 规范和价值观(Norms and Values)规范是一种文化内部形成的行为结构,是一种文化共同遵守的行为方式。

在跨文化交际中,了解对方所遵循的规范是非常重要的,这有助于避免在交流中出现不必要的误解和冲突。

3. 语言和文化(Language and Culture)语言是人类进行交流的最基本手段。

语言和文化是紧密相关的。

例如,美国英语和英国英语在用词和发音上有所不同,这也反映出两个国家的文化差异。

4. 非语言交际(Non-Verbal Communication)除了语言外,身体语言、肢体动作、面部表情、姿势等非语言交际也是跨文化交际中不可忽视的因素。

这些非语言交际动作在不同文化间也存在差异。

5. 社会组织形态和社会关系(Social Organization and Relationships)不同文化的社会组织形态和社会关系也是非常不同的。

例如,中国传统文化中注重家庭、亲情和社会关系,而西方文化则注重个性、自由和独立性。

6. 时间观念(Time)不同国家和文化对时间观念的重视程度也存在差异。

例如,在日本文化中,迟到被看作是不尊重别人的行为,而在西方文化中,稍微迟到几分钟不会被认为是什么大问题。

7. 社会礼仪和礼节(Social Etiquette and Formalities)在跨文化交际中,了解对方的社会礼仪和礼节也是非常重要的。

例如,上司和下属之间的交往在不同文化中有着不同的礼节和规范。

8. 语言表达方式和文化复杂性(Language Expression and Cultural Complexity)语言表达方式和文化的复杂性也是跨文化交际中重要的要素之一。

不同文化的语言表达方式有着不同的复杂度和难度,了解这些差异有助于更好地理解对方文化的复杂度。

Unit 1 An Introduction Intercultural Communication 跨文化交际复习指导资料

2012-2-16

12

4. People are religiously different.

Christianity. About 21.4 billion Christians in the world. Bible. For philanthropy and equal for everybody.

2012-2-16

19

The Objectives

1) To explore cultural self-awareness, other culture

awareness and the dynamics that arise in interactions between the two. 2) To understand how communication processes differ among cultures. 3) To identify challenges that arise from these differences in intercultural interactions and learn ways to creatively address them. 4) To acquire knowledge and develop skills that increase intercultural competence. 5) To have an understanding of the meaning of the cultures understood by the westerners and the easterners or the Chinese and Americans.

2012-2-16

14

5. People are ideologically different.

新编跨文化交际课程 Unit 1 Further reading 2

6、erosion: destroy, the act of weakening sth. erode: to gt weaker. Her confidence has been slowly eroded by repeated failures. 7、cluster: n. a group of things of the same type that grow or appear close together; a group of people, animals or things close together. v. to come together in small group or groups A cluster of grapes\flowers\bees

4、(paragraph 2) disgorge: to pour sth out in large quantity; to be forced to hand sth out The factory was found to be disgorging effluent into the river. He disgorged the money stolen. 5、The methods for bringing people closer physically and electronically are clearly at hand. at hand: I haven’t my book at hand, but I will show it to you later. The autumn harvest is at hand.

Unit 1

Further reading 2

Communication in the Global Village

新编跨文化交际英语教程知识点梳理

新编跨文化交际英语教程知识点梳理(实用版)目录1.新编跨文化交际英语教程的概念与目的2.跨文化交际的重要性3.新编跨文化交际英语教程的主要内容4.新编跨文化交际英语教程的特点与亮点5.新编跨文化交际英语教程的应用与实践正文一、新编跨文化交际英语教程的概念与目的新编跨文化交际英语教程是一本针对英语学习者的教材,旨在帮助学生更好地理解和应对跨文化交际中的各种问题。

该教程通过讲解文化、交际、语言以及跨文化交际等相关概念,使学生能够较为客观、系统、全面地认识英语国家的文化,从而提高跨文化交际能力。

二、跨文化交际的重要性随着全球化的不断深入,跨文化交际在我们的生活中扮演着越来越重要的角色。

对于英语学习者来说,掌握跨文化交际的能力不仅能够帮助他们更自信地与来自不同文化背景的人进行交流,还能够拓宽他们的国际视野,提高他们的综合素质。

三、新编跨文化交际英语教程的主要内容新编跨文化交际英语教程共分为 10 个单元,涵盖了全球化时代的交际问题、文化与交际、各类文化差异、语言与文化、跨文化言语交际、跨文化非言语交际、时间与空间使用上的文化、跨文化感知、跨文化适应、跨文化能力等各个方面。

每个单元都以阅读文章为主线,配有形式多样的练习和数量较多的案例分析,同时还提供丰富的相关文化背景知识材料,供选择使用,以满足不同的教学情境和需求。

四、新编跨文化交际英语教程的特点与亮点新编跨文化交际英语教程具有以下特点和亮点:1.实用性:教材选材广泛,包括了几十个实例,既有趣味性,又有实用性,能够帮助学生在实际交际中更好地运用所学知识。

2.系统性:教程对跨文化交际的各个方面进行了全面、深入的讲解,使学生能够系统地掌握跨文化交际的知识和技能。

3.灵活性:教材形式多样,既有阅读文章,又有练习和案例分析,能够满足不同学生的学习需求和教学情境。

4.丰富性:教材提供了丰富的相关文化背景知识材料,帮助学生更好地理解和感知英语国家的文化。

五、新编跨文化交际英语教程的应用与实践新编跨文化交际英语教程在实际应用中,可以通过以下方式进行实践:1.在课堂教学中,教师可以结合教材的内容,进行跨文化交际的讲解和训练,帮助学生提高跨文化交际能力。

新编跨文化交际学unit1

Intercultural skills Presentation communication

Introduction 1

1. How did intercultural communication occur in earlier years? 2. How did people recognize the alien difference? 3. How do Americans think of their social and economic problems? 4. What’s the difference between today’s intercultural contact and that of any time in the past? 5. What has accelerated intercultural contact? How to illustrate it?

Intercultural skills Presentation communication

1. How do you understand the sentence “culture is everything and everywhere.”? culture; what the world looks like and how you live and communicate 2. How does culture determine and guide people’s communication behavior? How to dress, what toys to play with, what to eat, which gods to worship, how to spend your money and time ; world looks, sounds, tastes and feels the way it does ; criterion of perception

新编跨文化交际英语教程复习资料详解

导言“新编跨文化交际英语教程•教师用书”主要是为使用“新编跨文化交际英语教程”教师配套的教学指南。

“新编跨文化交际英语教程”是在原有“跨文化交际英语教程”的基础上经过全面、系统修订而成,我们对全书做了较大的更新和完善,调整和增补了许多材料,力求使其更具时代性,更适合教学实际和学生需求。

为了进一步推进跨文化交际教学,在多年从事跨文化交际教学和研究的基础上,我们又特地编写了这本“新编跨文化交际英语教程•教师用书”,希望能对使用本教材进行教学的广大教师们,尤其是初次使用这本教材的教师们提供一些必要的引导和实质性的帮助。

为此,我们尽可能地为各单元中几乎所有的部分和项目都提供了参考提示。

除此之外,还补充了一些取自跨文化交际学重要著作的选段,供教师进一步了解相关背景知识和理论基础,以拓宽视野,有利于更好地进行教学。

同时我们还在书后附上了推荐的中文阅读书目(英文阅读书目可参看上海外语教育出版社的“跨文化交际丛书”系列)和有关跨文化交际的部分电影资料简介。

“新编跨文化交际英语教程”主要适用于高等学校英语专业教学中的跨文化交际课程,旨在通过课堂教学及相关活动使学生认识跨文化交际对当代世界所具有的重要意义和作用,了解文化对人类生活各个方面、尤其是交际活动的制约和影响,理解并把握交际活动的重要性、丰富性、复杂性,熟悉跨文化交际的基本构成以及所涉及的各种因素,培养跨文化意识,形成和发展对文化差异的敏感和宽容、以及处理文化差异问题的灵活性,提高使用英语进行跨文化交际的技能,为最终获得与不同文化背景人们进行深入交流的能力奠定基础。

通过使用本教材,教师也可从中获得更多有关文化(包括我们自己文化和外族文化)和跨文化交际的知识。

这本教材共分为10 个单元,涉及全球化时代的交际问题、文化与交际、各类文化差异、语言与文化、跨文化言语交际、跨文化非言语交际、时间与空间使用上的文化、跨文化感知、跨文化适应、跨文化能力等,包括了跨文化交际的各个方面,对其中一些重要问题都有相对深入的介绍与探讨。

新编跨文化交际英语教程课后练习题含答案

新编跨文化交际英语教程课后练习题含答案介绍跨文化交际英语教程是针对外语专业学生开设的一门课程,旨在培养学生跨越语言和文化差异的能力。

本文档是新编跨文化交际英语教程的课后练习题,含有答案。

练习题Unit 1 练习题1.What is culture? How does it affect communication?2.Can you give some examples of cultural differences betweenChina and your country?3.Why is it important to be aware of cultural differences incommunication?4.What are the advantages of studying cross-culturalcommunication?5.What are the challenges of cross-cultural communication?答案1.Culture refers to the shared values, beliefs, customs,behaviors, attitudes, and artifacts that characterize a group orsociety. Culture can affect communication in many ways, such asthrough differences in language, nonverbal cues, social norms, and power structures.2.答案根据不同国家而异。

1。

新编跨文化交际期末复习资料

新编跨文化交际期末复习资料1.Iceberg: {Edward. 7. Hall.--<The silence of language>标志着“跨文化交流”学科的开始} Culture can be viewed as an iceberg. Nine-tenths of an iceberg is out of sight (below the water line). Likewise, nine-tenths of culture is outside of conscious awareness. The part of the cultural iceberg that above the water is easy to be noticed. The out-of-awareness part is sometimes called “deep culture”. This part of the cultural iceberg is hidden below the water and is thus below the level of consciousness. People learn this part of culture through imitating models. / Above the water: what to eat, how to dress, how to keep healthy;Below the water: belief, values, worldview and lifeview, moral emotion, attitude personalty2.Stereotype:定型主义a stereotype is a fixed notion about persons in a certain category, with no distinctions made among individuals. In other words, it is an overgeneralized and oversimplified belief we use to categorize a group of people.3.Ethnocentrism: 民族中心主义Ethnocentrism is the technical name for the view of things in which one’s own group is the center of everything, and all others are scaled and rated with reference to it. It refers to our tendency to identify with our in-group and to evaluate out-groups and their members according to its standard.4.Culture: Culture can be defined as the coherent, learned, shared view of group of people about life’s concerns that ranks what is important, furnishes attitudes about what things are appropriate, and dictates behavior.5.Cultural values: Values inform a member of a culture about what is good and bad, right and wrong, true and false, positive and negative, and the like. Cultural values defines what is worth dying for, what is worth protecting, what frightens people, what are proper subjects for study and for ridicule, and what types of events lead individuals to group solidarity.6.Worldview: A worldview is a culture’s orientation toward such things as God, nature, life, death, the universe, and other philosophical issues that are concerned with the meaning of life and with “being”.7.Social Organizations: The manner in which a culture organizes itself is directly related to the institution within that culture. The families who raise you and the goverments with which you associate and hold allegiance to all help determine hoe you perceive the world and how you behave within that world.8.Globalization: refers to the establishment of a world economy, in which national borders are becoming less and less important as transnational corporations, existing everywhere and nowhere, do business in a global market.munication: Communication is any behavior that is perceived by others. So it can be verbal and nonverbal, informative or persuasive, frightening or amusing, clear or unclear, purposeful oraccidental, communication is our link to the rest of the humanity. It pervades everything we do. 10.Elements of communication process:交流过程的基本原理(1).context: The interrelated conditions of communication make up what is known as context. (2).The participants: in communication play the roles of sender and receiver, sometimes—as in face-to-face communication—of the messages simultaneously.(3). messages: are far more complex. They include the elements of meanings, symbols, encoding and decoding.(4). A channels: is both the route traveled by the messages and the means of transportation. We may use sound, sight, smell, taste, touch, or any combination of these to carry a message.(5). noise: is any stimulus, external or internal to the participants, that interferes with the sharing of meaning. External noise: sight, sound…Internal noise: thoughts, feeling…Semantic noise: unintended meaning aroused by certain verbal symbols can inhibit the accuracy of decoding. (6).Feedback: As receivers attempt to decode the meaning of messages, they are likely to give some kind of verbal or nonverbal response. This response, called feedback, tells the sender whether the massage has been heard, seen, or understood.11.Abraham Mslow (亚伯拉罕•马斯洛) –five basic needs五个需求1. physiological needs—food, water, air, rest, clothing, shelter, and all necessary to sustain life2. safety needs—physically safe, psychologically secure3. belongingness needs—accepted by other people and needs to belong to a group or groups.4. esteem needs—recognition, respect, reputation5. self-actualization needs-the highest need of a person12.Culture Dimensions 文化维度13.A High-context: 内向型communication or message is one in which most of the information is either in the context or internalized in the person, while very little is in the context or internalized in the person, while very little is in the coded, explicit, transmitted part of the message. Eg. Japanese, Chinese, Korean, African American, Native American. self-effacement隐匿自我A Low-context:外向型communication is just the opposite, the mass of the information is vested in the explicit code, and the context or situation plays a minimal role. Eg. German-Swiss, German, Scandinavian, American, French, English self-enhancement凸显自我Low-context interaction emphasizes direct talk, person-oriented focus, self-enhancement mode, and the importance of “talk”. High-context interaction, in comparison, stresses indirect talk, status-oriented focus, self-effacement mode, and the importance of nonverbal signals and even silence.Eg: In Scene 1 and spell out everything that is on their minds with no restraints. Their interaction exchange is direct, to the point, bluntly contentious, and full of face-threat verbal message. Scene 1 represents one possible low-context way of approaching interpersonal conflict.In Scene 2, has not directly expressed her concern over the piano noise with because she wants to preserve face and her relationship with . Rather, only uses indirect hints and nonverbal signals to get her point across. However, correctly “reads between the lines” of verbal message and apologizes appropriately and effectively before a real conflict can bubble to surface. Scene 2 represents one possible high-context way of approaching interpersonal conflict. Direct and Indirect Verbal Interaction Styles self-enhancement and self-effacement凸显自我,隐匿自我In the direct verb al style, statements clearly reveal the speaker’s intentions and are enunciated in a forthright tone of voice. In the indirect verbal style, verbal statements tend to camouflage the speaker’s actual intentions and are carried out with more nuanced tone of voice.14.Colors: Black: death, evil, mourning, sexy; Blue-cold, sad, sky, masculine; Green-envy, greed, money; Pink: feminine, shy, softness, sweet; Red: anger, hot, love, sex; White: good, innocent, peaceful, pure; Yellow: caution, happy, sunshine, warm15.Functions of Nonverbal Communication: repeating, complementing, substituting, regulating contradicting16.Confucian teaching key principles: 1.Social order and stability are based on unequal relationships between people. 2. The family is the prototype for all social relationships. 3. Proper social behavior consist of not treating others as you would not like to be treated yourself. 4. People should be skilled , educated, hardworking, thrifty, modest, patient, and persevering.Four books and five classical: The Analects of Confucian <论语>, Mencius <孟子>,Great Learning <大学>,The Doctrines of Mean <中庸> / Classic of poetry <诗经>,Book of documents <尚书>, Book of kites <礼记>, Classic of changes <周易>, Spring and Autumn Annals <春秋>. 仁义礼智信:merciful, justified, polite, intelligent, honest17.The Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis: language becomes our shaper of ideas rather than simple our tool for reporting ideas, language influenced or even determined the ways in which people thought. The central idea of the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis is that language functions, not simply as a device for reporting experience, but also, and more significantly, as a way of defining experience for itsspeakerInfluence: The Sapir-Whorf hypothesis has alerted people to the fact language is keyed to the total culture, and that it reveals a people’s view of its total environment. Language directs the perceptions of its speakers to certain things; it gives them ways to analyze and to categorize experience. Such perceptions are unconscious and outside the control of the speaker. The ultimate value of the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis is that it offers hints to cultural differences and similarities among people.18.The way people speakHigh involvement高度卷入: 1. talk more 2. interrupt more 3. expect to be interrupted 4. talk more loudly at times 5. talk more quickly. Eg. Russian, Italian, Greek, Spanish, South American, Arab, AfricanHigh considerateness高度体谅: 1, speak one at a time 2. use polite listening sounds, 3. refrain from interrupting, 4. give plenty of positive and respectful responses to their conversation partners. Eg. Mainstream American19.文化维度Orientation—Kluckhohns and Strodtbeck Beliefs and Behaviors20.Chinese VS English-----Chinese: open, visual, old. English: close, changing, modern21.Stumbling Blocks in Intercultural Communication跨文化交际中的绊脚石(1) Assumption of similarities假定相似(2) Language differences (3) Nonverbal misinterpretations不用言语表达的误解(4) Preconception先入为主的概念的固定形式(5) Tendency to evaluate评价意图(6) High anxiety焦虑(7) Conclusion22. Essentials of Human Communication(1) Communication is a dynamic process. (2) Communication is symbolic. (3) Communication is systemic. (4) Communication involves making inferences. (5) Communication has a consequence 23. How is language related to cultureCulture and language are intertwined and shape each other. In our own environment we aware of the implications of these choices. All languages have social questions and information questions.The point is that words in themselves do not carry the meaning. The meaning comes out of the context the cultural usage. In addition to the environment, language reflects cultural values.24.More words/expression→important role in cultureIn Chinese we have many kinship terms, some of which seem to have no equivalents in English. Compared with Chinese, English has fewer kinship terms. The difference is not just linguistic; it is infundamentally cultural.25.A culture’s conception of time can be examined from three different perspectives:1. informal time; 2. perceptions of past, present, and future; 3. monochromic and polychromic.26.Monochronic(M-time) 单维时间and polychromic(P-time)多维时间Monochronic people:美国人Do one thing at a time. Concentrate on the job. Take time commitments seriously. Are committed to the job. Adhere to plans. Are concerned about not disturbing others; follow rules of privacy. Show great respect for private property; seldom borrow or lend. Emphasize promptness. Are accustomed to short-term relationships.Polychromic people: 中国人Do many things at once. Are easily distracted and subject to interruptions. Consider time commitments an objective to be achieved, if possible. Are committed to people and human relationships. Change plans often and easily. Are more concerned with people close to them(family, friend, close business associates) than with privacy. Borrow and lend things often and easily. Base promptness on the relationship. Have strong tendency to build lifetime relationships.27.Adapting to a New Cultureculture shock.: Any number of symptoms征兆can occur during cycles of culture shock. These symptoms can be (1)physiological (2)emotionally (3)communicationPredeparture stage: Stage one: everything is beautiful. Stage two: everything is awful. Stage three: everything is OK.Adaptation and reentry再进入Methods: 1. patience. 2. meet new people. 3. try new things. 4. give yourself periods of rest and thought. 5. work on your self-concept. 6. write. 7. observe body language. 8. learn the verbal language.。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。