大学体验英语4 7-A课文

第三版大学体验英语综合教程4Unit7

Unit 7Listen1 no more killing and stealing 2.will be able to have money 3. finding more things to explore and finding a cure for AIDS and for cancer 4. being cared for by those with more money 5. will be able to help the black people and not hating themThink about it1.Global recession is defined as an extended period of international economic downturn. Generally, the InternationalMonetary Fund (IMF) considers a global recession as a period where gross domestic product (GDP) growth is at 3% or less. In addition to that, the IMF looks at declines in real per-capita world GDP along with several globalmacroeconomic factors before confirming a global recession. The global recession starting from 2008 is a marked global economic decline that has affected the entire world economy. It is a major global recession characterized by various systemic imbalances in the world.2.Few families have escaped the pain of this terrible recession. More than seven million Americans have lost their jobs,and countless businesses have been forced to shut their doors.3.Whenever we are in difficulties, nothing beats the support and love of our family. As everyone would agree, family isthe first harbor of our journey and the terminal as well. No matter how fierce the wave outside might be, we know there would be a place for us to be safe and warm at home.爱意味着永远不会说“找工作去”我和我大学时的恋人结婚将近24年了。

大学英语四(综合教程)第七单元

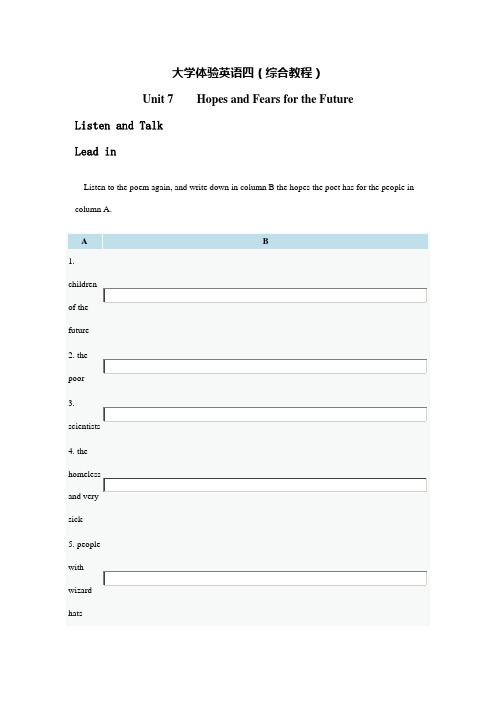

大学体验英语四(综合教程)Unit 7Hopes and Fears for the FutureListen and TalkLead inListen to the poem again, and write down in column B the hopes the poet has for the people in column A.Key:1. no more killing and stealing 2. will be able to have money 3. finding more things to explore and finding a cure for AIDS and for cancer 4. being cared for by those with more money 5. will be able to help the black people and not hating themPassage A: Facing the Fears of Retirement2. Choose the best answer to each question based on the information you obtain from the passage.1. From the passage we can learn that ________.A) people hold three beliefs preventing them from retiringB) the older people get, the more reluctant they are to retireC) retirement is merely a matter of power transferD) all people have to pass the "final test of greatness” before retirement2. The expression "let go” means ________.A) to dismiss the successorB) to close the businessC) to explore another fieldD) to pass the business to the successor3. What makes some of the business owners willing to retire?A) Their family background.B) The scale of their business.C) Their attitude towards retirement.D) The ability of their successor.4. According to the passage, people with the sound attitude to retirement think that ________.A) old people are bound to restB) retirement means new opportunities and new lifeC) as business owners, they are indispensable to the businessD) their business was bought as part of management5. The author's purpose of writing this passage is ________.A) elaborate on the three prevalent beliefs held by those who cannot conclude succession planningB) illustrate the different attitudes toward retirement in different situationsC) offer some practical tips to those who are not able to cope with fear of retirementD) urge society and the individual to take retirement more seriouslyAnswer: 1.A, 2.D, 3.C, 4.B, 5.C3. Answer the following questions with the information from the passage.1. What did the 77-year old business founder do after retirement?He took back control of the firm from his son, who had succeeded him.2. What’s the most impor tant thing for family-business continuity?Entrepreneurial succession.3. Why can the business owners who purchased their firms as part of a management buyout face retirement easily?Because they recognize that CEO’s change but the business goes on.4. Wha t does the expression "the glass is half full, not half empty” mean?It is an optimistic attitude to life, implying that the glass is still full, although only half full. The pessimists would say is: "The glass is half empty.”5. What’s the "final test of greatness” according to Peter Drucker?Succession planning.plete the summary of the text. The first letter of the missing word has been given to you.This article addresses the 1) r of many business owners to engage in 2) s planning. It states that there are three main reasons why business owners do not want to retire from their business: firstly, a fear of an 3) u future, secondly, a fear of 4) f loss, and lastly, a fear of losing their personal 5) i . The author states that because of these fears, succession planning is often a painful experience for both the retiree and the new business owners, involving a great deal of unnecessary interpersonal 6) c and negative emotions.The author points out that this can be avoided, and it comes dwon to the attitude that business owners adopt. Retiring business owners should always 7) r that the business that they are leaving can continue to operate 8) s without them. Furthermore, they should view retirement, not just as the completion of their working life, but rather, as a world of new challenges in which new interests and 9) o can be pursued.Anwser: 1.reluctance 2.succession 3.uncertain 4.financial 5.identity6.conflicts7.recognize8.successfully9.opportunities4. Fill in the blanks with the words given below. Change the form where necessary.acclaim succession impose generate indispensablefragile graceful insecurity accomplish prevalent1. Adams took a ___ of jobs which have stood him in good stead.2. Is this eye-disease still ___ among the population here?3. Older drivers are more likely to be seriously injured because of their ___ bones.4. The accident in Russia ___ a lot of public interest in nuclear power issues.5. If we'd all work together, I think we could ___ our goal.6. He was still charming, cheerful, and ___ even under pressure.7. The bank has ___ very strict conditions on the repayment of the loan.8. His made-up confident manner is really just a way of hiding his feeling of ___ .9. With the rapid development of the Internet, a computer becomes a(n) ___ piece of equipment for any office.10. Since it was published in the 1970s, the book has received considerable critical ___ . Answer: 1. succession 2. prevalent 3. fragile 4. generated 5. accomplish6. graceful7. imposed8. insecurity9. indispensable 10. acclaim5. Complete the following sentences with phrases or expressions from the passage.1. The tension was naturally high for a game with so much ___ .2. She still ___ the belief that her son is alive.3. I finished my work at five, but I'll ___ until half past five to meet you.4. After 50 years of successful operation, he ___the business ____ to his youngest son.5. The scientist ___ the discovery ___ the most exciting new development in this field. Answer:1. at stake 2. clings to 3.hang on 4. turned ... over 5. referred to ... as7. Each of the verbs and nouns in the following lists occurs in this passage. Choose the noun that you think collocates with each verb and write it in the blank. If you think more than oneAnswer: 1.to open/engage in/start/ a quarrel2.to have/worship a different outlook3.to run/found/start/build/plan/have/engage in a business4.to purchase/run/found/start/build a firm5.to make a decision6.to treasure peace in life7.to provide acclaim8.to face retirement9.to engage in/start/make succession planning10.to worship founder6. T ranslate the following sentences into English.1.虽然他说他为此事做了很多努力,但他的成功至少部分是由于他运气好。

大学体验英语第四单元课后练习和课文翻译

Unit4 Passage A 课后练习Read and think2 Answer the following questions with the information you got from the passage.1 She decided to experience living abroad early in her college years and she actually went to liv e abroad two months after she graduated from college.2 Her classmates looked for permanent jobs in the “real world” but she looked for a temporary job in another country.3 Because she only had a work visa but no job or place to live.She had no one to rely on but to depend entirely on herself.4 She had her first interview the first week and she had three altogether.5 She thought it had many advantages.Firstly she truly got to learn the culture. Secondly,it was an economical way to live and travel in another country.Thirdly,she had the chance to gain valuable working experience and internationalize her resume.She strongly recommended it.Read and complete3 Fill in the blanks with the words or phrases from the passage.Don’t refer back to it until you have finished.1 living abroad;the“real world”2 go and work;interviewing for3 to live abroad;was willing to do anything4 a program;with the interest5 language;opportunities6 graduated from college;traveled throughout7 finding a job;financial resources;paycheck8 found a job in London;very well—known;employers9 accepted;international bank;located10 the best decision;hesitate for a secondLanguage FocusRead and complete4 Fill in the blanks with the words given below.Change the form where necessary.1 undertaken2 had intended3 resources4 inquiries5 investigated6 recommend7 participates8 aspects9 hesitate 10 economical5 Complete the following sentences with words or expressions from the passage. Change the form where necessary.1 running low2 turned out3 participate in4 as a result5 so far6 Rewrite the following sentences,replacing the underlined words with their synonyms you have learned in this unit.1 employment 2 opportunities 3 advantages 4 expenses 5 accommodation(s)Read and translate7 Translate the following sentences into English.1 I have faxed my resume and a cover letter to that company, but I haven’t received a reply yet.2 John will not hesitate for a second to offer help when others are in trouble.3 I have to admit that I desire very much to work or study abroad for some time but I know it is not easy to get a visa.4 It was not until 2 years after he arrived in London that he found/took a job in an international bank.5 After finishing his teaching,Tom traveled throughout China for 2 months before returning home in America.Read and simulate8 Read and compare the English sentences,paying attention to their italicized parts and translate the Chinese sentences by simulating the structure of the English sentences.1 Of the three jobs available/offered,I chose this one because of the pay and the working condition.2 It wasn’t until 6 months after my graduation that I found my first job and went to work in a computer company.3 I was most scared about the next day’s job interview since 1 was not well prepared and I needed t o do more homework /preparation.4 The university I work at is in a beautiful.scenic spot Located two miles from the Xiang River.5 Exercise has many advantages.For one,it helps you to lose weight.Secondly, it helps prevent disease.Thirdly, exercising everyday keeps you fit and strong.Unit4 Passage A课文译文玛塞娜的工作经历进大学不久我就下定决心,在进入“现实世界”前先到国外呆一段。

大学体验英语第四版第二册-7A-Things I Learned from Dad

Unit 7. Passage A. Things I Learned from Dad父亲的教诲Three successful people reveal how fathers shape our destiny.三位成功人士讲述父亲怎样塑造我们的人生Rebecca Lobo: Be Loving充满爱心[1] I knew — even when I was very young — just how much my mom and dad loved each other. Whenever one of them went out, they kissed each other goodbye. My brother, sister and I thought this was gross! But when I get married, I can only hope that I will have found someone who loves me as much as Dad loves Mom. Because there was always so much love in the family, I grew up with an incredible security blanket.自小我就知道,父亲和母亲深深相爱。

只要单独出门,他们总会吻别,我们兄妹几个觉得挺让人难为情的,可结婚时,我却满心希望所找到的这个人,能像父亲爱母亲那样爱着我。

在我家,爱无处不在,我成长的过程充满了安全感。

[2] Mom battled breast cancer when I was in college. Despite his worry, Dad was a pillar of strength for us and especially for her. After her mastectomy, she decided against the added trauma of breast-reconstruction surgery. Mom told me that in their entire marriage Dad never suggested that she even change her hairstyle. Instead he has always t old her how beautiful she is. And that’s why she thinks fighting cancer wasn’t as hard as it could have been. She knew that no matter what, Dad and his love would be there.我上大学时,母亲在与乳腺癌做斗争。

大学体验英语4课后翻译、课文翻译、选词填空

英语复习资料2017年6月8日1AA无名英雄:职业父亲意味着什么?在我们的孪生女儿出生后的第一次“约会”时,我和丈夫一起去看了一部名为《玩具故事》的电影。

我们很喜欢这部片子,但随后我丈夫问道:“父亲在哪儿呢?”起初我还认为因为一个小小的失误而批评一部很吸引人的家庭影片似乎是太偏狭了。

可后来越想越觉得这一疏忽太严重了。

父亲不仅没有出现,他甚至没有被提到——尽管家中有婴儿,说明他不可能离开太长时间。

影片给人的感觉是,父亲出现与否似乎是个极次要的细节,甚至不需要做任何解释。

新闻媒体倾向于把父亲的边缘化,这只是一个例子,它反映了在美国发生的巨大的社会变化。

大卫?布兰肯霍恩在《无父之国》一书中将这种倾向称之为“无需父亲”观念。

职业母亲(我想这应是与无职业母亲相对而言的)奋斗的故事从媒体上无尽无休地轰击着我们。

与此同时,媒体上绝大多数有关父亲的故事又集中表现暴力的丈夫或没出息的父亲。

看起来似乎父亲惟一值得人们提及的时候是因为他们做家务太少而受到指责的时候(我怀疑这一说法的可靠性,因为“家务”的定义中很少包括打扫屋顶的雨水沟、给汽车换机油或其它一些典型地由男人们做的事),或者是在他们去世的时候。

当布兰肯霍恩先生就“顾家的好男人”一词的词义对父亲们进行调查时,许多父亲都回答这一词语只有在葬礼上听到。

这种“无需父亲”综合症的一个例外是家庭全职父亲所受到的媒体的赞扬。

我并非暗指这些家庭全职父亲作出的承诺不值得人们的支持,我只是想指出在实际生效的双重标准:家庭全职父亲受到人们的赞扬,而家庭全职母亲和养家活口的父亲,所得到文化上的认同却很少,甚至完全得不到。

我们用来讨论父亲角色(即没出息的父亲)的话语本身就显示出人们对大多数男人默默无闻而自豪地履行对家庭承担的责任缺乏赏识。

我们几乎从来没听到“职业父亲”这一说法,在人们呼吁应该考虑给予工作者在工作地点上更大的灵活性时,很少有人认为这种呼吁不但适用于女子,同样也适应于男子。

mjt-大学体验英语综合教程4-Unit7课文翻译及课后答案

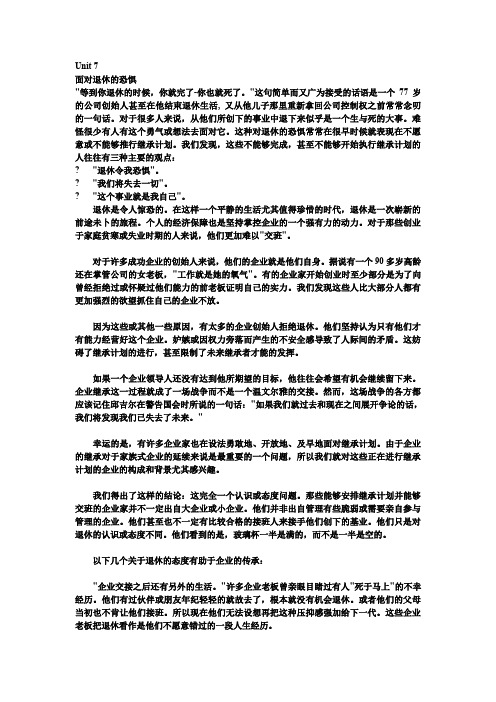

Unit 7面对退休的恐惧"等到你退休的时候,你就完了-你也就死了。

"这句简单而又广为接受的话语是一个77岁的公司创始人甚至在他结束退休生活, 又从他儿子那里重新拿回公司控制权之前常常念叨的一句话。

对于很多人来说,从他们所创下的事业中退下来似乎是一个生与死的大事。

难怪很少有人有这个勇气或想法去面对它。

这种对退休的恐惧常常在很早时候就表现在不愿意或不能够推行继承计划。

我们发现,这些不能够完成,甚至不能够开始执行继承计划的人往往有三种主要的观点:? "退休令我恐惧"。

? "我们将失去一切"。

? "这个事业就是我自己"。

退休是令人惊恐的。

在这样一个平静的生活尤其值得珍惜的时代,退休是一次崭新的前途未卜的旅程。

个人的经济保障也是坚持掌控企业的一个强有力的动力。

对于那些创业于家庭贫寒或失业时期的人来说,他们更加难以"交班"。

对于许多成功企业的创始人来说,他们的企业就是他们自身。

据说有一个90多岁高龄还在掌管公司的女老板,"工作就是她的氧气"。

有的企业家开始创业时至少部分是为了向曾经拒绝过或怀疑过他们能力的前老板证明自己的实力。

我们发现这些人比大部分人都有更加强烈的欲望抓住自己的企业不放。

因为这些或其他一些原因,有太多的企业创始人拒绝退休。

他们坚持认为只有他们才有能力经营好这个企业。

妒嫉或因权力旁落而产生的不安全感导致了人际间的矛盾。

这妨碍了继承计划的进行,甚至限制了未来继承者才能的发挥。

如果一个企业领导人还没有达到他所期望的目标,他往往会希望有机会继续留下来。

企业继承这一过程就成了一场战争而不是一个温文尔雅的交接。

然而,这场战争的各方都应该记住邱吉尔在警告国会时所说的一句话:"如果我们就过去和现在之间展开争论的话,我们将发现我们已失去了未来。

"幸运的是,有许多企业家也在设法勇敢地、开放地、及早地面对继承计划。

大学体验英语综合教程4课文翻译 unit7 PA面对退休的恐惧

面对退休的恐惧"等到你退休的时候,你就完了-你也就死了。

"这句简单而又广为接受的话语是一个77岁的公司创始人甚至在他结束退休生活, 又从他儿子那里重新拿回公司控制权之前常常念叨的一句话。

对于很多人来说,从他们所创下的事业中退下来似乎是一个生与死的大事。

难怪很少有人有这个勇气或想法去面对它。

这种对退休的恐惧常常在很早时候就表现在不愿意或不能够推行继承计划。

我们发现,这些不能够完成,甚至不能够开始执行继承计划的人往往有三种主要的观点:∙"退休令我恐惧"。

∙"我们将失去一切"。

∙"这个事业就是我自己"。

退休是令人惊恐的。

在这样一个平静的生活尤其值得珍惜的时代,退休是一次崭新的前途未卜的旅程。

个人的经济保障也是坚持掌控企业的一个强有力的动力。

对于那些创业于家庭贫寒或失业时期的人来说,他们更加难以"交班"。

对于许多成功企业的创始人来说,他们的企业就是他们自身。

据说有一个90多岁高龄还在掌管公司的女老板,"工作就是她的氧气"。

有的企业家开始创业时至少部分是为了向曾经拒绝过或怀疑过他们能力的前老板证明自己的实力。

我们发现这些人比大部分人都有更加强烈的欲望抓住自己的企业不放。

因为这些或其他一些原因,有太多的企业创始人拒绝退休。

他们坚持认为只有他们才有能力经营好这个企业。

妒嫉或因权力旁落而产生的不安全感导致了人际间的矛盾。

这妨碍了继承计划的进行,甚至限制了未来继承者才能的发挥。

如果一个企业领导人还没有达到他所期望的目标,他往往会希望有机会继续留下来。

企业继承这一过程就成了一场战争而不是一个温文尔雅的交接。

然而,这场战争的各方都应该记住邱吉尔在警告国会时所说的一句话:"如果我们就过去和现在之间展开争论的话,我们将发现我们已失去了未来。

"幸运的是,有许多企业家也在设法勇敢地、开放地、及早地面对继承计划。

大学体验英语综合教程课堂辅导Book 4Unit 7-passage a-词汇充电交际实战

1 utterv. ①make ( a sound or sounds ) with the mouth or voice (以口)发出(声音) ②say or speak 说, 讲。

如:He never uttered a word of protest. 他从来没说一句反对的话.adj. complete; total; absolute 完全的;彻底的;绝对的。

如:She’s an utter stranger to me. 我根本不认识她。

【联想】同根词utterly adv. 完全地,绝对地,彻底地2 no wonder :not surprising. 如:No wonder you were late! 难怪你来晚了!3 inclinationn. ①[C, U] feeling that makes sb. want to behave in a particular way; disposition 倾向;意向;意愿。

如:I have little inclination to listen to you all evening. 我可不愿意一晚上都听你说话。

She is not free to follow her own inclination in the matter of marriage. 她的婚姻不能自主。

②[C] event that regularly happens; tendency 经常发生的事;趋向;趋势。

如:He has an inclination to stoutness/to be fat. 他有发福/ 发胖的趋势。

【联想】incline v. 向某物的方向倾斜;|inclined adj. 想以某种方式行事;准备做事4 successionn. ①[C] number of things or people coming one after the other in time or order; series 一连串的事物;接二连三的人, 一系列。

大学体验英语4课文翻译及课后翻译

一、课后翻译Unit 11.随着职务的提升,他担负的责任也更大了。

(take on)With his promotion ,he has taken on greater responsibilities.2. 他感到他再没有必要对约翰承担这样的责任。

(make a commitment)He felt he did not have to make such a commitmentto John any more .3. 闲暇时玛丽喜欢外出购物,与她相反,露茜却喜欢呆在家里看书。

(as opposed to)Mary likes go to shopping in her spare time ,as opposed to Lucy, who prefers to stay at home reading.4. 充其量可以说他有抱负,用最糟糕的话来说,他是一个没有良心(conscience)或没有资格的权力追求者。

(at best, at worst)At best he's ambitious,at worst a power-seeker without conscience or qualifications .5. 我们已尽全力说服他,但是却毫无进展。

(strive,make no headway)We have striven to the full to convince him,but we have made no headway.Unit 21. 要是他适合当校长,那么哪个学生都可以当。

(no more...than)He is no more fit to be a headmaster than any schoolboy would be.2. 至于她的父亲,她不敢肯定是否会接收她和她的小孩。

(as for)As for her father, she is not sure whether he will accept her and her baby.3. 晚睡会损害健康而早睡早起有益于健康。

大学体验英语综合教程课堂辅导Book 4Unit 7-passage a-难点精讲

1. The inability to“let go”is even more difficult for those who founded their businesses at a time of unemployment or family poverty:“Let go”means to follow the law of nature, to accept reality. The sentence means that those who have experienced unemployment or poverty would find it more difficult to accept the idea of retirement from their position and their subsequent loss of power.“Let go”在这里指的是遵循自然法规, 接受现实. 这句话的意思是对于那些曾经有过失业和贫穷经历的人来说, 从他们的职位上退休下来是很难接受的一件事。

2. If we open a quarrel between the past and the present, we shall find that we have lost the future. 这句著名的引言第一次出现在丘吉尔为下议院所做的一次演讲中。

“Their finest hour”1940年的6月18日。

当时, 德国军队冲破了法国的防线, 并且法国军队和英国的远征部队被迫撤退到敦刻尔克。

要从下议院获得更多的支持来激发英国的士兵到前线到与敌人的战斗, 丘吉尔警告说如果人们对于它的必要性继续保持犹豫,那国家也许就没有了未来。

3. For them, the glass is half full, not half empty. 对于他们来说,他们看到的是,玻璃杯一半是满的,而不是一半是空的。

大学体验英语综合教程4课文翻译

Unit1 PA无名英雄:职业父亲意味着什么?在我们的孪生女儿出生后的第一次"约会”时,我和丈夫一起去看了一部名为《玩具故事》的电影。

我们很喜欢这部片子,但随后我丈夫问道:"父亲在哪儿呢?”起初我还认为因为一个小小的失误而批评一部很吸引人的家庭影片似乎是太偏狭了。

可后来越想越觉得这一疏忽太严重了。

父亲不仅没有出现,他甚至没有被提到——尽管家中有婴儿,说明他不可能离开太长时间。

影片给人的感觉是,父亲出现与否似乎是个极次要的细节,甚至不需要做任何解释。

新闻媒体倾向于把父亲的边缘化,这只是一个例子,它反映了在美国发生的巨大的社会变化。

大卫?布兰肯霍恩在《无父之国》一书中将这种倾向称之为"无需父亲”观念。

职业母亲(我想这应是与无职业母亲相对而言的)奋斗的故事从媒体上无尽无休地轰击着我们。

与此同时,媒体上绝大多数有关父亲的故事又集中表现暴力的丈夫或没出息的父亲。

看起来似乎父亲惟一值得人们提及的时候是因为他们做家务太少而受到指责的时候(我怀疑这一说法的可靠性,因为"家务”的定义中很少包括打扫屋顶的雨水沟、给汽车换机油或其它一些典型地由男人们做的事),或者是在他们去世的时候。

当布兰肯霍恩先生就"顾家的好男人”一词的词义对父亲们进行调查时,许多父亲都回答这一词语只有在葬礼上听到。

这种"无需父亲”综合症的一个例外是家庭全职父亲所受到的媒体的赞扬。

我并非暗指这些家庭全职父亲作出的承诺不值得人们的支持,我只是想指出在实际生效的双重标准:家庭全职父亲受到人们的赞扬,而家庭全职母亲和养家活口的父亲,所得到文化上的认同却很少,甚至完全得不到。

我们用来讨论父亲角色(即没出息的父亲)的话语本身就显示出人们对大多数男人默默无闻而自豪地履行对家庭承担的责任缺乏赏识。

我们几乎从来没听到"职业父亲”这一说法,在人们呼吁应该考虑给予工作者在工作地点上更大的灵活性时,很少有人认为这种呼吁不但适用于女子,同样也适应于男子。

大学体验英语4课文翻译及课后翻译

一、课后翻译Unit 11.随着职务的提升,他担负的责任也更大了。

(take on)With his promotion ,he has taken on greater responsibilities.2. 他感到他再没有必要对约翰承担这样的责任。

(make a commitment)He felt he did not have to make such a commitmentto John any more .3. 闲暇时玛丽喜欢外出购物,与她相反,露茜却喜欢呆在家里看书。

(as opposed to)Mary likes go to shopping in her spare time ,as opposed to Lucy, who prefers to stay at home reading.4. 充其量可以说他有抱负,用最糟糕的话来说,他是一个没有良心(conscience)或没有资格的权力追求者。

(at best, at worst)At best he's ambitious,at worst a power-seeker without conscience or qualifications .5. 我们已尽全力说服他,但是却毫无进展。

(strive,make no headway)We have striven to the full to convince him,but we have made no headway.Unit 21. 要是他适合当校长,那么哪个学生都可以当。

(no more...than)He is no more fit to be a headmaster than any schoolboy would be.2. 至于她的父亲,她不敢肯定是否会接收她和她的小孩。

(as for)As for her father, she is not sure whether he will accept her and her baby.3. 晚睡会损害健康而早睡早起有益于健康。

大学体验英语听说教程听力原文【第四册Unit 7】 Language

Unit Seven LanguageListening Task 1Jessica Bucknam shouts “tiao!” and her fourth-grade students jump. “Dun!” she commands, and they crouch. They giggle as the commands keep coming in Mandarin Chinese. Most of the kids have studied Chinese since they were in kindergarten.They are part of a Chinese-immersion program at Woodstock Elementary School, in Portland, Oregon. Bucknam, who is from China, introduces her students to approximately 150 new Chinese characters each year. Students read stories, sing songs and learn math and science, all in Chinese. Half of the students at the school are enrolled in the program. They can continue studying Chinese in middle and high school. The goal: to speak like natives.About 24,000 American students are currently learning Chinese. Most are in high school. But the number of younger students is growing in response to China’s emergence as a global superpower. The U.S government is helping to pay for language instruction. Recently, the Defense Department gave Oregon schools $700,000 for classes like Bucknam’s. The Senate is considering giving $1.3 billion for Chinese classes in public schools.“China has become a stong partner of the United States,”says Mary Patterson, Woodstock’s principal. “Children who learn Chinese at a young age will have more opportunities for jobs in the future.” Isabel Weiss, 9, isn't thinking about the future. She thinks learning Chinese is fun. “When you hear people speaking in Chinese, you know what they’re saying,” she says. “And they don’t know that you know.”Want to learn Chinese? You have to memorize 3,500 characters to really know it all! Start with these Chinese characters and their pronunciations.Listening Task 2An idiom is an expression whose meaning cannot be deduced from the literal definitions and the arrangement of its parts, but refers instead to a figurative meaning that is known only through conventional use. In the English expression to kick the bucket, a listener knowing only the meaning of kick and bucket would be unable to deduce the expression’s actual meaning, which is to die. Although kick the bucket can refer literally to the act of striking a bucket with a foot, native speakers rarely use it that way.Idioms hence tend to confuse those not already familiar with them; students of a new language must learn its idiomatic expressions the way they learn its other vocabulary. In fact many natural language words have idiomatic origins, but have been sufficiently assimilated so that their figurative senses have been lost.Interestingly, many Chinese characters are likewise idiomatic constructs, as their meanings are more often not traceable to a literal meaning of their assembled parts, or radicals. Because all characters are composed from a relatively small base of about 214 radicals, their assembled meanings follow several different modes of interpretation –from the pictographic to the metaphorical to those whose original meaning has been lost in history.Real world listeningQ: Why are some idioms so difficult to be understood outside of the local culture?A: Idioms are, in essence, often colloquial metaphors –terms which requires some foundational knowledge, information, or experience, to use only within a culture where parties must have common reference. As cultures are typically localized, idioms are more often not useful for communication outside of that local context.Q: Are all idioms translatable across languages?A: Not all idioms are translatable. But the most common idioms can have deep roots, traceable across many languages. To have blood on one’s hands is a familiar example, whose meaning is obvious. These idioms can be more universally used than others, and they can be easily translated, or their metaphorical meaning can be more easily deduced. Many have translations in other languages, and tend to become international.Q: How are idioms different from others in vocabulary?A: First, the meaning of an idiom is not a straightforward composition of the meaning of its parts. For example, the meaning of kick the bucket has nothing to do with kicking buckets. Second, one cannot substitute a word in an idiom with a related word. For example, we can not say kick the pail instead of kick the bucket although bucket and pail are synonyms. Third, one can not modify an idiom or apply syntactic transformations. For example, John kicked the green bucket or the bucket was kicked has nothing to do with dying.。

大学体验英语综合教程4_课文原文

Unit1. The Unsung Heroes: What About Working DadsOn our first "date" after our twin daughters were born, my husband and I went to see the movie Toy Story. We enjoyed it, but afterward my husband asked, "Where was the dad" At first, it seemed petty to criticize an entertaining family movie because of one small point. The more I thought about it, however, the more glaring an omission it seemed. Not only was dad not around, he wasn't even mentioned - despite the fact that there was a baby in the family, so dad couldn't have been that long gone. It was as if the presence- or absence - of a father is a minor detail, not even requiring an explanation.This is only one example of the media trend toward marginalizing fathers, which mirrors enormous social changes in the United States. David Blankenhorn, in his book Fatherless America, refers to this trend as the "unnecessary father" concept.We are bombarded by stories about the struggles of working mothers (as opposed to non-working mothers, I suppose). Meanwhile, a high proportion of media stories about fathers focus on abusive husbands or deadbeat dads. It seems that the only time fathers merit attention is when they are criticized for not helping enough with the housework (a claim that I find dubious anyway, because the definition of "housework" rarely includes cleaning the gutters, changing the oil in the car or other jobs typically done by men) or when they die. When Mr. Blankenhorn surveyed fathers about the meaning of the term "good family man," many responded that it was a phrase they only heard at funerals. One exception to the "unnecessary father" syndrome is the glowing media attention that at-home dads have received. I do not mean to imply that at-home dads do not deserve support for making this commitment. I only mean to point out the double standard at work when at-home dads are applauded while at-home mothers and breadwinner fathers are given little, if any, cultural recognition.The very language we use to discuss men's roles ., deadbeat dads) shows a lack of appreciation for the majority of men who quietly yet proudly fulfill their family responsibilities. We almost never hear the term "working father," and it is rare that calls for more workplace flexibility are considered to be for men as much as for women. Our society acts as if family obligations are not as important to fathers as they are to mothers - as if career satisfaction is what a man's life is all about.Even more insulting is the recent media trend of regarding at-home wives as "status symbols" - like an expensive car - flaunted by the supposedly few men who can afford such a luxury. The implication is that men with at-home wives have it easier than those whose wives work outside the home because they have the "luxury" of a full-time housekeeper. In reality, however, the men who are the sole wage earners for their families suffer a lot of stresses. The loss of a job - or even the threat of that happening - is obviously much more difficult when that job is the sole source of income for a family. By the same token, sole wage earners have less flexibility when it comes to leaving unsatisfying careers because of the loss of income such a job change entails. In addition, many husbands work overtime or second jobs to make more needed money for their families. For these men, it is the family that the job supports that makes it all worthwhile. It is the belief that having a mother at home is important to the children, which makes so many men gladly take on the burden of being a sole wage earner.Today, there is widespread agreement among researchers that the absence of fathers from households causes serious problems for children and, consequently, for society at large. Yet, rather than holding up "ordinary" fathers as positive role models for the dads of tomorrow, too often societyhas thrown up its hands and decided that traditional fatherhood is at best obsolete and at worst dangerously reactionary. This has left many men questioning the value of their role as fathers.As a society, we need to realize that fathers are just as important to children as mothers are - not only for financial support, but for emotional support, education and discipline as well. It is not enough for us merely to recognize that fatherlessness is a problem - to stand beside the grave and mourn the loss of the "good family man" and then try to find someone to replace him (ask anyone who has lost a father though death if that is possible). We must acknowledge how we have devalued fatherhood and work to show men how necessary, how important they are in their children's lives.Those fathers who strive to be good family men by being there every day to love and support their families - those unsung heroes - need our recognition and our thanks for all they do. Because they deserve it.Unit2. Why Digital Culture Is Good for YouThe news media, along with social and behavioral scientists, have recently sent out a multitude of warnings about the many dangers that await us out there in cyberspace. The truth of the matter is that the Web is no more inherently dangerous than anything else in the world. It is not someamorphous entity capable of inflicting harmful outcomes on all who enter. In fact, in and of itself, the Web is fairly harmless. It has no special power to overtake its users and alter their very existence. Like the old tale that the vampire cannot harm you unless you invite it to cross your threshold, the Internet cannot corrupt without being invited. And, with the exception of children and the weak-willed, it cannot create what does not already exist...(1) Like alcohol, the Web simply magnifies what is already there: Experts are concerned that the masking that goes on online poses a danger for everyone who is a part of the Digital Culture. Before we know it, the experts tell us, we will all use fake identities, become fragmented, and will no longer be sure of just who we are. Wrong. The only people who feel compelled to mask, and otherwise misrepresent themselves online are the same people who are mysterious and unfrank in "real life"...the Net just gives them one more tool to practice their deceit.As for the rest of us, getting taken in by these people is a low probability. We know who these folks are in the "real world". The Internet does not "cause" people to disguise as something they are not. As for the Digital Culture getting cheated by these dishonest folks, well, there are just as many "cues" online to decipher deception as there are in the "real world". The competent WebHead can recognize many red flags given off by the online behavior of others. Oftentimes the intentions of fellow users is crystal clear, especially over time.When someone is trying to deceive us online, inconsistencies, the essence that they are trying "too hard" or are just plain unbelievable, often come through loud and clear. Likewise, just like in the "real world", a host of other unacceptable tendencies can be readily recognized online. Narcissism (it's all about "meeeee"), those people who have nothing but negativity or unpleasant things to say about others, and those who feel compelled to undermine others and who think they must blow out the other guys' candles in order for their own to shine can be spotted a cybermile away.(2) The Web can bring out the best in people: Gregarious, frank folks in "real life" usually carry these same traits over to their online life. Most are just as fun-loving online if not more so, as they are at a party, at work, or at the local bar. Though admittedly, some are not quite as much fun to be around without a stiff drink.Shy folks have a "safer" environment online than in the "real world" and can learn to express themselves more freely on the Net (you've never seen anyone stutter on e-mail, have you) allowing them to gain confidence and communication skills that can eventually spill over into other aspects of their lives. Helpful people in "real life" are often just as willing to come to someone's assistance online as anywhere else.(3) People are judged differently on the Web: On the Internet people are judged by their personality, beliefs and online actions, NOT by their physical appearance. This is good. It not only gives ugly folks an aid, but causes Beautiful People to have to say something worth listening to in order to get attention.(4) People open up more: Many people are opening up a whole lot more these days since they are not required to use their real name and provide their real identity in the Internet.(5) We're connected: Members of the Digital Culture know full well that there is a wealth of important information and life-changing opportunities out there in cyberspace. The Web has opened doors for many of us that otherwise would never have been an option. Research possibilities and networking are just two such opportunities.(6) We Learn the Power of Words and to be Better Listeners: With no facial expressions, body language, or physical appearance to distract us, members of the Digital Culture have learned thepower of words ... both their own, and others'. We know very well how a simple string of words can harm, hurt and offend, or how they can offer humor, help, support and encouragement. Most experienced members of the online culture have learned to become wordsmiths, carefully crafting the words they use to convey exactly what they mean so as not to be misunderstood.Many of us have also learned to become far better listeners thanks to the Internet. Not only do we choose our words more carefully but we (especially those who communicate via email as opposed to chat rooms) are forced to wait until the other person finishes before we can speak or respond.Unit3. Big Myths About Copyright"If it doesn't have a copyright notice, it's not copyrighted." This was true in the past, but today almost all major nations follow the Berne copyright convention. For example, in the USA, almost everything created privately and originally after April 1, 1989 is copyrighted and protected whether it has anotice or not. The default you should assume for other people's works is that they are copyrighted and may not be copied unless you know otherwise. There are some old works that lost protection without notice, but frankly you should not risk it unless you know for sure.2) "If I don't charge for it, it's not a violation." False. Whether you charge can affect the damages awarded in court, but that's the main difference under the law. It's still a violation if you give it away - and there can still be serious damages if you hurt the commercial value of the property. There is an exception for personal copying of music, which is not a violation, though courts seem to have said that doesn't include wide-scale anonymous personal copying as Napster. If the work has no commercial value, the violation is mostly technical and is unlikely to result in legal action.3) "If it's posted to Usenet it's in the public domain." False. Nothing modern is in the public domain anymore unless the owner explicitly puts it in the public domain. Explicitly, as you have a note from the author/owner saying, "I grant this to the public domain."4) "My posting was just fair use!" The "fair use" exemption to .) copyright law was created to allow things such as commentary, parody, news reporting, research and education about copyrighted works without the permission of the author. That's important so that copyright law doesn't block your freedom to express your own works. Intent and damage to the commercial value of the work are important considerations. Are you reproducing an article from the New York Times because you couldn't find time to write your own story, or didn't want your readers to have to pay for the New York Times web site They aren't "fair use". Fair use is usually a short excerpt.5) "If you don't defend your copyright you lose it." - "Somebody has that name copyrighted!" False. Copyright is effectively never lost these days, unless explicitly given away. You also can't "copyright a name" or anything short like that, such as almost all titles. You may be thinking of trademarks, which apply to names, and can be weakened or lost if not defended. Like an "Apple" computer. Apple Computer "owns" that word applied to computers, even though it is also an ordinary word. Apple Records owns it when applied to music. Neither owns the word on its own, only in context, and owning a mark doesn't mean complete control.6)"If I make up my own stories, but base them on another work, my new work belongs to me." False. . Copyright law is quite explicit that the making of what are called "derivative works" - works based on or derived from another copyrighted work - is the exclusive province of the owner of the original work. This is true even though the making of these new works is a highly creative process. If you write a story using settings or characters from somebody else's work, you need that author's permission. 7)"They can't get me, defendants in court have powerful rights!" Copyright law is mostly civil law. If you violate copyright you would not be charged with a crime, but usually get sued.8) "Oh, so copyright violation isn't a crime or anything" Actually, recently in the USA commercial copyrightviolation involving more than 10 copies and value over $2500 was made a felony. So watch out. On the other hand, this is a fairly new, untested statute. In one case an operator of a pirate BBS that didn't charge was acquitted because he didn't charge, but congress amended the law to cover that. 9) "It doesn't hurt anybody - in fact it's free advertising." It's up to the owners to decide if they want the free ads or not. If they want them, they will be sure to contact you. Don't rationalize whether it hurts the owners or not, ask them. Usually that's not too hard to do. Even if you can't think of how the author or owner gets hurt, think about the fact that piracy on the net hurts everybody who wantsa chance to use this wonderful new technology to do more than read other people's flamewars.10) "They e-mailed me a copy, so I can post it." To have a copy is not to have the copyright. All theE-mail you write is copyrighted. However, E-mail is not unless previously agreed. So you can certainly report on what E-mail you are sent, and reveal what it says. You can even quote parts of it to demonstrate. Frankly, somebody who sues over an ordinary message would almost surely get no damages, because the message has no commercial value, but if you want to stay strictly in the law, you should ask first. On the other hand, don't go nuts if somebody posts E-mail you sent them. If it was an ordinary non-secret personal letter of minimal commercial value with no copyright notice (like % of all E-mail), you probably won't get any damages if you sue them.Unit4The study of literature is not only civilized and civilizing —encompassing, as it does, philosophy, religion, the history of events and the history of ideas — but popular and practical. One-sixth of all those who receive bachelor’s degrees from the College of Arts and Sciences are English majors. These graduates qualify for a surprising range of jobs. Their experience puts the lie to the popular superstition that English majors must choose between journalism and teaching: in fact, English majors also receive excellent preparation for future careers in law, medicine, business, and governmentservice.Undergraduates looking forward to law school or medical school are often advised to follow a strict regimen of courses considered directly relevant to their career choices. Future law-school students are advised to take courses in political science, history, accounting, business administration — even human anatomy, and marriage and family life. Future medical school students are steered into multiple science courses —actually far more science courses than they need for entrance into medical school. Surprisingly, many law schools and medical schools indicate that such specialized preparation is not only unnecessary, but undesirable. There are no "pre-law" courses: the best preparation for law school — and for the practice of law — is that preparation which makes a student capable of critical thinking; of clear, logical self-expression; of sensitive analysis of the motives, the actions, and the thoughts of other human beings. These are skills which the study of English is designed to teach.Entrance into law school, moreover, generally requires a bachelor’s degree from an accredited institution, a minimum grade point average, and an acceptable score on the Law School Admission Test This test has three parts. The first evaluates skills in reading comprehension, in figure classification, and in the evaluation of written material. The second part of the test evaluates control of English grammar and usage, ability to organize written materials, and competence to edit. The third part evaluates the student’s general knowledge of literature, art, music, and the natural and social sciences. Clearly an undergraduate major in English is strong preparation for theAs for medical schools, the main requirement for admission is only thirty-two hours of science courses. This requirement is certainly no impediment to a major in English. Moreover many medical schools require a minimum score on the Medical College Admissions Test, another test which offers an advantage to the well-rounded liberal arts student. The evaluates four areas of competence: skill with synonyms, antonyms, and word association; knowledge of basic mathematics from fractions through solid geometry; general knowledge of literature, philosophy, psychology, music, art, and the social sciences; and familiarity with those fundamentals of biology, chemistry, and physics taught in high school and in introductory college courses. The English major with a solid, basic grounding in science is well prepared for this test and for medical school, where his or her skills in reading, analysis, interpretation, and precise communication will equip him or her to excel. The study and practice of medicine can only benefit from the insights into human behavior provided by the study of literature. Such insights are obviously also valuable to the student who plans a career in commerce. Such students should consider the advantages of an English major with an emphasis in business: this program is designed to provide a liberal education, as well as to direct preparation for a business career. The need for such a program is clear: graduates with merely technical qualifications are finding jobs in business, but often failing to hold them. Both the Wall Street Journal and the Journal of College Placement have reported that increasing numbers of graduates from reputable business schools find themselves drifting from one job or firm to another, unable to hold a position for longer than twelve months. Employers complain that these apparently promising young men and women are simply not competent communicators: because they are not sufficiently literate, they cannot absorb managerial training; they cannot make effective oral presentations; they cannot report progress or problems in their writing; they cannot direct other workers. Skill in analysis and communication is the essence of management.Consequently the English major with an emphasis in business is particularly well prepared for a future in business administration. Nearly four hundred companies in fields ranging from banking andinsurance to communications to manufacturing were asked whether they hired college graduates with degrees in English, even when those graduates lacked special training in the industry: Eighty-five percent of the companies said that they did. College graduates with degrees in English are working successfully in marketing, in systems engineering, in personnel management, in sales, in programming, in project design, and in labor relations.English majors are also at work in the thousand occupations provided by government at all levels. Consider, for example, the federal government—by a very wide margin, America’s biggest employer. In organizations ranging from the Marine Corps to the Bureau of Mines, from the Commerce Department to the National Park Service, the federal government employs a work force of nearly three million men and women. English majors may qualify for many of these jobs. Recently, 51 federal agencies were asked the same question: whether they hired college graduates with English degrees but without special job training, 88 percent of these federal employers said yes. The list of federal positions for which English majors may qualify ranges from Claims Examiner to Foreign Service Officer to Highway Safety Management Specialist. Again, those who seek positions of high reward and responsibility may be asked to take a test —the federal government uses the Professional and Administrative Career Examination, or to evaluate applicants for about 10,000 jobs each year — and again, the test focuses on language skills: comprehension, analysis, interpretation, the ability to see logical relationships between ideas, and the ability to solve problems expressed in words. Not surprisingly, competent English majors often receive very high scores on theIn short, a major in English is neither restricting nor impractical: the study of English is excellent preparation for professional life.Unit5. The Moral AdvantageHow to Succeed in Business by Doing the Right ThingAs for the moral advantage in business, of all places, everyone knows a modicum of ethics is called for in any business - you can't cheat your customers forever and get away with it. But wouldn't it be more advantageous if you actually could get away with it Profits would soar out of sight! Then you would really have an advantage, or so the thinking might go.The notion of seeking the moral advantage is a new way of thinking about ethics and virtue in business, an approach that does not accept the need for trade-offs between ambition and conscience. Far from obstructing the drive for success, a sense of moral purpose can help individuals and companies achieve at the highest - and most profitable - levels.Cynicism dominates our attitudes about what it takes to succeed in business. A common way of thinking about morality in business goes something like this:Ethical conduct is an unpleasant medicine that society forces down business people's throats to protect the public interest from business avarice.Morality gets in the way of the cold, hard actions truly ambitious Skepticism people must take to reach their goals.Moneymaking is inevitably tainted by greed, deceit, and exploitation.The quest for profits stands in opposition to everything that is moral, fair, decent, and charitable. Skepticism about moneymaking goes back a long way. The Bible warns that it's harder for a rich man to enter the kingdom of heaven than for a camel to pass through the eye of a needle. "Behind every great fortune," wrote French novelist Honoréde Balzac in the 1800s, "lies a great crime." British author G. K. Chesterton sounded the same theme in the early 20th century, noting that a businessman "is the only man who is forever apologizing for his occupation."The contemporary media often characterize business as nothing more than a self-serving exercise in greed, carried out in as corrupt and ruthless a manner as possible. In television and movies, moneymaking in business is tainted by avarice, exploitation, or downright villainy. The unflattering portrayals have become even more pointed over time. In 1969, the businessman in Philip Roth's Goodbye, Columbus advises the story's protagonist, "To get by in business, you've got to be a bit of a thief." He seems like a benignly wise, figure compared with Wall Street's 1980s icon, Gordon Gekko, whose immortal words were "Greed is good."Yet some important observers of business see things differently. Widely read gurus such as Stephen Covey and Tom Peters point to the practical utility of moral virtues such as compassion, responsibility, fairness, and honesty. They suggest that virtue is an essential ingredient in the recipe for success, and that moral standards are not merely commendable choices but necessary components of a thriving business career. This is a frequent theme in commencement addresses and other personal testimonials: Virtuous behavior advances a career in the long run by building trust and reputation, whereas ethical shortcomings eventually derail careers. The humorist Dorothy Parker captured this idea in one of her signature quips: "Time wounds all heels.So who's right --- those who believe that morality and business are mutually exclusive, or those who believe they reinforce one another Do nice guys finish last, or are those who advocate doing well by doing good the real winners Is the business world a den of thievery or a haven for upstanding citizens With colleagues Howard Gardner at Harvard University and Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi at Claremont Graduate University, I've examined this question by interviewing 40 top business leaders, such as McDonald's CEO Jack Greenberg and the late Washington Post publisher Katharine Graham, between 1998 and 2000 as part of our joint "Project on Good Work." We found that a strong sense of moral purpose not only promotes a business career but also provides a telling advantage in the quest to build a thriving enterprise. In fact, a sense of moral purpose stands at the center of all successful business innovations. Far from being a constraining force that merely keeps people honest and out of trouble, morality creates a fertile source of business motivation, inspiration, and innovation.This is different from the view of morality you'll encounter in a typical business-ethics course. It's so different that I now speak about moralities, in the plural, when discussing the role of virtue and ethics in business. Morality in business has three distinct faces, each playing its own special role in ensuring business success.Unit6. Is It Healthy to Be a Football SupporterWhy Fans Know the ScoreDie-hard football fans hit the heights when their team wins and reaches the depths of despair when they lose. Scientific studies show the love affair with a team may be as emotionally intense as the real thing, and that team clashes have gladiatorial power.What's going on Why do fervent fans have hormonal surges and other psychological changes while watching games Why does fans' self-esteem soar with victory and plummet in defeat, sometimes affecting their lives long afterwards Why do people feel so drawn to form such deep ties to teams Is avidly rooting for a team good or bad for your health You may find the answers surprising.THE FAN'S PERSONALITYPsychologists often portray die-hard fans as lonely misfits searching for self-esteem by identifying with a team,2 but a study suggests the opposite. It reveals that football fans suffer fewer bouts of。

大学体验英语综合教程4_课文原文