Eugene_(Gladstone)_O’_Neill

long_day's_journey_into_night

James Tyrone

The sixty-five year old family patriarch, James Tyrone is a financially successful and handsome actor His resulting fear of poverty has turned him into a man obsessed with money and owning property, always looking for bargains, even at the expense of his family’s health.

Author Biography

4 sent to a sanitarium because of tuberculosis in the winter of 1912-13, and had leisure to read and meditate 5 joined 47 Workshop at Harvard to learn to writer better in 1914

America’s greatest playwright American Shakespeare 4 times Pulitzer Prize winner(1920; 1922; 1928; 1957) one time won the Nobel Prize (1936) Beyond the Horizon --the Pulitzer Prize in 1920 (reality destroy people’s ideal life) Anna Christie –the Pulitzer Prize in 1922 the Nobel Prize in 1936 for the above two Long Day’s Journey into Night --the Pulitzer Prize in 1957

Eugene Glastone O'Neill(1888-1953) 定稿

Eugene Glastone O’Neill (1888-1953) 尤金·奥尼尔1. Life and CareerA great playwright, a tragic life•Son of a traveling actor•One year at Princeton•Life as a seaman•1912, TB, start of career as a playwright•1920, first full-length play put on Broadway•1936, Nobel Prize, 4 Pulitzer Prizes (1920,1922,1928,1957)•Unhappy marriages, suicide of oldest son, drug addiction & mental illness of younger son, daughter’s marriage, Parkinson’s disease2.General EvaluationEugene O’Neill was America’s greatest playwright.The first American dramatist to ever receive the Nobel Prize for literature (1936).Winning Pulitzer Prizes for four of his plays: Beyond the Horizon (1920); Anne Christie (1922); Strange Interlude (1928); and Long Day’s Journey into Night (1957).“Founder of the American drama,” and “the American Shakespeare” in the history of American drama.3.Three Periods as a Playwright⏹Early realist plays : utilize his own experiences, especially as a seaman⏹expressionistic plays : influenced by the ideas of philosopher Freidrich Nietzsche,psychologists Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung, and Swedish playwright August Strindberg.(rejected realism in this period)⏹Final period :(returned to realism ) depend on his life experiences for their story linesand themes.ment on O’NeillO’Neill was no doubt the greatest American dramatist of the first half of the 20th century and a tireless experimentalist in dramatic art.1.O’Neill was a tireless experimentalist in dramatic art. He took drama away f rom the oldtraditions of the last century and rooted it deeply in life. He successfully introduced the European theatrical trends of realism, naturalism, and expressionism to the American stage as devices to express his comprehensive interest in modern life and humanity. He introduced the realistic or even the naturalistic aspect of life into the American theater.2.He was the first playwright to explore serious themes in the theatre and to carry out hiscontinual, vigorous, courageous experiments with theatrical conventions. His plays have been translated and staged all over the world.3.He won Pulitzer Prize four times (1920, 1922, 1928, 1956) and the Nobel Prize in 1936for his achievements in plays.4.As the nation’s first playwright with 47 published plays, he did a great deal to establishthe modes of the modern theatre in the country.5.O’Neill’s ceaseless experimentation enriched American drama and influenced laterplaywrights as Tennessee Williams and Edward Albee.。

名人遭到苦难的例子

名人遭到苦难的例子

很多名人在他们辉煌的生涯背后,也曾遭受过苦难和不幸的经历。

以下是一些名人遭受苦难的例子。

1. 海伦·凯勒(Helen Keller):海伦·凯勒是一位美国作家和社会活动家,也是盲聋教育的先驱者。

然而,在她2岁时,她感染了一种罕见的疾病,导致她失去了视力和听力。

尽管如此,她努力克服困境,学会了使用手语和布拉尔字母,最终成为一位灵感和希望的象征。

2. 尤金·奥尼尔(Eugene O'Neill):尤金·奥尼尔是美国著名的戏剧家,他被认为是现代美国戏剧的奠基人之一。

然而,他的生活却充满了苦难和悲剧。

他曾经酗酒、患有抑郁症,并在一次自杀未遂后,被诊断出患有帕金森氏症。

尽管他的生活充满了黑暗,但他通过他的作品传递出了许多深刻的思考和情感。

3. 安妮·弗兰克(Anne Frank):安妮·弗兰克是一位犹太裔德国女孩,她因其在二战期间写的《安妮日记》而闻名于世。

她的家庭在纳粹统治下被迫躲藏起来,直到被发现并送往集中营。

尽管她在集中营中经历了种种苦难,包括饥饿和恐惧,但她通过她的日记表达了对未来的希望和对人性的信任。

这些例子表明,即使是成功和名望背后,也可能隐藏着付出和苦难。

这些名人以他们的勇气和积极的态度,战胜了困难,并成为激励人心的灵感来源。

他们的故事提醒着我们,无论我们在生活中遇到什么困境,都应该坚持勇往直前。

Eugene Glastone ONeill

Eugene Glastone O’Neill(尤金·奥尼尔,1888-1953)作品选读..............................................................................Desire Under the ElmsCharacters: Ephraim Cabot; Simeon, Peter, Eben (Cabot‟s sons); Abbie Putnam (Cabot‟s young wife); A Sheriff.SCENE IV1[About an hour later. Same as Scene III. Shows the kitchen and Cabot’s bedroom. It is after dawn. The sky is brilliant with the sunrise. In the kitchen, Abbie sits at the table, her body limp and exhausted, her head bowed down over her arms, her face hidden. Upstairs, Cabot is still asleep but awakens with a start2. He looks toward the window and gives a snort3of surprise and irritation--throws back the covers and begins hurriedly pulling on his clothes. Without looking behind him, he begins talking to Abbie, whom he supposes beside him.]CABOT: Thunder …n‟ lightnin‟4, Abbie! I hain‟t slept this late in fifty year! Looks‟s if the sun was full riz a‟most. Must‟ve been the dancin‟ an‟ likker. Must be gittin‟ old. I hope Eben‟s t‟ wuk.Ye might‟ve tuk the trouble t‟ rouse me, Abbie. (He turns—sees no one there—surprised) Waal—whar air she? Gittin‟vittles, I calc‟late. (He tiptoes to the cradle and peers down—prou dly) Mornin‟, sonny. Putty‟s a picter! Sleepin‟ sound. He don‟t beller all night like most o‟ ‟em. (He goes quietly out the door in rear—a few moments later enters kitchen—sees Abbie—with satisfaction) So thar ye be. Ye got any vittles5cooked?ABBIE: (without moving) No.CABOT: (coming to her, almost sympathetically) Ye feelin‟ sick?ABBIE: No.CABOT: (pats her on shoulder. She shudders.) Ye‟d best lie down a spell6. (half jocularly) Yer son‟ll be needin‟ ye soon. He‟d ought t‟ wake up with a gnashin‟7appetite, the sound way he‟s sleepin‟.ABBIE: (shudders—then in a dead voice) He hain‟t never goin‟ t‟ wake up.CABOT: (jokingly) Takes after me this mornin‟. I hain‟t slept so late in. . . .ABBIE: He‟s dead.CABOT: (stares at her—bewilderedly8) What. . . .ABBIE: I killed him.CABOT: (stepping back from her—aghast) Air ye drunk—‟r crazy—‟r . . . !ABBIE: (suddenly lifts her head and turns on him—wildly) I killed him, I tell ye! I smothered him.Go up an‟ see if ye don‟t b‟lieve me! (Cabot stares at her a second, then bolts out the rear1scene n.场面;情景;一幕2with a start 吓一跳地;突然一下子3snort vi. 轻蔑或愤怒地发出哼声;喷出4t hunder ‘n’ lightnin’:thunder and lightning 电闪雷鸣5vittles n.食物6spell n. 一段时间7gnash v.(因情绪激动)咬或磨(牙)8bewildered adj. 困惑的;不知所措的;弄糊涂的door, can be heard bounding up the stairs, and rushes into the bedroom and over to the cradle.Abbie has sunk back lifelessly into her former position. Cabot puts his hand down on the body in the crib. An expression of fear and horror comes over his face.)CABOT: (shrinking away—tremblingly) God A‟mighty! God A‟mighty. (He stumbles out the door —in a short while returns to the kitchen—comes to Abbie, the stunned expression still on his face—hoarsely) Why did ye do it? Why? (A s she doesn‟t answer, he grabs her violently by the shoulder and shakes her.) I ax ye why ye done it! Ye‟d better tell me ‟r . . . 9!ABBIE: (gives him a furious push which sends him staggering10back and springs to her feet—with wild rage and hatred) Don‟t ye dare tech me! What right hev ye t‟ question me ‟bout him?He wa‟n‟t yewr son! Think I‟d have a son by yew? I‟d die fust! I hate the sight o‟ ye an‟ allus did! It‟s yew I should‟ve murdered11, if I‟d had good sense! I hate ye! I love Eben. I did from the fust12. An‟ he was Eben‟s son—mine an‟ Eben's—not your‟n!CABOT: (stands looking at her dazedly—a pause—finding his words with an effort—dully) That was it—what I felt—pokin‟ ‟round the corners—while ye lied—holdin‟ yerself from me—sayin‟ ye‟d a‟ready conc eived—(He lapses into13crushed silence—then with a strange emotion) He‟s dead, sart‟n. I felt his heart. Pore little critter14! (He blinks back one tear, wiping his sleeve across his nose.)ABBIE: (hysterically) Don‟t ye! Don‟t ye! (She sobs unrestrainedly.)CABOT: (with a concentrated effort that stiffens his body into a rigid line and hardens his face into a stony mask—through his teeth to himself) I got t‟ be—like a stone—a rock o‟ jedgment!(A pause. He gets complete control over himself—h arshly) If he was Eben‟s, I be glad he airgone! An‟ mebbe I suspicioned it all along. I felt they was somethin‟ onnateral—somewhars —the house got so lonesome—an‟ cold—drivin‟ me down t‟ the barn—t‟ the beasts o‟ the field. . . . Ay-eh. I must‟ve suspicion ed—somethin‟. Ye didn‟t fool me—not altogether, leastways—I'm too old a bird—growin‟ ripe on the bough. . . . (He becomes aware he is wandering, straightens again, looks at Abbie with a cruel grin.) So ye‟d liked t‟ hev murdered me ‟stead o‟ him, would ye?Waal, I‟ll live to a hundred! I‟ll live t‟ see ye hung! I'll deliver ye up t‟ the jedgment o‟ God an‟ the law! I‟ll git the Sheriff now. (starts for the door)ABBIE: (dully) Ye needn‟t. Eben‟s gone fur him.CABOT: (amazed) Eben—gone fur the Sheriff?ABBIE: Ay-eh.CABOT: T‟ inform agen ye?ABBIE: Ay-eh.CABOT: (considers this—a pause—then in a hard voice) Waal, I‟m thankful fur him savin‟ me the trouble. I‟ll git t‟ wuk. (He goes to the door—then turns—in a voice full of strange emotion) He‟d ought t' been my son, Abbie. Ye‟d ought t‟ loved me. I‟m a man. If ye‟d loved me, I‟d never told no Sheriff on ye no matter what ye did, if they was t‟ brile me alive!ABBIE: (defensively) They‟s more to it nor yew know, makes him tell.CABOT: (dryly) Fur yewr sake, I hope they be. (He goes out—comes around to the gate—stares up at the sky. His control relaxes. For a moment he is old and weary. He murmurs9ax: ask; ye: you; ‟r: or10stagger vt. 蹒跚;使交错;使犹豫11murder vt.谋杀,凶杀12fust: first; from the fust: from the first13lapse into陷入14critter n. 人;家畜;马;牛despairingly15) God A‟mighty, I be lonesomer16‟n ever! (He hears running footsteps from the left, immediately is himself again. Eben runs in, panting exhaustedly, wild-eyed and mad looking. He lurches17through the gate. Cabot grabs him by the shoulder. Eben stares at him dumbly.) Did ye tell the Sheriff?EBEN: (nodding stupidly) Ay-eh.CABOT: (gives him a push away that sends him sprawling18—laughing with withering contempt) Good fur ye! A prime chip o‟ yer Maw ye be! (He goes toward the barn, laughing harshly.Eben scrambles19to his feet. Suddenly Cabot turns—grimly threatening) Git off this farm when the Sheriff takes her—or, by God, he‟ll have t‟ come back an‟ git me fur murder, too!(He stalks off. Eben does not appear to have heard him. He runs to the door and comes into the kitchen. Abbie looks up with a cry of anguished joy. Eben stumbles over and throws himself on his knees beside her—sobbing brokenly)EBEN: Fergive20me!ABBIE: (happily) Eben! (She kisses him and pulls his head over against her breast.)EBEN: I love ye! Fergive me!ABBIE: (ecstatically) I‟d fergive ye all the sins in hell fur sayin‟ that! (She kisses h is head, pressing it to her with a fierce passion of possession.)EBEN: (brokenly) But I told the Sheriff. He‟s comin‟ fur ye!ABBIE: I kin b‟ar what happens t‟ me—now!EBEN: I woke him up. I told him. He says, wait till I git dressed. I was waiting. I got to thinkin‟ o‟ yew. I got to thinkin‟ how I‟d loved ye. It hurt like somethin‟ was bustin‟ in my chest an‟ head.I got t‟ cryin‟. I knowed sudden I loved ye yet, an‟ allus would love ye!ABBIE: (caressing21his hair—tenderly) My boy, hain‟t ye?EBEN: I beg un t‟ run back. I cut across the fields an‟ through the woods. I thought ye might have time t‟ run away—with me—an‟. . . .ABBIE: (shaking her head) I got t‟ take my punishment—t‟ pay fur my sin.EBEN: Then I want t‟ share it with ye.ABBIE: Ye didn‟t do nothin‟.EBEN: I put it in yer head. I wisht he was dead! I as much as urged ye t‟ do it!ABBIE: No. It was me alone!EBEN: I‟m as guilty as yew be! He was the child o‟ our sin.ABBIE: (lifting her head as if defying22God) I don‟t repent that sin! I hain‟t askin‟ God t‟ fergive that!EBEN: Nor me—but it led up t‟ the other—an‟ the murder ye did, ye did ‟count o‟ me—an‟ it‟s my murder, too, I‟ll tell the Sheriff—an‟ if ye deny it, I'll say we planned it t‟gether—an‟ they‟ll all b‟lieve me, fur they suspicion everythin‟ we‟ve done, an‟ it‟ll seem likely an‟ true to 'em.An‟ it is true—way down. I did help ye—somehow.ABBIE: (laying her head on his—sobbing) No! I don't want yew t‟ suffer!15despairingly adv. 绝望地;自暴自弃地16lonesomer: lonesome adj. 寂寞的;人迹稀少的17lurch n. 突然倾斜;蹒跚;18sprawl v. 蔓延;伸开手足躺19scramble vt.攀登;爬行20Fergive: forgive vt. 原谅;21caress vt.爱抚,抚抱22defy vt. 藐视;公然反抗EBEN: I got t‟ pay fur my part o‟ the sin! An‟ I'd suffer wuss leavin‟ ye, goin‟ West, thinkin‟ o‟ ye day an‟ night, bein‟ out when yew was in—(lowering his voice) ‟R bein‟ alive when yew was dead. (a pause) I want t‟ share with ye, Abbie—prison ‟r death …r hell ‟r anythin‟! (He looks into her eyes and forces a trembling sm ile.) If I‟m sharin‟ with ye, I won‟t feel lonesome, leastways.ABBIE: (weakly) Eben! I won‟t let ye! I can‟t let ye!EBEN: (kissing her—tenderly) Ye can‟t he‟p yerself. I got ye beat fur once!ABBIE: (forcing a smile—adoringly) I hain‟t beat—s‟long‟s I got ye!EBEN: (hears the sound of feet outside) Ssshh! Listen! They‟ve come t‟ take us!ABBIE: No, it‟s him. Don‟t give him no chance to fight ye, Eben. Don‟t say nothin‟—no matter what he says. An‟ I won‟t, neither. (It is Cabot. He comes up from the b arn in a great state of excitement and strides into the house and then into the kitchen. Eben is kneeling beside Abbie, his arm around her, hers around him. They stare straight ahead.)CABOT: (stares at them, his face hard. A long pause—vindictively23) Ye m ake a slick pair o‟ murderin‟ turtle doves! Ye‟d ought t‟ be both hung on the same limb an‟ left thar t‟ swing in the breeze an' rot—a warnin‟ t‟ old fools like me t‟ b‟ar their lonesomeness alone—an‟ fur young fools like ye t‟ hobble their lust. (A pause. The excitement returns to his face, his eyes snap, he looks a bit crazy.) I couldn‟t work today. I couldn‟t take no interest. T‟ hell with the farm. I‟m leavin‟ it! I‟ve turned the cows an‟ other stock loose. I‟ve druv ‟em into the woods whar they kin be free! By freein‟‟em, I‟m freein‟ myself! I‟m quittin‟ here today! I‟ll set fire t‟ house an‟ barn an‟ watch ‟em burn, an‟ I‟ll leave yer Maw t‟ haunt the ashes, an‟ I'll will the fields back t‟ God, so that nothin‟ human kin never touch ‟em! I‟ll be a-goi n‟ to California—t‟ jine Simeon an‟ Peter—true sons o‟ mine if they be dumb fools—an‟ the Cabots‟ll find Solomon‟s Mines t‟gether! (He suddenly cuts a mad caper.) Whoop! What was the song they sung? “Oh, California! That‟s the land fur me.” (He sings this—then gets on his knees by the floorboard under which the money was hid.) An‟ I‟ll sail thar on one o‟ the finest clippers I kin find! I‟ve got the money! Pity ye didn‟t know whar this was hidden so‟s ye could steal. . . . (He has pulled up the board. He stares—feels—stares again. A pause of dead silence. He slowly turns, slumping into a sitting position on the floor, his eyes like those of a dead fish, his face the sickly green of an attack of nausea. He swallows painfully several times—forces a weak smile at last.) So—ye did steal it!EBEN: (emotionlessly) I swapped it t‟ Sim an‟ Peter fur their share o' the farm—t‟ pay their passage t‟ California.CABOT: (with one sardonic24) Ha! (He begins to recover. Gets slowly to his feet—strangely) I calc‟late God give it to ‟em—not yew! God's hard, not easy! Mebbe they‟s easy gold in the West, but it hain‟t God's gold. It hain‟t fur me. I kin hear His voice warnin‟ me agen t‟ be hard an' stay on my farm. I kin see his hand usin‟ Eben t‟ steal t‟ keep me from weakness. I kin feelI be in the palm o‟ His hand, His fingers guidin‟ me. (A pause—then he mutters sadly) It‟sa-goin‟ t‟ be lonesomer now than ever it war afore—an' I'm gittin‟ old, Lord—ripe on the bough. . . . (then stiffening25) Waal—what d‟ye want? God's lonesome, hain‟t He? God's hard an‟ lonesome! (A pause. The sheriff with two men comes up the road from the left. They move cautiously to the door. The sheriff knocks on it with the butt of his pistol.)23vindictively adv. 恶毒地;报复地24sardonic adj.讽刺的;嘲笑的,冷笑的25stiffen v.变硬;变猛烈SHERIFF: Open in the name o‟ the law! (They start.)CABOT: They‟ve come fur ye. (He goes to the rear door.) Come in, Jim! (The three men enter.Cabot meets them in doorway.) Jest a minit, Jim. I got ‟em safe here. (The sheriff nods. He and his companions remain in the doorway.)EBEN: (suddenly calls) I lied this m ornin‟, Jim. I helped her do it. Ye kin take me, too.ABBIE: (brokenly) No!CABOT: Take 'em both. (He comes forward—stares at Eben with a trace of grudging admiration.) Putty good—fur yew! Waal, I got t' round up the stock. Good-by.EBEN: Good-by.ABBIE: Good-by. (Cabot turns and strides past the men—comes out and around the corner of the house, his shoulders squared, his face stony, and stalks grimly toward the barn. In the meantime the sheriff and men have come into the room.)SHERIFF: (embarrassedly) Waal—we‟d best start.ABBIE: Wait, (turns to Eben) I love ye, Eben.EBEN: I love ye, Abbie. (They kiss. The three men grin and shuffle embarrassedly. Eben takes Abbie‟s hand. They go out the door in rear, the men following, and come from the house, walking h and in hand to the gate. Eben stops there and points to the sunrise sky.) Sun‟s a-rizin‟. Purty26, hain‟t it?ABBIE: Ay-eh. (They both stand for a moment looking up raptly in attitudes strangely aloof and devout.)SHERIFF: (looking around at the farm enviously—to his companion) It‟s a jim-dandy27farm, no denyin‟. Wished I owned it!(The Curtain Falls)参考译文..............................................................................第四场人物:以法莲·凯勃特;西蒙,彼得,埃本(凯勃特的儿子);爱碧·普特南(凯勃特的年轻妻子);治安官。

Eugene Oneill简介

Eugene O'NeillFrom Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia (Redirected from Eugene O’Neill) Jump to: navigation, searchEugene O'NeillPortrait of O'Neill by Alice BoughtonBorn Eugene Gladstone O'Neill October 16, 1888New York City, New York, USADied November 27, 1953 (aged 65) Boston, Massachusetts, USAOccupation Playwright Nationality United StatesNotable award(s) Nobel Prize in Literature (1936) Pulitzer Prize for Drama (1920, 1922, 1928, 1957)Spouse(s) Kathleen Jenkins (1909-1912) Agnes Boulton (1918-1929)Carlotta Monterey (1929-1953)Eugene Gladstone O'Neill (16 October 1888 – 27 November 1953) was an American playwright, and Nobel laureate in Literature. His plays are among the first to introduce into American drama the techniques of realism, associated with Russian playwright Anton Chekhov, Norwegian playwright Henrik Ibsen, and Swedish playwright August Strindberg. His plays were among the first to include speeches in American vernacular and involve characters on the fringes of society, engaging in depraved behavior, where they struggle to maintain their hopes and aspirations, but ultimately slide into disillusionment and despair. O'Neill wrote only one well-known comedy (Ah, Wilderness!).[1][2] Nearly all of his other plays involve some degree of tragedy and personal pessimism.Contents[hide]∙ 1 Early years∙ 2 Career∙ 3 Family life∙ 4 Illness and death∙ 5 Museums and collections∙ 6 Worko 6.1 Full-length playso 6.2 One-act playso 6.3 Other works∙7 See also∙8 References∙9 Further reading∙10 External links[edit] Early yearsO'Neill was born in a Broadway hotel room in Times Square, specifically the Barrett Hotel. The site is now a Starbucks(1500 Broadway, Northeast corner of 43rd & Broadway); a commemorative plaque is posted on the outside wall with the inscription: "Eugene O'Neill, October 16, 1888 ~ November 27, 1953 America's greatest playwright was born on this site then called Barrett Hotel, Presented by Circle in the Square."[3]He was the son of Irish actor James O'Neill and Mary Ellen Quinlan . Because of his father's profession, O'Neill was sent to a Catholic boarding school where he found his only solace in books. O'Neill spent his summers in New London , Connecticut . After being suspended from Princeton University , he spent several years at sea, during which he suffered from depression and alcoholism . O'Neill's parents and elder brother Jamie (who drank himself to death at the age of 45) died within three years of one another, and O'Neill turned to writing as a form of escape. Despite his depression he had a deep love for the sea, and it became a prominent theme in most of his plays, several of which are set onboard ships like the ones that heworked on.Birthplace plaque in Times Square, NYC. Portrait of O'Neillas a child, c. 1893.Statue of a young Eugene O'Neill on the waterfront. [edit ] CareerO'Neill's first play, Bound East for Cardiff , premiered at this theatre on a wharf in Provincetown, Massachusetts.It wasn't until his experience in 1912–13 at a sanatorium where he was recovering from tuberculosis that he decided to devote himself full time to writing plays (the events immediately prior to going to the sanatorium are dramatized in his masterpiece, Long Day's Journey into Night ). O'Neill had previously been employed by the New London Telegraph , writing poetry as well as reporting.During the 1910s O'Neill was a regular on the Greenwich Village literary scene, where he also befriended many radicals, most notably Communist Labor Party founder John Reed. O'Neill also had a brief romantic relationship with Reed's wife, writer Louise Bryant. O'Neill was portrayed by Jack Nicholson in the 1981 film Reds about the life of John Reed.His involvement with the Provincetown Players began in mid-1916. O'Neill is said to have arrived for the summer in Provincetown with "a trunk full of plays." Susan Glaspell describes what was probably the first ever reading of Bound East for Cardiff which took place in the living room of Glaspell and her husband George Cram Cook's home on Commercial Street, adjacent to the wharf (pictured) that was used by the Players for their theater. Glaspell writes in The Road to the Temple, "So Gene took Bound East for Cardiff out of his trunk, and Freddie Burt read it to us, Gene staying out in the dining-room while reading went on. He was not left alone in the dining-room when the reading had finished." [4] The Provincetown Players performed many of O'Neill's early works in their theaters both in Provincetown and on MacDougal Street in Greenwich Village. Some of these early plays began downtown and then moved to Broadway.O'Neill's first published play, Beyond the Horizon, opened on Broadway in 1920 to great acclaim, and was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Drama. His first major hit was The Emperor Jones, which ran on Broadway in 1920 and obliquely commented on the U.S. occupation of Haiti that was a topic of debate in that year's presidential election.[5] His best-known plays include Anna Christie(Pulitzer Prize 1922), Desire Under the Elms(1924), Strange Interlude(Pulitzer Prize 1928), Mourning Becomes Electra(1931), and his only well-known comedy, Ah, Wilderness!,[2][6] a wistfulre-imagining of his youth as he wished it had been. In 1936 he received the Nobel Prize for Literature. After a ten-year pause, O'Neill's now-renowned play The Iceman Cometh was produced in 1946. The following year's A Moon for the Misbegotten failed, and did not gain recognition as being among his best works until decades later.He was also part of the modern movement to revive the classical heroic mask from ancient Greek theatre and Japanese Noh theatre in some of his plays, such as The Great God Brown and Lazarus Laughed.[7]O'Neill was very interested in the Faust theme, especially in the 1920s.[8] He is also known for the very poetic names of many of his plays.[edit] Family lifeO'Neill was married to Kathleen Jenkins from October 2, 1909 to 1912, during which time they had one son, Eugene Jr. (1910–1950). In 1917, O'Neill met Agnes Boulton, a successful writer of commercial fiction, and they married on April 12, 1918. The years of their marriage—during which the couple had two children, Shane and Oona—are described vividly in her 1958 memoir Part of a Long Story. They divorced in 1929, after O'Neill abandoned Boulton and the children for the actress Carlotta Monterey (born San Francisco, California, December 28, 1888—died Westwood, New Jersey, November 18, 1970). O'Neill and Carlotta married less than a month after he officially divorced his previous wife.[9]O'Neill in the mid-1930s. He received the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1936In 1929, O'Neill and Monterey moved to the Loire Valley in central France, where they lived in the Château d u Plessis in Saint-Antoine-du-Rocher, Indre-et-Loire. During the early 1930s they returned to the United States and lived in Sea Island, Georgia, at a house called Casa Genotta. He moved to Danville, California in 1937 and lived there until 1944. His house there, Tao House, is today the Eugene O'Neill National Historic Site.In their first years together, Monterey organized O'Neill's life, enabling him to devote himself to writing. However, she later became addicted to potassium bromide, and the marriage deteriorated, resulting in a number of separations. O'Neill needed her, and she needed him. Although they separated several times, they never divorced.Actress Carlotta Monterey in Plymouth Theatre production of O'Neill's The Hairy Ape, 1922. Monterey later became the playwright's third wife.In 1943, O'Neill disowned his daughter Oona for marrying the English actor, director and producer Charlie Chaplin when she was 18 and Chaplin was 54. He never saw Oona again.He also had distant relationships with his sons, Eugene, Jr., a Yale classicist who suffered from alcoholism, and committed suicide in 1950 at the age of 40, and Shane O'Neill, a heroin addict who also committed suicide.Child Date of Birth Date of Death NotesEugene O'Neill, Jr 1910 1950Shane O'Neill 1918 1977Oona O'Neill14/05/1925 27/09/1991[edit] Illness and deathGrave of Eugene O'NeillAfter suffering from multiple health problems (including depression and alcoholism) over many years, O'Neill ultimately faced a severe Parkinsons-like tremor in his hands which made it impossible for him to write during the last 10 years of his life; he had tried using dictationbut found himself unable to compose in that way. While at Tao House, O’Neill had intended to w rite a cycle of 11 plays chronicling an American family since the 1800s. Only two of these, A Touch of the Poet and More Stately Mansions were ever completed. As his health worsened, O’Neill lost inspiration for the project and wrote three largely autobiographical plays, The Iceman Cometh, Long Day's Journey Into Night, and A Moon for the Misbegotten. He managed to complete Moon for the Misbegotten in 1943, just before leaving Tao House and losing his ability to write. Drafts of many other uncompleted plays were destroyed by Carlott a at Eugene’s request.O'Neill died in Room 401 of the Sheraton Hotel on Bay State Road in Boston, on November 27, 1953, at the age of 65. As he was dying, he, in a barely audible whisper, spoke his last words: "I knew it. I knew it. Born in a hotel room, and God damn it, died in a hotel room."[10] The building would later become the Shelton Hall dormitory at Boston University. There is an urban legend perpetuated by students that O'Neill's spirit haunts the room and dormitory. A revised analysis of his autopsy report shows that, contrary to the previous diagnosis, he did not have Parkinson's disease, but a late-onset cerebellar cortical atrophy.[11]He is interred in the Forest Hills Cemetery in Boston's Jamaica Plain neighborhood.Although his written instructions had stipulated that it not be made public until 25 years after his death, in 1956 Carlotta arranged for his autobiographical masterpiece Long Day's Journey Into Night to be published, and produced on stage to tremendous critical acclaim and won the Pulitzer Prize in 1957. This last play is widely considered to be his finest. Other posthumously-published works include A Touch of the Poet (1958) and More Stately Mansions (1967).The United States Postal Service honored O'Neill with a Prominent Americans series (1965–1978) $1 postage stamp.[edit] Museums and collectionsO'Neill's home in New London, Monte Cristo Cottage, was made a National Historic Landmark in 1971. His home in Danville, California, near San Francisco, was preserved as the Eugene O'Neill National Historic Site in 1976.Connecticut College maintains the Louis Sheaffer Collection, consisting of material collected by the O'Neill biographer. The principal collectionof O'Neill papers is at Yale University . The Eugene O'Neill Theater Center in Waterford, Connecticut fosters the development of new plays under his name.[edit ] WorkSee also: Category:Plays by Eugene O'Neill[edit ] Full-length plays∙Bread and Butter , 1914 ∙Servitude , 1914 ∙The Personal Equation , 1915 ∙Now I Ask You , 1916 ∙ Beyond the Horizon , 1918 - Pulitzer Prize, 1920 ∙The Straw , 1919 ∙Chris Christophersen , 1919 ∙Gold , 1920 ∙Anna Christie , 1920 - Pulitzer Prize, 1922 ∙ The Emperor Jones , 1920 ∙Diff'rent , 1921 ∙The First Man , 1922 ∙ The Hairy Ape , 1922 ∙The Fountain , 1923 ∙Marco Millions , 1923–25 ∙ All God's Chillun Got Wings , 1924 ∙Welded , 1924 ∙ Desire Under the Elms , 1925 ∙ Lazarus Laughed , 1925–26 ∙ The Great God Brown , 1926 ∙ Strange Interlude , 1928 - Pulitzer Prize ∙ Dynamo , 1929 ∙ Mourning Becomes Electra , 1931 ∙ Ah, Wilderness!, 1933 ∙Days Without End , 1933 ∙ The Iceman Cometh , written 1939, published 1940, firstperformed 1946∙ Hughie , written 1941, firstperformed 1959[edit ] One-act plays The Glencairn Plays, all of which feature characters on the fictional ship Glencairn -- filmed together as The Long Voyage Home : ∙ Bound East for Cardiff , 1914 ∙ In The Zone , 1917 ∙ The Long Voyage Home , 1917 ∙ Moon of the Caribbees , 1918 Other one-act plays include: ∙ A Wife for a Life , 1913 ∙ The Web , 1913 ∙ Thirst , 1913 ∙ Recklessness , 1913 ∙ Warnings , 1913 ∙ Fog , 1914 ∙ Abortion , 1914 ∙ The Movie Man: A Comedy , 1914 [2][12] ∙ The Sniper , 1915 ∙ Before Breakfast , 1916 ∙Ile , 1917 ∙The Rope , 1918 ∙Shell Shock , 1918 ∙The Dreamy Kid , 1918 ∙ Where the Cross Is Made , 1918∙Long Day's Journey Into Night,written 1941, first performed1956 - Pulitzer Prize 1957∙ A Moon for the Misbegotten,written 1941-1943, firstperformed 1947∙ A Touch of the Poet, completedin 1942, first performed 1958∙More Stately Mansions, seconddraft found in O'Neill'spapers, first performed 1967∙The Calms of Capricorn,published in 1983[edit] Other works∙The Last Will and Testament of An Extremely Distinguished Dog, 1940.Written to comfort Carlotta as their "child" Blemie was approaching his death in December 1940.[13]。

约恩福瑟戏剧中的意象-概述说明以及解释

约恩福瑟戏剧中的意象-概述说明以及解释1.引言1.1 概述约恩福瑟(Eugene O'Neill)是20世纪最重要的戏剧家之一,他的作品以其深刻的人物描写和情感表达而闻名。

在他的戏剧中,意象起着重要作用,为观众提供了一种丰富的观赏体验。

本文将探讨约恩福瑟戏剧中的意象,并分析其在作品中的具体功能和意义。

在约恩福瑟戏剧中,意象是通过使用象征性的形象、符号或情境来传达作者想要表达的主题或意义。

这些意象可以是物体、动作、颜色、声音等,通过它们的存在和组合,戏剧中的情感和思想得以深入地传递和探索。

本文将分析约恩福瑟戏剧中的具体意象,并探讨它们在剧情和人物发展中的作用。

通过分析意象的用法和效果,读者将能够更好地理解约恩福瑟戏剧的深层含义,并体会到其所蕴含的情感和思想。

此外,本文还将讨论意象对观众的影响。

约恩福瑟通过精心构建的意象,引导观众思考人性、命运、家庭关系等普遍而复杂的话题。

这些意象不仅仅是装饰性的符号,它们通过触发观众的情感和思考,引发了对剧作主题的深入认识和思考。

因此,本文将研究意象如何激发观众的共鸣和思考,以及它们对观众审美体验的影响。

最后,本文还将展望约恩福瑟戏剧意象的研究方向。

意象作为戏剧研究中的重要概念,有待进一步深入探讨和研究。

未来的研究可以从不同的角度和视角,对约恩福瑟戏剧中的意象进行更加全面和深入的解读,以进一步揭示其中隐藏的丰富意义和表达方式。

综上所述,本文将以约恩福瑟戏剧中的意象为主题,分析其在作品中的作用和意义,并探讨意象对观众的影响。

通过对约恩福瑟戏剧中意象的深入研究,希望能够增进对戏剧的理解和欣赏,以及启发更多有关意象研究的进一步探索。

1.2文章结构文章结构的目的是为了使读者能够清晰地了解整篇文章的组织和内容安排。

为了达到这一目的,本文将采取如下的文章结构:1. 引言:在引言部分,将简要概述约恩福瑟戏剧中的意象的重要性,并介绍文章的结构。

2. 正文:2.1 约恩福瑟戏剧简介:首先,将介绍约恩福瑟戏剧的背景和特点,包括其创作背景、主要作品等。

榆树下的欲望分析解析

His career as a dramatist began and he had been wholly dedicated to the mission as a dramatist.

I knew it. I knew it. Born in a hotel room, and God damn it, died in a hotel room.

The Iceman Cometh (1946) 《送冰的人来了》

Long Day’s Journey Into Night (1956) Pulitzer Prize 《进入黑夜的漫长旅程》

Themes of his plays: tragic view of life

1 Life and death, illusion and disillusion, dream and reality, etc. Human existence and predicament 1 3 Disappointment and despair Meaning and purpose 2 4 The truth of life 2 Many characters are seeking meaning and purpose of life. 3 But ending with disappointment and despair.

The middle period: Expressionistic plays

Beyond the Horizon (1920) prize in literature

《天边外》 Pulitzer Prize & Nobel

Anna Christie (1922) 《安娜·克里斯蒂》 Pulitzer Prize

英美诺贝尔文学奖获得者

英美诺贝尔文学奖获得者1. 1907,吉卜林(Rudyard Kipling,1865-1936)in consideration of the power of observation,originality of imagination, virility of ideas and remarkable talent for narration which characterize the creations of this world-famous author The Jungle Book, Kim2. 1923,威廉·勃特勒·叶芝(W. B. Yeats),Irish poet and playwright for his always inspired poetry, which in a highly artistic form gives expression to the spirit of a whole nation (由于他那永远充满着灵感的诗,它们透过高度的艺术形式展现了整个民族的精神 ).《丽达与天鹅》Lida and the Swan3. 1925 萧伯纳(George Bernard Shaw), a playwright, for his work which is marked by both idealism and humanity, its stimulating satire often being infused with a singular poetic beauty. Widower’s House s Major Barbara Pygmalion, Saint Joan4. 1930年辛克莱·刘易斯(Sinclair Lewis),An American writer, for his vigorous and graphic art of description and his ability to create, with wit and humor, new types of characters. (由于他充沛有力、切身和动人的叙述艺术,和他以机智幽默去开创新风格的才华)Main Street5. 1932年约翰·高尔斯华绥( John Galsworthy),British Novelist and playwright for his distinguished art of narration which takes its highest form in The Forsyte Saga. (为其描述的卓越艺术——这种艺术在《福尔赛世家》中达到高峰 )6.尤金·奥尼尔(Eugene Gladstone O’Neil l),American playwright, for the power, honesty and deep-felt emotions of his dramatic works, which embody an original concept of tragedy (由于他剧作中所表现的力量、热忱与深挚的感情——它们完全符合悲剧的原始概念 )Works:Beyond the Horizon , Strange Interlude, L ong Days Journey into Night7. 1938年赛珍珠(PEARL BUCK)珀尔·塞登斯特里克·布克American writer for her rich and truly epic descriptions of peasant life in China and for her biographical masterpieces (她对于中国农民生活的丰富和真正史诗气概的描述,以及她自传性的杰作 )Works: The Good Earth8. 1948年托马斯·斯特恩斯·艾略特 Thomas Stearns Eliot poet, critic and playwright (对于现代诗之先锋性的卓越贡献) Works: The Waste Land, The Four Quartets9. 1949年威廉·福克纳William Faulkner,an American writer for his powerful and artistically unique contribution to the modern American novel. (因为他对当代美国小说做出了强有力的和艺术上无与伦比的贡献 )Works:The Sound and the Fury,As I Lie Dying,Go Down Moses10.1951伯特兰·罗Earl Bertrand Arthur William Russell a philosopher, mathematician, and writer in recognition of his varied and significant writings in which he champions humanitarian ideals and freedom of thought (表彰他所写的捍卫人道主义理想和思想自由的多种多样意义重大的作品1953年)Works:Religion and science11. 1953,温斯顿·丘吉尔,politician, historian, biographer, for his mastery of historical and biographical description as well as for brilliant oratory in defending exalted human values. (由于他在描述历史与传记方面的造诣,同时由于他那捍卫崇高的人的价值的光辉演说 1954年) Works: The Second World War, Memoirs of the Second World War12. 1954欧内斯特·海明威,Ernest Hemingway, an American novelist for his mastery of the art of narrative, most recently demonstrated in The Old Man and the Sea ,and for the influence that he has exerted on contemporary style. (因为他精通于叙事艺术,突出地表现在其近著《老人与海》之中;同时也因为他对当代文体风格之影响 )Works: The old Man and the Sea, The Sun Rises, For Whom the Bell Is Ringing13. 1962年约翰·斯坦贝克,John Steinbeck, an American novelist, for his realistic and imaginative writings,combining as they do sympathetic humor and keen social perception. (通过现实主义的、寓于想象的创作,表现出富于同情的幽默和对社会的敏感观察 1973年 )Works: <愤怒的葡萄>The Grapes of Wrath, Of Mice and Men《人与鼠》14. 1969, Samuel Beckett for his writing, which - in new forms for the novel and drama - in the destitution of modern man acquires its elevation Works: Waiting for Godot15. 1973帕特里克·怀特,Patrick Write an Australian author, playwright, for an epic and psychologicalnarrative art which has introduced a new continent into literature. (由于他史诗与心理叙述艺术,并将一个崭新的大陆带进文学中 )Works: The Eye of Storm16.1976, Saul Bellow, American novelist, for the human understanding and subtle analysis of contemporary culture that are combined in his work. (由于他的作品对人性的了解,以及对当代文化的敏锐透视 1978年)Works:Herzog, Seize the Day , Henderson the Rain King17. 1978, 艾萨克·巴什维斯·辛格Isaac Bashevis Singer,an American author, for his impassioned narrative art which, with roots in a Polish-Jewish cultural tradition, brings universal human conditions to life. (他的充满激情的叙事艺术,这种既扎根于波兰人的文化传统,又反映了人类的普遍处境)Works:《魔术师·原野王》18.1981 埃利亚斯·卡内蒂Elias Canetti,英国德语作家 for his writings marked by a broad outlook, a wealth of ideas and artistic power. (作品具有宽广的视野、丰富的思想和艺术力量 1983年 )Works: 《迷惘》Blendung,The Torch in My Ear, Agony of Flies19. 1983 威廉·戈尔丁,William Golding, a British novelist, for his novels which, with theperspicuity of realistic narrative art and the diversity and universality of myth, illuminate the human condition in the world of today)Works: Lord of the Flies, The Inheritors20. 1981, 约瑟夫·布罗茨基,苏裔美籍诗人他的作品超越时空限制,无论在文学上或是敏感问题方面都充分显示出他广阔的思想及浓郁的诗意1991年《从彼得堡到斯德哥尔摩》21. 1991,内丁·戈迪默,南非作家 who through her magnificent epic writing has - in the words of Alfred Nobel - been of very great benefit to humanity. 以强烈而直接的笔触,描写周围复杂的人际与社会关系,其史诗般壮丽的作品,对人类大有裨益1993年Works: Lying Days Burger's Daughter July's People22.1993,托尼·莫里森Tony Morrison,an American Writer who in novels characterized by visionary force and poetic import, gives life to an essential aspect of American reality. (其作品想象力丰富,富有诗意,显示了美国现实生活的重要方面)Works: Beloved, The Bluest Eye The Song of Solomon, Jazz, Tar Baby, Sula, Paradise23.1995年希尼,爱尔兰诗人由于其作品洋溢着抒情之美,包容着深邃的伦理,揭示出日常生活和现实历史的奇迹24. 2001年维·苏·奈保尔,V. S. Naipaul Indian British novelist, for having united perceptivenarrative and incorruptible scrutiny in works that compel us to see the presence of suppressed histories.其著作将极具洞察力的叙述与不为世俗左右的探索融为一体,是驱策我们从扭曲的历史中探寻真实的动力 2003年The House for Mr. Biswas, The Bend in the River,25. 2003, 库切,南非作家精准地刻画了众多假面具下的人性本质 who in innumerable guises portrays the surprisinginvolvement of the outsiderDisgrace, Waiting for the Barbarians, In the Heart of Darkness,Elizabeth Costello: Eight Periods of Class26.2005 年Harold Pinter,a playwright, who in his plays uncovers the precipice under everyday prattle and forces entry into oppression's closed rooms27. 2007年Doris Lessing,The Golden Note Book, The Sweetest Dream, The Grass is SingingThe spokeswoman of the female experience, who with skepticism, fire and visionary power has subjected a divided civilization to scrutiny.。

名人的成功心得_奥尼尔的故事

尤金·奥尼尔(Eugene Gladstone O’Neill,1888~1953),美国著名剧作家,现代戏剧的奠基人和最重要代表,他的创作对美国现代和当代戏剧有深远的影响,因此被誉为“20世纪美国戏剧传统的开创者”。

一生4次获普利策奖,并于1936年获诺贝尔文学奖。

经历丰富对于作家来说,最好的大学是社会,奥尼尔也是如此。

奥尼尔出生在纽约的一个演员家庭,幼年随父漂泊,儿时的经历促使他进入戏剧领域。

中学毕业后,他考入普林斯顿大学,后因酗酒闹事被开除学籍。

此后他开始了一系列的冒险经历。

奥尼尔曾跟随着淘金大军去过洪都拉斯,在非洲和南美当过水手,先后从事过演员、导演、记者、小职员等工作。

奥尼尔踏进文学领域纯属偶然。

1912年,奥尼尔因患肺结核住院。

住院期间,他研读了自古希腊以来的经典戏剧作品,此后便开始戏剧创作,成为了专业的作家。

多产的作家奥尼尔是美国文学史上的一座丰碑,他的剧作可以说是美国严肃戏剧、试验戏剧之滥觞。

他的戏剧创作标志着美国民族戏剧的成熟,并使之赶上世界水平。

奥尼尔是位多产作家,他一生创作了独幕剧21部,多幕剧28部。

其中优秀剧作有:《东航加的夫》、《加勒比斯之月》、《天边外》等。

奥尼尔生前3次获普利策奖,他自认为并得到公认的最好作品是《进入黑夜的漫长旅程》,这部剧作带有自传的性质。

1956年,这部剧作在他死后首次在瑞典上演,并又一次获得普利策奖。

作家趣事奥尼尔不喜欢出名,他获诺贝尔奖后,不愿到斯德哥尔摩去领奖。

曾经作为记者的他却拒绝别人为他拍摄新闻短片。

摄影师们精心设计了一个他得知获奖消息时的场面:一个电报投递员走向他家门口,奥尼尔听到门铃声来开门,然后笑逐颜开地把电报给站在身旁的妻子看。

而奥尼尔对这些安排的回答是:“让他们见鬼去吧!”奥尼尔爱喝酒,而且经常喝得一醉方休。

新婚之夜,他又喝得人事不省。

第二天早上醒来,他发现身旁躺着一个女人。

他奇怪地问道:“你究竟是谁?”“你昨天晚上娶的我。

Eugene_O'Neill

《大神布朗》 《拉散路笑了》

Strange Interlude (1928)

《奇妙的插曲》

Ah, Wilderness

(1933) 《啊,荒野》 (the only comedy)

Last and Best Phase

The Iceman Cometh (1946) 《卖冰的人来了》 Long Day’s Journey into Night (1956) 《长日入夜行》

《琼斯皇帝》

Anna Christie

《安娜.克里斯蒂》

The Hairy Ape

《毛猿》

Desire under the Elms

《榆树下的欲望》

All God’s Chillum Got Wings (1924)

《上帝的儿女都有翅膀》

The Great God Brown Lazarus Laughed (1926) (1926)

《榆树下的欲望》&《雷雨》

1. 家庭秩序:清教原则与封建伦理 2. 悲剧原因:原欲冲动与文化制约

His Point of View

(1)

O'Neill's great purpose was to try and discover the root of human desires and frustrations. He showed most of the characters in his plays as seeking meaning and purpose in their lives, some through love, some through religion, others through revenge, but all met disappointment.

【历届诺贝尔奖得主(三)】1936年文学奖和物理学奖1

文学奖美国,奥尼尔(EugeneGladstoneO'Neill1888-1953),剧本《天边外》、《在榆树下的欲望》尤金·奥尼尔(EugeneO'Neill,1888-1953年)美国著名剧作家,表现主义文学的代表作家。

主要作品有《琼斯皇》、《毛猿》、《天边外》、《悲悼》等。

尤金·奥尼尔是美国民族戏剧的奠基人。

评论界曾指出:“在奥尼尔之前,美国只有剧场;在奥尼尔之后,美国才有戏剧。

”一生共4次获普利策奖(1920,1922,1928,1957),并于1936年获诺贝尔文学奖。

简介尤金·奥尼尔(EugeneO’Neill,1888----1952),美国著名剧作家。

奥尼尔出生于纽约一个演员家庭,父亲是爱尔兰人。

1909年至1911年期间,奥尼尔曾至南美、非洲各地流浪,淘过金,当过水手、小职员、无业游民。

1911年回国后在父亲的剧团里当临时演员。

父亲不满意他的演出,他却不满意剧团的传统剧目。

他学习易卜生和斯特林堡,1914年到哈佛大学选读戏剧技巧方面的课程,并开始创作。

晚年,奥尼尔患上帕金森氏症,并与妻子卡罗塔爆发矛盾。

奥尼尔描述家庭悲剧的自传式剧本《进入黑夜的漫长旅程》原本是交托给他的独家出版社兰登书屋务必于他死后二十五年才可发表,但奥尼尔逝世后,卡罗塔接手此稿交由耶鲁大学出版社立即出版。

生平介绍出生奥尼尔出身于演员家庭,其父因收入所迫,一生专演《基督山伯爵》,虚耗了才华。

奥尼尔不愿走父亲的老路,未念完大学便去闯荡江湖。

1910年,他去商船上当海员,一年的海上生活给他以后的创作提供了大量素材。

后因患病住院,疗养期间阅读了希腊悲剧和莎士比亚、易卜生、斯特林堡等众多名家的剧作,开始习作戏剧。

不久进入著名的哈佛大学“第47号戏剧研习班”,在贝克教授指导下,剧作水平大有提高。

其时,美国实验性的小剧团运动方兴未艾,初创的普罗温斯顿剧团上演了奥尼尔第一部成熟的作品《东航加迪夫》(1914年),开始引起公众的注意。

尤金·奥尼尔戏剧的表现主义特征

南方论刊·2020年第12期尤金·奥尼尔戏剧的表现主义特征李紫红(广东第二师范学院 广东广州 510303)【摘要】美国戏剧家尤金·奥尼尔的戏剧既遵循表现主义艺术观的总原则,又因为在“戏剧叙事”和“戏剧冲突”这两个维度的不同处理风格而独具特色。

他的戏剧叙事方式乱中有序,场景设置在缺乏逻辑的表面之下自有其艺术规律;另一方面,他强化内在冲突,弱化外在冲突,刻意剥离冲突之间的逻辑关联,形成冲淡之美的同时,在貌似混乱的表象背后仍能清晰表现人的内在本质和生活的实质。

【关键词】尤金·奥尼尔;表现主义特征;戏剧叙事;戏剧冲突文化长廊尤金·奥尼尔(Eugene O’Neill)曾经四度获得普策利戏剧奖,并且至今仍是美国唯一一位获得诺贝尔文学奖的剧作家,为戏剧世界奉献了一系列令人难忘的作品,包括《安娜·克里斯蒂》《琼斯皇》《毛猿》《上帝的儿女都有翅膀》《榆树下的欲望》《奇异的插曲》《悲悼》《送冰的人来了》《进入黑夜的漫长旅程》《休伊》等。

佩尔·哈尔斯特龙在1936年诺贝尔文学奖官方颁奖辞中高度赞扬奥尼尔的创新求变及其作品中蕴含的悲剧精神;同时,他明确指出,奥尼尔在《琼斯王》中“大胆运用表现主义手法处理思想及社会问题”[1]。

奥尼尔在获奖致辞中也毫不掩饰自己对表现主义戏剧大师奥古斯特·斯特林堡的敬仰以及来自他的影响[2]。

从亚里士多德的“悲剧是对一个严肃、完整、有一定长度的行动的模仿”[3]到自然主义作家爱弥尔·左拉从人物塑造角度出发的“文学再现生活”[4],文学对于生活的呈现一直遵循传统法则。

19世纪末20世纪初滥觞于欧洲的表现主义流派视挖掘生活的本质为艺术的主要任务,强调自我,在反传统的艺术形式中努力表现被扭曲的现实生活。

表现主义戏剧弱化戏剧情节和人物性格,重视人物内在情感的外化,着力表现梦幻意识,情节的发展相对缺乏逻辑性[5]。

榆树下的欲望

Interpretation of the Text

第三幕第四场

(约一小时后。景同第三场。厨房和卡伯特的卧室。黎 明。天空被旭日照得绚丽多彩。艾比坐在桌旁,她疲惫 不堪,心力交瘁。她的头伏在手臂上,脸被遮住了。在 楼上,卡伯特仍旧睡着,后突然惊醒。他朝窗外看了一 眼,半惊奇半生气地哼了一声——撩开盖在身上的被子, 急急地穿上衣服。他以为艾比还睡在身边,看也不回头 看一眼便开始和她说话了。)

of Buenos Aires, Liverpool, and New York City, submerged himself in alcohol, and attempted suicide. Recovering briefly at the age of 24, he held a job for a few months as a reporter and contributor to the poetry column of the New London Telegraph but soon came down with tuberculosis. Confined to the Gaylord Farm Sanitarium in Wallingford, Conn., for six months (1912-13), he confronted himself soberly and nakedly for the first time and seized the chance for what he later called his "rebirth." He began to write plays. O'Neill's final years were spent in grim frustration. Unable to work, he longed for his death and sat waiting for it in a Boston hotel, seeing no one except his doctor, a nurse, and his third, Carlotta Monterey. O'Neill died as broken and tragic a figure as any he had created for the stage.

美国戏剧7、American-Drama

In the 19th century, along with the western expansion between 1814 and 1824 appeared such plays as She would be a solider (1819) by Mordecai Noah; or , The Plains of Chippewa (1819) by James Nelson Barker. Poetic plays were very popular in the first half of the 19th century. The most significant theatrical development from the Civil War to 1900 was the move in the direction of realism from domestic melodrama.

In1920 his first full-length play, Beyond the Horizon, was professionally produced on Broadway. It quickly became popular,and won the Pulitzer Prize, and the name of O’Neill became known throughout the country.

C. Drama in the 20th century

At the turn of the 20th century American drama pointed the way from a separation from the 19th century theatricality. It made its tentative attempt to place realistic plays on the American stage. During the 1920s the extravagant spending and general license of the boom period encouraged the use of the Broadway theater as upper class entertainment. The most famous of the little theaters were the Washington Square Players which was formed in New York’s Greenwich Village in 1914 and the Provincetown Players which was formed in Cape Cod, Massachusetts in 1915.

Eugene Glastone O'Neill 美国文学史尤金·奥尼尔课件

伊本:我和你一样有罪!他是咱们的罪恶所生 的孩子。 爱碧:我不忏悔这个罪恶!我不要上帝饶恕我 这个!

Extra Content

伊莉克特拉是希腊联军统帅阿伽门农和王后克 拉得耐斯特拉的女儿。特洛伊战争结束之后, 阿伽门农回国,但被王后和她的姘夫伊吉斯修 斯杀害。伊莉克特拉鼓舞她的弟弟欧莱斯提兹 入宫,杀死她的母亲和姘夫。精神医学家就把 这段女儿为了报父仇杀害母亲的故事,比喻为 女孩在心性发展上的恋父情结。 ELECTRA COMPLEX

Pulitzer Prize & Nobel Prize

Features of O’Neill’s Plays

Thematic

Features (naturalism):

depicting people who have no hope of controlling their destinies dealing with the basic issues of human existence and predicament: life and death, illusion and disillusion, communication and alienation, dream and reality, self and society, etc.

pure belief, simple church service, widespread disciples, disciplined life, wrathful God

The image of Cabot as a puritan

Cabot ( disciplined life )

你们真是一对杀人害命的好鸳鸯!你们得双双绞死在 树上,吊在风里,烂掉——这对我这样的老傻瓜倒是 个警告,应该独自去忍受孤独——对你们这些年纪轻 轻的色鬼也是个警告。我今天不能干活,我没兴趣。 这田庄见鬼去吧!我要离开它!我去把母牛和其他牲 畜都解了绳子,我去把它们都赶到树林里去,在那儿 它们可以自由了,我让它们自由,我也让自己自由! 我今天要离开这儿!我要把屋子和饲养场都放火烧了, 还要看着它们烧!我要让你妈在这废墟上出没。我把 这片土地归还上帝,这样任何人都永远别想碰它!

美国当代文学

美国威廉斯作于1944年。

制鞋工人汤姆的姐姐劳拉是瘸腿的残疾人,整日收集玩弄玻璃动物玩具。

母亲要求汤姆为姐姐物色婚姻对象。

汤姆带同事吉姆回家吃饭。

吉姆唤醒了劳拉压抑的热情,然而吉姆却早已有了未婚妻。

绝望的劳拉送给吉姆一只断了角的玻璃独角兽作为纪念。

The play is introduced to the audience by Tom as a memory play, based on his recollection of his mother Amanda and his sister Laura. Amanda's husband left the family long ago, and she remains stuck in the past. Tom works in a warehouse, doing his best to support them. He chafes under the banality and boredom of everyday life and spends much of his spare time watching movies in cheap cinemas and at all hours. Amanda is obsessed with finding a suitor for Laura, who spends most of her time with her glass collection. Tom eventually brings Jim home for dinner at the insistence of his mother, who hopes Jim will be the long-awaited suitor for Laura. Laura realizes that Jim is the man she loved in high school and has thought of ever since. He dashes her hopes, telling her that he is already engaged, and then leaves. Tom leaves too, and never returns to see his family again. However, Tom still remembers his sister, Laura.剧情介绍根据威廉斯同名话剧改编。

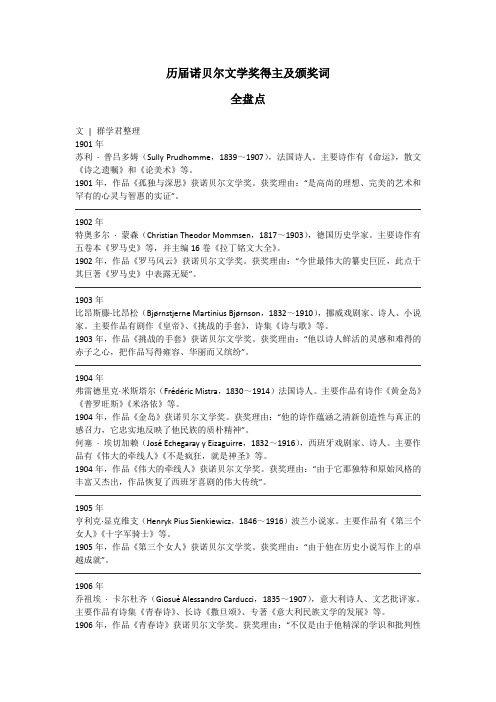

历届诺贝尔文学奖得主及颁奖词

历届诺贝尔文学奖得主及颁奖词全盘点文| 群学君整理1901年苏利·普吕多姆(Sully Prudhomme,1839~1907),法国诗人。

主要诗作有《命运》,散文《诗之遗嘱》和《论美术》等。

1901年,作品《孤独与深思》获诺贝尔文学奖。

获奖理由:“是高尚的理想、完美的艺术和罕有的心灵与智惠的实证”。

1902年特奥多尔·蒙森(Christian Theodor Mommsen,1817~1903),德国历史学家。

主要诗作有五卷本《罗马史》等,并主编16卷《拉丁铭文大全》。

1902年,作品《罗马风云》获诺贝尔文学奖。

获奖理由:“今世最伟大的纂史巨匠,此点于其巨著《罗马史》中表露无疑”。

1903年比昂斯滕·比昂松(Bjørnstjerne Martinius Bjørnson,1832~1910),挪威戏剧家、诗人、小说家。

主要作品有剧作《皇帝》、《挑战的手套》,诗集《诗与歌》等。

1903年,作品《挑战的手套》获诺贝尔文学奖。

获奖理由:“他以诗人鲜活的灵感和难得的赤子之心,把作品写得雍容、华丽而又缤纷”。

1904年弗雷德里克·米斯塔尔(Frédéric Mistra,1830~1914)法国诗人。

主要作品有诗作《黄金岛》《普罗旺斯》《米洛依》等。

1904年,作品《金岛》获诺贝尔文学奖。

获奖理由:“他的诗作蕴涵之清新创造性与真正的感召力,它忠实地反映了他民族的质朴精神”。

何塞·埃切加赖(José Echegaray y Eizaguirre,1832~1916),西班牙戏剧家、诗人。

主要作品有《伟大的牵线人》《不是疯狂,就是神圣》等。

1904年,作品《伟大的牵线人》获诺贝尔文学奖。

获奖理由:“由于它那独特和原始风格的丰富又杰出,作品恢复了西班牙喜剧的伟大传统”。

1905年亨利克·显克维支(Henryk Pius Sienkiewicz,1846~1916)波兰小说家。

美国文学选读知识点整理

美国⽂学选读知识点整理1.Benjamin Franklin(1706~1790)Poor Richard’s AlmanacThe Autobiography2.Edgar Allan Poe(1809~1849)Tamerlane and Other PoemsMurders in the Rue MorguePoemsThe Purloined LetterThe Raven and other PoemsThe Gold BugTales of the Grotesque and ArabesqueThe Philosophy of CompositionTalesThe Poetic PrincipleThe Fall of the House of UsesAl AraafThe Red Masque of the Red Death LigeiaThe Black CatThe Cask of AmontilladoAnnabel LeeSonnet--To ScienceTo Helen3.Ralph Waldo Emerson(1803~1882) NatureSelf-RelianceThe American ScholarThe Divinity School AddressEssays:First SeriesEssays:Second SeriesRepresentative menEnglish TraitsThe Conduct of LifePoemsMay-Day and Other PiecesNathaniel Hawthorne(1804~1864)FanshaweTwice-told TalesMosses from an Old ManseScarlet LetterThe House of the Seven GablesThe Blithedale RomanceThe Marble Faun4.Herman Melville(1819~1891)TypeeOmooMardiRedburnWhite JacketMoby DickThe Confidence ManBattle PiecesClarelTimoleonBilly Budd5.Henry David Thoreau(1817~1862)On the Duty of Civil DisobedienceA Week on the Concord and Merrimack RiverWalden6.Henry Wadsworth Longfellow(1807~11882) V oices of the Night Ballads and Other PoemsEvangelineThe Song of HiawathaI shot an ArrowA Psalm of Life7.Walt Whitman(1819~1892)Leaves of GrassOne’s Self I SingO Captain!My Captain8.Emily Dickinson(1830~1886)To Make a PrairieSuccess Is Counted SweetestI’m Nobody!9.Mark Twain (1835~1910)The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras CountryThe Innocents AbroadThe Gilded AgeThe Adventures of Tom SawyerLife on the MississippiThe Adventures of Hucklebeerry finnA Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court The Tragedy of Pudd’nhead Wilson The Man That Corrupted Hadleyburg10.Henry James(1843~1916)A Passionate PilgrimRoderick HudsonThe Novels and Tales of Henry JamesThe AmericanDaisy MillerThe Portrait of a LadyThe BostoniansThe Princess of CasamassimaThe Spoils of PoyntonThe Turn of the ScrewThe Awkward AgeThe Wings of the DoveThe AmbassadorsThe Golden BowlThe Art of FictionThe American SceneThe Jolly Corner11.Stephen Crane(1871~1900)Maggie:A Girl of the StreetsThe Red Badge of CourageThe Open BoatThe Bride Comes to Y ellow SkyThe Blue Hotel12.Willa Cather(1873~1947)Miss Jewett13.Sherwood Anderson(176~1941) Windy McPherson’s Son Winesburg,OhioMarching MenPoor WhiteThe triumph of the Egg and Other StoriesHorses and MenMany MarriagesDark LaughterBeyond DesireDeath in the Woods and Other Stories14.Katherine Anne Porter(1890~1980) The Flowering Judas Pale Horse,Pale RiderThe Leaning TowerThe Old OrderOld MortalityA Ship of FoolsThe Jilting of Granny Weatherall15.F.Scott Fitzgerald(1896~1940)This Side of ParadiseThe Beautiful and the DamnedFlappers and PhilosophersTales of the Jazz AgeThe Great GatsbyTender is the NightThe Crack-Up16.William Faulkner(1897~1962)The Marble FaunSoldier’s PayThe Sound and the FuryMosquitoesAs I Lay DyingLight in AugustAbsalom,AbsalomThe HamletSartorisThe TownThe MansionBarn Burning17.Ernest Hemingway(1899~1961)In Our TimeThe Sun Also RisesA Farewell to ArmsFor Whom the Bell TollsThe Old Man and the SeaA Clean,Well-Lighted Place18.Ezra Pound(1885~1972)ExultationsPersonaeCathayCantosDes ImagistesIn a Station of the Metro19.Wallace Stevens(1879~1955)The Necessary AngelAnecdote of the Jar20.William Carlos Williams(1883~1963) Collected Later Poems Collected Early PoemsPatersonThe Red WheelbarrowSpring and All21.Robert Frost(1874~1963)A Boy’s WillNorth of BostonNew HamphshireCollected PoemsA Further RangeA Witness TreeFire and IceStopping by Woods on a Snowy EveningThe Road Not Taken22.Langston Hughes(1902~1967)The Weary BluesFine Clothes to the JewThe Dream Keeper and Other PoemsShakespeare in HarlemDreamsMe and the MuleBorder Line23.Archibald MacLeish(1892~1982)The Happy MarriageThe Poet of EarthConquistadorCollected PoemsJ.B.Ars Poetica24.Eugene Glastone O’Neill(1888~1953) Bound East for Cardiff In The ZoneThe Long V oyage HomeThe Moon of the CaribeesEmperor JonesThe Hairy ApeThe Great God BrownStrange InterludeDesire Under the ElmsMourning Becomes ElectraThe Iceman ComethA Touch of the PoetLong Day’s Journey Into NightThe Moon for the MisbegottenHughieMore Stately Mansions25.Eiwyn Brooks White(1899~1985)Talk of the TownIs Sex NecessaryElements of StyleStuart LittleCharlotte’s WebQuo V adimus or The Case for the Bicycle One Man’s MeatThe Points of My CompassLetters of E.B,whiteEssays of E.B,whitePoems and Sketches of E.B.White Writings from The New Y orkerOnce More to the Lake 26.Tennessee Williams(1911~1983) The Glass MenagerieA Streetcar Named DesireCat On a Hot Tin RoofSummer and SmokeThe Rose TattooCamino RealOrpheus DescendingSuddenly Last SummerThe Sweet Bird of Y outhThe Night of the Lguana27.Ralph Waldo Ellison(1914~1994) Invisible ManShadow and ActGoing to the Territory28.Robert Lowell(1917~1977)Lord Weary’s CastleLife StudiesThe DolphinSkunk Hour29.Elizabeth Bishop(1911~1979) North and SouthCollected PoemsGeography IIIIn the Waiting Room30.Theodore Roethke(1908~1963)The Waking PoemsThe Collected PoemsOn the Poet and His Craft:Selected Prose 31.Allen Ginsberg(1926~1997)HowlA Supermarket in California32.Sylvia Plath(1932~1963)The ColossusArielWinter TreesThe Bell JarLetters HomePoint Shirley33.Robert Hayden (1913~1980)Frederick Douglass34.Robert Bly(1926~)The Light Around the BodyThe SixtiesDriving Through Minnesota During the Hanoi Bombing 35.Maya Angelou(1928~)Still I Rise36.Arthur Miller(1915~2005) All My Sonse Death of a SalesmanThe CrucibleA View from the BridgeAfter the FallThe Archbishop’s CellingThe Misfits37.Saul Bellow(1915~2005) Dangling manThe VictimThe Adventures of Augie MarchHenderson the Rain KingHerzogSeize the DayMr.Sammler’s PlanetHumbolt’s GiftThe Dean’s DecemberMore Die of HeartbreakThe TheftThe ActualRavelsteinMosby’s Memories and Other StoriesThe Last AnalysisLooking for Mr.Green38.Joseph Heller(1923~1999) We Bombed in New Haven Something HappenedGood as GoldGod KnowsCatch-2239.Toni Morrison(1931~)The Bluest EyeSulaSong of SolomonTar BabyBelovedJazzParadiseLoveA MercyRecitatif40.Louise Erdrich(1954~)Love MedicineThe Beet QueenTracksThe Crown of ColumbusThe Bingo PalaceTales of Burning LoveThe Antelope WifeThe Last Report on the Miracles at Little No Horse The Master Butchers Singing Club Four SoulsThe Painted DrumThe Plague of DovesShadow TagLulu’s Boys。

尤金 奥尼尔写作特色分析 精品