耶鲁大学开放课程下载_公开课_汇总

Lecture+9耶鲁大学开放课程《聆听音乐》讲稿+

Professor Craig Wright: Okay. Let us start, ladies and gentlemen. We're going to pursue the issue of musical form today. It's an important thing to talk about because it allows us to follow a particular piece of music, and we'll be--I am using this metaphor of a musical journey and wanting to know where we are in music throughout the day today. Form is particularly important in all types of music--popular music as well as classical music--and we have this complex of material coming at us, this sonic material. And we try to make sense of it, and we say that it has a particular form. And we say it could have a particular structure even, so we tend to use metaphors having to do with architecture and things such as this.What we are really doing here is taking all of this sonic information that's coming into our brain and getting sorted, and makes us want to dance around or clap or be sad or happy, and make sense of it in terms of a few rather simple patterns. And musicians like to have forms because oftentimes it tells them what they ought to do next and where--here--I'm here but what ought to happen next? Well, if you've got a tried and true musical form that other musicians have used over the years, you might be inclined to use it too because your know your listener will be able to follow you.Now the other day, I asked early on in the course about the form in popular music, and I threw this out not really knowing what the answer would be. What's the most common form that one encounters when dealing with pop songs? And for the most part there was silence across the room, but one student--I have tracked him down--Frederick Evans, gave a very good answer--really a better answer than I could have given. So, clearly Frederick knew something about this idea of what he I think referred to as "verse and chorus" structure.I might call it "strophe and refrain," but it's the same thing whether you have it in a Lied of Franz Schubert or in a piece that I know nothing about. And Frederick is going to show us--introduce us--to a piece that I know nothing about. I sent him an e-mail last night saying, "Frederick, you gave a really good answer. Why don't you pick a piece, come up and demonstrate this?" So this is Frederick Evans. We're going--or excuse me. Yeah, Frederick Evans. He's going to come up here. I'm told we have to give him a microphone and he is going to introduce us to this particular piece. Now you probably all know what this piece is. How many of you have heard the piece we were just listening to? Everybody knows it. Who is the one person in the room that's never heard this piece before--has no clue what's happening? Moi. Okay? So Frederick, tell me about this piece, please.Frederick Evans: All right. This is a piece by 'N Sync--back when I was in fifth grade--and it's "Bye Bye Bye," and the pattern that it follows is really the archetype of a lot of popular songs. It's half of the chorus or so when it starts and then there's verse, chorus, verse, chorus and then what I call the bridge, which is like an emotional climax. And then the last one is a really powerful chorus where they just bring it home and then the music fades away.Professor Craig Wright: Okay. So it's this idea of changing text, then coming back to familiar text and familiar music, then changing, going back to the familiar new text, and then coming back to the familiar in terms of the chorus. Is that a fair shake?Frederick Evans: Yes, Sir. Yes.Professor Craig Wright: Okay. So shall we play--what are we going to hear first?Frederick Evans: So first you'll hear from seconds twenty-four to forty. This is an example of the verse where they have the beginning of the plot and then you have the chorus at seconds--about fifty-six--and that's where you get your repeating idea, which is what the piece is based on. And then last but not least, you have the emotional buildup where the background and the chord progression changes, a little more solemnly, and then there's the last chorus that just brings it home.Professor Craig Wright: Okay. Great. Let's listen to the-yeah. [music plays] Okay.Frederick Evans: Yep. So that was the first verse and that's when they really get you into what they're talking about.[music playing]Professor Craig Wright: What really interests me here is what they're using is a baroque ostinato "Lament bass" but that's--we'll get on to that in another week or so. So that's--okay. Now we'll go to the bridge, Frederick?Frederick Evans: Yes. There at the bridge is where they really sum up all their emotions and they really just want to tell you what they're building towards. [music playing]Professor Craig Wright: Okay. That's wonderful. Thank you, Frederick. That's exactly what I wanted. [laughs] [applause] Okay. How many want Craig to continue teaching this course and how many want Frederick? Let's hear it for Craig. [laughter] Let's hear it for Frederick. [applause] I knew it. Okay, but that's a good way of getting introduced to the idea of musical form.Let's talk about form now in classical music. The forms are a little more difficult in classical music because the music is more complex. And before we launch into a discussion of these musical forms, I want to talk about the distinction of genre in music and form in music. So we're going to go over to the board over here and you can see that I've listed the standard classical genres. What do we mean by genre in music? Well, simply musical type. So we've got this type called a symphony and this type of music called a string quartet and concerto, and so on. We could add other types: ballet, opera, things such as that. In the popular realm we've got genres too. We've got--classical New Orleans jazz would be a genre. Blues would be a genre. Grunge rock would be another sort of genre.A genre presupposes a particular performing force, a particular length of pieces and even dress and mode of behavior of the auditors--the listeners. If we were going to listen to the genre of a symphony, we would dress up one particular way, go to Woolsey Hall and expect to be there from eight o'clock until ten o'clock. If you were going to hear the Rolling Stones play at Toad's--where they do play occasionally--obviously one would not come at eight o'clock. One would come later, and one would dress in a particular sort of way and one would behave, presumably, in a different sort of way. So that's what we mean by genre, a kind of general type of music.Now today we'll start to talk about form in music, and what I need to say here is that each of these genres is made up of a--of movements, and each of the movements is informed by a particular form.So with the symphony we have four movements there: fast, slow, then either a minuet or a scherzo, and a final, fast movement, and each of these movements can be in one of the number of different forms and we'll talk about what they are in just a moment.So when we come to the string quartet, same sort of thing: fast, slow, minuet, scherzo, fast. Any one of those can be in a particular form. Concerto, generally, as mentioned before, has just three movements and sonata, a piano sonata, something played on a piano, or a violin sonata with violin and piano accompaniment--they generally have just three movements: fast, slow, fast. Okay.Let's talk about our forms now. In classical music things go by very quickly and it's difficult to kind of get a handle on it, and we, generally in life, don't like to be lost. We like to know where we are, we like to know what is happening, and this is what form allows us to do. So that if we're hearing a piece of music and all this stuff is coming at us we want to make sense of it by knowing approximately where we are. Am I still toward the beginning? Am I in the middle of this thing? Am I getting anywhere near the end of it? How should I respond at this particular point? Well, if we have in mind what I've identified here, we will be referring to as our six formal types, and we can think of these as templates that, when we're hearing a piece of music we make an educated decision about which formal type is in play. And then we drop down the model of this formal type, or the template of this formal type, and we sort of filter our listening experience through this template, or through this model.So here are our six models: ternary form, sonata allegro form, theme and variations, rondo, fugue, and ostinato. And they developed at various times in the history of music. Theme and variations is very old. Sonata-allegro is a lot more recent. Now of these, the ones that we'll be working with today are ternary form and sonata-allegro form, and sonata-allegro is the hardest, the most complex, the most difficult of all of these forms. It's so-called because it usually shows up in the first movement of a sonata, concerto, string quartet, symphony, so--and the first movements are fast so that's why we have allegro out there, and it most is associated with this idea of the sonata. It didn't necessarily originate there. It originated there and in the symphony, but for historical reasons we call this sonata because of its association with the sonata and the fact that it goes--and the fact that it goes fast--sonata-allegro form. So that in a symphony, usually your very first movement will be in sonata-allegro form.Your slow movement, well, that could be in theme and variations; it could be in rondo; it could be in ternary form. Your minuet and scherzo is almost always in ternary form and your last fast movement could be in sonata-allegro form. It could also be in theme and variations; could be in rondo; could be in fugue. Sometimes it's even in ostinato form. So you can see that these forms can show up and control--regulate--what happens inside of each of these movements. Okay? Are there questions about that? Does that seem straightforward enough? We have a big picture of genre here, movements within genre, and then forms informing each of the movements. Yes.Student: Did you say that the ternary form is normally used for the second movement?Professor Craig Wright: No. I said it's possible that it is--could be--used for the second movement. A ternary form is one of the forms that could be used with the slow second movement. We could also have theme and variations. We're going to hear one of those later in our course. It could also be a sortof slow rondo. So it's just one of really three possibilities there, but thanks for that question. Anything else? Okay.If not, let's talk then about ternary form because ternary form has much in common with what we experience in sonata-allegro form. Let me take a very straightforward example of ternary form. It's from Beethoven's "Für Elise," the piece--the piano piece that Beethoven wrote for one of his paramours at one time or another. Here. I'm going to tell you a story about this. My cell phone broke the other day.My cell phone broke the other day so I had to buy a new one. I was really happy about that. I hated to lose my old Mozart theme, but I then had to find a new Mozart theme. And nowadays my selections are more limited. So when you go on to these things--and in truth, I actually had my youngest son do this because I'm hopelessly incompetent with this kind of thing--you go on to these things, and now they only have one option for classical music, one option for--but it's called "Mozart" so good choice. Mozart has become the icon of classical music and I think it's the individual that should be the icon for classical music. All classical music now has been reduced down to just Mozart. Okay. I have no idea what that was about, but, well, who's calling?All right. So we have this piece in ternary form by Beethoven, and ternary form is--conveys to us simply the idea of presentation, diversion, re-presentation or statement, digression, restatement--anything like this. We like to diagram these in terms of alphabetical letters. You can think just A, B, A. [plays piano] All right. I'm going to pause here. We started out here. [plays piano] We are in this key. Major or minor? What do you think? Minor. All right. So were coming to the end of this A section. Here--The A section is very short [plays piano] but then [plays piano] we--major or minor? Major. Right. [plays piano] So what happened there? What do we call this? [plays piano] It's a very quick modulation. We've changed keys.And I'm going to digress here just for a moment to talk about this, which is this concept of relative major and minor. You may have noticed in music--and it's discussed briefly in the textbook--that there are pairs of keys, pairs of keys that have something in common. The members of the pairs have the same key signature, and we could take any key signature--three flats or two sharps, whatever--but there's going to be one major key with three flats and one minor key with three flats.And I think we have up on the board here an example of just that so you can see written in here the three flats, and this is a minor scale with three flats. Now we could also have three flats over here, but we encounter three flats where we have the major scale. This happens to work out so that it's pitched on C. If we come up three half steps in the keyboard, we come up to E-flat so the relative major--the major key in this pair--is always three half steps--[plays piano] one, two, three--three half steps up above its paired minor. Here's another one down at the bottom--happens to have one sharp in it. We have the key of G major here with one sharp but if we come down three half steps [plays piano] we get its relative minor down here, and the reason I mentioned this is not because we actually hear this very much.I'm not sure that I hear modulations to relative major because I don't have absolute pitch and I'm not tracking keys when I listen to pieces--and my guess is you're not either. So for the average listener, we may not hear the actual pitch relationship but we may hear that we've had a modulation and you cankind of make an educated guess: that about fifty percent of the time if it's going minor to major, it's coming in this relative arrangement-- where major down to minor; it's going in this relative arrangement, so this happens a lot.So here we are in the mid section of our ternary form, A B A. Here's the B part [plays piano] and then back to [plays piano] the minor A. [plays piano] Now that's just the opening section of this piece. It goes on to do other things, but it's a very succinct example of ternary form, and ternary form is a useful way of introducing a larger concept, which is sonata-allegro form.So let me flip the board here, and here we go on to this rather complex diagram. As I say, it's the most complex one of all the six forms that we'll be working with. It consists of three essential parts: exposition, development and recapitulation. So you could think you were coming out of ternary form. You've got an A here, you've got a B idea here and then you've got an A return back here--but this is a lot more complicated. There are things--lots of things--going on.And I should say also--in terms of fairness in advertising--that this is a model. This is also something of an abstraction or an ideal. Not every piece written in sonata-allegro form conforms to this diagram in all particulars. Composers wouldn't want to do that--they'd have to assert their independence or originality in one way or another--but it's a useful sort of model. It tells us what the norm is, what we can generally expect. So we've got these three sort of sine qua non here and then we've got two optional parts of this that we'll talk about as we proceed.So this is the way we set out then sonata-allegro form: exposition, development, recapitulation. So we start out with the first theme, in the tonic key of course. It might even have subsets to it so that we could have one A and one B and one C up here. I won't put them up there but it can happen. Then we have a transition in which we have a change of key, moving to the dominant key. Transitions tend to be rather unsettled. It gives you the sense of moving somewhere, going somewhere. That's why it's called a transition. It could also--musicians like--quickly--like to call it a "bridge." It's sort of leading you somewhere else--and maybe in that way it is similar to the type of bridge that Frederick was talking about earlier. So we have a transition or bridge that takes us to a second theme in--now in the dominant key. If, however, our symphony happened to begin in a minor key, then the second theme would come in in the relative major. So if we had C minor as Beethoven does in his Fifth Symphony-- [plays piano] So there we are there in C minor, but the second theme [plays piano] is in the relative major of E-flat. Both have three flats in it. So if you have the start in minor, then composers traditionally modulate, not to the dominant, but to the relative major--which is up on the third degree of the scale. That's why there's a big three (III) there.So then the second theme comes in. It's usually contrasting, lyrical, sweeter. You heard the difference there--more song-like in the Beethoven--not so much of that musical punch in the nose as I like to refer to it, but a more relaxed sort of second theme, and there is oftentimes some filler or what we might call an interstice and we come to a closing theme. That's abbreviated up here, just CT, closing theme of the exposition, closes the exposition.Closing themes tend to be rather simple in which they rock back and forth between dominant and tonic so that you could end on the tonic and that gives you a sense of conclusion of the exposition.Now what happens? Well, you see these dots up on the board. Anybody know what these dots mean? I think we--actually we talk about this if you read ahead in the textbook Can somebody tell me what the dots mean> Jerry?Student: Repeat?Professor Craig Wright: Okay. Repeat. Okay. So that's what dots in music do-- when we have these double bars and dots that means repeat so we got to repeat the whole exposition. If we didn't like it the first time, we get a second pass at it in the repeat. Then we go on to the development and as the term "development" suggests, we're going to develop the theme here, but it is oftentimes more than that. It could be something other than just the development and the expansion. It could actually be a contraction. Beethoven likes to strip away things and sort of play with particular subsets of themes or play with parts of motives.Generally speaking, your development is characterized by tonal instability--moves around a lot. You can't tell what key you're in--tonal instability--and it also tends to be, in terms of texture, the most polyphonic of any section in the piece. There's a lot of counterpoint usually to be found in the development section. Then towards the end of the development section we want to get back here to the return and we want to get back to our first theme and our tonic key. So composers oftentimes will sit on one chord. What they will sit on will happen to be the dominant. So I could put that up here. We could put a five (V) up here because we want a long period of dominant preparation. [sings] is where we're going, back over here. But we're going to set this up as preparation in terms of the dominant that wants to push us in to the tonic.So there we are back in the tonic now and all the first themes come back as they did before. We also have a bridge but this time it does not modulate. It stays in the tonic key. We don't want it to modulate because we've got to finish in the tonic here. So I was thinking just a moment ago it's kind of the "bridge to nowhere." It really is a bridge to nowhere. You go right back to where you were. You stay in that tonic key and the second theme material comes in, your closing theme comes in, and you could end the composition here.Sometimes Mozart as we will see in our course will end a piece right at this point--the end, right there--but more often than not composers will throw on a coda. What's a coda do? Well, it really says to the listener that "hey, the piece is sort of at an end here." Codas generally are very static harmonically. They're--there's not a lot of movement. It's--and I keep--maybe I should have got--come up a different metaphor here--the idea of throwing an anchor over, slowing the whole thing down, simplifying it to say we're at the end. So you get a lot of the [sings] kind of things in the coda just to tell the listener it's time to think about clapping at this point, or reaching for your coat. And the other optional--Coda--What's that come from? The Latin cauda (caudae) I guess. . Italian coda means tail, and these can be, like all tails, long or short. Mozart happened to like short codas. Beethoven liked longer codas. And the other optional component here is the introduction. My guess is--Jacob, what would you guess? How many--what portion of classical symphonies--you're an orchestral player--what portion of classical symphonies would begin with an introduction, would you say?Student: Most of them.Professor Craig Wright: Most of them? Well, we'll consider that. Let's go for fifty percent at the moment. We'll consider fifty percent at the moment, so we'll see. Now let's jump into a classical composition that begins with a movement in sonata-allegro form. We're going to open here with Mozart's "Eine kleine Nachtmusik," "A Little Night Music." This is sort of serenade stuff that he wrote for Vienna--sort of night music, evening music. Let's listen to a little of it. We're going to start with the first theme idea, and before she does let me play this. [plays piano] What about that? Conjunct or disjunct melody?Students: Disjunct.Professor Craig Wright: Disjunct, yeah. There's a lot of jumping around [plays piano] and that kind of thing. Notice it's mostly [plays piano] just a major triad with [plays piano] underneath. So if we were at a concert and we wanted to remember this, we'd probably have a lot of skippy Xs here. We don't have time to get into the particulars of this, but that's why we're doing all of this diagramming stuff. So we got a lot of these skipping Xs.All right. So let's listen to the first theme of Mozart's "Eine kleine Nachtmusik." [music plays] A little syncopation there. And a sort of a counterpoint to this, so maybe we've got a couple of little ideas in here: A, B and C. [music playing] Ah, agitation, movement. [music playing] Here goes the bass. [sings] Pause. So we had a cadence there, [sings]. That would be the end of the musical phrase, a cadence, and the music actually stopped. I used to like to think of this in terms of almost a drama. We've got a change of scene here the--where some characters have gone off, the stage is now clear, and other characters are going to come on. So what characters are going to come on? Well, a more lyrical second theme. I'm going to play just a bit of it for you. [plays piano]What about this? Is this a conjunct melody? Obviously, it's descending. Conjunct or disjunct? [plays piano] Very conjunct. Actually, it's just running down the scale. Now we don't have time, because this music is going by so fast. We've got our skippy opening theme going around like that. We don't have time to sort of write down all those Xs so maybe just--yeah. [sings] And maybe something-- [sings] something like that. So this is our first skippy theme. Our second theme [sings] has a nice sort of fall to it. Okay. Here's the second theme. [music playing] Repeat. [music playing] Now closing theme already. [music playing]What's the most noteworthy aspect of that theme? [sings] What do you think? Thoughts--what would you remember about that? How would you graph that? Yeah.Student: [inaudible]Professor Craig Wright: Okay. Yeah. It starts out [plays piano] and then it's really conjunct, right, because it's staying on one pitch level, sort of the ultimate conjunct joined to the point that it's a unison pitch, [sings]. So I'd remember that just like this idea. So our closing theme, [sings] almost is the "woodpecker" idea. Sorry. But think of that kind of [sings] or maybe even a machine gun--whatever sort of silly analogy you want to construct to help you remember that. Okay. So here we are almost at the end of the exposition. Let's listen now to the end of exposition and then we'll stop. [music playing] Okay. So we're going to stop there.Now on this recording what do you think? Well, I think--reasons for time--let's go ahead and we'll advance it up to the beginning of the development section. So now we should listen to this whole complex once again, but we're not going to do that. We're going to proceed here and we're going to go in to the development section. And it's kind of fun the way Mozart starts the development section here. [plays piano] Let me ask you this. We started here. [plays piano] The development begins higher or lower? [plays piano] Yeah?Student: Lower.Professor Craig Wright: Lower so he's dropped down to the dominant. He's now in the dominant [plays piano] and if he continued as he had, [plays piano] that's what he would have done. That's not what he does, however. [plays piano] He's sitting here [plays piano] and he ends up there [plays piano] so we get this sort of dissonant shift, and it's a signal. It's like the composer holding up a sign: "development---time for the development now!" Okay? So something--we've shifted, we--or a sort of slap in the face telling us that we're at a new point in our form, a new section in our form, the development section. So as we listen to this we'll hear Mozart move quickly through some--lots of different keys. I wouldn't be able to tell you what keys they are. I really wouldn't. But I do know that he moves through different keys. Then we will hear a re-transition start, but here is my challenge to you and why I'm sort of putting all these things up here. Which theme does he choose to develop here? Kind of interesting. Does he go with the first theme, [sings] or the [sings] or the [sings]? So which one? [music playing] [sings]Professor Craig Wright: Now he is all the way--first of all, what's the answer to the question? Which theme did he use here? We're now at the re-transition, we're almost finished this short development. Which one did he use? Who thinks they know? Raise your hand. Elizabeth?Student: The closing theme.Professor Craig Wright: Used just the closing theme [sings] so nothing but the closing theme in this short development section. Now we are at the re-transition and you're going to hear the violins come down [sings] but if I could sing the harmony--Maybe we should all sing it together. We'll be singing [sings]. It's the implied bass line. [sings] Then it's going to go [sings] back to the tonic. Then we're going to go [sings]. Then that first theme is going to come back in here. So let's listen to Mozart write a re-transition, and I'm going to sing the implied--or then sounded dominant that's going to lead to the tonic. [music playing] [sings] So all of the first theme material coming back--nothing new. [music playing] Here goes our bridge now--movement. [music playing] And he just cut it short. The first time he went there [sings]. That was what the bass did. This time he just stops the thing and stays in the tonic key. And then the rest of the material will come back in in the proper order in the tonic key. All right, but we need not hear that. Let's go on now to the coda and we're just going to listen generally to what happens in the coda here--typical coda with Mozart. [music playing] Tonic. [sings] [music playing] It's almost stereotypical. Right? [plays piano] You could have written that. I--even I could have written that--not so hard, but as they say, it's just a load of bricks to bring this thing to a conclusion. But it's a beautiful example of sonata-allegro form. It does what our model requires in all particulars in an unusually rapid rate here--about six minutes for this particular movement.。

《耶鲁大学开放课程:金融市场》(Open Yale course:Financial Markets)课程目录及下载地址(不断更新中)

《耶鲁大学开放课程:金融市场》(Open Yale course:Financial Markets)简介★小羊羊村长★大学开发课程粉丝Q群:122798308课程类型:金融课程简介:金融机构是文明社会的重要支柱。

它们为投资活动提供支持及风险管理。

如果我们想要预测金融机构动态及他们在这个信息时代中的发展态势,我们必须对其业务有所了解。

本课程将涉及的内容有:金融学理论、金融业的发展历程、金融机构(例如银行、保险公司、证券公司、期货公司及其他衍生市场)的优势与缺陷以及这些机构的未来发展前景。

课程结构:本课程每讲75分钟,一周两次,在2008年春季录制并收入耶鲁大学公开课程系列。

关于教授罗伯特希勒Robert J. Shiller是Yale大学Arthur M. Okun经济学讲座教授和Yale大学管理学院国际金融中心研究员. Shiller教授的研究领域包括行为金融学和房地产,并在“金融经济学杂志”,“美国经济评论”,“金融学杂志”,“华尔街杂志”和“金融时报”等著名刊物发表文章. 主要著作包括“市场波动”,“宏观市场”(凭借此书他获得了TIAA-CREF的保罗 A. 萨缪尔森奖),“非理性繁荣和金融新秩序:二十一世纪的风险”Robert J. Shiller is Arthur M. Okun Professor of Economics at Yale University and a Fellow at the International Center for Finance at the Yale School of Management. Specializing in behavioral finance and real estate, Professor Shiller has published in Journal of Financial Economics, American Economic Review, Journal of Finance, Wall Street Journal, and Financial Times. His books include Market V olatility, Macro Markets (for which he won the TIAA-CREF's Paul A. Samuelson Award), Irrational Exuberance and The New Financial Order: Risk in the Twenty-First Century.目录:1.Finance and Insurance as Powerful Forces in Our Economy and Society金融和保险在我们经济和社会中的强大作用2. The Universal Principle of Risk Management: Pooling and the Hedging of Risks风险管理中的普遍原理:风险聚集和对冲3. Technology and Invention in Finance金融中的科技与发明4. Portfolio Diversification and Supporting Financial Institutions (CAPM Model)投资组合多元化和辅助性的金融机构(资本资产定价模型)5. Insurance: The Archetypal Risk Management Institution保险:典型的风险管理制度6. Efficient Markets vs. Excess V olatility有效市场与过度波动之争7. Behavioral Finance: The Role of Psychology行为金融学:心理的作用8. Human Foibles, Fraud, Manipulation, and Regulation 人性弱点,欺诈,操纵与管制9. Guest Lecture by David Swensen大卫•斯文森的客座演讲10. Debt Markets: Term Structure债券市场:期限结构11. Stocks股票12. Real Estate Finance and Its Vulnerability to Crisis 房地产金融和其易受危机影响的脆弱性13. Banking: Successes and Failures银行业:成功和失败14. Guest Lecture by Andrew Redleaf安德鲁•雷德利夫的客座演讲15. Guest Lecture by Carl Icahn卡尔•伊坎的客座演讲16. The Evolution and Perfection of Monetary Policy货币政策的进化和完善17. Investment Banking and Secondary Markets投资银行和二级市场18. Professional Money Managers and Their Influence金融市场翻译团队介绍友情奉献世界顶级大学开放课程的博客/。

丰富多彩的各类开放课程资源 open courses

丰富多彩的开放课程资源联合国开放学习资源国际著名大学开放课程公益组织开放学习资源TED-Ed本来是一个展示教学视频的平台,在这个平台上,优秀的教育者和出色的动画师强强联手,打造精致的动画教学视频,拓展“传播有价值的思想”的TED理念到“打造有价值的课程”。

由斯坦福大学教授Andrew Ng和Daphne Koller创建的Coursera则成为最新一个弄潮者,著名科技博客Allthingsdigital报道说该项目分别获得了Kleiner Perkins 和NEA合伙人共计1600万美元的资助。

该项目旨在同顶尖的大学合作帮助他们创建在线免费课程。

目前已经签约的有普林斯顿、斯坦福、密歇根大学和宾夕法尼亚大学。

点击进去Coursera,你就可以看到各个大学栏目下的课程。

Coursera的运作模式同之前我们报道的另外一位斯坦福大学教授Sebastian Thrun创建的Udacity的模式颇为相似。

都是注册上课,都有固定的授课时间以及家庭作业等等。

目前,课程仍然以计算机科学为主。

并且两位创始人也没有任何收费计划。

这就意味着任何人都无需付费便可以收听到顶尖的计算机科学课程。

感兴趣的朋友可以点击进去看看(大部分的课程都在4月23号开课)Udacity上面的课程不是简单的让你观看录制好的教学视频。

而是基本上像你在学校接受教育一样。

对于课程,教授们会在视频下方放出具体的教学大纲,让你提前知道该课程每一节你能学到什么。

另外教授们还会布置家庭作业,并且规定了一个具体的提交时间。

等到课程全部结束你还会有一个最终得分,该得分将由平时的家庭作业得分和期末测试的分数占不同的权重构成。

另外除了专门放置课程的主站,Udacity还配备有一个专门的论坛,让学生们可以提交问题或者和其他学生一起讨论。

总之除了是通过视频的表现形式,其他的一切基本上和你在真实的大学接受教育一样,只要用心去学,能够学到很好的知识。

MITX项目:MITx是一个非营利的项目和网络免费课程的先驱。

耶鲁大学开放课程

耶鲁大学开放课程1。

《耶鲁大学开放课程:聆听音乐》(Open Yale course:Listening to Music)[YYeTs人人影视出品][中英双语字幕]/topics/2832525/2。

《耶鲁大学开放课程:基础物理》(Open Yale course:Fundamentals ofPhysics)[YYeTs人人影视出品][中英双语字幕]/topics/2834907/3。

《耶鲁大学开放课程:生物医学工程探索》(Open Yale course:Frontiers of Biomedical Engineering) [YYeTs人人影视出品][中英双语字幕]/topics/2834278/4。

《耶鲁大学开放课程:1871年后的法国》(Open Yale course:France Since 1871) [YYeTs人人影视出品][中英双语字幕]/topics/2835256/5。

《耶鲁大学开放课程—哲学:死亡》(Open Yale course—Philosophy:Death) [YYeTs人人影视出品][中英双语字幕]/topics/2824902/6。

《耶鲁大学开放课程:金融市场》(Open Yale course:Financial Markets)[YYeTs人人影视出品][中英双语字幕]/topics/2830134/7。

《耶鲁大学开放课程:心理学导论》(Open Yale course:Introduction to Psychology) [YYeTs人人影视出品][中英双语字幕]/topics/2827597/8。

《耶鲁大学开放课程:博弈论》(Open Yale course:Game Theory)[YYeTs人人影视出品] [中英双语字幕]/topics/2832107/9。

《耶鲁大学开放课程:1648-1945年的欧洲文明》(Open Yale course:European Civiliza tion,1648-1945) [YYeTs人人影视出品][中英双语字幕]/topics/2832611/10。

网易

网易公开课客户端下载区耶鲁大学公开课下载区返回公开课首页耶鲁大学《自闭症讲座》共13课下载至3课耶鲁大学开放课程《金融理论》共26课下载至第2课耶鲁大学《英国近代史》共25课下载至第16课耶鲁《资本主义的成功、危机和改革共23课下载至第12课耶鲁大学《近代社会理论的基础》共25课下载至第19课耶鲁大学《新生有机化学》共37课下载至第10课耶鲁大学《心理学导论》共20课下载至第19课耶鲁大学热门课《死亡》共26课下载至26课耶鲁大学热门课《聆听音乐》共23课下载至第17课耶鲁大学《政治哲学导论》共24课下载至第24课耶鲁大学《新约及其历史背景》共26课下载至第26课耶鲁大学《旧约全书导论》共24课下载至第24课耶鲁大学文学课《弥尔顿》共24课下载至第24课耶鲁大学《文学理论导论》共26课下载至第26课耶鲁大学《1945年后的美国小说》共26课下载至第26课耶鲁大学文学课《现代诗歌》共25课下载至第25课耶鲁大学《古希腊历史简介》共24课下载至第23课耶鲁大学经济课《金融市场》共26课下载至第26课耶鲁《进化、生态和行为原理》共36课下载至第7课耶鲁《生物医学工程探索》共25课下载至第16课有关食物的心理学、生物学和政治学共23课下载至第23课耶鲁大学《全球人口增长问题》共24课下载至第24课耶鲁大学《美国内战与重建》共27课下载至第21课耶鲁大学《罗马建筑》共23课下载至第17课耶鲁大学《基础物理》共24课下载至第11课巴黎高等商学院公开课下载区《新产品开发中的创造力和心理学》共4课下载至第2课《Web2.0时代的营销沟通》共8课下载至第8课巴黎高等商学院《决策统计学》共7课下载至第7课巴黎高商《会计与管理控制常见问题共12课下载至第12课巴黎高商《第二届金融与统计学大会共12课下载至第12课巴黎高等商学院《对话领袖》共3课下载至第3课巴黎高等商学院《直观的智慧》共11课下载至第11课麻省理工大学公开课下载区麻省《艺术和科技中的感觉与想象》共4课下载至第2课麻省理工《核反应堆安全》共6课下载至第6课麻省理工《电路和电子学》共26课下载至第9课麻省理工《供应链管理专题》共16课下载至第5课麻省理工《城市面貌——过去和未来共4课下载至第2课麻省理工学院《探索黑洞》共6课下载至第6课麻省理工学院《媒体、教育、市场》共14课下载至第14课麻省理工物理课程《电和磁》共36课下载至第17课麻省理工学院《固态化学导论》共33课下载至第33课麻省理工学院《商业及领导能力》共16课下载至第1课麻省理工学院《算法导论》共24课下载至第6课麻省理工学院《生物学导论》共35课下载至第35课麻省理工物理课《经典力学》共35课下载至第35课麻省理工《计算机科学及编程导论》共24课下载至第24课麻省理工学院《电影哲学》共4课下载至第4课麻省理工《西方世界的爱情哲学》共4课下载至第1课麻省理工学院《线性代数》共34课下载至第16课麻省理工学院《化学原理》共36课下载至第36课麻省理工学院《微分方程》共33课下载至第19课麻省理工学院《多变量微积分》共35课下载至第35课麻省理工《单变量微积分》共39课下载至第13课麻省理工学院《微积分重点》共18课下载至第18课麻省理工学院《热力学与动力学》共36课下载至第36课麻省理工学院《振动与波》共23课下载至第5课麻省理工学院《音乐的各种声音》共1课下载至第1课斯坦福大学公开课下载区《戴尔CEO Michael Dell谈创业和发共17课下载至第17课斯坦福大学《全球气候与能源计划》共12课下载至第1课《扎克伯格谈Facebook创业过程》共9课下载至第9课斯坦福《微软CEO谈科技的未来》共9课下载至第9课斯坦福大学《Twitter之父演讲》共14课下载至第14课斯坦福大学《百度CEO李彦宏演讲》共8课下载至第8课斯坦福:应对气候变化—后哥本哈根共6课下载至第3课斯坦福大学《癌症综合研究》共56课下载至第19课斯坦福大学《健康图书馆》共76课下载至第52课斯坦福《从生物学看人类行为》共25课下载至第4课斯坦福《非裔美国人历史——自由斗共18课下载至第18课斯坦福大学《临床解剖学》共14课下载至第4课斯坦福大学《抽象编程》共27课下载至第4课斯坦福大学《编程范式》共27课下载至第4课斯坦福大学《iPhone开发教程》共28课下载至第10课斯坦福大学《编程方法学》共28课下载至第23课斯坦福大学《7个颠覆你思想的演讲共7课下载至第7课斯坦福大学金融课《经济学》共10课下载至第5课斯坦福大学《商业领袖和企业家》共4课下载至第4课斯坦福大学《机器人学》共16课下载至第2课斯坦福大学法学课《法律学》共6课下载至第2课斯坦福大学《机器学习课程》共20课下载至第2课哈佛大学公开课下载区哈佛大学热门课程《公正》共12课下载至第12课哈佛大学热门课程《幸福课》共23课下载至第23课哈佛大学《计算机科学cs50》共20课下载至第20课普林斯顿大学公开课下载区普林斯顿大学《科技世界的领导能力共15课下载至第15课普林斯顿大学热门课程《人性》共12课下载至第12课普林斯顿大学《领导能力简介》共5课下载至第5课普林斯顿大学《能源和环境》共11课下载至第1课普林斯顿大学《国际座谈会》共18课下载至第18课加州大学伯克利分校公开课下载区加州大学伯克利分校《社会认知心理学》共25课下载至第1课加州伯克利《世界各地区人民和国家》共17课下载至第6课加州大学伯克利分校《数据统计分析》共42课下载至第10课加州大学洛杉矶分校公开课下载区加州大学洛杉矶分校-家庭夫妇心理共17课下载至第17课牛津大学公开课下载区牛津《<美丽公主>为何出自达芬奇之手》共5课下载至第5课牛津大学哲学课《哲学概论》共17课下载至第5课牛津大学《批判性推理入门》共6课下载至第4课牛津大学《尼采的心灵与自然》共7课下载至第1课旧金山亚洲艺术博物馆旧金山亚洲艺术博物馆《日本艺术史共22课下载至第6课亚琛工业大学亚琛工业大学《机械制造》共13课下载至第2课。

耶鲁大学开放课程1

那就意味着

90

00:04:22,840 --> 00:04:27,320

周四 有人会在这儿讲课

91

00:04:27,320 --> 00:04:28,740

可以推断 那个人就是我

92

00:04:28,740 --> 00:04:30,740

死亡本质或诸如此类的问题时 所产生的

65

00:03:11,531 --> 00:03:13,760

哲学疑问

66

00:03:13,760 --> 00:03:15,710

大致说来

67

00:03:15,750 --> 00:03:20,490

这门课首先会讲到形而上学

68

00:03:20,540 --> 00:03:22,890

86

00:04:14,500 --> 00:04:17,280

幸存对我来说是什么

87

00:04:17,280 --> 00:04:19,240

假如我从死亡中幸存 这意味着什么

88

00:04:19,240 --> 00:04:22,140

今晚活着对于我来说又意味着什么

89

61

00:02:56,240 --> 00:02:59,600

我们在这堂课上要讨论的话题

62

00:03:00,060 --> 00:03:02,170

那么 我们要讨论什么呢

63

00:03:02,170 --> 00:03:07,220

网易公开课下载

网易公开课频道:课程汇总(2011.4.9更新)更多见

网易公开课耶鲁大学公开课《1871年后的法国》下载地址

网易公开课《耶鲁:旧约全书导论》[中英双语字幕]视频下载

网易公开课《耶鲁:文学理论导论》[中英双语字幕]视频下载

网易公开课《耶鲁大学: 弥尔顿》[中英双语字幕]视频下载

网易公开课耶鲁大学公开课《1945年后的美国小说》[中英双语字幕]视频下载

网易公开课《耶鲁大学:金融市场》[中英双语字幕]视频下载

网易公开课《耶鲁大学哲学:死亡》[中英双语字幕]视频下载

网易公开课麻省理工公开课《音乐的各种声音》下载地址

网易公开课《麻省理工:电影哲学》[中英双语字幕]视频下载视频下载

网易公开课《普林斯顿大学:人性》[中英双语字幕]视频下载

网易公开课《斯坦福:抽象编程》[中英双语字幕]视频下载

网易公开课斯坦福大学公开课《商业领袖和企业家》[中英双语字幕]视频下载

网易公开课-哈佛大学公开课《公正》【全译】下载地址

网易公开课-普林斯顿大学公开课《领导能力简介》【全译】下载地址

网易公开课-斯坦福大学公开课《编程方法学》下载地址

网易公开课-斯坦福大学公开课《7个颠覆你思想的演讲》【全译】下载地址

网易公开课-宾夕法尼亚大学沃顿商学院公开课《沃顿的学问》下载地址

网易公开课-亚琛工业大学公开课《机械制造》下载地址。

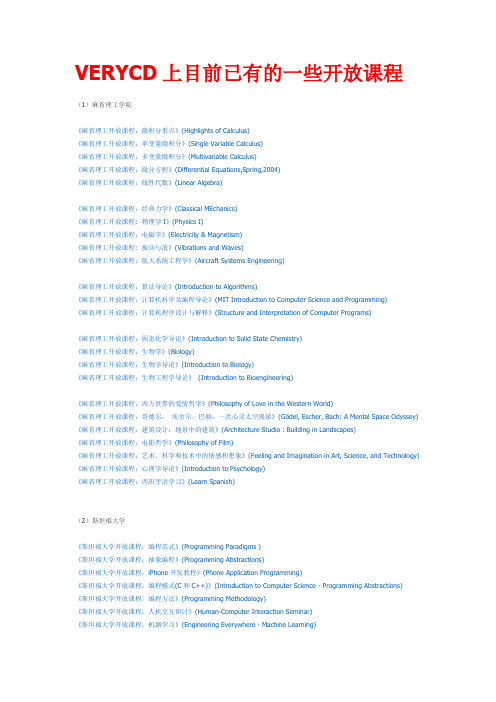

VERYCD上目前所有的 哈佛耶鲁等世界名校 网络公开课程视频下载资源

VERYCD上目前已有的一些开放课程(1)麻省理工学院《麻省理工开放课程:微积分重点》(Highlights of Calculus)《麻省理工开放课程:单变量微积分》(Single Variable Calculus)《麻省理工开放课程:多变量微积分》(Multivariable Calculus)《麻省理工开放课程:微分方程》(Differential Equations,Spring,2004)《麻省理工开放课程:线性代数》(Linear Algebra)《麻省理工开放课程:经典力学》(Classical MEchanics)《麻省理工开放课程: 物理学I》(Physics I)《麻省理工开放课程:电磁学》(Electricity & Magnetism)《麻省理工开放课程: 振动与波》(Vibrations and Waves)《麻省理工开放课程:航天系统工程学》(Aircraft Systems Engineering)《麻省理工开放课程:算法导论》(Introduction to Algorithms)《麻省理工开放课程:计算机科学及编程导论》(MIT Introduction to Computer Science and Programming)《麻省理工开放课程:计算机程序设计与解释》(Structure and Interpretation of Computer Programs)《麻省理工开放课程:固态化学导论》(Introduction to Solid State Chemistry)《麻省理工开放课程:生物学》(Biology)《麻省理工开放课程:生物学导论》(Introduction to Biology)《麻省理工开放课程:生物工程学导论》(Introduction to Bioengineering)《麻省理工开放课程:西方世界的爱情哲学》(Philosophy of Love in the Western World)《麻省理工开放课程:哥德尔,埃舍尔,巴赫:一次心灵太空漫游》(Gödel, Escher, Bach: A Mental Space Odyssey)《麻省理工开放课程:建筑设计:地景中的建筑》(Architecture Studio : Building in Landscapes)《麻省理工开放课程:电影哲学》(Philosophy of Film)《麻省理工开放课程:艺术、科学和技术中的情感和想象》(Feeling and Imagination in Art, Science, and Technology)《麻省理工开放课程:心理学导论》(Introduction to Psychology)《麻省理工开放课程:西班牙语学习》(Learn Spanish)(2)斯坦福大学《斯坦福大学开放课程:编程范式》(Programming Paradigms )《斯坦福大学开放课程:抽象编程》(Programming Abstractions)《斯坦福大学开放课程:iPhone开发教程》(Phone Application Programming)《斯坦福大学开放课程:编程模式(C和C++)》(Introduction to Computer Science - Programming Abstractions)《斯坦福大学开放课程:编程方法》(Programming Methodology)《斯坦福大学开放课程:人机交互研讨》(Human-Computer Interaction Seminar)《斯坦福大学开放课程:机器学习》(Engineering Everywhere - Machine Learning)《斯坦福大学开放课程:机器人学》(Introduction to robotics)《斯坦福大学开放课程:傅立叶变换及应用》(The Fourier Transform and Its Applications )《斯坦福大学开放课程:近现代物理专题课程-宇宙学》(Modern Physics - Cosmology)《斯坦福大学开放课程:近现代物理专题课程-经典力学》(Modern Physics - Classical Mechanics)《斯坦福大学开放课程:近现代物理专题课程-统计力学》(Modern Physics - Statistic Mechanics)[《斯坦福大学开放课程:近现代物理专题课程-量子力学》(Modern Physics - Quantum Mechanics)《斯坦福大学开放课程:近现代物理专题课程-量子纠缠-part1》(Modern Physics - Quantum Entanglement, Part 1)《斯坦福大学开放课程:近现代物理专题课程-量子纠缠-part3》(Modern Physics - Quantum Entanglement, Part 3)《斯坦福大学开放课程:近现代物理专题课程-广义相对论》(Modern Physics - Einstein's Theory)《斯坦福大学开放课程:近现代物理专题课程-狭义相对论》(Modern Physics - Special Relativity)《斯坦福大学开放课程:线性动力系统绪论》(Introduction to Linear Dynamical Systems)《斯坦福大学开放课程:经济学》(Economics)《斯坦福大学开放课程:商业领袖和企业家》(Business Leaders and Entrepreneurs)《斯坦福大学开放课程:法律学》(Law)《斯坦福大学开放课程:达尔文的遗产》(Darwin's Legacy)《斯坦福大学开放课程:人类健康的未来:七个颠覆你思想的演讲》(The Future of Human Health: 7 Very Short Talks That Will Blow Your Mind)《斯坦福大学开放课程:迷你医学课堂:医学、健康及科技前沿》(Mini Med School:Medicine, Human Health, and the Frontiers of Science)《斯坦福大学开放课程:迷你医学课堂:人类健康之动态》(Mini Med School : The Dynamics of Human Health)(3)耶鲁大学《耶鲁大学开放课程:基础物理》(Fundamentals of Physics)《耶鲁大学开放课程:天体物理学之探索和争议》(Frontiers and Controversies in Astrophysics)《耶鲁大学开放课程:新生有机化学》(Freshman Organic Chemistry )《耶鲁大学开放课程:生物医学工程探索》(Frontiers of Biomedical Engineering)《耶鲁大学开放课程:博弈论》(Game Theory)《耶鲁大学开放课程:金融市场》(Financial Markets )《耶鲁大学开放课程:文学理论导论》(Introduction to Theory of Literature )《耶鲁大学开放课程:现代诗歌》(Modern Poetry)《耶鲁大学开放课程:1945年后的美国小说》(The American Novel Since 1945)《耶鲁大学开放课程: 弥尔顿》(Milton)《耶鲁大学开放课程:欧洲文明》(European Civilization )《耶鲁大学开放课程:旧约全书导论》(Introduction to the Old Testament (Hebrew Bible) )《耶鲁大学开放课程:新约及其历史背景》(Introduction to New Testament History and Literature)《耶鲁大学开放课程:1871年后的法国》(France Since 1871)《耶鲁大学开放课程:古希腊历史简介》(Introduction to Ancient Greek History )《耶鲁大学开放课程:美国内战与重建,1845-1877》(The Civil War and Reconstruction Era,1845-1877)《耶鲁大学开放课程:全球人口增长问题》(Global Problems of Population Growth)《耶鲁大学开放课程:进化,生态和行为原理》(Principles of Evolution, Ecology, and Behavior )《耶鲁大学开放课程:哲学:死亡》(Philosophy:Death)《耶鲁大学开放课程:政治哲学导论》(Introduction to Political Philosophy)《耶鲁大学开放课程:有关食物的心理学,生物学和政治学》(The Psychology, Biology and Politics of Food) 《耶鲁大学开放课程:心理学导论》(Introduction to Psychology)《耶鲁大学开放课程:罗马建筑》(Roman Architecture)《耶鲁大学开放课程:聆听音乐》(Listening to Music)(4)哈佛大学《哈佛大学开放课程:哈佛幸福课》(Positive Psychology at Harvard)《哈佛大学开放课程:公正:该如何做是好?》(Justice: What's the Right Thing to Do? )《哈佛大学开放课程:构设动态网站》(Building Dynamic Websites)(5)牛津大学《牛津大学开放课程:尼采的心灵与自然》(Nietzsche on Mind and Nature)《牛津大学开放课程:哲学概论》(General Philosophy)《牛津大学开放课程:哲学入门》(Philosophy for Beginners)《牛津大学开放课程:批判性推理入门》(Critical Reasoning for Beginners)(6)其它名校《普林斯顿大学开放课程:人性》(InnerCore)《普林斯顿大学开放课程:自由意志定理》(The Free Will Theorem)《剑桥大学开放课程:人类学》(Anthropology)《沃顿商学院开放课程:沃顿知识在线》(Knowledge@Wharton)《哥伦比亚大学开放课程:房地产金融学I》(Real Estate Finance I)附录二部分英美名校开放课程网站美国1. 麻省理工学院/index.htm2. 卡内基梅隆大学/openlearning/forstudents/freecourses3. 约翰霍普金斯大学彭博公共卫生学院/4. 斯坦福大学/5. 圣母大学/courselist6. 杜克大学法律中心的公共领域/cspd/lectures7. 哈佛医学院/public/8. 普林斯顿大学/main/index.php9. 耶鲁大学/10. 加州大学伯克利分校英国1. 牛津大学的文字资料馆2. Greshem学院/default.asp3. 格拉斯哥大学/downloads.html4. 萨里大学/Teaching/5. 诺丁汉大学/6. 剑桥大学播客/main/Podcasts.html参考资料:/thread-42142-1-1.html。

耶鲁大学开放课程—哲学:死亡.02.Open.Yale.course—Philosophy:Death.DivX-YYeTs人人影视 [字幕转换助手

The answer to that ought to be pretty obvious.

很明显 答案是否定的

Well, obviously, the answer to that is no.

再换个问法 如果生命已经消逝了

After all, if we're saying once you've run out of life,

我能幸免于死吗

Do I survive my death?

我们能幸免于死吗

Do we survive our deaths?

首先

You think, the first thing

我们要明白人究竟是什么

we have to get clear on is well what am I?

就必须弄清楚这两个问题

we do need to get clear about both of those questions

这就是头几周课的主要内容

and so that's going to take the first several weeks of the class.

我们会花两周的时间讨论

大致意思是

The objection basically says:

我们所说的"人死了"是什么意思

What does it mean to say that somebody's died?

我们问的是 死后能否继续活着

We're asking, "Is there life after death?"

国外顶尖大学公开课程下载地址

大学生的国外培训班—耶鲁大学开放课程为什么这就叫培训班了呢?这是美国耶鲁大学的课堂实录,我们平时学的都是在自己学校的课堂里学习,相对而言知识面还是太窄了,我很想看看国外的课堂,看看他们的课堂是如何进行的,他们的讲解又有哪些独到之处?但是要去到国外进行切身感受很不实际,经费我们承担不起,但是这张小小的光盘却给了我开阔视野和充电的机会,”“你别看这张小小的DVD光盘,它的内容很充实,很经典。

能够真正让我我们都是在一家叫“顶尖大学公开课”--/ 的网店购买的,里面全部是耶鲁大学的开放课程,专业课程原版DVD10几元可直接加QQ1557822570专服务于网速不够快,或者工作繁忙,无国外大学公开课程网址~珍贵资源,好好利用哈,o(∩_∩)o...一、伯克利加州大学伯克利分校/courses.php作为美国第一的公立大学,伯克利分校提供了,可以跟踪最新的讲座。

想看教授布置的作业和课堂笔记,可以点击该教授的网页,通常,他/她都会第一堂课留下网址。

实在不行,用google搜搜吧!伯克利的视频都是.rm格式,请注意转换院麻省理工是免费开放教育课件的先驱,计划在今年把1800门课程的课件都放立了镜像网站,把麻省的课程都翻译成立中文。

鉴于PDF格式,推荐使用FoxItReader。

(中国大陆)推荐得了100分,卡耐基梅隆也不会给你开证明,更不会给你学分。

四、犹他犹他大学/front-page/Courese_listing犹他大学类似于麻省理工,提供大量的课程课件五、塔夫茨塔夫茨大学塔夫茨大学也是“开放式教育课程”的先驱之一,初期提供的课程着重在本校专础理论。

英国公开大学/course/index.php社区中,大家发表意见,提供其他的学习资源,互相取经。

在这个网站里,最能一分钱,便能通过网站获得该校的前沿知识。

约翰霍普金斯提供了本学院最受欢迎的课程,包括青少年健康、行为和健康、生物统计学、环境、一般公共卫生、卫生政策、预防伤害、母亲和儿童健康、心理卫生、营养、人口科学、公共卫生准备和难民卫生等。

耶鲁大学开放课程—哲学:死亡

中文名: 耶鲁大学开放课程—哲学:死亡英文名: Open Yale course—Philosophy:Death资源格式: RMVB版本: [YYeTs人人影视出品][中英双语字幕][更新到20集] 发行日期: 2009年8月4日地区: 美国对白语言: 英语文字语言: 简体中文,英文简介:课程类型:哲学独立字幕下载:/listsubtitle.html课程介绍:这次讲课的教授是个大仙.他那么"朴素",我是说他的坐姿那么朴素,因为人类自古就是那样坐的,盘腿坐.不过他是盘腿坐在讲台上,这就不是很朴素了,因为古代没有桌子,大家都坐在地上。

我大学的时候,美国老师屁股一扭坐在课桌或讲台上,我们这些有着“师道尊严”的中国人是很“友邦惊诧”的,但时间长了就习惯了。

英国人不这样,他们总那么严谨严肃,有点象中国人——但千万别真的以为英国人象中国人,与其说英国人与中国人象,不如说美国人与中国人更象一些:都很粗俗豪放,并且中国与美国越来越象了。

这老师穿着鞋子直接盘腿坐在讲台上,还好他穿的球鞋很白很干净,不太碍眼。

他长得有点象撒达姆大叔,还满脸胡须,但他个子很小,所以他要坐在桌子上才能显眼一些,台下据说有150-180名学生,是个大教堂,要我个子那么小我也“坐”桌子上。

他常说,we are sitting here to ...,确实彼此都“坐着”,很平等。

相比古代的大师,比如柏拉图或佛都是如此随意开讲座谈生死的吧。

看着他那样手舞足蹈的乱说一气,我觉得很舒服。

这大叔一定是个很怪的人,这从一开课就看出来了。

不过不会特别怪,因为这里毕竟是耶鲁,我是说,假如他有精神病啊什么的偏差,心理学院的老师们肯定就早就派上用场了。

他一上来就说,别管我叫什么什么“教授”,我喜欢听你们叫我shelly。

从他的简历看,他应该是个伦理学专家,写过一些这方面的书籍。

今天香港著名艺人肥姐逝世,这就是活生生的死亡。

死亡对普通人意味着什么?死亡对哲学家又意味着什么?实际上讲死亡的哲学就是在讲哲学家们如何看待死亡。

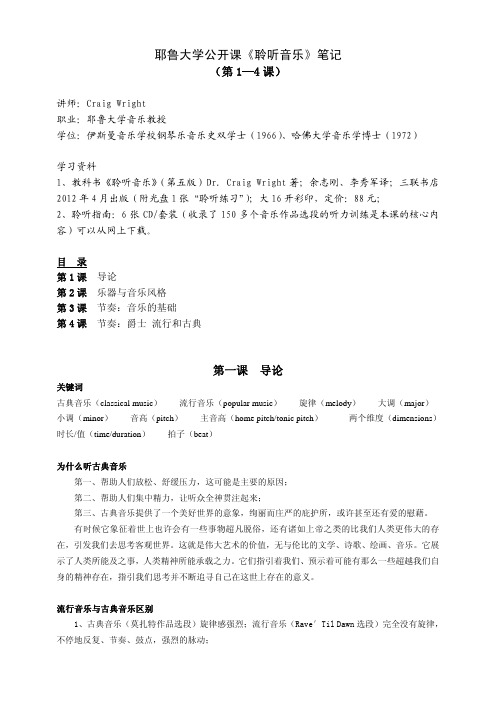

耶鲁大学《聆听音乐》公开课笔记(1-4课)PDF版

耶鲁大学公开课《聆听音乐》笔记(第1—4课)讲师:Craig Wright职业:耶鲁大学音乐教授学位:伊斯曼音乐学校钢琴乐音乐史双学士(1966)、哈佛大学音乐学博士(1972)学习资料1、教科书《聆听音乐》(第五版)Dr. Craig Wright著;余志刚、李秀军译;三联书店2012年4月出版(附光盘1张“聆听练习”);大16开彩印,定价:88元;2、聆听指南:6张CD/套装(收录了150多个音乐作品选段的听力训练是本课的核心内容)可以从网上下载。

目 录第1课 导论第2课 乐器与音乐风格第3课 节奏:音乐的基础第4课 节奏:爵士 流行和古典第一课 导论关键词古典音乐(classical music)流行音乐(popular music)旋律(melody)大调(major)小调(minor)音高(pitch)主音高(home pitch/tonic pitch)两个维度(dimensions)时长/值(time/duration)拍子(beat)为什么听古典音乐第一、帮助人们放松、舒缓压力,这可能是主要的原因;第二、帮助人们集中精力,让听众全神贯注起来;第三、古典音乐提供了一个美好世界的意象,绚丽而庄严的庇护所,或许甚至还有爱的慰藉。

有时候它象征着世上也许会有一些事物超凡脱俗,还有诸如上帝之类的比我们人类更伟大的存在,引发我们去思考客观世界。

这就是伟大艺术的价值,无与伦比的文学、诗歌、绘画、音乐。

它展示了人类所能及之事,人类精神所能承载之力。

它们指引着我们、预示着可能有那么一些超越我们自身的精神存在,指引我们思考并不断追寻自己在这世上存在的意义。

流行音乐与古典音乐区别1、古典音乐(莫扎特作品选段)旋律感强烈;流行音乐(Rave′Til Dawn选段)完全没有旋律,不停地反复、节奏、鼓点,强烈的脉动;2、古典音乐的演奏乐器发出的声音与流行乐的合成音效是截然不同的。

音乐是一种听觉感知的呈现,你不可能像对待英语或历史考试那样,在考试前一天晚上将音乐中的信息或声音死记硬背以便应付考试。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

《耶鲁大学开放课程:有关食物的心理学,生物学和政治学》

《耶鲁大学开放课程:美国内战与重建,1845-1877》

《耶鲁大学开放课程:天体物理学之探索和争议》

《耶鲁大学开放课程:进化,生态和行为原理》

《耶鲁大学开放课程:金融市场》

《耶鲁大学开放课程:罗马建筑》

《耶鲁大学开放课程: 解读但丁》

《耶鲁大学开放课程:聆听音乐》

《耶鲁大学开放课程:基础物理》

《耶鲁大学开放课程:博弈论》

《iPhone开发教程》

《编程模式(C和C++)》

《抽象编程》

《人机交互研讨》

《编程方法学》

《经济学》

《人类健康之动态》

《医学、健康及科学前沿》

《数字通信原理》

TTC开放课程:

《经济学第3版》(TTC )

《全球化与爱情》

《激情:感情的哲学与智慧教程》

《21世纪的乌托邦及其恐怖行为》

《莎士比亚》

教育频道名校课程推荐课程(含世界多所知名大学及研究院的课程)

麻省理工大学开放课程:

《MIT计算机科学及编程导论》

《算法导论》

《生物学导论》

《固体化学导论》

《电磁学》

《经典力学》

《脑与认知科学》

《电机工程与计算机科学》

《耶鲁大学开放课程: 政治哲学导论》

《耶鲁大学开放课程:心理学导论》

《耶鲁大学开放课程—哲学:死亡》

《耶鲁大学开放课程: 现代诗歌》

《人性》

牛津大学开放课程:

《尼采的心灵与自然》

《哲学概论》

《哲学入门》

《批判性推理入门》

剑桥大学开放课程:

《人类学》

沃顿商学院开放课程:

《沃顿知识在线》

斯坦福大学开放课程:

《耶鲁大学开放课程:古希腊历史简介》

《耶鲁大学开放课程:新生有机化学》

《耶鲁大学开放课程:文学理论导论》

《耶鲁大学开放课程:旧约全书导论》

..................▍ ... ..顺. ★

................. ▍.万 事 如 意. ☆

..................▍☆ .★ .☆ .★. ☆

..................▍

..▍∵ ☆ ★...▍▍....█▍ ☆ ★∵▍..

◥█▅▅

英文字幕为每个MOV视频内嵌字幕,官方原版,一字不差。

中文字幕也已经发上来,下面的srt文件即为中文字幕

目前已知的可调出中英文双字幕的播放器有:KMP播放器

调出字幕的大致步骤为: 播放视频,在画面上右键单击,选择下拉选项中的“字幕”,然后在弹出的下拉选项中选择“字幕语言”,选定英文字幕,然后再在“字幕语言”下拉选项中的“次字幕”中选择中文字幕。

字幕显示位置用 ctrl加】或【进行调整。

目前已知的不可调出字幕的播放器有:暴风影音,迅雷看看,快播

..................▍..★

..................▍.一 .☆

................. ▍ ..帆. ★

..................▍ ... 风. ☆

《耶鲁大学开放课程:1945年后的美国小说》

《耶鲁大学开放课程:生物医学工程探索》

《耶鲁大学开放课程:新约及其历史背景》

《耶鲁大学开放课程:全球人口增长问题》

整套视频由 栖息谷@PO 整理出品!需要的请登陆:

/凌晓兵/blog/item/9d52363370e1dfa75fdf0e6e.html

QQ:1367972606

全套73科目,每个科目10——40个视频课程,每课45分钟左右,大部分课程含中英文双字幕,视频内嵌,部分英文字幕,有些课程须外挂字幕。

《耶鲁大学开放课程: 弥尔顿》

《我为什么选择耶鲁》

哈佛大学开放课程: Βιβλιοθήκη 《幸福》 《公正》

普林斯顿大学开放课程:

《领导能力简介》

《国际座谈会》

《自由意志定理》

《技术世界的领导能力》

《力学》

《狭义相对论》

《广义相对论》

《统计力学》

《宇宙学》

《量子纠缠1》

《量子纠缠2》

《线性动力系统教程》

《JOBS演讲》