Clarke_corporate governace in china_2003

中国公司治理(外文期刊翻译)

中国公司治理:现代视角Corporate governance in China: A modern perspective Corporate governance in China: A modern perspective☆Fuxiu Jiang, Kenneth A. Kim ⁎School of Business, Renmin University of China, 59 Zhongguancun Street, Haidian District, Beijing, China 100872近年来,许多使用中国金融数据的学术论文发表在领先的学术期刊上。

这一增长这并不奇怪,因为中国是一个转型经济大国,正在从计划经济转向市场经济,现在已经成为世界第二大经济体。

简单地说,中国是有趣和重要的。

然而,一些研究中国的缺点。

首先,考虑到大多数现代金融理论都起源于西方,尤其是美国,因此有很多研究中国的论文使用西方理论和概念来解释他们的实证发现。

2 . However, while it may sometimes be从西方的角度来看待中国的实证结果是恰当的,但在其他时候则不然。

其次,许多报纸似乎都是如此误解(或没有意识到)重要的监管问题;法律、金融和制度环境;和业务中国的风俗习惯。

第三,许多研究中国的论文,即使是最近发表的,现在已经过时了。

的中国过去20年的经济增长是爆炸式的。

在这段时间里,发生了许多变化地方,包括许多监管的变化和引入新的规则,影响公司治理在中国。

鉴于这些不足之处,本文的主要目的有两个:(一)对公司治理现状进行概述(二)指出和探讨公司治理在很大程度上是中国所特有的特点在本期特刊中,我们将为大家提供一个更新的中国公司治理观。

因此,我们也重要的是在适当的地方描述这些论文。

本文的其余部分如下。

在第二部分,我们提供了重要的制度背景资料的中国并讨论了中国公司治理的制度和监管环境。

在第三节,我们提供并讨论与公司治理相关的重要变量的汇总统计。

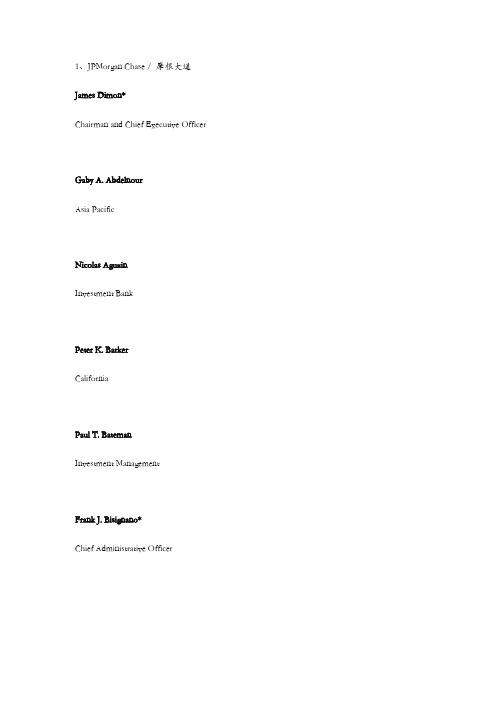

已入驻中国的福布斯全球企业500强及联系方式

1、JPMorgan Chase / 摩根大通James Dimon*Chairman and Chief Executive OfficerGaby A. AbdelnourAsia PacificNicolas AguzinInvestment BankPeter K. BarkerCaliforniaPaul T. BatemanInvestment ManagementFrank J. Bisignano*Chief Administrative OfficerSteven D. Black*Vice ChairmanPhilip F. Bleser Corporate BankingDouglas L. Braunstein* Chief Financial OfficerClive S. Brown Investment ManagementPhyllis J. Campbell Pacific NorthwestRichard M. Cashin One Equity PartnersMichael J. Cavanagh* Treasury & Securities ServicesGuy Chiarello TechnologyMichael J. ClearyRetail Financial ServicesAndrew D. Crockett JPMorgan Chase InternationalStephen M. Cutler*Legal & ComplianceWilliam M. Daley* Corporate ResponsibilityKimberly B. Davis PhilanthropyKlaus Diederichs Investment BankPhil Di IorioAsset ManagementJohn L. Donnelly* Human ResourcesIna R. Drew*Chief Investment OfficerAlthea L. Duersten Chief Investment OfficeMary Callahan Erdoes* Asset ManagementJoseph M. Evangelisti Corporate CommunicationsDr. Jacob A. Frenkel JPMorgan Chase InternationalMartha J. GalloAuditWalter A. GubertEurope, Middle East and AfricaGregory L. Guyett InternationalCarlos M. Hernandez Investment BankJohn J. HoganInvestment Bank/Risk ManagementCatherine M. KeatingAsset ManagementConrad J. KozakWorldwide Securities ServicesJames B. Lee, Jr.Investment BankDavid B. LowmanHome LendingSamuel Todd Maclin*Commercial BankingAchilles O. MacrisChief Investment OfficeJay Mandelbaum*Strategy & MarketingMel R. MartinezFlorida, Mexico, Central America and CaribbeanBlythe S. MastersInvestment BankDonald H. McCree, IIITreasury & Securities ServicesRyan McInerney Retail Financial ServicesHeidi Miller* InternationalMelissa J. MooreRiskStephanie B. Mudick Consumer PracticesMichael O'Brien Asset ManagementNicholas P. O'Donohoe Investment BankDaniel E. PintoInvestment BankScott E. PowellBanking and Consumer Lending OperationsLouis RauchenbergerControllerRichard SaboChief Investment OfficeEmilio SarachoInvestment BankCharles W. Scharf*Retail Financial ServicesPeter L. ScherGlobal Government Relations & Public PolicyEileen M. SerraCard ServicesMarc SheinbaumAuto & Education FinanceBarry SommersRetail Financial ServicesGordon A. Smith*Card ServicesJames E. Staley*Investment BankJack M. Stephenson Strategy & MarketingJeffrey J. Urwin Investment BankWilliam S. Wallace Card ServicesKevin P. Watters Retail Financial ServicesKevin D. Willsey Investment BankDouglas Wurth Asset ManagementMatthew E. ZamesInvestment BankBarry L. Zubrow*Chief Risk OfficerAnthony J. HoranSecretaryLauren M. TylerInvestor RelationsNorma C. CorioTreasurercall 1-212-270-6000.摩根大通银行(中国)有限公司JPMorgan Chase Bank (China) Company Limited 中国Lisa Liang (lisa.lh.liang@),市场传讯部中国负责人Frances Fu (Frances.x.fu@)电话:+86 10 59318888(中国)。

治理:工具理性还是价值理性

治理:工具理性还是价值理性?---李峰自1989年世界银行首次使用“治理危机”(crisis ingovernance)来概括当时非洲的发展情形以来,“治理”一词在社会科学界被大量使用,从政治学、社会学、公共政策学到国际关系等学科,所涉及的领域不断扩大,有地区层面、国家层面并延伸至国际合作,所涉及的主体包罗万象,有政府组织、非政府组织到市场组织。

然而国际学术界关于治理理论的内容表述却莫衷一是、混乱不堪。

英国学者罗茨就指出了治理的六种用法,即作为最小国家、作为公司治理、作为新公共管理、作为善治(Good Governance)、作为社会控制系统和作为自组织网络([英)罗伯特?罗茨:《新的治理》,选自俞可平主编:《治理与善治》,社会科学文献出版社2000年版,第87页)。

英国学者鲍勃?杰索普(Bob Jessop)对这种状况作了很好的描绘,他认为“治理在许多语境中大行其道,以致成为一个可以指涉任何事物或毫无意义的‘时髦词语’。

”“即便现在,它在社会科学界的用法仍然常常是‘前理论式的’,而且莫衷一是。

”([英)鲍勃?杰索普:《治理的兴起及其失败的风险:以经济发展为例的论述》,选自俞可平主编:《治理与善治》,社会科学文献出版社2000年版,第53、55页。

)行笔于此,笔者想起了一件事,当我向美国加利福尼亚州立大学公共行政学系的迈克尔?克拉克(Michael Clarke)教授求教治理的有关问题时,他竟不知晓治理理论(Governance The-ory)所指何物。

所以,尽管世界银行、国际货币基金组织等不遗余力地在推进全球治理,不管其在实践中效果如何,其价值取向怎样,但从学理层面上讲,治理理论在国外远没有发展成为一种成熟、系统的理论。

反观国内,自上世纪90年代末以来,有关治理方面的书籍、文章不断问世。

中国的学者在译介西方治理理论的基础上,对治理兴起的背景、治理的含义,全球治理等问题进行了广泛的探讨,特别值得关注的是,许多学者将治理理论同中国的改革实践联系起来,来探讨中国走向善政的路径。

麦肯锡咨询公司

请记住,如果 面试成功,您 将会在这里与 这些人一起工 作。即使您通 过伪饰的方法 通过了面试, 也无法在今后 的日子里长久 蒙骗下去。

请想想那些 能够表现您 您 的领导能力、 的领导能力、 个人能动性 或个人影响 力,或者能 够综合体现 以上能力的 事情。

可以向面试 向 官询问有关 他们的背景、 他们的背景、 工作和工作 动力方面的 问题。 问题。

再经过2年左右考 核升至资深项目经 理,这是晋升董事 的前身;.

此后,通过业绩审 核可升为董事。一 个勤奋、有业绩的 人在6—7 年里可 以升为麦肯锡董事 。

但是在他每一个晋升的阶段,如果业绩考核并未达到要求,就要被OUT(离 开麦肯锡)。

McKinsey&Company

McKinsey&Company

1

工作能力强,工作热情 高。

2

工作能力低,工作热情 高。

3

工作能力强,工作热情 低。

4

工作能力低,工作热情 。

采取重用,鼓励政 策

采取培训或调 用 的策略

勿留

解雇

宁要能力不强,顺从公司文化的人,可千万不要留那种能力似乎很强, 总想不顺从公司文化而素质较差的人。

McKinsey&Company

面试流程

对我们来说,重要的 不仅仅是您取得的成 绩,还有您取得这些 您取得这些 成绩时所使用的技能 。 我们的面试官希 望通过深入分析您过 去所取得的成就,来 确定您所拥有的技能 是否能使您在麦肯锡 的职业生涯走向辉煌 。

面试技巧

展示真实的自己 细节也有价值 面试官是什么 人?

相互了解

每次面试时, 在开展案例分 析前,面试官 总会要求您利 用10到15分 钟的时间进行 自我介绍。 这听起来很简 单,但实践 实践证 实践 明其实大有讲 其实大有讲 究。

China’s_Digital_Economy

18China’s Digital Economy:A Leading Global ForceBy Nikki Liu“China is already standing at the global center of the digital economy”, said Jonathan Woetzel, the Director of the McKinsey Global Institute and a senior managing partner worldwide. According to a report by MGI entitles “China’s digital economy: A leading global force”, China has the most digital technology investors, adopters and unicorns in the world. The report also points out the three main reasons for the rapid development of China’s digital economy: a large potential market, giant companies with affluent capital and plenty of space for investors to play.China has one third of the world ’s unicorns“The digital transformation in China has aexerted profound effect on its economy and will further influence the digitization process of the world”, said Woetzel. During 2005, China’s e-commerce reta i l sa les volume accounted for less than 1% of the global transaction volume; however, that number exceeded 40% in 2016, and was two times that of the transaction volume in the U nited States and far more than that of France, Germany, Japan and Britain combined. Early investors in e-commerce have been rewarded with returns thousands of times higher than their investment.It was revealed in the report that the penetration rate of mobile payments among Chinese internet users has jumped from 25% in 2013 to 68% within three years. Personal consumption through mobile payments amounted to USD 790 billion in 2016, which is 10 times more than the transaction value of same in the United States. One in three of the world’s 262 unicorns is Chinese, commanding 43 percent of the global value of all unicorns, among which internet giants like Baidu, Alibaba,and Tencent are exerting significant influence across the globe.Besides this, China’s venture capital industry has been undergoing fast growth. In the period of 2011 to 2013, the venture capital volume in China was only USD 12 billion, but that increased by 5.42 times and reached USD 77 billion during the period of 2014 to 2016, showing a rise from 6% of the total venture capital investment to 19%. The Chinese venture capital industry mainly concentrates on digital technology like big data, artificial intelligence, fintech, etc.Over the past two years, China’s top 3 Internet companies (the BAT companies) made 35 overseas deals, among which Tencent, with U SD 8.6 billion, took over 84.3% shares of Supercell, a well-known mobile game manufacturer, which commands more than 10% of the global game revenue. Alibaba invested U SD 1 billion and purchased a leading e-commerce platform Lazada in Southeast Asia which, with 650 million clients, holds the first place in e-commerce markets amongthe six major Southeast Asian nations. Bike sharing companies like ofo and Mobike use GPS in their apps to locate and unlock stationary bicycles and have already expanded their business to Japan, Singapore, Britain and the United States.Jonathan Woetzel expressed that China had one of the most active digital-investment and start-up ecosystems in the world. China has already become a global leader in the customer-driven digital economy after stopping imitating the West and focusing on innovation by making the best use of their largest homeland market and abundant risk investment funds.A warning for monopoly disputesFrom 2015 to 2017, government work reports haveincluded key concepts like “internet plus”, “sharing economy” and “digital economy” in succession, w h ic h d e m o n s t r a t e s t h e r a p i d development momentum of China’s digital economy. However, monopoly disputes in this field still occurred at19home and abroad, for example, the conflict over data between SF Express and Cainiao, as well as the competition b e t w e e n J D.c om a nd A l ib a b a. Furthermore, across the world, the European U nion has imposed an antitrust penalty of U SD 2.42 billion on Google, the largest ever fine levied against a single company.According to a Senior Partner of Dentons, Deng Zhisong, there are four main characteristics of the digital economy. Firstly, data is the core of competition and could usher in a new era. Secondly, the platform is an essential part of the media for competition. The three internet giants — (Facebook, Amazon, and Google) in the U nited States are respectively used for social contact, e-commerce and searching, just like the BAT companies in China.“This is by no means a coincidence. The purpose of establishing platforms is to collect users’ data and allow for direct market competition,” claimed Deng Zhisong.Thirdly, cross-border transmission is the competition model. Transmission was first brought up in the case of Coca-Cola’s purchase of Huiyuan. The Chinese Ministry of Commerce believes that the dominating cross-market transmission is a form of anti-competitive conduct.“There is plenty of evidence,” said Deng Zhisong. A “war” was triggered between Qihoo 360 and Tencent (known as the 3Q battle) when Tencent launched its QQ consulting app, a conflict between Cainiao and SF Express over data also arose when Alibaba intervened in the logistics industry, and the European Union has been conducted an investigation since 2010 into Google, which abused its search service to promote other services.Lastly, oligarchs possess a larger share of the market, with winners often taking all the benefits. The Internet is considered to reinforce this situation.Working against monopolies is undoubtedly essential in regulating market competition, and would not be influenced by dynamic competition, elusiveness, artificial intelligence and big data, but may instead intensify competitive damage instead. Deng Zhisong pointed out that there islegislation regarding the protection of big data which includes the Consumer Protection Law amended in 2014, the Cyber-Safety Act, The Criminal Code and judicial interpretations given by superior court and superior pro c u r ator ate. How e v er, t he s e documents are not always efficient, especially when applied to special cases. In the market, ambiguities still exist in the definition of some key concepts,such as platform, bilateral, multilateral and cross-border competition, and cross-border transmission.Deng agreed that identifying abuse regarding dominance in market can be quite technical, exclusive and highly dynamic, thus requiring more evidence. This poses great challenges to law enforcement agencies regarding their abilities to process data and evidence.“The digital economy also makes things more difficult in terms of discerning anti-trust agreements,” said Deng Zhisong. He pointed out that in 2015, the Department of Justice of the United States investigated and punished Amazon for its sales of posters, which was the first case of an anti-monopoly agreement based on an algorithm. This happened when Amazon used an algorithm to maintain a high price in its sales of posters without any consultation and contact with labor forces, revealing a future trend.Being proactive when faced with the challenges aheadAccompanied by the growth and application of global Internet technology, a closer tie has been forged between the Internet and the economic industry. The industry has undergone a transformation and upgrading, business modelsare continua l ly being reformed and innovated, and a new digital economy based on the Internet has sprung up. However, there is an increasing number of economic conf licts and illegal competition between enterprises.“Obstacles in the way to developing the digital economy remain to be solved and require efforts from different parties.” Si Xiao, the Dean of the Tencent Research Institute, claims that the situation regarding the digital gap is quite austere, and not only includes the gap between infrastructure accessibility, but also that in digital literacy.In terms of accessibility, four billion people in the world still don’t have access to the Internet. The World Economic Forum has proposed an initiative to establish a network for all, and accordingly many countries have made plans to realize this goal. However, this could take a long time.A s fa r as d ig ita l l iterac y is concerned, this is a problem which paralyzes all countries. Statistics from the European Union showed that more than 47% of people from EU countries are not qualified in terms of digital literacy, which impedes the digitization process in Europe. This problem is even graver in developing countries.Si Xiao points out: “At the same time, along with the development of the digital economy, security threats arise, high risk vulnerabilities multiply and network attacks intensify. Infrastructure is under threat and can be severely damaged, especially in the areas of finance and energy.” The Internet is also confronted with unprecedented security challenges along with the development of the Internet of Things.He also expressed his concerns that “data on the one hand is an essential productive factor; but on the other hand, too much data leads to a deluge to some degree”.In addition, legal construction lags behind the healthy growth of the digital economy. Si Xiao said that a consensus hasn’t been achieved between countries on issues like protecting users’ privacy, as well astheir “right to be forgotten”. In this way, countries differ greatly in their regulatory policies regarding the digital economy and as such, conflicts between traditional industries and the new ones emerge from time to time.A senior eng ineer from the National Research Center for the Development of Industrial Information Security, Wang Hualei explained: “The government, enterprises and all circles of the society should take an active attitude towards the digitization transformation and promotingthe healthy growth of our digital economy. They should not only create a favorable environment for its development, but should also be proactive when faced with all problems that may occur during the development of the digital economy.”。

美国公司法证券法历年经典论文列表

美国是世界上公司法、证券法研究最为发达的国家之一,在美国法学期刊(Law Review & Journals)上每年发表400多篇以公司法和证券法为主题的论文。

自1994年开始,美国的公司法学者每年会投票从中遴选出10篇左右重要的论文,重印于Corporate Practice Commentator,至2008年,已经评选了15年,计177篇论文入选。

以下是每年入选的论文列表:2008年(以第一作者姓名音序为序):1.Anabtawi, Iman and Lynn Stout. Fiduciary duties for activist shareholders. 60 Stan. L. Rev. 1255-1308 (2008).2.Brummer, Chris. Corporate law preemption in an age of global capital markets. 81 S. Cal. L. Rev. 1067-1114 (2008).3.Choi, Stephen and Marcel Kahan. The market penalty for mutual fund scandals. 87 B.U. L. Rev. 1021-1057 (2007).4.Choi, Stephen J. and Jill E. Fisch. On beyond CalPERS: Survey evidence on the developing role of public pension funds in corporate governance. 61 V and. L. Rev. 315-354 (2008).5.Cox, James D., Randall S. Thoma s and Lynn Bai. There are plaintiffs and…there are plaintiffs: An empirical analysis of securities class action settlements. 61 V and. L. Rev. 355-386 (2008).6.Henderson, M. Todd. Paying CEOs in bankruptcy: Executive compensation when agency costs are low. 101 Nw. U. L. Rev. 1543-1618 (2007).7.Hu, Henry T.C. and Bernard Black. Equity and debt decoupling and empty voting II: Importance and extensions. 156 U. Pa. L. Rev. 625-739 (2008).8.Kahan, Marcel and Edward Rock. The hanging chads of corporate voting. 96 Geo. L.J. 1227-1281 (2008).9.Strine, Leo E., Jr. Toward common sense and common ground? Reflections on the shared interests of managers and labor in a more rational system of corporate governance. 33 J. Corp. L. 1-20 (2007).10.Subramanian, Guhan. Go-shops vs. no-shops in private equity deals: Evidence and implications.63 Bus. Law. 729-760 (2008).2007年:1.Baker, Tom and Sean J. Griffith. The Missing Monitor in Corporate Governance: The Directors’ & Officers’ Liability Insurer. 95 Geo. L.J. 1795-1842 (2007).2.Bebchuk, Lucian A. The Myth of the Shareholder Franchise. 93 V a. L. Rev. 675-732 (2007).3.Choi, Stephen J. and Robert B. Thompson. Securities Litigation and Its Lawyers: Changes During the First Decade After the PSLRA. 106 Colum. L. Rev. 1489-1533 (2006).4.Coffee, John C., Jr. Reforming the Securities Class Action: An Essay on Deterrence and Its Implementation. 106 Colum. L. Rev. 1534-1586 (2006).5.Cox, James D. and Randall S. Thomas. Does the Plaintiff Matter? An Empirical Analysis of Lead Plaintiffs in Securities Class Actions. 106 Colum. L. Rev. 1587-1640 (2006).6.Eisenberg, Theodore and Geoffrey Miller. Ex Ante Choice of Law and Forum: An Empirical Analysis of Corporate Merger Agreements. 59 V and. L. Rev. 1975-2013 (2006).7.Gordon, Jeffrey N. The Rise of Independent Directors in the United States, 1950-2005: Of Shareholder V alue and Stock Market Prices. 59 Stan. L. Rev. 1465-1568 (2007).8.Kahan, Marcel and Edward B. Rock. Hedge Funds in Corporate Governance and Corporate Control. 155 U. Pa. L. Rev. 1021-1093 (2007).ngevoort, Donald C. The Social Construction of Sarbanes-Oxley. 105 Mich. L. Rev. 1817-1855 (2007).10.Roe, Mark J. Legal Origins, Politics, and Modern Stock Markets. 120 Harv. L. Rev. 460-527 (2006).11.Subramanian, Guhan. Post-Siliconix Freeze-outs: Theory and Evidence. 36 J. Legal Stud. 1-26 (2007). (NOTE: This is an earlier working draft. The published article is not freely available, and at SLW we generally respect the intellectual property rights of others.)2006年:1.Bainbridge, Stephen M. Director Primacy and Shareholder Disempowerment. 119 Harv. L. Rev. 1735-1758 (2006).2.Bebchuk, Lucian A. Letting Shareholders Set the Rules. 119 Harv. L. Rev. 1784-1813 (2006).3.Black, Bernard, Brian Cheffins and Michael Klausner. Outside Director Liability. 58 Stan. L. Rev. 1055-1159 (2006).4.Choi, Stephen J., Jill E. Fisch and A.C. Pritchard. Do Institutions Matter? The Impact of the Lead Plaintiff Provision of the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act. 835.Cox, James D. and Randall S. Thomas. Letting Billions Slip Through Y our Fingers: Empirical Evidence and Legal Implications of the Failure of Financial Institutions to Participate in Securities Class Action Settlements. 58 Stan. L. Rev. 411-454 (2005).6.Gilson, Ronald J. Controlling Shareholders and Corporate Governance: Complicating the Comparative Taxonomy. 119 Harv. L. Rev. 1641-1679 (2006).7.Goshen , Zohar and Gideon Parchomovsky. The Essential Role of Securities Regulation. 55 Duke L.J. 711-782 (2006).8.Hansmann, Henry, Reinier Kraakman and Richard Squire. Law and the Rise of the Firm. 119 Harv. L. Rev. 1333-1403 (2006).9.Hu, Henry T. C. and Bernard Black. Empty V oting and Hidden (Morphable) Ownership: Taxonomy, Implications, and Reforms. 61 Bus. Law. 1011-1070 (2006).10.Kahan, Marcel. The Demand for Corporate Law: Statutory Flexibility, Judicial Quality, or Takeover Protection? 22 J. L. Econ. & Org. 340-365 (2006).11.Kahan, Marcel and Edward Rock. Symbiotic Federalism and the Structure of Corporate Law.58 V and. L. Rev. 1573-1622 (2005).12.Smith, D. Gordon. The Exit Structure of V enture Capital. 53 UCLA L. Rev. 315-356 (2005).2005年:1.Bebchuk, Lucian Arye. The case for increasing shareholder power. 118 Harv. L. Rev. 833-914 (2005).2.Bratton, William W. The new dividend puzzle. 93 Geo. L.J. 845-895 (2005).3.Elhauge, Einer. Sacrificing corporate profits in the public interest. 80 N.Y.U. L. Rev. 733-869 (2005).4.Johnson, . Corporate officers and the business judgment rule. 60 Bus. Law. 439-469 (2005).haupt, Curtis J. In the shadow of Delaware? The rise of hostile takeovers in Japan. 105 Colum. L. Rev. 2171-2216 (2005).6.Ribstein, Larry E. Are partners fiduciaries? 2005 U. Ill. L. Rev. 209-251.7.Roe, Mark J. Delaware?s politics. 118 Harv. L. Rev. 2491-2543 (2005).8.Romano, Roberta. The Sarbanes-Oxley Act and the making of quack corporate governance. 114 Y ale L.J. 1521-1611 (2005).9.Subramanian, Guhan. Fixing freezeouts. 115 Y ale L.J. 2-70 (2005).10.Thompson, Robert B. and Randall S. Thomas. The public and private faces of derivative lawsuits. 57 V and. L. Rev. 1747-1793 (2004).11.Weiss, Elliott J. and J. White. File early, then free ride: How Delaware law (mis)shapes shareholder class actions. 57 V and. L. Rev. 1797-1881 (2004).2004年:1Arlen, Jennifer and Eric Talley. Unregulable defenses and the perils of shareholder choice. 152 U. Pa. L. Rev. 577-666 (2003).2.Bainbridge, Stephen M. The business judgment rule as abstention doctrine. 57 V and. L. Rev. 83-130 (2004).3.Bebchuk, Lucian Arye and Alma Cohen. Firms' decisions where to incorporate. 46 J.L. & Econ. 383-425 (2003).4.Blair, Margaret M. Locking in capital: what corporate law achieved for business organizers in the nineteenth century. 51 UCLA L. Rev. 387-455 (2003).5.Gilson, Ronald J. and Jeffrey N. Gordon. Controlling shareholders. 152 U. Pa. L. Rev. 785-843 (2003).6.Roe, Mark J. Delaware 's competition. 117 Harv. L. Rev. 588-646 (2003).7.Sale, Hillary A. Delaware 's good faith. 89 Cornell L. Rev. 456-495 (2004).8.Stout, Lynn A. The mechanisms of market inefficiency: an introduction to the new finance. 28 J. Corp. L. 635-669 (2003).9.Subramanian, Guhan. Bargaining in the shadow of takeover defenses. 113 Y ale L.J. 621-686 (2003).10.Subramanian, Guhan. The disappearing Delaware effect. 20 J.L. Econ. & Org. 32-59 (2004)11.Thompson, Robert B. and Randall S. Thomas. The new look of shareholder litigation: acquisition-oriented class actions. 57 V and. L. Rev. 133-209 (2004).2003年:1.A yres, Ian and Stephen Choi. Internalizing outsider trading. 101 Mich. L. Rev. 313-408 (2002).2.Bainbridge, Stephen M. Director primacy: The means and ends of corporate governance. 97 Nw. U. L. Rev. 547-606 (2003).3.Bebchuk, Lucian, Alma Cohen and Allen Ferrell. Does the evidence favor state competition in corporate law? 90 Cal. L. Rev. 1775-1821 (2002).4.Bebchuk, Lucian Arye, John C. Coates IV and Guhan Subramanian. The Powerful Antitakeover Force of Staggered Boards: Further findings and a reply to symposium participants. 55 Stan. L. Rev. 885-917 (2002).5.Choi, Stephen J. and Jill E. Fisch. How to fix Wall Street: A voucher financing proposal for securities intermediaries. 113 Y ale L.J. 269-346 (2003).6.Daines, Robert. The incorporation choices of IPO firms. 77 N.Y.U. L. Rev.1559-1611 (2002).7.Gilson, Ronald J. and David M. Schizer. Understanding venture capital structure: A taxexplanation for convertible preferred stock. 116 Harv. L. Rev. 874-916 (2003).8.Kahan, Marcel and Ehud Kamar. The myth of state competition in corporate law. 55 Stan. L. Rev. 679-749 (2002).ngevoort, Donald C. Taming the animal spirits of the stock markets: A behavioral approach to securities regulation. 97 Nw. U. L. Rev. 135-188 (2002).10.Pritchard, A.C. Justice Lewis F. Powell, Jr., and the counterrevolution in the federal securities laws. 52 Duke L.J. 841-949 (2003).11.Thompson, Robert B. and Hillary A. Sale. Securities fraud as corporate governance: Reflections upon federalism. 56 V and. L. Rev. 859-910 (2003).2002年:1.Allen, William T., Jack B. Jacobs and Leo E. Strine, Jr. Function over Form: A Reassessment of Standards of Review in Delaware Corporation Law. 26 Del. J. Corp. L. 859-895 (2001) and 56 Bus. Law. 1287 (2001).2.A yres, Ian and Joe Bankman. Substitutes for Insider Trading. 54 Stan. L. Rev. 235-254 (2001).3.Bebchuk, Lucian Arye, Jesse M. Fried and David I. Walker. Managerial Power and Rent Extraction in the Design of Executive Compensation. 69 U. Chi. L. Rev. 751-846 (2002).4.Bebchuk, Lucian Arye, John C. Coates IV and Guhan Subramanian. The Powerful Antitakeover Force of Staggered Boards: Theory, Evidence, and Policy. 54 Stan. L. Rev. 887-951 (2002).5.Black, Bernard and Reinier Kraakman. Delaware’s Takeover Law: The Uncertain Search for Hidden V alue. 96 Nw. U. L. Rev. 521-566 (2002).6.Bratton, William M. Enron and the Dark Side of Shareholder V alue. 76 Tul. L. Rev. 1275-1361 (2002).7.Coates, John C. IV. Explaining V ariation in Takeover Defenses: Blame the Lawyers. 89 Cal. L. Rev. 1301-1421 (2001).8.Kahan, Marcel and Edward B. Rock. How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Pill: Adaptive Responses to Takeover Law. 69 U. Chi. L. Rev. 871-915 (2002).9.Kahan, Marcel. Rethinking Corporate Bonds: The Trade-off Between Individual and Collective Rights. 77 N.Y.U. L. Rev. 1040-1089 (2002).10.Roe, Mark J. Corporate Law’s Limits. 31 J. Legal Stud. 233-271 (2002).11.Thompson, Robert B. and D. Gordon Smith. Toward a New Theory of the Shareholder Role: "Sacred Space" in Corporate Takeovers. 80 Tex. L. Rev. 261-326 (2001).2001年:1.Black, Bernard S. The legal and institutional preconditions for strong securities markets. 48 UCLA L. Rev. 781-855 (2001).2.Coates, John C. IV. Takeover defenses in the shadow of the pill: a critique of the scientific evidence. 79 Tex. L. Rev. 271-382 (2000).3.Coates, John C. IV and Guhan Subramanian. A buy-side model of M&A lockups: theory and evidence. 53 Stan. L. Rev. 307-396 (2000).4.Coffee, John C., Jr. The rise of dispersed ownership: the roles of law and the state in the separation of ownership and control. 111 Y ale L.J. 1-82 (2001).5.Choi, Stephen J. The unfounded fear of Regulation S: empirical evidence on offshore securities offerings. 50 Duke L.J. 663-751 (2000).6.Daines, Robert and Michael Klausner. Do IPO charters maximize firm value? Antitakeover protection in IPOs. 17 J.L. Econ. & Org. 83-120 (2001).7.Hansmann, Henry and Reinier Kraakman. The essential role of organizational law. 110 Y ale L.J. 387-440 (2000).ngevoort, Donald C. The human nature of corporate boards: law, norms, and the unintended consequences of independence and accountability. 89 Geo. L.J. 797-832 (2001).9.Mahoney, Paul G. The political economy of the Securities Act of 1933. 30 J. Legal Stud. 1-31 (2001).10.Roe, Mark J. Political preconditions to separating ownership from corporate control. 53 Stan. L. Rev. 539-606 (2000).11.Romano, Roberta. Less is more: making institutional investor activism a valuable mechanism of corporate governance. 18 Y ale J. on Reg. 174-251 (2001).2000年:1.Bratton, William W. and Joseph A. McCahery. Comparative Corporate Governance and the Theory of the Firm: The Case Against Global Cross Reference. 38 Colum. J. Transnat’l L. 213-297 (1999).2.Coates, John C. IV. Empirical Evidence on Structural Takeover Defenses: Where Do We Stand?54 U. Miami L. Rev. 783-797 (2000).3.Coffee, John C., Jr. Privatization and Corporate Governance: The Lessons from Securities Market Failure. 25 J. Corp. L. 1-39 (1999).4.Fisch, Jill E. The Peculiar Role of the Delaware Courts in the Competition for Corporate Charters. 68 U. Cin. L. Rev. 1061-1100 (2000).5.Fox, Merritt B. Retained Mandatory Securities Disclosure: Why Issuer Choice Is Not Investor Empowerment. 85 V a. L. Rev. 1335-1419 (1999).6.Fried, Jesse M. Insider Signaling and Insider Trading with Repurchase Tender Offers. 67 U. Chi. L. Rev. 421-477 (2000).7.Gulati, G. Mitu, William A. Klein and Eric M. Zolt. Connected Contracts. 47 UCLA L. Rev. 887-948 (2000).8.Hu, Henry T.C. Faith and Magic: Investor Beliefs and Government Neutrality. 78 Tex. L. Rev. 777-884 (2000).9.Moll, Douglas K. Shareholder Oppression in Close Corporations: The Unanswered Question of Perspective. 53 V and. L. Rev. 749-827 (2000).10.Schizer, David M. Executives and Hedging: The Fragile Legal Foundation of Incentive Compatibility. 100 Colum. L. Rev. 440-504 (2000).11.Smith, Thomas A. The Efficient Norm for Corporate Law: A Neotraditional Interpretation of Fiduciary Duty. 98 Mich. L. Rev. 214-268 (1999).12.Thomas, Randall S. and Kenneth J. Martin. The Determinants of Shareholder V oting on Stock Option Plans. 35 Wake Forest L. Rev. 31-81 (2000).13.Thompson, Robert B. Preemption and Federalism in Corporate Governance: Protecting Shareholder Rights to V ote, Sell, and Sue. 62 Law & Contemp. Probs. 215-242 (1999).1999年(以第一作者姓名音序为序):1.Bankman, Joseph and Ronald J. Gilson. Why Start-ups? 51 Stan. L. Rev. 289-308 (1999).2.Bhagat, Sanjai and Bernard Black. The Uncertain Relationship Between Board Composition and Firm Performance. 54 Bus. Law. 921-963 (1999).3.Blair, Margaret M. and Lynn A. Stout. A Team Production Theory of Corporate Law. 85 V a. L. Rev. 247-328 (1999).4.Coates, John C., IV. “Fair V alue” As an A voidable Rule of Corporate Law: Minority Discounts in Conflict Transactions. 147 U. Pa. L. Rev. 1251-1359 (1999).5.Coffee, John C., Jr. The Future as History: The Prospects for Global Convergence in Corporate Governance and Its Implications. 93 Nw. U. L. Rev. 641-707 (1999).6.Eisenberg, Melvin A. Corporate Law and Social Norms. 99 Colum. L. Rev. 1253-1292 (1999).7.Hamermesh, Lawrence A. Corporate Democracy and Stockholder-Adopted By-laws: Taking Back the Street? 73 Tul. L. Rev. 409-495 (1998).8.Krawiec, Kimberly D. Derivatives, Corporate Hedging, and Shareholder Wealth: Modigliani-Miller Forty Y ears Later. 1998 U. Ill. L. Rev. 1039-1104.ngevoort, Donald C. Rereading Cady, Roberts: The Ideology and Practice of Insider Trading Regulation. 99 Colum. L. Rev. 1319-1343 (1999).ngevoort, Donald C. Half-Truths: Protecting Mistaken Inferences By Investors and Others.52 Stan. L. Rev. 87-125 (1999).11.Talley, Eric. Turning Servile Opportunities to Gold: A Strategic Analysis of the Corporate Opportunities Doctrine. 108 Y ale L.J. 277-375 (1998).12.Williams, Cynthia A. The Securities and Exchange Commission and Corporate Social Transparency. 112 Harv. L. Rev. 1197-1311 (1999).1998年:1.Carney, William J., The Production of Corporate Law, 71 S. Cal. L. Rev. 715-780 (1998).2.Choi, Stephen, Market Lessons for Gatekeepers, 92 Nw. U. L. Rev. 916-966 (1998).3.Coffee, John C., Jr., Brave New World?: The Impact(s) of the Internet on Modern Securities Regulation. 52 Bus. Law. 1195-1233 (1997).ngevoort, Donald C., Organized Illusions: A Behavioral Theory of Why Corporations Mislead Stock Market Investors (and Cause Other Social Harms). 146 U. Pa. L. Rev. 101-172 (1997).ngevoort, Donald C., The Epistemology of Corporate-Securities Lawyering: Beliefs, Biases and Organizational Behavior. 63 Brook. L. Rev. 629-676 (1997).6.Mann, Ronald J. The Role of Secured Credit in Small-Business Lending. 86 Geo. L.J. 1-44 (1997).haupt, Curtis J., Property Rights in Firms. 84 V a. L. Rev. 1145-1194 (1998).8.Rock, Edward B., Saints and Sinners: How Does Delaware Corporate Law Work? 44 UCLA L. Rev. 1009-1107 (1997).9.Romano, Roberta, Empowering Investors: A Market Approach to Securities Regulation. 107 Y ale L.J. 2359-2430 (1998).10.Schwab, Stewart J. and Randall S. Thomas, Realigning Corporate Governance: Shareholder Activism by Labor Unions. 96 Mich. L. Rev. 1018-1094 (1998).11.Skeel, David A., Jr., An Evolutionary Theory of Corporate Law and Corporate Bankruptcy. 51 V and. L. Rev. 1325-1398 (1998).12.Thomas, Randall S. and Martin, Kenneth J., Should Labor Be Allowed to Make Shareholder Proposals? 73 Wash. L. Rev. 41-80 (1998).1997年:1.Alexander, Janet Cooper, Rethinking Damages in Securities Class Actions, 48 Stan. L. Rev. 1487-1537 (1996).2.Arlen, Jennifer and Kraakman, Reinier, Controlling Corporate Misconduct: An Analysis of Corporate Liability Regimes, 72 N.Y.U. L. Rev. 687-779 (1997).3.Brudney, Victor, Contract and Fiduciary Duty in Corporate Law, 38 B.C. L. Rev. 595-665 (1997).4.Carney, William J., The Political Economy of Competition for Corporate Charters, 26 J. Legal Stud. 303-329 (1997).5.Choi, Stephen J., Company Registration: Toward a Status-Based Antifraud Regime, 64 U. Chi. L. Rev. 567-651 (1997).6.Fox, Merritt B., Securities Disclosure in a Globalizing Market: Who Should Regulate Whom. 95 Mich. L. Rev. 2498-2632 (1997).7.Kahan, Marcel and Klausner, Michael, Lockups and the Market for Corporate Control, 48 Stan. L. Rev. 1539-1571 (1996).8.Mahoney, Paul G., The Exchange as Regulator, 83 V a. L. Rev. 1453-1500 (1997).haupt, Curtis J., The Market for Innovation in the United States and Japan: V enture Capital and the Comparative Corporate Governance Debate, 91 Nw. U.L. Rev. 865-898 (1997).10.Skeel, David A., Jr., The Unanimity Norm in Delaware Corporate Law, 83 V a. L. Rev. 127-175 (1997).1996年:1.Black, Bernard and Reinier Kraakman A Self-Enforcing Model of Corporate Law, 109 Harv. L. Rev. 1911 (1996)2.Gilson, Ronald J. Corporate Governance and Economic Efficiency: When Do Institutions Matter?, 74 Wash. U. L.Q. 327 (1996)3. Hu, Henry T.C. Hedging Expectations: "Derivative Reality" and the Law and Finance of the Corporate Objective, 21 J. Corp. L. 3 (1995)4.Kahan, Marcel & Michael Klausner Path Dependence in Corporate Contracting: Increasing Returns, Herd Behavior and Cognitive Biases, 74 Wash. U. L.Q. 347 (1996)5.Kitch, Edmund W. The Theory and Practice of Securities Disclosure, 61 Brooklyn L. Rev. 763 (1995)ngevoort, Donald C. Selling Hope, Selling Risk: Some Lessons for Law From Behavioral Economics About Stockbrokers and Sophisticated Customers, 84 Cal. L. Rev. 627 (1996)7.Lin, Laura The Effectiveness of Outside Directors as a Corporate Governance Mechanism: Theories and Evidence, 90 Nw. U.L. Rev. 898 (1996)lstein, Ira M. The Professional Board, 50 Bus. Law 1427 (1995)9.Thompson, Robert B. Exit, Liquidity, and Majority Rule: Appraisal's Role in Corporate Law, 84 Geo. L.J. 1 (1995)10.Triantis, George G. and Daniels, Ronald J. The Role of Debt in Interactive Corporate Governance. 83 Cal. L. Rev. 1073 (1995)1995年:公司法:1.Arlen, Jennifer and Deborah M. Weiss A Political Theory of Corporate Taxation,. 105 Y ale L.J. 325-391 (1995).2.Elson, Charles M. The Duty of Care, Compensation, and Stock Ownership, 63 U. Cin. L. Rev. 649 (1995).3.Hu, Henry T.C. Heeding Expectations: "Derivative Reality" and the Law and Finance of the Corporate Objective, 73 Tex. L. Rev. 985-1040 (1995).4.Kahan, Marcel The Qualified Case Against Mandatory Terms in Bonds, 89 Nw. U.L. Rev. 565-622 (1995).5.Klausner, Michael Corporations, Corporate Law, and Networks of Contracts, 81 V a. L. Rev. 757-852 (1995).6.Mitchell, Lawrence E. Cooperation and Constraint in the Modern Corporation: An Inquiry Into the Causes of Corporate Immorality, 73 Tex. L. Rev. 477-537 (1995).7.Siegel, Mary Back to the Future: Appraisal Rights in the Twenty-First Century, 32 Harv. J. on Legis. 79-143 (1995).证券法:1.Grundfest, Joseph A. Why Disimply? 108 Harv. L. Rev. 727-747 (1995).2.Lev, Baruch and Meiring de V illiers Stock Price Crashes and 10b-5 Damages: A Legal Economic, and Policy Analysis, 47 Stan. L. Rev. 7-37 (1994).3.Mahoney, Paul G. Mandatory Disclosure as a Solution to Agency Problems, 62 U. Chi. L. Rev. 1047-1112 (1995).4.Seligman, Joel The Merits Do Matter, 108 Harv. L. Rev. 438 (1994).5.Seligman, Joel The Obsolescence of Wall Street: A Contextual Approach to the Evolving Structure of Federal Securities Regulation, 93 Mich. L. Rev. 649-702 (1995).6.Stout, Lynn A. Are Stock Markets Costly Casinos? Disagreement, Mark Failure, and Securities Regulation, 81 V a. L. Rev. 611 (1995).7.Weiss, Elliott J. and John S. Beckerman Let the Money Do the Monitoring: How Institutional Investors Can Reduce Agency Costs in Securities Class Actions, 104 Y ale L.J. 2053-2127 (1995).1994年:公司法:1.Fraidin, Stephen and Hanson, Jon D. Toward Unlocking Lockups, 103 Y ale L.J. 1739-1834 (1994)2.Gordon, Jeffrey N. Institutions as Relational Investors: A New Look at Cumulative V oting, 94 Colum. L. Rev. 124-192 (1994)3.Karpoff, Jonathan M., and Lott, John R., Jr. The Reputational Penalty Firms Bear From Committing Criminal Fraud, 36 J.L. & Econ. 757-802 (1993)4.Kraakman, Reiner, Park, Hyun, and Shavell, Steven When Are Shareholder Suits in Shareholder Interests?, 82 Geo. L.J. 1733-1775 (1994)5.Mitchell, Lawrence E. Fairness and Trust in Corporate Law, 43 Duke L.J. 425- 491 (1993)6.Oesterle, Dale A. and Palmiter, Alan R. Judicial Schizophrenia in Shareholder V oting Cases, 79 Iowa L. Rev. 485-583 (1994)7. Pound, John The Rise of the Political Model of Corporate Governance and Corporate Control, 68 N.Y.U. L. Rev. 1003-1071 (1993)8.Skeel, David A., Jr. Rethinking the Line Between Corporate Law and Corporate Bankruptcy, 72 Tex. L. Rev. 471-557 (1994)9.Thompson, Robert B. Unpacking Limited Liability: Direct and V icarious Liability of Corporate Participants for Torts of the Enterprise, 47 V and. L. Rev. 1-41 (1994)证券法:1.Alexander, Janet Cooper The V alue of Bad News in Securities Class Actions, 41 UCLA L.Rev. 1421-1469 (1994)2.Bainbridge, Stephen M. Insider Trading Under the Restatement of the Law Governing Lawyers, 19 J. Corp. L. 1-40 (1993)3.Black, Bernard S. and Coffee, John C. Jr. Hail Britannia?: Institutional Investor Behavior Under Limited Regulation, 92 Mich. L. Rev. 1997-2087 (1994)4.Booth, Richard A. The Efficient Market, portfolio Theory, and the Downward Sloping Demand Hypothesis, 68 N.Y.U. L. Rev. 1187-1212 (1993)5.Coffee, John C., Jr. The SEC and the Institutional Investor: A Half-Time Report, 15 Cardozo L. Rev 837-907 (1994)6.Fox, Merritt B. Insider Trading Deterrence V ersus Managerial Incentives: A Unified Theory of Section 16(b), 92 Mich. L. Rev. 2088-2203 (1994)7.Grundfest, Joseph A. Disimplying Private Rights of Action Under the Federal Securities Laws: The Commission's Authority, 107 Harv. L. Rev. 961-1024 (1994)8.Macey, Jonathan R. Administrative Agency Obsolescence and Interest Group Formation: A Case Study of the SEC at Sixty, 15 Cardozo L. Rev. 909-949 (1994)9.Rock, Edward B. Controlling the Dark Side of Relational Investing, 15 Cardozo L. Rev. 987-1031 (1994)。

600万美元抄底美商业地产将建立成为“中国名牌之家”

1 32 3 .2亿 美元 , 占跨国并购 交 易总额 的 8 % 。 82

专 家认 为 , 年海 外并 购 中 ,联 合并 购 方式兴 起、 民 营 今

企业 并购增 加 、品 牌和知 识 产权并 购升 温 等新 动 向很值 得 关 注 ,它们显 示 出中 国企业 海外 并购渐 入佳 境。

3 2起 , 占 跨 国 并 购 交 易 量 的 5 % ;披 露 的 并 购 金 额 达 到 25

城是 密 尔沃基 附 近最 大的 S o pn l之一 。北 京 民营企 业 h p ig Mal

O

斥资 “ 吃下 ” 整栋 商 城及 周 边停 车 场仅 用 了 6 O万 美 元 ,折 O

盟 “ 结 令 ” 集 。

中 国经 济 发达 省份 广 东 也力 推 粤 企 赴 东 盟投 资 。 广东 省 对 外贸 易经 济合 作 厅 厅 长 梁耀 文 说 ,广 东 将采 取 更 多措 施 推 动 企业 赴 东 盟 投 资。 这 些措 施 包 括 制订 、 落 实、 培 育 广东 跨

国 公 司 、 跨 国 人 才 的 相 关 政 策 措 施 ,培 育 和 建 立 一 批 广 东 “ 走

GDP 约 45万 亿 美 元 贸 易 总 额 的 大 市 场 。 对 企 业 来 说 , 这 是 、 .

一

也 许是 看到 了这 种优 惠和便 利 , 以及 东盟 内部 的市场 潜力 , 2 9年 1 ∞ 2月底 ,四川 省商务 斤 举办 了中 国— — 东盟 自由贸 易 区 建 设与 机 遇报 告 会 , 对在 场 的 五百 多家 企业 发 起 了 对接 东

Tr d & I v s me t商情投资 a e et n n

O

9

2C O 臼年 收官 之际 ,国内企 业又掀 起 了一波 海 外并购 的高 潮。从 备 受关 注 的吉利 与福特 就 收购沃 尔 沃达 成一 致 ,到 广 东顺 德 日新 收购智 利特 大铁矿 ,再 到 中 国铁建 与铜 陵有 色联 合 收购 厄瓜 多 尔铜矿 , 并购 数据 一再 被刷 新。 纵观 整个 2 O O9

办公工具bain战略分析工具profitpool

10.01.2024

Darral G Clarke for BM 499

7

Turbulent industries

Profit pools are especially important and useful in industries undergoing deregulation and/or technological change

Essentially an accounting process no theory Most valuable in situations in which external conditions

are essential stable and/or unimportant Often dominated by internal data alone

The goal should be to focus on profitable opportunities

Industry should be considered more broadly than traditional definition

Automobile industry includes

10.01.2024

Darral G Clarke for BM 499

10

Marakon Runners

10.01.2024

Thomas A Stewart Fortune

Sept 28; 1998

Darral G Clarke for BM 499

11

Marakon Associates’s Approach to Corporate Strategy

10

5

0

0

雀巢英文介绍

Annual turnover : 92.2 billion Swiss francs

Employees : 339000

Slogan : Good Food,Good Life.

The mission of "Good Food, Good Life" is to provide consumers with the best tasting, most nutritious choices in a wide range of

Nestlé Nutrition Heiko Schipper

Corporate Communications Rudolf Ramsauer

Nestlé family coat of arms

1868

1938

1995

1988

1966

Henri Nestlé adapted the

coat of arms by adding three young birds being fed by a

In 1908, Nestlé opened a sales office in Shanghai. In 1920, the creation of Nestle Products Limited in Hong Kong. In 1990, Nestlé opened its first factory in China, Heilongjiang Shuangcheng, milk production. 1993-2006, gradually building 16 plants to meet growing consumer demand.

mother, to create a visual link

纽约新泽西港:美国东部的门户——专访纽约新泽西港商务部部长Rick Larrabee

与 会 记 者 的 追 问 , 因 为纽 约 新 泽西 营 。 其 中 包 括 肯 尼 迪 国 际 机 场 、 瓦 机 构 。 是 纽

港 作 为 美 国 东部 的 重要 门户 , 货量 克 自 由 国际 机 场 、 拉 瓜 迪 亚 机 场 、 其 特 “ 们 的 运 营 模 式 是 地 主 港 模 我

u l r ae 兰 克 码 头 、 呼 克 码 头 等 6个 海 运 我 们 港 口创 新 实 行 的 P bi p i t 瑞 个重 要 的港 口。

服 务 于 美 国 经 济 最 发 达 地 区

J K 场 轻 轨 干 线和 纽 瓦克 轻 轨 干 线 被 广 泛 地 推 广 。 ” c arb e表 F机 Ri L r e k a

纽约新泽西港 : 美国东部 的门户

专访 纽 约新 泽西港 商务部 部 长 Ri a ae c Lr be k r

文 / 刊记 者 本 刘 光 琦

一

场 由美国 始发 的 金融 海 啸正 在 约 新 泽 西 港 务 局 的 管 理 运 营 模 式 称 泽 西 港务 局 还 是 W T C的 业 主 ,现拥 为是 目前 在 世 界上 独 一 无二 的 。 有2 5公 顷世 贸 中心 的土 地 ,负 责世

Rc arb e先生 自豪地把 纽 和 汽 车 总站 。 “ 1 ” 件 以前 纽 约新 示 , 约新 泽 西港 务局 与政府 、 发研 i Lr e k a 9 事 1 纽 开

' Ci o g r s  ̄mg i 2 9 / 0 ha ta n sre&tn o aan ap ze 0 01

个通 天 地 ,连 四海 的 大交 通管 理模

港 受 到 的影 响 , 请 其 预 言 这 场 金 融 是两 州 共 有 的 B— tt e c 。 纽 式 。 纽约 新泽 西 港务 局 的营 运 资金 并 并 isae Ag n y 风暴 将 肆虐 到何 时 。这 是 发生 在 第三 约 新 泽 西 港 务 局 负 责 以 自 由女 神 像 非源于 税 收 ,而 是来 自其 基 础设 施 每 届全 球 海运 峰 会上 的 一幕 。

全球生产网络视角下温州鞋业升级的路径探讨【文献综述】

文献综述国际经济与贸易全球生产网络视角下温州鞋业升级的路径探讨一、引言随着经济全球化的推进,以产品为基本单位的传统的国际分工形态已不再是主流,当代的国际分工的主要特征就是某个产品生产过程中所包含的不同工序被拆解并分配到不同的国家或者经济体中进行,利用不同国家或者经济体在不同工序间的比较优势发展规模经济。

这种分工不仅使得发展中国家的企业能够广泛地参与技术含量较高的国际分工体系,而且还促进世界经济的整体结构变迁和国际运输成本的下降,加快了多边和区域贸易自由化的进程。

在全球化的背景下,温州鞋业已经不可避免地卷入到全球生产网络之中。

虽然温州鞋业发展起步较早,但在国际市场上始终缺乏知名度,往往进行的是低附加值部分的生产活动。

按照中国皮革协会理事长张淑华的话说,制鞋业是“候鸟经济”,总是向劳动力成本低的国家和地区转移。

然而,近些年随着温州当地的劳动力成本的上升,以及各种贸易技术壁垒的纷至沓来,温州鞋业不得不面临升级的压力。

目前,国内外学者对全球生产网络及产业升级已经做了相当多的研究,以下就这些学者的研究成果进行文献综述。

二、国外关于全球生产网络内产业升级的研究(一)全球生产网络的概念全球生产网络最早是由Ernst(1999)提出来的,同年,Dieken& Henderson (1999)在一篇研究报告中也提出了同样的概念。

根据Ernst(2002)的解释,全球生产网络是一种将跨国公司和国家边界的地理集中与空间分散的价值链和网络参与者的内部科层一体化过程连接起来的组织结构。

Gereffi(1999)认为全球生产网络就像是由一个个相互独立又相互联系的企业构成的蜘蛛网,核心企业作为战略经纪人占据蜘蛛网的中心,掌控着整个全球网络有效运动所必需的关键信息、技术和资源。

任何国家或企业要在当今的国际经济环境中取得成功,就必须在全球网络里正确定位自己的战略位置,并制定各种接近领袖企业的战略以便提升自己的地位。

跨国公司和采购商纷纷将自己的核心竞争力以外的其他环节外包给世界的其他国家和地区,使得价值链中的各环节超越了国家的界限,而一项产品依次要经历设计、原料采购、加工、销售等环节,每个环节对知识和技术的要求又是不同的,再者考虑到国内外的各种体制背景如政策法规等都会对价值链上的各个节点产生影响,根据Gereffi(2003)的观点,全球价值链(全球生产网络)作为一种产业组织形式,对其的研究可以从四个不同的维度出发:投入——产出结构,空间布局,治理结构,体制框架。

欧美国家社区治理的结构、功能及合法性基础

欧美国家社区治理的结构、功能及合法性基础吴素雄;吴艳【摘要】欧美国家社区治理的概念框架关联着社区治理主体、主体间关系及治理目标的重新确认,其初始动因与政府服务向社区传递中的部门分割有关,这牵涉到社区协同治理的结构,进而要求重新定位社区领导权、政府赋权状态与社区社会资本,并形成政府与社区的合作伙伴关系,这一模式包括从横向视角合理划分法人治理、公共部门治理与私人部门治理的结构,并通过聚焦、定向与技术来纵向解决社区项目制治理实践的代理困境,但社区治理网络强化了领导权,这需要从理论上解释其合法性,即要将社区治理与公民参与、政府的政策选择与实施以及社区绩效评估相关联,这一社区主义趋向也体现了对“元治理”的背反.【期刊名称】《山东大学学报(哲学社会科学版)》【年(卷),期】2017(000)002【总页数】9页(P48-56)【关键词】欧美社区治理;合作伙伴关系;治理结构【作者】吴素雄;吴艳【作者单位】温州医科大学公共卫生与管理学院温州325035;温州医科大学温州325035【正文语种】中文自滕尼斯1887年提出“社区”概念至20世纪中期,社区建构与社区运动经历了反复。

到了20世纪七八十年代,新自由主义的影响使得社区政策照顾对象从“普遍性原则”转向“选择性原则”,期间,社区主义(又称社群主义)主张构建权利与义务、个体与社群之间的平衡”①Adams G. B., Catron, B. L., Communitarianism, Vickers, and Revisioning American Public Administration, American Behavioral Science. 1994. Vol. 38(1). pp.6789.。

多元主义则强调塑造“基于社区”的治理网络,引入社会组织的参与,推崇“结构—反应”机制以增强回应性②Bellef euille G., The New Politics of Community-based Governance Requires a Fundamental Shift in the Nature and Character of the Administrative Bureaucracy. Children and Youth Services Review. 2005.27(5). pp.889.。

中国企业家杂志英文简介

中国企业家杂志英文简介China Entrepreneur Magazine (CEM) is a leading business publication in China that aims to provide insightful and comprehensive coverage of the country's entrepreneurial landscape. With a rich history spanning over two decades, CEM has become an authoritative source of business news, analysis, and advice for entrepreneurs, executives, and investors alike.Founded in 1991, CEM has played a crucial role in documenting and promoting the rise of entrepreneurship in China. The magazine offers a unique perspective on the challenges and opportunities faced by Chinese entrepreneurs, as well as the broader trends shaping the country's business environment. CEM's in-depth articles, interviews, and case studies provide valuable insights into the strategies and experiences of successful entrepreneurs, offering readers practical advice and inspiration for their own entrepreneurial journeys.One of CEM's key strengths is its extensive network of contributors and industry experts. The magazine regularly features articles written by top business leaders, economists, and scholars, offering diverse perspectives and analysis on a wide range of topics. Whether it's the latest developments in technology, finance, or management, CEM ensures that its readers are kept informed and up-to-date with the ever-changing business landscape in China.CEM's editorial team is dedicated to delivering high-quality and objective journalism. The magazine's content is thoroughly researched and fact-checked, ensuring that readers can rely on the accuracy and credibility of the information presented. CEM's commitment to journalistic integrity has earned it a reputation as a trusted source of business news and analysis, both within China and internationally.In addition to its print publication, CEM has embraced the digital age, providing an online platform and mobile app for readers to access its content anytime, anywhere. The magazine's website features exclusive articles, interviews, and videos, expanding its reach and offering a more interactive and immersive reading experience. CEM's digitalpresence has allowed it to reach a broader audience and engage with readers on a more personal level.Beyond its role as a publication, CEM also organizes various events and conferences to foster networking and knowledge-sharing within the business community. These events provide a platform for entrepreneurs, executives, and investors to connect, exchange ideas, and learn from industry experts. CEM's commitment to supporting and promoting entrepreneurship in China extends beyond its pages, making it a valuable resource and catalyst for business innovation and growth.In conclusion, China Entrepreneur Magazine is a premier business publication that offers a comprehensive and insightful view of the Chinese entrepreneurial landscape. With its rich history, extensive network of contributors, and commitment to journalistic integrity, CEM has established itself as a trusted source of business news, analysis, and advice. Whether in print or online, CEM continues to play a vital role in documenting and promoting entrepreneurship in China, serving as a valuable resource for entrepreneurs, executives, and investors alike.。

美国消费者法案2024年度认证指南

美国消费者法案2024年度认证指南下载温馨提示:该文档是我店铺精心编制而成,希望大家下载以后,能够帮助大家解决实际的问题。

文档下载后可定制随意修改,请根据实际需要进行相应的调整和使用,谢谢!并且,本店铺为大家提供各种各样类型的实用资料,如教育随笔、日记赏析、句子摘抄、古诗大全、经典美文、话题作文、工作总结、词语解析、文案摘录、其他资料等等,如想了解不同资料格式和写法,敬请关注!Download tips: This document is carefully compiled by the editor. I hope that after you download them, they can help you solve practical problems. The document can be customized and modified after downloading, please adjust and use it according to actual needs, thank you!In addition, our shop provides you with various types of practical materials, suchas educational essays, diary appreciation, sentence excerpts, ancient poems, classic articles, topic composition, work summary, word parsing, copy excerpts, other materials and so on, want to know different data formats and writing methods, please pay attention!美国消费者法案2024年度认证指南是未来一年内美国消费者需遵循的法规和标准。

公司使命陈述

公司使命陈述《公司使命陈述》----301家美国顶级公司使命陈述(美)杰弗瑞.业伯拉罕斯上海人民出版社目录:Federated Department Stores,Inc.联合百货公司(1) Gibson Greetings,Inc.吉布森礼品公司(2)Kmart凯马特公司(3)Lowe’s companies,Inc劳威氏联合公司(3)Maritz Inc马里兹公司(4)Meyer(Fred Meyer,Inc.)梅耶公司(5)Office Depot奥菲斯.迪波特公司(6)Penney(J.C.Penney Company,Inc)彭尼公司(7)Staples斯坦普斯公司(8)Tandy Corporation(Radioshack)坦迪公司(10)The United States Shoe Corporation美国鞋业公司(11) The V ons Companides,Inc旺斯连锁公司(11)Federated Department Stores,Inc.联合百货公司公司哲学:联合公司清醒地认识到顾客具有至高无上的地位,我们所采取的所有行动和战略遵循一个指导方针:通过遍及全国的零售商店,为目标顾客提供更好的商品和服务。

通过缜密而彻底的战略设计,再辅之以积极的实施,联合百货将会极具竞争力。

联合百货承诺与员工、股东、批发商、分析家以及新闻媒体进行公开而坦诚的交流沟通,并随时与之共享我们最新的信息和重要的具有实质性的目标。

公司目标:提高销售增长速度;不断提高以息税前收益率和总投资率为衡量标准的利润水平,公司始终致力于改善经营结构以降低成本;发掘与公司商业目标相一致的战略增长机会;维持公司资产负债表的平衡。

公司简介:联合百货公司是美国最大连锁百货商店,在全美各个主要地区均设有分店。

行业类型:零售业Gibson Greetings,Inc.吉布森礼品公司我们的使命:我们的使命是提供能够表达个人感情的最高质量的产品;通过创新、及时反应和生产来支持零售商的经营目标;并且达到股东和合作伙伴的目标。

美国科恩集团北京代表处介绍企业发展分析报告

Enterprise Development专业品质权威Analysis Report企业发展分析报告美国科恩集团北京代表处免责声明:本报告通过对该企业公开数据进行分析生成,并不完全代表我方对该企业的意见,如有错误请及时联系;本报告出于对企业发展研究目的产生,仅供参考,在任何情况下,使用本报告所引起的一切后果,我方不承担任何责任:本报告不得用于一切商业用途,如需引用或合作,请与我方联系:美国科恩集团北京代表处1企业发展分析结果1.1 企业发展指数得分企业发展指数得分美国科恩集团北京代表处综合得分说明:企业发展指数根据企业规模、企业创新、企业风险、企业活力四个维度对企业发展情况进行评价。

该企业的综合评价得分需要您得到该公司授权后,我们将协助您分析给出。

1.2 企业画像类别内容行业化学原料和化学制品制造业-基础化学原料制造资质空产品服务国(地区)企业有关的非营利性业务活动。

1.3 发展历程2工商2.1工商信息2.2工商变更2.3股东结构2.4主要人员2.5分支机构2.6对外投资2.7企业年报2.8股权出质2.9动产抵押2.10司法协助2.11清算2.12注销3投融资3.1融资历史3.2投资事件3.3核心团队3.4企业业务4企业信用4.1企业信用4.2行政许可-工商局4.3行政处罚-信用中国4.4行政处罚-工商局4.5税务评级4.6税务处罚4.7经营异常4.8经营异常-工商局4.9采购不良行为4.10产品抽查4.11产品抽查-工商局4.12欠税公告4.13环保处罚4.14被执行人5司法文书5.1法律诉讼(当事人)5.2法律诉讼(相关人)5.3开庭公告5.4被执行人5.5法院公告5.6破产暂无破产数据6企业资质6.1资质许可6.2人员资质6.3产品许可6.4特殊许可7知识产权7.1商标7.2专利7.3软件著作权7.4作品著作权7.5网站备案7.6应用APP7.7微信公众号8招标中标8.1政府招标8.2政府中标8.3央企招标8.4央企中标9标准9.1国家标准9.2行业标准9.3团体标准9.4地方标准10成果奖励10.1国家奖励10.2省部奖励10.3社会奖励10.4科技成果11土地11.1大块土地出让11.2出让公告11.3土地抵押11.4地块公示11.5大企业购地11.6土地出租11.7土地结果11.8土地转让12基金12.1国家自然基金12.2国家自然基金成果12.3国家社科基金13招聘13.1招聘信息感谢阅读:感谢您耐心地阅读这份企业调查分析报告。

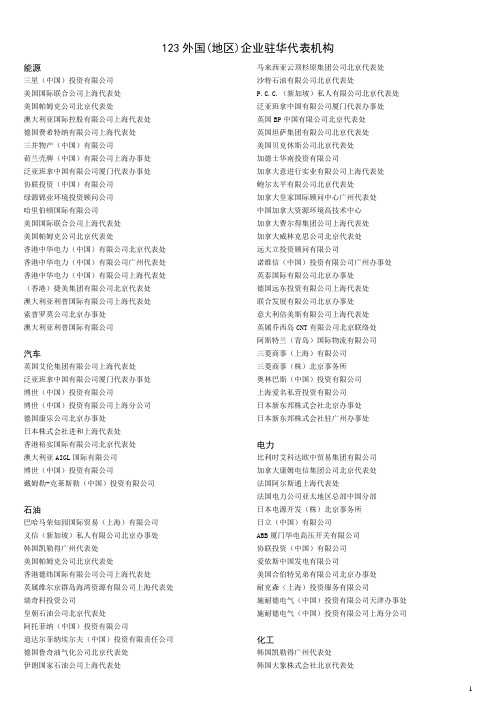

外国(地区)企业驻华代表机构123

123外国(地区)企业驻华代表机构能源三星(中国)投资有限公司美国国际联合公司上海代表处美国帕姆克公司北京代表处澳大利亚国际控股有限公司上海代表处德国费希特纳有限公司上海代表处三井物产(中国)有限公司荷兰壳牌(中国)有限公司上海办事处泛亚班拿中国有限公司厦门代表办事处协联投资(中国)有限公司绿源锦业环境投资顾问公司哈里伯顿国际有限公司美国国际联合公司上海代表处美国帕姆克公司北京代表处香港中华电力(中国)有限公司北京代表处香港中华电力(中国)有限公司广州代表处香港中华电力(中国)有限公司上海代表处(香港)捷美集团有限公司北京代表处澳大利亚利普国际有限公司上海代表处索普罗莫公司北京办事处澳大利亚利普国际有限公司汽车英国艾伦集团有限公司上海代表处泛亚班拿中国有限公司厦门代表办事处博世(中国)投资有限公司博世(中国)投资有限公司上海分公司德国康乐公司北京办事处日本株式会社进和上海代表处香港裕实国际有限公司北京代表处澳大利亚AIGL国际有限公司博世(中国)投资有限公司戴姆勒-克莱斯勒(中国)投资有限公司石油巴哈马荣知园国际贸易(上海)有限公司义信(新加坡)私人有限公司北京办事处韩国凯勒得广州代表处美国帕姆克公司北京代表处香港德炜国际有限公司公司上海代表处英属维尔京群岛海湾资源有限公司上海代表处瑞奇科投资公司皇朝石油公司北京代表处阿托菲纳(中国)投资有限公司道达尔菲纳埃尔夫(中国)投资有限责任公司德国鲁奇油气化公司北京代表处伊朗国家石油公司上海代表处马来西亚云顶杉原集团公司北京代表处沙特石油有限公司北京代表处P.C.C.(新加坡)私人有限公司北京代表处泛亚班拿中国有限公司厦门代表办事处英国BP中国有限公司北京代表处英国坦萨集团有限公司北京代表处美国贝克休斯公司北京代表处加德士华南投资有限公司加拿大意进行实业有限公司上海代表处鲍尔太平有限公司北京代表处加拿大皇家国际顾问中心广州代表处中国加拿大资源环境高技术中心加拿大费尔得集团公司上海代表处加拿大威林克思公司北京代表处远大立投资顾问有限公司诺维信(中国)投资有限公司广州办事处英泰国际有限公司北京办事处德国远东投资有限公司上海代表处联合发展有限公司北京办事处意大利倍美斯有限公司上海代表处英属乔西岛CNT有限公司北京联络处阿斯特兰(青岛)国际物流有限公司三菱商事(上海)有限公司三菱商事(株)北京事务所奥林巴斯(中国)投资有限公司上海爱名私营投资有限公司日本新东邦株式会社北京办事处日本新东邦株式会社驻广州办事处电力比利时艾科达欧中贸易集团有限公司加拿大康姆电信集团公司北京代表处法国阿尔斯通上海代表处法国电力公司亚太地区总部中国分部日本电源开发(株)北京事务所日立(中国)有限公司ABB厦门华电高压开关有限公司协联投资(中国)有限公司爱依斯中国发电有限公司美国合伯特兄弟有限公司北京办事处耐克森(上海)投资服务有限公司施耐德电气(中国)投资有限公司天津办事处施耐德电气(中国)投资有限公司上海分公司化工韩国凯勒得广州代表处韩国大象株式会社北京代表处大象株式会社上海代表处美国国际化工有限公司上海代表处香港德炜国际有限公司公司上海代表处香港意勤实业有限公司北京办事处积水(香港)有限公司上海代表处香港新鸿基(中国)有限公司上海代表处香港和宇发展有限公司北京代表处比利时艾科达欧中贸易集团有限公司英属维尔京群岛海湾资源有限公司上海代表处法国液化空气公司北京代表处阿托菲纳(中国)投资有限公司法国环球贸易公司北京代表处德固萨太平洋有限公司北京代表处德固萨太平洋有限公司上海代表处德国鲁奇油气化公司北京代表处三井物产(中国)有限公司荷兰壳牌(中国)有限公司上海办事处沙特石油有限公司北京代表处814家外企驻中国代表处机构澳翔(天津)国际贸易有限公司澳大利亚ACTM北京办事处澳大利亚澳中经济技术交流中心北京代表处澳大利亚昆士兰州政府贸易投资中国代表处澳大利亚西澳大利亚贸易投资促进上海代表处巴哈马荣知园国际贸易(上海)有限公司比利时法兰德斯州贸易促进会武汉代表处比利时法兰德斯州贸易促进会上海代表处英属维尔京群岛智帮投资公司上海办事处英属维尔京群岛全科有限公司上海代表处英属维尔京群软库中国创业投资有限公司上海代表处科创投资顾问有限公司上海办事处南澳大利亚投资公司上海代表处加拿大加达国际商务投资咨询公司淄博办事处加拿大特易达投资有限公司北京代表处加拿大(亚洲)投资有限公司加拿大联邦国际金融公司北京代表处加拿大第一海外投资公司北京办事处加拿大第一海外投资公司广州办事处加拿大第一海外投资公司天津办事处加拿大意进行实业有限公司上海代表处鲍尔太平有限公司北京代表处加拿大皇家国际顾问中心广州代表处中国加拿大资源环境高技术中心加拿大费尔得集团公司上海代表处加拿大威林克思公司北京代表处远大立投资顾问有限公司诺维信(中国)投资有限公司广州办事处英泰国际有限公司北京办事处德国远东投资有限公司上海代表处联合发展有限公司北京办事处意大利倍美斯有限公司上海代表处英属乔西岛CNT有限公司北京联络处阿斯特兰(青岛)国际物流有限公司三菱商事(上海)有限公司三菱商事(株)北京事务所奥林巴斯(中国)投资有限公司上海爱名私营投资有限公司日本新东邦株式会社北京办事处日本新东邦株式会社驻广州办事处日本东光商事株式会社北京办事处新西兰奥蒂琼斯(集团)有限公司上海代表处康联马洪(中国)投资管理有限公司百幕大虎牌包装投资有限公司义信(新加坡)私人有限公司北京办事处新加坡禄菲利咨询私人有限公司上海代表处新加坡房地产投资咨询(上海)有限公司优利投资咨询有限公司韩国凯勒得广州代表处韩国大象株式会社北京代表处大象株式会社上海代表处(株)大宇国际大连代表处韩国贸易协会北京代表处大韩贸易投资振兴公社上海代表处大韩贸易投资振兴公社北京代表处北京韩中商务中心有限责任公司三星(中国)投资有限公司三星(中国)投资有限公司亚洲国际有限公司西班牙加泰罗尼亚政府贸易促进协会西班牙依莎集团西班牙对外发展公司北京代表处沃尔沃中国投资有限公司沃尔沃(中国)投资有限公司上海代表处瑞士康欣公司北京代表处维欣风险投资有限公司香港义初投资有限公司上海代表处英国艾伦集团有限公司上海代表处英国贝特伯恩有限公司上海代表处英国贝特伯恩有限公司北京代表处英国贝特伯恩有限公司深圳代表处嘉实多(中国)有限公司上海办事处毛里求斯英联投资有限公司北京代表处英国佳士得国际有限公司上海代表处英国优瑞集团国际公司北京办事处景全责任有限公司上海代表处英国太古(中国)有限公司上海代表处英国利百得实业有限公司上海代表处英国米兰资源控股有限公司上海代表处英国O.F.S(远东)有限公司英国普林顿有限公司上海代表处英国斯坦科有限公司上海代表处上海天桥投资咨询有限公司英国威敏顿投资有限公司上海代表处美国艾克国际科技有限公司广州代表处美国兄弟公司美国查斯国际投资(集团)有限公司上海代表处美国机械制造技术协会上海联络处美国联亚集团有限公司北京代表处美商联众商业股份有限公司美商智迈企业有限公司广州办事处美国阿尔特公司上海代表处美国贝克曼库尔特公司上海办事处北京伊力诺依投资有限公司美国万宝环球资本集团北京代表处卡特彼勒中国投资有限公司美国中央采购(中国)有限公司上海代表处埃克森美孚投资有限公司武汉办事处埃克森美孚(中国)投资有限公司广州分公司美国费尔工业有限公司上海代表处美国高盛(中国)有限责任公司北京代表处美国汉斯合伙有限公司北京办事处美国荷雷国际公司北京代表处美国国际化工有限公司上海代表处美国英迈国际(中国)有限公司美国敏源国际有限公司上海代表处美国国际联合公司上海代表处美国健妮投资有限公司上海代表处美国吉安商业投资有限公司美国麦高国际集团公司上海代表处美国美特公司北京代表处美国美瑞国际公司北京办事处美国MG国际公司美国美利肯中国有限公司上海代表处美国MIR(中国)公司上海代表处美国纽约国际商业集团亚太代表处美国尼奥森国际股份有限公司北京办事处美国东方实业有限公司北京代表队处美国P.H.T.国际公司北京办事处美国帕姆克公司北京代表处百事(中国)投资有限公司美国普特股份有限公司上海代表处美国莱梦·格迪思公司上海代表处美国富国上海公司三联(美国)有限公司上海代表处美国美化国际有限公司上海代表处美国经济科学基金会上海代表处美国领事馆农业贸易处美国国际投资发展公司北京代表处怡昌行亚州有限公司上海办事处香港合孚行有限公司上海代表处香港信达远东国际有限公司广州代表处香港亚太经济集团股份有限公司香港美亚企业有限公司上海代表处香港奥星有限公司上海代表处美国亚飞太平洋有限公司香港辟高国际有限公司北京联络处京泰实业集团有限公司北京办事处香港环球宝鼎有限公司香港昌信集团有限公司北京办事处香港正大国际投资有限公司上海代表处香港招商局富鑫资产管理有限公司上海代表处香港华裔有限公司上海代表处英属开曼岛中国华登管理有限公司北京办事处香港中华国际集团有限公司上海代表处香港先达科技(中国)有限公司北京代表处广保国际集团有限公司朝代咨询(上海)有限公司香港瑞源国际公司北京代表处香港怡安国际集团有限公司北京代表处维昌洋行中国有限公司北京办事处恒基(中国)投资有限公司驻北京办事处香港中询有限公司上海代表处香港新华公司中山代表处香港德炜国际有限公司公司上海代表处香港贸易发展局成都办事处香港贸易发展局华南办事处香港贸易发展局上海代表处华法中国有限公司北京办事处香港和记黄埔(中国)有限公司上海代表处香港亚网集团有限公司北京代表处香港晋富(中国)投资有限公司怡富(中国)投资有限公司北京办事处怡和(中国)有限公司上海代表处怡和(中国)有限公司深圳办事处怡和(中国)有限公司北京办事处香港精裕投资有限公司鞍山办事处香港精裕投资有限公司北京办事处香港商宜美有限公司北京代表处香港意勤实业有限公司北京办事处香港倪汝德有限公司广州代表处明仕德公司广州代表处香港北亚咨询有限公司上海代表处香港中国物流集团有限公司上海代表处东方鑫源(集团有限公司北京办事处积水(香港)有限公司上海代表处香港上海实业(集团)有限公司上海代表处香港沪光国际投资管理有限公司上海代表处香港释胜(中国)咨询有限公司北京办事处香港华地国际实业有限公司上海代表处香港新鸿基(中国)有限公司上海代表处香港松华实业(亚洲)有限公司北京代表处香港松华实业(亚洲)有限公司上海代表处(香港)大福证券集团有限公司北京代表处昌惠有限公司北京办事处特力(香港)有限公司北京代表处香港三宝技术投资有限公司北京代表处香港天安中国投资有限公司驻广州办事处天安(上海)投资有限公司香港和宇发展有限公司北京代表处台湾中华征信所企业股份有限公司北京办事处乔讯电子(上海)有限公司长江企业股份有限公司上海办事处太平洋控股有限公司上海办事处速曜国际贸易(上海)有限公司绿点(天津)塑胶有限公司英属维尔京群岛英泰美国际有限公司上海代表处迈赖电子(上海)有限公司台湾波西亚有限公司北京办事处阿根廷阿何(秦皇岛)水产有限公司加拿大农业咨询有限公司加拿大新田种子公司加拿大小麦局北京办事处法国赛力事达股份公司北京代表处法国吉粮赛力事达玉米工业有限公司上海办事处法国瑞奇温室公司德国康尼麦克斯国际有限公司北京代表处德国KWS种子股份公司北京办事处百兴畜产品(天津)有限公司以色列农业发展集团有限公司以色利亚洲农业发展集团有限公司以色利海泽拉优质种子公司山东办事处荷兰赛贝科国际有限公司北京办事处荷兰泰高国际有限公司北京代表处荷兰温迪肯贸易有限公司北京代表处韩国北京新工鸵鸟养殖有限公司美商康家(天津)农产品有限公司英国时空有限公司北京代表处美国百绿有限公司北京代表处黑龙江史丹特畜牧综合加工有限公司美国美森耐公司上海有限公司美国PIC种猪改良国际集团中国分公司香港华兰咨询有限公司上海代表处香港世基顾问有限公司上海代表处香港威林干那有限公司上海代表处澳大利亚液化天然气有限公司北京代表处澳大利亚国际控股有限公司上海代表处澳大利亚迈创金属有限公司北京代表处澳大利亚泛澳国际投资有限公司澳大利亚力拓业有限公司澳大利亚西部矿业(中国)私人有限公司比利时艾科达欧中贸易集团有限公司上海百洛达金属有限公司英属维尔京群岛海湾资源有限公司上海代表处瑞奇科投资公司皇朝石油公司北京代表处加拿大泰斯科公司北京代表处加拿大康姆电信集团公司北京代表处法国液化空气公司北京代表处法国阿尔斯通上海代表处阿托菲纳(中国)投资有限公司法国电力公司亚太地区总部中国分部法国燃气公司北京代表处法国环球贸易公司北京代表处道达尔菲纳埃尔夫(中国)投资有限责任公司德固萨太平洋有限公司北京代表处德固萨太平洋有限公司上海代表处德国ETS有限公司北京代表处德国法特公司北京代表处德国费希特纳有限公司上海代表处德国鲁奇油气化公司北京代表处德国鲍希尔公司北京代表处德国鲁尔集团北京代表处希腊金属投资有限公司上海代表处金钦州丰产林有限公司伊朗国家石油公司上海代表处意大利C.L.D.A.有限公司公司上海代表处意大利达涅利公司北京代表处日本旭日产业株式会社上海代表处日本电源开发(株)北京事务所日立(中国)有限公司日本本间金属工业株式会社北京事务所日本新能源产业技术综合开发机构北京事务所三井物产(中国)有限公司新日本日铁株式会社北京代表处日本钢管(株)北京事务所马来西亚云顶杉原集团公司北京代表处蒙古国额尔登特矿业公司北京代表处荷兰壳牌(中国)有限公司上海办事处挪威埃肯公司北京代表处俄罗斯梅花股份有限公司北京办事处俄罗斯西西伯利亚钢材集团驻北京办事处沙特石油有限公司北京代表处香港威廉集团有限公司北京办事处P.C.C.(新加坡)私人有限公司北京代表处新加坡太平洋顶峰能源投资私人有限公司北京代表处三星物产(株)北京办事处韩国(株)世亚制钢北京办事处西班牙美耐莎有限公司北京办事处西班牙矿业发展公司北京代表处瑞典荣生(中国)有限公司北京联络处赫格纳斯(中国)有限公司ABB厦门华电高压开关有限公司汉纳德有限公司北京办事处泛亚班拿中国有限公司厦门代表办事处协联投资(中国)有限公司英国BP中国有限公司北京代表处英国艾斯普罗集团北京事处英国坦萨集团有限公司北京代表处英国五金太平洋有限公司广州办事处英国戎氏集团有限公司北京办事处爱依斯中国发电有限公司美铝亚洲公司北京办事处美国电力转换有限公司上海代表处美国A.R.M.物源公司北京办事处美国贝克休斯公司北京代表处美国宝安国际投资有限公司柏灵顿资源中国有限公司加德士(中国)投资有限公司上海分公司加德士华南投资有限公司加德士(中国)投资有限公司美国工商五金公司北京代表处埃克森美孚(中国)投资有限公司大连办事处埃克森美孚石油中国投资有限公司长春代表处埃克森美孚(中国)投资有限公司沈阳办事处绿源锦业环境投资顾问公司哈里伯顿国际有限公司美国合伯特兄弟有限公司北京办事处美国国际资源有限公司上海代表处美国国际联合公司上海代表处美国凯南麦特(中国)有限公司美国力可公司北京办事处美国奥伯格工业公司美国西方中国公司北京代表处美国帕姆克公司北京代表处美国特种矿物有限公司上海代表处美国SPS有限公司北京联络处中信泰富有限公司北京代表处香港中华电力(中国)有限公司北京代表处香港中华电力(中国)有限公司广州代表处香港中华电力(中国)有限公司上海代表处香港康密劳远东发展有限公司上海代表处香港康力斯亚洲有限公司广州办事处(原英国钢铁公司)香港欣切斯特(香港)有限公司(香港)捷美集团有限公司北京代表处香港金邦企业有限公司北京办事处基腾科技有限公司北京联络处香港龙显企业有限公司北京代表处香港埃赫曼中国有限公司上海代表处香港中华煤气(中国)有限公司广州办事处中向国际有限公司北京联络处台宝金属有限公司澳大利亚中国商贸促进有限公司上海代表处澳大利亚利普国际有限公司上海代表处澳大利亚泛澳国际投资有限公司奥地利格拉斯股份有限公司奥地利兰精股份公司北京代表处奥地利技术国际公司(奥钢联)上海联络处英属维尔京群岛万宝世纪有限公司上海代表处芬兰木业总公司上海代表处贝尔罗斯公司北京代表处法兰西水泥公司意大利水泥集团法国蓝屋进出口股份有限公司北京代表处欧西玛特公司北京代表处洁福(中国)有限公司法拉基屋面系统三水有限公司法拉基屋面系统(北京)有限公司法国乐华梅兰公司广州代表处法国皮尔·卡丹公司北京代表处法国圣戈班集团北京办事处圣戈班管道系统有限公司法国表面技术公司上海代表处法国西得乐有限公司北京办事处德国ACE公司北京联络处博世(中国)投资有限公司博世(中国)投资有限公司上海分公司德国康乐公司上海代表处德国康乐公司北京办事处佛山利发实业有限公司德国陆洲进出口股份有限公司上海代表处德国克朗兹一体有限公司上海代表处汉斯博士礼品(北京)有限公司德国汉斯格雅有限公司上海代表处德国萨克森州HEC/企业集团太原代表处德国赫美斯磨料有限公司北京办事处德商朗德有限公司上海代表处德国曼弗雷德-尼曼公司上海代表处曼盛国际贸易(上海)有限公司摩泽电器有限公司上海代表处德国奥尔夫贸易公司北京办事处奥斯本国际集团北京代表处德国P.C.C.有限公司北京代表处德国西普利纳中国代表处意大利萨巴夫有限公司上海代表处意大利塞柯中国公司北京代表处西蒂中国有限公司索科发有限公司北京代表处北京丰意德工贸有限公司日本同和矿业株式会社上海代表处圣戈班诺顿株式会社上海代表处日本佐藤金属株式会社上海代表处日本绿的流通中心-清巧株式会社清水建设株式会社北京事务所日本株式会社进和上海代表处住友电气工业(株)北京办事处日本住友橡胶工业株式会社北京事务所日本太阳工业株式会社日本株式会社高岛屋上海代表处日本高商株式会社太平洋水泥(中国)投资有限公司日本东陶机器(中国)有限公司日本JVC株式会社驻上海代表处马来西亚海欧(西安)实业有限公司马来西亚捷能系统亚洲有限公司上海代表处马来西亚谦木工业股份有限公司上海代表处阿克苏诺贝尔中国有限公司广州代表处阿克苏诺贝尔中国有限公司青岛代表处阿克苏诺贝尔中国有限公司上海代表处阿克苏诺贝尔油漆(中国)有限公司新加坡农业出口公司北京代表处新加坡豪登乐(新加坡)私人有限公司上海代表处新加坡奥多(上海)钢制品有限公司西班牙里海国际贸易公司南京办事处康明克斯矿山集团北京代表处西班牙法格工业有限公司上海代表处西班牙伊贝尔集团上海代表处西班牙钢管联合有限公司北京代表处阿维斯塔(亚太)有限公司北京代表处昆山阔福门业有限公司广州办事处昆山阔福门业有限公司上海办事处昆山阔福门业有限公司沈阳办事处泛瑞家居超市有限公司中国代表处瑞典SKF中国有限公司北京代表处瑞典SSAB钢板有限公司阿西米·布郎·勃法瑞(中国)有限公司西安分公司阿西米·布郎·勃法瑞中国投资有限公司上海分公司阿西米·布郎·勃法瑞投资(中国)有限公司重庆分公司大唐国际美国有限公司上海代表处美国哈泊国际公司北京代表处美国哈茨麦登股份公司上海代表处美国海文斯钢铁国际广州代表处美国罗比公司上海代表处美国铁姆肯公司上海代表处美国洽弗工具有限公司上海代表处美国亚士博科技有限公司上海代表处美国史丹利公司广州代表处香港会田香港有限公司上海代表处北京中伟家具有限公司香港标马远东有限公司广州代表处香港标马远东有限公司上海代表处正泰国际贸易(天津)有限公司丝宝实业发展(武汉)有限公司香港捷高(中国)有限公司上海代表处香港建联工程设备有限公司北京办事处香港康力斯亚洲有限公司北京代表处香港康力斯亚洲有限公司上海代表处香港迪臣发展有限公司北京代表处香港迪臣发展有限公司上海代表处香港瑞源国际公司北京代表处香港捷洲国际(香港)有限公司上海代表处香港高达创建有限公司上海代表处香港加冕国际有限公司上海代表处香港万美有限公司上海代表处美亿有限公司佛山办事处香港美而高亚洲有限公司上海代表处香港家耀有限公司上海代表处香港裕实国际有限公司北京代表处香港三永国际有限公司广州办事处香港崇威集团有限公司广州代表处香港德健投资有限公司上海代表处香港荷兰商泰勒(香港)有限公司应卡(香港)有限公司北京代表处香港华达(亚太)有限公司上海代表处艾马国际机电(北京)有限公司和成(中国)有限公司澳洲粮油食品国际(中国)有限公司澳洲粮油食品国际(中国)有限公司广州代表处澳洲粮油食品(上海)有限公司上海邦蒂国际贸易有限公司澳大利亚联合金赞有限公司澳大利亚永良国际有限公司加拿大利仑国际集团中国公司加拿大环球企业国际有限公司法国食品协会北京代表处法国食品协会上海代表处索普罗莫公司北京办事处华安肉类有限公司华安肉类有限公司肉类加工厂德国舒乐达公司上海代表处德国加斯特斯公司厦门代表处。

会前准备要缜密——访迈斯林集团市场总监Kathy Zhang女士

会前准备要缜密——访迈斯林集团市场总监Kathy Zhang女士何苇【期刊名称】《中国会展》【年(卷),期】2009(000)006【摘要】【案例】:近日,由西澳大利亚州驻华商务代表处主办、迈斯林集团协办的西澳大利亚州投资移民推介会在北京某酒店完美谢幕。

应邀出席会议的嘉宾有西澳州议会上院议长Hon Nick Griffiths先生及夫人一行5人,西澳大利亚州政府驻华商务代表处首席代表BJ Zhuang先生,西澳大利亚州政府驻华商务代表处高级商务经理Judy Zhu女士。

中国驻悉尼总领事馆商务参赞、前中国商务部外事司司长朱小川先生及澳大利亚贸易委员会北方区投资总监Grace Ji女士也应邀出席。

嘉宾的规格之高在移民咨询行业内是少见的。

也正因为嘉宾的权威性,吸引了有意投资、移民西澳的商务人士近500人参会。

会场,来宾们热情高涨,表现出了投资或移民西澳州的浓厚兴趣。

可以说,这次会议从策划、推广到组织实施,堪称该类会议之经典。

【总页数】2页(P34-35)【作者】何苇【作者单位】【正文语种】中文【中图分类】F719【相关文献】1.life's DHA来自纯天然的安全“脑黄金”——访荷兰皇家帝斯曼集团营养科学事务宣传部科学家Sheila Gautier女士 [J], 王丹蕾2.乘风破浪,勇往直前--访佳斯迈威(上海)非织造布有限公司总经理刘榕女士 [J],3.根植沃土志比鸿鹄──访首信集团总裁杨廉斯女士 [J], 乔楠4.做汽车制造业的长期伙伴——访奈尔斯-西蒙斯-赫根赛特集团公司资深技术顾问Helfried Schumann先生及中国首席代表周荐女士 [J], 龚淑娟5.惠普:全力助力中国产品质量电子监管——对话惠普公司打印及成像系统集团副总裁惠普公司特殊打印系统部总经理Kathy Tobin女士 [J], 卢军因版权原因,仅展示原文概要,查看原文内容请购买。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。