Dendritic-cell genealogy

APC:即抗原提呈细胞

蛋白酶体:通常以20S形式普遍存在于各

种生物体细胞内,在内源性抗原的降解中

发挥着重要的作用,主要负责将溶酶体外 的蛋白抗原降解为多肽。

MHC-II 提呈Ag, 激活LC,

结合TC,

First signal:

second signal:

MAF/IFN-,

LPS/IFN-,

第十一章

抗原提呈细胞与抗原的 处理及提呈

第十一章 抗原提呈细胞与抗原的处理及提呈 • 第一节 抗原提呈细胞的种类与特点 • 第二节 抗原的处理和提呈

基本概念

辅佐细胞(accessory cells) :在胸腺依 赖性抗原诱导B淋巴细胞产生抗体的过程中, 不仅需要T、B淋巴细胞的协同作用,还需 要另一类细胞的协助,遂将该类细胞称为辅 佐细胞。

TAP:即抗原加工相关转运物,是由TAPl 和TAP2组成的一种异二聚体。TAPl和 TAP2各跨越内质网膜6次,共同形成一个 “孔”样结构,依赖ATP对多肽进行主动 转运。

DC:即树突状细胞,细胞呈树突状,膜表 面高表达MHC II类分子,能移行至淋巴器 官并刺激初始T细胞活化增殖,有相对特异 性表面标志的一类细胞,是体内功能最强 的专职性抗原提呈细胞。

主要专职性抗原提呈细胞

第一节 抗原提呈细胞的种类与特点

一、树突状细胞(dendritic cell ,DC)

DC 能够显著刺激初始T细胞增殖,而MΦ、B 细胞仅能刺激已活化的或记忆性T细胞,故DC是机 体适应性T细胞免疫应答的始动者;DC还表达丰富 的免疫识别受体,能敏感地识别入侵的病原体,通 过快速地释放大量CK参与固有免疫应答,故DC也 被视为连接固有免疫和适应性免疫的“桥梁”。

CD4+T细胞极化在炎症性疾病中作用的研究进展

中国免疫学杂志2023 年第 39 卷CD4+T 细胞极化在炎症性疾病中作用的研究进展①晏伟② 薛丹风 江淑玲② 凌鑫萍② 李娜 (南昌大学第一附属医院,南昌 330006)中图分类号 R392 文献标志码 A 文章编号 1000-484X (2023)12-2684-06[摘要] CD4+T 细胞具有极强的可塑性,其可极化为Th1、Th2、Th17和Treg 细胞等各种效应细胞,进而参与多种炎症性疾病的调控,其极化既可促进疾病发生发展,亦可抑制疾病进展。

在不同疾病或同一疾病的不同阶段,其极化方向也可能不同。

因此,本综述旨在总结并探讨CD4+T 细胞极化在不同炎症性疾病中的调控作用及其对疾病防治的意义。

[关键词] CD4+T 细胞;极化;炎症Research progress on role of CD4+T cell polarization in inflammatory diseasesYAN Wei , XUE Danfeng , JIANG Shuling , LING Xinping , LI Na. The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang Univer⁃sity , Nanchang 330006, China[Abstract ] CD4+T cells have strong plasticity and can be polarized intovarious effector cells such as Th1, Th2, Th17 and Tregcells. Then they participate in the regulation of various inflammatory diseases. Its polarization can not only promote development of disease , but also inhibit progression of disease. Direction of polarization may also be different in different diseases or in different stages of the same disease. Therefore , this review aims to summarize and explore the regulatory role of CD4+T cell polarization in different inflam⁃matory diseases and its significance for disease prevention and treatment.[Key words ] CD4+T cells ;Polarization ;Inflammation1 CD4+T 细胞极化概述CD4+T 细胞向特定T 细胞表型的特定细胞分化被称为CD4+T 细胞极化,其在机体炎症调节过程中发挥重要作用[1-2]。

Mouse and human dendritic cell subtypes

REVIEWSDendritic cells (DCs) are a sparsely distributed,migra-tory group of bone-marrow-derived leukocytes that are specialized for the uptake,transport,processing and pre-sentation of antigens to T cells 1–3.At an ‘immature’stage of development,DCs act as sentinels in peripheral tis-sues,continuously sampling the antigenic environment (FIG.1).Any encounter with microbial products or tissue damage initiates the migration of the DCs to lymph nodes (LNs).The antigenic sample at the time of the DANGER ,including any microbial products,is processed and fixed on the DC surface as peptides that are pre-sented by major histocompatibility complex (MHC)molecules.The DCs also upregulate the co-stimulatory molecules that are required for effective interaction with T cells.In the LNs,the now-mature DCs efficiently trigger an immune response by any T cells with a receptor that is specific for the foreign-peptide–MHC complexes on the DC surface.Immunoregulation by DCsDCs as determinants of tolerance.The model of DCs as natural ADJUV ANTS that promote the immune response to foreign antigens has been modified after the realization that the antigen-presenting cells (APCs) that are involved in immunity must also be involved in tolerance to self-antigens.Central tolerance of T cells in the thy-mus,which is achieved by inducing the apoptotic death of potentially self-reactive T cells,is mediated by thymic DCs 4.Are these DCs specially armed to induce T-celldeath rather than proliferation? The evidence so far indi-cates that it is the stage of T-cell differentiation,rather than the type of DC,that determines the negative out-come of this interaction 5.Nevertheless,thymic DCs do have a life history that differs from the standard model,because most of them derive from an intrathymic pre-cursor and develop and die within the thymus 6.A non-migratory behaviour seems to be more appropriate to such DCs,the function of which is to present self-antigens rather than to collect foreign antigens.However,not all self-reactivity is eliminated from the T-cell receptor repertoire by central tolerance 7.Because the DCs that carry foreign antigens into the LNs must also be carrying self-antigens 8,the DCs themselves are likely to be responsible for tolerance as well as immunity.Tolerance to self-antigens in vivo seems to require an active,proliferative response by the self-antigen-reactive T cells 9.Accordingly,the prolifera-tive responses of T cells to DCs in culture are as likely to model the initiation of tolerance as the initiation of a protective immune response.Two general mechanisms have been proposed by which DCs might maintain peripheral tolerance.The first is that a subtype of specialized regulatory DCs is involved;there is some evidence for such DCs,but no consensus 10–12.The second is that all DCs have a capac-ity for initiating tolerance or immunity,the distinction depending on the maturation or activation state of the DC (FIG.1).The original concept was that IMMATURE DCSMOUSE AND HUMAN DENDRITIC CELL SUBTYPESKen Shortman* and Yong-Jun Liu ‡Dendritic cells (DCs) collect and process antigens for presentation to T cells, but there are many variations on this basic theme. DCs differ in the regulatory signals they transmit, directing T cells to different types of immune response or to tolerance. Although many DC subtypes arise from separate developmental pathways, their development and function are modulated by exogenous factors. Therefore, we must study the dynamics of the DC network in response to microbial invasion. Despite the difficulty of comparing the DC systems of humans and mice, recent work has revealed much common ground.*The Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research,Victoria 3050,Australia.‡DNAX Research Institute,Palo Alto,California 94304,USA.e-mails: shortman@.au,yong-jun.liu@DOI:10.1038/nri746R E V I E W SFigure 3 | CD8+dendritic cells (DCs) isolated from mouse spleen.The DCs were extracted and enriched from mouse spleen42and then sorted as CD11c+CD8α+cells. The sorted cells were incubated overnight in culture medium, which activates the DCs. Surface major histocompatibility complex class-II (MHC-II) molecules were then stained red (with anti-R E V I E W S10.Grohmann, U. et al.IL-6 inhibits the tolerogenic function ofCD8α+dendritic cells expressing indoleamine2,3-dioxygenase. J. Immunol. 167, 708–714 (2001).11.Süss, G. & Shortman, K. A subclass of dendritic cells killsCD4 T cells via Fas/Fas-ligand-induced apoptosis. J. Exp.Med. 183, 1789–1796 (1996).12.Fazekas de St Groth, B. F. The evolution of self-tolerance: anew cell arises to meet the challenge of self-reactivity.Immunol. Today19, 448–454 (1998).13.Dhodapkar, M. V., Steinman, R. M., Krasovsky, J., Munz, C.& Bhardwaj, N. Antigen-specific inhibition of effector T cellfunction in humans after injection of immature dendritic cells.J. Exp. Med. 193, 233–238 (2001).14.Steinman, R. M., Turley, S., Mellman, I. & Inaba, K. Theinduction of tolerance by dendritic cells that have capturedapoptotic cells. J. Exp. Med. 191, 411–416 (2000).A model of how DCs might mediate self-tolerance.15.Roncarolo, M. G., Levings, M. K. & Traversari, C.Differentiation of T regulatory cells by immature dendriticcells. J. Exp. Med. 193, 5–9 (2001).16.Albert, M. L., Jegathesan, M. & Darnell, R. B. Dendritic cellmaturation is required for the cross-tolerization of CD8+Tcells. Nature Immunol. 11, 1010-1017 (2001).A new look at how DCs determine tolerance versusimmunity.17.Shortman, K. & Heath, W. R. Immunity or tolerance? That isthe question for dendritic cells. Nature Immunol. 2, 988–989 (2001).18.Hartmann, G., Weiner, G. J. & Krieg, A. M. CpG DNA: apotent signal for growth, activation, and maturation ofhuman dendritic cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA96,9305–9310 (1999).Bacterial DNA as a danger signal for DCs.19.Sparwasser, T. et al.Bacterial DNA and immunostimulatoryCpG oligonucleotides trigger maturation and activation ofmurine dendritic cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 28, 2045–2054(1998).20.Verdijk, R. M. et al.Polyriboinosinic polyribocytidylic acid(poly(I:C)) induces stable maturation of functionally activehuman dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 163, 57–61 (1999).21.Singh-Jasuja, H. et al.The heat shock protein gp96 inducesmaturation of dendritic cells and downregulation of itsreceptor. Eur. J. Immunol. 30, 2211–2215 (2000).22.Sauter, B. et al.Consequences of cell death: exposure tonecrotic tumor cells, but not primary tissue cells or apoptotic cells, induces the maturation of immunostimulatory dendritic cells. J. Exp. Med. 191, 423–434 (2000).23.Gallucci, S., Lolkema, M. & Matzinger, P. Natural adjuvants:endogenous activators of dendritic cells. Nature Med.5,1249–1255 (1999).24.Medzhitov, R. & Janeway, C., Jr. Innate immune recognition:mechanisms and pathways. Immunol. Rev. 173, 89–97(2000).T oll and other receptors for microbial products.25.Kadowaki, N. et al.Subsets of human dendritic cellprecursors express different T oll-like receptors and respond to different microbial antigens. J. Exp. Med. 194, 863–870(2001).A basis for the varied responses of different DClineages.26.Mellman, I. & Steinman, R. M. Dendritic cells: specializedand regulated antigen processing machines. Cell106,255–258 (2001).27.Villadangos, J. A. Presentation of antigens by MHC class IImolecules: getting the most out of them. Mol. Immunol. 38, 329–346 (2001).28.Heath, W. & Carbone, F. R. Cross-presentation in viralimmunity and self-tolerance. Nature Rev. Immunol.1,126–134 (2001).29.Shen, Z., Reznikoff, G., Dranoff, G. & Rock, K. L. Cloneddendritic cells can present exogenous antigens on bothMHC class I and class II molecules. J. Immunol. 158,2723–2730 (1997).30.Albert, M. L., Sauter, B. & Bhardwaj, N. Dendritic cellsacquire antigen from apoptotic cells and induce class I-restricted CTLs. Nature392, 86–89 (1998).31.Svensson, M., Stockinger, B. & Wick, M. J. Bone marrow-derived dendritic cells can process bacteria for MHC-I andMHC-II presentation to T cells. J. Immunol. 158, 4229–4236 (1997).32.Den Haan, J. M. M., Lehar, S. M. & Bevan, M. J. CD8+butnot CD8−dendritic cells cross-prime cytotoxic T cells in vivo.J. Exp. Med. 192, 1685–1695 (2000).First identification of a specialized cross-presentingAPC.33.Pooley, J. L., Heath, W. R. & Shortman, K. Cutting edge:intravenous soluble antigen is presented to CD4 T cells by CD8+dendritic cells, but cross-presented to CD8 T cellsby CD8+dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 166, 5327–5330(2001).34.Moser, M. & Murphy, K. M. Dendritic cell regulation ofTH1–TH2 development. Nature Immunol. 1, 199–205 (2000).35.Schulz, O. et al.CD40 triggering of heterodimeric IL-12 p70production by dendritic cells in vivo requires a microbialpriming signal. Immunity13, 453–462 (2000).36.Hochrein, H. et al.Interleukin-4 is a major regulatorycytokine governing bioactive interleukin-12 production bymouse and human dendritic cells. J. Exp. Med. 192,823–833 (2000).ngenkamp, A., Messi, M., Lanzavecchia, A. & Sallusto, F.Kinetics of dendritic cell activation: impact on priming TH1,TH2, and nonpolarized T cells. Nature Immunol. 1, 311–316(2001).38.D’Ostiani, C. F. et al.Dendritic cells discriminate betweenyeasts and hyphae of the fungus Candida albicans.Implications for initiation of T helper cell immunity in vitro andin vivo. J. Exp. Med. 191, 1661–1674 (2000).Subtle discrimination by DCs and flexibility offunction.39.Iwasaki, A. & Kelsall, B. L. Localization of distinct Peyer’spatch dendritic cell subsets and their recruitment bychemokines macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP)-3α,MIP-3β, and secondary lymphoid organ chemokine. J. Exp.Med. 191, 1381–1394 (2000).40.Anjuère, F. et al.Definition of dendritic cell subpopulationspresent in the spleen, Peyer’s patches, lymph nodes, andskin of the mouse. Blood93, 590–598 (1999).41.Henri, S. et al.The dendritic cell populations of mouselymph nodes. J. Immunol. 167, 741–748 (2001).42.Vremec, D., Pooley, J., Hochrein, H., Wu, L. & Shortman, K.CD4 and CD8 expression by dendritic cell subtypes inmouse thymus and spleen. J. Immunol. 164, 2978–2986(2000).43.Reis e Sousa, C. et al.In vivo microbial stimulation inducesrapid CD40 ligand-independent production of interleukin 12by dendritic cells and their redistribution to T cell areas.J. Exp. Med. 186, 1819–1829 (1997).44.De Smedt, T. et al.Regulation of dendritic cell numbers andmaturation by lipopolysaccharides in vivo. J. Exp. Med. 184,1413–1424 (1996).45.Inaba, K. et al.Granulocytes, macrophages, and dendriticcells arise from a common major histocompatibility complexclass II-negative progenitor in mouse bone marrow. Proc.Natl Acad. Sci. USA90, 3038–3042 (1993).Myeloid origin of DCs.46.Izon, D. et al.A common pathway for dendritic cell and earlyB cell development. J. Immunol. 167, 1387–1392 (2001).47.Bjorck, P. & Kincade, P. W. CD19+pro-B cells can give riseto dendritic cells in vitro. J. Immunol. 161, 5795–5799(1998).48.Radtke, F. et al.Notch1 deficiency dissociates theintrathymic development of dendritic cells and T cells.J. Exp. Med. 191, 1085–1094 (2000).49.Rodewald, H. R., Brocker, T. & Haller, C. Developmentaldissociation of thymic dendritic cell and thymocyte lineagesrevealed in growth factor receptor mutant mice. Proc. NatlAcad. Sci. USA96, 15068–15073 (1999).50.Traver, D. et al.Development of CD8α+dendritic cells from acommon myeloid progenitor. Science290, 2152–2154(2000).51.Manz, M. G., Traver, D., Miyamoto, T., Weissman, I. L. &Akashi, K. Dendritic cell potentials of early lymphoid andmyeloid progenitors. Blood97, 3333–3341 (2001).52.Wu, L., D’Amico, A., Hochrein, H., Shortman, K. & Lucas, K.Development of thymic and splenic dendritic cellpopulations from different hemopoietic precursors. Blood98, 3376–3382 (2001).References 51 and 52 show that the DC subtype is notpredetermined by the early haematopoietic precursorcell.53.Saunders, D. et al.Dendritic cell development in culture fromthymic precursor cells in the absence ofgranulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor. J. Exp.Med. 184, 2185–2196 (1996).54.O’Keeffe, M. et parison of the effects ofadministration of Propenipoietin-1, Flt-3 ligand, G-CSF andPEGylated GM-CSF on dendritic cell subsets in the mouse.Blood(in press).55.Wu, L., Nichogiannopoulou, A., Shortman, K. &Georgopoulos, K. Cell-autonomous defects in dendritic cellpopulations of Ikaros mutant mice point to a developmentalrelationship with the lymphoid lineage. Immunity7, 483–492(1997).56.Wu, L. et al.RelB is essential for the development ofmyeloid-related CD8α−dendritic cells but not of lymphoid-related CD8α+dendritic cells. Immunity9, 839–847 (1998).57.Guerriero, A., Langmuir, P. B., Spain, L. M. & Scott, E. W.PU.1 is required for myeloid-derived but notlymphoid-derived dendritic cells. Blood95, 879–885(2000).58.Kamath, A. et al.The development, maturation and turnoverrate of mouse spleen dendritic cell populations. J. Immunol.165, 6762–6770 (2000).59.Randolph, G. J., Inaba, K., Robbiani, D. F., Steinman, R. M.& Muller, W. A. Differentiation of phagocytic monocytes intolymph node dendritic cells in vivo. Immunity11, 753–761(1999).60.Asselin-Paturel, C. et al.Mouse type I IFN-producing cellsare immature APCs with plasmacytoid morphology. NatureImmunol. 2, 1144–1150 (2001).The identification of the mouse equivalent of humanplasmacytoid DC precursor.61.Nakano, H., Yanagita, M. & Gunn, M. D. CD11c+B220+Gr-1+cells in mouse lymph nodes and spleen displaycharacteristics of plasmacytoid dendritic cells. J. Exp. Med.194, 1171–1178 (2001).62.Bjorck, P. Isolation and characterization of plasmacytoiddendritic cells from Flt3 ligand and granulocyte–macrophagecolony-stimulating factor-treated mice. Blood98,3520–3526 (2001).63.Maldonado-López, R. et al.CD8α+and CD8α−subclassesof dendritic cells direct the development of distinct T helpercells in vivo. J. Exp. Med. 189, 587–592 (1999).64.Pulendran, B. et al.Distinct dendritic cell subsetsdifferentially regulate the class of immune response in vivo.Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA96, 1036–1041 (1999).References 63 and 64 provide first evidence thatdifferent DC subtypes can determine the nature ofT-cell responses.65.Pulendran, B., Banchereau, J., Maraskovsky, E. &Maliszewski, C. Modulating the immune response withdendritic cells and their growth factors. Trends Immunol. 22,41–47 (2001).66.Hochrein, H. et al.Differential production of IL-12, IFN-α,and IFN-γby mouse dendritic cell subsets. J. Immunol. 166,5448–5455 (2001).67.Kronin, V. et al.Differential effect of CD8+and CD8−dendriticcells in the stimulation of secondary CD4+T cells.Int. Immunol. 13, 465–473 (2001).68.Kronin, V. et al.A subclass of dendritic cells regulates theresponse of naive CD8 T cells by limiting their IL-2production. J. Immunol. 157, 3819–3827 (1996).69.Winkel, K. D., Kronin, V., Krummel, M. F. & Shortman, K. Thenature of the signals regulating CD8 T cell proliferativeresponses to CD8α+or CD8α−dendritic cells. Eur. J.Immunol. 27, 3350–3359 (1997).70.Kronin, V., Hochrein, H., Shortman, K. & Kelso, A. Theregulation of T cell cytokine production by dendritic cells.Immunol. Cell Biol. 78, 214–223 (2000).71.O’Connell, P. J. et al.CD8α+(lymphoid-related) and CD8α−(myeloid) dendritic cells differentially regulate vascularizedorgan allograft survival. Transplant Proc. 33, 94 (2001).72.McIlroy, D. et al.Infection frequency of dendritic cells andCD4+T lymphocytes in spleens of human immunodeficiencyvirus-positive patients. J. Virol. 69, 4737–4745 (1995).73.Vandenabeele, S., Hochrein, H., Mavaddat, N., Winkel, K. &Shortman, K. Human thymus contains 2 distinct dendriticcell populations. Blood97, 1733–1741 (2001).74.Bendriss-Vermare, N. et al.Human thymus contains IFN-α-producing CD11c−, myeloid CD11c+, and matureinterdigitating dendritic cells. J. Clin. Invest. 107, 835–844(2001).75.Young, J. W., Szabolcs, P. & Moore, M. A. S. Identification ofdendritic cell colony-forming units among normal humanCD34+bone marrow progenitors that are expanded by c-kitligand and yield pure dendritic cell colonies in the presence ofgranulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor andtumor necrosis factor α. J. Exp. Med. 182, 1111–1119(1995).76.Caux, C. & Banchereau, J. in In vitro Regulation of DendriticCell Development and Function (eds A. Whetton & J.Gordon) 263–301 (Plenum Press: London, 1996).77.Caux, C. et al.CD34+hematopoietic progenitors fromhuman cord blood differentiate along two independentdendritic cell pathways in response to GM–CSF+TNFα.J. Exp. Med. 184, 695–706 (1996).Culture system showing two pathways of human DCdevelopment.78.Strunk, D., Egger, C., Leitner, G., Hanau, D. & Stingl, G.A skin homing molecule defines the Langerhans cellprogenitor in human peripheral blood. J. Exp. Med. 185,1131–1136 (1997).79.Strobl, H. et al.TGF-β1 promotes in vitro development ofdendritic cells from CD34+hemopoietic progenitors.J. Immunol. 157, 1499–1507 (1996).80.Borkowski, T. A., Letterio, J. J., Farr, A. G. & Udey, M. C.A role for endogenous transforming growth factor β1 inLangerhans cell biology: the skin of transforming growthfactor β1 null mice is devoid of epidermal Langerhans cells.J. Exp. Med. 184, 2417–2422 (1996).Copyright of Nature Reviews Immunology is the property of Nature Publishing Group and its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use.。

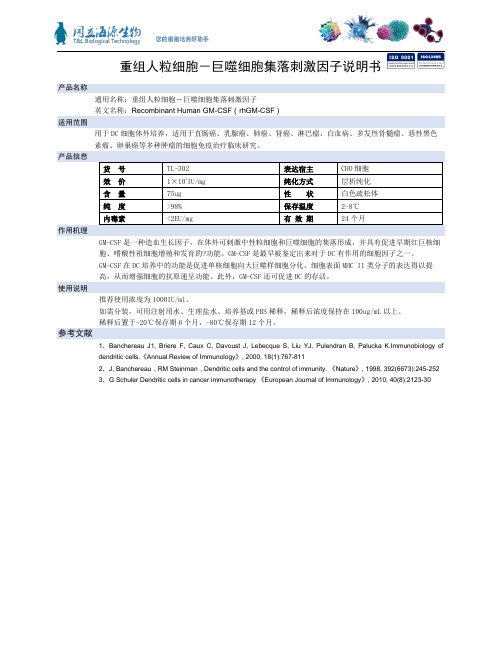

GM-CSF中文

重组人粒细胞-巨噬细胞集落刺激因子说明书产品名称通用名称:重组人粒细胞-巨噬细胞集落刺激因子英文名称:Recombinant Human GM-CSF(rhGM-CSF)适用范围用于DC细胞体外培养,适用于直肠癌、乳腺癌、肺癌、肾癌、淋巴瘤、白血病、多发性骨髓瘤、恶性黑色GM-CSF是一种造血生长因子,在体外可刺激中性粒细胞和巨噬细胞的集落形成,并具有促进早期红巨核细胞、嗜酸性祖细胞增殖和发育的?功能。

GM-CSF是最早被鉴定出来对于DC有作用的细胞因子之一。

GM-CSF在DC培养中的功能是促进单核细胞向大巨噬样细胞分化,细胞表面MHC II类分子的表达得以提高,从而增强细胞的抗原递呈功能。

此外,GM-CSF还可促进DC的存活。

使用说明推荐使用浓度为1000IU/ml。

如需分装,可用注射用水、生理盐水、培养基或PBS稀释,稀释后浓度保持在100ug/mL以上。

稀释后置于-20℃保存期6个月,-80℃保存期12个月。

参考文献1、Banchereau J1, Briere F, Caux C, Davoust J, Lebecque S, Liu YJ, Pulendran B, Palucka K.Immunobiology ofdendritic cells.《Annual Review of Immunology》, 2000, 18(1):767-8112、J, Banchereau,RM Steinman,Dendritic cells and the control of immunity. 《Nature》, 1998, 392(6673):245-2523、G Schuler Dendritic cells in cancer immunotherapy 《European Journal of Immunology》, 2010, 40(8):2123-30。

长链非编码RNA核旁斑组装转录本1(NEAT1)在免疫相关性疾病中的研究进展

细胞与分子免疫学杂志(Chin J Cell Mol Immunol )2020, 36( 12)1141•综述• 文章编号:1007 -8738(2020)12 -1141 -04长链非编码RNA 核旁斑组装转录本1 ( NEAT1)在免疫相关性疾病中的 研究进展张鑫',任启伟S 董冠军彳* ('潍坊医学院医学检验学院,潍坊医学院临床检验诊断学山东省“十二五”高校重点实验室, 山东潍坊261053; 2济宁医学院基础医学院病理生理学教研室,山东济宁272067;'济宁医学院基础医学院免疫学与分子医学 研究所,泰山学者实验室,山东济宁272067)收稿日期:2020-09 -20;接受日期:2020-11 -24基金项目:国家自然科学基金(81601426);济宁医学院青年基金(JYQ2011KM015)作者简介:张鑫(1994-),女,山东青岛人,硕士研究生Tel : 130****8582 ; E-mail : kaimenfanggou@ 126. com*通讯作者,董冠军,E-mail : guanjun0323@ mail. jnmc. edu. cn[摘要]严格调控免疫反应是有效清除病原体和防止过度炎症的基础。

核旁斑组装转录本l(NEATl)是近年来被广泛关注的参与调控免疫反应的长链非编码RNA 。

已证实,NEAT1在免疫相关性疾病中异常表达(多数是上调),如脓毒症、炎症性肠病、 自身免疫性疾病及病毒感染。

然而,其在疾病发病进程的作用却错综复杂。

在机制上,主要作为微小RNA (miRNA)海绵来抑 制miRNA 与目标mRNA 之间的相互作用,也可以影响核旁斑介导的基因表达调控。

我们总结了 NEAT1在免疫相关性疾病中的表达变化及作用,重点分析其调控免疫细胞分化和功能的机制,为人们理解NEAT1在免疫相关性疾病中的作用提供理论依据。

[关键词]核旁斑组装转录本KNEAT1);感染;炎症;自身免疫性疾病;综述[中图分类号]R392.9, R593.2, G353.ll [文献标志码]A近年来,微小RNA(microRNA, miRNA)和长链非 编码 RNA(long non-coding RNA, IncRNA)在免疫系统应 答和癌症免疫治疗过程中发挥重要作用。

银屑病

pDCs :当活化或者濒死表皮细胞释放的自身 DNA 和RNA片 段与抗菌肽 LL37 形成复合物,刺激 pDCs,产生大量的干扰 素 α( IFN-α) ,异常产生的IFN是病理性自身免疫现象的主要 原因,主要诱导了外周髓性树突状细胞( mDCs )的不断成 熟,进而活化自身免疫性T细胞,导致皮肤炎症性皮损形成。 抗菌肽LL37:其作为天然免疫的重要组成部分,在皮肤中呈 诱导性表达。其在银屑病皮损中的过度表达是银屑病皮损中 pDCs活化的关键因素。

mDCs :这些细胞可能是在受到趋化刺激后从循环中迁移至 皮肤产生 IFN-α 可诱导型 NO 合酶( iN-Os) ,并且促进 Th 细 胞(辅助性T细胞)亚群的分化而起作用。 干扰素调节的DC( INF—DCs): 是近年来发现 一种新型的树 突状细胞,它具有pDCs、mDCs 和 NK 细胞的特征,TLR(Toll 样受体)与表皮细胞释放的自身RNA结合促进INF-DCs成熟, 产生大量 IL-1β、IL- 6、IL-12、TNF-α 而发挥作用。

四、临床表现

1.寻常型银屑病:为最常见的一型,多急性发病。典型表现 为境界清楚、形状大小不一的红斑,周围有炎性红晕。稍有 浸润增厚。表面覆盖多层银白色鳞屑。鳞屑易于刮脱,刮净 后淡红发亮的半透明薄膜,刮破薄膜可见小出血点(Auspitz 征)。 在其发展过程中,根据其皮损形态可分为点滴状、钱币状银 屑病、地图状、环状及带状银屑病、泛发性银屑病、湿疹样 银屑病、脂溢性皮炎样银屑病、扁平苔癣样银屑病、慢性肥 厚性银屑病及疣状银屑病。 还可根据发病部位及季节不同而进一步分类。

(2)巨噬细胞:

有研究表明通过免疫染色可以发现 银屑病样皮损中巨噬细胞 的活化及聚集,一旦巨噬细胞被激活后就可独立于CD4+T细 胞诱导银屑病样皮损的产生。

免疫细胞-幻灯片-(3)(1)

主要生物学功能包括:(1)细胞毒作用, 可识别和杀伤感染细胞和肿瘤细胞;(2) 免疫调节作用:活化后释放IL-1、IL-2、 IL-3、IL-4、IFN-γ、TNF等细胞因子,调 节免疫应答

4.Th 、 Tc、Treg

Th细胞 根据分泌细胞因子的不同分为 Th1、Th2、Th3和Th17。Th1细胞偏向于 分泌IL-2和IFNγ;Th2细胞偏向于分泌IL-4、 IL-5 、 IL-6 、 IL-10 ; Th3 细 胞 分 泌 TGF-β 发挥负调节作用;Th17分泌IL-17

磷脂酰丝氨酸

Toll样受体:识别G+菌肽聚糖、磷壁酸和病毒RNA

巨噬细胞表面受体

调理性受体:IgG Fc受体、补体受 体

细胞因子受体

巨噬细胞的主要生物学功能

识别、清除病原体等抗原性异物 参与和促进炎症 杀伤肿瘤和病毒感染的靶细胞 加工提呈抗原并启动适应性 免疫调节作用

二、树突状细胞

5.Fc受体 成熟B细胞表面可表达IgG的Fc

的受体,与抗原-抗体复合物中IgG的Fc段 结合,有利于B细胞对抗原的捕获和识别。

6.MHC分子 MHC-Ⅰ和MHC-Ⅱ分子

7.丝裂原受体 美洲商陆和LPS的受体

(三) B细胞亚群及其功能

根据CD5的表达与否分为:B-1和B-2细胞 B-1细胞:产生于个体发育早期;表达CD5与

树突状细胞

Department of Immunology

树突状细胞功能

提呈抗原与免疫激活作用 免疫调节作用 免疫耐受的维持与诱导

三、NK 细胞

自然杀伤细胞(natural killer cells,NK) 来源于骨髓淋巴样干细胞,是不同于T、B 淋巴细胞的第三类淋巴细胞。

树突状细胞简介

可有效诱导巢居的静息性幼稚T细胞发生增生。

2. DC的表面标志

DC表面表达与病原微生物结合的受体(PRR)、FcR 等,

参与捕获抗原和免疫复合物。 DC 高表达 B7-1 和 B7-2 ,二者与 T 细胞表面 CD28/CTLA-4 相互作用,这是DC高效提呈外源性抗原,并提供T细胞第二 活化信号的必要分子基础。

志和形态各异,但一般均高表达MHC-II类分子,具有较强

的摄取抗原的能力,能在体外自发地与 T 细胞形成 DC-T 细 胞簇,激活未致敏T细胞,启动初次免疫应答。

按DC的来源,可分为淋巴样DC和髓样DC

淋巴样DC主要分布于淋巴结、脾脏、粘膜相关组织中的 淋巴滤泡生发中心,主要与B淋巴细胞功能有关。 髓样DC主要分布于T细胞富含区,与T细胞功能有关。按 其分布部位又可分为:

③流出淋巴液和血液中成熟过程中的DC;

④次级淋巴组织中的成熟DC。

近年研究发现, CD34+HPC 在 GM-CSF 和 TNF-α作用下沿 三条不同的路线向成熟的DC分化。

CD34+HPC 分化为 CD1a+ 前体 DC ,分化成含 Birbeck 颗粒、

表达 Lag 抗原、 E-Cadherin 的郎格罕氏细胞 (Langhams cell,LC)和间质DC。

FDC是淋巴结浅皮质区和淋巴滤泡内的重要APC,其表

面具有树枝状突起。 FDC 是参与再次免疫应答的重要细胞,它主要通过表 面的FcR和CR将免疫复合物结合在细胞膜上,进而提交给B 细胞。 FDC在抗原提呈过程中的作用:

使免疫细胞识别以免疫复合物形式存在的抗原。

2.并指状细胞 (interdigitating cell, IDC)

HLH发病机制和诊治进展

推荐采用噬血性淋巴组织细胞增生症(HLH)这一命名, 突出了淋巴细胞和组织细胞增生和噬血细胞现象这两个关 键性组织病理学特点

历史演进 (historical milestones in HLH research)

Scott RobbSmith (1939): histiocytic medullary reticulosis Farquhar Claireaux (1952): familial hemaphagocytic reticulosis Rappaport (1969): malignant histiocytosis (MH) Risdall (1979):virus-associated hemophagocytic syndrome (HPS)

Perforin gene mutation and familial HLH: most common (up to 40%)

Stepp SE, et al. Perforin gene defects in familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Science.1999;286:1957-1959.

Perforin mutations in a cohort of 30 Chinese children with EBV-HLH

30 EBV-HLH, including 14 boys and 16 girls admitted to BCH from 2006-2008.

3 heterozygous missense mutation of PRF1 gene (10%)

我国尚无关于儿童HLH流行病学的统计数据

发病年龄:70%家族性HLH于2岁前发病,但也可迟至8岁起病

ADAMTSL5与银屑病

ADAMTSL5与银屑病发表时间:2018-04-19T13:10:31.387Z 来源:《医药前沿》2018年4月第12期作者:袁育林杨霞芳[导读] 可以成为银屑病中产生IL-17的CD8+ T细胞的活化抗原。

对ADAMTSL5的深入研究为阐明银屑病发病机制及靶向治疗带来了新希望。

(南宁市广西壮族自治区人民医院检验科广西南宁 530021)【中图分类号】R758.63 【文献标识码】A 【文章编号】2095-1752(2018)12-0014-03银屑病是一种常见的慢性复发性炎症性皮肤病。

其发病机制非常复杂,包括遗传、环境、免疫等多种因素参与其中。

虽然基于广泛的遗传,免疫和药理学证据,T细胞在银屑病发病机制中的作用已被广泛接受,但免疫系统在银屑病中被触发的机制仍然是一个迷。

银屑病易感基因座PSORS1上的HLA-C*06:02(6p21.33)是银屑病主要风险等位基因。

最近的研究显示ADAMTS样蛋白5(ADAMTSL5)作为Vα3S1/Vβ13S1TCR的HLA-C*06:02呈递的黑素细胞自身抗原,可导致产生IL-17的T细胞的活化,从而引起银屑病发病。

本文将对这一新鉴定的银屑病的自身抗原作简要综述。

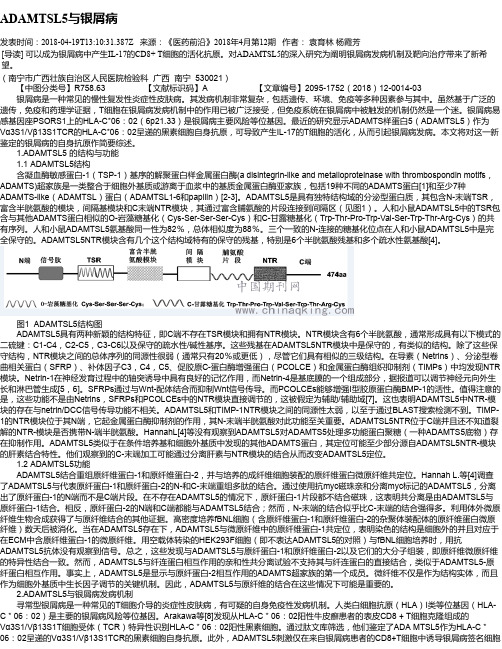

1.ADAMTSL5 的结构与功能1.1 ADAMTSL5结构含凝血酶敏感蛋白-1(TSP-1)基序的解聚蛋白样金属蛋白酶(a disintegrin-like and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin motifs,ADAMTS)超家族是一类整合于细胞外基质或游离于血浆中的基质金属蛋白酶亚家族,包括19种不同的ADAMTS蛋白[1]和至少7种ADAMTS-like(ADAMTSL)蛋白(ADAMTSL1-6和papilin)[2-3]。

ADAMTSL5是具有独特结构域的分泌型蛋白质,其包含N-末端TSR,富含半胱氨酸的模块,间隔基模块和C末端NTR模块,其通过富含脯氨酸的片段连接到间隔区(见图1)。

参考文献的著录原则和方法

• 348 •国际生物医学T.程杂志2020年10月第43卷第5期丨m j Bimned Eng,Oc丨。

ber 2020. Vol.43.No.511(8): 1103-1108. DOI:10.1016/j.intimp.2011.03.006.1111Wat K, Ng CF, Koon CM. et al. The protective effect of Herba Cis-tanc hes on statin-induced myotoxicity in vitro[J|. J Ethnopharmacol, 2016, 190: 68-73. DOI: 10.1016/j.jep.2016.06.020.[12] Li X, He X, Liu B, et al. Maturation of murine bone marrow-deriveddendritic cells induced by Radix Glvcyrrhizae polysaccharide [J].Molecules, 2012,17(6): 6557-6568.1)01:10.3390/molecules 17066557.[13] Turnbull E, MacPherson G. Immunobiology of dendritic cells in therat[J|. Immunol Rev, 2001. 184: 58-68. DOI: 10.1034/j. 1600-065x.2001.1840106.x.114| Yu Y, Shen M, Song Q, et al. Biological activities and pharmareutical applications of polysaccharide from natural resources: a review [J]. Carbohydr Polvm, 2018, 183: 91-101. 1)01:10.1016/j.carbp〇1.2017.12.009.[15] Kim HS, Shin BR, Lee HK. et al. Dendritic cell activation bypolysaccharide isolated from Angelica dahurica [J]. Food Chem Toxicol, 2013, 55: 241-247. DOI: 10.1016/j.fct.2012.12.007.116] Banchereau J. Steinman RM. Dendritic cells and the control of immunity[J]. Nature, 1998, 392(6673): 245-252. DOI: 10.1038/ 32588.丨17]阿则古丽•哈木提,阿地拉•艾皮热,马纪,等.维吾尔药免疫调节 作用研究进展Ml•中华中医药杂志,2017, 32(6): 2605-2608.Hamuli A, Aipire A. Ma J,et al. Progress of research on immunoregulatory effects of Uyghur medicint'IJ]. Chin J Tradit Chin Med Pharm, 2017. 32(6): 2605-2608.118| Zhang A, Yang Y, Wang Y, et al. Adjuvant-active aqueous extracts from Artemisia mpestris L. improve immune responses throughTLH4 signaling pathway[J]. Vaccine, 2017, 35(7): 1037-1045. DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.01.002.丨丨9]李知敏,王伯初.周菁,等.植物多糖提取液的几种脱蛋白方法的 比较分析丨儿重庆大学学报,2004, 27(8): 57-59. DOI: 10.3969/j.issn. 1000-582X.2004.08.014.Li ZM, Wang HC, Zhou J. et al. Comparison of three methods ofremoving protein from polysaccharide extract in the plant [J]. JChongqing Univ, 2004. 27(8): 57-59. DOI: 10.3969/j.issn. 1000-582X.2004.08.014.丨20]皮小芳,李玉萍,吴光杰,等.贮存时间及温度对马齿苋多糖体外 抗氧化活性的影响丨儿时珍国医国药,2012, 23(1):丨64-165. D01:10.3969/j.issn. 1008-0805.2012.01.073.Fi XF, Li 'i P. Wu GJ, et al. Effects of storage time and temperatureon antioxidant activity of portulaca oleracea polysaccharides invitro[J]. Lishizhen Med Mater Med Res, 2012. 23(1): 164-165. DOI:10.3969/j.issn. 1008-0805.2012.01.073.[21] 孟祥哲,罗莉,管桐.大枣多糖储藏稳定性研究丨儿农业与技术,2015. 35(1): 44-46. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.l671-962X.2015.01.020.Meng XZ, Luo L, Guan T. Study on storage stability of jujubepolvsaccharicles[JJ. Agr Tec, 2015. 35(1): 44-46. DOI: 10.3969/j.issn. 1671 -962X.2015.01.020.[22] Huang D. Nie S, Jiang L. et al. A novel polysaccharide from theseeds of Plantago asiatica L. induces dendritic cells maturationthrough toll-like receptor 4[J]. Int Immunopharmacol, 2014, 18(2):236-243. DOI:10.1016/j.intimp.2013.11.024.(收稿日期:2020-04-28)•读者•作者•编者•参考文献的著录原则和方法1文章的文后应附有参考文献,以反映论文的科学依据,表示作者尊重他人研究成果的严肃态度并向读者 提供有关信息的出处,不应随意从略。

铁皮石斛 基因组

铁皮石基因组1. 引言铁皮石斛(Dendrobium officinale)是一种珍贵的药用植物,属于兰科(Orchidaceae)石斛属(Dendrobium)。

在中国传统医学中,铁皮石斛被认为具有滋阴清热、益胃生津、明目强腰等功效,常用于治疗热病伤津、口渴舌燥、病后虚热等症状。

近年来,随着基因组学研究的深入,铁皮石斛的基因组结构和功能成为研究热点。

本综述将围绕铁皮石斛基因组的杂合度和结构特点、进化分析以及与药用价值相关的基因家族研究进行综述。

2. 铁皮石斛基因组的杂合度和结构特点铁皮石斛的基因组表现出较高的杂合度,这是由于其在长期进化过程中经历了多倍性和重组事件。

这些杂合性使得基因组存在多个序列类型,从而增加了基因组的复杂性和遗传多样性。

目前已经完成的铁皮石斛基因组测序揭示了其结构特点,包括染色体数目、基因数目和重复序列等。

然而,由于测序方法和数据解析的差异,不同研究中得到的基因组大小略有不同。

据报道,铁皮石斛的基因组大小在1.4-1.9Gb之间。

基因组中含有大量的重复序列,其中转座子是主要的重复元件,这可能与铁皮石斛的杂合性和进化历程有关。

3. 铁皮石斛基因组的进化分析铁皮石斛的基因组进化涉及多个层面,包括染色体数目和结构的变异、基因家族的扩张和收缩以及新基因的产生等。

研究发现,铁皮石斛基因组经历了复杂的进化过程,其中包括全基因组加倍和染色体重排等事件。

这些事件导致了基因组的杂合化和遗传多样性的增加,为铁皮石斛的适应和演化提供了遗传基础。

在铁皮石斛基因组的进化过程中,一些与次生代谢相关的基因家族表现出明显的扩张趋势,如黄酮类化合物生物合成相关的基因家族。

这些扩张的基因家族在铁皮石斛的药用价值形成中可能发挥了重要作用。

4. 与药用价值相关的基因家族研究铁皮石斛的药用价值与其次生代谢产物的种类和含量密切相关。

近年来,随着基因组学和代谢组学研究的深入,越来越多的与药用价值相关的基因和基因家族被发现。

Common problems

Dendritic cell phenotype

phenotype is the noun and cells is the adjective But cells becomes singular as the adjective

Dendritic cell population

Our results implicate glucocorticoids as a cause for…

Imply: to say or express indirectly

The surgeon implied that the disease was fatal.

Elucidate: to make clear

7

Commonly Used Terms

Demonstrate vs Show

Demonstrate: to prove or make evident by reasoning, to describe by experiment

Show: to make visible, to present Demonstrate is stronger for science writing

Abstract: usually past tense, except introductory statement may be present tense

Introduction: usually present tense Methods: past tense Results: past tense Discussion: present tense

The professor teaching this class… The experiment that I just described…

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

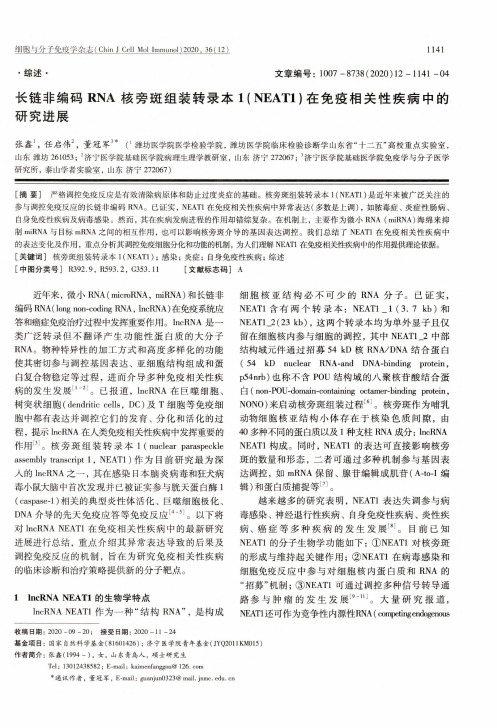

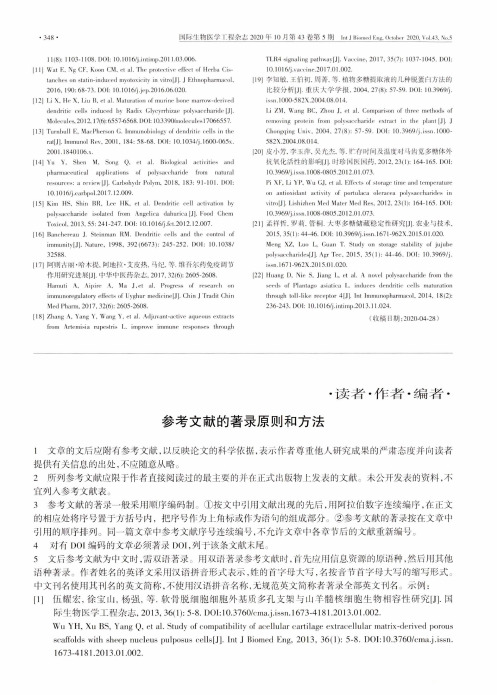

NEWS & VIEWSNATURE|Vol 462|10 December 2009Ahrens, T. J. Science 236, 181–182 (1987). 2. Catalli, K., Shim, S.-H. & Prakapenka, V. Nature 462, 782–785 (2009). 3. Murakami, M., Hirose, K., Kawamura, K., Sata, N. & Ohishi, Y. Science 304, 855–858 (2004). 4. Tsuchiya, T., Tsuchiya, J., Umemoto, K. & Wentzcovitch, R. M. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 224, 241–248 (2004). 5. Hernlund, J. W., Thomas, C. & Tackley, P. J. Nature 434, 882–886 (2005).6. Fei, Y. et al. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104, 9182–9186 (2007). 7. Lay, T. Geophys. Res. Lett. doi:10.1029/2007gl032465 (2008). 8. Merkel, S. et al. Science 316, 1729–1732 (2007). 9. Wookey, J. & Kendall, J. M. in Post-Perovskite: The Last Mantle Phase Transition (eds Hirose, K., Brodholt, J., Lay, T. & Yuen, D.) 171–189 (Am. Geophys. Union, 2007). 10. Mao, W. L. et al. Science 312, 564–565 (2006).IMMUNOLOGYDendritic-cell genealogySophie Laffont and Fiona Powrie The differing origins of gut dendritic cells — white blood cells that modulate immune responses — may explain how the intestinal immune system manages to destroy harmful pathogens while tolerating beneficial bacteria.The immune system must protect the body from invading pathogens without mounting damaging responses to its own tissues. Dendritic cells, a rare population of white blood cells, have a crucial role in determining the nature of immune reactions and in fine-tuning the balance between tolerance (where theBacteriaimmune system ignores or tolerates an antigen) and the induction of inflammation to destroy pathogenic organisms. A long-standing question has been how dendritic cells drive these distinct immune outcomes. Two groups, Varol et al.1 and Bogunovic et al.2, report in Immunity that dendritic cells with distinctBacteria Epithelial cellIntestinal lumenMucosa CD103– CX3CR1+ DC CD103+ CX3CR1– DCTolerogenic responsesProtective immune responses Inflammatory t signals? Flt3 M-CSFPro-inflammatory mediatorsLymph nodesInflammatoryIncreased effector T-cell cell recruitment responsesBlood Pre-DC MonocyteBone marrow MDP Pre-DC MonocyteFigure 1 | Intestinal dendritic cells have different origins and different functions1,2. The two main subsets of intestinal dendritic cells (DCs) originate from distinct blood-cell precursors and depend on different growth factors for their development. Before this divergence, a common precursor, the macrophage and dendritic-cell precursor (MDP), gives rise to pre-dendritic cells (pre-DCs) and monocytes in the bone marrow. Pre-dendritic cells give rise to CD103+ CX3CR1– dendritic cells, and depend on the growth factor Flt3 for their development, whereas monocytes develop into CD103– CX3CR1+ dendritic cells, and depend on another growth factor, M-CSF. CD103+ dendritic cells transport microbial antigens to the lymph nodes, where they may initiate protective immune responses or promote the generation of regulatory T cells that help to maintain tolerance in the intestine. CX3CR1+ dendritic cells do not seem to migrate to lymph nodes, suggesting a more local role in promoting tissue inflammation by stimulating effector T-cell responses and producing pro-inflammatory mediators.732© 2009 Macmillan Publishers Limited. All rights reservedfunctions have different developmental origins, providing a cellular framework for the diverse activities of these cells. Pioneering work by Steinman and colleagues3 in the early 1970s identified a minor population of immune cells that they named dendritic cells on the basis of their stellate shape and membranous processes. These cells were shown to be potent stimulators of another population of white blood cells, T cells. Dendritic cells are strategically placed within mucosal sites in the body, where they can detect infection and take up microbial antigens. On activation, these cells migrate to secondary lymphoid tissue, such as the lymph nodes, where they present the antigen to T cells. This activates the T cells, causing them to differentiate into effector cells that eradicate the pathogen. In the intestine, dendritic cells also promote regulatory T-cell responses that suppress immune reactions against beneficial commensal bacteria and food antigens, thereby preventing immune-related disease. Thus, intestinal dendritic cells are decision makers, ensuring selection of a T-cell response that is appropriate to the nature of the challenge to the immune system. It is now known that dendritic cells are a diverse population of cells, differing in their anatomical location, expression of surface proteins and function. The diversity of the dendritic-cell response may reflect the differential activities of hard-wired developmentally distinct populations or may be due to different maturation states induced by environmental signals. Gaps in our knowledge of dendriticcell developmental pathways have hindered finding answers to these questions. However, recently developed genetic techniques4 to ablate dendritic-cell populations, together with an improved ability to identify specific dendritic-cell precursors, have advanced this area of research. Dendritic cells are closely related to macrophages, which originate from white blood cells called monocytes. They are derived from a common precursor termed the macrophage and dendritic-cell precursor (MDP). Dendritic cells can also be generated5 from monocytes in cell culture using a growth factor called granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), and much of what we know about the biology of dendritic cells has been based on the study of these laboratory-derived cells. However, recent elegant work6,7 has shown that monocytes and dendritic cells diverge in their developmental pathways downstream of the MDP — conventional dendritic cells in lymphoid tissue arise from a precursor cell in the blood (the pre-dendritic cell), and their differentiation depends on the growth factor Flt3. Hence, under normal conditions, blood monocytes do not give rise to dendritic cells in lymphoid tissue, raising questions about the in vivo counterpart of monocyte-derived dendritic cells. Varol et al.1 and Bogunovic et al.2 studied the development of dendritic cells in the intestine.NATURE|Vol 462|10 December 2009NEWS & VIEWSThese tissue dendritic cells can be identified by their expression of a surface protein, CD11c, and they can be divided further into two main subsets that express either of two surface proteins: CD103 or CX3CR1. Both studies1,2 show that CD103+ dendritic cells follow the same developmental pathway as conventional lymphoid dendritic cells: they arise from predendritic cells without a monocyte intermediate and depend on Flt3 for their development. By contrast, both groups1,2 find that monocytes give rise to intestinal CX3CR1+ dendritic cells (Fig. 1). Consistent with their origin from monocytes, these cells must express the macrophage growth-factor receptor known as macrophage-colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF) receptor in order to develop normally. Varol et al.1 also show that the GM-CSF receptor is required for monocyte-derived dendritic-cell development. However, Bogunovic and colleagues2 did not observe this dependence of monocyte-derived dendritic cells on GM-CSF, perhaps reflecting the use of different markers by the two groups1,2 to define the dendritic-cell populations. Why should the origins of intestinal dendritic cells differ from those of lymphoid dendritic cells? The answer may lie in the nature of the intestinal environment, which exists in a state of controlled inflammation, even in the absence of overt infection, because of continuous exposure to commensal bacteria. This controlled inflammatory state may be sufficient to recruit blood monocytes and induce their differentiation into dendritic cells locally. Importantly, pre-dendritic-cell and monocyte-derived dendritic-cell populations in the intestine have distinct functions (Fig. 1). CD103+ dendritic cells migrate from tissues, and can present ingested antigen to immune cells in the local intestinal lymph nodes (mesenteric lymph nodes). Under normal conditions, these CD103+ cells promote intestinal tolerance by inducing the generation of regulatory T cells8–10. But CD103+ dendritic cells can also activate CD8+ killer T cells and, through production of the vitamin A metabolite retinoic acid, induce the expression of receptors on T cells that direct them to the gut11. Consistent with these results, Bogunovic et al.2 show that CD103+ dendritic cells take up salmonella bacteria that have invaded the intestine and then transport the bacteria to mesenteric lymph nodes. Taken together, these data identify pre-dendritic-cell-derived CD103+ dendritic cells as important mediators of immune surveillance in the intestine that can promote both host-protective and tolerogenic T-cell responses. Monocyte-derived CX3CR1+ dendritic cells, on the other hand, have been associated with the induction of inflammatory T cells that promote intestinal inflammation12. CX3CR1+ dendritic cells have been shown to extend processes into the intestinal lumen to sample antigen. But Bogunovic et al.2 provide evidence that thesecells do not usually migrate to the mesenteric lymph nodes. Furthermore, Varol et al.1 demonstrate that CX3CR1+ dendritic cells alone are sufficient to drive intestinal inflammation by producing the pro-inflammatory mediator tumor necrosis factor-α. These observations raise the possibility that intestinal monocytederived dendritic cells do not initiate T-cell responses in secondary lymphoid tissue, but rather promote the inflammatory response at the site of pathogen entry. Further studies are required to assess the behaviour of this subset of dendritic cells during intestinal infection. The identification of the different progenitors of intestinal dendritic cells and the growth factors that control their development are crucial first steps to investigating the functional role of these distinct cell populations in health and disease. This important conceptual advance also potentially opens the door for targeted manipulation of dendritic-cell subsetsto treat immune-mediated diseases.■Sophie Laffont and Fiona Powrie are in the Translational Gastroenterology Unit, Nuffield Department of Clinical Medicine, John Radcliffe Hospital, University of Oxford, Oxford OX3 9DU, and at the Sir William Dunn School of Pathology, Oxford, UK. e-mail: fiona.powrie@1. Varol, C. et al. Immunity 31, 502–512 (2009). 2. Bogunovic, M. et al. Immunity 31, 513–525 (2009). 3. Steinman, R. M. & Cohn, Z. A. J. Exp. Med. 137, 1142–1162 (1973). 4. Jung, S. et al. Immunity 17, 211–220 (2002). 5. Lutz, M. B. et al. J. Immunol. Methods 223, 77–92 (1999). 6. Waskow, C. et al. Nature Immunol. 9, 676–683 (2008). 7. Liu, K. et al. Science 324, 392–397 (2009). 8. Coombes, J. L. et al. J. Exp. Med. 204, 1757–1764 (2007). 9. Sun, C. M. et al. J. Exp. Med. 204, 1775–1785 (2007). 10. Jaensson, E. et al. J. Exp. Med. 205, 2139–2149 (2008). 11. Johansson-Lindbom, B. et al. J. Exp. Med. 202, 1063–1073 (2005). 12. Atarashi, K. et al. Nature 455, 808–812 (2008).STRUCTURAL BIOLOGYMolecular coin slots for ureaMark A. Knepper and Joseph A. Mindell Membrane-bound protein channels that allow only urea to pass through are vital to the kidney’s ability to conserve water. Crystal structures show that the channels select urea molecules by passing them through thin slots.Coin-operated vending machines must reliably accept only valid coins of the correct denomination. Modern machines recognize coins on the basis of their size, shape and even their chemical composition (determined by measuring the coins’ electromagnetic properties). On page 757 of this issue, Levin et al.1 describe the crystal structure of a bacterial urea-conducting channel that acts like a molecular version of a coin-operated machine — it selectively allows planar urea molecules to pass through on the basis of their size, shape and electrical-charge distribution. The authors’ results thereby provide insight into the function of a class of channel that is vital to the function of the human kidney. Urea is a small, nitrogen-containing organic molecule. Although uncharged, it is highly polar and adept at hydrogen bonding; indeed, urea’s ability to form hydrogen bonds with similarly polar water molecules accounts for its astonishingly high solubility in water (more than 8 M). Urea has a special place in the history of science, because it was the first organic molecule to be synthesized by non-biological means from inorganic starting materials2. It is also a key molecule in human physiology: in the liver, excess nitrogen from the normal breakdown of proteins is incorporated into urea, which is subsequently released into the bloodstream, ultimately to be excreted by the kidneys. Because of its high solubility and low© 2009 Macmillan Publishers Limited. All rights reservedtoxicity, large amounts of urea can be excreted in small amounts of water, allowing the kidney to conserve water even when urea excretion is high. But urea excretion presents a challenge for the kidney by virtue of the osmotic forces that the compound generates. The basic structural and functional unit of the kidney is the nephron. Each nephron filters water and small molecules (including urea) from the blood, creating a flow of fluid that passes through a long, narrow renal tubule. These tubules modify the filtered fluid using myriad transport processes, and what is left becomes urine. The final part of the renal tubule is called the collecting duct. Left uncontrolled, the osmotic force of the highly concentrated urea in collecting ducts would suck water from the kidney interstitium (the space between renal tubules), thus undesirably increasing water excretion, a process called osmotic diuresis (Fig. 1a, overleaf). To avoid this, the kidney must balance urea concentrations inside and outside the urinary space by allowing urea to move rapidly across the membranes of the epithelial cells that line the collecting duct (Fig. 1b). The polarity of urea molecules prevents them from readily penetrating nonpolar lipid membranes. Kidney cells therefore use specialized channel proteins to move the molecule rapidly into and through cells. These channels — called UT-A1 and UT-A3 — allow urea733。