《新英格兰杂志》综述全文(中文版):大量失血的预防与治疗

9篇新英格兰英文摘要(考试要考)

1.绝经后骨质疏松症妇女中Strontium Ranelate对椎体骨折的影响The Effects of Strontium Ranelate on the Risk of Vertebral Fracture in Women with Postmenopausal Osteoporosis背景骨质疏松性结构破坏和骨质脆弱是骨质形成减少而骨质吸收增加的结果。

在一项2期临床试验中,strontium ranelate,一种通过增加骨质形成和减少骨质吸收来解除骨质重塑的口服活性药物,已经显示可降低椎体骨折危险而增加骨矿密度。

方法为了在一项3期临床试验中评估strontium ranelate对预防椎体骨折的疗效,我们将1649例患有骨质疏松症(低骨矿密度)并至少有一个椎体骨折的绝经后妇女随机分成两组,使她们分别接受每天2g口服strontium ranelate 或安慰剂治疗共3年。

我们在研究前和研究期间给两组病人都补充钙质和维生素D。

每年1次进行椎体X线检查,每6个月1次进行骨矿密度测定。

结果 Strontium ranelate组比安慰剂组较少病人发生新的椎体骨折,骨折发生危险下降在治疗的第1年中为49%,在3年研究期间为41%(相对危险为0.59,95%可信区间为0.48~0.73)。

Strontium ranelate使36个月时的腰椎骨矿密度增加14.4%,股骨颈骨矿密度增加8.3%(两项比较均P<0.001)。

两组之间的严重不良事件发生率没有显著差异。

结论采用strontium ranelate治疗绝经后骨质疏松症可使椎体骨折危险早期出现持久下降。

(N Engl J Med 2004;350:459-68.January 29,2004)王华译The Effects of Strontium Ranelate on the Risk of Vertebral Fracture in Women withPostmenopausal OsteoporosisABSTRACTBackground Osteoporotic structural damage and bone fragility result from reduced bone formation and increased bone resorption.In a phase 2 clinical trial, strontium ranelate, an orally active drug that dissociates bone remodeling by increasing bone formation and decreasing bone resorption, has been shown to reduce the risk of vertebral fractures and to increase bone mineral density.Methods To evaluate the efficacy of strontium ranelate in preventing vertebral fractures in a phase 3 trial, we randomly assigned1649 postmenopausal women with osteoporosis (low bone mineral density) and at least one vertebral fracture to receive 2 g of oral strontium ranelate per day or placebo for three years.We gave calcium and vitamin D supplements to both groups before and during the study. Vertebral radiographs were obtained annually,and measurements of bone mineral density were performed every six months.Results New vertebral fractures occurred in fewer patients in the strontium ranelate group than in the placebo group, with a risk reduction of 49 percent in the first year of treatment and 41 percent during the three-year study period (relative risk, 0.59; 95 percent confidence interval, 0.48 to 0.73). Strontium ranelate increased bone mineral density at month 36 by 14.4percent at the lumbar spine and 8.3 percent at the femoral neck(P<0.001 for both comparisons). There were no significant differences between the groups in the incidence of serious adverse events.Conclusions Treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis with strontium ranelate leads to early and sustained reductions in the risk of vertebral fractures.2.渗出性缩窄性心包炎Effusive-constrictive PericarditisJaume Sagristà-Sauleda,M.D.,等西班牙巴塞罗那Valld'Hebron大学总医院心脏科,等背景渗出性缩窄性心包炎是一种罕见心包综合征,其特征为伴有由紧张性心包渗出引起的心脏填塞和由脏层心包引起的缩窄。

大量输血指导方案 ppt课件

低体温增加了器官衰竭和凝血障碍的风险性,因此患者复 苏的同时注意患者保温及液体血液加温后输入.

血液成分治疗

创伤患者接受大量输血,早期高比例的FFP、血小板输注已经 显示可以提高患者的生存率,且降低RBC的输注量。

激进的成分输血比例甚至达到RBCs:FFP :platelets为1:1:1,

并且在患者大量失血时尽早给予,无需等待实验室检查和输入 超过人体一个血容量时再输注血浆和血小板。

悬浮红细胞(pRBC)

输注时机: 红细胞输注多在失血30%时进行,失血量超过40%要立即输血, 否则生命受到威胁。

Hb>100g/L时很少输入红细胞,但当<70g/L时几乎常常用,Hb

大量输血指导方案 (推荐稿)

目 录

研究过程 大量输血指导方案 部分调研结果 体外延伸研究

目前我国大量输血的现状

目前我国大量输血无具体的实施方案; 没有统一确认的输血过程检测指标进行指导成分输血; 许多医院输血过程中、输血后不做监测,数据不完整; 凭医生个人经验进行; 临床医生在大失血治疗中,只注重输血而忽视了大量输血可导 致并发症; 临床上出现边输血边出血现象。

于或等于0.3单位/kg体重。

大量输血是指在24小时内输血量大于或等于患者 血容量,正常成人血容量约占体重的7%(儿童约 占体重的8-9%);

大量输血治疗目标

通过恢复血容量和纠正贫血,维持组织灌注和氧供; 通过治疗外伤或产科原发病、阻止出血;

合理应用血液成分纠正凝血障碍。

实验室检查

血液成分治疗

大量输血提供的血液制品为:红细胞悬液(RBCs)、新鲜冰 冻血浆(FFP)、血小板悬液和凝血因子悬液(纤维蛋白原制 剂、冷沉淀、rFⅦ)和辅助药物。

临床输血基本知识(资料汇编)

临床输血基本知识输血是治疗许多疾病的必要手段,但它始终存在一定的风险,甚至可能对患者造成危害。

虽然随着采供血系统管理水平和检验水平的提高,输血传播性疾病和输血不良反应的发生率相对降低了,但是,临床输血的风险仍然不容忽视。

世界卫生组织的资料表明,全世界艾滋病病毒感染者中5%~10%是由于输注了染有艾滋病病毒的血液和血液制品引起的。

而最严重的则是输血相关的急性肺损伤,其临床症状与成人急性呼吸窘迫综合征相似。

其他伴随输血的严重并发症如急性溶血性输血反应、细菌污染、过敏反应、以及其他非特异事件的发生等,都会显著增加患者的死亡危险。

输血相关的急性肺损伤可能是女性献血者在妊娠时被胎儿抗原致敏,血浆中出现白细胞抗体,输入患者体内后,抗原一抗体相互作用导致肺泡、肺间质水肿,出现换气功能障碍和低氧血症。

男性献血者体内不会产生这种抗体,除非曾经输过血,因此似乎输注男性献血者的血浆可减少急性肺损伤的发生风险。

但最根本的还是要合理、科学输注血浆。

因此,合理用血与输血安全已经成为医疗卫生工作中倍受关注的重要问题。

世界卫生组织对“合理用血”给出的定义是:“输注安全的血液制品,仅用以治疗能导致患者死亡或引起患者处于严重情况而又不能用其他方法有效预防和治疗的疾病”。

为了达到科学、合理的用血,需要加强对临床医生的输血医学教育,使临床医师真正理解科学用血的涵义,特别是输血指征的掌握。

为此我国卫生部以及欧美等许多国家和学术组织都制定了有关成分输血的指南。

临床输血工作中,主要任务涵盖三个方面:①安全用血。

如何更好地把握输血指征,减少不良反应和血液传播性疾病;②科学用血。

如何提高输血治疗效果,以提高携氧能力或凝血功能两大目的,做到成分输血;③节约用血。

如何尽可能节约血液资源,减少不必要输血。

即回答要不要输血?什么时候输血?输多少血?输什么成分血等问题。

临床输血技术规范(一)成分输血指南2000年6月1日卫生部发布《临床输血技术规范》,制定了有关成分输血的指南。

《新英格兰医学杂志》综述:轻断食有益健康,缓解多种疾病

《新英格兰医学杂志》综述:轻断食有益健康,缓解多种疾病早在间歇性断食(intermittent fasting;又称轻断食、间歇性禁食)时髦之前,《新英格兰医学杂志》(NEJM)1997年发表的一篇论文就指出,减少动物一生的食物供应(限制热量摄入)可对其衰老和寿命产生显著影响。

自那时起,研究人员已经对受控的间歇性断食方案开展了数百项动物研究和数十项临床研究。

这些研究表明,间歇性断食对健康产生的许多益处不仅因为对机体有害的自由基生成减少或体重减轻,更重要的是间歇性断食可通过改善葡萄糖调节、提高抗应激能力和抑制炎症等方式引发位于器官之间和器官内部,在进化上保守的适应性细胞反应。

断食期间,细胞可激活发挥以下功能的通路:增强对氧化和代谢应激的内在防御,以及清除或修复受损分子(图1)。

进食期间,细胞参与组织生长和可塑性。

然而,大多数人一日三餐外加零食,因此不会发生间歇性断食。

图1. 细胞对进食和断食周期及代谢引起的热量摄入限制产生的反应总体而言,机体对间歇性断食产生的反应是最大限度减少合成代谢过程(合成、生长和生殖)、支持维护和修复系统、增强抗应激能力、再利用受损分子、刺激线粒体生物发生及促进细胞存活,所有这些都有助于改善健康和增强疾病抵抗力。

NEJM于12月26日发表综述,通过动物和人类临床研究的结果,阐述了间歇性断食如何影响健康状况,以及如何减缓或逆转衰老和疾病进程(Effects of intermittent fasting on health, aging, and disease. de Cabo R, Mattson MP. N Engl J Med 2019;381:2541-2551)。

我们在此简介这篇综述(文中图片均来自该综述)。

阅读综述全文,请访问NEJM医学前沿官网()、APP或点击微信小程序图片。

NEJM医学前沿间歇性断食对健康、衰老和疾病的影响小程序间歇性断食和抗应激能力大部分器官系统对于间歇性断食产生的反应使机体能够耐受或克服挑战,然后恢复稳态。

新英格兰医学杂志

新英格兰医学杂志新英格兰医学杂志(New England Journal of Medicine,NEJM)是一本有着悠久历史的医学期刊,由Massachusetts Medical Society出版,创刊于1812年。

作为世界上最负盛名的医学期刊之一,NEJM在全球医学界具有极高的影响力和声誉。

历史背景NEJM创刊于19世纪初,当时的美国正处于医学领域迅速发展的时期。

早期的NEJM主要围绕医学研究和医学实践展开,为医学界提供了一个广阔的交流平台。

随着时间的推移,NEJM逐渐发展成为医学界权威期刊之一,其严谨的审稿标准和高水准的学术质量备受认可。

特色与贡献NEJM以其丰富的学术资源和高品质的文章内容而闻名于世。

每期NEJM都包含了一系列具有广泛影响力的医学研究、临床实践指南、病例分析等。

这些文章涵盖了各个医学领域,不仅为医生、科研人员提供了最新的医学知识和研究成果,也为临床实践提供了重要的参考依据。

NEJM的编辑团队由众多医学界的权威专家组成,他们严格把关每一篇发表的文章,确保其学术水准和准确性。

作为医学领域的风向标,NEJM的发表文章往往会影响全球医学界的发展方向和趋势,成为众多医学专业人士不可或缺的参考资源。

NEJM对于临床实践的影响NEJM所发表的临床研究和实践指南对于提升医学实践的质量和水平起到了积极的作用。

众多临床医生和医疗机构都将NEJM视为获取最新医学信息和发展趋势的主要渠道,从而及时将最新的科学研究成果运用到临床实践中,为患者提供更优质、更有效的医疗服务。

NEJM发表的临床实践指南对于医疗标准的制定和临床决策提供了重要参考。

医生们可以通过NEJM了解到最前沿的医学技术和治疗方法,从而为患者的治疗提供更科学、更精准的方案。

同时,NEJM对于一些疾病的诊断、治疗和预防也提供了宝贵的经验和指导,帮助医生们更好地管理各种疾病。

结语作为医学领域的一面旗帜,新英格兰医学杂志在过去200多年里一直致力于促进医学研究和实践的发展,为医学界提供宝贵的学术资源。

严重创伤失血性休克的急诊护理与并发症预防

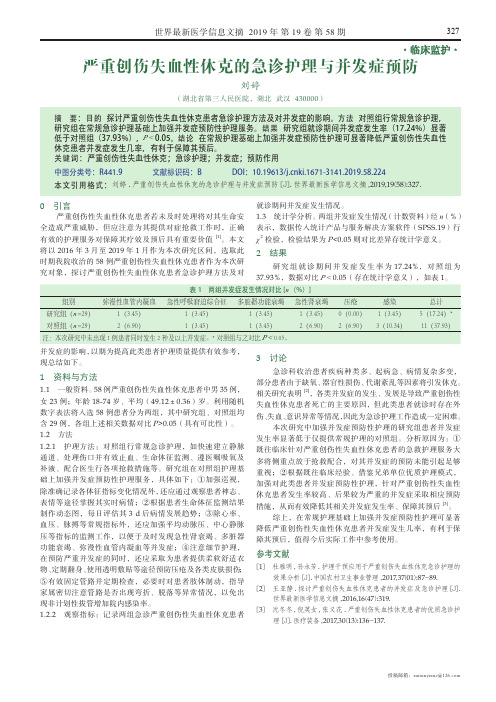

世界最新医学信息文摘 2019年 第19卷 第58期327投稿邮箱:zuixinyixue@·临床监护·严重创伤失血性休克的急诊护理与并发症预防刘婷(湖北省第三人民医院,湖北 武汉 430000)0 引言严重创伤性失血性休克患者若未及时处理将对其生命安全造成严重威胁,但应注意为其提供对症抢救工作时,正确有效的护理服务对保障其疗效及预后具有重要价值 [1]。

本文将以2016年3月至2019年1月作为本次研究区间,选取此时期我院收治的58例严重创伤性失血性休克患者作为本次研究对象,探讨严重创伤性失血性休克患者急诊护理方法及对并发症的影响,以期为提高此类患者护理质量提供有效参考,现总结如下。

1 资料与方法1.1 一般资料。

58例严重创伤性失血性休克患者中男35例,女23例;年龄18-74岁、平均(49.12±0.36)岁。

利用随机数字表法将入选58例患者分为两组,其中研究组、对照组均含29例,各组上述相关数据对比P>0.05(具有可比性)。

1.2 方法1.2.1 护理方法:对照组行常规急诊护理,如快速建立静脉通道、处理伤口并有效止血、生命体征监测、遵医嘱吸氧及补液、配合医生行各项抢救措施等。

研究组在对照组护理基础上加强并发症预防性护理服务,具体如下:①加强巡视,除准确记录各体征指标变化情况外,还应通过观察患者神志、表情等途径掌握其实时病情;②根据患者生命体征监测结果制作动态图,每日评估其3 d 后病情发展趋势;③除心率、血压、脉搏等常规指标外,还应加强平均动脉压、中心静脉压等指标的监测工作,以便于及时发现急性肾衰竭、多脏器功能衰竭、弥漫性血管内凝血等并发症;④注意细节护理,在预防严重并发症的同时,还应采取为患者提供柔软舒适衣物、定期翻身、使用透明敷贴等途径预防压疮及各类皮肤损伤;⑤有效固定管路并定期检查,必要时对患者肢体制动,指导家属密切注意管路是否出现弯折、脱落等异常情况,以免出现非计划性拔管增加院内感染率。

202X年损伤控制性复苏

DCS理念更加符合多发伤患者的病理生理,既把创 伤对患者的损害降到最低限度(xiàndù),又最大限度 (xiàndù)地保存机体生理功能,是兼顾整体和局部逻辑 思维的充分体现

适用于一下情况:

第二十八页,共六十八页。

(1) 多发伤,损伤(sǔnshāng)严重度评分(ISS)>35; (2) 血流动力学极不稳定;

麻醉学杂志,2000年,11期

中心思想(zhōnɡ xīn sī xiǎnɡ)

根据(gēnjù)具体情况按需求补,适度补液,减少附加 损害

充分发挥病人的机体代偿能力

向有利于病情恢复的方向倾斜:血压—出血, 容量—心肺功能

第四页,共六十八页。

起源:损伤 控制性手术 (sǔnshāng)

第五页,共六十八页。

心肺复苏

复苏后综合征

如何让病人(bìngrén)恢复更顺利 小容量液体复苏 限制性液体复苏 损伤控制性液体复苏

第二页,共六十八页。

术中大失血的抢救(qiǎngjiù):超大剂量

例 性 年 体 手术名称 总失

序 别龄 重

血量

(岁) (kg)

(ml)

输血 (ml)

晶体 血浆 量(ml) 量

(héxīn)

➢ 把存活率放在中心地位

➢ 放弃追求手术成功率的传统(chuántǒng)手术治疗模 式

不同于常规手术 也不同于一般的急诊(jízhěn)手术 欧美和日本等国已作为严重创伤救治的原则

第七页,共六十八页。

DCS 的起源

起源可追溯到20世纪前期(qiánqī),二次世界大战至越南战争期间

由于受战争环境,一时间可能产生大批的伤员,加

上条件的限制,分级救治和Ⅱ期手术的概念在战

伤救治中得到充分发展,并成为(chéngwéi)创伤救 治的标准程序

外科患者贫血管理的国际共识

外科患者贫血管理的国际共识多达1/3拟行择期手术的患者在术前即存在贫血。

即便轻微的术前贫血,也与红细胞输注风险增加、术后病残及死亡风险增加相关。

众所周知,术前贫血的及时识别和恰当处置,有助于改善患者预后。

临床也理应优先处理贫血,将其作为一种疾病,而非将其作为是否输注红细胞的指征。

术前贫血原因众多,2/3为缺铁性贫血(IDA)。

此外,1/3非贫血择期手术患者也存在铁缺乏。

近年来,针对外科患者术前贫血的纠正,已有相对较多的临床研究,铁剂治疗是否有效,尚有争论。

为此,患者血液管理促进学会(SABM)组建专家组,综合现有证据,对术前贫血的发生率、病因、诊断及处置等予以全面回顾,根据RANDDeIPhi方法制定临床推荐条目,以期为临床决策提供参考。

该文刊发于2023年4月AnnaISofSUrgery杂志,麻海新知对其重点内容予以编译。

方法14位在患者血液管理领域的尤其是贫血管理方面具有专长的国际专家,被挑选参加外科患者贫血管理国际共识会议(ICCAMS)o另有8位人员审阅推荐内容并参与完成。

专家组于2023年1月11日在PUbMed进行文献检索,纳入近10年内有关患者术前贫血管理的临床研究、系统评价及相关指南等o专家组于2023年3召开在线会议,基于改良RANDDeIPhi法制定共识。

推荐条目同意或不同意率>75%者,即撰写声明并解读。

共识声明的具体内容1.贫血在外科患者中常见,其发生率因手术类型而不同。

在18至49岁人群中,女性的贫血发生率显著高于男性。

在N70岁人群中,贫血不存在性别差异,发生率也最高。

一项纳入24项研究共949455例外科患者的Meta分析提示,术前贫血的发生率为39.设。

另一纳入18项研究逾65万例外科患者的研究提示,术前贫血的平均发生率约为35%。

术前贫血因潜在疾病及拟行手术类型而存在差异(图1)O其中,妇科及血管外科手术患者术前贫血发生率最高,而骨科及泌尿外科手术患者术前贫血发生率最低。

大出血国际标准_概述及解释说明

大出血国际标准概述及解释说明1. 引言1.1 概述在医学领域,大出血是一种严重的情况,指的是人体失去大量血液导致的生命危险。

为了提高大出血患者的救治水平和统一国际间的护理标准,大出血国际标准应运而生。

本文旨在对大出血国际标准进行综述和解释说明。

1.2 文章结构本文共分为四个部分。

引言部分将简要介绍本文目的、大纲以及研究背景。

第二部分将详细阐述大出血国际标准的定义、背景、内容以及实施方法和适用范围。

第三部分将进一步解释说明关于大出血的概念,探讨国际标准在医学领域中的重要性和意义,并提供实际应用案例分析。

最后一部分将对全文进行总结,归纳主要观点和研究发现,并提出未来研究的建议和展望。

1.3 目的本文的目的主要有以下几点:首先,介绍大出血国际标准及其背景;其次,详细阐述标准的内容以及实施方法和适用范围;然后,解释大出血的概念并探讨国际标准的重要性和意义;最后,通过实际应用案例分析,进一步说明标准在医学领域中的实际应用情况。

通过对该主题进行研究和总结,为未来相关研究提供建议和展望。

2. 大出血国际标准:2.1 定义和背景:大出血国际标准是一套用于统一诊断和治疗大出血的指导原则和规范,旨在提高医疗行业对大出血患者的处理水平和效果。

大出血是指身体内部或外部失去过多的血液,通常伴随着严重的伤害、手术或其他医疗情况。

在过去的几十年中,针对大出血患者的治疗方法存在较大差异,缺乏统一标准。

因此,制定国际标准成为必要之举,以确保全球范围内医疗机构可以根据相同的理念进行救治,并提高患者生存率和康复效果。

2.2 标准内容:大出血国际标准包含以下主要内容:- 诊断标准:明确了判断一个患者是否符合大出血定义的指标,并具体列出了相关检查项目和参考值。

- 分级系统:采用分级系统将不同程度的大出血细分为轻、中、重三个级别,以便医务人员能够迅速评估患者的病情严重程度。

- 急救处理:详细介绍了大出血急救的基本步骤和注意事项,包括止血、输液、抗感染等。

(医学课件)术中失血的评估与输血

术中失血的常见原因

手术操作不当

手术过程中操作粗暴或止血不彻底,导致 血管破裂或出血。

药物使用

使用某些抗凝药物或非甾体抗炎药等,会 增加术中出血的风险。

病变性质

某些病变本身就容易引发出血,如肿瘤、 血管病变等。

其他因素

如患者年龄、性别、基础疾病等也可能影 响术中失血的风险。

02

术中失血的评估

术中失血量的评估

术后处理

术后严密观察患者生命体征,及时处理出 现的并发症,预防失血性休克等严重后果 。

VS

输血指导

根据术中失血情况、患者病情等,合理安 排输血,指导术后康复期间的饮食、运动 等。

05

术中失血与输血的误区与 建议

术中失血的误区

误区一

术中失血量越多,越应该输血 。

误区二

只要术中失血量超过30%,就 应该输血。

估计失血量

术中失血量是评估失血程度的重要指标。医生可以通过观察 手术器械、纱布和生理盐水使用情况,结合患者症状和体征 进行估计。

称重法

称重法是一种准确测量术中失血量的方法。医生可以通过在 手术开始前和结束后分别称量手术单和纱布的重量,计算出 失血量。

术中失血速度的评估

观察症状

医生可以通过观察患者的生命体征、意识状态、尿量等指标来判断失血速度 。如果生命体征不稳定、意识模糊、尿量减少等,说明失血速度较快。

术前准备

根据评估结果,做好备血、备品、手术方案的调整等准备工作。

术中控制失血的措施

减少创伤

采用微创手术、精确的手 术操作等方法,减少术中 创伤,从而减少失血。

合理使用止血带

在需要的情况下使用止血 带,控制术中出血。

精细操作

手术过程中保持轻柔、精 细的操作,避免不必要的 损伤和出血。

用血规范及科学合理用血

二、申请用血

1.履行法定手续

与病人或病人家属 谈话,告之输血目的, 交待输血风险,并要 求其在《输血治疗同 意书》上签字。

2.建立计划用血的机制

•《献血法》第十六条 医疗机构临床用血应当 制定用血计划,遵循合理、科学的原则,不得 浪费和滥用血液。 •医院应规定,除急诊外,各用血科室均应按时 向输血科/血库申报用血计划; •报计划是确保临床有序 用血、急诊用血的必要 措施,有利于输血科/血 库开展工作。

但补充的全血并不全;

2.失血后的代偿机制和体液转移:

﹒血流重新分布; ﹒组织间液迅速向血管内转移(自身输液)。

体液(约占体重的60%) 细胞外间隙 血 管 组织间液 15% 内 5% 细胞内间隙液

细胞内液40%

3.尽快输液扩容而不是输血!

﹒临床抢救实践证实输NS比输血好; ﹒二战时用大量血浆抢救伤员效果差; ﹒50年代发现失血性休克用晶体液扩容能预 防肾衰; ﹒70年代证实失血性休克不但血容量↓↓,组 织间液容量也↓↓; ﹒动物实验证实先输 晶体液好; ﹒临床经验证明扩容 要“先晶后胶”。

﹒保存液是针对红细胞设计的(保存期内的 红细胞输入人体后 24 小时,在受血者循 环血中红细胞存活率 ≥ 70% );

血液各种细胞、成分的保存温度及保存时限 红细胞 4℃± 2℃ 35天 白细胞 室温* 8小时 血小板 22℃±2℃ 5天 FFP -20℃以下 1年 FP -20℃以下 4年 凝血因子 -20℃以下 1年 ( * 室温下保存的白细胞,其粒细胞的炎症趋化 性要比4℃保存的高33%)

· 原因是HLA的抗原抗体反应,补体被激活,使中 性粒细胞在肺血管内聚集滞留,释放蛋白酶、 酸性脂质和氧自由基等,使,导致肺 水肿或呼吸窘迫综合征。 · 处理:立即停止输血,给氧、利尿、静滴肾 上腺皮质激素或应用抗组织胺药治疗。 ·发生过此类反应的病人,今后 若需再输血则应作去白细胞处 理,亦可用洗涤红细胞。

《创伤性失血性休克》

整理课件

急性创伤性凝血病

• 发病率: 1/4~l/3的患者在入院时存在 • 预后:密切相关 • 病死率:比未患凝血病的患者高4~6倍

整理课件

急性创伤性凝血病

一美军医院收治243例接受大量输血患者: •到院时PT国际标准化率(INR)>1.5或血小板降 低者的死亡率为30%; •而INR<1.5者死亡率为5% 。

①根据贫血程度、心肺代偿功能、有无代谢率增高及年龄 因素决定是否输血;(1B)

②合并组织缺氧:混合静脉血氧分压<35mmHg,混合静脉 血氧饱和度<65%,和(或)碱缺失严重、血清乳酸浓度 增高;(1B)

③若无组织缺氧,暂不推荐。(1C)

➢ 复苏后,若HB>100g/L,可不输注。(1B)

整理课件

红细胞

严重创伤输血专家共识

整理课件

血水之战

--解读“严重创伤输血专家共识”

郭雅斐 2014年10月22日

整理课件

引言

• 创伤的发生率增高 • 1-45岁首位死亡原因 • 早期死亡 :失血性休克

整理课件

创伤性失血性休克治疗原则

• 止血 • 保证组织灌注 • 提高携氧能力 • 纠正凝血障碍

整理课件

止血与液体复苏

➢ PLT>100*10^9/L,可不输注。(1C)

整理课件

血小板

➢ 推荐根据TEG参数MA值及时调整血小板输注量。 (1C)

➢ 推荐输注的首剂量为1治疗量单采血小板。(2C) ➢ 如果术中出现不可控制的渗血,或存在低体温,

TEG检测显示MA值降低,提示血小板功能低下时 ,血小板输注量不受上述限制。(1C)

整理课件

抗纤溶药物

➢ 6-氨基己酸的首剂量为100-150mg/kg,随后 1.5ml/kg.min。(2C)

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

《新英格兰杂志》综述全文(中文版):大量失血的预防与治疗Prevention and Treatment of Major Blood Loss大量失血的预防与治疗Pier Mannuccio Mannucci, M.D., and Marcel Levi, M.D., Ph.D.NEJM,Volume 356:2301-2311 May 31, 2007 Number 22第一部分In a medical setting, surgery is the most common cause of major blood loss, defined as a loss of 20% of total blood volume or more. In particular, cardiovascular procedures, liver transplantation and hepatic resections, and major orthopedic procedures including hip and knee replacement and spine surgery, are associated with severe bleeding. Excessive blood loss may also occur for other reasons, such as trauma. Indeed, bleeding contributes to approximately 30% of trauma-related deaths.1 Bleeding in critical locations, such as an intracerebral hemorrhage, may also pose a major clinical challenge.Severe bleeding often requires blood transfusion. Even when the benefits of transfusion outweigh the risks (e.g., mismatched transfusion, allergic reactions, transmission of infections, and acute lung injury),2 strategies to minimize the use of limited resources such as blood products are essential. The most obvious and probably the most effective strategy is to improve surgical and anesthetic techniques. For example, liver transplantation, a procedure that once required transfusion of large amounts of blood products, now has relatively small transfusion requirements in most instances.Ruling out abnormalities of hemostasis in a patient with bleeding is also essential, because such problems can often be corrected by replacing the defective components of the hemostatic system. However, cases of excessive blood loss in which no surgical cause or abnormalities in hemostasis can be identified require pharmacologic strategies, which can be broadly divided into preoperative prophylaxis for operations that confer a high risk of bleeding and interventions for massive, refractory bleeding. The medications that have been most extensively evaluated as hemostatic agents include the antifibrinolytic lysine analogues aminocaproic acid and tranexamic acid; aprotinin, a bovine-derived protease inhibitor; and desmopressin, a synthetic analogue of the antidiuretic hormone that raises the plasma levels of factor VIII and von Willebrand factor.3 In addition, recombinant activated factor VII appears to be efficacious in an array of clinical situations associated with severe hemorrhage.4 The safety of aprotinin, the most widely used of these agents, has been questioned because of concerns about renal and cardiovascular adverse events.5Most trials of hemostatic agents have been designed to assess therapeutic efficacy, but they were not optimally designed to assess potential toxic effects, so definitive safety data are lacking for all hemostatic agents. Many trials of these agents have used perioperative blood loss and othermeasures that are not the most clinically relevant end points, and many published trials were not powered to assess more clinically relevant outcomes such as mortality or the need for reoperation. We review the therapeutic benefits of hemostatic drugs and consider the risk of adverse events. In particular, we consider thrombotic complications, which constitute a major concern when agents that potentiate hemostasis are administered.第二部分Antifibrinolytic AgentsApproximately 5% of patients undergoing cardiac surgery require reexploration because of excessive blood loss; indeed, bleeding during and after cardiac surgery is an established marker of increased morbidity and mortality.6,7,8 Pharmacologic strategies are therefore often used to minimize blood loss during cardiac surgery. Aprotinin (a direct inhibitor of the fibrinolytic enzyme plasmin) is the only drug reported to minimize transfusion requirements in coronary-artery bypass grafting and approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Aminocaproic acid and tranexamic acid are also used, but they have not been approved by the FDA for this indication. The mechanism of action of these agents is illustrated in Figure 1. Table 1 lists the most frequently used dosages of antifibrinolytic agents.Figure 1. Mode of Action of Lysine Analogues (Aminocaproic Acid and Tranexamic Acid).Activation of plasminogen by endogenous plasminogen activators results in plasmin, which causes degradation of fibrin. Binding of plasminogen to fibrin makes this process more efficient and occurs through lysine residues in fibrin that bind to lysine-binding sites on plasminogen (Panel A). In the presence of lysine analogues, these lysine-binding sites are occupied, resulting in an inhibition of fibrin binding to plasminogen and impairment of endogenous fibrinolysis (Panel .Table 1. Mechanism of Action and Intravenous Doses of Antifibrinolytic Agents Used in Cardiac Surgery to Minimize Blood Loss and Transfusion Requirements.Efficacy of Antifibrinolytic AgentsAfter the first study in 1987,9 more than 70 randomized, controlled trials that included from 20 to 796 patients (median, 75) confirmed and established the efficacy of aprotinin for limiting the requirements for transfusion of red cells, platelets, and fresh-frozen plasma in patients undergoing cardiac surgery. We examine in depth four trials chosen for their size and design.In a study of 796 patients who were randomly assigned to receive aprotinin or placebo during primary coronary-artery bypass grafting, aprotinin was associated with reduced blood loss (mean [±SD], 664±1009 ml, vs. 1168±1022 ml in the placebo group). Aprotinin also was associated with a decreased rate of use of any blood product (40%, vs. 58% in the placebo group).10 In a randomized, placebo-controlled trial involving 704 patients, treatment with aprotinin was associated with a decrease in mean perioperative blood loss (832±50 ml, vs. 1286±52 ml in the placebo group) and a reduction in the proportion of patients requiring any transfusion (35% vs.55%).11 Two trials recruited patients who were at increased risk for bleeding because they were undergoing repeat cardiac surgery.12,13 On average, patients who received aprotinin needed between 1.6 and 2 units of blood products, whereas patients who received placebo needed between 10 and 12 units.12,13 Similar findings with aprotinin have been reported in many other placebo-controlled trials, with a reduction in perioperative blood loss ranging from 50 to 1350 ml (median reduction, 400 ml) and a reduction by a factor of 1.5 to 3 in the proportion of patients requiring any transfusion.14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25第三部分Randomized trials of tranexamic acid or aminocaproic acid are much less numerous than trials of aprotinin.26,27,28,29,30,31 In the largest trial of tranexamic acid, 210 patients were randomly assigned to receive tranexamic acid (at a dose of 10 g) or placebo. Administration of tranexamic acid resulted in a 69% reduction in red-cell transfusions, and the proportion of patients requiring any blood product was 12.5% in the tranexamic acid group as compared with 31.1% in the control group.31There have also been meta-analyses and systematic reviews of the efficacy of antifibrinolytic agents.32,33,34,35,36 Table 2 summarizes the results of a Cochrane review. As compared with placebo, the use of aprotinin or tranexamic acid, but not of aminocaproic acid, reduced the need for blood transfusion by 30% and saved approximately 1 unit of blood per operation.36 There was no difference in efficacy between low-dose and high-dose regimens of aprotinin (Table 1), whereas the large variations in dosages of tranexamic acid and aminocaproic acid precluded the evaluation of the relationship between dosage and efficacy. In terms of more clinically relevant events, the relative risk of reoperation for excessive bleeding was significantly reduced among patients who received aprotinin, as compared with those who received placebo, although mortality was not affected. There was a significant reduction in these events with either tranexamic acid or aminocaproic acid.36Table 2. Results of the Cochrane Review of the Effect of Antifibrinolytic Agents on Clinical Events among Patients Undergoing Major Surgical ProceduresThus, the results of controlled trials and reviews indicate that antifibrinolytic drugs are effective hemostatic agents in cardiac surgery. Reductions in both transfusion requirements and reoperation for bleeding appear to be confirmed by the narrow confidence intervals of the odds ratios that are indicators of the relative risks (Table 2). There are not enough efficacy data to draw definitive conclusions regarding the use of antifibrinolytic agents in other situations.Safety of Antifibrinolytic AgentsThere have been criticisms that many trials of the efficacy of aprotinin in cardiac surgery were unnecessarily carried out (and reported) after the transfusion-sparing efficacy was unequivocally established and that such studies should have focused instead on the more cogent and unsettled issue of safety.37,38 Adverse events, particularly thrombotic complications, are expected when a major regulatory system such as the fibrinolytic system is pharmacologically inhibited; this isespecially true in patients undergoing cardiac surgery, because they often have underlying atherothrombotic disease.Table 3, which summarizes the risks of complications when antifibrinolytic agents are administered, shows that none of the adverse events examined was significantly increased.36 However, a few early studies indicated that the use of aprotinin could lead to an increase in cases of postoperative renal dysfunction, possibly through the inhibition of kallikrein and other endogenous vasodilators, with a resultant reduction of renal blood flow.24,39,40Table 3. Results of the Cochrane Review of the Effect of Antifibrinolytic Agents on Adverse Events among Patients Undergoing Major Surgical Procedures.第四部分The risk of serious adverse events associated with aprotinin was recently highlighted by the results of a nonrandomized, observational study involving 4374 patients who underwent elective coronary-artery bypass surgery.5 That study, which compared aprotinin, aminocaproic acid, and tranexamic acid with no treatment, used the propensity-score adjustment method to balance the covariates and thus reduce bias that could arise if sicker patients selectively received one agent over another. The results indicated that, as compared with no treatment, aprotinin (but neither aminocaproic acid nor tranexamic acid) doubled the risk of severe renal failure, increased the risk of myocardial infarction or heart failure by 55%, and was associated with a nearly doubled increase in the risk of stroke or other cerebrovascular events. That study confirmed that the three antifibrinolytic agents reduced blood loss to a similar degree, but adverse events were much more frequent with aprotinin than with the other agents. Much debate followed the publication of the study,41,42,43,44 which was criticized on the grounds that it was observational, was carried out in many different countries and institutions, and was poorly controlled with respect to known determinants of outcome such as the use or nonuse of antithrombotic and inotropic drugs, the duration of cardiopulmonary bypass, and the amounts of blood transfused.However, other recent studies have also reported adverse renal effects of aprotinin. A review of randomized trials conducted from 1991 to 2005 reported that patients who received aprotinin had a 9% rate of renal failure (defined as the need for dialysis or a postoperative increase in the serum creatinine level of at least 2.0 mg per deciliter [176.8 µmol per liter]) and that renal dysfunction (defined as an increase in creatinine of 0.5 to 1.9 mg per deciliter [44.2 to 168.0 µmol per liter]) occurred in 12.9% of patients receiving aprotinin as compared with 8.4% of controls (relative risk, 1.47; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.12 to 1.94; P<0.001).41 An observational survey commissioned by the manufacturer showed similar rates of renal dysfunction and renal failure among 67,000 patients who received aprotinin.45Although Mangano et al.5 and the authors of previous systematic reviews report that aminocaproic acid and tranexamic acid appear to be relatively safe,32,33,34,35,36 the numbers of trials and study participants were much smaller for these drugs than for aprotinin. Thus, confidence with regard to safety issues is not solid, especially with respect to thrombosis. Most important, trials comparing aprotinin with lysine analogues have been too few and toosmall.46,47,48,49 An independently funded, randomized clinical trial with three study groups is being conducted in Canada. The Blood Conservation using Antifibrinolytics: A Randomized Trial in a Cardiac Surgery Population (BART) study, which is still enrolling patients, plans to enroll 2970 patients undergoing high-risk cardiac surgery to determine whether aprotinin is superior to aminocaproic acid or tranexamic acid in reducing the risk of massive postoperative bleeding.50 Secondary end points are mortality from all causes and adverse events such as cardiovascular disease and renal failure.50第五部分On the basis of all the data reported thus far, there is abundant, solid evidence that aprotinin reduces perioperative and early postoperative blood loss and transfusion requirements in patients undergoing cardiac surgery. However, despite the large number of clinical trials involving this agent, its effectiveness in decreasing the need for reoperation has been reported only in reviews,36 and evidence of its effect on mortality is lacking. It is regrettable that the inexpensive lysine analogues have been less thoroughly investigated as of this writing, because it appears likely that these agents are at least as efficacious as aprotinin. The uncertainty about aprotinin's safety remains a substantial concern. Until the results of the Canadian trial are available,50 aprotinin remains the hemostatic agent of choice. However, it should be used only when excessive perioperative and early postoperative blood loss is predicted (e.g., in the case of a complex operation or special clinical circumstances such as the use of antiplatelet agents).Evidence of the efficacy of lysine analogues is not as solid as that for aprotinin, so these agents should be used only as a second choice in high-risk cardiac surgery. There is definitely no role for either aprotinin or other hemostatic agents in noncomplex coronary-artery bypass surgery, even though in many cases an off-pump procedure is used, which reduces blood loss and transfusion requirements.51,52 The FDA has warned that it is important to monitor patients receiving aprotinin for renal, cardiac, and brain toxic effects and that aprotinin should be used only when the clinical benefit of reducing blood loss is essential to medical management and outweighs any risk.53Recombinant Activated Factor VIIRecombinant activated factor VII (rFVIIa) is thought to act locally at the site of tissue injury and vascular-wall disruption by binding to exposed tissue factor, generating small amounts of thrombin that are sufficient to activate platelets4 (Figure 2). The activated platelet surface can then form a template on which rFVIIa directly or indirectly mediates further activation of coagulation, ultimately generating much more thrombin and leading to the conversion of fibrinogen to fibrin.54,55 Clot formation is stabilized by the inhibition of fibrinolysis due to rFVIIa-mediated activation of thrombin-activatable fibrinolysis inhibitor.56Figure 2. Mechanism of Action of Recombinant Factor VIIa.When the vessel wall is disrupted, subendothelial tissue factor becomes exposed to circulating blood and may bind factor VIIa (Panel A). This binding activates factor X, and activated factor X(factor Xa) generates small amounts of thrombin. The thrombin (factor IIa) in turn activates platelets and factors V and VIII. Activated platelets bind circulating factor VIIa (Panel , resulting in further factor Xa generation as well as activation of factor IX. Activated factor IX (factor IXa) (with its cofactor VIIIa) yields additional factor Xa. The complex of factor Xa and its cofactor Va then converts prothrombin (factor II) into thrombin (factor IIa) in amounts that are sufficient to induce the conversion of fibrinogen to fibrin.第六部分Efficacy of rFVIIaInitially, rFVIIa was licensed for the treatment of bleeding in patients with hemophilia who had antibodies inactivating factor VIII or IX.4 More recently, this agent has been used extensively in patients with major hemorrhage from surgery, trauma, or other causes.57 A small, controlled clinical trial showed that rFVIIa could minimize perioperative blood loss and transfusion requirements in patients undergoing transabdominal prostatectomy, an operation that is often associated with major blood loss.58 In that trial, 36 patients were randomly assigned to receive a single preoperative injection of rFVIIa (20 or 40 µg per kilogram of body weight) or placebo. Administration of the active drug resulted in a significant reduction of blood loss (50%) and eliminated the need for transfusion, which was required in approximately 60% of patients who received placebo.58Additional studies have focused on patients undergoing orthotopic liver transplantation. An open-label pilot study involving six patients showed a marked reduction in transfusion requirements among those who received a single dose of rFVIIa (80 µg per kilogram) as compared with matched historical controls.59 However, a subsequent randomized, placebo-controlled trial evaluating two different doses of rFVIIa (60 and 120 µg per kilogram) showed no reduction in transfusion requirements among 182 liver-transplant recipients, although red-cell transfusion was averted in 8.4% of patients who received rFVIIa but in none of the patients in the placebo group.60 Two randomized, controlled trials of rFVIIa (up to 100 µg per kilogram at every second hour of surgery) in patients with cirrhosis or normal liver function who were undergoing major liver resection did not show a significant effect of rFVIIa on either the volume of blood products administered or the percentage of patients requiring transfusion.61,62In addition, rFVIIa was evaluated in a randomized, controlled study involving 20 patients undergoing noncoronary cardiac surgery requiring cardiopulmonary bypass.63 Administration of rFVIIa at a dose of 90 µg per kilogram after discontinuation of bypass significantly reduced the need for blood transfusion (relative risk of any transfusion, 0.26; 95% CI, 0.07 to 0.90). In addition, a propensity score?matched, case?control study involving 51 patients with massive blood loss after cardiac surgery showed a significant decrease in blood loss and requirements for blood products after the administration of rFVIIa (at a dose of 35 to 70 µg per kilogram).64 In this study, however, the incidence of acute renal dysfunction among patients receiving rFVIIa was 2.4 times that in the control group, although there were no significant differences between the two groups with regard to other adverse events.64Several case reports and case series suggest that rFVIIa is also useful in reducing major blood loss in patients with trauma.65 A placebo-controlled trial involving 143 patients with severe blunt trauma showed that three successive doses of rFVIIa (200, 100, and 100 µg per kilogram) significantly reduced red-cell transfusion (mean reduction, 2.6 units) and reduced the proportion of patients in whom massive transfusion, defined as more than 20 units of red cells, was required (14% of treated patients vs. 33% of controls).66 However, a parallel trial involving 134 patients with penetrating trauma showed no significant effects.66第七部分Studies have also evaluated rFVIIa for the treatment of spontaneous intracranial hemorrhage, a condition for which there is a paucity of effective therapeutic options.67 A dose-finding trial involving 400 patients showed that as compared with placebo, rFVIIa was associated with a slower increase in the size of intracerebral hematoma. More important, there was a 35% reduction in mortality and an improved disability score at 90 days in patients who received rFVIIa.67 Unfortunately, these promising early results were not confirmed in a subsequent phase 3, randomized, controlled trial involving 821 patients.68 A preliminary report indicated that there was a significant reduction in the size of the intracerebral hematoma but with no effect on mortality and severe disability on day 90, the primary end point of the study.68 The manufacturer has not sought regulatory approval for rFVIIa for the treatment of intracerebral hemorrhage.This agent has also been studied in patients with bleeding esophageal varices and portal hypertension, a combination that constitutes another major clinical challenge. In a randomized, controlled trial involving 245 patients with cirrhosis and upper gastrointestinal bleeding (66% of whom had bleeding varices) who were being treated with standard endoscopic and pharmacologic interventions, the administration of rFVIIa (eight consecutive doses of 100 µg per kilogram within 30 hours after the initiation of treatment) was not more effective than placebo with respect to the primary composite end point (failure to control bleeding within 24 hours and failure to prevent rebleeding or death within the first 5 days).69 However, in a subgroup of patients with more severe cirrhosis (classified as Child class B or C), rFVIIa was associated with a decrease in the proportion of patients reaching the composite end point (8%, vs. 23% in the control group; P=0.03). Furthermore, none of the patients treated with rFVIIa had rebleeding within 24 hours, whereas rebleeding occurred in 11% of patients in the control group (P=0.01).69Many case reports and case series have examined the use of rFVIIa in patients with excessive or life-threatening blood loss occurring in an array of clinical settings.57 However, no randomized, controlled clinical trials have been completed, which is not surprising, given the difficulty of performing meaningful studies in such heterogeneous situations. Many reports claim that the use of rFVIIa resulted in rapid reduction of blood loss or a decrease in transfusion requirements after other therapeutic measures had failed. Although many of these reports appear to be compelling, it is difficult to assess the usefulness of rFVIIa properly, since publication bias in case reports and series is likely.第八部分Safety of rFVIIaControlled clinical trials have shown that the incidence of thrombotic complications among patients who received rFVIIa was relatively low and similar to that among patients who received placebo.70 However, most studies of rFVIIa involved patients who had impaired coagulation or who were at low risk for thrombosis. In one trial involving patients with conditions such as intracerebral hemorrhage and a much higher risk of thrombosis, 7% of patients receiving rFVIIa had serious thromboembolic events ? mainly myocardial infarction or ischemic stroke ? as compared with 2% of those receiving placebo.67 Midway through this trial, an exclusion criterion changed. Initially, only patients with thrombotic disease within 30 days before enrollment were excluded, but at the midpoint, all patients with any history of thrombotic disease were excluded, which may have obscured safety concerns associated with the use of rFVIIa. A review based on the FDA MedWatch database indicated that thromboembolic events have occurred in both the arterial and venous systems, particularly in patients with diseases other than hemophilia in whom rFVIIa was used on an off-label basis.71 A total of 54% of the thromboembolic events were arterial thrombosis (in most cases, stroke or acute myocardial infarction); venous thromboembolism (in most cases, venous thrombosis or pulmonary embolism) occurred in 56% of patients. In 72% of the 50 reported deaths, thromboembolism was considered the probable cause. It is not clear to what extent the clinical conditions requiring the use of rFVIIa may have contributed to the risk of thrombosis.71 These findings provide evidence of an increased risk of thrombotic complications that may offset the potential benefit of rFVIIa in patients with severe blood loss.The availability of rFVIIa has expanded the treatment options for acute hemorrhage in patients with conditions other than hemophilia. This agent is not a panacea, but it has efficacy in patients with trauma and excessive bleeding that is resistant to other treatments. However, the promising results obtained so far must be substantiated by confirmatory trials, and studies of the cost-effectiveness of this expensive agent are also warranted. The many published cases of dramatic success in patients with various types of acute hemorrhages, albeit convincing and rewarding for the involved clinicians, should be viewed with caution in terms of constituting clinically directive evidence. Attempts are being made to improve the potency and efficacy of rFVIIa further by engineering the molecule through DNA technology, but clinical trials designed to establish increased efficacy and safety remain to be performed.72,73第九部分Other InterventionsDesmopressin was originally developed and licensed for the treatment of inherited defects of hemostasis.74,75,76 This drug, given by slow intravenous infusion at a dose of 0.3 µg per kilogram, acts by releasing ultralarge von Willebrand factor multimers from endothelial cells, leading to an increase in plasma levels of von Willebrand factor and associated factor VIII and anenhancement of primary hemostasis.77,78 The strongest evidence of efficacy is in the prevention and treatment of bleeding in patients with mild hemophilia A and von Willebrand's disease.75,76 In 1986, Salzman et al.79 showed that as compared with placebo, desmopressin reduced blood loss and transfusion requirements by approximately 30% during complex cardiac surgery. Subsequent attempts to reproduce these findings were variable; most did not confirm the marked benefit originally reported.80,81,82 Overall, there have been 18 trials of desmopressin in a total of 1295 patients undergoing cardiac surgery. These trials show a small effect on perioperative blood loss (median reduction, 115 ml). Several reviews suggest that although desmopressin helps to reduce perioperative blood loss, its effect is too small to influence other, more clinically relevant outcomes such as the need for transfusion and reoperation.33,83,84,85 In addition, desmopressin does not reduce blood loss or transfusion requirements during elective partial hepatectomy, another operation often associated with major blood loss.86 A report that desmopressin reduced blood loss associated with posterior spinal surgery for idiopathic scoliosis87 was not confirmed.88,89,90Although desmopressin can shorten the skin-bleeding time in patients with uremia,91 the current widespread use of recombinant erythropoietin has made this abnormality of hemostasis much less frequent than it was previously.92 The beneficial effect of erythropoietin on hemostasis is based on the increase in red-cell mass, which affects the blood?fluid dynamics, leading to a more intense interaction between circulating platelets and the vessel wall.Thus, there is little evidence that desmopressin is efficacious in conditions other than mild hemophilia A and von Willebrand's disease. The use of desmopressin in some patients who have bleeding as a consequence of inherited and acquired defects of platelet function may be considered. This drug has been shown to shorten the skin-bleeding time in patients with cirrhosis of the liver and in those with some types of inherited platelet disorders.93 However, the use of desmopressin for these indications is not supported by sound clinical evidence based on relevant end points.94 The most common adverse effects of desmopressin, facial flushing and transient hyponatremia, are usually mild. There have been reports of arterial thrombotic events, not only in patients with atherothrombosis but also in patients with bleeding disorders and in a blood donor.95,96,97,98,99,100 A systematic review showed that for patients with acute myocardial infarction who underwent cardiac surgery, the frequency of these adverse events among patients who received desmopressin was twice that among patients who received placebo, with no improvement in clinical outcomes.33 However, another review, evaluating 16 trials of desmopressin in cardiac surgery and in other high-risk operations, showed that the rate of thrombosis did not differ significantly between patients who received desmopressin and patients who received placebo (3.4% vs. 2.7%).101第十部分Hemostatic agents for topical use (particularly "fibrin sealants" composed of human fibrinogen, human or bovine thrombin, and in some instances human factor XIII and bovine aprotinin) have been licensed in Europe.102,103 In several poorly controlled studies involving small series of patients, the efficacy of these agents has been reported for indications such as cardiovascular and。