Feedback Control For Robot Formation Maneuvers

Robust control of robot manipulators

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ROBUST AND NONLINEAR CONTROLInt.J.Robust.Nonlinear Control2013;23:104–122Published online9October2011in Wiley Online Library().DOI:10.1002/rnc.1823Robust control of robot manipulators based on uncertainty anddisturbance estimationJaywant P.Kolhe,Md Shaheed,T.S.Chandar and S.E.Talole*,†Department of Aerospace Engineering,Defence Institute of Advanced Technology,Girinagar,Pune411025,IndiaSUMMARYIn this work,uncertainty and disturbance estimation(UDE)based robust trajectory tracking controller for rigid link manipulators was proposed.The UDE was employed to estimate the composite uncertainty that comprises the effects of system nonlinearities,external disturbances,and parametric uncertainties.A feed-back linearization based controller was designed for trajectory tracking,and the same was augmented by the UDE-estimated uncertainties to achieve robustness.The resulting controller however required measure-ment of joint velocities apart from the joint positions.To address the issue,an observer that employed the UDE-estimated uncertainties for robustness was proposed,giving rise to the UDE-based controller–observer structure.Closed-loop stability of the overall system was established.The notable feature of the proposed design was that it neither required accurate plant model nor any information about the uncertainty.Also, the design needed only joint position measurements for its implementation.To demonstrate the effective-ness,simulation results of the proposed approach as applied to the trajectory tracking control of two-link robotic manipulator and comparison of its performance with some of the well-known existing controllers were stly,hardware implementation of the proposed design for trajectory control of Quanser’s single-linkflexible joint module was carried out,and it was shown that the proposed strategy offered a viable approach for designing implementable robust controllers for robots.Copyright©2011John Wiley &Sons,Ltd.Received27November2010;Revised21March2011;Accepted4September2011KEY WORDS:uncertainty and disturbance estimation;feedback linearization;robot manipulator;robust control;robust observer;controller–observer structure1.INTRODUCTIONControl of robotic manipulators is an area of active research,and,owing to its highly coupled nonlinear dynamics,it offers a challenging task for high performance control system design.The task gets further compounded when the system is subjected to various model uncertainties and unmeasurable external disturbances.As the model-based control strategies such as the one based on feedback linearization(FL)approach[1]may not offer satisfactory performance in the presence of uncertainties,various robust control approaches have been presented in the literature for designing tracking controllers for robot manipulators.Designs based on Proportional-derivative(PD)control [2],Proportional-integral-derivative[3],H-infinity[4],Lyapunov-based theory[5],variable struc-ture control[6],optimal control[7],state dependent Riccati equation approach[8],neural networks [9],and fuzzy logic[10]are some representative approaches to mention,and an exhaustive survey of various strategies proposed for the design of robust controllers for robotic manipulators can be found in[11,12].*Correspondence to:S.E.Talole,Department of Aerospace Engineering,Defence Institute of Advanced Technology, Girinagar,Pune411025,India.†E-mail:setalole@ROBUST CONTROL OF ROBOT MANIPULATORS BASED ON UDE105 In many of the robust control formulations presented in the literature,there exists certain issues that need attention.Firstly,in the number of the proposed controllers,knowledge of some charac-teristic of uncertainty is assumed.To cite a few examples,in[13],the uncertainty is assumed to be bounded by higher-order polynomials in system states.In[14],the uncertainty is assumed to be bounded by a known continuous function.Similarly,in[15],afinite-time robust control formula-tion is presented wherein the knowledge of uncertainty bound is needed.Also,as is well known, the formulations based on sliding mode control(SMC)and Lyapunov-based approaches in general require a priori knowledge of bounds of uncertainty.As the uncertainties are generally unknown or poorly known,not having accurate information on the characteristics of the uncertainty results into degraded performance.For example,when the knowledge of bound on uncertainties is not available,the use of highly conservative bound results in excessive control effort,and use of lower bounds may result in degradation of performance or even in instability.Secondly,most of the con-trollers proposed for robotic manipulators need the measurement of joint positions and velocities. Whereas position can be accurately measured by good precision encoders,velocity measurement is often an issue because of measurement noise[16].Apart from this,the cost and weight of an additional sensor can also be a deterrent.One approach to address the issue is to obtain the estimate of velocity from position measurement through approximate differentiation.However,the resulting estimate may not be satisfactory.A better alternative is to obtain the velocity states by designing an appropriate observer[17].However,observers designed based on an assumed system model may suffer from robustness when the model uncertainties show up.Also,as the separation principle is not,in general,valid in nonlinear systems,the closed-loop stability of the controller–observer sys-tem remains an stly,an important consideration in designing controllers in robotic system is that it should be simple from real-time implementation point of view.In this paper,an uncertainty and disturbance estimation(UDE)[18]based robust trajectory track-ing controller is proposed for rigid link manipulators.An FL-based controller is formulated by considering the system nonlinearities,uncertainties,and external disturbances as a composite uncer-tainty.The FL controller is then augmented by the UDE-estimated uncertainty[19]to achieve robustness.As the resulting controller requires joint velocities apart from the joint positions,a robust observer is proposed to provide estimate of the joint velocities.The observer design too employs the UDE-estimated uncertainty to achieve robustness,thus giving rise to the UDE-based controller–observer structure.Closed-loop stability of the controller–observer structure is estab-lished.The significant feature of the proposed approach is that it does not need any information about the uncertainties.Also,the design does not require accurate plant model and needs mea-surement of only link positions for its implementation.Effectiveness of the proposed approach is demonstrated through simulations with significant uncertainties in the system model.Next,numer-ical simulation results are presented by comparing the performance of the proposed approach with some well-known existing designs to highlight the performance benefits of the proposed design. Finally,hardware implementation of the proposed controller for trajectory tracking of Quanser’s single-linkflexible joint module is carried out,and the related results are presented.The remaining paper is organized as follows.In Section2,a mathematical model and FL-based controller design for the two-link robot manipulator is presented.An overview of the UDE approach and its application for robustification of the FL control is the subject of Section3.In Section4,the UDE-based controller–observer structure is presented whereas closed-loop stability of the overall system is presented in Section5.In section6,simulation results of the application of the proposed strategy are given.The results on comparative study of the proposed design with some well-known existing control strategies are the subject of Section7.In Section8,the results of the experimen-tal validation of the proposed design as applied to Quanser’s rigid linkflexible joint module are presented,and lastly,Section9concludes this work.2.STATEMENT OF THE PROBLEM2.1.Dynamics of robot manipulatorThe dynamics of a two-link rigid robot manipulator,shown in Figure1,can be obtained via the Euler–Lagrangian formalism as[20]106J.P.KOLHE ETAL.Figure 1.Two link planar robot manipulator.M.Â/R ÂC C.Â,P Â/C K.Â/D (1)where ÂD ŒÂ1Â2 T is the vector of joint positions,P ÂD ŒP Â1P Â2 T is the vector of joint velocities,M.Â/is the inertia matrix,C.Â,P Â/is the centripetal and Coriolis torque matrix,K.Â/represents the gravitational torques,and D Œ 1 2 T represents the input torque vector.For the two-link robotic manipulator,the various matrices appearing in Equation (1)can be obtained as M.Â/D "m 1l 21C m 2.l 21C l 22C 2l 1l 2cos Â2/m 2.l 22C l 1l 2cos Â2/m 2.l 22C l 1l 2cos Â2/m 2l 22#C.Â,P Â/D " m 2l 1l 2sin Â2P Â2.2P Â1C P Â2/m 2l 1l 2P Â21sin Â2#K.Â/D ".m 1C m 2/gl 1sin Â1C m 2gl 2sin .Â1C Â2/m 2gl 2sin .Â1C Â2/#(2)where l 1and l 2are the lengths of the links whereas m 1and m 2are the masses as shown in Figure 1.The quantity,g ,is the gravitational acceleration.The control objective is to design a robust con-troller using only joint position feedback such that the manipulator joint position vector,Â.t/,tracks the desired joint position Â?.t/as per the specifications imposed.2.2.Feedback linearization based controlThe FL [1,21]is one of the most prominent approaches in nonlinear control systems design.One of the advantages offered by the FL approach is that it provides a systematic framework for designing controllers for nonlinear systems.The inverse dynamics or computed torque methods in robotics are essentially the FL controllers.The basic idea underlying the FL is to seek a nonlinear state-coordinate transformation and nonlinear feedback control law under which the system exhibits linear closed-loop relationship.Once the system is linearized,any standard linear technique can be employed for designing the control law to achieve desired performance.To this end,the design consists typically of two steps:firstly,constructing a nonlinear control law as an inner-loop control and then designing a second stage or outer-loop control to obtain the desired closed-loop perfor-mance.In this work,the FL approach is employed for designing the tracking controller for robot manipulator.Consider the dynamics given by Equation (1).As the inertia matrix of the two-link robot manipulator is non-singular in the whole state-space,the dynamics can be rewritten asR ÂD M.Â/ 1C.Â,P Â/ M.Â/ 1K.Â/C M.Â/ 1 (3)For the system of (3),nonlinear coordinate transformation is not required,and the control,which achieves FL with the link positions as outputs can be obtained as [1]D C.Â,P Â/C K.Â/C M.Â/ (4)ROBUST CONTROL OF ROBOT MANIPULATORS BASED ON UDE107 where DŒ 1 2 T is the outer-loop control.Substituting the FL control(4)in Equation(3)results into a linear and decoupled input–output relationship asRÂD (5) Now,defining the outer-loop control, ,asi D RÂ?i C k i2.PÂ?i PÂi/C k i1.Â?i Âi/,i D1,2(6) where the starred quantities represent the reference trajectories of the corresponding link positions. Applying Equation(6)to Equation(5)results into the tracking error dynamics asR e ic C k i2P e ic C k i1e ic D0(7)where e ic.t/DÂ?i .t/ Âi.t/is the position tracking error of the i-th link.The controller gains,k ij,are the design parameters and are needed to be chosen such that desired tracking performance is achieved.As is well known,the FL control requires exact cancellation of the nonlinearities.It offers asymptotic tracking of the reference trajectory only when the models are known exactly,and the fed back states are measured without any error.In reality,these conditions are hard to meet,and so the FL control law may not offer satisfactory performance.Because modeling uncertainties are almost always present,there is a need to robustify the FL-based controller.Another important con-sideration in FL-based control law is its implementation.The controller requires knowledge of link velocities apart from the link positions.In view of the reasons stated earlier,it is necessary to address the issue of requirement of link velocities as well.3.UNCERTAINTY AND DISTURBANCE ESTIMATION BASED CONTROLLEROne approach for designing robust control for uncertain systems is to estimate the effect of uncer-tainties and disturbances acting on the system and compensate it by augmenting the controller designed for nominal system.Techniques like disturbance observer[22],unknown input observer [23],and perturbation observer[24]have been in place for quite sometime to estimate the effects of uncertainties and disturbances.Application of these techniques for estimating disturbance in robotic manipulators has also appeared[25,26].A time delay control(TDC)is one such well-known strat-egy used for estimation of system uncertainties[27].In TDC,a function representing the effect of uncertainties and external disturbances is estimated directly using information in the recent past,and then a control is designed using this estimate in such a way to cancel out the effect of the unknown dynamics and external disturbances.Application of TDC in robotics has also been reported in the literature[28,29].Following the line of TDC and addressing some issues associated with it,a novel UDE technique is proposed in[18].Since then,application of UDE in various contexts has appeared in the literature.An application of the UDE in robustifying a feedback linearizing control law for a robot having jointflexibility is presented in[30]wherein the effect of jointflexibility is treated as a disturbance.An application of UDE in overcoming the issues of requirement of knowledge of uncertainty bound and chattering in SMC can be found in[31].In[32]and[33],the UDE-based robust control designs for uncertain linear and nonlinear systems with state delays are presented, and the authors have shown that the designs offer excellent tracking and disturbance rejection per-formance.In[19],an application of the UDE in robustification of the input-output linearization (IOL)controller is presented,wherein the UDE-estimated uncertainties are used in robustifying an IOL controller.The robustification is achieved by estimating the uncertainties and external unmea-surable disturbances using the UDE and compensating the same by augmenting the IOL controller designed for nominal system.In this work,the UDE approach presented in[19]is used and extended for state estimation for designing of robust controller for robotic manipulators.3.1.FL+UDE controllerConsider the dynamics given by Equation(3).Because exact system model is rarely known in prac-tice,it becomes necessary to account for the modeling errors and inaccuracies.To this end,in the108J.P.KOLHE ET AL.present work,the inertia matrix,M.Â/is taken as uncertain with M.Â/D M o C M.Â/where M o is a chosen constant diagonal matrix and M.Â/is its associated uncertainty.Further,the matrices C.Â,PÂ/and K.Â/are assumed to be completely unknown.In view of the considered uncertainty in M../,the dynamics of Equation(3)can be rewritten asRÂDŒ M.Â/ 1C.Â,PÂ/ M.Â/ 1K.Â/C.M.Â/ 1 M 1o / C M 1oC d0(8)where d0may represent the effect of external disturbances,if any.Because C../and K../are assumed as completely unknown,they form a part of the total uncertainty d that needs to be estimated,and to this end,the total uncertainty d is defined asd D M.Â/ 1C.Â,PÂ/ M.Â/ 1K.Â/C.M.Â/ 1 M 1o/ C d0(9) In view of Equation(9),the dynamics of Equation(8)takes the formRÂD d C M 1o(10) where d DŒd1d2 T.With M o diagonal,it is straightforward to verify that the dynamics of Equation (10)is decoupled.In view of this,the dynamics for the i-th link can be written asRÂiD d i C b i i i I(11)where b i i are the diagonal elements of M 1o .To address the issue of the uncertainty,the FL controltakes the form asi D1b i i.u d i C i/I(12)where u d i is that part of the control,which cancels the effect of uncertainties.We designate the controller of Equation(12)as FL+UDE controller.Substituting Equation(12)in Equation(11) leads toRÂiD u d i C i C d i(13) From where one getsd i D RÂi u d i i(14) In view of Equation(14)and following the procedure given in[18,19],the estimate of d i is obtained asO diD G if.s/.RÂi u d i i/(15) where O d i is an estimate of d i,and G if.s/is afirst-order low passfilter with a time constant of if.G if.s/D11C if sI i D1,2(16)Selecting u d i D O d i and using Equation(15),one getsu d i D G if.s/.RÂi u d i i/(17) Now,solving for u d i leads tou d i D O d i DG if.s/1 G if.s/.RÂi i/(18)Substitution of Equations(6)and(18)in Equation(12)gives the FL+UDE controller.The time domain form of the resulting controller isi D1b i iÄ1ifPÂiC i C1ifZi dt(19)ROBUST CONTROL OF ROBOT MANIPULATORS BASED ON UDE109 Clearly,under the assumption of O d i d i,application of the control(19)to the dynamics of(10) results into the same error dynamics as given by Equation(7),thus eliminating the effect of uncer-tainties and therefore robustifying the FL controller.The robustified FL control(12)has been designated as the FL+UDE controller.Whereas the controller achieves the objective of robustifi-cation of the FL control,the implementation of the same requires measurement of joint positions as well as velocities as is obvious from Equation(19).The estimation of velocities are obtained by UDE-based observer as presented in the next section.4.UNCERTAINTY AND DISTURBANCE ESTIMATION BASEDCONTROLLER–OBSERVER STRUCTUREThe FL+UDE controller(12)or alternatively(19)requires link velocity measurement apart from the link positions for its implementation.As a solution to this problem,a design of UDE-based robust observer is proposed in this section.4.1.Uncertainty and disturbance estimation based observerAs is obvious from Equation(11),the dynamics are decoupled,and hence observer design for i-th link only is presented.To this end,defining x i1DÂi and x i2D PÂi,the dynamics of Equation(11) can be rewritten in a phase variable state-space model form asP x i1D x i2P x i2D b i i i C d iy i D x i1(20) Defining the state vector as x ip DŒx i1x i2 T DŒÂi PÂi T,the system of(20)can be written asP x ip D A ip x p C B ip i C B id d iy ip D C ip x ip(21)whereA ip D Ä0100I B ip DÄb i iI B id DÄ1I C ip DŒ10It may be noted that a conventional Luenberger observer will not be able to provide accurate state estimation for the plant of Equation(21),owing to the presence of the uncertainty.In view of this,a Luenberger-like observer of the following form is proposed asP O xipD A ip O x ip C B ip i C B id O d i C L i.y ip O y ip/O y ip D C ip O x ip(22) where L i DŒˇi1ˇi2 T is the observer gain vector.The observer however requires estimate of the uncertainty,that is,O d i.Because the uncertainty is the same as present in Equation(11),the UDE-estimated uncertainty is used in the observer(22)too,giving rise to the UDE-based controller–observer structure.It may be noted that the proposed observer does not need an accurate plant model and is robust.Noting that O x ip DŒO x i1O x i2 T DŒOÂi P OÂi T,the FL+UDE control of(12)with i of Equation(6)and u d i of Equation(18),both evaluated using the UDE observer estimated states given by Equation(22),the issue of requirement of link velocity measurement is addressed.5.CLOSED-LOOP STABILITYThe FL+UDE control(12)using i of Equation(6)evaluated using the observer estimated states and using u d i D O d i can be written asi D1b i ihRÂ?iC k i1.Â?i OÂi/C k i2.PÂ?i P OÂi/ O d ii(23)110J.P.KOLHE ET AL.Denoting the reference state vector R i DŒÂ?i PÂ?iT and defining the state feedback gain vector,K ipas K ip DŒm i1m i2 with the elements as m i1D k i1b ii ,m i2D k i2b ii,the controller(23)is rewritten asi D K ip O x ip C K ip R i1b i iO diC1b i iRÂ?i(24)It is straightforward to show that the dynamics of reference state vector,R i,can be written asP RiD A ip R i C B id RÂ?i(25) Defining the state tracking error,e ic D R i x ip and using Equations(21),(24),and(25),and carrying out some simplifications lead to the following state tracking error dynamicsP e ic D.A ip B ip K ip/e ic .B ip K ip/e io B id Q d i(26) where Q d i D d i O d i is the uncertainty estimation error,and e io D x ip O x ip is the observer state estimation error vector.Next,the observer error dynamics can be obtained by subtracting Equation(22)from Equation(21)asP e io D.A ip L i C ip/e io C B id Q d i(27) Lastly,the uncertainty estimation error dynamics is obtained.From Equations(14)and(15),the estimate of the uncertainty,d i,is given asO diD G if.s/d i(28) From Equation(28),one hasd i DO diG if.s/(29)With the uncertainty estimation error defined as Q d i D d i O d i and using Equation(16)and carrying out some simplifications giveP Q d i D1ifQ diC P d i(30)Combining Equations(26),(27),and(30)yields the following error dynamics for the controller–observer combination2 64P e icP e ioP Q d375D264.A ip B ip K ip/ .B ip K ip/ B id0.A ip L i C ip/B id00 1if375264e ice ioQ di375C2641375P di(31)From Equation(31),the system matrix being in a block triangular form,it can be easily verified that the eigenvalues of the system matrix are given byj sI .A ip B ip K ip/jj sI .A ip L i C ip/jj s .1if/j D0(32)Noting that the pair.A ip,B ip/is controllable,and the pair.A ip,C ip/is observable,the controller gain,K ip,and the observer gain,L i,can be chosen appropriately along with if>0to ensure sta-bility for the error dynamics.As the error dynamics is driven by P d i,it is obvious that,for bounded j P d i j,bounded input-bounded output stability is assured.Finally,if the rate of change of uncertainty is negligible,that is,if P d i 0,then the error dynamics is asymptotically stable.As has been stated,the error dynamics(31)is asymptotically stable if P d i 0.However, asymptotic stability for the error dynamics can always be assured if some higher derivative ofROBUST CONTROL OF ROBOT MANIPULATORS BASED ON UDE111 the uncertainty is equal to zero.For example,if P d i¤0but some higher derivative of d i is zero, then the asymptotic stability of the error dynamics can be guaranteed by choosing an appropriate higher-orderfilter[19]in place of the one chosen in Equation(16).As stated in Section3.1,the u d i is that part of control,which cancels the effect of uncertain-ties.It is important to address the issue of existence of such a control.Although a detailed study on the existence of u d i is not attempted here,some comments can be offered.The control u d i is derived under the assumption that some derivative of d i is negligibly small,that is,any d i that can be approximated by functions of the type a o C a1t C a2t2C...where a i,i D1,2,:::are unknown constants.The control,u d i,does not exist for systems in which d i,P d i and so on are discontinuous. For systems where the derivatives of d i arefinite and small,instead of asymptotic stability,one may get uniform ultimate boundedness.This facilitates the design of u d i in many practical situa-tions.Now some comments on the choice of thefilter time constant are in order.From Equations (29)–(30),it can be observed that the choice of thefilter time constant, if,affects the uncertainty estimation error accuracy,that is,the uncertainty estimation error,Q d i,is proportional to if imply-ing that smaller value of thefilter constant leads to a smaller estimation error.It can also be noted that estimation does not depend on the magnitude of the uncertainty as such,but does depend on its rate of change.Further,one can note that thefilter time constant acts as the time constant of the uncertainty estimation error dynamics,meaning that smaller value of thefilter constant leads to faster uncertainty estimation convergence.From control efforts’point of view,the magnitude of the control increases with1= if as is evident from Equation(19).Thus,the choice of thefilter con-stant is a tradeoff between estimation accuracy and its rate of convergence on the one hand,and the control efforts on the other hand.6.SIMULATIONS AND RESULTSIn this section,numerical simulation results using the FL+UDE controller of(12)with i of Equation(6)and u d i of Equation(18),both evaluated using the UDE observer estimated states given by Equation(22)are presented.The link parameters used in the simulations,as taken from [34],are given in Table I.In simulations,the tracking specification for each link is considered in terms of the desired settling time and damping ratio as given in Table I.Consequently,the controller gains k i1and k i2required in Equation(6)are chosen to satisfy these specifications.The observer gains,ˇij’s are obtained by placing the observer poles at 300for both the links.The initial condi-tions for the observer as well as for the plant variables are taken as zero.In simulations,uncertainty is introduced by considering m1and m2uncertain by 50%of their respective nominal values. Further,a load disturbance torque of 30%of maximum input torques is considered.The desiredposition trajectory is taken asÂ?1D30sin.t/deg andÂ?2D 30sin.t/deg.The values of b i iare taken as inverse of the diagonal elements of the inertia matrix given in Equation(2)with cosine term approximated to unity.Actuator saturation limits of 1max D˙50N-m and 2max D˙10N-m have been considered in the simulations.With these data,simulations are carried out,and the results are presented in Figure2.In Figures2(a)–(b),the reference,estimated and actual joint positions are plotted,and it can be seen that the observer estimates the states accurately.Also,from time historyTable I.Simulation parameters.Parameter Definition Valuem1Mass of link12kgm2Mass of link21kgl1Length of link12ml2Length of link21mg Gravitational acceleration9.8m/s2t s1,t s2Desired settling times0.5s1, 2Damping ratios11f, 2f Filter time constants0.05s112J.P.KOLHE ETAL.−30−20−100102030−30−20−1001020300246810−40−202040600246810−200204060(a)(b)(c)(e)(f)(g)(h)(d)Figure 2.Performance of UDE-based controller.ROBUST CONTROL OF ROBOT MANIPULATORS BASED ON UDE113 of reference trajectory,it can be seen that the UDE-based controller–observer offered a highly sat-isfactory tracking performance despite the significant model uncertainty.The reference,estimated and actual link velocities are given in Figures2(c)–(d),and one can observe that the estimation is quite satisfactory.The time histories of the actual and estimated uncertainties for both the links are given in Figures2(g)–(h)from where it can be observed that the UDE estimator has estimated the uncertainty quite accurately.The time histories of the input torques are shown in Figures2(e)–(f).PARISON WITH EXISTING DESIGNSSimulations are carried out to compare the performance of the proposed design with some well-known existing controllers.The controllers considered for comparison purpose are:(1)gravity compensated PD control;(2)FL-based control;(3)FL controller with Lyapunov-based outer-loop design;and(4)controller based on SMC theory.A brief of the controllers are as follows:Design-1:Proportional-derivative control with gravity compensation.A gravity-compensated PD controller[1]of the following formD K p.Â? Â/C K d.PÂ? PÂ/C N K.Â/(33) where K P>,K D>0are the diagonal gain matrices,and N K.Â/is the nominal gravity matrix.It has been shown that the simple PD controller with gravity compensation offers robustness for set-point control of robot manipulators[12].For simulations,gains K P and K D are chosen to satisfy the desired settling time and damping ratio given in Table I.The design is referred to as Design-1. Design-2:Feedback linearization based control.An FL[1]-based controller without robustification is considered as Design-2for comparison.The control law isD N C C N K C N M (34) where N M,N C,and N K are the nominal values for the respective matrices,which are obtained from Equation(2)by using the parameters given in Table I.The outer-loop control, ,is chosen asD RÂ?C K P.Â? Â/C K D.PÂ? PÂ/(35) wherein K P and K D are the diagonal gain matrices chosen in similar manner as carried out in Design-1.Design-3:Lyapunov-based control.FL control with Lyapunov-based outer-loop design given in[1]is used as Design-3in this ing Lyapunov’s second method,the control law designed for two-link robot manipulator takes the formD N C C N K C N M (36) with the outer-loop design given byD RÂ?C K P.Â? Â/C K D.PÂ? PÂ/C W(37)where W DŒW1W2 T withW i D 8<:D i B T i P i e ij B TiP i e i jif j B TiP i e i j> iD i B T i P i e iif j B TiP i e i j< i,i D1,2(38)The P i is a unique symmetric positive definite matrix satisfying the Lyapunov equationA T i P i C P i A i C I D0(39)。

微小型跳跃机器人:仿生原理,设计方法与驱动技术

第21卷第12期2023年12月动力学与控制学报J O U R N A L O FD Y N AM I C SA N DC O N T R O LV o l .21N o .12D e c .2023文章编号:1672G6553G2023G21(12)G037G016D O I :10.6052/1672G6553G2023G133㊀2022G05G15收到第1稿,2022G09G18收到修改稿.∗国家自然科学基金资助项目(52075411,52305034),N a t i o n a lN a t u r a l S c i e n c eF o u n d a t i o no fC h i n a (52075411,52305034).†通信作者E Gm a i l :l i b o x j t u @x jt u .e d u .c n 微小型跳跃机器人:仿生原理,设计方法与驱动技术∗吴业辉1,2㊀刘梦凡1,2㊀白瑞玉1,2㊀李博1,2†㊀陈贵敏1,2(1.西安交通大学机械制造系统工程国家重点实验室,西安㊀710049)(2.西安交通大学陕西省智能机器人重点实验室,西安㊀710049)摘要㊀高爆发性的跳跃是生物亿万年进化演变中赖以生存的关键之一,帮助生物实现在各种非结构化环境下的灵活运动功能.通过对生物跳跃机制的深入理解,微小型跳跃机器人在功能及性能上取得长足进步.本文以生物跳跃运动四个阶段(准备㊁起跳㊁腾空和着陆)为主线,剖析了生物的行为原理,介绍了对应的微小型跳跃机器人的动力学特征与技术,归纳了现有研究的挑战,最后讨论了跳跃机器人的未来发展趋势和潜在研究价值.关键词㊀跳跃机器人,㊀生物跳跃机制,㊀仿生中图分类号:T P 242文献标志码:AAR e v i e wo f S m a l l GS c a l e J u m p i n g Ro b o t s :B i o GM i m e t i cM e c h a n i s m ,M e c h a n i c a lD e s i gna n dA c t u a t i o n ∗W uY e h u i 1,2㊀L i u M e n g f a n 1,2㊀B a iR u i yu 1,2㊀L i B o 1,2†㊀C h e nG u i m i n 1,2(1.S t a t eK e y L a b o r a t o r y o fM a n u f a c t u r i n g S y s t e m E n g i n e e r i n g ,X i a n J i a o t o n g U n i v e r s i t y ,X i a n ㊀710049,C h i n a )(2.S h a a n x i P r o v i n c eK e y L a b o r a t o r y f o r I n t e l l i g e n tR o b o t s ,X i a n J i a o t o n g U n i v e r s i t y,X i a n ㊀710049,C h i n a )A b s t r a c t ㊀H i g h l y e x p l o s i v e j u m p i n g i s o n e o f t h e s u r v i v a l k e y s t o t h e o r ga n i s me v o l u t i o no v e r t h e c o u r s e o fb i l l i o n s o f y e a r s .T h i sm o v e m e n t h e l p s o r ga n i s m s t oa c h i e v e f l e x ib l em o v e m e n t f u nc t i o n su nde rv a r i Go u s u n s t r u c t u r e d c o n d i t i o n s .T h r o u g ha n i n Gd e p t hu n d e r s t a n d i n g o fb i o l o g i c a l j u m p i n g me c h a n i s m ,t h e s m a l l Gs c a l e j u m p i n g r o b o t h a sm a d e g r e a t p r o g r e s s i nf u n c t i o na n d p e r f o r m a n c e .T a k i ng th e f o u r s t a ge s of b i o l og i c a l j u m p i n g m o v e m e n t (p r e p a r a t i o n f o r t a k e Go f f ,t a k e Go f f ,f l i gh t a n d l a n di n g)a s t h em a i n l i n e ,t h i s p a p e r r e v i e w s t h e b e h a v i o r a l p r i n c i p l e o f o r g a n i s m s ,i n t r o d u c e s t h e d yn a m i c c h a r a c t e r i s t i c s a n d t e c h Gn o l o g y o f t h e c o r r e s p o n d i n g s m a l l Gs c a l e j u m p i n g r o b o t s ,s u mm a r i z e s t h e c h a l l e n g e s o f e x i s t i n g r e s e a r c h ,a n d f i n a l l y d i s c u s s e s t h e f u t u r e d e v e l o p m e n t a n d p o t e n t i a l o f j u m p i n g r o b o t s .K e y wo r d s ㊀s m a l l Gs c a l e j u m p i n g r o b o t s ,㊀b i o l o g i c a l j u m p i n g m e c h a n i s m ,㊀b i o n i c 引言随着现代社会中机器人作业任务难度的提高,机器人在运动模式上也进入了全面发展的阶段,已经形成足式[1]㊁轮式[2]㊁蠕动式[3G5]㊁翻滚式[6,7]等多元化的研究体系,在生产协作㊁社会服务㊁医疗康复等场景下发挥着越来越重要的作用.但是一些非结构化的场景如星球探索㊁抢险救灾㊁环境监测,对机动㊀力㊀学㊀与㊀控㊀制㊀学㊀报2023年第21卷器人的运动性能提出了更高的要求.机器人需要以更小的体积适应狭小空间环境,快速翻越数倍于自身尺寸的障碍,还需要携带一定负载来完成通讯㊁检测㊁运输等功能,因此机器人在小体积㊁大负载㊁高能量密度㊁高爆发性㊁高灵活性等功能的发展有待提升.作为生物界一种独特的运动模式,跳跃运动在蝗虫[8,9]㊁跳蚤[10,11]等昆虫中经历了万亿年的演变,可与奔跑㊁飞行㊁游泳等运动模式相结合,帮助动物以极快的速度逃避天敌㊁捕食猎物,增强了生物的越障能力,使其更好的适应丛林㊁山地等复杂多变的地形.为了探寻生物产生爆发性跳跃运动的原因,科学家对各类具有出色跳跃性能的生物进行研究,发现生物体内弹性储能与闩锁结构的组合是解决微小型动物在爆发驱动中功率受限的关键[12].像沫蝉(F r o g h o p p e r s)[13G15]㊁跳蚤(F l e a s)[10,11]㊁叩头虫(C l i c kb e e t l e s)[16G18]㊁蝗虫(G r a s s h o p p e r s或L oGc u s t s)[8,9]㊁弹尾虫(S p r i n g t a i l s)[19G21]等节肢动物,通过弹性蛋白㊁角质层等进行储能,利用身体中闩锁机构控制能量的锁定和释放,能够完成其自身尺寸的几十倍甚至上百倍的跳跃运动;青蛙(F r o g s)[22,23]等生物虽然没有特定的闩锁机构,但是具有可变的有效机械效益(E MA,E f f e c t i v em eGc h a n i c a l a d v a n t a g e)的腿部,利用腿部肌肉所串联的肌腱进行功率放大,增强了自身的跳跃性能.根据仿生学原理,以微小型生物跳跃机理为灵感的跳跃机器人近些年得到了快速发展,其跳跃性能取得长足进步.到目前为止,机器人可实现单次约33m的跳跃高度[24],是其自身特征尺寸的百倍以上,也可以实现像夜猴一般敏捷的连续跳跃[25];不仅能像蝗虫一般在路上跳跃,也如水黾一般从水面跳跃[26],甚至有望实现在半空中跳跃[27].现如今,跳跃机器人的研究向集成化㊁多功能方向发展,在对大自然的学习中获得了各类生物跳跃相关的各类技能,逐步实现对生物的超越.综合考虑机器人的灵活性与负载能力,本文将集中讨论微小型的跳跃机器人(特征尺寸在30厘米以内),从跳跃运动的起跳㊁腾空㊁着陆㊁准备四个基本阶段[28]出发,对微小型生物跳跃及相关行为的机理进行综述,分析不同生物在储能与释放㊁腾空姿态㊁着陆缓冲㊁方向调整等方面的优势;在此基础上,对比现有的跳跃机器人各阶段功能的实现方式,结合生物特点分析仿生跳跃机器人的未来发展趋势以及面临的挑战,为其实现广泛应用提供设计参考.1㊀微小型动物的跳跃运动原理同其他具有跳跃功能的物种一样,微小型生物的跳跃行为可按照运动的状态的不同分为四个阶段,包括跳跃前的准备阶段㊁加速起跳阶段㊁腾空滑行阶段和落地缓冲阶段,如图1所示.在各个阶段,不同的生物根据自身生存条件的不同,进化出与各自所处环境相适应的跳跃特点,而受生物启发的跳跃机器人正是基于这些特点在高爆发㊁高集成㊁高灵活性等方面实现突破.图1㊀跳跃运动的四个阶段F i g.1㊀T h e f o u r p h a s e s o f a j u m p i n g m o t i o n 1.1㊀起跳阶段在起跳阶段,生物体从肌肉㊁弹性元件等驱动单元内获得能量,完成从静止状态至脱离地面的加速运动过程.在驱动方式方面,微小型生物由于四肢短小且无法形成高主动应变率的肌肉[29],因此多以机械储能的方式增大起跳功率,同时与闩锁结构的控制相配合,完成能量在短时间内的可控释放.此方式尤其体现在主要依靠弹性储能产生跳跃的生物中,如叩头虫[16G18]利用骨骼结构之间物理接触的作为闩锁来锁定弹性能[如图2(a)所示],该类型被称为接触式闩锁[30];瘿蚊幼虫(t h e M e d iGt e r r a n e a n f r u i tGf l y l a r v a)[31,32]利用首尾钩状结构或微纳结构等摩擦接触将身体连接成环状,从而限制自身的形变,进而通过肌肉挤压内部液体来储存跳跃所需的弹性能[图2(b)];跳蚤[10,11,33]㊁蝗虫[8,9]㊁沫蝉[13G15]等生物则利用跳跃机构的几何构型作为闩锁,而并非通过接触的方式实现弹性能量存储[图2(c)],该类型也被称为几何式闩锁.青蛙[22,23]㊁蟋蟀(C r i c k e t s)[34]等生物由于具有较长的后肢而具有较长的驱动行程,而可以通过肌肉直接驱动的方式获得优异的跳跃性能.但是由于83第12期吴业辉等:微小型跳跃机器人:仿生原理,设计方法与驱动技术肌腱与肌肉的串联,青蛙同时也借助弹性元件来增强跳跃的驱动功率,其运动过程中同样存在几何闩锁[12],锁定效果可通过 有效机械效益 (E MA)来衡量.对于跳跃运动而言,E MA是地面对生物的支反力(G R F)和肌肉驱动力(F)的比值(E MA=G R F/F),可以表示串联弹性系统中肌肉所做的功流向弹性储能的大小,如图2(d)所示.E MA较小表示肌肉做功转化为串联弹性元件中储能,而不是直接驱动肢体加速跳跃;反之,表示肌肉做功大部分用于直接驱动,而非利用弹性元件储能.因此,如果E MA可以随肌肉收缩产生 阶跃 式的由小增大过程,则可以将其视为具有动力学 闩锁 ,前期储存的机械能也将在高E MA水平期间释放,从而达到增强跳跃瞬间功率的目的.此外,同样采取直接驱动方式的跳蛛(J u m pGi n g s p i d e r s)[35G39]可以利用肌肉驱动 液压 关节完成腿部的快速伸展,从而完成跳跃运动[图2(e)],为跳跃运动的驱动实现提供了新的灵感[40].图2㊀起跳阶段生物行为与机理.a.叩头虫利用骨骼作为接触式闩锁储能[16G18];b.瘿蚊幼虫利用嘴钩作为闩锁而锁定自身形状[31,32]; c.跳蚤采用几何式闩锁(扭矩反转机构)锁定机械能[10,11,33];d.青蛙利用串联弹性元件增大跳跃功率[22,23];e.蜘蛛采用液压直驱的方式跳跃[35G39] F i g.2㊀B i o l o g i c a l b e h a v i o r a n dm e c h a n i s m s d u r i n g t a k e o f f.a.C l i c k b e e t l eu s e s s k e l e t o na s c o n t a c t l a t c h t o s t o r e e n e r g y[16G18]; b.T h eM e d i t e r r a n e a n f r u i tGf l y l a r v a s u s em o u t hh o o k s a s l a t c h e s t o l o c kb o d y s h a p e[31,32];c.F l e a s u s e g e o m e t r i c l a t c h(t o r q u er e v e r s a lm e c h a n i s m)t o s t o r em e c h a n i c a l e n e r g y[10,11,33]; d.F r o g s u s e s e r i e s e l a s t i c e l e m e n t s t o i n c r e a s e j u m p i n g p o w e r[22,23];e.S p i d e r s j u m p i n g d r i v e nb y h y d r a u l i c f o r c e[35G39]1.2㊀腾空阶段在腾空阶段,生物体完成受空气阻力和自重影响下的斜抛运动,直至其身体与地面接触.许多生物虽然拥有相对自身尺寸数十倍的跳跃能力,但是在腾空之后不具备姿态调整功能,因此无法控制滑行时的轨迹和着陆时的姿态.在半空中姿态重新定位被称为适应性行为矫正,分为被动方式和主动方式[41].被动方式如豌豆蚜虫(A c y r t h o s i p h o n p iGs u m)在高空坠落过程中不需要来自神经系统的动态控制或持续反馈,只是通过空气动力学稳定的姿势来被动地纠正自己[42];其他跳跃生物则通过翅膀[43]㊁肢体[21]㊁尾巴[44]等部位主动调整身体姿态.相对而言,被动方式需要的控制单元少,但是对环境依赖程度更高,而主动方式则更多见.为了适应不同的着陆角度,跳甲(F l e ab e t t l e s)根据所感知到的着陆点角度等信息,通过翅膀的主动运动来调整自身姿态,有效提高正面着陆的概率(如图3(a)所示),同时却并不影响其跳跃的高度.白粉虱(W h i t e f l i e s)[43]也采取相同的策略,仅仅通过翅膀的伸展即可完成空中的稳定飞行,以防止翻筋斗,如图3(b)所示.图3㊀腾空阶段生物行为与机理.a.跳甲利用翅膀调整腾空姿态[41];b.白粉虱利用翅膀防止翻筋斗[43];c.弹尾虫利用腹管和 U 型姿势调整腾空状态[21]F i g.3㊀B i o l o g i c a l b e h a v i o r a n dm e c h a n i s m s d u r i n g f l i g h t.a.F l e ab e t t l e s a d j u s t a e r i a l p o s t u r ew i t hw i n g s[41]; b.W h i t e f l i e s p r e v e n t s o m e r s a u l t sw i t hw i n g s[43];c.S p r i n g t a i l a d j u s t a i r b o r n e s t a t e sw i t h c o l l o p h o r e a n d"U"s h a p eb o d y[21]除了以上具有飞行能力的生物,半水生的弹尾虫[21]虽然没有翅膀却同样可以实现姿态矫正的功能.弹尾虫在起跳之前将腹部紧贴水面,通过具有亲水性的腹管收集水滴来改变自身的质量分布,在起跳之后将整个身体弯曲成U型,这两种行为都有助于矫正倾斜的姿态,并且避免了着陆前的翻转,如图3(c)所示.1.3㊀着陆阶段在着陆阶段,生物体依靠阻尼损耗㊁弹性储能93动㊀力㊀学㊀与㊀控㊀制㊀学㊀报2023年第21卷等方式把自身的运动减速至静止状态.跳跃生物的缓冲方式也分为主动型和被动型,包括利用空气阻力的滑翔运动㊁变角度着陆足㊁吸收冲击的保护壳㊁变刚度肢体等.如生活在热带雨林中的飞蛙(G l iGd i n g f r o g s)[45,46],依靠宽大的脚掌和趾间的蹼膜完成滑翔运动,并且具有较强的被动空气动力学稳定性,可以从树干高处快速降落来捕捉猎物或逃避天敌.滑翔运动有效改变着陆时的速度方向并通过较大的空气阻力降低速度大小,从而明显降低着陆时对地的冲击速度[47],如图4(a)所示.无论是否具有滑翔功能,青蛙均利用前肢进行主动着陆缓冲,前肢接触地面并形成一个支点,身体围绕这个支点旋转,直至完成后肢落地[48].在着陆过程中,青蛙根据跳跃高度㊁水平速度的不同调整前肢的着陆角度,从而获得最小的冲击,如图4(b)所示.图4㊀着陆阶段生物行为与机理.a.飞蛙利用脚蹼实现滑翔运动[45G47]; b.青蛙前肢着陆过程中最小冲击角度调整[48];c.瓢虫利用相互耦合的鞘翅进行缓冲,耦合面形状如图中红蓝曲线所示[49]F i g.4㊀B i o l o g i c a l b e h a v i o r a n dm e c h a n i s m s d u r i n g f l i g h t.a.F r o g s g l i d i n g w i t h f l i p p e r s[45G47];b.A d j u s t i n g o f f r o g f o r e l i m ba n g l e f o r m i n i m u mi m p a c t d u r i n g l a n d i n g[48];c.E l y t r a c o u p l i n g o f l a d y b i d s f o r b u f f e r i n g,a n d t h e s h a p e o f t h e c o u p l e d s u r f a c e i sh i g h l i g h t e di n t h e r e da n db l u e c u r v e s[49]瓢虫(L a d y b i r d s)㊁甲虫等昆虫大多利用壳体减小冲击对自身的冲击,其中瓢虫除了采用由甲壳素微纤维和蛋白质组成的具有空腔的壳体来吸收能量,还利用成一定角度㊁相互耦合的翅鞘增强缓冲功能,以提供更多的能量吸收并减少碰撞后的反弹[49],如图4(c)所示.如1.1节所述的瘿蚊幼虫,依靠柔软的身体进行储能跳跃的同时,也能利用身体足够柔软的特点吸收着陆冲击,使其无需采用专用的缓冲结构.与有足动物类似,相较于起跳阶段肌肉运动产生的高刚度,着陆时其身体刚度显然有所降低,有利于增大着陆冲击力的作用时间,从而降低冲击力的大小.1.4㊀准备阶段在准备阶段,生物体完成姿态恢复㊁跳跃能量储备㊁跳跃目标位置确定㊁跳跃方向和角度调整等工作.对于利用双足来进行跳跃的生物而言,其跳跃方向大多朝自身的正前方,依靠双足的同步运动来完成.像伊苏斯飞虱(I s s u s c o l e o p t r a t u s)在幼虫阶段时,由于其起跳所用时长为毫秒级,而神经信号同样为毫秒级,因此在双腿同步性控制方面具有很大难度.为了保证跳跃方向准确性,避免跳跃之后身体旋转和方向偏离,伊苏斯虫利用带有齿轮状的肢体保证了起跳时双腿的同步性[50],如图5(a)所示.为了从倾倒之后的 四脚朝天 姿态中恢复,常见的昆虫如蟑螂(C o c k r o a c h e s)㊁瓢虫等均可根据不同的地形,利用鞘翅㊁腿足的配合可以通过不同的策略完成翻身运动.其中,蟑螂可以采取腹部弯曲侧滚㊁鞘翅翻滚㊁腿部侧滚等策略[51,52],如图5(b1)~(b3)所示.相较于蟑螂,瓢虫[53]的腿部较短,在粗糙表面多依靠足部勾住隆起物而翻转扶正,在光滑表面则依靠鞘翅来辅助翻滚.图5㊀准备阶段生物行为与机理.a.伊苏斯虫利用齿轮状肢体保证了双腿起跳同步性[50];b.蟑螂利用腹部㊁鞘翅和腿部实现翻身[51,52];c.弹尾虫通过不同初始角度调整跳高㊁跳远两种模式[21]F i g.5㊀B i o l o g i c a l b e h a v i o r a n dm e c h a n i s m s d u r i n g p r e p a r a t i o n o f t a k e o f f.a.I s u s i a e n s u r i n g t h e s y n c h r o n i z a t i o no f b o t h l e g s i n j u m p i n g w i t h g e a r e d l i m b s[50].b.C o c k r o a c h e s t u r n i n g o v e r b y a b d o m e n, e l y t r a a n d l e g s[51,52];c.S p r i n g t a i l s w i t c h e s b e t w e e n j u m p a n dl o n g j u m p m o d eb y a d j u s t i n g d i f f e r e n t i n i t i a l a n g l e s[21]04第12期吴业辉等:微小型跳跃机器人:仿生原理,设计方法与驱动技术在跳跃角度控制方面,青蛙等常利用腿部不同关节的协调运动来实现[54,55].对于半水生的弹尾虫而言,除了利用跳跃尾部的不同作用力,还可以通过调整跳跃前的初始角度并利用腹管的亲水性,实现跳高㊁跳远两种模式的切换[21],如图5(c1)和图5(c2)所示.2㊀跳跃机器人的设计与驱动方法从上世纪八十年代开始,结合对跳跃生物能量存储机制等问题的研究,科学家们开始致力于跳跃机器人的研究[56],各类仿生跳跃机器人不断涌现并逐渐成为热点[24G26,57].2.1㊀跳跃机器人储能结构与能量调控类比于生物所采用的弹性蛋白㊁角质层㊁肌腱㊁体液等储能元件,跳跃机器人多采用人造弹性元件,包括螺旋弹簧㊁扭簧㊁形状记忆合金弹簧㊁柔性梁㊁弹性绳等,不同类型的弹性元件具有不同的储能密度和变形形式,其特点直接影响机器人的跳跃能力和运动形式.L a m b r e c h t等人设计了一种仿蟑螂轮腿式机器人[58,59],该机器人利用差齿齿轮旋转拉伸螺旋弹簧而实现能量的加载和释放,当作用齿轮达到差齿位置时,平行四连杆跳跃机构随弹簧释放而弹出,推动机器人产生向前的跳跃,而 Y 形三脚架模拟昆虫足部来实现爬行和小型障碍的跨越,如图6(a)所示.由于集成跑㊁跳运动模式,其质量达到190克,因此跳跃能力只能达到18厘米,如图6(b)所示.图6㊀M i n iGW h e g s机器人[58,59]F i g.6㊀R o b o tM i n iGW h e g s[58,59]Y a m a d a等人利用细长悬臂梁在末端压弯载荷下屈曲失稳现象设计了一种跳跃机器人,定义为 封闭式弹性弹射器 [60,61],如图7(a)所示.该机器人采用柔性梁的屈曲进行储能并可在末端旋转电机的带动下实现能量可控释放,既可以利用单电机实现二阶屈曲到一阶屈曲的能量释放,也可以采用对称布置的双电机实现三阶屈曲到一阶屈曲的能量释放,达到一定跳跃方向改变.储能和释放结构的集成使其结构简单,梁的形状及其两端角度变化对释放能量的大小和快慢起决定性的影响,梁变形过程如图7(b)所示.该机器人在单电机驱动下可跳跃20厘米高㊁70厘米远.图7㊀封闭弹性弹射机器人[60,61]F i g.7㊀A j u m p i n g r o b o t b a s e do n t h e c l o s e d e l a s t i c a[60,61]J u n g等人提出一种仿甲虫爬跳结合的机器人J u m p R o A C H[62],如图8(a)所示.通过对线弹簧和扭簧的组合,机器人储能元件力位移特性近乎于恒力机构,最大程度的利用电机的负载能力从而扩大了其储能能量,如图8(b)所示.机器人通过电机卷绳方式加载,采用行星轮系作为能量锁定和释放机构,能够起到控制能量加载大小的作用.除此之外,该机器人结合了跳跃和爬行两种运动模式,具备完整的重复跳跃能力.在测试中,无爬行部分的机构可以实现2.75米的跳跃,而结合爬行和复位壳体部分之后体重增加一倍,仍然能实现1.5米高的跳跃,越障过程如图8(c)所示.图8㊀J u m p R o A C H跳跃机器人[62]F i g.8㊀R o b o t J u m p R o A C H[62]在此基础上,H a w k s等人利用柔性梁和线弹簧的组合方式达到了类似的恒力效果,在不超过电机最大功率条件下,牺牲加载速度而能够以最大恒力进行弹性能量加载,如图9(a)所示.根据其理论,弹簧-连杆质量比越大的机器人其最终能量密度越高,因此以柔性梁作为弹簧和腿部的集成,可以很大程度增加跳跃高度;借助A s h b y图[63]对材料14动㊀力㊀学㊀与㊀控㊀制㊀学㊀报2023年第21卷进行优化,选择碳纤维复合材料和乳胶组合构成储能元件,最终使重量30.4克的机器人[图9(b)]实现了32.9米的跳跃高度,这也是目前最高的机器人绝对跳跃高度[24].图9㊀目前跳得最高的机器人[24]F i g.9㊀T h eh i g h e s t j u m p i n g r o b o t s o f a r[24]除了储能大小和变形方式上的差异,不同的储能元件在跳跃运动中其动力学模型复杂度也不同,如通过柔性梁的大变形进行储能的模式比线性弹簧结合刚性连杆的方式更为复杂.起跳过程的动力学分析主要用于预测机器人起跳速度和高度,因此对于难以建立动力学模型的间歇型跳跃机器人(落地后无需立即起跳)一般直接利用弹簧的弹性变形能来估计跳跃高度;对于连续型跳跃机器人由于涉及到机器人的姿态㊁方向等控制,触地瞬间至起跳离地过程的动力学模型更为关键.2.2㊀跳跃机器人闩锁结构与能量动态释放在依靠弹性储能进行跳跃的机器人中,闩锁机构控制能量的释放过程,不同的结构不仅影响能量的存储量,而且对释放过程的动力学特征(势能转化为动能的时间㊁空间和速率等)起到决定性作用[12].闩锁结构除了前文所述的接触式㊁几何式闩锁,还包括流体式锁闩[64],其中流体式闩锁是指由系统内流体的运动和性质(包括凝聚力㊁聚结性和压力)对弹性元件进行调节;而接触式闩锁是指通过摩擦和机械限位的作用来阻挡弹性元件运动[30],如图10(a)所示;几何式闩锁则是基于几何构型㊁力㊁力矩臂㊁质心位置等的状态相关行为的锁闩,包括像青蛙㊁夜猴等体内的可变机械效益机构[65][图10(b)]㊁跳蚤体内的扭矩反转机构[66][图10(c)]㊁失稳突跳机构和其他具有双稳态特点的系统[67G71][图10(d)].K o v a c等人设计的 7g 的跳跃机器人如图11所示,采用凸轮和扭簧作为释放和储能机构,其跳跃高度由凸轮的形状和弹簧刚度所决定,跳跃方向与凸轮形状和腿部尺寸相关,一旦装配完成则无法调整,其运动灵活性因此受到一定限制.约5厘米高的机器人可以跳跃自身高度的27倍,达到1.4米[72],如图11(b)所示;携带3克负载后跳跃高度仍能达到1米,如图11(c)所示.图10㊀常见的闩锁结构.a.接触式闩锁简化模型[30];b.青蛙等生物体内的可变机械效益结构[65]; c.跳蚤体内的扭矩反转机构[66];d.屈曲梁双稳态机构[67G71] F i g.10㊀C o mm o n l a t c h s t r u c t u r e s.a.S i m p l i f i e dm o d e l o f c o n t a c t l a t c h[30];b.V a r i a b l em e c h a n i c a l a d v a n t a g e s t r u c t u r e i n f r o g s a n d o t h e r o r g a n i s m s[65];c.T o r q u e r e v e r s a lm e c h a n i s mi n f l e a s[66]; d.B i s t a b l em e c h a n i s ma n d e n e r g y c u r v e o f b u c k l i n g b e a m[67G71]图11㊀ 7g 机器人[72]F i g.11㊀R o b o t 7g [72]Z a i t s e v等人模拟蝗虫跳跃过程设计了一种仿蝗虫跳跃机器人[73,74],如图12(a)所示.通过单个电机的正反转,利用丝杠螺母在轴向运动以及绳在卷24第12期吴业辉等:微小型跳跃机器人:仿生原理,设计方法与驱动技术轴上的卷绕运动,巧妙的实现了锁扣作用下能量加载和释放的循环,如图12(b )中(ⅰ)~(ⅵ)所示.显然,这种机器人跳跃的实现十分依赖于对绳长㊁螺母移动距离㊁锁钩和足部杆几何关系等进行精确设计和装配.同样,该机器人无法进行跳跃角度㊁高度的调整,且两条绳子无约束地释放可能会造成打结㊁干涉等不稳定现象.该机器人实现了25倍自身体长的跳跃,达到3.35米的高度.图12㊀仿蝗虫机器人[73,74]F i g .12㊀L o c u s t Gi n s pi r e d r o b o t [73,74]图13㊀高度可调的仿生跳跃机器人[75]F i g .13㊀B i o n i c j u m p i n g r o b o tw i t ha d j u s t a b l eh e i gh t [75]M a 等人提出一种综合软体动物㊁硬壳跳虫弹跳机理的跳跃机器人[75],如图13(a)所示.该机器人采用屈曲镍钛合金板和扭簧作为储能元件,释放机构采用了与J u m p R o A C H 机器人(图8)相似的行星轮系结构,并加入了单向轴承来加强能量释放过程的稳定性,如图13(c )中右图所示.当电机沿顺时针方向正转时,动力经三个齿轮传递至卷绳齿轮轴,通过卷绕刚性绳拉动机构变形进行储能,整个过程单向轴承处于内外圈滑动状态而不产生阻力;相反,当电机沿逆时针方向反转时,单向轴承锁紧并使行星架与卷绳齿轮轴脱开,卷绳瞬间释放.由于加载量随电机正转圈数而定,因此机器人具备跳跃高度可调的特点.该机器人可以在无壳体状态下达到最高1.51米的跳跃高度,如图13(b)所示.对于上述各种接触式闩锁,一般具有简单的结构,常采用挡块㊁凸轮㊁差齿齿轮等方式实现能量的锁定,除了上述行星轮系结构,其它锁定方式下的能量值多为固定不可调整的,同时意味着其控制难度低,常采用开环或者位移闭环进行控制其释放.此外,接触式闩锁存在摩擦损失大㊁释放瞬间冲击大等缺点.图14㊀仿跳蚤系列机器人.a .F l e a V 1机器人[33,66];b .F l e a V 2机器人[33];c ~d .F l e a V 3机器人[78];e ~f .水面跳跃机器人[26]F i g .14㊀F l e a Gi n s pi r e d r o b o t s .a .F l e a V 1R o b o t [33,66];b .F l e a V 2R o b o t [33];c ~d .F l e a V 3R o b o t [78];e ~f .R o b o t j u m p i n g onw a t e r [26]基于跳蚤体内的扭矩反转机构[10],N o h 等人提出一种具有非接触式闩锁的仿跳蚤跳跃机器人F l e a V 1[33,66,76],如图14(a)所示.利用三根形状记忆合金弹簧来模拟图10(c)所示的伸肌㊁触发肌和屈34动㊀力㊀学㊀与㊀控㊀制㊀学㊀报2023年第21卷肌,当受拉弹性元件(伸肌)与所连杠杆处于重合位置时能量存在极值,利用负刚度特性可以产生越过重合点后的爆发式运动,实现了快速 突跳(S n a pGt h r o u g h) 的特征[77].基于此原理该团队还设计了其他形式的跳跃机器人F l e a V2㊁F l e aV3[26,33,78],如图14(b)~(d)所示,通过简化S MA的数量来实现更高的跳跃高度(40倍自身高度),并通过结合超疏水喷涂工艺来模拟水黾在水面起跳的现象[图14(e)G(f)],在陆地和水面分别可以实现30和18厘米高的跳跃能力.较轻的机器人也存在一定缺点,如引入电池等额外负载时其跳跃高度将受到严重影响[79];同样,由于结构过于简单,此类机器人在连续跳跃㊁改变方向和高度等方面还具有挑战性,这些问题均会对机器人的实际应用产生限制.采用同样原理的还有Z h a k y p o v等人提出的仿陷阱颚蚁跳跃机器人[57,80],该机器人可实现爬行㊁翻滚㊁垂直跳跃㊁定向跳跃等多运动模式,最高跳跃14厘米,达到自身高度的2.5倍,结构如图15所示.三足的设计不仅增强了机器人的跳跃能力,还帮助机器人实现跳跃方向的选择.此外,通过将电路设计㊁柔顺机构设计与电路板进行集成,完成了机器人的快速㊁轻量化制造.图15㊀仿陷阱颚蚁多模式运动微型机器人[57,80]F i g.15㊀T r a pGj a wGa n tGi n s p i r e dm u l t iGl o c o m o t i o nm i l l i r o b o t[57,80]为了提高机器人的敏捷性,H a l d a n e等人模仿了夜猴㊁青蛙的跳跃机制,提出一种仿夜猴跳跃的机器人S a l t o[25,81].该机器人采用串联驱动器和E MA结合的方式,以增大机械效益在跳跃后与跳跃前的比值为目标,对机器人几何构型和重量分布进行优化,增大了串联弹性元件在跳跃初期能量存储[63].机器人不仅实现了稳定的连续跳跃运动,还具备跳跃高度可调㊁空中姿态调整的能力,可以完成类似于跑酷运动中 蹬墙跳 的高难度动作,这也进一步扩大了自身运动范围,最终使S a l t o实现了夜猴跳跃敏捷度的78%,成为目前垂直跳跃敏捷程度最高的机器人[25].图16㊀S a l t o系列机器人[25,81].a.S a l t o;b.S a l t oG1PF i g.16㊀S a l t o s e r i e s r o b o t s[25,81].a.S a l t o;b.S a l t oG1P在以上非接触式闩锁中,通过与柔顺机构相结合的方式(图14和图15)完成 运动-储能-体化 ,进而实现轻量化设计,同时具有无摩擦㊁释放瞬间冲击小等优点[82G84];由于依靠几何上的临界位置进行释放,该类型机器人往往采用开环的方式控制,同时也带来结构相对复杂的问题.此外,该类型机构在释放阶段的行程占比高于接触式闩锁,限制了释放的瞬时功率,同时也获得更小的冲击.对于可变机械效益机构结合串联弹性元件构成的非接触式闩锁(图16),驱动器直接做功在跳跃运动过程中起重要作用,适用于跳跃周期小的连续型跳跃机器人,也因此更依赖动力学模型来计算机器人的能量释放效果,如对于S a l t o机器人而言,一定范围内提高其驱动器运动加速度可获得更高弹性储能以提高其跳跃高度.表1㊀接触式与非接触式闩锁性能对比T a b l e1㊀P e r f o r m a n c e c o m p a r i s o nb e t w e e n c o n t a c t a n dn o nGc o n t a c t l a t c h e s性能对比接触式闩锁非接触式闩锁释放速度快慢瞬时冲击大小摩擦阻力大小轻量化潜力小大动力学模型简单复杂能量大小控制静态,易动态,难2.3㊀跳跃机器人着陆缓冲功能跳跃机器人在追求较高跳跃目标的同时,着陆44。

Feedback control(反馈控制) 外文翻译

Feedback controlThe class of control problems to examined here is considerable engineering interest. We should consider systems with several input , some known as controls because they may be manipulated and others called external disturbances, which are quite unpredictable, For example , in an industrial furnace we may consider the fuel flow, the ambient temperature, and the loading of material into the furnace to be inputs . Of there , the fuel flow is accessible and can readily be controlled , While the latter two are usually unpredictable disturbances.In such situation , one aspect of the control problem is to determine how the controls should be manipulated so as to counteract the effects of the external disturbances on the state of the system . One possible approach to the solution of this problem is to use a continuous measurement of the disturbances, and from this and the known system equations to determine what the control inputs should be as functions of time to give appropriate control of the system state.A different approach is to construct a feedback system , that is , rather than measure the disturbances directly and then compute their effects on the system from the model or system equations , we compare direct and continuous measurements of the accessible system states with signals representing their “ desired values” to dorm an error signal , and use this signal to produce inputs to the system which will drive the erroras close to zero as possible .By some abuse of terminology , the former approach has come to be known as open loop control , and the tatter as closed-loop control .At first sight , the two approaches might appear to be essentially equivalent . Indeed, one might surmise that an open-loopControl scheme is preferable since it is not necessary to wait until the disturbances have produced an undesirable change in the system state before corrective inputs can be computed and applied.图27.1(a)图27.1(b)However, this advantage is more than outweighed by the disadvantages of open-loop control and the inherent advantages of feedback systems. First, in many cases the implementation of theopen-loop control suggested above would require a very sophisticated (and hence expensive)computing device to determine the inputs require to counteract the predicted disturbance effects. Second, a feedback system turns out to be inherently far less sensitive to the accuracy with which a mathematical model of the system has been determined. Put another way, a properly designed feedback system will still operate satisfactorily even when the internal properties of the system change by significant amounts.Another major advantage of the feedback approach is that by placing a “feedback loop” around a system which initially has quite unsatisfactory performance characteristics, one can in many case construct a system with satisfactory behavior. Consider, for example, a rocket in vertical flight. This is essentially an inverted pendulum, balancing on the gas jet produced by the engine, and inherently unstable(any deviation of the rocket axis from the vertical will cause the rocket to topple over). It can, however, be kept stable in vertical flight by appropriate changes in the direction of the direction of the exhaust jet, which may be achieving these variations in jet direction is to use a feedback strategy in which continuous planes cause a controller to make appropriate adjustments to the direction of the rocket engine. Stabilization of an inherently unstable system could not be achieved in practice by an open-loop control strategy.The mathematical tools required for the analysis and design offeedback system differ according to the structural complexity of the systems to be controlled and according to the objectives the feedback control is meant to achieve.In the simplest situation, one control a single plant state variable, called the output, by means of adjustments to a single plant input. The problem is to design a feedback loop around the system which will ensure that the output changes in response to certain specified time functions or trajectories with an acceptable degree of accuracy. In either case, the transients which are inevitably excited should not b e too “violent” or persist for too long.In a typical situation,, The problem is to design a feedback system around the plant consisting of (a) a device which produces a continuous measurement Ym of the output; (b) a comparator in which this signal is subtracted from a reference input(or set point, or desired output)Yr , representing the desired value of the output, to produce an error signal e; and(c)a controller which uses the error signal e to produce an appropriate input u to the plant. We shall call this configuration a single-loop feedback system, s term which is meant to convey the essential feature that just one of the plant states (the output y)is to be controlled using only one input. The objective of the feedback system is to make the output Y(t) follow its desired value Yr(t) as closely as possible even in the presence of nonzero disturbances d(t). The ability of a system to do so understeady-state condition is known as static accuracy.图27.2Frequently Yr is a constant , in which case we call the feedback system a regulator system. An example is the speed control system of a turbine-generator set in a power station, whose main purpose is to maintain the generator speed as nearly constant as possible. Sometimes Yr is a prescribed non-constant function of time, such as a ramp function;An example of this would be the control system for a radar antenna whose axis is to be kept aligned with the line of sight to an aircraft flying past with constant angular velocity, In this case, we refer to the system as a tracking system..Single-loop feedback systems with the structure of Fig.27.2 are often called servomechanisms because the controller usually includes a device giving considerable power amplification. For instance, in the control system of a hydroelectric turbine-generator set, the signals representing measured speed and desired speed might be voltages at a power level of milliwatts, while several hundred horsepower might be required tooperate the main turbine valve regulating the water flow. This example also illustrate an important engineering constraint in the design of feedback control system. In many applications, the plant and the activating device immediately preceding it operate at comparatively high power levels, and their dynamic properties, if unsatisfactory for some reason, can be changed only at the expense of a feedback system is preferably done in the low-power components of the feedback system, I,e., in the measuring elements and the controller。

Formation input-to-state stability

FORMATION INPUT-TO-STATE STABILITYHerbert G.Tanner and George J.PappasDepartment of Electrical EngineeringUniversity of PennsylvaniaPhiladelphia,PA19102tanner@,pappasg@Abstract:This paper introduces the notion of formation input-to-state stability in order to characterize the internal stability of leader-follower formations,with respect to inputs received by the formation leader.Formation ISS is a weaker form of stability than string stability since it does not require inter-agent communication.It relates group input to internal state of the group through the formation graph adjacency matrix.In this framework,different formation structures can be analyzed and compared in terms of their stability properties and their robustness.Keywords:Formations,graphs,interconnected systems,input-to-state stability.1.INTRODUCTIONFormation control problems have attracted increased attention following the advances on communication and computation technologies that enabled the de-velopment of distributed,multi-agent systems.Direct fields of application include automated highway sys-tems(Varaiya,1993;Swaroop and Hedrick,1996; Yanakiev and Kanellakopoulos,1996),reconnais-sance using wheeled robots(Balch and Arkin,1998), formationflight control(Mesbahi and Hadaegh,2001; Beard et al.,2000)and sattelite clustering(McInnes, 1995).For coordinating the motion of a group of agents,three different interconnection architectures have been con-sidered,namely behavior-based,virtual structure and leader-follower.In behavior based approach(Balch and Arkin,1998;Lager et al.,1994;Yun et al.,1997), several motion premitives are defined for each agent and then the group behavior is generated as a weighted sum of these primary behaviors.Behavior based con-trol schemes are usually hard to analyze formally, although some attempts have been made(Egerstedt, 2000).In leader-follower approaches(Beard et al., 2000;Desai and Kumar,1997;Tabuada et al.,2001;Fierro et al.,2001),one agent is the leader of the formation and all other agents are required to fol-low the leader,directly or indirectly.Virtual structure type formations(Tan and Lewis,1997;Egerstedt and Hu,2001),on the other hand,usually require a cen-tralized control architecture.Balch and Arkin(1998)implement behavior-based schemes on formations of unmanned ground vehicles and test different formation types.Yun et al.(1997) develop elementary behavior strategies for maintain-ing a circular formation using potentialfield meth-ods.Egerstedt and Hu(2001)adopt a virtual struc-ture architecture in which the agents follow a vir-tual leader using a centralized potential-field control scheme.Fierro et al.(2001)develop feedback lineariz-ing controllers for the control of mobile robot forma-tions in which each agent is required to follow one or two leaders.Tabuada et al.(2001)investigate the conditions under which a set of formation constraints can be satisfied given the dynamics of the agents and consider the problem of obtaining a consistent group abstraction for the whole formation.This paper focuses on a different problem:given a leader-follower formation,investigate how the leader input affects the internal stability of the overall for-mation.Stability properties of interconnected systems have been studied within the framework of string stability(Swaroop and Hedrick,1996;Yanakiev and Kanellakopoulos,1996).String stability actually re-quires the attenuation of errors as they propagate in the formation.However,sting stability conditions are generally restrictive and generally require inter-agent communication.It is known,for instance(Yanakiev and Kanellakopoulos,1996)that string stability in au-tonomous operation of an AHS with constant interve-hicle spacing,where each vehicle receives information only with respect to the preceding vehicle,is impos-sible.We therefore believe that a weaker notion of stability of interconnected system that relates group objectives with internal stability would be useful. Our approach is based on the notion of input-to-state stability(Sontag and Wang,1995)and exploits the fact that the cascade interconnection of two input-to-state stable systems is itself input-to-state stable(Khalil, 1996;Krsti´c et al.,1995).This property allows the propagation of input-to-state gains through the for-mation structure and facilitates the calculation of the total group gains that characterize the formation per-formance in terms of stability.Formation ISS is a weaker form of stability than string stability,in the sense that it does not require inter-agent communica-tion and relies entirely on position feedback only(as opposed to both position and velocity feedback)from each leader to its follower.We represent the formation by means of a formation graph(Tabuada et al.,2001). Graphs are especially suited to capture the intercon-nections(Tabuada et al.,2001;Fierro et al.,2001) and informationflow(Fax and Murray,2001)within a formation.The proposed approach provides a means to link the formation leader’s motion or the external input to the internal state and the adjacency matrix of the formation.It establishes a method for comparing stability properties of different formation schemes. The rest of the paper is organized as follows:in sec-tion2the definitions for formation graphs and for-mation input-to-state stability(ISS)are given.Section 3establishes the ISS properties of an leader-follower interconnection and in section4it is shown how these properties can be propagated from one formation graph edge to another to cover the whole formation. Section5provides examples of two stucturally differ-ent basic formation configurations and indicates how interconnection differences affect stability properties. In section6results are summarized and future re-search directions are highlighted.2.FORMATION GRAPHSA formation is being modeled by means of a formation graph.The graph representation of a formation allows a unified way of capturing both the dynamics of each agent and the inter-agent formation specifications.All agent dynamics are supposed to be expressed by lin-ear,time invariant controllable systems.Formation specifications take the form of reference relative posi-tions between the agents,that describe the shape of the formation and assign roles to each agent in terms of the responcibility to preserve the specifications.Such an assignment imposes a leader-follower relationship that leads to a decentralized control architecture.The assignment is expressed as a directed edge on the formation graph(Figure1).Fig.1.An example of a formation graphDefinition2.1.(Formation Graph).A formation graph F=(V,E,D)is a directed graph that consists of:•Afinite set V={v1,...,v l}of l vertices and amapping v i→T R n that assignes to each verticean LTI control system describing the dynamicsof a particular agent:˙x i=A i x i+B i u iwhere x i∈R n is the state of the agent accociatedwith vectice v i,u i∈R m is the agent control inputand A i∈R n×n,B i∈R m×m is a controllable pairof matrices.•A binary relation E⊂V×V representing aleader-follower link between agents,with(v i,v j)∈E whenever the agent associated with vectice v iis to follow the agent of v j.•Afinite set of formation specifications D indexedby the set E,D={d i j}(vi,v j)∈E.For each edge (v i,v j),d i j∈R n,denotes the desired relativedistance that the agent associated with vectice v ihas to maintain from the agent associated withagent v j.Our discussion specializes in acyclic formation graphs. This implies that there can be at least one agent v L that can play the role of a leader(i.e.a vectice with no outgoing arrow).The input of the leader can be used to control the evolution of the whole formation.Thegraph is ordered starting from the leader and following a breadth-first numbering of its vertices.For every edge (v i ,v j )we associate an error vector that expresses the deviation from the specification prescribed for that edge:z i j x j −x i −d i j ∈R ni jThe formation error z is defined as the augmented vector formed by concatenating the error vectors for all edges (v i ,v j )∈E :z z e e ∈E A natural way to represent the connectivity of the graph is by means of the adjacency matrix,A .We will therefore consider the mapping E →R l ×l that assigns to the set E of ordered vertice pairs (v i ,v j )the adjacency matrix A E ∈R l ×l .Our aim is to investigate the stability properties of the formation with respect to the input u L of the formation leader.We thus need to define the kind of stability in terms of which the formation will be analyzed:Definition 2.2.(Formation Input-to-State Stability).A formation is called input-to-state stable iff there isa classfunction βand a class function γsuch that for any initial formation error z (0)and for any bounded inputs of the formation leader u L (·)the evolution of the formation error satisfies:z (t ) ≤β( z (0) ,t )+γsup τ≤tu L(1)By investigating the formation input-to-state stabilitywe establish a relationship between the amplitude of the input of the formation leader and the evolution of the formation errors.This will provide upper bounds for the leaders input in order for the formation shape to be maintained inside some desired specifications.Further,it will allow to characterize and compare formations according to their stability properties.3.EDGE INPUT-TO-STATE STABILITY In the leader-follower configuration,one agent is re-quired to follow another by maintaining a constant distance,x j −x i =d i j .If agent i is required to follow agent j ,then this objective is naturally pursued by applying a follower feedback control law that depends on the relative distance between the agents.For x i =x j −d i j to be an equilibrium of the closed loop control system:˙x i =A i x i +B i u iit should hold that A i (x j −d i j )∈(B i );otherwise the follower cannot be stabilized at that distance from its leader.Suppose that there exists an e i j such that B i e i j =−A i (x j −d i j ).Then the following feedback law can be used for the follower:u i =K i (x j −x i −d i j )+e i jleading to the closed loop dynamics:˙x i =(A i −B i K i )(x i −x j +d i j )Then the error dynamics of the i -j pair of leader-follower becomes:˙z i j =(A i −B i K i )z i j +˙xj which can be written,assuming that agent j followsagent k :˙z i j =(A i −B i K i )z i j +g i j (2)where g i j −(A j −B j K j )z jk .The stability of the follower is thus directly dependenton the matrix (A i −B i K i ),the eigenvalues of which can be arbitrarily chosen,and the interconnection term g i j .The interconnection term can be bounded as follows:g i j ≤λM (A j −B j K j ) z jkwhere λM (·)is the maximum eigenvalue of a given matrix.If K i is chosen so that A i −B i K i is Hurwitz,then the solution of the Lyapunov equation:P i (A i −B i K i )+(A i −B i K i )T P i =−Iprovides a symmetric and positive definite matrix P i and a natural Lyapunov function candidate V i =x T i P i x i for the interconnection dynamics (2)that satisfies:λm (P i ) x i ≤V i ≤λM (P i ) x iwhere λm (·)and λM (·)denote the minimum and max-imum eigenvalue of a given matrix,respectively.Forthe derivative of V i :˙V i ≤− x i 2+2λM (P i )λM (A j −B j K j ) x i z jk≤−(1−θ) x i 2≤0for all x i ≥2λM (P i )λM (A j −B j K j )λm (P i )12λM (P i )t+2(λM (P i ))3(λm (P i ))12λM (P i )t(3)γi (r )=¯γi r (4)where¯βi =λM (P i )2γi =2(λM (P i ))3(λm (P i ))14.FROM EDGE STABILITY TO FORMATIONSTABILITYAn important property of input-to-state stability is that it is preserved in cascade connections.The property allows propagation of ISS properties from one agent to another,all the way up to the formation leader. This procedure will yield the global input gains of the leader and give a measure of the sensitivity of the formation shape with respect to the input applied at the leader.In the previous section it was shown that under the assumption of pure state feedback,a formation graph edge is input-to-state stable.The gain functions for the cascade interconnection˙x1=f1(t,x1,x2,u)˙x2=f2(t,x2,u)are given as:β(r,t)=β1(2β1(r,t2)+γ1(2β2(r,t2λM(P i)t+4¯γi¯βi¯βje−1−θ4λM(P j)t+¯βj e−1−θ{ζz 1=x 1z 2=x 2−x 1−d z 3=x 3−x 2−dthe formation equations can be written as:˙z 1=u ˙z 2=−kz 2−u ˙z 3=−kz 3+kz 2For the 1−2interconnection,a Lyapunov functioncandidate could be:V 2(z 2)12|z 2|2≤V 2(z 2)≤1k θ,θ∈(0,1).Then it follows that,|z 2|≤|z 2(0)|e−√k θ=β2(|z 2(0)|,t )+γ2(sup τ≤t|u |)The ISS input-gain function for agent v 2isγ2=sup τ≤t |u |∈z 23and its time derivative would then be˙V 3(z 3)=−kz 23+kz 3z 2For |z |3>sup τ≤t |z 2(τ)|θThen the formation,as a cascade connection of the subsystems of agents v 2and v 3,is input-to-state stable withγ(sup τ≤t|u |)=6+6k θ+θ2(1−θ)t,γ2=12(1−θ)t,γ3=1k θsup τ≤t|u |It can be shown analytically that the second formation can outperform the first in terms of the magnitude of relative errors with respect to the leader’s velocity.Specifically,if we denote by γs the input-to-state gain of the first interconnection connection and by γp the input-to-state gain of the second interconnection,γsk θ2≥6θ+6k θ+θk θ2=6k +7k θ≥2sup τ≤t |u |6.CONCLUSIONSIn this paper,the notion of formation input-to-state stability has been introduced.This form of stability can be used to characterize the internal state of a formation that has a leader-follower achitecture,and establishes a link between the motion of the leader of the formation or its external input and the shape of the formation.Formation ISS is a weaker form of stability than string stability,in the sense that it does not require inter-agent communication and relies entirely on position feedback only (as opposed to both position and velocity feedback)from each leader to its follower.Moreover,it establishes a link between the formation internal state and the outside world.In the proposed framework,different formation struc-tures can be analyzed and compared in terms of their stability properties.Future work is directed towards investigating the ef-fect of (limited)inter-agent communication on forma-tion stability and consistent ways of group abstrac-tions that are based on the formation ISS properties.Acknowledgment:This research is partially sup-ported by the University of Pennsylvania Research Foundation.7.REFERENCESBalch,T.and R.Arkin(1998).Behavior-based forma-tion control for multirobot systems.IEEE Trans-actions on Robotics and Automation.Beard,R.W.,wton and F.Y.Hadaegh(2000).A coordination architecture for spacecraft forma-tion control.IEEE Transactions on Control Sys-tems Technology.To appear.Desai,J.and V.Kumar(1997).Motion planning of nonholonomic cooperating mobile manipulators.In:IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation.Albuquerque,New Mexico. Egerstedt,Magnus(2000).Behavior based robotics using hybrid automata.In:Hybrid Systems:Com-putation and Control.Lecture Notes in Computer Science.Springer-Verlag.Egerstedt,Magnus and Xiaoming Hu(2001).Forma-tion constrained multi-agent control.In:Proceed-ings of the IEEE Conference on Robotics and Au-tomation.Seoul,Korea.pp.3961–3966.Fax,J.Alexander and Richard M.Murray(2001).Graph laplacians and vehicle formation stabiliza-tion.Technical Report01-007.CDS,California Institute of Technology.Fierro,R.,A.Das,V.Kumar,and J.P.Ostrowski (2001).Hybrid control of formations of robots.In:Proceedings of the IEEE International Con-ference on Robotics and Automation.Seoul,Ko-rea.pp.157–162.Khalil,Hassan,K.(1996).Nonlinear Systems.Pren-tice Hall.Krsti´c,Miroslav,Ioannis Kanellakopoulos and Petar Kokotovi´c(1995).Nonlinear and Adaptive Con-trol Design.John Willey and Sons.Lager,D.,J.Rosenblatt and M.Hebert(1994).A behavior-based systems for off-road navigation.IEEE Transaction on Robotics and Automation 10(6),776–783.McInnes, C.R.(1995).Autonomous ring forma-tion for a planar constellation of satellites.AIAA Journal of Guidance Control and Dynamics 18(5),1215–1217.Mesbahi,M.and F.Hadaegh(2001).Formationflying of multiple spacecraft via graphs,matrix inequal-ities,and switching.AIAA Journal of Guidance, Control and Dynamics24(2),369–377. Sontag,Eduardo D.and Yuan Wang(1995).On char-acterizations of the input-to-state stability prop-erty.Systems&Control Letters(24),351–359. Swaroop,D.and J.K.Hedrick(1996).Sting stability of interconnected systems.IEEE Transactions on Automatic Control41(3),349–357. Tabuada,Paulo,George J.Pappas and Pedro Lima (2001).Feasible formations of multi-agent sys-tems.In:Proceedings of the American Control Conference.Arlington,V A.pp.56–61.Tan,Kar-Han and M.Anthony Lewis(1997).Virtual structures for high-precision cooperative mobile robot control.Autonomous Robots4(4),387–403. Varaiya,P.(1993).Smart cars on smart roads:prob-lems of control.IEEE Transactions on Automatic Control38(2),195–207.Yanakiev,Diana and Ioannis Kanellakopoulos(1996).A simplified framework for string stability anal-ysis in AHS.In:Proceedings of the13th IFAC World Congress.San Francisco,CA.pp.177–182.Yun,Xiaoping,Gokhan Alptekin and Okay Albayrak (1997).Line and circle formations of distributed physical mobile robots.Journal of Robotic Sys-tems14(2),63–76.。

基于事件触发的多智能体分布式编队控制

Feb. 2021Vdl.2& No.22021年2月 第28卷第2期控制工程Control Engineering of China文章编号:1671 -7848(2021 )02-0319-08DOI: 10.14107/ki.kzgc.20190149基于事件触发的多智能体分布式编队控制张志晨,秦正雁,张朋朋,刘腾飞(东北大学流程工业综合自动化国家重点实验室,辽宁沈阳110819)摘 要:研究具有有向通信拓扑的多智能体分布式编队事件触发控制问题,被控对象采用两轮差速轮式机器人。

首先,建立轮式机器人运动学模型,并利用动态反馈线性化方法将 模型转化为线性双积分器模型。

其次,根据通信拓扑关系设计分布式编队控制器。

然后,基于李雅普诺夫稳定性定理,在满足稳定性的前提下设计事件触发器,从而实现分布式编队事件触发控制,并且保证系统不存在Zeno 行为。

最后,通过仿真实验与物理实验验证 了控制昇法的有效性,智能体间通信量显著降低。

关键词:轮式机器人;动态反馈线性化;编队;事件触发中图分类号:TP273 文献标识码:ADistributed Formation Control of Multi-agent Based on Event TriggerZHANG Zhi-chen, QIN Zheng-yan, ZHANG Peng-peng, LIU Teng-fei(State Key Laboratory of Synthetical Automation for Process Industries, Northeastern University, Shenyang 110819 China)Abstract: This paper studies the distributed formation event trigger control problem of multi-agent with adirected communication topology and the agents use the two-wheel differential robot. Firstly, the kinematic model of wheeled robot is developed and transformed into a linear double integrator model through dynamic feedback linearization. Then the distributed formation controller is designed based on communication topology.Based on Lyapunov stability theorem, this paper designs the event trigger on the premise of stability. Thereby, the distributed formation event trigger control is implemented. And it ensures that there is no Zeno behavior in the system. Lastly, the effectiveness of the control algorithm is verified by simulation experiments and physicalexperiments, and communication frequency between agents is significantly reduced.Key words: Wheeled robots; dynamic feedback linearization; formation; event trigger1引言由于单个智能体在执行任务时受到自身能力 的限制,因此多智能体集群控制得到了广泛关注⑴。

15_Kinematic Control

Robotics 1 Kinematic control Prof. Alessandro De LucaRobot motion control⏹ need to “actually” realize a desired robot motion task …⏹ regulation of pose/configuration (constant reference)⏹ trajectory following/tracking (time-varying reference)⏹ ... despite the presence of⏹ external disturbances and/or unmodeled dynamic effects⏹ initial errors (or arising later due to disturbances) w.r.t. desired task⏹ discrete-time implementation, uncertain robot parameters, ...⏹ we use a general control scheme based on⏹ feedback (from robot state measures, to impose asymptotic stability)⏹ feedforward (nominal commands generated in the planning phase)⏹ the error driving the feedback part of the control law can be defined either in Cartesian or in joint space⏹ control action always occurs at the joint level (where actuators drivethe robot), but performance has to be evaluated at the task levelKinematic control of robots⏹ a robot is an electro-mechanical system driven by actuatingtorques produced by the motors⏹ it is possible, however, to consider a kinematic command (mostoften, a velocity) as control input to the system...⏹ ...thanks to the presence of low-level feedback control at therobot joints that allow imposing commanded reference velocities (at least, in the “ideal case”)⏹ these feedback loops are present in industrial robots within a“closed” control architecture, where users can only specifyreference commands of the kinematic type⏹ in this way, performance can be very satisfactory, provided thedesired motion is not too fast and/or does not require largeaccelerationsBode diagrams of sx(s)/u(s) for K/M = 0.1, 1, 10, 100 - 3dBsetting K/M = 10 (bandwidth), we show two possible time responses 1 -7.5 dB attenuation0.6including nonlinear dynamics⏹ single link (a thin rod) of mass m , center of mass at d from joint axis, inertia M (motor + link) at the joint, rotating in a vertical plane (the gravity torque at the joint is configuration dependent) I m +I l +md 2()˙ ˙ q +mg 0d sin q =τM ⏹ fast low-level feedback control loop based on a PI action on the velocity error + an approximate acceleration feedforward ⏹ kinematic control loop based on a P feedback action on the position error + feedforward of the velocity reference ⏹ evaluation of tracking performance for rest-to-rest motion tasks with “increasing dynamics” = higher accelerationsq mg 0 d I mI lτ dynamic model€ g 0=9.81[m /s 2]m =10[kg ]d = 2=0.2[m ]I l =112m 2=0.1333[kg ⋅m 2]I m =0.5333[kg ⋅m 2](=I l +md 2)⇒M =1.0667[kg ⋅m 2]real behavior trajectory generation(a cubic position profile)low-level control =PI velocity feeedback loop+ acceleration feedforwardactuatorrobot dynamicsin T = 0.25 s position tracking position error very good tracking ofreference trajectorymax error ≈ 0.2°bad tracking of reference trajectory max error ≈ 5.5°in T = 0.25 ssaturation! high-level velocity command low-level torque commandsimilar tothe profile ofreferencevelocity!similar to referenceacceleration profile!torque for staticbalance of gravity(provided by theintegral term)“dominated” bygravity torque evolution⏹ in T = 1 sin T = 0.5 sin T = 0.25 sreal position errors increase when reducing too much motion time max error ≈ 0.2°max error ≈ 5.5°torque)Kinematic control of joint motion⌠ ⌡KJ(q)f(q)+-+ + p d. q d. q d J -1(q d )⌠ ⌡q. qpp. reference generator (off-line computation of J -1) feedback from qK > 0 (often diagonal) q(0) q d (0) robot modelenot used for controle = q d - q e = q d - q = q d - (q d + K(q d - q)) = - K e e i → 0 (i=1,…,n) exponentially,∀e(0). . . . .e p = p d - p = J(q d )q d - J(q)(q d + K(q d - q))e p = p d - pq → q d e p → J(q)ee p ≈ - J(q)K J -1(q) e p.. . . ..robot modelKinematic control of Cartesian motion⌠ ⌡K pJ(q)++ + p d. p d ⌠ ⌡q. qpp . reference generator feedback from pK p >0 (often diagonal)p d (0)J -1(q)f(q)q(0) • e p,i → 0 (i=1,…,m) exponentially, ∀e p (0)• needs on-line computation of the inverse (*) J -1(q) • real-time + singularities issuese pe p = p d - pe p = p d - p = p d - J(q) J -1(q) (p d + K p (p d - p)) = - K p e p. . . . .(*) or pseudoinverse if m<nrobot:planar 2Rlengths l1=l2=1Simulink© block diagramdata, desired trajectory, initial state,file) never put “numbers” inside the blocks !Matlab functionsinit.mscript(for task 1.)Simulation data for task 1⏹ straight line path with constant velocity⏹ x d(0)= 0.7 m, y d(0) = 0.3 m; v y,d = 0.5 m/s, for T = 2 s ⏹ large initial error on end-effector position⏹ q(0) = [-45° 90°]T e p(0) = [-0.7 0.3]T m⏹ control gains⏹ K = diag{20,20}⏹ (a)without joint velocity command saturation⏹ (b)with saturation ...⏹ v max,1 = 120°/s, v max,2 = 90°/sstroboscopic view of motion(start and end configurations)p(0)p d(0)errors converge independently and exponentially to 0p(0) p d(0)stroboscopic view of motion (start and end configurations)errors eventually convergeonce out of saturation!. .Simulation data for task 2⏹ circular path with constant velocity⏹ centered at (1.014,0) with radius R = 0.4 m;⏹ v= 2 m/s, performing two rounds T ≈ 2.5 s⏹ zero initial error on Cartesian position (“match”)⏹ q(0) = [-45° 90°]T e p(0) = 0⏹ (a)ideal continuous case (1 kHz), even without feedback ⏹ (b)with sample and hold (ZOH) of T hold = 0.02 s (joint velocity command updated at 50 Hz), but without feedback⏹ (c) as before, but with Cartesian feedback using the gains⏹ K = diag{25,25}circular path: no initial error, continuous control (ideal case)p x, p y actualand desiredcontrol inputs q r1, q r2. .joint variables q 1, q 2final configuration (after two rounds) coincides with initial configurationzero tracking error is kept at all timescircular path: no initial error, ZOH at 50 Hz, no feedbackp x , p y actual and desired control inputs q r1, q r2. .joint variables q 1, q 2a drift occurs along the path due to the “linearization error ” along the path tangentfinal configuration (after two rounds) differs from initial configurationcircular path: no initial error, ZOH at 50 Hz, with feedbackp x , p y actualand desired control inputs q r1, q r2. .joint variables q 1, q 2(almost) the same performance of the continuous case is recovered!!note however that larger P gains will eventually lead to unstable behavior (see: stability problems for discrete-time control systems)3D simulationkinematic control of Cartesian motion of Fanuc 6R (Arc Mate S-5) robotsimulation and visualization in MatlabvideoKinematic control of KUKA LWRkinematic control of Cartesian motion with redundancy exploitationvelocity vs. acceleration levelvideo。

Motion control of robot manipulators

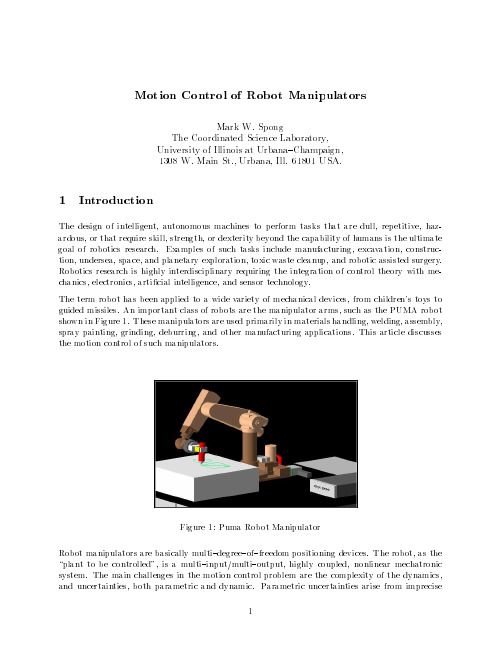

Figure 1: Puma Robot Manipulator Robot manipulators are basically multi{degree{of{freedom positioning devices. The robot, as the \plant to be controlled", is a multi{input/multi{output, highly coupled, nonlinear mechatronic system. The main challenges in the motion control problem are the complexity of the dynamics, and uncertainties, both parametric and dynamic. Parametric uncertainties arise from imprecise 1

Motion Control of Robot Manipulators

Mark W. Spong The Coordinated Science Laboratory, University of Illinois at Urbana{Champaign, 1308 W. Main St., Urbana, Ill. 61801 USA.

1.2 Kinematics

Kinematics refers to the geometric relationship between the motion of the robot in Joint Space and the motion of the end{e ector in Task Space without consideration of the forces that produce the motion. The Forward Kinematics Problem is to determine the mapping

机械力学中英文对照