Fidelity of Quantum Teleportation through Noisy Channels

量子计算机杂谈

美国洛克希德•马丁公司对 量子计算机研究的态度2014年03月21日11:27

中国新闻网

中新网3月21日电 据中国国防科技信息网报道,作为世界上最大的国防承包商,美国洛克希 德•马丁公司正在不断加大对量子计算研究的投入力度,尽管这一技术离军事应用可能还有数 十年的差距。 洛克希德公司最近宣布将与马里兰大学合作,共同在该校位于华盛顿特区附近的大学园校区 设立量子工程中心。量子计算机是利用量子比特而不是二进制数字来存储信息,因此在理论 上可以更快地解决复杂计算问题。 洛克希德公司高级副总裁兼首席技术官(CTO)雷•约翰逊在一场新闻发布会上透露,“经典 计算只能将我们带到这里,在未来,关键系统都将变得十分复杂,即使利用最强大的超级计 算机去处理也难以奏效,要么耗时太长,要么花费太高。我们相信,下一次计算革命将源自 应用量子科学,这是一门连接物理、信息科学和工程的学科。”

ENIAC Electronic Numerical Integrator And Computer

1947年,1958年

1947年,贝尔实验室的肖克利、布拉顿、 巴丁发明了世界上第一只晶体管

威廉·肖克利 William Shockley 沃尔特·布拉顿 John Bardeen 约翰·巴丁 Walter Brattain

图灵机模型、状态转换、计算案例

现代计算机的体系结构

冯•诺伊曼1945年提出将程序指令和数据存储器合二为一的计算机设计概念 奠定了现代计算机的体系结构。 (von Neumann architecture)

约翰•冯•诺伊曼(1903-1957),是出生于匈牙利的美国籍犹太人数学家,现代计算机创始人 之一。他在计算机科学、经济、物理学中的量子力学及几乎所有数学领域都作过重大贡献。 1994年被授予美国国家基础科学奖。(数学,量子力学,计算机科学,经济学) 大事记: 1926年,冯•诺伊曼以22岁的年龄获得了布达佩斯大学数学博士学位,相继在柏林大学和汉堡 大学担任数学讲师。 1930年,冯•诺伊曼接受了普林斯顿大学客座教授的职位。 1931年,冯•诺伊曼成为该校终身教授。 1933年转入普林斯顿高等研究院,与爱因斯坦等人成为该院最初的四位教授之一。这一年, 他部分解决了希尔伯特第5个问题,证明了局部欧几里得紧群是李群。 1937年成为美国公民。 1938年获颁博修奖。 1943年,冯·诺伊曼应美国国防部之邀,以顾问身份参与研制原子弹的“曼哈顿计划”。 1944年冯·诺伊曼与莫根施特恩(Morgensten)合著的经典著作《对策论与经济行为》出版, 他被称为「博弈论之父」。博弈论被认为是20世纪经济学最伟大的成果之一,后来有两个奖 项以冯·诺伊曼为名:INFORMS的冯·诺伊曼理论奖及IEEE的IEEE冯·诺伊曼奖。 1944年8月转行到莫尔学院,亲自参与“ENIAC”电子计算机的研制工作。 1945年6月,冯·诺伊曼與戈德斯坦、勃克斯等人联名发表了一篇长达101页的报告,即计算机 史上的里程碑式的文献「101頁报告」,又称为“EDVAC方案”(离散变量电子计算机),明 确建议了现代电子计算机的逻辑结构应当包含的基本组件,专业人士称这个“冯·诺伊曼结 构”,是研制现代电子计算机的基础;二战结束后,美国海军部拨经费给冯·诺依曼,资助他 去设计一台能够准确预报天气的计算机。 1948年,美国国防部与空军联合成立了一个智库——“兰德公司”,宗旨为“思考那些不可思 议的问题”,冯·诺伊曼出任“兰德公司”的顾问。当年关注的焦点是核子战争发生的可能性, 以及应对策略;冯·诺伊曼曾向美国政治、军事与经济领域的高层人士提供了许多建议。

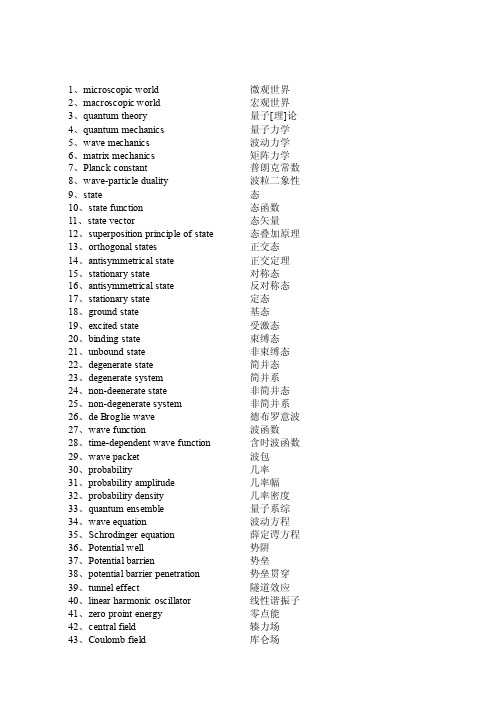

量子力学英语词汇

1、microscopic world 微观世界2、macroscopic world 宏观世界3、quantum theory 量子[理]论4、quantum mechanics 量子力学5、wave mechanics 波动力学6、matrix mechanics 矩阵力学7、Planck constant 普朗克常数8、wave-particle duality 波粒二象性9、state 态10、state function 态函数11、state vector 态矢量12、superposition principle of state 态叠加原理13、orthogonal states 正交态14、antisymmetrical state 正交定理15、stationary state 对称态16、antisymmetrical state 反对称态17、stationary state 定态18、ground state 基态19、excited state 受激态20、binding state 束缚态21、unbound state 非束缚态22、degenerate state 简并态23、degenerate system 简并系24、non-deenerate state 非简并态25、non-degenerate system 非简并系26、de Broglie wave 德布罗意波27、wave function 波函数28、time-dependent wave function 含时波函数29、wave packet 波包30、probability 几率31、probability amplitude 几率幅32、probability density 几率密度33、quantum ensemble 量子系综34、wave equation 波动方程35、Schrodinger equation 薛定谔方程36、Potential well 势阱37、Potential barrien 势垒38、potential barrier penetration 势垒贯穿39、tunnel effect 隧道效应40、linear harmonic oscillator 线性谐振子41、zero proint energy 零点能42、central field 辏力场43、Coulomb field 库仑场44、δ-function δ-函数45、operator 算符46、commuting operators 对易算符47、anticommuting operators 反对易算符48、complex conjugate operator 复共轭算符49、Hermitian conjugate operator 厄米共轭算符50、Hermitian operator 厄米算符51、momentum operator 动量算符52、energy operator 能量算符53、Hamiltonian operator 哈密顿算符54、angular momentum operator 角动量算符55、spin operator 自旋算符56、eigen value 本征值57、secular equation 久期方程58、observable 可观察量59、orthogonality 正交性60、completeness 完全性61、closure property 封闭性62、normalization 归一化63、orthonormalized functions 正交归一化函数64、quantum number 量子数65、principal quantum number 主量子数66、radial quantum number 径向量子数67、angular quantum number 角量子数68、magnetic quantum number 磁量子数69、uncertainty relation 测不准关系70、principle of complementarity 并协原理71、quantum Poisson bracket 量子泊松括号72、representation 表象73、coordinate representation 坐标表象74、momentum representation 动量表象75、energy representation 能量表象76、Schrodinger representation 薛定谔表象77、Heisenberg representation 海森伯表象78、interaction representation 相互作用表象79、occupation number representation 粒子数表象80、Dirac symbol 狄拉克符号81、ket vector 右矢量82、bra vector 左矢量83、basis vector 基矢量84、basis ket 基右矢85、basis bra 基左矢86、orthogonal kets 正交右矢87、orthogonal bras 正交左矢88、symmetrical kets 对称右矢89、antisymmetrical kets 反对称右矢90、Hilbert space 希耳伯空间91、perturbation theory 微扰理论92、stationary perturbation theory 定态微扰论93、time-dependent perturbation theory 含时微扰论94、Wentzel-Kramers-Brillouin method W. K. B.近似法95、elastic scattering 弹性散射96、inelastic scattering 非弹性散射97、scattering cross-section 散射截面98、partial wave method 分波法99、Born approximation 玻恩近似法100、centre-of-mass coordinates 质心坐标系101、laboratory coordinates 实验室坐标系102、transition 跃迁103、dipole transition 偶极子跃迁104、selection rule 选择定则105、spin 自旋106、electron spin 电子自旋107、spin quantum number 自旋量子数108、spin wave function 自旋波函数109、coupling 耦合110、vector-coupling coefficient 矢量耦合系数111、many-particle system 多子体系112、exchange forece 交换力113、exchange energy 交换能114、Heitler-London approximation 海特勒-伦敦近似法115、Hartree-Fock equation 哈特里-福克方程116、self-consistent field 自洽场117、Thomas-Fermi equation 托马斯-费米方程118、second quantization 二次量子化119、identical particles 全同粒子120、Pauli matrices 泡利矩阵121、Pauli equation 泡利方程122、Pauli’s exclusion principle泡利不相容原理123、Relativistic wave equation 相对论性波动方程124、Klein-Gordon equation 克莱因-戈登方程125、Dirac equation 狄拉克方程126、Dirac hole theory 狄拉克空穴理论127、negative energy state 负能态128、negative probability 负几率129、microscopic causality 微观因果性本征矢量eigenvector本征态eigenstate本征值eigenvalue本征值方程eigenvalue equation本征子空间eigensubspace (可以理解为本征矢空间)变分法variatinial method标量scalar算符operator表象representation表象变换transformation of representation表象理论theory of representation波函数wave function波恩近似Born approximation玻色子boson费米子fermion不确定关系uncertainty relation狄拉克方程Dirac equation狄拉克记号Dirac symbol定态stationary state定态微扰法time-independent perturbation定态薛定谔方程time-independent Schro(此处上面有两点)dinger equation 动量表象momentum representation角动量表象angular mommentum representation占有数表象occupation number representation坐标(位置)表象position representation角动量算符angular mommentum operator角动量耦合coupling of angular mommentum对称性symmetry对易关系commutator厄米算符hermitian operator厄米多项式Hermite polynomial分量component光的发射emission of light光的吸收absorption of light受激发射excited emission自发发射spontaneous emission轨道角动量orbital angular momentum自旋角动量spin angular momentum轨道磁矩orbital magnetic moment归一化normalization哈密顿hamiltonion黑体辐射black body radiation康普顿散射Compton scattering基矢basis vector基态ground state基右矢basis ket ‘右矢’ket基左矢basis bra简并度degenerancy精细结构fine structure径向方程radial equation久期方程secular equation量子化quantization矩阵matrix模module模方square of module内积inner product逆算符inverse operator欧拉角Eular angles泡利矩阵Pauli matrix平均值expectation value (期望值)泡利不相容原理Pauli exclusion principle氢原子hydrogen atom球鞋函数spherical harmonics全同粒子identical particles塞曼效应Zeeman effect上升下降算符raising and lowering operator 消灭算符destruction operator产生算符creation operator矢量空间vector space守恒定律conservation law守恒量conservation quantity投影projection投影算符projection operator微扰法pertubation method希尔伯特空间Hilbert space线性算符linear operator线性无关linear independence谐振子harmonic oscillator选择定则selection rule幺正变换unitary transformation幺正算符unitary operator宇称parity跃迁transition运动方程equation of motion正交归一性orthonormalization正交性orthogonality转动rotation自旋磁矩spin magnetic monent(以上是量子力学中的主要英语词汇,有些未涉及到的可以自由组合。

quantum transportation

量子通信应用

量子密钥分发:将量子通信原理仅用于用于发送密匙而不用于数据传 输。

Quantum Teleportation

In the quantum formalism, the result of a spin measurement on one of the particles is a collapse into a state in which each particle has a definite spin (either up or down) along the axis of measurement. The outcome is taken to be random, with each possibility having a probability of 50%. However, if both spins are measured along the same axis, they are found to be anti-correlated.

量子通信

Quantum Teleportation

量子通信

量子通信是指利用量子纠缠效应进行信息传递的一种新型的通讯方式, 是近二十年发展起来的新型交叉学科,是量子论和信息论相结合的新 的研究领域。

Quantum teleportation is a process by which quantum information (e.g. the exact state of an atom or photon) can be transmitted (exactly, in principle) from one location to another, with the help of classical communication and previously shared quantum entanglement between the sending and receiving location.

量子计算机常见术语简介(1)

量子计算机常见术语简介(1)胡经国量子计算机所涉及的科学技术知识极其广博而深奥。

而且,其中有关的科技术语众多而费解。

这给业外读者学习和了解量子计算机科技知识带来了相当大的困难。

本文拟根据有关资料对量子计算机常见术语进行简要介绍,供读者进一步了解和研究量子计算机参考。

1、量子计算机⑴、定义量子计算机(Quantum Computer)是一种全新的基于量子理论的计算机,是一种遵循量子力学规律进行高速数学和逻辑运算、存储及处理量子信息的物理装置。

当某种装置处理和计算的是量子信息、运行的是量子算法时,这种装置就是量子计算机。

量子计算机的概念源于对可逆计算机的研究。

研究可逆计算机的目的是为了解决计算机的能耗问题。

量子计算机是一个量子力学系统;量子计算过程就是这个系统量子态演化过程。

量子计算机是一种使用量子逻辑进行通用计算的装置。

1985年,多伊奇(D.Deutsch)提出了量子计算机的模型——通用量子计算机(或量子图灵机)。

任意一种量子算法均可以利用通用量子计算机实现。

量子计算机是由许多量子比特(Qubit ,二态量子系统)组成的物理系统。

目前,量子计算机使用的是如原子、离子、光子等粒子或物理系统。

不同类型的量子计算机使用的是不同的粒子。

例如,中国的“九章量子计算机”原型机使用的是光子。

⑵、基本储存单元量子计算机不同于经典计算机。

经典计算机计算和处理的是经典信息。

经典信息的基本储存单元是经典比特(Bit),用经典状态0和1(如电压的高、低)表示。

量子计算机计算和处理的是量子信息。

量子信息的基本储存单元是量子比特(Qubit)。

每个量子比特具有两个完全可以区分的极化状态(量子态)|0〉和|1〉。

它们分别对应于经典状态的0和1。

量子比特和经典比特的区别在于:量子比特既可以处于|0〉态,也可以处于|1〉态;可以处于既不是|0〉态又不是|1〉态,而是处于|0〉和|1〉的叠加态,即量子叠加态。

量子叠加态用a|0〉+b|1〉表示;其中的系数a和b刻画了量子比特的具体状态。

滤波器的英文介绍

The basic principle of spread spectrum communicationSo-called spread spectrum communication, but simply indicates as follows: The "wide frequency communication is one intelligence transmission mode, its signal cabin holds the bandwidth far is bigger than passes on the information essentially the minimum bandwidth ; The frequency band expansion is completes through an independent code sequence, implements with the code and the modulation method, with passes on the information data to have nothing to do with; Uses the similar code in the receiving end to carry on the correlation synchronization receive, demodulation and recover passes on information data ".The wide frequency communication essential feature, is transmits the minimum bandwidth which the signal cabin takes (W) far to be bigger than (B) which primary information itself actual needs, its ratio is called the processing gain (Gp): In brief, we use the spread spectrum the wide band signal to transmit the information, is for enhance the communication the antijamming ability, namely under strong interferes the condition guaranteed the reliable security communicates. This is the spread spectrum communication basic thought and the theory basis.First, the main merit of wide frequency communications system* It’s easy to duplicate the frequency of use, raise the wireless frequency spectrum use factor* Strong anti-jamming, the error rate is low. Wide frequency communication when spatial transmission holds the bandwidth relative is wider, but the receiving end uses the correlation detection the means to solve expands, makes the useful wide band information signal to recover the narrow band signal, but non- needs the signal to expand the wide band signal, then extracts the useful signal through the narrow band filtering technology. This auspicious, regarding each kind of unwanted signal, because it in receives the end the non- relevance, after demodulation in the narrow band signal only has the very weak ingredient, the signal to noise ratio very high, therefore the anti-jamming is strong.* Good Privacy, is very small to each kind of narrow band communications system disturbance. Because the wide frequency signal expanded in the relative wider frequency band, in unit frequency band power very small, the signal is neglected in the noise, generally not easily was detected, but wants further to examine the signal the parameter (for example pseudo-random code sequence) difficultly, therefore said its privacy is good.* May implement a code minute site. The wide frequency communication enhanced the resistance to interference, the price takes the band width. But if many usersaltogether use this wideband, then may enhance the frequency band the use factor. Because has the wide frequency code sequence in the wide frequency communication the wide frequency modulation, fully uses between each kind of different code wide frequency code sequence the fine autocorrelation identity and the mutual correlation identity, carries on the solution in the receiving end using the correlation detection technology to expand, then in allocate may differentiate the different user for the different user code situation in the signal, extracts the useful signal. Like this many pair of users may simultaneously converse on the telephone in this frequency band but mutually does not disturb.* Anti- multi- diameters disturbance. In the wireless communication, since long ago, the multi- diameters disturbance throughout is one of questions which solves with difficulty. Uses the wide frequency code in the wide frequency communication the autocorrelation identity, extracts and separates the strongest useful signal in the receiving end from the multi- diameters signal, or the identical code sequence profile which comes many paths adds together the synthesis, all may the anti- multi- diameters disturbance function.Be different according to the spread spectrum mode, the existing wide frequency communications system may divide into following several kinds:* Direct sequence spread spectrum. The direct sequence spread spectrum (Direct Sequence Spread Spectrum) the work mode, is called straight expands (DSSS) the mode. The so-called direct sequence spread spectrum, is directly use the high rate wide frequency code sequence to expand the signal in the start the frequency spectrum. But in the receiving end, carries on the solution with the same wide frequency code sequence to expand, returns to original state the primitive information the stretch wide frequency signal.* Frequency-hopping (Frequency Hopping). Moreover one expansion signal frequency spectrum mode is called the frequency-hopping (FH - Frequency Hopping). The so-called frequency-hopping, compared with the accurate meaning is: Carries on the selection with the certain code sequence the multi- frequencies frequency-shift keying. In other words, carries on the frequency-shift keying modulation with the wide frequency code sequence, causes the carrier frequency unceasingly to jump, therefore is called the frequency-hopping.* Jumps when (Time Hopping). Is similar, jumps when (TH – Time Hopping) with the frequency-hopping is causes the transmitting message to jump in the time axis. First divides into the time axis many o'clock pieces. In does an in which time piece transmitting message carry on the check by the wide frequency code sequence. May jumps when the understanding be: Carries on selection with the certain code sequence many when pieces when moves the key modulation. Because used has very been narrow the very many time piece to transmit the signal, relatively mentioned, thesignal frequency spectrum also stretched.* Wide band linear frequency modulation (Chirp Modulation). The wide band linear frequency modulation work mode, is called the Chirp mode. If emanates radio frequency pulse signal in a cycle, its carrier spectrum frequency do change, then is called the linear frequency modulation.Second, direct sequence spread spectrum systemCompares with the general simulation or the digital communication system, the direct sequence spread spectrum in the information recognition and the demodulation, the radio frequency on frequency conversion and under the frequency conversion situation basic is same. Straight expands the communications system the main characteristic to lie in straight expands the signal the production, namely the wide frequency modulation and straight expands the signal the receive, namely the related solution expands.The wide frequency modulation is carries on the modulation with high rate PN code pulse sequence thus the expansion signal frequency spectrum. Usually uses the modulation mode is BPSK, the input signal and the PN code modulates in the balanced modulator outputs the stretch the wide frequency signal.Straight expands the system to carry on the modulation in the start with the PN code to expand the signal frequency spectrum. Is receiving the end generally to use the correlation detection or the matched filtering method solves expands. The so-called correlation detection, a simple metaphor is compares with the picture looks for the person. If wants to search the person in group of people which some is not acquainted with one another, the simplest valid method is in the hand has a Zhang person's picture, then with the picture one by one contrast, gets down like this, naturally can find some person. Same principle, when you want to examine the useful signal which needs, the valid method is in local produces a same signal, then with it with the signal contrast which receives, as desired similarity. In other words, is with the same signal which local produces with the signal which receives carries on the correlation operation, correlation function is biggest on the useful signal which most possibly is wants.The connected demodulation to be no doubt very good in the performance, but it needs to have the local PN code in the receiving end. This point sometimes brings many is not convenient. For example, the solution local signal and the receive signal synchronized question very is troublesome, but also cannot achieve real-time examines the useful signal. Because the matched filtering and the correlationdetection function in essentially is same, we may use the matched filter to demodulate t the straight -expand signal.The so-called matched filter, is a filter which matches with the signal, it can examines in the many kinds of signals or the disturbance with it match signal. This similarly is one kind of "looks for person" with the photograph the method. As for the video frequency rectangle pulse sequence that, the passive matched filter is on the tap delay line adds on the adder-accumulator.Third, frequency-hopping systemWe usually contact the wireless communications system all is the carrier frequency fixed communications system, like mobile phone and so on, therefore also is called as decides the frequency communication. This kind decides the frequency communications system, once will receive the disturbance on to cause the communication drop in quality, will be serious when will even cause the communication interrupt.Moreover in the enemy I in the duplex communication resistance, the enemy side attempt detects our communication frequency, in order to transmits to the interception the information content, or detected our telegraph is at position. Decides the frequency communications system to be easy to expose the goal also easy to intercept, by now, used the frequency-hopping communications quite to be covert with difficulty is also intercepted.Therefore, the frequency-hopping communications has the antijamming, the anti- interception ability, and can do frequency spectrum resource sharing. Therefore the frequency-hopping communications has displayed the huge superiority in the current modernized electronic warfare. Moreover, the frequency-hopping communications also applies in the civil communication by between the anti- decline, the anti- multi- diameters, the anti- network disturbs and raises the frequency spectrum use factor.In order to does not let the enemy side know we communicate the use frequency, needs frequently to change the carrier frequency, namely carries on the jump to the carrier frequency, in the frequency-hopping communications the carrier frequency change rule, is called the frequency-hopping design.The frequency-hopping signal receive, its process with decides the frequency to be similar. In order to after guarantee the mixing obtains the intermediate frequency signal, the requirement frequency synthesizer output frequency must outdo an intermediate frequency compared to the external signal. Because the external signal-carrier frequency is the jump, then requires the frequency which the local frequency synthesizer outputs also along with the external signal jump rule to jump, like this can obtain a fixed center quite signal through the mixing.The frequency-hopping is the frequency-hopping system key component, but frequency-hopping synchronization is the frequency-hopping system core technology. Frequency-hopping system synchronization including following several contents:* Receives the frequency-hopping design which the end and the start produces to be same, namely has the same frequency-hopping rule.* Receives, the start jump frequency should guarantee produces the fixed intermediate frequency signal in the receiving end, namely the jump carrier frequency with receives this locality which the end produces to jump the frequency to differ an intermediate frequency.* Frequency jump beginning and end time in time synchronization, namely synchronized jump, or phase coincidence.* When transmission numerical information, but also should achieve the frame synchronization and position synchronization.Fourth, PN codeThe PN code also calls the pseudo-random sequence. It has the approximate random sequence (noise) nature, but also can (cycle) produce according to the certain rule with the copying sequence. Because the random sequence is only can produce but cannot copy, therefore called it is the "pseudo" random sequence. The commonly used pseudo-random sequence has the m sequence, the M sequence and R –the S sequence.The msequencer from the belt feedback m level shift register framing,feeds back from certain levels after mold two Canada to the first level. It produces the sequence greatest length (cycle) is the 2n – 1 bit, altogether has 2m to plant the different state, one kind is entire "0" state. Only has when the feedback logic satisfies some kind of condition, the shift register outputs the sequence length is the 2n - 1 bit, achieves the greatest length. Otherwise produces the sequence could not achieve 2n - 1 bit of such is long. Therefore also is called the m sequence the greatest length linearity shift register sequence. Also is called the biggest shift register sequence.If in the feedback logic operation includes the multiplication operation or other logic operations, then is called as the nonlinear feedback logic. The sequencer frame which by the nonlinear feedback logic and the shift register can have the greatest length sequence, is called the greatest length non-linearity shift register sequence, or is called the M sequence, the M sequence greatest length is 2n.。

量子力学英语词汇

1、microscopic world 微观世界2、macroscopic world 宏观世界3、quantum theory 量子[理]论4、quantum mechanics 量子力学5、wave mechanics 波动力学6、matrix mechanics 矩阵力学7、Planck constant 普朗克常数8、wave-particle duality 波粒二象性9、state 态10、state function 态函数11、state vector 态矢量12、superposition principle of state 态叠加原理13、orthogonal states 正交态14、antisymmetrical state 正交定理15、stationary state 对称态16、antisymmetrical state 反对称态17、stationary state 定态18、ground state 基态19、excited state 受激态20、binding state 束缚态21、unbound state 非束缚态22、degenerate state 简并态23、degenerate system 简并系24、non-deenerate state 非简并态25、non-degenerate system 非简并系26、de Broglie wave 德布罗意波27、wave function 波函数28、time-dependent wave function 含时波函数29、wave packet 波包30、probability 几率31、probability amplitude 几率幅32、probability density 几率密度33、quantum ensemble 量子系综34、wave equation 波动方程35、Schrodinger equation 薛定谔方程36、Potential well 势阱37、Potential barrien 势垒38、potential barrier penetration 势垒贯穿39、tunnel effect 隧道效应40、linear harmonic oscillator线性谐振子41、zero proint energy 零点能42、central field 辏力场43、Coulomb field 库仑场44、δ-function δ-函数45、operator 算符46、commuting operators 对易算符47、anticommuting operators 反对易算符48、complex conjugate operator 复共轭算符49、Hermitian conjugate operator 厄米共轭算符50、Hermitian operator 厄米算符51、momentum operator 动量算符52、energy operator 能量算符53、Hamiltonian operator 哈密顿算符54、angular momentum operator 角动量算符55、spin operator 自旋算符56、eigen value 本征值57、secular equation 久期方程58、observable 可观察量59、orthogonality 正交性60、completeness 完全性61、closure property 封闭性62、normalization 归一化63、orthonormalized functions 正交归一化函数64、quantum number 量子数65、principal quantum number 主量子数66、radial quantum number 径向量子数67、angular quantum number 角量子数68、magnetic quantum number 磁量子数69、uncertainty relation 测不准关系70、principle of complementarity 并协原理71、quantum Poisson bracket 量子泊松括号72、representation 表象73、coordinate representation 坐标表象74、momentum representation 动量表象75、energy representation 能量表象76、Schrodinger representation 薛定谔表象77、Heisenberg representation 海森伯表象78、interaction representation 相互作用表象79、occupation number representation 粒子数表象80、Dirac symbol 狄拉克符号81、ket vector 右矢量82、bra vector 左矢量83、basis vector 基矢量84、basis ket 基右矢85、basis bra 基左矢86、orthogonal kets 正交右矢87、orthogonal bras 正交左矢88、symmetrical kets 对称右矢89、antisymmetrical kets 反对称右矢90、Hilbert space 希耳伯空间91、perturbation theory 微扰理论92、stationary perturbation theory 定态微扰论93、time-dependent perturbation theory 含时微扰论94、Wentzel-Kramers-Brillouin method W. K. B.近似法95、elastic scattering 弹性散射96、inelastic scattering 非弹性散射97、scattering cross-section 散射截面98、partial wave method 分波法99、Born approximation 玻恩近似法100、centre-of-mass coordinates 质心坐标系101、laboratory coordinates 实验室坐标系102、transition 跃迁103、dipole transition 偶极子跃迁104、selection rule 选择定则105、spin 自旋106、electron spin 电子自旋107、spin quantum number 自旋量子数108、spin wave function 自旋波函数109、coupling 耦合110、vector-coupling coefficient 矢量耦合系数111、many-partic le system 多子体系112、exchange forece 交换力113、exchange energy 交换能114、Heitler-London approximation 海特勒-伦敦近似法115、Hartree-Fock equation 哈特里-福克方程116、self-consistent field 自洽场117、Thomas-Fermi equation 托马斯-费米方程118、second quantization 二次量子化119、identical particles全同粒子120、Pauli matrices 泡利矩阵121、Pauli equation 泡利方程122、Pauli’s exclusion principle泡利不相容原理123、Relativistic wave equation 相对论性波动方程124、Klein-Gordon equation 克莱因-戈登方程125、Dirac equation 狄拉克方程126、Dirac hole theory 狄拉克空穴理论127、negative energy state 负能态128、negative probability 负几率129、microscopic causality 微观因果性本征矢量eigenvector本征态eigenstate本征值eigenvalue本征值方程eigenvalue equation本征子空间eigensubspace (可以理解为本征矢空间)变分法variatinial method标量scalar算符operator表象representation表象变换transformation of representation表象理论theory of representation波函数wave function波恩近似Born approximation玻色子boson费米子fermion不确定关系uncertainty relation狄拉克方程Dirac equation狄拉克记号Dirac symbol定态stationary state定态微扰法time-independent perturbation定态薛定谔方程time-independent Schro(此处上面有两点)dinger equation 动量表象momentum representation角动量表象angular mommentum representation占有数表象occupation number representation坐标(位置)表象position representation角动量算符angular mommentum operator角动量耦合coupling of angular mommentum对称性symmetry对易关系commutator厄米算符hermitian operator厄米多项式Hermite polynomial分量component光的发射emission of light光的吸收absorption of light受激发射excited emission自发发射spontaneous emission轨道角动量orbital angular momentum自旋角动量spin angular momentum轨道磁矩orbital magnetic moment归一化normalization哈密顿hamiltonion黑体辐射black body radiation康普顿散射Compton scattering基矢basis vector基态ground state基右矢basis ket ‘右矢’ket基左矢basis bra简并度degenerancy精细结构fine structure径向方程radial equation久期方程secular equation量子化quantization矩阵matrix模module模方square of module内积inner product逆算符inverse operator欧拉角Eular angles泡利矩阵Pauli matrix平均值expectation value (期望值)泡利不相容原理Pauli exclusion principle氢原子hydrogen atom球鞋函数spherical harmonics全同粒子identical partic les塞曼效应Zeeman effect上升下降算符raising and lowering operator 消灭算符destruction operator产生算符creation operator矢量空间vector space守恒定律conservation law守恒量conservation quantity投影projection投影算符projection operator微扰法pertubation method希尔伯特空间Hilbert space线性算符linear operator线性无关linear independence谐振子harmonic oscillator选择定则selection rule幺正变换unitary transformation幺正算符unitary operator宇称parity跃迁transition运动方程equation of motion正交归一性orthonormalization正交性orthogonality转动rotation自旋磁矩spin magnetic monent(以上是量子力学中的主要英语词汇,有些未涉及到的可以自由组合。

Importance of quantum interference in molecular-scale devices

Importance of quantum interferencein molecular-scale devicesKamil Walczak 1Institute of Physics, Adam Mickiewicz UniversityUmultowska 85, 61-614 Poznań, PolandElectron transport is theoretically investigated in a molecular device made of anthracene molecule attached to the electrodes by thiol end groups in two different configurations (para and meta, respectively). Molecular system is described by a simple Hückel-like model (with non-orthogonal basis set of atomic orbitals), while the coupling to the electrodes is treated through the use of Newns-Anderson chemisorption theory (constant density of states within energy bandwidth). Transport characteristics (current-voltage and conductance-voltage) are calculated from the transmission function in the standard Landauer formulation. The essential question of quantum interference is discussed in detail. The results have shown a striking variation of transport properties of the device depending on the character of molecular binding to the electrodes.Key words: molecular device, quantum interference, electronic transport, molecular electronicsPACS numbers: 85.65.+h , 73.23.-bI. IntroductionMolecular junctions are promising candidates as future electronic devices because of their small size and self-assembly features. Such junctions are usually composed of two metallic electrodes (source and drain) joined by individual molecule (bridge). The charge is transferred under the bias voltage and current-voltage (I-V) characteristics are measured experimentally [1]. In general, transport properties of such structures are dominated by some effects of quantum origin, such as: tunneling, quantization of molecular energy levels and discreteness of electron charge and spin. However, recently it was pointed out that also quantum interference effects can lead to substantial variation in the conductance of molecule-scale devices [2-9].The main purpose of this work is to show some theoretical aspects of interference phenomena in anthracene molecule connecting two identical electrodes by thiol (–SH) end groups (see fig.1). These end groups (or more precisely sulfur terminal atoms, since hydrogen atom seems to be lost in the chemisorption process) ensure readily attachment to metal surfaces [10]. It is shown that the molecule acts not only as a scattering impurity between two reservoirs of electrons (electrodes), but simultaneously as an “electronic interferometer”. Interference itself reveals the wave nature of the electrons passing from the source to drain through the molecule. Here the variation of interference conditions is achieved by changing the connection between anthracene molecule and electrodes.Fig.1 A schematic model of analyzed samples.II. Theoretical treatmentMolecular device is defined as anthracene molecule joined to two metallic surfaces with the help of thiol end groups in two different configurations – para (A) and meta (B), respectively. In both cases we have different interference conditions and so we expect to observe changes in transport characteristics. Problem of electronic conduction between two continuum reservoirs of states via a molecular bridge with discrete energy levels can be solved within transfer matrix technique of scattering theory [11,12]. The current flowing through the device is obtained from the transmission function T through the integration procedure [12]: []dE )E (f )E (f )E (T h e 2)V (I D S m m ---=ò+¥¥-, (1)where: f denotes Fermi distribution function for room temperature (293 K) with chemical potentials 2/eV E F D /S ±=m referred to the source and drain, respectively. In this type of non-self-consistent calculations, one must postulate voltage distribution along the molecular bridge. For the sake of simplicity we assume that voltage drop is limited to the electrodes only [13], shifting their Fermi level located in the middle of the HOMO-LUMO gap [14]. However, other choices of the voltage distribution have only a small effect on our final results and general conclusions. The differential conductance is then calculated as the derivative of the current with respect to the voltage [15]:[])(T )(T G G D S 021m m +=, (2) where 5.77h /e 2G 20»= [μS] is the quantum of conductance.Formula for the transmission probability can be expressed in the convenient matrix form[12]:[]+++--=G )(G )(tr )E (T D D S S S S S S , (3)where D /S S and are self-energy terms of the source/drain electrode and the Green ’s function of the molecule is expressed as follows:1D S ]H ES [G ----=S S . (4)Here S denotes overlapping matrix (where the overlap between the nearest-neighbor sites is assumed to be equal to 0.25). Since only delocalized π-electrons dictate the transport properties of organic molecules, the electronic structure of the molecule is described by a simple H ückel Hamiltonian H with one π-orbital per site (atom) [16], where overlapping is explicitly included (using non-orthogonal basis set of atomic orbitals). Throughout this work we take the standard energy parameters for organic conjugated systems: on-site energy is 6.6-=a eV and nearest-neighbor hopping integral is 7.2-=b eV. In the H ückel π-bond picture, all carbon and sulfur atoms are treated equivalently (because of their electronegativity). In our simplified model, the coupling to the electrodes is treated through the use of Newns-Anderson chemisorption theory [11], where ideal electrodes are described by constant density of states within energy bandwidth [17-20]. So self-energy matrices (S ) take the diagonal form with elements equal to i 05.0- [eV].Fig.2 Transmission as a function of electron energy (with respect to Fermi energy level)for devices in configuration A (solid curve) and B (broken curve), respectively.Fig.3 Comparison of conductance spectra for devices in configurationA (solid curve) andB (broken curve), respectively. III. Results and discussionNow we proceed to analyze our results from the point of view of quantum interference effects. The geometry of the molecule is taken to be that of anthracene with sulfur atoms on either end of the molecule, binding it to the electrodes in two different configurations – para(A) and meta (B), respectively. For isolated anthracene the HOMO is at 614.7- eV and the LUMO is at 352.5- eV. Because of our simplification that Fermi level is arbitrarily chosen to be located in the middle of the HOMO-LUMO gap, 483.6E F -= eV. The HOMO-LUMO gap for molecular system in para configuration is reduced from 262.2 eV for anthracene to the value of 667.0 eV, but for molecular system in meta configuration it is reduced to zero.Figure 2 shows the transmission dependence on the electron energy for anthracene in para (A) and meta (B) connections with identical electrodes. For transparency we plot it in the logarithmic scale. Asymmetry of the transmission function (with respect to the Fermi energy level) is due to non-orthogonality of atomic orbitals used to describe molecular system. The existence of resonances in the transmission probability is associated with resonant tunneling through molecular eigenstates. Such resonance peaks are shifted and broadened by the fact of the coupling with the electrodes (just like discrete energy levels of the molecule). A change in the configuration of connection between anthracene and two electrodes results in variation of the interference conditions and obvious changes in the transmission function. It manifests itself as shifts in the resonance peaks and in reduction of their height. Well-separated energy levels give rise to distinct peaks in the spectrum, while molecular levels close in energy can overlap and eventually interfere (reduction of resonance peaks is due to destructive interference).Fig.4 Comparison of current-voltage characteristics for devices in configurationA (solid curve) andB (broken curve), respectively.Another remarkable feature of the transmission spectrum is the appearance of antiresonances, which are defined as transmittance zeros and correspond to the physical situation for incident electron being perfectly reflected by a molecule. There are two different mechanisms (well-known in literature) responsible for the origin of antiresonances. One of these is associated with interference between the different molecular orbitals through which the electron propagates [2,21]. The second mechanism is due entirely to the non-orthogonality of atomic orbitals on different atoms [17]. In principle, transport problem in which a non-orthogonal basis set of states is used can be solved by a method proposed recently by Emberly and Kirczenow [5], where condition for antiresonances was analytically demonstrated. However, in this work we perform numerical evaluations of energies at which incoming electron has no chance to leave the source electrode. There are six antiresonances for device in configuration A (F E 821.2E +-=, F E 160.2+-, F E 622.1+-, F E 320.2+,F E 600.3+, F E 907.5+) and only one for device in configuration B (F E E =). Antiresonance is predicted to manifest itself by producing a drop in the differential conductance [5]. Moreover, the fact that it is generated exactly at the Fermi energy of metallic electrodes has important consequences for the conductance spectrum in which antiresonance can be observed (as shown in fig.3). However, in practice this unusual phenomenon can be blurred by some neglected factors which are present in realistic systems, such as: Stark effect, σ states, σ-π hybridization or many-body effects.In figure 4 we plot the current-voltage (I-V) characteristics for both analyzed structures (in para – A and meta – B connections, respectively). The current steps are attributed to the discreteness of molecular energy levels as modified by the coupling with the electrodes [12]. Because this coupling is assumed to be small (bad contacts are suggested by experimental data [1]), the transmission peaks are very narrow and therefore the I-V dependence has a step-like character. In particular, the height of the step in the I-V curve is directly proportional to the area of the corresponding peak in the transmission spectrum. Since quantum interference is important in determining the magnitudes of the resonance peaks, it is also crucial for calculations of the tunneling current. Indeed, the magnitude of the current flowing through the device is very sensitive on the manner of attachment between anthracene molecule and metal surfaces. Large values of the current are predicted for device of configuration A, while reduction of the current by orders of magnitude is expected for device of configuration B (although the shape of the I-V curve is similar in both cases). Such reduction is caused by destructive interference.IV. SummaryIn this paper we have examined the possibility that quantum interference can substantially affect the conductance in molecular-scale devices. The results have shown a striking variation of all the transport characteristics depending on the geometry of the molecular system (its connection with the electrodes). Anyway, the quantum effect of destructive interference may be used within the molecular device to switch its conductivity on and off [8,9]. The existence of interference effects in molecular devices open the question of their control. The phase shift of molecular orbitals could be controlled by a transverse magnetic field or a longitudinal electric field. However, magnetic field seems to be too large to produce significant phase shift (according to our simulations – hundreds of Teslas). AcknowledgmentsAuthor is very grateful to B. Bułka, T. Kostyrko and B. Tobijaszewska for illuminating discussions. Special thanks are addressed to S. Robaszkiewicz for his stimulating suggestions.References1E-mail address: walczak@.pl[1] M. A. Reed, Proc. IEEE 87, 625 (1999) and references therein.[2] P. Sautet, C. Joachim, Chem. Phys. Lett. 153, 511 (1988).[3] V. Marvaud, J. P. Launay, C. Joachim, Chem. Phys. 177, 23 (1993).[4] M. N. Paddon-Row, K. D. Jordan, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 115, 2952 (1993).[5] E. Emberly, G. Kirczenow, J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 11, 6911 (1999).[6] M. Magoga, C. Joachim, Phys. Rev. B 59, 16011 (1999).[7] C. Untiedt, G. Rubio Bollinger, S. Vieira, N. Agraït, Phys. Rev. B 62, 9962 (2000).[8] R. Baer, D. Neuhauser, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124, 4200 (2002).[9] R. Baer, D. Neuhauser, Chem. Phys. 281, 353 (2002).[10] H. Sellers, A. Ulman, Y. Shnidman, J. E. Eilers, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 115, 9389 (1993).[11] V. Mujica, M. Kemp, M. A. Ratner, J. Chem. Phys. 101, 6849 (1994);ibid. 101, 6856 (1994); ibid. 104, 7296 (1996).[12] S. Datta, Electronic transport in mesoscopic systems, Cambridge University Press,Cambridge 1995.[13] S. Datta, W. Tian, S. Hong, R. Reifenberger, J. I. Henderson, C. P. Kubiak,Phys. Rev. Lett. 79, 2530 (1997).[14] S. N. Yaliraki, A. E. Roitberg, C. Gonzalez, V. Mujica, M. A. Ratner,J. Chem. Phys. 111, 6997 (1999).[15] W. Tian, S. Datta, S. Hong, R. Reifenberger, J. I. Henderson, C. P. Kubiak,J. Chem. Phys. 109, 2874 (1998).[16] E. G. Emberly, G. Kirczenow, Nanotechnology 10, 285 (1999).[17] M. Kemp, A. Roitberg, V. Mujica, T. Wanta, M. A. Ratner,J. Phys. Chem. 100, 8349 (1996).[18] L. E. Hall, J. R. Reimers, N. S. Hush, K. Silverbrook, J. Chem. Phys. 112, 1510 (2000).[19] J. E. Han, V. H. Crespi, Appl. Phys. Lett. 79, 2829 (2001).[20] S. T. Pantelides, M. Di Ventra, N. D. Lang, Physica B 296, 72 (2001).[21] A. Cheong, A. E. Roitberg, V. Mujica, M. A. Ratner,J. Photochem. Photobiol. A 82, 81 (1994).。

霍尔效应及其相关效应

由于一个电 子现在附着了 三个量子磁通, 这就解释了分 数量子霍尔效 应中的 n=1/3. 示意图如上, 穿 过电子的三根 线即为三个量 子磁通.

Quantum Hall Effects

M. O. Goerbig (Submitted on 10 Sep 2009 (v1), last revised 21 Oct 2009 (this version, v2)) These lecture notes yield an introduction to quantum Hall effects both for non-relativistic electrons in conventional 2D electron gases (such as in semiconductor heterostructures) and relativistic electrons in graphene. After a brief historical overview in chapter 1, we discuss in detail the kinetic-energy quantisation of non-relativistic and the relativistic electrons in a strong magnetic field (chapter 2). Chapter 3 is devoted to the transport characteristics of the integer quantum Hall effect, and the basic aspects of the fractional quantum Hall effect are described in chapter 4. In chapter 5, we briefly discuss several multicomponent quantum Hall systems, namely the quantum Hall ferromagnetism, bilayer systems and graphene that may be viewed as a four-component system. Comments: 102 pages; lecture notes for the Singapore session ``Ultracold Gases and Quantum Information'' of Les Houches Summer School, 2009; v2 contains minor corrections and additional references Subjects: Mesoscale and Nanoscale Physics (cond-mat.mes-hall); Strongly Correlated Electrons (cond-mat.str-el) Cite as: arXiv:0909.1998 [cond-mat.mes-hall] (or arXiv:0909.1998v2 [cond-mat.mes-hall] for this version) Submission history From: M. O. Goerbig [view email] [v1] Thu, 10 Sep 2009 17:38:01 GMT (1867kb) [v2] Wed, 21 Oct 2009 09:06:49 GMT (1858kb)

The Unitary Transformation in Quantum Teleportation

a r X i v :q uant-ph/064195v126A pr26The Unitary Transformation in Quantum Teleportation Zheng-Chuan Wang Department of Physics,The Graduate School of the Chinese Academy of Sciences,P.O.Box 4588,Beijing 100049,China.February 1,2008Abstract In the well known treatment of quantum teleportation,the receiver should convert the state of his EPR particle into the replica of the un-known quantum state by one of four possible unitary transformations.However,the importance of these unitary transformations must be em-phasized.We will show in this paper that the receiver can not trans-form the state of his particle into an exact replica of the unknown state which the sender want to transfer if he have not a proper implementation of these unitary transformations.In the procedure of converting state,the inevitable coupling between EPR particle and environment which is needed by the implementation of unitary transformations will reduce the accuracy of the replica.03.67.Hk,03.67.-a,03.65.Ta..In 1993,Bennett et al.[1]proposed a famous treatment to transfer an intact quantum state from one place to another by use of the long-range correlation between EPR pair of particles.In their scheme,an unknown state and one of EPR particles are given to the sender,and the sender then perform a complete measurement on the joint system of the unknown state and her EPR state.After this,the receiver will perform a unitary transformation on the second particle ofthe EPR pair to obtain the replica of the unknown state,certainly,this unitary transformation is determined by the results of measurement told by the sender through a classical channel.The experimental realizations of their treatment were exhibited by Bouwmeester et al.[2]and Boschi et al.[3],respectively,in which an initial photon which carries the polarization is transferred by use of a pair of entangled photons prepared in an EPR state.These approaches to quantum teleportation had inspired many investigations into this field,such as the discussions of continuous variable quantum teleportation[4,5,6],the analysis of quantum fluctuation in the teleportation[7]etc.However,it should be pointed out that the physical implementation of the unitary transformations on the second EPR particle should be noticed,they1are not mere the pure mathematical transformations,we need realize these uni-tary transformations by other physical systems.For convenience,we summarily call these system′environment′.The inevitable interaction between EPR par-ticle in the hands of receiver and the environment will affect the replica of theunknown state.Even worse,if we have not properly chosen the physical real-ization of these unitary transformations,the unknown quantum state will not be teleported enough accurately because of the influence of environment.Suppose a sender,traditionally called′Alice′,who wish to communicate an unknown quantum state|Ψ =a|0 +b|1 of spin-1/2particle(particle1)to a receiver,′Bob′.Two other spin-1/2particles are prepared in an EPR singlet state.According to Bennett et al.′s treatment,one EPR particle(particle2)is given to Alice,the other(particle3)is given to Bob.Alice makes a combined measurement on her EPR particle2and the unknown particle1,then Bob′s particle3will be in one of the following four pure states:-a|0 3−b|1 3,-a|0 3+b|1 3,b|0 3+a|1 3,and-b|0 3+a|1 3.In the ideal case,Bob can convert the state of particle3into an exact replica of the initial state|Ψ =a|0 +b|1 by a unitary transformation which depends on the results of measurement told by Alice via classical channel.However,these unitary transformations must be performed through other physical systems or apparatus,which can be summarily described as′environment′,then the interaction between particle3and the ′environment′occurs,which will couple the quantum state of environment with particle3and violate the accurate replica of the initial quantum state|Ψ .In fact,the above interaction between particle3and environment makes the quantum state of the combined system(particle3-environment)evolves as follows[8]|Φ(t=t0) =|E0 ⊗|Ψ 3(1)−→|Φ(t>t1) =C0a|E0 |0 3+C1b|E1 |1 3.In the above,|E0 ,|E1 are the state vectors of environment,while|Ψ 3de-scribes the quantum state of particle3.As a result of particle3-environment interaction,the correlation between particle and environment has been estab-lished after time t1,the state vectors of particle3and environment have coupled to each other after time t1.Expression(1)clearly demonstrates the violation of pure state|Ψ 3after the practical implementation of unitary transformations. We can also show this violation by its density matrix.The reduced density matrix of particle3isρ3=T r E[|Φ(t>t1) Φ(t>t1)|](2) =(|C0a|2+|C0a|2| E1|E0 |2)|0 0|+(2C0C∗1ab∗ E1|E0 )|0 1| +(2C1C∗0ba∗ E0|E1 )|1 0|+(|C1b|2+|C1b|2| E0|E1 |2)|1 1|. When the state vectors|E0 ,|E1 of environment are orthogonal to each other,2the density matrix can reduce toρ3=|C0a|2|0 0|+|C1b|2|1 1|,(3) which indicates pure state|Ψ 3has become to a mixture state.Generally,the pure state|Ψ 3of Bobs EPR particle will reduce to a mixture state after a practical realization of unitary transformations,in the end Bob can not obtain a pure state of particle3,and can not convert|Ψ 3into the initial pure state |Ψ which Alice sought to teleport.An unknown quantum state can thus not be teleported enough accurately because of the physical implementation of unitary transformations.In the general,there exists deviation between the replica of unknown state in the hands of Bob after practical unitary transformation and the initial quantum state|Ψ 1prepared by Alice.We can evaluate the above deviation by the difference betweenρ3and the density matrixρ1of pure state|Ψ 1,it isδ=√√a|A 0|0 |0 +b|A 1|1 |1 ,where|A i(i=0,1)are the quantum state vectors of apparatus,and the new state vectors|0 and|1 in the outcome are pro-vided by the environment.There are correlation between the unknown state and the state vectors of environment.The general state vectors of environ-ment|A i|i (i=0,1)just correspond to the state vectors C i|E i (i=0,1)of environment in expression(1).So our above analysis is equivalent to quantum non-cloning theorem,it is the environment that leads to the impossibility for an unknown state being cloned accurately,the interaction of particle and envi-ronment will cause the decoherence of pure state of particle to a mixture state. To teleport an unknown quantum state enough accurately will eventually break the quantum non-cloning theorem because of the influence of environment.In summary,we have shown that an unknown quantum state can not be teleported enough accurately from one place to another when we consider the practical physical implementation of unitary transformations except some spe-cial cases.The coupling of environment and particle will reduce the accuracy of converting procedure,it is another manifest of quantum non-cloning theorem.AcknowledgmentsThis work is supported by the NNSF(Grant No.10404037). References[1]C.H.Bennett,G.Brassard,C.Crepeau,R.Jozsa,A.Peres and W.K.Wootters,Phys.Rev.Lett.70,1895(1993).[2]D.Bouwmeester,J.Pan,K.Mattle,M.Eibl,H.Weinfurter and A.Zeilinger,Nature,390,575(1997).[3]D.Boschi,S.Branca,F.De Martini,L.Hardy and S.Popescu,Phys.Rev.Lett.,80,1121(1998).[4]A.Furusawa,J.L.Sorensen,S.L.Braunstein,C.A.Fuchs,H.J.Kimbleand E.S.Polzik,Science,282,706(1998).[5]S.L.Braunstein and H.J.Kimble,Phys.Rev.Lett,80,869(1998).[6]H.Yonezawa,T.Aoki and A.Furusawa,Nature,431,430(2004).[7]R.E.S.Polinghorne and T.C.Ralph,Phys.Rev.Lett.83,2095(1999).[8]W.H.Zurek,Phys.Rev.D26,1862(1982).[9]W.K.Wootters and W.H.Zurek,Nature,299,802(1982).4。

电子信息工程专业英语 课文翻译 Unit 04 译文

Unit 4 通信和信息论Unit 4-1第一部分:远程通信远程通信是远距离通信的信号传输,在现代,通常这个过程需要电子发射机发射电磁波,但是在早期远程通信包括使用烟火信号,鼓或旗语或日光仪。

今天,远程通信很普遍的,助推这一过程的设备如电视,无线电和电话在世界的许多地区都已很普遍。

还有连接这些设备的许多网络,包括计算机网络,公共电话网,无线电网和电视网络。

互联网上的计算机通信是众多通信的一个例子。

通信系统通常由通信工程师设计。

在这个领域中早期的发明家有Alexander Graham Bell, Guglielmo Marconi 和John Logie Baird。

通信在当今的世界经济发展中起着举足轻重的作用,通信产业的税收在世界总产值的比例已接近百分之三。

基本要素每个通信系统包括三个基本要素:采集信息并能将其转换为信号的发射机,传输信号的传输媒介,接收信号并能将其还原为有用信息的接收机。

考虑一个无线电广播的例子。

广播塔是发射机,收音机是接收机,传输媒介是自由空间。

通常通信系统都是双向的,一个设备既做发射机又做接收机,即收发器。

例如,移动手机就是一个收发器。

电话线上的通信称为点对点通信,因为只在一个发射机和一个接收机之间。

通过无线电广播的通信称为广播(一对多)通信,因为通信是在一个大功率的发射机和许多接收机之间。

模拟或数字信号可以是模拟的,也可以是数字的。

在模拟信号中,信号根据信息而连续变化。

在数字信号信息被编码为一组离散值(如,1和0)。

在传输过程中,模拟信号中的信息会因噪声而退化。

相反,只要噪声不超过一定的阈值,数字信号中的信息是不会丢失的。

这是数字信号相对于模拟信号一个关键的优点。

网络网络是由一个相互通信的发射机、接收机或收发机的集合。

数字网络由一个或多个路由器组成,路由器正确地将数据发送给用户。

模拟网路由一个或多个交换器组成,交换器在两个或多个用户间建立连接。

这两种网络都需要中继器,用于远距离传输时的放大或重建信号。

量子纠缠 双缝干涉 英语 范例

量子纠缠双缝干涉英语范例Engaging with the perplexing world of quantum entanglement and the double-slit interference phenomenon in the realm of English provides a fascinating journey into the depths of physics and language. Let's embark on this exploration, delving into these intricate concepts without the crutchesof conventional transition words.Quantum entanglement, a phenomenon Albert Einstein famously referred to as "spooky action at a distance," challengesour conventional understanding of reality. At its core, it entails the entwining of particles in such a way that the state of one particle instantaneously influences the stateof another, regardless of the distance separating them.This peculiar connection, seemingly defying the constraints of space and time, forms the bedrock of quantum mechanics.Moving onto the enigmatic realm of double-slit interference, we encounter another perplexing aspect of quantum physics. Imagine a scenario where particles, such as photons or electrons, are fired one by one towards a barrier with twonarrow slits. Classical intuition would suggest that each particle would pass through one of the slits and create a pattern on the screen behind the barrier corresponding tothe two slits. However, the reality is far more bewildering.When observed, particles behave as discrete entities, creating a pattern on the screen that aligns with the positions of the slits. However, when left unobserved, they exhibit wave-like behavior, producing an interferencepattern consistent with waves passing through both slits simultaneously. This duality of particle and wave behavior perplexed physicists for decades and remains a cornerstoneof quantum mechanics.Now, let's intertwine these concepts with the intricate fabric of the English language. Just as particles become entangled in the quantum realm, words and phrases entwineto convey meaning and evoke understanding. The delicate dance of syntax and semantics mirrors the interconnectedness observed in quantum systems.Consider the act of communication itself. When wearticulate thoughts and ideas, we send linguistic particles into the ether, where they interact with the minds of others, shaping perceptions and influencing understanding. In this linguistic entanglement, the state of one mind can indeed influence the state of another, echoing the eerie connectivity of entangled particles.Furthermore, language, like quantum particles, exhibits a duality of behavior. It can serve as a discrete tool for conveying specific information, much like particles behaving as individual entities when observed. Yet, it also possesses a wave-like quality, capable of conveying nuanced emotions, cultural nuances, and abstract concepts that transcend mere words on a page.Consider the phrase "I love you." In its discrete form, it conveys a specific sentiment, a declaration of affection towards another individual. However, its wave-like nature allows it to resonate with profound emotional depth, evoking a myriad of feelings and memories unique to each recipient.In a similar vein, the act of reading mirrors the double-slit experiment in its ability to collapse linguistic wave functions into discrete meanings. When we read a text, we observe its words and phrases, collapsing the wave of potential interpretations into a singular understanding based on our individual perceptions and experiences.Yet, just as the act of observation alters the behavior of quantum particles, our interpretation of language is inherently subjective, influenced by our cultural background, personal biases, and cognitive predispositions. Thus, the same text can elicit vastly different interpretations from different readers, much like the varied outcomes observed in the double-slit experiment.In conclusion, the parallels between quantum entanglement, double-slit interference, and the intricacies of the English language highlight the profound interconnectedness of the physical and linguistic worlds. Just as physicists grapple with the mysteries of the quantum realm, linguists navigate the complexities of communication, both realmsoffering endless opportunities for exploration and discovery.。

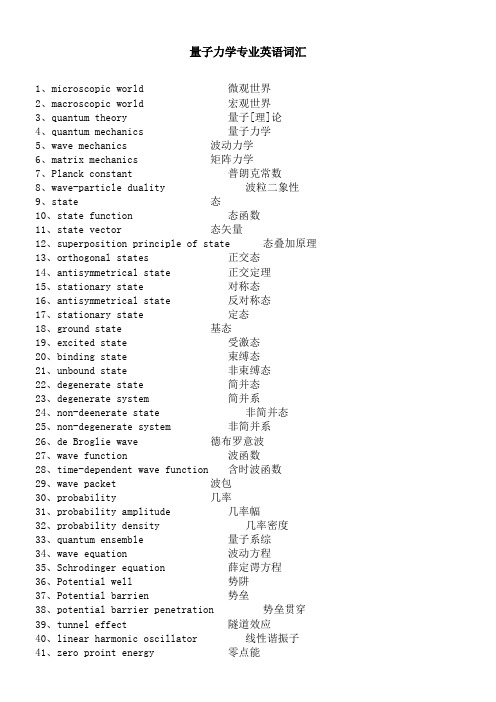

量子力学英语词汇

量子力学专业英语词汇1、microscopic world 微观世界2、macroscopic world 宏观世界3、quantum theory 量子[理]论4、quantum mechanics 量子力学5、wave mechanics 波动力学6、matrix mechanics 矩阵力学7、Planck constant 普朗克常数8、wave-particle duality 波粒二象性9、state 态10、state function 态函数11、state vector 态矢量12、superposition principle of state 态叠加原理13、orthogonal states 正交态14、antisymmetrical state 正交定理15、stationary state 对称态16、antisymmetrical state 反对称态17、stationary state 定态18、ground state 基态19、excited state 受激态20、binding state 束缚态21、unbound state 非束缚态22、degenerate state 简并态23、degenerate system 简并系24、non-deenerate state 非简并态25、non-degenerate system 非简并系26、de Broglie wave 德布罗意波27、wave function 波函数28、time-dependent wave function 含时波函数29、wave packet 波包30、probability 几率31、probability amplitude 几率幅32、probability density 几率密度33、quantum ensemble 量子系综34、wave equation 波动方程35、Schrodinger equation 薛定谔方程36、Potential well 势阱37、Potential barrien 势垒38、potential barrier penetration 势垒贯穿39、tunnel effect 隧道效应40、linear harmonic oscillator 线性谐振子41、zero proint energy 零点能42、central field 辏力场43、Coulomb field 库仑场44、δ-function δ-函数45、operator 算符46、commuting operators 对易算符47、anticommuting operators 反对易算符48、complex conjugate operator 复共轭算符49、Hermitian conjugate operator 厄米共轭算符50、Hermitian operator 厄米算符51、momentum operator 动量算符52、energy operator 能量算符53、Hamiltonian operator 哈密顿算符54、angular momentum operator 角动量算符55、spin operator 自旋算符56、eigen value 本征值57、secular equation 久期方程58、observable 可观察量59、orthogonality 正交性60、completeness 完全性61、closure property 封闭性62、normalization 归一化63、orthonormalized functions 正交归一化函数64、quantum number 量子数65、principal quantum number 主量子数66、radial quantum number 径向量子数67、angular quantum number 角量子数68、magnetic quantum number 磁量子数69、uncertainty relation 测不准关系70、principle of complementarity 并协原理71、quantum Poisson bracket 量子泊松括号72、representation 表象73、coordinate representation 坐标表象74、momentum representation 动量表象75、energy representation 能量表象76、Schrodinger representation 薛定谔表象77、Heisenberg representation 海森伯表象78、interaction representation 相互作用表象79、occupation number representation 粒子数表象80、Dirac symbol 狄拉克符号81、ket vector 右矢量82、bra vector 左矢量83、basis vector 基矢量84、basis ket 基右矢85、basis bra 基左矢86、orthogonal kets 正交右矢87、orthogonal bras 正交左矢88、symmetrical kets 对称右矢89、antisymmetrical kets 反对称右矢90、Hilbert space 希耳伯空间91、perturbation theory 微扰理论92、stationary perturbation theory 定态微扰论93、time-dependent perturbation theory 含时微扰论94、Wentzel-Kramers-Brillouin method W. K. B.近似法95、elastic scattering 弹性散射96、inelastic scattering 非弹性散射97、scattering cross-section 散射截面98、partial wave method 分波法99、Born approximation 玻恩近似法100、centre-of-mass coordinates 质心坐标系101、laboratory coordinates 实验室坐标系102、transition 跃迁103、dipole transition 偶极子跃迁104、selection rule 选择定则105、spin 自旋106、electron spin 电子自旋107、spin quantum number 自旋量子数108、spin wave function 自旋波函数109、coupling 耦合110、vector-coupling coefficient 矢量耦合系数111、many-particle system 多子体系112、exchange forece 交换力113、exchange energy 交换能114、Heitler-London approximation 海特勒-伦敦近似法115、Hartree-Fock equation 哈特里-福克方程116、self-consistent field 自洽场117、Thomas-Fermi equation 托马斯-费米方程118、second quantization 二次量子化119、identical particles 全同粒子120、Pauli matrices 泡利矩阵121、Pauli equation 泡利方程122、Pauli’s exclusion principle泡利不相容原理123、Relativistic wave equation 相对论性波动方程124、Klein-Gordon equation 克莱因-戈登方程125、Dirac equation 狄拉克方程126、Dirac hole theory 狄拉克空穴理论127、negative energy state 负能态128、negative probability 负几率129、microscopic causality 微观因果性。

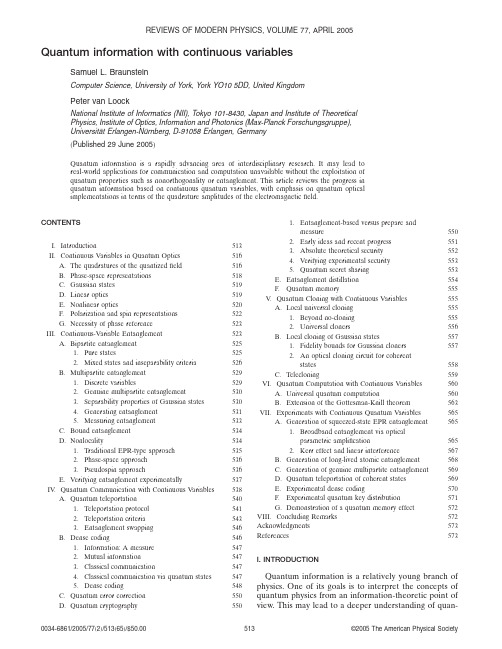

量子信息——连续变量篇