英国文学

英国文学各个时期流派

英国文学史各个时期中的文学流派古英语和中古英语时期古英语时期是指英国国家和英语语言的形成时期.最早的文学形式是诗歌, 以口头形式流传,主要的诗人是吟游诗人.到基督教传入英国之后,一些诗歌才被记录下来.这一时期最重要的文学作品是英国的民族史诗《贝奥武夫》,用头韵体写成.古英语时期(1066?1500)从1066年诺曼人征服英国,到1500年前后伦敦方言发展成为公认的现代英语.文学作品主要的形式有骑士传奇,民谣和诗歌.在几组骑士传奇中,有关英国题材的是亚瑟王和他的圆桌骑士的冒险故事,其中《高文爵士和绿衣骑士》代表了骑士传奇的最高成就.中世纪文学中涌现了大量的优秀民谣,最具代表性的是收录在一起的唱咏绿林英雄罗宾汉的民谣.3,最重要的诗人是被称为"英国诗歌之父"的乔叟,代表作是《坎特伯雷故事集》,取得了很高的艺术成就.他首创了诗歌的双韵体?每两行压韵的五步抑扬格,后被许多英国诗人采用.乔叟用伦敦方言写作,奠定了用英语语言进行文学创作的基础,促进了英语语言文学的发展.文艺复兴时期的英国文学得到了空前的发展,在诗歌,散文和戏剧方面尤其兴盛.诗歌方面,新的诗体形式如十四行诗,无韵体诗被介绍到英国.重要的诗人有Philip Sidney,他不仅写了许多优美的十四行诗,还创作了最早的诗歌理论作品之一《诗辩》.Edmund Spenser用斯宾塞诗节创作了着名长诗《仙后》.莎士比亚除了戏剧创作之外也是一位伟大诗人,着有两部叙事诗,两部长诗和154首十四行诗.英文的《圣经钦定本》作成于1611年,不仅具有重大的宗教意义,也是一部伟大的文学作品,并且对英国的语言文化产生了深远的影响.它的纯朴,平易,明晰的散文风格奠定了英国散文的传统.一个着名的哲学家兼散文家是Francis Bacon,他的文学着作主要有《随笔》,收录了他在各个时期发表的58篇随笔,思想深刻,文笔简洁,富有警句格言.戏剧代表文艺复兴时期英国文学的最高成就.主要戏剧家有马洛(Christopher Marlowe), 莎士比亚(W. Shakespeare).17世纪的英国文学17世纪是英国社会剧烈动荡的时期之一,由于君主专制和资产阶级之间的矛盾,爆发了1642年的内战并导致了1688年的"光荣革命".与政治斗争和资产阶级革命思想紧密相连的是宗教斗争和清教徒思想.因此这一时期的文学和艺术多展示革命思想的发展与成长,并带有浓厚的清教主义倾向.两个代表作家是弥尔顿和班扬.弥尔顿的代表作〈失乐园〉和班扬的代表作〈天路历程〉都取材于〈圣经〉.〈天路历程〉是一部寓言作品,用"基督徒"到达天国的历程象征人类追求美好未来的进程.18世纪的英国文学18世纪产生了一种进步思潮?启蒙运动,这一时期的思想家和作家们崇尚理性,认为启蒙教化是改造社会的基本手段,因此18世纪又被称为"理性的时代".在文学领域体现为18世纪上半期的新古典主义,代表作家有诗人蒲伯(A. Pope)和期刊随笔的创始人斯梯尔(R.Steele)和艾迪生(J.Addison).18中期兴起了英国现代小说,出现了大批有影响的小说家.理查逊(Samuel Richardson)的小说〈帕美拉〉(Pamela)采用书信体形式对人物的心理活动进行细致的描写,大大丰富了小说的创作方法.哥尔德史密斯(Oliver Goldsmith)的〈威克菲牧师传〉(The Vicar of Wakefield)是英国文学史上着名的感伤小说之一.劳伦斯斯特恩(Laurence Sterne)打破传统的叙事方法,创作了〈项迪传〉,而被认为是英国现代派文学的先驱.迪福(Daniel Defoe)是英国文学史上第一个现实主义小说家,代表作是〈鲁滨逊漂流记〉.讲述故事情节并分析鲁滨逊这一人物形象.斯威夫特是英国文学史上着名的讽刺小说家,以犀利的文笔对教会和社会的虚伪腐败进行了辛辣的讽刺.代表作是〈格列佛游记〉菲尔丁是英国最杰出的小说家之一,在理论与实践上都为英国小说的发展作出了贡献.在他的代表作〈汤姆?琼斯〉中,他塑造了众多栩栩如生的人物,展示了错综复杂的社会矛盾.讲述故事情节,分析主题和主要人物形象19世纪的英国文学19世纪英国文学主要包括上半期的浪漫主义时期和中后期的批判现实主义小说.布来克和罗伯特?彭斯属于前浪漫主义诗人.布来克的代表作品有〈天真之歌〉和〈经验之歌〉.彭斯是着名的苏格兰民族诗人,写了很多脍炙人口的歌颂友谊,爱情,自由,平等的诗歌,其中〈一朵红红的玫瑰〉广为流传.浪漫主义全盛时期以华滋华斯与柯律维治联合发表〈抒情歌谣集〉为开始,到瓦尔特斯各特的逝世为止,主要文学成就为诗歌,涌现了华滋华斯为代表的"湖畔派"诗人和拜伦,雪莱,济慈等富有革命理想,颂扬自由与解放的诗人.19世纪中后期的批判现实主义作家真实地描写了英国资产阶级的社会生活,暴露和批判了资产阶级社会的罪恶,对人民群众寄予了深刻的同情.狄更斯是英国最杰出的批判现实主义小说家,善于描写社会底层人们的生活和思想,作品题材广泛,思想深刻;萨克雷则善于描写上层社会形形色色的人物.批判现实主义女性小说家及她们的代表作品:Charlotte Bronte, Emily Bronte, Mrs. Gaskell, George Eliot.分析简?爱这一人物形象并分析小说的主题思想.托马斯?哈代是19世纪末20世纪初英国最伟大的现实主义小说家,他称自己的作品是"性格与环境的小说".代表作品是〈德伯家的苔丝〉.20世纪的现代派作家人们对西方文明的危机感和第二次世界大战的恶果促成了西方现代派文学的形成.主要表现为意识流小说,代表作家有詹姆斯乔伊斯和弗洁尼亚沃尔夫.乔伊斯的小说〈尤利西斯〉描写的是现代都市居民庸俗,猥琐的精神生活.弗洁尼亚的〈到灯塔去〉则运用了娴熟的象征手法和意识流技巧.英国文学发展史及每个阶段的特点毋庸置疑,英国小说是世界艺术之林中的一大景观。

英国文学——精选推荐

英国⽂学源远流长,经历了长期、复杂的发展演变过程。

在这个过程中,⽂学本体以外的各种现实的、历史的、政治的、⽂化的⼒量对⽂学发⽣着影响,⽂学内部遵循⾃⾝规律,历经盎格鲁-撒克逊、⽂艺复兴、新古典主义、浪漫主义、现实主义、现代主义等不同历史阶段。

下⾯对英国⽂学的发展过程作⼀概述。

⼀、中世纪⽂学(约5世纪-1485) 英国最初的⽂学同其他国家最初的⽂学⼀样,不是书⾯的,⽽是⼝头的。

故事与传说⼝头流传,并在讲述中不断得到加⼯、扩展,最后才有写本。

公元5世纪中叶,盎格鲁、撒克逊、朱特三个⽇⽿曼部落开始从丹麦以及现在的荷兰⼀带地区迁⼊不列颠。

盎格鲁-撒克逊时代给我们留下的古英语⽂学作品中,最重要的⼀部是《贝奥武甫》(Beowulf),它被认为是英国的民族史诗。

《贝奥武甫》讲述主⼈公贝尔武甫斩妖除魔、与⽕龙搏⽃的故事,具有神话传奇⾊彩。

这部作品取材于⽇⽿曼民间传说,随盎格鲁-撒克逊⼈⼊侵传⼊今天的英国,现在我们所看到的诗是8世纪初由英格兰诗⼈写定的,当时,不列颠正处于从中世纪异教社会向以基督教⽂化为主导的新型社会过渡的时期。

因此,《贝奥武甫》也反映了7、8世纪不列颠的⽣活风貌,呈现出新旧⽣活⽅式的混合,兼有⽒族时期的英雄主义和封建时期的理想,体现了⾮基督教⽇⽿曼⽂化和基督教⽂化两种不同的传统。

公元1066年,居住在法国北部的诺曼底⼈在威廉公爵率领下越过英吉利海峡,征服英格兰。

诺曼底⼈占领英格兰后,封建等级制度得以加强和完备,法国⽂化占据主导地位,法语成为宫廷和上层贵族社会的语⾔。

这⼀时期风⾏⼀时的⽂学形式是浪漫传奇,流传最⼴的是关于亚瑟王和圆桌骑⼠的故事。

《⾼⽂爵⼠和绿⾐骑⼠》(Sir Gawain and the Green Knight,1375-1400)以亚瑟王和他的骑⼠为题材,歌颂勇敢、忠贞、美德,是中古英语传奇最精美的作品之⼀。

传奇⽂学专门描写⾼贵的骑⼠所经历的冒险⽣活和浪漫爱情,是英国封建社会发展到成熟阶段⼀种社会理想的体现。

英国文学简史分类

英国文学简史分类一、古英国文学古英国文学是指公元5世纪至公元11世纪之间的英国文学作品。

这一时期的文学作品主要以英国盎格鲁人和撒克逊人的口头传承方式流传下来。

最早的古英国文学作品是口头传承的史诗,如《贝奥武夫》和《西德里克史诗》。

这些作品描绘了英雄壮举和神话传说,展现了古英国人的价值观和文化背景。

二、中世纪文学中世纪文学是指公元11世纪至15世纪之间的英国文学作品。

这一时期的文学作品受到基督教和法国文学的影响,主题涉及爱情、骑士精神和宗教信仰等。

最著名的中世纪文学作品是《亚瑟王传奇》,它描绘了亚瑟王和圆桌骑士的故事,体现了骑士精神和中世纪的价值观。

此外,还有一些宗教戏剧,如《诗篇》和《谢弗尔诗篇》等,用于教育和传播基督教信仰。

三、文艺复兴文学文艺复兴文学是指16世纪至17世纪初期的英国文学作品。

这一时期的文学作品受到古希腊罗马文化的影响,主题多样化,包括诗歌、戏剧、散文等。

著名的文艺复兴文学作品包括莎士比亚的戏剧作品,如《哈姆雷特》和《罗密欧与朱丽叶》,以及约翰·米尔顿的史诗《失乐园》等。

这些作品在文学史上具有重要地位,对后世的文学创作产生了深远影响。

四、启蒙时代文学启蒙时代文学是指18世纪的英国文学作品。

这一时期的文学作品反映了对理性、科学和人权的追求。

著名的启蒙时代作家包括约翰·洛克、伊莱扎·海伍德和亚当·斯密等。

他们的作品涉及政治、哲学和经济等领域,对当时社会产生了重要影响。

其中,洛克的《人类理解论》被认为是启蒙运动的经典之作。

五、浪漫主义文学浪漫主义文学是指19世纪初期的英国文学作品。

这一时期的文学作品强调个人情感、自然景观和想象力。

著名的浪漫主义作家包括威廉·华兹华斯、塞缪尔·泰勒·柯勒律治和乔治·戈登·拜伦等。

他们的作品描绘了自然的壮丽和人类的内心世界,对后世文学产生了深远影响。

其中,华兹华斯的《抒情诗集》被誉为浪漫主义诗歌的代表作品。

英国文学各个时期的特点

英国文学7个时期英国文学发端于中世纪,经历了古英语、中古英语、文艺复兴、17世纪、18世纪、19世纪、20世纪文学7个时期,取得了举世瞩目的成就。

古英语文学英国在10世纪以前属于古英语时期,早期的凯尔特等部族及5世纪入侵的盎格鲁初都没有留下书面文学。

6世纪末到7世纪末,由于肯特国王阿瑟尔伯特皈依基督教,该教僧侣开始以拉丁文著书写诗,其中以比德所著《英国人民宗教史》最有历史和文学价值。

9世纪,威塞克斯国王阿尔弗雷德为振兴文化,组织人力将各种拉丁文著作译成英语,并倡导以英语撰写《盎格鲁-撒克逊编年史》,其中包括有关盎格鲁-撒克逊和朱特人的英雄史诗《贝奥武甫》和《朱迪斯》,以及一些抒情诗、方言诗、谜语和宗教诗、宗教记述文、布道词。

中古英语文学11世纪,随着诺曼人入侵,古英语渐渐演化为中古英语,文学上开始流行模仿法国的韵文体骑士传奇,其中以《高文骑士与绿衣骑士》最有艺术价值。

14世纪后半叶是中古英语发展的高峰,出现了似受古英语诗影响的口头韵体诗,最有名的长诗《农夫彼尔斯的幻想》,一般认为是教会人员朗兰德所写,以中世纪梦幻故事的形式探讨人间善恶,讽刺社会丑行,表达对贫苦农民的深切同情。

此时期国王查理第二当政,宫廷开始用盎格鲁-诺曼法语,王室贵族兴起赞助文人之风。

英国文学史上出现的第一位大诗人乔叟以其诗体短篇小说集《坎特伯雷故事集》和其他长短诗集成为英国文学的重要奠基人。

15世纪,有民间歌谣抄本流传至今,最有名的是关于绿林好汉罗宾汉的传说;马洛礼的散文小说《亚瑟王之死》为英国小说的雏形。

文艺复兴时期文学16世纪中叶至17世纪初主要是伊丽莎白女王时代,英国开始文艺复兴运动。

学者纷纷翻译意大利和法国学术、文学名著并自行著述,以托马斯·莫尔(1477~1535)的《乌托邦》最有价值。

英国文艺复兴文学最突出的是诗歌和戏剧。

西德尼(1554~1586)的十四行诗、斯宾塞的《仙后》都是诗歌方面的代表作。

在剧本中运用重韵体诗的文体,促使诗歌和戏剧两方面都达到空前的成就。

英国文学

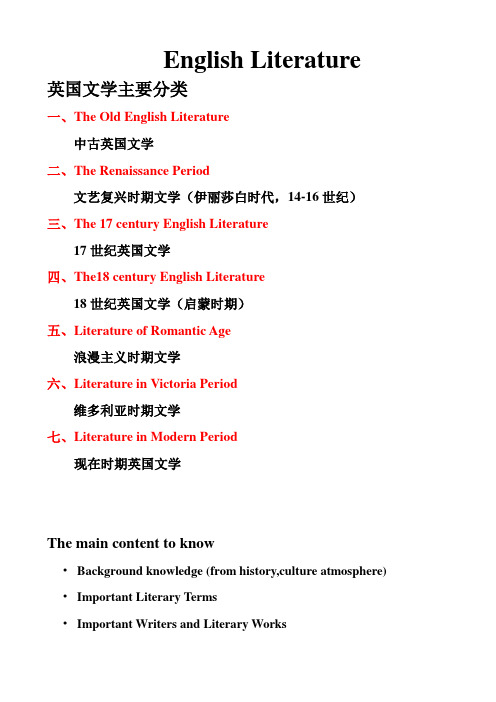

English Literature 英国文学主要分类一、The Old English Literature中古英国文学二、The Renaissance Period文艺复兴时期文学(伊丽莎白时代,14-16世纪)三、The 17 century English Literature17世纪英国文学四、The18 century English Literature18世纪英国文学(启蒙时期)五、Literature of Romantic Age浪漫主义时期文学六、Literature in Victoria Period维多利亚时期文学七、Literature in Modern Period现在时期英国文学The main content to know•Background knowledge (from history,culture atmosphere) •Important Literary Terms•Important Writers and Literary WorksThe Old English Literature(一)General Introduction(总体介绍)The Old English literature(which lasted from 499 to 1066)isexclusively a verse(诗篇)literature in oral form.There were two groups of English poetry in this period-the first was the pagan(异教的)poetry represented by Beowulf,the second was the religious poetry represented by the works of Caedmon and Cynewulf.In the 8th century,Anglo-Saxon prose appeared.The most famous prose writers of that period were Venerable bede and Alfred the Great.After the Norman Conques,three languages existed in England,which were French spoken by the Normans,English spoken by the lower class and Latin spoken by the scholars and clergymen. The prevailing from of literature in the feudal England was the Romance.The Romance prospered for 300 years(1200-1500)from which we see an epitome(缩影)of the Middle Ages.In the 15th century,English ballads became very popular and the only important writer was Thomas Malory.(二)Important Literary TermsOld English(古英语):language spoken by the Anglo-Saxons is called the Old English,which is the foundation of English language and literature.Romance(中世纪的传奇故事):The Romance was the prevailing form of literature in the Middle Ages.It was a long composition, sometimes in verse, sometimes in prose, describing the life and adventures of a noble hero.(三)Important Writers and Literary Works1.Beowulf(《贝奥武甫》)Beowulf is the oldest poem in the English language and the most important spe-cimen of Anglo-Saxon literture.The main stories are based on the folk legends of the primitive northern tribes.2.Religious Poets(宗教诗人)Caedmon(卡德蒙,610-680)Caedmon is the first known religious poet of England.He is known as the father of English song, Caedmon’s Hymn (《卡德蒙的赞美诗》)is a praise poem in honor of god.Cynewulf(基涅武甫,公元九世纪)Cynewulf lived in the 9th century. He produced four poems, of which The Christ(《基督》)is the most characteristic. Throughout the poem, a deep love for Christ and reverence for Virgin Mary(圣母利亚)are expressed.3.Prose Writers(散文作家)Venerable Bede(可敬的比德,672-735)Bede,also referred to as Saint Bede(圣比德)or the Venerable Bede,is well known as an author and scholar,and his most famous work, Historia Ecclesiastica Gentis Anglorum, or An Ecclesiastica History of the English People(《英吉利人教会史》),gained him the title “The Father of English History”(英国史学之父)Alfred the Great(阿尔弗雷德大帝,849-899)Alfred is the only English monarch to be accorded the epithet “the Great”(唯一一个被授予“大帝”名号额英格兰国王).He was the first King of the West Saxons to style himself “King of the Anglo-saxons”(将自己命名为“盎格鲁-撒克逊之王”的西撒克逊国王).The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle(《盎格鲁-撒克逊编年史》)is a collection of annals(年鉴)in Old English chronicling the history of the Anglo-Saxons. original manusript of the Chronicle was created late in the 9th century, probably in Wessex,duing the reign of Alfred the Great.4.The Romance(传奇)Sir Gawain and the Green Knight(《高文爵士与绿衣骑士》)It is a romance of 2,530 lines derived from Celtic legend(凯尔特骑士).Sir Cawain, nephew of King Arthur, accepted the challenge of the Green Knight in the Green Chapel(绿教堂). At last, he got a girdle (腰带)as a gift from the Knight and his story became widely known.5.Age of Chaucer(乔叟时代)The 14th century is called “Age of Chaucer”.Chaucer and Langland(朗格兰,1332-1400,英国诗人),were the most important writers of age.Ceoffrey Chaucer(杰弗里·乔叟,1343-1400)Chaucer is acclaimed not only as “the father of English poetry”(英国诗歌之父),but also as “the father of English fiction (英国小说之父).His masterpiece, The Canterbury Tales(《坎特伯雷故事集》),is one of the most famous works in all literatures.Chaucer wrote in vivid and exact language; his poetry is full vigor and swiftness.Book of the Duchess 《公爵夫人之书》The House of Fame《声誉之宫》The Parliament of Fowls 《百鸟会议》The Legend of Good Women 《贤妇传说》Troilus and Criseyde 《特洛伊罗斯与克丽西达》6. The 15th Century Ballads(民歌,歌谣)Thomas Malory(托马斯·马洛礼,1405-1471)Tomas Malory wrote an important work called Le Morte d’Arthur(《亚瑟王之死》).The central concern is with the adventures of Arthur and his famous Knights of the Round Table(圆桌骑士).The book is very important in English literature.Its Arthurian materials have a strong influence on literature of later centuries.The Renaissance Period伊丽莎白时代,14—16世纪一)General Introduction(总体介绍)The Renaissance(文艺复兴)was a European phenomenon, which originated in Italy. The English Renaissance encouraged the reformation of the Church.In Elizabethan(伊丽莎白)period, English literature developed with great speed. The most distinctive achievement of Elizabethan literature is drama. Next to drama is the lyrical poetry(抒情诗),remarkable for its variety and freshness and romantic feeling.In that period, writing peotry became a fashion and England became “a nest of singing birds”. In tha same period, Francis Bacon wrote more than fifty excellent essays, which make him one of the best essayists(散文家)in English literature.(二)Important Literary Terms1)Renaissance:In the Renaissance Period, scholars began to emphasize the capacities of human mind and the achievements of human culture. So humanism(人文主义)became the keynote of English Renaissance. English Renaissance is divied into three periods:①the 1st period from 1516 to 1578 is called the beginning of the Renaissance.②The 2nd period from1578 to 1625 is known as the flowering period.③The 3rd period from 1625 to 1660 is the epilogue(尾声)of the Renaissance.2) Spenserian Stanza(斯宾塞诗体)Spenser invented a new verse form. Each stanza has nine lines, each of the first eight lines is in iambic pentameter and the ninth line is an iambic hexameter line.(每个诗节由九行组成,前八行为五步抑扬格,第九行为六步抑扬格。

英国文学

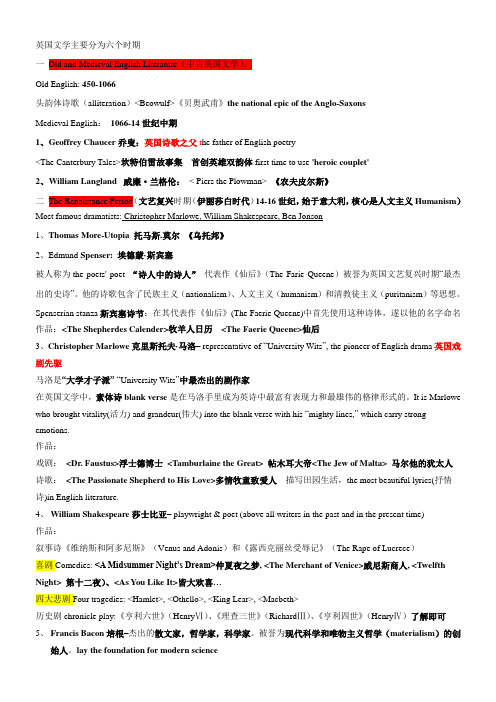

英国文学主要分为六个时期一Old and Medieval English Literature(中古英国文学)。

Old English: 450-1066头韵体诗歌(alliteration)<Beowulf>《贝奥武甫》the national epic of the Anglo-SaxonsMedieval English:1066-14世纪中期1、Geoffrey Chaucer乔叟:英国诗歌之父t he father of English poetry<The Canterbury Tales>坎特伯雷故事集首创英雄双韵体first time to use 'heroic couplet'2、William Langland 威廉·兰格伦:< Piers the Plowman>《农夫皮尔斯》二The Renaissance Period(文艺复兴时期(伊丽莎白时代)14-16世纪,始于意大利,核心是人文主义Humanism)Most famous dramatists: Christopher Marlowe, William Shakespeare, Ben Jonson1、Thomas More-Utopia 托马斯.莫尔《乌托邦》2、Edmund Spenser: 埃德蒙·斯宾塞被人称为the poets' poet “诗人中的诗人”代表作《仙后》(The Farie Queene)被誉为英国文艺复兴时期―最杰出的史诗‖。

他的诗歌包含了民族主义(nationalism)、人文主义(humanism)和清教徒主义(puritanism)等思想。

Spenserian stanza斯宾塞诗节:在其代表作《仙后》(The Faerie Queene)中首先使用这种诗体,遂以他的名字命名作品:<The Shepherdes Calender>牧羊人日历<The Faerie Queene>仙后3、Christopher Marlowe克里斯托夫·马洛– representative of ―University Wits‖, the pioneer of English drama英国戏剧先驱马洛是“大学才子派”―University Wits‖中最杰出的剧作家在英国文学中,素体诗blank verse是在马洛手里成为英诗中最富有表现力和最雄伟的格律形式的。

[英国文学作品]英国文学

![[英国文学作品]英国文学](https://img.taocdn.com/s3/m/d32b940017fc700abb68a98271fe910ef12dae45.png)

[英国文学作品]英国文学英国文学篇(1):10部英国经典小说10. 《名利场》Vanity Fair (William Makepeace Thackeray, 1848)威廉·梅克皮斯·萨克雷,1848年出版这部小说的主角或许就是英国文学史上最知名的非正统派女主角——贝奇·夏普,小说的情节围绕阶级、社会、跻身上流社会以及现代读者听来又熟悉又害怕的金融危机。

《名利场》这些要素全都具备, 讲述那个年代,也讲述着每一个年代。

9. 《科学怪人》Frankenstein (Mary Shelley, 1818)玛莉·雪莱,1818年出版这部先锋作品集科幻和哥特式恐怖于一身,营造了一个难以磨灭的“恶魔”主题,即科学家中的“现代普罗米修斯”,几世纪以来经久不衰。

8. 《大卫·科波菲尔》David Copperfield (Charles Dickens, 1850)查尔斯·狄更斯,1850年出版David Copperfield is populated by some of the most vivid characters ever created. They are as much a part of readers’ world, and their way of thinking about the world, as people they have actually met.《大卫·科波菲尔》人物形象众多,性格鲜活的角色云集。

这些人物角色仿佛是读者所在真实世界的一部分,和读者亲身遇见的人一样,有着相似的世界观。

7. 《呼啸山庄》Wuthering Heights (Emily Bront, 1847)艾米莉·勃朗特,1847年出版《呼啸山庄》“蕴含巨大的心理能量,没有其它书籍能够与之匹敌。

”读者推崇《呼啸山庄》是因为其“层层叠叠的叙述结构”和丰富惊人的想象力,更因为《呼啸山庄》超越了爱情故事本身,展现了我们转瞬即逝的欲望之下“永恒的震撼”。

英国文学 英语专业

英国文学英语专业

英国文学是英语专业中的一个重要分支,主要研究英国的历史、文化、传统以及文学作品。

在英语专业中,学生通常需要阅读和分析大量的英国文学作品,了解不同时期和流派的文学特点,以及英国文化和社会背景对文学作品的影响。

英国文学的学习内容包括莎士比亚、简·奥斯汀、查尔斯·狄更斯等著名作家的作品,以及浪漫主义、维多利亚时代、现代主义等不同时期的文学流派。

学生还需要学习文学理论和分析方法,以便更好地理解文学作品的主题、风格和技巧。

除了英国文学,英语专业还包括语言学、文学批评、文化研究等领域。

学生需要掌握英语语言的基本知识和技能,包括听、说、读、写、译等方面。

同时,学生还需要了解英语国家的文化和社会背景,以及语言和文化的相互作用。

总之,英国文学是英语专业中的一个重要组成部分,通过学习英国文学作品和文学理论,学生可以深入了解英国文化和历史,提高自己的语言和文学素养。

英国文学的发展及其代表作品

英国文学的发展及其代表作品引言英国文学是世界文学中一个极其重要的组成部分,具有悠久而辉煌的历史。

本文将探讨英国文学的发展历程,并介绍一些代表性的英国文学作品。

古代英国文学1.安格鲁-撒克逊时期(5世纪至11世纪)•凯尔特传统和民间故事•赫鲁晓斯史诗《贝奥武夫》2.中世纪文学(11世纪至15世纪)•亚瑟王传说(如马拉里《亚瑟王与圆桌骑士》)•杰弗里·乔叟的《坎特伯雷故事集》文艺复兴时期1.伊丽莎白时代(16世纪末至17世纪初)•威廉·莎士比亚的戏剧作品(如《哈姆雷特》、《罗密欧与朱丽叶》)•约翰·密尔顿的史诗作品《失乐园》2.马洛里时代(17世纪中期至18世纪初)•约翰·邓恩的诗集《鸟》•亚历山大·蒲柏的散文作品浪漫主义和维多利亚时代1.浪漫主义(18世纪末至19世纪初)•威廉·华兹华斯和塞缪尔·泰勒·柯勒律治的诗歌作品•简·奥斯汀的小说《傲慢与偏见》2.维多利亚时代(19世纪中期至20世纪初)•查尔斯·狄更斯的小说作品(如《雾都孤儿》、《双城记》)•奥斯卡·王尔德的戏剧作品(如《道林·格雷的画像》)现代英国文学1.20世纪早期•维吉尼亚·伍尔夫的小说《到灯塔去》•T.S.艾略特的诗歌集《荒原》2.当代文学•伊恩·麦克尤恩的小说作品(如《失落之城》、《英国病人》)•玛格丽特·阿特伍德的小说作品(如《使女的故事》)结论英国文学在各个时期都有着令人惊叹的成就,塑造了世界文学的重要角色。

从古代传统到现代创新,英国文学将继续为我们带来无尽的享受和启发。

注:以上只是一些代表性的英国文学作品,因篇幅限制未能详尽涵盖全部作品。

英国文学的作品

英国文学的作品英国文学拥有丰富而悠久的历史,涵盖了各种文体和风格。

以下是一些英国文学中的经典作品,这里列举的仅仅是其中的一小部分,而英国文学中还有很多其他优秀的作品:1. 莎士比亚戏剧:- "哈姆雷特"(Hamlet)- "罗密欧与朱丽叶"(Romeo and Juliet)- "麦克白"(Macbeth)- "奥赛罗"(Othello)2. 经典小说:- "简·爱"(Jane Eyre)- 夏洛蒂·勃朗特(Charlotte Brontë)- "傲慢与偏见"(Pride and Prejudice)- 简·奥斯汀(Jane Austen)- "大卫·科波菲尔"(David Copperfield)- 查尔斯·狄更斯(Charles Dickens)- "汤姆·琼斯的历险"(The History of Tom Jones, a Foundling)- 亨利·菲尔丁(Henry Fielding)3. 诗歌:- "抒情时代"(Lyrical Ballads)- 威廉·华兹华斯(William Wordsworth)和塞缪尔·泰勒·柯勒律治(Samuel Taylor Coleridge)合作- "诗的颂歌"(Songs of Innocence and of Experience)- 威廉·布莱克(William Blake)- "拜伦诗集"(Selected Poems of Lord Byron)- 乔治·戈登·拜伦(Lord Byron)4. 科幻文学:- "时间机器"(The Time Machine)- 威尔斯·赫伯特·乔治·威尔斯(H.G. Wells)- "1984" - 乔治·奥威尔(George Orwell)5. 战争文学:- "战争与和平"(War and Peace)- 列夫·托尔斯泰(Leo Tolstoy)6. 现代文学:- "追风筝的人"(The Kite Runner)- 卡勒德·胡赛尼(Khaled Hosseini)- "哈利·波特"系列- J.K. 罗琳(J.K. Rowling)这仅仅是英国文学中的一些代表性作品,实际上英国文学涵盖了更广泛的时间和主题。

英国文学 名词解释

英国文学名词解释

英国文学是指英格兰、苏格兰、威尔士和北爱尔兰地区的文学作品。

它的历史可以追溯到中世纪,经历了文艺复兴时期、启蒙时代、浪漫主义时期、维多利亚时代等不同的文学风格和时期。

英国文学的特点之一是其丰富多样的文学形式。

从中世纪的骑士传奇和中世纪诗歌到现代小说和诗歌,英国文学涵盖了各种各样的文学体裁。

其中一些最重要的文学体裁包括史诗、戏剧、诗歌、小说和散文。

这些不同的文学形式为英国文学带来了不同的风格和主题。

英国文学的另一个重要特点是其丰富多样的主题和风格。

从中世纪的宗教作品和史诗到现代小说和诗歌,英国文学涵盖了各种各样的主题。

它反映了社会、政治、宗教和文化变革的演变。

一些最常见的主题包括爱情、战争、自然、宗教、社会道德和个人发展。

不同的作家和时代也采用了不同的文学风格和技巧来表达这些主题。

英国文学的另一个重要方面是它的历史和文化意义。

通过阅读英国文学作品,我们可以了解英国历史的演变,了解英国社会和文化的发展。

英国文学作品中经常出现的历史事件、人物和地点也成为了文学研究和文化遗产的重要组成部分。

在英国文学中,有很多重要的作家和作品。

莎士比亚、狄更斯、奥斯卡·王尔德、简·奥斯汀和弗吉尼亚·伍尔夫都是英国文学史上的重要人物。

他们的作品不仅在英国有着广泛的影响力,也

对世界文学产生了重要的影响。

总之,英国文学是一个丰富多样的文学传统,它的作品涵盖了各种各样的文学形式、主题和风格。

通过阅读和研究英国文学作品,我们可以深入了解英国的历史、文化和文学发展。

英国文学史简介

英国文学史简介英国文学源远流长,经历了长期、复杂的发展演变过程。

在这个过程中,文学本体以外的各种现实的、历史的、政治的、文化的力量对文学发生着影响,文学内部遵循自身规律,历经盎格鲁-撒克逊、文艺复兴、新古典主义、浪漫主义、现实主义、现代主义等不同历史阶段。

下面对英国文学的发展过程作一概述。

一、中世纪文学(约5世纪-1485)英国最初的文学同其他国家最初的文学一样,不是书面的,而是口头的。

故事与传说口头流传,并在讲述中不断得到加工、扩展,最后才有写本。

公元5世纪中叶,盎格鲁、撒克逊、朱特三个日耳曼部落开始从丹麦以及现在的荷兰一带地区迁入不列颠。

盎格鲁-撒克逊时代给我们留下的古英语文学作品中,最重要的一部是《贝奥武甫》(Beowulf),它被认为是英国的民族史诗。

《贝奥武甫》讲述主人公贝尔武甫斩妖除魔、与火龙搏斗的故事,具有神话传奇色彩。

这部作品取材于日耳曼民间传说,随盎格鲁-撒克逊人入侵传入今天的英国,现在我们所看到的诗是8世纪初由英格兰诗人写定的,当时,不列颠正处于从中世纪异教社会向以基督教文化为主导的新型社会过渡的时期。

因此,《贝奥武甫》也反映了7、8世纪不列颠的生活风貌,呈现出新旧生活方式的混合,兼有氏族时期的英雄主义和封建时期的理想,体现了非基督教日耳曼文化和基督教文化两种不同的传统。

公元1066年,居住在法国北部的诺曼底人在威廉公爵率领下越过英吉利海峡,征服英格兰。

诺曼底人占领英格兰后,封建等级制度得以加强和完备,法国文化占据主导地位,法语成为宫廷和上层贵族社会的语言。

这一时期风行一时的文学形式是浪漫传奇,流传最广的是关于亚瑟王和圆桌骑士的故事。

《高文爵士和绿衣骑士》(Sir Gawain and the Green Knight,1375-1400)以亚瑟王和他的骑士为题材,歌颂勇敢、忠贞、美德,是中古英语传奇最精美的作品之一。

传奇文学专门描写高贵的骑士所经历的冒险生活和浪漫爱情,是英国封建社会发展到成熟阶段一种社会理想的体现。

英国文学名著必读

英国文学名著必读

英国文学有着悠久的历史和丰富的遗产,包括了许多经典名著。

以下是一些必读的英国文学名著。

1. 《傲慢与偏见》–简·奥斯汀所著。

这部小说是英国文学的经典之一,讲述了女主角伊丽莎白·班纳特的爱情故事,也是一部关于社会阶层和婚姻制度的戏剧。

2. 《呼啸山庄》–勃朗特姐妹所著。

这部小说描述了两个家族之间的恶意和复仇,以及热情和爱情的力量。

它是一部关于人性和道德的故事,也是一部英国文学中的经典之作。

3. 《雾都孤儿》–查尔斯·狄更斯所著。

这部小说讲述了孤儿奥利弗的冒险故事,以及他在维多利亚时代的贫困生活和社会不公。

它是一部关于社会和人性的故事,也是一部英国文学中的经典之作。

4. 《战争与和平》–列夫·托尔斯泰所著。

这部小说虽然不是英国文学作品,但是它对英国文学有着深刻的影响。

它是一部关于俄罗斯农民战争和拯救祖国的故事,也是一部关于爱情和家庭的故事。

5. 《鲁宾逊漂流记》–丹尼尔·笛福所著。

这部小说讲述了鲁宾逊在荒岛上生存的故事,以及他如何通过自己的聪明才智和勇气克服困难。

它是一部关于人性和

适应力的故事,也是英国文学中的经典之作。

这些作品代表了英国文学的不同流派和主题,从爱情和社会阶层到冒险和人性等各种领域。

无论你是英国文学爱好者还是新手,这些经典必读作品都值得一读。

英国文学的一些名词解释

英国文学的一些名词解释英国文学是世界文学宝库中的明珠,众多文学名著诞生于这片土地上。

提到英国文学,我们不仅仅要了解其中众多名著的作者和故事情节,我们还需要掌握一些专业术语和概念。

在本文中,我将为大家解释一些与英国文学相关的名词,帮助读者更好地理解英国文学的精髓。

一、浪漫主义浪漫主义是18世纪末到19世纪初兴起的一种文学运动,它强调个人感受、想象力和超凡脱俗的体验。

浪漫主义充满了激情和对自然、人类内心世界的热爱。

在英国文学史上,浪漫主义给予了众多优秀的作品,如《弗兰肯斯坦》、《唐吉诃德》等。

二、维多利亚时代维多利亚时代是指1837年至1901年英国女王维多利亚统治下的时期。

这个时代是英国工业革命达到巅峰的时期,但也是社会动荡和不平等的时期。

维多利亚时代的文学作品通常描写社会阶级落差、人性的复杂以及对女性地位的思考。

其中最著名的代表作品包括《雾都孤儿》、《呼啸山庄》等。

三、现代主义现代主义是20世纪初兴起的一种文学运动,它试图打破传统的叙事形式,挑战读者的理解和想象力。

现代主义作品通常以碎片化的结构、内心独白和流露出的不确定性为特点。

英国文学史上的现代主义代表作品有《尤利西斯》、《荒原》等。

四、战后文学战后文学是指第二次世界大战结束后,英国文学的新兴潮流。

在这一时期,英国文学持续呈现多样性和实验性。

战后文学关注社会变革、性别政治以及民族认同,并通过多种不同的写作风格和技巧来探索个体心理和文化理解。

该时期的代表作品包括《动物农场》、《1984》等。

五、北方现实主义北方现实主义是19世纪中叶至20世纪初期在英国出现的文学派别,它对于社会的现象和底层人民的生存状况进行了深刻而真实的描写。

北方现实主义作品通常关注社会困境和阶级冲突,以真实主义的手法展现人物的命运和社会环境的影响。

代表作品有《红与黑》、《战争与和平》等。

六、文学奖项文学奖项是评选和表彰优秀文学作品和作者的机构或组织举办的活动,也是文学界的重要盛事。

英国文学名词解释

英国文学名词解释英国文学是指在英国境内产生的文学作品,包括散文、诗歌、戏剧等多种文学形式。

以下是一些与英国文学相关的名词解释:1. 莎士比亚戏剧(Shakespearean Drama):指威廉·莎士比亚所创作的戏剧作品,包括《哈姆雷特》、《罗密欧与朱丽叶》等。

2. 简·奥斯汀小说(Jane Austen Novels):指英国女作家简·奥斯汀所写的一系列小说,主要描写中上层社会的生活,包括《傲慢与偏见》、《理智与情感》等。

3. 浪漫主义(Romanticism):指18世纪末至19世纪初的一种文艺运动,强调情感、个人主义和自然之美,代表作家有威廉·华兹华斯、塞缪尔·柯勒律治等。

4. 维多利亚时期文学(Victorian Literature):指19世纪中后期的英国文学,以女王维多利亚统治时期为背景,作品内容反映了社会变革和道德观念的转变,代表作家有查尔斯·狄更斯、乔治·艾略特等。

5. 符号主义(Symbolism):指19世纪末20世纪初的一种文学流派,强调象征和隐喻的运用,代表作家有奥斯卡·王尔德、D·H·劳伦斯等。

6. 现代主义(Modernism):指20世纪初的一种思潮和文学流派,以对现代社会的批判和对传统形式的挑战为特点,代表作家有弗吉尼亚·伍尔夫、詹姆斯·乔伊斯等。

7. 女性主义文学(Feminist Literature):指关注女性经验和性别平等的文学作品,代表作家有弗吉尼亚·伍尔夫、玛格丽特·阿特伍德等。

8. 后现代主义(Postmodernism):指二战后出现的一种思潮和文学流派,强调对现实的怀疑和对语言的游戏性,代表作家有萨缪尔·贝克特、艾里奥·卡尔维诺等。

9. 科幻文学(Science Fiction):指描写未来社会和科技发展的文学作品,代表作家有霍华德·菲利普斯·洛夫克拉夫特、艾萨克·阿西莫夫等。

英国文学7个时期 各自特点介绍

英国文学7个时期英国文学发端于中世纪,经历了古英语、中古英语、文艺复兴、17世纪、18世纪、19世纪、20 世纪文学 7 个时期,取得了举世瞩目的成就。

古英语文学英国在10世纪以前属于古英语时期,早期的凯尔特等部族及 5 世纪入侵的盎格鲁、撒克逊和朱特人,起初都没有留下书面文学。

6世纪末到7世纪末,由于肯特国王阿瑟尔伯特皈依基督教,该教僧侣开始以拉丁文著书写诗,其中以比德所著《英国人民宗教史》最有历史和文学价值。

9世纪,威塞克斯国王阿尔弗雷德为振兴文化,组织人力将各种拉丁文著作译成英语,并倡导以英语撰写《盎格鲁-撒克逊编年史》,其中包括有关盎格鲁-撒克逊和朱特人的英雄史诗《贝奥武甫》和《朱迪斯》,以及一些抒情诗、方言诗、谜语和宗教诗、宗教记述文、布道词。

中古英语文学 11世纪,随着诺曼人入侵,古英语渐渐演化为中古英语,文学上开始流行模仿法国的韵文体骑士传奇,其中以《高文骑士与绿衣骑士》最有艺术价值。

14世纪后半叶是中古英语发展的高峰,出现了似受古英语诗影响的口头韵体诗,最有名的长诗《农夫彼尔斯的幻想》,一般认为是教会人员朗兰德所写,以中世纪梦幻故事的形式探讨人间善恶,讽刺社会丑行,表达对贫苦农民的深切同情。

此时期国王查理第二当政,宫廷开始用盎格鲁-诺曼法语,王室贵族兴起赞助文人之风。

英国文学史上出现的第一位大诗人乔叟以其诗体短篇小说集《坎特伯雷故事集》和其他长短诗集成为英国文学的重要奠基人。

15世纪,有民间歌谣抄本流传至今,最有名的是关于绿林好汉罗宾汉的传说;马洛礼的散文小说《亚瑟王之死》为英国小说的雏形。

文艺复兴时期文学 16世纪中叶至17世纪初主要是伊丽莎白女王时代,英国开始文艺复兴运动。

学者纷纷翻译意大利和法国学术、文学名著并自行著述,以托马斯 ·莫尔(1477~1535)的《乌托邦》最有价值。

英国文艺复兴文学最突出的是诗歌和戏剧。

西德尼( 1554~1586 )的十四行诗、斯宾塞的《仙后》都是诗歌方面的代表作。

英国文学(诗人及其代表作)

英国文学一、古英语时期的英国文学(499-1066)1、贝奥武夫2、阿尔弗雷德大帝:英国散文之父二、中古英语时期的英国文学1、 allegory体非常盛行['?l?ɡ?ri] 寓言2、 Romance开始上升到一定的高度3、高文爵士和绿衣骑士4、 Willian Langlaud 《农夫皮尔斯的幻象》5、乔叟坎特伯雷故事集(英雄双韵体)6、托马斯.马洛礼《亚瑟王之死》三、文艺复兴时期的英国文学(伊丽莎白时代)(14-16世纪)1、托马斯.莫尔《乌托邦》2、 Thomas Wyatt 和Henry Howard引入sonnet3、 Philips Sidney 《The defense of Poesie》《阿卡迪亚》描述田园生活;现代长篇小说的先驱4、斯宾塞《仙后》诗人中的诗人;斯宾塞体诗节;5、莎士比亚:长篇叙事诗:《维纳斯和阿多尼斯》、《露克丝受辱记》四大悲剧:哈姆雷特、李尔王、奥赛罗、麦克白7、本.琼森风俗喜剧(comedy of manners)《人性互异》8、约翰.多恩“玄学派”诗歌创始人9、 George Herbert 玄学派诗圣10、弗朗西斯.培根现代科学和唯物主义哲学创始人之一《Essays》英国发展史上的里程碑《学术的推进》和《新工具》四、启蒙时期(18世纪)1、约翰、弥尔顿:《失乐园》、《为英国人民争辩》2、约翰、班扬:《天路历程》religious allegory3、约翰、德莱顿:英国新古典主义的杰出代表、桂冠诗人;《论戏剧诗》4、亚历山大.蒲柏:英国新古典主义诗歌的重要代表;英雄双韵体的使用达到登峰造极的使用;《田园组诗》是其最早田园诗歌代表作5、托马斯、格雷:感伤主义中墓园诗派的代表人物《墓园挽歌》6、威廉、布莱克:天真之歌、经验之歌;7、罗伯特、彭斯:苏格兰最杰出的农民诗人;8、 Richard Steel和Joseph Addison合作创办《The tatler》和《the spectator》9、 Samuel defoe 英国现实主义小说的奠基人之一;《鲁滨逊漂流记》;《铲除非国教徒的捷径》,仪表达自己的不满;10、Jonathan Swift 《一个小小的建议》;《格列佛游记》;《桶的故事》;11、Samuel Richardson 英国现代小说的创始人;帕米拉;克拉丽莎;查尔斯.格蓝迪森爵士的历史;12、Henry Fielding 英国现实主义小说理论的奠基人;《约瑟夫。

英国文学知识简单整理

一.古英语时期(Old English Literature 公元499—1066年)英国文学开山之作:头韵体诗歌(alliteration)《贝奥武甫》(Beowulf)(该作属于epic民族英雄史诗)开德蒙(Caedmon):《赞美诗》(Anthem)琴涅武甫(Cynewulf):《十字架之梦》(Dream of the Rood)比德(Bede):《英吉利人教会史》(Historia Ecclesiastica Gentis Anglorum)阿尔弗雷德大帝(King Alfred):《盎格鲁—撒克逊编年史》(Anglo-Saxon Chronicle),被誉为“英国散文之父”(Father of English Prose)二.中古英语时期(Medieval English Literature 公元1066年—15世纪)Romance (浪漫传奇) 《亚瑟王之死》头韵体诗歌:《高文爵士和绿衣骑士》(Sir Gawain and the Green Knight)英国民谣ballad:《罗宾汉名谣集》(The Robin Hood Ballads)威廉·兰格伦(William Langland):《农夫皮尔斯的幻想》(The Vision Concerning piers the Plowman)杰弗里·乔叟(Geoffrey Chaucer):英国中世纪最伟大的诗人,享有“英国诗歌之父”的美誉(Father of English Poetry)。

代表作:八音节(octosyllabic)英雄双韵体(heroic couplet)诗歌《坎特布雷故事集》(The Canterbury Tales).托马斯·马洛礼(Sir Thomas Malory):英国15世纪优秀的散文家,代表作为《亚瑟王之死》(Le Morte d’Arthur)三.文艺复兴时期(Renaissance 15世纪末—17世纪)托马斯·莫尔(Thomas More):伟大的人文主义者,代表作:《乌托邦》(Utopia),《国王爱德华五世悲戚的一生》(The painful Life of Edward Ⅴ).托马斯·魏厄特(Thomas Wyatt)和亨利·霍华德(Henry Howard)的十四行诗(Sonnet).前者将意大利十四行诗引入英国;后者在此基础上,发展了英国十四行诗歌。

英国文学的发展和影响

英国文学的发展和影响英国是一个文学强国,在欧洲文学圈子中拥有着至高的地位,其文学作品名扬世界,对全球文化产生了深远的影响。

本文将从英国文学的初期发展、英国文学在全球范围内的作用、以及一些具有代表性的英国文学作品的分析等方面来探讨英国文学的发展与影响。

英国文学的初期发展英国文学的起源可以追溯到中世纪,这个时期的英国文学主要是以散文和韵文为主,其中以抒情诗和史诗为最为著名。

布里顿传说中的亚瑟王故事便是中世纪英国文学中最著名的故事之一。

随着时间的推移和文化的发展,英国文学逐渐形成了自己的格局,进入了文艺复兴时期。

这个时期的英国文学以诗歌、小说等文学形式为主,并呈现出了我们所熟知的现代英国文学的初步雏形。

文艺复兴时期英国最重要的作品当数莎士比亚的剧本。

莎士比亚是英国文学史上最富盛名的艺术家之一,他的作品涵盖了人性、政治、宗教、爱情等多个方面,并深入影响了整个英国社会和文化。

他的名垂青史,成为了英国文学史上的一座重要的里程碑。

英国文学在全球范围内的作用英国文学在世界文学史上占据着极为重要的地位,并且其影响正在延续至今。

许多英国文学作品不仅在英国本国广受欢迎,也能够在全球范围内获得极高的评价和称誉。

英国文学作品以其深刻的思想和独特的艺术风格吸引了世界各地的读者,并对全球文化产生了深远的影响。

在世界文学史上,英国文学的作品涵盖范围非常广泛。

散文、小说、诗歌、戏剧等形式都在其中得到充分的发展和创新。

最著名的英国小说当属简·奥斯汀的名著《傲慢与偏见》、查尔斯·狄更斯的名著《雾都孤儿》和莎士比亚的名剧《哈姆雷特》。

这些作品不仅在英国本国广受赞誉,在全球范围内也广受好评。

有些作品甚至已经成为世界文学史上的经典之作,对世界文化产生了深远的影响。

英国文学在文化交流中也发挥着重要的作用。

其作品的翻译和传播对促进全球文化交流做出了巨大的贡献。

此外,英国文学的知名度和影响力也通过大量的翻译、出版和教学等方式传播到世界各地,成为国际文化交流中的重要桥梁。

英国文学的发展和特点分析

英国文学的发展和特点分析英国文学在历史上一直占据着重要的地位,它拥有丰富的文学传统和深厚的文化积淀,不断地催生出许多杰出的文学巨匠。

从莎士比亚到狄更斯、奥斯汀、毛姆,英国文学涵盖了古典、浪漫、现代主义等各种文学流派,且一直保持着旺盛的创作力量。

本文将全面分析英国文学的发展历程和独特特点。

一、中世纪文学的代表——狄德罗英国文学的起源可以追溯到中世纪时期,当时的英国处于四次文艺复兴之前的周期中,社会相对混乱,文化发展相对滞后。

狄德罗是英国中世纪文学的代表,他的杰作《坎特伯雷故事集》被视为中世纪欧洲文学的重要代表作之一。

它以讲述七个巡礼者的故事为主线,描绘了当时社会各个阶层的生动形象,丰富了英国社会生活的多样性。

除此之外,狄德罗的诗歌也给后世留下了极大的影响,他的作品在中世纪英国文学中占有重要地位。

二、文艺复兴时期的代表——莎士比亚莎士比亚被誉为英国文学史上的巨匠,在英国文学的发展历程中占有重要地位。

他的作品涉及各个领域,包括戏剧、史诗、散文等等,其中最为著名的作品莫过于《哈姆雷特》、《罗密欧与朱丽叶》、《李尔王》等。

他的作品独具特色,具有精湛的语言技巧和鲜明的人物形象,对文学创作乃至整个英国文化产生了深远的影响。

在莎士比亚之后,文艺复兴时期的其它文学家,如马洛、斯宾塞、培根等人也为英国文学的发展做出了杰出的贡献。

三、18-19世纪的文学成果——奥斯汀、狄更斯18-19世纪是英国文学发展的黄金时期,文学家们在这个时期不断地开创出新的文学流派,创作出了许多不朽的文学作品。

简·奥斯汀以其细腻的刻画和幽默的笔调而著名,她的《傲慢与偏见》、《理智与感性》受到了广泛的追捧。

查尔斯·狄更斯则以其对于贫穷阶层及其社会真相的关注而著名,他的《雾都孤儿》、《双城记》等作品更是展现了当时英国社会的面貌,反映了社会的不公和黑暗面。

四、现代主义文学——毛姆20世纪初,英国文学开始进入现代主义文学的时期。

毛姆是英国现代主义文学的代表性人物之一,他的作品《月亮与六便士》、《人性之善谈》等著作探讨了人性、社会及道德的种种问题。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

Novel AnalysisALTHOUGH Bertha Young was thirty she still had moments like this when she wanted to run instead of walk, to take dancing steps on and off the pavement, to bowl a hoop, to throw something up in the air and catch it again, or to stand still and laugh at–nothing–at nothing, simply.What can you do if you are thirty and, turning the corner of your own street, you are overcome, suddenly by a feeling of bliss–absolute bliss!–as though you'd suddenly swallowed a bright piece of that late afternoon sun and it burned in your bosom, sending out a little shower of sparks into every particle, into every finger and toe? . . .Oh, is there no way you can express it without being "drunk and disorderly" ? How idiotic civilization is! Why be given a body if you have to keep it shut up in a case like a rare, rare fiddle?"No, that about the fiddle is not quite what I mean," she thought, running up the steps and feeling in her bag for the key–she'd forgotten it, as usual––and rattling the letter-box. "It's not what I mean, because–Thank you, Mary"––she went into the hall. "Is nurse back?""Yes, M'm.""And has the fruit come?""Yes, M'm. Everything's come.""Bring the fruit up to the dining-room, will you? I'll arrange it before I go upstairs."It was dusky in the dining-room and quite chilly. But all the same Bertha threw off her coat; she could not bear the tight clasp of it another moment, and the cold air fell on her arms.But in her bosom there was still that bright glowing place––that shower of little sparks coming from it. It was almost unbearable. She hardly dared to breathe for fear of fanning it higher, and yet she breathed deeply, deeply. She hardly dared to look into the cold mirror––but she did look, and it gave her back a woman, radiant, with smiling, trembling lips, with big, dark eyes and an air of listening, waiting for something . . . divine to happen . . . that she knew must happen . . . infallibly.Mary brought in the fruit on a tray and with it a glass bowl, and a blue dish, very lovely, with a strange sheen on it as though it had been dipped in milk."Shall I turn on the light, M'm?""No, thank you. I can see quite well."There were tangerines and apples stained with strawberry pink. Some yellow pears, smooth as silk, some white grapes covered with a silver bloom and a big cluster of purple ones. These last she had bought to tone in with the new dining-room carpet. Yes, that did sound rather far-fetched and absurd, but it was really why she had bought them. She had thought in the shop: "I must have some purple ones to bring the carpet up to the table." And it had seemed quite sense at the time.When she had finished with them and had made two pyramids of these bright round shapes, she stood away from the table to get the effect––and it really was most curious. For the dark table seemedto melt into the dusky light and the glass dish and the blue bowl to float in the air. This, of course, in her present mood, was so incredibly beautiful. . . . She began to laugh."No, no. I'm getting hysterical." And she seized her bag and coat and ran upstairs to the nursery.Nurse sat at a low table giving Little B her supper after her bath. The baby had on a white flannel gown and a blue woolen jacket, and her dark, fine hair was brushed up into a funny little peak. She looked up when she saw her mother and began to jump."Now, my lovey, eat it up like a good girl," said nurse, setting her lips in a way that Bertha knew, and that meant she had come into the nursery at another wrong moment."Has she been good, Nanny?""She's been a little sweet all the afternoon," whispered Nanny. "We went to the park and I sat down on a chair and took her out of the pram and a big dog came along and put its head on my knee and she clutched its ear, tugged it. Oh, you should have seen her."Bertha wanted to ask if it wasn't rather dangerous to let her clutch at a strange dog's ear. But she did not dare to. She stood watching them, her hands by her side, like the poor little girl in front of the rich girl with the doll.The baby looked up at her again, stared, and then smiled so charmingly that Bertha couldn't help crying:"Oh, Nanny, do let me finish giving her her supper while you put the bath things away."Well, M'm, she oughtn't to be changed hands while she's eating," said Nanny, still whispering. "It unsettles her; it's very likely to upset her."How absurd it was. Why have a baby if it has to be kept–not in a case like a rare, rare fiddle––but in another woman's arms?"Oh, I must!" said she.V ery offended, Nanny handed her over."Now, don't excite her after her supper. You know you do, M'm. And I have such a time with her after!"Thank heaven! Nanny went out of the room with the bath towels."Now I've got you to myself, my little precious," said Bertha, as the baby leaned against her.She ate delightfully, holding up her lips for the spoon and then waving her hands. Sometimes she wouldn't let the spoon go; and sometimes, just as Bertha had filled it, she waved it away to the four winds.When the soup was finished Bertha turned round to the fire. "You're nice––you're very nice!" said she, kissing her warm baby. "I'm fond of you. I like you."And indeed, she loved Little B so much––her neck as she bent forward, her exquisite toes as they shone transparent in the firelight––that all her feeling of bliss came back again, and again she didn't know how to express it––what to do with it."You're wanted on the telephone," said Nanny, coming back in triumph and seizing her Little B.Down she flew. It was Harry."Oh, is that you, Ber? Look here. I'll be late. I'll take a taxi and come along as quickly as I can, but get dinner put back ten minutes––will you? All right?""Yes, perfectly. Oh, Harry!""Yes?"What had she to say? She'd nothing to say. She only wanted to get in touch with him for a moment. She couldn't absurdly cry: "Hasn't it been a divine day!""What is it?" rapped out the little voice."Nothing. Entendu," said Bertha, and hung up the receiver, thinking how much more than idiotic civilization was.They had people coming to dinner. The Norman Knights––a very sound couple––he was about to start a theatre, and she was awfully keen on interior decoration, a young man, Eddie Warren, who had just published a little book of poems and whom everybody was asking to dine, and a "find" of Bertha's called Pearl Fulton. What Miss Fulton did, Bertha didn't know. They had met at the club and Bertha had fallen in love with her, as she always did fall in love with beautiful women who had something strange about them.The provoking thing was that, though they had been about together and met a number of times and really talked, Bertha couldn't make her out. Up to a certain point Miss Fulton was rarely, wonderfully frank, but the certain point was there, and beyond that she would not go.Was there anything beyond it? Harry said "No." V oted her dullish, and "cold like all blonde women, with a touch, perhaps, of anaemia of the brain." But Bertha wouldn't agree with him; not yet, at any rate."No, the way she has of sitting with her head a little on one side, and smiling, has something behind it, Harry, and I must find out what that something is.""Most likely it's a good stomach," answered Harry.He made a point of catching Bertha's heels with replies of that kind . . . "liver frozen, my dear girl," or "pure flatulence," or "kidney disease," . . . and so on. For some strange reason Bertha liked this, and almost admired it in him very much.She went into the drawing-room and lighted the fire; then, picking up the cushions, one by one, that Mary had disposed so carefully, she threw them back on to the chairs and the couches. That made all the difference; the room came alive at once. As she was about to throw the last one she surprised herself by suddenly hugging it to her, passionately, passionately. But it did not put out the fire in her bosom. Oh, on the contrary!The windows of the drawing-room opened on to a balcony overlooking the garden. At the far end, against the wall, there was a tall, slender pear tree in fullest, richest bloom; it stood perfect, as thoughbecalmed against the jade-green sky. Bertha couldn't help feeling, even from this distance, that it had not a single bud or a faded petal. Down below, in the garden beds, the red and yellow tulips, heavy with flowers, seemed to lean upon the dusk. A grey cat, dragging its belly, crept across the lawn, and a black one, its shadow, trailed after. The sight of them, so intent and so quick, gave Bertha a curious shiver."What creepy things cats are!" she stammered, and she turned away from the window and began walking up and down. . . .How strong the jonquils smelled in the warm room. Too strong? Oh, no. And yet, as though overcome, she flung down on a couch and pressed her hands to her eyes."I'm too happy––too happy!" she murmured.And she seemed to see on her eyelids the lovely pear tree with its wide open blossoms as a symbol of her own life.Really–really–she had everything. She was young. Harry and she were as much in love as ever, and they got on together splendidly and were really good pals. She had an adorable baby. They didn't have to worry about money. They had this absolutely satisfactory house and garden. And friends––modern, thrilling friends, writers and painters and poets or people keen on social questions–just the kind of friends they wanted. And then there were books, and there was music, and she had found a wonderful little dressmaker, and they were going abroad in the summer, and their new cook made the most superb omelettes. . . ."I'm absurd. Absurd!" She sat up; but she felt quite dizzy, quite drunk. It must have been the spring.Yes, it was the spring. Now she was so tired she could not drag herself upstairs to dress.A white dress, a string of jade beads, green shoes and stockings. It wasn't intentional. She had thought of this scheme hours before she stood at the drawing-room window.Her petals rustled softly into the hall, and she kissed Mrs. Norman Knight, who was taking off the most amusing orange coat with a procession of black monkeys round the hem and up the fronts." . . . Why! Why! Why is the middle-class so stodgy–so utterly without a sense of humour! My dear, it's only by a fluke that I am here at all–Norman being the protective fluke. For my darling monkeys so upset the train that it rose to a man and simply ate me with its eyes. Didn't laugh–wasn't amused–that I should have loved. No, just stared–and bored me through and through.""But the cream of it was," said Norman, pressing a large tortoiseshell-rimmed monocle into his eye, "you don't mind me telling this, Face, do you?" (In their home and among their friends they called each other Face and Mug.) "The cream of it was when she, being full fed, turned to the woman beside her and said: 'Haven't you ever seen a monkey before?'""Oh, yes!" Mrs. Norman Knight joined in the laughter. "Wasn't that too absolutely creamy?"And a funnier thing still was that now her coat was off she did look like a very intelligentmonkey––who had even made that yellow silk dress out of scraped banana skins. And her amber ear-rings: they were like little dangling nuts."This is a sad, sad fall!" said Mug, pausing in front of Little B's perambulator. "When the perambulator comes into the hall––" and he waved the rest of the quotation away.The bell rang. It was lean, pale Eddie Warren (as usual) in a state of acute distress."It is the right house, isn't it?" he pleaded."Oh, I think so––I hope so," said Bertha brightly."I have had such a dreadful experience with a taxi-man; he was most sinister. I couldn't get him to stop. The more I knocked and called the faster he went. And in the moonlight this bizarre figure with the flattened head crouching over the little wheel . . . "He shuddered, taking off an immense white silk scarf. Bertha noticed that his socks were white, too–most charming."But how dreadful!" she cried."Yes, it really was," said Eddie, following her into the drawing-room. "I saw myself driving through Eternity in a timeless taxi."He knew the Norman Knights. In fact, he was going to write a play for N.K. when the theatre scheme came off."Well, Warren, how's the play?" said Norman Knight, dropping his monocle and giving his eye a moment in which to rise to the surface before it was screwed down again.And Mrs. Norman Knight: "Oh, Mr. Warren, what happy socks?""I am so glad you like them," said he, staring at his feet. "They seem to have got so much whiter since the moon rose." And he turned his lean sorrowful young face to Bertha. "There is a moon, you know."She wanted to cry: "I am sure there is––often––often!"He really was a most attractive person. But so was Face, crouched before the fire in her banana skins, and so was Mug, smoking a cigarette and saying as he flicked the ash: "Why doth the bridegroom tarry?""There he is, now."Bang went the front door open and shut. Harry shouted: "Hullo, you people. Down in five minutes." And they heard him swarm up the stairs. Bertha couldn't help smiling; she knew how he loved doing things at high pressure. What, after all, did an extra five minutes matter? But he would pretend to himself that they mattered beyond measure. And then he would make a great point of coming into the drawing-room, extravagantly cool and collected.Harry had such a zest for life. Oh, how she appreciated it in him. And his passion for fighting––for seeking in everything that came up against him another test of his power and of his courage–that, too, she understood. Even when it made him just occasionally, to other people, whodidn't know him well, a little ridiculous perhaps. . . . For there were moments when he rushed into battle where no battle was. . . . She talked and laughed and positively forgot until he had come in (just as she had imagined) that Pearl Fulton had not turned up."I wonder if Miss Fulton has forgotten?""I expect so," said Harry. "Is she on the 'phone?""Ah! There's a taxi, now." And Bertha smiled with that little air of proprietorship that she always assumed while her women finds were new and mysterious. "She lives in taxis.""She'll run to fat if she does," said Harry coolly, ringing the bell for dinner. "Frightful danger for blonde women.""Harry–don't!" warned Bertha, laughing up at him.Came another tiny moment, while they waited, laughing and talking, just a trifle too much at their ease, a trifle too unaware. And then Miss Fulton, all in silver, with a silver fillet binding her pale blonde hair, came in smiling, her head a little on one side."Am I late?""No, not at all," said Bertha. "Come along." And she took her arm and they moved into the dining-room.What was there in the touch of that cool arm that could fan–fan–start blazing–blazing–the fire of bliss that Bertha did not know what to do with?Miss Fulton did not look at her; but then she seldom did look at people directly. Her heavy eyelids lay upon her eyes and the strange half-smile came and went upon her lips as though she lived by listening rather than seeing. But Bertha knew, suddenly, as if the longest, most intimate look had passed between them––as if they had said to each other: "You too?"–that Pearl Fulton, stirring the beautiful red soup in the grey plate, was feeling just what she was feeling.And the others? Face and Mug, Eddie and Harry, their spoons rising and falling––dabbing their lips with their napkins, crumbling bread, fiddling with the forks and glasses and talking."I met her at the Alpha show––the weirdest little person. She'd not only cut off her hair, but she seemed to have taken a dreadfully good snip off her legs and arms and her neck and her poor little nose as well.""Isn't she very liée with Michael Oat?""The man who wrote Love in False Teeth? ""He wants to write a play for me. One act. One man. Decides to commit suicide. Gives all the reasons why he should and why he shouldn't. And just as he has made up his mind either to do it or not to do it–curtain. Not half a bad idea.""What's he going to call it––'Stomach Trouble' ?""I think I've come across the same idea in a little French review, quite unknown in England."No, they didn't share it. They were dears–dears–and she loved having them there, at her table,and giving them delicious food and wine. In fact, she longed to tell them how delightful they were, and what a decorative group they made, how they seemed to set one another off and how they reminded her of a play by Tchekof!Harry was enjoying his dinner. It was part of his––well, not his nature, exactly, and certainly not his pose––his––something or other––to talk about food and to glory in his "shameless passion for the white flash of the lobster" and "the green of pistachio ices––green and cold like the eyelids of Egyptian dancers."When he looked up at her and said: "Bertha, this is a very admirable soufflée! " she almost could have wept with child-like pleasure.Oh, why did she feel so tender towards the whole world tonight? Everything was good––was right. All that happened seemed to fill again her brimming cup of bliss.And still, in the back of her mind, there was the pear tree. It would be silver now, in the light of poor dear Eddie's moon, silver as Miss Fulton, who sat there turning a tangerine in her slender fingers that were so pale a light seemed to come from them.What she simply couldn't make out––what was miraculous– was how she should have guessed Miss Fulton's mood so exactly and so instantly. For she never doubted for a moment that she was right, and yet what had she to go on? Less than nothing."I believe this does happen very, very rarely between women. Never between men," thought Bertha. "But while I am making the coffee in the drawing-room perhaps she will 'give a sign' "What she meant by that she did not know, and what would happen after that she could not imagine.While she thought like this she saw herself talking and laughing. She had to talk because of her desire to laugh."I must laugh or die."But when she noticed Face's funny little habit of tucking something down the front of her bodice––as if she kept a tiny, secret hoard of nuts there, too––Bertha had to dig her nails into her hands–so as not to laugh too much.It was over at last. And: "Come and see my new coffee machine," said Bertha."We only have a new coffee machine once a fortnight," said Harry. Face took her arm this time; Miss Fulton bent her head and followed after.The fire had died down in the drawing-room to a red, flickering "nest of baby phoenixes," said Face."Don't turn up the light for a moment. It is so lovely." And down she crouched by the fire again. She was always cold . . . "without her little red flannel jacket, of course," thought Bertha.At that moment Miss Fulton "gave the sign.""Have you a garden?" said the cool, sleepy voice.This was so exquisite on her part that all Bertha could do was to obey. She crossed the room, pulled the curtains apart, and opened those long windows."There!" she breathed.And the two women stood side by side looking at the slender, flowering tree. Although it was so still it seemed, like the flame of a candle, to stretch up, to point, to quiver in the bright air, to grow taller and taller as they gazed––almost to touch the rim of the round, silver moon.How long did they stand there? Both, as it were, caught in that circle of unearthly light, understanding each other perfectly, creatures of another world, and wondering what they were to do in this one with all this blissful treasure that burned in their bosoms and dropped, in silver flowers, from their hair and hands?For ever––for a moment? And did Miss Fulton murmur: "Yes. Just that." Or did Bertha dream it?Then the light was snapped on and Face made the coffee and Harry said: "My dear Mrs. Knight, don't ask me about my baby. I never see her. I shan't feel the slightest interest in her until she has a lover," and Mug took his eye out of the conservatory for a moment and then put it under glass again and Eddie Warren drank his coffee and set down the cup with a face of anguish as though he had drunk and seen the spider."What I want to do is to give the young men a show. I believe London is simply teeming with first-chop, unwritten plays. What I want to say to 'em is: 'Here's the theatre. Fire ahead.'""You know, my dear, I am going to decorate a room for the Jacob Nathans. Oh, I am so tempted to do a fried-fish scheme, with the backs of the chairs shaped like frying-pans and lovely chip potatoes embroidered all over the curtains.""The trouble with our young writing men is that they are still too romantic. You can't put out to sea without being seasick and wanting a basin. Well, why won't they have the courage of those basins?""A dreadful poem about a girl who was violated by a beggar without a nose in a little wood. . . ."Miss Fulton sank into the lowest, deepest chair and Harry handed round the cigarettes.From the way he stood in front of her shaking the silver box and saying abruptly: "Egyptian? Turkish? Virginian? They're all mixed up," Bertha realized that she not only bored him; he really disliked her. And she decided from the way Miss Fulton said: "No, thank you, I won't smoke," that she felt it, too, and was hurt."Oh, Harry, don't dislike her. You are quite wrong about her. She's wonderful, wonderful. And, besides, how can you feel so differently about someone who means so much to me. I shall try to tell you when we are in bed tonight what has been happening. What she and I have shared."At those last words something strange and almost terrifying darted into Bertha's mind. And this something blind and smiling whispered to her: "Soon these people will go. The house will be quiet––quiet. The lights will be out. And you and he will be alone together in the dark room––thewarm bed. . . . "She jumped up from her chair and ran over to the piano."What a pity someone does not play!" she cried. "What a pity somebody does not play."For the first time in her life Bertha Young desired her husband. Oh, she'd loved him––she'd been in love with him, of course, in every other way, but just not in that way. And equally, of course, she'd understood that he was different. They'd discussed it so often. It had worried her dreadfully at first to find that she was so cold, but after a time it had not seemed to matter. They were so frank with each other––such good pals. That was the best of being modern.But now––ardently! ardently! The word ached in her ardent body! Was this what that feeling of bliss had been leading up to? But then, then–– "My dear," said Mrs. Norman Knight, "you know our shame. We are the victims of time and train. We live in Hampstead. It's been so nice.""I'll come with you into the hall," said Bertha. "I loved having you. But you must not miss the last train. That's so awful, isn't it?""Have a whisky, Knight, before you go?" called Harry."No, thanks, old chap."Bertha squeezed his hand for that as she shook it."Good night, good-bye," she cried from the top step, feeling that this self of hers was taking leave of them for ever.When she got back into the drawing-room the others were on the move." . . . Then you can come part of the way in my taxi.""I shall be so thankful not to have to face another drive alone after my dreadful experience.""You can get a taxi at the rank just at the end of the street. You won't have to walk more than a few yards.""That's a comfort. I'll go and put on my coat."Miss Fulton moved towards the hall and Bertha was following when Harry almost pushed past."Let me help you."Bertha knew that he was repenting his rudeness––she let him go. What a boy he was in some ways––so impulsive––so––simple.And Eddie and she were left by the fire."I wonder if you have seen Bilks' new poem called Table d'Hôte," said Eddie softly. "It's so wonderful. In the last Anthology. Have you got a copy? I'd so like to show it to you. It begins with an incredibly beautiful line: 'Why Must it Always be Tomato Soup?'""Yes," said Bertha. And she moved noiselessly to a table opposite the drawing-room door and Eddie glided noiselessly after her. She picked up the little book and gave it to him; they had not made a sound.While he looked it up she turned her head towards the hall. And she saw . . . Harry with MissFulton's coat in his arms and Miss Fulton with her back turned to him and her head bent. He tossed the coat away, put his hands on her shoulders and turned her violently to him. His lips said: "I adore you," and Miss Fulton laid her moonbeam fingers on his cheeks and smiled her sleepy smile. Harry's nostrils quivered; his lips curled back in a hideous grin while he whispered: "Tomorrow," and with her eyelids Miss Fulton said: "Yes.""Here it is," said Eddie. "'Why Must it Always be Tomato Soup?' It's so deeply true, don't you feel? Tomato soup is so dreadfully eternal.""If you prefer," said Harry's voice, very loud, from the hall, "I can phone you a cab to come to the door.""Oh, no. It's not necessary," said Miss Fulton, and she came up to Bertha and gave her the slender fingers to hold."Good-bye. Thank you so much.""Good-bye," said Bertha.Miss Fulton held her hand a moment longer."Your lovely pear tree!" she murmured.And then she was gone, with Eddie following, like the black cat following the grey cat."I'll shut up shop," said Harry, extravagantly cool and collected."Your lovely pear tree––pear tree––pear tree!"Bertha simply ran over to the long windows."Oh, what is going to happen now?" she cried.But the pear tree was as lovely as ever and as full of flower and as still.要求:1、6人一组完成分析,自愿组合;2、用英文(Times New Roman 字体)从小说的六要素入手逐个分析:故事、情节、背景、人物(特别是主人公的性格)、主题和叙事视角。