2-宏大理论《社会学的想象力》-社会学考研必备课件

《社会学的想像力》课件

采用定性和定量方法,包括问卷调查、实地观察和深度访谈等。

想像力的重要性

1 什么是想像力

指个体或集体能够创造性地构建和演绎未曾亲身经历的事物的能力。

2 想像力在社会学中的应用

帮助社会学家更好地理解社会现象、推断可能的后果,并提出新的研究问题。

3 想像力对社会变革的作用

通过激发个体和社会的创造力,推动社会变迁和创新。

《社会学的想像力》PPT 课件

社会学的想像力课程介绍社会学的基本概念和研究方法,探讨了想像力在社 会学中的重要性以及两者的结合带来的创新和变革。

社会学概述

什么是社会学

探讨社会现象和人类行为的科学研究领域,关注社会结构、社会关系和社会变迁。

社会学的研究对象

社会学研究的范围包括家庭、教育、政治、经济等各个社会领域。

怎样发挥社会学的想像力

培养创造力和批判思维,多角度思考问题,开 放心智以接纳新的想法。

参考文献

• 王振邦,社会学概论 • 李银河,一天世界 • 大卫·麦克拉克林,想像的力量

社会学和想像力的结合

1

想像力在社会学研究中的价值

提供新的理论框架和观点,帮助解决社会问题。

2

以想像力观察社会问题

发掘社会现象背后的隐含动机和潜在影响。

3

ቤተ መጻሕፍቲ ባይዱ

想像力作为社会变革的推动力量

促进社会创新和改革,推动社会向更好的方向发展。

结论

社会学的想像力为什么重要

通过想像力,我们可以超越现实,创造新的可 能性,推动社会的创新与变革。

宏大理论-社会学的想象力-社会学考研必备课件

符号互动论认为人类社会的互动和沟 通是有规律的、可预测的,并且可以 通过科学的方法进行研究和解释。

符号互动论

详细描述

符号互动论认为人类社会的互动和沟通是有规律的、可预测的,并且可以通过科学的方法 进行研究和解释。在社会学中,符号互动论强调对社会互动和沟通进行科学的研究和分析 ,探究它们的规律和机制,以更好地理解社会的运作和发展。

总结词

冲突理论认为社会的发展和变迁是由 社会中的不平等、冲突和斗争所推动 的,而不是由某种超自然力量所决定 的。

详细描述

冲突理论认为社会的发展和变迁是由 社会中的不平等、冲突和斗争所推动 的,而不是由某种超自然力量所决定 的。在社会学中,冲突理论强调对社 会的发展和变迁进行深入的研究和分 析,探究它们的原因和影响,以更好 地理解社会的运作和发展。

总结词

功能主义理论认为社会制度和文化现 象的变迁和演化是有规律的、可预测 的,并且可以通过科学的方法进行研 究和解释。

详细描述

功能主义理论认为社会制度和文化现 象的变化是有规律的、可预测的,可 以通过科学的方法进行研究和解释。 在社会学中,功能主义理论强调对社 会制度和文化现象进行科学的研究和 分析,探究它们的变化规律和演化机 制,以更好地理解社会的运作和发展 。

特点

具有全局性、综合性、抽象性和 普遍性,能够提供对社会现象的 深层次理解和解释,具有广泛的 适用性和影响力。

宏大理论与微观理论的关系

相互补充

宏大理论关注宏观层面的社会现象, 而微观理论则关注个体和较小群体的 行为和互动。两者相互补充,共同构 成对社会现象的全面理解。

相互影响

宏大理论可以为微观理论提供指导和 框架,而微观理论则可以通过实证研 究验证和修正宏大理论。两者在互动 中共同发展。

8 论治学之道《社会学的想象力》 社会学考研必备课件

一般来说,正确的选题至少应该符合以下三个条

件中的一个条件。一是,研究对象是一种没有被

其他人研究过的新的社会现象;二是,社会现象

已经被研究过,但可以采用一种新的理论或是新

的方法重新进行解释和分析;三是,曾经研究过 的社会现象,但现实生活发生了很大变化,需要 重新进行调查,客观描述这一现象的基本状况, 并在此基础上进行解释和分析。

重复4个步骤:对主题、论点或思考领域的总体认识,以及自我感

觉必须思考的一些基本原理和定义;注意定义和原理间的逻辑关系, 以建立起微型的初级模型;由于遗漏必要元素、错误或含糊的术语 和定义,以及对某部分及其逻辑外延的过分强调而导致的错误观点, 予以删除;反复陈述遗留的对事实的质疑。

通过阅读、分析他人的理论,设计一些理想化的研究,再仔细阅读

学术档案,这是勾勒具体研究的方法。

第三,如何激发社会学的想象力。

激发社会学想象力的途径:

1、具体的层次上,重组学术档案――清理看

来毫无关系的文件夹,把其中的内容混在一起, 重新分类。但目前我能做的只有“将有关问题 记在心上,尝试被动地去接受未曾预见到的和 非计划中的联系”,因为没有学术档案。

的审视它、解释它。 学术档案——写日记。

写什么: 日常生活的“副产品”,无意间听到的街谈巷议的片断,

梦中所得; 阅读笔记(评论、摘要、书目、课题概要)。 怎么写: 建立各类主题;明确自己的学术目标。学术档案会按照几 个大的研究题目进行编排,在几个大题目之下,又有许多 年复一年不断改变的小题目。 读他人著作的体验和个人生活体验赋之以框架。 读书有两种读法:阅读全书,把握作者论证的结构,并相 应做出笔记;根据自己的学术研究和兴趣,有选择地阅读 书中的某些部分。 意义何在: 思想一旦被记录下来,就不只会给更直接的体验添些思 想意义,还可能激发出更为系统的思考。 养成练笔的习惯,提高表达能力。

社会学的想象力

The Sociological ImaginationChapter One: The PromiseC. Wright Mills (1959)Nowadays people often feel that their private lives are a series of traps. They sense that within their everyday worlds, they cannot overcome their troubles, and in this feeling, they are often quite correct. What ordinary people are directly aware of and what they try to do are bounded by the private orbits in which they live; their visions and their powers are limited to the close-up scenes of job, family, neighborhood; in other milieux, they move vicariously and remain spectators. And the more aware they become, however vaguely, of ambitions and of threats which transcend their immediate locales, the more trapped they seem to feel.Underlying this sense of being trapped are seemingly impersonal changes in the very structure of continent-wide societies. The facts of contemporary history are also facts about the success and the failure of individual men and women. When a society is industrialized, a peasant becomes a worker; a feudal lord is liquidated or becomes a businessman. When classes rise or fall, a person is employed or unemployed; when the rate of investment goes up or down, a person takes new heart or goes broke. When wars happen, an insurance salesperson becomes a rocket launcher; a store clerk, a radar operator; a wife or husband lives alone; a child grows up without a parent. Neither the life of an individual nor the history of a society can be understood without understanding both.Yet people do not usually define the troubles they endure in terms of historical change and institutional contradiction. The well-being they enjoy, they do not usually impute to the big ups and downs of the societies in which they live. Seldom aware of the intricate connection between the patterns of their own lives and the course of world history, ordinary people do not usually know what this connection means for the kinds of people they are becoming and for the kinds of history-making in which they might take part. They do not possess the quality of mind essentialto grasp the interplay of individuals and society, of biography and history, of self and world. They cannot cope with their personal troubles in such ways as to control the structural transformations that usually lie behind them.Surely it is no wonder. In what period have so many people been so totally exposed at so fast a pace to such earthquakes of change? That Americans have not known such catastrophic changes as have the men and women of other societies is due to historical facts that are now quickly becoming 'merely history.' The history that now affects every individual is world history. Within this scene and this period, in the course of a single generation, one sixth of humankind is transformed from all that is feudal and backward into all that is modern, advanced, and fearful. Political colonies are freed; new and less visible forms of imperialism installed. Revolutions occur; people feel the intimate grip of new kinds of authority. Totalitarian societies rise, and are smashed to bits - or succeed fabulously. After two centuries of ascendancy, capitalism is shownup as only one way to make society into an industrial apparatus. After two centuries of hope, even formal democracy is restricted to a quite small portion of mankind. Everywhere in the underdeveloped world, ancient ways of life are broken up and vague expectations become urgent demands. Everywhere in the overdeveloped world, the means of authority and of violence become total in scope and bureaucratic in form. Humanity itself now lies before us, the super-nation at either pole concentrating its most coordinated and massive efforts upon the preparationof World War Three.The very shaping of history now outpaces the ability of people to orient themselves in accordance with cherished values. And which values? Even when they do not panic, people often sense that older ways of feeling and thinking have collapsed and that newer beginnings are ambiguous to the point of moral stasis. Is it any wonder that ordinary people feel they cannot cope with the larger worlds with which they are so suddenly confronted? That they cannot understand the meaning of their epoch for their own lives? That - in defense of selfhood - they become morally insensible, trying to remain altogether private individuals? Is it any wonder that they come to be possessed by a sense of the trap?It is not only information that they need - in this Age of Fact, information often dominates their attention and overwhelms their capacities to assimilate it. It is not only the skills of reason that they need - although their struggles to acquire these often exhaust their limited moral energy. What they need, and what they feel they need, is a quality of mind that will help them to use information and to develop reason in order to achieve lucid summations of what is going on in the world and of what may be happening within themselves. It is this quality, I am going to contend, that journalists and scholars, artists and publics, scientists and editors are coming to expect of what may be called the sociological imagination.The sociological imagination enables its possessor to understand the larger historical scene in terms of its meaning for the inner life and the external career of a variety of individuals. It enables him to take into account how individuals, in the welter of their daily experience, often become falsely conscious of their social positions. Within that welter, the framework of modern society is sought, and within that framework the psychologies of a variety of men and women are formulated. By such means the personal uneasiness of individuals is focused upon explicit troubles and the indifference of publics is transformed into involvement with public issues.The first fruit of this imagination - and the first lesson of the social science that embodies it - is the idea that the individual can understand her own experience and gauge her own fate only by locating herself within her period, that she can know her own chances in life only by becoming aware of those of all individuals in her circumstances. In many ways it is a terrible lesson; in many ways a magnificent one. We do not know the limits of humans capacities for supremeeffort or willing degradation, for agony or glee, for pleasurable brutality or the sweetness of reason. But in our time we have come to know that the limits of 'human nature' are frighteningly broad. We have come to know that every individual lives, from one generation to the next, in some society; that he lives out a biography, and lives it out within some historical sequence. By the fact of this living, he contributes, however minutely, to the shaping of this society and to the course of its history, even as he is made by society and by its historical push and shove.The sociological imagination enables us to grasp history and biography and the relations between the two within society. That is its task and its promise. To recognize this task and this promise is the mark of the classic social analyst. It is characteristic of Herbert Spencer - turgid, polysyllabic, comprehensive; of E. A. Ross - graceful, muckraking, upright; of Auguste Comte and Emile Durkheim; of the intricate and subtle Karl Mannheim. It is the quality of all that is intellectually excellent in Karl Marx; it is the clue to Thorstein Veblen's brilliant and ironic insight, to Joseph Schumpeter's many-sided constructions of reality; it is the basis of the psychological sweep of W. E. H. Lecky no less than of the profundity and clarity of Max Weber. And it is the signal of what is best in contemporary studies of people and society.No social study that does not come back to the problems of biography, of history and of their intersections within a society has completed its intellectual journey. Whatever the specific problems of the classic social analysts, however limited or however broad the features of social reality they have examined, those who have been imaginatively aware of the promise of their work have consistently asked three sorts of questions:(1) What is the structure of this particular society as a whole? What are its essential components, and how are they related to one another? How does it differ from other varieties of social order? Within it, what is the meaning of any particular feature for its continuance and for its change? (2) Where does this society stand in human history? What are the mechanics by which it is changing? What is its place within and its meaning for the development of humanity as a whole? How does any particular feature we are examining affect, and how is it affected by, the historical period in which it moves? And this period - what are its essential features? How does it differ from other periods? What are its characteristic ways of history-making?(3) What varieties of men and women now prevail in this society and in this period? And what varieties are coming to prevail? In what ways are they selected and formed, liberated and repressed, made sensitive and blunted? What kinds of `human nature' are revealed in the conduct and character we observe in this society in this period? And what is the meaning for 'human nature' of each and every feature of the society we are examining?Whether the point of interest is a great power state or a minor literary mood, a family, a prison, a creed - these are the kinds of questions the best social analysts have asked. They are the intellectual pivots of classic studies of individuals in society - and they are the questions inevitably raised by any mind possessing the sociological imagination. For that imagination isthe capacity to shift from one perspective to another - from the political to the psychological; from examination of a single family to comparative assessment of the national budgets of the world; from the theological school to the military establishment; from considerations of an oil industry to studies of contemporary poetry. It is the capacity to range from the most impersonal and remote transformations to the most intimate features of the human self - and to see the relations between the two. Back of its use there is always the urge to know the social and historical meaning of the individual in the society and in the period in which she has her quality and her being.That, in brief, is why it is by means of the sociological imagination that men and women now hope to grasp what is going on in the world, and to understand what is happening in themselves as minute points of the intersections of biography and history within society. In large part, contemporary humanity's self-conscious view of itself as at least an outsider, if not a permanent stranger, rests upon an absorbed realization of social relativity and of the transformative power of history. The sociological imagination is the most fruitful form of this self-consciousness. Byits use people whose mentalities have swept only a series of limited orbits often come to feel as if suddenly awakened in a house with which they had only supposed themselves to be familiar. Correctly or incorrectly, they often come to feel that they can now provide themselves with adequate summations, cohesive assessments, comprehensive orientations. Older decisions that once appeared sound now seem to them products of a mind unaccountably dense. Their capacity for astonishment is made lively again. They acquire a new way of thinking, they experience a transvaluation of values: in a word, by their reflection and by their sensibility, they realize the cultural meaning of the social sciences.Perhaps the most fruitful distinction with which the sociological imagination works is between 'the personal troubles of milieu' and 'the public issues of social structure.' This distinction is an essential tool of the sociological imagination and a feature of all classic work in social science. Troubles occur within the character of the individual and within the range of his or her immediate relations with others; they have to do with one's self and with those limited areas of social life of which one is directly and personally aware. Accordingly, the statement and the resolution of troubles properly lie within the individual as a biographical entity and within the scope of one's immediate milieu - the social setting that is directly open to her personal experience and to some extent her willful activity. A trouble is a private matter: values cherished by an individual are felt by her to be threatened.Issues have to do with matters that transcend these local environments of the individual and the range of her inner life. They have to do with the organization of many such milieu into the institutions of an historical society as a whole, with the ways in which various milieux overlap and interpenetrate to form the larger structure of social and historical life. An issue is a public matter: some value cherished by publics is felt to be threatened. Often there is a debate about what that value really is and about what it is that really threatens it. This debate is often without focus if only because it is the very nature of an issue, unlike even widespread trouble, that it cannot very well be defined in terms of the immediate and everyday environments of ordinary people. An issue, in fact, often involves a crisis in institutional arrangements, and often too it involves what Marxists call 'contradictions' or 'antagonisms.'In these terms, consider unemployment. When, in a city of 100,000, only one is unemployed, that is his personal trouble, and for its relief we properly look to the character of the individual, his skills and his immediate opportunities. But when in a nation of 50 million employees, 15 million people are unemployed, that is an issue, and we may not hope to find its solution within the range of opportunities open to any one individual. The very structure of opportunities has collapsed. Both the correct statement of the problem and the range of possible solutions require us to consider the economic and political institutions of the society, and not merely the personal situation and character of a scatter of individuals.Consider war. The personal problem of war, when it occurs, may be how to survive it or how to die in it with honor; how to make money out of it; how to climb into the higher safety of the military apparatus; or how to contribute to the war's termination. In short, according to one's values, to find a set of milieux and within it to survive the war or make one's death in it meaningful. But the structural issues of war have to do with its causes; with what types of people it throws up into command; with its effects upon economic and political, family and religious institutions, with the unorganized irresponsibility of a world of nation-states.Consider marriage. Inside a marriage a man and a woman may experience personal troubles, but when the divorce rate during the first four years of marriage is 250 out of every 1,000 attempts, this is an indication of a structural issue having to do with the institutions of marriage and the family and other institutions that bear upon them.Or consider the metropolis - the horrible, beautiful, ugly, magnificent sprawl of the great city. For many members of the upperclass the personal solution to 'the problem of the city' is to have an apartment with private garage under it in the heart of the city and forty miles out, a house by Henry Hill, garden by Garrett Eckbo, on a hundred acres of private land. In these two controlled environments - with a small staff at each end and a private helicopter connection - most peoplecould solve many of the problems of personal milieux caused by the facts of the city. But all this, however splendid, does not solve the public issues that the structural fact of the city poses. What should be done with this wonderful monstrosity? Break it all up into scattered units, combining residence and work? Refurbish it as it stands? Or, after evacuation, dynamite it and build new cities according to new plans in new places? What should those plans be? And who is to decide and to accomplish whatever choice is made? These are structural issues; to confront them and to solve them requires us to consider political and economic issues that affect innumerable milieux. In so far as an economy is so arranged that slumps occur, the problem of unemployment becomes incapable of personal solution. In so far as war is inherent in the nation-state system and in the uneven industrialization of the world, the ordinary individual in her restricted milieu will be powerless - with or without psychiatric aid - to solve the troubles this system or lack of system imposes upon him. In so far as the family as an institution turns women into darling little slaves and men into their chief providers and unweaned dependents, the problem of a satisfactory marriage remains incapable of purely private solution. In so far as the overdeveloped megalopolis and the overdeveloped automobile are built-in features of the overdeveloped society, the issues of urban living will not be solved by personal ingenuity and private wealth. What we experience in various and specific milieux, I have noted, is often caused by structural changes. Accordingly, to understand the changes of many personal milieux we are required to look beyond them. And the number and variety of such structural changes increase as the institutions within which we live become more embracing and more intricately connected with one another. To be aware of the idea of social structure and to use it with sensibility is to be capable of tracing such linkages among a great variety of milieux. To be able to do that is to possess the sociological imagination.。

社会学的想象力

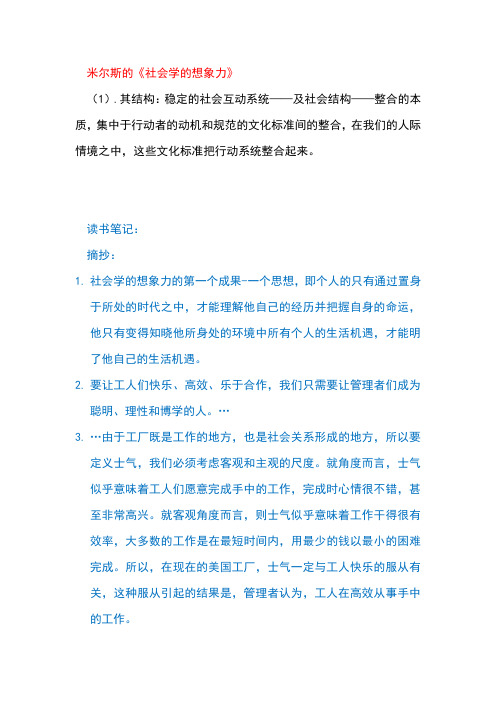

米尔斯的《社会学的想象力》(1).其结构:稳定的社会互动系统——及社会结构——整合的本质,集中于行动者的动机和规范的文化标准间的整合,在我们的人际情境之中,这些文化标准把行动系统整合起来。

读书笔记:摘抄:1.社会学的想象力的第一个成果-一个思想,即个人的只有通过置身于所处的时代之中,才能理解他自己的经历并把握自身的命运,他只有变得知晓他所身处的环境中所有个人的生活机遇,才能明了他自己的生活机遇。

2.要让工人们快乐、高效、乐于合作,我们只需要让管理者们成为聪明、理性和博学的人。

…3.…由于工厂既是工作的地方,也是社会关系形成的地方,所以要定义士气,我们必须考虑客观和主观的尺度。

就角度而言,士气似乎意味着工人们愿意完成手中的工作,完成时心情很不错,甚至非常高兴。

就客观角度而言,则士气似乎意味着工作干得很有效率,大多数的工作是在最短时间内,用最少的钱以最小的困难完成。

所以,在现在的美国工厂,士气一定与工人快乐的服从有关,这种服从引起的结果是,管理者认为,工人在高效从事手中的工作。

4.对我所做的研究进行敏锐的检验。

5.…由于被社会化,他会为他人着想并友善地帮助他们;他不会愁思百结,顾影自怜;相反,他有些外向,踊跃参加社区的日常生活,帮助社区在一个可以调整的有序步伐下“取得进步”。

他加入很多的社区并为之服务。

即便不是十分投入的“参与者”,他当然也会不时的在外面瞅瞅。

他乐于服从传统的道德与动机。

高兴地投身受人尊重的制度的逐渐进步之中。

他的父母可不会离婚,他的家庭也不会无情地破裂。

他可真是“成功”,至少是以谦恭方式取得成功,因为他的进取意识也是很有分寸的;但是,对于过分超越自己能力的事情,他绝不会加以考虑,以免成为一名“脱离实际的思想家”。

作为一名处境尚可的小人物,他不奢求赚到大钱,他的品质太普通,所以我们说不出他们的意义。

…自我理解:进取意识有分寸,但有敢于想象,追求卓越,因为人会在挑战自己的过程中体会到莫大的快乐。

5 科层制的气质《社会学的想象力》 社会学考研必备课件

科层制的危害:

(1)抑制了思想的自由本质,将思想也纳入种种预先设定 好的框架之中,因为如果你的思想成为这个组织的“异 见”,那么你将被驱逐于组织之外,因此拥有科层制气质 的组织也是意识形态的工具。 (2)限制了社科研究的选题,关注实用性,由此容易让主 流的学术研究缺乏对弱势群体和底层社会的应有关怀和重 视; (3)由于这种“形式理性”的存在,导致技术理性的崇拜, 功能合理化以及人文关怀的缺失。 如果社会科学不是独立自主的,它就不可能成为对公众负 责的行业;如果社会科学家的个人研究依赖于科层组织, 他会丧失其个人自主性;如果社会科学包含科层式的研究, 它会丧失其社会和政治自主性。

科层制的气质

近几年所称的“新社会科学”:抽象经验主义和新 的非自由实用性。既针对方法,也针对应用。这造 成科层制社会科学的发展。 抽象经验主义体现科层制的发展:试图把社会调查 的每一步都标准化、合理化;对人的研究通常是集 体性的和系统性的;这一学派的研究小组成员培养 了新的学术上和政治上的心智品质;这种“新的社 会科学”开始投合科层组织的服务对象所持有的目 的;它们有助于提高现代社会中科层制统治手段的 效率、声望和普及程度。 抽象经验主义风格研究费用很高,所以往往由大组 织承担,这使其容易和科层组织结合。

社会研究的科层化是个非常普遍性的趋势,可能它必将在科层组织的规章 已支配一切的社会中实现。自然,随之而生的还有一套非常道貌岸然、不 切实际的理论,它与行政性研究没什么关系。那些专门的研究,一般是统 计式的,并最后应用于行政,不影响我们对观念的详尽阐释;而反过来, 这些详尽阐释也与专门研究的结果无关,而是与政权有其变动不居的特 征——合法化有关。对行政官员来说,世界是一个事实的世界,要根据严 格的规则来处理这些事实。对理论家来说,世界是一个观念的世界,这些 观念可被操纵,但却没有任何明显的操纵规则。理论以各种各样方式成为 权威在意识形态上的证明。通过给有权威的计划者提供有用的信息,为科 层组织目标服务的研究有助于使权威更有力、更有效率。 抽象经验主义已为科层组织所应用,尽管它自然有其明确的意识形态意义, 这些意义有时也被作为意识形态。正如我已阐明的,宏大理论没有直接的 科层制的应用性;它的政治含义是意识形态上的,它的用途也许就到此为 止。如果这两种风格的研究工作——抽象经验主义和宏大理论——共享一 种学术上的“双方垄断”甚或成为支配性的研究风格,它们将对社会科学 的学术前景构成巨大威胁,对理性在人类事务中扮演角色的政治前景构成 巨大的威胁——而西方社会的文明从古典时代以来就一直在孕育这个角色。

社会学的想象力PPT课件

前景之四:论政治

• 独立公共知识分子的政治责任:社会科学家作为文 科教育者,他的政治职责就是不断地将个人困扰 转换为公共议题,并将公共议题转换为它们对各 种类型个体的人文上的意义。通过这样的方式, 公共知识分子充分利用自身的博学素养以及资源 掌控力,帮助公众提升自我修养,鼓励公众形成 自身理性和个体性,使理性以民主方式与公共利 益相关,从而实现民主社会的主流价值。

• 它最明显的特征,涉及它已开始采用的行政机构 以及它吸收和训练的学者类型——学术行政管和 研究技术专家,这种研究风定的那种科学哲 学信奉为惟一的科学方法,这种科学方法严格限 定了人们所选择研究的问题和表述问题的方式, 它所提的科学方法主要是从自然科学哲学借鉴而 来的。

14

批判之二:抽象经验主义

• 死抓住研究程序中的一个接合点,是方法论的抑 制。它的结果通常是以统计判断的形式表示:在 最简单的层次上,这些结果只是一些比例结论, 但在较复杂的层面上,根据不同的问题,解答经 常被组合进繁复的交互分类之中……人们可以通过 某些复杂方法处理这样的数据,但它不管怎么复 杂,仍只是对已知数据的分类而已。

现象在更大的历史的坐标系中所处的位置 是什么?

25

前景之三:理性和自由

• 社会科学的道德与政治承诺是:自由与理 性仍将是人们珍视的价值。

• 当代任何对自由主义者和社会主义者的政 治目标的重新表达都必须以下述社会作为 中心思想。在此社会中,所有人都成为具 有实质理性的人,他们独立的理性将对他 们置身 的社会、对历史和他们自身的命运 产生结构性影响力。

12

二、批判之一:宏大理论

• 皇帝的新衣 • 帕森斯是宏大理论的最突出代表 • 繁文冗词、迷恋句法、概念游戏 • AGIL模型

13

社会学的想象力

目录分析

献辞 第一章承诺

第二章宏大理论 第三章抽象经验主义

他们的私人困扰并不只是个人命运的问题,而是和全社会的结构性问题密不可分;社会结构若不发生根本性 转变,他们的私人境遇就不可能真正得到改善。

正相反,现如今,“人的主要危险”乃在于当代社会本身桀骜难驯的力量,以及其令人异化的生产方式、严 丝合缝的政治支配技术、国际范围内的无政府状态,简言之,即当代社会对人的所谓“本性”、对人的生活的境 况与目标所进行的普遍渗透的改造。

读书笔记

读书笔记

翻译极佳。 这本书值得每一个人读。读的时候总感觉被作者骂了(x读到脸红。 所谓价值,就是共享符号系统的一个要素,充当着某种判据或标准,以便从某个情境中固有的开放可用的多 个取向替换方案中做出选择。 学术研究和思维方法启蒙读物,真知灼见的作者米尔斯是一个特立独行的人。 看完更悲观了,全面政治化的社会很难产生真正的社会学家,大量的公共议题得不到梳理,民众焦虑不安的 情绪得不到抒发,看似平静的湖面却是暗流涌动。 本以为本书是一本社会学入门书籍,实际上本书相当深刻的揭露了这门学科的各种弊病,并提出了解决方式 和方法。 “他是激进传统的激进纠偏者,是对社会学课程满腹牢骚的社会学家,是屡屡质疑知识分子的知识分子…” 说的是作者米尔斯。 个人困扰很多,有的早已转变成公共议题,有的也许是在成为个人困扰时已经是毋庸置疑的公共议题了。

社会学的想象力

读书笔记模板

01 思维导图

03 读书笔记 05 目录分析

社会学的想象力

社会学的想象力之宏大理论所有这些都触及一个痛处,即可理解性。

宏大理论家们如此深入地卷入该问题,以致我们恐怕真的要问:宏大理论不过是混乱不堪的繁文冗词还是其中终究还有一些东西?我认为,答案是:是有些东西,当然隐埋得很深,不过总是说了点东西。

因而问题变成:当从宏大理论中排除掉所有妨碍理解其意义的东西,能够看到可以理解的内容之后,那么,它说了些什么呢?。

我估计,用类似方式,你可以把555页的《社会系统》转述为150页左右的简明英语。

这个转述本不会给人很深刻的印象。

但是,在这个转述中,原书中的关键问题以及原书所提出的对问题的解答得到了非常清晰的陈述。

任何思想,任何书当然都是既可以用一句话,也可以用20卷书表达出来。

这是一个说明某个东西需要用多么全面的陈述,以及这个东西显得有多么重要的问题:它能让我们理解多少经历,它能让我们解决,或至少是陈述的问题范围有多大。

宏大理论的基本起因是开始思考的层次太一般化,以致它的实践者们无法合乎逻辑的或落到观察上来。

作为宏大理论家,他们从来没有从更高的一般性回落到在他们所处的历史的、结构性的情境中存在的问题。

由于对真正的问题缺乏踏实感受,他们的文章的不现实性非常显著。

这样所产生的一个特征是:在我们看来,对细节进行随意的、无休止的修饰,它既不能增进我们的理解,也不能使我们的体验更易于感受。

从而,这种情况暴露为他们在描述和解释人类行为和社会时,有时故意规避明白晓畅的行文。

当我们考虑一个词语代表什么时,我们涉及的是它的语义学的一面;当我们在它与其他词的关系中考虑它时,我们涉及的是它的句法学的一面。

宏大理论在句法学上浑浑噩噩,对语义学也茫然无知。

它的实践者们并不真正理解:当我们定义一个词语时,我们只是欢迎其他人以我们所喜欢的它被运用的方式来运用它;定义的目的是让争论能集中于事实上,好的定义的应有结果是把对术语的争论转变为对事实的不同看法,从而掀起进一步研究所需的争论。

社会学的想象力之抽象经验主义。

社会学的想象力

科层制的气质

实地调查研究的风格问题也很重要。费用不菲的 实地研究,就要涉及经费的取得来自于商业科层 制的公司,在这个问题上,研究的本身属性也会 被商业科层制公司的局限性眼光所左右。 在学术传统中也具有科层制的弊端,到底是科层 在学术传统中也具有科层制的弊端,到底是科层 制中的地位决定了学术还是学术为人们赢得了地 位呢?科层制这一社会学家们推崇备至的理想模 位呢?科层制这一社会学家们推崇备至的理想模 型却在学术体之外对社会学研究产生了束缚。

二、在人类的历史长河中,该社会变化的动力是什么?对 于人性的整体进步,他出于什么地位,具有什么意义?

三、在这一社会这一时期,占主流的是什么类型的人?什 么类型的人又将逐渐占主流?社会各方面对“人性”有何 意义?

形形色色的实用性

自由主义实用性 --------服务于意识形态 --------服务于意识形态 保守主义实用性 --------服务于科层组织 --------服务于科层组织

作 者 简 介

C·赖特·米尔斯,美国著名的批判社会学家。 C·赖特·米尔斯,美国著名的批判社会学家。 赖特 他早年求学于威斯康星大学, 他早年求学于威斯康星大学,广涉社会与政 治理论,兼修史学和人类学,25岁获博士学 治理论,兼修史学和人类学,25岁获博士学 50年代初以 白领:美国的中产阶级》 年代初以《 位。50年代初以《白领:美国的中产阶级》 一举成名,并任教于哥伦比亚大学社会学系。 一举成名,并任教于哥伦比亚大学社会学系。 他在知识社会学和美国社会阶层研究这二个 方面都有杰出的成绩, 方面都有杰出的成绩,则被视为其主要代表 他与人合作编译的《韦伯社会学文选》 作,他与人合作编译的《韦伯社会学文选》 亦被认为是权威译本。米尔斯1962 1962年病逝于 亦被认为是权威译本。米尔斯1962年病逝于 纽约,年仅46 46岁 死后被誉为“ 纽约,年仅46岁,死后被誉为“当代美国文 明最重要的批评家之一”。 明最重要的批评家之一”

2-宏大理论《社会学的想象力》-社会学考研必备课件

从宏大理论家研究中出现的系统性缺失之中,我们能 学到的一个深刻教训是每一个自觉的思想家都必须始 终了解,从而能够控制他所研究东西的抽象层次。轻 松而有条不紊地在不同抽象层次间穿梭的能力,是一 位富有想像力和系统性的思想家的显著标志。

“共同价值”。只有极端而“纯粹”类型的社会 结构,才显露出这些普遍的、核心的符号。

理想的关系

建立科学理论的潜力

思辨理论

自然主义分析框架

富有趣味的哲学

敏感化分析框架

在可能时是公理命题

形式命题 分析模型

最可能产生可检验理论

中层命题 因果模型 经验概括

假如研究者愿意提高抽象性, 就有可能产生理论

理论解释所需要的资料

宏大理论家们如此迷恋句法意义,对语义的关联性是 如此缺乏想像力,他们又是如此呆板地局限于这么高 层次的抽象,以至他们所构造出的“分类体系”,以 及他们构造这些分类体系的工作,往往更像是枯燥乏 味的概念游戏,而不是努力系统性地定义手中的问题, 并指引我们解决这些问题。

我们不能假设统治必须最终出于人们的同意。现在,广为 盛行的权力手段是管理与操纵人们的同意的权力。当前有 许多权力,未经过理性或服从者的良知就被成功地行使。

今天有许多人丧失了对主流价值的忠诚,又没有获得新的 价值,于是对任何种类的政治关注都不热心。他们既不激 进,也不反动。

1 前景 《社会学的想象力》 社会学考研必备课件

夫妻责任分担——夫将负担转给妻——夫更大的个人发展与 妻个人发展的相对停滞——夫“甩掉”妻的潜在可能——夫 否认这种可能。

这种想像力的第一个成果:个人只有通过置身于 所处的时代之中,才能理解他自己的经历并把握 自身的命运,他只有变得知晓他所身处的环境中 所有个人的生活机遇,才能明了他自己的生活机 遇。社会学的想像力可以让我们理解历史与个人 的生活历程以及在社会中二者间的联系。

19世纪得到认同的社会科学的学科:历史学、经济 学、社会学、政治学和人类学。此外,还有东方学。

对现代/文明世界的研究(历史学再加上三门以探寻 普遍规律为宗旨的社会科学)与对非现代世界的研 究(人类学加上东方学)之间存在着一条分界线; 对现代世界的研究,过去(历史学)与现在(注重 研究普遍规律的社会科学)之间存在着一条分界线; 在以探寻普遍规律为宗旨的社会科学内部,对市场 的研究(经济学)、对国家的研究(政治学)与对 市民社会的研究(社会学)之间也存在着鲜明的分 界线。

有社会想象力的社会分析家总是不断地问三种类型的问 题: (1) 一定的社会作为整体,其结构是什么?它的基本组成 成分是什么,这些成分又是如何相互联系的?这一结构 与其他种种社会秩序有什么不同?在此结构中,使其维 持和变化的方面有何特定涵义? (2) 在人类历史长河中,该社会处于什么位置?它发生变 化的动力是什么?对于人性整体的进步,它处于什么地 位,具有什么意义?我们所考察的特定部分与它将会进 入的历史时期之间,是如何相互影响的?那一时期的基 本特征是什么?与其他时代有什么不同?它用什么独特 方式来构建历史? (3) 在这一社会这一时期,占主流的是什么类型的人? 什么类型的人又将逐渐占主流?通过什么途径,这些类 型的人被选择,被塑造,被解放,被压制,从而变得敏 感和迟钝?我们在这一定时期一定社会中所观察到的行 为与性格揭示了何种类型的“人性”?我们所考察的社 会各个方面对“人性”有何意义?

1 前景 《社会学的想象力》 社会学考研必备课件解析

社会学家究竟是做什么的?社会学家能够为 自己社会行为的性质与缘起提供哪些启发?

首先从学科的历史发展看:

在整个19世纪,各门学科呈扇形扩散开来, 一端首先是数学,其次是以实验为基础的自 然科学;另一端则是人文科学(或文学艺 术),然后是对于形式艺术实践(包括文学、 绘画和雕塑、音乐学)的研究。介乎人文科 学和自然科学之间的是对于社会现实的研 究——社会科学。

米 尔 斯

写作背景

人们越来越关注“完全私人性的领域”,对“社会结构中的公众论题” 表现得甚是漠然。而社会科学领域内的公共知识分子也越来越丧失了 作为一名社会科学家的“政治职责”。他们要么从纯粹地高度抽象地 概念出发,通过一系列混乱的逻辑推演建构起一种虚妄而不真实的, 缺乏对社会有真正解释力的“宏大理论”;要么从所谓的方法论出发, 按照他们自认为科学的抽样调查、数学统计的归纳来理解社会,结果 自己却成了“国王的幕僚”。 “后现代” ——散众社会。在“后现代情境”中,工作中的人是各种 管理术的操纵对象,工作外的人自囿于各自的生活小圈圈,无法理解, 遑论掌握那些形成当代社会的结构性力量。由无数个无力参与到社会 发展方向决定过程的旁观者所构成的社会,也就是“散众社会” 。这 个情境中的“主体”就是“快乐机器人”。大众消费社会来临、权力 集中于科层制顶峰、知识分子与工人领袖被收编,以及普通人的弱智 化。 我们应当在社会生活中运用理性,改变我们的生存处境,扩大我们的 内在与外在自由。

在以探寻普遍规律为宗旨的社会科学内部,对市场

的研究(经济学)、对国家的研究(政治学)与对

市民社会的研究(社会学)之间也存在着鲜明的分

界线。

社会学还是一直保持着对普通人以会学与社

《社会学的想象力》

《社会学的想象力》一、作者简介C·赖特·米尔斯(1916~1962),美国社会学家,文化批判主义的主要代表人物之一,生前任教于哥伦比亚大学社会学系。

米尔斯在知识社会学和美国社会阶层研究这两个方面都有杰出的成绩,代表作有《白领:美国中产阶级》(1951)、《权力精英》(1956)和《社会学的想像力》(1959)等。

50年代初他以《白领:美国的中产阶级》一举成名,而《社会学的想象力》是他生前的最后一部作品,也是他最重要的代表作。

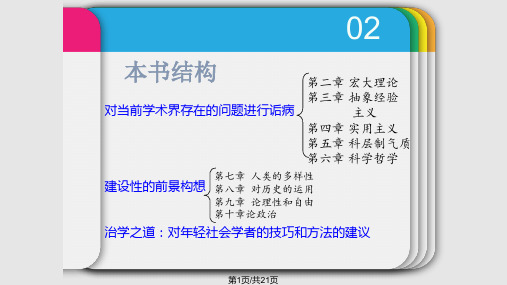

二、全书概述《社会学的想象力》全书共分为十章,在第一章米尔斯简述了本书的核心观点:什么是社会学的想象力,以及社会学家应该如何想象。

在第二到六章,米尔斯考察了社会科学久而成习的一些偏向,展开了对社会科学研究的批判,主要涉及宏大理论、抽象经验主义与科层制。

在评述了社会科学发展的趋势后,在第七到十章,米尔斯提出了自己对未来社会学发展的展望,认为社会科学研究应该注重人的多样性、对历史的运用、理性与自由,以及应该保持独立自主的政治角色。

这本书的写作背景是两次世界大战之后,社会学的中心从欧洲移向了美国,芝加哥学派在美国独树一帜。

在米尔斯所处的时代,美国经济快速发展,美国社会科学得到了极大繁荣,同时许多社会学家跻身政府名门。

米尔斯表示,写作此书的目的是“要界定社会科学对于我们这个时代的文化使命所具有的意义。

具体确定有哪些努力在背后推动着社会学的想象力的发展,点明这种想象力对于文化生活以及政治生活的连带意涵,或许还要就社会学的想象力的必备条件给出一些建议。

通过这些方面来揭示今日社会科学的性质与用途,并点到即止地谈谈它们在美国当前的境况。

”总的来说,米尔斯认为,任何社会研究都应该探讨人生、历史以及两者在社会中的相互关联,他反对将社会科学当作一套科层技术,靠方法论上的矫揉造作来禁止社会探究,以晦涩玄虚的概念来充塞这类研究,或者只操心脱离具有公共相关性的议题的枝节问题,把研究搞得琐碎不堪。

社会学的想象力米尔斯PPT课件

务于主题,不应该成为研究目的。 每个人都必须是自己的方法论家和理论家!

没有一种方法是解决所有问题的“万金油”。我们应该从各种

尝试中形成自己的方法,不能勉强用方法中的“应急方案”。

从来因没此有,应哪以一问学题科为导是向被,当促进做专完业整之计间的划融的合一与部交流分,发展而 来许多社会科学家都认识到更为明确地确认社会科学为

共同导向的任务,将使他们更好地实现他们自己的学 科目标。

第11页/共21页

提倡:对历史的运用 4.2

为什么社会家需要具备历史视野,充分利用历史资料?

1、当代社会的某些特性只有通过与过去的比较才能体现出来。

20年代 广告商与营销商 30年代 民意调查机构 40年代 学院及办事处 二战后 联邦政府部门

·对赞助方负责,提供他们 感兴趣的信息 ·关注点集中于细节上,不 设定自己的根本问题 ·不为公众发言 ·有损超然客观性,不依托 个人兴趣

重点介绍两种人:学术行政官和学术新手

派系(学派):作为升迁机制的派系成为 学术行政官玩弄权术博得声誉的工具

米尔斯的转述: 当人们享有相同的价值时,他 们趋向于依照其他人行动的方 式来行动。而且他们往往将这 种服从看做好事——甚至在它 似乎违背了他们的切近利益之

时。“我估计,用类似的方式,你 可以把555页的《社会系统》 转述为150页的简明英语”

任何思想当然都是既可以用一句 话,也可以用20卷书来表达出来, 关键是你的陈述能让我们理解多 少经历,解决问题的范围有多大。

“解释类型”

“解释变量”

“理论”

“有用的变量集合”

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

我们也许可以很完整地想像出一个“纯粹类型”的社会, 它具有非常有纪律的社会结构,在其中被支配的人们出于 各种各样原因,不能放弃他们被规定了的角色,但是却一 点也不共享支配者的价值,于是他们根本不信任秩序的合 法性。

行动系统

价值内化 人格系统

文化系统

社会化 社会控制

制度化 社会系统

环境

环境

存在“社会系统”,人们在其中彼此参照,进行行动。这些 行动往往是非常有序的,因为个人在系统中共享价值标准和 行为标准。这些标准有的可称之为规范,那些依照规范行为 的人在相似情况下趋于作出相似的行动。——“社会规律性”, “结构性的”。

宏大理论

可以把555页的《社会系统》转述为150页左右。原书中的关 键问题以及原书所提出的对问题的解答得到了非常清晰的陈述。 任何思想,任何书当然都是既可以用一句话,也可以用20卷书 表达出来。这是一个说明某个东西需要用多么全面的陈述,以及 这个东西显得有多么重要的问题:它能让我们理解多少经历,它 能让我们解决,或至少是陈述的问题范围有多大。

主要有两个方式来维持社会均衡。第一个方式是“社会化”, 指的是把一个新出生的个体培养为社会人的所有方式。社会 对人的这种培养部分地在于让他们习得采取社会行动的动机, 而这些社会行动是为他人所要求或期望的。另一个方式是 “社会控制”,我指的是让人们循规蹈矩以及他们让自己循 规蹈矩的所有方式。当然,对于“规矩”,我指的是在社会 系统中一般被期望或约束的任何什么行动。

我们不能假设统治必须最终出于人们的同意。现在,广为 盛行的权力手段是管理与操纵人们的同意的权力。当前有 许多权力,未经过理性或服从者的良知就被成功地行使。

今天有许多人丧失了对主流价值的忠诚,又没有获得新的 价值,于是对任何种类的政治关注都不热心。他们既不激 进,也不反动。

宏大理论无法有效地表述关于冲突的思想。结构性的对抗, 大规模叛乱,革命,它们是无法想像的。事实上,该理论 有以下假设:“系统”一旦被建立,就不但很稳定,而且 是内在和谐的;而用帕森斯的语言,失调必须“被引入到 系统之中。”他所提出的规范性秩序的思想导致我们把利 益和谐假设为任何社会的特征。

理想的关系

建立科学理论的潜力

思辨理论

自然主义分析框架

富有趣味的哲学

敏感化分析框架在可Βιβλιοθήκη 时是公理命题形式命题 分析模型

最可能产生可检验理论

中层命题 因果模型 经验概括

假如研究者愿意提高抽象性, 就有可能产生理论

理论解释所需要的资料

宏大理论家们如此迷恋句法意义,对语义的关联性是 如此缺乏想像力,他们又是如此呆板地局限于这么高 层次的抽象,以至他们所构造出的“分类体系”,以 及他们构造这些分类体系的工作,往往更像是枯燥乏 味的概念游戏,而不是努力系统性地定义手中的问题, 并指引我们解决这些问题。

秩序问题——是帕森斯著作中的主要问题。社会整合的问 题。

首先,是什么东西把社会结构联系在一起?答案不止一个, 因为各种社会结构的统一性程度和类型有深刻的差异。实 际上,我们可以根据不同整合方式构想出不同类型的社会 结构。——人类的多样性。

不存在什么能让我们理解社会结构的统一性的“宏大理论” 和普遍性的体系,对于古老的颇为恼人的社会秩序问题, 其答案也并非一个。对这些问题的有用研究,主要是根据 我在此概括的这些研究模型,而运用这些模型,要与特定 范畴的历史上的及当代的社会结构保持经验上的密切联系。

不同国家的整合模式不同,同一国家不同时期整合模式不 同。

每一个制度性秩序是如何变迁的?它与其他各个秩序的关 系又是怎样变化的?这些结构性变化发生的进度和不同速 率如何?并且,在每种情况下,引起这些变化的必要的和 充分的原因是什么?需要以比较和历史的方式进行研究。

选择=结果

汇报结束 谢谢观看! 欢迎提出您的宝贵意见!

从宏大理论家研究中出现的系统性缺失之中,我们能 学到的一个深刻教训是每一个自觉的思想家都必须始 终了解,从而能够控制他所研究东西的抽象层次。轻 松而有条不紊地在不同抽象层次间穿梭的能力,是一 位富有想像力和系统性的思想家的显著标志。

“共同价值”。只有极端而“纯粹”类型的社会 结构,才显露出这些普遍的、核心的符号。

问题是:当社会均衡存在,以及与之匹配的社会化和控制手 段都齐全时,怎么还有人不守规矩?

如何解释社会变迁,也就是说,历史呢?

宏大理论的基本起因是开始思考的层次太一 般化,以至它的实践者们无法合乎逻辑地回 落到观察上来。作为宏大理论家,他们从来 没有从更高的一般性回落到在他们所处的历 史的、结构性的情境中存在的问题。

《社会系统》:“我们被问及:社会秩序怎样成为可能?我们所 给的答案似乎是:被共同接受的价值。”

《权力精英》:“‘究竟是谁在操纵美国?’没有人完全操纵它, 但如果说有哪个群体这么做了,它是权力精英。”

《社会学的想像力》:社会科学研究什么?它们应该是研究人和 社会。它们是帮助我们理解个人生活历程与历史,以及二者在不 同社会结构中的结合的各种努力。