李嘉图模型中的4个数字

国际经济学第八版第3章

(二)比较优势理论分析—— 单一要素的经济 单一要素的经济(局部均衡)

Байду номын сангаас

国内经济的技术可以用每个产业的劳动生产率来概括, 以单位劳动力需求量来表达: 每单位劳动力需求是指生产一单位产出所需要的劳动 力数量. 每单位葡萄酒对劳动力需求用aLW表示 (例如如果 aLW = 2, 那么一加仑的葡萄酒就需要两个小时劳动). 每单位奶酪对劳动力需求用 aLC表示 ((例如如果 aLW = 1, 那么一磅的奶酪就需要一个小时劳动). 经济的全部资源定义为 L, 全部劳动力供应 (例如如果 L = 120, 那么这个经济拥有120小时劳动,或者120个工 人).

19

(四)单一要素世界的贸易1

图 2-2: 外国的生产可能性边界

外国葡萄 酒产量, Q*W(加仑)

L*/a*LW

F*

+1

P* L*/a*LC 外国奶酪产量, Q*C (磅)

20

(四)单一要素世界的贸易—

一般均衡2

贸易后确定相对价格——两个国家两种产品的交换比率 贸易后什么确定相对价格 (例如 PC / PW)? 为了解答这个问题,我们需要把世界作为一个整体 确定奶酪的相对供给和相对需求. 奶酪的相对供给等于在给定的相对价格下,两国奶 酪的总供应量除以葡萄酒的总供应量, (QC + Q*C )/(QW + Q*W). 世界的奶酪相对需求也是一个类似的概念.

17

(四)单一要素世界的贸易1

绝对优势 如果一个国家在某种商品上生产较外国需要更少的 单位劳动力,那么这个国家就在这种商品的生产上 具有绝对的比较优势. 假定 aLC < a*LC 和 aLW < a*LW 这种假定暗含国内在两种产品的生产商都具有绝 对优势 。换个角度看就是国内比国外具有更高 的生产效率. 即使国内在两种商品上拥有 绝对优势,可获利 的贸易也是可能发生的.如自然资源不同 贸易结构将会被比较优势所决定.

(8)李嘉图模型的新兴古典解释

a ∂u1x > 0, iff p > 1 y , l1x = 1 ∂l1x ka1x

a1 y ∂u1x < 0, iff p < , l1x = 0 ∂l1x ka1x

step 4:所以只有在p=a1y/ka1x时,国家1的个人生产两 种商品。 step 5:p代入解,得:

x1 = β a1x ⎧ ⎪ s x 1 = a1 x (l1 x − β ) ⎪ ⎪ y1 = a1 y (1 − l1x ) ⎪ ⎨ a1 y (l1x − β ) d ⎪ y1 = ⎪ k ⎪ * β 1− β β 1− β u | = β (1 − β ) a1x a1 y ⎪ ⎩ 1 S2

S3下国家1个人决策问题: 国家1中个人选择模式(x|y):

{ x1 , x1 , y1 }

Max s d

u1 = x1b ( ky1d )1-b

s.t. x1p = x1 + x1s = a1xl1x l1 x = 1

px1s = y1d

x1 , x1s , y1d > 0

S3下国家2个人决策问题: 国家2中个人选择模式(xy|x):

新制度经济学

(八)李嘉图模型的新兴古典解释

� 一:李嘉图的外生比较优势模型 � 二:新兴古典超边际分析方法的应用 � 三:一般均衡与超边际比较静态分析

一:李嘉图的外生比较优势模型

� 假设一简单交换经济的世界体系中存有两个 国家,国家i(i = 1, 2)投入生产的总劳动时 间为Mi,生产单位产品j(j = x, y)的劳动时 间为tij(劳动生产力:aij=1/tij),则国家i的 PPF:tixx+tiyy=Mi � 令t1y /t1x > t2y /t2x,根据李嘉图的比较优势原理知: 两国专业化分工时,即国家1生产x,国家2生 产y,此时对全世界来讲具有最大的“好处”: x=M1/t1x=a1xM1 y=M2/t2y=a2yM2

国贸总复习思考题答案_经济学_高等教育_教育专区

(2) 该国是否可用本国拥有的资源来生产90单位酒和50单位奶酪 为什么 答:Qw×Lw + Qc×Lc =90×10+50×4=1100>400; Qw×Tw+Qc×Tc =90×5+50×8=850>600 所以不可能用这些资源生产出这些产品。

三、当代贸易理论

5题.分析下列四题, 解释每题中是外部规模经济情形还是内部规模经济情形。 (1) 美国印第安纳州艾克哈特的十几家工厂生产了美国大多数的管乐器。 (2) 在美国销售的所有本田车要么是从日本进口的, 要么是在俄亥俄州的玛丽斯维尔生产的。 (3) 欧洲惟一的大型客机生产商—空中客车公司的所有飞机都在法国土鲁斯组装。 (4) 康涅狄克州的哈特福特成为美国东北部的保险业中心。

(1)为什么出口补贴没有完全反映在国内市场的新价格上 (2) 出口补贴对该国的生产和出口有什么影响 (3) 出口补贴对消费者剩余、生产者剩余和政府收入有什么影响 (4) 在上图中,消费者剩余、生产者剩余和政府收入分别由哪些区域表示 (5) 出口补贴对该国贸易条件有什么样的影响

(1) 当出口国(本国)的价格从 6000 美元上升为 6450 美元、进口国的价格从 6000 美元下降为 5550 美元时, 本国价格的上升幅度小于补贴。 (2) 价格上升后,本国拖拉机的产量由70台增加为80台, 出口增加 20台,由50台变为76台。 (3) 本国的拖拉机消费者因为价格的上涨而受损。政府因补贴而受损。 (4) 在图上,消费者损失等于区域α+b,生产者得益等于区域 a +b十 C ,政府损失等于b +C +d +e +f +g +h+i 。 (5) 出口补贴降低了外国市场上的出口价格,贸易条件恶化。这与关税对贸易条件的影响正好相反。

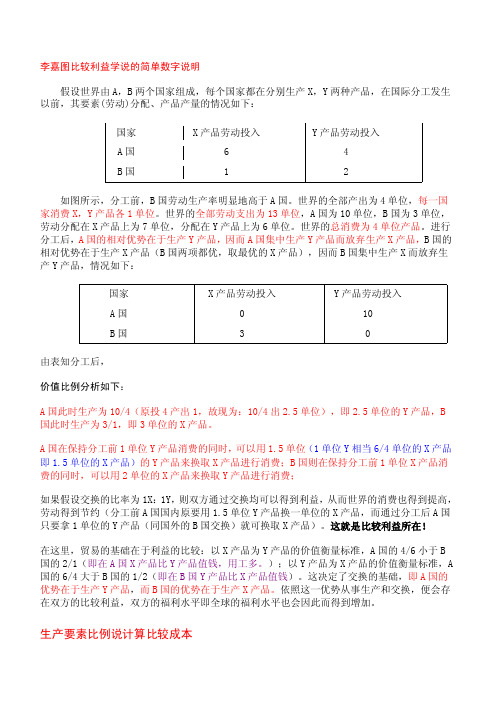

李嘉图比较利益学说的简单数字说明

李嘉图比较利益学说的简单数字说明假设世界由A,B两个国家组成,每个国家都在分别生产X,Y两种产品,在国际分工发生以前,其要素(劳动)分配、产品产量的情况如下:国家X产品劳动投入Y产品劳动投入A国 6 4B国 1 2如图所示,分工前,B国劳动生产率明显地高于A国。

世界的全部产出为4单位,每一国家消费X,Y产品各1单位。

世界的全部劳动支出为13单位,A国为10单位,B国为3单位,劳动分配在X产品上为7单位,分配在Y产品上为6单位。

世界的总消费为4单位产品。

进行分工后,A国的相对优势在于生产Y产品,因而A国集中生产Y产品而放弃生产X产品,B国的相对优势在于生产X产品(B国两项都优,取最优的X产品),因而B国集中生产X而放弃生产Y产品,情况如下:国家X产品劳动投入Y产品劳动投入A国0 10B国 3 0由表知分工后,价值比例分析如下:A国此时生产为10/4(原投4产出1,故现为:10/4出2.5单位),即2.5单位的Y产品,B国此时生产为3/1,即3单位的X产品。

A国在保持分工前1单位Y产品消费的同时,可以用1.5单位(1单位Y相当6/4单位的X产品即1.5单位的X产品)的Y产品来换取X产品进行消费;B国则在保持分工前1单位X产品消费的同时,可以用2单位的X产品来换取Y产品进行消费;如果假设交换的比率为1X:1Y,则双方通过交换均可以得到利益,从而世界的消费也得到提高,劳动得到节约(分工前A国国内原要用1.5单位Y产品换一单位的X产品,而通过分工后A国只要拿1单位的Y产品(同国外的B国交换)就可换取X产品)。

这就是比较利益所在!在这里,贸易的基础在于利益的比较:以X产品为Y产品的价值衡量标准,A国的4/6小于B国的2/1(即在A国X产品比Y产品值钱,用工多。

);以Y产品为X产品的价值衡量标准,A 国的6/4大于B国的1/2(即在B国Y产品比X产品值钱)。

这决定了交换的基础,即A国的优势在于生产Y产品,而B国的优势在于生产X产品。

国际贸易学 第三章 劳动生产率与比较优势:李嘉图模型 PPT教学课件

1

Chapter 2 劳动生产率与比较优势:李嘉图模型

§1 基本的理论假设与主要概念

1.1 理论的奠基人:斯密与李嘉图

6

Chapter 2 劳动生产率与比较优势:李嘉图模型

§2 理论分析:从绝对优势到比较优势

2.2 比较优势理论

1.理论背景: 1815年,英国颁布了《谷物法》——这有利于地 主贵族,导致了谷物价格飞涨,而损害了资产阶级 的利益。资产阶级需要更为彻底的自由贸易理论。 2.比较优势理论分析 (分析过程见插图)

亚当·斯密(Adam Smith,1723~1790),第一

位学院派经济学家。1776年发表《国富论》,批判

重商主义,提出绝对优势原理并论证了自由贸易的 合理性和可行性,且在书中提出了“经济人”和 “看不见的手”等两个现代经济学的核心命题。

大卫·李嘉图(David Ricardo,1772~1823), 资产阶级古典政治经济学的完成者。1817年出版

3

Chapter 2 劳动生产率与比较优势:李嘉图模型

1.3 主要概念和实证分析工具

1.3.1 优势的数理描述工具

1.劳动生产率 2.生产成本 3.机会成本

一种物品的机会成本可用两种方法表示; 其一是产出表示法,即边际技术替代率;其 二是比较优势:李嘉图模型

显然,这个具体交换比例愈是接近本国国内的交 换比例,对本国越不利,愈是接近对方国的比例, 则对本国越有利。

9

Chapter 2 劳动生产率与比较优势:李嘉图模型

国贸案例分析

★2、某国内权威研究机构在分析中国加入 WTO的影响时指出,加入 WTO 将导致中国的工资水平上升而资本的收益率下降,请用斯托尔珀——萨缪尔森定理来分析这一观点。

答:按照斯托尔珀——萨缪尔森定理,只要要素可以在部门间自由流动,那么随着国际贸易的发生,进口竞争部门所密集使用的要素收入减少,而出口部门所密集使用的要素收入增加。

也就是说,贸易有利于本国供给丰富的生产要素的所有者,不利于本国供给短缺的生产要素的所有者。

由于中国是劳动力非常丰富而资本相对短缺的发展中国家,因此,开展对外贸易将导致中国的工资水平上升,而资本的收益率下降。

·19 .下面哪一个贸易前的成本比率对于进行有利可图的贸易是至关重要的:1美国小麦投入(如劳动)成本与外国小麦投入成本的比率;2美国小麦与美国布的投入成本比率;3美国用布的码数表示的小麦成本与其他国家用布的码数表示的小麦成本比率?·20. 在 H— O 贸易模型中,假设在没有贸易的情况下,中国大米的国内市场价格是每吨100 美元,而国际市场上的大米价格是每吨120美元。

在允许自由出口的情况下,中国的大米价格会出现什么趋势?如果中国以国际市场价格出口1000吨大米的话,中国的纯收益(或纯损失)是多少(用图形和数字说明)·21. 在古典贸易模型中,假设 A 国有 120名劳动力, B 国有 50 名劳动力,如果所有的劳动力都用来生产棉花的话, A 国的产量是 240吨,B 国是 100吨;要是两国都生产大米的话, A 国能生产 1200吨, B 国则能生产 800 吨。

画出两国的生产可能性曲线并分析两国中哪一国拥有生产大米的绝对优势?哪一国拥有生产大米的比较优势?·22. 设中国与美国生产每单位产品所需的劳动时间如下表所示的四种情况:单位成本假设一假设二假设三假设四中国美国中国美国中国美国中国美国小麦(小时 /公斤)82418242布(小时 /米)24324421美国与中国在哪些产品的生产上具有绝对利益?美国与中国在哪些产品的生产上具有比较利益?美国与中国将会如何分工? 分工后两种产品在国际贸易中的交换比率一定在什么范围?·23. 假设美国有 20 个劳动力,中国有100个劳动力,日本有 10 个劳动力。

第二章李嘉图模型

• 事实上,这些指责将生产率的增长率和水平两个概念做了 混淆,从而错误地使用了比较优势的理论。

26

工资与价格的决定

• 世界相对价格的决定:

• 自由贸易的基础是比较优势,而不是绝对优势。 • 比较优势强调一个国家应该专业化生产其相对最有效率的

产品。 • 由于专业化生产提高了资源的使用效率,任何国家,即使

不发达国家也能从贸易中获利。

37

对贸易的误解

误解二:高工资国家的利益会在和低工资国家贸 易时受到损害

• 回应:

• 贸易可能会降低高工资国家部分人的收入,从而影响一 国的收入分配。

15

贸易模式与贸易所得

• 现在我们讨论开放经济下的情况: • 假设同时存在“本国”与“外国”,两个国家之间可以

进行产品交换,且不存在交易成本和运输费用。 • 类似地,我们用 p*,w*,a*来表示外国相应的价格、工资

和生产率。

16

贸易模式与贸易所得

• 李嘉图认为,国际间相对劳动力的差异是国际贸易的决定 因素。即,当alp/alc>alp*/alc*或alp/alc<alp*/alc*时,就会有贸 易发生。

6

无差异曲线

• 无差异曲线可以有多种形状。

7

生产可能性边界

• 生产可能性曲线(PPF)能够表示出在恒定的生产率和 有限的资源下最大限度的生产一系列产品的组合。

• 李嘉图模型中所讨论的生产可能性边界只包括两种类型 的产品,而且这两种产品的生产率是恒定的。

8

生产可能性边界

第二节李嘉图模型

第二节李嘉图模型斯密绝对优势说不能回答这样的问题:如果一国在所有产品生产上都不存在着绝对有利的生产条件,那么这个国家还要不要参加国际贸易,或者说还能不能从国际贸易中获得利益呢?而当时许多殖民地便处于这种状况,它们又与宗主国之间发生了大量的双向贸易。

李嘉图(D. Ricardo)提出的比较优势理论(亦称比较成本说)解释了这一问题,李嘉图认为,即使一国在所有产品的生产成本上与别国相比都处于劣势,仍然会进行国际贸易,仍然可以获得贸易利益。

李嘉图在其1817年出版的《政治经济学及赋税原理》一书的第7章“论对外贸易”中,运用两国两产品模型,论证了国际贸易的基础是比较优势而非绝对优势。

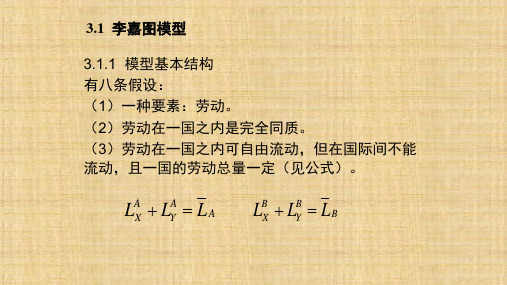

一、李嘉图模型的假设进行经济分析常常需要通过一些假设条件使问题简化,李嘉图及其追随者们关于比较优势的分析使用或隐含了以下假设:(1)两国两产品模型。

即假定世界上只有两个国家,生产两种产品。

(2)只有劳动一种要素,所有的劳动是同质的(homogeneous)。

(3)生产成本不变。

单位产品成本不因产量增加而增加,总是和生产单位产品所使用的劳动量成比例。

(4)运输成本为零。

即不考虑运输、进入市场的费用。

(5)没有技术进步。

这意味着技术水平是给定的、不变的,从而经济是静态的。

(6)物物交换。

目的在于排除货币和汇率因素的影响。

(7)完全竞争市场。

但生产要素在国内自由流动,在国际间不能自由移动。

(8)充分就业。

即没有闲置的资源,劳动力作为惟一生产要素得到充分利用。

(9)国民收入分配不变。

即贸易不影响一国国民的相对收入水平,这样有助于说明贸易对整个世界和对每一个个人都是有利的,可以直接衡量贸易利益。

二、相对成本与比较优势比较优势理论的基本思想在于,不同国家生产不同产品会存在劳动生产率或成本上的差异,各国应分工生产各自具有相对优势,即劳动生产率相对较高或成本相对较低的产品,通过国际贸易获得利益。

所谓比较优势(comparative advantage)是指一国(数种产品中)生产成本相对低的优势。

资料-比较优势理论

3.1 比较优势理论李嘉图在斯密的绝对优势理论的基础上,提出了比较优势理论。

李嘉图指出,决定国际贸易的基础是两个国家产品生产的相对劳动成本,而不是绝对劳动成本。

一个国家在生产各种产品时,即使劳动成本都高于其他国家,但是,只要在劳动投入上有所不同,仍可以开展贸易并从中获益。

大卫·李嘉图于1817年出版的《政治经济学及赋税原理》第七章论对外贸易中,在绝对优势理论的基础上,运用两个国家(英国和葡萄牙)、两种产品(毛呢和葡萄酒)这种分析模型,提出决定国际贸易的基础是比较优势而不是绝对优势这一命题,成功地论证了更为广泛的国际贸易现象的客观必然性——建立在劳动价值论基础上的贸易互利性原理,解释了发展程度不同的国家,都能通过参与国际贸易获得利益。

一、比较优势理论的前提假设1.有劳动1种生产要素、2种商品以及2个规模既定的国家;2.两国两种产品的生产函数相同,消费者偏好相同;3.国内劳动要素具有同质性;4.劳动要素可以在两个生产部门间自由流动,但不能跨国流动;5.贸易是自由的,并且不考虑运输成本等任何贸易费用;6.规模收益不变,商品与劳动市场都是完全竞争的。

这一模型也就是所谓的2×2×1模型(两个国家、两种产品、一种要素)。

由于劳动是唯一生产要素,且规模收益不变,所以两国间生产技术差异就表现为两国劳动生产率的差异。

因此,李嘉图的比较优势理论实际上是从技术差异角度来解释国际贸易发生的原因。

二、比较优势论的基本内容大卫·李嘉图在一系列假设前提基础之上指出,所谓比较优势(Comparative Advantage),是指一个国家在国际贸易与国际竞争中提供某种商品比提供其他商品相对来说更为便宜合算。

为了说明比较优势,大卫·李嘉图曾在《政治经济学及赋税原理》中举了一个通俗的例子:“如果两个人都能制鞋和帽,其中一个人在两种职业上都比另一个人强一些,不过制帽时只强1/5或20%,而制鞋时则强1/3或33%。

李 嘉 图 模 型

三、相对价格和供给 1、Pc/Pw>aLC/aLW :只生产布。 2、Pc/Pw<aLC/aLW :只生产麦。 3、Pc/Pw=aLC/aLW :既生产麦又生产布。 结论:不存在国际贸易时,商品的相对价格 等于它们的相对单位劳动投入。

四、单个要素世界中的贸易 1、假定外国的单位劳动投入分别为a﹡LC、 a﹡LW ,且aLC/aLW< a﹡LC/a﹡LW,即本 国有生产布的优势。 2、此时,本国出口布进口麦,直到两国相 对价格相等时为止。

2.3

多产品下的比较优势

一、贸易模式 1、单位劳动投入比例的排序: aL1/a’L1<aL2/a’L2< aL3/a’L3< aL4/a’L4… 贸易模式将唯一取决于两国间的工资率的比 例,即W/W’. 2、各国生产产品的规则:aL1/a’L1 >W/W’,本 国生产; aL1/a’L1 <W/W’,外国生产。 也可以比较两国生产成本WaL1 和W’ a’L1

2.5

提供曲线与国际均衡

一、提供曲线 表示给定相对价格下一国贸易的实际活动, 即进出口量。 二、国际均衡 两国提供曲线的交点。

二、国际贸易理论主要探讨的问题 1、为什么会产生国际贸易? 2、国际贸易对一国会造成什么样的影响? 3、哪些因素会影响国际贸易?

三、国际贸易理论的发展脉络 1、1776, Smith, Absolute Advantage; 2、1817, Ricardo, Comparative Advantage; 3、1919&1939, H-O, Factor Endowment; 4、1940-,

3、International Economics: Inter-country, Globe; International Trade, International Investment, International Finance.

国际贸易 (保罗克鲁克曼)李嘉图模型问题思考

李嘉图模型中,在没有贸易,且市场是完全竞争 的前提下,用生产可能性边界及无差异曲线分析 母国均衡的形成,并验证在均衡点小麦的机会成

本是否等于其相对价格。

陈述人:进化吧小学渣 小组成员:进化吧小学渣

目录

01

母国均衡形成分析

02

验证在均衡点 小麦的机会成本 是否等于其 相对价格

PART 1

该产品价格(小麦的价格P(w)和布的价格P(c))。

也就是说,在小麦产业,劳动一直会被雇用直到工资等于P(w)•MPL(w)为止,在布

这个产业,劳动一直会被雇用直到工资等于P(c)•MPL(c)为止。这也就是小麦行业

与布行业的均衡点

这里涉及到劳动的边际生产力递减规律:在技术给定和其他要素投入不变的情况下, 连续增加某一种要素的投入所带来的总产量的增量在开始阶段可能会上升,但迟

早会出现下降的趋势,这就是边际生产力递减规律。这也是随着劳动力的增加,

每小时生产的价值的增加量会递减的原因。

又因为产业间的工资是相等的,于是我们可以得到这个式子:

P(w)•MPL(w)=P(c)•MPL(c) 重新整理可得: P(w)/P(c)=MPL(c)/MPL(w)

P(w)/P(c)=MPL(c)/MPL(w)

3.总体均衡:生产可能性曲线和社会无差异曲线相切,产品生产的机会 成本=产品消费的边际替代率。

验证均衡点的小麦的机会成本等于其相对价格:

可用间接的方法求得小麦和布的价格。

观察工资如何决定:在竞争性的劳动力市场,企业会雇佣工人直至多增加一小时的

劳动成本(工资)等于多增加一小时生产的价值为止。

于是这增加的一小时劳动的价值等于这一个小时所生产的产品数量(边际劳动产出)

第2章李嘉图模型

共计

3斤

3尺

6单位

国际经济学· 第2章 7

对绝对优势理论的评价 优点:

a)揭示了两国之间贸易产生的原因在于两国之间 存在绝对成本差异 b)反映了按绝对优势分工,参与者都获得更多利 益这样的规律

缺点

不能解释现实中所有国家之间国际贸易的基础, 假如一个国家在所有部门的生产成本上都处于绝对劣势 (优势)的话,那该怎么办呢?

经 邦

济 世

国际经济学· 第2章 28

三、单一要素世界中的贸易

数字例子

世界相对供给和相对需求

奶酪的相对价格, PC/PW

从我们的前面的例子, 我们得到: QC + 2QW = 120

经 邦

济 世

国际经济学· 第2章 21

二、单一要素经济

本国的生产可能性边界

本国葡萄 酒产量, QW (加仑)

aLCQC + aLWQW = L

Qw aL C L Qc aL W aL W

L/aLW

P

斜率的绝对值等于用葡萄酒衡量 的奶酪的机会成本

济 世

国际经济学· 第2章 16

一、比较优势

比较优势:如果一个国家在本国生产一种产品的机会成本 (用其他产品来衡量)低于在其他国家生产该种产品的机 会成本的话,则这个国家在生产该种产品上就具有比较优 势。 在南美玫瑰具有相 对低的机会成本. 万支玫瑰 万台计算机 在美国电脑具有相 对低的机会成本. -1000 +10 美国 通过比较两个国家 +1000 -3 南美 在玫瑰和电脑上的 0 +7 合计 生产可以看到贸易 使双方都受益

经 邦 济 世 国际经济学· 第2章 26

三、单一要素世界中的贸易

李嘉图模型共29页文档

单位产品成本

相对成本

A

3

B

4.5

C

4.5

D

6

E

7.5

1

1/3

2

4/9

3

2/3

6

1

10

4/3

2.3 李嘉图模型的扩展

2.3.2 多种产品模型

引入货币媒介的多种产品模型: 在不考虑汇 率或假定汇率为1:1的情况下,将一国所有商品 的比较劳动生产率由高到低排列,该国对于比较 劳动生产率高于相对工资率的产品的生产具有比 较优势,并将生产和出口该种产品。

古典李嘉图模型的缺陷:完全专业化的推断不符 合各国的实际。

2.2.2 李嘉图模型的新古典阐释

X

商

p1

品

C1 S0进口源自p0S1出口

S0自给自足的均衡; S1, C1贸易均衡

Y商品

2.2.3 李嘉图定理

在开放经济中,每个国家将出口其享有比较 劳动生产率优势的产品。

当ax/ay<a*x/a*y 其中: ax为本国生产x的单位产品劳动 Pa=ax/ay为本国x产品的相对价格 本国将出口x进口y 上式为李嘉图条件的比较劳动生产率形式

商品种 类

A B C D E

2.3 李嘉图模型的扩展 2.3.2 多种产品模型

物物交换的多种产品模型

美国 单位产品劳

动 2 3 3 4 5

单位产品劳 动 1 2 3 6 10

英国

相对成本

0.5 2/3 1 1.5

2

比较劳动生产率

(Qx/Lx)/(Qx/Lx)*

2

1.5 1 2/3 0.5

2.3 李嘉图模型的扩展 2.3.2 多种产品模型

2.3 李嘉图模型的扩展 2.3.3 运输成本的讨论

李嘉图模型 精品

2.2 劳动生产率与比较优势

这样的分工和贸易对两国的相对工资率有隐 含的意义:相对工资率处于相对生产率之间, 而相对生产率是由两国各自的成本优势(绝 对优势)决定的。

2.3 多产品下的比较优势

贸易模式 假设:两个国家,一种要素,N种商品,技 术由每个商品的单位劳动投入表示。单位劳 动高投 排入 列::本国aLi;外国a*Li 。aLi / a*Li从低到 aL1 / a*L1 < aL2 / a*L2 < … < aLN / a*LN。

2.2 劳动生产率与比较优势

哪个部门的小时工资率高(或者说相对价格 大于机会成本)就生产哪种产品:

1、 PC/ aLC > PW /aLW 或 PC/PW>aLC/aLW, 专门生产布。 2、 PC/ aLC < PW /aLW 或 PC/PW<aLC/aLW ,专门生产麦。 3、 PC/ aLC = PW /aLW 或 PC/PW=aLC/aLW ,都生产。

这时,如果允许贸易,会 不会发生贸易?

2.2 劳动生产率与比较优势

允许贸易后,价格就不再完全由国内因素决 定。贸易会进行到两国相对价格相等时为止。

1、展开贸易后,价格 由什么决定? 2、贸易会不会无限止 地进行下去?

2.2 劳动生产率与比较优势

贸易后相对价格的确定

1、国际相对价格的确定与其他价格一样,由供 给与需求决定,但要进行一般均衡分析。

2、要确定两种商品的相对价格,就要知道它们 的相对供给和相对需求。

2.2 劳动生产率与比较优势

贸易后相对价格的确定

(1)相对需求曲线与一般需求曲线相似,它 向下倾斜体现了替代效应(图3) 。

相对供给曲线的形状为 什么那么奇怪?

第3章 李嘉图模型、相互需求与国际贸易 《国际经济学教程》PPT课件

3.3 相互需求方程式

国际交换比例与两国获利

X︰Y

A国获利

1︰1.5

0

1︰1.6

0.1单位Y

1︰1.7

0.2单位Y

1︰1.8

0.3单位Y

1︰1.9

0.4单位Y

1︰2.0

0.5单位Y

1︰1.5为A国的国内交换比例(X︰Y) 1︰2.0为B国的国内交换比例(X︰Y)

B国获利 0.5单位Y 0.4单位Y 0.3单位Y 0.2单位Y 0.1单位Y

aX=1/3 aY=1/6

9 0

1 1 3 0 +2 -1

B国 12 2

bX=1/12 bY=1/2

0 14

1 1 0 7 -1 +6

世界

2 2 3 7 1 5

3.1 李嘉图模型 (二)比较优势

aX / aY bX / bY

aX / aY bX / bY

X的劳动投入量 Y的劳动投入量

X的劳动生产率 Y的劳动生产率

提供曲线的形状: 用A国国内对X的替代效应(substitution effect)和收入效应 (income effect)来解释。

Y

E2点以前,替代效应大于收入效 应,随着PX/PY的上升,X出口增 加; E2点以后,替代效应小于收入效 应,随着PX/PY的上升,X出口减 少。

提供曲线的弹性(进口需求弹 性):富有弹性、单元弹性、缺 乏弹性

2. B国提供曲线的推导与形状

出口Y

Y

E2′ E1′

Y

P0′

P1′

P2′

E2′ E1′

D2′ D1′

O0

E0′

C2′

C1′

P2′

P0′ P1′

国际经济学之李嘉图模型

封闭均衡

中国:100X,25Y;价格1X=0.25Y;工资:0.25Y或1X

米国:62.5X,50Y;价格1X=0.8Y;工资:0.8Y或1.25X

开放均衡

200X,100Y;世界市场价格:1X=0.5Y 中国:生产200X,0Y;出口100X,进口50Y; 消费:100X,100Y; 工资:200个劳动力生产200X,相当于1X或0.5Y 米国:生产0X,100Y;出口50Y,进口100X; 消费:100X,50Y; 工资:100个劳动力生产100Y,相当于1Y或2X

2.4 多个国家或多种产品贸易模型

• 一、两种产品多个国家

• 将各国生产X的相对成本从小到大进行排列:

•

L X L X L X . . . Y L Y L Y 1 L 2 N

• 处于第1国与第N国之间的国家出口什么进口什么,现 在取决于国际市场上X的相对价格

单位产品X的要素投入量(XLX) 产品X的相对成本 品 Y) = ----------------------------------单位产品Y的要素投入量(XLY) (相对于产

(3)机会成本:

减少的X产量()

Y的机会成本 =

--------------------------------增加的Y产量()

与那些因素有关? 中国的贸易条件?你能提出那些问题?

开放条件下的工资

• 国际市场价格:1X=0.5Y 中国:200个劳动力生产200X,相当于世界市 场50Y;工资为1X或0.5Y 美国:100个劳动生产100Y,相当于世界市场 200X,工资为2X或1Y

四、理论的局限性

表2.4 中美两国的生产可能性(2)

表2.5 中美两国的相对劳动生产率(1)

3 李嘉图模型

―*‖ 代表外国的变量

• 假设本国在生产就和奶酪方面都更有效 率. • 在所有方面具有绝对优势:

aLC

< a*LC and aLW < a*LW

• 但它只在一个产品上具有比较优势—与 用于其他的生产相比,生产该产品最有 效地利用了资源.

• 即使一国在所有产品上都有绝对优势(绝 对劣势), 它仍可从贸易中获益 • 计算存在贸易时的相对价格:

• 最有效地利用了其资源

• 与生产其他产品比,美国在生产电脑方 面更有效地利用了资源。

• 南美在生产玫瑰方面更有效地利用了资 源。 • 假设开始时南美生产电脑,美国生产玫 瑰 ,两国都消费电脑和玫瑰。 • 两个国家会变得更好吗?

比较优势和贸易

Millions of Roses U.S. Ecuador Total -10 +10 0 Thousands of Computers +100 -30 +70

比较优势和机会成本

• 李嘉图模型使用机会成本和比较优势的概念.

• 生产的机会成本用来度量不生产其他产品的成 本。

• 当一国利用资源生产和提供服务时,它会面临 机会成本。

• 例如, 有限的工人即可被雇用来生产玫瑰,也 可生产电脑 。

生产电脑的机会成本:没有生产出的玫瑰的数量

生产玫瑰的机会成本:没有生产出的电脑的数量.

南美生产1000万玫瑰:30,000 computers

美国生产1000万玫瑰: 100,000 computers

• 美国在生产电脑方面机会成本较低.

南美:生产

3万电脑 vs. 1000万玫瑰.

美国:

生产 10万电脑 vs.1000万玫瑰

大卫·李嘉图的货币数量理论

内容提要:首先,本文考察了金块论争的历史背景——十九世纪初英国的经济状况,并简要介绍了李嘉图分析方法的特点,其次,详细阐述了李嘉图对当时货币制度的一些政策建议及其货币数量论的观点,其中我们将看到很多当代货币理论问题的影子,充分体现了货币理论研究的连续性。

一、引言李嘉图作为一个活跃的经济学家的生涯仅仅持续了14年(1809-1823),最初便是以一个货币理论家的身份出现的。

从1809年到1813年,他的经济学著作——出版物和通信——主要处理的是那个时代的货币论争,李嘉图的货币思想在这一段时间内基本形成。

由于拿破仑的战车不停地在欧洲大陆上驰骋,英国被迫于1793年向法国开战,为维持大陆上的盟国和自己部队的军事支出,政府大规模的向英格兰银行透支,使该行的金银储备不断流出,成为私人财产。

于是英格兰银行在1795-1796年间一再紧缩纸币发行,结果造成流通手段不足,迫使政府不得不发行国库券以减轻压力。

由于波那巴势力的扩张,英国军费支出不断增加,终于在1797年二月间引起了对英格兰银行的挤兑,为防止整个银行系统陷入危机,英国于是年5月颁布“枢密院命令”暂时中止了英格兰银行用黄金赎回它所发行的银行券的义务,原打算6月即告终止,结果一直拖到1821年。

英格兰银行在这一段时间内获得了大量发行不可兑换纸币的权力,流通中的纸币大大的超过了实际的货币需要量,导致纸币贬值,即英镑汇率下降和用纸币计算的金价上升。

在限制兑换的最初两年黄金的价格还维持在法定平价,到1799年开始上涨,1804年又差不多回到了正常水平,一直持续稳定到1808年。

但在1809年金价又开始急剧上升。

第一次金价的上涨曾经引起了很多争章,其中包括桑顿的《纸币的信用》,同样地,从1809年开始的这次黄金涨价也引起了金价问题的论战。

这就是历史上著名的“金块主义”和“反金块主义”的论争,李嘉图是金块主义的代表人物,1809年8月29日他在晨报上匿名发表了他的第一篇论文《黄金的价格》,当时并没有引起什么人的注意,在这篇文章中,他指出,纸币贬值和价格上涨的原因在于英格兰银行发行的纸币(银行券)过多,金块的升水即证明了这一点,他竭力主张恢复原先的金本位,“我竭力希望我们能及时回头,恢复我国通货原来久已存在的健康状态,因为离开这种状态就会产生现有的危害和未来的破坏。

第二章李嘉图模型

Copyright © 2003 Pearson Education, Inc.

Slide 1-15

上述关系显示,如果奶酪的相对价格(PC / PW )

超过了它的机会成本(aLC / aLW),,即则本国将 专门生产奶酪。(或 PC/aLC>PW/aLW)

Slide 1-27

2、另一种分析贸易互利性的方法是研究贸 易如何影响消费。 • 消费可能性边界表明一个国家所能消费的各种

产品的最大数量。

• 在不存在贸易的情况下,消费可能性边界和生

产可能性边界重合。

• 而贸易扩大了两国的消费可能性边界。

Copyright © 2003 Pearson Education, Inc.

Copyright © 2003 Pearson Education, Inc. Slide 1-8

三、小结

以上分析: 如果每个国家能够出口它具有比

较优势的产品,那么两国都能够从贸易中获 益。

那是什么决定了比较优势呢?

Copyright © 2003 Pearson Education, Inc.

Copyright © 2003 Pearson Education, Inc. Slide 1-11

一、生产可能性边界

• 本国经济的生产可能性边界可以用以下等

式表示: aLCQC + aLWQW = L

• 假如:aLC =1,aLW =2, L=120

QC + 2QW = 120

Copyright © 2003 Pearson Education, Inc.

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

The true meaning of David Ricardo’sfour magic numbersAndrea Maneschi *Department of Economics,Vanderbilt University,Nashville,TN,USAReceived 17October 2002;received in revised form 1November 2002;accepted 20November 2002AbstractThe four numbers in David Ricardo’s example of comparative advantage have been traditionally interpreted as unit labor coefficients in the production of wine and cloth in UK and Portugal.A recent interpretation suggests that they represent instead the labor needed to produce the amounts of wine and cloth actually traded.Ricardo’s four numbers are shown to yield each country’s gains from trade by simply subtracting two of the numbers from the other two.Since the numbers also indicate each country’s comparative advantage,Ricardo established a close connection between comparative advantage and the gains from trade.D 2003Elsevier B.V .All rights reserved.Keywords:David Ricardo;Comparative advantage;Gains from tradeJEL classification:F10;B121.IntroductionDavid Ricardo’s famous paragraphs in his Principles of Political Economy and Taxation of 1817formulating the principle of comparative advantage have often been quoted:The quantity of wine which she [Portugal]shall give in exchange for the cloth of England,is not determined by the respective quantities of labour devoted to the production of each,as it would be,if both commodities were manufactured in England,or both in Portugal.0022-1996/$-see front matter D 2003Elsevier B.V .All rights reserved.doi:10.1016/S0022-1996(03)00008-4*Tel.:+1-615-322-2993;fax:+1-615-343-8495.E-mail address:andrea.maneschi@ (A.Maneschi)./locate/econbaseJournal of International Economics 62(2004)433–443England may be so circumstanced,that to produce the cloth may require the labour of 100men for one year;and if she attempted to make the wine,it might require the labour of 120men for the same time.England would therefore find it her interest to import wine,and to purchase it by the exportation of cloth.To produce the wine in Portugal,might require only the labour of 80men for one year,and to produce the cloth in the same country,might require the labour of 90men for the same time.It would therefore be advantageous for her to export wine in exchange for cloth.This exchange might even take place,notwithstanding that the commodity imported by Portugal could be produced there with less labour than in England.Though she could make the cloth with the labour of 90men,she would import it from a country where it required the labour of 100men to produce it,because it would be advantageous to her rather to employ her capital in the production of wine,for which she would obtain more cloth from England,than she could produce by diverting a portion of her capital from the cultivation of vines to the manufacture of cloth.Thus England would give the produce of the labour of 100men,for the produce of the labour of 80.(Ricardo,1817,pp.134–135)These paragraphs contain what Paul Samuelson (1969)referred to as the ‘four magic numbers’denoting the amounts of labor needed to produce wine and cloth in UK (120,100)and Portugal (80,90).The traditional interpretation of these numbers is that they represent the amounts of labor needed to produce one unit of each commodity in each country,that is,that they are labor input–output coefficients.This interpretation appears in nearly all textbooks of international trade,where the ‘Ricardian’model,presented as the simplest representation of the rationale for trade,is based on fixed labor coefficients.While most authors do not quote from Ricardo’s Principles or use his numbers,others illustrate this model by explicit reference to the four numbers.1With the additional assumption that these coefficients are constant,the textbook Ricardian model yields linear production possibility frontiers and complete specialization in both countries (except that if one of the countries happens to be ‘large’,it remains nonspecialized).Present-day textbooks can cite illustrious precedents for this interpretation of the Ricardian model.For example,Gottfried Haberler (1936,p.128)began his analysis of the theory of comparative cost by asserting that ‘‘In chapter VII of his Principles he [Ricardo]gives the following celebrated example:In England a unit of cloth costs 100and a unit of wine 120units of labour;in Portugal a unit of cloth costs 90and a unit of wine 80units of labour’’.Jacob Viner (1937,p.445)presented a table containing the same four numbers,described as the amounts of ‘labor required for producing a unit’of cloth and wine in UK and Portugal.Basing himself on the same interpretation of Ricardo’s passage,John S.Chipman criticized him for faulty logic:the second paragraph quoted above ‘‘is a non1Caves et al.(1993),Kenen (1994)and Krugman and Obstfeld (2000)are examples of the former approach;Appleyard and Field (2001)and So ¨dersten and Reed (1994)of the latter.Appleyard and Field present Ricardo’s four numbers in a table (p.29)titled ‘‘Ricardian Production Conditions in England and Portugal’’,while So ¨dersten and Reed show a table (p.6)that identifies them as ‘‘labour cost of production (in hours)’’.A.Maneschi /Journal of International Economics 62(2004)433–443434A.Maneschi/Journal of International Economics62(2004)433–443435 sequitur,since nothing so far has been said about Portugal;indeed,the argument could be turned around merely by redefining the units of measurement’’.The first two sentences of the third paragraph are‘‘equally unsatisfactory,except when read in conjunction with the first’’(Chipman,1965,pp.479–80).Other authors,including the present writer(Man-eschi,1998,p.53),have echoed Chipman’s interpretation.A troubling aspect of this criticism is that it implies an illogical(or,at the very least,careless)thought process on the part of the master logician of political economy.Since many international economists believe that comparative advantage was Ricardo’s most significant contribution to classical political economy,it is unfortunate to have to qualify one’s admiration of his formulation of this principle by pointing out its imperfections.Section2sets out a new interpretation by Ruffin(2002)of Ricardo’s numerical example,which absolves him of any such criticism and presents the first clear interpre-tation of the meaning of the four magic numbers.Ruffin,however,did not expand on how Ricardo’s formulation of comparative advantage is intimately related to the gains from trade,as I wish to argue in this article.Ricardo’s measure of the gains from trade is consistent with what Viner named the‘eighteenth-century rule’characterizing such gains. Section3shows that the gains from trade according to this rule are obtained simply by subtracting two of the four numbers from the other two.The concluding Section4 examines the reasons why the new interpretation of Ricardo’s four numbers was over-looked for so long,and how the adoption of the standard interpretation might have affected the evolution of the theory of international trade.2.A new interpretation of Ricardo’s four numbersA recent reinterpretation of the above passage from Ricardo’s Principles has cast a new light on it,and at the same time rescued Ricardo from the charge of inconsistency or carelessness.In fact,it shows to great advantage the revolutionary character of Ricardo’s contribution.Ruffin(2002)convincingly argued that the four labor input numbers presented by Ricardo are not input–output coefficients,but rather the quantities of labor needed to produce the amounts of wine and cloth actually traded by UK and Portugal.This is implied by Ricardo’s usage of the terms‘the cloth’and‘the wine’in the second paragraph quoted above,which refer to the amounts traded that were mentioned in the first paragraph.As Ruffin states,Let X be‘the quantity of wine’that is traded for Y units of cloth.If England requires 120men for one year to make X units of wine and100men to make Y units of cloth,‘‘England would therefore find it her interest to import wine,and to purchase it by the exportation of cloth.’’He[Ricardo]then went on to Portugal,which required80men to produce the wine and90to produce the cloth.Obviously,Portugal would save10men producing X wine and trading it for England’s Y cloth.(Ruffin,2002,pp.741–742) He adds(p.742)that‘‘Ricardo’s proof is elegant,simple,and sublime.It not only uses the separation property of the law of comparative advantage,but the logical structure applies to any number of goods or countries,unlike textbook expositions’’.Further reflection on Ruffin’s novel interpretation of Ricardo’s numerical example has convinced me that it can be developed so as to yield new insights into the relationship between comparative advantage and the gains from trade.Given that X units of Portuguese wine are traded for Y units of English cloth (Ricardo never assigned values to X and Y ),the unit labor coefficients for wine and cloth in UK and Portugal are given by the following table:The terms of trade are Y /X units of cloth per unit of wine.In UK the opportunity cost of wine is 1.2Y /X units of cloth,while in Portugal it is 0.89Y /X ,so that Portugal has a comparative advantage in wine.Instead of following this procedure in terms of the unknown variables X and Y ,economists have tended to infer the pattern of comparative advantage,and hence the direction of trade,by interpreting the ‘four magic numbers’as unit labor coefficients.They used them to derive the autarky price ratios for the two countries,and offered reasons that explain why the terms of trade usually lie between them.Ricardo is often mildly reprimanded for announcing the terms of trade in the fourth paragraph of the above passage without explaining their determination,a task later undertaken by John Stuart Mill.With the new interpretation of the four numbers,we see that Ricardo’s method was much more direct.By stipulating from the start that certain quantities of wine and cloth exchange for each other in the trade equilibrium,he essentially began with the terms of trade,and went on to specify domestic exchange ratios in the two countries that are consistent with them and lie on either side of them.2The fact that UK uses 100men to produce the cloth she exports,whereas she would need 120men to produce the wine she imports,immediately establishes her comparative advantage in cloth without requiring any knowledge of Portugal’s labor inputs.Likewise,Portugal’s comparative advantage in wine is established by her requiring 80men to produce enough wine to pay for the cloth which she would otherwise produce with the labor of 90men.Thus,in the same breath,Ricardo informed his readers not only about the pattern of comparative advantage,but about each country’s gains from trade.In the case of UK,these gains are given by the difference between the two numbers he cited for wine and cloth,120À100=20,while in the case of Portugal they amount to 90À80=10.They express the labor that each country saves whenWineCloth UK 120/X100/Y Portugal80/X 90/Y 2Ruffin (2002)argues persuasively that Ricardo’s primary concern (as expressed in the first paragraph of the passage from the Principles quoted above)was not how the commodity terms of trade are determined,but the fact that the double factoral terms of trade between two trading countries are usually not equal to unity.While it is theoretically possible (though unlikely)that they equal unity when each country has an absolute advantage in its export commodity,this is impossible when (as in Ricardo’s numerical example)Portugal has an absolute advantage in both commodities.Hence the labor theory of value cannot be relied on as a guide for the determination of international prices.A.Maneschi /Journal of International Economics 62(2004)433–443436A.Maneschi/Journal of International Economics62(2004)433–443437 it trades with the other instead of remaining self-sufficient.These gains,of course,can be realized only if it specializes according to its comparative advantage.Gains from trade accrue to each country as long as the amount of labor embodied in its exports falls short of the labor it would need to produce the commodities it imports.This guarantees that the terms of trade fall inside the cone spanned by the two autarky price ratios.The economy of thought and the richness of results to be drawn from Ricardo’s example are truly astounding.The way in which Ricardo expressed the gains from trade is consistent with a long tradition that preceded him,denoted by Viner as the‘eighteenth-century rule’for the gains from trade.It states that‘‘it pays to import commodities from abroad whenever they can be obtained in exchange for exports at a smaller real cost than their production at home would entail’’(Viner,1937,p.440).It therefore reflects the benefits of trade viewed as an indirect method of production.Consider this in the context of Ricardo’s two-good English economy,where good C(cloth)is exported,good W(wine)is imported,and labor is the only factor of production.Let the superscript t represent the trade equilibrium.If a i is the amount of labor needed to produce one unit of good i,one unit of labor can produce either1=a W units of wine or1=a C units of cloth,which can be exchanged forð1=a CÞðp C=p WÞt units of wine at the terms of tradeðp C=p WÞt:This trade is beneficial at the margin as long asð1=a CÞðp C=p WÞt>1=a W;ð1Þorðp C=p WÞt>a C=a W¼MRT;ð1aÞsince the marginal rate of transformation(MRT)equals the ratio of the marginal costs of producing cloth and wine.The economy produces more cloth untilðp C=p WÞt¼MRT;so that the terms of trade line is tangent to the transformation curve,or until it specializes fully in cloth.The assumption of increasing opportunity costs in the transformation of wine into cloth is used and justified in Section3.It is more general than the textbook version of the Ricardian model,where the transformation curve is linear and each trading economy becomes fully specialized.3.Ricardo’s measure of the gains from tradeRather than basing the gains from trade on a unit of labor shifted from the importable to the exportable sector,as implied by(1),Ricardo expressed these gains with reference to a country’s total imports and exports.To express his measure algebraically,assume that m W units of wine,rather than produced directly,are imported in exchange for exports x C of cloth.These amounts are shown in Fig.1,where the autarky equilibrium is at A and the terms of trade are given by the slope of PC.If consumption occurs at point C,the trade triangle is CBP,its sides measuring exports BP of cloth and imports CB of wine.If y i is the output of commodity i and S i the amount of labor used in sector i,let y C¼fðS CÞand y W¼gðS WÞbe the production functions of cloth and wine in UK.Assume that f V ;g V >0;f W ;g W V 0;and either f W or g W <0;so that there are diminishing returns to labor in the production of at least one good.If L is the economy’s fully employed labor force,L ¼S C þS W ¼f À1ðy C Þþg À1ðy W Þ,where f À1and g À1are the inverse functions of f and g .This equation yields the economy’s concave transformation curve shown in Fig.1.3If d t i represents the demand for commodity i in UK when it trades with Portugal,theamount of labor required to produce x C ¼y t C Àd t C cloth exports is f À1ðy t C ÞÀf À1ðd t C Þ:The labor that would be required to produce m W ¼d t W Ày t W wine imports is g À1ðd t W ÞÀg À1ðy t W ).According to Ricardo,the amount of labor saved (LS)through trade is thereforeLS ¼g À1ðd t WÞÀg À1ðy t W ÞÀf À1ðy t C Þþf À1ðd t C Þ¼120À100¼20men :ð2Þ3Findlay (1974)obtained a concave transformation curve when he assumed constant returns to labor in the manufacturing sector ðf W ¼0Þand diminishing returns in the agricultural sector ðg W <0Þ:The technological assumptions made in this section are analogous to those underlying the Ricardo–Viner (sometimes called ‘specific-factors’)model,which assumes that each sector of the economy uses a factor of production specific to it as well as a ‘mobile’factor,usually taken to be labor,common to all sectors.Krugman and Obstfeld (2000)discuss this model in the chapter immediately following that devoted to the ‘Ricardian’model.In a box titled ‘Specific Factors and the Beginnings of Trade Theory’,they state that ‘‘Yet almost surely the British economy of 1817was better described by a specific factors model than by the one-factor model Ricardo presented’’(p.58).They implicitly assume that the agricultural (corn)sector uses land as its specific factor,that capital is specific to the manufacturing sector,and that both sectors share the mobile factor,labor.They go on to discuss the distributional implications of the Corn Laws for landlords and capitalists,and the reasons for Ricardo’s opposition to theselaws.parative advantage and Ricardo’s measure of the gains from trade.A.Maneschi /Journal of International Economics 62(2004)433–443438A.Maneschi/Journal of International Economics62(2004)433–443439 Since L¼fÀ1ðy t CÞþgÀ1ðy t WÞ;(2)can be rewritten asLS¼fÀ1ðd t CÞþgÀ1ðd t WÞÀL:ð2aÞA measure of the gains from trade often used in neoclassical trade theory is the Hicksian equivalent variation(EV),defined as the amount of income that must be added to national income evaluated at autarky prices at point A in order to attain the level of welfare realized at point C.If the‘equivalence’underlying the equivalent variation is of the Slutsky type,EV S,the community is able to buy the free-trade consumption bundle itself at the autarky prices,so thatEV S¼p aðd tÀd aÞ;ð3Þwhere p and d are the price and demand vectors,and the superscript a represents the autarky equilibrium.4If cloth is the numeraire and CH is drawn parallel to AG,EV S is measured in Fig.1by the difference GH between the values of the consumption bundles at C and A at the autarky prices given by the slope of the line AG.5An alternative measure of the gains from trade is the compensating variation(CV),defined as the income that must be taken away when the community consumes bundle C at free trade prices in order to reduce welfare to its autarky level.A measure that is analogous to both the EV and the CV is the difference between the amount of labor needed to produce the consumption bundle under trade(d t C;d t W)and that needed to produce the bundle(d a C;d a W)consumed under autarky.It is the additional labor force,over and above L;that would be needed in autarky to produce the consumption bundle available under free trade.It is here denoted as the equivalent variation in terms of labor,or EV L.It differs from both the EV and CV since it is expressed in terms of the labor input rather than of expenditure.Since in autarky d a C¼y a C;d a W¼y a W;and fÀ1ðy a CÞþgÀ1ðy a WÞ¼L;this measure is given byEV L¼fÀ1ðd t CÞþgÀ1ðd t WÞÀfÀ1ðy a CÞÀgÀ1ðy a WÞ¼fÀ1ðd t CÞþgÀ1ðd t WÞÀL:ð4ÞThis is identical to the value of LS in(2a),and therefore to the measure proposed by Ricardo.The beauty and appeal of Ricardo’s measure is that it coincides with EV L,and is thus analogous to the neoclassical measures of the gains from trade,the equivalent and compensating variations.The transformation curve shown in Fig.1,characterized by increasing opportunity costs in transforming one commodity into the other and incomplete specialization,is4On the difference between Hicks and Slutsky compensations,see Varian(1992,pp.135–137).While not shown in Fig.1,it is clear that the Slutsky EV usually exceeds the Hicksian EV.5Note that the Slutsky equivalent variation is smaller than p a m;the value of net imports at autarky prices, where m is the economy’s net import vector.The value of p a m is known to be positive thanks to the generalization of the concept of comparative advantage by Deardorff(1980)and Dixit and Norman(1980).In terms of cloth,it is given in Fig.1byÀx Cþðp W=p CÞa m W¼ÀBPþðp W=p CÞa CB¼ÀBPþðBH=CBÞCB¼PH;which exceeds the value of the equivalent variation given by GH.consistent with Ricardo’s statement that ‘‘a country possessing very considerable advan-tages in machinery and skill,and which may therefore be enabled to manufacture commodities with much less labour than her neighbours,may,in return for such commodities,import a portion of the corn required for its consumption’’(Ricardo,1817,p.136;emphasis added).This implies that some of the corn consumed is produced domestically.The passage from Ricardo’s Principles quoted at the beginning of this article nowhere states or implies that specialization is complete after trade in either UK or Portugal.A concave transformation curve is also ideally suited to portray both the static and the dynamic gains from trade.If the cloth and wine in Ricardo’s example are relabeled as ‘manufactures’and ‘corn’(a term used by the classical economists to denote wheat and other grains),it is easy to show that when the country with a comparative advantage in manufactures imports corn,whose production is subject to diminishing returns,it enjoys an increase in the profit rate caused by a rise in the marginal product of labor in the corn sector (Findlay,1974,1984;Maneschi,1983).A ‘‘rise in the rate of profits’’is mentioned by Ricardo (1817,p.132)as a gain from trade on a par with the static gain discussed above.Since a higher profit rate is associated with a higher rate of capital accumulation,the economy enjoys dynamic gains from trade by moving to a trajectory marked by a higher growth rate.6Another consequence of assuming a concave transformation curve and incomplete specialization is that the trade triangle is much smaller than that associated with a linear transformation curve leading to complete specialization.The smaller volume of trade may explain the relatively small numbers of workers associated with the production of exports and imports in UK (100,120)and Portugal (80,90)in Ricardo’s example.4.Concluding remarksThe gains from trade outlined above,in terms of the amount of labor saved by trading exports for importable goods instead of producing the latter directly,represent the static benefits from exploiting trade as an indirect method of production.In Ricardo’s example,Portugal’s comparative advantage can be deduced from the fact that her relative productivity advantage in wine is 33%,while that in cloth is 10%.Commentators have often speculated on why Ricardo picked his four numbers so that Portugal holds an absolute advantage over UK in producing both commodities.These numbers strike one as especially peculiar with regard to cloth,given that the industrial revolution occurred in UK rather than Portugal.A possible explanation for Ricardo’s choice is that he wished to make the rhetorical point that,even if she were inefficient in producing both commodities,UK could end up garnering the lion’s share (20/30or two-thirds)of the worldwide gains from trade.The new interpretation of Ricardo’s four numbers is consistent with diminishing returns in production,so that a trading economy need not fully specialize in its export good.The6This dynamic interpretation of the gains from trade,consistent with Ricardo’s insistence throughout his Principles of Political Economy that Britain’s corn trade should be liberalized,is stressed in Maneschi (1992).A.Maneschi /Journal of International Economics 62(2004)433–443440A.Maneschi/Journal of International Economics62(2004)433–443441 corollary is that there is a dynamic as well as a static component of the gains from trade. This conforms with Ricardo’s opinion,forcefully expressed in Parliament as well as in his writings,that the Corn Laws led to a decline in Britain’s rate of profit.Their repeal would reverse this trend,since cheaper corn imports would boost the profit rate and restore dynamism to the British economy.If the above interpretation of Ricardo’s four numbers is correct,why did most economists,including some very distinguished ones,7for almost two centuries interpret them instead to be unit labor coefficients in the production of wine and cloth in the two countries?A second and equally challenging question is whether this interpretation distorted in any way the profession’s understanding of the nature of Ricardian comparative advantage.In answering the first question,recall that John Stuart Mill(1844,1848) completed Ricardo’s theory by developing the principle of reciprocal demand as a determinant of the terms of trade.In both his books,he cited paragraphs from his father’s Elements of Political Economy(James Mill,1844)that contained examples of Ricardian comparative advantage relating to English cloth being traded for Polish corn.Just as in Ricardo’s case,James Mill’s four numbers represented the labor needed to produce the amounts actually traded by the two countries.But John l also inserted examples of English broad cloth being exchanged for German linen that were expressed in terms of the domestic and international terms of trade,not in terms of the amounts of labor embodied in the commodities traded.This had the effect of focusing attention on the two trading economies’autarky price ratios as limits within which the terms of trade must lie.It was natural for subsequent economists to assume(in line with Ricardo’s own labor theory of value)that these autarky price ratios were given by labor inputs per unit of output,and that Ricardo’s four numbers represent the four labor coefficients per unit of output needed to calculate them.Ricardo’s failure to speculate on the determination of the terms of trade was viewed as a defect which l’s theory was designed to correct.Given the intellectual prestige carried by Mill’s interpretation of the Ricardian model,subsequent generations of economists followed the same interpretation without bothering to read closely Ricardo’s original wording of the principle of comparative advantage.8A second and related question is whether the standard interpretation of Ricardo’s principle led economists to form a distorted view of Ricardian comparative advantage.As argued above,Ricardo began his example by postulating the equilibrium terms of trade, and went on to assume that the two trading countries’opportunity cost ratios lie on either side of them,without explaining what those ratios depend on.The textbook versions of the Ricardian model invert Ricardo’s own order of presentation by first theorizing about the 7As Ruffin(2002,p.742)points out,Sraffa is an exception to this generalization.He correctly interpreted Ricardo’s paragraphs on comparative costs when he stated that via trade UK‘gains the labour of20Englishmen’, while‘‘Portugal gains the labour of10Portuguese’’(Sraffa,1930,p.541).As noted below,James Mill is another exception.The history of economic thought contains many examples of insights gained by earlier economists that were subsequently lost.Sraffa’s insight of1930(unrelated to his subsequent larger reinterpretation of Ricardo’s work)was ignored for over70years until Roy Ruffin noticed it and brought it to public attention.Perhaps the new view of Ricardo’s four numbers as the amounts of labor embodied in trade flows should be referred to as the Sraffa–Ruffin interpretation.l’s role in diverting attention away from Ricardo’s formulation of the labor embodied in the bundle of traded goods is also underscored by Ruffin(2002,pp.742–743).。