第二语言习得概论ellis全文翻译

第一章 第二语言习得概论(完全版)

二、第二语言习得研究范畴

三、第二语言习得研究与语言学

四、第二语言习得研究与心理学

五、第二语言习得研究与心理语言学

六、第二语言习得与语言教学

二、第二语言习得研究与语言学

语言学 联 系 第二语言习得

第二语言习得 = 语言学的消费者 第二语言习得 = 语言学的贡献者

消费者?

贡献者?

关于“至于”的思考

A

至于 B(NP) , C

二、第二语言习得研究与语言学

语言学 联 系 第二语言习得

第二语言习得 = 语言学的消费者 第二语言习得 = 语言学的贡献者

二、第二语言习得研究与语言学

语言学

联 系

第二语言习得

第二语言习得 = 语言学的消费者 第二语言习得 = 语言学的贡献者

母语者的语言系统 学习者的语言系统、学习者、 习得过程与机制

一、母语 VS 目的语

2、目的语(target language)

• “目的语”,也称“目标语”,一般是指学习

者正在学习的语言。

• 正在学习的母语、第二语言、第三语言……

• 与学习者的语言习得环境无关。

• Eg.在中国学习汉语

在美国学习汉语

二、第一语言 VS 第二语言

• 母语和第一语言 母语:所属种族、社团使用 第一语言:语言习得的顺序 一般母语=第一语言

三、习得 VS 学习

• 隐性知识和显性知识之间是否可以转化?

• 无接口(Krashen 早期观点)

• 有接口(Bialystock) • 什么样的教学有助于知识的转化?

四、第二语言习得 VS 外语习得

主要依据学习者学习目的语的社会环境来区分

1、第二语言习得( Second language acquisition)

第二语言习得理论阅读书目

第二语言习得理论阅读书目1. Ellis.R. The Study of Second Language Acquisition[M].Oxford Univ.Press,1994.2. Ellis.R.Understanding Second Language Acquisition[M].Oxford Univ.Press,1985.3.Krashen.S. & T.Terrell., The Natural Approach: Language Acquisition in the Classroom[M],Oxford:Pergamon,1983.4.Krashen.S. Principles and Practice in Second Language Acquisition[M], New York: PPergamon Press[M],, 1982.5. Brown. H. D. Principles of Language Learning and Teaching. Prentice Hall, Inc[M],1987.6.Cook. V. Second Language Learning and Language Teaching. Beijing: Foreign LanguageTeaching and Research Press[M], 2000.rsen-Freeman,D.and M.Long.An Introduction to Second Language AcquisitionResearch. Beijing: Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press[M], 2000.8.Littlewood.W. Foreign and Second Language Learning. Beijing: Foreign Language Teachingand Research Press[M], 2000.9.O’Malley.J & Chamot. A. U. Learning Strategies in Second Language Acquisition. CambridgeCambridge University Press[M], 1990.10.Ramirez.A. Creating Contexts for Second Language Acquisition. New York: LongmanPublishers[M], 1995.11.Seliger.H. & Shohamy.E. Second Language Research Methods. Oxford: Oxford UniversityPress[M], 1989.12.12. Stern. H. Fundamental Concepts of Language Teaching. Oxford: Oxford UniversityPress[M], 1983.13.蒋祖康,第二语言习得研究,北京:外语教学与研究出版社[M],1999。

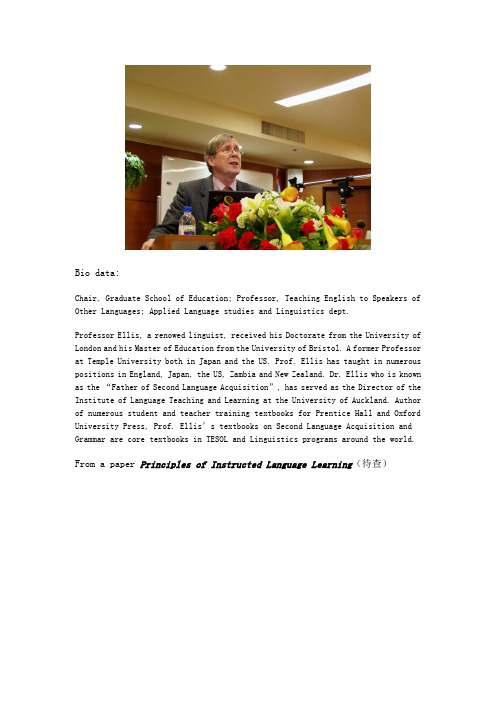

rod ellis

Bio data:Chair, Graduate School of Education; Professor, Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages; Applied Language studies and Linguistics dept.Professor Ellis, a renowed linguist, received his Doctorate from the University of London and his Master of Education from the University of Bristol. A former Professor at Temple University both in Japan and the US. Prof. Ellis has taught in numerous positions in England, Japan, the US, Zambia and New Zealand. Dr. Ellis who is known as the “Father of Second Language Acquisition”, has served as the Director of the Institute of Language Teaching and Learning at the University of Auckland. Author of numerous student and teacher training textbooks for Prentice Hall and Oxford University Press, Prof. Ellis’s textbooks on Second Language Acquisition and Grammar are core textbooks in TESOL and Linguistics programs around the world.From a paper Principles of Instructed Language Learning(待查)Rod ELLIS新西兰奥克兰大学教授Prof.of University of Auckland, New ZealandRod Ellis is currently Professor in the Department of Applied Language Studies and Linguistics, University of Auckland, where he teaches postgraduate courses on second language acquisition, individual differences in language learning and task-based teaching. His published work includes articles and books on second language acquisition, language teaching and teacher education. His books include Understanding Second Language Acquisition (BAAL Prize 1986) and The Study of Second Language Acquisition (Duke of Edinburgh prize 1995). More recently, Task-Based Learning and Teaching early (2003) and (with Gary Barkhuizen) Analyzing Learner Language in (2005) ), were published by Oxford University Press. He has also published several English language textbooks, including Impact Grammar (Pearson: Longman). He is also currently editor of the journal Language Teaching Research. In addition to his current position in New Zealand, he has worked in schools in Spain and Zambia and in universities in the United Kingdom, Japan and the United States. He has also conducted numerous consultancies and seminars throughout the world. Rod Ellis ,上海外国语大学,受聘为国家教育部第八批“长江学者奖励计划讲座教授”,聘任岗位:外国语言文学。

第二语言习得概论ellis全文翻译

第二语言习得概论Rod Ellis 全书汉语翻译引言写这本书的目的是为了全面的解释第二语言习得,我们尽可能的描述理论,而不是提出理论,所以,本书不会有意识地凸显任何一种二语习得的方法或理论作为已经被认可的看法。

其实,现在做到这一点是不可能的,因为二语习得研究还处于初期阶段,仍有许多问题需要解决,当然,我们不可能完全把描述和解说隔裂开来,所以,对于我所选择描述的理论解释时,不可避免地带有我自己的观点倾向。

这本书写给两类读者,一类是二语习得课程的初学者,他们想整体了解二语研究的现状。

二是想明白学习者怎么学习第二语言的教师。

因为是二语习得的初级教程,第一章列出了有关第二语言习得的主要理论观点。

接下来的几章各自阐述一方面的理论观点,然后第10章汇总所有理论以对二语习得的不同理论进行全面研究。

每章后面提供可进一步阅读的参考建议,这可以指引学生进入二语研究快速发展的前沿领域。

但是,应该想到许多读者是第二语言或外语老师,所以本书也应该让他们对课内和课外的二语习得是怎么发生的有一个清楚的认识。

按传统,是教师决定课堂上学生学习什么和按什么顺序学习。

例如,语言教科书就把既定的内容顺序强加给学生学习,这些课本设想书中设计的语言特征出现的顺序和学生能够接受并习得的顺序相同。

同样,教师在制定教学计划时也会这样做,他们认为精选学习内容和把教学内容排序将有利于教学。

但是除非我们确定教师教学计划和学生的习得顺序相符,不然我们不能确定教学内容可以直接有利于学生学习。

教师不仅决定教学的内容和结构,他们也决定第二语言怎么教,他们决定教学法,他们决定是否操练,操练多少,是否纠错和什么时间纠错以及纠到什么程度,教师们根据他们所选择的教学法来处理语言学习过程。

但是,又一次,我们不能确保教师选择的教学法规则和学习者学习语言的进程是相符的,例如,教师可能决定关注语法的正确性,而学习者可能只关注自己的意思是否被理解,不在乎语法是否正确,教师可能关注操练灌输一个一个语言点,而学生却可能整体上把握语言问题,逐渐的掌握在某一相同的时间处理各种语言点的能力,学生所进行的学习可能不是教师的教学法所设想的。

understanding second language acquisition中文版 -回复

understanding second language acquisition中文版-回复“理解第二语言习得”是一个复杂而广泛的研究领域,涉及到了许多不同的因素和理论。

在这篇文章中,我们将一步一步回答关于第二语言习得的问题,并探讨一些相关的研究和实践。

第一步:第二语言习得与第一语言习得的区别首先,我们需要明确第二语言习得与第一语言习得之间的区别。

第一语言习得是指人们在幼年时期无意识地习得的语言,这是一种自然而然的过程。

而第二语言习得则指在成年或青少年时期有目的地学习的第二种语言。

这种习得过程可能会受到第一语言的干扰,因为学习者常常会将第二语言与第一语言产生联系。

第二步:第二语言习得的理论接下来,我们需要了解一些关于第二语言习得的理论。

其中最著名的理论之一是斯汤加提出的“监控模型”。

这个模型指出,学习者在学习第二语言时不仅仅依靠外界的输入,还会使用他们的先前知识和语法规则来“监控”和纠正自己的语言产出。

除了监控模型,还有其他的理论,如克鲁什-斯克拉芙斯基的互动性认知模型和斯莱申格的输出假说。

这些理论提出了不同的观点和解释,以帮助我们更好地理解第二语言习得的过程。

第三步:影响第二语言习得的因素了解第二语言习得的理论后,我们需要看一些影响第二语言习得的因素。

首先是心理因素,如学习者的动机、自信心和态度等。

这些因素可以影响学习者的学习兴趣和投入程度。

其次是社会因素,如学习者所处的语言环境、有无机会使用第二语言的机会等。

一个沉浸式的语言环境可以促使学习者更快地习得第二语言。

还有一些个体差异的因素,如学习者的年龄、学习策略和学习经验等。

这些因素可能会影响学习者对第二语言的习得速度和方式。

第四步:有效的第二语言习得策略在第二语言习得的过程中,学习者可以采用一些有效的学习策略来提高自己的语言水平。

比如,他们可以通过频繁的输入和输出来增加对目标语言的接触和实践。

此外,他们还可以利用记忆技巧、合作学习和自主学习等策略来巩固和加强语言知识。

第二语言习得 (中文版)

第二语言习得 (中文版)第二语言习得是指在已经谙熟自己的母语后开始接触学习另外的一门语言。

这种语言习得与母语习得不同,因为母语即是个人的文化和生活背景的一部分,而第二语言则需要通过各种学习环境、工具和方法才能够完成。

第二语言的学习有其特殊性,因为它需要不同的學習技巧或是包含不同的学习过程。

而且,因为第二语言的习得通常是在成人的时期开始的,所以这种语言习得需要分析并改变人的思维方式习惯。

就像一个中国人学英语,需要用到英语的语法规则,同时又逃不掉中文惯用的方式和表达方式。

为了掌握第二语言,我们需要通过各种途径去了解和学习它。

这些途径包括学校、网上资源、语言交流等等。

最好的途径当然是去一个使用第二语言的国家,并在那里生活,这样可以最好的体验到语言的环境,也能适应新的生活和文化。

对于那些没有这个机会的人,透过各种在线资源来学习和练习也是同样有效的。

第二语言习得可能会改变我们的思维方式和认知水平。

通过学习这门外语,我们可以认识不同的语言文化和习惯,扩宽自己的眼界。

同时,通过不同语言的丰富表达方式,也可以更加深入的理解和描述世界。

第二语言的习得也会对我们的就业竞争力产生积极影响。

因为在全球化的时代背景下,英语已经成为商业和学术合作的重要语言。

如果我们能够掌握这种第二语言,我们的就业机会和工作效率也会更高。

总之,第二语言习得是非常重要和有价值的。

这种习得需要时间、耐心和努力。

不过通过积极的学习和交流,我们能够顺利掌握一门外语,并获得更多的机会和认知。

第二语言习得的过程通常被认为是相对困难的,原因在于以下一些方面。

首先,个体的母语背景、学习历史和文化习惯对于学习另一门语言的效果产生重要影响。

这些因素往往会阻碍个体从母语中摆脱出来进入到新学习的语言环境中。

其次,学习语言的词汇和语法规则是一个长期而复杂的过程。

除了需要内化表达方式外,学习者还需要理解并适应新的文化习惯和社会背景。

而这种适应需要耗费大量的时间和精力。

二语习得引论翻译笔记-第五章

第五章SLA与社会环境【真题:语言社团;反馈】交际能力P100言语沟通民俗学:交际能力:一个说话者在一个特定的语言社团里知道自己需要说什么。

不但包括词汇语音语法结构,还要知道什么时候说对谁说和在既定环境里适当的表达。

还包括说话的人应该指导社会文化方面的知识,应该具有保证顺利地和别人交流的能力。

语言社团:一组人;用同一种语言;因此,多语者属于多个语言社团。

非本族语的人讲话和本地人相差很大,即使他们属于同一个语言社团。

比如包括语言结构组合的不同,对话、写作等规则使用不同,同一个词汇意思不同。

P101外语[FL]:在当地环境下学习二语,没机会与该语言的语言社团进行互动(除非出国),且没有机会完全融入该外语的社会,学习这种语言大多是课业要求。

附加语[AL]P102微观社会因素学习者语言的变异社会语言学家认为语言的变异是指在语言的产出过程中,把语言的不系统的不规则的变化当做次于语言系统规则模式的变异性特点。

交际环境的多个维度:语言学环境:语言形式和功能的成分心理学环境:在语言加工过程中,起始阶段要倾注多少注意力,从控制加工到自动化加工;微观社会环境:环境与互动特征与交际部分相关,并在此过程中被产出、翻译、协商宏观因素:政治背景下,哪种语言应该学习,社会对某种语言的态度。

适应理论[accommodation theory]:说话者会随着说话对象的说话方式改变自己的语调难易。

工作地点影响语言输入的性质和群体认同性。

自然变异:中介语的产物,是习得二语语法的必要步骤Ellis 变异的性质随着学习二语的深入而变化:1.一个简单的形式被用于多种功能2.其它形式一开始会用于中介语3.多种形式被系统化地使用4.无目的的形式被摘除,自由变异的清楚使中介语更加高效P105语言的输入与互动P106一、自然输入的修改语言输入对一语二语都是绝对必要的。

外国式谈话[foreigner talk]:一语学习者对二语学习者说话时调整说话的语气速度来适应二语者的语言。

第二语言习得的基础 翻译

《二语习得导论》第二章第二语言习得研究的基础章节预览我们中的大多数,尤其是以英语为主要语言的国家,即没有意识到多语使用在当今世界是多么的盛行,也没有意识到二语习得的普遍性。

本章我们首先概述下这些观点,然后我们去探索语言学习的本质,一语习得和二语习得一些基本的相似点和差异,以及“语言习得的逻辑问题”。

对这些问题的理解是我们在之后的章节中对二语习得的语言学,心理学和社会视角进行讨论的基础。

理论框架的研究和二语习得最重要的兴趣焦点,包括三个中的每一个视角我们都予以遵循。

(p8)世界第二语言多语习得者是指习得两种或者两种以上语言的能力的人。

(一些语言学家和心理学家称呼具有两种语言能力的人为双语习得者,称呼具有多种语言能力的人为多语习得者。

但我们在此不做这样的区别。

)单语习得者是指只具有一种语言能力的人。

没有一个人可以肯定的说,有多少人是多语习得者,但合理的估计是,至少有世界一半的人口都属于这个类别。

因此,多语习得并不是一个罕见的现象,而是一种在世界大部分地区都会存在的普遍现象。

根据FrançoisGrosjean的观点,这种现象早在人类没有任何语言记录的早期就已经存在了。

多语现象几乎存在于世界上的每一个国家,所以的社会阶层,以及不同的年龄段中。

事实上,很难找到一个真正的单语言社会。

这不仅仅是一个世界范围内的双语现象,它甚至在人类历史上语言出现之初就已经存在。

这很可能是真实的,因为没有任何一个语言群里隔离与其他语言群体而独立存在,人类语言历史上充满着因为语言接触而造成一些形式的双语现象的例子。

(1982:1)鉴于对当前形势的报道,G. Richard Tucker 总结说,世界上双语或多语习得者要比单语人群多很多。

另外,比起在常规部门只学习一种语言的儿童,世界各地更多的孩子们已经获得或者继续学习来获得习得多种语言的能力。

(1999:1)鉴于多语种人群的规模和分布如此广泛,绝大多数科学家竟然把注意力只集中在单语言环境和第一语言习得上,这多少让人有点惊讶。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

第二语言习得概论Rod Ellis 全书汉语翻译引言写这本书的目的是为了全面的解释第二语言习得,我们尽可能的描述理论,而不是提出理论,所以,本书不会有意识地凸显任何一种二语习得的方法或理论作为已经被认可的看法。

其实,现在做到这一点是不可能的,因为二语习得研究还处于初期阶段,仍有许多问题需要解决,当然,我们不可能完全把描述和解说隔裂开来,所以,对于我所选择描述的理论解释时,不可避免地带有我自己的观点倾向。

这本书写给两类读者,一类是二语习得课程的初学者,他们想整体了解二语研究的现状。

二是想明白学习者怎么学习第二语言的教师。

因为是二语习得的初级教程,第一章列出了有关第二语言习得的主要理论观点。

接下来的几章各自阐述一方面的理论观点,然后第10章汇总所有理论以对二语习得的不同理论进行全面研究。

每章后面提供可进一步阅读的参考建议,这可以指引学生进入二语研究快速发展的前沿领域。

但是,应该想到许多读者是第二语言或外语老师,所以本书也应该让他们对课内和课外的二语习得是怎么发生的有一个清楚的认识。

按传统,是教师决定课堂上学生学习什么和按什么顺序学习。

例如,语言教科书就把既定的内容顺序强加给学生学习,这些课本设想书中设计的语言特征出现的顺序和学生能够接受并习得的顺序相同。

同样,教师在制定教学计划时也会这样做,他们认为精选学习内容和把教学内容排序将有利于教学。

但是除非我们确定教师教学计划和学生的习得顺序相符,不然我们不能确定教学内容可以直接有利于学生学习。

教师不仅决定教学的内容和结构,他们也决定第二语言怎么教,他们决定教学法,他们决定是否操练,操练多少,是否纠错和什么时间纠错以及纠到什么程度,教师们根据他们所选择的教学法来处理语言学习过程。

但是,又一次,我们不能确保教师选择的教学法规则和学习者学习语言的进程是相符的,例如,教师可能决定关注语法的正确性,而学习者可能只关注自己的意思是否被理解,不在乎语法是否正确,教师可能关注操练灌输一个一个语言点,而学生却可能整体上把握语言问题,逐渐的掌握在某一相同的时间处理各种语言点的能力,学生所进行的学习可能不是教师的教学法所设想的。

为了发现学习者是怎么使用他已经掌握的语言数据,我们需要考虑学习者使用的策略,这样我们就可以试着解释学习者为什么用那种方法学习。

所有的教师都有自己的一套语言学习理论,这些理论按照有关语言学习者学习时使用一系列方法原则起作用。

但是,这些理论可能不是很明确,很多情况下,教师对于语言学生的观点会有所变化并且只包含他的行为中,例如,他可能开始决定给初学者学习现在时,这样做,他可能有意识的判定;在初级阶段,语法应该比诸如发现词汇等其他语言方面的知识先学,因为他认为这符合学习者的学习顺序,甚至他可能没有经过有意识的调查就这样认为。

先学现代时的决定还暗含很多东西,一个是学生应该先学习动词而不是名词或其他语言组成部分,另一个是学生在众多的动词时态中需要先学习现代时,教师可能意识到或没有意识到这些暗含的内容,他可能只是凭他永远也弄不清的直觉。

语言教学离不开语言学习理论,只不过这些学习理论常常是一系列隐含的信念。

本书通过考察语言学习者的语言积极产出语言的过程来帮助教师建立明确的语言学习理论。

这建立在一个假设的基础之上,即教师建立了明确的语言学习理论之后会做得更好。

这一假设也是需要证实的。

原理只有明确了以后才使用一种观点去考察、修正或代替它。

使用不明确的教学观念的教师不仅是非批判性的,而且其观点在不断的变化,二者必有其一,他们可能盲目的根据流行的语言教学最新时尚无规则的变换他们的教学理念,而教学中有明确原理观点的教师这可以批判地考察这些时尚教学原则。

本书认为,有明确语言学习理论的老师会做得更好,并且愿意修订自己的观念,而没有明确学习理论的教师可能忽视学习者真正做了什么,更多的关注语言学习过程的复杂性不能确保语言教学更有效,可以认为我们现在的知识还不能确保教学应用,但它会激起批判、挑战旧的原理并且可能会促使建立新的。

有意识的研究二语教学是为了改进教学。

不管是二语习得的学生,还是想对教学过程知道更多的教师,他们都需要发展自己的二语习得理论。

本书提供了理论建立基础所必要的背景知识,在第10章,我列出了一个框架和一系列假设来解释二语习得理论。

这本书得到了许多人的帮助,我特别要感谢助理亨利韦德森和基斯约翰,他们协助我写作和修订手稿,当然,书中的任何错误都由我承胆。

书中用“他”来代替“老师”和“学习者”,选择他们只是因为格式上方便,只是一个无标志的符号,如果有的读者不接受,我在这里表示道歉。

第一章二语习得的几个关键概念引言二语习得是一个复杂的过程,包含许多相关联的方面,这一章将考察对这一过程研究过程中提出的主要概念。

首先介绍什么是“二语习得”,然后讨论几个二语习得研究者经常使用的概念,最后,为本书以后章节讨论这些问题设立一个框架。

什么是二语习得?为了研究二语习得,弄清它的概念是非常重要的,为了读者能够弄清研究者对二语学习研究的立场,我们需要列出一系列的关键问题,下面的介绍的重点都集中在理解研究者是怎么考察二语习得的,他们是下面几章介绍的各种不同观点的基础。

二语习得作为一个统一的现象二语习得不是一个整齐划一可以预测的现象,学习者学习第二语言知识不只是采用同一种方法,二语习得是由学习者和学习环境两方面有关的多种因素而产生的,这两方面的各种因素互相影响导致了二语习得的复杂性和多样性,我们认识到这一点是很重要的,不同的学习者在不同的学习环境中采用不同的方法学习,不过,虽然要强调语言学习的差异性和独特性,但是只有二语习得可能具有相对稳定和概括性才会引起研究者的兴趣。

如果这种概括性不是对于所有学习者,至少应该是大多数,“二语习得”这一概念就是用来概括这些一致的方面,这本书同时考察习得过程不变的和具有明显灵活性的因素。

二语习得和第一语言习得二语习得是和第一语言习得相对的,他研究学习者在母语习得后怎么学习另一种语言,语言学习的研究开始于第一语言的习得研究,二语习得的方法论和探讨的许多主要议题都追随第一语言习得研究,所以一个关键的问题就体现了二语习得和第一语言习得过程相同或不同的程度,这不奇怪。

二语习得和外语习得二语习得和外语习得并不是相对的,二语习得用来表达概括化的概念既包括非教学(自然)习得,也包括教学(课堂)习得,不过,这两种不同情况下的习得采用的是相同还是不同的方法,这个问题还有待回答。

以句法和词法为中心二语习得涉及到语言学习者需要掌握的所有语言方面的内容,但是,关注的是学习者怎么掌握语法的次系统,比如否定句、疑问句,或者词素,如复数、定冠词、不定冠词。

研究者常会忽视其他语言水平单位的学习,如很少关于第二语言语音,几乎没有关于词汇的习得。

仅仅是最近,研究者才开始关注学习者是怎么获得语言交际能力的,也才开始考察学习者是怎样使用他们的知识表达意愿和情感的。

(实用的知识)所以,这本书所涉及的大部分是二语习得句法和词法方面的内容,必须承认这是一个缺陷,许多研究者现在承认不仅研究二语习得的其他方面比较重要(特别是参与对话能力的获得),而且语法习得的其他方面也很重要。

能力和表现在语言研究中能力和表现往往有很大区别,能力是由语言规则在脑中的图像组成,语言规则构成说话和听话者的内部语法。

表现由语言的理解和输出组成,语言习得研究——不管是第一还是第二语言习得——都对能力怎么发展感兴趣,不过,因为我们不能直接考察学习者内化的规则,我们必须考察学习者的表现,主要是输出,学习者的输出内容为我们考察内部规则提供了一个窗口,所以,就某种意义来说,二语习得研究就是关于输出的研究,它要看学习者实际说出的话,这些被看成是学习者脑子怎么想的证明,有一个主要的问题研究者必须搞清楚,即能力在多大程度上由输出推出。

习得和学习如果习得和学习是两个不同的过程,那么他们就是相对的概念。

“习得”一般指自然获得的,而“学习”一般指有意识的学习第二语言。

但是我认为这是否是一个真正的区别还值得探讨,所以我交替使用“习得”和“学习”而不管学习过程是有意识还是无意识,如果我想使用他们的具体意思,我会把字体变成斜体并做详细说明。

总之,“二语习得”就是在自然或教学中学习非母语的有意识或无意识的过程,它包括语音、词汇、语法和语用知识,但已经在很大程度上局限于形态句法了。

下面要介绍一些二语习得的关键问题第一语言的作用从战后开始到19世纪60年代,有一个强有力的理论认为学习第二语言的许多困难是由第一语言造成的,它认定第一语言和第二语言不同的地方,学习者第一语言的知识会干扰他们学习第二语言,而相同的地方则促进第二语言的学习,这一过程叫做“语言迁移”,第一语言和第二语言相同的部分对语言学习起积极作用,不同的部分起消极作用,人们(例如:1960布鲁斯和1964拉多)鼓励教师关注产生负迁移的困难部分,并鼓励他们用大量的练习来克服这些难点。

为了认定难点,从而产生了对比分析理论。

这一理论的思想基础是,找出学习者第一语言和第二语言的差别有可能预测某一二语学习者将遇到的困难。

最后出现了对两种语言的描写和语言间的比较研究。

很多不同于第一语言的第二语言特征被列出,认为这就是难点,在教学大纲中应该作为重点。

直到1960年代,实际的调查动摇了对比分析假设,学习者的错误都来自第一语言的影响吗?像杜蕾和波特(1973、1974)这样的研究者怀疑负迁移是否是二语习得过程中的主要因素。

有很大一部分语法错误(虽然有多大部分还是一个有争议的问题)不能用第一语言干扰来解释。

这种研究的结果是使第一语言的地位降低了,而对比分析也不再那么流行。

不过,早期的经验主义研究还剩有许多问题没有解决,特别是没有注意到L1不是通过迁移而是通过其他方式起作用的可能性。

迁移理论是和一个观点相联系的,这个观点认为语言学习就是通过练习和强化形成一系列的行为习惯,为了挑战这种语言学习观点,我们必须证明第一语言的旧习惯不会阻碍第二语言新习惯的学习,由此证明L2学习的错误不总是有干扰造成的,但是L1可能以完全不同的方式影响学习,例如,学习者并不把L1的规则迁移到学习中,而是避免使用L1没有的规则,或者可能L1和L2包含难点的不同部分受到语言学上的限制,因此迁移只有在特定的语言情况下才发生;或者学习者可能有意识的借用L1的知识来提高他们的成绩。

(也就是他们“翻译”)如果采用更认知的观点看待L1,那么这就是一个非常值得探讨的话题。

第二章我们会考察对比分析假设,还有因为学习者错误的研究致使它被人们抛弃。

第二和第八章介绍最近的研究,L1语言作为二语习得的一个积极的因素重新被人们肯定。

习得的自然顺序对比分析假设有有一个假设认为由于负迁移造成不同类型的难点,那么不同L1的学习者学习L2的方式也是不同的。