月经周期对女性知觉性侵犯遭遇的影响

辅导员心理助人培训考试题库(易班优课)

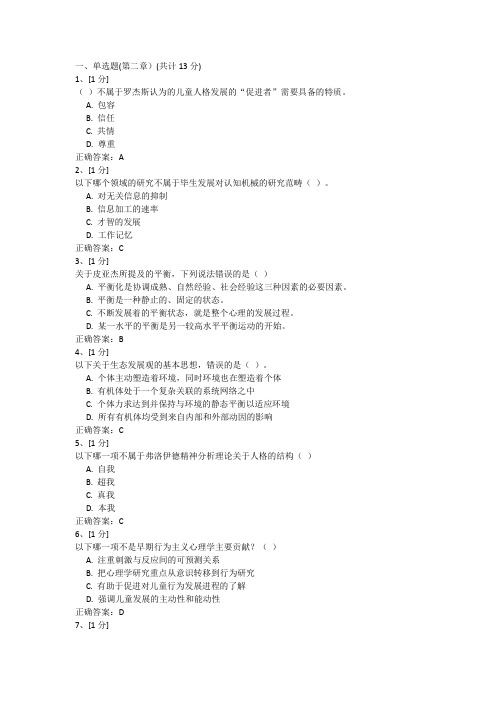

一、单选题(第二章)(共计13分)1、[1分]()不属于罗杰斯认为的儿童人格发展的“促进者”需要具备的特质。

A. 包容B. 信任C. 共情D. 尊重正确答案:A2、[1分]以下哪个领域的研究不属于毕生发展对认知机械的研究范畴()。

A. 对无关信息的抑制B. 信息加工的速率C. 才智的发展D. 工作记忆正确答案:C3、[1分]关于皮亚杰所提及的平衡,下列说法错误的是()A. 平衡化是协调成熟、自然经验、社会经验这三种因素的必要因素。

B. 平衡是一种静止的、固定的状态。

C. 不断发展着的平衡状态,就是整个心理的发展过程。

D. 某一水平的平衡是另一较高水平平衡运动的开始。

正确答案:B4、[1分]以下关于生态发展观的基本思想,错误的是()。

A. 个体主动塑造着环境,同时环境也在塑造着个体B. 有机体处于一个复杂关联的系统网络之中C. 个体力求达到并保持与环境的静态平衡以适应环境D. 所有有机体均受到来自内部和外部动因的影响正确答案:C5、[1分]以下哪一项不属于弗洛伊德精神分析理论关于人格的结构()A. 自我B. 超我C. 真我D. 本我正确答案:C6、[1分]以下哪一项不是早期行为主义心理学主要贡献?()A. 注重刺激与反应间的可预测关系B. 把心理学研究重点从意识转移到行为研究C. 有助于促进对儿童行为发展进程的了解D. 强调儿童发展的主动性和能动性正确答案:D7、[1分]格塞尔认为,成熟是一个(),决定着心理发展的方向和模式。

A. 重要因素B. 内部因素C. 自然过程D. 决定性因素正确答案:B8、[1分]下列哪一项不属于维果斯基所说的低级心理机能?()A. 情绪B. 感知觉C. 逻辑记忆D. 形象思维正确答案:C9、[1分]年幼儿童刚学会个位数加法,当遇到“2+5=?”这样的问题时,他们可以借助已有的个位数加法规则,得出“7”的结论,这个过程属于()A. 同化B. 图式(格式)C. 平衡D. 顺应正确答案:D10、[1分]1974年修订版的格塞尔行为发育诊断量表的各年龄测试内容不包括幼儿行为的()。

月经周期与性欲

大脑 中枢 ,有一 个 能 受精 的 卵子 形 成 , 从 而 让 大 脑 中枢 停 止 产 生 雌 激 素 。在 此 周 期 的 这 个 关 键 阶 段 ,女 性 在 肉 体 与 心 理 上 都 适 宜做 爱 ,或 适 宜 受 精 。她 等 待 着 她 爱 的 男 人 ,当她 找 不 到 或 他 不 向她 走 来 时 ,某 种 痛 苦 — — 有 意 识 或 潜 意 识 的 — — 就 会 出 现 ,而 她 表 现 出 来 的 易 怒 、神 经 紧 张 ,却 往 往 很 难 被 男 人 理 懈 。

排 卵 后 ,女 性 的 性 需 要 下 降 。女 性 的机 体 准 备 受 孕 ,这 种 准 备 由愿 望 或 由 害 怕 怀 孕 表 现 出 来 。在 女 性 的 整 个 月 经 周 期 中 ,这 是 她 性 需 要 最 低 的 时 候 。在 生理 或心 理 上 ,她 等待 着 受精 卵 子在 子

维普资讯

的 性 生 活 。 在 月 经 之 后 ,当ቤተ መጻሕፍቲ ባይዱ新 的 周 期 开 始 时 ,卵

子 在 卵 巢 内 成 熟 。这 个 周 期 的 第 一 阶 段 , 女 性 体 内 会 分 泌 出 越 来 越 多 的 雌 激 素 , 这 是 女 性 充 满 活 力 ,在 性 生 活 上 表 现 得 越 来 越 主 动 的 时 期 ,这 种 主 动 性 ,有 时 连 女 人 本 人 也 感 到 吃 惊 。许 多 女 人 说 ,在 这 个 阶 段 有 强 烈 的 性 欲 与 性 想 像 。

月经周期不同时相恐惧表情对时间知觉的影响

结论 :女性在排卵期相对 于其他 时相表现出高估时间 的倾 向 ;与体验 中性 情绪相 比 , 被试 体验恐惧 表情 的

时间知觉加长 。

【 关键词】 月经周期 ; 情绪 ;时间知觉;卵巢激素;描述性研究

中图分类号 :B 4 85。R 1. 1 文献标识码 :A 文章编 号 :10 6 2 (0 2 0 06 — 5 7 15 0 0— 79 2 1 )0 1— 0 1 0

l grs o s e u n i ft v l o h eW ih r a a o em dlt l h s ( , 7±0 0 )V. o p n ef e c so eo ua np a a h e n t t f — e ae【 0 5 n e r q e h i t s s g t h t i u ap h h .2 S

d i 1.9 9ji n 10 o: 0 36 /.s .0 0—62 .0 20 . 1 s 7 9 2 1. 10 4

( 中国心理卫生杂志 ,2 1 ,2 ( ) 1— 5 ) 0 2 6 1 :6 6 .

Efe t ff a f x e so n i e pe c pto n e sr lc ce f cs o e r ule pr s i n o tm r e i n i m n t ua y l

t e me s u l c c e M e h d : Eih y f e f mae g d o 9 — 2 y a s o d c mpe e e o a ie t n h n t a y l . t o s r g t ・ v e ls a e f 1 i 9 e r l o ltd a t mp r l b s c o i t s . e l n e p n e fe u n isf rf a f la d n u r a i x r s i n r o ae mo g t e e l o l — a k Th o g r s o s r q e ce o ru n e t f c a e p e s swe ec mp d a n a y f l c e l a l o r h r i u a , v lt n a d mi — ta h s s Re u t: e e wa i n f a tman e f c ft e me sr a h s s a d te lr o u a o d l e p ae . s l Th r s a sg i c n i fe t n t l p a e , i n u l s i o h u n h

月经周期对女性性欲的影响

案例三:月经周期对女性性欲影响的研究结果

总结词

研究表明,月经周期对女性性欲的影响存在个体差异 。

详细描述

尽管一些研究表明月经周期对女性性欲存在显著影响, 但也有研究指出个体差异很大。有些女性可能会在月经 周期的不同阶段保持稳定的性欲,而另一些女性则可能 会经历更明显的性欲波动。此外,一些外部因素,如个 人情绪状态、文化背景和社会环境等也会对女性的性欲 产生影响。因此,对于每个女性来说,理解自己的身体 和情感需求以及寻找适合自己的方法来提高性欲是重要 的。

06 月经周期对女性性欲影响的案例分析

案例一:月经周期对女性性欲的影响

总结词

月经周期对女性性欲存在显著影响,不同阶段的女性性欲水平存在差异。

详细描述

在月经周期的不同阶段,女性体内的荷尔蒙水平会有所变化,从而影响性欲。例如,在 排卵期前后,女性体内的雌激素水平较高,这可能导致性欲增强。而在月经期和月经前 期,由于荷尔蒙水平的变化和生理反应,一些女性可能会出现性欲减退或性欲不振的情

况。

案例二:如何提高月经周期中的性欲

总结词

通过调整生活方式和荷尔蒙水平,可以改善月经周期 中的性欲。

详细描述

为了提高月经周期中的性欲,女性可以采取一些措施。 首先,保持健康的生活方式,包括均衡的饮食、适度的 运动和良好的睡眠,有助于提高身体整体健康水平和荷 尔蒙平衡。其次,对于荷尔蒙水平失衡的女性,医生可 能会建议使用荷尔蒙疗法来调整雌激素和孕激素水平, 从而改善性欲。此外,一些女性可能会发现通过与伴侣 沟通情感、增加亲密接触和尝试新的性爱方式等方式来 提高性欲。

详细描述

月经周期是女性生殖系统的一个重要组成部分,它涉及到卵巢、子宫和激素等多 个方面的变化。在月经周期中,卵巢会释放卵子,子宫内膜会经历增厚、脱落和 修复的过程。

性健康知识:女性月经周期对性生活的影响

性健康知识:女性月经周期对性生活的影响女性月经周期对性生活的影响女性月经周期是生理周期的重要组成部分,它对女性性生活的影响不容忽视。

月经周期以卵巢分泌的雌激素和黄体素为主导,生理和心理因素也会影响女性的性欲。

因此,理解月经周期如何影响女性性生活可以帮助女性更好地了解自己的身体和性需求,提高性生活质量。

月经周期对性欲的影响月经周期对女性性欲的影响是复杂和多样的。

在月经前后的几天内,女性通常会有性欲上升的现象,这是由于雌激素水平升高和正常生理反应所致。

随着月经流血的开始,女性的性欲可能会下降,并在月经期间达到最低点。

经期和排卵期之间的日子,女性的性欲通常会迅速恢复。

因此,了解自己的月经周期对于预测和安排性生活的时机至关重要。

月经周期和身体感受在月经开始的前几天和月经期间,女性的身体可能会出现不适甚至疼痛,这可能会影响她们的性欲。

生理原因可能包括痛经、月经痛、腹胀、乳房肿痛、头痛、疲劳和情绪波动等。

然而,在月经后的几天内,女性的雌激素和黄体素水平开始回升,身体感受会逐渐变得更加舒适,女性的性欲也会逐渐恢复。

月经周期和性高潮经过调查,研究人员发现,受试者在不同的月经周期阶段中达到性高潮的频率是不同的。

调查结果显示女性在排卵期的性高潮次数最高,其次是月经前后和排卵期前。

这一结果也在很大程度上表明女性在性行为中选择的时间会受到月经周期的影响。

月经周期和避孕月经周期对避孕也有一定影响。

由于月经周期的变化,女性可能会出现排卵不规律的现象,这表明进行避孕需要更为慎重和确切的时间计算。

例如,如果不希望在月经期间那几天怀孕,建议女性在安全期内进行性行为,或者采用避孕方式如安全套、避孕药、避孕环等。

总结月经周期和女性身体的关系密切,对于女性的性需求和性健康至关重要。

为了更好地处理自己的性生活,女性应该了解自己的月经周期,避免在生理和身体感受最不适合性行为的时候进行。

合理的避孕方法也可以保护女性在性生活中的身体和心理健康。

女性生理周期对认知表现的影响

女性生理周期对认知表现的影响当谈论生理周期对女性身体健康的影响时,我们通常会涉及到生理症状、情绪变化等方面。

然而,相对较少的人注意到,女性的生理周期对认知表现也有一定的影响。

在本文中,我们将探讨女性生理周期在认知方面的作用,并进一步了解这种影响的原因。

1. 认知表现与生理周期的关系:研究表明,女性的生理周期和认知表现之间存在一定的关联。

在月经开始前的几天和经期中,女性可能会遇到一些认知方面的挑战,例如注意力不集中、记忆力下降、反应时间变慢等。

这种差异通常在排卵期后迅速消失。

此外,一些研究还发现,女性在生理周期不同阶段对不同类型的认知任务的表现也会有所不同。

2. 注意力与生理周期的关联:生理周期中的激素变化可能对女性的注意力产生影响。

在月经周期的前一周,女性更容易分散注意力,难以集中精力完成任务。

这可能是因为雌激素水平下降引起的。

另一方面,在排卵期后,女性的注意力会得到提高,可能与雌激素水平的回升有关。

3. 记忆力与生理周期的关联:记忆力是认知功能的重要组成部分,而生理周期的不同阶段可能会对女性的记忆产生影响。

一些研究表明,女性在月经开始前的几天和经期中会出现记忆能力下降的现象。

这可能与孕激素和雌激素水平的变化有关。

然而,在排卵期后,女性的记忆能力可能会恢复到更高水平。

4. 反应时间与生理周期的关联:反应时间是衡量认知功能的重要指标之一。

研究发现,女性在生理周期的不同阶段可能会表现出不同的反应时间。

在月经开始前的几天和经期中,女性的反应时间可能会增加,即反应速度变慢。

这可能与雌激素水平下降和孕激素水平增加相关。

在排卵期后,女性的反应时间可能会恢复到正常水平。

5. 影响的机制:生理周期对认知表现的影响是复杂的,其中涉及到激素、大脑结构和神经传递等方面。

激素变化在调节女性认知功能方面起着重要作用。

雌激素和孕激素在大脑中影响神经递质的水平,改变神经元的活动。

此外,不同生理周期阶段对认知任务的处理可能涉及到不同的神经网络。

女人每月身体欲望周期变化

第1-7天:月经期-你对外界反应过于敏感由于妊娠没有发生,在脑垂体激素的调控下,卵巢中雌激素和孕激素的分泌量下降,子宫内膜供血小动脉发生痉挛收缩,然后破裂,子宫内膜缺血、坏死和脱落,于是就表现为月经来潮,这个过程大约会持续2-8天……这个过程实际是生物体自身一种很精妙的调整,它使没有受孕的子宫内膜及时更新,不致因过度增殖而发生类似癌症那样的异常变化。

月经来潮时,由于卵巢激素水平下降,尿量较平日稍增,因此你觉得自己的身材特别苗条,体态优美。

同时,你的皮肤也在一天天变得细嫩起来。

医生特别提示:这几天,你会极易疲倦,容易伤风感冒。

根据近期一些调查显示,28%的女性在月经期内生病的可能性较平日更高,约有超过70%的女性感受到经痛之苦,伴随的症状还有胃痉挛和腹泻。

经历这个时期时,你身体的抗凝血系统处于被激活的状态,要注意保暖和休息,同进避开可能的出血情况,比如外科手术、献血……你当然也要错开妇科检查。

第8-11天:卵泡早期(行经之后)-你的身心都开始为夫妻生活做好了准备月经刚刚结束时,卵巢雌激素的产生会日益恢复。

而雌激素是刺激子宫内膜滋生的基础,它逐渐修复月经期剥脱了表层的内膜,并促使它重新增厚,使血管日益丰富和饱含血液。

如果在一个月中有一段时间你感状态良好,那么就是这个时候了,你不妨把挑战性的工作安排在这个时期来完成,那也许会给自己和他人带些惊喜。

更令人感到高兴的是,即使你没有足够多的睡眠,这几天你的皮肤仍能难以置信的红润、有光泽。

医生特别提示:雌激素虽然并不激发女人的性冲动,但它能使阴道湿润,富于弹性,并使生殖系统的血液循环向阴道,为阴道提供充分的血液量,为准备妊娠的夫妻生活做好了完满的准备。

这个时期是最适合进行全身体检的,包括妇科体检的宫颈抹片和乳房自检。

如果你需要做妇科的治疗或手术,比如阴道用药、宫颈光疗或电熨、输卵管通液等等,现在是最适宜的时间。

第12-14天:卵泡晚期(排卵之前)-愉快的心情全都写在你的脸上至此,你的雌激素水平逐渐达到高峰,卵泡随之逐渐发育成熟。

女性犯罪与月经周期

法医学杂志2000年8月第16卷第3期·181··学术讲座·女性犯罪与月经周期易旭夫1邓振华1廖志钢1万平2(1华西医科大学法医学系,四川成都610041;2成都青羊公安分局,四川610063)[中图分类号]DF795.3[文献标识码]B[文章编号]1004-5619(2000)03-0181-011历史回顾一个世纪前法庭在处理女性犯罪案例时,就开始考虑到女性犯罪当时是否处于月经期这个问题,女性偷窃因受月经期影响而作案可追溯到19世纪初期[1]。

1890年Icard报道56例女性偷窃中有35例处于月经期,四年以后Lombroso和Ferrero报道80例女性因妨碍公务而被捕,其中71例自称处于月经期,由此在法国法庭形成一个认识:女性行为举止的变化明显受其月经周期的影响,且应纳入法律定罪量刑范围内,因为女性在月经期犯罪,可能是因月经期的短暂精神障碍所致。

19世纪的法国精神病学家Esguiroi指出部分有兴奋症状的精神病人在月经期其症状更明显,包括情绪激动、思维奔逸、幻觉、错觉,甚至判断错误,他把月经期作为精神障碍的诱因之一。

2目前研究状况在法国,1945年Cooke[2]报道在巴黎发生的女性犯罪中,84%妇女处于月经期。

其他作者亦有类似报道,1961年Daiton[3]报道156例犯罪女性中,处于月经期犯罪占49%; 1980年d'rban[4]报道50例女性犯罪处于月经期占44%。

在以后的研究中作者在排卵期或排卵后期的女性犯罪未发现明显差异,他们的研究包括三个妇女谋杀她们的丈夫和三个妇女殴打她们的孩子。

1975年Daiton[5]对处于月经期妇女殴打孩子的案例进行一系列研究,报道尽管女性在月经期殴打孩子尚没有系统研究,但这种现象还是比较多,她也注意到这类妇女在非月经期间精神状态完全正常,甚至还有很强的母爱。

1991年Peter[6]报道一妇女每次月经期间殴打她的两个孩子,其中一个9个月的孩子因殴打等因素死亡,另一两岁的孩子被保护起来,当她最后去看她的孩子,发现孩子有体表损伤,回家后便上吊自杀,尸解发现她处于月经期。

性别器官的生理周期是否会影响性欲和性行为?

性别器官的生理周期是否会影响性欲和性行为?性欲和性行为是人类生理和心理的重要组成部分,而性别器官的生理周期是否会影响性欲和性行为一直是一个备受关注的话题。

而对于男性和女性,他们的性别器官并不只是生殖器官,还有其他的生理周期与之相关。

下面将从月经周期、精子生成周期和激素波动周期三个方面来探讨性别器官的生理周期如何影响性欲和性行为。

一、月经周期月经周期是女性生殖系统的重要生理周期,从月经开始到下次月经来临的时间间隔约为28天,但也会有个人差异。

月经周期里,女性体内的雌激素和孕激素水平会有相应的波动,这种波动可能会对女性的性欲和性行为产生影响。

1. 在月经开始时,雌激素和孕激素的水平较低,可能会导致性欲下降。

这是因为激素水平的变化会影响女性的情绪和体力状况,从而减少对性的欲望。

2. 当月经结束后的第二周,女性体内的雌激素和孕激素逐渐升高,性欲也会相应增强。

这个时期的女性通常会感觉到更强烈的性欲和对性的兴趣。

3. 在月经周期的第三周,激素水平开始下降,女性的性欲也会相应降低。

这个时期的女性可能对性的兴趣减弱,甚至出现性欲低下的情况。

二、精子生成周期对于男性来说,性欲和性行为通常与精子的生成周期有关。

精子的生成周期约为2-3个月,这个周期内男性体内的睾丸会不断产生新的精子。

在精子生成周期内,男性的性欲会有一定的变化。

1. 在精子生成周期的开始阶段,新产生的精子较少。

这个时期的男性可能会感到性欲相对较低,甚至接近饱和状态。

2. 随着精子生成周期的进行,新产生的精子数量逐渐增多。

这个阶段男性的性欲也会随之增加,对性的欲望会逐渐增强。

3. 在精子生成周期接近尾声时,新产生的精子已经达到最高峰。

此时,男性的性欲也会达到巅峰状态,对性的渴望会达到高峰。

三、激素波动周期除了月经周期和精子生成周期外,激素波动周期也会对性欲和性行为产生影响。

男性和女性体内的激素水平会有一定的周期性变化,这些变化可能会对性欲和性行为产生影响。

教你从月经看女性性欲变化

教你从月经看女性性欲变化

*导读:有的调查表明,假使性成熟的女性次性交是主动的话,那么多数发生在排卵期前后。

今天的女性个体就没有固定的发情期,倘若条件允许的话,她可在她喜欢的……

有的调查表明,假使性成熟的女性次性交是主动的话,那么多数发生在排卵期前后。

今天的女性个体就没有固定的发情期,倘若条件允许的话,她可在她喜欢的任何时间、任何地点与男性伴侣进行性亲昵。

据人类专家的研究,作为人类祖先的雌性类人猿也是有固定发情期的,即在每月一次的月经周期的中间阶段,它们都会进入发情期并有性行为。

但在人类漫长的进化过程中,由于生存竞争不断进步的结果,使那些没有固定发情期,随时随地都能交媾的雌体个体得以繁衍保留下来,而有固定发情期的雌性个体被淘汰。

第1 页。

辅导员心理助人培训考试题库(易班优课)

一、单选题(第二章)(共计13分)1、[1分]()不属于罗杰斯认为的儿童人格发展的“促进者”需要具备的特质。

A. 包容B. 信任C. 共情D. 尊重正确答案:A2、[1分]以下哪个领域的研究不属于毕生发展对认知机械的研究范畴()。

A. 对无关信息的抑制B. 信息加工的速率C. 才智的发展D. 工作记忆正确答案:C3、[1分]关于皮亚杰所提及的平衡,下列说法错误的是()A. 平衡化是协调成熟、自然经验、社会经验这三种因素的必要因素。

B. 平衡是一种静止的、固定的状态。

C. 不断发展着的平衡状态,就是整个心理的发展过程。

D. 某一水平的平衡是另一较高水平平衡运动的开始。

正确答案:B4、[1分]以下关于生态发展观的基本思想,错误的是()。

A. 个体主动塑造着环境,同时环境也在塑造着个体B. 有机体处于一个复杂关联的系统网络之中C. 个体力求达到并保持与环境的静态平衡以适应环境D. 所有有机体均受到来自内部和外部动因的影响正确答案:C5、[1分]以下哪一项不属于弗洛伊德精神分析理论关于人格的结构()A. 自我B. 超我C. 真我D. 本我正确答案:C6、[1分]以下哪一项不是早期行为主义心理学主要贡献?()A. 注重刺激与反应间的可预测关系B. 把心理学研究重点从意识转移到行为研究C. 有助于促进对儿童行为发展进程的了解D. 强调儿童发展的主动性和能动性正确答案:D7、[1分]格塞尔认为,成熟是一个(),决定着心理发展的方向和模式。

A. 重要因素B. 内部因素C. 自然过程D. 决定性因素正确答案:B8、[1分]下列哪一项不属于维果斯基所说的低级心理机能?()A. 情绪B. 感知觉C. 逻辑记忆D. 形象思维正确答案:C9、[1分]年幼儿童刚学会个位数加法,当遇到“2+5=?”这样的问题时,他们可以借助已有的个位数加法规则,得出“7”的结论,这个过程属于()A. 同化B. 图式(格式)C. 平衡D. 顺应正确答案:D10、[1分]1974年修订版的格塞尔行为发育诊断量表的各年龄测试内容不包括幼儿行为的()。

女性月经周期变化对神经系统反应时空特征影响分析

女性月经周期变化对神经系统反应时空特征影响分析女性的生理周期包括月经周期和生殖周期两个部分,在这些周期内,女性的身体会经历一系列生理变化。

月经周期是指从月经第一天到下次月经第一天的时间段,通常为28天左右。

在月经周期中,女性的体内激素水平、性荷尔蒙的分泌以及相关生理和心理过程会发生变化。

这些变化不仅会对女性身体产生影响,还可以对神经系统的反应时空特征产生一定的影响。

首先,女性月经周期变化可能会对神经系统的情绪反应产生影响。

在月经周期的不同阶段,女性的情绪状态可能会有所变化。

在月经前一周,女性常常会出现情绪低落、易怒、焦虑等不良情绪。

这与女性体内激素水平的变化密切相关。

在月经前,女性体内的雌激素和孕激素水平下降,这可能会导致神经系统中与情绪调节有关的神经递质的不平衡。

因此,女性月经周期变化对神经系统的情绪反应可能会导致情绪波动较大的特征。

其次,女性月经周期变化还可能对神经系统的认知功能产生影响。

研究发现,在月经前后,女性的认知功能可能会发生变化。

在月经前一周,女性可能会出现注意力不集中、记忆力减退等认知功能下降的表现。

这一现象被称为“月经大脑”。

这种变化可能与女性体内激素水平的变化以及相关的神经递质的影响有关。

在月经前,女性体内的雌激素和孕激素水平下降,这可能会对神经系统中与认知功能有关的神经递质的平衡产生影响,进而导致认知功能下降。

因此,女性月经周期变化对神经系统的认知功能可能会表现出时间和空间特征的变化。

此外,女性月经周期变化可能还会对神经系统的疼痛感知产生影响。

在月经周期的不同阶段,女性可能会出现不同程度的疼痛感。

在月经来临前一周,女性可能会出现乳房胀痛、头痛等症状。

在月经期间,女性可能会出现腹痛、痛经等不适感。

这些疼痛感知的变化可能与女性体内激素水平的波动、子宫收缩引起的血液循环变化等因素有关。

这些变化会对神经系统的疼痛感知通路产生影响,从而影响疼痛的时空特征。

最后,女性月经周期变化还可能对神经系统的睡眠质量产生影响。

女性经期对认知和情绪的影响

女性经期对认知和情绪的影响女性生理周期中的一个重要阶段是经期,也就是月经期。

月经周期的不同阶段伴随着荷尔蒙水平的波动,这对女性的认知和情绪状态产生了影响。

本文将探讨女性经期对认知和情绪的影响,并介绍可能的原因和应对方法。

经期对认知的影响研究表明,女性在经期的不同阶段在认知上会有一些差异。

在月经开始前的几天,一些女性可能会经历注意力不集中、记忆力下降以及决策能力减弱等问题。

这可能影响她们的日常工作和学习效率。

这些认知问题的原因可以追溯到激素水平的波动。

在月经开始前,雌激素和孕激素水平下降,这可能对大脑的神经传导和血液流动产生影响。

这些生理变化可能引起神经元的不稳定和大脑区域之间的交流问题,从而影响认知功能。

此外,在经期的某些阶段,许多女性还可能面临情绪上的挑战。

经期对情绪的影响在经期开始前的几天,一些女性可能会出现情绪波动、易怒、焦虑和抑郁等问题。

这种情绪不稳定可能会对她们的日常生活产生负面影响,甚至导致人际关系的紧张。

类似于认知问题,经期的情绪波动可以归因于激素水平的变化。

雌激素和孕激素在经期的不同阶段波动,这可能对神经递质的平衡和神经系统的稳定产生影响。

这可能导致女性在经期期间更容易出现焦虑、抑郁等情绪问题。

应对女性经期的策略虽然女性经期对认知和情绪有一定的影响,但幸运的是,有一些策略可以帮助女性缓解这些问题。

1. 多休息:优质的睡眠对身体和大脑的恢复非常重要。

在经期期间,女性可以尽量保持良好的睡眠习惯,并在需要时尽量多休息。

2. 锻炼:适度的身体活动可以促进血液循环和荷尔蒙的平衡。

女性可以选择适合自己的锻炼方式,例如瑜伽、散步或慢跑等。

3. 饮食注意:均衡营养的饮食对于女性健康至关重要。

在经期期间,女性可以适当增加蛋白质和纤维素的摄入,同时减少咖啡因和糖的摄取。

4. 放松和应对技巧:女性可以尝试一些放松和应对技巧,例如深呼吸、冥想和倾听音乐等。

这些技巧可以帮助缓解焦虑和抑郁情绪,提高精神状态。

女性生理周期对认知功能的影响

女性生理周期对认知功能的影响女性的生理周期是指月经周期,它在女性生理健康中发挥着重要的作用。

除了影响生殖系统的功能外,生理周期还与认知功能密切相关。

本文将探讨女性生理周期对认知功能的影响。

第一部分:生理周期的基本知识生理周期是女性生殖系统的一个重要指标。

一般而言,生理周期的平均长度为28天,但每个女性的周期长度可能会有所不同。

生理周期主要由两个阶段组成:排卵前期和排卵期。

第二部分:生理周期对认知功能的影响2.1 排卵前期在生理周期的排卵前期,即月经结束后的第1到第14天,女性体内的雌激素水平逐渐升高。

研究发现,雌激素与认知功能之间存在着密切的关联。

雌激素对大脑中的神经递质、突触传递和神经保护等方面起到重要作用,从而对认知功能产生影响。

在排卵前期,女性的注意力、记忆力和语言表达能力通常较为敏锐和精准。

2.2 排卵期生理周期的排卵期通常发生在第14天左右,此时卵子从卵巢释放出来,进入输卵管待受精。

在排卵期,女性体内的雌激素和孕激素水平达到高峰。

研究表明,此时女性的认知功能表现出一种“高峰效应”。

女性在排卵期的注意力、学习能力和创造力等方面表现出较好的状态。

这可能与雌激素和孕激素对大脑中的神经递质、突触传递以及大脑区域的激活有关。

第三部分:认知功能在生理周期不同阶段的变化3.1 注意力认知功能中的注意力是指人对外界信息的选择性关注。

研究发现,在生理周期的不同阶段,女性的注意力会有所变化。

在排卵前期和排卵期,女性的注意力往往更加集中和敏锐,能够更好地处理复杂的认知任务。

3.2 记忆力记忆力是认知功能中的一个重要组成部分。

研究显示,女性在生理周期不同时期的记忆能力也会出现一定的差异。

在月经周期的排卵期,女性的记忆力通常较好,尤其对于情感色彩鲜明的信息更容易记忆。

3.3 语言表达能力语言表达能力是指人用语言进行思维表达和交流的能力。

生理周期的雌激素水平变化可能会影响女性的语言能力。

在生理周期的排卵前期和排卵期,女性的语言表达能力通常更加流畅和准确。

不同女性月经周期对大脑皮层影响的研究探讨

不同女性月经周期对大脑皮层影响的研究探讨近年来,越来越多的研究探讨了女性的月经周期对大脑皮层的影响。

不同的月经周期阶段对于女性的行为、注意力、情绪等方面都有着不同的影响。

在月经周期的不同阶段,女性体内荷尔蒙的水平始终在变化。

这些荷尔蒙的变化将影响大脑皮层活动的强度和区域的活动情况。

现在,让我们来看看月经周期的具体不同阶段对于大脑皮层的影响。

月经初期当女性月经开始时,内膜组织崩解并流出。

在此期间,生殖器官、神经系统和大脑皮层都遭受了一定程度的影响。

许多女性在这段时间里会感到疲惫、焦虑或失眠,这些情况可能与大脑皮质区域的活动有关。

此时,我们可以通过fMRI技术将大脑皮层的活动情况可视化。

研究发现,当荷尔蒙水平下降时,大脑皮层前额叶区域的活动情况也会下降。

这个区域与规划和决策等高阶认知功能相关。

此外,月经初期还会影响女性的记忆力。

月经中期在月经中期,女性卵巢会开始释放一定量的荷尔蒙。

研究表明,此时女性情绪稳定,精神状态较好。

同时,大脑皮层的活动情况也相对较高。

具体来说,中央相关皮质区域、额叶、颞叶等区域的活动都较为强烈。

这些区域与注意力和认知过程相关。

月经后期在月经后期,女性荷尔蒙水平达到了高峰。

同时,当女性身体接近排卵时,她们的行为和神经状态可能会因为较高的荷尔蒙水平而受到一定程度的影响。

在这时期,部分女性也容易出现心情波动或焦虑等情况。

当荷尔蒙水平达到顶峰时,大脑皮层的中央相关皮质区域和额叶区域活动强度增加,这些区域与注意力和情绪调节功能相关。

同时,颞叶更加活跃。

颞叶与记忆功能、情感记忆、情绪等方面密切相关。

研究还表明,月经周期后期,女性在面对社交情况时的表现反应更加强烈,这与大脑皮层的活动水平有关。

在与朋友和亲戚交往时,女性的大脑皮层的情感处理区域、情感记忆区域和颞叶皮质逐渐升温,表现得更加敏感。

这也是为什么部分女性在这个时期变得更加善于言辞,更易于抓住情感和心理需求。

结论通过研究不同女性月经周期对大脑皮层的影响,我们发现了这些周期的不同阶段对于大脑皮层的活动有着不同的影响。

女性生理周期对大脑结构的影响

女性生理周期对大脑结构的影响女性生理周期是指女性经历的月经周期和相关生理变化,这一周期通常持续28天左右。

在这个周期中,女性身体会经历排卵、受精、卵巢激素水平的波动等一系列变化。

除了对生育功能的影响之外,女性生理周期还对大脑结构产生一定的影响。

本文将探讨女性生理周期对大脑结构的影响,并解释其中的相关机制。

1. 月经期对大脑结构的影响女性经历的生理周期中,月经期是最为显著的一个阶段。

在月经期,女性身体会出现大幅度的激素变化,特别是雌激素和孕激素的水平降低。

这种变化会对大脑结构产生一定的影响。

研究表明,月经期的大脑结构变化主要表现在视觉和感知处理方面。

具体而言,月经期女性的大脑皮层厚度、灰质质量等方面可能发生变化。

这些变化可能导致女性在某些认知任务上的表现与其他阶段不同,比如注意力和工作记忆等方面。

2. 卵泡期对大脑结构的影响卵泡期是指女性生理周期的排卵前一段时间。

在这个阶段,雌激素和孕激素的水平不断上升,预示着激素的高峰即将到来。

这种激素变化可能对大脑结构产生一系列影响。

研究发现,卵泡期的大脑结构变化主要表现在记忆和情绪处理方面。

具体而言,卵泡期女性的大脑灰质量可能增加,与记忆和情绪相关的脑区可能活跃度增加。

这些变化可能使女性在这个阶段更容易记忆和处理情绪。

3. 黄体期对大脑结构的影响黄体期是指女性生理周期的排卵后一段时间。

在这个阶段,黄体开始分泌孕激素,维持子宫内膜的稳定,为受精卵的着床做准备。

这种激素变化也会对大脑结构产生一定的影响。

研究表明,黄体期的大脑结构变化可能与注意力和情绪调节有关。

具体而言,黄体期女性的大脑皮层厚度和灰质量可能呈现不同程度的变化。

这些变化可能与女性在这个阶段的注意力和情绪调节能力相关。

4. 生理周期对大脑结构的影响机制虽然女性生理周期对大脑结构产生一定的影响,但具体的影响机制尚不完全清楚。

目前,主要有以下几种解释。

首先,激素的波动被认为是影响大脑结构的重要因素。

雌激素和孕激素的水平变化可能导致大脑神经递质的调节不同,进而引发与大脑结构相关的变化。

女性生理周期健康危害分析与注意事项

女性生理周期健康危害分析与预防事项女性生理周期是指女性每月的月经期和排卵期的循环周期。

在这一时期,女性的身体和心理都会发生一系列的变化,有些变化可能会对健康产生不良影响。

因此,了解并预防这些危害对于维护女性健康至关重要。

一、生理周期阶段与健康危害1. 月经期(月经来潮前一周到月经来潮):这一时期,女性可能会出现情绪波动、头痛、乳房胀痛、水肿等现象。

同时,由于子宫内膜脱落,子宫颈口略微张开,容易受到细菌感染,引发妇科炎症。

2. 排卵期(月经来潮后至排卵):这一时期,女性体内激素水平发生变化,可能导致情绪不稳定、疲劳、头痛等症状。

同时,排卵期女性身体抵抗力下降,容易感染细菌或病毒。

二、生理周期的健康危害分析1. 妇科炎症:月经来潮时,子宫颈口略微张开,容易导致细菌感染,引发妇科炎症。

因此,在月经期需要注意个人卫生,避免性生活,以免引起感染。

2. 情绪波动:女性在生理周期中可能出现情绪波动现象,这是由于激素水平变化所致。

情绪波动可能会影响到工作和生活,因此,在这一时期需要注意调节情绪,保持心情舒畅。

3. 水肿:在生理周期中,部分女性可能会出现水肿现象,这是由于体内水分和钠离子代谢紊乱所致。

水肿可能会影响到日常生活和工作,因此需要合理安排饮食,避免摄入过多的盐分。

三、预防事项1. 保持良好的个人卫生习惯:在月经来潮前一周和月经期间,需要注意个人卫生,勤换内裤和卫生巾,避免细菌感染。

2. 合理安排饮食:在生理周期中,需要注意饮食的合理搭配,摄入足够的营养物质,避免摄入过多的盐分和辛辣食物。

同时,多喝水有助于排出体内多余的水分。

3. 保持心情舒畅:在生理周期中,可以通过听音乐、阅读、与朋友交流等方式来调节情绪,保持心情舒畅。

4. 定期进行妇科检查:定期进行妇科检查可以及时发现并治疗妇科疾病,维护女性健康。

5. 适当运动:适当的运动有助于增强身体抵抗力,预防感染和疾病。

在生理周期中,可以选择一些轻松的运动方式,如散步、瑜伽等。

月经周期与女性性兴奋

月经周期与女性性兴奋有实验显示:女性排卵期和经期相比,排卵期的大脑兴奋和经期的大脑兴奋程度相比有显著的差异,且经期大脑兴奋要强于排卵期;排卵期和其它期相比,排卵期的大脑兴奋和其它期的大脑兴奋程度相比有显著的差异,且其它期大脑兴奋要强于排卵期;我们发现在女性排卵期时与性唤起相关的脑区,在接受同样的视觉性刺激时兴奋程度不如月经周期其它时期;而在包括月经期在内的周期其它时期之间则无显著差异。

或者说,女性在排卵期最不容易被性唤起。

另外,月经期并不影响大脑对于性刺激的处理。

月经期并不影响大脑对于性刺激的处理是比较容易解释的。

以周期性的子宫内膜脱落为标志的月经现象主要见于高等灵长目动物,大部分动物的排卵周期中并没有这一过程,因此,应该是在进化史上较晚出现的生理现象。

周期性的子宫内膜脱落有利于清扫残存于子宫中的精子,有利于进行更有效的性选择。

但是这一生理现象对于生殖本身并没有非常显著的影响,因此,其并不偶联于与性有关的神经活动是容易理解的。

而与性刺激处理相关的神经活动在排卵期下调的结果显然需要深入的讨论。

按经典的达尔文式的自然选择理论,在没有外界环境限制时,物种会按照几何级数增长,而资源则按照算术级数增长,从而只有合适的个体能够生存下来;足够高的生育率是生物物种适应性进化的关键。

从这个视角看,女性似乎在排卵期应该更有接纳力,因为只有在排卵期附近的性交才会引起怀孕,从而提高生育率。

我们对此实验结果的看法是,女性在高受孕率的排卵期,是“有意的”下调对于性刺激的敏感性的,目的是减低此窗口的受孕率。

我们所说到的女性是“有意的”,并不是说女性个体通过深思熟虑之后得到的结果,而是一种由于长期的性选择而固化在我们心理结构中的本能。

这些本能是有适应性意义的。

月经周期对女性与性兴奋相关神经活动的调控

月经周期对女性与性兴奋相关神经活动的调控朱洵;高嵩;胡佩诚【期刊名称】《中国性科学》【年(卷),期】2010(019)009【摘要】与男性不同,女性有一系列与月经周期相偶联的生理-心理行为的变化.已经知道,在生理上月经周期是体内一系列激素水平周期性变化的表现,但是,月经周期在性心理层次上的影响尚未得到充分的阐明.本文通过功能核磁共振成像的方法,研究了健康女性在月经周期内受视觉性刺激时有关脑区活动性的变化.通过比较被试在月经期、排卵期以及月经周期其它时期接受视觉性刺激时大脑的活动差异.作者发现,在女性排卵期时,与性唤起相关的脑区在接受同样的视觉性刺激时其兴奋程度不如月经周期其它时期;而在包括月经期在内的周期其它时期之间则无显著差异.或者说,女性在排卵期最不容易被性唤起;另外,月经期并不影响大脑对于性刺激的处理.本文在人类不是纯粹对偶结合的性策略的观点基础上对本实验结果给出了一个初步的解释.【总页数】7页(P32-37,42)【作者】朱洵;高嵩;胡佩诚【作者单位】北京大学医学部心理学教研室,北京,100191;北京大学医学部心理学教研室,北京,100191;北京大学医学部心理学教研室,北京,100191【正文语种】中文【相关文献】1.“女性月经周期黄体生成素变化”的探究活动 [J], 钟廷;赵冉冉;王钰钦;张文华2.女性运动员血浆中神经肽Y浓度与月经周期 [J],Coiro;V;Chiodera;P.;Melani;A.3.深圳市育龄女性体重指数与月经周期异常的相关性研究 [J], 杨娟; 马旭; 代巧云; 张东梅; 关婷; 胡序怀; 林薇薇; 杨雪莹; 葛珊杉; 赵君4.月经周期对女性睡眠—觉醒和静息—活动的影响 [J], 刘红艳;包爱民;周江宁;刘荣玉5.神经质程度和月经周期对女性主观情绪和生理反应的影响 [J], 吴梦莹;周仁来;黄雅梅;王庆国;赵燕;刘雁峰因版权原因,仅展示原文概要,查看原文内容请购买。

月经周期的实验感想

实验感想

在生物体系统中,生理节律活动是一种普遍的现象。

这种生理节律对人的行为的影响正在不断地广泛地为人们所认识。

在过去十年里,对月经周期节律的实验研究证实了一些生理变化与行为之间的相互关系。

这些行为包括基本的感知觉过程,认知及社会性行为。

对在感觉机能中的月经周期节律变化的研究涉及到视觉、嗅觉、听觉、味觉和触觉。

本文旨在于综合对这五种感觉机能中月经周期变化的研究,以证明发生在感觉机能中月经周期变化的程度。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

心 理 学 报 2007,39(3):536~540Acta Psychologica SinicaWomen’s Perceptions of Men’s Sexual CoercivenessChange Across the Menstrual CycleChristine E. Garver-Apgar1, Steven W. Gangestad1, and Jeffry A. Simpson21University of New Mexico 2Texas A&M UniversityAncestral women would have suffered higher costs if they were raped or sexually coerced during the fertile phase of their reproductive cycle. Accordingly, selection pressures should have made women more sensitive to cues of male sexual coerciveness near ovulation. Normally ovulating women watched videotaped interviews of men trying to attract another woman and then rated each man’s probable sexual coerciveness. Women nearing ovulation rated men as more coercive relative to women in the non-fertile phase. Moreover, fertile women’s judgments of men’s coerciveness were better predicted by an aggregate of women’s responses than were judgments of non-fertile women, suggesting that women are more attuned to salient cues of potential coerciveness during the fertile phase of the cycle, and thus, may be less error-prone. Because these findings are unlikely to be explained by general-purpose learning mechanisms, they suggest that women may possess specially designed perceptual counter-strategies that guard against male sexual coercion.Keywords: sexual coerciveness, ovulation, non-fertile phase.月经周期对女性知觉性侵犯遭遇的影响女性在排卵期遭遇强奸或其它形式的性侵犯可能会受到较大伤害。

进化历史中女性遭遇性侵犯的危险不断重现使现代社会女性在排卵期对男性性侵犯的线索较为敏感。

本研究旨在探讨女性被试观看男性试图吸引其它女性的录像后如何评价每位男性性侵犯的可能性。

研究发现接近排卵期的女性比不处于排卵期的女性更可能认为男性会进行性侵犯。

这些发现显示,女性具有特定的知觉进化机制来警惕性侵犯,这种特定的进化机制可能受到月经变化的调节。

关键词:性侵犯,排卵期,非生育期。

分类号:B84-069The evolutionary perspective suggests that some psychological processes should have been shaped by natural selection because they benefited ancestral individuals in very specific ways. One goal of evolutionary psychology is to identify these features—psychological adaptations—within the larger network of psychological processes (including byproducts, features not directly shaped to perform specific functions). Documenting adaptation is a difficult and “onerous” process (Williams, 1966), one that involves showing that a feature exhibits “special design” for performing a specific function not explainable by an account other than selection for that function (Andrews, Gangestad, & Matthews, 2002; Thornhill, 1990, 1997).Evolutionary scientists have begun to document the specific design features of various social judgments and perceptions, including social contract algorithms (e.g., Fiddick, Cosmides, & Tooby, 2000; Cosmides & Tooby, 1992; but see Sperber & Girotto, 2002), Received 2006-12-30Correspondence should be addressed to Christine Garver-Apgar, Department of Psychology, University of New Mexico, Logan Hall, Albuquerque, NM 87131, USA, ; e-mail: garver@.adaptive biases that avert costly errors (e.g., Haselton & Buss, 2000; Haselton, Nettle, & Andrews, 2005; Haselton & Nettle, 2006), social categorization (e.g., Kurzban, Cosmides, & Tooby, 2001; Cosmides, Tooby, & Kurzban, 2003), prejudice and stereotyping (e.g., Schaller, Conway, & Tanchuk, 2002; Park, Faulkner, & Schaller, 2003), and trait inferences based on specific facial features (e.g., Zebrowitz, Hall, Murphy, & Rhodes, 2002). Ingenious methods have been developed to demonstrate the design properties of these social judgment adaptations.To demonstrate the existence of an adaptation, one must show that a feature’s fit with and “solution” to an evolutionary-relevant problem would not likely have been shaped ontogenetically through general-purpose learning processes (see Andrews et al., 2002). One strategy is to link psychological features with underlying physiological processes that are unlikely to be shaped or controlled by general-learning processes. For example, when women are fertile (on days just prior to ovulation), they are more attracted to the scent of symmetrical men (i.e., men more likely to possess “good genes”; Gangestad & Thornhill, 1998; Rikowski & Grammer, 1999; Thornhill & Gangestad, 1999; Thornhill, Gangestad, Miller,3期 Christine E. Garver-Apgar, et al. Women’s Perceptions of Men’s Sexual Coerciveness Change Across the Menstrual Cycle 537Scheyd, McCollough, & Franklin, 2003), to the scent of dominant men (Havlicek, Roberts, & Flegr, 2005), to men who display greater social presence and intrasexual competitiveness (Gangestad, Simpson, Cousins, Garver-Apgar, & Christensen, 2004), to men with deep (more masculine) voices (Feinberg, Jones, Law-Smith, Moore, DeBruine, Cornwell, Hiller, & Perrett, 2006; Puts, 2005), and to masculine faces (Johnston, Hagel, Franklin, Fink, & Grammer, 2001; Penton-Voak & Perrett, 2000; Penton-Voak, Perrett, Castles, Burt, Koyabashi, & Murray, 1999). Women in the fertile phase also report greater sexual attraction to men other than their primary partners (Gangestad, Thornhill, & Garver, 2002; Gangestad, Thornhill, & Garver-Apgar, 2005). All of these effects are derived from the hypothesis that selection shaped women to seek potential genetic benefits through mating more so when fertile than when non-fertile (Gangestad & Thornhill, 1998, 2003; see also review in this issue, Garver-Apgar, Gangestad, & Thornhill, 2006). Because these patterned, context-specific shifts do not appear to be explained by general-purpose learning processes, they may be specially-designed female adaptations for mate choice.To our knowledge, no research has documented adaptive changes in particular social judgment processes across the female menstrual cycle. The current study was designed to examine women’s perceptions of men’s sexual coerciveness across the cycle. From an evolutionary perspective,women should be sensitive to cues of male sexual coerciveness and typically avoid men who are perceived to be sexually coercive (Thornhill & Palmer, 2000)*. Ancestrally, however, women would have suffered more negative consequences if they were sexually victimized when fertile, given the increased risk of conceiving the offspring of a non-investing and potentially low fitness male. (See Chavanne & Gallup, 1998; Petralia & Gallup, 2002; and Bröder and Hohmann, 2003, for demonstrations of counter-strategies based on this reasoning.) Selection, therefore, may have shaped women’s perception of men’s sexual coerciveness to vary across the reproductive cycle in two distinct ways. First, when near ovulation, women might err on the side of caution when assessing men’s potential sexual coerciveness. According to Error Management Theory (Haselton & Buss, 2000), when the costs of being sexually victimized are highest, women should shift their perceptions to decrease false negative errors at the expense of making more false positive errors. Thus, we predicted that women perceive men as more sexually coercive at fertile points of their cycle than at non-fertile points.* If one assumes rape was a costly event for ancestral women, one would expect selection to have endowed women with counter-strategies to rape regardless of whether men possess rape-specific adaptations.Second, when women are fertile, they should be more accurate at detecting men who might use sexually coercive tactics. This hypothesis is very difficult to test directly because accurate information about men’s past coercive behavior is difficult to obtain and, even if available, could be a fallible indicator of men’s general coercive tendencies. Thus, indirect methods must be used to assess women’s accuracy at detecting sexually coercive men. In the present study, we assumed that: (1) women use at least some valid cues associated with potential male sexual coerciveness when judging a particular man’s likelihood of being coercive; (2) the coercive judgments made by each woman contains some perceiver-specific error; and, therefore, (3) the average women’s judgment of a particular man’s coerciveness is more accurate than the ratings of a particular man made by most individual women. Hence, we predicted that the average women’s rating of men’s sexual coerciveness (i.e., the ratings averaged across the full sample of women) predict women’s individual ratings of these men’s sexual coerciveness better for fertile women than for non-fertile women.MethodWomen from the University of New Mexico viewed videotaped interviews of men being interviewed for a possible date and rated each man’s likely sexual coerciveness, given his verbal and nonverbal behavior during the interview. Specifically, 76 men were recruited from introductory psychology classes at Texas A&M University to participate in a study on “Relationship Formation.” Each man was interviewed over a video-camera system by one of two attractive female undergraduates for a potential lunch date. Men first answered general questions posed by the female interviewer, after which another man (actually an experimental accomplice) described as a “competitor for the lunch date” appeared on each participant’s monitor. Each man was then instructed to tell the “competitor” why the female interviewer should choose him for the date over the competitor. Unbeknownst to participants, the interviewer’s questions had actually been scripted and pre-recorded on videotape. Following the interview, each participant was debriefed and permission to use his videotaped interview for future research was obtained (see Simpson, Gangestad, Christensen, and Leck [1999] for details).Normally ovulating women (those not using any form of hormonal contraception and pre-menopausal; N = 169) were recruited from introductory classes at the University of New Mexico to participate in a study on “Videotape Rating of Men’s Attractiveness” (mean age = 19.56; SD = 1.98). Women viewed one-minute segments of the videotaped interviews. They538心 理 学 报 39卷saw either the first segment of the tape when the men responded to the question, “Please tell me about yourself, including who you are, what you like to do, and what you don’t like to do” (N = 50 women), or the last segment when the men told the “competitor” why the interviewer should select them (N = 119 women). Each woman viewed approximately half of the interviews: either the first 40 men (N = 77 women) or the last 36 men (N = 92 women).Women rated each man on several characteristics, six of which are pertinent to the present study. Three items measured perceptions of male sexual coercion: (1) how sexually coercive (“likely to argue, protest, make verbal or physical threats, or use physical force in order to have sex with women”) each man was; (2) how frightening each man was to them; and (3) how “creepy” each man appeared to be. Three additional items assessed global perceived traits of each man, each of which is important in relationship evaluations (Simpson & Gangestad, 1992): (4) how kind each man was likely to be; (5) how committed each man was; and (6) how faithful each man was likely to be. All ratings were made on 5-point scales, where 1 = lowest 5%, 2 = lower 30%, 3 = middle 30%, 4 = upper 30%, 5 = highest 5%. Participants were told that the percentages referred to the general population of same-aged men. Correlations between the mean ratings on the three items that assessed coercion across men were: sexually coercive and “creepy,”r = .482; sexually coercive and frightening, r = .858; frightening and “creepy,” r = .714. As expected, these items loaded on a single factor.Two aggregate variables were created. First, each woman’s responses to the three coerciveness items (Sexual Coerciveness, Frightening, and “Creepy”) were summed to form an overall sexual coerciveness rating for each man she viewed. Second, the average women’s sexual coerciveness rating was computed for each man. Four different sets of averages were calculated, averaging the responses made by women who saw the same segment and the same set of men. For each woman, the average rating was calculated without her individual rating included in the composite.Women also reported the first day of their last menstrual period and their typical cycle length in order to estimate fertility (i.e., conception probability). We took women’s typical menstrual cycle length (sample mean = 28.90 days; SD = 3.3 days) into account and put each woman on a 29-day cycle before estimating her current day of the cycle (recognizing that ovulation occurs approximately 15 days prior to the end of the cycle [Baker & Bellis, 1995]). We then used actuarial tables based on medical data reported by Jöchle (1973) to estimate the fertility status (conception risk) of each woman.ResultsMultilevel RegressionsGiven the multilevel nature of the data (i.e., women’s responses to particular men nested within individual women), the data were analyzed using multilevel regression (SAS 8.0 PROC MIXED). Using maximum likelihood estimation, SAS estimated for each female participant the slope and y intercept of the relation between the average sexual coerciveness rating given to particular men by all women in the sample (a Level-1 predictor) and each female participant’s own sexual coerciveness ratings of those men (a dependent variable). SAS then estimated relations between those slopes and intercepts and two other female characteristics (Level-2 predictors): their fertility status and age. Because the average sexual coerciveness ratings were centered on 0, the y intercepts reflect mean differences in the ratings across women. Thus, associations between fertility status and age with intercept values (i.e., the main effects of conception risk and age) are their associations with the mean ratings.In all analyses, set (the first 40 men or last 36) and segment (first or last) were included as Level-2 predictors to account for variance associated with viewing one set of men or one segment versus another. Because set and segment effects carry no theoretical importance (i.e., simply by chance even given random assignment of the two sets of men, one might expect women to respond differently to the two sets of men or the two segments of tape), they are not reported. No age effects were found.Prediction 1According to Prediction 1, fertile women should, on average, judge men as more sexually coercive than should non-fertile women. The analyses yielded this effect , t(142) = 2.28, p = .024.We ran comparable analyses replacing women’s coerciveness ratings with the three other male traits/characteristics. As expected, no significant main effects emerged for kindness, t(144) = .64, p = .522, ns; faithfulness, t(144) = -1.00, p = .321, ns; or commitment, t(144) = -.96, p = .341, ns. These results provide no evidence that the effect for sexual coerciveness is due to a general tendency for fertile women to systematically perceive higher levels of other types of traits in men when they are in the fertile versus the non-fertile phase of their cycle.Prediction 2According to Prediction 2, average women’s ratings of male sexual coerciveness (irrespective of menstrual cycle status) should forecast fertile women’s ratings of sexual coerciveness better than non-fertile women’s ratings. This predicted effect corresponds to an interaction between conception risk3期 Christine E. Garver-Apgar, et al. Women’s Perceptions of Men’s Sexual Coerciveness Change Across the Menstrual Cycle 539and the ratings of men averaged across all women. As predicted, this interaction emerged, t(5302) = 2.08, p = .038.*Also as anticipated, conception risk did not interact with the average women’s ratings of kindness, t(5338) = -.01, p = .992, ns; faithfulness, t(5340) = -.61, p = .544, ns; or commitment, t(5340) = -.45, p = .649, ns, in predicting each individual woman’s own ratings of these characteristics. Once again, these results suggest that the sexual coercion effects are not attributable to the tendency for fertile women to give more prototypic ratings with regard to all traits.DiscussionThis study tested whether women’s judgments of men’s sexual coerciveness change in systematic ways across the menstrual cycle. Based on the assumption that sexual assault would have been more costly when ancestral women were fertile, we predicted that women would show enhanced sensitivity to male sexual coerciveness during the fertile phase of their reproductive cycle.As predicted, fertile women viewed men who were interviewed in a competitive, dating initiation situation as more coercive than did non-fertile women, consistent with the evolutionary-based notion that fertile women should err on the side of caution when evaluating men’s potential coerciveness. Also as predicted, fertile women’s judgments of men’s sexual coerciveness were better predicted by the average woman’s ratings of sexual coerciveness than were the judgments of non-fertile women. This supports the idea that, when fertile, women should be more attuned to salient cues of potential coerciveness that most women tend to see and less distracted by other features that are not reliably associated with coerciveness (or at least its perception). Demonstrating special design demands that other, more general processes do not account for hypothesized effects. In this study, we found no evidence for a general tendency for fertile women to perceive different levels (or be selectively attuned to cues) of three male characteristics central to mate selection: kindness, commitment, and faithfulness. This suggests that the reported effects may be specific to perceptions of potential male sexual coerciveness, as implied by our evolutionary hypothesis.Another possibility is that shifts in perceptions of male coercion are driven by increases in general fear at mid-cycle. In fact, previous work does not indicate that women experience either greater fear or generalized anxiety during the peri-ovulatory phase of * Because slopes are a function of standard deviations and correlations, one might wonder whether the slopes were greater for fertile women simply because their responses were more widely distributed. In fact, the standard deviations of women’s sexual coerciveness ratings did not covary with their conception risk, r = .074, ns. their cycle. If anything, feelings of greater fear and anxiety increase in the late luteal phase of the cycle (Solis-Oritz & Cabrera, 2002; Vandermolen, Merckelbach, & Vandenhout, 1988). Nevertheless, these findings are novel and require replication. Future studies could bolster confidence in a cognitive feature specially designed to adaptively bias perceptions of men’s sexual coerciveness by demonstrating even greater specificity than was done here. For instance, a study that rules out the possibility that women are more sensitive to any form of coercion (sexual or otherwise) mid-cycle would elegantly demonstrate specificity of design. Once the existence of a cyclically shifting bias in women’s sexual coercion perceptions is more firmly established, the next step is to identify the mediating cues used by women to make their assessments and to determine how women are differentially using cues across the menstrual cycle.Macrae, Alnwick, Milne, and Schloerscheidt (2002) have found that, when in the fertile phase of their cycle, women categorize men’s faces as “male” more rapidly and are more readily primed to process masculine personality traits and features (see also Johnston, Arden, Macrae, & Grace, 2003). This research importantly demonstrates social-cognitive changes across the menstrual cycle, but Macrae et al. did not provide a specific selectionist rationale for why one should expect the particular changes they document. One possible way Macrae et al.’s effects intersect with the current findings is that masculine facial features and traits are more salient to women because they are used to judge men’s coercive tendencies. In other words, our selectionist notions might indirectly explain the Macrae et al. findings.The current results illustrate the value of an evolutionary approach for investigating human sexual coercion and for identifying specific psychological mechanisms that may have evolved in women to combat male coercion.Author Notes: The authors thank Martie Haselton, Geoffry Miller, Randy Thornhill, and Ron Yeo for insightful discussion on the ideas contained in this article and for providing helpful comments on earlier versions of this paper.ReferencesAndrews, P., Gangestad, S. W., & Matthews, D. (2002). Adaptationism⎯how to carry out an exaptationist program. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 25, 489-504.Baker, R. R., & Bellis, M. A. (1995). Human sperm competition: Copulation, masturbation, and infidelity. London: Chapman & Hall.Bröder, A., & Hohmann, N. (2003). Variations in risk-taking across the menstrual cycle: An improved replication. Evolution and Human Behavior, 24, 391-398.Chavanne, T. J., & Gallup, G. G. Jr. (1998). Variation in risk taking behavior among female college students as a function of the menstrual cycle. Evolution and Human Behavior, 19, 27-32. Cosmides, L., & Tooby, J. (1992). Cognitive adaptations for social exchange. In J. H. Barkow, L. Cosmides, & J. Tooby (Eds.), The adapted mind: Evolutionary psychology and the generation of culture (pp. 168-228). London: Oxford University Press.540心 理 学 报 39卷Cosmides, L., Tooby, J., & Kurzban, R. (2003). Perceptions of race. Trends in Cognitive Science, 7, 173-179.Feinberg, D. R., Jones, B. C., Law-Smith, M. J., Moore, F. R. DeBruine, L. M., Cornwell, R. E., Hiller, S. G., & Perrett, D. I.. (2006). Menstrual cycle, trait estrogen level, and masculinity preferences in the human voice. Hormones and Behavior, 49, 215-222.Fiddick, L., Cosmides, L., & Tooby, J. (2000). No interpretation without representation: The role of domain-specific representations and inferences in the Wason selection task. Cognition, 77, 1-79. Gangestad, S. W., Simpson, J. A., Cousins, A. J., Garver-Apgar, C. E., & Christensen, P. N. (2003). Women’s preferences for male behavioral displays change across the menstrual cycle. Psychological Science,15, 203-207.Gangestad, S. W., & Thornhill, R. (1998). Menstrual cycle variation in women’s preference for the scent of symmetrical men. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B, 262, 727-733.Gangestad, S. W., & Thornhill, R. (2003). Female multiple mating and genetic benefits in humans: Investigations of design. In P. M. Kappeler & C. P. van Schaik (Eds.), Sexual selection in primates: New and comparative perspectives. Cambridge UK: Cambridge University Press.Gangestad, S. W., Thornhill, R., & Garver, C. E. (2002). Changes in women’s sexual interests and their partner’s mate retention tactics across the menstrual cycle: Evidence for shifting conflicts of interest. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B, 269, 975-982. Gangestad, S. W., Thornhill, R., & Garver-Apgar, C. E. (2005). Women’s sexual interests across the ovulatory cycle depend on primary partner developmental instability. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B, 272, 2023-2027.Garver-Apgar, C. E., Gangestad, S. W., & Thornhill, R. (2007). Human adaptations to ovulation: A review of research past and present and a look to the future.Acta Psycholigica Sinica. Haselton, M. G., & Buss, D. M. (2000). Error Management Theory: A new perspective on biases in cross-sex mind reading. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78, 81-91.Haselton, M. G., Nettle, D., & Andrews, P. (2005). The evolution of cognitive bias. In D. M. Buss (Ed.), Handbook of evolutionary psychology (pp. 724-746).Hoboken: Wiley.Haselton, M. G., & Nettle, D. (2006). The paranoid optimist: An integrative evolutionary model of cognitive biases. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 10, 47-66.Havlicek, J., Roberts, S. C., & Flegr, J. (2005). Women’s preference for dominant male odour: Effects of menstrual cycle and relationship status. Biology Letters, 1, 256-259.Kurzban, R., Tooby, J., & Cosmides, L. (2001). Can race be erased? Coalitional computation and social categorization. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 98, 15387-15392.Jöchle, W. (1973). Coitus-induced ovulation. Contraception, 7, 523-564.Johnston, L., Arden, K., Macrae, C. N., & Grace, R. C. (2003). The need for speed: The menstrual cycle and person construal. Social Cognition, 21, 89-100.Johnston, V. S., Hagel, R., Franklin, M., Fink, B., & Grammer, K. (2001). Male facial attractiveness: Evidence for hormone mediated adaptive design. Evolution and Human Behavior, 21, 251-267. Macrae C. N., Alnwick, K. A., Milne, A. B., & Schloerscheidt, A. M. (2002). Person perception across the menstrual cycle: Hormonalinfluences of social-cognitive functioning. Psychological Science, 13, 532-536.Park, J. H., Faulkner, J., & Schaller, M. (2003). Evolved disease-avoidance processes and contemporary anti-social behavior: Prejudicial attitudes and avoidance of people with physical disabilities. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior, 27, 65-87.Penton-Voak, I. S., & Perrett, D. I. (2000). Female preference for male faces changes cyclically-further evidence. Evolution and Human Behavior, 21, 39-48.Penton-Voak, I. S., Perrett, D. E., Castles, D., Burt, M., Koyabashi, T., & Murray, L. K. (1999). Female preference for male faces changes cyclically. Nature, 399, 741-742.Petralia, S. M., Gallup, G. G. Jr. (2002). Effects of a sexual assault scenario on handgrip strength across the menstrual cycle. Evolution and Human Behavior, 23, 3-10.Puts, D. A. (2005). Menstrual cycle and mating context affect women’s preference for male voice pitch. Evolution and Human Behavior, 26, 388-397.Rikowski, A., & Grammer, K. (1999). Human body odour, symmetry and attractiveness. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, B, 266, 869-874.Schaller, M., Conway, L. G., & Tanchuk, T. L. (2002). Selective pressures on the once and future contents of ethnic stereotypes: Effects of the communicability of traits. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82, 861-877.Simpson, J. A., & Gangestad, S. (1992). Sociosexuality and romantic partner choice. Journal of Personality, 60, 31-51.Simpson, J. A., Gangestad, S. W., Christensen, P. N., & Leck, K. (1999). Fluctuating asymmetry, sociosexuality, and intrasexual competitive tactics. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 76, 159-172.Solis-Ortiz, S., & Cabrera, M. C. (2002). EEG pattern of anxiety along the menstrual cycle. Revisita Mexicana de Psicologia, 19, 187-195. Sperber, D., & Girotto, V. (2002). Use or misuse of the selection task?: Rejoinder to Fiddick, Cosmides, and Tooby. Cognition, 85, 277-290. Thornhill, R. (1990). The study of adaptation. In M. Bekoff & D. Jamieson (Eds.), Interpretation and explanation in the study of behavior (pp 31-62). Boulder, CO: Westview.Thornhill, R. (1997). The concept of an evolved adaptation. In M. Daly (Ed.), Characterizing human psychological adaptations (pp. 4-13). London: Wiley.Thornhill, R., & Gangestad S. W. (1999). The scent of symmetry: A human sex pheromone that signals fitness? Evolution and Human Behavior, 20, 175-201.Thornhill, R. & Palmer, C. T. (2000). A natural history of rape. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press.Thornhill, R., Gangestad, S. W., Miller, R., Scheyd, G., McCollough, J, & Franklin, M. (2003). MHC, symmetry, and body scent attractiveness in men and women. Unpublished manuscript, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM.Vandermolen, G. M., Merckelbach, H., & Vandenhout, M. A. (1988). The possible relation of the menstrual-cycle to susceptibility to fear acquisition. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 19, 127-133.Williams, G. C. (1966). Adaptation and natural selection. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.Zebrowitz, L. A., Hall, J. A., Murphy, N. A., & Rhodes, G. (2002). Looking smart and looking good: Facial cues to intelligence and their origins. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28, 238-249.。