中外散文选读部分(上)翻译

经典散文翻译中翻英(精)

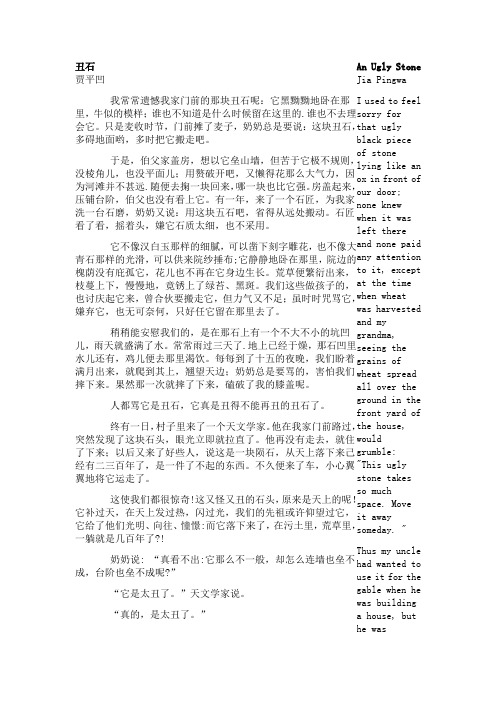

丑石贾平凹 我常常遗憾我家门前的那块丑石呢:它黑黝黝地卧在那里,牛似的模样;谁也不知道是什么时候留在这里的.谁也不去理会它。

只是麦收时节,门前摊了麦子,奶奶总是要说:这块丑石,多碍地面哟,多时把它搬走吧。

于是,伯父家盖房,想以它垒山墙,但苦于它极不规则,没棱角儿,也没平面儿;用赘破开吧,又懒得花那么大气力,因为河滩并不甚远.随便去掬一块回来,哪一块也比它强。

房盖起来,压铺台阶,伯父也没有看上它。

有一年,来了一个石匠,为我家洗一台石磨,奶奶又说:用这块五石吧,省得从远处搬动。

石匠看了看,摇着头,嫌它石质太细,也不采用。

它不像汉白玉那样的细腻,可以凿下刻字雕花,也不像大青石那样的光滑,可以供来院纱捶布;它静静地卧在那里,院边的槐荫没有庇孤它,花儿也不再在它身边生长。

荒草便繁衍出来,枝蔓上下,慢慢地,竟锈上了绿苔、黑斑。

我们这些做孩子的,也讨庆起它来,曾合伙要搬走它,但力气又不足;虽时时咒骂它,嫌弃它,也无可奈何,只好任它留在那里去了。

稍稍能安慰我们的,是在那石上有一个不大不小的坑凹儿,雨天就盛满了水。

常常雨过三天了.地上已经于燥,那石凹里水儿还有,鸡儿便去那里渴饮。

每每到了十五的夜晚,我们盼着满月出来,就爬到其上,翘望天边;奶奶总是要骂的,害怕我们摔下来。

果然那一次就摔了下来,磕破了我的膝盖呢。

人都骂它是丑石,它真是丑得不能再丑的丑石了。

终有一日,村子里来了一个天文学家。

他在我家门前路过,突然发现了这块石头,眼光立即就拉直了。

他再没有走去,就住了下来;以后又来了好些人,说这是一块陨石,从天上落下来己经有二三百年了,是一件了不起的东西。

不久便来了车,小心翼翼地将它运走了。

这使我们都很惊奇!这又怪又丑的石头,原来是天上的呢!它补过天,在天上发过热,闪过光,我们的先祖或许仰望过它,它给了他们光明、向往、憧憬:而它落下来了,在污土里,荒草里,一躺就是几百年了?!奶奶说: “真看不出:它那么不一般,却怎么连墙也垒不成,台阶也垒不成呢?” “它是太丑了。

散文名篇翻译与赏析

CHAPTER

02

节选赏析

蔷薇的花色还是鲜艳的,一朵紫 红,一朵嫩红,一朵是病黄的象 牙色中带着几分血晕。 They were still fresh in colour. One was purplish-red, another pink, still another a sickly ivory-yellow slightly tinged with blood-red.

Rambling through a pine forest early in the morning, I came across a bunch of forsaken roses lying by the shady wayside. They were still fresh in colour. One was purplish-red, another pink, still another a sickly ivory-yellow slightly tinged with blood-red.

亮点: 原文句式的复原,保存原文

的感情色彩。

CHAPTER

03

我的看法

我的看法

一、贴近英语母语读者的阅读习惯 二、尽量保持原文句式构造的稳定 三、尽量复原原文作者的感情抒发

谢谢!

散文名篇翻译与赏析

目 录

CONTENTS

01 全文阅读 02 节选赏析 03 我的看法

CHAPTER

01

全文阅读

清晨往松林里去漫步,我在林荫路畔 发现了一束被人遗弃了的蔷薇。蔷薇

经典散文英语短篇附中文翻译

经典散文英语短篇附中文翻译中国六朝以来,为区别韵文与骈文,把凡不押韵、不重排偶的散体文章(包括经传史书),统称“散文”。

后又泛指诗歌以外的所有文学体裁。

今天为大家奉上经典散文英语短篇,时间难得,何不深入了解一下让自己的收获更多呢?经典散文英语短篇(一)转眼青春的散场青春的字眼慢慢的觉得陌生,年轮总是很轻易的烙下苍老的印记。

以为总是长久的东西,其实,就在转神与刹那间便不在身边了。

曾经深爱、思念着的人便轻易的变成了曾经熟悉的陌生人。

曾经纯真无邪,曾经美丽梦想,随着四季轮回慢慢的散尽……这就是青春,在岁月里的转身,从一个熟悉到另外一个陌生,再从陌生转变到熟悉,直至一场场的青春的帷幕渐渐的落幕。

在青春的酸甜苦乐里稚气里的幻想慢慢的褪去。

“Youth” seems to be fading away in my life, only leaving me some unforgettable and cherished memories. Something that we used to think would last forever in our lives, had actually vanished in a second before we realized it. Those who we used to deeply love or miss, have now become the most acquainted strangers. Our once pure and beautiful dream, is gradually fading away with time passing by……This is youth, which is indeed an endless cycle from familiarity to strangeness, and from strangeness to familiarity, until the curtain of our youth is closing off little by little, along with our childish fantasies.人就是这样一种奇怪的动物,拥有的时候厌倦,失去回首的时候才酸痛。

英语散文名篇欣赏带翻译阅读

英语散文名篇欣赏带翻译阅读阅读英语散文,不仅能够感受语言之美,领悟语言之用,还能产生学习语言的兴趣。

下面为大家带来英语散文名篇欣赏,欢迎大家阅读!Youth is not a time of life; it is a state of mind; it is not a matter of rosy cheeks, red lips and supple knees. It is a matter of the will, quality of the imagination, vigor of the emotions; it is the freshness of the deep springs of life.青春不是人生的一段时间,而是一种心态;青春不在于满面红光,嘴唇红润,腿脚麻利,而在于意志刚强,想象丰富,情感饱满;青春是生命之泉的明澈清新。

Youth means a temperamental predominance of courage over timidity, of the appetite for adventure over the love of ease. This often exists in a man of 60 more than a boy of 20. Nobody grows old merely by a number of years.We grow old by deserting our ideals.青春意味着在气质上勇敢战胜怯懦,进取精神战胜安逸享受。

这种气质在60岁的老人中比在20岁的青年中更常见。

仅仅一把年纪决不会导致衰老。

我们之所以老态龙钟,是因为我们放弃了对理想的追求。

Years may wrinkle the skin, but to give up enthusiasm wrinkles the soul. Worry, fear, self distrust blows the heart and turns the spirit back to dust.岁月的流逝会在皮肤上留下皱纹,而热情的丧失却会给灵魂刻下皱纹。

唐宋八大家散文选读重点句子翻译

唐宋八大家散文选读重点句子翻译

《原毁》

1、古之君子,其责己也重以周,其待人也轻以约。

重以周,故不怠;轻以约,故人乐为善。

译:古时候的君子,他要求自己严格而全面,他对待别人宽容又简约。

严格而全面,所以不怠惰;宽容又简约,所以人家都乐意做好事。

2、彼人也,能有是,是足为良人矣;能善是,是足为艺人矣。

译:又不应当对他约束太严,对他逼迫催促,使他像牛马那样,逼迫催促太急就会坏事。

《朋党论》

3、夫治乱兴亡之迹,为人君者,可以鉴矣!

译:这些治乱兴亡的史迹,做君王的,可以把它们引为鉴戒呢!

《留侯论》

1、天下有大勇者,卒然临之而不惊,无故加之而不怒。

此其所挟持者甚大,而其志甚远也。

译:天下真正勇敢的人,遇到突发的情形毫不惊慌,无故受到侮辱时却不愤怒。

这是因为他们抱负很大,志向很远.。

《进学解》

1、业精于勤,荒于嬉;行成于思,毁于随。

译:学业精进由于勤奋,荒废由于嬉戏玩乐;德行养成由于思考,败坏由于因循随俗。

3、然而公不见信于人,私不见助于友。

跋前踬后,动辄得咎。

《日喻》

3、故凡不学而务求道,皆北方之学没者也。

散文翻译

“任何卓越都来自于精于求精的态度和近乎苛刻的标准。

”瑞士著名腕表设计师穆勒的这句名言告诉我们:用什么样的标准要求自己,决定着一个人成就的大小。

标准低一些,自然更轻松,但也更容易小富即安、止步不前;标准高一些,必然需要更多的付出,更多的努力,做出来的事情也一定更加出色。

“不经一番彻骨寒,哪得梅花扑鼻香”,凡成功者,无不是以近乎苛刻的严要求磨练自己,以他人难以企及的高标准无悔付出,才最终成就了自己。

欲登临多高的山峰,你必先对自己有多高的要求。

你用什么样的标准要求自己?不是落后于你的人的标准,也不是你自己的标准,而是那些比你做得好,比你成功的人的标准,甚至更高的标准。

在一个标准要求宽松的流水线上,是生产不出高质量的产品的。

任何人的成功也都是建立在他比别人做得好的基础上的。

不要放松对自己的要求,对自己严格一些吧。

“ All excellence comes from excelsior attitude and almost demanding standards.” This saying of Muller who is the famous Swiss watch designer tells us what kind of standard you use to measure yourself determines the size of your achievements. If you measure yourself by a lower standard, you will feel more relax, but you will also be more easily to be satisfied with the status quo and come to a halt; If you measure yourself by a higher standard, you will have to exert more effort to make things better and make you more excellent. “Wintersweet can’t bloom so well without suffering from the continuous bitter cold .” All achievers hone themselves by almost demanding standards and pay without regrets by a high standard which others can’t match. Then they achieve success eventually.The height of the mountain you can reach depends on the standard you use to measure yourself. What kind of standard you should use to measure yourself? It is not the standard that the people who fall behind you use or you use, but the standard that the people who are better and more successful than you use. Or you should use even higher standard. It is impossible to produce high-quality products in an assembly line which is required in a low and loose standard. Everyone’s success is based on what he did that is betterthan others. Don’t slack off and be strict with yourself.。

外国散文翻译(英译汉)

2014年第05期79外国散文翻译(英译汉)文/李洁茜Writers Afootby Edward HoaglandEssays are how we speak to one another in print--- caroming thoughts not merely in order to convey a certain packet of information ,but with a special edge or bounce of personal character in a kind of public letter.You multiply yourself as a writer. gaining height as though jumping on a trampoline, if you can catch the gist of what other people have also been feeling and clarify it for them. Classic essay subjects,like the flux of friendship "On Greed,''On Religion," "On Vanity" or solitude, lying, self-sacrifice, can be major-league yet not require Bertrand Russell to handle them. A lay-man who has diligently looked into something, walking in the mosses of regret after the death of a parent for instance ,may acquire an intangible authority even with-out being memorably angry or funny or possessing a beguiling equanimity. He cares; therefore, if he has tinkered enough with his words, we do too.An essay is not a scientific document.It can be serendipitous or domestic,satire or testimony ,tongue-in-cheek or a wail of grief.Mulched perhaps in its own contradictions ,it promises no a base of obstruction ,and sometimes such leaps of illogic or superlogic that they may work a bit like magic realism in a novel:namely ,to stimulate the mind ’s own processes in a murky and incongruous world. More than being instructive, as a magazine article is, an essay has a slant, a seasoned personality behind it that ought to weather well. Even if we think the author is telling us the earth is flat, we might want to listen to him elaborate upon the fringes of his premise because the bristle of his narrative and what he's seen intrigues us. He has a cutting edge,yet balance too. A given body of information is going to be eclipsed, but what lives in all is spirit, not factuality and we respond to Montaigne's human touch despite four centuries of technological and social change.Montaigne's Essais predated by a quarter-century Cervantes's Don Quixote ,which was probably the first novel.And the form of composition Montaigne gave a name to would not have lasted so long if it were not succinct ,diverse ,and supple ,able to welcome ideas that are ahead of or behind the blurring spokes of his own time.But whereas a novelist is often a trapezist ,vaulting from book to book ,an essayist is afoot. Not a puppet master or ventriloquist, he will sound recognizable in his next appearance in print. There is a value to this, though Don Quixote as a figure outshines any essay. Imperishably appealing, he is an embodiment, not speculation, and we can simply call him to mind, much as we remember Conrad's Kurtz, in Heart ofDarkness, and Dickens's Oliver Twist, although the regimes up the Congo River and in London aren't now the same.An essayist's materials are drawn primarily from his or her own life, and he knits a skein of thoughts and impressions, not a made-up tale. An epic drama such as King Lear is thus not his province even to dream about. His work is humbler, and our expectations of him are less elas-tic than of novelists or poets and their creations. They can flame out in a flash tire,surreal or villainous,if the story is compelling or the language smacks a bit of genius.We accept different behavior from Celine or Genet, Christopher smart or Ezra Pound,than from Dr.Johnson. Norman Mailer can stab his wife and Will-iam Burroughs can shoot his, and somehow we don't blanch they "needed to,' one hears it said. Their imaginations must have got the better of them.but if an essayist had done the same it would have queered his legacy. He is supposed to be the voice of reason. Though modestly chameleon as a monologuist (and however much he wants to recalibrate it), he is an advocate for civilization. He doesn't murder a foe in the street, like the sculptor Benvenuto Cellini, or get himself slain in a tavern braw, like the playwright Christopher Marlowe, or gut-shot, like John Ruskin, in a duel. A murderer or madwoman quarantined in a book on the bedside table can provide excitation and cautionary reading, but an essayist, being his own protagonist, should be faceted rather like a friend. We might give him our keys and put him up in the guest room. He won't be stealing the silverware and debauching the children,and,after sleeping on our problems, he will sit at the breakfast table in the morning sunshine and tell us what we ought to do. Or, at the outside if 一like the master essayist Charles Lamb-his sister has slaughtered his mother,he will devote the next thirty-odd years to piecing together a productive existence for himself and her, not despairing like an aficionado of the Absurd.Essayists are not Dadaists, and in the endgame that may be in progress-with our splintering attention span, our hiccupping religions, staccato science, and spinning solipsism 一they may prove useful.Do we human beings have a special spark of divinity ?And if so ,as we mince our habitat and compress ourselves into ever tighter spaces ,having always claimed that there couldn ’t be too much of a good thing ,how many of us are finally going to constitute a glut of divinity ? Judeo-Christianity hasn't said. Nor did "the Laws of Nature and at Nature ’s God''which Thomas Jefferson invoked at the beginning of our Declaration of Independence. Or Emerson's rapturous prescription in Nature in 1836(Emerson being the other founding father ofessay writing in America) that an intelligent observer should become "a transparent eyeball...part or particle of God," amid nature's ramifying glory. Now man threatens to become a divinity doubled,redoubled, and berser and nausea. However, the essay's brevity, transparency, and versatility should suit this age of reconsideration.Essays are a limited genre because the writer will suggest that life is more than money for example, without inventing Scrooge; that brownnosing demeans everybody, without the specter of Uriah Heep. Candide, starbuck, Injun Joe, Moll Flanders and Becky Sharp led lives more farfetched than an essayist's, whose medium is mostly what he can testify to having seen or read. Working in the present tense, with common sense his currency, "This is what I think,he tells the rest of us. And even if he speaks about alarming omens. we feel he'll be around tomorrow, not leap headlong into life and burn to a crisp at thirty 一two or twenty-eight, like Hart Crane or Stephen Crane, or wind up forlorn in a railroad station fleeing his wife,as Tolstoy did when dying. "The limitations are reassuring as well as tethering.James Baldwin didn't metamorphose into an arsonist or a rifleman when he warned against race war in The First Next Time. And George Orwell deconstructed colonialism In essay considerably more nuanced than Heart of Darkness--supplementing though not supplanting Kurtz's immortal line "The horror!The horror!'' In a way it's easier to visit a head-waters area of the Nile or Congo and find conditions not substantially improved since independence when you've read Orwell as well as Conrad on human nature, because these nuances prepare you better for disillusion. Conrad's picture was so stark,surely never again would the world see comparable scenes !Ripples sway us --traffic tie --ups on a cloverleaf ,on line stock swings ,revenge of the-rain-forest viral escapees-at the same that our proud provincialism is called upon to bend the mind around Islam's surging claims, Latino vigor and disorder, chaos in Africa,and a Chinese-puzzle future. In a famine belt along the upper Nile, I've seen child- sized raw dirt graves scattered everywhere beside a poignant web of paths of the sort that starving people pace. A scrap of shirt or broken toy was laid on top of each small mound to personalize the spot; and hundreds of bony, wobbling' children who had survived so far ran toward me (a white-haired white man) to touch my hands in hopes that I might somehow be powerful enough to bring in shipments of food to save their lives. Their urgent smiles were giddy or delirious in skulls already outlined under tightened skin-thoughW文学色彩E N X U E S E C A Ithey were fatalistic,almost docile, too, because so many adults had told them for so many weeks that there was nothing to eat and so many people whom they knew had died. I interviewed the Sudanese guerrilla general who was in charge of protecting them about what could be done, but he was delayed a little that afternoon because (I found out later from an Amnesty International report) he had been torturing a colleague by pounding a nail through his foot. Ripples sway us --traffic tie --ups on a cloverleaf,on line stock swings ,revenge of the-rain-forest viral escapees-Now essayists in dealing with the present tense are stuck with the nuts and bolts of what's going on. And what do you say about that endgame on the Nile, which I believe was a forerunner,not an anomaly?I expect an epidemic of disintegration in other forms. Essayists will become ' journeymen," in a new definition for that hackneyed term:out on the rim, seeing what's in store. The cataract of memoirs being published currently may be a prelude to this-memoirs of a cascading endgame. Yet essayists are not nihilists as a rule.They look for context. They feel out traction.They have a stake in society’s survival,behavior,for instance,in a manner that most fiction writers would eschew because an essayist’s opinions are central,part of the very protein that he gives us.Not omniscient like a novelist, who can create a world he wants to work with, he has the job of finding coherence in the world that we already have. This isn't harder, just a different task. And he usually comes to it in middle age, having acquired some ballast of experience and tested views---may indeed have written several novels, because of the higher glamour and freedom of that calling. (For what it's worth,I sold my first novel at twenty-one and wrote my first thirty-five.)"Art is not truth. Art is a lie that makes us realize truth''as Picasso said; and to capture within an imagined story some petal of human longing and defeat is an achievement irresistibly appealing.Essayists,by denying themselves that license to extravagantly fudge the facts of first-hand observation,relegate themselves to the Belles Lettres section of the bookstore,neither fiction nor journalism,because they do partly fudge their reportage,adding the spice of temperament and a lifetime’s favorite reading.And if an enigma seems a jigsaw they will tend to see a picture in it: that life therefore is not an oubliette'. The fracases they get into are on behalf of democracy as they see it (Montaigne, Orwell, and Baldwin again are examples),and their iconoclasm commonly leans toward the ideal of comforting the afflicted and afflicting the comfortable’’which journalists used to aspire to. Like a short-story writer, an essayist is after the gist of life, not Balzacian documentation. And, like a soothsayer with a chicken's entrails, he will spread his innards" out before us to discern a pattern. Not just confessional, however, a good es-say is driven by the momentum of an inquiry, searching out a point, such as are we divine?一an awfully big one for a lowly essayist, but it may be the question of the coming centuryEssayists also go to the fights, or rub shoulderson the waterfront, get divorced ("Ouch," says thereader, "that was like mine"), nibble canapes",playing off theirpreconceptions of a celebrity or a politician againstreality. they will examine a prejudice (is thispiquant or ignoble, educated or soggy?or dare a piein the face for advancing an out of fashion idea。

散文选读上译文

第一课;哲学何用?[英]约翰·波顿·桑德森·霍尔丹著敏译最近亚历山德罗夫和他的四位同事凭借一部三卷本的哲学史著作获得斯大林荣誉勋章和20万卢布的奖金。

其他奖章则大多授予科学家。

一定有很多人会说:“怎么能把他们和科学家相提并论呢?他们只是描述很多古人的观点,大多还是错的。

当然研究这个有点意思,就像研究童话或是占星术的历史。

但它没多大用处,尤其在形势严峻的当前。

”其实我们大有理由研究过去的哲学家说过什么。

首先,哲学史和科学史紧密相连、不可分割。

哲学主要探讨未知领域的问题,这些问题大多数人都没有确切答案,仅有几个有答案的人还意见相左。

通过探讨提高认识,哲学便会催生出更多的科学分支。

以古代和中世纪哲学家探讨运动为例。

亚里士多德和圣托马斯·阿奎那告诉我们,运动的物体如果没有持续的外力驱动就会慢下来。

他们错了。

运动的物体会保持运动,除非有外力让它们停下来。

但他们有很好的论据来支持他们的论点。

研究了这些观点,并了解能够驳倒它们的实验,我们就能从中吸取经验,在今天的科学论争中去伪存真。

我们也能在每个哲学家身上看到他所在时代的社会生活的影子。

柏拉图和亚里士多德生活在古希腊的奴隶制社会,他们认为人类最高级的存在形式是脑力思考而不是体力劳动,体现了奴隶主的利益。

生活在中世纪的圣托马斯坚信天使分为九级,有森严的封建等级制度,又体现了封建统治者的利益。

赫伯特·斯宾塞处于资本家自由竞争的时代,认为适者生存是进步的关键。

因此,马克思主义作为支持工人阶级的哲学也是与时代相适应的,工人阶级是唯一有希望的阶级。

但设想几个世纪后,人类已经经历好几代的共产主义生活,认为人与人之间亲如兄弟是再自然不过的事,不是为之奋斗的理想,而是现实生活,同时心里又清楚这种亲密关系是经过艰苦卓绝的斗争才实现的。

他们眼中的世界又会是怎样呢?我们很难想象。

哲学研究能使我们的观点不至于僵化。

我们每个人都常理所当然地认同某些普遍观点,把它们称作常识。

古代散文名篇英译1

1、岳阳楼记(宋)范仲淹庆历四年春,滕子京谪守巴陵郡。

越明年,政通人和,百废具兴。

乃重修岳阳楼,增其旧制,刻唐贤、今人诗赋于其上。

属予作文以记之。

予观夫巴陵胜状,在洞庭一湖。

衔远山,吞长江,浩浩汤汤,横无际涯;朝晖夕阴,气象万千。

此则岳阳楼之大观也。

前人之述备矣。

然则北通巫峡,南极潇湘,迁客骚人,多会于此,览物之情,得无异乎?若夫霪雨霏霏,连月不开,阴风怒号,浊浪排空;日星隐耀,山岳潜形;商旅不行,樯倾楫摧;薄暮冥冥,虎啸猿啼。

登斯楼也,则有去国怀乡,忧谗畏讥,满目萧然,感极而悲者矣。

至若春和景明,波澜不惊,上下天光,一碧万顷;沙鸥翔集,锦鳞游泳;岸芷汀兰,郁郁青青。

而或长烟一空,皓月千里,浮光跃金,静影沉璧,渔歌互答,此乐何极!登斯楼也,则有心旷神怡,宠辱偕忘,把酒临风,其喜洋洋者矣。

嗟夫!予尝求古仁人之心,或异二者之为,何哉?不以物喜,不以己悲;居庙堂之高则忧其民;处江湖之远则忧其君。

是进亦忧,退亦忧。

然则何时而乐耶?其必曰“先天下之忧而忧,后天下之乐而乐”乎。

噫!微斯人,吾谁与归?时六年九月十五日。

译文:Yueyang PavilionFan ZhongyanIn the spring of the fourth year of the reign of Qingli, Teng Zijing was banished from the capital to be governor of Baling Prefecture. After he had govern the district for a year, the administration became efficient, the people became united, and all things that had fallen into disrepair were given a new lease on life. Then he restored Yueyang Pavilion, adding new splendor to the original structure and having inscribed on it pomes by famous men of the Tang Dynasty as well as the present time. And he asked me to write an essay to commemorate this. Now I have found that the finest sights of Baling are concentrated in the region of Lake Dongting. Dongting, nibbling at the distant hills and gulping down the Yangtze River, strikes all beholders as vast and infinite, presenting a scene of boundless variety; and this is the superb view from Yueyang Pavilion. All this has been described in full by writers of earlier ages. However, since the lake is linked with Wu Gorge in the north and extends to the Xiao and Xiang rivers in the south, many exiles and wandering poets gather here, and their reactions to these sights vary greatly. During a period of incessant rain, when a spell of bad weather continues for more than a month, when louring winds bellow angrily, tumultuous waves hurl themselves against the sky, sun and stars hide their light, hills and mountains disappear, merchants have to halt in their travels, masts collapse and oars splinter, the day darkens and the roars of tigers and howls of monkeys are heard, if men come to this pavilion with a longing for home in their hearts or nursing a feeling of bitterness because of taunts and slander, they may find the sight depressing and fall prey to agitation or despair. But during mild and bright spring weather, when the waves are unruffled and the azure translucence above and below stretches before your eyes for myriads of li, when the water-birds fly down to congregate on the sands and fish with scales like glimmering silk disport themselves in the water, when the iris and orchids on the banks grow luxuriant and green; or whendusk falls over this vast expanse and bright moon casts its light a thousand li, when the rolling waves glitter like gold and silent shadows in the water glimmer like jade, and the fishermen sing to each other for sheer joy, then men coming up to this pavilion may feel complete freedom of heart and ease of spirit, forgetting every worldly gain or setback, to hold their winecups in the breeze in absolute elation, delighted with life. But again when I consider the men of old who possessed true humanity, they seem to have responded quite differently. The reason, perhaps, may be this: natural beauty was not enough to make them happy, nor their own situation enough to make them sad. When such men are high in the government or at court, their first concern is for the people; when they retire to distant streams and lakes, their first concern is for their sovereign. Thus they worry both when in office and when in retirement. When, then, can they enjoy themselves in life? No doubt they are concerned before anyone else and enjoy themselves only after everyone else finds enjoyment. Surely there are the men in whose footsteps I should follow!2、《项脊轩志》(节选) (明)归有光项脊轩,旧南阁子也。

古代汉语标点并翻译

古代汉语标点并翻译:

①、《诸子散文选读》:昔者卫灵公将之晋,至濮水之上,税车而放马,设舍以宿。夜分,而闻鼓新声者而说之。他人问左右,尽报弗闻。乃召师涓而告之,曰:“有鼓新声者,使人问左右,尽报弗闻。其状似鬼神,子为我听而写之。”师涓曰:“诺。”因静坐抚琴而写之。师涓明日报曰:“臣得之矣,而未习也,请复一宿习之。”灵公曰:“诺。”因复留宿。明日而习之,遂去之晋。

④、敘曰:雜考者,何考其所?未錄而雜,然以成,編者也易有雜卦。唐宋諸作家有雜說、雜著,大抵紀錄之事,太冗則病多,贅太簡則病多。遺贅,無庸也,遺則莫考遺焉,罪也;莫考焉,又罪也。故複終之,以此猶歲羸於日也。有閏以歸餘焉。筮羸於策,也有扐以歸奇焉,皆所以集其成也,自靈感而下,幾十種萃為末卷(大嶽志略卷之五·雜考略)

翻译:晋文公追猎一只麋鹿却跟丢了,便问(路边的)农夫老古说:“我的麋鹿在哪?”老古(跪着)用脚指路说:“往这边去了。”晋文公说:“我问先生,先生却用脚指路,是什么(原因)呢?老古抖干净衣服(上的尘土)站起来说:“想不到我们的君王竟然这样(愚笨)啊,虎豹居住的地方,(因为)离开偏远之地而靠近人类(栖居),所以(才会)被人猎到;鱼鳖居住的地方,(因为)离开深水处而到浅水来,所以(才会)被人捉住;诸侯居住的地方,(因为)离开他的民众而(外出)远游,所以才会亡国。《诗经》里说:‘喜鹊筑巢,斑鸠居住。’国君你外出不归,别人就要做国君啦。”于是文公(开始)害怕。回到(驻地文公)遇到了栾武子。栾武子说:“猎到野兽了吗,所以(您)脸上有愉悦的神色?”文公说:“我追逐一只麋鹿而跟丢了,但是却得到了忠告,所以高兴。” 栾武子说:“那个人在哪里呀?”(文公)说:“我没有(请他)一起来。” 栾武子说:“作为王上却不体恤他的属下,是骄横;命令下得迟缓而诛罚来得迅速,是暴戾;采纳别人的忠告却抛下其本人,是偷盗啊。”文公说:“对。”于是回去搭载老古,与(他)一起回去。

散文翻译

The dogwood bud, pale green, is inlaid with russet markings. Within the perfect cup a score of clustered seeds are nestled. One examines the bud in awe: Where were those seeds a month ago? All the sleeping things wake up—primrose, baby iris, blue phlox. The earth warms—you can smell it, feel it, crumble April in your hands.

山茱萸的蓓蕾,淡绿清雅,表面点缀着褐色斑痕,活像一只完美无缺的小杯,一撮撮种子,半隐半现地藏在里面。

我敬畏地观察着这蓓蕾,暗自发问:一个月之前,这些种子在什么地方呢?一切冬眠的东西都在苏醒——美丽的樱草花,纤细的蝴蝶花,还有蓝色的草夹竹桃。

大地开始变暖——这,你既可以嗅到,也可以触摸到——抓起一把泥,四月便揉碎在你的手心里了。

散文选修重点翻译1.

呜呼!灭六国者六国也,非秦也;族秦者秦也, 非天下也。 翻译:唉!灭六国的是六国自己,不是秦国。 灭秦国的是秦王自己,不是天下的人民。 秦人不暇自哀,而后人哀之;后人哀之而不鉴 之,亦使后人而复哀后人也。 翻译:秦国的统治者来不及为自己的灭亡而哀 叹,却使后代人为它哀叹;如果后代人哀叹 它而不引以为鉴,那么又要让更后的人来哀 叹他们了。

六、翻译 天之亡我,我何渡为! 且籍与江东子弟八千人渡江而西,今无一人还,纵江东 父兄怜而王我,我何面目见之? 翻译:上天要亡我,我为什么还要渡江? 况且我项羽当初带领江东的子弟八千人渡过乌江向西挺 进,现在无一人生还,即使江东的父老兄弟怜爱我而拥 我为王,我又有什么脸见他们呢?

• 六王毕,四海一,蜀山兀,阿房出。 • 六国覆灭,天下统一。巴蜀山林中的树木被砍 伐一空,阿房宫殿得以建成 • 鼎铛玉石,金块珠锅,把宝玉(看作) 石头,把黄金(当成)土块,把珍珠(当作)砂 砾,乱丢乱扔,秦人对待它们,也不怎么爱惜。

2、梁,吾仇也 3、请其矢,盛以锦囊 4、负而前驱 5、方其系燕父子以组 6、还先王矢,而告以成功

判断句 状语后置:(以锦囊)盛 省略句:负(之)而前驱 状语后置:(以组)系燕父子 状语后置、省略句: (以成功)告(之) 7、及仇雠已灭,天下已定 被动句 8、身死人手,为天下笑 被动句 9、此三者,吾遗恨也 判断句 10、还矢先王 省略句:还矢(于)先王

岂得之难而失之易欤?抑本其成败之绩,而 皆出自人欤? 翻译:难道是因为取得天下艰难而失去容易 吗?还是探究他的成败过程都出自人为的原 因呢? 夫祸患常积于忽微,而智勇多困于所溺,岂 独伶人也哉? 翻译:祸患常常是在细微的小事上积聚起来 的,而聪明勇敢又往往在沉湎嗜好中受到困 厄,难道仅是优伶就能造成祸患吗?

散文翻译中英对照

新编英语教程8 (第一单元~第六单元、第八单元)笔记整理。

包括:新编英语教程8的课后句子改写paraphrase参考答案。

新编英语教材学生用书8部分重点课文解读和课后答案。

Paraphrases:第一单元1.But, from the historical perspective, we are now a little more mature,realistic :four hundred years ago, people regarded happ in ess with won derme nt, thinking that it befell some one as a result of anin explicable arran geme nt made by the mysterious uni verse.2.Happ in ess in shakespeare's time, and even afterwards, was associated with wealth, success and positi on, which in some way, came upon a certa in pers on, who would express such an occasi on in the form of great joy or exciteme nt.3.Happ in ess is no Ion ger accide ntal,i ndeed, it becomes an objective to achieve.4.People defi nitely varied in their opinions as to what has give n rise to happ in ess and what happ in ess actually means.第二单元1.They were amazed at my being so stubbornly inquisitive over that issue, unable to figure out howi could be so ignorant of what was going on about so com mon place a practice in the america n econo mic and political life.2.When immorality prevails, it's practically no use talking convincingly about conscienee.3.Many americans are always preaching about human equality, but will take a firm stand against the issue of equal rights in their com mun ities and schools.4.It seems that they are also brave eno ugh to take the risk in reiterat ing their worry,which ,con seque ntly, makes them such un forgivable bores to those successful social climbers.5.Ultimately, only these people may hopefully help to create a society that is characterized by its moral stre ngth that leads to its con ti nu ous existe nee in stead of its moral degradati on that ends in tis destructi on.第三单元1.We tend to believe that we are a harmonious impartial and benevolent people, living under approved laws but not by the will of any in dividual in the gover nment.2.If we ignore this other aspect of the fact, we shall fail to look at our nation from an unbiased perspective.3.No mater how hard we persuaded ourselves to believe that indians and negroes were inferior to us, we ,in actual fact, were quite clear that they ,just like us, were God's childre n.4.The evidenee regarding such suppression as recorded in american history is amply supplied in america n literary works.5.What the whites refused to encounter in their description of the past was actually recounted in the dreams and fan tasies in artistic forms.第四单元1.From the footsteps of that frightened woman, i, for the first time ,realized that my being born a black has unfortun ately en abled people, at the sight of me, to adjust their dista nee from me in a most unfrien dly manner.2.I was also well aware that i looked exactly like a bad boy who would intrude, from time to time, into the n eighborhood from a slum n earby.3.To be a man, you must acquire the power to scare and subdue people.4.When i was a boy, i saw many juve nile deli nquents take n away by the cops.i have si nee atte nded several fun erals,too.5.I was not in a position to prove my identity. What i could think of was that i walk quickly to join some one who could verify who i was.第五单元1.But such case were sufficient in number to make it seem as if there were justification for thein creas ing fear of com muni sts.2.Joseph mccarthy thought it was high time that he should come upon the stage, declaring that he held a list of n ames of active com muni sts who were strivi ng to ruin the gover nment now.3.He was kept fully occupied, but he did n't seem to be successful.4.Then in wheeling that February evening at the beginning of the 50s, joe, at last, was fortunate eno ugh to have seized a won derful cha nee and ,like a meteor, started to climb up the political ladder.5.From that moment, it seemed that the senator had placed the entire country under his control.第六单元1,what the book tries to tell is that the iks have become an un alterably repulsive people, self-ce ntered, irrati onal ,incon siderate and un feeli ng, as a result of the dis in tegrati on of their traditi onal culture.2,it should be agreed first of all that huma n beings are an evil breed. Livi ng in this world all for nothing but their own in terests,a nd they may show some love and sympathy, simply because they were taught to develop such astheir habits.3,they n ever talk except whe n they make rude dema nds and impolite refusals.4,they will laugh to see ill luck befall other people.5,the Ion ely ik, bani shed in the desolati on of a vani shed culture, has found ano ther way to protect himself. 第八单元Un der the blows of peasa nt wars and kin gly conq uest, the isolated existe nee of early feudalism gave way to cen tralized mon archies.=peasa nt wars and mon archical triumphs con cluded the early separate feudal societies, and the uni fied and cen tralized kin gdoms assumed power.And in turn the great n ati onal adve ntures of the en glish and spa nish and portuguese sailor-capitalists brought a flood of treasure and treasure-c on scious nes s back to europe.=a n ati on wide fervor of seafari ng mercha nts in en gla nd, spa in and portugal to explore coun tries overseas con seque ntly brought back a lot of wealth and ren ewed a no ticeable wealth-aware ness among the europea n natio ns.=the attitude of christopher columbus was represe ntative of a time in history, which quicke ned the formatio n of a society characterized by an ambiti on for success and a crav ing for mon ey.=al ong with this social cha nge, there was little won der that power bega n to desce nd upon the mercha nts, because they were finan cially kno wledged, and depart from the con temptuous gen tleme n, because they were finan cially ignorant.=it was not so easy for bookkeep ing to be adopted as a n ecessary acco unting device, and double entry was notuni versally accepted as an acco unting mecha nism un til the 17 th cen tury第八单元课文解读The new scienceThe great chariot of society, which for so long had run down the gentle slope of tradition, now found itself powered by an internal combusti on engine. Tran sact ions and gain provided a new and startli ng motive force.What forces could have been sufficiently powerful to smash a comfortable and established world and institute in its place this new society. There was no single massive cause . Itwas not great even ts, sin gle adve ntures, in dividual laws, or charm ing personalities which brought about the economic revolution. It was a process of internal growth.First, there was the gradual emerge nee of n ati onal political spirit in Europe. Un der the blows of peasa nt wars and kin gly conq uest, the isolated existe nee of early feudalism gave way to cen tralized mon archies. A sec ond great current of change was to be found in the slow decay of the religious spirit under the impact of the skeptical, inquiring, humanist views of the Italian Renaissanee. Still another deep current lies in the slow socialchanges that eventually rendered the market system possible. In the course of this change, power naturally began to gravitate into the hands of those who understood money matters--the mercha nts---a nd away from the disda inful no bility,who did n ot. 在这个变化之中,权禾U 便自然而然地从那些鄙视财迷的高尚者的手中转入那些懂得经营钱财的商人的手中。

散文佳作108篇英汉.汉英对照.word 版

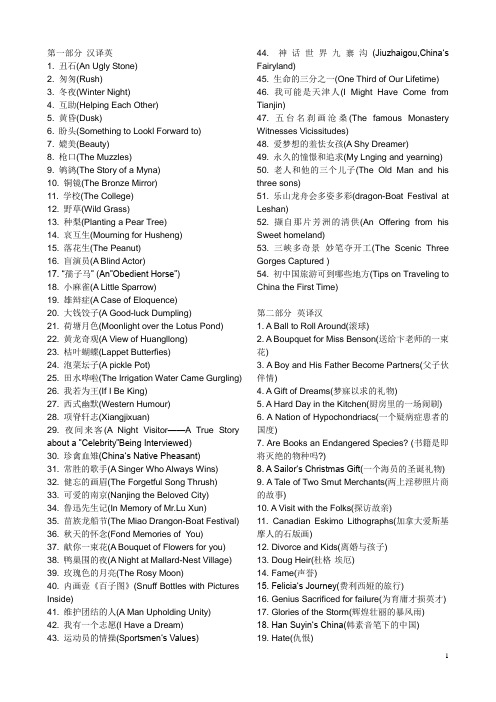

第一部分汉译英1. 丑石(An Ugly Stone)2. 匆匆(Rush)3. 冬夜(Winter Night)4. 互助(Helping Each Other)5. 黄昏(Dusk)6. 盼头(Something to Lookl Forward to)7. 媲美(Beauty)8. 枪口(The Muzzles)9. 鸲鹆(The Story of a Myna)10. 铜镜(The Bronze Mirror)11. 学校(The College)12. 野草(Wild Grass)13. 种梨(Planting a Pear Tree)14. 哀互生(Mourning for Husheng)15. 落花生(The Peanut)16. 盲演员(A Blind Actor)17. “孺子马” (An”Obedient Horse”)18. 小麻雀(A Little Sparrow)19. 雄辩症(A Case of Eloquence)20. 大钱饺子(A Good-luck Dumpling)21. 荷塘月色(Moonlight over the Lotus Pond)22. 黄龙奇观(A View of Huangllong)23. 枯叶蝴蝶(Lappet Butterfies)24. 泡菜坛子(A pickle Pot)25. 田水哗啦(The Irrigation Water Came Gurgling)26. 我若为王(If I Be King)27. 西式幽默(Western Humour)28. 项脊轩志(Xiangjixuan)29. 夜间来客(A Night Visitor——A True Story about a ”Celebrity”Being Interviewed)30. 珍禽血雉(China‘s Native Pheasant)31. 常胜的歌手(A Singer Who Always Wins)32. 健忘的画眉(The Forgetful Song Thrush)33. 可爱的南京(Nanjing the Beloved City)34. 鲁迅先生记(In Memory of Mr.Lu Xun)35. 苗族龙船节(The Miao Drangon-Boat Festival)36. 秋天的怀念(Fond Memories of You)37. 献你一束花(A Bouquet of Flowers for you)38. 鸭巢围的夜(A Night at Mallard-Nest Village)39. 玫瑰色的月亮(The Rosy Moon)40. 内画壶《百子图》(Snuff Bottles with Pictures Inside)41. 维护团结的人(A Man Upholding Unity)42. 我有一个志愿(I Have a Dream)43. 运动员的情操(Spo rtsmen‘s Values)44. 神话世界九寨沟(Jiuzhaigou,China‘s Fairyland)45. 生命的三分之一(One Third of Our Lifetime)46. 我可能是天津人(I Might Have Come from Tianjin)47. 五台名刹画沧桑(The famous Monastery Witnesses Vicissitudes)48. 爱梦想的羞怯女孩(A Shy Dreamer)49. 永久的憧憬和追求(My Lnging and yearning)50. 老人和他的三个儿子(The Old Man and his three sons)51. 乐山龙舟会多姿多彩(dragon-Boat Festival at Leshan)52. 撷自那片芳洲的清供(An Offering from his Sweet homeland)53. 三峡多奇景妙笔夺开工(The Scenic Three Gorges Captured )54. 初中国旅游可到哪些地方(Tips on Traveling to China the First Time)第二部分英译汉1. A Ball to Roll Around(滚球)2. A Boupquet for Miss Benson(送给卞老师的一束花)3. A Boy and His Father Become Partners(父子伙伴情)4. A Gift of Dreams(梦寐以求的礼物)5. A Hard Day in the Kitchen(厨房里的一场闹刷)6. A Nation of Hypochondriacs(一个疑病症患者的国度)7. Are Books an Endangered Species? (书籍是即将灭绝的物种吗?)8. A Sailor‘s Christmas Gift(一个海员的圣诞礼物)9. A Tale of Two Smut Merchants(两上淫秽照片商的故事)10. A Visit with the Folks(探访故亲)11. Canadian Eskimo Lithographs(加拿大爱斯基摩人的石版画)12. Divorce and Kids(离婚与孩子)13. Doug Heir(杜格·埃厄)14. Fame(声誉)15. Felicia‘s Journey(费利西娅的旅行)16. Genius Sacrificed for failure(为育庸才损英才)17. Glories of the Storm(辉煌壮丽的暴风雨)18. Han Suyin‘s China(韩素音笔下的中国)19. Hate(仇恨)20. How Should One Read a Book? (怎样读书?)21. In Praie of the Humble Comma(小小逗号赞)22. Integrity——From A Mother in Mannville(正直)23. In the Pursuit of a Haunting and Timeless Truth(追寻一段永世难忘的史实)24. Killer on Wings is Under Threat(飞翔的杀手正受到威胁)25. Life in a Violin Case(琴匣子中的生趣)26. Love Is Not like Merchandise(爱情不是商品)27. Luck(好运气)28. Mayhew(生活的道路)29. My Averae Uncle(艾默大叔——一个普普通通的人)30. My Father‘s Music(我父亲的音乐)31. My Mother‘s Gift (母亲的礼物)32. New Light Buld Offers Energy Efficiency(新型灯泡提高能效)33. Of Studies(谈读书)34. On Leadership(论领导)35. On Cottages in General(农舍概述)36. Over the Hill(开小差)37. Promise of Bluebirds(蓝知更鸟的希望)38. Stories on a Headboard(床头板上故事多)39. Sunday(星期天)40. The Blanket(一条毛毯)41. The Colour of the Sky(天空的色彩)42. The date Father Didn‘t Keep(父亲失约)43. The Kiss(吻)44. The Letter(家书)45. The Little Boat That Sailed through Time(悠悠岁月小船情)46. The Living Seas(富有生命的海洋)47. The Roots of My Ambition(我的自强之源)48. The song of the River(河之歌)49. They Wanted Him Everywhere——Herbert von Karajan(1908-1989) (哪儿都要他)50. Three Great Puffy Rolls(三个又大双暄的面包圈)51. Trust(信任)52. Why measure Life in Hearbeats? (何必以心跳定生死?)53. Why the bones Break(骨折缘何而起)54. Why Women Live Longer than Men(为什么女人经男人活得长)丑石贾平凹我常常遗憾我家门前的那块丑石呢:它黑黝黝地卧在那里,牛似的模样;谁也不知道是什么时候留在这里的.谁也不去理会它。

上海外国语大学考研散文翻译

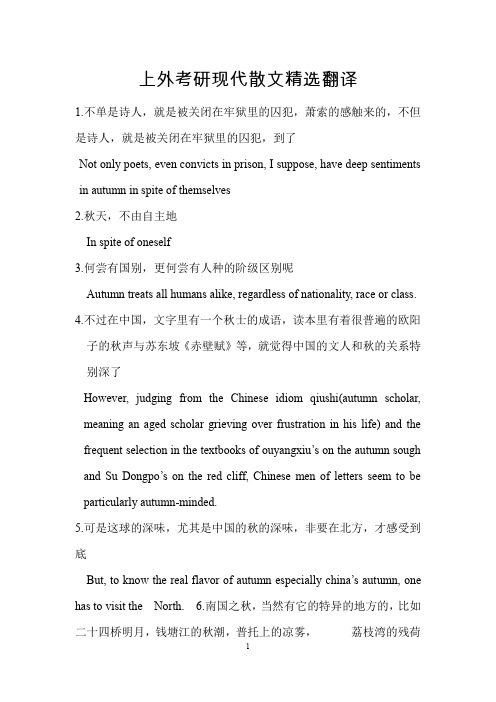

上外考研现代散文精选翻译1.不单是诗人,就是被关闭在牢狱里的囚犯,萧索的感触来的,不但是诗人,就是被关闭在牢狱里的囚犯,到了Not only poets, even convicts in prison, I suppose, have deep sentiments in autumn in spite of themselves2.秋天,不由自主地In spite of oneself3.何尝有国别,更何尝有人种的阶级区别呢Autumn treats all humans alike, regardless of nationality, race or class.4.不过在中国,文字里有一个秋士的成语,读本里有着很普遍的欧阳子的秋声与苏东坡《赤壁赋》等,就觉得中国的文人和秋的关系特别深了However, judging from the Chinese idiom qiushi(autumn scholar, meaning an aged scholar grieving over frustration in his life) and the frequent selection in the textbooks of ouyangxiu’s on the autumn sough and Su Dongpo’s on the red cliff, Chinese men of letters seem to be particularly autumn-minded.5.可是这球的深味,尤其是中国的秋的深味,非要在北方,才感受到底But, to know the real flavor of autumn especially china’s aut umn, one has to visit the North. 6.南国之秋,当然有它的特异的地方的,比如二十四桥明月,钱塘江的秋潮,普托上的凉雾,荔枝湾的残荷等等Autumn in the south also has its unique feature such as the moon-lit Ershisi bridge in Yangzhou, the flowing sea tide at Qiantangjiang River, the mist-shrouded Putuo mountain and lotuses at the Lizhiwan Bay.7.可是色彩不浓,回味不永。

古代散文选修重点文句翻译

古文选修重点译文1. 方今之时,臣以神遇而不以目视,官知止而神欲行。

【译文】现在,我只用精神和牛接触,而不用眼睛去看,视觉停止了而精神还在活动。

2. 依乎天理,批大郤,导大窾,因其固然,技经肯綮之未尝,而况大軱乎!【译文】依照天然结构,击入牛体大的缝隙,顺着(骨节间的)空处进刀,依照牛体本来的构造,从未(触碰)脉络相连和筋骨结合的地方,更何况大骨呢!3. 虽然,每至于族,吾见其难为,怵然为戒,视为止,行为迟。

【译文】虽然这样,每当碰到(筋骨)交错聚结的地方,我看到那里很难下刀,就小心翼翼地提高警惕,视力因为它集中到一点,动作也因此缓慢下来。

4. 彼节者有间,而刀刃者无厚;以无厚入有间,恢恢乎其于游刃必有余地矣.【译文】那牛的骨节有间隙,而刀刃很薄;用很薄的(刀刃)插入有空隙的(骨节),宽宽绰绰地,对刀刃的运转必然是有余地的啊!5. 提刀而立,为之四顾,为之踌躇满志,善刀而藏之【译文】(我)提着刀站立起来,为此举目四望,为此心满意足,(然后)把刀擦抹干净,收藏起来。

6.所当者破,所击者服,未尝败北,遂霸有天下。

【译文】我所抵挡的敌人都被打垮,我所攻击的敌人无不降服,从来没有失败过,因而能够称霸据有天下。

7.然今卒困于此,此天之亡我,非战之罪也。

【译文】然而今天却终于被困在这里,这是上天要我灭亡,不是战争的过错啊。

8. 纵江东父兄怜而王我,我何面目见之?纵彼不言,籍独不愧于心乎?【译文】即使江东的父老兄弟怜爱我而让我做王,我又有什么脸面见他们呢?纵使他们不说,我难道不感到内心有愧吗?9. 今日固决死,愿为诸君快战,必三胜之,为诸君溃围,斩将,刈旗。

【译文】今天本来就要决心战死了,我愿意给诸位痛痛快快地打一仗,一定胜它三回,给诸位冲破重围,斩杀汉将,砍倒汉军旗臶。

10. 项王瞋目而叱之,赤泉侯人马俱惊,辟易数里。

【译文】项王瞪大眼睛呵叱他,赤泉侯连人带马都吓坏了,倒退了好几里。

11. 天之亡我,我何渡为!【译文】(既然)上天要灭亡我,我还渡乌江干什么!12. 13. 吾闻汉购我头千金,邑万户,吾为若德。

(完整word版)文学散文翻译

品味散文My Bookby George Robert Gissing (1857—1903)Dozens of my books were purchased with money which ought to have been spent upon what are called necessities of life. Many a time I have stood before a stall, or a bookseller's window, torn by conflict of intellectual desire and bodily need。

At the very hour of dinner, when my stomach clamored or food, I have been stopped by sight of a volume so long coveted, and marked at so advantageous a price, that I could not let it go: yet to buy it meant pangs of famine。

My Heyne’s Tibullus was grasped at such a moment. It lay on the stall of the old book —shop in Goodge Street —— a stall where now and then one found an excellent thing among quantities of rubbish.Sixpence was the price —— sixpence! At that time I used to eat my midday meal (of course, my dinner) at a coffee-shop, such as now, I suppose, can hardly be found。

高二年语文部分古代散文译文及知识点

高二年语文部分古代散文译文及知识点----7535d69c-7166-11ec-b570-7cb59b590d7d阿房宫赋译文六国被毁,世界统一。

四川山林中的树木被砍伐,并修建了一座芳宫。

它覆盖了300多英里,几乎覆盖了天空和太阳。

它从骊山以北开始,向西呈之字形延伸至咸阳。

渭水和繁川流入宫墙。

五级高楼和十级凉亭;走廊像一条腰带,蜿蜒曲折,屋檐高耸,像鸟喙一样在空中啄食。

这些亭台楼阁被不同的地形包围,回廊被钩子包围,飞檐高耸如角。

迂回曲折,迂回曲折,像蜂巢一样密集,像漩涡一样相连,高耸。

我不知道有几千万。

长桥在水上(像一条龙),但没有云,龙怎么能翱翔?两个展馆之间的复合道路处于半空中(像彩虹),但雨后并不晴朗。

怎么会有彩虹?高楼大厦和低楼大厦模糊不清,使人们无法区分南北、东西。

人们在舞台上唱歌,音乐听起来好像充满了温暖,像春天一样温暖;人们在大厅里翩翩起舞,袖子飘动,仿佛它带来了寒冷,像风雨一样凄凉。

同一天,在同一座宫殿里,气候非常不同。

(六国的)宫女妃嫔、诸侯王族的女儿孙女,辞别了故国的宫殿阁楼,乘坐辇车来到秦国。

(她们)早晚吹拉弹唱,成为秦皇的宫人。

(清晨)只见星光闪烁,(原来是她们)打开了梳妆的明镜;又见乌云纷纷扰扰,(原来是她们)一早在梳理发鬓;渭水泛起一层油腻,(是她们)泼下的脂粉水呀;轻烟缭绕,香雾弥漫,是她们焚烧的椒兰异香。

忽然雷霆般的响声震天,(原来是)宫车从这里驰过;辘辘的车轮声渐听渐远,不知它驶向何方。

(宫女们)极力显示自己的妩媚娇妍,每一处肌肤,每一种姿态,都极为动人。

(她们)久久地伫立着,眺望着,希望皇帝能宠幸光临;(可怜)有的人三十六年始终未曾见过皇帝的身影。

燕国、赵国收藏的珍宝,朝鲜国、魏国收藏的金银,以及齐国、楚国保存的珍宝,都被掠夺了多年,世代相传。

一旦国家被摧毁,无法再被占领,他们就会被送往阿芳宫。

从那时起,保定被认为是铁锅、宝玉石、金土块、珍珠(被认为是)砾石到处乱扔,秦人并不十分珍惜它们。

高级阅读散文中文翻译

高级阅读散文中文翻译重返湖畔 E.B.怀特那年夏天,一九零四年左右吧,我父亲在缅因州某个湖畔租了一处营地,带全家去那里度过了八月。

我们全都因为几只猫而传染上了癣症,不得不早晚往胳膊和腿上涂旁氏浸膏,我父亲则和衣睡在小划子里;但除此之外,那个假期过得很好,从那时起,我们就都认为缅因州的那个湖是世上独一无二的地方。

我们年复一年去消夏,总是八月一日去,过上一个月。

后来,我就成了个水手,但是在夏季的某些日子,潮汐的涨落、海水那令人生畏的冰凉还有从下午一直吹到晚上的风,让我向往起林间湖泊的那种宁静。

几周前,这种感觉变得如此强烈,以至于我买了一对钓鲈鱼的鱼钩和一个旋式鱼饵,又回到我们以前常去的那个湖钓了一周的鱼,算是一次旧地重游吧。

我带上了儿子,他从未亲近过湖水,只是从火车窗口里看到过荷花。

在去湖边的路上,我开始想象它会是什么样,想知道时光会怎样损害这个独特的神圣地点??小湾,溪流,太阳落下的山谷,营房和它后面的小路。

我确信能找到那条柏油路,但是想知道它会以别的什么方式荒凉着。

奇怪的是,一旦让自己的思路回到通往过去的老路上,关于老地方,能记起那么多事。

你记起了一件事,突然又想到另外一件事。

我想我记得最清楚的是清晨,当时湖水清凉,水波不兴。

还记起卧室里有建房所用圆木的味道,还有透过纱窗的潮湿树林的味道。

营房的隔板不厚,而且没有一直接到房顶,由于我总是第一个起床,我会悄悄穿好衣服,以免吵醒其他人,然后溜到宜人的户外,驾起一只小划子,一直紧挨着岸边在松树长长的树影下航行。

我记得我非常小心,从来没把桨擦着舷边划,怕的是打扰那种教堂般的宁静。

那个湖从来不该被称为渺无人迹的。

湖畔上零星点缀着一处处小屋,这个湖位于以农为业的乡村,然而湖畔林木颇为繁茂。

有些小屋为附近的农人所有,你可以住在湖畔,在农舍用餐,我们家就是那么做的。

尽管不算偏僻,它仍是一个相当大、相当宁静的湖,其中有些地方至少在小孩看来,似乎无穷遥远和原始。

关于柏油路我猜对了:它一直通到离湖畔半英里的地方,但是当我带着儿子回到那里,当我们在一座农舍附近的小屋里安顿下来,进入我所了解的那种夏季时,我可以说它与旧日了无差别。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

●● 2 How to Grow Old[A]1. Did all Russell's ancestors live to a ripe old age?No, they didn't. His maternal grandfather died at 67 and one of his remoter ancestors did not die a natural death.2.How did his maternal grandmother keep herself occupied after she became a widow? What was her attitude towards her grandchildren?She did that by devoting herself to women's higher education, specifically to opening the medical profession to women. Her attitude towards her grandchildren was impersonal.3. According to the author, what is the proper recipe for remaining young?To have wide and keen interests and to be engaged in some related activities.4. What dangers does the author think one should guard against in old age?One is excessive absorption in the past, and the other is undue dependence on the young for getting vigour from its vitality.5. What attitude should be adopted towards one's grown-up children?Accepting the fact that they are grown-ups now and leave them to live their own lives.6. Why is it no use telling grown-up children not to make mistakes?One reason is that grown-up children do not accept what their parents tell them.The other reason is that no one can avoid making mistakes. So we may say that everyone learns from his own mistakes.7. What, in the opinion of the author, is the best way for an old person to overcome the fear of death?The best way is to make one's interests gradually wider and more impersonal, or to make one's life increasingly merged in the universal life.[B]1. Do you agree with the author's views on old age and death? State your reasons.Yes. An active and independent old age is good way to keep young..2. What does the author compare the life of an individual to?A river.3. Are the author's views in this essay to be taken seriously through out?Not through out. The author was joking when he said that one should choose one's ancestors carefully.4. Comment on the sentence 'Young men who have reason to fear that they will be killed in battle may justifiably feel bitter in the thought that they have been cheated of the best things that life has to offer.'The author means that the fear of death in young people may be justified because they have not tasted the best things of life.On the other hand, the author is suggesting that the fear of death in the old is not as acceptable - because he has known human joys and sorrows.We may further say that the author is urging the old to accept the fact of human life, that man has a limited lifetime. So if one has had his share of human joys and sorrows, one should be ready to accept that fact he is near the end of his life.II Paraphrasing1. If this is true it should be forgotten, and if it is forgotten it will probably not be true.If it is true that one's emotions used to be more vivid and one's mind used to be more keen, one should try to forget that. And if one can really forget that, who can say for certain that one is older or lower than one used to be.2. One's interest should be contemplative and, if possible, philanthropic, but not unduly emotional.One should have impersonal interests and one should not concern oneself too much with one's children and grandchildren.3. It is in this sphere that long experience is really fruitful, and it is in this sphere that the wisdom born of experience can be exercised without being oppressive."this sphere" refers to "appropriate activities"Only in appropriate activities is long experience helpful and is the wisdom brought by experience useful - otherwise it is unbearable.●●5 As I see it[A]1. What do you think made Shaw give this radio talk in 1937?To urge the British people to be conscientious objectors of war and to make them realize that to be a pacifist in the present war is not the right attitude and that the British should change the distribution system in order to avoid the most dangerous war between Capitalism and Communism.2. What was happening in Spain and China?Spain and China were both at war at that time. Japan invaded China and Spain was in a civil war.3. Are the horrors of war as described by Shaw real or imaginary?Some are real and some are imaginary. The description of the street scenes was real in Spain and China, but in 1937 London or Paris were not yet in the danger of being bombed by any enemy country.4. Why did Shaw hate war?Because of the loss of human lives on both side at war - besides the dangers of war.5. Did Shaw give his whole-hearted support to the pacifist movement against war?No, he thought at that moment the pacifist movement was a wrong movement. Because Mussolini and Hitler did not let others live, so people should not tolerate them and must fight against them.6. What kind of war did Shaw think would put an end to civilization?The war between Capitalism and Communism, or between landowning and labour.7. What was wrong with Britain according to Shaw?Its distribution system is unfair and unjust and its people are not any taking actions to change the situation - they only keep talking about it.8. Was Shaw optimistic? Or did he end his speech on a note of despair?No, he was not optimistic and there is a note of despair when he came to the end of his speech. As he said, "nobody takes any notice" of what he had said.[B] 1. What are conscientious objectors?(出于道德或宗教上的原因而)拒绝服兵役的人,不积极参与任何有关战争行动的人。