Alice Walker

Alice Walker

Alice Walker艾丽丝·沃克(Alice Walker,1944—)是20世纪70年代以来(欧美国家第二次妇女运动之后)美国文坛最著名的黑人女作家之一。

她在她的小说里生动的反映了黑人女性的苦难,歌颂了她们与逆境搏斗的精神和奋发自立的坚强性格。

为了区别于其它女权主义者,她提出了“妇女主义”(Womanism)这一独特的思想概念。

如果说妇女主义是理论,她的长篇小说《紫色》(The Color Purple)便是对这一理论的具体实践。

《紫色》自1982年发表以来,便轰动美国文坛,接连获得了美国文学作品的三个大奖:普利策奖、全国图书奖和全国书评家奖。

艾丽丝·沃克成为获得普立策奖的第一个黑人女作家。

艾丽斯·沃克1944年2月9日出生于南方佐治亚州的一个佃农家庭,父母的祖先是奴隶和印度安人,艾丽斯是家里八个孩子中最小的一个。

艾丽斯8岁时,在和哥哥们玩“牛仔与印度安人”的游戏时被玩具枪射瞎了右眼。

1961年艾丽斯获奖学金入亚特兰大的斯帕尔曼大学学习,正赶上美国民权运动的高涨时期,她即投身于这场争取种族平等的政治运动。

1962年,艾丽斯·沃克被邀请到马丁·路德·金的家里做客。

1963年艾丽斯到华盛顿参加了那次著名的游行,与万千黑人一同聆听马丁·路德·金“我有一个梦想”的讲演。

艾丽斯大学毕业前在东非旅行时怀孕,当时流产仍属非法,她经历了一段想要自杀的痛苦时期,同时也写下了一些诗歌。

1965年艾丽斯大学毕业后回到了当时是民权运动中心的南方老家继续参加争取黑人选举权的运动。

在活动中艾丽斯遇上了犹太人列文斯尔,俩人克服跨种族婚姻的重重困难结为“革命伴侣”,艾丽斯再一次怀孕,但不幸的是在参加马丁·路德·金的葬礼时因悲伤而痛失孩子。

在列文斯尔的鼓励下,艾丽斯继续写作并先后发表了诗集《一度》(Once,1968)和小说《格兰奇·科普兰的第三次生命》(The Third Life of GrangeCopeland,1970)。

Alice Walker简介

2016/12/8

18

The Pulitzer Prize for Fiction is one of the seven American Pulitzer Prizes that are annually awarded for Letters, Drama, and Music. It recognizes distinguished fiction by an American author, preferably dealing with American life, published during the preceding calendar year. 2016/12/8

19

The National Book Awards are a set of annual U.S. literary awards. At the final National Book Awards Ceremony every November, the National Book Foundation presents the National Book Awards and two lifetime achievement awards to authors.

2016/12/8 3

2016/12/8

4

Introduction Writing career Selected Awards and Honors The Color Purple

2016/12/8 5

Born:February 9, 1944 (age 72) Putnam County, Georgia, U.S.

• • • • • • • • • • • •

1988 — Living by the Word 1989 — The Temple of My Familiar 1991 — Her Blue Body Everything We Know: Earthling Poems 1965-1990 Complete 1991 — Finding the Green Stone 1992 — Possessing the Secret of Joy 1993 — Warrior Marks 1996 — Alice Walker: Banned 1996 — The Same River Twice: Honoring the Difficult 1997 — Anything We Love Can Be Saved: A Writer's Activism 1998 — By the Light of My Father's Smile 2000 — The Way Forward Is with a Broken Heart

爱丽丝·沃克小说创作中的“非洲中心主义”

爱丽丝·沃克小说创作中的“非洲中心主义”摘要“非洲中心主义”思想代表着一种“非洲意识”的苏醒,尝试站在非洲人的位置并使用他们的视角看待和解决问题,它的出现是对原有“欧洲中心主义”思想的绝对统治地位的一次有力冲击。

非裔女性作家爱丽丝·沃克致力于描写非裔群体生活的悲欢离合。

其创作与“非洲中心主义”有深刻的联系:“非洲中心主义”是爱丽丝表达政治理念的重要概念,而她的创作也进一步丰富了美国非裔“非洲中心主义”理论话语体系。

学术界对于爱丽丝·沃克的讨论多集中在女性主义角度,但在对沃克作品的梳理过程中,我们可以清晰地看见“非洲中心主义”理论的痕迹。

本文在对爱丽丝·沃克与“非洲中心主义”相遇与接受进行考察的基础上,阐述其作品对“非洲中心主义”的文学表达。

论文包含绪论、正文与结语三个部分。

绪论介绍爱丽丝·沃克的文学创作情况、国内外研究现状以及研究思路。

其次,正文共分为四个章节,第一章关注“非洲中心主义”理论的诞生及特征,梳理其在非洲形成的详细过程以及后期在美国的发展情况,并结合沃克的访谈和文章探究沃克思考下的“非洲中心主义”的内涵。

沃克借“妇女主义”思想呼吁:以黑人在非洲大陆的根为骄傲,不能忘记民族的历史。

她建议艺术家们将优秀的非洲传统文化遗产同各式的艺术结合并将其传承下去,并肯定了具有生命力和惊人创造力的“黑人美”。

第二章分析沃克的“民俗性”与“黑人美”题材实践,分别阐述了民间口述故事、黑人医药与手工艺术的特色民俗价值,点明了黑人女性“生活艺术家”与“民权抗争者”的身份,也歌颂了老一辈黑人善良勤劳的本性。

第三章着重于讲述如何用“非洲中心主义”思想这一良方,救治遭受白人信仰精神毒害的非裔群体。

沃克用源于非洲传统的“泛灵论”改革了基督教思想,并重铸经典以此帮助非裔群体重拾信心。

她通过实践将上帝形象归于自然与母亲,还关注了独具黑人文化特色的伏都教法术。

最后一章从蓝调这一黑人叙事形式角度出发,阐述沃克作品中的布鲁斯特征。

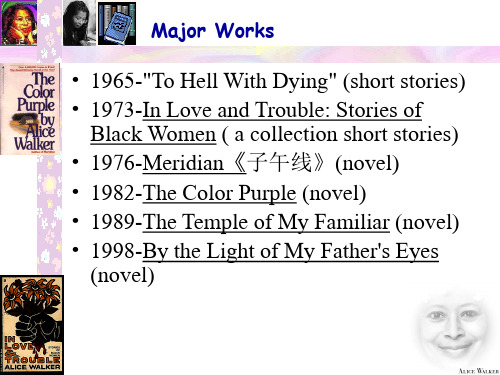

Alice Walker作品简介

• 1965-"To Hell With Dying" (short stories) • 1973-In Love and Trouble: Stories of Black Women ( a collection short stories) • 1976-Meridian《子午线》(novel) • 1982-The Color Purple (novel) • 1989-The Temple of My Familiar (novel) • 1998-By the Light of My Father's Eyes (novel)

• It is a short story in In love and Trouble and remains a cornerstone of her work. Her use of quilting as a metaphor for the creative legacy that African Americans inherited from their maternal ancestors changed the way we defined art, women's culture, and African American lives. By putting African American women's voices at the center of the narrative for the first time, "Everyday Use" anticipated the focus of an entire generation of black women writers. This casebook includes an introduction by the editor, a chronology of Walker's life, authoritative texts of "Everyday Use" and "In Search of Our Mothers' Gardens," an interview with Walker, six critical essays, and a bibliography.

Alice Walker

Alice WalkerFrom Wikipedia, the free encyclopediaAlice Malsenior Walker(born February 9, 1944) is an American author and activist. She wrote the critically acclaimed novel The Color Purple(1982) for which she won the National Book Awardand the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction.爱丽丝沃克英文摘录自维基百科,自由的百科全书,罗金佑翻译爱丽丝.马尔瑟尼奥.沃克(Alice Malsenior Walker出生于1944年2月9日)是一位美国作家和活动家。

她写的广受好评的小说《紫色》(1982)为她赢得了国家图书奖和普利策小说奖。

Early lifeWalker was born in Putnam County, Georgia,the youngest of eight children, to Willie Lee Walker and Minnie Lou Tallulah Grant. Her father, who was, in her words, "wonderful at math but a terrible farmer," earned only $300 ($4,000 in 2013 dollars) a year from sharecroppingand dairy farming. Her mother supplemented the family income by working as a maid. She worked 11 hours a day for $17 per week to help pay for Alice to attend college.早期的生活沃克是出生在乔治亚州普特南县,是威利.里.沃克和米妮.楼.塔露拉.格兰特的八个孩子中最小的一位。

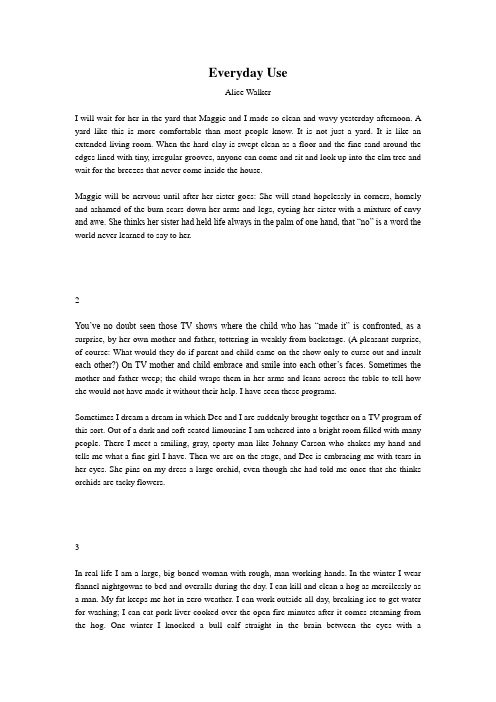

Everyday Use-Alice Walker(《祖母的日常用品》爱丽丝.沃克)原版辅导教学问题

Everyday UseAlice WalkerI will wait for her in the yard that Maggie and I made so clean and wavy yesterday afternoon. A yard like this is more comfortable than most people know. It is not just a yard. It is like an extended living room. When the hard clay is swept clean as a floor and the fine sand around the edges lined with tiny, irregular grooves, anyone can come and sit and look up into the elm tree and wait for the breezes that never come inside the house.Maggie will be nervous until after her sister goes: She will stand hopelessly in corners, homely and ashamed of the burn scars down her arms and legs, eyeing her sister with a mixture of envy and awe. She thinks her sister had held life always in the palm of one hand, that “no” is a word the world never learned to say to her.--------------------------------------------------------------------------------2You’ve no doubt seen those TV shows where the child who has “made it” is confronted, as a surprise, by her own mother and father, tottering in weakly from backstage. (A pleasant surprise, of course: What would they do if parent and child came on the show only to curse out and insult each other?) On TV mother and child embrace and smile into each other’s faces. Sometimes the mother and father weep; the child wraps them in her arms and leans across the table to tell how she would not have made it without their help. I have seen these programs.Sometimes I dream a dream in which Dee and I are suddenly brought together on a TV program of this sort. Out of a dark and soft-seated limousine I am ushered into a bright room filled with many people. There I meet a smiling, gray, sporty man like Johnny Carson who shakes my hand and tells me what a fine girl I have. Then we are on the stage, and Dee is embracing me with tears in her eyes. She pins on my dress a large orchid, even though she had told me once that she thinks orchids are tacky flowers.--------------------------------------------------------------------------------3In real life I am a large, big-boned woman with rough, man-working hands. In the winter I wear flannel nightgowns to bed and overalls during the day. I can kill and clean a hog as mercilessly as a man. My fat keeps me hot in zero weather. I can work outside all day, breaking ice to get water for washing; I can eat pork liver cooked over the open fire minutes after it comes steaming from the hog. One winter I knocked a bull calf straight in the brain between the eyes with asledgehammer and had the meat hung up to chill before nightfall. But of course all this does not show on television. I am the way my daughter would want me to be: a hundred pounds lighter, my skin like an uncooked barley pancake. My hair glistens in the hot bright lights. Johnny Carson has much to do to keep up with my quick and witty tongue.But that is a mistake. I know even before I wake up. Who ever knew a Johnson with a quick tongue? Who can even imagine me looking a strange white man in the eye? It seems to me I have talked to them always with one foot raised in flight, with my head turned in whichever way is farthest from them. Dee, though. She would always look anyone in the eye. Hesitation was no part of her nature.--------------------------------------------------------------------------------4“How do I look, Mama?” Maggie says, showing just enough of her thin body enveloped in pink skirt and red blouse for me to know she’s there, almost hidden by the door.“Come out into the yard,” I say.Have you ever seen a lame animal, perhaps a dog run over by some careless person rich enough to own a car, sidle up to someone who is ignorant enough to be kind to him? That is the way my Maggie walks. She has been like this, chin on chest, eyes on ground, feet in shuffle, ever since the fire that burned the other house to the ground.Dee is lighter than Maggie, with nicer hair and a fuller figure. She’s a woman now, though sometimes I forget. How long ago was it that the other house burned? Ten, twelve years? Sometimes I can still hear the flames and feel Maggie’s arms sticking to me, her hair smoking and her dress falling off her in little black papery flakes. Her eyes seemed stretched open, blazed open by the flames reflected in them. And Dee. I see her standing off under the sweet gum tree she used to dig gum out of, a look of concentration on her face as she watched the last dingy gray board of the house fall in toward the red-hot brick chimney. Why don’t you do a dance around the ashes? I’d wanted to ask her. She had hated the house that much.--------------------------------------------------------------------------------5I used to think she hated Maggie, too. But that was before we raised the money, the church and me, to send her to Augusta to school. She used to read to us without pity, forcing words, lies, otherfolks’ habits, whole lives upon us two, sitting trapped and ignorant underneath her voice. She washed us in a river of make-believe, burned us with a lot of knowledge we didn’t necessarily need to know. Pressed us to her with the serious ways she read, to shove us away at just the moment, like dimwits, we seemed about to understand.Dee wanted nice things. A yellow organdy dress to wear to her graduation from high school; black pumps to match a green suit she’d made from an ol d suit somebody gave me. She was determined to stare down any disaster in her efforts. Her eyelids would not flicker for minutes at a time. Often I fought off the temptation to shake her. At sixteen she had a style of her own: and knew what style was.6I never had an education myself. After second grade the school closed down. Don’t ask me why: In 1927 colored asked fewer questions than they do now. Sometimes Maggie reads to me. She stumbles along good-naturedly but can’t see well. She knows she is not bright. Like good looks and money, quickness passed her by. She will marry John Thomas (who has mossy teeth in an earnest face), and then I’ll be free to sit here and I guess just sing church songs to myself. Although I never was a good singer. Never could carry a tune. I was always better at a man’s job. I used to love to milk till I was hooked in the side in ’49. Cows are soothing and slow and don’t bother you, unless you try to milk them the wrong way.I have deliberately turned my back on the house. It is three rooms, just like the one that burned, except the roof is tin; they don’t make shingle roofs anymore. There are no real windows, just some holes cut in the sides, like the port-holes in a ship, but not round and not square, with rawhide holding the shutters up on the outside. This house is in a pasture, too, like the other one. No doubt when Dee sees it she will want to tear it down. She wrote me once that no matter where we “choose” to live, she will manage to come see us. But she will never bri ng her friends. Maggie and I thought about this and Maggie asked me, “Mama, when did Dee ever have any friends?”--------------------------------------------------------------------------------7She had a few. Furtive boys in pink shirts hanging about on washday after school. Nervous girls who never laughed. Impressed with her, they worshiped the well-turned phrase, the cute shape, the scalding humor that erupted like bubbles in lye. She read to them.When she was courting Jimmy T, she didn’t have much time to pay to us but turned all her faultfinding power on him. He flew to marry a cheap city girl from a family of ignorant, flashy people. She hardly had time to recompose herself.When she comes, I will meet—but there they are!Maggie attempts to make a dash for the house, in her shuffling way, but I stay her with my hand. “Come back here,” I say. And she stops and tries to dig a well in the sand with her toe.It is hard to see them clearly through the strong sun. But even the first glimpse of leg out of the car tells me it is Dee. Her feet were always neat looking, as if God himself shaped them with a certain style. From the other side of the car comes a short, stocky man. Hair is all over his head a foot long and hanging from his chin like a kinky mule tail. I hear Maggie suck in her breath. “Uhnnnh” is what it sounds like. Like when you see the wriggling end of a snake just in front of your foot on the road. “Uhnnnh.”--------------------------------------------------------------------------------8Dee next. A dress down to the ground, in this hot weather. A dress so loud it hurts my eyes. There are yellows and oranges enough to throw back the light of the sun. I feel my whole face warming from the heat waves it throws out. Earrings gold, too, and hanging down to her shoulders. Bracelets dangling and making noises when she moves her arm up to shake the folds of the dress out of her armpits. The dress is loose and flows, and as she walks closer, I like it. I hear Maggie go “Uhnnnh” again. It is her sister’s hair. It stands straight up like the wool on a sheep. It is black as night and around the edges are two long pigtails that rope about like small lizards disappearing behind her ears.“Wa-su-zo-Tean-o!” she says, coming on in that g liding way the dress makes her move. The short, stocky fellow with the hair to his navel is all grinning, and he follows up with “Asalamalakim,1 my mother and sister!” He moves to hug Maggie but she falls back, right up against the back of my chair. I feel her trembling there, and when I look up I see the perspiration falling off her chin.--------------------------------------------------------------------------------9“Don’t get up,” says Dee. Since I am stout, it takes something of a push. You can see me trying to move a second or two before I make it. She turns, showing white heels through her sandals, andgoes back to the car. Out she peeks next with a Polaroid. She stoops down quickly and lines up picture after picture of me sitting there in front of the house with Maggie cowering behind me. She never takes a shot without making sure the house is included. When a cow comes nibbling around in the edge of the yard, she snaps it and me and Maggie and the house. Then she puts the Polaroid in the back seat of the car and comes up and kisses me on the forehead.Meanwhile, Asalamalakim is going through motions with Maggie’s hand. Maggie’s hand is as limp as a fish, and probably as cold, despite the sweat, and she keeps trying to pull it back. It looks like Asalamalakim wants to shake hands but wants to do it fancy. Or maybe he don’t know how people shake hands. Anyhow, he soon gives up on Maggie.“Well,” I say. “Dee.”“No, Mama,” she says. “Not ‘Dee,’ Wangero Leewanika Kemanjo!”--------------------------------------------------------------------------------10“What happened to ‘Dee’?” I wanted to know.“She’s dead,” Wangero said. “I couldn’t bear it any longer, being named after the people who oppress me.”“You know as well as me you w as named after your aunt Dicie,” I said. Dicie is my sister. She named Dee. We called her “Big Dee” after Dee was born.“But who was she named after?” asked Wangero.“I guess after Grandma Dee,” I said.“And who was she named after?” asked Wangero.“Her mother,” I said, and saw Wangero was getting tired. “That’s about as far back as I can traceit,” I said. Though, in fact, I probably could have carried it back beyond the Civil War through the branches.“Well,” said Asalamalakim, “there you are.”“Uhnnnh,” I heard Maggie say.11“There I was not,” I said, “before ‘Dicie’ cropped up in our family, so why should I try to trace it that far back?”He just stood there grinning, looking down on me like somebody inspecting a Model A car. Every once in a while he and Wangero sent eye signals over my head.“How do you pronounce this name?” I asked.“You don’t have to call me by it if you don’t want to,” said Wangero.“Why shouldn’t I?” I asked. “If that’s what you want us to call you, we’ll call you.”“I know it might sound awkward at first,” said Wangero.“I’ll get used to it,” I said. “Ream it out again.”Well, soon we got the name out of the way. Asalamalakim had a name twice as long and three times as hard. After I tripped over it two or three times, he told me to just call him Hakim-a-barber.I wanted to ask him was he a barber, but I didn’t really think he was, so I didn’t ask.--------------------------------------------------------------------------------12“You must belong to those beef-cattle peoples down the road,” I said. They said “Asalamalakim”when they met you, too, but they didn’t shake hands. Always too busy: feeding the cattle, fixing the fences, putting up salt-lick shelters, throwing down hay. When the white folks poisoned some of the herd, the men stayed up all night with rifles in their hands. I walked a mile and a half just to see the sight.Hakim-a-barber said, “I accept some of their doctrines, but farming and raising cattle is not my style.” (They didn’t tell me, and I didn’t ask, whether Wangero—Dee—had really gone and married him.)We sat down to eat and right away he said he didn’t eat collards, and pork was unclean. Wangero, though, went on through the chitlins and corn bread, the greens, and everything else. She talked a blue streak over the sweet potatoes. Everything delighted her. Even the fact that we still used the benches her daddy made for the table when we couldn’t afford to buy chairs.--------------------------------------------------------------------------------13“Oh, Mama!” she cried. Then turned to Hakim-a-barber. “I never knew how lovely these benches are. You can feel the rump prints,” she said, running her hands underneath her and along the bench. Then she gave a sigh, and her hand closed over Grandma Dee’s butter dish. “That’s it!” she said. “I knew there was something I wanted to ask you if I could have.” She jumped up from the table and went over in the corner where the churn stood, the milk in it clabber2 by now. She looked at the churn and looked at it.“This churn top is what I need,” she said. “Didn’t Uncle Buddy whittle it out of a tree you all used to have?”“Yes,” I said.“Uh huh,” she said happily. “And I want the dasher,3 too.”“Uncle Buddy whittle that, too?” asked the barber.Dee (Wangero) looked up at me.“Aunt Dee’s first husband whittled the dash,” said Maggie so low you almost couldn’t hear her.“His name was Henry, but they called him Stash.”--------------------------------------------------------------------------------14“Maggie’s brain is like an elephant’s,” Wangero said, laughing. “I can use the churn top as a centerpiece for the alcove table,” she said, sliding a plate over the churn, “and I’ll think of something artistic to do with the dasher.”When she finished wrapping the dasher, the handle stuck out. I took it for a moment in my hands. You didn’t even have to look close to see where hands pushing the dasher up and down to make butter had left a kind of sink in the wood. In fact, there were a lot of small sinks; you could see where thumbs and fingers had sunk into the wood. It was beautiful light-yellow wood, from a tree that grew in the yard where Big Dee and Stash had lived.After dinner Dee (Wangero) went to the trunk at the foot of my bed and started rifling through it. Maggie hung back in the kitchen over the dishpan. Out came Wangero with two quilts. They had been pieced by Grandma Dee, and then Big Dee and me had hung them on the quilt frames on the front porch and quilted them. One was in the Lone Star pattern. The other was Walk Around the Mountain. In both of them were scraps of dresses Grandma Dee had worn fifty and more years ago. Bits and pieces of Grandpa Jarrell’s paisley shirts. And one teeny faded blue piece, about the size of a penny matchbox, that was from Great Grandpa Ezra’s uniform that he wore in the Civil War.--------------------------------------------------------------------------------15“Mama,” Wangero said sweet as a bird. “Can I have these old quilts?”I heard something fall in the kitchen, and a minute later the kitchen door slammed.“Why don’t you take one or two of the others?” I asked. “These old things was just done by me and Big Dee from some tops your grandma pieced befor e she died.”“No,” said Wangero. “I don’t want those. They are stitched around the borders by machine.”“That’ll make them last better,” I said.“That’s not the point,” said Wangero. “These are all pieces of dresses Grandma used to wear. She did a ll this stitching by hand. Imagine!” She held the quilts securely in her arms, stroking them.16“Some of the pieces, like those lavender ones, come from old clothes her mother handed down to her,” I said, moving up to touch the quilts. Dee (Wangero) mo ved back just enough so that I couldn’t reach the quilts. They already belonged to her.“Imagine!” she breathed again, clutching them closely to her bosom.“The truth is,” I said, “I promised to give them quilts to Maggie, for when she marries John T homas.”She gasped like a bee had stung her.“Maggie can’t appreciate these quilts!” she said. “She’d probably be backward enough to put them to everyday use.”“I reckon she would,” I said. “God knows I been saving ’em for long enough with nobody using ’em. I hope she will!” I didn’t want to bring up how I had offered Dee (Wangero) a quilt when she went away to college. Then she had told me they were old-fashioned, out of style.--------------------------------------------------------------------------------17“But they’re priceless!” she was saying now, furiously; for she has a temper. “Maggie would put them on the bed and in five years they’d be in rags. Less than that!”“She can always make some more,” I said. “Maggie knows how to quilt.”D ee (Wangero) looked at me with hatred. “You just will not understand. The point is these quilts, these quilts!”“Well,” I said, stumped. “What would you do with them?”“Hang them,” she said. As if that was the only thing you could do with quilts.Maggie by now was standing in the door. I could almost hear the sound her feet made as they scraped over each other.“She can have them, Mama,” she said, like somebody used to never winning anything or having anything reserved for her. “I can ’member Grandma Dee without the quilts.”--------------------------------------------------------------------------------18I looked at her hard. She had filled her bottom lip with checkerberry snuff, and it gave her face a kind of dopey, hangdog look. It was Grandma Dee and Big Dee who taught her how to quilt herself. She stood there with her scarred hands hidden in the folds of her skirt. She looked at her sister with something like fear, but she wasn’t mad at her. This was Maggie’s portion. This was the way she knew God to work.When I looked at her like that, something hit me in the top of my head and ran down to the soles of my feet. Just like when I’m in church and the spirit of God touches me and I get happy and shout. I did something I never had done before: hugged Maggie to me, then dragged her on into the room, snatched the quilts out of Miss Wangero’s hands, and dumped them into Maggie’s lap. Maggie just sat there on my bed with her mouth open.“Take one or two of the others,” I said to Dee.But she turned without a word and went out to Hakim-a-barber.--------------------------------------------------------------------------------19“You just don’t understand,” she said, as Maggie and I came out to the car.“What don’t I understand?” I wanted to know.“Your heritage,” she said. And then she turned to Maggie, kissed her, and said, “You ought to try to make something of yourself, too, Maggie. It’s really a new day for us. But from the way you and Mama still live, you’d never know it.”She put on some sunglasses that hid everything above the tip of her nose and her chin.Maggie smiled, maybe at the sunglasses. But a real smile, not scared. After we watched the car dust settle, I asked Maggie to bring me a dip of snuff. And then the two of us sat there just enjoying, until it was time to go in the house and go to bed.--------------------------------------------------------------------------------Making MeaningsEveryday UseReading Checka. According to Mama, how is Dee different from her and from Maggie?b. How would Maggie and Dee use the quilts differently?c. When she was a child, something terrible happened to Maggie. What was it?d. How did the mother choose to resolve the conflict over the quilts?e. Find the passage in the text that explains the title .First Thoughts1. Which character did you side with in the conflict over the quilts, and why?Shaping Interpretations2. What do you think is the source of the conflict in this story? Consider:3. Dee is re ferred to as the child who has “made it.” What do you think that means, and what signs tell you that she has “made it”?4. Use a diagram like the one on the right to compare and contrast Dee and Maggie. What is themost significant thing they have in common? What is their most compelling difference?5. Near the end of the story, Dee accuses Mama of not understanding their African American heritage. Do you agree or disagree with Dee, and why?6. Has any character changed by the end of the story? Go back to the text and find details to support your answer.7. Why do you think Alice Walker dedicated her story “For Your Grandmama”?Extending the Text8. What do you think each of these three women will be doing ten years after the story ends?9. This story takes place in a very particular setting and a very particular culture. Talk about whether or not the problems faced by this family could be experienced by any family, anywhere.Challenging the Text10. Do you think Alice Walker chose the right narrator for her story? How would the story differ if Dee or Maggie were telling it, instead of Mama? (What would we know that we don’t know now?)来源网址:/books/Elements_of_Lit_Cours e4/Collection%201/Everyday%20Use%20p4.htm。

Alice-Walker作品简介只是分享

Feminist , feminism

《紫色》1983年一举拿下代表美国文学最 高荣誉的三大奖:普利策奖(Pulitzer Prize)、美国国家图书奖(The National Book Awards)、全国书评家协会奖 (NBCC Award)。

@@中国日报网站消息:美国 图书馆协会(ALA)日前公布研究 报告,黑人女作家艾丽丝·沃克 的小说《紫色》竟然与《哈 利·波特》、《魔戒》、《傲慢 与偏见》和莎士比亚戏剧一起, 成为被重读次数最多的文学作 品

3.此外,“紫色”除了象征生命的尊严和人类的希 望外, 紫色还是女同性恋主义的标志。书中对茜莉 和莎格·艾微利( Shug Avery) 的同性恋描写与严 格意义上的同性恋性关系是有区分的, 激进女权主 义者们声称, 女同性恋者实际上是自发的、“下意 识”的女权主义者,

---因此, 沃克大胆借用“紫色”为书 名,“把跪着的女性拉起来, 把她们提到 了王权的高度”, 让黑人妇女也享有帝 王般的尊严和社会地位。

Meridian is a heartfelt and moving story about one woman's personal revolution as she joins the Civil Rights Movement. Set in the American South in the 1960s it follows Meridian Hill, a courageous young woman who dedicates herself heart and soul to her civil rights work, touching the lives of those around her even as her own health begins to deteriorate. Hers is a lonely battle, but it is one she will not abandon, whatever the costs. This is classic Alice Walker, beautifully written, intense and passionate.

ALice-walker介绍

Biography

1. Alice Walker’s Early Life

Date of Birth: February 9, 1944 Birthplace: Eatonton, Georgia Parents: Willie Lee and Minnie Lou Grant Walker, who were sharecroppers<美>佃农 Marriage: (1967-1976)Mel Leventhal列文斯尔 a Jewish Civil Rights activist/ lawyer Child: Rebecca born in 1969

Alice walker

生平简介 主要作品

Main works

biography

作品思想

The themes of

her essays

所获奖项

Awards

课文主旨

作品思想 The themes of her essays

• Many of her novels depict (描述) women in other periods of history writing, such portrayals give a sense of the differences and similarities of women’s condition today and in that other time. Alice walker continues not only to write, but to be active in environmental, feminist causes, and issues of economic justice

Alice walker

Everyday Use for Grandma (Alice Walker)

At the start of the novel, Celie views God as completely separate from her world. She writes to God because she has no other way to express her feelings. Celie's writing to God thrusts her into a rich symbolic life which results in her repudiation of the life she has been assigned and a desire for a more expansive daily existence.Her faith is strong, but it’s dependent on only what other people have revealed to her about God. Later she tells Shug that she sees God as a white man. She has this belief because everyone she knows has said God is white and a male. Later, Shug tells her God has no race or gender. This enables Celie to see God in a different way. She realizes that you cannot place qualities on God because God is a part of the unknown. Her faith is now based on her interpretation of God, not one she learned from someone else. Even though Shug helped her with this realization, Celie only used this knowledge to shape her faith. Shug was a huge influence on Celie’s faith, but Celie was the one that had to choose how she would express it.

ALICE WALKER 作者 Everyday Use 课文简介

Made by 少媚、瑞冰

Everyday Use

Biography

CHILDHOOD

born in Eatonton, Georgia , on February, 1944 youngest of eight children, grew up mostly with her 5 oldest brothers 1952-her brother shot her eye out with a BB gun blinding her one eye

Collision

Hope of preserving the black’s culture

✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔

Rape Sexism Racism Violence Isolation Troubled relationships Multi-generational perspectives

Walker’s publishing

1968 Once (poetry)

1970-The Third

Mom Maggie Dee

conflict

different views on the African culture

◈ narrator of the story ◈ a typical black woman

◈ little education, poor, strong ◈ hard-working, independent,

♦ short story, widely studied

♦ first published in 1973 as part of In Love and

ALice-walker介绍

Child:

Rebecca born in 1969

2. Education:

1961-1963 Spelman, a college for black women in Atlanta 1963-1965 Sarah Lawrence College in New

York (once traveled to Africa as an exchange student)

Main works

课文主旨

所获奖项

awards

In 1997 she was honored by the American Humanist Association (美国 人道主义协会 )as“ Humanist of the year ”She has also received a number of other awards for her body of work ,including: The Lillian Smith Award (莉莲史密斯奖 ) from the National Endowment for Arts( 国家 艺术基金会 )。The Rosenthal Award from the National Institute of Arts&letters etc.

everyday use by alice walker译文

everyday use by alice walker译文以下是为您生成的译文:《艾丽斯·沃克的<日常使用>》原文这篇东西讲的呢,就是一些日常生活里的事儿。

咱一点点来掰扯掰扯。

先说这家人,有个老妈,还有俩闺女。

大闺女呢,叫迪伊,跑到大城市去混了,觉着自己可了不起,学了一堆花里胡哨的东西。

小闺女呢,叫麦姬,就在家里老老实实呆着,跟着老妈过日子。

有一天,迪伊回来了,打扮得那叫一个花枝招展,还带了个男朋友。

她一回来就瞅着家里这也不顺眼,那也不顺眼,觉得老妈和麦姬太土气。

老妈呢,一直守着家里的老物件,像什么被子啦,搅乳器啦。

迪伊就想要这些东西,说这是传统,是文化,要拿回去当宝贝供着。

可老妈心里清楚,这些东西真正的用处不是摆在那好看,而是日常使用。

麦姬呢,因为小时候被火烧伤过,有点自卑,也不咋说话。

但她心里明白家里这些东西的价值。

迪伊非要拿那些被子,老妈就不干,说这被子得留着日常用。

迪伊还不高兴了,觉得老妈不懂她的心思。

其实啊,老妈心里跟明镜似的,知道啥是真正的过日子,啥是表面的花架子。

最后老妈还是把被子给了麦姬,因为她知道麦姬会像一直以来那样,踏踏实实地用这些东西。

这故事说的就是,有时候咱别光追求那些看着高大上的东西,真正的生活还是平平常常、实实在在的好。

就像家里那些老物件,能用在日常生活里,那才有价值,光摆着好看有啥用?咱过日子得脚踏实地,别整那些虚头巴脑的。

这故事出自艾丽斯·沃克的手笔,她写这故事就是想让咱明白,生活的真谛就在那些日常的点点滴滴里,别瞎折腾,别光追求表面的光鲜。

咱得实实在在地过日子,珍惜身边那些普普通通却又实实在在的东西。

alice walker爱丽丝沃克

1 Walker was born in Putnam County, Georgia,[3] the youngest of eight children, to Willie Lee Walker and Minnie Lou Tallulah Grant. Her father, who was, in her words, "wonderful at math but a terrible farmer," earned only $300 ($4,000 in 2013 dollars)a year from sharecropping and dairy farming. Her mother supplemented the family income by working as a maid2 before graduating from university, in the trip of East Africa she pregnant, a bortion流产 is still illegal at that time, she experienced the pain of a suicidal p eriod, at the same time also wrote some poetry.In 1965, Walker met Melvyn Rosenman Leventhal, a Jewish civil rights lawyer. They were married on March 17, 1967 in New York City. Alice pregnant again, but unfortunately in Martin Luther King of the children at the funeral because of sorrow and loss. The couple had a daughter Rebecca in 1969. Walker and her husband divorced in 1976.[46]Alice then quit his job to writing full-time, in San Francisco, she experienced a "black scholar" editor Rob ert Aaron, soon to live with them.3 Her mother enrolled Alice in first grade at the age of four. Growing up with an oral tradition, listening to stories from her grandfather (the model for the character of Mr. in The Color Purple), Walker began writing, very privately, when she was eight years old. "With my family, I had to hide things," she said. "And I had to keep a lot in my mind. After high school, Walker went to Spelman College in Atlanta on a full scholarship in 1961 and latertransferred to Sarah Lawrence College near New York City, graduating in 1965. In 1967,She worked as writer in residence at Jackson State College (1968–1969) and Tougaloo College (1970–1971) and was a black history consultant to the Friends of the Children of Mississippi Head Start program.4 worksNovels and short story collectionThe Third Life of Grange Copeland (1970)《格兰奇·科普兰的第三次生命》∙In Love and Trouble: Stories of Black Women (1973)∙Meridian梅丽迪安(1976)∙The Color Purple紫色(1982)∙You Can't Keep a Good Woman Down: Stories (1982)∙To Hell With Dying (1988)∙The Temple of My Familiar (1989)∙Finding the Green Stone (1991)∙Possessing the Secret of Joy (1992)∙The Complete Stories (1994)∙By The Light of My Father's Smile (1998)∙The Way Forward Is with a Broken Heart (2000)∙Now Is The Time to Open Your Heart [a novel] (2004) Random House ISBN13 9781588363961∙Everyday Use (1973). Short stories, essays, interviews 个人简介Alice WalkerAKA Alice Malsenior WalkerBorn: 9-Feb-1944Birthplace: Eatonton, GAGender: FemaleReligion: BuddhistRace or Ethnicity: BlackSexual orientation: Bisexual [1]Occupation: AuthorNationality: United State奖项Pulitzer Prize for Fiction 1983 for The Color PurpleNational Book Award for Fiction 1983 for The Color PurpleHumanist of the Year 1997Ms. EditorKucinich for PresidentPeace Action 50th Anniversary Honorary Host Committee (2007)。

高级英语(4.2.2)--AliceWalker

Alice WalkerAlice Walker is an African American novelist, short-story writer, poet, essayist, and activist. Her most famous novel,The Color Purple, was awarded the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award in1983. Walker's creative vision is rooted in the economic hardship,racial terror,and folk wisdom of African American life and culture,particularly in the rural South.Her writing explores multidimensional kinships among women and embraces the redemptive power of social and political revolution.Walker began publishing her fiction and poetry during the latter years of the Black Arts movement in the 1960s. Her work, along with that of such writers as Toni Morrison and Gloria Naylor, however, is commonly associated with the post-1970s surge in African American women's literature.Early Life and EducationMalsenior Walker was born in Eatonton on February 9, 1944, the eighth and youngest child of Minnie Tallulah Grant and Willie Lee Walker, who were sharecroppers. The precocious spirit that distinguished Walker's personality during her early years vanished at the age of eight, when her brother scarred and blinded her right eye with a BB gun in a game of cowboys and Indians.Teased by her classmates and misunderstood by her family, Walker became a shy, reclusive youth. Much of her embarrassment dwindled after a doctor removed the scar tissue six years later. Although Walker eventually became high school prom queen and class valedictorian, she continued to feel like an outsider, nurturing a passion for reading and writing poetry in solitude.In 1961 Walker left Eatonton for Spelman College, a prominent school for black women in Atlanta, on a state scholarship. During the two years she attended Spelman she became active in the civil rights movement. After transferring to Sarah Lawrence College in New York, Walker continued her studies as well as her involvement in civil rights. In 1962 she was invited to the home of Martin Luther King Jr. in recognition of her attendance at the Youth World Peace Festival in Finland. Walker also registered black voters in Liberty County, Georgia, and later worked for the New York City Department of Welfare.Two years after receiving her B.A. degree from Sarah Lawrence in 1965, Walker married Melvyn Rosenman Leventhal, a white civil rights attorney. They lived in Jackson, Mississippi, where Walker worked as the black history consultant for a Head Start program. She also served as the writer-in-residence for Jackson State College (later Jackson State University) and Tougaloo College. She completed her first novel,The Third Life of Grange Copeland, in 1969, the same year that her daughter, Rebecca Grant, was born. When her marriage to Leventhal ended in 1977, Walker moved to northern California, where she lives and writes today.Walker has taught African American women's studies to college students at Wellesley, the University of Massachusetts at Boston, Yale, Brandeis, and the University of California at Berkeley. She supports antinuclear and environmental causes, and her protests against the oppressive rituals of female circumcision in Africa and the Middle East make her a vocal advocate for international women's rights. Walker has served as a contributing editor of Ms. magazine, and she is a cofounder of Wild Tree Press. Walker's appreciation for her matrilineal literary history is evidenced by the numerous reviews and articles she has published to acquaint new generations of readers with writers like Zora Neale Hurston. The anthology she edited, I Love Myself When I Am Laughing... and Then Again When I Am Looking Mean and Impressive: A Zora Neale Hurston Reader(1979), was particularly instrumental in bringing Hurston's work back into print. In addition to her deep admiration for Hurston, Walker's literary influences include Harlem Renaissance writer Jean Toomer,black Chicago poet Gwendolyn Brooks, South African novelist Bessie Head, and white Georgia writer Flannery O'Connor.PoetryThe poems in Walker's first volume, Once (1968), are based on her experiences during the civil rights movement and her travels to Africa. Influenced by Japanese haiku and the philosophy of author Albert Camus, Once also contains meditations on love and suicide. Indeed, after Walker visited Africa during the summer of 1964, she had struggled with an unwanted pregnancy upon her return to college. She speaks openly in her writing about the mental and physical anguish she experienced before deciding to have an abortion. The poems in Once grew not only from the sorrowful period in which Walker contemplated death but also from her triumphant decision to reclaim her life.Revolutionary PetuniasMany of the narrative poems of her second volume,Revolutionary Petunias and Other Poems (1973), revisit her southern past, while other verses challenge superficial political militancy. The collection won the Lillian Smith Book Award (named for Georgia writer Lillian Smith and administered by the Southern Regional Council) in 1973. Good Night, Willie Lee, I'll See You in the Morning (1979) contains tributes to black political leaders and creative writers. In addition to a fourth volume of poetry, Horses Make a Landscape Look More Beautiful(1984), Walker has compiled her previously published verses in the collection Her Blue Body Everything We Know:Earthling Poems 1965-1990 Complete(1991). In a review of Absolute Trust in the Goodness of the Earth:New Poems(2003),Publishers Weekly highlighted the volume's spiritual and ecological topics and added that Walker"explor[es]and prais[es] friendship, romantic love, home cooking, the peace movement, ancestors, ethnic diversity,and particularly admirable strong women,among them the primatologist Jane Goodall."Walker's most recent volume of poems,A Poem Traveled Down My Arm, was published in 2005.Short Fiction and EssaysOne of Walker's earliest stories, "To Hell with Dying," captured the attention of poet Langston Hughes, who included it in his 1967 anthology, The Best Short Stories by Negro Writers. In the tale, which is based on actual events, the joy and laughter of children rescue an old guitar player named Mr. Sweet from the brink of death year after year. The narrator—a girl at the start of the story—returns home as a young woman to "revive" Mr. Sweet, but with no success. After his death she inherits the bluesman's guitar and his enduring legacy of love."To Hell with Dying" was reprinted in Walker's first collection of short fiction,In Love and Trouble: Stories of Black Women (1973). The thirteen stories in this volume feature black women struggling to transcend society's narrow definitions of their intelligence and virtue. Her second collection, You Can't Keep a Good Woman Down: Stories (1982), continues her vivid portrayal of women's experiences by emphasizing such sensitive issues as rape and abortion. In 2000 Walker published a third collection of stories,The Way Forward Is with a Broken Heart. She has also written four children's books, including an illustrated version of To Hell with Dying(1988) and Finding the Green Stone (1991).Walker has published several volumes of essays and autobiographical reflections. In the1983collection In Search of Our Mothers'Gardens:Womanist Prose,she introduced readers to a new ideological approach to feminist thought.Her term womanist characterizes black feminists who cherish women's creativity, emotional flexibility, and strength.Womanism is further used to suggest new ways of reading silence and subjugation in narratives of male domination. The collection won the Lillian Smith Book Award in 1984. Other essay collections include The Same River Twice: Honoring the Difficult (1996), which features Walker's account of her struggle with Lyme disease during the filming of The Color Purple, and Sent by Earth: A Message from the Grandmother Spirit: After the Attacks on the World Trade Center and Pentagon (2002).NovelsLike her short stories, Walker's six novels place more emphasis on the inner workings of African American life than on the relationships between blacks and whites. Her first book,The Third Life of Grange Copeland(1970),details the sorrow and redemption of a rural black family trapped in a multigenerational cycle of violence and economic dependency. Walker also fictionalizes a young civil rights activist's coming-of-age in the novel Meridian (1976).The Color Purple (1982) has generated the most public attention as a book and as a major motion picture, directed by Steven Spielberg in 1985. Narrated through thevoice of Celie, The Color Purple is an epistolary novel—a work structured through a series of letters. Celie writes about the misery of childhood incest, physical abuse, and loneliness in her "letters to God." After being repeatedly raped by her stepfather, Celie is forced to marry a widowed farmer with three children. Yet her deepest hopes are realized with the help of a loving community of women, including her husband's mistress, Shug Avery, and Celie's sister, Nettie. Celie gradually learns to see herself as a desirable woman, a healthy and valuable part of the universe.Set in rural Georgia during segregation,The Color Purple brings components of nineteenth-century slave autobiography and sentimental fiction together with a confessional narrative of sexual awakening. Walker's harshest critics have condemned her portrayal of black men in the novel as "male-bashing," but others praise her forthright depiction of taboo subjects and her clear rendering of folk idiom and dialect. In 1985 the novel was adapted into a film, directed by Steven Spielberg. The musical stage adaptation premiered at the Alliance Theatre in Atlanta in 2004 and opened on Broadway in 2005.Literary scholars often link The Color Purple with Walker's next two novels in an informal trilogy. Celie's granddaughter, Fanny, is a major character in The Temple of My Familiar(1989), and the protagonist of Possessing the Secret of Joy(1992) is Tashi, the African wife of Celie's son. In Walker's novel By the Light of My Father's Smile (1998), strong sexual and religious themes intersect in a tale narrated from both sides of the grave. The novel features a family of African American anthropologists who journey to Mexico to study a tribe descended from former black slaves and Native Americans. In Now Is the Time to Open Your Heart (2004) the main character, Kate, embarks on a literal and spiritual journey to find a way to accept the aging process. Walker says that Kate's search is necessary because the territory is largely "uncharted," and "people seem to lose their imagination about what women's lives can be after, say, 55 or 60."Reflecting on the unique perspective and versatility of her literary career, Walker says, "One thing I try to have in my life and my fiction is an awareness of and openness to mystery, which, to me, is deeper than any politics, race, or geographical location." With elements of ancestral fable and spirituality, womanist insight, literary realism, and the grotesque, Walker's writing embodies an abundant cultural landscape of its own.In2001Walker was inducted into the Georgia Writers Hall of Fame.Emory University in Atlanta acquired Walker's personal and literary archives in 2007 and began cataloging her papers the following year.。

翻译TheColorPurplebyAliceWalker

翻译TheColorPurplebyAliceWalker 《紫色》是爱丽丝·沃克创作的小说作品,原名为"The Color Purple"。

该作于1982年出版并获得了普利策奖等多个文学奖项。

小说以主人公塞利·盖乔的视角展开,讲述了一个黑人女性在种族歧视和性别压迫下的成长与坚韧奋斗。

通过这个故事,沃克揭示了美国南方农村黑人社区的社会问题、家庭问题以及黑人妇女在其中所面临的双重压迫。

小说以塞利的信件和日记形式展现,读者通过她的叙述认识到她从被虐待、被剥夺自由的青少年,逐渐成长为一个自信、独立、拥有自己的声音和生活的女性。

故事主要发生在20世纪初期,讲述了塞利从小就生活在农村的贫困黑人社区,她在14岁时被父亲强迫与“先生”结婚,婚后的生活充满暴力和苦难。

塞利受到了父亲和丈夫的虐待,但她并未失去自我,她借助写信和日记的方式,不仅表达了内心的痛苦和希望,还与她的良师索菲娅建立了深厚的友谊。

正是在这种友谊的支持下,塞利逐渐找回自己的勇气和力量,勇敢地反抗父亲和丈夫的压迫,并最终摆脱了他们的控制。

另一方面,小说也描述了塞利与前夫好友的曼·莱·格罗的感情发展。

曼·莱·格罗是一位黑人活动家,他通过阳光般的笑容、善良的言行以及对黑人社区的改善工作,渐渐赢得了塞利的心。

两人的感情逐渐升温,塞利迈出了解脱的一步。

小说《紫色》通过描写塞利的成长经历和她所遭受的剥夺,探讨了种族、阶级、性别、家庭关系等问题,并呼吁人们关注和改变这些社会问题。

故事中的塞利象征着黑人妇女的独立和坚韧,她们经历了一系列斗争和磨难,最终实现了内心的自由和解放。

沃克通过细腻的笔触和独特的叙述方式,引导读者思考种族和性别之间的交叉问题,以及社会的不公和压迫对个体生命的摧残。

小说并没有给出简单的答案和解决方案,而是通过对塞利等人的塑造和生活经历的描绘,希望唤醒读者对这些问题的思考和关注。

艾丽斯·沃克《紫色》的象征隐喻解析

艾丽斯·沃克《紫色》的象征隐喻解析关键词:黑人文化女性主义象征隐喻摘要:美国黑人文学的女性代表作家艾丽斯·沃克以黑人民族的独特文化内涵来彰显“黑人美”。

在长篇小说《紫色》中,她成功运用了黑人文学最突出的艺术手法——象征隐喻。

基于盖茨的喻指理论,对《紫色》中的象征隐喻艺术手法进行了解析。

非洲裔美国黑人女作家艾丽斯·沃克(Alice Walker)出生于美国黑人聚居的佐治亚州的贫困乡村,自幼耳闻目睹南方黑人的悲惨生活,尤其是黑人妇女,她们遭受双重压迫——一方面受到白人社会的歧视,另一方面又忍受着黑人男性的欺压,因为黑人社会也沿袭了白人社会对待男性和女性的双重标准。

正如胡克斯所说,“黑人妇女不仅在白人统治者手下受折磨,而且也在黑人男人手下受折磨。

”在大学时代,沃克就积极参加民权运动,并立志将争取种族平等和黑人妇女解放作为自己的终身事业。

因此,沃克的小说创作始终植根于美国黑人的文化传统,美国黑人,尤其是美国黑人妇女的历史、命运和前途是其小说创作的主题,她关注的焦点主要集中在处于社会最底层的黑人妇女的命运和她们的精神世界。

与同时代的美国黑人女作家托尼·莫里森一道,沃克把黑人女性推上了美国文学,特别是美国黑人文学的殿堂,让世人听到了她们的呻吟和呐喊。

美国黑人评论家玛丽·海伦·华盛顿称沃克为黑人妇女的“辩护士”,说她是“为了捍卫一个事业或一种立场而发言写作的”。

沃克的代表作长篇小说《紫色》为读者建构了一个在异质文化侵蚀下怪诞、变形的黑人世界,成功地塑造了主人公茜莉在白人社会和黑人男性双重压迫下寻找自我、重塑自我,从而获得新生的艰难历程。

《紫色》连获美国三项大奖——普利策奖、美国图书奖、全国图书评委协会奖,细细品味,我们不难发现:小说采用书信体形式的叙述方式,运用娴熟的黑人民间口语和象征隐喻的手法刻画人物并探寻人物的心灵,人物形象鲜活生动,栩栩如生;作者不是仅仅停留在描写黑人妇女的悲惨生活上,而是深入探讨黑人女性遭受不公平待遇的社会历史根源,并寻求解决途径——妇女之间的互爱互助是她们获得幸福和自的最佳手段。

Alice walker语言风格

Alice walker语言风格

Alice walker语言风格既有强烈的批判性又有传统的积极和乐观态度。

例如其代表小说《紫色》描述了一位受旧思想束缚的黑人妇女的转变和成长过程,充分展现了黑人女性深受性别和种族双重压迫的现实状况和生活境遇,以及对这种双重压迫的反抗和对完善自我及完美生活的渴望与追求,深刻反映了作者的妇女主义思想。

《紫色》还深刻地揭示了妇女主义思想的内涵和对黑人妇女求解放、求平等的积极意义。

如第一人称复数用Us,用大写的He或Pa 指代主角的继父,用Mr-称呼那些不配有姓名的男人等,揭示黑人男女,黑人家庭。

黑人内部的弊病,这种与众不同的语言策略充分体现了作者的黑人意识和民族观念。

Alice Walker

Growing up with an oral tradition, listening

Early life and Experiences

At the age of 8,she lost sight of one eye

by accident. She went on to become valedictorian of her local school and attended Spelman College ,Sarah Lwrence College by scholarship,graduating in 1965. She was even invited to Martin Luther King's home because she had attended the Youth World Peace Festival in Helsinki,Finland.

California Institute of the Arts(加州艺术学 院) In1997 American Humanist Association (美 国人道主义协会)named her as "Humanist of the Year"

Selected awards and honors

The Lillian Smith Award(莉莲史密斯奖)

from the National Endowment for the Arts (国家艺术基金) The Rosenthal Award from the National Institute of Arts & Letters The Radcliffe Institute Fellowship,(拉德克 里夫学院奖学金) the Merrill Fellowship(梅林 奖学金), and a Guggenheim Fellowship(古根 海姆奖学金)

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

Writing career

• Walker has written several other novels, including The Temple of My Familiar and Possessing the Secret of Joy(which featured several characters and descendants of characters from The Color Purple). She has published a number of collections of short stories, poetry, and other writings. Her work is focused on the struggles of black people, particularly women, and their lives in a racist, sexist, and violent society. Walker is a leading figure in liberal politics.

Writing career

• In addition to her collected short stories and poetry, Walker's first novel, The Third Life of Grange Copeland, was published in 1970. In 1976, Walker's second novel, Meridian, was published. The novel dealt with activist workers in the South during the civil rights movement, and closely paralleled some of Walker's own experiences. • In 1982, Walker published what has become her bestknown work, The Color Purple. The novel follows a young troubled black woman fighting her way through not just racist white culture but patriarchal black culture as well. The book became a bestseller and was subsequently adapted into a critically acclaimed 1985 movieas well as a 2005 Broadwaymusical.

A lic e W a lk e r

• • • •

Life experience Writing career Selected awards and honors works

Alice Malsenior Walker (born February 9, 1944) is an American author and activist. She wrote the critically acclaimed novel The Color Purple (1982) for which she won the National Book Award and the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction. She also wrote Meridian and The Third Life of Grange Copeland among other works.

Life experience

• Walker was born in Putnam County, Georgia,the youngest of eight children, to Willie Lee Walker and Minnie Lou Tallulah Grant. Her father, who was, in her words, "wonderful at math but a terrible farmer," earned only $300 a year from sharecropping and dairy farming. Her mother supplemented the family income by working as a maid.She worked 11 hours a day for $17 per week to help pay for Alice to attend college.Growing up with an oral tradition, listening to stories from her grandfather (who was the model for the character of Mr. in The Color Purple), Walker began writing, very privately, when she was eight years old.

via./s/blog_4c4ec62a0102ewd1.html

Selected awards and honors

• Ingram Merrill Foundation Fellowship (1967) • Pulitzer Prize for Fiction (1983) for The Color Purple • National Book Award for Fiction (1983) for The Color Purple • O. Henry Award for "Kindred Spirits" (1985) • Honorary degree from the California Institute of the Arts (1995) • American Humanist Association named her as "Humanist of the Year" (1997) • Lillian Smith Award from the arts • Induction into the Georgia Writers Hall of Fame • Induction into the California Hall of Fame in The California Museum for History, Women, and the Arts (2006) • The LennonOno Grant for Peace (2010) via.Wikipedia

Works

Novels and short story collections • The Third Life of Grange Copeland (1970)《格兰奇· 科普兰的第三次 生命》 • In Love and Trouble: Stories of Black Women (1973, includes "Everyday Use")《在爱情和麻烦中》 • Meridian (1976)《子午线》 • The Color Purple (1982)《紫色》 • You Can't Keep a Good Woman Down: Stories (1982)《你压不倒一 个好女人》 • To Hell With Dying (1988)《让死见鬼去吧》 • The Temple of My Familiar (1989)《殿堂》 • Finding the Green Stone (1991) • Possessing the Secret of Joy (1992)《拥有喜悦的秘密》 • The Complete Stories (1994)《完整的故事》 • By The Light of My Father's Smile (1998)《父亲的微笑》 • The Way Forward Is with a Broken Heart (2000)《前进道路上怀着一 颗破碎的心》 • Now Is the Time to Open Your Heart (2004) 《现在可以敞开你的心 扉了》

• 艾丽斯· 沃克(Alice Walker),普利策奖得主、小说 家、诗人和社会运动人士,她在作品中反映黑人 妇女为自身权利而奋斗,获得广大的回响,著有 《紫色》(The Color Purple)。小说改编成剧本 《紫色》是美国电影史上第一部黑人题材的电影, 主要演员几乎全部为黑人之外,参与影片摄制的 工作人员也大半为有色人种。导演斯皮尔伯格, 女主角喜丽(Celie)由琥碧· 戈德堡 (Whoopi Goldberg)饰演。是获奥斯卡11项提名无一获奖 的影片

• 艾丽斯·沃克1944年2月9日出生于南方佐治亚州的一个佃农家庭, 父母的祖先是奴隶和印度安人,艾丽斯是家里八个孩子中最小的 一个。艾丽斯8岁时,在和哥哥们玩“牛仔与印度安人”的游戏 时被玩具枪射瞎了右眼。1961年艾丽斯获奖学金入亚特兰大的斯 帕尔曼大学学习,正赶上美国民权运动的高涨时期,她即投身于 这场争取种族平等的政治运动。1962年,艾丽斯·沃克被邀请到 马丁·路德·金的家里做客。1963年艾丽斯到华盛顿参加了那次 著名的游行,与万千黑人一同聆听马丁·路德·金“我有一个梦 想”的讲演。1965年艾丽斯大学毕业后回到了当时是民权运动中 心的南方老家继续参加争取黑人选举权的运动。在活动中艾丽斯 遇上了犹太人列文斯尔,俩人克服跨种族婚姻的重重困难结为 “革命伴侣”,艾丽斯再一次怀孕,但不幸的是在参加马丁·路 德·金的葬礼时因悲伤而痛失孩子。在列文斯尔的鼓励下,艾丽 斯继续写作并先后发表了诗集《一度》(Once,1968)和小说 《格兰奇·科普兰的第三次生命》(The Third Life of GrangeCopeland,1970)。1972年艾丽斯到威尔斯利大学任教, 开设了“妇女文学”课程,这是美国大学最早开设的女性研究课 程。1973年、1976年艾丽斯先后出版了小说集《爱e