2010 AHA 心肺复苏指南(实用中文版)

2010版心肺复苏指南

2019/3/10

CPR2010国际新指南

修改要点-7

7.不建议在心脏停止时常规作环状软骨按压

理由:虽然环状软骨按压可在球囊面罩通气期间避 免发生胃胀气,并减少胃酸反流与吸入的风险, 但也可能阻碍通气 。

可能延迟或阻碍高级呼吸道装置的放置 仍可能发生吸入情形

要适当训练施救者使用此操作法很困难 。

2019/3/10

CPR2010国际新指南

新指南BLS部分

2019/3/10

2019/3/10

CPR2010国际新指南

关于判断

医务人员在检查反应时应该快速检查有无呼吸或不能正

常呼吸(即无呼吸或仅是喘息) 然后该人员启动急救系统并找到AED(或由其他人员 寻找) 医务人员检查脉搏的时间不应超过10秒,如果10秒内没 有明确触摸到脉搏,应开始心肺复苏并使用AED(如果 有的话)

已从流程中去除“看、听和感觉呼吸”

2019/3/10

CPR2010国际新指南

修改要点-1

1. 应提高急救人员与非专业施救者对心脏 停止的辨识能力

医务人员应电话指导非专业施救者于患者「没 有反应,沒有呼吸或沒有正常呼吸 (即仅有喘 息)」时开始 CPR,而无需检查脉搏对医务人 员亦不强调一定要先检查清楚脉搏(如10秒钟 内没有明确触摸到脉搏,则应开始CPR) 理由:紧急情况下,通常无法准确地判断脉搏 是否存在,特别是脉搏细弱时 。

2019/3/10

CPR2010国际新指南

修改要点-10

10. 儿童和婴儿使用AED 在无法取得手动除颤仪及配备剂量衰减 功能的AED时,可使用普通AED 理由:适用于婴儿和儿童有效除颤的最 低能量剂量及安全除颤的上限均不明确, 但>4 J/Kg (最大 9 J/Kg) 的剂量可有效 为儿童和动物实验模型的小儿心脏除颤, 且不会有显著的副反应

2010美国心脏协会心肺复苏及心血管急救指南+官方简体中文版

本

题问要主的者救施有所对针

。据依的议建南指了出给 还外此。议建导指的容内训培苏复或作操苏复改更致导能可有 或的议争有及以学苏复于注专们他助帮在旨�师导会协脏心国 美和员人救急向面容内的要摘本。结总的更变和题 问要重些一》南指 )CCE( 救急管血心及 )RPC( 苏复 肺心 )AHA( 会协脏心国美 0102《对是”要摘南指“

录目

要 摘 》 南 指救急管血心及 苏 复 肺 心 会协脏心国美 0102《

n o i ta ic o s sA tr ae H na c ir emA 0 1 0 2 ©

授教 ,鸣一陆

对校版文中体简

DM ,keoH nednaV .L y rreT cSM ,DM ,srevarT .H werdnA DM ,retsuhS leahciM HPM ,DM ,aeR .D samohT BhC ,BM ,namlreP .M yerffeJ DM ,ydrebeP nnA y raM HPM ,DM ,ronnoC ’O .E t reboR DhP ,DM ,ramueN .W t reboR cSM ,DM ,nosirroM .J eiruaL DM ,kniL .S kraM DM ,kuhcneduK .J reteP DM ,namnielK .E acinoM DM ,lekniwttaK nhoJ SM ,DM ,hcuaJ .C drawdE DM ,yekciH .W t reboR P-TMERN ,DM ,nosugreF .D yerffeJ DM ,araihccuC tterB NEC ,NSM ,NR ,evaC .M anaiD DhP ,DM ,yawallaC .W notfilC DM ,illiB .E nhoJ DM ,ijnahB nahraF DM ,greB .A t reboR DM ,greB .D craM DM ,eryaS .R leahciM

2010AHA心肺复苏指南解读

①按压时除掌根部贴在胸骨外,手指也压在胸壁上,这容易 引起肋骨或肋骨肋软骨交界处骨折。 ②按压定位不正确。向下错位易使剑突受压折断而致肝破裂。 向两侧错位易致肋骨或肋骨肋软骨交界处骨折,导致气胸、 血胸。 ③抢救者按压时肘部弯曲,因而用力不垂直,按压力量减弱, 按压深度达不到5cm(图)。 ④冲击式按压、猛压,其效果差,且易导致骨折。 ⑤放松时抬手离开胸骨定位点,造成下次按压部位错误,引 起骨折。 ⑥放松时未能使胸部充分松弛,胸部仍承受压力,使血液难 以回到心脏。 ⑦按压速度不自主地加快或减慢,影响了按压效果。 ⑧两手掌不是重叠放臵,而呈交叉放臵。

1、吹气应有足够的气量,以使胸廓抬起,但一般不超过 1200mL。 2、吹气时间宜短,以占1次呼吸周期的1/3为宜;吹气频 率,8-10次/分。 3、操作前先清除患者口腔及咽部的分泌物或堵塞物。 4、有义牙者应取下义牙。遇舌后坠的患者,应用舌钳将 舌拉出口腔外,或用通气管吹气。 5、对婴幼儿,则对口鼻同时吹气更易施行 6、若患者尚有微弱呼吸,人工呼吸应与患者的自主呼吸 同步进行。 7、注意防止交叉感染。 8、通气适当的指征是看到患者胸部起伏并于呼气时听到 及感到有气体逸出。

中断按压时间不超过10s 确认气管导管位臵 : 临床评价:双侧胸廓有无对称起伏 两侧腋中线听诊两肺呼吸音是否对称 上腹部听诊:不应该有呼吸音 呼吸CO2监测或者食管探测

潮气量:500~600ml,胸廓明显 起伏 送气时间大于1s 频率:8~10次/分 避免过度通气

基 础 生 命 支 持 总 结

1.能扪及大动脉搏动,收缩压>60mmHg 2.患者面色、口唇、甲床、皮肤等色泽转红 3.散大的瞳孔再度缩小 4.呼吸改善或出现自主呼吸 5.心电显示明显的RS波 6.昏迷变浅,出现各种反射,肢体出现无意识的 挣扎动作.

2010版心肺复苏指南

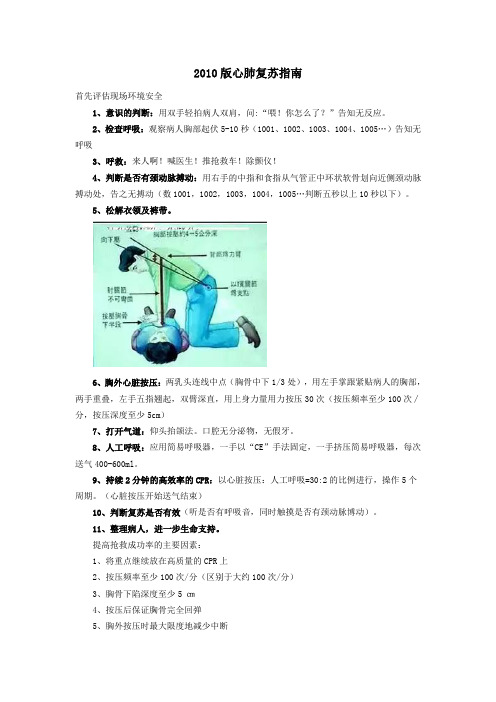

2010版心肺复苏指南首先评估现场环境安全1、意识的判断:用双手轻拍病人双肩,问:“喂!你怎么了?”告知无反应。

2、检查呼吸:观察病人胸部起伏5-10秒(1001、1002、1003、1004、1005…)告知无呼吸3、呼救:来人啊!喊医生!推抢救车!除颤仪!4、判断是否有颈动脉搏动:用右手的中指和食指从气管正中环状软骨划向近侧颈动脉搏动处,告之无搏动(数1001,1002,1003,1004,1005…判断五秒以上10秒以下)。

5、松解衣领及裤带。

6、胸外心脏按压:两乳头连线中点(胸骨中下1/3处),用左手掌跟紧贴病人的胸部,两手重叠,左手五指翘起,双臂深直,用上身力量用力按压30次(按压频率至少100次∕分,按压深度至少5cm)7、打开气道:仰头抬颌法。

口腔无分泌物,无假牙。

8、人工呼吸:应用简易呼吸器,一手以“CE”手法固定,一手挤压简易呼吸器,每次送气400-600ml。

9、持续2分钟的高效率的CPR:以心脏按压:人工呼吸=30:2的比例进行,操作5个周期。

(心脏按压开始送气结束)10、判断复苏是否有效(听是否有呼吸音,同时触摸是否有颈动脉博动)。

11、整理病人,进一步生命支持。

提高抢救成功率的主要因素:1、将重点继续放在高质量的CPR上2、按压频率至少100次/分(区别于大约100次/分)3、胸骨下陷深度至少5 ㎝4、按压后保证胸骨完全回弹5、胸外按压时最大限度地减少中断6、避免过度通气心肺复苏 = (清理呼吸道) + 人工呼吸 + 胸外按压 + 后续的专业用药据美国近年统计,每年心血管病人死亡数达百万人,约占总死亡病因1/2。

而因心脏停搏突然死亡者60-70%发生在院前。

因此,美国成年人中约有85%的人有兴趣参加CPR初步训练,结果使40%心脏骤停者复苏成功,每年抢救了约20万人的生命。

心脏跳动停止者,如在4分钟内实施初步的CPR,在8分钟内由专业人员进一步心脏救生,死而复生的可能性最大,因此时间就是生命,速度是关键,初步的CPR按ABC进行。

2010心肺复苏指南(中文版)

2010心肺复苏指南(中文版)《2010`AHA CPR&ECC 指南》新亮点《2010`心肺复苏与心血管急救指南》已经公开发表,该指南框架结构与《2005`心肺复苏与心血管急救指南》基本相似。

经过五年的应用实施,有相应的调整!几个最主要变化是:1.生存链:由2005年的四早生存链改为五个链环:(1)尽早识别与激活EMSS;(2)尽早实施CPR:强调胸外心脏按压,对未经培训的普通目击者,鼓励急救人员电话指导下仅做胸外按压的CPR;(3)快速除颤:如有指征应快速除颤;(4)有效的高级生命支持(ALS);(5)综合的心脏骤停后处理。

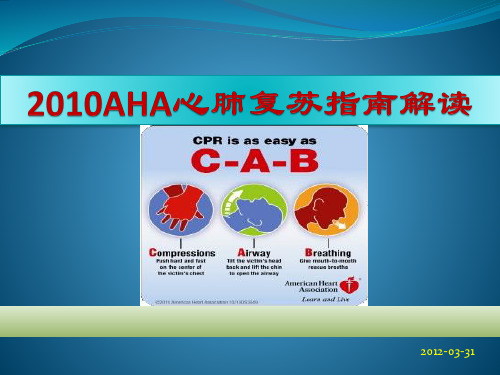

2.几个数字的变化:(1)胸外按压频率由2005年的100次/分改为“至少100次/分”(2)按压深度由2005年的4-5cm改为“至少5cm”(3)人工呼吸频率不变、按压与呼吸比不变(30:2)(4)强烈建议普通施救者仅做胸外按压的CPR,弱化人工呼吸的作用,对普通目击者要求对ABC改变为“CAB”即胸外按压、气道和呼吸(5)除颤能量不变,但更强调CPR(6)肾上腺素用法用量不变,不推荐对心脏停搏或PEA者常规使用阿托品(7)维持ROSC的血氧饱和度在94%-98%(8)血糖超过10mmol/L即应控制,但强调应避免低血糖(9)强化按压的重要性,按压间断时间不超过5s3.整合修改了BLS和ACLS程序图2010新亮点:《2010`心肺复苏&心血管急救指南》《2010`AHA CPR&ECC指南》《2010`AHA CPR&ECC指南》成人CPR操作主要变化如下:突出强调高质量的胸外按压保证胸外按压的频率和深度,最大限度地减少中断,避免过度通气,保证胸廓完全回弹提高抢救成功率的主要因素1、将重点继续放在高质量的CPR上2、按压频率至少100次/分(区别于大约100次/分)3、胸骨下陷深度至少5 ㎝4、按压后保证胸骨完全回弹5、胸外按压时最大限度地减少中断6、避免过度通气CPR操作顺序的变化:A-B-C→→C-A-B★2010(新):C-A-B即:C胸外按压→A开放气道→B人工呼吸●2005(旧):A-B-C即:A开放气道→B人工呼吸→C胸外按压生存链的变化★2010(新):1、立即识别心脏骤停,激活急救系统2、尽早实施CPR,突出胸外按压3、快速除颤4、有效地高级生命支持5、综合的心脏骤停后治疗●2005(旧):1、早期识别,激活EMSS2、早期CPR3、早期除颤4、早期高级生命支持(ACLS)应及时识别无反应征象,立即呼激活应急救援系统。

2010国际心肺复苏指南

基础生命支持—BLS

• 非医务人员亦可实施,开始的时间越早越好 • 目前国际上普遍采用的BLS手法是根据1980年

日内瓦国际会议决定的,由美国心脏病学会经历数次 国际心肺复苏会议不断改进完善所颁布的标准 • 2005第二次国际心肺复苏会议仍然推荐BLS按照英 文字母A、B、C、的顺序进行:A-气道;B-呼吸 支持;C-循环支持。

心跳骤停的心电图分型

• 心室停搏(伴或不伴心房静止) 心 肌完全失去电活动能力,心电图上表 现为一条直线。常见窦性、房性、结 性冲动不能达到心室,且心室内起搏 点不能发出冲动。

气道阻塞的常见病因

呼吸道阻塞系指呼吸器官(口、鼻、 咽、喉、气管、支气管、细支气管和肺 泡)的任何部位发生阻塞或狭窄,阻碍 气体交换,或呼吸道邻近器官病变引起 的呼吸道阻塞,以至发生阻塞性呼吸困 难的总称。

无氧缺血时脑细胞损伤的进程

脑循环中断: • 10秒—— 脑氧储备耗尽 • 20-30秒—— 脑电活动消失 • 4分钟 ——脑内葡萄糖耗尽,糖无氧代谢停止 • 5分钟——脑内ATP枯竭,能量代谢完全停止 • 4-6分钟——脑神经元发生不可逆的病理改变 • 6小时—— 脑组织均匀性溶解

心跳骤停的常见病因

心肺复苏

A:即判断有无意识、畅通呼吸道。

a) 使病人去枕后仰于地面或硬板床上,解开衣领 及裤带;

b) 畅通呼吸通道,清理口腔、鼻腔异物或分泌物 、假牙等;

c) 开放气道手法:仰面抬颌法、仰面抬颈法、托 下颌法。

开放气道手法

• 仰面抬颌法 要领:用一只手

按压伤病者的前额, 使头部后仰,同时用 另一只手的食指及中 指将下颏托起。

心肺复苏

B:即人工呼吸 人工呼吸就是用人工的方法帮助病人呼吸, 是心肺复苏基本技术之一。

AHA心肺复苏指南2010

4

胸外按压速率: 每分钟至少 100 次

2010(新):非专业施救者和医务人员以每分钟至少 100 次

按压的速率进行胸外按压较为合理。 理由:心肺复苏过程中的胸外按压次数对于能否恢复自主循 环以及存活后是否具有良好神经系统功能非常重要。每分钟 的实际胸外按压次数由胸外按压速率以及按压中断(例如, 开放气道、进行人工呼吸或进行 AED 分析)的次数和持续时 间决定。 在大多数研究中,在复苏过程中给予更多按压可提高存活率, 而减少按压则会降低存活率。进行足够胸外按压不仅强调足 够的按压速率,还强调尽可能减少这一关键心肺复苏步骤的 中断。 如果按压速率不足或频繁中断(或者同时存在这两种情况), 会减少每分钟给予的总按压次数.

强调胸外按压

如果旁观者未经过心肺复苏培训,则应进行Hands-Only™ (单纯胸按压)的心肺复苏,即仅为突然倒下的成人患者进 行胸外按压并强调在胸部中央用力快速按压,或者按照急救 调度的指示操作。 施救者应继续实施单纯胸外按压心肺复苏,直至 AED 到达且 可供使用,或者急救人员或其他相关施救者已接管患者。 所有经过培训的非专业施救者应至少为心脏骤停患者进行胸 外按压。 如果经过培训的非专业施救者有能力进行人工呼吸,应按照 30 次按压对应 2 次呼吸的比率进行按压和人工呼吸。 理由:单纯胸外按压(仅按压)心肺复苏对于未经培训的施 救者更容易实施,而且更便于调度员通过电话进行指导。另 外,对于心脏病因导致的心脏骤停,单纯胸外按压心肺复苏 或同时进行按压和人工呼吸的心肺复苏的存活率相近。不过, 对于经过培训的非专业施救者,仍然建议施救者同时实施按 压和通气。

同步电复律

室上性快速心律失常

2010 AHA 心肺复苏指南(实用中文版)

下面的章节概述了生存链的前三个链环:立即识别心脏骤停和启动急救反应系统、尽早CPR 及迅速除颤。按照认识施救者、患者和各种资源的实际多样性的方式介绍这些资料。

CPR 的概念性框架:施救者和患者的相互作用

CPR传统上将胸外按压和人工呼吸相结合以达到优化循环和氧合的目的。施救者和患者的特 点可能影响CPR各部分的最佳应用。

当取来AED/除颤器时,如果可能则使用电极帖,不要中断胸外按压,打开AED“开”关。AED 将分析心律,指示施救者进行电击(即除颤)或继续CPR。

如果得不到AED/除颤器,继续CPR不要中断,直到更多有经验的施救者接手。

识别和启动急救反应

迅速启动急救和开始CPR需要快速识别心脏骤停。心脏骤停患者没有反应。没有呼吸或呼吸 不正常。心脏骤停后早期濒死喘息(agonal gasps)常见,会与正常呼吸混淆。即使是受过培训 的施救者单独检查脉搏也常不可靠,而且需要额外的时间。因此,假如成年患者无反应、没有呼 吸或呼吸不正常(即只有喘息),施救者应当立即CPR。不再推荐“看、听和感觉呼吸”辅助识 别(诊断)的方法。

第 6 页 共 83 页

2010 AHA 心肺复苏指南(实用中文版)

图2.CPR的组成成分(building blocks)

高度

训练

多名施救者协同 CPR

施救者熟练程度

《2010美国心脏协会心肺复苏及心血管急救指南》完整中文版

《2010`AHA CPR&ECC 指南》1.生存链:由2005年的四早生存链改为五个链环:(1)尽早识别与激活EMSS;(2)尽早实施CPR:强调胸外心脏按压,对未经培训的普通目击者,鼓励急救人员电话指导下仅做胸外按压的CPR;(3)快速除颤:如有指征应快速除颤;(4)有效的高级生命支持(ALS);(5)综合的心脏骤停后处理。

2.几个数字的变化:(1)胸外按压频率由2005年的100次/分改为“至少100次/分”(2)按压深度由2005年的4-5cm改为“至少5cm”(3)人工呼吸频率不变、按压与呼吸比不变(4)强烈建议普通施救者仅做胸外按压的CPR,弱化人工呼吸的作用,对普通目击者要求对ABC改变为“CAB”即胸外按压、气道和呼吸(5)除颤能量不变,但更强调CPR(6)肾上腺素用法用量不变,不推荐对心脏停搏或PEA者常规使用阿托品(7)维持ROSC的血氧饱和度在94%-98%(8)血糖超过10mmol/L即应控制,但强调应避免低血糖(9)强化按压的重要性,按压间断时间不超过5s3.整合修改了BLS和ACLS程序图2010新亮点:《2010`心肺复苏&心血管急救指南》《2010`AHA CPR&ECC指南》《2010`AHA CPR&ECC指南》成人CPR操作主要变化如下:突出强调高质量的胸外按压保证胸外按压的频率和深度,最大限度地减少中断,避免过度通气,保证胸廓完全回弹提高抢救成功率的主要因素1、将重点继续放在高质量的CPR上2、按压频率至少100次/分(区别于大约100次/分)3、胸骨下陷深度至少5 ㎝4、按压后保证胸骨完全回弹5、胸外按压时最大限度地减少中断6、避免过度通气CPR操作顺序的变化:A-B-C→→C-A-B★2010(新):C-A-B即:C胸外按压→A开放气道→B人工呼吸●2005(旧):A-B-C即:A开放气道→B人工呼吸→C胸外按压生存链的变化★2010(新):1、立即识别心脏骤停,激活急救系统2、尽早实施CPR,突出胸外按压3、快速除颤4、有效地高级生命支持5、综合的心脏骤停后治疗●2005(旧):1、早期识别,激活EMSS2、早期CPR3、早期除颤4、早期高级生命支持(ACLS)应及时识别无反应征象,立即呼激活应急救援系统。

2010年心肺复苏指南解读

二、以团队形式实施心肺复苏

2010(新):大多数急救系统和医疗服务系统都需要 施救者团队的参与,由不同的施救者同时完成多个操 作。例如 一名施救者启动急救系统,第二名施救者 开始胸外按压,第三名施救者则提供通气或找到气囊 面罩以进行人工呼吸,第四名施救者找到并准备好除 颤器。

2005(旧):基础生命支持步骤包括一系列连续的评 估和操作。流程图的作用是通过合理、准确的方式展 示各个步骤,以便每位施救者学习、记忆和执行。

2005(旧):未提供有关取消吸氧的具体信息。

SaO2 100% ?

六、特殊复苏环境

2010(新):十五种特殊心脏骤停情况给出特定的治 疗建议。包括哮喘、过敏、妊娠、肥胖症(新)、肺 栓塞 (新)、电解质失衡、中毒、外伤、冻僵、雪崩 (新)、溺水、电击/闪电打击、经皮冠状动脉介入 (PCI)(新)、心脏填塞(新)以及心脏手术(新)。

机械活塞装置 机械活塞装置的病例分析报告了不同的 成功度。在难以一直实施传统心肺复苏的情况下(例如, 做一些辅助检查用于诊断时),可以考虑使用。

五、恢复自主循环后 根据SaO2逐渐降低吸氧浓度

2010(新):恢复循环后,监测SaO2 ,逐步将FiO2 调整 到需要的最低浓度给氧,维持SaO2 ≥94%。

(五)儿童除颤

2010(已修改原建议):对于儿童患者,尚不确定最佳 除颤剂量。有关最低有效剂量或安全除颤上限的研究非 常有限。可以使用 2 —4 J/kg 的剂量作为初始除颤能 量,但为了方便进行培训,可考虑使用 2 J/kg 的首剂 量。对于后续电击,能量级别应至少为 4 J/kg 并可以 考虑使用更高能量级别,但不超过 10 J/kg 或成人最 大剂量。

2005(旧):常规性地给予钙剂并不能改善心脏骤 停的后果。

2010年新版心肺复苏指南

2010年新版心肺复苏指南心脏骤停与心肺复苏心脏骤停一、心脏骤停的定义是指心脏射血功能的突然终止,患者对刺激无意识、无脉搏、无呼吸或濒死叹息样呼吸,如不能得到及时有效的救治,常致患者即刻死亡,即心脏性猝死。

二、心脏骤停的临床表现——三无1、无意识——病人意识突然丧失,对刺激无反应,可伴四肢抽搐;2、无脉搏——心音及大动脉搏动消失,血压测不出;3、无呼吸——面色苍白或紫绀,呼吸停止或濒死叹息样呼吸。

注:对初学者来说,第一条最重要!三、心脏骤停的心电图表现——四种心律类型1、心室颤动:心电图的波形、振幅与频率均不规则,无法辨认QRS波、ST段与T波。

2、无脉性室速:脉搏消失的室性心动过速。

注:心室颤动和无脉性室速应电除颤治疗!3、无脉性电活动:过去称电-机械分离,心脏有持续的电活动,但是没有有效的机械收缩。

心电图表现为正常或宽而畸形、振幅较低的QRS波群,频率多在30次/分以下(慢而无效的室性节律)。

4、心室停搏:心肌完全失去电活动能力,心电图上表现为一条直线。

注:无脉性电活动和心室停搏电除颤无效!四、心脏骤停的治疗——即心肺复苏心肺复苏心肺复苏的五环生存链心肺复苏:是指对早期心跳呼吸骤停的患者,通过采取人工循环、人工呼吸、电除颤等方法帮助其恢复自主心跳和呼吸;它包括三个环节:基本生命支持、高级生命支持、心脏骤停后的综合管理。

《2010 美国心脏协会心肺复苏及心血管急救指南》将心脏骤停患者的生存链由2005年的四早生存链改为五个链环:一、早期识别与呼叫二、早期心肺复苏三、早期除颤/复律四、早期有效的高级生命支持五、新增环节——心脏骤停后的综合管理一、早期识别与呼叫(一)心脏骤停的识别——三无1、无意识判断方法:轻轻摇动患者双肩,高声呼喊“喂,你怎么了?”如认识,可直呼其姓名,如无反应,说明意识丧失。

2、无脉搏判断方法:用食指及中指指尖先触及气管正中部位,然后向旁滑移2-3cm,在胸锁乳突肌内侧触摸颈动脉是否有搏动。

2010心肺复苏指南

建立静脉通道

复苏药物 心电监护 脑复苏

供氧

氧浓度(Fi02)的计算: Fi02(%)=21+4×氧流量(L/min) 供氧方法: 鼻导管;鼻咽插管;面罩;气管内直接给氧 心肺复苏早期建议给100%纯氧,以后根据患 者情况选择低浓度Fi0225~30%,中浓度 Fi0235~55%和高浓度Fi0260%以上

2010(AHA)心肺复苏标准

2010 Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation

内容提要

心跳骤停的表现及原因

第一部分

第二部分

2010年新指南的主要内容

内容提要

心跳骤停的表现及原因

第一部分

第二部分

2010年新指南的主要内容

心搏呼吸骤停诊断

突然意识丧失 大动脉搏动消失

注意:一旦诊断明确就应立即投入抢救,不能因听 心音、测血压、开放静脉通道等操作而耽误时间, 影响抢救效果。

心搏呼吸骤停的原因呼吸Fra bibliotek停心跳骤停、溺水、触电、室息、雷击、外伤、 烟雾吸入、药物过量、脑卒中、会厌炎、 各种原因引起的昏迷、麻醉和手术中的意外事故

心跳骤停

急性冠状脉供血不足、急性心肌梗死、 急性心肌炎、各种心律失常、触电、 各种医疗意外等

内容提要

心跳骤停的表现及原因

第一部分

第二部分

2010年新指南的主要内容

3min 5min 10min 12min 4分钟内进行CPR多能获救 超过12分钟无一存活

获救机会

75% 25% 1% 0.001%

脑复苏(H human)

低温疗法:早期开始,足够低温 脱水疗法:高渗脱水剂、利尿剂、胶体脱水剂 止痉疗法:安定、巴比妥类 血液稀释法:平衡液、低右、自体血浆 钙拮抗剂:尼莫地平、尼卡地平 清除氧自由基:SOD(超氧化歧化酶) 、VitE 抗凝疗法:肝素、华法令 高压氧疗法 促进脑代谢药物:ATP、辅酶A、胞二磷胆碱…

心肺复苏2010指南

碳酸氢钠

• 适应症:

• 有效通气及胸外心脏按压10分钟后,PH 值仍低于 7.2

• 心跳骤停前已存在代谢性酸中毒 • 伴有严重的高钾血症

2010心肺复苏方法

呼救

C (circulation)

心外按压的作用原理:

• 胸泵机制 胸外按压造成胸内压升高,动静脉均承受压 力,但动脉的对抗力大于静脉,在按压时保持开放, 主动脉收缩而将血液泵入大循环;而大静脉则被压陷, 回流停止;放松按压时胸内压下降,静脉回流心脏, 动脉停止泵血,回流的动脉血被主动脉瓣阻挡,血液 不能返流入心脏,部分可从冠状动脉开口流入心脏冠 状动脉 。

电除颤

2010年的指南未对除颤、电复律和起搏进行很大的修 改,强调在给与高质量的心肺复苏同时早期除颤是提 高心肺复苏存活率的关键。

电除颤

• 对一个室颤患者来说,能否成功地被给予电除颤,使 其存活,决定于从室颤发生到进行首次电除颤治疗的 时间。

• 应尽早除颤,5分钟之内开始。除颤延迟1分钟,存活 率降低7—10%,超过10分钟再除,存活率仅为2—5%。

• 心泵机制 超声技术已经证实,在按压时,心脏内的瓣 膜出现与生理情况一致的交替开放与关闭。

定位1

• 两乳头连线中点

定位2

• 定位在剑突上方2横指处

要点

★按压部位 ★姿势 ★按压与放松

间隔相等 ★幅度及频率 ★按压/通气比

率

胸外按压

• 双手指交叉垂直按 压胸骨。

• 心脏按压的 • 频率:至少100次/

分 • 深度:至少5cm

2010心肺复苏方法

2010心肺复苏方法

一手的鱼际处紧贴 在按压部位上,双 手重叠握紧,双臂 绷直,双肩在病人 胸骨上方正中,垂 直向下按压,按压 力量应足以使胸骨 下沉大于5 厘米, 压下后放松,但双 手不要离开胸壁。 反复操作,频率大 于100次/分钟

2010心肺复苏指南

ISSN: 1524-4539Copyright © 2010 American Heart Association. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 0009-7322. Online72514Circulation is published by the American Heart Association. 7272 Greenville Avenue, Dallas, TXDOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.9708892010;122;S640-S656Circulation HoekCallaway, Brett Cucchiara, Jeffrey D. Ferguson, Thomas D. Rea and Terry L. VandenMark S. Link, Laurie J. Morrison, Robert E. O'Connor, Michael Shuster, Clifton W. Marc D. Berg, John E. Billi, Brian Eigel, Robert W. Hickey, Monica E. Kleinman,Neumar, Mary Ann Peberdy, Jeffrey M. Perlman, Elizabeth Sinz, Andrew H. Travers, Farhan Bhanji, Diana M. Cave, Edward C. Jauch, Peter J. Kudenchuk, Robert W.Schexnayder, Robin Hemphill, Ricardo A. Samson, John Kattwinkel, Robert A. Berg, John M. Field, Mary Fran Hazinski, Michael R. Sayre, Leon Chameides, Stephen M. Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care Part 1: Executive Summary: 2010 American Heart Association Guidelines for/cgi/content/full/122/18_suppl_3/S640located on the World Wide Web at:The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is/reprints Reprints: Information about reprints can be found online atjournalpermissions@ 410-528-8550. E-mail:Fax:Kluwer Health, 351 West Camden Street, Baltimore, MD 21202-2436. Phone: 410-528-4050. Permissions: Permissions & Rights Desk, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, a division of Wolters/subscriptions/Subscriptions: Information about subscribing to Circulation is online atPart1:Executive Summary2010American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care John M.Field,Co-Chair*;Mary Fran Hazinski,Co-Chair*;Michael R.Sayre;Leon Chameides; Stephen M.Schexnayder;Robin Hemphill;Ricardo A.Samson;John Kattwinkel;Robert A.Berg;Farhan Bhanji;Diana M.Cave;Edward C.Jauch;Peter J.Kudenchuk;Robert W.Neumar;Mary Ann Peberdy;Jeffrey M.Perlman;Elizabeth Sinz;Andrew H.Travers;Marc D.Berg; John E.Billi;Brian Eigel;Robert W.Hickey;Monica E.Kleinman;Mark S.Link;Laurie J.Morrison; Robert E.O’Connor;Michael Shuster;Clifton W.Callaway;Brett Cucchiara;Jeffrey D.Ferguson;Thomas D.Rea;Terry L.Vanden HoekT he publication of the2010American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care marks the50th anniversary of modern CPR.In1960Kouwenhoven,Knickerbocker,and Jude documented14patients who survived cardiac arrest with the application of closed chest cardiac massage.1That same year,at the meeting of the Maryland Medical Society in Ocean City,MD,the combination of chest compressions and rescue breathing was introduced.2Two years later,in1962, direct-current,monophasic waveform defibrillation was de-scribed.3In1966the American Heart Association(AHA) developed the first cardiopulmonary resuscitation(CPR) guidelines,which have been followed by periodic updates.4 During the past50years the fundamentals of early recogni-tion and activation,early CPR,early defibrillation,and early access to emergency medical care have saved hundreds of thousands of lives around the world.These lives demonstrate the importance of resuscitation research and clinical transla-tion and are cause to celebrate this50th anniversary of CPR. Challenges remain if we are to fulfill the potential offered by the pioneer resuscitation scientists.We know that there is a striking disparity in survival outcomes from cardiac arrest across systems of care,with some systems reporting5-fold higher survival rates than others.5–9Although technology, such as that incorporated in automated external defibrillators (AEDs),has contributed to increased survival from cardiac arrest,no initial intervention can be delivered to the victim of cardiac arrest unless bystanders are ready,willing,and able to act.Moreover,to be successful,the actions of bystanders and other care providers must occur within a system that coordi-nates and integrates each facet of care into a comprehensive whole,focusing on survival to discharge from the hospital.This executive summary highlights the major changes and most provocative recommendations in the2010AHA Guide-lines for CPR and Emergency Cardiovascular Care(ECC). The scientists and healthcare providers participating in a comprehensive evidence evaluation process analyzed the sequence and priorities of the steps of CPR in light of current scientific advances to identify factors with the greatest potential impact on survival.On the basis of the strength of the available evidence,they developed recommendations to support the interventions that showed the most promise. There was unanimous support for continued emphasis on high-quality CPR,with compressions of adequate rate and depth,allowing complete chest recoil,minimizing inter-ruptions in chest compressions and avoiding excessive ventilation.High-quality CPR is the cornerstone of a system of care that can optimize outcomes beyond return of spontaneous circulation(ROSC).Return to a prior quality of life and functional state of health is the ultimate goal of a resuscitation system of care.The2010AHA Guidelines for CPR and ECC are based on the most current and comprehensive review of resuscitation litera-ture ever published,the2010ILCOR International Consensus on CPR and ECC Science With Treatment Recommendations.10 The2010evidence evaluation process included356resuscita-tion experts from29countries who reviewed,analyzed,evalu-ated,debated,and discussed research and hypotheses through in-person meetings,teleconferences,and online sessions(“web-inars”)during the36-month period before the2010Consensus Conference.The experts produced411scientific evidence re-views on277topics in resuscitation and emergency cardiovas-cular care.The process included structured evidence evaluation, analysis,and cataloging of the literature.It also included rigor-The American Heart Association requests that this document be cited as follows:Field JM,Hazinski MF,Sayre MR,Chameides L,Schexnayder SM, Hemphill R,Samson RA,Kattwinkel J,Berg RA,Bhanji F,Cave DM,Jauch EC,Kudenchuk PJ,Neumar RW,Peberdy MA,Perlman JM,Sinz E,Travers AH,Berg MD,Billi JE,Eigel B,Hickey RW,Kleinman ME,Link MS,Morrison LJ,O’Connor RE,Shuster M,Callaway CW,Cucchiara B,Ferguson JD,Rea TD,Vanden Hoek TL.Part1:executive summary:2010American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care.Circulation.2010;122(suppl3):S640–S656.*Co-chairs and equal first co-authors.(Circulation.2010;122[suppl3]:S640–S656.)©2010American Heart Association,Inc.Circulation is available at DOI:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.970889ous disclosure and management of potential conflicts of interest, which are detailed in Part2:“Evidence Evaluation and Man-agement of Potential and Perceived Conflicts of Interest.”The recommendations in the2010Guidelines confirm the safety and effectiveness of many approaches,acknowledge ineffectiveness of others,and introduce new treatments based on intensive evidence evaluation and consensus of experts. These new recommendations do not imply that care using past guidelines is either unsafe or ineffective.In addition,it is important to note that they will not apply to all rescuers and all victims in all situations.The leader of a resuscitation attempt may need to adapt application of these recommenda-tions to unique circumstances.New Developments in Resuscitation ScienceSince2005A universal compression-ventilation ratio of30:2performed by lone rescuers for victims of all ages was one of the most controversial topics discussed during the2005International Consensus Conference,and it was a major change in the2005 AHA Guidelines for CPR and ECC.11In2005rates of survival to hospital discharge from witnessed out-of-hospital sudden cardiac arrest due to ventricular fibrillation(VF)were low,averagingՅ6%worldwide with little improvement in the years immediately preceding the2005conference.5Two studies published just before the2005International Consen-sus Conference documented poor quality of CPR performed in both out-of-hospital and in-hospital resuscitations.12,13The changes in the compression-ventilation ratio and in the defibrillation sequence(from3stacked shocks to1shock followed by immediate CPR)were recommended to mini-mize interruptions in chest compressions.11–13There have been many developments in resuscitation science since2005,and these are highlighted below. Emergency Medical Services Systems andCPR QualityEmergency medical services(EMS)systems and healthcare providers should identify and strengthen“weak links”in the Chain of Survival.There is evidence of considerable regional variation in the reported incidence and outcome from cardiac arrest within the United States.5,14This evidence supports the importance of accurately identifying each instance of treated cardiac arrest and measuring outcomes and suggests additional opportunities for improving survival rates in many communities. Recent studies have demonstrated improved outcome from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest,particularly from shockable rhythms,and have reaffirmed the importance of a stronger emphasis on compressions of adequate rate and depth,allowing complete chest recoil after each compression,minimizing interrup-tions in compressions and avoiding excessive ventilation.15–22 Implementation of new resuscitation guidelines has been shown to improve outcomes.18,20–22A means of expediting guidelines implementation(a process that may take from18 months to4years23–26)is needed.Impediments to implemen-tation include delays in instruction(eg,time needed to produce new training materials and update instructors and providers),technology upgrades(eg,reprogramming AEDs), and decision making(eg,coordination with allied agencies and government regulators,medical direction,and participa-tion in research).Documenting the Effects of CPR Performance by Lay RescuersDuring the past5years there has been an effort to simplify CPR recommendations and emphasize the fundamental importance of high-quality rge observational studies from investiga-tors in member countries of the Resuscitation Council of Asia (the newest member of ILCOR)27,28–30and other studies31,32 have provided important information about the positive impact of bystander CPR on survival after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. For most adults with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest,bystander CPR with chest compression only(Hands-Only CPR)appears to achieve outcomes similar to those of conventional CPR(com-pressions with rescue breathing).28–32However,for children, conventional CPR is superior.27CPR QualityMinimizing the interval between stopping chest compressions and delivering a shock(ie,minimizing the preshock pause) improves the chances of shock success33,34and patient sur-vival.33–35Data downloaded from CPR-sensing and feedback-enabled defibrillators provide valuable information to resus-citation teams,which can improve CPR quality.36These data are driving major changes in the training of in-hospital resuscitation teams and out-of-hospital healthcare providers. In-Hospital CPR RegistriesThe National Registry of CardioPulmonary Resuscitation (NRCPR)37and other large databases are providing new infor-mation about the epidemiology and outcomes of in-hospital resuscitation in adults and children.8,38–44Although observa-tional in nature,registries provide valuable descriptive informa-tion to better characterize cardiac arrest and resuscitation out-comes as well as identify areas for further research. Deemphasis on Devices and Advanced Cardiovascular Life Support Drugs During Cardiac ArrestAt the time of the2010International Consensus Conference there were still insufficient data to demonstrate that any drugs or mechanical CPR devices improve long-term outcome after cardiac arrest.45Clearly further studies,adequately powered to detect clinically important outcome differences with these interventions,are needed.Importance of Post–Cardiac Arrest Care Organized post–cardiac arrest care with an emphasis on multidisciplinary programs that focus on optimizing hemo-dynamic,neurologic,and metabolic function(including ther-apeutic hypothermia)may improve survival to hospital dis-charge among victims who achieve ROSC following cardiac arrest either in-or out-of-hospital.46–48Although it is not yet possible to determine the individual effect of many of these therapies,when bundled as an integrated system of care,their deployment may well improve outcomes.Therapeutic hypothermia is one intervention that has been shown to improve outcome for comatose adult victims of Field et al Part1:Executive Summary S641witnessed out-of-hospital cardiac arrest when the presenting rhythm was VF.49,50Since2005,two nonrandomized studies with concurrent controls as well as other studies using historic controls have indicated the possible benefit of hypo-thermia following in-and out-of-hospital cardiac arrest from all other initial rhythms in adults.46,51–56Hypothermia has also been shown to be effective in improving intact neurologic survival in neonates with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopa-thy,57–61and the results of a prospective multicenter pediatric study of therapeutic hypothermia after cardiac arrest are eagerly awaited.Many studies have attempted to identify comatose post–cardiac arrest patients who have no prospect for meaningful neurologic recovery,and decision rules for prognostication of poor outcome have been proposed.62Therapeutic hypother-mia changes the specificity of prognostication decision rules that were previously established from studies of post–cardiac arrest patients not treated with hypothermia.Recent reports have documented occasional good outcomes in post–cardiac arrest patients who were treated with therapeutic hypother-mia,despite neurologic exam or neuroelectrophysiologic studies that predicted poor outcome.63,64Education and ImplementationThe quality of rescuer education and frequency of retraining are critical factors in improving the effectiveness of resusci-tation.65–83Ideally retraining should not be limited to2-year intervals.More frequent renewal of skills is needed,with a commitment to maintenance of certification similar to that embraced by many healthcare-credentialing organizations. Resuscitation interventions are often performed simulta-neously,and rescuers must be able to work collaboratively to minimize interruptions in chest compressions.Teamwork and leadership skills continue to be important,particularly for advanced cardiovascular life support(ACLS)and pediatric advanced life support(PALS)providers.36,84–89 Community and hospital-based resuscitation programs should systematically monitor cardiac arrests,the level of resuscitation care provided,and outcome.The cycle of measurement,interpretation,feedback,and continuous qual-ity improvement provides fundamental information necessary to optimize resuscitation care and should help to narrow the knowledge and clinical gaps between ideal and actual resus-citation performance.Highlights of the2010GuidelinesThe Change From“A-B-C”to“C-A-B”The newest development in the2010AHA Guidelines for CPR and ECC is a change in the basic life support(BLS)sequence of steps from“A-B-C”(Airway,Breathing,Chest compressions)to “C-A-B”(Chest compressions,Airway,Breathing)for adults and pediatric patients(children and infants,excluding newly borns).Although the experts agreed that it is important to reduce time to first chest compressions,they were aware that a change in something as established as the A-B-C sequence would require re-education of everyone who has ever learned CPR.The 2010AHA Guidelines for CPR and ECC recommend this change for the following reasons:●The vast majority of cardiac arrests occur in adults,and the highest survival rates from cardiac arrest are reported among patients of all ages with witnessed arrest and a rhythm of VF or pulseless ventricular tachycardia(VT).In these patients the critical initial elements of CPR are chest compressions and early defibrillation.90●In the A-B-C sequence chest compressions are often delayed while the responder opens the airway to give mouth-to-mouth breaths or retrieves a barrier device or other ventilation equipment.By changing the sequence to C-A-B,chest compressions will be initiated sooner and ventilation only minimally delayed until completion of the first cycle of chest compressions(30compressions should be accomplished in approximately18seconds).●Fewer than50%of persons in cardiac arrest receive bystander CPR.There are probably many reasons for this,but one impediment may be the A-B-C sequence,which starts with the procedures that rescuers find most difficult:opening the airway and delivering rescue breaths.Starting with chest compressions might ensure that more victims receive CPR and that rescuers who are unable or unwilling to provide ventilations will at least perform chest compressions.●It is reasonable for healthcare providers to tailor the sequence of rescue actions to the most likely cause of arrest.For example,if a lone healthcare provider sees a victim suddenly collapse,the provider may assume that the victim has suffered a sudden VF cardiac arrest;once the provider has verified that the victim is unresponsive and not breathing or is only gasping,the provider should immediately activate the emergency response system,get and use an AED,and give CPR.But for a presumed victim of drowning or other likely asphyxial arrest the priority would be to provide about5cycles(about2minutes)of conventional CPR(including rescue breathing)before ac-tivating the emergency response system.Also,in newly born infants,arrest is more likely to be of a respiratory etiology,and resuscitation should be attempted with the A-B-C sequence unless there is a known cardiac etiology. Ethical IssuesThe ethical issues surrounding resuscitation are complex and vary across settings(in-or out-of-hospital),providers(basic or advanced),and whether to start or how to terminate CPR.Recent work suggests that acknowledgment of a verbal do-not-attempt-resuscitation order(DNAR)in addition to the current stan-dard—a written,signed,and dated DNAR document—may decrease the number of futile resuscitation attempts.91,92This is an important first step in expanding the clinical decision rule pertaining to when to start resuscitation in out-of-hospital car-diac arrest.However,there is insufficient evidence to support this approach without further validation.When only BLS-trained EMS personnel are available, termination of resuscitative efforts should be guided by a validated termination of resuscitation rule that reduces the transport rate of attempted resuscitations without compro-mising the care of potentially viable patients.93Advanced life support(ALS)EMS providers may use the same termination of resuscitation rule94–99or a derived nonvali-dated rule specific to ALS providers that when applied willS642Circulation November2,2010decrease the number of futile transports to the emergency department(ED).95,97–100Certain characteristics of a neonatal in-hospital cardiac arrest are associated with death,and these may be helpful in guiding physicians in the decision to start and stop a neonatal resuscitation attempt.101–104There is more variability in ter-minating resuscitation rates across systems and physicians when clinical decision rules are not followed,suggesting that these validated and generalized rules may promote uniformity in access to resuscitation attempts and full protocol care.105 Offering select family members the opportunity to be present during the resuscitation and designating staff within the team to respond to their questions and offer comfort may enhance the emotional support provided to the family during cardiac arrest and after termination of a resuscitation attempt. Identifying patients during the post–cardiac arrest period who do not have the potential for meaningful neurologic recovery is a major clinical challenge that requires further research.Caution is advised when considering limiting care or withdrawing life-sustaining therapy.Characteristics or test results that are predictive of poor outcome in post–cardiac arrest patients not treated with therapeutic hypothermia may not be as predictive of poor outcome after administration of therapeutic hypothermia. Because of the growing need for transplant tissue and organs,all provider teams who treat postarrest patients should also plan and implement a system of tissue and organ donation that is timely, effective,and supportive of family members for the subset of patients in whom brain death is confirmed or for organ donation after cardiac arrest.Resuscitation research is challenging.It must be scientifically rigorous while confronting ethical,regulatory,and public rela-tions concerns that arise from the need to conduct such research with exception to informed consent.Regulatory requirements, community notification,and consultation requirements often impose expensive and time-consuming demands that may not only delay important research but also render it cost-prohibitive, with little significant evidence that these measures effectively address the concerns about research.106–109Basic Life SupportBLS is the foundation for saving lives following cardiac arrest.Fundamental aspects of adult BLS include immediate recognition of sudden cardiac arrest and activation of the emergency response system,early performance of high-quality CPR,and rapid defibrillation when appropriate.The 2010AHA Guidelines for CPR and ECC contain several important changes but also have areas of continued emphasis based on evidence presented in prior years.Key Changes in the2010AHA Guidelines for CPRand ECC●The BLS algorithm has been simplified,and“Look,Listen and Feel”has been removed from the algorithm.Performance of these steps is inconsistent and time consuming.For this reason the2010AHA Guidelines for CPR and ECC stress immediate activation of the emergency response system and starting chest compressions for any unresponsive adult victim with no breathing or no normal breathing(ie,only gasps).●Encourage Hands-Only(compression only)CPR for the untrained lay rescuer.Hands-Only CPR is easier to perform by those with no training and can be more readily guided by dispatchers over the telephone.●Initiate chest compressions before giving rescue breaths(C-A-B rather than A-B-C).Chest compressions can be started immediately,whereas positioning the head,attaining a seal for mouth-to-mouth rescue breathing,or obtaining or assembling a bag-mask device for rescue breathing all take time.Begin-ning CPR with30compressions rather than2ventilations leads to a shorter delay to first compression.●There is an increased focus on methods to ensure that high-quality CPR is performed.Adequate chest compres-sions require that compressions be provided at the appro-priate depth and rate,allowing complete recoil of the chest after each compression and an emphasis on minimizing any pauses in compressions and avoiding excessive ventilation. Training should focus on ensuring that chest compressions are performed correctly.The recommended depth of com-pression for adult victims has increased from a depth of11⁄2 to2inches to a depth of at least2inches.●Many tasks performed by healthcare providers during resus-citation attempts,such as chest compressions,airway man-agement,rescue breathing,rhythm detection,shock delivery, and drug administration(if appropriate),can be performed concurrently by an integrated team of highly trained rescuers in appropriate settings.Some resuscitations start with a lone rescuer who calls for help,resulting in the arrival of additional team members.Healthcare provider training should focus on building the team as each member arrives or quickly delegat-ing roles if multiple rescuers are present.As additional personnel arrive,responsibilities for tasks that would ordi-narily be performed sequentially by fewer rescuers may now be delegated to a team of providers who should perform them simultaneously.Key Points of Continued Emphasis for the2010AHA Guidelines for CPR and ECC●Early recognition of sudden cardiac arrest in adults is based on assessing responsiveness and the absence of normal breathing.Victims of cardiac arrest may initially have gasping respirations or even appear to be having a seizure. These atypical presentations may confuse a rescuer,caus-ing a delay in calling for help or beginning CPR.Training should focus on alerting potential rescuers to the unusual presentations of sudden cardiac arrest.●Minimize interruptions in effective chest compressions until ROSC or termination of resuscitative efforts.Any unnecessary interruptions in chest compressions(including longer than necessary pauses for rescue breathing)de-creases CPR effectiveness.●Minimize the importance of pulse checks by healthcare providers.Detection of a pulse can be difficult,and even highly trained healthcare providers often incorrectly assess the presence or absence of a pulse when blood pressure is abnormally low or absent.Healthcare providers should take no more than10seconds to determine if a pulse is present. Chest compressions delivered to patients subsequently found not to be in cardiac arrest rarely lead to significant Field et al Part1:Executive Summary S643injury.110The lay rescuer should activate the emergency response system if he or she finds an unresponsive adult. The lay rescuer should not attempt to check for a pulse and should assume that cardiac arrest is present if an adult suddenly collapses,is unresponsive,and is not breathing or not breathing normally(ie,only gasping).CPR Techniques and DevicesAlternatives to conventional manual CPR have been devel-oped in an effort to enhance perfusion during resuscitation from cardiac arrest and to improve pared with conventional CPR,these techniques and devices typically require more personnel,training,and equipment,or apply to a specific setting.Some alternative CPR techniques and devices may improve hemodynamics or short-term survival when used by well-trained providers in selected patients. Several devices have been the focus of recent clinical trials. Use of the impedance threshold device(ITD)improved ROSC and short-term survival when used in adults with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest,but there was no significant improvement in either survival to hospital discharge or neurologically-intact survival to discharge.111One multicenter,prospective,randomized con-trolled trial112,112a comparing load-distributing band CPR(Auto-pulse)with manual CPR for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest demonstrated no improvement in4-hour survival and worse neurologic outcome when the device was used.More research is needed to determine if site-specific factors113or experience with deployment of the device114influence effectiveness of the load-distributing band CPR device.Case series employing me-chanical piston devices have reported variable degrees of success.115–119To prevent delays and maximize efficiency,initial training, ongoing monitoring,and retraining programs should be offered on a frequent basis to providers using CPR devices. To date,no adjunct has consistently been shown to be superior to standard conventional(manual)CPR for out-of-hospital BLS,and no device other than a defibrillator has consistently improved long-term survival from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest.Electrical TherapiesThe2010AHA Guidelines for CPR and ECC have been updated to reflect new data on the use of pacing in bradycar-dia,and on cardioversion and defibrillation for tachycardic rhythm disturbances.Integration of AEDs into a system of care is critical in the Chain of Survival in public places outside of hospitals.To give the victim the best chance of survival,3actions must occur within the first moments of a cardiac arrest120:activation of the EMS system,121provision of CPR,and operation of a defibrillator.122One area of continued interest is whether delivering a longer period of CPR before defibrillation improves out-comes in cardiac arrest.In early studies,survival was im-proved when1.5to3minutes of CPR preceded defibrillation for patients with cardiac arrest ofϾ4to5minutes duration prior to EMS arrival.123,124However,in2more recent randomized controlled trials,CPR performed before defibril-lation did not improve outcome.125,126IfՆ2rescuers are present CPR should be performed while a defibrillator is being obtained and readied for use.The1-shock protocol for VF has not been changed. Evidence has accumulated that even short interruptions in CPR are harmful.Thus,rescuers should minimize the interval between stopping compressions and delivering shocks and should resume CPR immediately after shock delivery. Over the last decade biphasic waveforms have been shown to be more effective than monophasic waveforms in cardio-version and defibrillation.127–135However,there are no clin-ical data comparing one specific biphasic waveform with another.Whether escalating or fixed subsequent doses of energy are superior has not been tested with different wave-forms.However,if higher energy levels are available in the device at hand,they may be considered if initial shocks are unsuccessful in terminating the arrhythmia.In the last5to10years a number of randomized trials have compared biphasic with monophasic cardioversion in atrial fibrillation.The efficacy of shock energies for cardioversion of atrial fibrillation is waveform-specific and can vary from120to 200J depending on the defibrillator manufacturer.Thus,the recommended initial biphasic energy dose for cardioversion of atrial fibrillation is120to200J using the manufacturer’s recommended setting.136–140If the initial shock fails,providers should increase the dose in a stepwise fashion.Cardiover-sion of adult atrial flutter and other supraventricular tachycardias generally requires less energy;an initial energy of50J to100J is often sufficient.140If the initial shock fails,providers should increase the dose in a stepwise fashion.141Adult cardioversion of atrial fibrilla-tion with monophasic waveforms should begin at200J and increase in a stepwise fashion if not successful. Transcutaneous pacing has also been the focus of several recent trials.Pacing is not generally recommended for pa-tients in asystolic cardiac arrest.Three randomized controlled trials142–144indicate no improvement in rate of admission to hospital or survival to hospital discharge when paramedics or physicians attempted pacing in patients with cardiac arrest due to asystole in the prehospital or hospital(ED)setting. However,it is reasonable for healthcare providers to be prepared to initiate pacing in patients with bradyarrhythmias in the event the heart rate does not respond to atropine or other chronotropic(rate-accelerating)drugs.145,146 Advanced Cardiovascular Life SupportACLS affects multiple links in the Chain of Survival,including interventions to prevent cardiac arrest,treat cardiac arrest,and improve outcomes of patients who achieve ROSC after cardiac arrest.The2010AHA Guidelines for CPR and ECC continue to emphasize that the foundation of successful ACLS is good BLS, beginning with prompt high-quality CPR with minimal interrup-tions,and for VF/pulseless VT,attempted defibrillation within minutes of collapse.The new fifth link in the Chain of Survival and Part9:“Post–Cardiac Arrest Care”(expanded from a subsection of the ACLS part of the2005AHA Guidelines for CPR and ECC)emphasize the importance of comprehensive multidisciplinary care that begins with recognition of cardiac arrest and continues after ROSC through hospital discharge and beyond.Key ACLS assessments and interventions provide anS644Circulation November2,2010。

2010年新版心肺复苏指南

2010年新版心肺复苏指南心脏骤停与心肺复苏心脏骤停一、心脏骤停的定义是指心脏射血功能的突然终止,患者对刺激无意识、无脉搏、无呼吸或濒死叹息样呼吸,如不能得到及时有效的救治,常致患者即刻死亡,即心脏性猝死。

二、心脏骤停的临床表现——三无1、无意识——病人意识突然丧失,对刺激无反应,可伴四肢抽搐;2、无脉搏——心音及大动脉搏动消失,血压测不出;3、无呼吸——面色苍白或紫绀,呼吸停止或濒死叹息样呼吸。

注:对初学者来说,第一条最重要!三、心脏骤停的心电图表现——四种心律类型1、心室颤动:心电图的波形、振幅与频率均不规则,无法辨认QRS波、ST段与T波2、无脉性室速:脉搏消失的室性心动过速。

注:心室颤动和无脉性室速应电除颤治疗!3、无脉性电活动:过去称电-机械分离,心脏有持续的电活动,但是没有有效的机械收缩。

心电图表现为正常或宽而畸形、振幅较低的QRS波群,频率多在30次/分以下(慢而无效的室性节律)。

4、心室停搏:心肌完全失去电活动能力,心电图上表现为一条直线。

注:无脉性电活动和心室停搏电除颤无效!四、心脏骤停的治疗——即心肺复苏心肺复苏心肺复苏的五环生存链心肺复苏:是指对早期心跳呼吸骤停的患者,通过采取人工循环、人工呼吸、电除颤等方法帮助其恢复自主心跳和呼吸;它包括三个环节:基本生命支持、高级生命支持、心脏骤停后的综合管理。

《2010美国心脏协会心肺复苏及心血管急救指南》将心脏骤停患者的生存链由2005 年的四早生存链改为五个链环:一、早期识别与呼叫二、早期心肺复苏三、早期除颤/复律四、早期有效的高级生命支持五、新增环节——心脏骤停后的综合管理一、早期识别与呼叫(一)心脏骤停的识别——三无1、无意识判断方法:轻轻摇动患者双肩,高声呼喊“喂,你怎么了?”如认识,可直呼其姓名,如无反应,说明意识丧失。

2、无脉搏判断方法:用食指及中指指尖先触及气管正中部位,然后向旁滑移2-3cm,在胸锁乳突肌内侧触摸颈动脉是否有搏动。

2010AHA CPR

福建省级机关医院急诊科

孕妇复苏体位摆放方法

2010心肺复苏指南

福建省级机关医院急诊科

心肺复苏从ABC变为CAB

2010心肺复苏指南

C:高质量的胸外按 压 A:开放气道 B:人工呼吸

福建省级机关医院急诊科

未开放的气道

2010心肺复苏指南

昏迷病人舌和

会厌阻塞上呼 吸道

未

福建省级机关医院急诊科

是整个急救生命链

的开始

但对于溺水或气 道异物阻塞的患者, 应先给予5个循环的 CPR后再呼救

福建省级机关医院急诊科

并取得AED

2010心肺复苏指南

取得AED,尽早

除颤

除颤1次,立即 开始按压,尽可 能缩短除颤前后 按压的中断!

福建省级机关医院急诊科

2010心肺复苏指南

弱化脉搏的检查(对专业人员) 摆放正确的复苏体位

福建省级机关医院急诊科

2010心肺复苏指南

心脏骤停是一个过程,实际上分几个阶段. 根据魏斯费尔德 (Weisfeld)及贝克尔(Becker)倡导的室颤诱发心脏停搏(VFCA)的三个时效性时期。 第一期为“电生理期”,在心脏骤停的最初4-5分钟,约有 70% 是 VF,此期最主要的救治措施是除颤。根据这一构想,应在飞机上 等公共场所配备AED装置,并鼓励公众应用,以及时挽救生命。 第二期为 “循环期”,从4- 5 min持续到10 min,此时纤颤的心肌 已消耗了许多的能量(ATP) 储备,并且左心室的血液相对流空. 在 这种情况下除颤的结果常常导致心脏停搏或无脉性电活动 (PEA), 因而应在除颤前和后立即进行胸腔按压,通过胸部按 压使脑及冠脉有足够血流灌注,这对神经功能的保护极为重要。 第三期为 “代谢期,常始于发病” 10 min后, 室颤波消失,目前几 乎没有针对该期的有效治疗措施。

2010国际心肺复苏指南-

2010版CPR最主要改动

4、BLS其他注意事项 保证每次按压后胸部回弹 强化按压的重要性,按压间断时间不超过5s 避免过度通气 取消“看、听和感觉呼吸” 心脏按压的速度与深度 进一步强调实施高

强调黄金4分钟

心跳呼吸骤停的诊断

• 病人意识突然丧失,昏倒于任何场合; • 大动脉无搏动; • 呼吸停止; • 面色苍白或紫绀,瞳孔散大; • 心电图:一直线、心室颤动和心电机械分

离。

心脏骤停的类型

1、心室颤动 2、无脉性室速 3、心脏停搏 4、心电机械分离

CPR的三个阶段

基本生命支持(BLS) 进一步生命支持(ACLS) 延续生命支持(PLS)

三个阶段——核心技术

·第一阶段——第一个CABD

(基础生命支持,BLS) 公众普及

C心脏按压 A开放气道 B人工呼吸 D除颤

·第二阶段——第二个ABCD

(进一步生命支持,ACLS) 专业人员普及

A 气管插管

B 正压通气

C 心律血压药物

D 鉴别诊断

·第三阶段——(延续生命支持PLS,脑保护)

复苏后的处理与评估,进一步的病因治疗

质量的心肺复苏

2010版CPR最主要改动

5、不再强调脉搏检查: 如果在 10 秒钟之内没有触摸到脉搏或

不确定已触摸到脉搏,即可开始胸外按压 。要确定是否有脉搏可能比较困难,特别 是在急救时,研究显示医务人员和非专业 施救者都不能可靠地检测到脉搏。

2010版CPR最主要改动

6、单纯胸外按压:在施救者未经培训或经过 培训但不熟练的情况下。

2010版CPR最主要改动

2010年AHA心肺复苏指南 - 由ABC到CAB意义和启示 社区医生版-文档资料

2024/3/15

4

根据2005年指南如何进行CPR?

• A(airway):开放气道 • B(breathing):人工呼吸 • C(circulation):人工循环,即胸外按压

我们熟悉的A-B-C顺序在2010年 指南中已作出重大调整!!!

2024/3/15

5

2010年CPR指南:C-A-B

2024/3/15

11

为什么“C frist”

• 胸外按压几乎可以立即开始,而摆好头部位置并尽可能密 封以进行口对口或气囊面罩人工呼吸的过程则需要一定时 间

• 如果有两名施救者在场,可以减少开始按压的延误:第一 名施救者开始胸外按压,第二名施救者开放气道并准备好 在第一名施救者完成第一轮 30 次胸外按压后立即进行人 工呼吸

2024/3/15

27

生命救治流程

2024/3/15

28

小结

• 新指南强调首先尽快开始“C”:胸外按压 • 新指南强调快速用力有效的“C”:胸外按压 • 新指南简化流程,易于操作,鼓励非专业人员参与仅

有“C”:胸外按压的CPR(专业人员和医务人员仍应该 在C-A-B顺序下尽快开始人工呼吸) • 新指南强调综合的心脏骤停后治疗 • 新指南弱化对于脉搏的评估

19

实践高质量的CPR

• 按压方法 按压时上半身前倾,腕、 肘、肩关节伸直,以髋关 节为轴,垂直向下用力, 借助上半身的体重和肩臂 部肌肉的力量进行按压

2024/3/15

20

实践高质量的CPR

• 弱化检查脉搏 • 研究显示非专业和医务人员检查脉搏都会化去较长时间 • 非专业人员发现成人突然意识不清、对呼叫无反应可以假

• 在大多数研究中,给予更多按压可提高存活率,而减少按 压则会降低存活率。进行足够胸外按压不仅强调足够的按 压速率,还强调尽可能减少中断这一关键步骤的次数

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

施救者

每个人都可以成为心脏骤停患者的救命者。CPR的方法和应用取决于施救者的培训、经验和 自信心。

胸外按压是CPR的基础(见图2)。所有施救者,不管是否受过培训,都应给所有心脏骤停患 者施以胸外按压。由于胸外按压的重要性,不论心脏骤停患者的年龄有多大,胸外按压应是给所

Translated by Li-Daohai

第 6 页 共 83 页

2010 AHA 心肺复苏指南(实用中文版)

图2.CPR的组成成分(building blocks)

高度

训练

多名施救者协同 CPR

施救者熟练程度

人工呼吸

30:2CPR

未经 训练

胸外按压

单纯胸外按压 CPR

有患者施行CPR的起始动作。有能力的施救者应该增加通气联合胸外按压。受过专业培训的一起 抢救的施救者应该互相协调分工,以团队协作的方式实施胸外按压和通气。

图1.生存链。生存链的各环节是:立即识别和启动、早期CPR、迅速除颤、有效的高级 生命支持和综合的心脏骤停后治疗。

能有效完成这些链环(环节)的急救系统能使目击的室颤型心脏骤停的存活率几乎达到50%。 然而,在大多数急救系统里存活率更低,提示有机会通过仔细检查各环节和加强薄弱环节进行提 高。各个环节相互依靠,每个环节的成功取决于前面环节的效果。

第 7 页 共 83 页

2010 AHA 心肺复苏指南(实用中文版)

图3 成人基础生命支持简化流程

注:图3转载自2010 AHA CPR和ECC指南摘要(中文版)。

施救者应该着重进行高质量CPR: l 给予足够频率的胸外按压(至少100次/分钟); l 给予足够深度的胸外按压:

·成人:按压深度至少2英寸(5cm); ·婴儿和儿童:深度至少达到胸廓前后径的1/3,或婴儿1.5 英寸(4cm),儿童2英寸(5cm); l 每次按压后让胸廓完全回弹; l 尽量减少按压的中断; l 避免过度换气;

当取来AED/除颤器时,如果可能则使用电极帖,不要中断胸外按压,打开AED“开”关。AED 将分析心律,指示施救者进行电击(即除颤)或继续CPR。

如果得不到AED/除颤器,继续CPR不要中断,直到更多有经验的施救者接手。

识别和启动急救反应

迅速启动急救和开始CPR需要快速识别心脏骤停。心脏骤停患者没有反应。没有呼吸或呼吸 不正常。心脏骤停后早期濒死喘息(agonal gasps)常见,会与正常呼吸混淆。即使是受过培训 的施救者单独检查脉搏也常不可靠,而且需要额外的时间。因此,假如成年患者无反应、没有呼 吸或呼吸不正常(即只有喘息),施救者应当立即CPR。不再推荐“看、听和感觉呼吸”辅助识 别(诊断)的方法。

急救调度员能够和应该协助判断和指导以开始CPR。医护人员可结合其他信息帮助识别心脏 骤停。

胸外按压

迅速开始有效的胸外按压是心脏骤停复苏的基本内容。CPR通过给心脏和大脑提供血液循环 增加患者的存活机会。不管施救者的技术水平、患者的特征和可用的资源如何,施救者都应该对 所有心脏骤停患者施行胸外按压。

Translated by Li-Daohai

在美国和加拿大,急救医疗系统(EMS)治疗的院外心脏骤停的发生率估计是大约 50~55 / 100000人/年,这些患者25%是无脉性室性心律失常。估计院内心脏骤停发生率是3~6/1000入院

Translated by Li-Daohai

第 5 页 共 83 页

2010 AHA 心肺复苏指南(实用中文版)

一旦建立高级气道,医务人员将按每6至8秒给予1次通气(每分钟8至10次呼吸)的规则的速 率进行通气,可不间断地进行胸外按压。

在翻译和制作过程中,译者力求采用规范统一词汇,以增加可读性。但笔者发 现国内对复苏医学部分名词的中文翻译很不统一或规范。例如,“Cardiac arrest”在 国内 5 年制和 7、8 年制人卫版《内科学》统编教材和《中华心律失常学杂志》都译 为心脏骤停,这基本代表国内心血管专家的用法;而国内急诊医学专家、《中华急诊 医学杂志》主要采用心搏骤停,也有用心跳骤停或心脏停搏;全国科技名词审定委 员会则译为心脏停搏。类似还有 Asystole,国内上述这些专家或单位分别采用了心 室停搏、心室停顿、心室静止、心脏停搏和心搏停止等多种用法,第 7 版《内科学》 甚至在同一章节中采用了三种用法。类似词汇还有多个。因此笔者在翻译过程中对 此深感困惑和为难。为减少误解,在翻译过程中,笔者尽量采用大家熟悉的与国内 教科书一致的统一的词汇,并参考全国科技名词审定委员会网站公布的名词,另外 在部分中文词汇后面附有英文。在此,笔者强烈呼吁相关部门组织国内的心血管专 家、急诊医学专家和科技名词审定委员会的医学专家,共同一起对复苏医学的部分 名词重新进行审定或修订,以规范和统一这些名词。也希望专家们在编写教科书时 能更加严谨、仔细和规范。

2010 AHA 心肺复苏指南

(实用中文版)

主译 李道海 审校 梁子敬

2010 AHA 心肺复苏指南(实用中文版)

2010 AHA 心肺复苏指南

(实用中文版)

翻译人员

李道海(lidaohai@) 彭 翔(drpx@) 曾量波(drzenglb@)

审校

李道海 梁子敬

Translated by Li-Daohai

第 4 页 共 83 页

2010 AHA 心肺复苏指南(实用中文版)

第 1 部分 CPR概述

心肺复苏(Cardiopulmonary resuscitation,CPR)是一系列改善心脏骤停后存活机会的救 命措施。虽然 CPR 的最佳方法根据施救者、患者和可利用资源可以有所不同,但是,根本的挑战 仍然是:怎样才能获得早期和有效的 CPR。考虑到这种挑战,施救者识别骤停和迅速采取行动仍 然是《2010 AHA CPR 和 ECC 指南》优先考虑的。本章描述了心脏骤停流行病学概述、生存链每 一环节背后的原则、CPR 核心组成部分的概要和《2010 AHA CPR 和 ECC 指南》提高 CPR 质量的方 法(见表 1)。本章的目的是:把复苏理论和临床实践相结合以改善 CPR 的结果。

如果有多位施救者,应该每2分钟轮换一次。

气道管理和通气

开放气道(用仰头抬颏法或托颌法)随即进行人工呼吸能改善氧合和通气。然而,这些动作 技术上存在挑战,需要中止胸外按压,尤其对于未受过培训的单一施救者。因此,未受过培训的 施救者将进行Hands-Only(单纯胸外按压)CPR(即进行胸外按压而不进行人工呼吸);而有能力 的单一施救者应该开放气道,进行人工呼吸同时给予胸外按压。如果患者高度可能是由于窒息引 起心脏骤停(例如婴儿、儿童或淹溺患者),应给予通气。

温馨提示:本中文版是个人兴趣所译,供日常学习及参考使用。 请勿用于商业目的和制作各类出版物。AHA 拥有本指南的版权,如 需转载请注明出处。

Translated by Li-Daohai

第 2 页 共 83 页

2010 AHA 心肺复苏指南(实用中文版)

前言

《2010 AHA 心肺复苏指南》(实用中文版)是基于个人兴趣所译和制作。本指 南由与成人心肺复苏直接相关的 6 个部分组成,包括心肺复苏概述、成人基础生命 支持、电学治疗、CPR 技术和设备、成人高级生命支持以及心脏骤停后治疗。这些 内容原文取自最近发表在《Circulation》的“2010 AHA Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care”,然后经译者翻译成中文,整理后取 名《2010 AHA 心肺复苏指南》(实用中文版)。本指南未包括心血管急救和儿童心肺 复苏部分,欲进一步了解指南其他内容,请参阅原文或其他中文版指南。

当遇到突然心脏骤停的成年患者时,单个施救者必须首先根据没有反应和没有正常呼吸来识 别患者发生了心脏骤停。识别后施救者应立即启动急救反应系统,如果可行拿取AED/除颤器,并 从胸外按压开始进行CPR。如果AED不在附近,施救者应该直接进行CPR。如果有其他施救者,第 一位施救者应该指挥他们启动急救反应系统和拿取AED/除颤器;第一位施救者应立即开始CPR。

表1. 成人、儿童和婴儿基础生命支持关键步骤的总结

注:表1转载自2010 AHA CPR和ECC指南摘要(中文版)。

流行病学

尽管预防方面取得重要进展,但是心脏骤停(cardiac arrest)仍然是一个重大的公共健康问 题,是世界上很多地区的主要死因。心脏骤停可发生在院内和院外。在美国和加拿大,每年大约 有35万人(约有一半是在院内)发生心脏骤停和接受复苏。这个数字不包括发生心脏骤停但没有 进行复苏患者的数量。虽然进行复苏并不总是合适(或正确),但是因为没有进行合适的复苏而 会失去很多生命和生存年限(life-years)。

者,同样,大约25%患者是无脉性室性心律失常。表现心室颤动(VF)或无脉性室性心动过速(VT) 的心脏骤停患者比心室停搏(asystole)或无脉电活动患者有更好的预后。

绝大部分心脏骤停患者是成年人,但是美国和加拿大每年有数千婴儿和儿童发生院内或院外 心脏骤停。

心脏骤停仍然是患者过早死亡的普遍原 Nhomakorabea,在存活率方面不断的少许改善能导致每年成千上 万的生命获救。

患者

大多数成人的心脏骤停突然发生,由原发心脏疾病引起;因此,由胸外按压产生的血液循环 是最重要的。相反,儿童的心脏骤停多数是由窒息引起,要达到最佳效果,需要同时进行通气和 胸外按压。因此,人工呼吸对于心脏骤停的儿童比成人更重要。