高级英语(第三版)第一册第八课 Three cups of tea

Three Cups of Tea

Three Cups of Tea by Greg MortensonThe title of my book Three Cups of Tea comes from a Pakistani proverb that says when you share the first cup of tea you’re a stranger, with the second cup you are a friend, and with the third cup you become family. I picked the title in honor of Haji Ali, the Pakistani village chief who told me we would need three cups of tea if we wanted to accomplish things together.In 1993, after a failed attempt to climb K2, I became separated from the group as we descended. After walking 58 miles, I wandered into a little village called Korphe. There I me Haji Ali, a stout, elderly man with a silver beard. I hadn’t taken a bath in 84 days, and my pants were ripped. He said, “Welcome to our village, but you do need to wash up a little, son, before you come to my house for tea.”I stayed with Haji Ali that night and returned later to spend more time in Korphe. One day Haji Ali took me behind the village, where 82 children were sitting in the dirt –four girls, 78 boys – and most of the kids were writing with sticks in the dirt. This was their school. A young girl came up to me and said, “Would you help us build a school?” I said, “I promise I’ll build a school for you.” Little did I know that promise would change my life forever.I had to raise $12,000 to build the school, and I had no clue how to do it. When I returned to the United States, I went to the local library and looked up the names of 580 celebrities. Then I typed 580 letters: “Dear Michael Jordan,”“Dear Sylvester Stallone.”Guess what happened? Nothing. At Christmastime I got one check back – from Tom Brokaw for $100.I kept working; I was determined to get the school built. One day in 1994, my mother invited me to come to the elementary school in Wisconsin where she was principal. When I got ready to leave, a fourth grader named Jeffrey came up to me. He said, “I have a piggy bank at home, and I’m going to help you.” I didn’t think anything of it – what can a fourth grader do? Six weeks later, Jeffrey and his classmates had raised 62,340 pennies. It wasn’t celebrities, it wasn’t adults, but children who reached out to children halfway around the world.I returned to Korphe a couple of times while we were trying to build the school. Over those years I spent a lot of time with Haji Ali.Haji Ali loved to read in the evening. He would sit on his bed and hold books close to his eyes. But he read only two books; he read the Qur’an and he read Persian poetry. Often when he read I noticed he was quite sad and had a tear in his eye. So one day I asked Haji, “Why are you sad when you read?”He said, “Greg, actually I don’t know how to read. I’ve memorized these books.” He said, “It’s my life’s greatest sadness that I never learned how to read and write. It’s my life’s greatest hope that my children and my grandchildren can learn to read and write.”Well, we got the school built. And then we kept going. Since 1996, when the Korphe School was completed, we have established more than 100 schools in Afghanistan and Pakistan.In 2001 Haji Ali died. I visited his grave in Korphe, and I thought, “How can I go on?”This man had become my mentor and my guide. And then I remembered that he had said, “When you are standing here and I am in the ground, listen to the wind.” So I listened to the wind, and in the wind I heard the voices of the children in the school, and I realized his legacy and vision had come true, through the education of his children.。

《三杯茶 Three Cups Of Tea》

内容简介

在巴基斯坦的世界中,‚三杯茶‛,是巴尔蒂人交 朋友的方式。 第一杯茶,你是陌生人; 第二杯茶,你是我们的宾客; 第三杯茶,你是我们的家人,我们愿意为你做任何 事,甚至是死。 当摩森顿于攀登K2峰迷路,科尔飞村居民拯救了他 的生命。当地的居民生活艰困,糖是如此稀少珍贵,他 们却为他煮了甜茶,让他恢复力气。此后,从第一杯茶 到第三杯茶,从陌生人到愿意以生命守护彼此,‚三杯 茶‛代表的是他们之间珍贵的信任,更是一生的承诺, 也是一个旅人,改变世界的开始。

K2 乔戈里峰

乔戈里峰,为世界第二高峰,海拔8611米,仅次于 珠穆朗玛峰。 位于东经76.5度,北纬35.9度地处中国新疆叶城县 与巴控克什米尔之界山。 中国方面正式名称「乔戈里」(Qogir,衍生自 Chogori)为塔吉克语「高大雄伟」之意。而K2是国际 上最常见的名称,源自1856年西方探险队首次考察此地 区时,标出了喀喇昆仑山脉自西向东的5座主要山峰ー 各以K1至K5命名。其余四座分别是玛夏布洛姆峰(K1), 布洛阿特峰(K3),加舒尔布鲁木II峰(K4)与加舒尔 布鲁木I峰(K5)。

在过去的十二年,巴基斯坦、阿富汗及西藏山区, 六十所学校陆续成立,最特别的是,这些学校让原本无 法上学的女孩开始接受教育。摩顿森守护妹妹的信念, 改变了一群女孩的生命,是她们不再藏匿于面纱之后, 有勇气面对世界,甚至拥有改变世界的能力。 当我们怀疑,一个人的力量是否真的能改变世界时, 摩顿森做到了。为了坚持理想,即使受到恋人的遗弃、 社会的漠视、巴提人的拐骗,即使与妻儿分隔两地、被 军阀囚禁,即使遭逢美国911事件、美国轰炸阿富汗, 在悲伤、沮丧、孤独与滨临死亡之时,他从来没有遗忘 他的承诺,他愿意用生命去化解世界上最大的仇恨。

摩顿森回到柏克莱一个月后,收到母亲寄来的一 封信,她在信中解释学生们自发性地发起了「一分钱 捐给巴基斯坦」活动,一分一分钱地装满了一个两加 仑的垃圾桶--他们总共募集了六万二千三百四十五 个一分钱。当他将母亲寄来的六百二十三元四十五分 美金支票存进银行,摩顿森觉得幸运之神终于眷顾他 了。「孩子们跨出了帮助盖校的第一步。」摩顿森说, 「而他们所用的,基本上是社会上被认为最没价值的 「一分钱」。但在海外,这一分一分钱聚集起来可以 移动大山。」 六个月后,他终于收到回信,一张一万二千美金 的支票,足够盖第一间学校,他终于可以前往阿富汗 盖学校,然而,困难才正要开始。因为,当地连运输 建校材料的「桥」都没有,摩顿森盖学校之前,必须 先架上一座桥……。

高级英语第三版第八课三杯茶翻译.docx

三杯茶(节选)-------- 格雷格 ?摩顿森,戴维?奥利弗 ?瑞林第十二章哈吉?阿里的教诲如果相信喜马拉雅山脉的一种“原始”文化能对我们工业化社会有任何教益,这或许似乎有些荒唐。

但是我们对成功的未来的追求需要不断反复地求助于我们之间与地球之间一种古老的联系,即古老的文化从未抛弃的一种互相联系。

-----海伦娜诺 ?伯格 ?霍奇①这些石头看上去更像是古老的废墟而不是新学校的建筑石材。

秋天的天气晴好无比,科尔飞乔戈里峰金字塔形的山峰高高地耸立着。

摩顿森站在布拉尔度河岸边一块平坦的高地上,眼前的景象使他感到沮丧。

②前一个冬天,当摩顿森离开科尔飞村时,他把固定帐篷用的木桩打进冻土,并系上红蓝两色编制的尼龙绳,来标记他心中有五间房子的学校的范围。

他留给哈吉?阿里足够的现金用来雇佣河流下游村庄的民工帮助开采和运送石料。

当他到达时,他希望看到至少学校的地基已经挖好。

然而事与愿违,他看见田地里推着两大堆石料。

③与哈吉?阿里视察工地时,摩顿森尽量掩饰他的失望之情。

他到达这里时事十月中旬,大约一个月前他告诉哈吉? ?阿里等他。

他想,这个星期他们应该在砌墙才对。

摩顿森按捺着怒气自责不已。

他不可能老是反反复复地到巴基斯坦来。

既然已经结了婚,他需要一个稳定的职业。

他想把学校盖好,这样他才可以规划将来一生从事是什么样的工作。

现在,冬天将再一次延误学校的建造。

摩顿森生气地踢起地上的一块石头。

4“怎么了?”哈吉?阿里用巴尔蒂语关切地问道。

“你的样子好像一头角斗的年轻公羊。

”5 摩顿森深深吸了一口气,反问对方:“为什么还没有开工?”6“格雷格医生,你回你的村子以后,我们讨论你的计划。

”哈吉?阿里说。

“我们一致认为,浪费你的钱雇佣芒均和阿斯科尔两个村子的懒汉是件愚蠢的事。

他们知道,学校正在由富有的外国人建造,他们就会出工不出力,争吵不休。

所以我们自己开采石料。

这项工作占用了整个夏天,因为村民不得不去当脚夫。

不过不用担心,你留下的钱还安安全全地锁在我家里呢。

高级英语 three cups of tea

Three Cups of Tea

Advanced English Book 1

Part 3 (paras. 23-37) This part introduces details about the school construction. The involvement in the construction enables Mortenson to have a better understanding of the local culture and their spiritual life.

Three Cups of Tea

Advanced English Book 1

Instead of arriving in Askole, where his porters a66waited, he came across Korphe, a small village built on a shelf jutting out from a canyon. He was greeted and taken in by the chief elder, Haji Ali of Korphe. To repay the remote community for their hospitality, Mortenson gave away his climbing supplies as gifts and helped to cure ill villagers. Meanwhile, he promised to build a school for the village.

three cups of tea 三杯茶的英文介绍

• Building the schools requires a number of sacrifices from Mortenson and from the local villagers involved. When Mortenson begins his Korphe project, he sells all his possessions—including cherished books and his grandmother’s car. • Even after becoming successful, Mortenson continues to make sacrifices, taking as little money as possible from the CAI and leaving his family alone for months at a time.

批注本地保存成功开通会员 you share tea with a Balti, you are a stranger.

• The second time you take tea, you are an honored guest. • The third time you share a cup of tea, you become family, and for our family we are prepared to do anything —even die.

• The main character is the mountain hiker Greg Mortenson who climbed K2, the world’s second highest mountain, in the Karakoram Range of northern Pakistan. • He was planning to lay his deceased sister Christa’s amber necklace on the summit of K2. • After more than 70 days on the mountain, Greg and three other climbers had their ascent interrupted by the need to complete a 75-hour life-saving rescue of a fifth climber. • After getting lost during his descent, he became weak and exhausted, and by chance alone. He came across Korphe, a small village built on a shelf jutting out from a canyon. • He was greeted and taken in by the chief elder of Korphe, Haji Ali. And he was taken care of by people there.

高级英语(1)第三版Lesson8ThreeCupsofTea翻译答案

高级英语(1)第三版Lesson8ThreeCupsofTea翻译答案Lesson 8 Three Cups of Tea (Excerpts)Translation1.当他被人从河里救出来时,几乎半死不活了。

2.在我上一次访问这个村子时,那里还没有学校。

现在一所小学已经屹立在山顶上。

3.他恢复了知觉,睁开眼睛,想努力搞清楚发生了什么事,为什么他躺在那里。

4.展览会上最吸引观众的是新奇的电子产品。

5.温室里的许多奇花异草引起大家争先拍照。

6.这位作家出生于一个大家庭,他的家谱可以追溯到十五代以前。

7.当地少数民族在杀牲口前,先要举行一番宗教仪式,请求上苍允许他们杀生。

8.村民们贫穷的事实并非说明他们就愚昧无知。

9.志愿者们的共同努力使得项目开展起来了。

10.登山者感到头晕,几乎站立不住,一是由于过度疲劳,也是因为太饥饿了。

参考译文1.When he was saved from the river, he was more dead than alive.2.On my previous visit, there was no school, but now one stands on the mountain.3.As he came to himself, he opened his eyes, trying to figure out waht had happened and why he was lying there.4.At the exhibition there were many novel electronic products that attracted the attention of visitors.5.People were keen on taking pictures of the many exotic flowers and plants in the greenhouse.6.This writer came from a large, prominent family whose genealogy streches back fifteen generations.7.Before killing an animal, the indigenous ethnic people usually hold rituals to request permission from their God.8.The fact that the villagers are poor doesn’t mean they are ignorant or stupid.9.The volunteers made concerted efforts and got the project off the ground.10.The climber felt so dizzy that he could hardly stand up, as much from over exhaustion as from starvation.。

三杯茶高级英语读后感300字

三杯茶高级英语读后感300字英文回答:After reading "Three Cups of Tea", I was truly inspired by the story of Greg Mortenson and his mission to build schools in remote areas of Pakistan and Afghanistan. The book highlighted the power of education in transforming lives and promoting peace in regions plagued by conflict and poverty.One of the main takeaways from the book for me was the importance of perseverance and determination in the face of adversity. Despite facing numerous challenges and setbacks, Mortenson never gave up on his goal of providing education to children in need. This reminded me of the saying, "Where there's a will, there's a way." It's a testament to thefact that with hard work and dedication, anything is possible.Another aspect of the book that resonated with me wasthe idea of making a difference one person at a time. Mortenson started with a simple act of kindness towards a village in need, and that small gesture snowballed into a movement that impacted thousands of lives. It goes to show that even the smallest actions can have a ripple effect and create positive change in the world.Overall, "Three Cups of Tea" left me feeling inspired and motivated to make a difference in my own community. It reminded me that even the most daunting challenges can be overcome with perseverance, compassion, and a willingness to take action.中文回答:读完《三杯茶》,我深受Greg Mortenson的故事所感染,他的使命是在巴基斯坦和阿富汗偏远地区建立学校。

Three Cups of Tea

Bark

n. the outer covering of a tree 树皮 a short loud sound made by a voice or a gun 枪声, 短促响亮的人声 the short loud sound made by dogs 吠声 v. A dog makes a loud sound 狗吠 to give orders, ask questions, etc. in a loud, unfriendly way. 厉声质问,厉声发问 Sb’s bark is worse than their bite. 嘴硬心软 Be barking up the wrong tree. 把方法搞错;走错路线;

Devotion

Great love, care and support for sb/sth 挚爱,关照, 关爱 His devotion to his wife and family is touching The action of spending a lot of time or energy on sth 奉献;忠诚;专心;热心 Prayers and other religious practices 宗教敬拜

高级英语 three cups of tea

Part1(paras. 1-8): Mortenson feels disappointed when he comes back to Korphe, only to find that Haji Ali hasn’t started the construction accomplished.

Three Cups of Tea

Advanced English Book 1

Structure

Part 6 (paras. 57-72) The authors give a description of Mortenson’s personal witness of how Haji Ali wisely, courageously and selflessly resolves a crisis that may have resulted in the abortion of the school construction.

The third time you share a cup of tea, you become family, and for our family ,we are prepared to do anything, even die.

Three Cups of Tea

Advanced English Book 1

Three Cups of Tea

Advanced English Book 1

Korphe: a small village in northeastern Pakistan, situated at the foot of the Karakoram mountain range.

Three Cups of Tea

高级英语(第三版)第一册第八课 Three cups of tea

undertakings • 2010 Freedom Award - Freedom Festival for extraordinary devotion to the cause of liberty at

home and abroad • 2010 American Peace Award - representing the spirit of world peace through thoughts and

Books

•co-author of Three Cups of Tea: One Man’s Mission to Promote Peace…One School at a Time • author of Stones into Schools: Promoting Peace with Books, Not Bombs, in Afghanistan and Pakistan.

CA) • 2010 Distinguished Service To Education Award: National Elementary School Principals

Association • 2010 Creativity Foundation & Smithsonian Institution: Benjamin Franklin Laureate Award

高级英语 three cups of tea培训讲学

Advanced English Book 1

Background

Instead of arriving in Askole, where his porters a66waited, he came across Korphe, a small village built on a shelf jutting out from a canyon. He was greeted and taken in by the chief elder, Haji Ali of Korphe. To repay the remote community for their hospitality, Mortenson gave away his climbing supplies as gifts and helped to cure ill villagers. Meanwhile, he promised to build a school for the village.

Advanced English Book 1

Background information Structure and style Text analysis Writing Devices

Three Cups of Tea

Advanced English Book 1

Background information

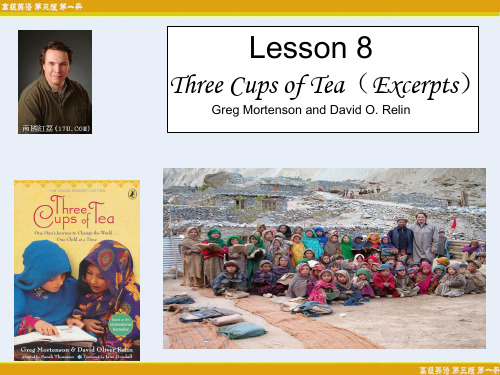

LesTea (Excerpts)

Greg Mortenson and David O. Relin

Chapter 12 Haji Ali’s Lesson

Advanced English Book 1

Warm-up

A Short Video

高级英语三杯茶节选之前的故事

高级英语三杯茶节选之前的故事英文回答:In the years leading up to the events depicted in Three Cups of Tea, Greg Mortenson embarked on a series of remarkable journeys that shaped his worldview and laid the foundation for his future endeavors.Growing up in Minnesota, Mortenson was a restless and adventurous young man. He was fascinated by the mountains and dreamed of climbing some of the world's most challenging peaks. After graduating from high school, he enlisted in the U.S. Army and served as a medic during the Vietnam War.Mortenson's experiences in Vietnam were transformative. He witnessed firsthand the horrors of war and theresilience of the human spirit. He also developed a deep compassion for the people of Southeast Asia.After leaving the military, Mortenson returned to the United States and enrolled in nursing school. He worked as a nurse for several years, but he never forgot his dream of climbing mountains. In 1993, he decided to embark on a solo trek to K2, the world's second-highest mountain.Mortenson's journey to K2 was arduous and dangerous. He faced extreme cold, altitude sickness, and the threat of avalanches. But he persevered, and after 60 days of climbing, he reached the summit.The experience of climbing K2 had a profound impact on Mortenson. He was humbled by the beauty and power of nature and realized the importance of living a life of purpose.Inspired by his climb, Mortenson founded the Central Asia Institute (CAI) in 1996. The CAI's mission is to build schools and promote education in remote mountain communities in Pakistan and Afghanistan.Mortenson's work in Central Asia has been widely recognized and praised. He has received numerous awards,including the National Geographic Society's Hubbard Medal and the Templeton Prize.In Three Cups of Tea, Mortenson tells the story of his journey from a young mountaineer to a humanitarian dedicated to improving the lives of others. His story is a testament to the power of one person to make a difference in the world.中文回答:在《三杯茶》所描述的事件发生之前的几年里,格雷格·莫滕森踏上了一系列非凡的旅程,这些旅程塑造了他的世界观并为他未来的努力奠定了基础。

three cups of tea

The Braldu Bridge they build to carry the building materials.

Korphe School

• Since 1996, he have built up more than 90 schools. It has provided education for more than 34,000 children, including 24,000 girls.

Three Cups of Tea

• In the first cup of tea, you are a stranger;

• In the second cup again, you are our friend; • In the third, you are my family, I will use my life to prote you share tea with a Balti, you are a stranger. The second time you take tea, you are an honored guest. The third time you share a cup of tea, you become family, and for our family, we are prepared to do anything, even die.” ----Haji Ali

• In an early effort to raise money he wrote letters to 580 celebrities, businessmen, and other prominent Americans. His only reply was a $100 check from NBC’s Tom Brokaw. Selling everything he owned, he still only raised $2,400. But his efforts changed when a group of elementary school children donated $623.40 in pennies, who inspired adults to begin to take action.

Unit 8 Three Cups of Tea

Unit 8 Three Cups of TeaIntroduction to the lesson1. About the authors:Greg Mortenson 葛瑞格·摩顿森凭《三杯茶》与村上春树分获2007年第11届桐山环太平洋图书奖。

他1958年出生在明尼苏达,3个月时随父母到坦桑尼亚,十几岁又回到美国。

他原是登山家,1993年,他因救援同伴,攀登乔格里峰失败,后被巴尔蒂人救起,从此和当地人结下情缘。

为兑现给巴基斯坦穷困的村庄建学校的承诺,他辛苦奔走,历时12年,在巴基斯坦和阿富汗地区建了60余所学校。

他目前是中亚协会负责人。

David Oliver Relin 大卫·奥利佛·瑞林,是个游历世界的专栏作家,其作品曾获奖无数。

'Here we drink three cups of tea to do business; the first you are a stranger, the second you become a friend, and the third, you join our family, and for our family we are prepared to do anything - even die' - Haji Ali, Korphe Village Chief, Karakoram mountains, Pakistan. In 1993, after a terrifying and disastrous attempt to climb K2, a mountaineer called Greg Mortenson drifted, cold and dehydrated, into an impoverished Pakistan village in the Karakoram Mountains. Moved by the inhabitants' kindness, he promised to return and build a school. "Three Cups of T ea" is the story of that promise and its extraordinary outcome. Over the next decade Mortenson built not just one but fifty-five schools - especially for girls - in remote villages across the forbidding and breathtaking landscape of Pakistan and Afghanistan, just as the Taliban rose to power. His story is at once a riveting adventure and a testament to the power of the humanitarian spirit.[内容简介Anyone who despairs of the individual's power to change lives has to read the story of Greg Mortenson, a homeless mountaineer who, following a 1993 climb of Pakistan's treacherous K2, was inspired by a chance encounter with impoverished mountain villagers and promised to build them a school. Over the next decade he built fifty-five schools—especially for girls—that offer a balanced education in one of the most isolated and dangerous regions on earth. As it chronicles Mortenson's quest, which has broughthim into conflict with both enraged Islamists and uncomprehending Americans, Three Cups of Tea combines adventure with a celebration of the humanitarian spirit.《三杯茶》是一本堪供借镜反躬自省的好书,我们能为我们的孩子做什么?我们能送给我们的孩子最宝贵的礼物吗?我相信读了《三杯茶》,会让我们深思谦卑反省,“顽廉懦立”。

Three Cups of Tea

Three Cups of TeaContentsIntroduction IN MR. MORTENSON’S ORBITChapter 1 FailureChapter 2 The Wrong Side of the RiverChapter 3 “Progress and Perfection”Chapter 4 Self-StorageChapter 5 580 Letters, Once CheckChapter 6 Rawalpindi’s Rooftops at DuskChapter7 Hard Way HomeChapter 8 Beaten by the BralduChapter 9 The People Have SpokenChapter 10 Building BridgeChapter11 Six DaysChapter 12 Haji Alis’s LessonChapter 13 “A Smile Should Be More Than a Memory”Chapter14 EquilibriumChapter 15 Mortenson in MotionChapter16 Red Velvet BoxChapter17 Cherry Trees in the SandChapter18 Shrouded FigureChpater19 A Village Called New YorkChapter 20 Tea with the TalibanChapter21 Rumsfeld’s ShoesChapter22 “The Enemy is Ignorance”Chapter23 Stones into SchoolsAfterwordAcknowledgmentsIndexIntroduction 序言In Mr. Mortenso n’s Orbit 莫泰森人生轨迹THE LITTLE RED light had been flashing for five minutes before Bhangoo paid it any attention. “The fuel gages on these old aircraft are notoriously unreliable,” Brigadier General Bhangoo, one of Pakistan’s most experienced high-altitude helicopter pilots, said, tapping it. I wasn’t sure if that was meant to make me feel better.I rode next to Bhangoo, looking down past me feet through the Vietnam-era Alouette’s bubble windshield. Two thousand feet below us a river twisted, hemmed in by rocky crags jutting out from both sides of the Hunza Valley. At eye level, we soared past hanging green glaciers, splintering under a tropical sun. Bhangoo flew on unperturbed, flicking the ash of his cigarette out a vent, next to a sticker that said “No smoking”.From the rear of the aircraft Greg Mortenson reached his long arm out to tap Bhangoo on the shoulder of his flight suit. “General, sir,” Mortenson shouted, “I think we’re heading the wrong way.”Brigadier Bhangoo had been President Musharraf’s personal pilot before retiring from the military to join a civil aviation company. He was in his late sixties, with salt-and-pepper hair and a mustache as clipped and cultivated as the vowels he’d inherited from the private British colonial school he’d attended as a boy with Musharraf and many of Pakistan’s other future leaders.The general tossed his cigarette through the vent and blew out his breath. Then he bent to compare the store-bought GPS unit he balanced on his knee with a military-grade map Mortenson folded to highlight what he thought was our position.“I’ve been flying in northern Pakistan for forty years,”he said, waggling his head, the subcontinent’s most distinctive gesture. “How is it you know the terrain better than me?”Bhangoo banked the Alouette steeply to port, flying back the way we’d come.The red light that had worried me before began to flash faster. The bobbing needle on the gauge showed that we had less than one hundred liters of fuel. This part of northern Pakistan was so remote and inhospitable that we’d had to have friends preposition barrels of aviation fuel at strategic sites by jeep. If we couldn’t make it to our drop zone we were in a tight spot, literally, since the craggy canyon we flew through had no level areas suitable for setting the Alouette down.Bhanggo climbed high, so he’d have the option of auto-rotating toward a more distant landing zone if we ran out of fuel, and jammed his stick forward, speeding up to ninety knots. Just as the needle hit E and the red warning light began to beep, Bhangoo settled the skids at the center of a large H, for helipad, written out in white rocks, next to our barrels of jet fuel.“That was a lovely sortie,”Bhangoo said, lighting another cigarette. “But it might not have been without Mr. Mortenson.”Later, after refueling by inserting a handpump into a rusting barrel of aviation fuel, we flew up the Braldu Valley to the village of Korphe, the last human habitation before the Baltoro Glacier begins its march up to K2 and the world’s greatest concentration of twenty-thousand-foot-plus peaks. After a failed 1993 attempt to climb k2, Mortenson arrived in Korphe, emaciated and exhausted. In this impoverished community of mud and stone huts, both Mortenson’s life and the lives of northern Pakistan’s children changed course. One evening, he went to bed by a yak dung fire a mountaineer who’d lost his way, and one morning, by the time he’d shared a pot of butter tea with his hosts and laced up his boots, he’d become a humanitarian who’d found ameaning full path to follow for the rest of his life.Arriving in Korphe with Dr. Greg, Bhangoo and I were welcomed with open arms, the head of a freshly killed ibex, and endless cups of tea. And as we listened to the Shia children of Korphe, one of the world’s most impoverished communities, talk about how their hopes and dreams for the future had grown exponentially since a big American arrived a decade ago to build them the first school their village had ever known, the general and I were done for.“You know,” Bhangoo said, as we were enveloped in a scrum of 120 students tugging us by the hands on a tour of their school, “flying with President Musharraf, I’ve become acquainted with many world leaders, many outstanding gentlemen and ladies. But I think Greg Mortenson is the most remarkable person I’ve ever met.”Everyone who has had the privilege of watching Greg Mortenson operate in Pakistan is amazed by how encyclopedically well he has come to know one of the world’s most remote regions. And many of them find themselves, almost against their will, pulled into his orbit. During the last decade, since a series of failures and accidents transformed him from a mountaineer to a humanitarian, Mortenson has attracted what has to be one of the most underqualified and overachieving staffs of any charitable organization on earth.Illiterate high-attitude porters in Pakistan’s Karakoram have put down their packs to make paltry wages with him so their children can have the education they were forced to do without. A taxi driver who chanced to pick Mortenson up at the Islamabad airport sold his cab and became his fiercely dedicated ‘fixer’. Former Taliban fighters renounce violence and the oppression of women after meeting Mortenson and went to work with him peacefully building schools for girls. He has drawn volunteers and admirers from every stratum of Pakistan’s society and from all the warring sects of Islam.Supposedly objective journalists are at risk of being drawn into his orbit, too. On three occasions, I accompanied Mortenson to northern Pakistan, flying to the most remote valleys of the Karakoram, Himalaya and the Hindu Kush on helicopters that should have been hanging from the rafters of museums. The more time I spent watching Mortenson work, the more convinced I became that I was in the presence of someone extraordinary.The accounts I’d heard about Mortenson’s adventures building schools for girls in the remote mountain regions of Pakistan sounded too dramatic to believe before I left home. The story I found, with ibex hunters in the high valleys of Karakoram, in nomad settlements at the wild edge of Afghanistan, around conference tables with Pakistan’s military elite, and over endless cups of paiyu cha in tearooms so smoky I had to squint to see my notebook, was even more remarkable than I’d imagined.As a journalist who has practiced this odd profession of probing into people’s lives for two decades, I’ve met more than my share of public figures who didn’t measure up to their own press. But at Korphe and every other Pakistani village where I was welcomed like long-lost family, because another American had taken the time to forge ties there, I saw the story of the last ten years of Greg Mortenson existence branch and fork with a richness and complexity far beyond what most of us achieve over the course of a full-length life.This is a fancy way of saying that this is a story I couldn’t simply observe. Anyone who travels to the CAI’s fifty-three schools with Mortenson is put to work, and in the process, becomes an advocate. And after staying up at all-night jirgas with village elders and weighing in on proposals for new projects, or sowing a classroom full of excited eight-year-old girls how to use the firstpencil-sharpener anyone has ever cared to give them, or teaching an impromptu class on English slang to a roomful of gravely respectful students, it is impossible to remain simply a reporter.As Graham Greene’s melancholy correspondent Thomas Fowler learned by the end of The Quiet American, sometimes, to be human, you have to take sides.I choose to side with Greg Mortenson. Not because he doesn’t have his flaws. His fluid sense of time made pinning down the exact sequence of many events in this book almost impossible, as did interviewing the Balti people with whom he works, who have no tenses in their language and as little attachment to linear time as the man they call Dr. Greg.During the two years we worked together on this book, Mortenson was often so maddeningly late for appointments that I considered abandoning the project. Many people, particularly in America, have turned on Mortenson after similar experiences, calling him “unreliable”, or worse. But I have come to realize, as his wife Tara Bishop often says, “Greg is not one of us.” He operates on Mortenson Time, a product, perhaps, of growing up in Africa and working much of each year in Pakistan. And his method of operation, hiring people with limited experience based on gut feelings, forging working alliances with necessarily unsavory characters, and, above all, winging it, while unsettling and unconventional, has moved mountains.For a man who has achieved so much, Mortenson has a remarkable lack of ego. After I agreed to write this book, he handed me a page of notepaper with dozens of names and numbers printed densely down the margin in tiny script. It was a list of his enemies. “Talk to them all,” he said, “Let them have their say. We’ve got the results. That’s all I care about.”I listened to hundreds of Mortenson’s allies and enemies. And in the interest of security and /or privacy I‘ve changed a very few names and locations.Working on this book was a true collaboration. I wrote the story. But Greg Mortenson lived it. And together, as we sorted through thousands of slides, reviewed a decade’s worth of documents and videos, recorded hundreds of hours of interviews, and traveled to visit with the people who are central to this unlikeliest of narratives, we brought this book to life.And as I found in Pakistan, Mortenson’s Central Asia Institute does, irrefutably, have the results. In a part of the world where Americans are, at best misunderstood, and more often feared and loathed, this soft-spoken, six-foot-four former mountaineer from Montana has put together a string of improbable successes. Though he would never say so himself, he has singlehandedly changed the lives of tens of thousands of children, and independently won more hearts and minds than all the official American propaganda flooding the region.So this is a confession: Rather than simply reporting on his progress, I want to see Greg Mortenson succeed. Wish him success because he is fighting the war on terror the way I think it should be conducted. Slamming over the so-called Karakoram “Highway” in his old Land Cruiser, taking terror every time, he offers a student a chance to receive a balanced education, rather than attend an extremist madrassa.If we Americans are to learn from our mistakes, from the flailing, ineffective way we, as a nation, conducted the war on terror after the attacks of 9/11, and from the way we have failed to make our case to the great moderate mass of peace-loving people at the heart of the Muslim world, we need to listen to Greg Mortenson. I did, and it has been one of the most rewarding experiences of y life.--David Oliver RelinPortland, OregonChapter 1 FAILUREWhen it is dark enough, you can see the stars. – Persian proverbIn Pakistan’s karakoram, bristling across an area barely one hundred miles wide, more than sixty of the world’s tallest mountains lord their severe alpine beauty over a witnessless high-altitude wilderness. (在昆仑山区,方园百里,耸立着60多座高山,漫无边际,荒无人烟). Other than snow leopard and ibex, so few living creatures have passed through this barren icescape that the presence of the world’s second-highest mountain, K2, was little more than a rumor to the outside world until the turn of the twentieth century.Flowing down from K2 toward the populated upper reaches of the Indus Valley, between the four fluted granite spires of the Gasherbrums and the lethal-looking daggers of the Great Trango Towers, the sixty-two-kilometer-long Baltoro Glacier barely disturbs this still cathedral of rock and ice. And even the motion of this frozen river, which drifts at a rate of four inches a day, is almost undetectable.On the afternoon of September 2, 1993, Greg Mortenson felt as if he were scarcely traveling any faster. Dressed in a much-patched set of mud-colored shalwar kamiz, like his Pakistani porters, he had the sensation that his heavy black leather mountaineering boots were independently steering him down the Baltoro at their own glacial speed, through an armada of icebergs arrayed like the sails of a thousand ice-bound ships.At any moment, Mortenson expected to find Scott Darsney, a fellow member of his expedition, with whom he was hiking back toward civilization, sitting on a boulder, teasing him for walking so slowly. But the upper Baltoro is more maze than trail. Mortenson hadn’t yet realized that he was lost and alone. He’d strayed from the mail body of the glacier to a side spur that led not westward, toward Askole, the village fifty miles farther on, where he hoped to find a jeep driver willing to transport him out of these mountains, but south, into an impenetrable maze of shattered icefall, and beyond that, the high altitude killing zone where Pakistani and Indian soldiers lobbed artillery shells at one another through in thin air.Ordinarily Mortenson would have paid more attention. He would have focused onlife-and-death information like the fact that Mouzafer, the porter who had appeared like a blessing and volunteered to haul his heavy bag of climbing gear, was also carrying his tent and nearly all of his food and kept him in sight. And he would have paid more minds to the overawing physicality of his surroundings.In 1909, the duke of Abruzzi, one of the greatest climbers of his day, and perhaps his era’s most discerning connoisseur of precipitous landscapes, led an Italian expedition up the Baltoro for an unsuccessful attempt at K2. He was stunned by the stark beauty of the encircling peaks. “Nothing could compare to this in terms of alpine beauty,” he recorded in his journal. “It was a world of glaciers and crags, an incredible view which could satisfy an artist just as well as a mountaineer.”But as the sun sank behind the great granite serrations of Muztagh Tower to the west, and shadows raked up the valley’s eastern walls, toward the bladed monoliths of Gasherbrum, Mortenson hardly noticed. He was looking inward that afternoon, stunned and absorbed by something unfamiliar in his life to that point—failure.Reaching into the pocket of his sbalwar, he fingered the necklace of amber beads that his little sister Christa had often worn. As a three-years-old in Tanzania, where Mortenson’sMinnesota-born parents had been Lutheran missionaries and teachers, Christa had contracted acute meningitis and never fully recovered. Greg, twelve years her senior, had appointed himself her protector. Though Christa struggled to perform simple tasks—putting on her clothes each morning took upward of an hour—and suffered severe epileptic seizures, Greg pressured his mother, Jerene, to allow her some measure of independence. He helped Christa find work at manual labor, taught her the route of the Twin Cities’ public buses, so she could move about freely, and to their mother’s mortification, discussed the particulars of birth control when he learned she was dating.Every year, whether he was serving as a U.S. Army medic and platoon leader in Germany, working on a nursing degree in South Dakota, studying the neurophysiology of epilepsy at graduate school in Indiana in hopes of discovering a cure for Christa, or living a climbing bum’s life out of his car in Berkeley, California, Mortenson insisted that his little sister visit him for a month. Together, they sought out the spectacles that brought Christa so much pleasure. They took in the Indy 500, the Kentucky Derby, road-tripped down to Disneyland, and he guided her through the architecture of his personal cathedral at that time, the storied granite walls of Yosemite.For her twenty-third birthday, Christa and their mother planned to make a pilgrimage from Minnesota to the cornfield in Deyersville, lowa, where the movie that Christa was drawn to watch again and again, Field of Dreams, had been filmed. But on her birthday in the small hours before they were to set out, Christa died of a massive seizure.After Christa’s death, Mortenson retrieved the necklace from among his sister’s few things. It still smelled of a campfire they had made during her last visit to stay with him in California. He brought it to Pakistan with him, bound in a Tibetan prayer flag, along with a plan to honor the memory of his little sister. Mortenson was a climber and he had decided on the most meaningful tribute he had within him. He would scale K2, the summit most climbers consider the toughest to reach on Earth, and leave Christa’s necklace there at 28,267 feet.He had been raised in a family that had relished difficult tasks, like building a school and a hospital in Tanzania, on the slopes of Mount Kilimanjaro. But despite the smooth surfaces of his parents’ unquestioned faith, Mortenson hadn’t yet made up his mind about the nature of divinity. He would leave an offering to whatever deity inhabited the upper atmosphere.Three months earlier, Mortenson had positively skipped up this glacier in a pair of Teva sandals with no socks, his ninety-pound pack beside the point of the adventure that beckoned him up the Baltoro. He had set off on the seventy-mile trek from Askole with a team of then English, Irish, French, and American mountaineers, part of a poorly financed but pathologically bold attempt to climb the world’s second-highest peak.Compared to Everest, a thousand miles southeast along the spine of the Himalaya, K2, they all knew, was a killer. To climbers, who call it “The Savage Peak,” it remains the ultimate test, a pyramid of razored granite so steep that snow can’t cling to its knife-edged ridges. And Mortenson, then a bullishly fit thirty-five-year-old, who had summited Kilimanjaro at age eleven, who’d been schooled on the sheer granite walls of Yosemite, then graduated to half a dozen successful Himalaya ascents, had no doubt when he arrived in May the he would soon stand on what he considered “the biggest and baddest summit on Earth.”He’d come shatteringly close, within six hundred meters of the summit. But K2 had recededinto the mists behind him and the necklace was still in his pocket. How could this have happened? He wiped his eyes with his sleeve, disoriented by unfamiliar tears, and attributed them to thealtitude. He certainly wasn’t himself. After seventy-eight days of primal struggle at altitude on K2, he felt like a faint. Shriveled caricature of himself. He simply didn’t know if he had the reserves left to walk fifty more miles over dangerous terrain to Askole.The sharp, shotgun crack of a rockfall brought him back to his surroundings. He watched a boulder the size of a three-story house accelerate, bouncing and spinning down a slope of scree, then pulverize an iceberg on the trail ahead of him.Mortenson tried to shake himself into a state of alertness. He looked out of himself, saw how high the shadows had climbed up the eastern peaks, and tried to remember how long it had been since he’d seen a sign of other humans. It had been hours since Scott Darsney had disappeared down the trail ahead of him. An hour earlier, or maybe more, he’d heard the bells of an army mule caravan carrying ammunition toward the Siachen Glacier, the twenty-thousand-foot-high battlefield a dozen miles southeast where the Pakistani military was frozen into its perpetual deadly standoff with the Indian army.He scoured the trail for signs. Anywhere on the trail back to Askole, there would be debris left behind by the military. But there was no mule dropping. No cigarette butts. No food tins. No blades of the hay the mule drivers carried to feed their animals. He realized it didn’t look much like a trail at all, simply a cleft in an unstable maze of boulders and ice, and he wondered how he had wandered to this spot. He tried to summon the clarity to concentrate. But the effects of prolonged exposure to high altitude had sapped Mortenson of the ability to act and think decisively.He spent an hour scrambling up a slope of scree, hoping for a vantage point above the boulders and icebergs, a place where he might snare the landmark he was looking for, the great rocky promontory of Urdukas, which thrust out onto the Baltoro like a massive fist, and haul himself back toward the trail. But at the top he was rewarded with little more than a greater degree of exhaustion. He’d strayed eight miles up a deserted valley from the trail, and in the failing light, even the contours of peaks that he knew well looked unfamiliar from his new perspective.Feeling a finger of panic probing beneath his altitude-induced stupor, Mortenson sat to take stock. In his small sun-faded purple daypack he had a lightweight wool Pakistani army blanket, an empty water bottle, and a single protein bar. His high-altitude down sleeping bag, all his matches were in the pack the porter carried.He’d have to spend the night and search for the trail in daylight. Though it had already dropped well below zero, he wouldn’t die of exposure, he thought. Besides, he was coherent enough to realize that stumbling, at night, over a shifting glacier, where crevasses yawned hundreds of feet down through wastes of blue ice into subterranean pools, was far more dangerous. Picking his way down the mound of scree, Mortenson looked for a spot far enough from the mountain walls that he wouldn’t be crushed by rockfall as he slept and solid enough that he wouldn’t split and plunge him into the glacier’s depths.He found a flat slab of rock that seemed stable enough, scooped icy snow into his water bottle with ungloved hands and wrapped himself in his blanket, willing himself not to focus on how alone and exposed he was. His forearm was lashed with rope burns from the rescue, and he knew he should tear off the clotted gauze bandages and drain pus from the wounds that refused to heal at this altitude, but he couldn’t quiet locate the motivation. As he lay shivering on uneven rock, Mortenson watched as the last light of the sun smoldered blood red on the daggeredsummits to the east, then flared out, leaving their afterimages burning in blue-black.Nearly a century earlier, Filippo De Fillippi, doctor for and chronicler of the duke of Abruzzi’s expedition to the Karakoram, recorded the desolation he felt among these mountains. Despite the fact that he was in the company of two dozen Europeans and 260 local porters, that they carried folding chairs and silver tea services and European newspapers delivered to them regularly by a fleet of runners, he felt rushed into insignificance by the character of this landscape.”Profound silence would brood over the valley,” he wrote, “even weighing down our spirits with indefinable heaviness. There can be no other place in the world man feels himself so along, so isolated, so completely ignored by Nature, so incapable of entering into communion with her.”Perhaps it was his experience with solitude, being the lone American child among hundreds of Africans, or the nights he spent bivouacked three thousand feet up Yosemite’s Half Dome in the middle of a multiday climb, but Mortenson felt at ease. If you ask him why, he’ll creditaltitude-induced dementia. But anyone who has spent time in Mortenson’s presence, who’s watched him wear down a congressman or a reluctant philanthropist or an Afghan warlord with his doggedness, until he pried loose overdue relief funds, or a donation, or the permission he was seeking to pass into tribal territories, would recognize this night as one more example of Mortenson’s steely-mindedness.The wind picked up and the night became bitterly crystalline. He tried to discern the peaks he felt hovering malevolently around him, but he couldn’t make them out among the general blackness. After an hour under his blanket he was able to thaw his frozen protein bar against his body and melt enough silty icewater to wash it down which set him shivering violently. Sleep, in this cold, seemed out of the question. So Mortenson lay beneath the stars salting the sky and decided to examine the nature of his failure.The leaders of his expedition, Dan Mazur and Jonathan Pratt, along with French climber Etienne Fine, were thoroughbreds. They were speedy and graceful, bequeathed the genetic wherewithal to sprint up technical pitches at high altitude. Mortenson was slow and bearishly strong. At six-foot-four and 210 pounds, Mortenson had attended Minnesota’s Concordia College on a football scholarship.Though no one directed that is should be so, the slow, cumbersome work of mountain climbing fell naturally to him and to Darsney. Eight separate times Mortenson served as pack mule, hauling food, fuel, and oxygen bottles to several stashes on the way to the Japanese Couloir, a tenuous aerie the expedition carved out within six hundred meters of K2’s summit, stocking the expedition’s high camps so the lead climbers might have the supplies in place when they decided to dash to the top.All of the other expeditions on the mountain that season had chosen to challenge the peak in the traditional way, working up the path pioneered nearly a century earlier, K2’s Southeastern Abruzzi Ridge. Only they had chosen the West Ridge, a circuitous, brutally difficult route, littered with land mine after land mine of steep, technical pitches, which had been successfully scaled only once, twelve years earlier, by Japanese climber Eiho Otani and his Pakistani partner Nazir Sabir.Mortenson relished the challenge and took pride in the rigorous route they’d chosen. And each time he reached one of the perches they’d clawed out high on the West Ridge, and unloaded fuel canisters and coils of rope, he noticed he was feeling stronger. He might be slow, but reaching thesummit himself began to seem inevitable.Then one evening after more than seventy days on the mountain, Mortenson and Darsney were back at base camp, about to drop into well-earned sleep after ninety-six hours of climbing during another resupply mission. But while taking a last look at the peak through a telescope just after dark, Mortenson and Darsney noticed a flickering light high up on K2’s West Ridge. They realized it must be members of their expedition, signaling with their headlamps, and they guessed that their French teammate was in trouble. “Etienne was an Alpiniste,” Mortenson explains, underlining with an exaggerated French pronunciation the respect and arrogance the term can convey among climbers. “He’d travel fast and light with the absolute minimum amount of gear. And we had to bail him out before when he went up too fast without acclimatizing.”Mortenson and Darsney, doubting whether they were strong enough to climb to Fine so soon after an exhausting descent, called for volunteers from the five other expeditions at base camp. None came forward. For two hours they lay in their tents resting and rehydrating, then they packed their gear and went back out.Descending from their seventy-six-hundred-meter Camp IV, Pratt and Mazur found themselves in the fight of their lives. “Etienne had climbed up to join us for a summit bid,”, Mazur says.”But when he got to us, he collapsed. As he tried to catch his breath, he told us he heard a rattling in his lungs.”。

three cups of tea课文原文高级英语

three cups of tea课文原文高级英语Three Cups of Tea is a non-fiction book written by Greg Mortenson and David Oliver Relin. The book tells the inspiring story of Greg Mortenson, a mountain climber turned humanitarian, who dedicated his life to building schools for children in remote areas of Pakistan and Afghanistan.The book begins with Mortenson's failed attempt to climb K2, the second-highest mountain in the world. Lost and exhausted, Mortenson stumbles into a small village called Korphe in Pakistan, where the local villagers take him in and nurse him back to health. Grateful for their kindness, Mortenson promises to come back and build a school for the children of Korphe.Over the next few years, Mortenson faces numerous challenges and setbacks in his quest to fulfill his promise. He struggles to raise funds, faces resistance from local authorities, and even survives a kidnapping by the Taliban. Despite these obstacles, Mortenson perseveres, driven by his belief in the power of education to change lives.As Mortenson builds more schools, he also builds relationships with the local communities, earning their trust andrespect. He becomes a champion for girls' education, advocating for equal opportunities for all children, regardless of their gender or background.Through his work, Mortenson not only provides children with access to education but also fosters a sense of hope and empowerment among the communities he serves. He demonstrates the importance of compassion, perseverance, and cross-cultural understanding in creating positive change in the world.Three Cups of Tea is a powerful testament to the impact of one person's dedication and commitment to making a difference. It serves as a reminder that small acts of kindness and generosity can have far-reaching consequences, inspiring others to take action and create a better future for all.。

three-cups-of-teaPPT课件

• In an early effort to raise money he wrote letters to 580 celebrities, businessmen, and other prominent Americans. His only reply was a $100 check from NBC’s Tom Brokaw. Selling everything he owned, he still only raised $2,400. But his efforts changed when a group of elementary school children donated $623.40 in pennies, who inspired adults to begin to take action.

Three Cups of Tea

1

• In the first cup of tea, 敬上一杯茶,你是 you are a stranger; 一个陌生人;

• In the second cup again, you are our friend;

再奉第二杯,你是 我们的朋友;

• In the third, you are my family, I will use my life to protest you.

• A mountaineer • Co-founder of nonprofit

Central Asia Institute(中亚 协会)

3

In the pool area of Pakistan, education is hard to come by.

4

Haji Ali, the village head of Korphe

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

School of Government • 2009 U.S. News & World Report: America's Top 20 Best Leaders 2009 • 2009 Italy: Premio Gambrinus “Giuseppe Mazzotti”

Greg Mortenson’s Awards (2)

construction.

Greg Mortenson

• Born on Dec. 27, 1957 • an American humanitarian,

professional speaker, writer, former mountaineer and a military veteran. • co-founder and Executive Director of the non-profit Central Asia Institute ( whose mission is to promote and support community-based education, esp. for girls, in remote regions of northern Pakistan and Afghanistan) • founder of the educational charity Pennies for Peace.

Books

•co-author of Three Cups of Tea: One Man’s Mission to Promote Peace…One School at a Time • author of Stones into Schools: Promoting Peace with Books, Not Bombs, in Afghanistan and Pakistan.

• 2004 Al Neuharth Free Spirit of the Year Award for building schools for Pakistan girls. • 2008 Citizen Center for Diplomacy National Award for Citizen Diplomacy • 2008 Courage of Conscience Award • 2008 Graven Award - Wartburg College, IA • 2008 National Award for Citizen Diplomacy - Citizen Center for Diplomacy • 2008 Mary Lockwood Founders Medal For Education - Daughters of The American

education issues for peace • 2009 National Education Association (NEA) Human & Civil Rights Award • 2009 City College San Francisco Amicus Collegii Award - Promoting peace through education • 2009 Jefferson Award For Community Service: Carnegie Endowment & Harvard Kennedy

• 2010 Loyola Marymount University (CA) - Doshi Bridgebuilder Of Peace Award • 2010 The Common Wealth Awards: For Public Service • 2010 The Salem Award for Human Rights • 2010 The Christopher Award: "To affirm the highest values of the human spirit" • 2010 The 10th annual Lantern Award “Excellence in Education Innovation” (MOSTE – LA,

高级英语(第三版)第一册第八课 Three cups of tea

Teaching Objectives of Lesson 8

• Familiarize students with social, economic, religious background of Pakistan;

• Acquaint students with knowledge of local customs; • Enable students to learn idiomatic expressions in the text; • Familiarize students with vocabulary concerning

•More than tene and another impossibilities , and then make them possible.

Greg Mortenson with children

Greg Mortenson’s Awards (1)