美国版权法(第一部分)

美国著作权转让法律规定(3篇)

第1篇一、引言著作权转让是指著作权人将其著作权中的全部或部分权利转移给他人的法律行为。

在美国,著作权转让的法律规定较为严格,涉及多个法律文件和判例。

本文将从美国著作权转让的法律基础、转让的条件、转让的效力、转让的限制等方面对美国著作权转让法律规定进行详细阐述。

二、美国著作权转让的法律基础1. 著作权法美国著作权转让的法律基础主要是《美国著作权法》(United States Copyright Act),该法于1976年颁布,于1998年、2001年、2005年、2008年、2012年、2018年进行了多次修订。

著作权法规定了著作权人的权利、著作权的内容、著作权转让的条件、转让的效力等内容。

2. 合同法著作权转让涉及合同法,合同法规定了合同的成立、效力、履行、变更、解除等方面的法律规则。

在著作权转让中,著作权人和受让人之间需要签订转让合同,合同法对合同的成立和效力有明确规定。

三、美国著作权转让的条件1. 明确的转让对象著作权转让需要明确转让的对象,即著作权中的哪些权利被转让。

在美国著作权法中,著作权包括复制权、发行权、展览权、表演权、改编权、翻译权、制作录音制品权等。

著作权人可以将全部或部分权利转让给他人。

2. 明确的转让范围著作权转让需要明确转让的范围,即著作权转让的地域范围和期限。

在美国著作权法中,著作权人可以将著作权转让给特定地域的受让人,也可以将著作权转让给特定期限的受让人。

3. 明确的转让方式著作权转让需要明确转让的方式,即著作权转让是通过书面合同还是口头协议等方式进行。

在美国著作权法中,著作权转让应当采用书面形式,以保证转让的效力。

4. 转让方的权利和义务著作权转让需要明确转让方的权利和义务。

在美国著作权法中,转让方有义务保证其转让的权利是合法的,受让人有义务按照转让合同履行义务。

四、美国著作权转让的效力1. 合法性著作权转让的效力首先取决于其合法性。

在美国著作权法中,著作权转让应当符合法律规定的条件,否则转让无效。

92茂凝-美国的版权登记和版权保护概述

美国的版权登记和版权保护概述国家版权局版权管理司蒋茂凝〔2008年9月12日中国版权保护中心〕一、美国版权局概况美国版权局隶属于国会图书馆,是国会图书馆下面的六个部门之一,属于美国的国会系统。

它的法定编制是530人,现在实际的员工是480人。

根据1976年的版权法规定,版权局是局长一名,副局长四名,但现在只有一正两副,还空缺两名。

在06年财政年度(美国的财政年度是从本年的10月1号到次年的9月30号),美国版权局的工作经费预算是5800万。

经费一部分来自财政部的拨款——2200多万,其它部分,则需要用版权登记的收费来补充。

也就是说,自己要补充3000多万。

美国的国会图书馆与其它国家的国家图书馆的职能是不同的,美国国会图书馆设立的目的是为国会的议员服务。

它规定:只有在条件许可的情况下,在首先满足国会议员需求的前提下,才向社会公众提供服务。

美国的版权登记制度也有为充实国会图书馆馆藏作品而服务这样一个目的。

美国版权局的主要职责是负责各类作品的版权登记。

另外,根据法律规定,就版权的法规和政策,对国会、法院以及其它行政部门提供咨询,为国会修改《版权法》提供建议,并协助司法部进行版权保护,这个版权保护是指刑事保护。

美国的版权登记制度肇始于1790年( 1789年,美国联邦政府成立,1790年颁布了第一部《版权法》,颁布后两个星期,就开始了版权登记)。

当时的法律里面对版权登记就有明确的规定。

1790年的《版权法》施行至今,经历了50余次的修订,其中大的修订有4次,第4次就是1976年的修订,美国现行《版权法》也被称为1976年的版权法,自78年的1月1号开始施行。

1976年《版权法》里强化了对版权登记的许多规定。

版权登记制度是美国《版权法》首创的一项重要制度。

它起因于当时美国国内的盗版非常泛滥,侵权现象比比皆是。

为了正本清源,法律规定:作品无论是发表与否,作品的版权所有人,可以在版权的有效期内,向版权局登记自己的作品。

深度解析美国音乐版权法保护侵权与赔偿

深度解析美国音乐版权法保护侵权与赔偿音乐是人类文化的重要组成部分,它不仅能够带给人们快乐和享受,还能够表达情感和传递信息。

然而,随着数字技术的快速发展,音乐版权问题逐渐成为一个全球性的难题。

本文将深入解析美国音乐版权法,重点关注其对侵权行为的保护及相应赔偿措施。

一、美国音乐版权法的概述1.1 背景与发展美国音乐版权法的建立源于对音乐创作者和知识产权的保护需求。

早在18世纪末,美国国会就开始考虑须要立法规定音乐版权的保护,迄今已经经历了多次修订和完善。

1.2 法律框架美国音乐版权法主要来源于《美国宪法》中的版权条款,以及一系列补充性的法律、法规和国际公约。

美国音乐版权法是基于著作权法,但相对于其他领域的版权法律,其特点是更为复杂且涉及的利益方众多。

二、美国音乐版权法对侵权行为的保护2.1 著作权保护范围美国音乐版权法规定了对音乐作品享有著作权的标准,包括原创性和独创性等要求。

只有符合这些标准的音乐作品才能受到法律的保护。

2.2 禁止侵权行为美国音乐版权法禁止未经授权的复制、发行、公开表演、数字传播等侵犯音乐作品著作权的行为。

对于侵权行为,版权法提供了明确的惩罚措施,并对侵权者进行追责。

2.3 数字音乐版权保护随着数字音乐的兴起,美国音乐版权法进行了相应的修订,加强了对数字音乐版权的保护。

数字音乐提供商需要获得版权拥有者的授权,以避免侵权行为。

三、美国音乐版权法对侵权行为的赔偿措施3.1 判决侵权损失美国音乐版权法规定,侵权行为导致的损失包括实际损失和被告的非法获利。

版权拥有者可以通过诉讼要求被告赔偿其损失,并有权获得相应的法定赔偿额。

3.2 双倍或三倍赔偿如果被告的侵权行为被认定为故意或恶意,法庭有权判决赔偿金额增加一倍或两倍。

这一规定旨在惩罚故意侵权行为,强化版权保护。

3.3 律师费用补偿如果版权拥有者通过诉讼获胜,法庭可以判决被告支付版权拥有者的律师费用。

这一规定旨在减轻版权拥有者的诉讼成本,同时降低恶意侵权的风险。

美国知识产权法中的版权问题

美国知识产权法中的版权问题版权是指作者对其原创作品所享有的法律保护权益,旨在鼓励和保护创作力量的发展。

在美国,版权是基于宪法授权的,通过美国知识产权法进行保护和管理。

本文将探讨美国知识产权法中的版权问题,并介绍相关案例和适用的法律原则。

一、版权保护的对象和要求美国知识产权法对版权保护的对象作了明确规定。

根据《美国版权法》,版权保护的对象包括但不限于文字、音乐、艺术作品、戏剧、摄影作品、电影和音像制品等。

这些作品必须符合一定的要求,例如必须是原创作品,具有一定的创造性和独创性。

二、版权的取得与保护在美国,版权的取得相对简单,作者在创作作品时就已经拥有了版权。

根据“即创即权”的原则,只要作品以任何形式被表达出来,例如文字、图片、录音等,版权立即生效。

此外,作者可以选择注册版权,以加强其法律保护力度。

美国版权法规定了版权的保护期限。

根据现行法律,版权保护一般为作者终身及其逝世后再70年。

对于合作作品、匿名作品和作品对公众有贡献但作者难以辨认的情况,版权保护期还可能更长。

三、版权侵权行为与惩罚在美国,版权侵权行为严重侵害了作者的权益,因此得到了严厉打击。

常见的版权侵权行为包括盗版、翻版、复制、散布和传播未经授权的作品等。

美国知识产权法赋予权利人(通常是作者或其合法继承人)一系列权力来保护他们的作品权益。

针对版权侵权行为,美国知识产权法设立了多项法律制度,例如采取法律诉讼、申请行政执法手段、索赔损失等。

同时,美国法律对于盗版行为的处罚力度较大,违法者可能面临巨额罚款、刑事指控甚至坐牢的风险。

四、案例分析1. 索尼音乐娱乐公司对Napster的起诉案1999年,索尼音乐娱乐公司起诉Napster公司侵犯了其音乐作品的版权。

该案引起了广泛关注,并最终导致Napster服务关闭。

这个案例凸显了版权法保护作者权益的重要性,也展示了美国知识产权法在维护版权方面的实际效果。

2. Disney对亚马逊公司的版权侵权案近年来,Disney公司在美国法院起诉亚马逊公司侵犯其电影作品的版权。

美国版权法与标准版权政策研究

【美洲册究】Standards Observation 标准观察38美国版权法与标准版权政策研究背景美国是对知识产权极为关注的发达国家之一,在其《1787宪法》中就规定了有关知识产权保护 的条款。

经过两个多世纪的发展、完善,美国现 已形成了涵盖版权、专利、商标等知识产权保护的多层次司法体系。

标准作为一种知识成果,同样在美国受知识产权法律保护.知识产权也是中美贸易摩擦的焦点之一,在中美第一阶段经贸协议中,知识产权涉及了众多篇幅版权是与标准相关性较高的知识产权,与专 利不同,版权与标准本身融为一体近年来,美 国的众多标准制定机构也对中国标准的知识产权保护给予了较多关注。

可以预见,加强标准版权方面的国内外协调,是推动中国标准走出去的一个重要途径。

_、美国版权法与标准概述1.美国版权法概述1790年,美国颁布实施第一部《版权法》,是 世界上较早实行知识产权保护制度的国家。

1976 年,美国对《版权法》进行了全面修改,构成了美国现行版权管理的基本法律框架此后,美国《版 权法》又不断经历修订1989年,美国正式加入《伯 尔尼公约》,至此美国的版权法内容正式与国际接轨…现行的美国《版权法》是1990年修订的。

2.美国版权法对于标准的适用条款标准作为一种智力成果,受美国版权法保护。

《版权法》已经成为美国版权保护中最重要的法律基础,该法同样适用于美国标准的版权保护。

该法第102条“版权的客体”规定:“依据版 权法,版权保护存在于任何有形表现媒介(现已 知)中的原创作品中,这种表现媒介包括目前已知的或以后发展的,通过这种媒介,作品可以被感知、复制或以其他方式传播,不论是直接的或 借助于机器或装置:”标准作为一种存在于有形媒 介中的技术文件,属于美国版权法的管辖范围,在ASTM、ASME、IEEE等美国标准制定机构知识产权政策中均有明确规定。

①版权标志美国《版权法》第401条规定,受该法保护的 作品在美国境内外公开发行物上出版时均应附有质■: 4标准化Quality a丨vj Standardization 2021.0339标准观察Standards Observation版权标记。

美国媒体法言论自由版权与隐私保护

美国媒体法言论自由版权与隐私保护美国媒体法:言论自由、版权与隐私保护美国作为一个言论自由的国家,其媒体法在保护公民的言论自由权利、版权和隐私保护方面起着重要的作用。

媒体法是指对媒体行为和内容进行监管的法律体系,旨在维护公众利益和社会秩序。

本文将就美国的媒体法,特别是针对言论自由、版权和隐私保护的相关法规进行探讨。

一、言论自由言论自由是美国宪法第一修正案赋予公民的基本权利之一,也是美国法律体系中最重要的价值观之一。

美国以其对言论自由的坚定保护而闻名于世。

美国宪法第一修正案规定:“国会不得通过法律限制言论自由,也不得剥夺人民对新闻出版自由的权利。

”这一规定确保了公民表达自己观点的自由,保障了新闻媒体对政府的监督作用。

然而,尽管言论自由受到广泛的保护,但也有一些限制。

美国法律对于一些特定的言论活动实行严格监管,如恶意中伤、诽谤、诬告、侵犯国家安全等。

此外,关于版权和隐私的法规也对言论自由有一定的限制,但在一定程度上是为了平衡各方权益。

二、版权保护版权保护是指对作品原创性的保护,确保作者享有合法权益。

在美国,版权保护是基于宪法授权的。

宪法第一条款赋予国会权力:“为科学等文艺所作之新发明创究,按有权人所得,以为一定期间所有权利之保管。

”美国版权法对版权作品进行了详细的规定,包括作品的形式、权利的定义、权利的行使方式等。

根据美国版权法,只有原创性的作品才能享有版权保护。

版权包括了文学、音乐、戏剧、艺术和摄影等各个领域的作品。

在数字化时代,版权保护面临了新的挑战,如互联网上的盗版问题。

美国立法机构通过一系列法律,如数字千年版权法(DMCA)、索尼-百事达案等,加强了对版权的保护,维护了创作者的权益。

三、隐私保护隐私保护是美国法律体系中的重要组成部分,旨在保护个人的隐私权和安全。

它在媒体法中起到了重要的角色。

美国虽然没有明确的宪法条款规定隐私权,但最高法院对隐私权的保护进行了定量。

例如,最高法院在格里斯沃尔德诉康涅狄格州案中首次确认了个人的隐私权。

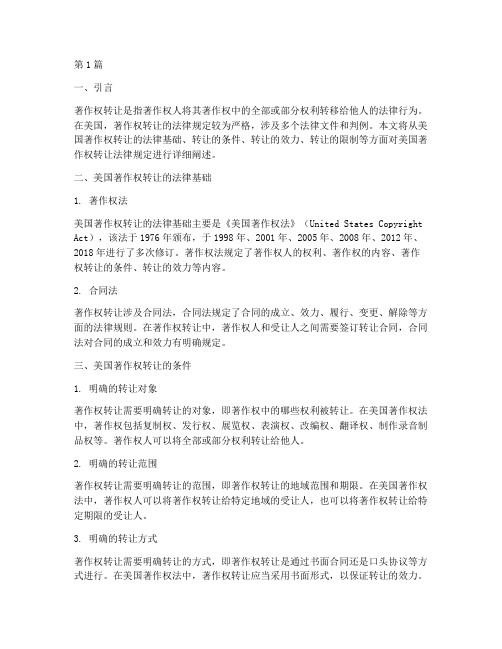

美国版权法的保护范围

美国版权法的保护范围版权是指对各种形式的创造性作品的独有权利。

在全球范围内,版权法都扮演着保护知识产权和推动创作的重要角色。

美国作为全球最大的创意产业中心之一,其版权法的保护范围备受关注。

本文将探讨美国版权法的保护范围,重点介绍受版权保护的作品类型、保护的对象以及寻求版权保护的程序。

一、受版权保护的作品类型根据美国版权法,几乎所有表现形式的创意作品都可以受到版权保护。

常见的受版权保护的作品类型包括但不限于以下几类:1. 文学作品:包括小说、诗歌、剧本和其他文学作品等。

2. 音乐作品:包括音乐作曲家的音乐创作、歌曲和乐谱等。

3. 艺术作品:包括绘画、雕塑、摄影和其他视觉艺术作品等。

4. 影视作品:包括电影、电视节目、广告和其他视听作品等。

5. 建筑作品:包括建筑物、城市规划和其他建筑设计作品等。

6. 软件和计算机代码:包括计算机程序、应用软件和网站等。

7. 衍生作品:包括基于已有作品进行改编、演绎或者二次创作的作品等。

二、版权的保护对象除了特定的作品类型外,版权法对于作品的原创性和固定性也有要求。

只有满足下列条件的作品才能享受版权保护:1. 原创性:作品必须是独创的,而不仅是单纯的复制或模仿。

2. 固定性:作品必须以某种形式予以固定,可以是书面、录音、录像、电子或数字形式等。

版权法并不要求事先登记或标记作品以获得版权保护。

作品在创作者创作的同时就已经受到版权法的保护。

然而,为了在侵权纠纷中拥有更有力的证据,作品的登记和标记仍然被鼓励和推荐。

三、寻求版权保护的程序在美国,作品的版权保护程序相对简单。

一般来说,版权保护的步骤包括以下几个方面:1. 创作作品:创作者在创作作品时,需要确保作品的原创性和固定性。

2. 登记版权:尽管版权并不需要登记,但是作品的登记可以加强对版权的保护。

创作者可以通过美国版权局的网站或邮寄方式进行登记。

登记作品后,创作者可以获得有关作品的官方证明和登记日期等证据。

3. 保留证据:创作者应该保留与作品创作和发表相关的一切记录,包括但不限于创作过程中的草稿、照片、音频和视频等。

外国关于剽窃的法律规定(3篇)

第1篇一、引言剽窃,即未经他人许可,擅自使用他人的作品、发明、商标等知识产权的行为。

随着全球知识产权意识的不断提高,各国纷纷制定相关法律法规来打击剽窃行为,保护知识产权。

本文将介绍一些主要国家的剽窃法律规定,以期为我国相关立法提供借鉴。

二、美国关于剽窃的法律规定1. 著作权法美国著作权法(Copyright Law)规定,未经著作权人许可,擅自复制、发行、表演、展示、播放、翻译、改编等使用作品的行为均构成剽窃。

著作权法第106条规定了著作权人的17项专有权利,其中包括复制权、发行权、表演权等。

2. 侵权责任美国著作权法规定,剽窃行为构成侵权,侵权人需承担停止侵害、赔偿损失等法律责任。

根据《美国侵权法重述》第55条,剽窃行为属于不正当竞争行为,侵权人需赔偿被侵权人的实际损失、合理费用和惩罚性赔偿。

3. 刑事责任在美国,剽窃行为可能涉及刑事责任。

根据《美国法典》第18卷第506条,侵犯著作权可能面临最高5年的监禁和25万美元的罚款。

三、英国关于剽窃的法律规定1. 著作权法英国著作权法(Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988)规定,未经著作权人许可,擅自复制、发行、出租、展示、表演、播放、改编等使用作品的行为均构成剽窃。

著作权法第16条规定了著作权人的17项专有权利。

2. 侵权责任英国著作权法规定,剽窃行为构成侵权,侵权人需承担停止侵害、赔偿损失等法律责任。

根据《英国侵权法》第2条,剽窃行为属于不正当竞争行为,侵权人需赔偿被侵权人的实际损失、合理费用和惩罚性赔偿。

3. 刑事责任在英国,剽窃行为可能涉及刑事责任。

根据《英国法典》第279条,侵犯著作权可能面临最高6个月的监禁和5,000英镑的罚款。

四、德国关于剽窃的法律规定1. 著作权法德国著作权法(Urheberrechtsgesetz)规定,未经著作权人许可,擅自复制、发行、出租、展示、表演、播放、改编等使用作品的行为均构成剽窃。

1976年美国版权法的变迁

展望

未来美国版权法的发展将更加注重平衡创作者权益和社会公共利益之间的关系。在保护 创作者权益的同时,也需充分考虑社会公共利益的需求,避免因过度保护而阻碍了文化 产业的创新和发展。此外,国际合作也将成为未来版权法发展的重要方向,各国将加强

合作,共同打击跨国版权侵权行为,推动全球文化产业的发展。

加强了对创作者权益的保护, 提高了创作者的创作积极性和

收入水平。

04

1976年之后版权法的变迁与影 响

后续的版权法修订与完善

01

02

03

1980年代

对1976年版权法进行了修 订,加强了对盗版行为的 打击力度,扩大了版权保 护的范围。

1990年代

随着数字技术的快速发展 ,版权法进行了多次修订 ,以适应新技术的挑战。

02

1976年之前的版权法概况

早期的版权法发展

1790年美国颁布了第一部版权 法,旨在保护作者的权益。

早期的版权法主要关注印刷出 版业,防止盗版和侵权行为。

随着技术的发展,版权法逐渐 扩展到其他媒体领域,如音乐 、电影和软件。

1976年之前的版权法主要内容

规定了版权保护的范 围和期限,以及侵权 行为的定义和处罚措 施。

设立了版权局,负责 注册和管理版权事务 。

强调了版权持有人的 权利,包括复制、发 行、表演和展示作品 等。

1976年之前版权法存在的问题

版权保护期限过长,导致一些经 典作品被垄断,无法广泛传播。

版权法对于数字技术的规定滞后 ,难以应对新兴的数字媒体和网

络技术。

版权法对于侵权行为的处罚力度 不够,难以有效遏制侵权行为。

1976年美国版权法的变迁

美国1976年《版权法》的产生与发展之启示王鑫秋

美国 1976 年《版权法》的产生与发展之启示王鑫秋发布时间:2023-06-29T09:44:33.514Z 来源:《时代教育》2023年8期作者:王鑫秋[导读] 美国是世界第一经济强国,经济的快速发展离不开文化的创作与技术的创新,因此国家对知识产权的保护就显得尤为重要。

1976年,美国国会决定全面修订其现有的版权法,美国的版权立法自此走进了新的时代。

1976年颁布的《版权法》奠定了当代美国版权制度的基础,本文将其发展与变迁作为研究对象,通过总结其版权立法的优缺点,对比世界其他版权强国的立法规则,为我国的版权制度发展提供借鉴。

西北政法大学国际法学院摘要:美国是世界第一经济强国,经济的快速发展离不开文化的创作与技术的创新,因此国家对知识产权的保护就显得尤为重要。

1976年,美国国会决定全面修订其现有的版权法,美国的版权立法自此走进了新的时代。

1976年颁布的《版权法》奠定了当代美国版权制度的基础,本文将其发展与变迁作为研究对象,通过总结其版权立法的优缺点,对比世界其他版权强国的立法规则,为我国的版权制度发展提供借鉴。

关键词:1976 年《版权法》;发展与变迁;美国引言在信息时代,所有国家对版权的认识都有了很大的提高。

版权是保护作者的文学和艺术创作及其传播的法律制度,对促进文化产业的创造和发展具有重要意义。

美国在版权保护方面处于世界领先地位,其完善的制度成为世界上其他国家版权保护的标准和基准。

受国家发展需求的影响,美国的版权制度主要经历了三个阶段,即产生、发展和完善。

在每个历史时期,美国都会根据社会发展的需要出台不同的版权法。

其中,《1976年版权法》为现代版权制度奠定了坚实的基础,为美国版权领域立法走向世界领先水平作出了贡献。

一、美国现行版权法的产生背景——1976年《版权法》美国版权法的法律渊源的核心内容源自美国宪法的第1章第8条1该条内容赋予作者及发明者对其创作享有专有性权利,后被称之为知识产权条款。

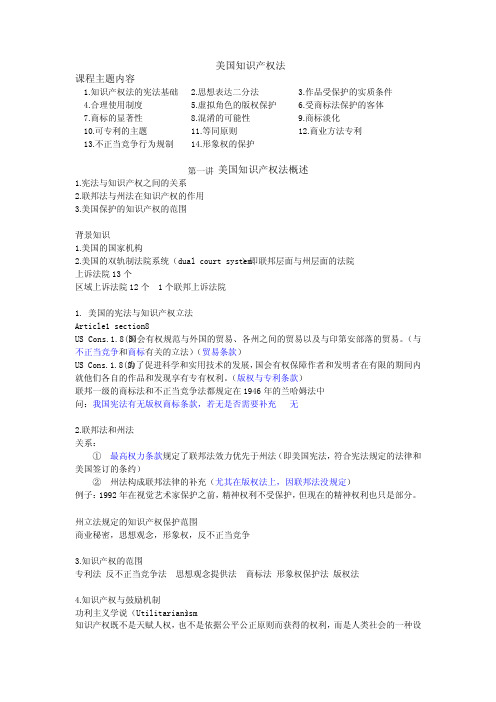

美国知识产权法

美国知识产权法课程主题内容1.知识产权法的宪法基础2.思想表达二分法3.作品受保护的实质条件4.合理使用制度5.虚拟角色的版权保护6.受商标法保护的客体7.商标的显著性 8.混淆的可能性 9.商标淡化10.可专利的主题 11.等同原则 12.商业方法专利13.不正当竞争行为规制 14.形象权的保护第一讲 美国知识产权法概述1.宪法与知识产权之间的关系2.联邦法与州法在知识产权的作用3.美国保护的知识产权的范围背景知识1.美国的国家机构)即联邦层面与州层面的法院2.美国的双轨制法院系统(dual court system上诉法院13个区域上诉法院12个 1个联邦上诉法院1.美国的宪法与知识产权立法Article1 section8国会有权规范与外国的贸易、各州之间的贸易以及与印第安部落的贸易。

(与US Cons.1.8(3)不正当竞争和商标有关的立法)(贸易条款)为了促进科学和实用技术的发展,国会有权保障作者和发明者在有限的期间内US Cons.1.8(8)就他们各自的作品和发现享有专有权利。

(版权与专利条款)联邦一级的商标法和不正当竞争法都规定在1946年的兰哈姆法中问:我国宪法有无版权商标条款,若无是否需要补充无2.联邦法和州法关系:①最高权力条款规定了联邦法效力优先于州法(即美国宪法,符合宪法规定的法律和美国签订的条约)②州法构成联邦法律的补充(尤其在版权法上,因联邦法没规定)例子:1992年在视觉艺术家保护之前,精神权利不受保护,但现在的精神权利也只是部分。

州立法规定的知识产权保护范围商业秘密,思想观念,形象权,反不正当竞争3.知识产权的范围专利法 反不正当竞争法 思想观念提供法 商标法 形象权保护法 版权法4.知识产权与鼓励机制)功利主义学说(Utilitarianism知识产权既不是天赋人权,也不是依据公平公正原则而获得的权利,而是人类社会的一种设计,以赋予某些智力劳动成果以财产权的方式,鼓励作者、发明者和商家创造出更多的信息产品,达到有利于社会的某种目的。

美国知识产权法保护创新和创造

美国知识产权法保护创新和创造知识产权是现代社会经济活动中的重要组成部分,它对创新和创造发挥着至关重要的作用。

美国作为一个非常重视知识产权保护的国家,通过制定和执行一系列法律法规,致力于保护知识产权,激励创新和创造力的发展。

本文将重点探讨美国的知识产权法及其对创新和创造的影响。

一、版权法版权法是知识产权保护的重要方面之一。

美国版权法的核心是通过保护原创作品的独立性和创造性来鼓励创新。

根据美国版权法,作品的原创作者拥有对其作品的独占使用权,包括复制、发行、展示、表演等权利。

这种保护机制有效地鼓励了各领域的创作者积极创作,促进了创新成果的产生和分享。

同时,美国版权法还设有一系列例外和限制,以确保公众能够在尊重版权的前提下使用作品,促进知识传播和文化繁荣。

例如,被称为“公平使用”的例外条款允许个人或机构在合理范围内使用已发表的作品,以教育、评论、新闻报道等方式进行创造性的使用。

二、专利法专利法是知识产权保护的另一个重要领域。

美国专利法通过授予发明者一定的专有权利,鼓励他们进行创新研究和技术发明。

专利法保护的是发明的技术方案,以确保发明者能够独占利用该技术并获得相应的经济利益。

美国的专利制度分为两种类型:实用新型专利和发明专利。

实用新型专利保护的是新颖的、实用的和非显而易见的技术方案,而发明专利则保护的是更具创造性和技术含量的发明。

专利权的授予有助于激励创新者在面临风险和困难时持续进行创新和研发工作。

三、商标法商标法是知识产权保护的另一个重要方面。

商标是用于标识和区分商品或服务来源的标志,其对企业的品牌形象和市场地位具有重要意义。

美国商标法通过注册商标,保护商标所有人的独占使用权,并确保消费者能够准确识别和区分不同品牌的商品或服务。

美国商标法要求商标具有独特性、可区别性和非功能性。

商标所有人可以通过商标使用许可协议授权他人使用其商标,并根据协议规定收取一定的使用费用。

商标保护不仅鼓励企业进行创新和品牌建设,也保护了消费者的利益,确保他们能够购买到可信赖的商品和服务。

美国著作权管理制度

美国著作权管理制度美国著作权管理制度是一套由政府监管和管理的法律框架,旨在保护作品作者的知识产权,并为其提供合法的权益保护和管理机制。

这一制度的核心目标是在保护创作者的作品免受盗版和侵权的同时,为其提供合法的收入来源和合作机会,以激励更多的人投身到文化创作和知识产出中。

本文将详细讨论美国的著作权管理制度,包括其法律框架、管理机构、运作机制及其应对新技术和数字化时代的挑战等各方面。

一、法律框架美国的著作权管理制度主要由一系列相关的法律和法规组成,其中最重要的包括《美国宪法》第一条第八款、《著作权法》和《数字千年版权法》等。

《美国宪法》第一条第八款授权国会有权制定著作权法,以保护作品作者的知识产权。

《著作权法》是美国立法历史最悠久的著作权法律之一,自1790年颁布以来经历了多次修订和更新。

它规定了哪些作品受到著作权保护、著作权持有者的权利和义务、侵权行为的法律后果等内容。

《数字千年版权法》则是针对数字化时代的新挑战而出台的,旨在加强对数字作品的版权保护和管理。

此外,美国还有一系列相关的法规和立法机构,如专利商标局、版权办公室、美国国际贸易委员会等,都与著作权管理有关。

这些法律和机构构成了美国著作权管理制度的法律框架,为行业的健康发展提供了有力的保障。

二、管理机构美国著作权管理制度涉及的管理机构众多,其中最重要的包括专利商标局和版权办公室。

专利商标局是负责管理专利、商标和版权的相关事务的联邦行政机构。

它负责审核和注册专利、商标和版权,向公众提供相关信息和咨询,协助维护知识产权,处理知识产权纠纷等。

作为著作权管理的机构之一,专利商标局扮演着重要的角色。

版权办公室则是专门负责管理著作权事务的机构。

它的主要职责包括审核和注册著作权申请、维护著作权数据库、协助著作权持有者维权、推动著作权法律和制度的更新和完善等。

版权办公室是美国著作权管理中的核心机构之一,对作品的版权保护和管理起着至关重要的作用。

除此之外,美国的著作权管理中还涉及了一系列相关的法庭、国际贸易机构、专业协会等,它们共同构成了一个多元化、协同合作的著作权管理机构体系。

[整理版]美国版权法

![[整理版]美国版权法](https://img.taocdn.com/s3/m/346c9a4aa2161479171128af.png)

美国版权法(修订至1987年9月30日止)第一章版权的客体和范围条次第101条定义第102条版权的客体:总类第103条版权的客体:编辑作品和演绎作品第104条版权的客体:作品的起源国第105条版权的客体:美国政府作品第106条有版权作品的专有权利第107条专有权利的限制:合理使用第108条专有权利的限制:图书馆和档案馆的复制第109条专有权利的限制:特定复制件或录音制品转移的效力第110条专有权利的限制:某些演出和展出的免责规定第11l条专有权利的限制:转播第l12条专有权利的限制:临时性录制品第l13条绘画、刻印和雕塑作品的专有权利的范围第114条录音作品的专有权利的范围第115条非戏剧音乐作品的专有权利的范围:制作和发行录音制品的强制许可证第116条非戏剧音乐作品的专有权利的范围:通过自动点唱机进行公开演奏第117条专有权利的限制:计算机程序第118条专有权利的范围:关于非商业广播对某些作品的使用第10l条定义本版权法专用名词及其各种不同形式的意义如下:“不具名作品”是在该作品的复制件或录音制品上无法识别任何自然人为其作者的作品。

“音像作品”是由一系列有关的图像所组成,目的是用机器或装置例如放映机、观察器或电子设备将其放映的作品,如伴有声音则连同声音一起放映,不论体现这类作品的物体例如影片或磁带的性质如何。

作品的“最佳版本”是在交存之日以前任何时候在美国出版的、并为国会图书馆确定的最适合该馆用途的版本。

某人的“子女”是某人的直接后代,不论合法与否,以及由某人合法收养的任何子女。

“集体作品”是期刊、选集或百科全书之类的作品,由一些本身单独独立的作品所组成,汇编成一个集体的整体。

“编辑作品”是通过收集和汇编原有的材料或经过选择、整理或安排的资料,使由此产生的作品作为整体构成作者的独创作品。

“编辑作品”一词包括集体作品在内。

“复制件”是除录音制品外,作品以现在已知的或以后发展的方法固定于其中的物体,通过该物体可直接地或借助于机器或装置感知、复制或用其他方式传播该作品。

美国版权法保护与实践

美国版权法保护与实践版权是指根据法律规定,作者对其创作的文学、艺术、音乐、戏剧等作品享有的专有权利。

版权保护的目的是鼓励创作,保护作者的合法权益,并促进文化艺术的繁荣发展。

美国版权法作为世界上最早确立的版权法律之一,对于保护作品的创作和传播起到了重要的作用。

本文将重点探讨美国版权法的核心内容以及其在实践中的应用。

一、版权保护的法律基础美国版权法保护与实践的根本依据是美国宪法第一条款。

该条款赋予国会权力,制定和执行版权和专利法律,以促进科学与文艺的进步。

根据美国版权法的规定,创作作品的版权拥有者享有以下权利:复制权、发行权、展览权、表演权、录音权和改编权。

这些权利允许版权拥有者对其作品进行控制,从而保护其合法权益。

二、版权登记及保护的方式在美国,版权的保护并不要求进行正式的登记手续。

根据美国版权局的规定,作品在创作完成的时候就自动拥有了版权保护。

然而,如果版权拥有者希望通过法律手段对他人侵权行为进行追究,建议进行正式的版权登记。

版权登记可以提供更充分的法律保护,并为版权拥有者提供了诉讼的基础。

美国版权法对于保护作品的形式并没有明确规定。

无论是文字作品、音乐作品、美术作品还是电影作品,只要符合原创性、独创性以及具有创造性的要求,都可以享受版权保护。

而对于具体的保护期限,美国版权法规定原则上为作者终身加上70年。

三、合理使用及公平使用原则美国版权法中还包含了合理使用及公平使用的原则。

合理使用是指在不侵犯版权拥有者权益的前提下,对作品的合理使用,例如学术研究、评论批评、新闻报道等。

公平使用是指在特定情况下,即使未经版权拥有者允许,他人也可使用作品,但应符合以下四个标准:使用目的、作品的性质、使用的数量和效果以及对市场潜在影响的评估。

四、数字化时代的版权问题随着互联网和数字技术的飞速发展,版权保护进入了一个全新的时代。

数字化时代带来了版权保护的难题,例如盗版、侵权等问题层出不穷。

针对这些问题,美国版权法不断进行修正和完善,加强对数字作品的保护。

{合同法律法规}美国法律中著作权侵权的认定.

{合同法律法规}美国法律中著作权侵权的认定导言n在理论上,可以从各个侧面研究一个国家的知识产权法,但从诉讼实务出发,最好采用诉讼流程式的思路。

n诉讼是一种攻防战。

知识产权诉讼亦不例外.一切诉讼理由可以视为发动进攻的武器与攻势;辩护理由则可以视为若干道防线与防御武器。

作为攻击方,你希望一切武器该用时都可以用得上;也希望了解对方的防御系统;作为防守方,你也希望了解对方手中的武器与战略。

n从防守方的角度来看,你不愿轻易放弃任何一道防线,也不愿将赌注都下在第一道防线上,也不愿让敌人长驱直入,兵临城下。

n在诉讼中,原告律师接受一桩案件以后,必然会首先考虑提出起诉有多少种诉讼理由,其次要考虑对方可能会提出哪些积极抗辩的理由;被告律师则首先要考虑对方的诉讼理由是否站得住脚,其次要考虑我方有哪些积极抗辩的理由n自我介绍:林晓云,纽约市立大学法学院兼职教授、德恒律师事务所全球合伙人、美国纽约与新泽西州执业律师,美中律师协会常务理事、候任副会长、《美国法通讯》总编,《牛津美国法律词典》中文版总编,先后毕业于美国威廉姆斯学院,美国路易斯克拉克学院,美国耶希瓦大学卡多佐法学院,分别获历史学士学位,行政管理硕士学位和法学博士学位n目前为全美律师协会(ABA)知识产权分会会员,美国知识产权协会(AIPLA)会员,持有纽约、新泽西州律师执照及美国联邦最高法院,联邦上诉法院第二巡回庭,纽约南区、东区及新泽西联邦地方法院庭辩资格.n主要著述有:•《美国货物买卖法案例判解》,法律出版社•《静悄悄的革命-中国的司法改革》,夏威夷大学法学院亚太地区法律与政策论丛》•《“彼得兔”商标究竟保护什么》,中国专利季刊•《外国专利申请与本国专利申请的同步性》、《通过CHEMNET应诉WIPO仲裁案看网络域名争端在中国的发生于解决》,美国马歇尔法学院知识产权中心《NEWS》季刊n另在《法制日报》、《二十一世纪经济报道》、《环球杂志》》、《中国日报》》、《侨报》》、《世界日报》等报刊上发表多篇法律时论文章。

美国版权法不保护字体字型和字库

美国版权法不保护字体、字型和字库李明德2011-11-22 10:43:48 来源:《电子知识产权》2011年第6期作者简介:李明德,现任中国社会科学院知识产权中心主任,法学研究所知识产权法研究室主任,中国社会科学院研究生院博士生导师。

摘要:早在数字化时代以前,美国的立法、行政和司法机关已经形成共识,印刷字体或者字型属于实用品,不能获得版权保护。

进入数字化时代以后,美国版权局延续这一思路,规定生成字体、字型和字库的计算机软件可以获得版权保护,但字体、字型和字库本身不能获得版权保护。

到了1992年,美国版权局还修改《版权注册规则》,明确规定数字化的字体不能获得版权注册。

关键词:字体,字型,字库,计算机软件,版权法近年来,我国产业界和一些学者都在呼吁,应当对字体、字型和字库给予著作权法的保护。

针对有关字体、字型和字库的诉讼,法院也做出了不尽一致的判决。

本文介绍美国版权法的相关做法,以期对我国的产业界、学术界和司法机关认识相关的问题,有所助益。

一早在20世纪中叶,美国的立法、行政和司法机关已经形成共识,印刷字体或者字型属于实用品,不应当获得版权保护。

因为,字体或者字型是用来撰写文章或者各种文本的工具,是一种具有功能性和实用性的产品,与版权保护无关。

根据当时的技术手段,设计者在创设新的字体或者字型时,要付出艰苦的智力劳动,草拟出成千上万张画稿,才能最终形成一套新的字体或者字型。

这似乎与作品的创作一样。

不过,这种种努力最后所形成的,仍然是具有实用性的工具,而非版权法保护的作品。

关于这一点,美国版权局的一个通告曾有过如下的说明:很多人认为,在创造新字体设计的过程中,艺术家花费了成千上万个小时的努力,以手工的方式绘制了很多字母和单词的图形,最后形成了具有原创性的字体设计。

然而,经过了数年的研究和公开听证,版权局发现,这种努力没有产生原创性的作品。

版权局拒绝注册有关字体设计或者字母和字型之图形的权利要求,因为这些设计反映了用于高速印刷之字型的功能性特征。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

• “solemnly adjudged in Great Britain, to be a right of common law.” • Statute of Anne 1709 (England)

– 14 years © plus another 14 if author still living – 21 years for works already published – Controversy over whether © endured at common law after expiry of statutory time limits – Millar v. Taylor (1769) 4 Burr. 2303, 98 ER 201

United States Copyright Law in International Perspective

Latest Developments in U.S. Copyright Law

Dr. Prof. Graeme W. Austin J. Byron Professor of Law, University of Arizona, USA Professorial Fellow, Melbourne University Law School, AUSTRALIA Honorary Fellow, Victoria University of Wellington, NZ

• Act of May 31, 1790, c. 15, 1 Stat. 124 § 1

– 14 year term – Additional 14 years if author survived

• § 1 limited copyright protection to person(s) “being a citizen or citizens of these United States, or residents therein”). Like the original state copyright laws, protection extended only to citizens of the United States. • Foreign-origin works were in the public domain.

• Rights endure at common law

– Donaldson v. Beckett (1774) 4 Burr. 2408

• Statute of Anne replaces the common law

• The public good fully coincides in both cases with the claims of individuals

• Early attempts to extend copyright protection to foreign (French and English) authors failed.

– S. Rep. No. 179, 24th Cong., 2d Sess. (1837): “*Limiting the © to nation-origin works] would have been hostile to the object of the power granted. That object was to promote the progress of science and useful arts. They belong to no particular country, but to mankind generally. And it cannot be doubted that the stimulus which it was intended to give to mind and genius . . . will be increased by the motives of which the bill offers to the inhabitants to Great Britain and France.”

• Governing U.S. philosophy: private (individual profit motive serves the public good) • “To promote the progress of science *knowledge+”

• The States cannot separately make effectual provisions for [copyright]

ቤተ መጻሕፍቲ ባይዱ

• It became a popular practice to reprint cheap editions of best-selling English books and sell them without the burden of royalties, a practice which infuriated both English authors who went uncompensated by the marketing of their books in America and American writers whose sales were undercut by cheap reprints of English books.

Lecture 1

Introduction

U.S. and International Copyright Relationships

1. Constitutional Initiatives

Federalist 43 (1788): A power “to promote the progress of science and useful arts, by securing, for a limited time, to authors and inventors, the exclusive right to their respective writings and discoveries.”

• This Bill failed to pass.

Charles Dickens (1842)

• “I spoke, as you know, of international copyright, at Boston; and I spoke of it again at Hartford. My friends were paralyzed with wonder at such audacious daring. The notion that I, a man alone by himself, in America, should venture to suggest to the Americans that there was one point on which they were neither just to their own countrymen nor to us, actually struck the boldest dumb! *…+ Every man who writes in this country is devoted to the question, and not one of them dares to raise his voice and complain of the atrocious state of the law. It is nothing that of all men living I am the greatest loser by it. It is nothing that I have a claim to speak and be heard. The wonder is that a breathing man can be found with temerity enough to suggest to the Americans the possibility of their having done wrong. *…+ My blood so boiled as I thought of the monstrous injustice that I felt as if I were twelve feet high when I thrust it down their throats.”

– Copyright Enactments of the United States (Solberg ed., 1906), at 11-14.

2.Federal Copyright Law (1790)

• Copyright legislation is empowered by art. I.8.8. of the federal constitution (1788)

• Articles of Confederation (preConstitution document) gave no power to enact copyright laws • Continental Congress passed a resolution encouraging states to pass copyright laws • All but one of the original states had copyright legislation

• The first copyright statute, passed by the Connecticut Assembly in 1783, afforded protection only to “the author of any book or pamphlet not yet printed, or of any map or chart, being an inhabitant or resident of these United States.” In the same year, the Massachusetts General Court issued a copyright statute that was similarly limited to “any subject of the United States.”