第二语言习得理论简介

第二语言习得理论

第二语言习得理论

一、第二语言习得基本概念

1. 习得与学习

2. 外语习得与第二语言习得

3. 语言习得机制

4. 中介语

5. 普遍语法

6. 母语迁移

7. 化石化

8. 教师语言、外国人话语

9. 显性学习与隐性学习

10. 个体差异

11. 认知风格

二、第二语言习得基本理论

1. 对比分析

(1)对比分析基本理论

(2)对比分析强势说及弱势说(3)对比分析的意义和局限2. 偏误分析

(1)偏误分析理论背景

(2)偏误和错误的区分

(3)偏误分析研究的步骤(4)偏误的五个来源

(5)偏误分析的贡献

(6)偏误分析的局限

(7)汉语偏误分析研究

3. 克拉申语言习得假说

(1)习得与学习假说

(2)自然习得顺序假说

(3)输入假说

(4)监控假说

(5)情感过滤假说

4. 内在大纲

5. 文化适应理论

6. 学习者语言变异能力

三、个体差异与学习策略

1. 关键期假说

2. 语言学能

3. 工具型动机与融合型动机

4. 语言习得态度

5. 学习者焦虑

6. 认知策略

7. 元认知策略

8. 补偿策略

9. 记忆策略

10. 社会策略

11. 情感策略

12. 场独立与场依存

13. 语言自我

14. 歧义容忍度

版权所有转载请注明来源:中国语言资源中心

相关链接:2009对外汉语教师资格考试/s/blog_4835e3000100f44j.html。

第二语言习得

第二语言习得理论第二语言习得基本概念1.习得与学习:语言习得是一种下意识的过程,类似于儿童习得母语的方式;学习是有意识地学习语言知识,能够明确地意识到所学的规则。

区别:A.目的性:习得是一种潜意识的行为,目的性不明确;学习则是主体为了掌握一种新的交际工具所进行的目的性非常明确的活动,是一种有意识的行为。

B.环境:习得一般是在使用该目的语的社会环境中进行的;学习主要在课堂环境下进行,可能有目的语环境,也可能没有。

C.注意点:习得时注意力主要集中在语言的功能和意义上;学习的主要注意点在语言形式上,有意识的系统的掌握语音、词汇、语法,却经常忽视了语言的意义。

D.学习途径:习得的方法主要靠自然语言环境中的语言交际活动,没有教材和大纲;学习是在教师指导下通过模仿和练习来掌握语言规则。

E.时间:习得需要大量的时间,习得效果一般很好;学习花费时间一般很少,但学习效果通常不佳。

F.有无意识:习得是潜意识的自然的获得;学习是有意识的规则的掌握。

2、外语习得与第二语言习得:外语习得是指学习者在非目的语国家学习目的语。

第二语言习得是指学习者在目的语国家学习目的语。

学习者所学的目的语在目的语国家是公认的交际工具,也是学习者用来交际的工具。

3、语言习得机制:它脱离人类的其他功能而独立存在,与智力无关。

语言习得机制包括两部分:一部分是以待定的参数形式出现的、人类语言所普遍具有的语言原则,又称为“普遍语法”。

第二部分是评价语言信息的能力,也就是对所接触到的实际语言的核心部分进行语言参数的定值。

4、中介语:1969年由美国语言学家塞林克提出的,是指在第二语言习得中形成的一种既不同于母语也有别于目的语、随着学习的进展不断向目的语过渡的动态语言系统。

中介语理论有利于探索学习者语言系统的本质,发现第二语言习得的发展阶段,揭示第二语言的习得过程及第一语言的影响。

5、普遍语法:语言习得机制包括两个方面:一部分以待定的参形式出现的、人类语言所普遍具有的语言原则。

克拉申 语言习得理论

二语习得理论克拉申理论克拉申的第二语言习得理论(又称“监控理论”)。

此理论主要由五大假说组成:习得/学得假说(the Acquisition /Learning Hypothesis),自然顺序假说(the Natural Order Hypothesis),监控假说(the Monitor Hypothesis),输入假说(the Input Hypothesis)和情感过滤假说(the Affective Hypothesis) [1] [2]一、克拉申的语言习得理论(一)习得/学得假说习得/学得假说是克拉申所有假说中最基本的一个,是其第二语言习得理论的基础。

这一假说认为:发展第二语言能力有两个独立的途径:“习得”是下意识过程,与儿童习得母语的过程,在所有的重要方面都是一致的;“学得”则是有意识过程,通过这一过程,可“了解语言”(即获得有关语言的知识)。

“习得”是潜意识(subconscious)过程,是注重意义的自然交际结果,正如儿童母语习得过程。

“学得”(learning),是有意识(conscious)的过程,即通过课堂教师讲授并辅之以有意识的练习、记忆等活动达到对所学语言的掌握。

Krashen认为成人学习第二语言可以通过两种方式——语言习得(language acquisition)和语言学得(language learning)。

语言是潜意识过程的产物。

这一过程和孩子们学习母语的过程很相似。

它要求学习者用目的语进行有意义的、自然的交流。

在交流过程中学习者所关注的是交流活动本身,而不是语言形式。

语言习得则是正式教育的产物。

正式教育是一个有意识的过程,其结果是学习者能获得一些有意识的和语言相关的知识。

Krashen指出学得不能转换成习得。

例如,使用母语者尽管不懂语法规则,却可以正确流利地使用该语言,而语言学习者虽然有完备的语法知识,却很难在实际交流中运用自如。

因此,对二语习得来讲,自然的语言环境比有意识的学习更为有效。

二语习得理论

第一阶段:沉默期语言学家克拉申(Krashen)的理论,儿童在习得母语时,总是经历一个为期大约一年的“听”的过程(沉默期),然后才开口说出第一个词。

这一规律同样适合于第二语言习得。

第二语沉默期的长短因人而异,有的只要一天,有的则要半年或更久。

Krashen认为“沉默期”是使习得者建立语言能力的一个非常必要的时期。

在沉默期这段时间里,儿童通过“听”来提高语言能力,也就是说,通过接受可理解的语言输入来发展语言能力。

第二阶段:英语语法干扰期刚从沉默期走出来的孩子,刚刚学会开始应用第二语言,但是错误非常多,不习惯第二语言的规则。

语法干扰期是掌握语言的必经阶段。

孩子尝试着把语言按照一定规则组织起来,创造出大量的表达方式(其中有很多错误)。

这是儿童掌握语法规则,建立语感的必然方式。

第三阶段:学术英语提高期孩子可以讲英语了,家长就认为完成了英语学习任务,其实这只是证明日常口语学习部分达到了一个水平,但是掌握的不全面。

许多中国孩子进入美国课堂学习时发现课本看不懂,学科词汇听不懂。

原因在于他们并没有掌握学术英语知识。

而这方面知识对于孩子的学科应用水平和日后的工作交流起到至关重要的作用。

学好学术语言可以为孩子搭建另一片广阔天地,可以让中国孩子更深入的理解异国文化,可以训练孩子的多元学科思维,也可以使孩子更快融入国际交流,成为一个地地道道的小国际人!作为家长要暗示孩子继续探索学习,鼓励他们多了解学科知识,让他们对学术英语感兴趣。

第四阶段:学习曲线上升期达到英语学习一个阶段后孩子的提高水平趋于缓慢,多数家长这时看不到孩子有明显进步就会施加很大压力给他们,担心孩子英语水平下降。

专家提醒家长不要焦虑学习中出现的曲线期,这是每个学习者遵循的自然规律,只要坚持不懈,按照既定的目标发展会突破平缓期,继续提高英文水平。

教育技巧第一阶段:沉默期语言学家克拉申(Krashen)研究发现:儿童在习得母语时,要经历为期大约一年的“听”的过程(沉默期),然后才开口说出第一个词。

第二语言习得主要理论和假说

第二语言习得主要理论和假说一、对比分析假说(行为主义:刺激—反应—强化形成习惯)代表:拉多定义:第一语言习惯迁移问题。

两种语言结构特征相同之处产生正迁移,两种语言的差异导致负迁移。

负迁移造成第二语言习得的困难和学生的错误。

主张:第二语言习得的主要障碍来自第一语言的干扰,需要通过对比两种语言结构的异同来预测第二语言习得的难点和错误,以便在教学中采用强化手段突出重点和难点,克服母语的干扰并建立新的习惯。

影响:积极:听说法和是视听法,特别是句型替换练习的理论基础。

消极:根本缺陷——否认学习者的认知过程,忽视人的能动性和创造力。

二、中介语假说代表:塞林克基础:普遍语法理论和先天论的母语习得理论定义:中介语是指在第二语言习得过程中,学习者通过一定的学习策略,在目的语输入的基础上所形成的介于第一语言和目的语之间、随着学习进展向目的语逐渐过渡的动态的语言系统。

特点:1.中介语在其发展的任何一个阶段都是介于第一语言和目的语之间的独特的语言系统。

2.中介语是一个不断变化的动态语言系统3.中介语是由于学习者对目的语规律尚未完全掌握,所做的不全面的归纳与推论。

4.中介语的偏误有反复性5.中介语的偏误有顽固性。

在语音上易产生“僵化”或“化石化”现象。

意义:是探索第二语言习得者在习得过程中的语言系统和习得规律的假说。

把第二语言获得看做是一个逐渐积累完善的连续的过程,而且看做是学习者不断通过假设—验证主动发现规律、调整修订所获得的规律,对原有知识结构进行重组并逐渐创建目的语系统的过程。

三、内在大纲和习得顺序假说代表:科德《学习者言语错误的重要意义》反映内在大纲偏误定义:第二语言学习者在语言习得过程中有其自己的内在大纲,而学习者的种种偏误正是这种内在大纲的反映。

第二语言习得理论评介

第二语言习得理论评介

第二语言习得理论是外语教学研究领域非常重要的一环,它探究普通人是如何在一定教学环境中学习新语言,以实现丰富外语知识的目的,它主要考虑了以下几个层面。

首先,第二语言习得理论强调了“现象意识”,或者可以把它称作“知识意识”,即在习得新语言过程中,学习者了解新学习的语言的特点,词汇、句法,乃至对文化背景的熟悉和了解。

其次,通过对宣传语或利用不同的认知手段,第二语言习得理论倡导学习者探索这种新语言,他们可以从多个角度分析语言现象,加深对语言本身的了解。

再者,一般来说,语言学习者应具备理解和反思的能力,这是习得新语言的基本必需条件。

熟悉语言的过程,即探索中开发出来的思考过程,可以帮助学习者反思自己的语言表达,从而更好地掌握和应用新学习的语言。

最后,第二语言习得理论还引入了大量的教学手段与元素,以此判定语言学习者学习情况,以及优化语言学习过程。

通过对历史性、文化性语言意义、句法形式和潜藏语义等方面的加强,从而得到有效的语言习得。

综上所述,第二语言习得理论从理论研究和实践应用多方面探究了语言习得过程,以期加深我们对语言习得方面的知识,以及提升语言学习者学习手段和效率。

二语习得理论__中文

(一) 乔姆斯基的普遍语法与二语习得乔姆斯基和其支持者们认为 ,遗传基因赋予人类普遍的语言专门知识 ,他把这种先天知识称之为“普遍语法”。

他们的主要论点是 ,假如没有这种天赋 ,无论是第一语言还是第二语言的习得将是不可能的事情 ,原因是在语言习得过程中 ,语言数据的输入(input )是不充分的 ,不足以促使习得的产生。

乔姆斯基认为 ,语言是说话人心理活动的结果 ,婴儿天生就有一种学习语言的能力 ,对他们的语言错误不须纠正 ,随着年龄的增长他们会在生活实践中自我纠正。

有的人在运用语言时 ,总是用语法来进行核对 ,以保证不出错误 ,这就是所谓通过学习来进行监控的[ 1 ] (P19)。

随着语言水平的不断提高 ,这种监控的使用会逐渐越来越少。

从本质上说 , 语言不是靠“学习”获得的 , 只要语言输入中有足够的正面证据 ,任何一个正常人都能习得语言。

(二) 克拉申的监控理论在 20 世纪末影响最大的二语习得理论当数克拉申的监控理论(Monitor Theory) 。

他把监控论归结为 5 项基本假说:语言习得与学习假说、自然顺序假说、监控假说、语言输入假说和情感过滤假说。

克氏认为第二语言习得涉及两个不同的过程:习得过程和学得过程。

所谓“习得”是指学习者通过与外界的交际实践 ,无意识地吸收到该种语言 ,并在无意识的情况下 ,流利、正确地使用该语言。

而“学习”是指有意识地研究且以理智的方式来理解某种语言(一般指母语之外的第二语言)的过程。

克拉申的监控假说认为 ,通过“习得”而掌握某种语言的人 ,能够轻松流利地使用该语言进行交流;而通过“学得”而掌握某种语言的人 ,只能运用该语言的规则进行语言的本监控。

通过一种语言的学习 ,我们发现,“习得”方式比“学得”方式显得更为重要。

自然顺序假说认为第二语言的规则是按照可以预示的顺序习得的 ,某些规则的掌握往往要先于另一些规则 ,这种顺序具有普遍性 ,与课堂教学顺序无关。

二语习得理论

二语习得的主要倡导人克拉申认为:简单来说,语言的掌握,无论是第一语言还是第二语言,都是在“可理解的”真实语句发生(即我们前面探讨的有效的声音,也就是可以懂意思的外语)下实现的;都是在放松的不反感的条件下接受的;它不需要“有意识地”学习,训练和使用语法知识;它不能一夜速成,开始时会比较慢,说的能力比听的能力实现得晚。

所以最好的方法就是针对以上语言实现的特点来设计的.他的理论由以下五大支柱组成,被他称为五个“假说”.五个假说不分先后,但分量不同,下面一一说明:1.习得--学得差异假设(The Acquisition—Learning Hypothesis)成人是通过两条截然不同的途径逐步掌握第二语言能力的。

第一条途径是“语言悉得”,这一过程类似于儿童母语能力发展的过程,是一种无意识地、自然而然地学习第二语言的过程。

第二条途径是“语言学习",即通过听教师讲解语言现象和语法规则,并辅之以有意识的练习、记忆等活动,达到对所学语言的了解和对其语法概念的“掌握”。

悉得的结果是潜意识的语言能力;而学得的结果是对语言结构有意识的掌握。

该假设认为,成年人并未失去儿童学语言的能力。

克拉申甚至认为,如果给予非常理想的条件,成人掌握语言的能力还要比儿童强些。

他同时还认为,别人在旁帮你纠正错误,对你的语言掌握是没有什么帮助的.这一点中国同学值得注意.2.自然顺序假设(The Natural Order Hypothesis)这一假设认为,无论儿童或成人,语法结构的悉得实际上是按可以预测的一定顺序进行的。

也就是说,有些语法结构先悉得,另一些语法结构后悉得。

克拉申指出,自然顺序假设并不要求人们按这种顺序来制定教学大纲.实际上,如果我们的目的是要悉得某种语言能力的话,那么就有理由不按任何语法顺序来教学。

初学时的语法错误是很难避免的,也是没必要太介意的。

3. 监检假设(The Monitor Hypothesis)一般说来,下意识的语言悉得是使我们说话流利的原因;而理性的语言学习只起监检或“编辑”的作用。

第二语言习得理论概述

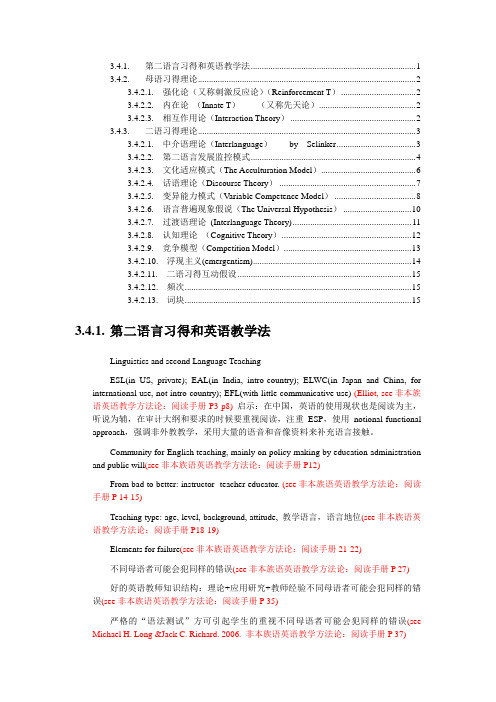

3.4.1. 第二语言习得和英语教学法 (1)3.4.2. 母语习得理论 (2)3.4.2.1. 强化论(又称刺激反应论)(Reinforcement T) (2)3.4.2.2. 内在论(Innate T)(又称先天论) (2)3.4.2.3. 相互作用论(Interaction Theory) (2)3.4.3. 二语习得理论 (3)3.4.2.1. 中介语理论(Interlanguage)by Selinker (3)3.4.2.2. 第二语言发展监控模式 (4)3.4.2.3. 文化适应模式(The Acculturation Model) (6)3.4.2.4. 话语理论(Discourse Theory) (7)3.4.2.5. 变异能力模式(Variable Competence Model) (8)3.4.2.6. 语言普遍现象假说(The Universal Hypothesis) (10)3.4.2.7. 过渡语理论(Interlanguage Theory) (11)3.4.2.8. 认知理论(Cognitive Theory) (12)3.4.2.9. 竞争模型(Competition Model) (13)3.4.2.10. 浮现主义(emergentism) (14)3.4.2.11. 二语习得互动假设 (15)3.4.2.12. 频次 (15)3.4.2.13. 词块 (15)3.4.1.第二语言习得和英语教学法Linguistics and second Language TeachingESL(in US, private); EAL(in India, intro-country); ELWC(in Japan and China, for international use, not intro-country); EFL(with little communicative use) (Elliot, see非本族语英语教学方法论:阅读手册P3-p8) 启示:在中国,英语的使用现状也是阅读为主,听说为辅,在审计大纲和要求的时候要重视阅读,注重ESP,使用notional-functional approach,强调非外教教学,采用大量的语音和音像资料来补充语言接触。

二语习得

第二语言习得理论第一章绪论一、什么是第二语言习得理论第二语言习得理论(二语习得理论)系统地研究第二语言习得的本质和习得的过程。

具体地说,第二语言习得理论研究第二语言习得的心理过程、认知过程或语言过程,研究学习者在掌握了母语之后是如何学习另一套新的语言体系的,研究在学习新的语言体系的过程中出现的偏误,研究语言教学对语言习得的影响,研究学习者母语对第二语言习得的影响,也研究学习者之间存在的巨大个人差异等等。

概括地讲,第二语言习得研究有两个主要目标:首先是描写第二语言习得过程,即研究学习者整体的语言能力和各项具体技能是如何发展起来的。

它要对这个过程中的一些内在的规律和现象进行研究和分析,比如要研究学习过程中习得一种语言的模式,语言发展的模式,语言成分的习得顺序,出现的偏误,中介语等等。

其次是解释第二语言习得,也就是说明为什么学习者能够习得第二语言?哪些外在的因素和内在的因素对第二语言习得起着正面的促进作用或负面的阻碍作用。

二、第二语言习得和外语学习第二语言习得涉及到几个基本概念:第二语言、习得和第二语言习得。

下面我们和传统的外语教学中相应的术语一起来看一下这些术语的内涵。

1.第二语言和外语第二语言(二语)和外语是二语习得研究中使用频率颇高的两个术语。

对第二语言这个术语有广义和狭义的两种不同理解,广义的理解通常指母语以外的另外一种语言,狭义的理解特指双语或者多语环境中母语以外的另一门语言,能常是指在本国有与母语同等或更重要地位的一种语言。

在这个意义上,它和外语是不同的,外语一般指在本国之外使用或学习的语言,学习者一般是在课堂上学习这种语言。

这一区分具有研究上的意义,因为两者在学习的内容和学习的方式及学习的环境上有很大区别,但是这种区别到底在多大程度上影响语言学习的过程和结果,我们现在还不是特别清楚。

实际上,从本质上看,两者都是学习母语之外的另一种语言,所以有人对这两个术语也有不加区分的。

第二语言习得中的第二语言是从广义上理解的,这里的二语可以泛指任何一种在母语之后习得的语言,它可以指狭义的二语,也可以指外语。

第二语言习得的理论与实践

第二语言习得的理论与实践第二语言习得(Second Language Acquisition,SLA)是指个体在母语习得之后,对另一种语言的学习和掌握过程。

这一领域涉及心理学、语言学、社会学等多个学科,旨在探究学习者如何在不同环境下有效地习得第二语言。

本文将介绍几种主流的第二语言习得理论,并探讨其在实际教学中的应用。

行为主义理论行为主义理论认为语言习得是一个习惯形成的过程。

通过刺激-反应机制,学习者对环境中的语言输入做出反应,并逐渐形成正确的语言习惯。

在教学中,这一理论强调模仿和重复练习,如语音训练和句型操练,以帮助学生形成正确的语言习惯。

认知理论认知理论强调学习者内部心理活动的作用,认为语言习得是一个信息处理的过程。

学习者需要对输入的语言材料进行加工、储存和提取。

在教学上,认知理论倡导有意义的学习任务和策略训练,鼓励学生通过解决问题来学习语言。

社会文化理论社会文化理论认为语言习得是社会互动和文化参与的结果。

学习者在与他人的交流中逐步掌握语言。

这一理论强调社会环境的重要性,提倡使用真实的语言材料和情境,鼓励学生通过合作学习和角色扮演等活动提高语言能力。

输入假说输入假说由斯蒂芬·克拉申提出,主张学习者通过理解略高于当前水平的语言输入(i+1)来习得语言。

在教学实践中,这意味着教师应提供足够多的可理解输入,如听力和阅读材料,以促进学生的语言发展。

输出假说输出假说由梅瑞尔·斯温提出,强调语言产出在语言习得中的作用。

学习者通过尝试使用目标语言来检验自己的假设,并通过反馈进行调整。

教学中,鼓励学生积极参与口语和写作练习,以提高他们的语言能力。

应用实例在实际教学中,教师可以根据不同的理论设计教学活动。

例如,根据行为主义理论,可以设计模仿练习;根据认知理论,可以设置问题解决任务;根据社会文化理论,可以组织小组讨论;根据输入假说,可以提供大量的阅读材料;根据输出假说,可以安排演讲和写作作业。

第二语言习得理论

第二语言学习理论有些教课法 , 如“自然法”( Natural Approach ) 就是成立在某一学习理论( 克拉申的督查模式) 的基础上的。

有些教课法是以某一学习理论和某一语言理论作依照而创办起来的 ( 如听闻法 ) 。

对语言学习理论的掌握 , 能帮助我们认识已创办起来的教课方法 , 也能促进我们以这些学习理论为依照去进行英语教课法的研究。

外语学习理论是商讨外语学习广泛性和规律性的研究 , 行为主义的学习观、认知主义的习得理论、克拉申的二语习得学说等属于这种研究。

一、行为主义的学习理论行为主义产生于20 世纪 20 年月 , 华生 (J.B.Watson)是它初期的代表人物。

华生研究动物和人的心理。

华生以为人和动物的行为有一个共同的要素和反响。

心理学只关怀外面刺激如何决定某种反响。

在华生看来切复杂行为都是在环境的影响下由学习而获取的。

他提出了行为主义心理学的公式刺激——反响 ( S-R, Stimulus-Response) 。

, 即刺激, 动物和人的一构造主义大师布洛姆菲尔德模式作为其理论依照。

( L.Bloomfield ) 以行为主义的“刺激——反响”Jack 让 Jill 摘苹果说明S-R 语言行为模式Jill ’ s hunger (S)“I ’m hungry”(r)Jack ’ s hearing (s)Jack ’ s action (R)布洛姆菲尔德重视作为声音r, .s 语言行为的研究, 他以为 r, s 是物理的声波 , 进而得出语言教课过程的理论 , 即在语言教课中教师对学生进行声音刺激 , 学生对声音刺激进行反响。

斯金纳 ( B.F.Skinner ) 继承和发展了华生的行为主义。

斯金纳以为人们的语言、语言的每一部分都是因为某种刺激的存在而产生的。

这里讲的“某种刺激”可能是语言的刺激 , 也可能是外面的刺激或是内部的刺激。

一个人在口渴时会讲出“ I would like a glass of water. ”。

二语习得理论在汉语教学中的应用

二语习得理论在汉语教学中的应用随着全球经济发展的日益加速,汉语已成为世界上越来越多人学习的语言。

在汉语国际教育中,如何有效地教授汉语成为了一个重要的问题。

而二语习得理论作为一个重要的教育学理论,可以为汉语教学提供很好的启示与指导。

一、二语习得理论的基本假设二语习得理论是由古曼和克鲁茨于1977年提出的,它认为第二语言习得是一种自然的心理过程,其特点是学习者由无意识的感知逐渐转向意识的规则学习,最终形成一个内在的语言系统。

在这个过程中,语言输入和输出、意识和不意识的语言认知运作、语言环境和学习者自身的因素都会对语言学习产生影响。

二、 1. 提供多样化的语言输入二语习得理论认为,要使学生能够习得第二语言,必须让他们接触到大量的外语输入。

在汉语教学中,应该通过多种方式提供学生汉语输入,比如说汉语课堂对话、听力材料、媒体新闻、文学作品等,同时也可以鼓励学生自己寻找汉语输入资源,比如说汉语电影、网站、音乐等。

2. 建立愉悦的学习氛围二语习得理论认为,学习者的情感状态和态度会对语言习得过程产生影响。

如果学生在学习汉语时感到无聊、焦虑或不快,那么他们的学习效果就会大打折扣。

因此,在汉语教学中,应该创造出轻松、愉悦的学习氛围,比如说组织游戏、实践活动和文化体验等。

同时,也应该为学生提供足够的支持和鼓励,使他们更加自信和积极地学习汉语。

3. 倡导学习策略的培养二语习得理论认为,学习者必须积极主动地参与到语言学习中,才能更好地习得外语。

因此,在汉语教学中,应该积极培养学生的学习策略。

这些策略可以包括制定学习计划、注意汉字拼音的学习、利用语感进行口语训练、寻找语音、语法、词汇差异等间接证据进行学习等等。

通过这些策略的应用,学习者可以更加自主地学习汉语,提高汉语的习得效率。

4. 坚持语境导向的教学二语习得理论认为,在语言习得过程中,学习者需要学会将语言知识应用到语境中,才能真正掌握语言规则。

因此,在汉语教学中,要坚持语境导向的教学,让学生通过实际应用汉语的场景来学习语言知识。

第二语言习得理论(来自维基百科)

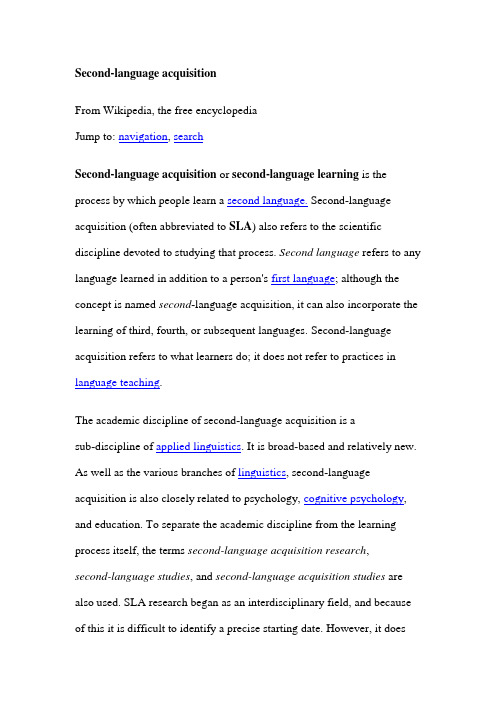

Second-language acquisitionFrom Wikipedia, the free encyclopediaJump to: navigation, searchSecond-language acquisition or second-language learning is the process by which people learn a second language. Second-language acquisition (often abbreviated to SLA) also refers to the scientific discipline devoted to studying that process. Second language refers to any language learned in addition to a person's first language; although the concept is named second-language acquisition, it can also incorporate the learning of third, fourth, or subsequent languages. Second-language acquisition refers to what learners do; it does not refer to practices in language teaching.The academic discipline of second-language acquisition is asub-discipline of applied linguistics. It is broad-based and relatively new. As well as the various branches of linguistics, second-language acquisition is also closely related to psychology, cognitive psychology, and education. To separate the academic discipline from the learning process itself, the terms second-language acquisition research,second-language studies, and second-language acquisition studies are also used. SLA research began as an interdisciplinary field, and because of this it is difficult to identify a precise starting date. However, it doesappear to have developed a great deal since the mid-1960s.The term acquisition was originally used to emphasize the subconscious nature of the learning process, but in recent years learning and acquisition have become largely synonymous.Second-language acquisition can incorporate heritage language learning, but it does not usually incorporate bilingualism. Most SLA researchers see bilingualism as being the end result of learning a language, not the process itself, and see the term as referring to native-like fluency. Writers in fields such as education and psychology, however, often use bilingualism loosely to refer to all forms of multilingualism.Second-language acquisition is also not to be contrasted with the acquisition of a foreign language; rather, the learning of second languages and the learning of foreign languages involve the same fundamental processes in different situations.There has been much debate about exactly how language is learned, and many issues are still unresolved. There are many theories ofsecond-language acquisition, but none are accepted as a complete explanation by all SLA researchers. Due to the interdisciplinary nature of the field of second-language acquisition, this is not expected to happen in the foreseeable future.HistoryAs SLA began as an interdisciplinary field, it is hard to pin down a precise starting date.[2] However, there are two publications in particular that are seen as instrumental to the development of the modern study of SLA: Pitt Corder's 1967 essay The Significance of Learners' Errors, and Larry Selinker's 1972 article Interlanguage. Corder's essay rejected a behaviorist account of SLA and suggested that learners made use of intrinsic internal linguistic processes; Selinker's article argued that second language learners possess their own individual linguistic systems that are independent from both the first and second languages.[7]In the 1970s the general trend in SLA was for research exploring the ideas of Corder and Selinker, and refuting behaviorist theories of language acquisition. Examples include research into error analysis, studies in transitional stages of second-language ability, and the "morpheme studies" investigating the order in which learners acquired linguistic features. The 70s were dominated by naturalistic studies of people learning English as a second language.[7]By the 1980s, the theories of Stephen Krashen had become the prominent paradigm in SLA. In his theories, often collectively known as the Input Hypothesis, Krashen suggested that language acquisition is driven solely by comprehensible input, language input that learners can understand. Krashen's model was influential in the field of SLA and also had a largeinfluence on language teaching, but it left some important processes in SLA unexplained. Research in the 1980s was characterized by the attempt to fill in these gaps. Some approaches included Lydia White's descriptions of learner competence, and Manfred Pienemann's use of speech processing models and lexical functional grammar to explain learner output. This period also saw the beginning of approaches based in other disciplines, such as the psychological approach of connectionism.[7] The 1990s saw a host of new theories introduced to the field, such as Michael Long's interaction hypothesis, Merrill Swain's output hypothesis, and Richard Schmidt's noticing hypothesis. However, the two main areas of research interest were linguistic theories of SLA based upon Noam Chomsky's universal grammar, and psychological approaches such as skill acquisition theory and connectionism. The latter category also saw the new theories of processability and input processing in this time period. The 1990s also saw the introduction of sociocultural theory, an approach to explain second-language acquisition in terms of the social environment of the learner.[7]In the 2000s research was focused on much the same areas as in the1990s, with research split into two main camps of linguistic and psychological approaches. VanPatten and Benati do not see this state of affairs as changing in the near future, pointing to the support both areas ofresearch have in the wider fields of linguistics and psychology, respectively.[7]Comparisons with first-language acquisitionPeople who learn a second language differ from children learning their first language in a number of ways. Perhaps the most striking of these is that very few adult second-language learners reach the same competence as native speakers of that language. Children learning a second language are more likely to achieve native-like fluency than adults, but in general it is very rare for someone speaking a second language to pass completely for a native speaker. When a learner's speech plateaus in this way it is known as fossilization.In addition, some errors that second-language learners make in their speech originate in their first language. For example, Spanish speakers learning English may say "Is raining" rather than "It is raining", leaving out the subject of the sentence. French speakers learning English, however, do not usually make the same mistake. This is because sentence subjects can be left out in Spanish, but not in French.[8] This influence of the first language on the second is known as language transfer.Also, when people learn a second language, the way they speak their first language changes in subtle ways. These changes can be with any aspectof language, from pronunciation and syntax to gestures the learner makes and the things they tend to notice.[9] For example, French speakers who spoke English as a second language pronounced the /t/ sound in French differently from monolingual French speakers.[10] This effect of the second language on the first led Vivian Cook to propose the idea ofmulti-competence, which sees the different languages a person speaks not as separate systems, but as related systems in their mind.[11]Learner languageLearner language is the written or spoken language produced by a learner. It is also the main type of data used in second-language acquisition research.[12] Much research in second-language acquisition is concerned with the internal representations of a language in the mind of the learner, and in how those representations change over time. It is not yet possibleto inspect these representations directly with brain scans or similar techniques, so SLA researchers are forced to make inferences about these rules from learners' speech or writing.[13]Item and system learningThere are two types of learning that second-language learners engage in. The first is item learning, or the learning of formulaic chunks of language. These chunks can be individual words, set phrases, or formulas like Can Ihave a ___? The second kind of learning is system learning, or the learning of systematic rules.[14]InterlanguageMain article: InterlanguageOriginally, attempts to describe learner language were based on comparing different languages and on analyzing learners' errors. However, these approaches weren't able to predict all the errors that learners made when in the process of learning a second language. For example,Serbo-Croat speakers learning English may say "What does Pat doing now?", although this is not a valid sentence in either language.[15]To explain these kind of systematic errors, the idea of the interlanguage was developed.[16] An interlanguage is an emerging language system in the mind of a second-language learner. A learner's interlanguage is not a deficient version of the language being learned filled with random errors, nor is it a language purely based on errors introduced from the learner's first language. Rather, it is a language in its own right, with its own systematic rules.[17] It is possible to view most aspects of language from an interlanguage perspective, including grammar, phonology, lexicon, and pragmatics.There are three different processes that influence the creation of interlanguages:[15]∙Language transfer. Learners fall back on their mother tongue to help create their language system. This is now recognized not as a mistake, but as a process that all learners go through.∙Overgeneralization. Learners use rules from the second language in a way that native speakers would not. For example, a learnermay say "I goed home", overgeneralizing the English rule ofadding -ed to create past tense verb forms.∙Simplification. Learners use a highly simplified form of language, similar to speech by children or in pidgins. This may be related to linguistic universals.The concept of interlanguage has become very widespread in SLA research, and is often a basic assumption made by researchers.[17] Sequences of acquisitionMain article: Order of acquisitionIn the 1970s several studies investigated the order in which learners acquired different grammatical structures.[19] These studies showed that there was little change in this order among learners with different first languages. Furthermore, it showed that the order was the same for adults and children, and that it did not even change if the learner had languagelessons. This proved that there were factors other than language transfer involved in learning second languages, and was a strong confirmation of the concept of interlanguage.However, the studies did not find that the orders were exactly the same. Although there were remarkable similarities in the order in which all learners learned second-language grammar, there were still some differences among individuals and among learners with different first languages. It is also difficult to tell when exactly a grammatical structure has been learned, as learners may use structures correctly in some situations but not in others. Thus it is more accurate to speak of sequences of acquisition, where particular grammatical features in a language have a fixed sequence of development, but the overall order of acquisition is less rigid.VariabilityAlthough second-language acquisition proceeds in discrete sequences, it does not progress from one step of a sequence to the next in an orderly fashion. There can be considerable variability in features of learners' interlanguage while progressing from one stage to the next.[20] For example, in one study by Rod Ellis a learner used both "No look my card" and "Don't look my card" while playing a game of bingo.[21] A small fraction of variation in interlanguage is free variation, when thelearner uses two forms interchangeably. However, most variation is systemic variation, variation which depends on the context of utterances the learner makes.[20] Forms can vary depending on linguistic context, such as whether the subject of a sentence is a pronoun or a noun; they can vary depending on social context, such as using formal expressions with superiors and informal expressions with friends; and also, they can vary depending on psycholinguistic context, or in other words, on whether learners have the chance to plan what they are going to say.[20] The causes of variability are a matter of great debate among SLA researchers.[21] Language transferMain article: Language transferOne important difference between first-language acquisition and second-language acquisition is that the process of second-language acquisition is influenced by languages that the learner already knows. This influence is known as language transfer.[22] Language transfer is a complex phenomenon resulting from interacti on between learners’ prior linguistic knowledge, the target-language input they encounter, and their cognitive processes.[23]Language transfer is not always from the learner’s native language; it can also be from a second language, or a third.[23] Neither is it limited to any particular domain of language; languagetransfer can occur in grammar, pronunciation, vocabulary, discourse, and reading.[24]One situation in which language transfer often occurs is when learners sense a similarity between a feature of a language that they already know and a corresponding feature of the interlanguage they have developed. If this happens, the acquisition of more complicated language forms may be delayed in favor of simpler language forms that resemble those of the language the learner is familiar with.[23] Learners may also decline to use some language forms at all if they are perceived as being too distant from their first language.[23]Language transfer has been the subject of several studies, and many aspects of it remain unexplained.[23] Various hypotheses have been proposed to explain language transfer, but there is no singlewidely-accepted explanation of why it occurs.[25]External factorsInput and interactionThe primary factor affecting language acquisition appears to be the input that the learner receives. Stephen Krashen took a very strong position on the importance of input, asserting that comprehensible input is all that is necessary for second-language acquisition.[26][27] Krashen pointed tostudies showing that the length of time a person stays in a foreign country is closely linked with his level of language acquisition. Further evidence for input comes from studies on reading: large amounts of free voluntary reading have a significant positive effect on learners' vocabulary, grammar, and writing.[28][29] Input is also the mechanism by which people learn languages according to the universal grammar model.[30]The type of input may also be important. One tenet of Krashen's theory is that input should not be grammatically sequenced. He claims that such sequencing, as found in language classrooms where lessons involve practicing a "structure of the day", is not necessary, and may even be harmful.[31]While input is of vital importance, Krashen's assertion that only input matters in second-language acquisition has been contradicted by more recent research. For example, students enrolled in French-language immersion programs in Canada still produced non-native-like grammar when they spoke, even though they had years of meaning-focused lessons and their listening skills were statistically native-level.[32] Output appears to play an important role, and among other things, can help provide learners with feedback, make them concentrate on the form of what they are saying, and help them to automatize their language knowledge.[33]These processes have been codified in the theory of comprehensible output.[34]Researchers have also pointed to interaction in the second language as being important for acquisition. According to Long's interaction hypothesis the conditions for acquisition are especially good when interacting in the second language; specifically, conditions are good when a breakdown in communication occurs and learners must negotiate for meaning. The modifications to speech arising from interactions like this help make input more comprehensible, provide feedback to the learner, and push learners to modify their speech.[35]Social aspectsAlthough the dominant perspective in second-language research is a cognitive one, from the early days of the discipline researchers have also acknowledged that social aspects play an important role.[36] There have been many different approaches to sociolinguistic study ofsecond-language acquisition, and indeed, according to Rod Ellis, this plurality has meant that "sociolinguistic SLA is replete with a bewildering set of terms referring to the social aspects of L2 acquisition".[37] Common to each of these approaches, however, is a rejection of language as a purely psychological phenomenon; instead, sociolinguistic research views the social context in which language islearned as essential for a proper understanding of the acquis ition process.[38]Ellis identifies three types of social structure which can affect the acquisition of second languages: socialinguistic setting, specific social factors, and situational factors.[39] Socialinguistic setting refers to the role of the second language in society, such as whether it is spoken by a majority or a minority of the population, whether its use is widespread or restricted to a few functional roles, or whether the society is predominantly bilingual or monolingual.[40] Ellis also includes the distinction of whether the second language is learned in a natural or an educational setting.[41] Specific social factors that can affectsecond-language acquisition include age, gender, social class, and ethnic identity, with ethnic identity being the one that has received most research attention.[42] Situational factors are those which vary between each social interaction. For example, a learner may use more polite language when talking to someone of higher social status, but more informal language when talking with friends.[43]There have been several models developed to explain social effects on language acquisition. Schumann's acculturation model proposes that learners' rate of development and ultimate level of language achievement is a function of the "social distance" and the "psychological distance"between learners and the second-language community. In Schumann's model the social factors are most important, but the degree to which learners are comfortable with learning the second language also plays a role.[44] Another sociolinguistic model is Gardner's socio-educational model, which was designed to explain classroom language acquisition.[45] The inter-group model proposes "ethnolinguistic vitality" as a key construct for second-language acquisition.[46]Language socialization is an approach with the premise that "linguistic and cultural knowledge are constructed through each other",[47] and saw increased attention after the year 2000.[48] Finally, Norton's theory of social identity is an attempt to codify the relationship between power, identity, and language acquisition.[49]Internal factorsInternal factors affecting second-language acquisition are those which stem from the learner's own mind. Attempts to account for the internal mechanisms of second-language acquisition can be divided into three general strands: cognitive, sociocultural, and linguistic. These explanations are not all compatible, and often differ significantly. Cognitive approachesMuch modern research in second-language acquisition has taken a cognitive approach.[50] Cognitive research is concerned with the mental processes involved in language acquisition, and how they can explain the nature of learners' language knowledge. This area of research is based in the more general area of cognitive science, and uses many concepts and models used in more general cognitive theories of learning. As such, cognitive theories view second-language acquisition as a special case of more general learning mechanisms in the brain. This puts them in direct contrast with linguistic theories, which posit that language acquisition uses a unique process different from other types of learning.[51][52]The dominant model in cognitive approaches to second-language acquisition, and indeed in all second-language acquisition research, is the computational model.[52] The computational model involves three stages. In the first stage, learners retain certain features of the language input in short-term memory. (This retained input is known as intake.) Then, learners convert some of this intake into second-language knowledge, which is stored in long-term memory. Finally, learners use thissecond-language knowledge to produce spoken output.[53] Cognitive theories attempt to codify both the nature of the mental representations of intake and language knowledge, and the mental processes which underlie these stages.In the early days of second-language acquisition research interlanguage was seen as the basic representation of second-language knowledge; however, more recent research has taken a number of different approaches in characterizing the mental representation of language knowledge.[54] There are theories that hypothesize that learner language is inherently variable,[55] and there is the functionalist perspective that sees acquisition of language as intimately tied to the function it provides.[56] Some researchers make the distinction between implicit and explicit language knowledge, and some between declarative and procedural language knowledge.[57] There have also been approaches that argue for a dual-mode system in which some language knowledge is stored as rules, and other language knowledge as items.[58]The mental processes that underlie second-language acquisition can be broken down into micro-processes and macro-processes. Micro-processes include attention;[59] working memory;[60] integration and restructuring, the process by which learners change their interlanguage systems;[61] and monitoring, the conscious attending of learners to their own language output.[62] Macro-processes include the distinction between intentional learning and incidental learning; and also the distinction between explicit and implicit learning.[63] Some of the notable cognitive theories of second-language acquisition include the nativization model, themultidimensional model and processability theory, emergentist models, the competition model, and skill-acquisition theories.[64]Other cognitive approaches have looked at learners' speech production, particularly learners' speech planning and communication strategies. Speech planning can have an effect on learners' spoken output, and research in this area has focused on how planning affects three aspects of speech: complexity, accuracy, and fluency. Of these three, planning effects on fluency has had the most research attention.[65] Communication strategies are conscious strategies that learners employ to get around any instances of communication breakdown they may experience. Their effect on second-language acquisition is unclear, with some researchers claiming they help it, and others claiming the opposite.[66] Sociocultural approachesWhile still essentially being based in the cognitive tradition, sociocultural theory has a fundamentally different set of assumptions to approaches to second-language acquisition based on the computational model.[67] Furthermore, although it is closely affiliated with other social approaches, it is a theory of mind and not of general social explanations of language acquisition. According to Ellis, "It is important to recognize ... that this paradigm, despite the label 'sociocultural' does not seek to explain how learners acquire the cultural values of the L2 but rather how knowledge ofan L2 is internalized through experiences of a sociocultural nature."[67] The origins of sociocultural theory lie in the work of Lev Vygotsky, a Russian psychologist.[68]Linguistic approachesLinguistic approaches to explaining second-language acquisition spring from the wider study of linguistics. They differ from cognitive approaches and sociocultural approaches in that they consider language knowledge to be unique and distinct from any other type of knowledge.[51][52] The linguistic research tradition in second-language acquisition has developed in relative isolation from the cognitive and sociocultural research traditions, and as of 2010 the influence from the wider field of linguistics was still strong.[50] Two main strands of research can be identified in the linguistic tradition: approaches informed by universal grammar, and typological approaches.[69]Typological universals are principles that hold for all the world's languages. They are found empirically, by surveying different languages and deducing which aspects of them could be universal; these aspects are then checked against other languages to verify the findings. The interlanguages of second-language learners have been shown to obey typological universals, and some researchers have suggested that typological universals may constrain interlanguage development.[70]The theory of universal grammar was proposed by Noam Chomsky in the 1950s, and has enjoyed considerable popularity in the field of linguistics. It is a narrowly-focused theory that only concentrates on describing the linguistic competence of an individual, as opposed to mechanisms of learning. It consists of a set of principles, which are universal and constant, and a set of parameters, which can be set differently for different languages.[71] The "universals" in universal grammar differ from typological universals in that they are a mental construct derived by researchers, whereas typological universals are readily verifiable by data from world languages.[70] It is widely accepted among researchers in the universal grammar framework that all first-language learners have access to universal grammar; this is not the case for second-language learners, however, and much research in the context of second-language acquisition has focused on what level of access learners may have.[71] Individual variationMain article: Individual variation in second-language acquisitionThere is considerable variation in the rate at which people learn second languages, and in the language level that they ultimately reach. Some learners learn quickly and reach a near-native level of competence, but others learn slowly and get stuck at relatively early stages of acquisition, despite living in the country where the language is spoken for severalyears. The reason for this disparity was first addressed with the study of language learning aptitude in the 1950s, and later with the good language learner studies in the 1970s. More recently research has focused on a number of different factors that affect individuals' language learning, in particular strategy use, social and societal influences, personality, motivation, and anxiety. The relationship between age and the ability to learn languages has also been a subject of long-standing debate.。

克拉申第二语言习得理论引论

克拉申第二语言习得理论引论在过去的三十几年中,为更好地理解人们的语言学习行为,应用语言学家提出了很多语言习得理论,并从心理学、社会学、语言学和教育学的角度对语言习得作出详细阐述。

其中影响最深的是美国应用语言学家克拉申(Stephan D. Krashen)提出的第二语言认知理论。

本文对克拉申的语言习得理论进行介绍和讨论。

一、克拉申的第二语言习得理论从传统意义上讲,第二语言习得分为两大流派:行为主义学说( behaviorism) 和固有观念学说(innatism) 。

前者认为学习者与其周围环境的交流导致语言习得的产生;后者强调人的内在的和先天的因素在语言学习中的重要性,认为人与生俱来具备一种语言机制( language acquisition de2vice) ,使得人们去自由地习得语言。

从20 世纪70年代起,克拉申便专注于第二语言习得的研究,经过多年的研究,于80 年代初发表其两大专著:《第二语言习得和第二语言学习》( Second LanguageAcquisition Second Language Learning) (1981) 和《第二语言习得的原则和实践》(Principles and Practicein Second Language Acquisition) (1982) ;同时于1982年与特雷尔(T. Terrell) 合作出版了《自然途径》(The Natural Approach) 一书。

在这三部著作中,克拉申通过对第二语言习得过程的分析,系统地阐述了他的语言习得理论。

克拉申的第二语言习得理论由以下五个假设组成: ①习得- 学得差异假设(acquisition2learninghypothesis) ; ②监检假设(monitor hypothesis) ; ③自然顺序假设(natural order hypothesis) ; ④输入假设(input hypothesis) ; ⑤情感过滤假设(affective2filterhypothesis) [1 ] 。

第二语言习得理论

第二语言习得理论

1. 语言得理论

1.1. 自然得理论

自然得理论认为,第二语言的得过程类似于儿童研究母语的过程。

它强调通过暴露于自然语言环境中,通过交流和接受反馈来培养语言能力。

这种理论强调语言输入的重要性,主张通过与母语者的互动来获得正确的语言输入。

1.2. 社会文化理论

社会文化理论认为,语言得是社会文化环境中的交互作用的结果。

它强调了社会互动对于语言得的重要性,尤其是与社区成员之间的参与和合作。

这种理论认为,语言得需要通过参与实际的交流和语言应用来获得。

2. 心理得理论

2.1. 认知心理理论

认知心理理论认为,语言得是一个复杂的认知过程。

它关注个体内部的认知机制和处理过程,如记忆、注意力、推理等。

这种理论认为,通过对语言结构的理解和分析,个体可以逐渐掌握第二语言。

2.2. 社会认知理论

社会认知理论强调认知的社会性。

它认为语言得不仅仅是个体内部的认知过程,还需要通过观察和模仿他人的语言行为来研究。

这种理论认为,社会互动和社会认知对于语言得至关重要。

以上是一些常见的第二语言习得理论。

每个理论都有其独特的观点和解释,可以根据具体情况选择合适的理论进行教学和学习的设计。

第二语言习得理论

填空判断20分1.第二语言习得研究的交叉学科:语言学、心理学、心理语言学。

2.第二语言习得研究的发端:Corder在1967年发表的《学习者偏误的意义》和Selinker在1972年发表的《中介语》。

3.1984年,鲁健骥在《中介语理论与外国人学习汉语的语音偏误分析》这篇文章中,将第二语言学习者的语言“偏误”和“中介语”的概念引入对外汉语教学领域。

4.1945年,弗里斯在《作为外语的英语教学与学习》一书中提出了对比分析的思想。

5.1957年,拉多在《跨文化语言学》中系统地阐述了对比分析的内容、理论依据和分析方法。

6.对比分析这一基本假设建立在行为主义心理学和结构主义语言学基础之上。

7.Selinker被称为“中介语之父”。

8.在第二语言习得顺序中,主要存在以下争议:①母语迁移;②“正确顺序”是否等于“习得顺序”;③第一语言习得顺序是否等于第二语言习得顺序。

9.输入假说是克拉申的语言监控模式整个习得理论的核心部分。

10.克拉申的输入假说包括四个要素:输入数量、输入质量、输入方式、输入条件。

11.情感过滤假说把成功的二语习得相关联的情感因素分为三大类:动机、自信、焦虑。

12.“社会文化理论”由前苏联心理学家维果茨基创立。

主要内容包括:调节论、最近发展区理论、个体话语和内在言语、活动理论。

13.原则和参数是普遍语法的核心概念。

14.最早提出“关键期假说”这个观点的是著名神经外科医生Penfield。

15.根据社会心理学家的观点,学习者的态度是有三个方面构成:认知、情感、意动。

16.(判断)第二语言习得中的语言焦虑是一种现实焦虑,也是一种状态焦虑。

所谓现实焦虑是指处于该现实情况下,任何人都会自然产生的焦虑;而状态焦虑是焦虑的暂时被动状态,它随着自主神经系统的唤醒,表现出对当时情境的忧虑和担心。

17.(判断)失误指口误、笔误等语言运用上偶然的错误,如不小心把“小张”说成了“小王”,是偶然发生的,和语言能力无关。

第二语言习得主要理论和假说

第二语言习得主要理论和假说一、对比分析假说(行为主义:刺激—反应—强化形成习惯)代表:拉多定义:第一语言习惯迁移问题。

两种语言结构特征相同之处产生正迁移,两种语言的差异导致负迁移。

负迁移造成第二语言习得的困难和学生的错误。

主张:第二语言习得的主要障碍来自第一语言的干扰,需要通过对比两种语言结构的异同来预测第二语言习得的难点和错误,以便在教学中采用强化手段突出重点和难点,克服母语的干扰并建立新的习惯。

影响:积极:听说法和是视听法,特别是句型替换练习的理论基础。

消极:根本缺陷——否认学习者的认知过程,忽视人的能动性和创造力。

二、中介语假说代表:塞林克基础:普遍语法理论和先天论的母语习得理论定义:中介语是指在第二语言习得过程中,学习者通过一定的学习策略,在目的语输入的基础上所形成的介于第一语言和目的语之间、随着学习进展向目的语逐渐过渡的动态的语言系统。

特点:1.中介语在其发展的任何一个阶段都是介于第一语言和目的语之间的独特的语言系统。

2.中介语是一个不断变化的动态语言系统3.中介语是由于学习者对目的语规律尚未完全掌握,所做的不全面的归纳与推论。

4.中介语的偏误有反复性5.中介语的偏误有顽固性。

在语音上易产生“僵化”或“化石化”现象。

意义:是探索第二语言习得者在习得过程中的语言系统和习得规律的假说。

把第二语言获得看做是一个逐渐积累完善的连续的过程,而且看做是学习者不断通过假设—验证主动发现规律、调整修订所获得的规律,对原有知识结构进行重组并逐渐创建目的语系统的过程。

三、内在大纲和习得顺序假说代表:科德《学习者言语错误的重要意义》反映内在大纲偏误定义:第二语言学习者在语言习得过程中有其自己的内在大纲,而学习者的种种偏误正是这种内在大纲的反映。

第二语言习得是按其内在大纲所规定的程序对输入的信息进行处理。

内在大纲实际上是人类掌握语言的客观的、普遍的规律,学习者不是被动地服从教师的教学安排、接受所教的语言知识,而是有其自身的规律和顺序。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

第二语言习得概念题汇总第一章第二语言习得理论简介 (3)一、概念及术语 (3)二、有关第一语言获得的研究 (4)三、有关二语习得的研究 (5)四、学习动机 (6)五、学习策略 (6)第二章行为主义心理学术语解析 (8)●思维: (8)●记忆: (8)●刺激stimulus: (9)●反应response: (9)●替代刺激substitute stimulus: (9)●积累效应summation effect: (10)●消退extinguished: (10)●迁移transfer/differential responses: (11)●废除disuse: (11)●语言习惯language habits: (11)●动觉kinaesthesis/动觉刺激kinaesthetic stimuli: (12)认知心理学术语解析 (13)一、知觉篇 (13)●注意(attention):●意识(consciousness)二、记忆篇 (13)●背景(context)●长时贮存(long-term storage)/●短时贮存(short-term storage)●衰退(decay)三、认知加工篇 (14)●概念驱动加工/自上而下加工(conceptually driven processes;top-down processes)●材料驱动加工/自下而上加工(data-driven processes;bottom-up processes)●控制加工(control processes)●自动加工(automatic process)●特征分析(features analysis)●信息加工取向(information-processing approach)●联结主义取向(connectionist approach)四、知识篇 (14)五、语言篇 (15)●大脑两半球(cerebral hemispheres)●移位(displacement)第一章第二语言习得理论简介一、概念及术语1.第一语言first language/母语mother tongue第一语言是指一个人幼年学会的第一种语言,并且这种语言会被用来进行社会交际。

母语是指一个人生下来后接触到的第一种或几种语言,但是这种(些)语言不一定会进入社会交际。

一般情况下,前者等同于后者,但也有极少数特殊情况:如生活在美洲的印第安人,其中有些人从小就离开了“保留地”,被养父母带走,或到外面去上学,他们中的不少人母语是印第安语的一种,但第一语言可能是英语、法语或西班牙语。

2.第二语言second language/目的语target language第二语言相对于第一语言,是指人生再次学会的一种或几种语言。

目的语是指人们有意识地学习的语言。

前者的外延比后者稍大,包含了自然学会和有意识的学习,而后者强调“有意识的学习”。

3.中介语inter language第二语言学习者所使用(掌握)的一种语言系统,或者是学习者某一时间的第二语言状态,它既不同于第一语言,也不同于第二语言。

影响中介语形成的因素:(1)规则的扩大化①母语的影响:母语语法规范的迁移。

②语言训练的影响:第二语言课堂上老师过分强调某一结构引起的规则迁移。

③第二语言内规则的扩大化。

例如英语中一般现在时使用动词原型,第三人称单数动词加“s”,一个英语第二语言习得者在写英语时常会犯错误,对单数第三人称后出现的动词使用原型。

(2)策略的影响④第二语言学习者学习策略的影响。

⑤第二语言学习者交际策略的影响。

4.习得acquisition指的是知识内在化的过程及其已经内在化的那部分知识。

是随着认知心理学的发展,从心理学的角度提出来的术语。

5.迁移transfer指的是人们已建立起的第一语言的“习惯”对学习新语言、建立新的语言习惯的过程产生的影响。

表现为中介语中所包含的第一语言的特点。

这个概念始于行为主义心理学指导下的语言学习理论。

依照行为主义的观点,人们相信,当第一/第二语言一致时,会产生积极的迁移——正迁移(positive transfer), 推动第二语言的掌握;反之,则形成负迁移(negative transfer)干扰第二语言的掌握。

6.化石化fossilization这一概念概括了第二语言学习中的一个普遍现象;学习者无论被纠正了多少次均会重复一个错误的形式直至语言水平达到相当高的程度。

7.语言习得的“关键期假设”(亦称作“自然成熟说”)这个理论认为,儿童的语言发展过程实际上是发音器官、大脑等制约语言的神经机制的自然成熟过程,随着儿童年龄的增长,这些机制逐渐成熟,这个过程大约是12岁以前完成,这个阶段最适合语言学习,过了这个阶段,学习语言就不那么容易了。

因而,这是学习语言的关键期(又称“临界期”)。

克里斯蒂娜(Krystyna)认为,2~7岁是语言学习的最佳时期,这个时期儿童是在下意识的条件下掌握语言的。

超过这个最佳时期,即便是年龄仍在关键期内,学习效果也不会那么好了。

二、有关第一语言获得的研究1.近现代对于人类语言能力来源问题的三种观点:①先天说ⅰ.早期先天论:17世纪,笛卡尔就认为,智力是与人类自身同时存在的一个实体。

ⅱ.语言习得机制:当代语言学家乔姆斯基认为,人类具有先天的获得语言能力的共同脑结构,他把这个机构称为“语言习得机制”(language acquisition device,简称LAD)。

外界刺激只是触发了这个机制。

人类的儿童能很快学会语言,而人类的近亲——黑猩猩却不能。

②后天论ⅰ.早期经验主义:约翰·洛克的“白板说”(tabularasa)。

ⅱ.20世纪初星期的行为主义心理学支持此观点。

其早期代表华声主张环境决定论。

例如狼孩脱离了人类社会,缺少语言环境的熏陶,不能掌握语言。

③先天后天兼而有之论人类语言既为先天遗传的因素,又有后天经验的作用,与此相关的是伦内伯格的“关键期假设”。

2.语言习得机制的生理基础:通过对失语症患者的治疗和关注,人们逐步发现语言的获得与发展是有相应的生理基础的。

失语症是脑血管疾病、脑外伤和脑肿瘤等大脑疾病的常见症状,由于大脑损伤,患者无法用语言正常表达自己的思想或理解他人的思想。

把失语症跟脑神经中枢的损伤相关联始于19世纪上半叶。

后来,在失语症研究中有两大发现奠定了神经语言学的基础。

①布罗卡失语症:布罗卡医生发现:大脑左半球额下回的后部(后来被命名为布罗卡区)受损的患者在语言方面的问题主要表现为表达障碍,而语言的理解能力相对正常。

②韦尼克失语症:患这种失语症的患者大脑左半球颞上回后部(后被命名为韦尼克区)受损,在语言方面的表现刚好跟布罗卡失语症相对,虽然听力正常但是无法理解语言,虽然能说话,但听不懂话,不论是别人说的还是自己说的。

后来人们还发现,除这两个区域外还有一些区域的受损会引起书写、阅读方面的障碍。

也还有人发现,尽管左脑主管语言中枢,但在一定条件下,右脑会起一定的代偿作用。

三、有关二语习得的研究1、第二语言习得过程与第一语言习得过程的差别:①神经生理学上:第一语言掌握过程伴随着大脑、听觉器官、言语器官的发育过程;而多数二语的获得不存在这些过程,他们在开始学习某种语言时已经具备上述生理条件。

一语和二语在大脑中的位置相同吗?一些研究者通过实验,验证了这样一个假设:早期双语者(在婴儿期或童年期,也就是12岁以前习得双语者)的语言处理在左脑进行。

与此相对,晚期双语者是用右脑处理第二语言的。

当然也有人做实验对这种假设提出质疑。

值得注意的是,也有的实验发现一语二语都可能用右脑处理。

②语言心理学上:第一语言掌握过程伴随着感知能力和认识能力的形成;而多数双语者在学习之前已具备了基本的感知能力、认识能力和抽象思维能力。

因此他们才能凭借第一语言的翻译来掌握二语的一些词语。

2、二语和一语的习得过程是有差别的,那么,二语能否达到一语的水平?我们应该为二语学习设定怎样的目标?又该用什么来衡量二语的水平?(1)二语能达到一语的水平吗?在这个问题上人们存在争议,既有人持否定态度(布隆菲尔德:No one is ever perfectly sure in a language afterwards acquired),也有人肯定这种可能性。

菲利克斯假设:人有两套认知系统,一套是语言学习系统,另一套是问题解决系统。

人在儿童期只存在一套认知系统,成年后才形成第二套。

成年人受环境因素影响倾向于(先使用)第二套,但这一套在语言学习中不如第一套有效。

两套认知系统存在竞争关系,语言教学应该设法通过策略引导成年人使用第一套,即语言学习系统。

(2)我们应该为二语学习设定怎样的目标?受主客观因素的影响,二语学习者达到与native speaker绝对相当的水平是很有困难的,所以二语学习者的目标应该是缩小学习目的和学习水平之间的差距,而第二语言教学应该重视的是如何帮助学习者达到某个相对实用的目的,而不是盲目追求标准。

(3)我们用什么来衡量二语的水平?海姆斯等人提出“交际能力”(Communicative Competence)作为衡量二语水平的标准。

交际能力有四个方面的要素:①历史(对一种语言及其社会历史文化的了解)②实践(明白使用场合)③有效(表达准确精炼)④语境(注意到这一点,前三个问题就能避免了)3、第一语言与第二语言的关系①观点一:第一语言会干扰二语学习。

这种认识是受行为主义理论影响形成的(见“迁移”词条)。

并且,在行为主义学习理论和结构主义语言理论的共同影响下,产生了“对比分析理论”,人们主张将学习者的第一语言和第二语言加以对比,两者相同或相近处将有助于二语学习,相异处则是二语学习的难点所在,需重点操练。

②观点二:一语和二语只有发展先后之分,而没有别的不同。

这种观点的理论基础是乔姆斯基的普遍语法(Universal Grammar)观。

乔姆斯基认为,语言,特别是第一语言不是学得的,而是婴儿天生具备人类共同语法规则和一套参数,婴儿根据其所处某种特殊语言的特点进行参数定值。

按其理论,学习二语就是一个参数再调整的过程。

4、影响二语习得的因素:(1)学习者个人因素:①年龄:A关键期假说(见相关词条)B一般来说,成年人在一定阶段内的语言水平提高速度比儿童快,因为他们有较强的语言交际驱动力。

②个性:外向者学习目的语水平上升较快,因为他们敢于在各种场合使用目的语,随着语言信息的输入不断增大,语言水平也就逐步提高。

③情绪:积极的情绪有利于语言学习。

④策略(后有专门部分讲解)(2)外部环境因素①语言环境:包括语言的上下文形成的语境,学习者对目的语的接触和使用条件,语言学习的社会背景等。

②学习气氛:这涉及到课堂教学营造的气氛和学习者个人的情绪。