Cours 2 - Institutions de la Ve République

活久见,看这些顶尖名校辣眼睛的专业!

活久见,看这些顶尖名校辣眼睛的专业!不要被外国大学的“大麻种植”专业吓到,也不要因为“爬树”、“香蕉的文化历史”、“行走的艺术”而大惊小怪。

它们就藏匿在顶尖知名学府的专业名录里,只是你还不知道而已。

哈佛大学Folklore and Mythology(民间传说与神话学)专业民间传说和神话学听着就很古老飘渺,这个专业的目的是通过语言和文化来研究现在的社会,分析出人文科学和社会科学中各种法则形成的原因。

对它感兴趣的学生必须要和教学主管或者相关的导师讨论为什么自己对这个研究方向感兴趣。

耶鲁大学LGBTS Studies(同性恋者/双性恋者/跨性别者研究)专业LGBT是在历史和现在的同性恋、双性恋、跨性别的经验和研究基础上授课的。

作为世界知名的老牌顶尖学府,耶鲁用行动阐释了无论是学术还是社会认同上的兼容并包。

而且随着社会对于多元化的认同,未必不会变成热门研究方向。

卡耐基梅隆大学Bagpipe Music(风笛学)专业CMU的音乐学院一直致力于培养优秀的、有天赋的音乐家,鼓励学生将想象力和创造力加入到音乐当中。

而且CMU是美国唯一有苏格兰风笛专业的学校,并且还有一支特别有名的风笛乐队。

音乐挚爱与名校录取兼得,还不心动吗?康奈尔大学Viticulture and Enology(葡萄栽培与葡萄酒酿制学)专业在纽约州葡萄酒区的核心地段、在世界顶级大学里学习种葡萄、酿造葡萄酒以及葡萄酒鉴赏,这是一件很浪漫有品的事情。

你一定知道那些世界著名的葡萄酒都卖到多贵一瓶了,所以这项听起来那么有情怀的专业同时也是有钱途的专业。

利物浦大学parapsychics(灵学)这就是最近在全球范围内突然盛起的热门专业:灵学。

主要学习捉鬼、驱邪等课程,这些曾经只能在电影、电视中才能看到的内容,如今却已经进入了高等院校的教室。

或许,不久之后,这些院校将成为培养“捉鬼敢死队”的最佳温床。

俄亥俄州立大学Turfgrass Management(草坪管理学)草坪管理学包括商业、私人和休息区域草坪的修理和商业管理。

法语专四语法复习词法一--冠词

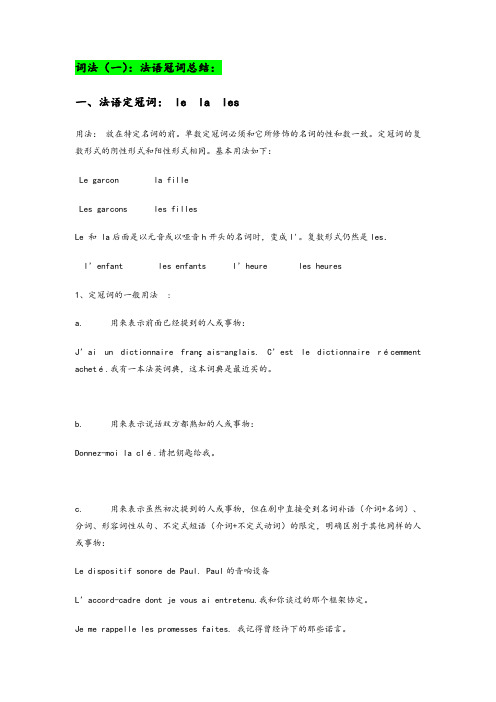

词法(一):法语冠词总结:一、法语定冠词: le la les用法:放在特定名词的前。

单数定冠词必须和它所修饰的名词的性和数一致。

定冠词的复数形式的阴性形式和阳性形式相同。

基本用法如下:Le garcon la filleLes garcons les fillesLe 和 la后面是以元音或以哑音h开头的名词时,变成l'。

复数形式仍然是les.l’enfant les enfants l’heure les he ures1、定冠词的一般用法:a. 用来表示前面已经提到的人或事物:J’ai un dictionnaire français-anglais. C’est le dictionnaire récemment acheté.我有一本法英词典,这本词典是最近买的。

b. 用来表示说话双方都熟知的人或事物:Donnez-moi la clé.请把钥匙给我。

c. 用来表示虽然初次提到的人或事物,但在剧中直接受到名词补语(介词+名词)、分词、形容词性从句、不定式短语(介词+不定式动词)的限定,明确区别于其他同样的人或事物:Le dispositif sonore de Paul. Paul的音响设备L’accord-cadre dont je vous ai entretenu.我和你谈过的那个框架协定。

Je me rappelle les promesses faites. 我记得曾经许下的那些诺言。

J’ai trouvé le moyen d’éviter cette faute de grammaire. 我找到了避免这个语法错误的办法。

d. 用来表示总体概念:Le cuivre est un métal. 铜是金属。

Le travail crée le monde 劳动创造世界。

具体名词指某一类人或事物时,定冠词和该名词可以用单数也可用复数:L’homme est mortel. Les hommes sont mortels. 人都要死的。

中国酒文化英文介绍Chinesewinecultureintroduction

Significance of Chinese Wine Culture in Global Context

• Cultural Exchange: Chinese wine culture has played a significant role in cultural exchange between China and other countries Wine has been a popular gift for foreign dignitaries and has facilitated cultural understanding and cooperation

Business Dinners: In business settings, driving Chinese wines is often seen as a way to strengthen relationships and seal deals It is important to follow the lead of the host or the most senior person at the table, and to toast them before drinking

Geographic Indications and Terroir of Chinese

Wines

要点一

要点二

Geographical Indications

Terroir

China has a rich history of producing wines with distinct regional characteristics Geographic indications (GIs) are used to identify wines that originate from specific regions known for their unique terroir and production methods

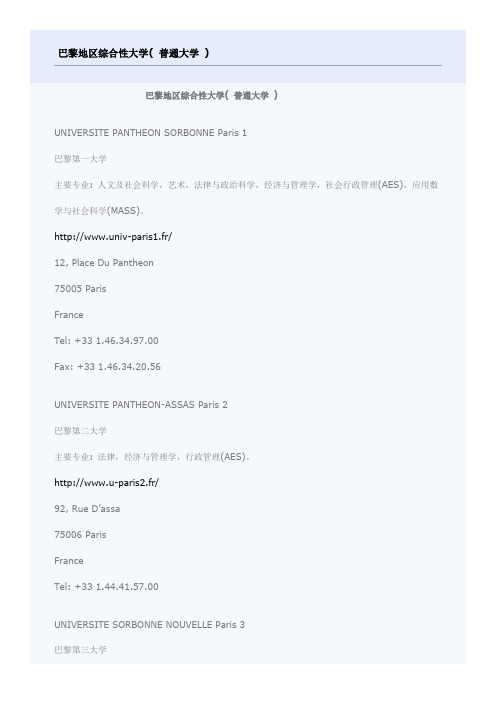

巴黎地区综合性大学名录 通讯录大全!Univ a paris

巴黎地区综合性大学( 普通大学)巴黎地区综合性大学( 普通大学)UNIVERSITE PANTHEON SORBONNE Paris 1巴黎第一大学主要专业: 人文及社会科学,艺术,法律与政治科学,经济与管理学,社会行政管理(AES),应用数学与社会科学(MASS)。

http://www.univ-paris1.fr/12, Place Du Pantheon75005 ParisFranceTel: +33 1.46.34.97.00Fax: +33 1.46.34.20.56UNIVERSITE PANTHEON-ASSAS Paris 2巴黎第二大学主要专业: 法律,经济与管理学,行政管理(AES)。

http://www.u-paris2.fr/92, Rue D’assa75006 ParisFranceTel: +33 1.44.41.57.00UNIVERSITE SORBONNE NOUVELLE Paris 3巴黎第三大学主要专业: 法文,外语,艺术。

http://www.univ-paris3.fr/13, Rue Santeuil75005 ParisFranceTel: +33 1.45.87.40.00Fax: +33 1.43.25.74.71UNIVERSITE PARIS-SORBONNE Paris 4巴黎第四大学主要专业: 法文,外语,人文及社会科学,艺术。

http://www.paris4.sorbonne.fr/1, Rue Victor Cousin75005 ParisFranceTel: +33 1.40.46.22.11Fax: +33 1.40.46.25.88UNIVERSITE RENE DESCARTES Paris 5巴黎第五大学主要专业: 理学院,体育,人文及社会科学,法律,经济与社会之行政管理,医学,牙医,药学。

http://www.univ-paris5.fr/12, Rue De L'ecole De Medecine75006 ParisFranceTel: +33 1.40.46.16.16Fax: +33 1.40.46.16.15UNIVERSITE PIERRE ET MARIE CURIE Paris 6巴黎第六大学主要专业: 理学院,医学,工程与技术科学。

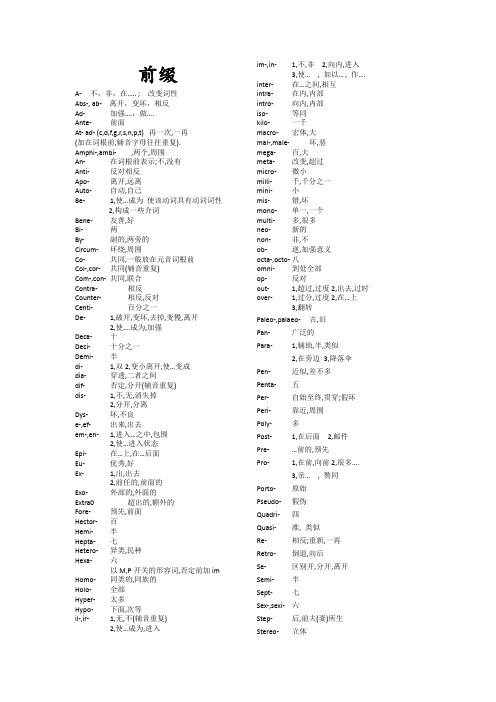

我整理的词根词缀

前缀A-不,非,在….. ; 改变词性Abs-, ab- 离开,变坏,相反Ad- 加强….,做….Ante- 前面At- ad- (c,d,f,g,r,s,n,p,t) 再一次,一再(加在词根前,辅音字母往往重复).Amphi-,ambi- ,两个,周围An- 在词根前表示;不,没有Anti- 反对相反Apo- 离开,远离Auto- 自动,自己Be- 1,使…成为使该动词具有动词词性2,构成一些介词Bene- 友善,好Bi- 两By- 副的,两旁的Circum- 环绕,周围Co- 共同,一般放在元音词根前Col-,cor- 共同(辅音重复)Com-,con- 共同,联合Contra- 相反Counter- 相反,反对Centi- 百分之一De- 1,破开,变坏,去掉,变慢,离开2,使….成为,加强Deca- 十Deci- 十分之一Demi- 半di- 1,双2,变小离开,使…变成dia- 穿透,二者之间dif- 否定,分开(辅音重复)dis- 1,不,无,消失掉2,分开,分离Dys- 坏,不良e-,ef- 出来,出去em-,en- 1,进入…之中,包围2,使…进入状态Epi- 在…上,在…后面Eu- 优秀,好Ex- 1,出,出去2,前任的,前面的Exo- 外部的,外面的Extra0 超出的,额外的Fore- 预先,前面Hector- 百Hemi- 半Hepta- 七Hetero- 异类,民种Hexa- 六以M,P开关的形容词,否定前加im Homo- 同类的,同族的Holo- 全部Hyper- 太多Hypo- 下面,次等il-,ir- 1,无,不(辅音重复)2,使…成为,进入im-,in- 1,不,非2,向内,进入3,使…, 加以… , 作…. inter- 在…之间,相互intra- 在内,内部intro- 向内,内部iso- 等同kilo- 一千macro- 宏体,大mal-,male- 坏,恶mega- 百,大meta- 改变,超过micro- 微小milli- 千,千分之一mini- 小mis- 错,坏mono- 单一,一个multi- 多,很多neo- 新的non- 非,不ob- 逆,加强意义octa-,octo- 八omni- 到处全部op- 反对out- 1,超过,过度2,出去,过时over- 1,过分,过度2,在…上3,翻转Paleo-,palaeo- 古,旧Pan- 广泛的Para- 1,辅助,半,类似2,在旁边3,降落伞Pen- 近似,差不多Penta- 五Per- 自始至终,贯穿;假坏Peri- 靠近,周围Poly- 多Post- 1,在后面2,邮件Pre- …前的,预先Pro- 1,在前,向前2,很多….3,亲…, 赞同Porto- 原始Pseudo- 假伪Quadri- 四Quasi- 准, 类似Re- 相反;重新,一再Retro- 倒退,向后Se- 区别开,分开,离开Semi- 半Sept- 七Sex-,sexi- 六Step- 后,前夫(妻)所生Stereo- 立体Sub- 1,副的,下面的,次一等的2,接近,靠近Suc(f,p,r)- 在…下面(辅音重复)Super- 1,超级,过度,超过2,在….上面Sur- 超过,在上面(辅音不重复) Supra- 超….Sus- 在…下面Sym-,syn- 相同,共同Tetra- 四Twi- 两Trans- 1,越过,横穿2,改变,变换Tri- 三Ultra- 1,极端,非常2,超出,超过Un- 1,无,不,没有2,雏形,打开,弄出Under- 1,在..下,在…之内2,不够,不足3,副Uni 单一,一个Vice- 副With- 向后,相反后缀-ability n. 能-able a. ….的,能….-ably ad. 能…地-aceous a. 具有…特征的-acious a. 有特征的-acity n. 有…倾向的-acle n. 物品,状态-acy n. 状态,性质-ad n. …东西,状态-ade n. 1,状态,物品2,个人或集体-age n. 状态,总称;场所物品;费用-ain n. ….人-aire n. …人-al a. …的n. 人,物,状态-ality n. 状态,性质-ally ad. …地(al+ly)-an n./a. ..地方,…人-ance,-ancy n. 性质,状况-aneity n. 性质,状态(源自aneous) -aneous a. …有…特征的-ant a. …的n. …人;…剂-ar a. …的n. …人,….物-ard n. 不好的人-arian n./a. …的-arium n. 地点,场所-ary a. …的n. 人,场所,物-ast n. …人,…物-astern. 不怎么样的人-ate v. 做,造成(使动)a. 具有下面的n. 人或地位-atic a. 有…性质的-ation n. 行为过程,结果-ative a. 有…倾向(性质)的-ator n. …人, …物-atory a. 有…性质的n. 场所,地点-cy n. 性质,状态-dom n. 状态或领域-ed a. 已…的, 有…的, …的(加在动词或名词后)-ee n. 被动的人-eer n. 专门人员-el n. 人或物-en v. 变成a. 由..制成的, 通常加于名词后n. 人或物-ence,-ency n. 性质,状态-enne n. 女性-ent a. 下面的n. …药剂;…人-eous a. 有…的-er n. …人;物品机器v. 反复做-ern a. …方向的n. …场所-ery a. …方向的n. …场所-ery n. 场所,地点;行为,情况-ese a. …的,加在国名,地名后-esque a. 如…的-ess n. 女性,雌性-et n. 小东西-etic a. 属于…的-ette n. 小的东西-ety n. 状态-eur n. 人-faction n. 达到的状态-fic a. 产生…的-fication n. (由fic变化而来)-fier n. 人或物-fold a./ad. 倍,双重-form a. 有…形状的-ful a. 有…的n. 满量-fy v. …化,成为…-hood n. 时期,性质-ia n. 某种病-ial a. 有…的-ian n. 某种人a. …国家的-ibility n. 具备…性质-ible a. 能…的-ic a. …的n. 人或学科;某种药-ical a. …的-ice n. 行为,状态-ician n. ….人,….家-ics n. 学术,学科-id a. 如..的n. 特征-ie n. 小东西,小动物或人-ier n. 人或物-ify v. 使物-ile a. 易于…的n. 物体-ine a. …的n. 人;状态;药物-ing n. 状态;物品;行业a. 令人…的-ion n. 表名词;某种物体,用品-ior a. 较…的-ious a. …的-ise v. …化(同-ize)n. 物品;状态-ish a. 像…一样.有的(放于具体名词后)v. 造成n. 某国语言-ism n. 各种主义,宗教;学术或学术派;行为现象,状态;疾病;具备某种性质-ist n. “表示信仰者”专家或从事人-istic a. …的(ist+c)-it n. 抽象名词;人-ite a. 有…的n. 人或物v. 促成-ition n. 行为过程,状态-itious a. …的-itive a. …的-itor n. 人-itude n. 性质,状态-ity n. 指具备某种性质-ive a. (-sive,-ative,-ive,-itive)n. 人或物-ivity n. 有…能力或特性(-ive+ity)-ization n. …化或发展过程(-ize+ation)-kin n. 小…-le v. 反复,拟声,(形到动)-less a. 无…的, 不…的-like a. 像…一样-ling a. 小东西或某种人-logy n. …学, …论, …法-ly a. 通常加在名词后Ad. 通常加在形容词后-mate n. 在一起的人-ment n. 行为或结果;具体事物-most a. 最….的-nik a. …迷,…者-ness n. 性质,状态,通常加于形容词后-o n. 人,物或状态;音乐术语-on n. 人物和一些物理学上的名词-oon n. 人或物-or n. 人或物-ory a. …的n. 场所-ose a. 多…的-osity n. 多…的状态-ot n. ….人-ous a. …的(通常放在一个完整单词后)-proof a. 防…的-ress n. 女性;物品(通常放于一个完整单词后)-ry n. 状态,性质;行业,学科;(不可数)集合名词,总称;场地-ship n. 某种关系或状态;某种技能-some a. 充满….的,具有…倾向的-ster n. ….人-th n. 通常指抽象名词-tic a. 与….相关的,….的(通常名词前)-ture n. 一般状态, 一般行为.(通常在单词或以t结尾的词根时使用)-ty n. 用于形容词后, 变为名词-ular a. 有…形状或性质的-ule n. 小…-um n. 地点名词尾缀-uous a. 多…的-ward a./ad. 向…Ward可变为wards 但只能作副词用-wise ad. 方向,状态-wise 可换成-ways-y a. 加在名词后变成形容词n. 在形容词或以r结尾的单词后“人或小东西”,常带有嬉谑性和爱称词根Acri, acrid,acid,acu 酸,锐利Act 行动,做Aero,aer,aeri 充气,空气Acro 高点, 顶点Ag 做Agon 挣扎,争夺Agr,agri,agro 田地,农业Alb 白色Ali,alter 其它的, 改变Ambul 行走Alt,alti 高Am,amor 情爱Archa(e) 古代的.Ample 大Ant,anti 古老Anim 生命,精神Ann,enn 一年Anthrop 人类Apt, ept 适应,能力Aqu 水Arbit 判断Arch, archy 统治者,统治,主要的Arm 武器Art 技巧,诡计,关节Arstro, aster 星,恒星Ard,ars 灼热Audit, audi 听Aug 增Auto 自己;自动Avar,av,avi 鸟,渴望Ball,bol 舞, 抛, 球Balm 香油Ban 禁止Bar 栏杆, 重压Bas,base 基础, 低下Bat 打击Bel,bell 战争,打斗Bibli 书Bio 生命,生物Blanc 白Brace 两臂Braid 扭Bridg,brev,brief 短,缩短Camp 田野Cand 白, 发光Capt,cap,cept,ceive,cup,cip 抓,拿,握住Cas,cad,cid 落下,降临Calor 热Cap,cipit 头Cant,chant 吟, 唱Carn 肉体, 果肉Cav 洞Cent,cant 唱歌Ceed,ced,cess 行走,前进Celer 快Cens 判断Cent 一百, 百分之一Center,centr 中心Cert,cern,cret 确定Char,car 可爱的Chart,card 纸片Chor 歌舞Chrom 颜色Chron 时间Cil 召集Cind 剪切Circ,cycle 圆,环Cis,cid 杀, 切开Cit 引用,引起Civ 文明Clam, claim 呼喊Clar,clair,clear 清楚Cliv,clin 倾斜,斜坡Clus,clos,clud 关闭Coct 煮,熟Cogn 知道Cord,card 心脏,一致Corpor,corp 身体,团体Cosm(o) 世界,宇宙Cred,creed 信任Cre,crease 增长,产生Cris,crit 判断,分辨Cru,crux,crus 十字形, 交叉Cryo 冻,冷Crypt 秘密,隐藏Cumb,cub 躺Cumber 障碍Curt 剪短Cult 培养,耕种Cur 关心Custom 习惯Cour,cours,cur,curs 跑, 发生Demn 伤害Dem(o) 人们,人民Dens 变浓厚Dent 牙齿Derm,dermat 皮肤,表皮Dexter 右边Di 日,日子Dicat,dict 说话,断言Dign 值得,高贵Doct,doc 教Dom 家,屋,统治Don,dit 给予,赠予Dorm 睡眠Dou,du,dub 二,又Draw 拉Drom 跑Dress 安排Duce,duc,duct 带来,引导Dur 持久,硬Dynam,dyn 力量Ed 吃Ego 自己,我Equi,equ 相等Err 犯错误,漫游Exempt,amp 使出,获得Extr 出去Erg,ert 活动,能量Esthet 感觉Ev 时代,年龄Fabl,fabal 说,讲Fabric 制作,编制Fac,fic 面,脸fac,Fect,fic, fact,fig 制作,做Fail,fall,fault 犯错误,欺骗Fer 拿来,带来Ferv 热,沸Fess 说Fid 信念,相信Fict,fig 虚构,制造Fil 线条Fin 范围,结束Firm 坚固Fix 固定Flam, flag 火焰,燃烧Flat 吹Flex,flect 弯曲Flict 打击Flor,flour 花Flu 流动Forc,fort 力量,强大Form 形状,形式Frag,fract 破碎,打破Frig 冷Front 前额Fug 离开,逃Fund,found 基础Fus 流,泻Gam 婚姻Gar 装饰,供应Gastr,gastro 胃Gen,genif 产生,出生Gen,germ,gener 种子,出生,种类Gest,gister 产生,带来Glaci 冰Gnor,gnos 知道Gon 角Grad 步,级Gram,graph 写Grat,gree 感激,高兴Gran 颗粒Grav, Griev 重,沉重,庄重Greg 群体Gress 行走,离去Habit 居住,习惯Hal 呼吸Hap 运气,机会Hav 拥有Head 头Hell(o) 太阳Helle(o) 螺旋Hes,her 粘附Hibit 拿住Hilar 高兴,欢乐Heir,hered,herit 继承Holy 神圣Hor 害怕,颤抖Hospit 客人Host 一大群, 一大堆,主人(男) Hum 地, 土Hypno 睡眠,催眠术的Hydro,hudr 水Icon,icono 偶像,图标’Idea,ideo 观点,思想Ident 相同Idio 个人的,特殊的Idol 偶像,形象Ign 火Imit,image 相像Insul 岛屿Integr 完整Ir,irr 生气It 行走Ject 投掷,抛掉Joc 笑话,玩笑Journ 日期Join,junct 连接,结合Jur,judg,judic 发誓,法律,评判Juven 年轻,少年Labor 劳动,吃苦Just 正直,正确Lact 奶,乳Langu 虚弱,倦Laps 滑走, 滑Lat 拿出,带出Later 边Lav,lut,luv 冲洗,洗Lax,leas 松弛Lect,lig 收集,选择Lect,leg 读, 讲Leg,legis 法律Let 小的东西Live,lev 变轻,举起Liber 自由Libr 书Lic 引诱Licen 允许Line 线条,直线Lingu 语言Liter 文字,字母Lith 石头Lim,limin 限制,门槛Linqu 离开Loc 地方Logu,log 说话Logy 学科,科学Long,leng 长Locu,loqu 说话Luc,lustr,lux,lumin 照亮,光Lud,lus 戏剧,玩Lun 月亮Magn,maj,max 大Macr,macro 宏观的Machin,mechan 机器Main,man 逗留,居住Mall 锤,槌Man,manu,mani 手,手工Mania 狂,癖Mar,mari 海Mark,marg 记号,符号Matr,meter 母亲,母性Med,medi,mid,meri 中间Meg,mega 大,百,万Meg(a),mega(o) 特大Memor,member,mnes,mnemon 记忆Mend 改错, 改正Ment 神智,思考Merch,mere 交易Mers,merg 没, 沉Metr, meter 计量,器件Mens,meas 测量,计量Med,medic,mideco 医疗,补救Micro 微观的Mini,min 小,缩小Minis 服务,管理Migr 迁移Milit 兵Min 突触,伸出Mir,mar 惊奇Mis(o) 厌恶Misc,med,ming 混淆,混合Mit,miss 送Mob,mov,mot 动乱, 动Mod,mo(u)ld 方式Mon,monit 警告Monstr 显示Mod 尺度Morph 形状Mort 死Mount 登上Mun 公共的Mur 墙Mus 娱乐Mut 改变Myst,myth 神秘Nat,nasc,nai 出生的Naut,nav 船Nect,nex 连接,关联Neg,ni 否认,不Negr,nigr 黑Neur 神经Neutr,neutro 中Nihil 不存在,无Noct 夜晚Nom(y) 某个领域的知识Nomin,nomen 名称,名誉Morm 规范,规则Not 知道Nost 家Nox,noc 伤害,毒害Null 没有Nunci,nounce,nuncil 说话Nutria,nurs,nour 营养Nov 新Number,numer,numero 数目Oner 负担Onym 名字Oper 工作Op(o),ops,opi 视,光Opt,apt 选择Optim 最好Ora,or 说,口Ot(o) 耳朵Orbit 圆圈Orig,ori 升起,开始Orn 装饰Ous 充满,大量Paci,peas 和平Pan 面包Pand,pans 扩大Par 平等,生产Parl 说话Part,port 部分,分开Pass 通过,感情Path 感情,痛苦Part(i),patr,pater 父,祖,祖国Pear,par 看见Ped,pod 脚,儿童,教育Pel,puls 驱动,推Pen,pun,pent 惩罚Pend,pens 悬挂,吊着Pens,pend,pond 称重,支付Peri 尝试Pet,pit,peat 寻求,追求Petr(o),petri 石头Phag 吃Phil 爱,爱好者Phobia,phob 厌恶,恐怕Phon 声音Photo 光Pict,pig 描画Pi 虔诚Physic,physio 自然,物理Pill,pil 柱Pire 呼吸Pisc 鱼Plac,plais 平静,安抚Plat 宽阔,扁平Ple,plet,ply 使满Plaud,plaus 鼓掌Plex, Ply,plic 重叠Plor 哭喊Pon,pose,pound,posit 放置Punct,point 变尖,尖Polis,polic,polit 城市,国家Popul,publ 人民,人们Poly 卖Port 运拿Posit,pos 放Post 后面Potent 有能力的Preci,prais,prin,priz 价值Pred,predat 掠夺,捕食Press 挤压Prim 主要的,第一Pris 抓住, 拿住Priv 单个, 私自Proach 接近Prol 后代, 子孙Prov,prob 测试,证明Propri,proper 拥有,引申为恰当的Pugn 打斗Punct,pung 戳,刺点Pur,purg 纯洁Put 思考,认为Quaint 知道Quest,quis,quir,quer 询问,探求Quies,quiet 静Quit 自由Quot 引用,数目Radic 根Rage 疯狂Range 排序,顺序Rapt,rap,rav 捕,夺Rad,ras 刮擦Rect 正直,正确Rid,ris 笑Rog 问,要求Ros,rod 咬Rot 轮子,转,旋转Reg,regi,regn 统治,规则Rig 硬,刚Riv 源自Rud 粗野,原始Rupt 断裂Rur,rus 农村Sacr,sanct,secr 神圣的Sali,salt 盐San,salub,salut 健康的Sangui 血Sag 知道Satis,sat,satur 足够,饱足,满足Save,salv,saf 求助,储存Scend,scent,scens 爬,攀登Sci 知道Script,scrib 写Sclera,sclera 硬,巩膜Scop 观察,镜Scrap 切,刮,割Scrut 检查Seal 密封Sen 老Sequ,secu 跟随Seg,sect 切割Sent,sens 感觉Sert 连接,加入Serv 保持,服务Set 安置好Sid 坐Sight 眼光Sign 信号,记号Simil,sembl,simul 一样,类似Seism,seismo, 地震Sino,sinic,sinico 中国Sinu 弯曲Sist 站立Soci,socio 同伴,社会Sol 单独,太阳Solu,solv 松开,解决Somn 睡眠Son 声音Soph 聪明,聪慧Sort 种类Speci 种类,外观Solid 坚实的Spic,spect,spec 看Spers,sper 希望,散开,点缀Spir 呼吸,精神Splend 光辉Spons,spond 承诺St,sta,stan,stat,stin 站,立Stall 放Stell 星星Still 小水滴Sti,stitut 建立,放Sting,stimul,stinct 刺,刺激Strict,strain,string 拉紧Struct 建立Styl 文体,风格,式样Sum 总数,概括Sumpt,sume 拿,取Sur 肯定Surg 升起Tach 钉子Tact,tig,tag,ting 接触Tail 剪,剪除Tain,tin,ten 拿住,保留Tard 慢Tect 盖上Tele 远Temn,tempt 蔑视Tempor,temper 时间或时间引起Tempt 尝试Tend,tens,tent 伸展Tenu, 薄,细Term,termin 界限Terr 土地,恐吓,怕Test 证据Text 编织The(o) 神Thesis 放置Therm 热Tim 害怕Tir 拉Toler 容忍Tomy,tom 切割Ton 声音Touch 摸,触摸Torn ,tour 转Tox 毒Tort,torque,tors 扭曲Tract 拖,拉,引Treat 处理Trem 颤抖Tribute 给予Trench 切割Trop 转Tru 相信,真实Trus,trud 推Turb 搅动Tutt,tut 保护Twine 编织Typ 模式,形状Umbr 影子Un,muni 单一,一个Und 溢出Ultimo,ult 最后Ur 尿Urb 城市Up 向上Us,util 用Vac,void,van,vacu 空Vagr,vag 漫游Vapor 蒸汽Vas,vad 逃走Val,vail 强壮Valu,val 价值Vade 走Vari,vary 变化Veil 盖上Vent 透风Vent,ven 来Venge 惩罚Ver 真实Verb 词语Vert,vers 转Vest 衣服Vestig 脚印Vey,voy,vi,via 道路,路径Vibr 摇摆Vil 卑劣的Vinc,vict 征服Vir 男人Vis,vis 分开,看Viv,vig,vit 生命,活力Vok,voc 声音,呼喊Volunt,vol 意愿,意志Volv,volt,volu 卷,转,滚Vor 吃Vot 发誓Vulg 人群Vuls,vult 撒开,收缩Ware 注视Zeal 热心Zoo 动物Wan 缺乏Wis,wit 懂得wal 隔挡物。

37所全法大学语言中心介绍

Université Paris 4 (75)

Université Paris 4

fssorbonne.fr/article.php3?id_article=565

3

Université de PARIS 12 CRTEIL (94)

Université de PARIS 12 CRTEIL

9

Caen (14)

Université de Caen

http://www.unicaen.fr/cefe/Site%20CEUIE%207/Menu.ht m

10

Rennes (35)

Université de RENNES

http://www.univ-rennes2.fr/cirefe/

11

Université de Bordeaux III

http://www.defle.u-bordeaux3.fr/

18

PAU (64)

Université de Pau et des PAYS de L'ADOUR

http://iefe.univ-pau.fr/live/

19

Pergignon (66)

Université de Rouen

http://www.univ-rouen.fr/

8

INSA Rouen (76)

Section Franais Langue Etrangère. Campus de Mont-Saint-Aignan

http://www.insarouen.fr/accueil?set_language=fr&cl=fr

25

Nice (06)

Université de NICE

MTI缩写词汇

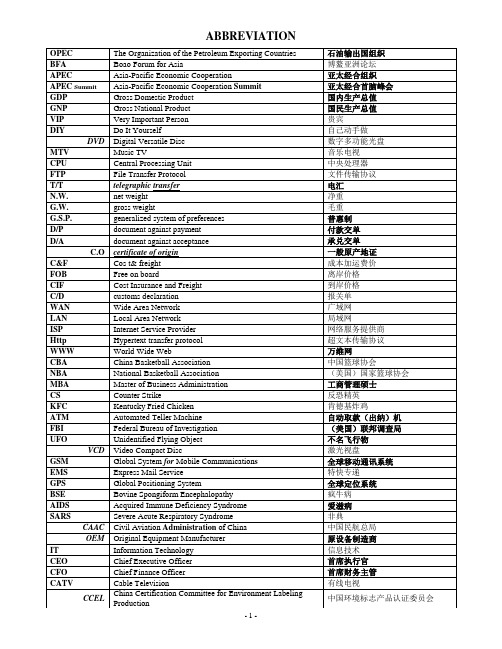

石油输出国组织 博鳌亚洲论坛 亚太经合组织 亚太经合首脑峰会 国内生产总值 国民生产总值 贵宾 自己动手做 数字多功能光盘 音乐电视 中央处理器 文件传输协议 电汇 净重 毛重 普惠制 付款交单 承兑交单 一般原产地证 成本加运费价 离岸价格 到岸价格 报关单 广域网 局域网 网络服务提供商 超文本传输协议 万维网 中国篮球协会 (美国)国家篮球协会 工商管理硕士 反恐精英 肯德基炸鸡 自动取款(出纳)机 (美国)联邦调查局 不名飞行物 激光视盘 全球移动通讯系统 特快专递 全球定位系统 疯牛病 爱滋病 非典 中国民航总局 原设备制造商 信息技术 首席执行官 首席财务主管 有线电视 中国环境标志产品认证委员会

ABBREVIATION

OPEC BFA APEC APEC Summit GDP GNP VIP DIY DVD MTV CPU FTP T/ T N.W. G.W. G.S.P. D/P D/A C.O C&F FOB CIF C/D WAN LAN ISP Http WWW CBA NBA MB A CS KFC ATM FB I UFO VCD GS M EMS GPS BSE AIDS SARS CAAC OEM IT CEO CFO CATV CCEL The Organization of the Petroleu m Exporting Countries Boao Foru m for Asia Asia-Pacific Econo mic Cooperation Asia-Pacific Econo mic Cooperation Summit Gross Domestic Product Gross National Product Very Impo rtant Person Do It You rself Dig ital Versatile Disc Music TV Central Processing Unit File Transfer Protocol telegraphic transfer net weight gross weight generalized system of preferences document against payment document against acceptance certificate of origin Cos t& freight Free on board Cost Insurance and Freight customs declaration Wide Area Network Local Area Network Internet Service Provider Hypertext transfer protocol World Wide Web China Basketball Association National Basketball Association Master of Business Administration Counter Strike Kentucky Fried Chicken Automated Teller Machine Federal Bureau of Investigation Unidentified Flying Object Video Co mpact Disc Global System for Mobile Co mmunication s Exp ress Mail Service Global Positioning System Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndro me Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Civil Aviation Administration of Ch ina Original Equip ment Manufacturer Information Technology Chief Executive Officer Chief Finance Officer Cable Telev ision China Cert ification Co mmittee for Env iron ment Labeling Production

瑞士日内瓦大学基本概况

瑞士日内瓦大学基本概况瑞士的日内瓦大学的始建于1559年,前身是约翰·加尔文建立的日内瓦学院,内瓦高级翻译学院是世界教学水平最高的学院,跟着一起来了解下瑞士日内瓦大学基本概况吧,欢迎阅读。

一、关于日内瓦大学About the UniversityFounded in 1559 by Jean Calvin, the University of Geneva (UNIGE) isdedicated to thinking, teaching, dialogue and research. With 16’500 students ofmore than 150 different nationalities, it is Switzerland’s second largestuniversity.UNIGE offers UNIGE offers more than 500 programmes (including 129Bachelor’s and Master’s degree programmes, 80 doctoral programmes) and more than300 continuing education programmes covering an extremely wide variety offields: exact sciences, medicine, humanities, social sciences, law, etc. Itsdomains of excellence in research include life sciences (molecular biology,bio-informatics), physics of elementary particles, and astrophysics. UNIGE isalso host and co-host to seven National Centres of Competence in Research:Frontiers in Genetics, MaNEP, PlanetS, SwissMap, Chemical Biology, SynapticBases of Mental Diseases and LIVES-Overcomingvulnerabilities in a life courseperspective.Just like the city of Geneva itself, the university enjoys a stronginternational reputation, both for the quality of its research (it ranks amongthe top institutions among the League of European Research Universities) and theexcellence of its education. This acclaim has been won in part due to its strongties to many national and international Geneva-based organizations, such as theWorld Health Organization, the International Telecommunications Union, theInternational Committee of the Red Cross, and the European Organization forNuclear Research.日内瓦大学(UNIGE)由加·加尔文(JeanCalvin)建立,始创于1559年,日内瓦大学在发展的过程中始终致力于思考、教学、对话、研究。

Policy Diff usion Seven Lessons for Scholars and Practitioners

Theory to PracticeCharles R. Shipan is J. Ira and NickiHarris Professor of Social Science at the University of Michigan. Previously, he taught at the University of Iowa and held research positions at the Brookings Institution, the University of Michigan’s School of Public Health, and Trinity College in Dublin. He is author of numerous articles, book chapters, and books about political institutions and public policy, including Deliberate Discretion? The Institutional Foundations of Bureaucratic Autonomy (with John D. Huber, Cambridge University Press, 2002).E-mail: cshipan@Craig Volden is professor of public policy and politics in the Frank Batten School of Leadership and Public Policy at the University of Virginia. His research focuses on legislative politics and interactionamong political institutions. He is currently exploring issues in American federalism and examining why some members of Congress are more effective lawmakers than others.E-mail: volden@788 Public Administration Review • November | December 2012Public Administration Review ,Vol. 72, Iss. 6, pp. 788–796. © 2012 by The American Society for Public Administration. DOI: 10.111/j.1540-6210.2012.02610.x.Donald P . Moynihan, Editor Charles R. Shipan University of Michigan Craig VoldenUniversity of VirginiaTh e scholarship on policy diff usion in political science and public administration is extensive. Th is article provides an introduction to that literature for scholars, students, and practitioners. It off ers seven lessons derived from that literature, built from numerous empiricalstudies and applied to contemporary policy debates. Based on these seven lessons, the authors off er guidance to policy makers and present opportunities for future research to students and scholars of policy diff usion.Over the past 50 years, scholars have publishednearly 1,000 research articles in political science and public administration journalsabout “policy diff usion.” Th is interest in how policies spread from one government to the next has been increasing among scholars and practitioners alike. Yet, although this focus has produced numerous insights into the policy-making process, the sheer volume of scholarship makes it diffi cult to identify and under-stand the key fi ndings and lessons. Indeed, it is hard to see the forest through all of these trees.1 In this article, we step back and draw seven lessons from the literature and its current direction. Our review has three main purposes: First, this article may serve as an introduction for readers who are largely unfamiliar with policy diff usion. Second, practitioners may better understand diff usion pressures and their impacts on policy choices by focusing on key lessons. And fi nally, scholars who are interested in policy adoption, inno-vation, and diff usion may fi nd new research directions in the takeaway points off ered here. Th us, our goal is to provide insights to both practitioners and scholars, knowing that this necessarily entails sacrifi cing some depth and specifi city in order to capture broad lessons of general interest.In its most generic form, policy diff usion is defi ned as one government’s policy choices being infl uenced by the choices of other governments. With this defi nition in hand, the importance of policy diff usion is undeni-able. Th ose who wish to understand why governments adopt particular policies would be hard-pressed to fi nd examples of policies that are selected entirelyfor internal reasons. Policy makers rely on examplesand insights from those who have experimented with policies in the past. Government offi cials worry about the impact that the policies of others will have on their own jurisdictions. Th e world is connected today as never before, and those connections structure the policy opportunities and constraints faced by policy makers at the local, regional, state, national, and international levels.In the American context, for example, health policy cannot be understood without assessing both the eff ects of state experiments on the formulation of national policies and the subsequent eff ects of thosenational policies on the states.2 Welfare reforms offer opportunities to learn from other governments’ earlier policies while trying to avoid becoming attractive to a needy population. Local and state governments compete for businesses with various tax incentives. Th e centralization of education policy in recentdecades, with more funding provided and regulatory controls exerted by state and national governments, has d ramatically altered local choices by superintend-ents and school boards. And the U.S. experience is not unique. External factors infl uence internal policy choices in every major policy area around the world. As just one example, pressure on European Union countries facing debt crises to adopt austerity meas-ures by other member governments illustrates how policy diff usion considerations do not stop at national borders.In today’s interconnected world, understanding policy diff usion is crucial to understanding policy a dvocacy and policy change more broadly. For instance, given that state governments may learn from locala ntismoking experiences, is an antismoking group better served by targeting its limited resources toward advocating change at the local level or at the state level (see, e.g., Shipan and Volden 2006)? And, given numerous policy diff usion pressures, can scholars be confi dent in their explanations of policy choices without adequately accounting for external infl uencesPolicy Diff usion: Seven Lessons for Scholars and PractitionersPolicy Diffusion: Seven Lessons for Scholars and Practitioners 7892011), and the rate at which innovations spread has accelerated (Boushey 2010). Whereas prior policy makers may have been limited to l earning only from the experiences of nearby neighbors, today’s sophisticated politicians and administrators have a much greater capacity to look far and wide for useful solutions to policy problems. Although these changes make detecting policy diff usion more difficult than merely exploring geographic clusters, they off er amazing opportunities for better policy choice and make the fi eld of policy diff usion studies more interesting and signifi cant than ever before.Lesson 2: Governments Compete with One Another Responding to claims that governments cannot be as effi cient or innovative as the free market, Charles Tiebout (1956) presented a model in which local governments compete with one another, o ffering policies that are attractive to residents who sort themselves into jurisdictions based on their preferences for taxes and spending. Th is work launched a massive scholarly research stream of its own and drew attention to the idea of competition across governments.In terms of policy diff usion, such competition aff ects the choices of other governments. A city that fi nds its middle-class residents moving to the suburbs for better schools may need to respond with education reforms of its own, or instead it may cater to other possible residents by focusing on altogether diff erent alterna-tives, such as attracting a professional sports team or improving public transportation. Th is example illustrates the breadth of the concept of policy diffusion. Not merely the study of whether the same policies spread across governments, policy diff usion broadly encompasses the interrelated decisions of governments, even when one government’s education policies infl uence another’s transportation or entertain-ment policies.While much of the economics literature that followed Tiebout focused on the wasteful nature of tax competition across states and localities (e.g., Wilson 1999), literatures in political science, public administration, and sociology turned to examples of public s pending, regulation, and the production of public and private goods. For example, Berry and Berry (1990) demonstrate competi-tion across state borders as one key determinant of state lottery adoption. Such competition is not merely reactive to the decisions of other states, but also can be strategic, anticipatory, and preemptive (e.g., Baybeck, Berry, and Siegel 2011).It is in the realm of “redistributive” policies that competition-based policy diff usion has generated some of the most heated policy exchanges. Here, scholars and practitioners have focused on the possibility of a “race to the bottom” in social programs such as welfare. As articulated by Peterson and Rom (1990) in the American c ontext, state policy makers worry about becoming “welfarem agnets,” to which potential recipients move in order to receive higher benefi ts. Such fears may lead state governments to undercut one another in their redistributive services, eventually racing toward undesirable social safety nets. Th e race-to-the-bottom concept fueled major policy discussions about the likely impacts of welfare (see, e.g., Berry 1994)? Th e following lessons begin to answer thenumerous questions that arise once scholars and practitioners turn their focus to policy diff usion.Lesson 1: Policy Diffusion Is Not (Merely)the Geographic Clustering of Similar PoliciesTh e spread of a policy innovation from one government to the next tends to bring to mind spatial imagery, such as ripples spreadingfrom a pebble dropped in a pond. Indeed, early work on policy dif-fusion emphasized this sort of eff ect, usually conceived of as regional clustering (e.g., Walker 1969). Th is classic view of policy diff usioncontinued into recent decades. Even when the methodologicalsophistication of event history analysis began to allow external andinternal determinants of policy choices to be examined simultane-ously (Berry and Berry 1990), diff usion forces were often measured merely by the number of geographically neighboring states that had already adopted the given policy. Presumably, if scholars controlfor the internal reasons for a policy adoption and fi nd evidencethat e arlier choices of neighbors still matter, then policy diff usion is relevant to understanding such adoptions.While off ering a good starting point, the classic view of policy dif-fusion as geographic clustering is often overly limiting, sometimesmisleading (or even wrong), and increasinglyoutdated. Th is view is overly limiting becausethere are many reasons why policy m akerslook beyond their own jurisdictions in mak-ing policy choices. Lessons about how to dealwith budget defi cits in California need not be drawn only from Oregon, Nevada, and Arizona. Detroit is not competing for business only with Cleveland and Ann Arbor, but alsowith T oronto, Shanghai, and Seoul. And, ascountries wrestle with how to downsize theirsocial programs, their quest for answers does not stop at nearbyb orders, but instead extends to larger regions or even worldwide (e.g., Brooks 2005; Weyland 2007).Moreover, even when geographic clustering may be theoreticallyimportant, appearances of such clustering may be misleading.Similar governments often face the same types of problems andopportunities at about the same times. Which states were likely toreinstate the death penalty after the U.S. Supreme Court rulings ofthe 1970s (Mooney and Lee 1999)? Which governments aroundthe world would adopt e-government and e-democracy practiceswhen the relevant technologies became available (Lee, Chang, andBerry 2011)? How would states develop and modify enterprisezones given federal incentives (Mossberger 2000)? Because similarstates tend to adopt similar policies, and because geographicallyn eighboring states tend to have many political, economic, and demographic similarities, evidence of geographic policy c lusteringmay have little to do with policy diff usion—that is, with onegovernment’s policy choices depending on others’ policies (Volden,Ting, and Carpenter 2008).In today’s world, with low barriers to communication and travel,the classic view of policy diff usion as geographic clustering isgrowing increasingly outdated. Over time, the lists of the mosti nnovative American states have changed (Boehmke and Skinner While off ering a good s tarting point, the classic view of policy diff usion as g eographicc lustering is often overly l imiting, sometimes m isleading (or even wrong),and i ncreasingly outdated.790 Public Administration Review • November | December 2012Given the political nature of policy choices, the multifacetedgoals of policy makers, and the complexity of policies themselves, learning-based policy diff usion may be limited in a variety of ways. Weyland (2007), for example, demonstrates how national policy makers throughout Latin America were infl uenced by a series of biases and heuristics in developing their pension reform processes rather than making rational assessments based on all available information. Moynihan (2008) shows how policy makers rely on their networks to learn under uncertainty and during times of crisis. Learning about others’ policies and then eff ectively using lessons learned to solve one’s own policy problems is time intensive and takes a high degree of skill. Time-pressed policy makers, those with limited staff support, and those generalists who have not had the opportunity to gain specialized expertise will not be able to take full advantage of others’ policy experiences.Limits on the capacity to learn from others can be overcome, at least partially, by technological advances and by go-between actors. Low-cost communication and travel allow today’s policy m akers to attend conferences to exchange ideas, to venture forth on f act-fi nding trips, and to exchange information widely while sitting at their own desks. Interstate professional organizations such as the National Conference of State Legislatures or the National Governors Association off er clearinghouses of informa-tion about the policies adopted by other governments (e.g., Balla 2001). Similar organizations exist at other levels of government and around the world. Füglister (2012), for example, shows that membership in intergovernmental health policy conferences in Switzerland increases the likelihood that a canton will learn about and then adopt successful policies found in other cantons. Informal personal networks also help with the search for appropriate policies (e.g., Binz-Scharf, Lazer, and Mergel 2012). Additionally, policy advocates and entrepreneurs can step in to inform policy makers about policies that they believe would be attractive and eff ective in a new jurisdiction (e.g., Haas 1992; Mintrom 1997). However, although these groups and individuals may help overcome lim-its to learning, they also bring with them their own biases and limitations.Lesson 4: Policy Diffusion Is Not Always Benefi cial Competition across governments may help remove ineffi ciencies, eliminate waste, match services to residents’ desires, or hold down taxes, mimicking market incentives. Learning among governments can produce experimentation and more eff ective policy choices. Yet competition may also produce a race to the bottom in certain redistributive programs, and the wrong lessons can often be drawn from others’ experiences (e.g., Sharman 2010; Soule 1999).3 Th erefore, while it is important to recognize the favorable aspects of policy diff usion, it would be wrong to declare inter-related policy decisions across governments always benefi cial.Scholars have identifi ed four main mechanisms of policy diff usion: competition and learning, as discussed earlier, but also imitation and coercion (e.g., Shipan and Volden 2008). Imitation is thecopying of another government’s policies without concern for those policies’ eff ects; thus, the extent of learning in these circumstances devolution in the mid-1990s and generated sizable scholarly litera-tures about why and where poor people move (e.g., Bailey 2005) and about the incentives of state policy makers (e.g., Volden 1997).Although competition across states, localities, and countries exists in a wide range of policy areas, from taxes to welfare to trade, its importance for policy choices should not be overstated. For instance, the evidence that potential welfare recipients move across state lines for greater welfare benefi ts is mixed at best. For many other policy areas, ranging from county foster care policies, to state regulations on youth access to tobacco, to national disease control policies, governments have little or nothing to gain from competi-tion. In many cases, governments set aside competition altogether, solving their problems collectively through interstate compacts or multilateral trade agreements. And more pernicious forms of com-petition across states have been explicitly disallowed; for example, the commerce clause of the U.S. Constitution keeps states from engaging in their own trade wars against one another.Lesson 3: Governments Learn from Each OtherIn his famous dissenting opinion in the case New State Ice Co. v Liebmann, U.S. Supreme Court Justice Louis D. Brandeis wrote, “It is one of the happy incidents of the federal system that a single courageous State may, if its citizens choose, serve as a laboratory; and try novel social and economic experiments without risk to the rest of the country” (285 U.S. 262 [1932], 311). In order for governments to fully serve their roles as laboratories of democracy, policy makers must act as scientists, watching these experiments and learning from them. Indeed, the policy diff usion literature has recently provided substantial evidence of governments learning from one another’s experiences.Meseguer (2006), for example, fi nds that countries learn from the eff ectiveness of others’ trade liberalization policies and s tructure their own policies as a result. Volden (2006) shows that theAmerican states that were best able to reduce their uninsured rates among poor children were most likely to have their children’s health insurance programs copied by other states. Gilardi, Füglister, and Luyet (2009) establish that countries are more likely to change their hospital fi nancing policies when they are ineff ective and that these governments tend to adopt policies found to be eff ective elsewhere.Such learning takes us far afi eld from the geographic clustering ofpolicies. Th e best and most relevant experiments may be acrossthe country or halfway around the world.Moreover, what is learned may have moreto do with political opportunity than withpolicy eff ectiveness. Policies are complex,and the goals of policy makers vary from onegovernment to the next. Success in contain-ing costs may be more attractive to some than success in improving health outcomes, for example. Electorally minded politicians maycare about the political success achieved ratherthan the policy s uccess (Gilardi 2010), may look for political coverwhen adopting unpopular policies such as tax increases (Berry andBerry 1992), or may seek to learn not only about better policies but also about how better to compete with other governments (Guler,Guillén, and Macpherson 2002).While it is important tor ecognize the favorable aspects of policy diff usion, it would be wrong to declare i nterrelated policy decisions acrossg overnments always benefi cial.Policy Diffusion: Seven Lessons for Scholars and Practitioners 791policies might have on statewide antismoking policies. On onehand, there could be a “snowball eff ect,” whereby the momentum from the adoption of more local antismoking restrictions leads to a greater likelihood of state adoption. On the other hand, there could be a “pressure valve eff ect,” whereby the adoption of a ntismoking restrictions in all of the localities that really want them takes p ressure off the state government to act.Given that both of these eff ects seem plausible, we set out to learn which eff ect occurs and, if both do, which political features within a state might produce one eff ect instead of the other. We found that both of these eff ects do indeed take place, but which eff ect predomi-nated was determined by interest group politics and by the capacity of the state legislature. For example, in states with an active and strong health lobby in the state legislature, local adoptions positively infl uenced the likelihood of state adoptions, as these lobbyists could point to favorable local experiences. States without strong health lobbyists were not only less likely to adopt antismoking restrictions overall, but even less likely still to do so if localities had already adopted a number of restrictions.In terms of capacity, about a dozen states do not pay their legislators any annual salary at all, beyond covering per diem expenses; some legislatures do not meet for more than a few months every year or two; and many do not hire extensive legislative staff s. Such circum-stances profoundly infl uence policy diff usion processes. Because of their lower capacity, these “less professional” state legislatures exhibit a strong pressure valve eff ect. If the localities adopted antismoking restrictions, that action removed the problem from the state policy agenda. Legislators could move on to more pressing business or return home to their primary jobs. In contrast, the most p rofessional (and higher-capacity) states exhibited the strongest snowball eff ect, with state legislators clamoring to take local policies, extend them statewide, and use their policy achievements as grounds to advance their political careers.5In a follow-up study (Shipan and Volden 2008), we assessed which diff usion mechanisms led localities to adopt these a ntismoking restrictions in the fi rst place and discover that policy-makingc apacity once again had a signifi cant impact. Larger cities learned greatly from earlier localities’ experiences and resisted preemptive pressures from their state government. In contrast, policy makers in smaller communities were less likely to learn and more likely to be b uff eted by state policy-making decisions. Such small towns were also more susceptible to competition, fearful of losing diners to nearby n eighbors if they adopted restaurant restrictions, and they were more likely to imitate the policies of larger cities, even those policies were inappro-priate for their own communities.Th ese two studies refl ect a larger literature on the conditional nature of policy diff usion.Th e particular networks in which govern-ments are embedded infl uence their oppor-tunities for learning. Recent experiences and present policies aff ectpolicy diff usion. Stone (1999), for example, argues that govern-ments facing an economic crisis or experiencing a recent military defeat are more susceptible to coercion. Bailey and Rom (2004) show that initially generous governments are more responsive tois merely the acknowledgment that a government that is perceived to be a leader has the policy and that it must, therefore, be some-thing desirable. Imitation may be thought of as the policy diff usion equivalent of “keeping up with the Joneses,” with of all the associ-ated negative aspects of such an approach. Th e voting public may demand the adoption of policies that they have seen or experienced elsewhere, regardless of whether those policies are ultimately s uitable in their home community (e.g., Pacheco 2012). Cities where profes-sional sports teams would not thrive seek them out nonetheless. State legislatures exactly copy bills written in other states, typos and all. Countries without the proper economic and educational foundations overbuild their infrastructure and industrial parks in the hope that doing so will attract businesses. Sometimes this spread of untested ideas works, but often, it results in inappropriate and understudied policy choices.Coercion is the use of force, threats, or incentives by one govern-ment to aff ect the policy decisions of another. An extreme example is armed confl ict, a concern that has generated its own sizable d iff usion literature (e.g., Most and Starr 1980). But coercion need not rely on the threat of military confl ict. Instead, economic power can pro-vide the foundation for coercion, as seen in the recent attempt by Germany to bring about austerity measures in Greece. Th e example of International Monetary Fund incentives leading developing coun-tries to adopt certain liberalization practices shows how international organizations can be used to facilitate policy diff usion. Coercion can also be seen in a top-down version of policy diff usion, such as when the U.S. federal government attaches restrictions to intergovernmen-tal grants (e.g., Welch and Th ompson 1980).4As with other coercive activities, the use of grant incentives to i nfl uence policies at lower levels of government can be either b enefi cial or harmful. Given the intergovernmental competition (noted earlier) that could result from the underprovision of redis-tributive policies, the U.S. government has long used matching grants for programs such as welfare or Medicaid, encouraging a greater level of state funding by substantially increasing the bang from a state’s buck. More direct vertical policy coercion comes in the form of unfunded mandates of states and localities or preemp-tive clauses restricting the policy discretion of states or localities. As an example of how localities prefer their own policy choices over statewide choices, Conlisk et al. (1995) note the case of North Carolina, which adopted statewide smoking restrictions in 1993 that would preempt any local laws passed after the f ollowing October 15. In the three months before the preemption took eff ect, the number of local antismoking restrictions soared from 16 to 105, indicating a strong preference for local control over state preemption. In sum, the policy diff usion concept captures the i nterrelated policy decisions across governments, whether they are based favorably on the normatively appealing concepts of cooperation and learn-ing or less favorably on the manipulation of incentives.Lesson 5: Politics and Government Capabilities Are Important to Diffusion In earlier work (Shipan and Volden 2006), we explored an instance of bottom-up policy diff usion, asking what eff ect local a ntismoking Th e particular networks in which governments are e mbedded infl uence their opportunities for learning.792 Public Administration Review • November | December 2012most complex policies, for which one state’s experiences may not translate well to other states. And there was no learning-based policy diff usion whatsoever observed among the set of policies that could be easily tried and abandoned, presumably because the internal trials served as a substitute for learning from the experiences of others.Th ese fi ndings complement earlier results in the policy diff usion literature that demonstrate the role of innovation attributes in diff usion processes beyond the policy realm (Rogers 2003). Other ways of separating one policy from another, however, have p roduced mixed fi ndings. For example, Mooney and Lee (1995, 1999) fi nd that both morality policies and economic policies diff use in similar ways, albeit for diff erent reasons. Nicholson-Crotty (2009) shows that the salience of a policy increases its rate of diff usion. And Boushey (2010) explores how some policy adoptions occur as “ o utbreaks,” where they are adopted so quickly across g overnments as to draw into question whether any diff usion processes were involved in their adoption at all.Just as the political environment and policy maker capacity help determine how and why policies diff use, so, too, does the policy context and the nature of the policies themselves. Scholars and prac-titioners should not expect the same degree of competition surrounding policies limiting youth access to tobacco as over welfare poli-cies, the same amount of learning about trash collection as about education reforms, or the same types of coercion over crime policies asfor economic and trade policies. Th e lessons off ered here, therefore, must be seen in light of political circumstances and policy contexts.Lesson 7: Decentralization Is Crucial for Policy Diffusion Th roughout the 1980s and 1990s, the U.S. federal government took steps to devolve control over some policy areas, such as welfare, to the state and local levels. More recently, such trends have reversed, with greater centralization in areas such as education and health care. Beyond the American experience, other federal systems have similarly been reassessing which levels of government should control which policy areas. Centralization has also played a major role on the international stage, such as through the creation and expansion of the European Union.Some of the benefi ts of centralization include economies of scale and reduced redundancy in maintaining policy infrastructures, l imits on harmful competitive practices across governments, and proper restrictions on negative spillovers (e.g., limiting harmful environmental pollutants that otherwise would be foisted on neigh-boring jurisdictions). Some of the costs of centralization include the loss of horizontal competition (along with its effi ciency gains), reduced policy experimentation and learning, and a decreased a bility to use local knowledge to match policies to heterogeneous local preferences. Most of these considerations involve key aspects of policy diff usion.Building on the work of Oates (1968) and Musgrave (1969),Peterson (1995) argues that state and local governments are best able to handle “developmental” policies, such as education, in which local preferences vary and experimentation and learning are competitive pressures in their redistributive policies than those that already have low benefi t levels.Th ese conditional factors and the mechanisms of diff usion may themselves change throughout the diff usion process (e.g., Kwon, Berry, and Feiock 2009). Competition matters more among early policy adopters (Mooney 2001), whereas coercion is a more potent factor among late adopters (Welch and Th ompson 1980). And the eff ect of learning increases over time, as more evidence becomes available (Gilardi, Füglister, and Luyet 2009). Because late policy adopters tend to be poorer, smaller, and less cosmopolitan than early adopters (e.g., Crain 1966; Walker 1969), their political circum-stances and policy-making capacities may well infl uence whether they take advantage of their learning opportunities, give in tocoercion, or make no policy change at all. Finally, within any given government, diff usion mechanisms take on greater or diminished importance at diff erent stages of the policy formation process,i nteracting with electoral and political constraints as a policy moves from the agenda-setting stage, to information gathering, to customi-zation (Karch 2007).Lesson 6: Policy Diffusion Depends on the PoliciesThemselvesTh e foregoing examples note a wide vari-ety of policies that have spread from onegovernment to another. Yet each policy isd iff erent, often in a variety of ways. For example, in criminal justice policy making, some policy changes, such as developing new RICO (Racketeer Infl uenced and CorruptOrganizations Act) s tandards to prosecuteorganized crime, are quite complex; others arestraightforward, such as lowering the drunk driving standard from0.10 to 0.08 percent blood alcohol content. Some changes, suchas e xtending laws on theft to include credit card theft, are easilycompatible with prior practices; others, such as “three strikes” laws,represent substantial breaks from the past. Do diff erences acrossthe complexity or compatibility of laws aff ect the nature of policydiff usion?T o answer this question, Makse and Volden (2011) study thed iff usion of 27 diff erent criminal justice laws across the Americanstates over a 30-year period. Th ey rely on expert surveys to rate eachpolicy on fi ve dimensions: complexity and compatibility (as in thef oregoing examples), as well as observability (whether the eff ectscould be easily seen by others), relative advantage (whether thepolicy is perceived to have signifi cant advantages over past policy),and trialability (whether the policy could be experimented within a limited manner). Th e authors fi nd that all fi ve factors matterin explaining the spread of these policies. Complex policies spreadmore slowly, whereas compatible policies spread more quickly.Additionally, observability, relative advantage, and trialability allenhanced the rate of adoption and diff usion.Perhaps more intriguingly, the nature of how these policies spread across the states was aff ected by the characteristics of the p olicies. For example, compared to policies whose eff ects were highly observable,those with low observability were half as likely to exhibit learning-based diff usion. Similarly, learning eff ects were cut in half for theJust as the political environment and policy maker capacity help determine how and why policies diff use, so, too, does the policy context and the nature of thepolicies themselves.。

basque

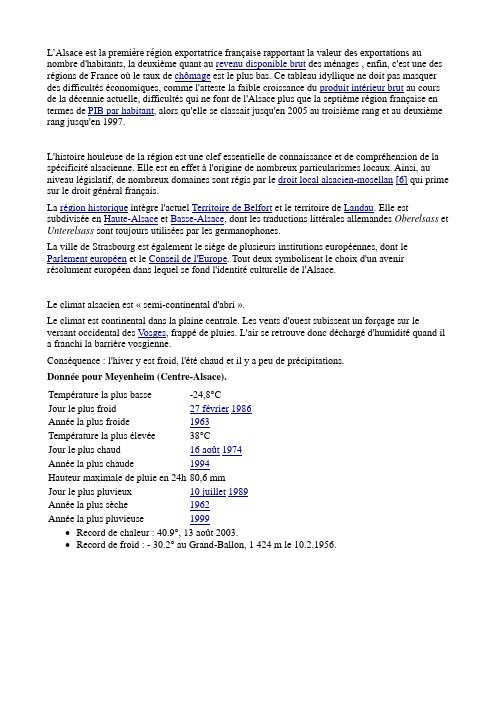

L’Alsace est la première région exportatrice française rapportant la valeur des exportations au nombre d'habitants, la deuxième quant au revenu disponible brut des ménages , enfin, c'est une des régions de France où le taux de chômage est le plus bas. Ce tableau idyllique ne doit pas masquer des difficultés économiques, comme l'atteste la faible croissance du produit intérieur brut au cours de la décennie actuelle, difficultés qui ne font de l'Alsace plus que la septième région française en termes de PIB par habitant, alors qu'elle se classait jusqu'en 2005 au troisième rang et au deuxième rang jusqu'en 1997.L'histoire houleuse de la région est une clef essentielle de connaissance et de compréhension de la spécificité alsacienne. Elle est en effet à l'origine de nombreux particularismes locaux. Ainsi, au niveau législatif, de nombreux domaines sont régis par le droit local alsacien-mosellan[6] qui prime sur le droit général français.La région historique intègre l'actuel Territoire de Belfort et le territoire de Landau. Elle est subdivisée en Haute-Alsace et Basse-Alsace, dont les traductions littérales allemandes Oberelsass et Unterelsass sont toujours utilisées par les germanophones.La ville de Strasbourg est également le siège de plusieurs institutions européennes, dont le Parlement européen et le Conseil de l'Europe. Tout deux symbolisent le choix d'un avenirrésolument européen dans lequel se fond l'identité culturelle de l'Alsace.Le climat alsacien est « semi-continental d'abri ».Le climat est continental dans la plaine centrale. Les vents d'ouest subissent un forçage sur le versant occidental des V osges, frappé de pluies. L'air se retrouve donc déchargé d'humidité quand il a franchi la barrière vosgienne.Conséquence : l'hiver y est froid, l'été chaud et il y a peu de précipitations.Donnée pour Meyenheim (Centre-Alsace).Température la plus basse -24,8°CJour le plus froid 27 février1986Année la plus froide 1963Température la plus élevée 38°CJour le plus chaud 16 août1974Année la plus chaude 1994Hauteur maximale de pluie en 24h 80,6 mmJour le plus pluvieux 10 juillet1989Année la plus sèche 1962Année la plus pluvieuse 1999∙Record de chaleur : 40.9°, 13 août 2003.∙Record de froid : - 30.2° au Grand-Ballon, 1 424 m le 10.2.1956.HistoireÀ la différence de ses provinces et régions voisines, l'Alsace n'a jamais connu de périoded'indépendance ou d'autonomie de forme centralisatrice. L'Alsace a longtemps été caractérisée par le confédéralisme. La région doit sa culture et son dialecte aux Alamans (à ne pas confondre avec les Allemands), qui s'établirent dans la région en 378, l'alsacien d'aujourd'hui est un dialectealémanique.La région fut sous l'autorité du Saint-Empire romain germanique de 962, date de sa création, jusqu'en 1648, puis elle perdit son autonomie en passant sous contrôle de la France après son annexion progressive au XVIIe siècle.C'est en Alsace que sont nés les ancêtres de la puissante dynastie des Habsbourg qui régnèrent en maîtres, plusieurs siècles durant, sur toute l'Europe centrale.535 : Alsace franqueClotaire annexe une grande partie de l'Alémanie, dont l'Alsace.∙843 : Alsace germaniqueL'Empire carolingien, la Francie, est divisée en trois parties (voir le Traité de Verdun).L'Alsace se trouve dans la partie orientale, la Lotharingie (appartenant àLouis leGermanique), qui fera partie du Saint-Empire romain germanique (fondé sous Otton Ier en 962, il durera jusqu'en 1806 sous Napoléon Ier), qui, lui, donnera approximativementl'Allemagne.∙1681 : Alsace françaiseStrasbourg se rend à Louis XIV. Toute l'Alsace appartient maintenant à la France, hormis la ville de Mulhouse qui sera conquise en 1798 par les troupes révolutionnaires. 1648 et 1675 sont des années-clés de la progression de la conquête de l'Alsace.∙1871 : Alsace allemandeVaincue, la France cède l'Alsace à l'Empire allemand.∙1919 : Alsace françaiseL'Alsace redevient française après le traité de Versailles.∙1940 : Alsace allemandeVictorieux sur la France, le IIIe Reich annexe l'Alsace.∙1944 : Alsace françaiseL'Alsace est libérée du joug nazi.C'est une forme de français régional dont les tournures sont influencées par le dialecte alsacien.L'accent alsacien se caractérise par une accentuation marquée de la première syllabe, au lieu de la dernière syllabe en langue française standard. Le français d'Alsace est marqué par le phénomène de calques germaniques. Le français d'Alsace comporte de nombreux mots empruntés à l'alsacien.Une culture de la tableL'Alsace, l'une des régions les plus « étoilées » par les guides, valorise au mieux... et galvaude parfois son important répertoire gastronomique. Malgré l'afflux des touristes et une banalisation certaine, sensible à Strasbourg et dans plusieurs cités historiques situées sur la Route des Vins, bon nombre de restaurants se révèlent de qualité et, assez souvent, fort conviviaux. Les familles alsaciennes continuent de les fréquenter avec une remarquable assiduité et les repas d'amis sont beaucoup plus habituels qu'ailleurs. Il y a foule le dimanche midi dans les restaurants et les fermes-auberges de bonne réputation, même à bonne distance des grands centres (vallée de Munster, Haute-Bruche, « Pays des choux », Ried, région de Brumath, Outre-Forêt, Florival, Sundgau).Parmi les recettes et plats traditionnels d'Alsace figurent notamment la tarte à l'oignon (Zewelkueche), le cervelas vinaigrette, les asperges (Sparichle) accompagnées de trois sauces, cette potée typique qu'est le Baeckeoffe, la tarte flambée, plus exactement : Flamekuche ou Flammekueche, maintenant connue de toute la France, autrefois spécialité d'une partie du Bas-rhin proche de Strasbourg, la choucroute, le Schiffala ou Schiffele, la pâte roulée au porc et au veau Fleischschnacka. Le gibier — le droit de la chasse est particulier dans la région — et les cochonnailles, malgré la faible production porcine locale, ont la part belle.Le méridional Sundgau vante ses carpes frites.Le pâté de foie gras d'oie, produit depuis le XVIIe siècle, passe pour une spécialité alsacienne... autant que landaise ou périgourdine (une version de ce pâté, sous une croûte de pâte ronde, futprésentée en 1780 à la table du gouverneur militaire de Strasbourg). Il est à noter que l'Alsacen'élève pas beaucoup plus d'oies que de porcs, dont elle fait pourtant une abondante consommation charcutière. En revanche, elle élève de plus en plus de canards pour la production de foie gras.Les desserts traditionnels sont nombreux : kugelhopf ou kougelhopf, dont le nom est souvent "francisé" en Kouglof, tartes aux fruits, notamment aux quetsches et au fromage blanc, grandevariété de biscuits et de petits gâteaux, appelés Bredala (les spécialités de l'Avent), pain d'épice. (Les dénominations de produits et de plats, en dialecte, varient beaucoup d'une mini-région à l'autre : les transcriptions hasardeuses, parfois les francisations assez abusives, comme « tarte flambée », sont pléthore. Mais "tout le monde se comprend". Peu importe que l'on transcrive Baeckeoffe,Bäckkeoffe, Bækoffa, Bækenoffa, Bækaoffe : il s'agira toujours d'un mélange de viandes, de pommes de terre, d'oignons, arrosé de vin blanc, très longuement cuit au four dans une terrinehermétiquement fermée. Bien que les termes dialectaux plus ou moins francisés puissent s'écrire entièrement en lettres minuscules, l'usage de la majuscule initiale, à l'allemande, s'est souvent conservé).Les vins d'Alsace sont issus de plusieurs cépages et répondent aux spécifications de trois AOC. Ils'agit surtout de blancs, le plus souvent secs ou secs tendres, parfois très riches en sucre résiduel (vendanges tardives, sélection de grains nobles), également élaborés en crémant, bien moindrement de rouge (un seul cépage, le pinot noir) ou de rosé. Les alsaciens soulignent volontiers que le alsaces permettent un grand nombre d'accords mets-vins.La bière est toujours brassées dans le Bas-Rhin, mais Meteor demeurait, en 2008, la dernière affairefamiliale (Schutzenberger ayant cessé ses activités quelques années auparavant).。

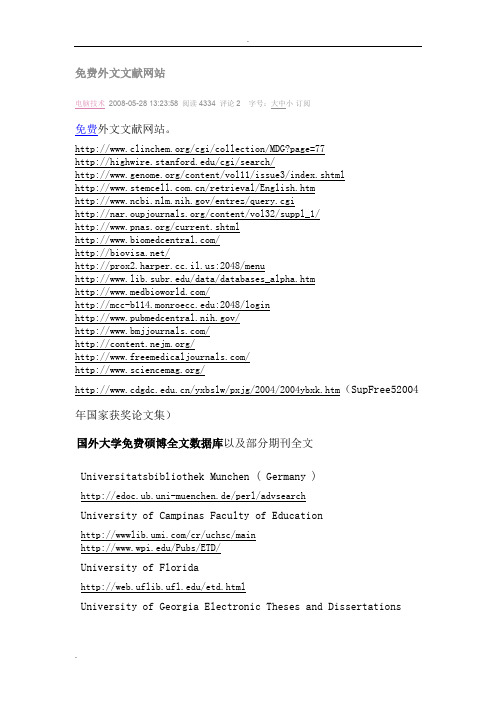

免费外文文献网站

免费外文文献网站电脑技术2008-05-28 13:23:58 阅读4334 评论2 字号:大中小订阅免费外文文献网站。

/cgi/collection/MDG?page=77/cgi/search//content/vol11/issue3/index.shtml/retrieval/English.htm/entrez/query.cgi/content/vol32/suppl_1//current.shtml//:2048/menu/data/databases_alpha.htm/:2048/login//////yxbslw/pxjg/2004/2004ybxk.htm(SupFree52004年国家获奖论文集)国外大学免费硕博全文数据库以及部分期刊全文Universitatsbibliothek Munchen ( Germany )http://edoc.ub.uni-muenchen.de/perl/advsearchUniversity of Campinas Faculty of Education/cr/uchsc/main/Pubs/ETD/University of Florida/etd.htmlUniversity of Georgia Electronic Theses and Dissertations(Summer 1999 to present)/cgi-bin ... on=search&_cc=1Australian Digital Theses Program.au/University of New Orleans/University of Pretoria : Electronic Theses and Dissertations http://upetd.up.ac.za/University of Puerto Rico Mayaguez Campus/tesisdigitales.htmUniversity of Tennessee, Knoxville:90/cgi-perl/dbBroker.cgi?help=148niversity of South Florida/cgi-bin/ETD-db/ETD-search/searchUniversity of Texas - Austin/cr/utexas/mainUniversity Utrecht(Electronic Theses and Dissertations) http://laurel.library.uu.nl/cgi-bin/mus212/dialogserver?DB=da_enW Electronic Thesis Databasehttp://etheses.uwaterloo.ca/Uppsala Universitiethttp://publications.uu.se/theses/Virginia Commonwealth University/ETD-db/ETD-search/searchWorcester Polytechnic Institute/ETD-db/ETD-search/searchYale University Library/ETD-db/ETD-search/searchThe George Washington University/ETD-db/ETD-search/searchhe Pennsylvania State University"s electronic Theses and Dissertations Archives/ETD-db/ETD-search/searchNorth Carolina State University/ETD-db/ETD-search/searchThe New Jersey Institute of Technology"s Electronic Theses & Dissertations/etd/index.cfmNaval Postgraduate School Theses/home/theses.htmational Taiwan Normal Universityhttp://140.122.127.250/cgi-bin/gs/egsweb.cgi?o=dentnucdrUniversity of Mississippi Rowland Medical Library/free-e_res.htm#Journals/ETD-db/ETD-search/search/ETD-db/ETD-search/search//subjects/life/books.html/ETD-db/ETD-search/searchhttp://sunzi.lib.hku.hk/hkuto/main.jsp/HSRC/JHSR//mrkshared/mmanual/section13/sec13.jsp文献数据库大全一、中文数据库1、清华同方学术期刊网/中国最大的数据库,内容较全。

路易维尔大学与圣约翰费舍尔大学哪个好

路易维尔大学与圣约翰费舍尔大学哪个好?具体请咨询立思辰留学360。

路易维尔大学

路易斯维尔大学(University of Louisville,或称U of L)是一所位于美国肯塔基州路易斯维尔市的研究型州立大学。

该大学建立于1798年,当时是美国第一座市立的公共大学,也是第一批建立在美国阿勒格尼山脉西边的大学之一。

由肯塔基州议会授权的路易维尔大学目前依然秉承其一贯“超群大都市区研究型大学”的传统。

路易斯维尔大学的学生来自很多地方,包括一共有来自120个县的肯塔基州的118个县、美国所有的州、和116个不同的国家。

该大学一共提供70个本科专业、78项硕士学位课程、以及22项博士学位课程。

圣约翰费舍尔大学

圣约翰费舍尔学院(罗彻斯特)坐落于美国纽约州罗彻斯特,成立于1948年,是一所私立性质的文理学院。

圣约翰费舍尔学院(罗彻斯特)强调学生对于传统学科以及那些直接导向职业领域的自由学习。

学院对于合格的高校学生,教师和工作人员的接纳,是不论宗教或文化背景的。

圣约翰费舍尔学院(罗彻斯特)现有31个本科专业, 11个硕士专业以及3个博士点。

圣约翰费舍尔学院五个最热门专业分别是教育学(24 %),商业、管理、营销及相关专业(23 %),通信、新闻和相关专业(11 %),心理学(8 %)以及社会科学(6 %)。

2007年9月,学院被U.S. News & World Report 评为2008全美最好的大学和北部地区最好的研究生院校之一。

蒙特克莱尔州立大学Montclair State University

官方网站:/蒙特克莱尔州立大学Montclair State University蒙特克莱尔州立大学Montclair State University ,MSU建于1908年,位于新泽西州,是美国新泽西州一所公立的大学,是新泽西州第二大的学校,而且也是本州成长最快的大学之一。

如果对海外留学有疑问,可以在线咨询小马过河留学专家,也可拨打全国免费咨询电话:4008-123-267!蒙特克莱尔州立大学已通过美国中部诸州高等教育学院与学校委员会权威认证,而且蒙特克莱尔州立大学许多学术学科都经过相关组织认证。

蒙特克莱尔州立大学Montclair State University共有师生近两万多人,授学士,硕士,及博士学位。

学校占地200英亩,环境优美,交通便利,校内建筑风格多种多样。

蒙特克莱尔州立大学距离纽约城14公里,艺术文化资源十分丰富。

同时,新泽西北部的商业和文化氛围也很吸引在校的学生。

近年来蒙特克莱尔州立大学Montclair State University不断扩大外国学生招生数量,并与中国, 俄国, 韩国,印度,澳国,南美等不少国家的学校建立了学术往来与合作。

蒙特克莱尔州立大学Montclair State University商学院是全美一千五百所高等院校商学院中,经美国联邦高等商学教育认证委员会(AACSB)认证批准的三百七十五所之一。

目前开设国际贸易,市场管理,商业信息管理,会计及税法管理,财经管理等专业.授商业管理学士(BS),工商管理硕士(MBA)学位,该校发展最快,学生人数最多的学院。

蒙特克莱尔州立大学Montclair State University由七个学院组成,分别是:教育与公共事业学院,人文学科与社会科学学院,科学与数学学院,John J. Cali音乐学院,文学院,商业学院和研究生学院。

本科:人类发展学人类生态学教育管理学体育数学生物学滑雪计算机环境管理学会计金融营销零售管理管理经济学英语音乐美术广播音乐音乐教育研究生:人类发展学人类生态学教育管理学体育应用社会学应用语言学数学生物学化学物理计算机环境管理学MBA 美术音乐。

Taxes, Loans, Credit and Debts in the 15th Century