Corporate Governance and Institutional Ownership

中国公司治理热点问题分析-AsianCorporateGovernanceAssociation

澳大利亚 1. 新加坡 2. 中国香港

2012年 2014年 2016年

69 66 64 65 78 67 65

2014年到2016 公司治理改革方向 年的变化

(+3) 总体来说没有大问题,但也许危机潜伏 行动才会有反应:香港市场的常态

3. 日本

4. 中国台湾 5. 泰国

55

53 58

60

56 58

亚洲公司治理协会

“中国公司治理热点问题分析”

嘉宾:

亚洲公司治理协会秘书长 艾哲明

深圳证券交易所 2017年3月22日

深圳证券交易所 2017年3月22日

1

主要内容

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7.

亚洲公司治理协会简介 公司治理观察报告2016-概览 公司治理观察报告2016-中国大陆 中国公司治理现状 中国公司治理面临的挑战 中国公司治理热点议题讨论 问答环节

6. Oekom Research

7. Vigeo Eiris 8. Asian Corporate Governance Association

9. Hermes Equity Ownership Services

10. Solaron

深圳证券交易所 2017年3月22日

9

2016年全球责任投资独立研究机构评选结果

12

概览- 2016年市场分类得分

市场

移到严格执法上 北亚地区在此次调查中进步明显 金融市场的监管者与政府官员之间的 意见分歧越趋明显 监管机构不是市场公司治理水平好坏 的唯一责任方—未来的十五年,重心

将会围绕系统中的其他参与者作出他

们应有的贡献

深圳证券交易所 2017年3月22日

澳科大硕士论文范文格式

題目:公司治理與財務績效關聯性 之研究-台灣新上市公司為例

Title:

姓名 Name 學號 Student No. 學院 Faculty 課程 Program 專業方向 Major 指導教師 Supervisor 日期 Date

Key words: corporate governance, financial performance, corporate governance variable, corporate governanceLeabharlann level.III目錄

第一章 緒論………………………………………………………………………1 第一節 研究動機與目的………………………………………………………1 第二節 研究範圍與限制………………………………………………………10 第三節 研究流程與論文架構 ………………………………………………13

科技產業轉投資家數越多,則公司治理程度對會計績效,亦呈正 向相關。 六、推動強化公司治理政策實施後,有參與管理的公司對經營績效有 正向的影響 七、法令規範後,公司治理與經營績效表現較佳

I

八、高科技產業的公司治理表現較佳 關鍵詞:公司治理、財務績效、公司治理變數、公司治理程度

II

Abstract

This research used 279 companies established between 1999 and 2004 as the sample, examining the relationship between corporate governance and financial performance. Corporate governance variable during the time when company gets started is used to examine the effect of corporate governance on accounting effectiveness after the company has been on the market, as well as the effect on the return rate during the first 30 days of the company’s opening. Further analysis from literature review on corporate governance, using single measurement, is according to the median of the level of corporate governance and the rating of corporate governance variable, to cross examine its effect on financial performance. Also, a comparison of the effect on strengthening corporate governance using “Stock Exchange Listing Standards” before and after the company was listed on the stock market on corporate governance and financial performance. Correlation, T-test, and Regression analysis were used to examine three hypotheses. Findings include: 1) Company characteristics High Tech industry has better corporate governance mechanism than traditional industries. 2) Characteristic of corporate governance level High corporate governance companies have better accounting effectiveness and market performance. 3) Correlation between economic cycle and industry type v.s. corporate governance and

cdcs单词资料

1.Agency Theory 代理理论This choice of agency theory is in harmony with focusing on institutional venture capital type and on the investor’s perspective.选择代理人理论是与关注机构风险资本类型和投资人视角相一致的。

2.corporate governance 公司治理;企业管治,企业治理;公司管治I would like to share with you some ideas about corporate governance and development.我想在这里与诸位交流我自己对公司治理和发展问题的一些看法。

3.stakeholder 利益相关者股东保证金保存人赌金保管人We all have ample reason to support this direction. The World is a stakeholder in China’s future.我们有充分的理由支持这一发展方向,世界是中国未来发展的利益攸关方。

4.major issue 重大问题This, of course, is another major issue, but one far more for parents and society than the schools themselves.当然,这也是一个十分重要的问题,但这个问题更多的是家长和社会的问题而不是学校的。

5.encounter vt. 遭遇,邂逅;遇到n. 遭遇,偶然碰见vi. 遭遇;偶然相遇to encounter a new situation 意外地遇到新形势6.syllabus n. 教学大纲,摘要;课程表All of these details are in the syllabus and I'll stick around and answer questions.所有这些细节都在教学大纲里,我会在这里留一会,回答你们的问题7.code n. 代码,密码;编码;法典vt. 编码;制成法典vi. 指定遗传密码But we have not yet implemented this in the code.但我们在代码中尚未实现此功能。

公司治理岗 英文

公司治理岗英文

1. Corporate Governance Position

2. Role in Corporate Governance

3. Job in Corporate Governance

4. Position in Corporate Governance Function

5. Corporate Governance Function Role

这些翻译都表达了在公司治理方面的工作职位或职责。

具体使用哪个翻译取决于上下文和使用习惯。

"Corporate Governance"指的是公司治理,涉及公司的组织架构、决策制定、监督机制、合规性等方面。

如果你需要更具体的翻译,可以提供更多关于该岗位的信息,例如工作内容、职责范围等,我将为你提供更准确的翻译。

此外,公司治理岗位通常涉及监督和管理公司的各个方面,确保公司的运营符合法律、法规和道德标准,并促进公司的可持续发展和价值创造。

无论是在国内还是国际环境中,公司治理岗位都非常重要,因为它有助于维护公司的透明度、问责制和良好的治理实践,从而保护股东、投资者和其他利益相关者的利益。

如果你对公司治理岗位有更深入的问题或需要更多信息,请随时提问。

我将尽力为你提供帮助。

企业三权分立治理体系

企业三权分立治理体系英文回答:Corporate Tripartite Governance System.The corporate tripartite governance system refers to the division of corporate governance power among three different parties: shareholders, directors, and managers. This system is designed to ensure that each party has arole in the governance of the corporation and that no one party has too much power.The shareholders are the owners of the corporation and have the ultimate authority over the company. They elect the directors, who are responsible for overseeing the management of the company. The managers are responsible for the day-to-day operations of the company.This system of checks and balances is designed to prevent any one party from gaining too much power and toensure that the corporation is run in the best interests of all stakeholders.Chinese 回答:企業三權分立治理體系。

公司治理 外文书籍

公司治理外文书籍

以下是一些关于公司治理的外文书籍推荐:

《公司治理》(Corporate Governance) - 国立政治大学财务管理研究所教授郑志弘著,详细介绍了公司治理的理论框架、机制和实务,适合初学者。

《Corporation Governance: Principles, Policies, and Practices》- R. I. Tricker著,研究公司治理的经典著作,综合了理论和实践,并涵盖了全球

范围内的案例研究。

《Good to Great by Jim Collins》- 通过分析包括可口可乐、英特尔、通

用电气等在内的著名公司,讨论他们是如何保持长期的发展,这对中国公司建立百年老店的目标应该很有启发。

《First, break all the rules by Marcus Buckingham and Curt Coffman》- 通过大量的调查和分析,讲述优秀的经理人是如何鼓励员工实现潜能的,

而不是通过简单的金钱和福利手段,对于真正理解美国公司的管理和文化很有实战意义。

《Strength Finder by Tom Rath》- 讲述如何找到和充分发挥个人的长处,跟传统文化的一些提高自己的短处的思路有很大的不同。

此外,还有《董事会运作手册》、《公司治理:中国学习与实践》等书籍,这些书籍都是关于公司治理的经典之作,对于深入了解公司治理的原理和实践非常有帮助。

A Survey of Corporate Governance

American Finance AssociationA Survey of Corporate GovernanceAuthor(s): Andrei Shleifer and Robert W. VishnySource: The Journal of Finance, Vol. 52, No. 2 (Jun., 1997), pp. 737-783Published by: Blackwell Publishing for the American Finance AssociationStable URL: /stable/2329497Accessed: 23/03/2010 01:01Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use.Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=black.Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission.JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@.Blackwell Publishing and American Finance Association are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserveand extend access to The Journal of Finance.。

第六章:公司治理ppt课件

内部治理机制

所有权集中程度:

由大股东的数量及其控制的股份占总股份的比例决定; 大股东通常对公司发行的股份控股5%以上。

董事会

由股东选出的,代表股东利益来行使对企业高层管理者 进行监督和控制的群体。

管 理 者报酬

通过工资、奖金和长期激励性报酬如股票期权将经理人 和所有者利益联系起来的公司治理机制。

外部治理机制

接管约束( takeover constraint )

被另一家企业收购的风险

财 务 报 表 与 审计 媒 体 和 公 众 活动 ……

The concept of stakeholder Agency theory and corporate governance Mechanism of corporate governance Corporate governance in different countries

Trends of corporate governance

英美公司治理模式

所有权较为分散,外部监督为主; 股权分散的股东不能有效地监控管理层的行为, “弱股东,强管理层”; 依赖公司治理市场,以及破产、法院等外部机制予 以 解 决。 典型代表:美国、英国、加拿大、澳大利亚等。

安然事件后美国公司治理的改革

奖金认股选择权和买卖股票的收益都必须返还公司sec解职令如果sec认为公众公司董事和其他管理者存在欺诈行为或者不称职可以有条件或者无条件暂时或者永久禁止此人在公众公司担任董事和其他管理职务以前sec须向法院申请解职令事或者其他管理者为实质不称职同样大小的气缸容积可以发出更大的指示功气缸工作容积的利用程度越佳

萨班法案(Sarbanes-Oxley Act)

Corporate-governance

Title SheetThe Report QuestionCorporate governance,how a company is run,is becoming an important issue for companies to consider due to numerous recent high—profile corporate failures. As a result, businesses are starting to use a corporate governance statement as a way to communicate their corporate governance practices and promote their ethical credentials to interested parties, such as shareholders. This statement is often incorporated into the company's annual report. To assist with the development of good corporate governance and clear corporate governance statements the ASX Corporate Governance Council has developed a set of principles and recommendations to guide companies。

What is corporate governance and why is it an important issue for companies? Select the principles in the ASX Corporate Governance Council’s Corporate Governance Principles and Recommendations that are most relevant to your BABC001 industry。

企业管理英文文献综述范文

企业管理英文文献综述范文Corporate Governance: A Comprehensive Literature Review.Introduction.Corporate governance plays a pivotal role in ensuringthe transparency, accountability, and integrity of organizations. It encompasses the systems and processes by which companies are directed, managed, and controlled. This literature review examines the key aspects of corporate governance, including board structure, shareholder rights, executive compensation, and regulatory compliance.Board Structure.The board of directors is the highest decision-making body in a corporation. Its composition and structure are essential for effective governance. Research has shown that boards with a diverse range of perspectives, including independent directors, women, and members from differentethnic backgrounds, enhance decision-making and reduce the risk of groupthink (Adams & Ferreira, 2007; Carter & Lorsch, 2004).Additionally, the size and composition of the board can influence its effectiveness. Smaller boards may be more efficient, while larger boards may offer a wider range of expertise. However, excessive board size can lead to coordination issues and slower decision-making (Bebchuk & Cohen, 2005; Jensen & Meckling, 1976).Shareholder Rights.Shareholders are the owners of a corporation and possess certain rights, including the right to vote on corporate decisions, receive dividends, and accessfinancial information. Protecting shareholder rights is crucial for ensuring accountability and transparency.Research suggests that strong shareholder rights enhance firm value (Arya & Mittendorf, 2008; Shleifer & Vishny, 1997). Institutional investors, such as pensionfunds and mutual funds, play a significant role in protecting shareholder interests by actively monitoring board performance and exercising voting rights (Gillan & Starks, 2000; Gompers, 2003).Executive Compensation.Executive compensation is a contentious issue in corporate governance. Excessive executive pay can erode shareholder value and undermine public trust. Research has identified a strong correlation between CEO compensation and firm performance (Murphy, 1985; Jensen & Murphy, 1990). However, it is essential to balance the need to attract and retain talented executives with the interests of shareholders.Effective compensation systems align executive incentives with firm goals and promote long-term value creation. Performance-based pay and stock options are common mechanisms used to achieve this alignment (Malmendier & Tate, 2008; Jensen & Murphy, 1990).Regulatory Compliance.Corporate governance frameworks are often complemented by regulatory compliance requirements imposed by government agencies. These regulations aim to protect investors, promote market integrity, and prevent corporate misconduct.Compliance with regulatory frameworks is essential for maintaining public trust and avoiding legal penalties. Companies can implement compliance programs that establish clear policies, provide training, and monitor adherence to regulations (Proffitt & Margolis, 2007; Song & Shim, 2009).Codes of Conduct and Ethical Considerations.Codes of conduct and ethical considerations play a significant role in guiding corporate behavior. These guidelines establish standards of integrity, accountability, and ethical decision-making for employees and management.Research has shown that strong codes of conduct can enhance employee morale, reduce misconduct, and mitigatereputational risks (Crane & Matten, 2010; Johnson, Johnson, & Holloway, 2010). Ethical considerations are particularly important in industries where social and environmental factors are relevant (Gibson, 2000; Mackey, Sisodia, & Wolfe, 2013).Corporate Governance and Firm Performance.Empirical research has consistently demonstrated a positive relationship between strong corporate governance practices and firm performance. Companies with effective governance structures and policies tend to exhibit higher profitability, lower risk, and better long-term value creation (Aguilera & Jackson, 2003; Bhagat & Bolton, 2008; Claessens, Djankov, & Fan, 2002).Emerging Trends in Corporate Governance.Corporate governance is constantly evolving to address emerging challenges and opportunities. Key trends include:Sustainability and ESG considerations: Investors andstakeholders are increasingly demanding that corporations adopt sustainable practices and consider environmental, social, and governance (ESG) factors.Technology advancements: Advancements in technology, such as blockchain and artificial intelligence, are transforming corporate governance practices and enabling greater transparency and efficiency.Diversity and inclusion: Companies are recognizing the importance of diversity and inclusion in boardrooms and throughout the organization.Conclusion.Corporate governance is a critical aspect of modern business management. By fostering transparency, accountability, and ethical behavior, effective governance practices protect stakeholders, promote firm performance, and contribute to a stable and ethical business environment. As corporate governance continues to evolve, it is vitalfor organizations to stay abreast of emerging trends andbest practices to ensure the long-term success of their enterprises.。

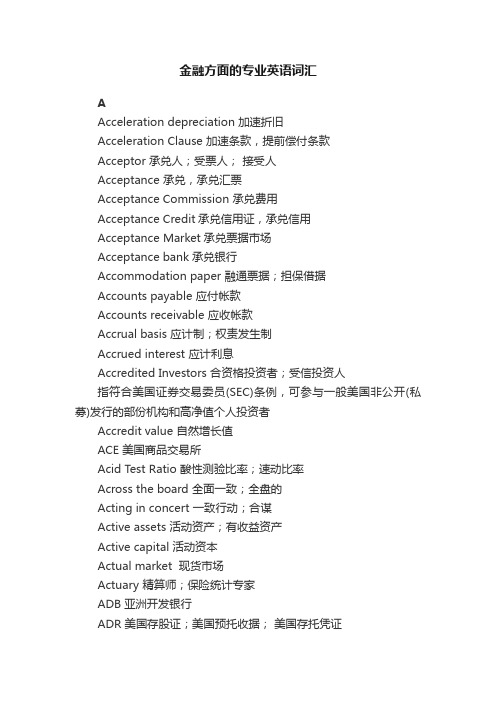

金融方面的专业英语词汇

金融方面的专业英语词汇AAcceleration depreciation 加速折旧Acceleration Clause 加速条款,提前偿付条款Acceptor 承兑人;受票人;接受人Acceptance 承兑,承兑汇票Acceptance Commission 承兑费用Acceptance Credit承兑信用证,承兑信用Acceptance Market承兑票据市场Acceptance bank承兑银行Accommodation paper 融通票据;担保借据Accounts payable 应付帐款Accounts receivable 应收帐款Accrual basis 应计制;权责发生制Accrued interest 应计利息Accredited Investors 合资格投资者;受信投资人指符合美国证券交易委员(SEC)条例,可参与一般美国非公开(私募)发行的部份机构和高净值个人投资者Accredit value 自然增长值ACE 美国商品交易所Acid Test Ratio 酸性测验比率;速动比率Across the board 全面一致;全盘的Acting in concert 一致行动;合谋Active assets 活动资产;有收益资产Active capital 活动资本Actual market 现货市场Actuary 精算师;保险统计专家ADB 亚洲开发银行ADR 美国存股证;美国预托收据;美国存托凭证ADS 美国存托股份Ad valorem 从价;按值Affiliated company 关联公司;联营公司After date 发票后,出票后After-market 后市Agreement 协议;协定All-or-none order 整批委托Allocation 分配;配置Allotment 配股Alpha (Market Alpha) 阿尔法;预期市场可得收益水平Alternative investment 另类投资American Commodities Exchange 美国商品交易所American Depository Receipt 美国存股证;美国预托收据;美国存托凭证 (简称“ADR ”参见ADR栏目)American Depository Share 美国存托股份Amercian Stock Exchange 美国证券交易所American style option 美式期权Amex 美国证券交易所Amortizable intangibles 可摊销的无形资产Amortization 摊销Amsterdam Stock Exchange 阿姆斯特丹证券交易所Annual General Meeting 周年大会Annualized 年度化;按年计Annual report 年报;年度报告Anticipatory breach 预期违约Antitrust 反垄断APEC 亚太区经济合作组织(亚太经合组织)Appreciation [财产] 增值;涨价Appropriation 拨款;经费;指拨金额Arbitrage 套利;套汇;套戥Arbitration 仲裁Arm's length transaction 公平交易Arrears拖欠,欠款Articles of Association 公司章程;组织细则At-the-money option 平价期权;等价期权ASEAN 东南亚国家联盟 (东盟)Asian bank syndication market 亚洲银团市场Asian dollar bonds 亚洲美元债券Asset Allocation 资产配置Asset Backed Securities 资产担保债券Asset Management 资产管理Asset swap 资产掉期Assignment method 转让方法;指定分配方法ASX 澳大利亚证券交易所Auckland Stock Exchange 奥克兰证券交易所Auction market 竞价市场Authorized capital 法定股本;核准资本Authorized fund 认可基金Authorized representative 授权代表Australian Options Market 澳大利亚期权交易所Australian Stock Exchange 澳大利亚证券交易所BBack-door listing 借壳上市Back-end load 撤离费;后收费用Back office 后勤办公室Back to back FX agreement 背靠背外汇协议Bad check空头支票,坏票,退票Bad debts risk坏账风险Bailout指相关机构对周转有问题的银行提供财务援助的措施,如融资Balance of payments 国际收支平衡;收支结余Balance of trade 贸易平衡Balance sheet 资产负债表Balloon maturity 期末放气式偿还Balloon payment 最末期大笔还清Bancogiro银行资金划拔制度Bank, Banker, Banking 银行;银行家;银行业Bank account银行往来账户Bank Charge银行手续费(来澳洲的之前一定要问清楚,我吃亏了)Bank for International Settlements 国际结算银行Bank holding company 银行控股公司Bank interest 银行存款利息,银行贷款利息Bankruptcy 破产Bank loan银行贷款Base day 基准日Base rate 基准利率Basis point 基点;点子Basis swap 基准掉期Bear market 熊市;股市行情看淡Bearer 持票人Bearer stock 不记名股票Behind-the-scene 未开拓市场Below par 低于平值Benchmark 比较基准Beneficiary 受益人Beta (Market beta) 贝他(系数);市场风险指数Best practice 最佳做法;典范做法Bills department 押汇部Bill of exchange 汇票BIS 国际结算银行Blackout period 封锁期Block trade 大额交易;大宗买卖Blue chips 蓝筹股Blue Sky [美国] 蓝天法;股票买卖交易法Board of directors 董事会Bona fide buyer 真诚买家Bond market 债券市场,债市Bonds 债券,债票Bonus issue 派送红股Bonus share 红股Book value 帐面值Bookbuilding 建立投资者购股意愿档案;建档;询价圈购BOOT 建造;拥有;经营;转让BOT 建造;经营;转让Bottom line 底线;最低限度Bottom-up 由下而上(方法)Bounced cheque 空头支票Bourse 股票交易所(法文)BP (Basis Point) 基点Brand management 品牌管理Break-up fees 破除协议费用Break-up valuation 破产清理价值评估Breakeven point 收支平衡点Bridging loan 临时贷款/过渡贷款Broad money 广义货币Broker, Broking,Brokerage House 经纪;证券买卖;证券交易;证券行;经纪行Brussels Stock Exchange 布鲁塞尔证券交易所BSSM 建造/设备供应-服务/维修Bubble economy 泡沫经济Build, Operate and Transfer 建造、经营、转让Build, Own, Operate and Transfer 建造;拥有;经营;转让Build/Supply-Service/Maintain 建造/设备供应-服务/维修Bull market 牛市;股市行情看涨Bullets 不得赎回直至到期(债券结构之一)Bullish 看涨; 看好行情Bundesbank 德国联邦银行;德国央行Business day 营业日Business management 业务管理;商务管理;工商管理Business studies 业务研究;商业研究Buy-back 回购Buy-side analyst 买方分析员Buyer's credit 买方信贷(进口)Buyout 收购;买入By-law 细则;组织章程CCAC 巴黎CAC指数CAGR 复合年增长率Calendar year 月历年度Call-spread warrant 欧洲式跨价认股权证Call option 认购期权Call protection/provision 赎回保障/条款Call warrant 认购认股权证Callable bond 可赎回债券Cap 上限Capacity 生产能力;产能CAPEX 资本支出Capital Adequacy Ratio 资本充足比率Capital base 资本金;资本基楚Capital expenditure 资本支出Capitalization >资本值Capital markets 资本市场;资金市场Capital raising 融资;筹集资金Carry trade 利率差额交易;套利外汇交易;息差交易Cash-settled warrant 现金认股权证Cash earnings per share 每股现金盈利Cash flow 现金流量CCASS 中央结算及交收系统CD 存款证CDS 参见Credit Default Swap栏目CEDEL 世达国际结算系统(即欧洲货币市场结算系统) Ceiling 上限Ceiling-floor agreement 上下限协议Central Clearing & Settlement System 中央结算及交收系统CEO 行政总栽;行政总监;首席执行官CEPA 即2003年6月29日于香港签署的《内陆与香港关于建立更紧密经贸关系的安排》,是英文“The Closer Economic Partnership Arrangement (CEPA) between Hong Kong and the Mainland”的简称。

国际财务管理课本单词

第二章exchange rate汇率 mergers并购 restructuring重组 monetary policy货币政策 exchange rate policy汇率政策 debt crisis债务危机European Monetary Union欧洲货币联盟fiscal union财政联盟 citizens referendum全民公投第四章全球各地的公司治理 corporate governance around the world公司治理 corporate governance股东财富最大化 Shareholder wealth maximization忠诚职责 duty of loyalty公司治理机制 corporate governance system股东 shareholder管理人员managers利益相关者 stakeholders上市公司 the public corporation利益冲突 the conflicts of interest代理问题 agency problem 自由现金流 free cash flows董事会 board of directors外部董事 outside directors激励合约 incentive contracts所有权集中 concentrated ownership利益联盟效应 alignment管理防御效应entrenchment透明度 accounting transparenc敌意收购 no stile takeover法律和公司治理 law and corporate governance英国普通法 English common law法国大陆法French civil law德国大路法 german civil law斯堪的纳维亚大陆法Scandinavian civil law用脚投票 voting by foot用手投票 voting by hand华尔街 the wall street 第五章American terms 美式标价 European terms 欧式标价Cross-exchange rate 套算汇率 spot rate 即期汇率 Forward rate 远期汇率 Foreign exchange market 外汇市场Interbank market 银行间同业市场 Spot market 即期市场Forward market 远期市场 retail market 零售市场Wholesale market 批发市场OTC 场外市场Client market客户市场 ask price卖出报价 Bid price买入报价 currency against currency 货币对货币互换Direct quotation 直接标价 indirect quotation 间接标价Forward premium /discount 远期升水/贴水Triangular arbitrage三角套利Correspondent banking relationships 通汇关系Appreciate 升值depreciate 贬值第六章套利 arbitrage 套利组合arbitrage portfolio 抵补套利covered interest arbitrage 市场假说efficient market hypothesis 费雪效应fisher effect 远期预期平价Forward expected parity 实际汇率Real exchange rate 利率平价 interest rate parity 国际费雪效应international fisher effect 一介定律law of one price 基本分析法fundamental approach 不可贸易商品Non-tradable Goods购买力平价purchasing power parity 货币数量理论 Quantity theory of money 技术分析法technical approach 非抵补利率平价 uncovered interest rate parity 自我筹资self-financing 汇率决定exchange rate determination 汇率预测forecasting exchange rate 随机漫步假说random walk hypothesis 第七章American option 美式期权 Exercise price/Striking price 执行European option 欧式期权 At-the-money 平价Settlement price 结算价格In-the-money 价内 Long 多头Out-of-money 价外Short 空头Call option看涨期权 Writer 开立者Put option 看跌期权 Open interest 未平仓合约 Futures 期货 Option 期权 Hedgers 套期保值者 speculators 投机者Contract size 合约规模 standardized 标准化Derivative security 衍生证券 premium 期权费第九章销售额 sales 变动成本 variable costs固定制造费用 fixed overhead costs 折旧额 depreciation allowances税前净利润 net profit before tax 所得税 income tax税后利润 profit after tax 加回折旧add back depreciation以英镑计算的经营现金流量 operating cash flow亿美元计算的经营现金流量 in pounds/dollars第十章利润表:income statement销售收入:sales revenue折旧费用: depreciation净营业利润:net operating income所得税: income tax税后利润:profit after tax外汇损益:foreign exchange gain(loss)净利润:net income股利:dividends留存收益增加额: addition to retained earings现金流量表 cash flow statement资产负责表 balance sheet现金 cash应收账款 accounts receivable存货 inventory固定资产净额 net fixed assets总资产 total assets应付账款 accounts payable应付票据 notes payable流动负债 current liabilities长期负债 long-term debt普通股 common stock留存收益 retained earnings累计换算调整 CTA(cumulative translation adjustment)利润表 INCOME STATEMENT产品销售净额Net sales of products减:产品销售税金Less:Sales tax产品销售成本 Cost of sales产品销售毛利 Gross profit on sales减:销售费用 Less:Selling expenses管理费用General and administrative expenses财务费用Financial expenses汇兑损失(减汇兑收益) Exchange losses (minus exchange gains)产品销售利润Profit on sales加:其他业务利润Add:profit from other operations营业利润Operating profit加:投资收益Add:Income on investment加:营业外收入Add:Non-operating income减:营业外支出Less:Non-operating expenses加:以前年度损益调整Add:adjustment of loss and gain for previous years利润总额 Total profit减:所得税 Less:Income tax净利润 Net profit资产负债表 Balance Sheet项目 ITEM 项目 ITEM货币资金 Cash 短期借款 Short-term loans短期投资 Short term investments 应付票款 Notes payable应收票据 Notes receivable 应付帐款 Accounts payab1e应收股利 Dividend receivable 预收帐款 Advances from customers应收利息 Interest receivable 应付工资 Accrued payro1l应收帐款 Accounts receivable 应付福利费 Welfare payable其他应收款 Other receivables 应付利润(股利) Profits payab1e预付帐款 Accounts prepaid 应交税金 Taxes payable期货保证金 Future guarantee 其他应交款 Other payable to government应收补贴款 Allowance receivable 其他应付款 Other creditors应收出口退税 Export drawback receivable 预提费用 Provision for expenses存货 Inventories 预计负债 Accrued liabilities其中:原材料 Including:Raw materials 一年内到期的长期负债 Long term liabilities due within one year 产成品(库存商品) Finished goods 其他流动负债 Other current liabilities待摊费用 Prepaid and deferred expenses 流动负债合计 Total current liabilities待处理流动资产净损失 Unsettled G/L on current assets 长期借款 Long-term loans payable一年内到期的长期债权投资 Long-term debenture investment falling due in a yaear 应付债券 Bonds payable其他流动资产 Other current assets 长期应付款 long-term accounts payable流动资产合计 Total current assets 专项应付款 Special accounts payable长期投资: Long-term investment:其他长期负债 Other long-term liabilities其中:长期股权投资 Including long term equity investment 其中:特准储备资金 Including:Special reserve fund长期债权投资 Long term securities investment 长期负债合计 Total long term liabilities*合并价差 Incorporating price difference 递延税款贷项 Deferred taxation credit长期投资合计 Total long-term investment 负债合计 Total liabilities固定资产原价 Fixed assets-cost减:累计折旧 Less:Accumulated Dpreciation * 少数股东权益 Minority interests固定资产净值 Fixed assets-net value 实收资本(股本) Subscribed Capital减:固定资产减值准备 Less:Impairment of fixed assets 国家资本 National capital固定资产净额 Net value of fixed assets 集体资本 Collective capital固定资产清理 Disposal of fixed assets 法人资本 Legal person"s capital工程物资 Project material 其中:国有法人资本 Including:State-owned legal person"s capital在建工程 Construction in Progress 集体法人资本 Collective legal person"s capital待处理固定资产净损失 Unsettled G/L on fixed assets 个人资本 Personal capital固定资产合计 Total tangible assets 外商资本 Foreign businessmen"s capital无形资产 Intangible assets 资本公积 Capital surplus其中:土地使用权 Including and use rights 盈余公积 surplus reserve递延资产(长期待摊费用)Deferred assets 其中:法定盈余公积 Including:statutory surplus reserve其中:固定资产修理 Including:Fixed assets repair 公益金 public welfare fund固定资产改良支出 Improvement expenditure of fixed assets 补充流动资本 Supplermentary current capital其他长期资产 Other long term assets * 未确认的投资损失(以“-”号填列) Unaffirmed investment loss普通股 Ordinary shares 累计换算调整 Cumulative translation adjustments其中:特准储备物资 Among it:Specially approved reserving materials 留存收益 Retained earnings无形及其他资产合计 Total intangible assets and other assets 外币报表折算差额 Converted difference in Foreign Currency Statements递延税款借项 Deferred assets debits 所有者权益合计 Total shareholder"s equity资产总计 Total Assets 负债及所有者权益总计 Total Liabilities & Equity第十一章International Banking And Money Market国际银行与货币市场International Debt Crisis国际债务危机Debt-for-Equity Swaps 债权转股权LDC (less-developed countries) "欠发达国家"MNCs(Multinational Company) 跨国公司Equity investor权益投资者LDC central bank欠发达国家中央银行Export-oriented industries出口导向型产业High-technology industries 高科技产业CFO(Chief Financial Officer )首席财务官Global Government Bonds国际政府债券第十二章外国债券 foreign bonds欧洲债券 Eurobonds记名债券 registration bonds 不记名债券 bearer bonds 全球债券 global bonds 固定利率债券 straight fixed-rate bond 欧洲中期债券 Euro-medium-term notes 浮动利率票据 floating-rate notes、可转换债券 convertible bonds 附认股权证的债券 bonds with equity warrants双重货币债券 dual-currency bonds一级市场 primary market二级市场 secondary market卖出价 ask price 买入价 bid price主承销商 lead manager Yankee bonds 扬基债第十四章Swap Bank互换银行quality spread 质量Eurobond欧元债券currency swap货币互换Market completeness 完备市场Comparative advantage 比较优势Currency swap货币互换Counter parties交易双方Parent company母公司 Subsidiary子公司Producers 生产商 Financing needs 融资需求Swap market price 互换市场报价第十五章Portfolio risk diversification证券组合的风险分散 Sharpe Performance measure夏普绩效值Correlation coefficient相关系数Efficient set有效集Systematic risk系统风险 Risk-free rate无风险利率hedge fund对冲基金Risk —Return风险—收益第十六章Country risk 国家风险 Cross-border mergers and acquisitions 跨国并购Foreign direct investments(FDI)flows 对外直接投资流量Foreign direct investments (FDI)stocks 对外直接投资存量Greenfield investments绿地投资Intangible assets 无形资产Internalization Theory 内部化理论 Overseas Private Investment Corporation 海外私人投资公司Political risk 政治风险Product life-cycle theory 产品生命周期理论Synergisitic gains 利润增长值效应第十七章资本结构-capital structure 资本成本-cost of capital 加权平均资本成本-weighted average cost of capital 资本资产定价模型-capital asset pricing model,CAPM市场投资组合-market portfolio 系统风险-systematic risk 国际资产定价模型-international asset pricing model,IAPM 可国际交易资产-internationally tradable assets 可国际间交易资产-internationally notradable assets 完全分割资本市场-completely segmented capital market 国家的系统风险-country systematic risk 完全一体化的世界资本市场-fully integrated world capital markets 世界系统风险-world systematic risk部分一体化世界金融市场-partially integrated world financial markets定价的举出效应-pricing spillover effect 间接世界系统风险—indirect world systematic risk 市场双重定价现象-price-to-market,PTM phenomenon 净外国市场风险-pure foreign market risk投资组合-subsitution portfolio。

corporate governance的定义

corporate governance的定义

公司治理(Corporate Governance)是指一套机制和制度安排,用以确保公司管理层的行为符合股东和其他利益相关者的利益,同时促进公司的长期稳定发展。

这套机制涵盖了公司的内部管理和外部监管,以及公司与各利益相关者之间的关系管理。

首先,公司治理的核心目标是保护股东权益。

股东作为公司的所有者,享有公司的经营成果和承担风险。

因此,公司治理机制应确保管理层以股东利益最大化为目标,避免管理层滥用职权、损害股东利益的行为发生。

其次,公司治理还包括了对公司内部管理层的监督和制衡。

这通常通过设立董事会、监事会等内部机构来实现。

董事会负责制定公司的战略和政策,并对管理层进行监督;监事会则负责监督董事会的决策和管理层的执行情况,确保公司的运营符合法律法规和股东利益。

此外,公司治理还涉及到公司与各利益相关者之间的关系管理。

这些利益相关者包括员工、客户、供应商、债权人等,他们的利益与公司的发展密切相关。

因此,公司治理机制应确保公司在追求自身利益的同时,充分考虑并维护这些利益相关者的权益。

最后,公司治理还强调透明度和信息披露。

公司应及时、准确、全面地披露其财务状况、经营状况和风险信息,以便股东和其他利益相关者做出明智的决策。

总之,公司治理是一套复杂的机制和制度安排,旨在确保公司的管理层以股东和其

他利益相关者的利益为出发点,促进公司的长期稳定发展。

良好的公司治理结构有助于提高公司的竞争力和市场信誉,为公司的长期发展奠定坚实的基础。

欧盟绿皮书《Corporate governance in financial institutions and remuneration policies》

ENEUROPEAN COMMISSIONBrussels, 2.6.2010COM(2010) 284 finalGREEN PAPERCorporate governance in financial institutions and remuneration policies{COM(2010) 285 final}{COM(2010) 286 final}{SEC(2010) 669}GREEN PAPERCorporate governance in financial institutions and remuneration policies(Text with EEA relevance)1. INTRODUCTIONThe scale of the financial crisis triggered by the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers in autumn 2008 and linked to the inappropriate securitisation of US subprime mortgage debt led governments around the world to question the effective strength of financial institutions and the suitability of their regulatory and supervisory systems to deal with financial innovation in a globalised world. The massive injection of public funding in the US and Europe – up to 25% of GDP – was accompanied by a strong political will to learn the lessons of the financial crisis in all its dimensions to prevent such a situation happening again in the future.In its Communication of 4 March 20091, effectively a programme for reforming the regulatory and supervisory framework for financial markets based on the conclusions of the Larosière report2, the European Commission announced that it would (i) examine corporate governance rules and practice within financial institutions, particularly banks, in the light of the financial crisis, and (ii) where appropriate, make recommendations, or even propose regulatory measures, in order to remedy any weaknesses in the corporate governance system in this key sector of the economy. Strengthening corporate governance is at the heart of the Commission's programme of financial market reform and crisis prevention. Sustainable growth cannot exist without awareness and healthy management of risks within a company. As highlighted by the Larosière report, it is clear that boards of directors, like supervisory authorities, rarely comprehended either the nature or scale of the risks they were facing. In many cases, the shareholders did not properly perform their role as owners of the companies. Although corporate governance did not directly cause the crisis, the lack of effective control mechanisms contributed significantly to excessive risk-taking on the part of financial institutions. This general observation is all the more worrying because corporate governance has been relied upon as one of the ways of regulating business life. Consequently, there is a need to address the fundamental question of whether the existing corporate governance regime is deficient as far as financial institutions are concerned or whether it has rather been poorly implemented.In the financial services sector, corporate governance should take account of the interests of other stakeholders (depositors, savers, life insurance policy holders, etc), as well as the stability of the financial system, due to the systemic nature of many players. At the same time, it is important to avoid any moral hazard by not diminishing the responsibility of private stakeholders. It is therefore the responsibility of the board of directors, under the supervision 1COM (2009) 114 final.2Report of the High-Level Group on Financial Supervision in the EU published on 25 February 2009.Mr Jacque de Larosière was chairman of the group.of the shareholders, to set the tone and in particular to define the strategy, risk profile and appetite for risk of the institution it is governing.The options outlined in this Green Paper are likely to accompany and supplement the legal provisions implemented or planned for the purpose of strengthening the financial system, in particular in the context of the reform of the European supervisory architecture3, the Capital Requirements Directive (the 'CRD')4, the Solvency II Directive5 for insurance companies, reform of the UCITS system and the regulation of Alternative Investment Fund Managers. Corporate governance requirements should also take account of a financial institution's type (retail bank, investment bank) and size. The principles of sound corporate governance referred to in this Green Paper focus primarily on large financial institutions. These principles should be adapted so as to be applied effectively to smaller financial institutions.This Green Paper should be read in conjunction with the Commission Staff Working Paper (COM(2010) XYZ) 'Corporate governance in financial institutions: the lessons to be learnt from the current financial crisis and possible steps forward'. This document takes stock of the situation.It is also important to point out that, since its meeting in Washington on 15 November 2008, the G20 has endeavoured to improve, amongst other things, risk management and compensation practices within financial institutions6.Lastly, the Commission will soon launch a broader review on corporate governance within listed companies in general and, in particular, on the place and role of shareholders, the distribution of duties between shareholders and boards of directors with regard to supervising senior management teams, the composition of boards of directors, and corporate social responsibility.2. THE CONCEPT OF CORPORATE GOVERNANCE AND FINANCIAL INSTITUTIONSThe traditional definition of corporate governance refers to relations between a company's senior management, its board of directors, its shareholders and other stakeholders, such as employees and their representatives. It also determines the structure used to define a company's objectives, as well as the means of achieving them and of monitoring the results obtained7.3See the Commission proposals creating three European Supervisory Authorities and a European Systemic Risk Board.4Directive 2006/48/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 14 June 2006 relating to the taking up and pursuit of the business of credit institutions (recast), OJ L 177 of 30.6.2006 and Directive 2006/49/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 14 June 2006 on the capital adequacy of investment firms and credit institutions (recast), OJ L 177 of 30.6.2006.5Directive 2009/138/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 November 2009 on the taking-up and pursuit of the business of Insurance and Reinsurance (Solvency II) (recast) OJ L 335 of17.12.2009.6It was confirmed at the Pittsburgh Summit of 24 and 25 September 2009 that compensation practices would have to be reformed in order to maintain financial stability.7See, for example, the OECD's Principles of Corporate Governance, 2004, p. 11. The Green Paper focuses on this limited definition of corporate governance and does not deal with some other important aspects, such as separation of functions within a financial institution, internal controls and accounting independence.Due to the nature of their activities and interdependencies within the financial system, the bankruptcy of a financial institution, particularly a bank, can cause a domino effect, leading to the bankruptcy of other financial institutions. This can lead to an immediate contraction of credit and the start of an economic crisis due to lack of financing, as the recent financial crisis demonstrated. This systemic risk led governments to shore up the financial sector with public funding. As a result, taxpayers are inevitably stakeholders in the running of financial institutions, with the goal of financial stability and long-term economic growth. Furthermore, the interests of financial institutions' creditors (depositors, life insurance policy holders or beneficiaries of pension schemes and, to a certain extent, employees) are potentially at odds with those of their shareholders. Shareholders benefit from a rise in the share price and maximisation of profits in the short term and are potentially less interested in too low a level of risk. For their part, depositors and other creditors are focused only on a financial institution's ability to repay their deposits and other mature debts, and thus on its long-term viability. As a result, depositors can be expected to favour a very low level of risk8. Largely as a result of the particularities relating to the nature of their activities, most financial institutions are strictly regulated and supervised. For the same reasons, financial institutions' internal governance cannot be reduced to a simple problem of conflicts of interest between shareholders and the management. Consequently, the rules of corporate governance within financial institutions must be adapted to take account of the specific nature of these companies. In particular, the supervisory authorities, whose mission to maintain financial stability coincides with the interests of depositors and other creditors to control risk-taking by the financial sector, have an important role to play in shaping best practices for governance in financial institutions.Various legal instruments and recommendations at international and European level applicable to financial institutions and in particular banks, already take account of the particularities of financial institutions and the role of supervisory authorities9.However, the existing rules and recommendations are based first and foremost on supervisory considerations and focus on the existence of adequate internal control, risk management, audit and compliance structures within financial institutions. They did not prevent excessive risk-taking by financial institutions, as the recent financial crisis demonstrated.8See Peter O. Mülbert, Corporate Governance of Banks, European Business Organisation Law Review,12 August 2008, p.427.9Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, Enhancing corporate governance for banking organisations, September 1999. Revised in February 2006; OECD, Guidelines for insurers' governance, 2005; OECD, Revised guidelines for pension fund governance, July 2002; Directive 2004/39/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 21 April 2004 on markets in financial instruments amending Council Directives 85/611/EEC and 93/6/EEC and Directive 2000/12/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council and repealing Council Directive 93/22/EEC, OJ L 145 of 30.4.2004; Solvency II Directive;Capital Requirements Directive; Committee of European Banking Supervisors, Guidelines on the Application of the Supervisory Review Process under Pillar 2 (CP03 revised), 25 January 2006, /getdoc/00ec6db3-bb41-467c-acb9-8e271f617675/GL03.aspx; CEBS High Level Principles for Risk Management, 16 February 2010, /Publications/Standards-Guidelines/CEBS-High-Level-Principles-for-Risk-Management.aspx3. DEFICIENCIES AND WEAKNESSES IN CORPORATE GOVERNANCE WITHIN FINANCIALINSTITUTIONSThe Commission considers that an effective corporate governance system, achieved through control mechanisms and checks, should lead to the main stakeholders in financial institutions (boards of directors, shareholders, senior management, etc.) assuming a higher degree of responsibility. Conversely, the financial crisis and its serious economic and social consequences have led to a significant loss of confidence in financial institutions, particularly with regard to the following.3.1. The question of conflicts of interestThe questions raised by the issue of conflicts of interest and management of such conflicts are nothing new. Indeed, the issue arises in every organisation or company. Nonetheless, given the systemic risk, the volume of transactions, the diversity of financial services provided and the complex structure of large financial groups, the issue is particularly pressing in the case of financial institutions. Potential conflicts of interest can arise in a variety of situations (for example, exercising incompatible roles or activities, such as providing advice on investments while managing an investment fund or managing for one's own account, incompatibility of mandates held on behalf of different clients/financial institutions). This problem can also arise between a financial institution and its shareholders/investors, particularly where there is cross-shareholding or business links between an institutional investor (for example through the parent company) and a financial institution in which it is investing.At Community level, the MiFID10 is a step forward for transparency, devoting a specific section to certain aspects of this issue. However, the asymmetric information between investors and shareholders on the one hand, and the financial institution concerned on the other (an imbalance compounded by the ever-increasing complexity and diversity of the services provided by financial institutions), calls into question the effectiveness of market identification and supervision of various conflicts of interest involving financial institutions. Furthermore, as the CEBS, CEIOPS and CESR committees note in their joint report on internal governance11, there is a lack of consistency in the content and detail of the conflict of interest rules to which the various financial institutions are subject, depending on whether they need to apply the provisions of MiFID, the CRD, the UCITS Directive12 or Solvency 2. 3.2. The problem of effective implementation by financial institutions of corporategovernance principlesThe general consensus13 is that the existing principles of corporate governance, namely the OECD principles, the recommendations of the Basel Committee, and Community legislation14, already cover to a certain extent the problems highlighted by the financial crisis. In spite of this, the financial crisis revealed the lack of genuine effectiveness of corporate 10Directive 2004/39/EC on markets in financial instruments, (OJ L 145 of 30.4.2004).11'Cross-sectoral stock-take and analysis of internal governance requirements' by CESR, CEBS, CEIOPS, October 2009.12 Directive2009/65/EC.13See the OECD's public consultation 'Corporate governance and the financial crisis' of 18 March 2009 and in particular the section entitled 'Implementation gap'.14Directive 2006/46/EC obliges financial institutions listed on regulated markets to draw up a corporate governance code to which they are subject, and to indicate any parts of the code from which they have departed and the reasons for doing so.governance principles in the financial services sector, particularly with regard to banks. Several theories have been put forward to explain this situation:–the existing principles are too broad in scope and are not sufficiently precise. As a result, they gave financial institutions too much scope for interpretation. Furthermore, they proved difficult to put into practice, in most cases leading to a purely formal application(i.e., a box-ticking exercise), with no real qualitative assessment.–the lack of a clear allocation of roles and responsibilities with regard to implementing the principles, within both the financial institution and the supervisory authority.–the non-binding nature of corporate enterprise principles: the fact that there was no legal obligation to comply with recommendations by international organisations or the provisions of a corporate governance code, the problem of the neglect of corporate governance by supervisory authorities, the weakness of relevant checks, and the absence of deterrent penalties all contributed to the lack of effective implementation by financial institutions of corporate governance principles.3.3. Boards of directors15The financial crisis clearly shows that financial institutions' boards of directors did not fulfil their key role as a principal decision-making body. Consequently, boards of directors were unable to exercise effective control over senior management and to challenge the measures and strategic guidelines that were submitted to them for approval.The Commission considers that their failure to identify, understand and ultimately control the risks to which their financial institutions were exposed is at the heart of the origins of the crisis. Several reasons or factors contributed to this failure:–members of boards of directors, in particular non-executive directors, devoted neither sufficient resources nor time to the fulfilment of their duties. Furthermore, several studies have clearly demonstrated that, faced with a chief executive officer who is omnipresent and in some cases authoritarian, non-executive directors felt unable to raise objections to, or even question, the proposed guidelines or conclusions due to a lack of technical expertise and/or confidence.–members of boards of directors did not come from sufficiently diverse backgrounds. The Commission, like several national authorities, notes a lack of diversity and balance in terms of gender, social, cultural and educational background.–boards of directors, in particular the chairman, did not carry out a serious performance appraisal either of their individual members or of the board of directors as a whole.–boards of directors were unable or unwilling to ensure that the risk management framework and risk appetite of their financial institutions were appropriate.15The term 'board of directors' in this Green Paper essentially refers to the supervisory role of directors ina company which, in a dual structure, generally falls within the scope of the supervisory board. ThisGreen Paper does not prejudice the roles attributed to different company bodies under national legal systems.–boards of directors proved unable to recognise the systemic nature of certain risks and thus to provide sufficient information upstream to their supervisory authorities Furthermore, even where effective dialogue existed, corporate governance issues were rarely on the agenda.The Commission considers that these serious deficiencies and acts of misconduct raise important questions about the quality of appointment procedures. The basis for quality in a board of directors lies in its composition.management3.4. RiskRisk management is one of the key aspects of corporate governance, particularly in the case of financial institutions. Several large financial institutions no longer exist precisely because they neglected the basic rules of risk management and control. Financial institutions have too often failed to take a holistic approach to risk management. The main failures and shortcomings can be summarised as follows:– a lack of understanding of the risks on the part of those involved in the risk management chain and insufficient training for those employees responsible for distributing risk products16;– a lack of authority on the part of the risk management function. Financial institutions have not always granted their risk management function sufficient powers and authority to be able to curb the activities of risk-takers and traders;–lack of expertise or insufficiently wide-ranging experience in risk management. Too often, the expertise considered necessary for the risk management function was limited to those categories of risk considered priorities and did not cover the entire range of risks to be monitored;– a lack of real-time information on risks. To allow those involved to react quickly to changes in risk exposures, clear and correct information on risk should be available rapidly at all relevant levels of the financial institution. Unfortunately, the procedures for getting information to the appropriate level have not always functioned. Furthermore, it is crucial to upgrade IT tools for risk management, including in highly sophisticated financial institutions, as they are still too disparate to allow risks to be consolidated rapidly, while data are insufficiently consistent to allow the evolution of group exposures to be followed up effectively in real-time. This concerns not only the most complex financial products but all types of risk.The Commission considers that the deficiencies and shortcomings highlighted above are very worrying. They appear to indicate the absence of a healthy risk management culture at all levels of certain financial institutions. On this last point, the directors of financial institutions in particular are responsible, because in order to establish a healthy risk management culture at all levels, it is essential that directors are themselves exemplary in this respect.16See for example Renate Böhm and Hilla Lindhüber, Verkaufen, Druck und Provisionen - Probleme von Beschäftigten im Finanzdienstleistungsbereich Versicherungen Ergebnisse einer Arbeitsklima-Index-Befragung, Salzburg 2008.3.5. The role of shareholdersThe financial crisis has shown that confidence in the model of the shareholder-owner who contributes to the company's long-term viability has been severely shaken, to say the least. The growing importance of financial markets in the economy, due in particular to the multiplication of sources of financing/capital injections, has created new categories of shareholders. Such shareholders sometimes seem to show little interest in the long-term governance objectives of the businesses/financial institutions in which they invest and may be responsible for encouraging excessive risk-taking in view of their relatively short, or even very short (quarterly or half-yearly) investment horizons17. In this respect, the sought-after alignment of directors' interests with those of these new categories of shareholder has amplified risk-taking and, in many cases, contributed to excessive remuneration for directors, based on the short-term share value of the company/financial institution as the only performance criterion18. Several factors can help to explain the disinterest or passivity of shareholders with regard to their financial institutions:–certain profitability models, based on possession of portfolios of different shares, lead to the abstraction, or even disappearance, of the concept of ownership normally associated with holding shares.–the costs which institutional investors would face if they wanted to actively engage in governance of the financial institution can dissuade them, particularly if their participation is minimal.–conflicts of interest (see above).–the lack of effective rights allowing shareholders to exercise control (such as, for example, the lack of voting rights on director remuneration in certain jurisdictions), the maintenance of certain obstacles to the exercise of cross-border voting rights, uncertainty over certain legal concepts (for example that of 'acting in concert') and financial institutions' disclosure to shareholders of information which is too complicated and unreadable, in particular with regard to risk, could all play a part, to varying degrees, in dissuading investors from playing an active role in the financial institutions in which they have invested.The Commission is aware that this problem does not affect only financial institutions. More generally, it raises questions about the effectiveness of corporate governance rules based on the presumption of effective control by shareholders. As a result of this situation, the Commission will launch a broader review covering listed companies in general.3.6. The role of supervisory authoritiesGenerally speaking, the recent financial crisis revealed the limits of the existing supervision system: in spite of the availability of certain tools enabling them to intervene in the internal governance of financial institutions19, not all supervisory authorities, either at national or 17See article by Rakesh Khurana and Andy Zelleke, Washington Post, 8 February 2009.18See Gaspar, Massa, Matos (2005), Shareholder Investment Horizon and the Market for Corporate Control, Journal of Financial Economics, vol. 76.19For example, Basel II.European level, were able to carry out effective supervision in an environment of financial innovation and rapid change in the business model of financial institutions20. Furthermore, the supervisory authorities also failed to establish best practices for corporate governance in financial institutions. In many cases, supervisory authorities did not ensure that financial institutions' risk management systems and internal organisation were adapted to changes in their business model and financial innovation. Supervisory authorities also sometimes failed to adequately enforce strict eligibility criteria for members of boards of directors of financial institutions ('fit and proper test')21.Generally speaking, problems linked to the governance of supervisory authorities themselves, particularly the means of combating the risk of regulatory capture or the lack of resources, have never been sufficiently discussed. Moreover, it is becoming increasingly clear that the territorial and substantive competencies of supervisory authorities no longer correspond to the geographical and sectoral spread of financial institutions' activities. This complicates risk management for financial institutions and makes it more difficult for them to comply with regulatory standards, as well as presenting a major challenge for cooperation between supervisory authorities.3.7. The role of auditorsAuditors play a key role in financial institutions' corporate governance systems, as they provide assurance to the market that the financial statements prepared by those financial institutions present a true and fair view. However, conflicts of interest could arise as audit firms are remunerated by the same companies who mandate them to audit their financial accounts.At present, there is no information to confirm that the requirement, pursuant to Directive 2006/48/EC, for auditors of financial institutions to alert the competent authorities wherever they become aware of certain facts which are liable to have a serious effect on the financial situation of an institution, has been effectively enforced in practice.4. I NITIAL RESPONSESIn the context of its Communication of 4 March 2009 and measures taken to boost the European economy, the Commission has undertaken to address issues related to remuneration. The Commission has launched the international debate on abusive remuneration practices and was leading the implementation at European level of FSB and G-20 principles on sound compensation practices. Leaving aside the issue of whether or not certain levels of remuneration are appropriate, the Commission started from two premises:–since the end of the 1980s, the substantial increase in the variable component of listed company directors' salaries raises questions about the methods and content of performance evaluations for company directors. In this respect, the Commission made an initial response at the end of 2004 by adopting a recommendation aimed at strengthening obligations to publish director remuneration policies and individual salaries, and calling on 20On the failings of supervisory authorities in general, see the 'de Larosière' Report, footnote 1.21See, for example, OECD, Corporate Governance and the Financial Crisis, Recommendations, November 2009, p.27.the Member States to establish a vote (mandatory or optional) on such director remuneration. For a variety of reasons linked, amongst other things, to the lack of shareholder activism, the explosion of the variable component and, in particular, the multiplication of profit-sharing plans granting shares or stock options, the Commission considered it necessary to adopt a new recommendation on 30 April 200922. The aim of this recommendation is to strengthen governance of directors' remuneration, proposing several principles for director remuneration structures in order to better link remuneration to long-term performance.–remuneration policies in the financial sector, based on short-term profits without taking into account the corresponding risks, contributed to the financial crisis. For this reason, the Commission adopted another recommendation on remuneration in the financial services sector on 30 April 200923. The aim was to align remuneration policies in the financial services with healthy risk management and financial institutions' long-term viability. Taking stock one year after the adoption of the two abovementioned recommendations, and in spite of a favourable climate for tough action on the part of the Member States, the Commission finds a mixed overall picture of the situation in the Member States24.Although there were strong legislative moves in several Member States to achieve greater transparency in remuneration for listed company directors and to empower shareholders in this respect, it was also noted that only 10 Member States have applied the majority of Commission recommendations. A large number of Member States have still not adopted the relevant measures. Furthermore, where the recommendation led to measures at national level, the Commission noted great diversity in the content and requirements of these rules, particularly on sensitive issues such as remuneration structure and severance packages. The Commission is also concerned about remuneration policies in the financial services. Only 16 Member States have applied the Commission Recommendation in full or in part while five are still in the process of doing so. Six Member States have at present taken no action on this front and do not intend to do so in the near future. Furthermore, the intensity (particularly requirements relating to remuneration structure) and scope of application of the measures taken vary depending on the Member State. Thus only seven Member States have extended implementation of the principles of the recommendation to the entire financial sector, as the Commission called on them to do.5. OPTIONS FOR THE FUTUREThe Commission considers that, while taking into account the need to preserve the competitiveness of the European financial industry, the deficiencies listed in Chapter 3 call for concrete solutions to improve corporate governance practices in financial institutions. This chapter considers a variety of ways to respond to these deficiencies and tries to strike the right balance between the need for improved corporate governance of financial institutions and the necessity of allowing these institutions to contribute to economic recovery by providing credit to businesses and households. The Commission invites all interested parties to express their 22 Recommendation2009/385/EC.23 Recommendation2009/384/EC.24For a detailed examination of the measures taken by the Member States, see the two Commission reports on the application by the Member States of Recommendation 2009/384/EC and Recommendation 3009/385/EC.。

corporate governance的定义

corporate governance的定义

企业治理(corporate governance)是指确保企业有效运作、增加经营者责任和透明度、以及保护股东和利益相关者利益的制度和实践。

它涉及制定和执行决策的框架、监督机制、行为准则和权力分配。

企业治理旨在建立一种透明、负责任和可持续的企业运营模式,以维护股东权益、保护利益相关者利益,并提高企业的管理效能和长期价值。

企业治理关注以下方面:

1.权力和责任:企业治理规定了企业管理者和董事会成员的

权力和责任,确保他们行使权力时不滥用,负责任地履行

职责。

2.企业结构:企业治理规定了企业的结构和组织形式,包括

董事会的角色和职责、管理层和股东的权利与责任、以及

各个利益相关者的参与方式。

3.信息披露与透明度:企业治理要求企业向股东和利益相关

者提供准确、及时和全面的信息,确保信息的公平与透明,减少对关键信息的隐藏和不完整披露。

4.决策和风险管理:企业治理规定了决策过程和风险管理机

制,确保决策过程合理、合法,并包括适当的风险评估和

管理机制。

5.激励和报酬:企业治理制定了激励和报酬机制,以确保管

理层和董事会成员的行为与企业利益一致,并与企业绩效

和长期目标相匹配。

企业治理的实践和规范因国家、行业和企业而异,可以通过法律、制度、监管机构和自律准则来实施和监督。

良好的企业治理有助于提高企业的稳定性、信誉和长期价值,为股东、利益相关者和整个经济体创造持续的利益。

股权激励外文文献【中英对照】