恩波.翔高辅导讲义(普心12)

普心第十二章人格

第十二章人格一、人格的概述一)人格的含义(人格的结构)二)人格的特征(4)二、人格理论一)人格特质理论1、奥尔波特的特质理论(2)2、卡特尔的人格特质理论(4)3、现代特质理论1,三因素模型(艾森克)2,五因素模型(塔佩斯)3,七因素模型(特里跟)二)人格类型理论1、单一类型理论(弗兰克法利)2、对立类型理论1,A-B型人格(塔斯曼和罗斯曼)2,内外型人格(荣格)3、多元类型理论(斯普兰格)三)精神分析人格理论四)人本主义人格理论1、马斯洛的需要层次2、罗杰斯的人格理论三、气质一)气质的含义二)气质的类型和理论1、体液说2、体型说3、高级神经活动类型说四、性格一)性格的含义二)性格的特征(3)三)性格与气质的关系(2)四)认知风格1、场独立-场依存2、冲动-沉思3、同时性-继时性五、影响人格形成和发展的因素(7)第十二章人格一、人格的概述一)人格的含义人格就是构成一个人的思维,情感和行为当中所特有的统合模式,这个特有模式包含了一个人区别与另一个人所特有的稳定和统一的心理品质;外在的人格品质是可观察到的自我,是人格的面具;在内在的人格特质是个体不展示给他人的一面;是真实的自我;人格的结构二)人格的特征1、独特性;一个人的人格是在遗传,成熟和环境,教育等先后天的交互作用下形成的,不同的遗传,生存及教育环境,形成了各自独特的心理特点;2、稳定性;3、综合性;人格的综合性是心理健康的重要标志;否则,会出现适应性困难,甚至是人格分裂;4、功能性;人格决定一个人的生活方式,甚至决定一个人命运的;因而是人生成败的根源之一;当人面对挫折和失败时,坚强者奋发拼搏,怯弱者会一蹶不振;这就是人格功能性的体现;二、人格理论一)人格的特质理论1、奥尔波特的特质理论1937奥尔波特将人格分为个人特质和共同特质;个人特质是个人所具有的独特的特质;共同特质是大多数人或是一个群体所具有的相同或类似的特质;共同特质可分为首要特质,中心特质和次要特质;首要特质是一个人的最典型,最重要的特质;中心特质是组成个体独特性特质的几个重要的特质;次要特质是一些不重要的特质;2、卡特尔的人格特质理论卡特尔受到化学周期表的影响,运用因素分析的方式将人格分成了四层特质;一个别特质和共同特质;二根源特质和表面特质;三体质特质和环境特质;四动力特质,能力特质和气质特质;1,个别特质和共同特质2,根源特质和表面特质表面特质是从人的外表本身可以观察到的特质;根源特质是以相同原因为基础的相互联系的行为特质;表面特质和根源特质可以使个别特质,也可以是共同特质;1949卡特尔提出了卡特尔16种人格特征(根源特质);3,体质特质和环境特质体质特质是有先天的因素决定的,如兴奋性,情绪稳定性;而环境则是由后天的环境因素决定的,如焦虑,有恒性;卡特尔提出了多元抽象变异分析MA V A;4,动力特质,能力特质和气质特质动力特质是具有动力性质的特质,是个体指向一个目标,包括生理驱力,态度和情操;能力特质是表现在直觉和运动方面的特质;包括晶体智力和流体智力;气质特质是决定一个人的情绪反应与强度的人格特质;3、现代特质理论1,三因素模型是由美国心理学家艾森克运用因素分析法提出的;他将人格分成三个成分;外倾性,神经质和精神质;外倾性就是指人格内外倾的差异;神经质表现为情绪的稳定性方面;精神质表现在孤独,冷傲,敌视,怪异等负面的人格特质上;他编制了艾森克人格问卷EPQ;2,五因素模型塔佩斯等用词汇学的方式对卡特尔人格特质进行分析时将人格的特征分为五个方面;这五个因素是;1开放性;想象,审美,情感丰富,求异,创造,智能等;2责任心;胜任,公正,尽职,成就,自律,谨慎,克制等;3外倾性;热情;社交,果断,活跃,冒险,乐观等;4宜人性;信任,直率,利他,依从,谦虚,移情等;5神经质;焦虑,敌对,自我意识,冲动,脆弱等;1989年麦克雷和可塔斯编制了大五因素人格量表;3,七因素模型是由特里跟提出的;根据不同的选词原则,获得了七种因素;正,负效价;正,负情绪;宜人性,可靠性和因袭性;二)人格的类型理论产生于20世纪30-40年代的德国;1、单一类型理论人格类型是由一群人身上具有的一种人格特征来确定的;是由美国心理学家弗兰克-法利提出的T类型人格;法利认为T型人格是一种好冒险爱刺激的人格特征;根据好冒险的特征可分为;T+型的人格和T-型的人格;T+型的人格是健康积极,创造性方向;如赛车,探险等;T-型的人格则是具有破坏性的;如酗酒,吸毒,暴力等;在T+型的人格中还分为体质T+人格和智力T+人格,体质T+人格就是通过身体运动来实现追求满足好奇的动机;如极限运动员等;智力T+型人格就是通过智力活动来满足好冒险的行为;如科学家;2、对立类型理论1,A-B型人格是由塔斯曼和罗斯曼提出的A-B型人格;A型人格主要是性格急躁,缺乏耐性,成就欲高,有吃苦的精神,工作投入,做事认真负责,时间紧迫感,富有竞争意识,外向,动作敏捷,说话快,生活处于紧张状态等,这种人办事匆忙,社会适应性差,属于一种不安定性的人格;易患冠心病B型的人格属于一种性情温和,举止得当,对工作和生活满足感强,喜欢慢节奏的生活,可以胜任耐心和谨慎的思考工作;2,内-外型人格是由荣格将心理倾向分成了内倾性和外倾性;内倾性是指把兴趣和关注点指向个体;外倾性是把兴趣和关注点指向外部客体;内向型的人格的特点主要是自我剖析,做事谨慎,深思熟虑,疑虑困惑,交往面窄,有时会有适应性差的特点;外向型人格的特点主要是,注重外部世界,情感外露,热情,当机立断,独立自主,行动敏捷,有时轻率;荣格认为人的心理活动应该分为思维,感情,感觉和直觉四种基本功能;依据人的倾向性可将人格分成八种;外向思维型,外向感情型,外向感觉型,外向直觉型;内向思维型,内向感情型,内向感觉型,内向直觉型;3,多元类型理论这种理论认为人格是由不同质的人格特性成分组成的;德国心理学家斯普兰格依据人类社会文化形态分成了六种性格类型;1经济型,2审美型,3权力型,4社交型,5宗教型,6理论型;三)精神分析人格理论弗洛伊德将人格分成本我,自我和超我;他们具有各自的特点,功能和结构;本我是人格的基础,是人的冲动和欲望的来源,为自我和超我提供能量;本我的机能是被压抑的欲望和冲动的满足;这个过程遵循快乐法则;自我是为了实现本我和现实的接触而产生的,本我不能接触现实,这就需要本我来实现;自我的机能是为了更好的了解世界和现实,是对环境的反应合理化;自我人格中是控制行为,选择符合现实状况的行为的部分;自我一方面要接受现实的要求,一方面又要使本我的欲望和冲动和现实情境相一致;自我是从本我中分化出来的;是在本我和外界世界之间媒介的基础;遵循现实原则;超我可以分成道德的自我和理想的自我,理想的自我是超我当中积极的部分,而道德的自我是超我中惩罚的部分;超我接受社会中道德的约束;超我是禁止本能的冲动和欲望;又要实现自我从现实想道德的方面转化;弗洛伊德认为健康的状态就是自我成为人格的主体;一边使欲望适应于超我和现实的要求;一边又满足现实的这种欲望;四)人本主义人格理论人本主义不同于其他学派的特点是强调人的正面的本质和价值,并非集中研究人的问题行为,并强调人的成长和发展,即自我实现;1、马斯洛的需要层次在心理学上,马斯洛的需要层次理论是解释人的的重要理论,也是解释动机的重要理论;自我实现是马斯洛观点的核心;定义为不断实现人本身的潜能,定义为更充分的认识承认了人的内在天性,使人内部不断实现统一,整合和协同的过程;也就是说,个体之所以存在,之所以有生命意义,就是为了自我实现;2、罗杰斯的人格理论罗杰斯提倡人格的自我理论;这种理论受到新精神分析,场论和现象论的影响;罗杰斯强调人的本身和主观经验的重要性,所以又叫族人本论;罗杰斯在大量的临床试验中,逐渐接受了自我概念所以也叫做自我理论;罗杰斯认为,随着儿童和外界更为广泛的相互作用,儿童开始意识到他是谁和她可能是谁的表象;即自我观念;在罗杰斯看来;自我的发展以及能否形成健康的自我,取决于在儿童期是否得到爱抚;在自我的形成时期,儿童需要爱的哺育,这就是积极性的尊重;儿童是否能达到一种健康的人格,完全取决于儿童的积极性尊重是否能得到满足;有机体的一切经验都是把现实去想作为参照系来评估的;他将这种经验的评估方式叫做机体估价过程;罗杰斯认为,一个健康的人格就像一个婴儿一样他是按自己的估价过程而不是价值条件拉生活的;这种忠实于自己的生活方式是完善的生活,标志着一个纯洁的自我和真正的善;他认为一个健康的人格包含五个方面;开放性的经验;机体估价过程,无条件的自我尊重,人际关系,和睦相处;三、气质一)气质的含义气质是人心理活动的强度,速度,灵活性和指向性上的一种稳定的心理特征;气质是人的心理动力的特征;它使人的人格感染上了独特的色彩;气质是与生俱来的,比起能力和性格;气质很难改变,具有稳定性;有时可以稍微改变;气质没有好坏之分;气质能给人格染上个性的色彩,但不能赋予社会的价值;也不具有社会道德的意义;气质也不决定人的成就,但可以说不同气质的人适合不同领域的工作;二)气质的类型与理论1、体液说;气质学说最先起源于希波克拉底的体液说,他将人分成四种不同类型的人;胆汁质,多血质,粘液质和抑郁质;1,胆汁质;情绪体验强烈,爆发迅猛,平息迅速,思维灵活但粗枝大叶,精力旺盛,争强好胜,勇敢果断,为人热情正直,朴实真诚,表里如一,行动敏捷,生气勃勃,刚毅顽强,做事欠思量,鲁莽冒失,刚愎自用;2,多血质;情感丰富,外露但不稳定,思维敏捷单不求甚解,活泼好动,热情大方,善于交往但交情浅薄,行动敏捷,适应力强,弱点就在于缺乏耐心和毅力,稳定性差,见异思迁;3,粘液质;情绪平稳,表情平淡,思维灵活性较差但考虑问题细致周到,安静沉稳,踏踏实实,沉默寡言,喜欢沉思,自制力强,内刚外柔,交往适度,交情深厚,但这种人主动性差,缺乏生气,行动缓慢;4,抑郁质;情绪体验深刻,细腻持久,情绪抑郁,多愁善感,思维敏锐,想象丰富,不善交际,孤僻离群,踏实稳重,自制力强;但行动缓慢,软弱胆小,优柔寡断;2、体型说德国心理学家克瑞奇米尔根据对临床精神病人的观察,认为身体的结构与气质的特点有关;肥胖型的人易患躁狂症和抑郁症;瘦长型的人易患精神分裂;3、高级神经活动类型说巴甫洛夫用高级神经活动类型说来解释气质的生理基础;巴甫洛夫根据高级神经活动的基本特性,即兴奋性和抑制过程的强度,平衡性和灵活性;划分四种基本的神经活动类型;四种气质类型和高级神经活动的类型的关系;强,不平衡——冲动型——胆汁质强,平衡,灵活——活泼型——多血质强,平衡,不灵活——安静型——粘液质弱——抑制型——抑郁质整合理论四、性格一)性格的含义性格就是人对现实的稳定的态度和习惯化了的行为方式;性格是一种和社会相关的人格特征;在性格中包含了许多社会道德的意义;性格主要体现在人们对自己,对他人,对事物的态度和所采取的行为方式上;所谓态度就是人们对社会,对自己和对他人的一种心理倾向性;它包括评价,好恶和趋避等方面;性格表现了一个人的道德品质,受人的人生观,价值观,世界观等影响;是在后天环境中逐渐形成的;是人格中最核心的人格差异;性格的好坏代表了一个人的道德风貌;性格是在社会生活中逐渐形成的,同时受个体的生物学因素的影响;罗和富尔顿研究发现,额叶受损,性格会明显发生变化;二)性格的特征1、各种性格特这个之间有内在的联系;2、各种性格特征在不同场合有不同的组合;3、各种性格特征有稳定性和可塑性;三)气质和性格的关系气质和性格之间有密切的联系;一气质和性格之间相互影响,气质影响性格的外部表现,是性格带有独特的色个性色彩;性格对气质也有深远的影响,它可以掩盖或者改造气质;二同一气质的人可以形成不同性格特征;不同气质类型的人也可以形成相同的性格特征;四)认知风格认知风格就是人们比较偏爱的信息加工方式;也叫认知方式;通俗的说就是在从事认知活动时所表现出来的特点;1、场独立-场依存场独立就是人在信息加工是对人的内在参考依赖性较大;他们的心理分化水平较高;在加工是主要依赖于人的内在参考因素,与人交往时,不够细心,也不能体察入微;场依存就是在信息加工时人对外界的参考有加大的依赖性;其心理分化水平较低;在处理问题是依赖于场,能够考虑他人的感受;场独立和场依存没有好坏之分,场独立的人具有较强的认知重构能力;在人认知占优势;而场依存的人的社会技巧高,在人际交往时占优势;2、冲动型-沉思型卡跟将认知风格分成两种;冲动型和沉思型;二者的差异主要表现在考虑问题的速度上;冲动型;反应速度快,但准确性差,这种认知风格的人容易急于求成,不能全面分析问题的各种可能性;多适用整体的信息加工策略;沉思型;考虑速度慢,但准确性高;这种认知风格的人把问题考虑周全之后再作反应,考虑到问题的各个方面;重视的是解决问题的质量,而不是速度;这种认知风格多采用细节性的信息加工策略;3、同时性-继时性达斯根据脑功能的研究,区分了两种认知风格,同时性和继时性;他们认为左脑半球占优势的人表现出继时性的加工风格;而右半球占优势的人表现出同时性加工风格;继时性加工风格是指人们在解决问题的时候;能一步一步的分析问题,每一个步骤只考虑一个假设或是属性,提出的假设在时间上有明显的先后顺序;如言语操作和记忆都属于继时性加工风格;女性擅长于继时性加工;同时性加工风格是指人们在解决问题的时候;一次会考虑形成多个假设,采用宽视野的方式,并兼顾到问题的所有可能性;这种加工方式是发散的;如数学能力,空间问题操作都依赖于同时性的加工;一般来说;男性在同时性加工上占优势;五、影响人格形成和发展的因素一)生物遗传因素1、遗传是人格形成不可缺少的因素;2、遗传因素对人格的作用随着人格因素的不同而不同;3、人格的发展受遗传和环境的相互租用的影响;二)社会文化因素一个人所处的特定社会文化度人格的形成有很重要的作用,社会文化塑造了社会成员的人格特征,是社会成员朝着相似的方向发展;不同社会文化的民族具有不同的民族特征;是社会文化对人格塑造得很好体现;三)家庭环境因素家庭对一个人仍的形成和发展有着重要的作用;家庭对人格的影响主要体现在父母对子女的教育方式上;家庭教养方式有三种;1权威型;2民主型;3放纵型;四)早期的儿童经验早期的童年经验对人格的影响受到心理学家的重视;童年的不幸会影响人一生的发展,幸福的童年有利于人格健康的发展;但是童年经验不单独起作用,而是和其他因素共同决定着人格的形成和发展;五)学校教育因素学校是一种有目的,有计划的向学生施加压力的教育场所,教师对学生具有指导定向的作用学校对人格的形成和发展是不容忽视的,学校是人格社会化的主要场所;教师对学生具有导向的作用;而同伴具有弃恶扬善的作用;六)自然物理因素自然物理环境包括生态环境,气候条件,空间拥挤程度对人格的形成发展有影响;但是自然环境对人格不起决定作用,而且还受主观因素的影响;自我调控系统是人各种的调控系统;外界的环境通过自我调控系统才能起作用;七)自我调控因素人格的自我调控系统是人格发展的内在因素;人格调控系统是以自我意识为核心的;自我意识是对自身和自己同客观世界的关系的意识;具有自我认识,自我体验好自我控制三个子系统;人格测验练习题1、性格的结构特性有,可塑性,稳定性,完整性和复杂性;2、性格的意志特征体现在果断性上;3、早期的亲子关系确定了行为的模式,塑造出一切日后的行为;这句话与精神分析学派观点符合;4、场独立性的人与场依存性的人相比在信息加工时;根据内在的标准加工信息,认知重建能力高;。

叶奕乾版《普心》知识点归纳总结

1.1心理学是研究人的心理现象的科学,具体来说是研究人的行为和心理活动规律的科学。

1.2人的心理过程分为认识过程(感觉、知觉、记忆、思维和想象等)、情绪情感过程(喜怒哀乐爱憎惧)和意志过程三个方面。

1.3个性是指一个人的整体心理面貌,是个人心理活动稳定的心理倾向和心理特征的总和。

个性主要包括个性倾向性和个性心理特征两个方面。

3.1注意是指心理活动或意识对一定对象的指向和集中无注意注意(不随意注意):指事先没有预定目的、也不需要意志努力的注意。

有意注意(随意注意):指有预定目的、需要一定意志努力的注意。

有意后注意(随意后注意):由预定目的,但不需要一致努力的注意.注意的稳定性是指对同一对象或者同一活动上注意所能持续的时间注意的广度:也叫注意的范围,是指在同一时间内能清楚地把握对象的数量。

注意的转移:根据新的任务,主动的把注意从一个对象转移到另一个对象或由一种活动转移到另一种活动现象。

5.1、感觉是人脑对直接作用于感觉器官的客观事物的个别属性的反映5.2、绝对感觉阈限:是指刚刚能引起机体感觉的最小刺激强度。

(上绝对阈限和下绝对阈限5.3、差别阈限:刚刚能引起差别感觉的两个同类刺激物刺之间最小差异量5.4、绝对感受性:人的感官感觉察这种微弱刺激的能力。

绝对感觉阈限和绝对感受性成反比!5.5、差别感受性:对最小差异量的感觉能力。

差别感受性与差别阈限在数值上也成反比例!5.6、视觉是个体借助眼睛辨别外界物体明暗、颜色和形状等特性的感觉,是人和动物最复杂、最重要的感觉,在人的各种感觉中起主导作用,是人类获得信息的主要通道。

5.7、听觉:人通过听觉器官对外界声音刺激的反映,是仅次于视觉的重要感觉。

5.8、触压觉:即触觉和压觉。

刺激物接触到皮肤表面时的感觉为触觉。

当刺激加强,使皮肤引起明显变形,就引起压觉。

5.9、温度觉包括冷绝和温觉。

低于皮肤温度即生理零度的温度刺激作用于皮肤即产生冷绝,高于生理零度的温度刺激作用于皮肤即产生温觉。

1.普心各章知识点 (1)修改版

第一章结论1、什么是心理学?心理学是研究心理现象的科学。

2、人的心理现象有哪些?传统的二分法:就是把个体心理分作心理过程和个性心理两个大的方面。

心理过程又包括认识过程、情感过程和意志过程个性心理包括个性倾向性和个性心理特征。

个性倾向性需要、动机、兴趣、世界观个性心理特征:气质、性格、能力3、怎样理解人的心理的实质?(1)脑是心理的器官,心理是脑的机能。

(2)心理是客观现实的主观能动的反映。

客观现实是心理生活的内容与源泉。

心理对客观现实的反映具有主观能动性。

(3)心理是有实践活动中产生和发展人的心理的实质:人的心理是人在实践中通过人脑对客观事物的主观能动的反映。

4、科学心理学诞生的标志是什么?1879年冯特在莱比锡大学创立了世所公认的第一个心理实验室。

5、西方心理学的主要派别?(含代表人物与主要观点)(1)构造主义奠基人:冯特著名代表人物:铁钦纳基本观点:第一、心理学的研究对象是意识经验。

而人的意识经验都是由感觉、意象和感情三个基本元素构成。

(感觉是知觉的基本元素;意象是观念的元素;感情是情绪的元素)第二、坚持心理学是一门纯科学,它的基本任务是理解正常成年人的一般心理规律,因而不重视心理学的应用,反对把心理学看做是一门应用科学。

第三、心理学研究的基本方法是实验内省法。

(2)机能主义创始人:詹姆士主要观点:第一、也主张心理学的研究对象是意识。

但它反对把意识看作是个别心理元素的集合(即反对心理的元素分析),而是一种川流不息的状态或过程。

即意识流。

第二、反对把心理学看成是一门纯科学,而注重心理学的应用(功能)。

第三、强调心理学研究的基本方法是内省法。

(3)行为主义创始人:华生主要观点:第一、反对研究意识,主张心理学研究行为。

第二、反对内省,主张用实验方法。

(4)格式塔心理学主要代表人:韦特海默、苛勒、科夫卡(又译为:考夫卡)主要观点:第一:大力强调整体组织,坚决反对元素分析。

第二:强调心理学的研究对象主要是直接经验。

爱他教育:南京师范大学新闻学传播学考研资料历年真题参考书目

2014 年南京师范大学新闻传播学专业课精品辅导资料1、《新闻学概论》学习笔记《新闻学概论》章节知识点汇总及答案详解2、《传播学教程》学习笔记《传播学教程》章节知识点汇总及答案详解3、《中国新闻史》学习笔记《中国新闻史》章节知识点汇总及答案详解4、《外国新闻史》学习笔记《外国新闻史》章节知识点汇总及答案详解5、《中国广播电视通史》学习辅导与重点归纳6、近年新闻热点、网络事件汇总及深度解析7、新闻传播学历年真题及答案解析(2006-2011)新闻史论2000,2002-2005年新闻综合知识2002-2005年传播史论2003-2005年传播实务2002-2005年8、2012独家更新资料优秀新闻传播学考研精品套餐笔记2012 年独家更新资料,南京师范大学新闻学传播学专业考研精品笔记套餐(165页):资料总共分为两部分,第一部分:内部信息,包括新闻传播学院新闻传播学专业介绍,新闻传播学专业课导师信息,联系方式,我们提供导师邮箱,方便同学联系导师,师兄考研的时候,也是给自己的导师发过邮件,在考研过程中就给自己想考的导师发过邮件,在考研的过程中得到了导师的悉心教导。

学长认为,电子邮件是联系导师的最理想方式。

大家要坚持给导师发邮件,不能问完问题,就间断了。

斤三年来新闻学传播学的考研招生人数和参考书目变化情况,近三年新闻传播学专业课复试上线人数,近三年新闻传播学保送名单,近三年南师大新闻传播复试线,已经考上的经验,第二部分为考研精品笔记,主要是按照每一章每一节的知识点和考点进行总结,考上的研究生学长已经将考点在后面注明,比如某个考点是名词解释,后面就有表明名词解释考点,第二部分是初试五本参考书的经典笔记。

9、独家辅导班讲义(温馨提示:我校没有任何官方专业课辅导班,本辅导班为恩波*翔高针对南师大新闻传播考研开办)1、新闻学概论国庆辅导班讲义2、传播学教程国庆辅导班讲义3、中国新闻史国庆辅导班讲义4、外国新闻传播史国庆辅导班讲义5、中国广播电视通史国庆辅导班讲义10、中国新闻史笔记针对中国新闻史的考试特点,以及繁琐难记忆的特征,笔记采用词条体和专题体相结合的方式,使得考点集中、全面、好查、易记,全方位应对考试中相关的名词解释和简单题。

普心第十三章重点

一、知识点归纳1.什么是学习?学习是个体在一定情景下由于反复地经验而产生的行为或行为潜能的比较持久的变化。

三个特点:1)学习是以行为或行为潜能的改变为标志的。

(行为的改变有时是外显的、外在的,有时是隐性的在的)2)行为的变化是经验引起的(成熟、疾病、疲劳引起的变化不叫学习)。

3)学习引起的行为变化是相对持久的。

2.学习的联结理论学习的联结理论强调学习就是在刺激与反应之间建立联结的过程,因此联结理论又可称为“刺激-反应”理论。

其代表人物主要有巴甫洛夫、桑代克与斯金纳。

(一)经典条件作用1)无条件反射:(unconditioned reflex):先天遗传获得,食物、防御、性三类。

2)条件反射(conditioned reflex):后天习得,具有概括、灵活的性质,能随环境变化而变化3)经典性条件反射的实质是(无条件)刺激与(中性)刺激之间的联结,又称S-S学习。

其提出者是俄国著名生理学家巴甫洛夫。

(二)经典性条件反射的规律1)习得:同时性条件、延迟性条件、痕迹条件作用延迟性条件下最易获得。

2)消退和恢复3)泛化与分化4)二级条件作用(三)操作性条件反射操作性条件反射的形成:对行为结果的学习1)桑代克的尝试-错误学习(trial and error)猫—迷笼实验2)斯金纳的操作性条件作用应答性条件反射:刺激情景引发反应操作性条件反射:不是刺激情景引发的,是有机体的自发行为。

强化物:凡是使反应概率增加,或维持某种反应水平的任何刺激。

正强化:环境中某种刺激增加而行为反应出现的概率也增加时,这种刺激就是正强化物。

负强化:当环境中某种刺激减少而行为反应出现的概率增加时,这种刺激就是负强化物。

(四)操作性条件反射的规律1)连续强化2)间隔强化(部分强化):部分强化习得的反应不易消退3)比率式间隔强化:固定比率强化:推销员的报酬标准i.变化比率强化:赌场里获胜的机会4)时间式间隔强化:固定时间强化:按月支付薪水i.变化时间强化:临时测验5)有针对性强化,签约长(三年)的棒球手成绩不如签约短(一年)的稳定二、名词解释1,学习-是个体在一定情景下由于反复的经验而产生的行为或行为潜能的比较持久的变化。

recent initiaatives by the basel-based r_qt0806

BIS Quarterly ReviewJune 2008 International banking and financial market developmentsBIS Quarterly ReviewMonetary and Economic DepartmentEditorial Committee:Claudio Borio Frank Packer Paul Van den BerghWhite Már Gudmundsson Eli Remolona William Robert McCauley Philip TurnerGeneral queries concerning this commentary should be addressed to Frank Packer(tel +41 61 280 8449, e-mail: frank.packer@), queries concerning specific parts to theauthors, whose details appear at the head of each section, and queries concerning the statisticsto Philippe Mesny (tel +41 61 280 8425, e-mail: philippe.mesny@).Requests for copies of publications, or for additions/changes to the mailing list, should be sent to:Bank for International SettlementsPress & CommunicationsCH-4002 Basel, SwitzerlandE-mail: publications@Fax: +41 61 280 9100 and +41 61 280 8100This publication is available on the BIS website ().©Bank for International Settlements 2008. All rights reserved. Brief excerpts may be reproduced or translated provided the source is cited.ISSN 1683-0121 (print)ISSN 1683-013X (online)BIS Quarterly ReviewJune 2008International banking and financial market developmentsOverview : a cautious return of risk tolerance (1)Credit market turmoil gives way to fragile recovery (1)Box: Estimating valuation losses on subprime MBS with theABX HE index – some potential pitfalls (6)Bond yields recover as markets stabilise (8)A turning point for equity prices? (11)Emerging market investors discount growth risks (12)Tensions in interbank markets remain high (13)Highlights of international banking and financial market activity (17)The international banking market (17)The international debt securities market (23)Derivatives markets (24)Box: An update on local currency debt securities marketsin emerging market economies (28)Special featuresInternational banking activity amidst the turmoil (31)Patrick McGuire and Goetz von PeterThe build-up of international bank balance sheets (32)Developments in the second half of 2007 (36)Bilateral exposures of national banking systems (39)Concluding remarks (42)Managing international reserves: how does diversification affect financial costs? 45 Srichander RamaswamyFramework of the analysis (46)Risk-return trade-offs (48)Financial cost of acquiring reserves through FX intervention (49)Box: Methodology for computing estimates of financial cost (51)Central bank objectives and FX reserve allocation (53)Conclusions (54)Credit derivatives and structured credit: the nascent markets of Asiaand the Pacific (57)Eli M Remolona and Ilhyock ShimCredit default swaps (58)Traded CDS indices (60)Collaterised debt obligations (61)How the region’s markets have fared in the global turmoil (63)Conclusion (65)Asian banks and the international interbank market (67)Robert N McCauley and Jens ZukunftAsian banks’ international interbank liquidity: where do we stand? (68)Foreign banks and the local funding gap (73)Box: The Asian financial crisis: international liquidity lessons (76)Conclusions (78)BIS Quarterly Review, June 2008 iiiRecent initiatives by Basel-based committees and groupsBasel Committee on Banking Supervision (81)Joint Forum (84)Financial Stability Forum (87)Statistical Annex ........................................................................................ A1 Special features in the BIS Quarterly Review ................................ B1 List of recent BIS publications .............................................................. B2Notations used in this Reviewe estimatedlhs, rhs left-hand scale, right-hand scalemillionbillion thousand… notavailableapplicable. not– nil0 negligible$ US dollar unless specified otherwiseDifferences in totals are due to rounding.iv BIS Quarterly Review, June 2008BIS Quarterly Review, June 20081Ingo Fender +41 61 280 8415ingo.fender@Peter Hördahl+41 61 280 8434peter.hoerdahl@Overview: a cautious return of risk toleranceFollowing deepening turmoil and rising concerns about systemic risks in the first two weeks of March, financial markets witnessed a cautious return of investor risk tolerance over the remainder of the period to end-May 2008. The process of disorderly deleveraging which had started in 2007 intensified from end-February, with asset markets becoming increasingly illiquid and valuations plunging to levels implying severe stress. However, markets subsequently rebounded in the wake of repeated central bank action and the Federal Reserve-facilitated takeover of a large US investment bank. In sharp contrast to these favourable developments, interbank money markets failed to recover, as liquidity demand remained elevated.Mid-March was a turning point for many asset classes. Amid signs of short covering, credit spreads rallied back to their mid-January values before fluctuating around these levels throughout May. Market liquidity improved, allowing for better price differentiation across instruments. The stabilisation of financial markets and the emergence of a somewhat less pessimistic economic outlook also contributed to a turnaround in equity markets. In this environment, government bond yields bottomed out and subsequently rose considerably. A reduction in the demand for safe government securities contributed to this, as did growing perceptions among investors that the impact from the financial turmoil on real economic activity might turn out to be less severe than had been anticipated. Emerging market assets, in turn, performed broadly in line with assets in the industrialised economies, as the balance of risk shifted from concerns about economic growth to those about inflation.Credit market turmoil gives way to fragile recoveryFollowing two weeks of increasingly unstable conditions in early March, credit markets were buoyed by a cautious return of risk tolerance, with spreads recovering from the very wide levels reached during the first quarter of 2008. Sentiment turned in mid-March, following repeated interventions by the Federal Reserve to improve market functioning and to help avert the collapse of a major US investment bank. As these actions alleviated earlier concerns about risks to the financial system, previously dysfunctional markets resumed trading and prices rallied across a variety of risky assets.2BIS Quarterly Review, June 2008Between end-February and end-May, the US five-year CDX high-yield index spread tightened by about 144 basis points to 573, while corresponding investment grade spreads fell by 63 basis points to 102. European and Japanese spreads broadly mirrored the performance of the major US indices, declining by between 25 and 153 basis points overall. Between 10 and 17 March, all five major indices had been pushed out to or near the widest levels seen since their inception. They then rallied back and seemed to stabilise around their mid-January values, remaining significantly above the levels prevailing before the start of the market turmoil in mid-2007 (Graph 1).business lines, tightening repo haircuts caused a number of hedge funds and other leveraged investors to unwind existing positions. As a result, concerns underlying exposures are almost entirely protected by federal guarantees, as summer of 2007 (Graph 3, right-hand panel).BIS Quarterly Review, June 20083Fears about collapsing financial markets reached a peak in the week March, triggering repeated policy actions by the US authorities. investment grade credit default swap (CDS) indices underperforming lower-quality benchmarks (Graph 4, left-hand and centre panels). Spreads were temporarily arrested when, on 11 March, the Federal Reserve announced an expansion of its securities lending activities targeting the large US dealer banks (see section on money markets and Table 1 below). European CDS indices tightened by more than 10 basis points on the news, while the two key basis points down, respectively (Graph 1). allowing it to make secured advance payments to the troubled investment These developments appeared to herald a turning point in the market, funds target down to 2.25%. Earnings announcements by major investment banks on 18 and 19 March that were better than anticipated provided further support, with investors increasingly adopting the view that various central bank initiatives aimed at reliquifying previously dysfunctional markets were gradually gaining traction. Consistent with perceptions of a considerable reduction in systemic risk, spreads, and particularly those for financial sector and other investment grade firms, tightened from the peaks reached in early March(Graph 4). Movements were partially driven by the unwinding of speculative short positions, as suggested by changes in pricing differentials across products with similar exposures, according to the ease with which such positions can be opened or closed. For example, spreads on CDS contracts referencing the major credit indices moved more strongly than those on the same indices’ constituent names (Graph 1, centre and right-hand panels). Similarly, CDS markets outperformed those for comparable cash bonds, as market participants adjusted their synthetic trades.risks (Graph 1, centre and right-hand panels). Similarly, implied volatilities from CDS index options eased into the second quarter, indicating a somewhat reduced uncertainty about shorter-run credit spread movements (Graph 3, centre and right-hand panels).losses based on ABX prices (see box). This was despite the lack of a recovery for the index series with lower original ratings, whose prices continued to4 BIS Quarterly Review, June 2008BIS Quarterly Review, June 20085suggest expectations of complete writedowns of all underlying bonds by mid-2009 (Graph 2, centre panel). At these low levels, and with none of the ABX indices having experienced any principal writedowns so far, investors appeared to be pricing in the possibility of legislation writing down mortgage principal. Against this background, issuance of private-label mortgage-backed securities remained depressed, with volume growth coming mainly from US agency-Supported by optimism about banks’ recapitalisation efforts, spreads pace of capital replenishment. Following news of a rights issue on 31 March, CDS spreads referencing debt issued by Lehman Brothers tightened. UBS announced large first quarter losses and a fully underwritten capital increase on 1 April, and other institutions followed over the rest of the month. Globally, banks managed to raise more than $100 billion of new capital in April alone, stemming the deterioration in capital ratios. Financial CDS spreads, the monoline segment excluded, outperformed corresponding equity prices in the process (Graph 4, right-hand panel), reflecting diminishing concerns about imminent financial sector risk as well as the dilutory effects of equity financing. Markets retraced some of these gains in early May, partially driven by strong supply flows from corporate issuers that included, at $9 billion, the largest US dollar deal by a non-US borrower in seven years. Volumes were dominated by6 BIS Quarterly Review, June 2008Pitfalls in using the ABX. Estimated mark to market losses and actual writedowns made by banks and other investors can differ for a variety of reasons. Analysts, depending on their objective, thus have to be mindful of potential sources of bias. At least three such sources can be identified, of which two are specific to the ABX index:•Accounting treatment. Subprime MBS are held by a variety of investors and for different purposes. While large amounts of outstanding subprime MBS are known to reside inbanks’ trading books, banks and other investors may also hold these securities tomaturity. This can result in different accounting treatments, which would tend to deflateactual writedowns and impairment charges relative to estimates of mark to market losseson the basis of market indices, such as the ABX. The size of this effect, however, isdifficult to determine. Further complexities are added once securities cease to be tradedin active markets, implying the use of valuation techniques, which may differ acrossinvestors, in establishing fair value.5•Market coverage. ABX prices may not be representative of the total subprime universe, due to limited index coverage of the overall market. Original balance across all four serieshas averaged about $31 billion. This compares to average monthly MBS issuance ofsome $36 billion over the 10 quarters up to mid-2007, ie almost a month’s worth ofsubprime MBS supply per index series. Similarly, with 2004–07 vintage subprime MBSvolumes estimated at around $600 billion in outstanding amounts, each series representssome 5% of the overall universe on average. At the same time, ABX deal composition isknown to be quite similar in terms of collateral attributes (such as FICO scores and loan-to-value ratios) to the overall market (by vintage).6 Therefore, despite somewhat limitedcoverage, this particular source of bias may not be large.•Deal-level coverage. Similarly, ABX prices may not be representative because each index series covers only part of the capital structure of the 20 deals included in the index(see Graph A, right-hand panel, for an illustration).7 In particular, tranches referenced bythe AAA indices are not the most senior pieces in the capital structure, but those with thelongest duration (expected average life) – the so-called “last cash flow bonds”. Theseclaims will receive any cash flow allocations sequentially after all other AAA trancheshave been paid; and tend to switch to pro rata pay only when the highest mezzaninebond has been written down. It follows that AAA ABX index prices are going to reflectdurations that are longer, and effective subordinations that are lower, than those of theremaining AAA subprime MBS universe. As a result, using newly available data for MBStranches with shorter durations, the $119 billion of losses implied by the ABX AAA indicesas of end-May would be some 62% larger than those implied under more realisticassumptions.8_________________________________1 See, for example, International Monetary Fund, Global Financial Stability Report, April 2008, pp 46–52, and Box 1 in Bank of England, Financial Stability Report, April 2008.2 Supplementary indices, called ABX HE PENAAA, were introduced in May 2008 to provide additional pricing information for all four existing vintages.3 An alternative approach, likely to lead to very different results, would estimate future default-related cash flow shortfalls on the basis of deal-level or aggregate data for subprime securities. To obtain these estimates, such methodologies rely on information about collateral performance and require the analyst to make assumptions about structural relationships and model parameters. Typical subprime loss projections, for example, use delinquency data and assumptions about factors such as delinquency-to-default transitions, default timing, and losses-given-default. See Box 1 in the Overview section of the December 2007 BIS Quarterly Review for an example on the basis of an approach devised by UBS. 4Mark to market losses (relative to par) are calculated assuming that unrated tranches are written down completely; ABX prices for the BBB– indices are used to mark BB collateral; rated tranches from the 2004 vintage are assumed unimpaired; outstanding amounts remain static.5 For details, see Global Public Policy Committee, Determining fair value of financial instruments under IFRS in current market conditions, December 2007.6 See, for example, UBS, Mortgage Strategist, 17 October 2006. 7 Incomplete coverage at the deal level further reduces effective market coverage: typical subprime MBS structures have some 15 tranches per deal, of which only five were originally included in the ABX indices. As a result, each series references less than 15% of the underlying deal volume at issuance.8 Duration effects at the AAA level are bound to be significant for overall loss estimates as the AAA classes account for the lion’s share of MBS capital structures. Using prices for the newly instituted PENAAA indices, which reference “second to last” AAA bonds, to calculate AAA mark to market losses generates an estimate of $73 billion. This, in turn, translates into an overall valuation loss of $205 billion (ie some 18% below the unadjusted estimate of $250 billion).capitalisation had recovered, while remaining weaker than before the crisis. At the same time, still-elevated implied volatilities suggested ongoing investor uncertainty over the future trajectory of credit markets. With the credit cycle continuing to deteriorate and related losses on exposures outside the residential mortgage sector looming, it was thus unclear whether liquidity supply and risk tolerance had recovered to an extent that would help maintain this improved environment on a sustained basis.Bond yields recover as markets stabiliseFrom its low point on 17 March, the 10-year US Treasury bond yield rose by 75 basis points to reach 4.05% at the end of May. During this period, 10-year yields in the euro area and Japan climbed by around 70 and 50 basis points, respectively, to 4.40% and 1.75% (Graph 5, left-hand panel). In US and euro area bond markets, the increase in yields was particularly pronounced for short maturities, with two-year yields rising by 130 basis points in the United States and by almost 120 basis points in the euro area (Graph 5, centre panel). Two-year yields went up in Japan too, but by a more modest 35 basis points. In addition to reduced safe haven demand for government securities, the rise in short-term yields reflected a reassessment among investors of the need for monetary easing, following the stabilisation of financial markets.In the first two weeks of March, as the financial turmoil deepened and forward rates dropping (Graph 6, right-hand panel). While flight to safety and other effects relating to the volatility in financial markets may have influenced consistent with the observed fall at the short end of the forward break-evencurve. At the same time, these same concerns led investors to increasinglyexpect the Federal Reserve to maintain a more accommodative policy stancethan normal in an effort to contain the fallout on economic growth. Insofar asthis was seen as likely to lead to higher prices down the road, it could explainthe rise in distant forward break-even rates at the time.As the situation in financial markets stabilised after the rescue of BearStearns in mid-March, and perceptions of the economic outlook improvedsomewhat, the US forward break-even curve shifted in the opposite directionand flattened considerably. To a large extent, this shift in the forward curve islikely to have reflected a reversal of the same influences that had been at playin the first two weeks of March: the dampening effect on prices coming from theturmoil was perceived to be weaker after mid-March, while the Federal Reservewas seen to be less likely to deliver further sharp rate cuts. Moreover, upwardprice pressures appeared to intensify in the short to medium term, with foodprices rising continuously and oil prices reaching new all-time highs during thisperiod (Graph 5, right-hand panel), pushing near-term forward break-evenrates further upwards.real yields reflected a combination of expectations of higher average realinterest rates in coming years and a reversal of flight to safety pressures. Theformer component, in turn, was due to perceptions among investors that thereal economic fallout from the financial turmoil was likely to be less severe thanhad previously been anticipated. This was despite indications of deterioratingconsumer confidence amid tighter bank lending standards and continuedweakness in US housing markets. The revival in investor confidence seemedinstead to follow from the stabilisation in markets and from a number ofrelatively upbeat macroeconomic announcements. These included better thangovernment securities.In line with perceptions that the stabilisation of markets had reduced therisks to economic growth somewhat, prices of short-term interest rateindicating expectations of a period of stable rates, followed by rising rates inthe first half of 2009 (Graph 7, left-hand panel). In the euro area, EONIA swapprices at the beginning of March had signalled expectations of sizeable ECBrate cuts, but by end-May prices had shifted to reflect expectations of graduallyincreasing policy rates (Graph 7, centre panel). Meanwhile in Japan,expectations of mildly falling policy rates in March had by May been revised toindicate rising rates (Graph 7, right-hand panel).A turning point for equity prices?to end-2007 levels, gained almost 10% between 17 March and end-May. Equity markets in Europe and Japan, which had seen losses in excess of 20% between the turn of the year and 17 March, subsequently also displayed a strong recovery, with the EURO STOXX gaining 11% and the Nikkei 225 rising Reflecting the improved situation in financial markets during this period, by almost 20% and 34%, respectively. These gains occurred despiteannouncements by several banks of record losses during the first quarter amidcontinued credit-related write-offs. Investors obviously took solace from the factthat losses – although big – were no worse than expected, and that a numberof banks had been successful in their recapitalisation efforts (see credit marketsection above).surprises remained well above that of negative surprises, provided somesupport for equity prices. In addition, as fears failed to materialise that economic growth might slow dramatically in the first few months of the year,investors increasingly began to see equity valuations as attractive following thesharp price declines in late 2007 and early 2008. markets recovered after a sharp dip in March (Graph 8, right-hand panel).Emerging market investors discount growth risksequities fell up to mid-March, before rebounding in the wake of the change inmarket sentiment following the Bear Stearns rescue in the United States.Between end-February and end-May, the MSCI emerging market indexgained about 4% in local currency terms, and was up more than 14% from thelows established in mid-March. Latin American markets, which had seen ahigh trading volumes in commodity derivatives (see the Highlights section inthis issue) and speculative demand as a source of part of that strength, otherspointed to low supply elasticities and expectations of sustained rates ofindustrialisation throughout the emerging markets. With the region being amajor net commodities importer and natural disaster contributing to weakerequity prices in China, Asian markets were broadly flat over the period.Emerging Europe, in turn, remained exposed to the risk of a reversal in privatecapital flows, owing to large current account deficits and associated financingneeds in a number of countries. Nevertheless, strong gains in Russia and thebetter than expected growth performance of major European economies in thefirst quarter seemed to aid equity markets in May.Emerging market credit spreads, as measured by the EMBIG index,accounting for most of the spread tightening, the EMBIG remained almost flatin return terms, gaining about 1.1% between end-February and end-May(Graph 9, left-hand panel). Large stocks of foreign reserves and favourablemacroeconomic performance in key emerging market economies continued toprovide support, aiding the market recovery. Spread dispersion remained high,pointing to ongoing price differentiation according to credit quality (Graph 10,centre panel). At the same time, with inflation running well above target in anumber of major emerging market economies, policy credibility appeared tobecome more of a concern, putting pressure on local bond markets. Risinginflation expectations, combined with increasing US Treasury yields andrelatively resilient markets during the earlier stages of the recent marketturmoil, may thus have contributed to a somewhat more muted performancefrom emerging market bonds relative to other asset markets over the periodsince mid-March.Tensions in interbank markets remain highas high at the end of May as three months earlier, across most horizons and inall three major markets (Graph 10). This appeared to imply expectations thatinterbank strains were likely to remain severe well into the future.After a relatively smooth turn of the year, interbank market tensions hadappeared to ease somewhat until early March 2008, and Libor-OIS spreadshad shown some signs of stabilising. However, as the financial turmoilsuddenly deepened in the second week of March, following an acceleration inmargin calls and rapid unwinding of trades (see the credit section above),interbank market pressures quickly increased. With market rumoursproliferating about imminent liquidity problems in one or more large investmentbanks, banks became increasingly wary of lending to others. At the same time,their own demand for funds jumped as they sought to avoid being perceived ashaving a shortage of liquidity.Selected central bank liquidity measures during the period under review7 March The Federal Reserve increases the size of its Term Auction Facility (TAF) to $100 billion andextends the maturity of its repos to up to one month.11 March The Federal Reserve introduces the Term Securities Lending Facility (TSLF), which allowsprimary dealers to borrow up to $200 billion of Treasury securities against collateral. Theexisting dollar swap arrangements between the Federal Reserve and the ECB and the SNB areincreased from a total of $24 billion to $36 billion.16 March The Federal Reserve introduces the Primary Dealer Credit Facility (PDCF), which providesovernight funding for primary dealers in exchange for collateral. The Federal Reserve alsolowers the spread between the discount rate and the federal funds rate from 50 to 25 basispoints, and lengthens the maximum maturity from 30 to 90 days.28 March The ECB announces that the maturity of its longer-term refinancing operations (LTROs) wouldbe extended from up to three months to a maximum of six months.21 April The Bank of England introduces the Special Liquidity Scheme, under which banks can swapilliquid assets for Treasury bills.2 May The Federal Reserve boosts the size of its TAF programme to $150 billion, and announces abroadening of the collateral eligible for the TSLF auctions. The dollar swap arrangements withthe ECB and the SNB are increased further, from $36 billion to $62 billion.Source: Central bank press releases. Table 1The near collapse and subsequent takeover of Bear Stearns onMarch highlighted the risks that banks face in such situations. On the would not be allowed to fail, and this helped restore order in other markets. On the other hand, the speed with which Bear Stearns’ access to market liquidity had collapsed underscored the vulnerability of other banks in this regard, which kept Libor-OIS spreads high even as CDS spreads on banks and brokerages Throughout the period, central banks maintained and even stepped up activity from central banks seemed to have limited immediate impact oninterbank rates. To some extent, this may have reflected the fact that while thesums involved in central bank liquidity schemes were large in absolute terms,they were still rather limited compared to banks’ assessment of their overallliquidity needs against the background of a sharp decline in traditional sourcesof funding. One significant source of short-term funding for banks in the pasthas been money market mutual funds. Such funds have seen substantialinflows since the outbreak of the financial turmoil (Graph 11, left-hand panel),reflecting a noticeable reduction in investors’ appetite for risk. However, thisloss of risk appetite also resulted in money market funds shifting theirinvestments increasingly into treasury bills and other safe short-term securities,hence depriving banks of a key funding source (Graph 11, centre panel). Thissuggests that determining how persistent the interbank tensions will be maydepend significantly, among other things, on how long the risk appetite ofmoney market fund managers, and investors more broadly, will continue to bedepressed.。

LESSON 12-处理反对

1. 信徒並非辯護律師,只是 證人 。

A. 以柔制剛法(柔道法): 利用對方的推力將他推倒。當上述 反對是出現於講述福音 之前 ,

可運用這技巧。

1. 聖經其中一種最佳的自證方法是藉 著 預言 的應驗

4. 將舊約中八個有關 基督 的預言 逐一讀出。

8. 完全應驗在基督身上的舊約預言 遠超八個,乃是 333 個。

單元十二 處理反對

A. 你的首要任務是 傳福音 ,

不是解答難題

b. 你的 態度 必須尊重別人

1. 意思是在對方未提出反對

之前 已回答了

1. 如果你會在 稍後 的講述中處理

該問題,大可延遲至該部分的講 述時才作答。

D. 迅速回答

如果你有把握,便一針見血地回 答,並且回到大綱繼續 講述 。

學習指引問題

是 非 1. 所有反對其實都是迴避的煙幕。(153)

是 非 2. 處理任何反對福音的最佳方法,是迎頭痛擊法。 (154) 3. 處理反對的基本態度有三:(153) a. 切勿爭論 b. 表達欣賞 c. 給予稱讚

. . .

學習指引問題

4. 五個處理反對的常規是:(154-156) a. 懇切祈禱 b. 預先排除 c. 稍為拖延 d. 迅速解答 e. 虛心研究

. . . . .

5. 在佈道的過程上,信徒是被稱為:(156) a. 對方屬靈情況的審判官; b. 見證人; c. 見證專家; d. 未信者的辯護律師。 6. 有關基督的預言遠超八個,最少有 333 個。

普心复习重点内容整理

第一章:心理学与生活(非重点但有些容要注意)1.心理学的目标:心理学是研究什么的研究关于个体行为及心智的过程,目标在于描述发生的事情、解释发生的事情、预测将要发生的事情和控制发生的事情。

2.什么让心理学与众不同:心理学中的科学方法科学方法包括一组用来分析和解决问题的有序步骤。

这种方法用客观收集到的信息作为得出结论的事实基础。

3.心理学的历史根基:重要事件、流派发展(重点在结构主义—机能主义—心理动力学—行为主义—人本主义)16版P8●结构主义产生于特和铁钦纳的工作,它强调由基本感觉构成的心理和行为的结构。

德国心理学家惠特尔曼的格式塔心理学是结构主义的一个重要分支。

方法:省法。

●机能主义是由詹姆斯和杜威发展出来的,强调行为的目的。

与结构主义相反,没有将意识简化为元素、容和结构,而认为意识是流动的,心理的特征是与环境持续进行相互的作用。

因此,重要的是心理过程的行为和机能,而不是容。

尽管存在差异,结构主义和机能主义的见解依然为当代心理学的繁荣发展共同创造了环境。

心理学家们现在同时探索行为的结构与机能。

因此可以说结构主义和机能主义是现代心理学的根基。

●心里动力学观点认为行为是由本能力量、在冲突以及意识和无意识的动机驱使的。

这种观念认为,人的行为是从先天的本能和生物驱动力中产生的,且试图解决个人需要和社会需求之间的冲突。

剥夺状态、生理唤起以及冲突行为都为行为提供了力量。

当机体的需要得到了满足而驱力降低时,机体就停止反应。

行为的主要目的是降低紧感。

●行为主义观点认为行为是由外部的刺激条件决定的。

约翰华生认为心理学的研究应该在于寻找“控制不同物种可观察行为的规律”。

行为主义对后世的心理学研究有着重要的影响,它对严格的实验和仔细定义的变量的强调,影响了大多数领域。

尽管行为主义者开展的许多基础实验主要是在动物身上进行的,但行为主义的原则已经被广泛应用于人类问题,如教育儿童、矫正行为障碍和创建理想化社会。

●人本主义观点强调个体做出理性抉择的在能力。

Article1

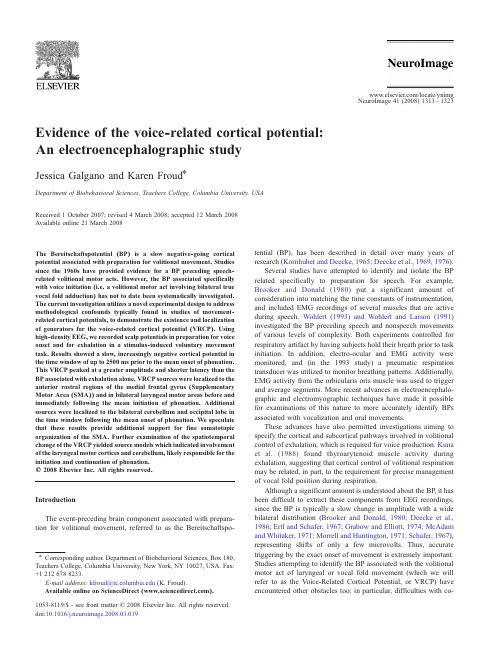

Evidence of the voice-related cortical potential:An electroencephalographic studyJessica Galgano and Karen Froud ⁎Department of Biobehavioral Sciences,Teachers College,Columbia University,USA Received 1October 2007;revised 4March 2008;accepted 12March 2008Available online 21March 2008The Bereitschaftspotential (BP)is a slow negative-going cortical potential associated with preparation for volitional movement.Studies since the 1960s have provided evidence for a BP preceding speech-related volitional motor acts.However,the BP associated specifically with voice initiation (i.e.a volitional motor act involving bilateral true vocal fold adduction)has not to date been systematically investigated.The current investigation utilizes a novel experimental design to address methodological confounds typically found in studies of movement-related cortical potentials,to demonstrate the existence and localization of generators for the voice-related cortical potential (VRCP).Using high-density EEG,we recorded scalp potentials in preparation for voice onset and for exhalation in a stimulus-induced voluntary movement task.Results showed a slow,increasingly negative cortical potential in the time window of up to 2500ms prior to the mean onset of phonation.This VRCP peaked at a greater amplitude and shorter latency than the BP associated with exhalation alone.VRCP sources were localized to the anterior rostral regions of the medial frontal gyrus (Supplementary Motor Area (SMA))and in bilateral laryngeal motor areas before and immediately following the mean initiation of phonation.Additional sources were localized to the bilateral cerebellum and occipital lobe in the time window following the mean onset of phonation.We speculate that these results provide additional support for fine somatotopic organization of the SMA.Further examination of the spatiotemporal change of the VRCP yielded source models which indicated involvement of the laryngeal motor cortices and cerebellum,likely responsible for the initiation and continuation of phonation.©2008Elsevier Inc.All rights reserved.IntroductionThe event-preceding brain component associated with prepara-tion for volitional movement,referred to as the Bereitschaftspo-tential (BP),has been described in detail over many years of research (Kornhuber and Deecke,1965;Deecke et al.,1969,1976).Several studies have attempted to identify and isolate the BP related specifically to preparation for speech.For example,Brooker and Donald (1980)put a significant amount of consideration into matching the time constants of instrumentation,and included EMG recordings of several muscles that are active during speech.Wohlert (1993)and Wohlert and Larson (1991)investigated the BP preceding speech and nonspeech movements of various levels of complexity.Both experiments controlled for respiratory artifact by having subjects hold their breath prior to task initiation.In addition,electro-ocular and EMG activity were monitored,and (in the 1993study)a pneumatic respiration transducer was utilized to monitor breathing patterns.Additionally,EMG activity from the orbicularis oris muscle was used to trigger and average segments.More recent advances in electroencephalo-graphic and electromyographic techniques have made it possible for examinations of this nature to more accurately identify BPs associated with vocalization and oral movements.These advances have also permitted investigations aiming to specify the cortical and subcortical pathways involved in volitional control of exhalation,which is required for voice production.Kuna et al.(1988)found thyroarytenoid muscle activity during exhalation,suggesting that cortical control of volitional respiration may be related,in part,to the requirement for precise management of vocal fold position during respiration.Although a significant amount is understood about the BP,it has been difficult to extract these components from EEG recordings,since the BP is typically a slow change in amplitude with a wide bilateral distribution (Brooker and Donald,1980;Deecke et al.,1986;Ertl and Schafer,1967;Grabow and Elliott,1974;McAdam and Whitaker,1971;Morrell and Huntington,1971;Schafer,1967),representing shifts of only a few microvolts.Thus,accurate triggering by the exact onset of movement is extremely important.Studies attempting to identify the BP associated with the volitional motor act of laryngeal or vocal fold movement (which we will refer to as the V oice-Related Cortical Potential,or VRCP)have encountered other obstacles too:in particular,difficulties withco-/locate/ynimg NeuroImage 41(2008)1313–1323Corresponding author.Department of Biobehavioral Sciences,Box 180,Teachers College,Columbia University,New York,NY 10027,USA.Fax:+12126788233.E-mail address:kfroud@ (K.Froud).Available online on ScienceDirect ().1053-8119/$-see front matter ©2008Elsevier Inc.All rights reserved.doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.03.019registration between physiological measurements and electrophy-siological instrumentation,inaccurate identification of vocal fold movement onset,and methodological confounds between voice, speech and language(Brooker and Donald,1980;Deecke et al., 1986;Ertl and Schafer,1967;Grabow and Elliott,1974;McAdam and Whitaker,1971;Morrell and Huntington,1971;Schafer,1967). In addition,respiratory artifact or R-wave contamination of the BP preceding speech has proven a major difficulty,particularly in early studies(Deecke et al.,1986).Larger-amplitude artifacts due to head-,eye-,lip-,mouth movements and respiration must also be eliminated before signal averaging(Grözinger et al.,1980).Earlier studies investigating voice-related brain activations typically confounded the distinctions between voice,speech and language.Voice refers to the sound produced by action of the vocal organs,in particular the larynx and its associated musculature. Speech is concerned with articulation,and the movement of organs responsible for the production of the sounds of language—in particular,those of the oral tract,including the lips,tongue and nguage refers to the complex set of cognitive operations involved in producing and understanding the systematic processes which underpin communication.Therefore,studies which have at-tempted to isolate voice or speech-related activity by the use of word production instead have described activation relating to a combina-tion of these cognitive and motor operations(for example,Grözinger et al.(1975)used word utterances amongst their tasks designed to elicit speech-related activations;Ikeda and Shibasaki(1995)used single words as well as nonspeech-related movements like lingual protrusion;McAdam and Whitaker(1971)used unspecified three-syllable words to elicit ostensibly speech-related activity).Con-versely,in a magnetoencephalography(MEG)study,Gunji et al. (2000)examined the vocalization-related cortical fields(VRCF) associated with repeated production of the vowel[u].Microphones placed close to the mouth were used to capture the sound waveform from the vocalization;the onset of the waveform provided the trigger for segmenting and averaging epochs.This design carefully attempts to identify vocalization-related fields;however,operationalizing a procedure which is able to most closely capture the onset of voicing is particularly difficult.Difficulty stems,in part,from the limited number of compatible neuroimaging techniques and instruments able to capture these phenomena.The present study contributes to understanding of the timing and distribution of the VRCP by addressing two major sources of methodological confound:the blurring of distinctions between voice, speech and language;and the accurate identification of movement onset for triggering and epoch segmentation.Furthermore,we use high-density EEG recordings,providing an increased level of detail in terms of the scalp topography,and additionally enabling the application of source modeling techniques to ensure accurate identification of the VRCP.Our results provide novel insight into voice generation by addressing the following research question: Can the true VRCP,associated only with laryngeal activity,be isolated from related movement potentials,by utilizing the right combination of control and experimental tasks?We predicted that a stimulus-induced voluntary movement paradigm would yield significant differences in the characteristics of the Readiness Potentials associated with(a)initiation of phonation and(b)respiration.To be specific,we predicted the existence of an isolable voice-related cortical potential associated only with prepara-tion for initiation of phonation and greater amplitude of the VRCP vs. the respiration-related cortical potential.We also predicted that VRCP sources would be localized to the Supplementary Motor Area, primary motor cortices,and sensori-motor regions.Elucidation of the neural mechanisms of normal voice is a crucial step towards understanding the role of functional reorganization in cortical and subcortical networks associated with voice production, both for changes in the normal aging voice,and in pathological populations.This approach to determining the neural correlates of voice initiation could provide a foundation for creating neurophy-siologic models of normal and disordered voice,ultimately informing our understanding of the effects of surgical,medicinal and/or behavioral interventions in voice-disordered populations. The findings could ultimately provide us with new basic science information regarding the relative benefit of different treatment approaches in the clinical management of neurogenic voice disorders.In addition,the larger significance of this work is related to the fact that voice disorders are currently recognized as the most common cause of communication difficulty across the lifespan,with a lifetime prevalence of almost30%(Roy et al.,2005). Materials and methodsA stimulus-induced voluntary movement paradigm in which trials of different types were presented in subject-specific rando-mized orders was utilized.This method addressed the documented problem of the classic BP paradigm which involves self-paced movements separated by short breaks:the person is already conscious of and preparing for a particular movement and there is a known repetition rate of the movements(Libet et al.,1982,1983). This can lead to automatic movements,which change the presentation of the VRCP.In our procedure,it is not possible for the participant to predict ahead of time which task they have to perform,which allows for a spontaneous movement.The movements were chosen to avoid another methodological confound,between voice,speech and language tasks.Requiring subjects to produce linguistically complex units,such as sounds or words(e.g.Ikeda and Shibasaki,1995;Wohlert and Larson,1991; Wohlert,1993)led to some debate concerning whether BPs for speech might be lateralized to the dominant hemisphere for language.This problem is avoided in the current study,and the problem of movement artifacts involved in speech and speech-like movements such as lip-pursing or vowel-production(Gunji et al., 2000;Wohlert and Larson,1991;Wohlert,1993),in particular of back,tense,rounded vowels(such as the[u]used in Gunji et al's experiments),by utilizing a task which involves voicing only,and has no related speech or language overlay.The actions of breathing out through the nose,and gentle-onset humming of the bilabial nasal [m]without labial pressing,are equivalent actions in terms of involvement of the articulatory tract,the only difference being the initiation of vocal fold movement in the humming condition.By having participants breathe or hum following a period of breath-holding,the possibility of R-wave contamination is also reduced (Deecke et al.,1986).Onset of phonation is established by mea-suring vocal fold closure using electroglottography(EGG),and a telethermometer attached to a trans-nasal temperature probe was used for the earliest possible identification of exhalation onset. Subjects24healthy subjects(21females and3males)with an age range of21–35years of age(mean age=26years)participated in the study.All subjects were informed of the purpose of the study and1314J.Galgano,K.Froud/NeuroImage41(2008)1313–1323gave informed consent to participate,following procedures ap-proved by the local Institutional Review Board.All participants took part in a training phase,which was identical to the experi-mental procedure and served to train participants on the expected response to each screen.Each step of the procedure was discussed and explained as it was occurring,and there was ample opportunity for feedback to be provided to ensure accurate task performance.EEG/ERP experimental set-up and proceduresEEG data acquisitionScalp voltages were collected with a 128channel Geodesic Sensor Net (Tucker,1993)connected to a high-input impedance amplifier (Net Amps200,Electrical Geodesics Inc.,Eugene,OR).Amplified analog voltages (.1–100Hz bandpass)were digitized at 250Hz.Individual sensors were adjusted until impedances were less than 30–50k Ω,and all electrodes were referenced to the vertex (Cz)during recording.The net included channels above and below the eyes,and at the outer canthi,for identification of EOG.The EEG,EOG,stimulus triggered responses,EGG and telethermometer data were acquired simultaneously and later processed offline.Recording of respirationA nasal telethermometer (YSI Model 43single-channel)with a small sensor (YSI Precision 4400Series probe,style 4491A)was placed 2–4cm inside one nostril transnasally and used to measure the temperature of inhaled and exhaled air.Readings from the telethermometer were digitally recorded by interfacing the teletherm-ometer with one outrider channel input to the EEG net amplifier connection,for co-registration of the time course of respiration with the continuous EEG.Recording of voice onsetA Kay Telemetric Computerized Speech Lab,Model 4500(housing a Computerized Speech Lab Main Program Model 6103Electroglottography)with 2electrodes placed bilaterally on the thyroid cartilage,adjacent to the thyroid notch,was used to measurevocal fold closure and opening.The EGG trace was acquired in the Computerized Speech Lab (CSL)proprietary software and co registered offline with EEG and telethermometer recordings,in order to determine error trial locations and confirm onset of vocal fold adduction and controlled exhalation.V oice sounds were also recorded by microphone on a sound track acquired on the CSL computer,sampling at 44.1kHz.A response button box permitted participant regulation of the start of each trial.At each button press,an audible “beep ”was generated by the system which provided an additional point of co-registration between the EGG system and the time of trial onset.In addition,pressing the button permitted the subject to move to the next trial set from a screen that allowed physical adjustment into a more comfortable position if needed in between tasks (to reduce movement artifact).Instructions and experimental taskThe experimental task required subjects to hold their breath for 4s,followed by breathing out or humming through the nose.The action carried out was determined by presentation of a “Go ”screen after the breath-holding interval;the “Go ”screen randomly presented either a “Breathe ”or “Hum ”instruction.To avoid using language-based stimuli in this experiment,the instructions to breath or hum were represented instead by letter symbols:a large 0for breathing,and a large M for humming.There were eighty trials altogether (forty voice and forty breathe).Experimental stimuli were presented using Eprime stimulus presentation software (Psychology Software Tools,Pittsburgh,PA).Subjects were visually monitored via a closed circuit visual surveillance system,to ensure compliance with experimental conditions.Each trial (breathe or hum)was followed by a black screen,which indicated to participants that they could take a break before the next trial,swallow,blink and make themselves comfortable (this was intended to reduce movement artifacts during trials).Participants used button presses to indicate when they were ready to continue on to the next trial (Fig.1).Data analysisRecorded EEG was digitally low-pass filtered at 30Hz.Trials were discarded from analyses if they contained incorrectresponses,Fig.1.The following experimental control module display shows the timeline of stimulus presentation during the experiment.Initially,a red screen instructed the subject to hold their breath with a closed mouth (4s).This was followed by a green screen which displayed either an “M ”or “0”,prompting the subject to hum or breathe out,respectively.Following each trial,a black screen instructed the subjects to make themselves comfortable to minimize movement artifact before moving onto the next trial.When subjects were ready,a button press triggered an audio beep which allowed for co-registration of instrumentation being utilized.1315J.Galgano,K.Froud /NeuroImage 41(2008)1313–1323eye movements (EOG over 70µV),or more than 20%of the channels were bad (average amplitude over 100µV).This resulted in rejection of less than 5%of trials for any individual.EEG was rereferenced offline to the average potential over the scalp (Picton et al.,2000).EEG epochs were segmented from −3000to +500ms from onset of voicing or exhalation,and averaged within subjects.Data were baseline-corrected to a 100ms period from the start of the segment,to provide additional control for drift or other low amplitude artifact.For identification of ERPs and for further statistical analyses,two regions of interest (ROIs)were selected:the Supplementary Motor Area (SMA)ROI,and the Primary Motor Region (M1)ROI.The 7SMA sensors were centered around FCz,where SMA activations have previously been reported (e.g.Deecke et al.,1986).The M1ROI consisted of 25sensors,centered anterior to the central sulcus and located around the 10–20system electrodes F7,F3,Fz,F4,F8,A1,T3,C3,Cz,C4,T4,A2(listed left-to-right,anterior-to-posterior),where Motor-Related Potentials have been previously identified (Jahanshahi et al.,1995).See Fig.2.Statistical analysesData from averaged segments were exported to standard statistical software packages (Microsoft Excel and SPSS),permit-ting further analysis of the ERP data.Repeated measures Analysis of Variance (ANOV A)was used to evaluate interactions and main effects in a 2(Condition:voicing vs.breathing)×2(region:SMA vs.M1)×3(time window:pre-stimulus,stimulus to voice onset,and post-voice onset)comparison.The dependent variable was grand-averaged voltages across relevant sensor arrays,determined following data preprocessing.The ANOV A was followed by planned comparisons,and all statistical analyses employed the Greenhouse –Geisser epsilon as needed to deal with violations of assumptions of sphericity.Point-to-point differences in mean amplitude between the 2conditions (humming vs.breathing)were evaluated for statistical significance,using separate repeated measures t -tests performed on mean amplitude measures within a 4ms sliding analysis window.Bonferroni corrections were employed to control for type 1error arising from multiplecomparisons.Fig.2.This sensor layout displays the 128-channel Geodesic Sensor Net utilized in the current experiment.Legend:Black=SMA montage;Grey=M1montage;Black+Grey=Channels entered into Grand Average.1316J.Galgano,K.Froud /NeuroImage 41(2008)1313–1323VRCP.Time-locking of the segmented EEG to the onset of true vocal fold adduction as recorded from the electroglottograph enabled identification of the standard BP topography,with a peak at the time of the movement onset,followed by a positive reafferent potential.The topography of the VRCP was examined using true vocal fold (TVF)adduction onset obtained from the EGG recording,and is subject-specific.Individual averaged files were placed into group grand-averages.The VRCP was identified in individual averaged data and in group grand-averages,based on the distribution and latency of ponent duration and mean amplitude for each subject(and for grand-averaged data)in each experimental condition were calculated.Three pre-movement components of the VRCP were measured, i.e.early(−1500to−1000ms prior to movement onset),late(about −500ms prior to movement onset),and peak VRCP(coincides with or occurs approximately50ms prior to movement onset)(Deecke et al.,1969,1976,1984;Barret et al.,1986).To determine the onset of each VRCP component,mean amplitude traces from individual and grand-averaged voice trials were examined independently by scientists with BP experience(Jahanshahi et al.,1995;Fuller et al., 1999).The mean latency of the early VRCP(rise of the slope from the baseline),the late VRCP(point of change in slope),and the peak VRCP(most negative point at or prior to vocal fold closure)were measured.The slope of the early VRCP was calculated(in microvolts per second)between the point of onset of the early VRCP and the onset of the late VRCP.The slope of the late component was calculated from the point of onset of the late VRCP to the onset of the peak VRCP.A2(region:SMA vs.M1)×2(time window:early VRCP te VRCP/late VRCP vs.peak VRCP)repeated measures ANOV A,followed up with planned comparisons,was used to examine interactions and main effects.BESA.In order to model the spatiotemporal properties of the VRCP sources,we used Brain Electrical Source Analysis(BESA: Scherg and Berg,1991).Source modeling procedures were applied to the voice produc-tion condition only(not to the exhalation condition).This is because a telethermometer was used to record changes in temperature associated with inhalation and exhalation;however,these associated changes do not reliably correlate with the true onset of exhalation or thyroarytenoid muscle activity associated with exhalation,as evidenced by the wide variety of measures reported in the literature for determination of respiration onset(e.g.Macefield and Gandevia (1991)used EMG measured over scalene and lateral abdominal muscles;Pause et al.(1999)used a thermistor placed at the nostril to determine onset of respiration based on changes to air temperature; Gross et al.(2003)determined onset of respiration to be associated with highest cyclic subglottal pressure;and other methods have also been reported).Source localization approaches are therefore not appropriate for the exhalation condition;consequently,we con-ducted comparisons between potentials associated with exhalation and voice using statistical analyses of differences in amplitude only. Source localization procedures were conducted on the voice pro-duction condition,because in that condition we were able to identify the initiation of voicing,using electroglottography.BESA attempts to separate and image the principal components of the recorded waveform as well as localizing multiple equivalent current dipoles(ECDs).Any equivalent current dipole was fit to the data over a specified time window,and the goodness of fit was expressed as a percentage of the variance.Our procedure for developing the ECD model was closely based on procedures detailed in Gunji et al.(2000),as follows.First,we selected an interval for analyzing the data in terms of a spatiotemporal dipole model.Following Gunji et al.,we selected the interval of−150ms to+100ms,because this interval covered the approximate period from the onset of the instruction screen to preparation to move the vocal folds,through to onset of phonation and the start of auditory feedback.Gunji et al.further recommend a dipole modeling approach limited to this time interval in order to focus on brain activations just before and after vocalization,rather than attempting to model the complex and persistent sources associated with Readiness Potentials.We therefore seeded sources and fit them for orientation and location in the time window from −150ms to0ms(the averaged time of the start of phonation).The time window from0to+100ms was examined separately.Sources seeded in both time windows are described below.ResultsIndividual data were grand-averaged and component identifica-tion was based on distribution,topography,and latency of activations (individual subjects and grand-averaged data).AVRCP was identified in all subjects,maximized over fronto-central electrodes(overlying the SMA).For grand-averaged data,all electrodes overlying the SMA showed a large VRCP in the specified time window(see Fig.3). Voicing vs.Controlled Exhalation ConditionsThe ANOV A revealed that the triple Condition×Region×Time interaction was significant(F(1,124)=2488.463,p b.0001),as were both two-way interactions(Condition×Region,F(1,124)=68.428, p b.0001;Condition×Time,F(1,124)=1808.242,p b.0001; Region×Time,F(1,124)=6651.504,p b.0001).Planned compar-isons revealed that the mean amplitudes of the VRCP were significantly more negative than the BP associated with the controlled exhalation condition,and SMA amplitudes were significantly more negative than M1.The significant interaction between Condition and Region for all subjects was found to be due to the fact that,although SMA sensors were always significantly more negative than M1 sensors(t(1939.233)=26.272,p b.0001),there was a greater difference in the measured negativities in V oice trials compared to Breathe trials(see Fig.4).Further examination of the main effect of Time revealed that,as time progressed,mean amplitudes became significantly more negative(i.e.VRCPs became significantly more negative from the pre-stimulus time window to the time of voice onset and beyond). Investigations of the Condition by Time interaction revealed sig-nificant progressive increases in the measured negativities from early to late time windows for the V oice condition.However, subjects showed a greater degree of negativity in the pre-and post-screen time windows for the breathe condition only(see Fig.5).For the Controlled Exhalation/Breathing Condition,the SMA BPs from stimulus to exhalation were significantly more negative than in the pre-stimulus interval.The M1region,however,showed no significant increase in negativity until the later time windows.In other words,over the SMA sensors the movement-related negativity increased in the period leading to exhalation,as well as later;over the M1sensors,however,readings did not become significantly more negative until after movement.Investigations of the Region×Time interaction for the voicing trials showed a significant increase in the negativity over both the SMA and M11317J.Galgano,K.Froud/NeuroImage41(2008)1313–1323regions between the pre-stimulus interval and the time to voice onset.Mean amplitudes continued to become significantly more negative across time intervals post-voice onset for both regions.This is summarized in Table 1and shown in Fig.5below.To summarize,several significant findings were revealed.The voicing condition was significantly more negative than the exhalation condition,activation over SMA sensors was significantly more negative than over M1sensors,and negativities significantly increased over the three time windows for the voice condition only.VRCP slope changesThe 2×3repeated measures ANOV A examining changes in the VRCP slope (microvolts per second)revealed a significant main effect of time,with the earlier time window being associated with ashallower slope than the later time window in both Regions.No other main effects or interactions were significant.Source localization using BESAUsing BESA,we fit dipoles to the grand-averaged data from 23subjects'responses to the V oice condition.We accepted an ECD model as a good fit when the residual variance dropped to 25%or below (standard for fitting to data from individuals is 10%RV).We began by seeding pairs of dipole sources to the left and right laryngeal motor areas,and in the middle frontal gyri,known to be associated with oro-facial movement planning in humans (Chainay et al.,2004)and the origination of human motor readiness potentials (Pedersen et al.,1998),respectively.A final pair of dipoleswasFig.3.The above waveform demonstrates grand-averages of 24subjects.In the voice condition,a peak negativity of the VRCP (SMA:−10.0086,V;M1:−5.2983,V)was found at bilateral TVF adduction,evidenced by onset movement shown in the Lx (EGG)waveform.A standard BP topography in M1is revealed.The late VRCP in M1shows a steeper slope,positive deflection preceding movement onset,and longer latency when compared to SMA.In the breathe condition,peaks showed longer latencies over both M1and SMA sensors,and reduced amplitude over SMA.Steps in the stimulus presentation/analysis procedure are superimposed:the breath-holding screen starts at −4000ms,and the “Go ”screen (instruction to hum through the nose)appears after 4s of breath-holding and is shown for a further 4s period.Initiation of phonation (recorded by EGG)was established for each individual trial within each subject.The interval between the onset of the “Go ”screen and phonation is where the specific VRCP could be identified.1318J.Galgano,K.Froud /NeuroImage 41(2008)1313–1323。

普心每章重点

普心每章重点第一章:心理学的研究对象和方法1、心理学是研究心理现象的科学。

它主要研究人的认知、情绪和动机、能力、人格,也研究其他动物的心理现象。

它既研究意识,也研究无意识;既研究个体心理,也研究群体心理和社会心理。

心理不同于行为,又和行为有密切的关系。

心理支配行为,又通过行为表现出来。

因此心理学有时又被认为是研究行为和心理过程的科学。

2、心理学的基本任务是探索和揭示心理现象的规律,包括心理过程和心理结构、心理的神经机制、心理的发生和发展、心理与环境的关系等。

3、由于社会需求和科学自身的发展,心理学形成了许多重要的研究领域,如普通心理学、心理生理学、发展心理学、教育心理学、医学心理学、工业心理学、军事心理学、社会心理学等。

4、研究心理学有重要的理论和实践的意义。

在理论上,有助于形成科学的世界观和人生观;在时间上,有助于引导人的心理的健康发展,并运用心理学的规律,指导不同领域的实践活动。

5、心理学不仅是一门有吸引力的学科,而且提供了多种职业的选择的机会。

6、心理学是一门中间科学。

一方面心理学的研究目标和手段都和自然科学一样,具有自然科学的性质;另一方面,心理现象是社会生活的产物,因而研究心理现象的心理学也具有社会科学的性质。

要成为一名心理学家需要具备自然科学和社会科学两方面的知识和科学素养。

7、心理学是一门实验科学。

实验方法是心理学最重要的一种研究方法。

在实验中,研究者可以积极干预被试者的活动,创造某种条件使某种心理现象得以产生,并重复出现。

在心理学中还经常采用观察法、测验法、相关法和个案法。

8、1879年德国心理学家冯特在莱比锡大学建立了世界上第一个心理学实验室,标志着心理学作为一门独立的科学证实诞生。

心理学的当时有两个重要的历史根源,一个是近代哲学的影响,包括唯理论和经验论的影响;另一个是实验生理学的影响,它为心理学提供了一系列客观的研究方法。

9、19世纪末20世纪初是心理学中派别纷争的时期。

当时涌现出来的重要学派有:构造主义、技能主义、行为主义、精神分析学派和格式塔心理学等。

普心情绪教程

暴跳如雷

激情的作用:

积极的作用:在激情的作

有明显的外部表现 具有激动性和冲动性 持续时间短

用下,可以提高活动的效率, 更好地完成某种活动。

消极的作用:人们在激情 的作用下,往往会作出并鲁 莽、甚至遗憾终身的事情。

有明确指向性,通常由特定的对象引起

应激

应激(stress):在出乎意料的紧急和危险的情

这个姿势在北美洲 的意思是“一切顺 利”或“很好”, 在法国和比利时的 意思是“你一钱不 值”,而在意大利 南部的意思是“你

像头蠢驴”。

二、情绪的发生机制

• 1、生理机制 • 生理反映基础 • 生物钟的影响(28天为一周期):与月球周期性

变化有关 • 2、心理机制 • 客体与需要、预期的关系 • 认知评价的作用 • 个性特征

• 积极情绪时,左半球出现较多的电位活动; • 消极情绪时,右半球出现较多的电位活动

(二)情绪的外周神经机制

• 1、情绪与植物性神经系统 • 植物性神经系统与情绪的生理反应密切相关。

在某些情绪状态下,植物性神经系统的变化主 要表现为交感神经系统相对亢进,如激动紧张 时,瞳孔放大、心率增快、血压上升、血糖升 高、呼吸加速、胃肠道活动抑制;突然惊惧时, 呼吸暂时中断、外周血管收缩、脸色变白、出 冷汗、口干;焦虑、抑郁则可抑制胃肠道的蠕 动和消化液的分泌,引起食欲减退。

四、情绪的功能

– 适应功能 – 动机功能 – 组织功能 – 感染功能 – 迁移功能

第二节 情绪和情感的分类

• 1、情绪的分类 – 《礼记》七情说:喜、怒、哀、惧、爱、恶和欲。 – 生物进化观:基本情绪;复合情绪 – 伊扎德:复合情绪分三类,一是基本情绪的混合, 如兴趣—愉快;恐惧—害羞等;二是基本情绪和 内驱力的结合,如性驱力—兴趣—享乐、疼痛— 恐惧—怒等;三是基本情绪与认知的结合,如活 力—兴趣—愤怒、多疑—恐惧—内疚等。

普心复习材料

第六章感觉本章任务•解释人们身体和大脑如何对围绕在我们周围的刺激——视觉、声音等——产生感觉的。

•你将会了解体验不同维度的能力是如何掌握和发展的;•你将会发现那些早已习以为常的感觉所涉及的错综复杂的机制。

一、名词解释:感觉,感觉阈限,绝对阈限,差别阈限,韦伯常数,费希纳定律,感觉适应,暗适应,光适应,感觉后效,后像,正后像,负后像,临界闪光融合频率,闪光融合,感觉对比,同时对比,继时对比,视觉,听觉,嗅觉,味觉,肤觉,触觉,振动觉,温度觉,痛觉,动觉,平衡觉,内脏觉,机体觉。

1、感觉(sensation)是个体对刺激作用于某种感受器所产生的体内外的初级经验或觉知。

一切较高级、较复杂的心理现象,如知觉、思维、情绪、意志等,都是在感觉的基础上产生的。

感觉来源:外部感觉:接受机体外的刺激,觉知外界事物的个别属性,有视觉、听觉、嗅觉、味觉、皮肤感觉。

内部感觉:接受机体内的刺激,觉知身体的位置、运动和内脏器官的不同状态,有肌肉运动感觉、平衡感觉、内脏感觉等。

临床上分四类:特殊感觉,视、听、味、嗅、前庭感觉体表感觉,触压觉、温觉、冷觉、痛觉深部感觉,肌肉、肌腱、关节等感觉及深部痛觉和深部压觉内脏感觉刺激(stimulus)是进入感觉器官并使其产生反应的物理能量。

2、感觉阈限(sensory threshold)指在刺激情境下感觉经验产生与否的界限。

3、绝对阈限(absolute threshold)刚刚能察觉到的最小物理刺激量。

绝对阈限是一个统计学上的概念4、差别阈限(difference threshold)是刚刚能察觉出两个刺激的最小差异量。

差别阈限是指为探测出两个刺激间差异所需的刺激的最小变化量,因此也叫最小可觉差(just noticeable difference, JND)其大小取决于刺激的初始强度。

5、韦伯定律,即感觉的差别阈限随原来刺激量的变化而变化,而且表现为一定的规律性,用公式来表示,就是△Φ/Φ=C,其中Φ为原刺激量,△Φ为此时的差别阈限,C为常数,又称为韦伯率。

教心+普心大汇总

第一部分学生发展心理1. 知觉的特性1)知觉的选择性知觉的选择性是指人在知觉客观世界时,总是有选择地把少数事物当做知觉的对象,而把其他事物当做知觉的背景,以便更清楚地感知一定的事物与现象。

2)知觉的整体性知觉的整体性是指在知觉过程中,人们不是孤立地反映刺激物的部分或个别属性,而是反映事物的整体及关系。

3)知觉的理解性知觉的理解性是指在知觉过程中,我们总是根据已有的知识经验来解释当前知觉的对象,并用语言来描述它,使它具有一定的意义。

4)知觉的恒常性知觉的恒常性是指在知觉过程中,当知觉的客观条件在一定范围内改变时,我们的知觉映像在相当程度上保持着它的稳定性。

2.注意的品质与影响因素1)注意的广度注意的广度又称注意的范围,是指一个人在同一时间内能够清楚地把握注意对象的数量。

影响注意广度的因素主要有以下三个方面:①注意对象的特点;②活动的性质和任务;③个体的知识经验。

2)注意的稳定性注意的稳定性也称为注意的持久性,是指注意在同一对象或活动上所保持时间的长短。

这是注意的时间特征。

影响注意的稳定性的因素有如下三个方面:①注意对象的特点;②主体的精神状态;③主体的意志力水平。

3)注意的分配注意的分配是指在同一时间内把注意指向不同的对象和活动。

注意的分配的条件有以下两个:①同时进行的几种活动至少有一种应是高度熟练的。

②同时进行的几种活动必须有内在联系。

4)注意的转移注意的转移是指根据活动任务的要求,主动地把注意从一个对象转移到另一个对象。

影响注意转移的因素有以下四个方面:①对原活动的注意集中程度;②新注意对象的吸引力;③明确的信号提示;④个体的神经类型和自控能力。

3.注意转移和注意分散的区别:注意的分散,又称分心,是指在注意过程中,由于无关刺激的干扰或者单调刺激的持续作用引起的偏离注意对象的状态。

注意的转移是指根据活动任务的要求,主动地把注意从一个对象转移到另一个对象。

注意的转移不同于注意的分散。

前者是根据任务需要,有目的地、主动地转换注意对象,为的是提高活动效率,保证活动的顺利完成。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

十二、人格

气质和性格都是人格的组成部分,二者性质不同。

性格多受后天环境影响,具有较明显的社会化特性;而气质主要由高级神经活动的特点决定,受遗传影响较大。

(一)人格概述

Personality type is destiny.

1.人格的含义

人格:构成一个人思想、情感及行为的特有模式,这个独特模式包含了一个人区别于其他人

的稳定而同一的内心品质

它既包括人遵从社会文化习俗要求做出的外在言行,也指人不愿展露的真实自我。

2.人格的特征

独特性:一个人的人格是在遗传、成熟和环境、教育等先后天因素的互相作下形成的。

稳定性:偶然的心理特征不能称人格,但随着自身和环境的成熟和改变人格也能或多或少地

变化。

统合性:人格是由多种成分构成的一个有机整体,具有内在的一致性,受自我意识的调控。

统合性是心理健康的重要指标。

功能性:人格在一定程度上会影响到一个人的生活方式,甚至会决定某些人的命运。

(二)气质与性格

人格是一个复杂的结构系统,它包括许多成分,其中主要有气质、性格、认知风格、自我调

控等方面

1.气质概述

气质的含义:表现在心理活动的强度、速度、灵活性与指向性等方面的一种稳定的心理动力

特征

气质的类型:气质类型主要有以下几种特征

①感受性——人对内外适宜刺激的感觉能力。

它是神经过程强度特性的一种表现。

用感觉阈

限的大小来测量。

②耐受性——反应人对客观刺激在时间和强度上的耐受程度。

它是神经过程强度特性的表

现。

③反应的敏捷性——包括心理反应和心理过程进行的速度,以及不随意反应性。

反应的敏捷

性主要是神经过程灵活性的表现。

④可塑性——人根据外界情况的变化而改变自己适应性行为的可塑程度。

主要是神经过程灵

活性的表现。

⑤情绪兴奋性——以不同的速度对微弱刺激产生情绪反应的特性,反映神经过程的强度和灵

活性。

⑥向性——心理活动、外现行为表现与外活内的特征。

也就是力比多的流向。

(Jung的内

外向)

气质理论:

Ⅰ 气质体液说——源于古希腊医生希波克拉底,认为人体内四种液体:黏液、黄胆汁、黑胆汁、血液,四种体液配合比率不同,形成了四种不同类型的人。

后来盖伦提出了气质的四种类型:胆汁质、多血质、粘液质、抑郁质。

感受性耐受性反应敏捷性可塑性情绪兴奋

性向性

胆汁质 - + + + + +

多血质 - + + + + +

黏液质 - + - - - -

抑郁质 + - - - + -

看起来唯一的区别在于胆汁质的和多血质的情绪偏好不同……

现实生活中,单一气质的人不多,绝大多数是四种气质互相混合、渗透、兼而有之的。

Ⅱ 气质体型说——内胚层、中胚层、外胚层

Ⅲ 气质血型说——A、B、O、AB

Ⅳ 气质激素说——人的气质特点是由内分泌活动所决定

etc.

2.性格概述

性格的含义:人对现实的稳定的态度和习惯化了的行为方式中所表现出来的个性心理特征性格特征:四种性格特征相互联系,结合为独特的统一体,也就是一个人的性格

态度特征——人对客观现实的影响总是以一定的态度给与反应

意志特征——人在对自己行为的自觉调节方式和水平方面的性格特征情绪特征——人在情绪活动时强度、稳定性、持续性和主导心境等方面表现的性

格特征

理智特征——人在认知过程中的性格特征

(三)认知风格

认知风格:个人所偏爱使用的信息加工方式

1.场独立性—场依存性

在垂直视知觉的研究中发现了这种差异,表现在人对外部环境的不同依赖程度上。

场独立性:信息加工中对内在参考有较大依赖,心里分化水平高,与人交往神经大调场依存性:信息加工中对外在参照有较大依赖,心里分化水平低,与人交往体察入微

2.冲动型—沉思型

冲动与沉思差异的主要表现在对问题的思考速度上。

冲动:反应快,精确性差。

信息加工多采用整体性策略

沉思:反应慢,精确性高。

信息加工多采用细节性策略

3.同时性—继时性

左脑优势的个体表现出继时性的加工风格;右脑优势的个体表现出同时性的加工风格。

同时性:同时考虑多种假设,兼顾各种可能,发散式思维。

如:空间问题和数学

继时性:一步一步地分析问题,单线程思维。

如:言语和记忆

(四)人格理论

1.特质理论

特质理论认为特质是决定个体行为的基本特性,是人格的有效组成元素,也是评测人格常用

的基本单位。

Ⅰ 奥尔波特的特质理论

共同特质:特定社会文化形态下,群体或多数人共有的特质

个人特质:个人身上独具的特质,根据在生活中作用可分为以下三种

首要特质:一个人最典型和概括性的特质,影响人各方面行为

中心特质:构成个体独特性的几个重要特质

次要特质:不太重要,较少表露的特质

Ⅱ 卡特尔的人格特质理论

表面特质:直接与环境接触,随环境而变化,是从外部可观察到的行为

根源特质:隐藏在表面特质后,深藏于人格结构内层,制约表面特质的基础

根源特质必须通过表面特质的中介,通过因素分析法才能发现。

根源特质各自独立,相关极小,普遍存在于所有人身上。

但是各个根源特质在每个人身上强度不同,这就决定了人与人在性格上的差异。

卡特尔由此用因素分析法提出了16种相互独立的根源特质,从而编制了国际通用的16PF个性问卷。

Ⅲ 艾森克三因素模型

外倾性:表现为内外向的差异

神经质:表现为情绪稳定性的差异

精神质:人格特征的光明或阴暗

由外倾性和神经质的二维组合建立了人格环状模型,划分出与希波克拉底气质说类似的四大

象限

Ⅳ 五因素模型

用词汇方法对卡特尔的特质进行再分析,探究出最稳定的五个因素,也就是传说中的“人格

海洋”

Openness开放性:想象、审美、感情丰富、求异、创造、智能Conscientiousness责任心:胜任、公正、条例、尽职、成就、自律、谨慎、克制Extraversion外倾性:热情、社交、果断、活跃、冒险、乐观

Agreeableness宜人性:信任、直率、利他、依从、谦虚、移情

Neuroticism神经质:焦虑、敌对、压抑、自我意识、冲动、脆弱

2.类型理论

A-B型人格

人们在研究人格和工作压力的关系时,常使用这种人格类型。

A型人格:性情急躁、成就欲高、外向

B型人格:不温不火、容易满足、内敛,有耐性

内-外向人格

人的兴趣和关注指向(力比多流向)内还是外,决定一个人是内向还是外向人格

内向人格:自我剖析、深思熟虑、交往面窄

外向人格:情感外露、自主果断、善于交往

(五)人格形成的影响因素

生物环境因素

双生子研究是研究人格遗传因素的最好方法。

同卵双生子具有相同的基因,他们之间的任何差异都可以归结为环境因素的作用;异卵双胞胎基因不同,但在环境上有许多相似性,因此

也提供了环境控制的可能性。

人格是在遗传与环境的交互作用下逐渐形成的。

遗传因素对人格的作用程度随人格特质的不

同而异。

社会文化因素

社会文化塑造了社会成员的人格特征,使其成员的人格结构朝着相似的方向发展,这种相似

性反过来维系社会稳定和社会文化。

社会文化对人格的影响力因文化而异。

家庭环境因素

家庭是“人类性格的工厂”研究人格的家庭成因,重点在于探讨家庭的差异和不同教养方式

对人格发展和人格差异的影响。

教养方式主要有:权威性、放纵性、民主性

早期童年经验

人格发展确实受到童年经验的影响。

但是早期经验不能单独对人格起作用,它与其他因素共

同决定人格的形成和发展。

学校教育因素

学校是人格社会化的主要场所。

教师对学生人格发展具有导向作用,而同伴对人格发展具有

“弃恶扬善”的作用。

自然物力因素

自然环境对人格不起决定作用,但在不同物力环境中,人可以表现出不同的行为特点。

自我调控因素

对人格产生影响的上述诸多外因,是通过内因起作用的,人格的自我调控系统就是人格发展

的内部因素。